Abstract

During this research, the catalogues of more than 200 libraries and museums of Hungary and its neighboring countries were examined. The authors calculated the amount and the size of the metadata and of the full content records in the databases of their collection management systems, as well as the size and the type of the full content data and the size of the databases. By analyzing the results, the goal was to answer the following three questions: (1) Can any significant difference be established between the results according to country, nationality, or type of institution?; (2) How large is a metadata record or a full content record?; (3) Is it possible to establish a methodology for selecting a representative sample of institutions to facilitate further research? For planning the costs of data management, the size of the databases, the number of metadata records, and the variability of metadata and media records shall all be considered. A distinction should be made between the indispensable “primary” data to be preserved for a long time, and the “secondary” data units which are derived from the primary data. It is investigated in this article how to establish the size of primary data in the databases of collection management systems.

1 Introduction

Over the past decades, vast amounts of all kinds of documents have been digitized. In addition to analogue data repositories almost completely digitized, new documents produced recently are created digitally almost without exception. But digital data assets can be damaged very easily, and for reading digital content we need hardware and software devices which are rapidly becoming obsolete. To keep digital documents useable for later generations, experts should ensure that bitstreams remain unharmed and that data formats are updated. The long-term preservation of data has enormous costs, and it is always a significant part of digitizing projects. The causes of higher costs of Long-Term Preservation are the following:

bitstreams should not only be stored, but also preserved in such a way that they remain useable and searchable,

Long-Term Preservation needs special planning and requires extra skills of the staff,

the selection of the relevant and important data requires time and human effort,

a database can be easily damaged; therefore, it is necessary to make backups from the different versions of the databases.

When calculating this future cost, the key questions are: how many types of records should be preserved and how sizable are the records themselves? The Long-Term Preservation of digital information is the responsibility of memory institutions, in addition to keeping analogue documents safe to begin with. Memory institutions should reduce their storage costs by selecting analogue documents for preservation, the same way they need to choose the units of digital information important enough to be kept. How accurately the selection criteria should be determined depends on the size and the variability of the data units. There is a strong correlation between the preservation costs and the size of the bitstream (storage device, processor capacity, human efforts) and between the costs and the variability of data (several types of applications for using and searching the data).

When it comes to the applications used by memory institutions, the so-called Collection Management Systems (CMS), it is worth examining how they store the information, both the metadata and the media files; what kind of data they need to handle; and how much space their databases need.

The research this paper focuses specifically on the quantitative aspects of data preservation. Librarians and museum and IT experts need to have clear and exact knowledge of the amount, the size, and the variability of the records (metadata and full content) they work with; of how much space these records need at any given time; and of how much space they will need in the future. To ascertain the average size of the records, the concept and the structure of the records of the collection management systems need to be clarified. To achieve this, there seemed to be no better method than to examine as many databases as possible.

2 Review of the Recent Issues of Digitized Information from the Perspective of Long-Term Preservation

Memory institutions (the members of the LAM sector: Libraries, Archives, and Museums) have built large collections, and have gained useful experience in fulfilling their duties, sharing their metadata, providing real-time discovery services of cultural heritage, and preserving the documents of their collections. At the end of their lifecycle, all datafiles and data streams end up at memory institutions, where they are guarded, catalogued, and prepared for being searched and for further use. As it is stated in a paper, considering qualitative inquiries: “Facilitating access to digital content involves more than scanning documents and populating archives. Libraries must provide metadata and create search tools that allow users to locate the documents they need, provide rich contextual information, and build sustainable funding models that will allow these collections to remain permanently available” (Kyrillidou, Cook, and Lippincott 2016, 49). Thus, although some of the research data in the catalogues of memory institutions have become obsolete, are not searched or used on a daily basis, and cannot produce reasonable profit for business institutions, they can still be of interest to the public, and once they were produced at high costs. This is the reason why they are usually given to memory institutions to be archived there. According to Rayward:

The complement to this question is the extent to which older, out-of-date, less-used parts of these electronic files will be effectively and permanently ‘archived’. These issues have hardly become a problem yet, because most of the files now being dealt with cover a relatively short period of time. But in two or five or 10 or 50 years, one may assume that the commercial organizations responsible at the moment for these services, given the rapidly increasing size of most of the files, and assuming that the pace of technological change will continue unabated, are unlikely to want to preserve the files permanently in an always currently accessible database. Presumably, the responsibility for the preservation of, and the provision of access to, these files after their current commercial exploitability has passed will at some point be given over to what have hitherto been called libraries or data archives (Rayward 1998, 216).

The most important goal of this experimental research is to help the efforts of memory institutions to preserve the most important and indispensable information of the databases for a long time. In this case, “a long time” means the length of time in which essential, radical, and mostly unforeseen technological and sociocultural changes take place. The format and the usage of the produced digital content themselves, and also the applications handling these contents, are changed to such an extent that the formerly produced data units cannot be used by the new applications smoothly. Therefore, “long-term,” from our point of view, means ca. 50 years (Neuroth et al. 2010).

To select data worth preserving, relevant knowledge about the records is necessary. To preserve metadata, the integrity, the validity, and the originality of the records of the databases shall be established. To choose suitable technical tools with which data loss can be avoided and the reuse of data can be secured in the future, a preservation plan shall be made covering the entire lifecycle of the metadata. This preservation plan should consist of not only the criteria of the integrity and originality of the metadata records, but also the preferred data formats and preservation tools, and especially the costs, which can be surprisingly high. As Fröhlich writes: “The real challenge of building digital archives begins not with, but after storing the digital objects; it is all about permanent system maintenance”[1] (Fröhlich 2013, 133).

The best solution suggested by the Nestor Handbuch is that Long-Term Preservation is the combination of the following four methods:

constant updating of the metadata records and full contents,

replication of bitstreams on different datastores,

repackaging of datafiles,

transformation of metadata (changing not only the location but the structure of the records as well) according to current standards, the most successful methods, and best practices (Neuroth et al. 2010).

All four solutions are similar regarding the aspect that costs are strongly dependent on the size of the data to be preserved. Distinctions need to be made between preventive and curative preservation, and between preserving a digital object and storing the digitized information. As Tripathi writes: “Preventive preservation is limited by environmental control and protection from undesired happenings. Curative preservation, on the other hand, aims to restore the object which is already damaged or endangered.” Therefore, preventive preservation means taking steps to avoid the data becoming damaged or obsolete. Curative preservation means the steps of repairing or updating the metadata records or content files after a certain problem has occurred. To become familiar with the concept of data integrity and preserving information, it should be noted that it is not the data record itself that is worth preserving, but the information it contains (Tripathi 2018, 8). Preserving data, especially the original bitstream, is the main function of data management. Data managers should keep full content files, metadata, and technical and administrative information on how the data unit was produced and is archived together. When taking care of the four kinds of information (full content, metadata, technical information, administrative information), the focus of attention should not be on keeping the digital objects unharmed, but rather on the information they contain. Most aspects of how to choose the best method and the most effective workflow for data preservation is to be examined in the planning phase of a digitization project. As Oßwald states in his paper: “The effort to physically secure both the full content data and the technical and administrative metadata documenting their creation and the archiving process itself (bitstream preservation) seems to be a fundamental element of data preservation. Therefore, it is only the first, albeit essential, part of the complex set of tasks which ensure the long-lasting maintenance of a digital archive”[2] (Oßwald 2014, 274).

