Abstract

The first comparative DFT (B3LYP/6-31G*) study of the Zn-porphyrin and its two derivatives, ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4, is reported. For all three species studied, ZnP, ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4, the singlet was calculated to be the lowest-energy structure and singlet-triplet gap was found to decrease from ca. 41—42 kcal/mol for N to ca. 17—18 kcal/mol for P and to ca. 10 kcal/mol for As. Both ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 were calculated to attain very pronounced bowl-like shapes. The frontier molecular orbitals (MOs) of the core-modified porphyrins are quite similar to the ZnP frontier MOs. For the HOMO-2 of the core-modified porphyrins due to the ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 bowl-like shapes we might suppose the existence of “internal” electron delocalization inside the ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 “bowls”. Noticeable reduction of the HOMO/LUMO gaps was calculated for ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4, by ca. 1.10 and 1.47 eV, respectively, compared to ZnP. The core-modification of porphyrins by P and especially by As was found to result in significant decrease of the charge on Zn-centers, by ca. 0.61—0.67e for P and by ca. 0.69—0.76e for As. Charges on P- and As-centers were computed to have large positive values, ca. 0.41—0.45e and ca. 0.43—0.47e, for P and As, respectively, compared to significant negative values, ca. −0.65 to −0.66e for N. The porphyrin core-modification by heavier N congeners, P and As, can noticeably modify the structures, electronic, and optical properties of porphyrins, thus affecting their reactivity and potential applications.

Introduction

Metalloporphyrins and their derivatives are representatives of the extremely interesting and broad class of 18-π-electron aromatic tetrapyrrole compounds [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. They play the role of cofactors in various enzymes due to their ability to bind metal ions in different oxidation states along with their noticeable structural flexibility allowing them to adopt conformations required for fulfilling specific biological functions [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Tetrapyrroles find numerous applications in catalysis [1], [2], [5], [12], molecular photonics [5], [13], [14], as sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells [2], [5], [14], [15], [16], [17], in artificial photosynthesis [18], [, 19], as sensor devices [20], and in medicine [1], [2], [5]. Their sizes, shapes, and different properties can be fine-tuned by suitable structural modifications. An attractive and promising approach is the modification of the porphyrin core by replacing one or several pyrrole N-atoms with other heteroatoms: chalcogens (O, S, Se, Te), C, and P. The resulting porphyrinoids are known as heteroatom-containing porphyrins or core-modified porphyrins and possess very interesting physicochemical properties and structures that can be quite different from those of regular N4-porphyrins [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. This can result in core-modified porphyrins having promising novel applications. Computational research can be helpful in predicting structures and properties of novel core-modified porphyrins and their derivatives (vide infra, and also see Refs. [26], [, 27]).

Let us consider more closely core modification of porphyrins with the heavier congener of nitrogen, phosphorus. Pyrrole isologue, phosphole C5H5P, was shown to have much lower aromaticity compared to the pyrrole due to insufficient conjugation between the cis-dienic π-system and the P-atom lone electron pair [28]. However, C5H5P possesses several prominent features [28]: (i) a trigonal pyramidal geometry of the P-center due to insufficient n-π interactions; (ii) the effective π*(P–R) – π-π*(1,3-diene) hyperconjugation which lowers the C5H5P lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy compared to the pyrrole LUMO; (iii) C5H5P MOs energies can be easily tuned by different modifications on P-center; and (iv) the P-bridged 1,3-diene unit is rigid, electron rich, and polarizable. The core-modification by P should be considered as a promising strategy for tuning porphyrinoids’ properties.

However, so far studies devoted to the core-modification of porphyrins and their derivatives with P have been relatively scarce. In the series of studies Matano, Nakabuchi, Imahori and co-workers reported syntheses and characterizations of various porphyrins and their derivatives with one pyrrole N replaced by a P-atom [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]. The treatment of the σ3-P,N3-porphyrin with [RhCl(CO)2]2 in CH2Cl2 was shown to give [RhIII-P,N3]Cl2 complex [30]. The P- and S-core-modified σ3-P,S,N2-porphyrin was shown to give the Pd-P,S,N2 complex, and for the S-core-modified S2,N2-porphyrin no complexation was observed [31]. The results were supported by the density functional theory (DFT) studies on model compounds. Similar Ni-P,S,N2 and Pt-P,S,N2 complexes were synthesized as well [31]. The σ3-P,N3-porphyrin (trigonal pyramidal P-center) was shown to to possess a slightly distorted 18π-electron plane and the 22π-electron σ4-P,N3-porphyrin (tetrahedral P-center) was shown to have a highly ruffled structure. Significant structural distortions were also found in the RhIII and PdII complexes of these compounds [29], [, 30]. The metal complexes of these porphyrins were found to exhibit weak antiaromaticity in terms of the magnetic criterion [32], [, 33]. In the 2009 review, Matano and Imahori reported phosphole-containing porphyrins and porphyrinogens as macrocyclic mixed-donor ligands [34]. The investigations of the influence of different combinations of core heteroatoms (P, N, S, and O) on the macrocycle coordination properties showed the P,S,N2-calixpyrroles to behave as monophosphine ligands, whereas the P,X,N2-calixphyrins were shown to behave as neutral, monoanionic, or dianionic tetradentate ligands with electronic structures varying widely depending on the combination of core-modifying elements. It is also worthwhile to mention the 2009 DFT investigation of electronic structure and reactivity for oxidative addition for the Pd complex of P,S-containing hybrid calixphyrin [35]. Also, it is of interest to mention the 2003 DFT study by Delaere and Nguyen of the P-containing porphyrins with one or two pyrrole nitrogens replaced by P [36]. Upon substitution of a NH- by a PH-unit the carbon skeleton of the porphyrin was shown to remain essentially planar, whereas replacement of a N-atom by P-atom caused weak distortion of the ring.

