Abstract

Transition-metal-catalyzed C–H functionalizations have emerged as complementary and powerful tools to access molecular complexity from widely available starting materials. Herein, we present a strategy for asymmetric intramolecular Pd(0)-catalyzed C–H functionalizations. The outlined reactivity is based on the cooperative effect between a chiral phosphorous ligand and a carboxylate base acting as a relay of chirality during the enantio-discriminating concerted metalation deprotonation step. This approach allows the enantioselective construction of a range of important semi-saturated chiral nitrogen-containing heterocycles such as indolines, tetrahydroquinolines, and dibenzazepinones.

Introduction

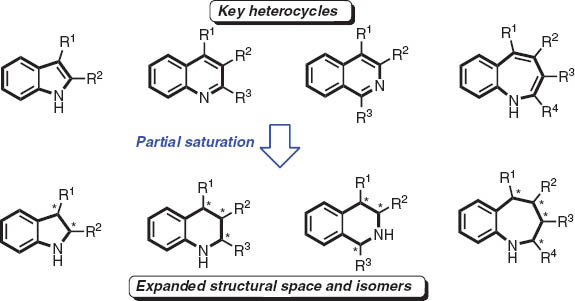

Heterocycles are privileged structures in organic synthesis. In particular, nitrogen-containing heterocycles are ubiquitous in natural products and extensively used in drug discovery, crop science, organic materials, and dyes [1].For simple and large heterocycle families like indoles, quinolines, isoquinolines, and benzazepines, numerous syntheses are reported. Their partially saturated analogs – indolines, tetrahydroquinolines, tetrahydroisoquinolines, and tetrahydrobenzazepines – are as well important building blocks covering a broad structural space. Moreover, the enhanced number of sp3-hybridized carbon atoms can have additional benefits (Fig. 1) [2]. However, the semi-saturated congeners which often contain stereogenic centers are more challenging to synthesize selectively, and, therefore, complementary and efficient routes are highly valuable.

Semi-saturation expands structural space of common nitrogen-containing heterocycles.

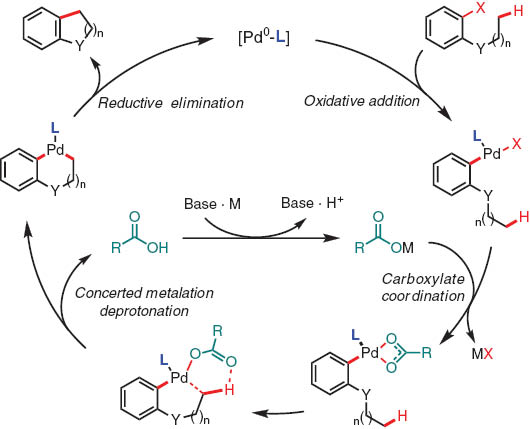

Over the past decade, the direct functionalization of unactivated C–H bonds gained significant importance because of its potential to streamline the synthesis of molecules by a rapid increase in molecular complexity [3]. The refined understanding of the concerted metalation–deprotonation (CMD) mechanism [4] was critical for the large extension of the scope of Pd(0)-catalyzed C–H functionalizations, leading to direct arylations of C(sp3)–H bonds [3b, 5] as well as to the development of intermolecular processes [6]. A carboxylate ligand bound to the transition metal is an integral part of the catalyst system. Moreover, this additive allows for milder reaction conditions and enhanced functional group tolerance. In the current mechanistic picture of Pd(0)-catalyzed C–H functionalizations following the CMD mechanism, the reaction is initiated by an oxidative addition (Scheme 1). Subsequently, the counterion is exchanged by the carboxylate co-catalyst, setting the stage for the CMD step. A three-coordinated Pd species renders the C–H bond more acidic through agostic interaction, and the carboxylate acts as an internal base deprotonating the C–H bond via a six-membered transition state. In turn, the carboxylic acid dissociates and is deprotonated by an external insoluble base. Reductive elimination of the cyclometalated Pd(II)-species releases the product and regenerates the Pd(0) catalyst.

Catalytic cycle for Pd(0)-catalyzed C–H functionalization with aryl halides.