The workflow of Long-Term Preservation (LZA LangZeitArchivierung) is divided into three steps in the paper of Birkner and his co-authors, “Guideline zur Langzeitarchivierung”:

guaranteeing physical integrity,

securing reusability,

making the data searchable (Birkner et al. 2016).

Preserving the bitstream, the environment, and the information about the creation of the data record is expensive. The high costs of LTP should be planned precisely, and they should be calculated into the budget of all digitization projects. To calculate the costs, it is important to know the current and the future size of the database. For cost planning, relevant information is needed on the needs for data preservation, considering hardware, software, and human resources as well (Mayer 2016). In order to focus on the technical aspects of preserving digitized information, a deep knowledge about the digital data itself is necessary. The most important attributes of digital data are the location, the size, the variability, and the validity of the datafiles to be registered. The difference between handling metadata, database indices, and full content should be established, and the distinction between the catalogue units of libraries, museums, and archives must be clear as well. Hybrid institutions which can act as any member of the LAM sector need to be taken into consideration. The concept of the hybrid library, for example, is described by Siegmüller as follows: “A hybrid library integrates publications (mostly online documents) to its collection regardless of the carrier medium”[3] (Siegmüller 2007, 7). Regarding the technical aspects of data storage in databases, it is essential to pay attention to SQL-based and not SQL-based data management, comparing the efficiency of the utilization of hardware resources in both cases. Specifically, the effectiveness of managing big databases should be examined. As Cattell points out: “In recent years a number of new systems have been designed to provide good horizontal scalability for simple read/write database operations distributed over many servers. In contrast, traditional database products have comparatively little or no ability to scale horizontally on these applications” (Cattell 2010, 7). Comparing the solutions of SQL-based and not SQL-based data management and having the SQL data in datafiles or in raw devices can both be informative. To preserve as much information for the future as possible, it is necessary to attempt to reduce the costs of data storage. In order to save disc space, it is worth examining the alternative ways of storing datafiles, according to the basic technical principles of cloud-based data management and the recent results of mass digitization. According to Peng’s statement: “In supporting efficient and reliable access to massive restricted texts, the primary storage system plays a key role. There are numerous factors to consider when choosing an optimal storage solution for large digitized textual corpora. Conventionally, it is the performance of the data storage system that is the major decisive factor for overall throughput” (Peng 2018, p. 7). The issues of data structure, data content, and mapping administrative and technical metadata should be examined from the perspective of other experts outside memory institutions and collections as well (Kopácsi, Rastislav, and Ganguly 2017).

There is another point of view to be considered: the examination of a database as a constantly changing organism. Transaction management in databases, the use of timestamps, and the storage of data history are also part of the long-term preservation of information. Without transaction management, information may be lost. The main tools of transaction management are:

Data Versioning – in order to ensure that earlier states of data sets can be retrieved.

Timestamping – operations on data, including any additions or deletions, shall be marked with a timestamp.

Query Store Facilities – storing queries and the associated metadata in order to re-execute them in the future (Rauber et al. 2016).

Even though the main focus is the preparation of databases for preservation, the needs of the end user of the data and the user interfaces should not be neglected. The changes in consumer behavior and the newest ways of searching and using information cannot be examined separately from data management. As Rasmussen wrote: “[There is a] common trend in library studies, archival science, and museology in articulating a transformation from collection-driven institutions toward something new, such as user-driven, customer-driven or co-creation … ” (Rasmussen 2019, 1260). Librarian and museum experts are also data users, much like end users (readers), to the extent that they cannot see the data record itself, but only its manifestation on the user interface. Therefore, data handling, the evolution of ILS (Integrated Library Systems) and ICMS (Integrated Content Management System), the role of the new modules, and the new features also need to be taken into consideration. It is time to build semantic networks from static catalogues. For this work, data analysis should be in the background. When it comes to data analysis in databases, the step of data preparation should precede data inspection. The result set should be prepared for arithmetical analysis; cleaning the result set, erasing the irrelevant data elements, and making the data elements suitable to execute calculations on them. The data preparation can be followed by the data inspection.

During the preparation of records, the database should be “manipulated” to enable the execution of the planned examinations, without the modifications having an effect on the results of the research (Kouzari and Stamelos 2018). Data preservation does not only entail managing metadata records but the maintenance of the full content as well. Therefore, with the questions of mass digitization, the LSDI (Large Scale Digitizing Initiatives) projects should be examined from a librarian’s point of view. The best summary of the LSDI projects can be found in Elisabeth A. Jones’s book, “Constructing the Universal Library” (Jones 2014).

3 The Question of the New Data Models

In the beginning, digitization in the LAM sector was based on the existing standards of cataloguing. The ISBD (International Standard for Book Description) in the libraries and the regulations of museums and archives were followed by data formats readable by computers, the MARC (Machine Readable Cataloguing) format in particular. The FRBR (Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records) data model’s concept is that through modelling the conceptualization of reality behind library practice, from the user’s point of view, it regards bibliographic data as a batch of information relevant to the publication. The IFLA’s (International Federation of Library Associations) aim in developing the LRM (Library Reference Model) was to harmonize the data models, and to resolve the inconsistencies between them (Riva, Le Bœuf, and Žumer 2017). The three new models, (1) the FRBR (IFLA 2009), (2) the FRAD (Functional Requirements for Authority Data) (Patton 2009), and (3) the FRSAD (Functional Requirements for Subject Authority Data), were developed independently over many years by different working groups. IFLA LRM is a model created according to the needs of the library community, for the management of library data (IFLA Study Group on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records, 1998). While the library community was developing the FRBR model, the museum community was developing its own conceptual model for museum data: the CIDOC (Comité International pour la Documentation – International Committee for Documentation) CRM (Conceptual Reference Model) (Bekiari et al. 2017). The FRBRoo, as a high-level conceptual model, is the result of a dialogue between the conceptual modelling communities of IFLA and the International Council of Museums (ICOM) (Lei Zeng et al. 2010). The data format of the ICMS Qulto-L and Qulto-M is based on library and museum regulations. The tagging and the segmentation make it compatible with MARC and LIDO (Lightweight Information Describing Objects), thus, it can import and export information from several MARC formats (e.g., MARC21 or UNIMARC) and LIDO without data loss. It is also based on the FRBRoo conceptual model.

The authors wished to get a comprehensive and well-founded view on how much space is needed by a database of an RDBMS-based (Relational Database Management System), MARC- or LIDO-compatible ICMS in the runtime environment as well as in a compressed format. In the second part of the research, the goal was to examine how the authenticity and the integrity of the endangered data are secured during everyday use; how the data are transformed during long-time use; and how to differentiate between the size of the whole database and the size of the blocks of primary (indispensable) data units. The paper aims to answer the question whether there are tendencies to be recognized related to the growth of the size of media and perhaps also that of metadata records, and whether the operational systems are overburdened due to the increasing amount of full content, regarding preservation and later use. After gathering systemized and anonymized data from the databases of memory institutions, new information yet unpublished can be extracted. These results can have an impact not only on European projects, but on the development of other continents as well.

4 The Concept of Primary and Secondary Data

For Long-Term Preservation it is also essential to distinguish primary data elements from derived, secondary data elements. It should be examined how they can be stored separately, knowing that the derived data elements are also valuable, since financial, technical, and human resources are needed to produce them. The distinction between primary and secondary data should be clear. The role of indices and other derived data units should also be clarified. Primary data are either typed by users into the ICMS or imported from other databases; they should be preserved, since they are indispensable. Secondary data are derived from primary data in order to make the application more user-friendly, help browse and search, or let the system work faster. Because of the extremely high costs of Long-Term Preservation, only primary data are to be prepared for preservation. According to Long-Term Preservation, the information on how the secondary data were prepared should be stored as well. The method of creating secondary data is part of the application. These procedures would better be stored in a software museum (Riley-Reid 2015).