Thus, it can be seen that porphyrins modified with more P atoms could possess intriguing structural, electronic, optical, and, most important, metal-coordinating properties. However, no studies of the completely P-core-modified porphyrins (P4-porphyrins, or P(P)4) have been reported, except the 2012 report by Barbee and Kuznetsov on the NiP(P)4 compound [37]. Motivated by the lack of such studies, Kuznetsov reported the computational investigations of structures, electronic properties, and various complexes formation for the completely P-core-modified metalloporphyrins, MP(P)4, M = Sc-Zn (and also for completely P-core-modified phthalocyanine) [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]. In 2015, the first systematic DFT study of the structures and electronic properties of the MP(P)4 compounds (M = Sc, Ti, Fe, Ni, Cu, and Zn) was reported along with the systematic comparison with the tetrapyrrole MP counterparts [39]. The prominent structural feature of all the MP(P)4 compounds studied was their bowl-like shapes, in sharp contrast to generally planar or slightly distorted MP counterparts. Significant positive charges were computed to be accumulated on P-atoms in MP(P)4 and positive charges on metals in them were found to be noticeably lower than in the MP counterparts. The calculated MP(P)4 HOMO/LUMO and optical gaps were noticeably smaller than the corresponding gaps of their MP counterparts, which was explained by stabilization of the MP(P)4 LUMOs. In the follow-up 2016 work, the comparative DFT study, including Natural Bond Orbitals (NBO) analysis, of the binding energies between the first-row transition metal cations Mn+ (M = Sc-Zn) and two ligands of the similar type, porphine P2- and its completely P-modified counterpart P(P)42−, was reported [40]. The binding energy trends between Mn+ and P(P)42−/P2− were shown to be similar for both ligands. The complete P-core-modification of porphyrins was found to decrease the Mn+-ligand binding energies; however, all the MP(P)4 compounds studied were shown to be stable according to the calculated Ebind values. Also in 2016, motivated by the phenomenon of stack formation by regular metalloporphyrins, the stack formation between ZnP(P)4 species without any linkers or substituents was found computationally [41]. Three modes of coordination were found to be possible. The dimer with the monomeric ZnP(P)4 units oriented by their Zn-centers toward each other was found to be the most stable species. Next year, motivated by numerous examples of the complex formation between regular metalloporphyrins and fullerenes, Kuznetsov computationally investigated possibility of the complex formation between ZnP(P)4 and NiP(P)4 and C60 without any linkers, both in the gas phase and with implicit effects from C6H6 [42]. The binding energies in the MP(P)4-C60 complexes were computed to be relatively small, ca. 1–1.6 kcal/mol and ca. 5 kcal/mol for M = Zn and Ni, respectively (CAM-B3LYP method). The ZnP(P)4 species was found to be noticeably distorted in the complex whereas NiP(P)4 inside the NiP(P)4-C60 complex essentially retained its bowl-like shape. Next, motivated by the phenomenon of numerous complexes formation between tetrapyrroles and nanoparticles (NPs), Kuznetsov computationally studied the complex formation between two core-modified ZnP(X)4 species (X = P and S) without any substituents or linkers and small NP Zn6S6 [43]. The complex formation was investigated with two theoretical approaches, B3LYP/6-31G* and CAM-B3LYP/6-31G*, both in the gas phase and with implicit effects from benzene. Both complexes were found to be quite strongly bound, with binding energies varying from ca. 29 up to ca. 69 kcal/mol. In general, the shape of the ZnP(S)4 porphyrin macrocycle was considered as more favorable for the stronger binding between the NP and core-modified porphyrin. Very recently, Kuznetsov performed DFT studies on the P-core-modified and S-core-modified phthalocyanines (Pc) ZnPcs, ZnPc(P)4 and ZnPc(S)4, using B3LYP and two dispersion-corrected functionals, wB97XD and CAM-B3LYP. Also, computational study of the complexes between C60 and ZnPc(P)4 and ZnPc(S)4 was done. The size of the “bowl” cavity of the both core-modified phthalocyanines was found to be essentially the same. The calculated binding energies of the complexes optimized using the CAM-B3LYP and wB97XD varied within ca. 14–52 kcal/mol and were generally by ca. 8.5—12.4 kcal/mol higher for the C60-ZnPc(S)4 complex.

Thus, motivated by the above-presented studies on P-core-modified porphyrins and their derivatives, we decided to perform first comparative DFT studies of the regular porphyrin, ZnP, and its two analogs modified with the heavier congeners of nitrogen: P, ZnP(P)4, and As, ZnP(As)4. We want to emphasize here that our goal was to make comparisons between the ZnP species and its core-modified analogs, ZnP(P)4, taken for comparison purposes, and ZnP(As)4, which has never been studied before, computationally or experimentally, from the point of view of their structures and some electronic (frontier molecular orbitals and orbital gaps, energy gaps, charges) and optical (peaks and gaps calculated by time-dependent DFT) properties. The more profound studies are planned for the follow-up research and are currently being undertaken.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we describe the computational approaches employed. Then we address energetics of ZnP, ZnP(P)4, and ZnP(As)4 and compare their structural features. Afterward we consider some of their molecular orbitals, HOMO/LUMO gaps, and optical gaps, and also NBO charges. Finally, we summarize the research findings and discuss further research perspectives.

Theoretical methods

The study reported here was performed using the Gaussian 09 package, revision B.01 [44]. The ZnP, ZnP(P)4, and ZnP(As)4 species (both singlets and triplets) were optimized without any symmetry constraints, and the resulting structures were assessed using vibrational frequency analysis to check whether or not the optimized structures represented true minimum-energy geometries.

We performed the geometry optimizations and frequencies calculations using the hybrid functional B3LYP [45], [, 46] with the split-valence polarized 6-31G* basis set [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], furthermore referred to as B3LYP/6-31G*. Previously, the B3LYP/6-31G* approach was proved to give metalloporphyrin geometries in good agreement with experimental data (see, e.g., Ref. [54]): thus, Kozlowski et al. demonstrated applying the B3LYP/6-31G* approach to several unsubstituted planar MPs (M = Cr-Zn) that the computed range of M-N bond distances, 1.96–2.09 Å, covered essentially the range of experimentally observed values [54]. This approach was also shown by Hirao and co-workers to produce the ordering of spin states of metalloporphyrin complexes reasonably well [55].

Geometry optimizations and frequencies calculations, also for comparison purposes, were performed in the gas phase and with implicit effects of two solvents with differing polarities, benzene and dichloromethane, taken into account (dielectric constants ε(C6H6) = 2.2706 and ε(CH2Cl2) = 8.93) using the self-consistent reaction field IEF-PCM method [56]. The UFF default model used in the Gaussian 09 package, with the electrostatic scaling factor α set to 1.0, was employed. These solvents were chosen because organic syntheses and characterization are often performed using them.

Below we consider the B3LYP/6-31G* results without the zero-point correction ZPE. The charge distribution analysis was performed using the Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) scheme with the ‘pop = nbo’ command as implemented in the Gaussian 09 package [57], [, 58]. Molecular orbitals (MOs) for the ground state structures were calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G* level in the gas phase on the B3LYP/6-31G* optimized geometries. Molecular structures and MOs were visualized using OpenGL version of Molden 5.8.2 visualization software [59].