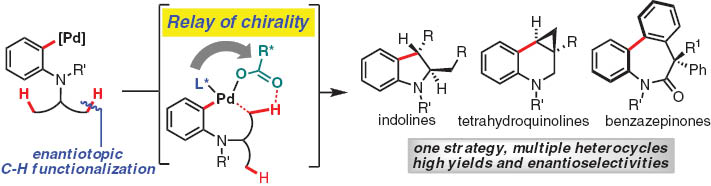

Asymmetric catalysis is an efficient way to access chiral molecules and its implementation towards the synthesis of nitrogen-containing heterocycles is a well exploited strategy [7]. However, only limited enantioselective C–H functionalizations have been reported so far [8],often because the harsh conditions required for such reaction interfere with selectivity. For Pd(0)-catalyzed C–H functionalizations calling for monodentate ligands, the reduced availability of efficient chiral monodentate phosphine families compared to the ubiquitous bidentate ligands represents also a limitation. Moreover, the single point coordination of the ligand on the metal results in free rotation across the metal-ligand bond rendering the imprint of chirality to the substrate more difficult compared to rigid bidentate counterparts. For asymmetric reaction of substrates possessing two enantiotopic C–H bonds, the CMD step is the enantio-discriminating event of the overall reaction. During this step, the chiral ligand of the Pd complex is remote from the C–H bond to be activated. This makes a good chiral transfer from the ligand to the substrate challenging. However, the carboxylate base, which is directly involved in the deprotonation event, is both close to the phosphine ligand and the substrate and therefore likely to be well suited to relay the chirality (Scheme 2). A key aspect of our approach was to evaluate and exploit this cooperative effect between the two different ligand types for enantioselective processes in Pd(0)-catalyzed C–H functionalizations.

Ligand and carboxylate cooperative effects enable high enantioselectivities in Pd(0)-catalyzed C–H functionalizations.

Results and discussion

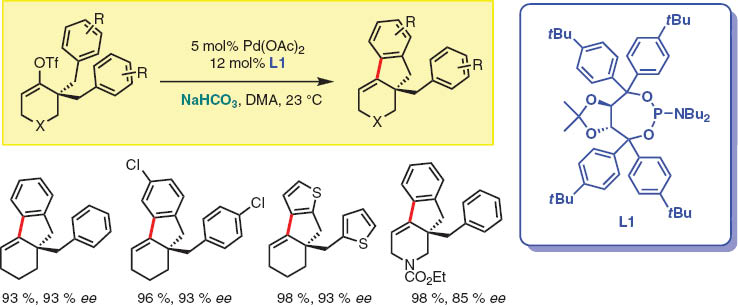

Palladium(0)-catalyzed enantioselective C–H alkenylation: An initial proof of principle

When we first became interested in enantioselective C–H functionalizations, enantioselective activation of C–H bonds was illusive with Pd(0)-catalyst systems [9].Several reports show that achiral transformations operating by the CMD-mechanism require phosphine or carbene ligands to proceed [4b]. These findingsprompted us to believe that the enantiocontrol of such transformation could be feasible by suitable ancillary phosphine ligands. We selected a simple model having an alkenyl triflate and two enantiotopic phenyl groups to establish the initial proof of principle of our hypothesis [10]. This substrate class would be able to undergo enantioselective arylation of aromatic C(sp2)–H bonds via a favored six-membered palladacycle. The use of a triflate in contrast to a halide bears the benefits of a faster exchange step of the counterion for the carboxylate. After an exhaustive screen of a large variety of different phosphorous-based ligands, taddol-based phosphoramidite ligands crystallized as the most promising family. However, the reaction turned out to be very sensitive to the substitution pattern of the taddol ligand and tailored ligand L1 provided the desired high enantioselectivities of >90% ee. The reaction conditions are extraordinarily mild, proceeding at ambient temperature under virtually neutral conditions with sodium bicarbonate as base. Indanes having an all-carbon quaternary center were formed in excellent enantioselectivities, proving the general feasibility of our envisioned enantioselective C–H activation concept (Scheme 3).

Initial Pd(0)-catalyzed enantioselective C–H alkenylation.