By examining the size of the different types of databases, it is possible to answer the question whether it is important to separate primary and secondary data elements to keep only the primary ones for long-term preservation. This examination may also shed light on whether the size of the records organized in relational databases are as small as common text files, and whether it is true that the size of digitized images is generally so large that the size of a handful of images exceeds that of a whole library catalogue.

The authors are certain that it is worth the effort to separate validated, well-tagged, and indispensable metadata. These should always be in an updated format, and they should be handled with special care, to preserve them for later generations.

5 Methodology

Having the possibility, the permission, and the technical skill, the authors have examined the catalogues of the customers of Qulto Companies, a Hungarian firm developing integrated collection management systems for libraries and museums in East-Central Europe. The Qulto ICMS is up to current international standards. The data records of library catalogues are MARC-compatible, and the units of the digital inventories of museums are LIDO-compatible. The bibliographic, entity, media, and authority records of the catalogues are linked in a semantic network, based on a relational database management system, and all the repeated data are in a list of values. This advanced data structure is widely used for library and museum management systems in Europe, therefore, experiences from East-Central Europe related to the size and reusability of databases could be considered valid in general.

The technical information in the databases of the customers of Qulto Companies (https://qulto.eu) are not public. Customers can only see the data published on the Web OPACs (Online Public Access Catalogue), and librarians can get information from their own databases to the extent the developers make them visible on the user interface. Technical data are searchable only by system librarians or by system managers, but they can only see their own databases, and most of the transaction records and the data structure of the application are hidden from them as well. Even if they can use the tools of the Operating Systems and the Database Management Systems, they do not have enough information about the data structure and the business logic of their ICMS to mine relevant information from their database.

For the employees of Qulto Company who are members of the Client Success Management Team of the firm, entering the clients’ databases is part of their everyday work. Together with their colleagues, their duty is to repair damaged databases, modify data according to the customers’ instructions, and prepare reports for them about their own system. According to the customer contracts, the employees of the company have permission to get anonymized statistical information from the customers’ databases. This statistical information can be used for several purposes. It is just as important for librarians as well as for software developers to have sufficient and relevant information about the development of the databases of memory institutions.

During researching the size of the databases, approximately 360 library and museum catalogues, was examined. Among these, 250 seemed to be relevant enough to be included in this research. The size of the metadata records and the visual and full text contents were examined separately. An SQL script was written to calculate the space allocated for the databases, to establish the size of the primary (not derived) data tables, and to examine the age and the validity of the metadata records and datafiles. This script was run on all the examined databases, and the results were collected into data tables, in which each row contained the data for one anonymized institution.

The examined data of the databases:

size of the dataspace used by the database management system,

size of the catalogue data themselves,

size of the compressed catalogue data,

number of catalogue records (descriptive metadata),

number of entity records (administrative metadata),

number of media records,

size of media files,

type of media files,

extension of media files,

type of collection management system according to the use of loan module,

institution type,

country of institution.

The collected information was migrated to a database and was analyzed with the tools of the PostgreSql language, using mostly the “Avg,” the “Sum,” and the “Group by” functions. There was no hypothesis constructed before the research. Since collecting information about all of the customers’ databases was necessary, no pre-selection was done among the databases. Using the possibilities of the database management tools, the largest possible amount of data was collected.

6 Describing the Research

6.1 The Criteria of the Selection of Databases

To keep the research transparent and to avoid being confused by the various data storing methods and technical solutions of different applications, the product called Qulto – Huntéka ICMS (Integrated Collection Management System) was chosen, which is used by libraries (Qulto Huntéka-L), museums (Qulto Huntéka-M), and archival collections (Qulto Huntéka-A) as well. Each Qulto – Huntéka ICMS version is built on the same data structure and business logic, and uses the same data management techniques.

Among the examined databases of Qulto – Huntéka ICMS, there were a few which did not contain enough records, while on a few others the script could not be run, thus 247 catalogues were selected in the end. Table 1 shows the number of examined databases by institution type. County libraries have their own column,[4] separate from the one including public libraries of bigger and smaller cities. In Hungary, and also in other parts of the Carpathian Basin (where all the examined institutions are), the population density is almost the same everywhere, therefore, rural towns are relatively small. In Hungary, 17% of the population lives in the capital, Budapest, and its municipal library is the largest public library of Hungary by far, but even though it is a customer of Qulto Companies, it does not use the Qulto – Huntéka system, and its data could not have been published anonymously, therefore, it is not included in this research. Regarding public libraries, it should be noted that most municipalities (having more than circa 4000 inhabitants) have their own library maintained by the local community, and only the libraries of the smallest villages are maintained by the county libraries. Museums are maintained only by a few bigger cities in Hungary. The public libraries and the museums of rural towns are functioning both as municipal and as county institutions. The church (Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish as well) has traditionally large libraries and even museums, and most of them survived the “people’s republic” era between 1945 and 1990. Nowadays, church libraries are mostly museum-like collections. The libraries of the educational institutions of churches were included in the category of school libraries and high school libraries.

Examined databases by institution type.

| Country/type | Public/city library | Public/county library | Special library | High school library | School library | Church library | Museum | Archival collection | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hungary | 53 | 4 | 51 | 20 | 49 | 10 | 38 | 2 | 227 |

| Romania | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 14 | ||

| Serbia | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| Slovakia | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Sum | 59 | 8 | 55 | 22 | 49 | 11 | 41 | 2 | 247 |

In the neighboring countries of Hungary, the conditions are similar. There are only two exceptions. In Serbia, small settlements are gathered into bigger municipalities, having their local institutions. In Romania, only the bigger cities have their own libraries, therefore, the county libraries are a bit larger than the ones in Hungary. From the 20 institutions located in Romania, Serbia, and Slovakia, there are 14 (four in Serbia, two in Slovakia, and eight in Romania) which are Hungarian libraries, so most of the readers and the librarians are of Hungarian ethnicity. No difference was found between the institutions according to the country where they are located or the ethnicity of the users of the system.