Results and discussion

Electronic states and structural features

In Table 1 characteristics of the ZnP(X)4 (X = N, P, As) species calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory are presented, and Fig. 1 shows the calculated lowest-lying (singlet) structures of ZnP(X)4, with selected structural parameters, at the B3LYP/6-31G* level. From Table 1 it can be seen that for the ZnP(X)4 compounds singlet is the global structure for all three X = N, P, As, although the singlet-triplet gap decreases steadily from X = N to As: from ca. 41—42 kcal/mol for N to ca. 17—18 kcal/mol for P and to ca. 10 kcal/mol for As. Implicit solvent effects non-significantly decrease the singlet-triplet gap values keeping the same trend.

ZnP(X)4 compounds (X = N, P, As) (B3LYP/6-31G* approach, gas phase//C6H6//CH2Cl2).

| Species | ΔE, kcal/mol | E(HOMO/LUMO), A.U. | ΔE(HOMO/LUMO), eV | TDDFT gap, eVa | NBO, e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | X | |||||

| ZnP, 1A | 0.0// 0.0// 0.0 |

−0.19154/−0.07860// −0.19229/−0.07953// −0.19377/−0.08148 |

3.07// 3.07// 3.06 |

2.45(w)b, 3.55.3.85// 2.44(w), 3.35.3.83// 2.44(w), 3.37.3.83 |

1.284// 1.303// 1.325 |

−0.654// −0.655// −0.657 |

| ZnP, 3A | 42.10// 41.80// 41.10 |

−0.12626/−0.08342 −0.19331/−0.14738// −0.12749/−0.08404 −0.19437/−0.14757// −0.12875/−0.08469 −0.19570/−0.14757 |

||||

| ZnP(P)4, 1A | 0.0// 0.0// 0.0 |

−0.18048/−0.10810// −0.18031/−0.10786// −0.18113/−0.10863 |

1.97// 1.97// 1.97 |

1.29(w), 2.07(w), 2.71// 1.29(w), 2.07(w), 2.69// 1.29(w), 2.06(w), 2.69 |

0.615// 0.657// 0.717 |

0.450// 0.434// 0.410 |

| ZnP(P)4, 3A | 17.71// 17.56// 17.29 |

−0.15358/−0.10338 −0.20178/−0.13690// −0.15339/−0.10349 −0.20169/−0.13648// −0.15401/−0.10430 −0.20245/−0.13717 |

||||

| ZnP(As)4, 1A | 0.0// 0.0// 0.0 |

−0.16935/−0.11067// −0.16900/−0.11037// −0.16944/−0.11073 |

1.60// 1.60// 1.60 |

0.94(w)b, 1.99.2.47// 0.94(w), 1.98.2.47// 0.94(w), 1.98.2.47 |

0.523// 0.570 //0.632 |

0.469// 0.450// 0.429 |

| ZnP(As)4, 3A | 9.90// 9.89// 9.82 |

−0.15521/−0.10495 −0.19823/−0.12757// −0.15498/−0.10447 −0.19787/−0.12721// −0.15537/−0.10476 −0.19827/−0.12753 |

||||

-

aWe provide here values for the several first peaks in the TDDFT results, with oscillator strength in the range 0.001–0.1.

b“w” means the weak peaks, with oscillator strength less than 0.01.