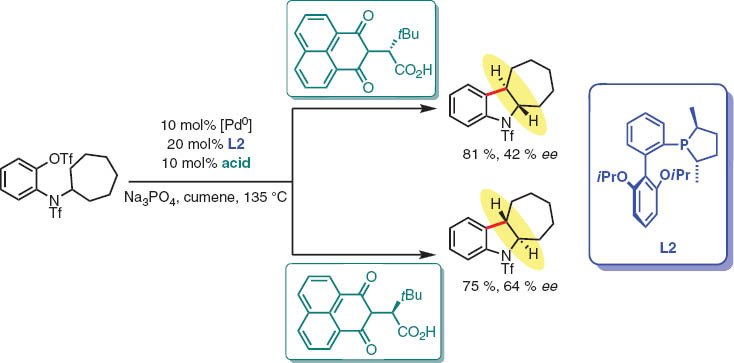

C(sp3)–H arylations: Synthesis of functionalized indolines

In contrast to aromatic C(sp2)–H bonds, alkyl C(sp3)–H bonds are less acidic and no π electrons are available for catalyst pre-coordination making C(sp3)–H functionalization a significantly more challenging task. Fagnou and co-workers reported the synthesis of dihydrobenzofurans via Pd-catalyzed arylation of C(sp3)–H bonds showing the importance of catalytic amounts of pivalic acid as a key additive for the CMD step [5a].Subsequently, Ohno and co-workers demonstrated the synthesis of indolines with the same set of conditions [11]. Given the synthetic importance and value of indolines, we aimed to develop an asymmetric variant of this reaction. During the course of our studies, Kündig et al. [12] and Kagan et al. [13] independently developed enantioselective methods for this transformation. Kündig uses his bulky chiral carbene ligands [14] in combination with the standard pivalic acid additive to achieve high enantioselectivities. To investigate our hypothesis of relaying the chirality to the carboxylic acid, we explored the different combination of chiral carboxylic acids and phosphine ligands and found a strong matched/mismatched effect (Scheme 4).

Strong cooperative effects with chiral carboxylic acids.

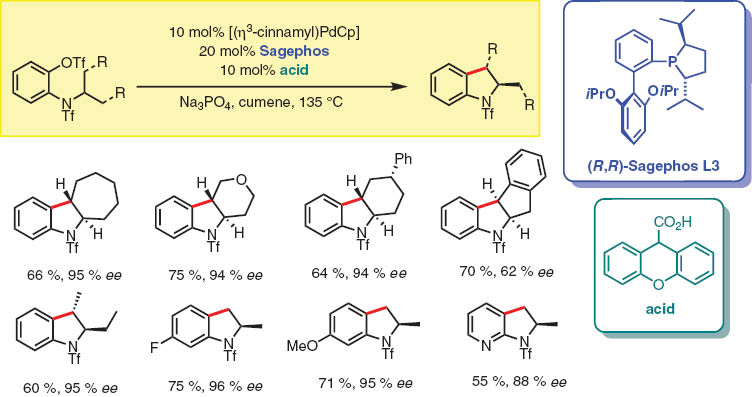

The need for a bulky electron-rich ligand for this transformation combined with the lack of chiral monodentate phosphines forced us to develop a family of bulky chiral biaryl monophospholanes. Among them, Sagephos L3 turned out to be highly selective for the enantioselective functionalization of methyl as well as methylene C–H bonds starting from aryl triflates. As optimal carboxylic acid partner for L3, our screening revealed the bulky 9H-xanthene-9-carboxylic acid providing robust and high selectivities [15].The reaction has a broad substrate scope and allows for the simultaneous construction of up to three stereocenters (Scheme 5).

Synthesis of indolines via enantioselective C(sp3)–H arylation.

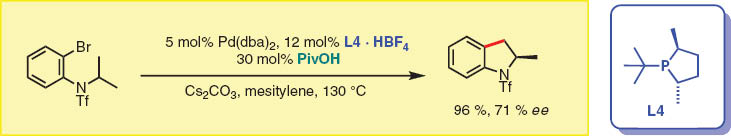

Similar aryl bromide substrates react sluggishly with L3. However, ligand L4 based on the C2-symmetric phospholane architecture mimics the profile of PCy3 and PtBu3 and displays with aryl bromides excellent reactivity and promising selectivity (Scheme 6) [16].