7 Findings

7.1 Results of the Catalogue Examination

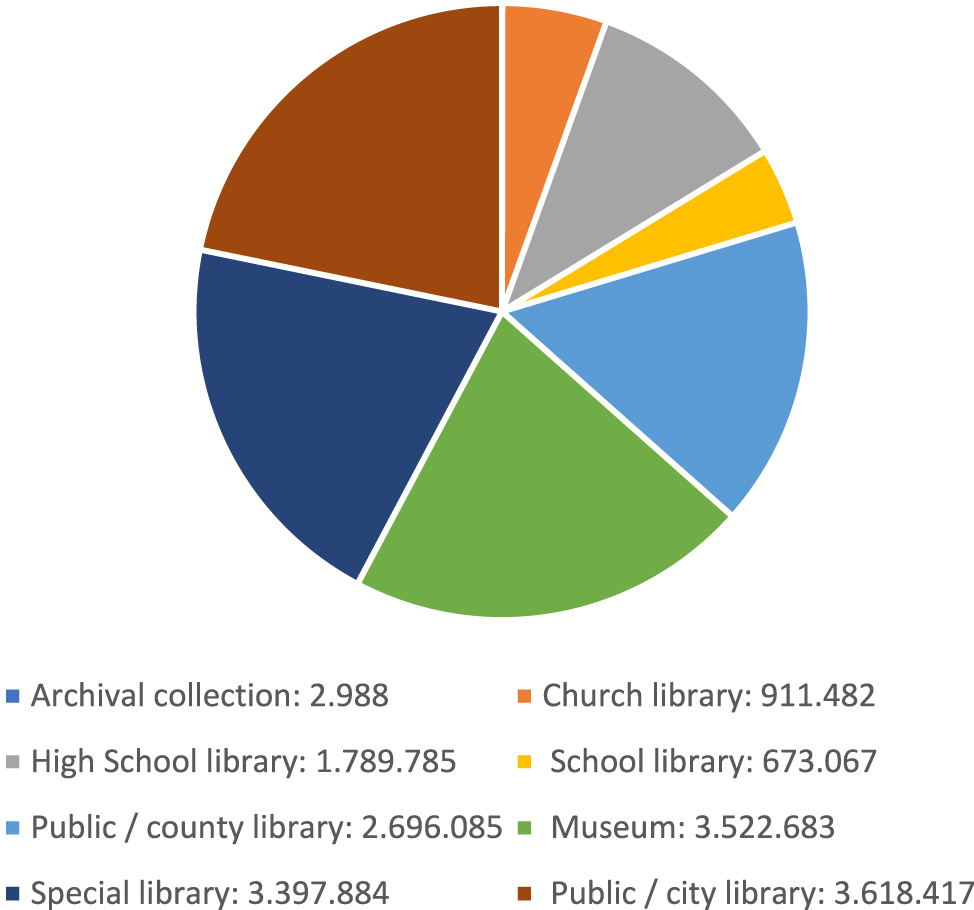

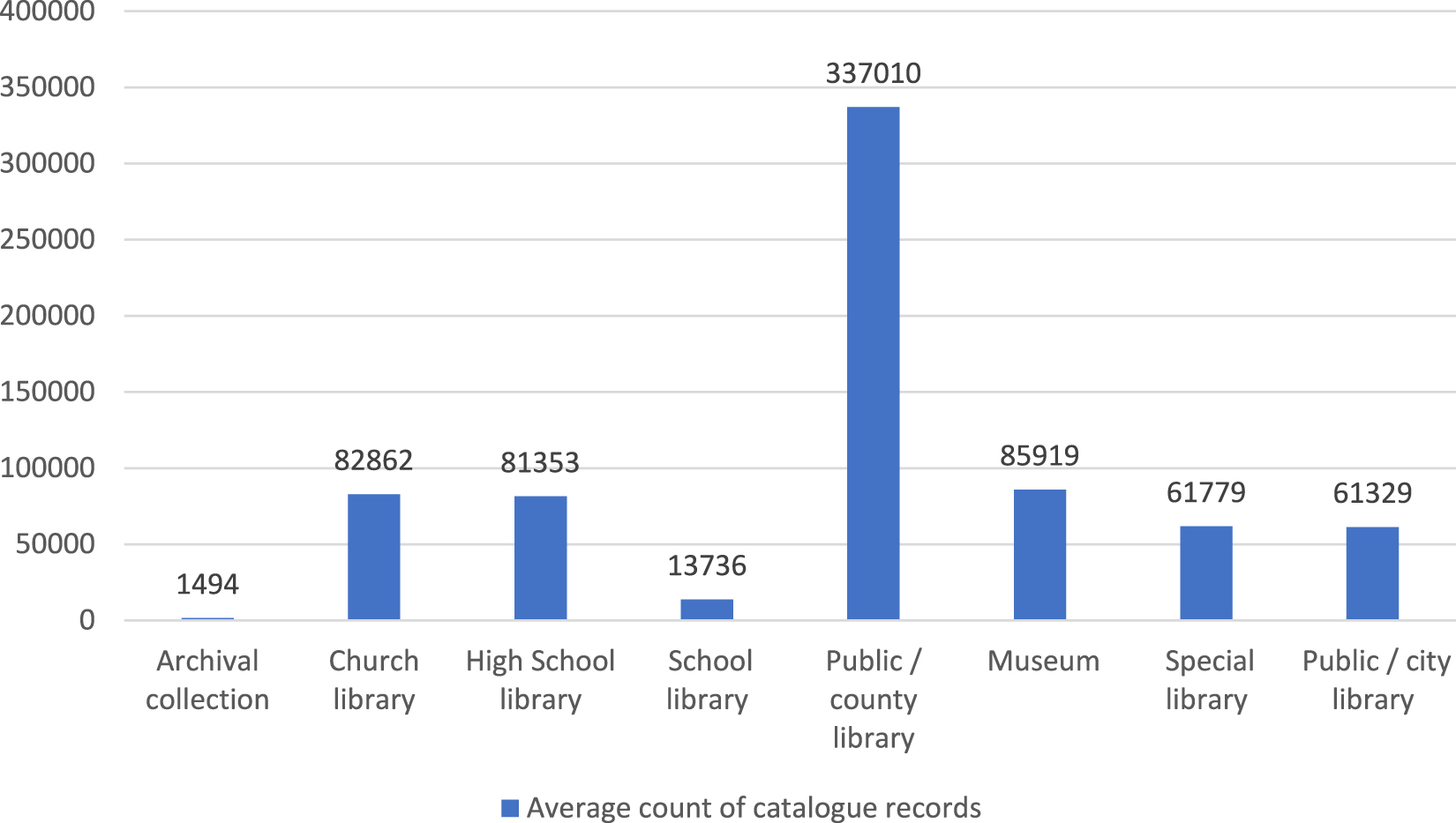

The total number of bibliographic (descriptive metadata) records of the examined catalogues is 16,612,391, more than 16 million. To demonstrate the amount of data collected and analyzed from the examined databases of the LAM sector, Figure 1 shows the total number of catalogue records by institution type. To provide information about the network of memory institutions in East-Central Europe, Figure 2 shows the average number of bibliographic records by institution type.

Total number of catalogue records by institution type.

Average number of catalogue records by institution type.

As the numbers show, the average catalogue record count of public county libraries (337,010) is a lot greater than the average record count of other institution types (between 60,000 and 80,000), and school libraries and archives, which have a noticeably low average record count (less than 20,000). As the data shows, the record counts (both total and average) of high school libraries are relatively small compared to county libraries. In Hungary and in Romania, there are many local high schools, and even the biggest universities of these countries are relatively small. Specifically, the high schools which are the users of “Qulto-Huntéka L” are the smaller ones among the Hungarian and Romanian high schools.