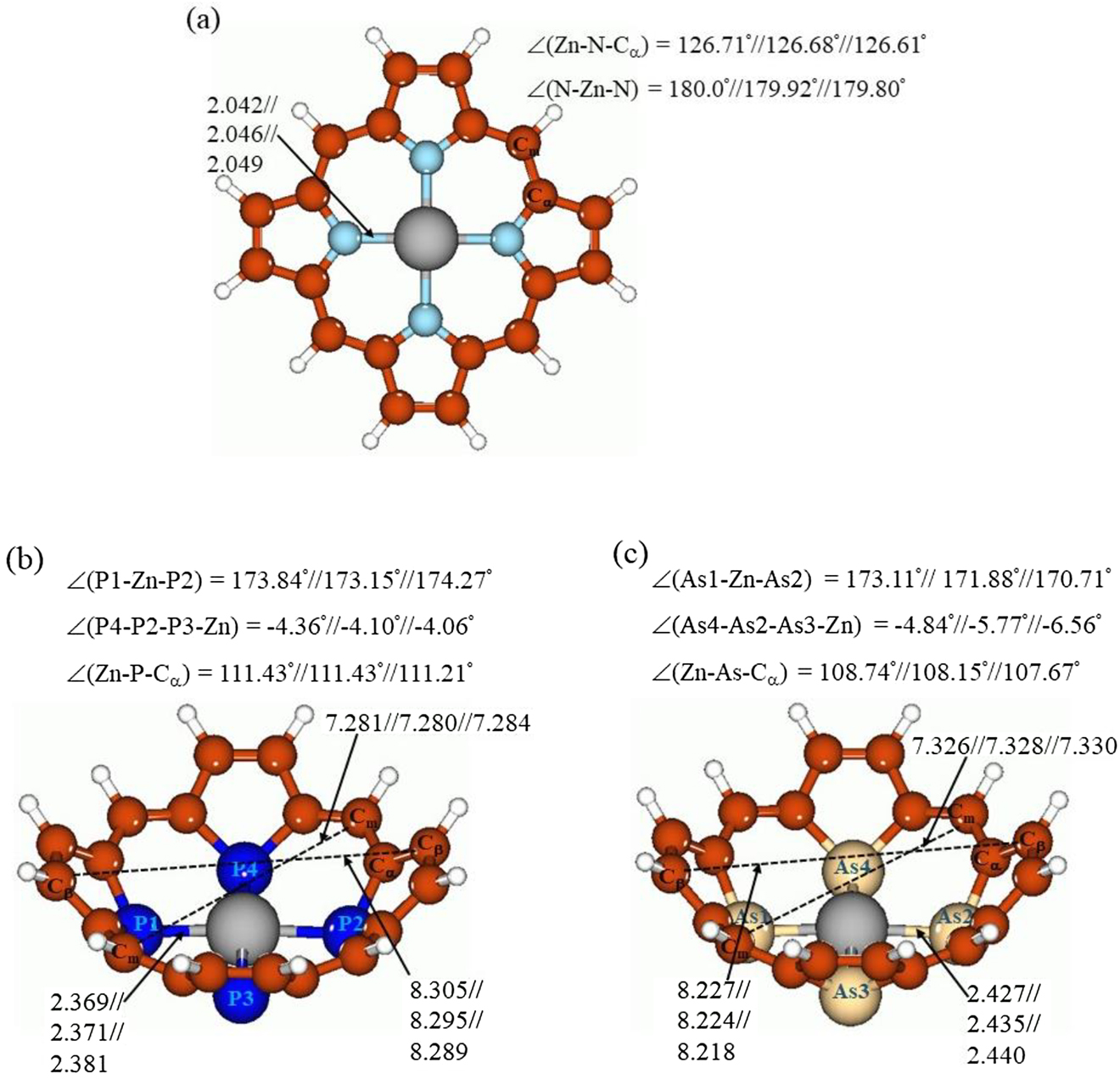

Calculated singlet structures of ZnP(X)4 (X = N (a), P (b), and As (c)), with selected structural parameters, at the B3LYP/6-31G* level, in the gas phase//C6H6//CH2Cl2. Bond distances are given in Å, bond angles and dihedral angles are given in degrees. Color coding: gray for Zn, light blue for N, dark blue for P, light brown for As, brown for C, and white for H.

Comparison of the structural features of the porphyrins ZnP(X)4 (Fig. 1) shows drastic changes upon replacement of N with its heavier congeners. (i) Both ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 attain very pronounced bowl-like shape, which was found earlier for different completely P-core-modified porphyrins (see Refs. [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]). While the original ZnP species is essentially planar, which can be seen from the value of its valence angle N-Zn-N, which is essentially equal to 180° both in the gas phase and with two implicit solvents used (Fig. 1a), for ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 the values of the valence angles P-Zn-P and As-Zn-As noticeably differ from 180°, being 173.84°//173.15°//174.27° and 173.11°//171.88°//170.71°, respectively (gas phase//C6H6//CH2Cl2) (Fig. 1b, c). Interestingly, for X = P the value of the P-Zn-P angle first slightly decreases when going from the gas phase to implicit benzene and then slightly increases from implicit benzene to implicit CH2Cl2, whereas for X = As steady slight decrease of the As-Zn-As angle value was calculated. (ii) The values of the dihedral angles, X4-X2-X3-Zn (Fig. 1b,c), which were used as measure of Zn entering the “bowl”, show the slight protrusion of Zn inside the molecular bowls, being −4.36°//−4.10°//−4.06° for X = P and −4.84°//−5.77°//−6.56° for X = As. While for X = P steady slight decrease of the dihedral angle value is observed from the gas phase to benzene to dichloromethane, for X = As steady slight increase was calculated. (iii) The Zn-X bond distances steadily increase from X = N to X = As, by 0.327—0.332 and 0.378—0.391 Å for P and As, respectively (cf. Fig. 1a–c). For all three X’s, the Zn-X bond distances increase steadily when going from the gas phase to implicit C6H6 and to implicit CH2Cl2. (iv) Because of the decrease of the atom pyramidality from N to P to As, the value of the valence angle Zn-X-Cα noticeably decreases from N to P to As, by 15.28—15.40° and 17.97—18.94° for X = P and As, respectively (cf. Fig. 1a–c). For X = As, this angle slightly decreases from the gas phase to implicit benzene to implicit dichloromethane, whereas for X = N and P it remains almost the same. (v) Also, it is interesting to notice that the distances Cm-Cm and Cβ-Cβ between the opposite sides of the porphyrin macrocycle taken as the measure of the porphyrin “bowl” size (see Fig. 1b, c for notations), are quite close for the both ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 species (Fig. 1b, c). For ZnP(As)4 the Cm-Cm distances are elongated by 0.045—0.048 Å and the Cβ-Cβ distances are shortened by 0.071—0.078 Å compared to ZnP(P)4. From the gas phase through implicit C6H6 and to implicit CH2Cl2, both Cm-Cm and Cβ-Cβ distances are steadily shortened. (vi) Thus, the main structural difference between ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 is in the “bottom part” of the molecular bowl because in the former species Zn protrudes inside a little less than the latter. Also, there is the little difference in the size of “rim” of the porphyrin “bowl”.

It can be supposed that both ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 due to their pronounced bowl-like distortions may serve as good receptors for various species, e.g., nanoparticles, fullerenes, or small molecules (H2, O2, hydrocarbons, etc.). For the ZnP(P)4 species the ability to act as a receptor for semiconductor nanoparticles exemplified by Zn6S6 [43] and fullerene C60 [42] was already demonstrated computationally, and more similar research is currently under way.