Pd(0)-catalyzed enantioselective arylation starting from aryl bromides

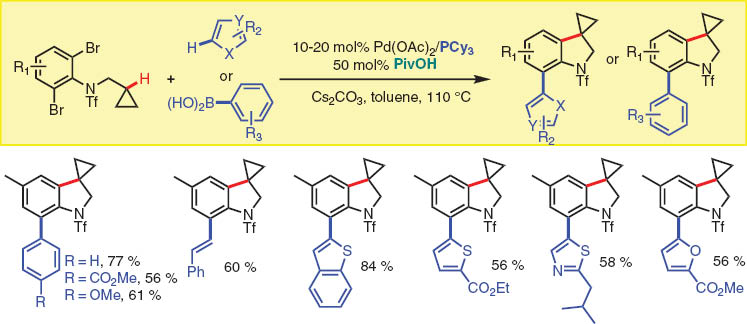

During the development of enantioselective cyclopropane C–H arylations (vide infra), we discovered that substrates possessing cyclopropane substituents with a methine C–H underwent exclusive methine C–H bond activation rather than methylene C–H bond activation leading to larger palladacycle.No destruction of the cyclopropane ring occurs, and the method affords spiroindolines in high yields. Moreover, this reaction can be conducted as a tandem process coupled with intermolecular Suzuki couplings or direct arylation of heteroaromaticsto access more complex spiroindolines in a single operation (Scheme 7) [17].

Synthesis of spiroindolines via Pd-catalyzed methine C–H arylation.

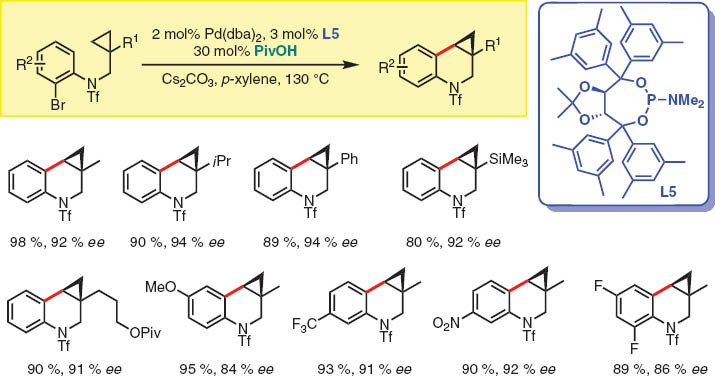

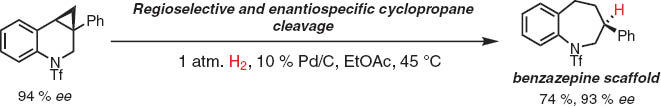

Enantioselective C–H arylation of cyclopropanes

Next, we aimed to extend the scope of the arylation methodology to larger rings such as tetrahydroquinolines. This would require less favorable seven-membered palladacycle intermediates, which were elusive for C(sp3)–H arylations. We concentrate our efforts on cyclopropane C–H functionalizations that would be a complementary route to the many cyclopropane construction methods [18].Such a reaction would not only deliver synthetically valuable products,but as well facilitate the activation process due to the higher s-character of the cyclopropane C–H bonds rendering them more acidic [19] and susceptible towards activation. A re-optimization of the previously successful reaction conditions was necessary, and taddol-based phosphoramidite L5 gave the best selectivities. Again, the carboxylic acid was crucial as co-catalyst for both reactivity and selectivity, and simple pivalic acid was among the most efficient for this purpose. This new catalytic system is well tolerant towards functional groups and enables the enantioselective synthesis of functionalized tetrahydroquinolines possessing a cyclopropane ring with a quaternary stereocenter (Scheme 8) [20].

Intramolecular enantioselective direct arylation of cyclopropanes.

Submitting the tetrahydroquinoline product to mild heterogeneous reduction conditions with H2 and Pd/C, a regioselective hydrogenation of the inner bis-benzylic C–C bond of the cyclopropane moiety took place (Scheme 9). Intriguingly, this reduction is completely enantiospecific and afforded the benzazepine scaffold in good yields.

Access to benzazepines via enantiospecific cyclopropane reduction.