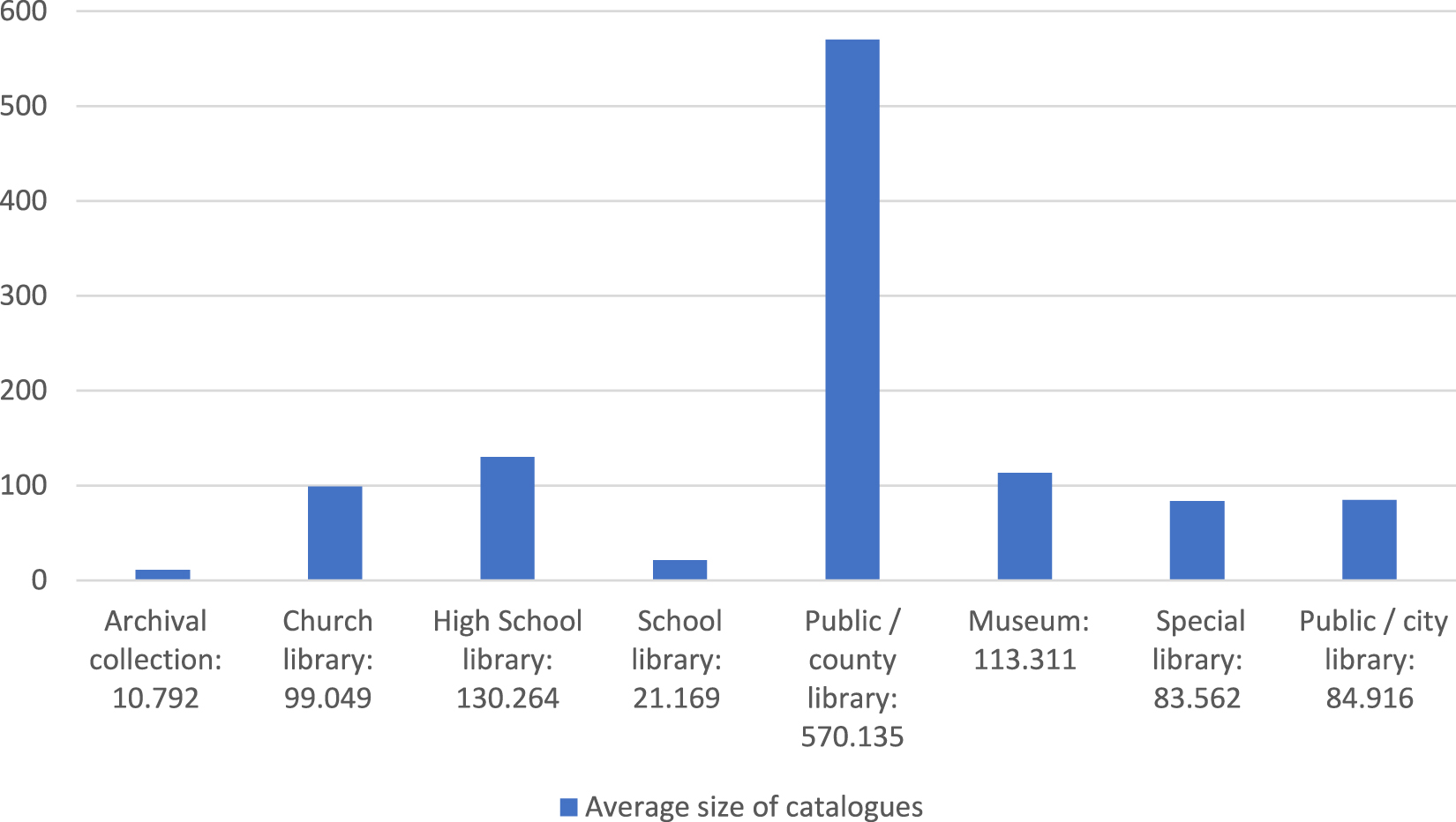

Another important element is the size of the database tables of catalogue data. This was calculated by preparing an SQL dump file from the tables of the catalogue metadata information (bibliographic data – descriptive metadata) of each examined database. These SQL database dump files only contain text data, from which the catalogue tables of the database could be recreated (usually, similar SQL dump files could be used to recover a database after a breakdown). Figure 3 shows the average size of tables of catalogue data in megabytes by institution type. Likewise, regarding the average record counts of institution types, the average size of the catalogues of county libraries is a lot greater than the catalogues of other institutions, and the size of the catalogues of school libraries and archival collections are the smallest.

Average size of tables of catalogue data in megabytes by institution type.

The average size of one catalogue record is almost the same in each database, except for archival collections. Table 2 shows the average size of a catalogue record by institution. The average size of a catalogue record was calculated by combining the size of the uncompressed dump files of the catalogue tables in the examined databases by institution type. This number was then divided by the total number of the catalogue records, also by institution type. The dump files contain only the data of the catalogue tables.

Average size of one catalogue record in bytes.

| AVG size of one catalogue record | Type |

|---|---|

| 1.086 | Church library |

| 1.125 | Museum |

| 1.278 | Special library |

| 1.384 | Public/city library |

| 1.480 | Public/county library |

| 1.541 | School library |

| 1.601 | High school library |

| 7.223 | Archival collection |

| 1.323 | Total |

The size of a database depends not only on the number and size of bibliographic records, but on the number and size of item records as well, therefore, it is important to count the average number of item records (administrative metadata in museums and archival collections) in comparison to bibliographic records (descriptive metadata in museums and archival collections). The number of bibliographic records and the number of item records were both combined. The number of bibliographic records was divided by the number of item records. The number of bibliographic records having any attached item record (e.g., records of analytics) was also considered among the number of bibliographic records. The aim of this research was to examine the size of the databases and not the average item count attached to one bibliographic record. That is the reason why there are institution types (special library, archival collection, museum, public/city library) with slightly less item records than bibliographic records (otherwise, any item record can exist without a bibliographic record in a system, so if the bibliographic records without any item record were not added to the total number of bibliographic records, the average number of entity records could not be smaller than one). The average item count/bibliographic record count is 1.2 in church libraries, 1.3 in high school libraries, 1.4 in public/county libraries, and it is the highest, 1.5, in school libraries. The proportion of item records compared to bibliographic records is always slightly larger in the same category if the library uses the loan module of Qulto – Huntéka. In special libraries and city libraries the high number of analytic records makes the relative proportion of item records relatively small compared to the number of bibliographic records. The museums and archives of Hungary and its neighboring countries cannot have more than one item record, hence the proportion of the item records should be a little bit under one.