Frontier molecular orbitals and NBO charges

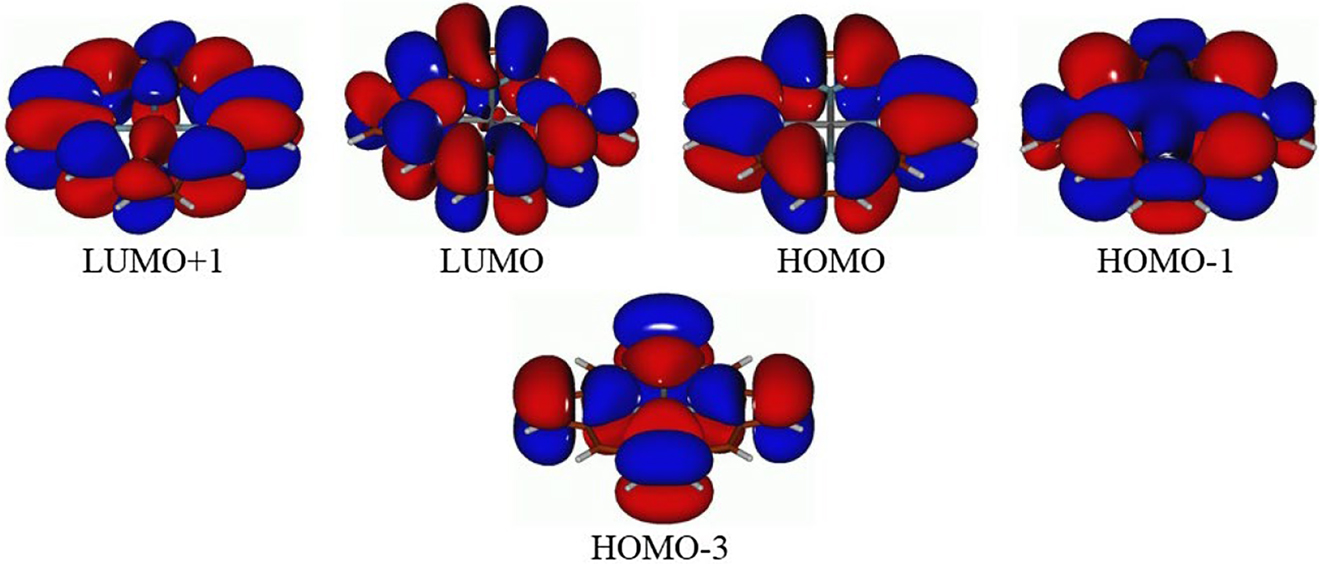

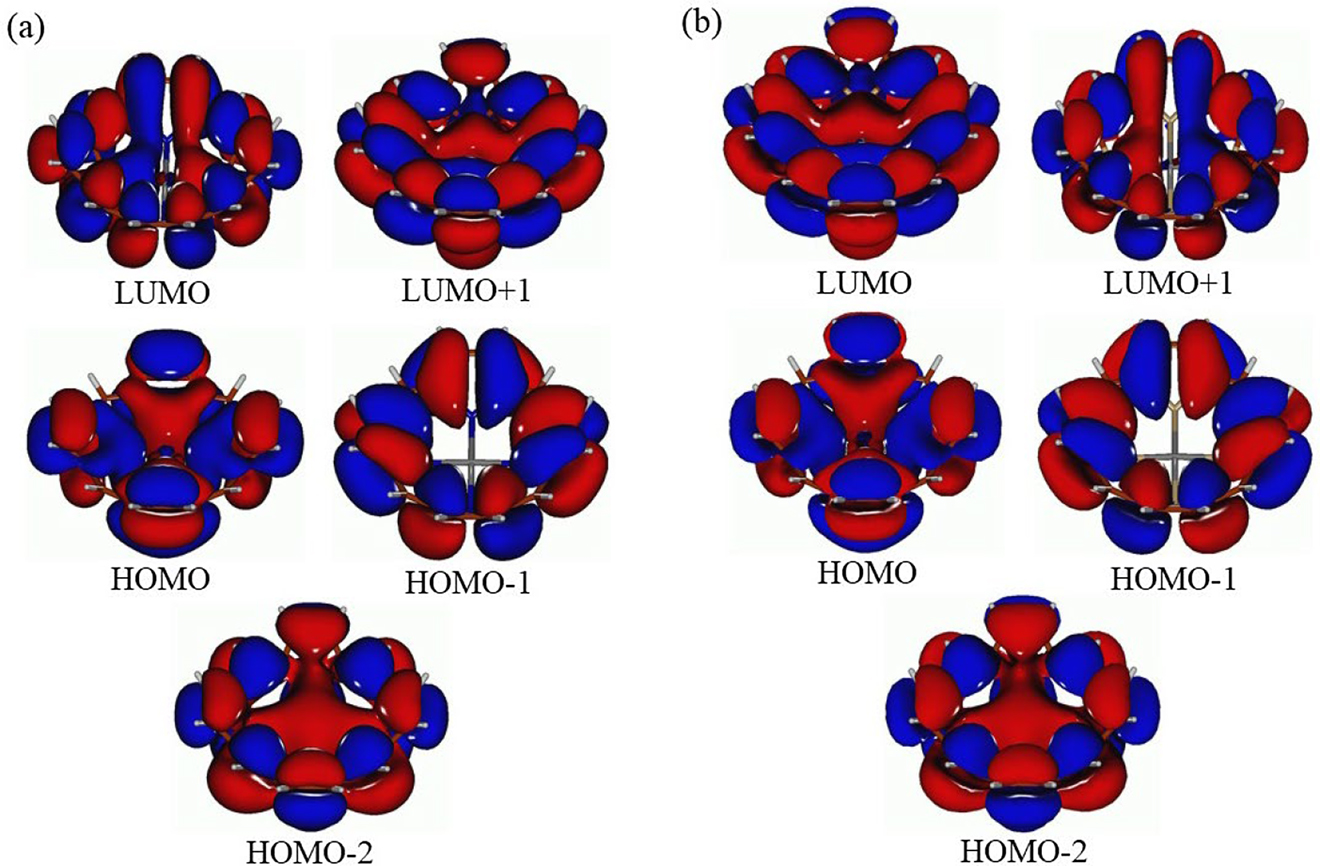

In Figs. 2 and 3 several MOs with similar shapes are shown for ZnP (Fig. 2) and ZnP(P)4 (Fig. 3a) and ZnP(As)4 (Fig. 3b). Consideration and comparison of these MOs along with the data from Table 1 leads to the following conclusions. (i) Replacement of N by P/As in the porphyrin core (core-modification with P or As) essentially does not affect noticeably both the shape and composition of the MOs considered. Noticeable similarity can be seen between the ZnP HOMO and HOMO-3, on one side, and the ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 HOMO and HOMO-1, on another side. Only the MOs ordering is changed for the core-modified analogs of ZnP. (ii) The ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 HOMO-2 is the analog of the ZnP HOMO-1. Because of the ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 bowl-like shapes we might suppose the existence of “internal” electron delocalization (or “internal” aromaticity, although this hypothesis requires further investigations) inside the ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 “bowls” (see Fig. 3). (iii) The ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 LUMO and LUMO+1 are similar to the ZnP LUMO/LUMO+1 (cf. Figs. 2 and 3), some differences seen in the ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 LUMO and LUMO+1 can be explained by the bowl-like distortions of ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4. (iv) Noticeable closure of the HOMO/LUMO gaps was calculated to occur in the ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 species, by ca. 1.10 and 1.47 eV, respectively, compared to ZnP (see Table 1). This can be explained by quite significant HOMO destabilization and LUMO stabilization for ZnP(P)4 [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43] and ZnP(As)4 compared to ZnP. Furthermore, from the TDDFT results we can see that the TDDFT gaps (designated either by appearance of the first weak peak (oscillator strengths less than 0.01) or by the first strong peak (oscillator strengths 0.01—0.1) also reduce steadily from ZnP to ZnP(P)4 and further to ZnP(As)4 (Table 1). (v) The implicit solvent effects on the HOMO/LUMO and TDDFT gaps can be essentially neglected.

Frontier molecular orbitals along with HOMO-1, HOMO-3, and LUMO+1 of the ZnP species.