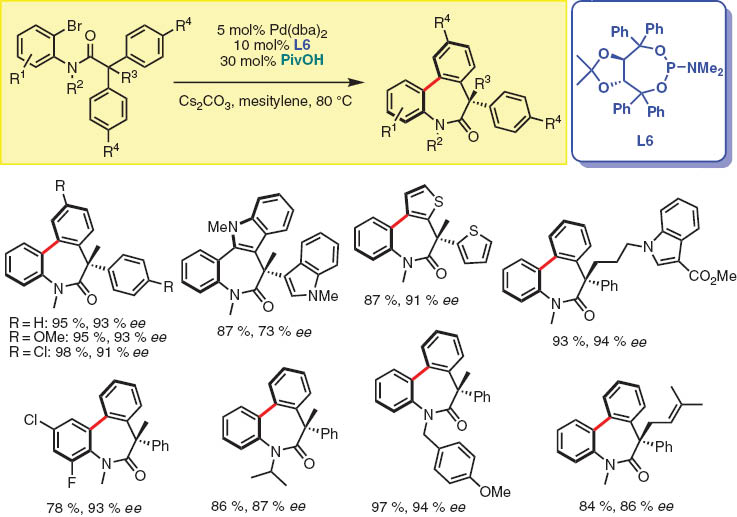

Eight-membered palladacycle intermediates leading to chiral benzazepinones

While with the illustrated regioselective and enantiospecific opening of cyclopropane-substituted tetrahydroquinolines chiral benzazepines could be obtained indirectly, a direct access to this scaffold was more desirable. Intramolecular C–H arylations are by and large limited to the synthesis of four-, five-, and six-membered rings. In contrast, scarce examples of seven-membered ring formations are reported which all require high catalyst loadings (10 mol%) and/or harsh reaction temperatures (>130 °C) [21]. This gap can be attributed to the more difficult formation of the eight-membered palladacycle intermediates. To address this issue, we focused on aromatic C(sp2)–H bonds embedded in a substrate with a rigid amide tether [22].We expected that this would conformationally predispose the aromatic groups towards the aryl Pd(II) species resulting in a facilitated metalation. The anticipated concept worked successfully delivering highly substituted benzazepinones at reaction temperatures as low as 80 °C (Scheme 10). The archetypical and simplest congener of the taddol-phosphoramidite family L6 [23] proved to be together with pivalic acid as co-catalyst the most efficient ligand for this transformation. The process is highly regioselective and functional group tolerant, affording complex chiral benzazepinones in high enantioselectivities.

Synthesis of benzazepinones with quaternary stereocenters by Pd-catalyzed C–H arylation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we presented an enantioselective intramolecular C–H arylation strategy to efficiently access functionalized heterocycles. The method is based on chiral phosphine and phosphoramidite ligands working in cooperation with a matching carboxylate, which is required to assist the concerted metalation deprotonation step. A broad spectrum of C–H bonds can be successfully addressed ranging from aromatic C(sp2)–H bonds to methyl, methylene, and methine C(sp3)–H bonds. Furthermore, the size of the palladacyclic intermediate can be varied from six-, seven-, and eight-membered palladacycles, allowing access of some of the most important semi-saturated chiral nitrogen-containing heterocycles in an enantioselective fashion.

References

[1] (a) A. F. Pozharskii, A. R. Katritsky, A. T. Soldatenkov (Eds.). Heterocycles in Life and Society: An Introduction to Heterocyclic Chemistry and Biochemistry and the Role of Heterocycles in Science Technology, Medicine and Agriculture, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim (1997); (b) T. Eicher, S. Hauptmann (Eds.). The Chemistry of Heterocycles: Structure, Reactions, Syntheses, and Applications, 2nd ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim (2003); (c) L. D. Quin, J. Tyrell (Eds.). Fundamentals of Heterocyclic Chemistry: Importance in Nature and in the Synthesis of Pharmaceuticals, John Wiley, Hoboken, NJ (2010).Search in Google Scholar

[2] F. Lovering, J. Bikker, C. Humblet. J. Med. Chem. 52, 6752 (2009).Search in Google Scholar

[3] (a) X. Chen, K. M. Engle, D. H. Wang, J. Q. Yu. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 5094 (2009); (b) R. Jazzar, J. Hitce, A. Renaudat, J. Sofack-Kreutzer, O. Baudoin. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 2654 (2010); (c) T. W. Lyons, M. S. Sanford. Chem. Rev. 110, 1147 (2010); (d) D. A. Colby, R. G. Bergman, J. A. Ellman. Chem. Rev. 110, 624 (2010); (e) J. Yamaguchi, A. D. Yamaguchi, K. Itami. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 8960 (2012); (f) N. Kuhl, M. N. Hopkinson, J. Wencel-Delord, F. Glorius. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 10236 (2012); (g) J. J. Mousseau, A. B. Charette. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 412 (2013).Search in Google Scholar

[4] (a) D. Garcia-Cuadrado, P. de Mendoza, A. A. C. Braga, F. Maseras, A. M. Echavarren. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 6880 (2007); (b) D. Lapointe, K. Fagnou. Chem. Lett. 39, 1118 (2010); (c) L. Ackermann. Chem. Rev. 111, 1315 (2011).Search in Google Scholar