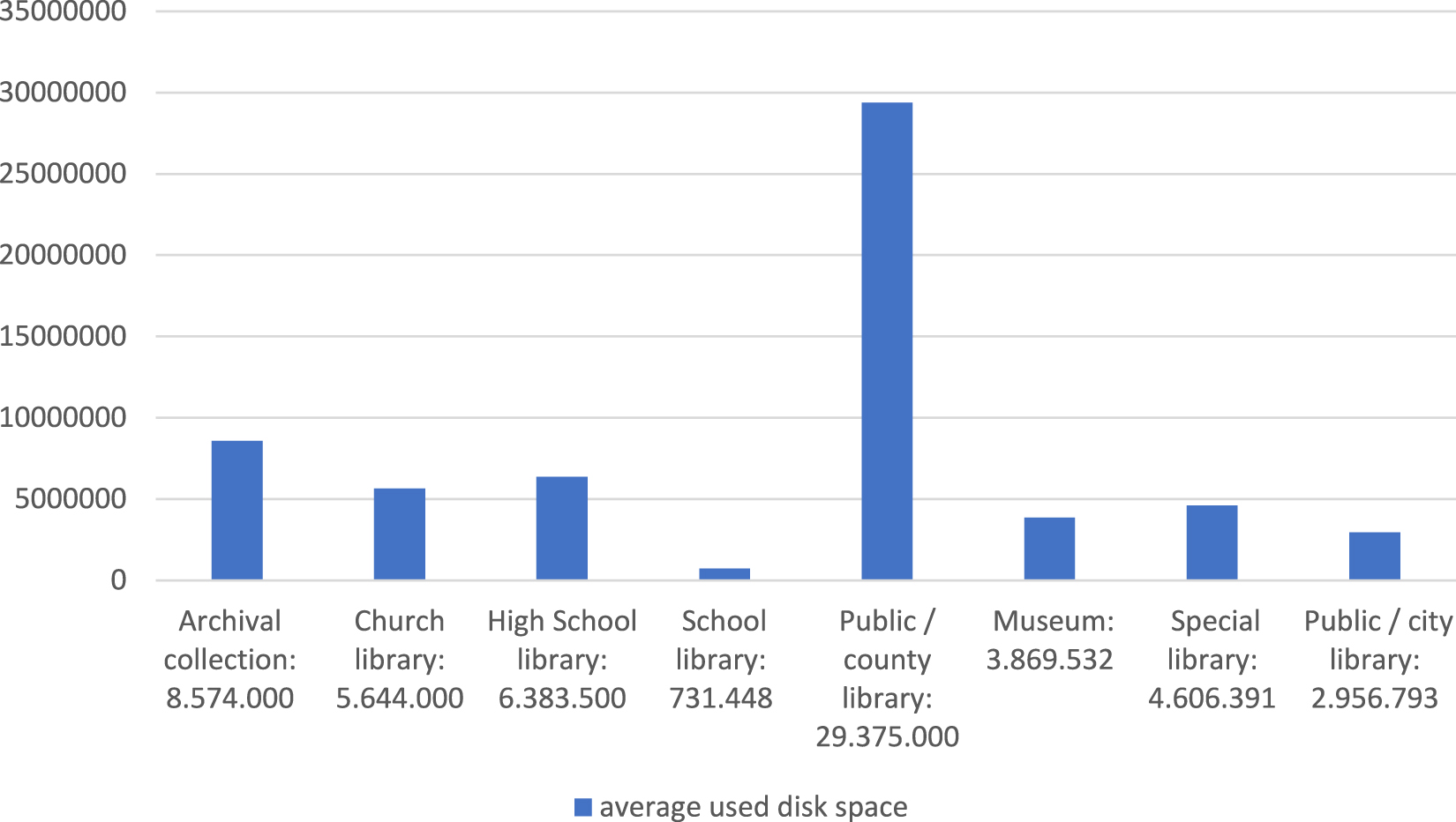

Besides the size of the catalogue itself, which gives us information about the necessary disk space for the saved databases, disk storage currently used by a database management system indicates how much disk storage space is necessary for a running database. Therefore, it is worth looking at the information about the average disk space used by the databases by institution type. The numbers do not indicate the disk space allocated for the systems but the disk space which was actually used by the database of the ICMS at the time of examination. The Qulto – Huntéka application is constructed so that it does not contain the media files themselves, only their metadata. Figure 3 shows the average size of the catalogues. The data are given in megabytes, categorized by institution type. Comparing Figures 3 and 4, it is evident that even though the size of the catalogue is only one part of the whole database, there is a strong correlation between the size of the catalogue tables and the size of the whole database of the ICMS.

Average size of databases on storage devices in megabytes by institution type.

It is worth examining the relative proportions of the size of the whole database and the size of the catalogue itself. When examining the size of a database, it should be considered that the whole database of an ICMS consists of four parts:

The elements of an “empty” database (structure of tables, definition of indices, triggers and stored procedures, basic dictionary elements, translations etc.). The size of the empty database of Qulto – Huntéka ICMS is so small (less than 30 megabytes) that there is no reason to take it into consideration.

The catalogue data themselves.

The administrative information used by the library management modules (loan, acquisition, serial, inventory management, etc.).

The secondary (derived) data, like indices, normalized values, and derived data tables, which all help the application’s browse and search functions and management modules to work faster.

The second unit, the catalogue data, needs to be separated, since it is a type of primary data worth Long-Term Preservation. Dividing the database in this manner, the two numbers should show the relative proportions of the whole dataspace used by the database of the ICMS and the size of the compressed catalogue tables.

After calculating the size of the dataspace of the databases according to institution type and the usage of the loan module, the compressed sizes of the data tables were combined by institution type, and then divided. The higher the result of the division, the larger the difference between the compressed catalogue and the size of the entire database. As it was demonstrated in Figure 4, the size of the catalogues was calculated by creating SQL dump files of the database tables of the catalogues. These dump files were compressed. The compression was always performed with the same Gzip command on Linux OS. The authors examined how effective the compression is, and how much smaller the compressed file is compared to the original.[5]

Looking at the results of the calculations, it can be established that the size of compressed catalogue tables is 25–90 times smaller than the size of the disk space used. The smallest difference was seen in public city libraries, while the largest in special libraries. The loan module is the most heavily used part of integrated library management systems. When examining the used dataspace on the servers, it should be noted whether an ILMS uses the loan module or not. The difference between the used dataspaces of the RDBMS is significant according to the use of the loan module, even when comparing the databases of institutions of the same type. The use of loan functions needs space. The average use of disk space for the examined systems is 63,901 bytes per catalogue record. Looking at the systems using a loan module, this number is 67,361 bytes per catalogue record, and in the systems which do not use loan module, this number is 60,617 bytes per catalogue record.

7.2 Examination of the Attached Media Files

During the research, 24 full content media databases of various institutions were examined. Among these, 22 are located in Hungary and two in Romania. According to institution type, there are 15 museums (with 722,800 media files in total), seven libraries (with 102,362 media files in total), and two archival collections (with 202,349 media files in total). The average size of the media files in libraries and archives is four megabytes, while in museums the average size is 7.5 megabytes.

When examining the types of attached media files, the information (the extension and the type of the attached files) recorded automatically in the database of Qulto Huntéka can be used. The string of the data field in which the extension of the attached file was recorded was normalized. All strings were converted to all lower case. No other modifications were made on the data of the extension field. The type of the attached media was selected in Qulto – Huntéka by the cataloguing person from a dictionary. There are some new values that were added by the employees of the institutions. To get a more accurate overview, the media type information was standardized according to the file extensions. Table 3 shows the number and the average file size of the media records in the examined 24 institutions. The numbers of files are categorized by file and media type. Unsurprisingly, the average size of video files is the largest (724,617 megabytes), followed by audio files (140,149 megabytes). It is worth noting, however, that the average size of image end text files is almost the same (5116 and 4497).