Frontier molecular orbitals along with HOMO-1, HOMO-2, and LUMO+1 of the ZnP(P)4 (a) ZnP(As)4 (b) and species.

Furthermore, comparison of the calculated NBO charges, provided in Table 1, shows the following. (i) The core-modification of porphyrins by P and especially by As results in significant decrease of the charge on Zn-centers, by ca. 0.61—0.67e for P and by ca. 0.69—0.76e for As. (ii) Charges on P- and As-centers have large positive values, ca. 0.41—0.45e and ca. 0.43—0.47e, for P and As, respectively, compared to significant negative values, ca. −0.65 to −0.66e for N. This can be clearly explained by decreasing electronegativies (by Pauling scale) from N (3.04) to P (2.19) and further to As (2.18) [60] and by increasing covalent radii (in pm) from N (71) to P (107) and to As (119) [61]. (iii) With the implicit solvent effects included, the calculated NBO charges steadily increase from the gas phase to benzene and further to CH2Cl2.

The above-considered results show as well that the porphyrin core-modification by heavier N congeners, P and As, can modify the porphyrin electronic and optical properties, thus affecting their reactivity and potential applications. More detailed TDDFT studies of UV–vis spectra of these compounds are necessary to shed more light on how their properties can be changed/tuned by the core-modification with P and As.

Conclusions

We have performed the first comparative DFT (B3LYP/6-31G*) study of the Zn-porphyrin and its two derivatives, ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4, investigating in details the effects of core-modification by the heavier N congeners, P and As, on the structures, electronic, and optical properties, and charge distribution in porphyrin molecules, both in the gas phase and with effects from two implicit solvents, benzene and dichloromethane, included. The results of this computational study can be summarized as follows.

For all three species studied, ZnP, ZnP(P)4, and ZnP(As)4, the singlet was calculated to be the lowest-energy structure. The singlet-triplet gap was found to decrease from ca. 41—42 kcal/mol for N to ca. 17—18 kcal/mol for P and to ca. 10 kcal/mol for As. Implicit solvents were found not to have significant effects on the singlet-triplet gap values.

Both ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 were calculated to attain very pronounced bowl-like shapes, which was found earlier for completely P-core-modified porphyrins [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]. The values of the dihedral angles, X4-X2-X3-Zn (Fig. 1b, c) show the slight protrusion of Zn inside the molecular bowls. The Zn-X bond distances were calculated to steadily increase from X = N to X = As, by 0.327—0.332 and 0.378—0.391 Å for P and As, respectively (cf. Fig. 1a–c). For all three X’s, the Zn-X bond distances were computed to increase steadily when going from the gas phase to implicit C6H6 and to implicit CH2Cl2.

The distances Cm-Cm and Cβ-Cβ between the opposite sides of the porphyrin macrocycle (see Fig. 1b, c for notations), were found to be quite close for the both ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 species. For ZnP(As)4 the Cm-Cm distances are elongated by 0.045—0.048 Å and the Cβ-Cβ distances are shortened by 0.071—0.078 Å compared to ZnP(P)4. From the gas phase through implicit C6H6 and to implicit CH2Cl2, both Cm-Cm and Cβ-Cβ distances are steadily shortened.

The main structural difference between ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 was found to be in the “bottom part” of the molecular bowl because in the former species Zn protrudes inside a little less than the latter. Also, there is the little difference in the size of “rim” of the porphyrin “bowl”.

Core-modification with P or As was found not to affect noticeably both the shape and composition of the MOs considered. Significant similarity can be seen between the ZnP HOMO and HOMO-3 and the ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 HOMO and HOMO-1. Only the MOs ordering is changed for the core-modified analogs of ZnP.

The ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 HOMO-2 is the analog of the ZnP HOMO-1. Because of the ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 bowl-like shapes we might suppose the existence of “internal” electron delocalization (or “internal” aromaticity, although this hypothesis re quires further investigations) inside the ZnP(P)4/ZnP(As)4 “bowls” (see Fig. 3).

Noticeable closure of the HOMO/LUMO gaps was calculated to occur in the ZnP(P)4 and ZnP(As)4 species, by ca. 1.10 and 1.47 eV, respectively, compared to ZnP (see Table 1). This can be explained by quite significant HOMO destabilization and LUMO stabilization for ZnP(P)4 [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43] and ZnP(As)4 compared to ZnP. Furthermore, from the TDDFT results we can see that the TDDFT gaps also reduce steadily from ZnP to ZnP(P)4 and further to ZnP(As)4 (Table 1). The implicit solvent effects on the HOMO/LUMO and TDDFT gaps can be essentially neglected.

The core-modification of porphyrins by P and especially by As results in significant decrease of the charge on Zn-centers, by ca. 0.61—0.67e for P and by ca. 0.69—0.76e for As. Charges on P- and As-centers were computed to have large positive values, ca. 0.41—0.45e and ca. 0.43—0.47e, for P and As, respectively, compared to significant negative values, ca. −0.65 to −0.66e for N. This can be clearly explained by decreasing electronegativies from N to P and further to As and by increasing covalent radii from N to P and to As. With the implicit solvent effects included, the calculated NBO charges steadily increase from the gas phase to benzene and further to CH2Cl2.

Thus, from the results obtained it can be seen that porphyrin core-modification by heavier N congeners, P and As, can noticeably modify the structures, electronic and optical properties of porphyrins, thus affecting their reactivity and potential applications. For instance, we can suppose that this core-modification can make the modified porphyrins act as good receptors for various species, e.g., nanoparticles, fullerenes, or small molecules (H2, O2, hydrocarbons, etc.).

Based on these conclusions, the following perspective directions of studies can be formulated.

To study in details electronic structure and aromaticity of the P- and As-core-modified porphyrins.

To investigate the effects of various electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituents on structures and various properties of the P- and As-core-modified porphyrins.

To extend studies of core-modified porphyrins to other core-modifying elements, e.g., S, Se, Te, Sb.

To study in more details formation of various complexes of core-modified porphyrins, first of all, with small nanoparticles, fullerene C60, graphene, and small molecules.

Some of these studies are being undertaken currently.

Article note

A collection of peer-reviewed articles by past winners of the IUPAC and IUPAC-SOLVAY International Award for Young Chemists to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

Funding source: Universidad Tecnica Federica Santa Maria (USM)

Acknowledgments

The computational resources of the supercomputer facilities at Instituto Tecnologica de Aeronautica (ITA) are highly appreciated.

-

Research funding: The author deeply acknowledges the financial support of the Universidad Tecnica Federica Santa Maria (USM), Santiago, Chile.

References

[1] The Porphyrins, D. Dolphin (Ed.), Academic, New York (1978).Suche in Google Scholar

[2] The Porphyrin Handbook, K. M. Kadish, K. M. Smith, R. Guilard (Eds.), pp. 1–6, Academic Press, San Diego, CA (2000).Suche in Google Scholar

[3] I. Bertini, H. B. Gray, S. J. Lippard, S. J. Valentine. Bioinorganic Chemistry, University Science Book, Mill Valley, CA (1994).Suche in Google Scholar

[4] S. Severance, I. Hamza. Chem. Rev.109, 4596 (2009).10.1021/cr9001116Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Handbook of Porphyrin Science with Applications to Chemistry, Physics, Materials Science, Engineering, Biology and Medicine, K. M. Kadish, , K. M. Smith, R. Guilard (Eds.), World Scientific, Singapore (2010).Suche in Google Scholar

[6] K. R. Rodgers. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol.3, 158 (1999).Suche in Google Scholar

[7] J. A. Hoy, H. Robinson, J. T. TrentIII, S. Kakar, B. J. Smagghe, M. S. Hargrove. J. Mol. Biol.371, 168 (2007).10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.029Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] A. S. Tsiftsoglou, A. I. Tsamadou, L. C. Papadopoulou. Pharmacol. Ther.111, 327 (2006).10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] M. T. Wilson, B. J. Reeder. Exp. Physiol.93, 128 (2008).10.1113/expphysiol.2007.039735Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] M. Faller, M. Matsunaga, S. Yin, J. A. Loo, F. Guo. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.14, 23 (2007).10.1038/nsmb1182Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] K. Kitanishi, J. Igarashi, K. Hayasaka, N. Hikage, I. Saiful, S. Yamauchi, T. Uchida, K. Ishimori, T. Shimizu. Biochemistry47, 6157 (2008).10.1021/bi7023892Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Phthalocyanines: Properties and Applications, C. C. Leznoff, A. B. P. Lever (Eds.), pp. 1–4, VCH Publishers, New York (1989).Suche in Google Scholar

[13] M. O. Senge, M. Fazekas, E. G. A. Notaras, W. J. Blau, M. Zawadzka, O. B. Locos, E. M. N. Mhuircheartaigh. Adv. Mater.19, 2737 (2007).10.1002/adma.200601850Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Z. Zhoua, Z. Shen. 2015. J. Mater. Chem. C3, 3239.10.1039/C5TC00115CSuche in Google Scholar

[15] H. Imahori, T. Umeyama, S. Ito. Acc. Chem. Res.42, 1809 (2009).10.1021/ar900034tSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] W. J. Youngblood, S.-H. Anna Lee, M. Kazuhiko, T. E. Mallouk. Acc. Chem. Res.42, 1966 (2009).10.1021/ar9002398Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] T. Higashinoa, H. Imahori. Dalton Trans.44, 448 (2015).10.1039/C4DT02756FSuche in Google Scholar

[18] M. R. Wasielewski. Acc. Chem. Res.42, 1910 (2009).10.1021/ar9001735Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] N. Aratani, D. Kim, A. Osuka. Acc. Chem. Res.42, 1922 (2009).10.1021/ar9001697Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Y. Ding, W.-H. Zhu, Y. Xie. Chem. Rev.117, 2203 (2017).10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] L. Latos-Grażyński. in The Porphyrin Handbook, K. M. Kadish, K. M. Smith, R. Guilard, (Eds.), pp. 361–416, Academic Press, New York (2000).Suche in Google Scholar

[22] I. Gupta, M. Ravikanth. Coord. Chem. Rev.250, 468 (2006).10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.010Suche in Google Scholar

[23] B. Szyszko, L. Latos-Grażyński. Chem. Soc. Rev.44, 3588 (2015).10.1039/C4CS00398ESuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] P. J. Chmielewski, L. Latos-Grażyński. Coord. Chem. Rev.249, 2510 (2005).10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.015Suche in Google Scholar

[25] T. Chatterjee, V. S. Shetti, R. Sharma, M. Ravikanth. Chem. Rev.117, 3254 (2017).10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00496Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Kuznetsov, A. E., in: Akitsu, T. (Ed.), Descriptive Inorganic Chemistry Researches of Metal Compounds, InTech, 2017, pp. 135–152. ISBN 978-953-51-3398-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Al. E. Kuznetsov. Adv. Chem. Res.57, 1 (2019).10.1134/S0010952519010064Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Y. Matano, H. Imahori. Org. Biomol. Chem.7, 1258 (2009).10.1039/b819255nSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Y. Matano, T. Nakabuchi, H. Imahori. Pure Appl. Chem.82, 583 (2010).10.1351/PAC-CON-09-08-05Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Y. Matano, T. Nakabuchi, H. Imahori. Unpublished results.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Y. Matano, T. Nakabuchi, S. Fujishige, H. Nakano, H. Imahori. J. Am. Chem. Soc.130, 16446 (2008).10.1021/ja807742gSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Y. Matano, T. Miyajima, N. Ochi, T. Nakabuchi, M. Shiro, Y. Nakao, S. Sakaki, H. Imahori. J. Am. Chem. Soc.130, 990 (2008).10.1021/ja076709oSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Y. Matano, T. Miyajima, T. Nakabuchi, H. Imahori, N. Ochi, S. Sakaki. J. Am. Chem. Soc.128, 11760 (2006).10.1021/ja0640039Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Y. Matano, H. Imahori. Acc. Chem. Res.42, 1193 (2009).10.1021/ar900075eSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] N. Ochi, Y. Nakao, H. Sato, Y. Matano, H. Imahori, S. Sakaki. J. Am. Chem. Soc.131, 10955 (2009).10.1021/ja901166aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] D. Delaere, M. T. Nguyen. Chem. Phys. Lett.376, 329 (2003).10.1016/S0009-2614(03)01012-1Suche in Google Scholar

[37] J. Barbee, A. E. Kuznetsov. Comput. Theor. Chem.981, 73 (2012).10.1016/j.comptc.2011.11.049Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Kuznetsov, A. E., Phys. Sci. Rev.4 (2019) 20190001.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] A. E. Kuznetsov. Chem. Phys.447, 36 (2015).10.1016/j.chemphys.2014.11.018Suche in Google Scholar