Number of media files by type and extension.

| Media type | Extension | Number of files | Average size in megabytes |

|---|---|---|---|

| application | octet-stream | 3 | 0.138 |

| application | postscript | 11 | 2.6148 |

| application | ppt | 3 | 7.202 |

| application | pptx | 1 | 43.419 |

| application | vnd.ms-excel | 1 | 0.025 |

| application | vnd.ms-powerpoint | 2 | 183.199 |

| application | vnd.oasis.opendocument.text | 1 | 0.031 |

| application | vnd.openxmlformats- | 45 | 0.886 |

| application | webp | 30 | 0.035 |

| application | x-photoshop | 90 | 27.797 |

| application | x-troff-msvideo | 2 | 46.572 |

| Sum | 17.753 | ||

| audio | 4mp3 | 1 | 33.644 |

| audio | mp3 | 730 | 29.323 |

| audio | mpeg3 | 2175 | 41.758 |

| audio | x-wav | 2079 | 282.049 |

| Sum | 140.149 | ||

| database | mdb | 8 | 10.251 |

| Sum | 10.251 | ||

| image | bmp | 21 | 8.335 |

| image | gif | 21 | 0.038 |

| image | jpeg | 671,773 | 2.224 |

| image | jpg | 120,745 | 4.217 |

| image | pjpeg | 1 | 0.168 |

| image | png | 676 | 3.082 |

| image | psd | 3 | 75.155 |

| image | raw | 304 | 5.634 |

| image | tif | 56,389 | 20.453 |

| image | tiff | 65,304 | 23.298 |

| image | x-ms-bmp | 188 | 4.658 |

| Sum | 5.116 | ||

| 105,645 | 5.429 | ||

| Sum | 5.429 | ||

| text | css | 2 | 0.003 |

| text | doc | 10 | 48.422 |

| text | htm | 1 | 42 |

| text | html | 2 | 2.381 |

| text | msword | 225 | 2701 |

| text | richtext | 4 | 107 |

| Sum | 4.497 | ||

| video | asf | 8 | 45,413 |

| video | m4v | 45 | 874,109 |

| video | mkv | 2 | 5782 |

| video | mov | 3 | 94,381 |

| video | mp4 | 444 | 682,419 |

| video | mpeg | 239 | 1,484,916 |

| video | ogg | 3 | 58,032 |

| video | quicktime | 179 | 19,535 |

| video | x-flv | 26 | 57,253 |

| video | x-ms-wmv | 23 | 55,916 |

| Sum | 724.617 | ||

| zip | zip | 43 | 61,682 |

| Sum | 61,682 | ||

| Total number: | 1,027,511 |

The research plans included the examination of the changes of the average size of files throughout the years, but there was no relevant information in the databases. Most of the institutions have been using Qulto – Huntéka Full Content Module for a couple of years. Informative results can only be expected from future examinations.

8 Discussion

By examining the data tables and figures, information can be gathered about the degree to which memory institutions can be loaded, which are meant for the storage of digitized catalogues. The analysis also demonstrated how much effort is required of the institutions to preserve the data history of the automated catalogue systems used every day. For systems in everyday use, the preservation of record history is a necessity. In case of a complete breakdown or irreparable hardware error, the newest database save file is needed for the recovery of the database. If it is not the entire database that is damaged, and there is only a group of records to be recovered, older database dumps can often be utilized, since the mistakes of the database are often not realized on the day. Thus, the more backups there are, the more intact the catalogue data can remain. The size of the saved files, and whether the dump of the entire database is required or a dump of only the catalogue is sufficient, are both important factors. The results of these calculations can help realizing the increasing costs of storage capacities and the transfer bandwidths of preserving and using the attached media files. Based on the findings of this paper, comparisons can be made between the size necessary for running a database, the allocated disc space necessary (and whether the currently allocated disc space is enough), and the size of the different kinds of saved data units. Comparison can also be made between the size of data records in RDBMS, textual data elements, and digitized images. This may lead to the realization that, e.g., the size of 15 digitized images is equal to the size of the dump file of the whole catalogue. The size of the descriptive and administrative metadata is so small in comparison to the size of the media files that it is worthwhile to have as many save files as possible.

When analyzing the results, it needs to be taken into consideration that all examined institutions are using the same integrated collection management system, developed and supported by the same vendor, Qulto Ltd. The examination of databases built by other applications result in different findings. The size of bitstreams depends on the character set, the size of databases depends on their structure, and the size of the used space on hardware devices depends on the database management system. Therefore, the space required for the same catalogue record is not the same in different systems because:

the character set of the application is different,

for the storage of repeatable information, lists of values can be used, while different systems do not always use lists of values for all types of metadata elements,

some technical data, e.g., tags, prefixes, or punctuation, can or cannot be stored in the metadata record itself,

the data themselves can be either on raw devices or in file systems, and the full content records can either be embedded in the database or stored in a filesystem too.

This paper does not aim to make comparisons between different collection management systems, and especially not between systems of different vendors, as one of the authors of this paper is employed by one of them.

9 Conclusions

To summarize the collected information, it can be established that

the average size of the records (both metadata and full content) is similar in the same types of institutions,

there is no noticeable difference between the size of databases and records according to the nationality or ethnicity of the institutions’ users and employees,

the average metadata record size is between 1.1 and 1.6 bytes in the examined museums and libraries,

the average size of the primary data tables of the institutions is between 80 and 130 megabytes, except for county libraries (where the average size is a lot bigger) and school libraries and archival collections, where the size of the data tables is under 25 megabytes,

video files are significantly larger than audio files; audio material is bigger than digital images; but the average size of images is not essentially larger than the average size of text data,

the average record count and the average size of the primary data tables are higher in county libraries than in other types of examined institutions,

there is a strong correlation between the size of the catalogue tables and the size of the whole database.

In the authors’ opinion, it was worth the effort to examine such a high number of databases. It provides opportunity to check whether choosing three dozen databases for representative research produces a similar result. During later research projects, less subjects can be included, selected with great care, thereby sparing time and resources.

9.1 How to Use the Findings

Since hardware costs and the salaries of IT experts are increasing, it is advantageous to plan the needs of present and future projects. Having more information about the databases of museums, libraries, and archival collections is useful for the planning of hybrid systems suitable for libraries, museums, catalogues, and full content repositories. It can be established which are the most widely used datafile formats, for which systems should be developed for preservation and service.

9.2 Information About Prices and Costs

9.2.1 Hardware

The costs of storage devices and other hardware units depend on several factors:

ownership or leasing in the case of storage devices,

additional services, e.g., server hosting and support,

VPN service, domain registration,

user (librarians and customers) demands according to the response time of the user interface,

backup methods (mirroring, RAID technology, or only compressed backup files),

acceptability of lack of services in the case of a breakdown.

Nonetheless, some information should be provided on the prices. Leasing 100 Gigabytes of backup storage in Hungary costs between 20 and 100 Euros per year. The costs of buying hardware for data storage are approximately the same, taking the abandonment of the equipment into consideration.

9.2.2 Software and Human Resources

The software costs of data preservation depend on the user demands and the human resources of the institution. If the capacity of the IT experts of the institution is enough for using freeware or open-source applications, the direct costs of the applications used for data storage, maintenance, use, and search can be relatively low. The other option for the institution is to cut the salary of the IT staff, and pay for user-friendly, well-prepared applications, support services, or cloud-based solutions. Therefore, the bulk of the expenses in both cases is the wages of the staff. When preserving records of several datatypes, the institution will need many kinds of applications for data maintenance, application upgrades, and customer service. Most of these applications will be relatively old, so there will be no support service or distributor for them. Therefore, the experts of the institution will have to work with the special software used for the old, abandoned data units.

9.3 How to Move Forward

In order to obtain more information about the recent and future disk use of integrated collection management systems, further research seems to be necessary. First of all, it could be beneficial to conduct this research once more, thereby acquiring more information about the changes of the average file sizes, the current use of different media and file types, and the growth of the databases regarding metadata and media record count. In order to obtain information about the timespan which is necessary to create new metadata records either by creating it locally or using shared cataloguing possibilities, relevant information should be acquired for cost planning. The changes in the yearly number of loan transactions will provide information on the usage of library documents, which can reveal new aspects of digitization. Hopefully, it will be possible to establish trends for the growth of catalogues and the full contents of databases. It would also be interesting to examine the impact of the changes of data models according to the semantic web. In order to link to one another and augment the concept of authority records, the wider use of the FRBRoo data model seems to be more efficient, thereby being able to spare disk space for storing bitstreams. Another analysis with a different methodology might prove to be necessary as well, to examine the quality of the metadata elements and the validity of the links between them. Hopefully, there will be future opportunities to carry out these further examinations, and, if possible, disclose the findings.