[40] A. E. Kuznetsov. Chem. Phys.469–470, 38 (2016).10.1136/inp.i5051Suche in Google Scholar

[41] A. E. Kuznetsov. J. Theor. Comput. Chem.15, 1650043 (2016).10.1142/S0219633616500437Suche in Google Scholar

[42] A. E. Kuznetsov. J. Appl. Solut. Chem. Model.6, 91 (2017).10.6000/1929-5030.2017.06.03.1Suche in Google Scholar

[43] A. E. Kuznetsov. in Density Functional Theory, R. Ponnadurai (Ed.), pp. 135–146, De Gruyter (2018).10.1515/9783110568196-009Suche in Google Scholar

[44] M. J. Frisch, G. W Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, G Scalmani, V. Barone, B. Mennucci, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, M. Caricato, X. Li, H. P. Hratchian, A. F. Izmaylov, J. Bloino, G. Zheng, J. L. Sonnenberg, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, J. A. Montgomery Jr., J. E. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. Bearpark, J. J. Heyd, E. Brothers, K. N. Kudin, V. N. Staroverov, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. Rendell, J. C. Burant, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, N. Rega, J. M. Millam, M. Klene, J. E. Knox, J. B. Cross, V. Bakken, C. Adamo, J. Jaramillo, R. Gomperts, R. E. Stratmann, O. Yazyev, A. J. Austin, R. Cammi, C. Pomelli, J. W. Ochterski, R. L. Martin, K. Morokuma, V. G. Zakrzewski, G. A. Voth, P. Salvador, J. J. Dannenberg, S. Dapprich, A. D. Daniels, Ö. Farkas, J. B. Foresman, J. V. Ortiz, J. Cioslowski, D. J. Fox, Gaussian, Inc, Wallingford CT (2010).Suche in Google Scholar

[45] A. D. Becke. J. Chem. Phys.98, 5648 (1993).10.1063/1.464913Suche in Google Scholar

[46] R. G. Parr, W. Yang. Density-Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1989).Suche in Google Scholar

[47] A. D. McLean, G. S. Chandler. J. Chem. Phys.72, 5639 (1980).10.1063/1.438980Suche in Google Scholar

[48] K. Raghavachari, J. S. Binkley, R. Seeger, J. A. Pople. J. Chem. Phys.72, 650 (1980).10.1063/1.438955Suche in Google Scholar

[49] R. Ditchfield, W. J. Hehre, J. A. Pople. J. Chem. Phys.54, 724 (1971).10.1063/1.1674902Suche in Google Scholar

[50] W. J. Hehre, R. Ditchfield, J. A. Pople. J. Chem. Phys.56, 2257 (1972).10.1063/1.1677527Suche in Google Scholar

[51] P. C. Hariharan, J. A. Pople. Mol. Phys.27, 209 (1974).10.1080/00268977400100171Suche in Google Scholar

[52] M. S. Gordon. Chem. Phys. Lett.76, 163 (1980).10.1016/0009-2614(80)80628-2Suche in Google Scholar

[53] P. C. Hariharan, J. A. Pople. Acta28, 213 (1973).10.1007/BF00533485Suche in Google Scholar

[54] P. M. Kozlowski, J. R. Bingham, A. A. Jarzecki. J. Phys. Chem.112, 12781 (2008).10.1021/jp801696cSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] S. Myradalyyev, T. Limpanuparb, X. Wang, H. Hirao. Polyhedron52, 96 (2013).10.1016/j.poly.2012.11.018Suche in Google Scholar

[56] B. Mennucci, J. Tomasi. J. Chem. Phys.106, 5151 (1997).10.1063/1.473558Suche in Google Scholar

[57] A. E. Reed, L. A. Curtiss, F. Weinhold. Chem. Rev.88, 899 (1988).10.1021/cr00088a005Suche in Google Scholar

[58] A. E. Reed, R. B. Weinstock, F. Weinhold. J. Chem. Phys.83, 735 (1985).10.1063/1.449486Suche in Google Scholar

[59] G. Schaftenaar, J. H. Noordik. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Design14, 123 (2000).10.1023/A:1008193805436Suche in Google Scholar

[60] CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, D. R. Lide (Ed.), CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 84th ed. (2003).Suche in Google Scholar

[61] P. Pyykkö, M. Atsumi. Chem. Eur J.15, 186 (2009).10.1002/chem.200800987Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Special topic paper

- State-of-the-art progress in tracking plasmon-mediated photoredox catalysis

- Invited papers

- Leading by example

- A blueprint for green chemists: lessons from nature for sustainable synthesis

- Synthetic approaches to 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF): a stable bio-based diol

- Conference papers

- Virtual Conference on Chemistry and its Applications VCCA-2020

- Comparison of P- and As-core-modified porphyrins with the parental porphyrin: a computational study

- Data curation to improve the pattern recognition performance of B-cell epitope prediction by support vector machine

- Molecular insights of metal–metal interactions in transition metal complexes using computational methods

- Structure, electronic and optical properties of chalcopyrite-type nano-clusters XFeY2 (X=Cu, Ag, Au; Y=S, Se, Te): a density functional theory study

- An efficient nanofiltration system containing mixture of rice husk ash and Fe/CeO2–SiO2 nanocomposite for the removal of azo dye and pesticide

- Synthesis and comparative study on the antibacterial activity organotin(IV) 3-hydroxybenzoate compounds

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Interpretation and use of standard atomic weights (IUPAC Technical Report)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Special topic paper

- State-of-the-art progress in tracking plasmon-mediated photoredox catalysis

- Invited papers

- Leading by example

- A blueprint for green chemists: lessons from nature for sustainable synthesis

- Synthetic approaches to 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF): a stable bio-based diol

- Conference papers

- Virtual Conference on Chemistry and its Applications VCCA-2020

- Comparison of P- and As-core-modified porphyrins with the parental porphyrin: a computational study

- Data curation to improve the pattern recognition performance of B-cell epitope prediction by support vector machine

- Molecular insights of metal–metal interactions in transition metal complexes using computational methods

- Structure, electronic and optical properties of chalcopyrite-type nano-clusters XFeY2 (X=Cu, Ag, Au; Y=S, Se, Te): a density functional theory study

- An efficient nanofiltration system containing mixture of rice husk ash and Fe/CeO2–SiO2 nanocomposite for the removal of azo dye and pesticide

- Synthesis and comparative study on the antibacterial activity organotin(IV) 3-hydroxybenzoate compounds

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Interpretation and use of standard atomic weights (IUPAC Technical Report)