References

Bekiari, C., M. Doerr, P. Le Bœuf, and P. Riva. 2017. Definition of FRBRoo: A Conceptual Model for Bibliographic Information in Object-Oriented Formalism. Version 2.4. Den Haag: IFLA. https://www.ifla.org/publications/node/11240.Suche in Google Scholar

Birkner, M., G. Gonter, K. Lackner, B. Kann, M. Kranewitter, A. Mayer, and A. Parschalk. 2016. “Guideline zur Langzeitarchivierung.” Mitteilungen der Vereinigung Österreichischer Bibliothekarinnen und Bibliothekare 69 (1): 41–57, https://doi.org/10.31263/voebm.v69i1.1396.Suche in Google Scholar

Cattell, R. 2010. “Scalable SQL and NoSQL Data Stores.” ACM SIGMOD Record 39 (4): 12–27, https://doi.org/10.1145/1978915.1978919.Suche in Google Scholar

Fröhlich, S. 2013. “Der Weg ist das Ziel! Planung und Umsetzung digitaler Archivprojekte.” Mitteilungen der Vereinigung Österreichischer Bibliothekarinnen und Bibliothekare 66 (1): 132–44.Suche in Google Scholar

IFLA. 2009. Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. Also available at https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/cataloguing/frbr/frbr_2008.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, E. A. 2014. Constructing the Universal Library. Dissertation. Washington: University of Washington. https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstream/handle/1773/26408/Jones_washington_0250E_13006.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.Suche in Google Scholar

Kopácsi, S., H. Rastislav, and R. Ganguly. 2017. “Implementation of a Classification Server to Support Metadata Organization for Long Term Preservation Systems.” Mitteilungen der Vereinigung Österreichischer Bibliothekarinnen und Bibliothekare 70 (2): 225–43, https://doi.org/10.31263/voebm.v70i2.1897.Suche in Google Scholar

Kouzari, E., and I. Stamelos. 2018. “Process Mining Applied on Library Information Systems: A Case Study.” Library & Information Science Research 40 (3–4): 245–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2018.09.006.Suche in Google Scholar

Kyrillidou, M., C. Cook, and S. Lippincott. 2016. “Capturing Digital Developments through Qualitative Inquiry.” Performance Measurement and Metrics 17 (1): 45–54, https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-03-2016-0007.Suche in Google Scholar

Lei Zeng, M., M. Žumer, A. Salaba, and IFLA Working Group on the Functional Requirements for Subject Authority Data (FRSAD). 2010. Functional Requirements for Subject Authority Records (FRSAR). Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Saur.10.1515/9783110263787Suche in Google Scholar

Mayer, A. 2016. “Workshop: Software-Lösungen zur Langzeitarchivierung und Repositorien-Verwaltung aus Anwendersicht.” Mitteilungen der Vereinigung Österreichischer Bibliothekarinnen und Bibliothekare 69 (1): 151–4, https://doi.org/10.31263/voebm.v69i1.1407.Suche in Google Scholar

Neuroth, H., H. Liegmann, A. Oßwald, R. Scheffel, M. Jehn, and S. Stefan. 2010. Nestor Handbuch: Eine kleine Enzyklopädie der digitalen Langzeitarchivierung. Also available at http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0008-2010071949.Suche in Google Scholar

Oßwald, A. 2014. “Langzeitsicherung digitaler Informationen durch Bibliotheken.” Zeitschrift für Bibliothekswesen und Bibliographie 61 (4–5): 273–7.10.3196/18642950146145194Suche in Google Scholar

Patton, G. 2009. Functional Requirements for Authority Data. Berlin, New York: K.G. Saur.10.1515/9783598440397Suche in Google Scholar

Peng, Z. 2018. Cloud-Based Service for Access Optimization to Textual Big Data. diss., Ann Arbor: Indiana University. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://search.proquest.com/openview/b1b4caa4f56ea7a58f0f3a9b87407e03/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.Suche in Google Scholar

Rasmussen, C. H. 2019. “Is Digitalization the Only Driver of Convergence? Theorizing Relations between Libraries, Archives, and Museums.” Journal of Documentation 75 (6): 1258–73, https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2019-0025.Suche in Google Scholar

Rauber, A., A. Ari, D. van Uytvanck, and S. Pröll. 2016. “Identification of Reproducible Subsets for Data Citation, Sharing and Re-use.” Bulletin of the IEEE Technical Committee on Digital Libraries 12 (1): 1–10.Suche in Google Scholar

Rayward, W. B. 1998. “Electronic Information and the Functional Integration of Libraries, Museums, and Archives.” In History and Electronic Artefacts by E. Higgs, 207–26. Oxford: Clarendon Press. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/9474.Suche in Google Scholar

Riley-Reid, T. D. 2015. “The Hidden Cost of Digitization – Things to Consider.” Collection Building 34 (3): 89–93, https://doi.org/10.1108/CB-01-2015-0001.Suche in Google Scholar

Riva, P., P. Le Bœuf, and M. Žumer. 2017. A Conceptual Model for Bibliographic Information – Definition of a Conceptual Reference Model to Provide a Framework for the Analysis of Non-Administrative Metadata Relating to Library Resources. IFLA. https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/cataloguing/frbr-lrm/ifla-lrm-august-2017_rev201712.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Siegmüller, R. 2007. Verfahren der automatischen Indexierung in bibliotheksbezogenen Anwendungen. Berlin: Institut für Bibliotheks- und Informationswissenschaft der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. http://www.ib.hu-berlin.de/∼kumlau/handreichungen/h214.Suche in Google Scholar

Tripathi, S. 2018. “Digital Preservation: Some Underlying Issues for Long-Term Preservation.” Library Hi Tech News 35 (2): 8–12, https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-09-2017-0067.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 András Simon and Péter Kiszl, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editor’s Introduction, Vol. 50, No. 2

- Feature Articles

- How Digitization is Empowering Vietnamese Cultural Professionals to Preserve, Present, and Promote Art and Culture Online: Navigating Challenges whilst Harnessing Opportunities to Create a Digital Culture

- Aspects of the Long-Term Preservation of Digitized Catalogue Data: Analysis of the Databases of Integrated Collection Management Systems

- Preliminary Evaluation of the Terrestrial Laser Scanning Survey of the Subterranean Structures at Hagia Sophia

- Co-Constructing Digital Archiving Practices for Community Heritage Preservation in Egypt and Iraq

- Book Review

- Jeanne Drewes: Advancing Preservation for Archives and Manuscripts

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editor’s Introduction, Vol. 50, No. 2

- Feature Articles

- How Digitization is Empowering Vietnamese Cultural Professionals to Preserve, Present, and Promote Art and Culture Online: Navigating Challenges whilst Harnessing Opportunities to Create a Digital Culture

- Aspects of the Long-Term Preservation of Digitized Catalogue Data: Analysis of the Databases of Integrated Collection Management Systems

- Preliminary Evaluation of the Terrestrial Laser Scanning Survey of the Subterranean Structures at Hagia Sophia

- Co-Constructing Digital Archiving Practices for Community Heritage Preservation in Egypt and Iraq

- Book Review

- Jeanne Drewes: Advancing Preservation for Archives and Manuscripts