[5] (a) M. Lafrance, S. I. Gorelsky, K. Fagnou. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 14570 (2007); (b) M. Chaumontet, R. Piccardi, N. Audic, J. Hitce, J.-L. Peglion, E. Clot, O. Baudoin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15157 (2008); (c) S. Rousseaux, S. I. Gorelsky, B. K. W. Chung, K. Fagnou. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10706 (2010); (d) S. Rousseaux, B. Liegault, K. Fagnou. Chem. Sci. 3, 244 (2012).Search in Google Scholar

[6] (a) M. Lafrance, K. Fagnou. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 16496 (2006); (b) M. Livendahl, A. M. Echavarren. Isr. J. Chem. 50, 630 (2010).Search in Google Scholar

[7] For selected recent examples, see: (a) A. B. Dounay, L. E. Overman, A. D. Wrobleski. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 10186 (2005); (b) A. T. Parsons, A. G. Smith, A. J. Neel, J. S. Johnson. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 9688 (2010); (c) S. B. Jones, B. Simmons, A. Mastracchio, D. W. C. MacMillan. Nature 475, 183 (2011); (d) R. H. Snell, R. L. Woodward, M. C. Willis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 9116 (2011); (e) D. Katayev, Y.-X. Jia, D. Banerjee, C. Besnard, E. P. Kundig. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 11916 (2013); (f) N. Ortega, D.-T. D. Tang, S. Urban, D. Zhao, F. Glorius. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 9500 (2013); (g) M. Amatore, D. Leboeuf, M. Malacria, V. Gandon, C. Aubert. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 4576 (2013).Search in Google Scholar

[8] For a review on enantioselective C–H activation, see: (a) R. Giri, B.-F. Shi, K. M. Engle, N. Maugel, J.-Q. Yu. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 3242 (2009); for enantioselective Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalizations, see: (b) B.-F. Shi, N. Maugel, Y.-H. Zhang, J.-Q. Yu. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4882 (2008); (c) B.-F. Shi, Y.-H. Zhang, J. K. Lam, D.-H. Wang, J.-Q. Yu. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 460 (2009); (d) M. Wasa, K. M. Engle, D. W. Lin, E. J. Yoo, J.-Q. Yu. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19598 (2011); (e) N. Martin, C. Pierre, M. Davi, R. Jazzar, O. Baudoin. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 4480 (2012); (f) R. Shintani, H. Otomo, K. Ota, T. Hayashi. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7305 (2012); (g) D.-W. Gao, Y.-C. Shi, Q. Gu, Z.-L. Zhao, S.-L. You. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 86 (2013); (h) C. Pi, Y. Li, X. Cui, H. Zhang, Y. Han, Y. Wu. Chem. Sci. 4, 2675 (2013); (i) X.-F. Cheng, Y. Li, Y.-M. Su, F. Yin, J.-Y. Wang, J. Sheng, H. U. Vora, X.-S. Wang, J.-Q. Yu. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1236 (2013); for selected examples of enantioselective C–H functionalization from our group, see: (j) D. N. Tran, N. Cramer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 11098 (2011); (k) B. Ye, N. Cramer. Science 338, 504 (2012); (l) P. A. Donets, N. Cramer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11772 (2013).Search in Google Scholar

[9] Only one enantioselective Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalization was reported at this time: see ref. [8b].Search in Google Scholar

[10] M. Albicker, N. Cramer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 9139 (2009).Search in Google Scholar

[11] T. Watanabe, S. Oishi, N. Fujii, H. Ohno. Org. Lett. 10, 1759 (2008).Search in Google Scholar

[12] M. Nakanishi, D. Katayev, C. Besnard, E. P. Kundig. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7438 (2011).Search in Google Scholar

[13] S. Anas, A. Cordi, H. B. Kagan. Chem. Commun. 47, 11483 (2011).Search in Google Scholar

[14] (a) E. P. Kundig, Y. Jia, D. Katayev, M. Nakanishi. Pure Appl. Chem. 84, 1741 (2012); (b) D. Katayev, M. Nakanishi, T. Burgi, E. P. Kundig. Chem. Sci. 3, 1422 (2012); (c) E. Larionov, M. Nakanishi, D. Katayev, C. Besnard, E. P. Kundig. Chem. Sci. 4, 1995 (2013).Search in Google Scholar

[15] T. Saget, S. J. Lemouzy, N. Cramer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 2238 (2012).Search in Google Scholar

[16] P. A. Donets, T. Saget, N. Cramer. Organometallics 31, 8040 (2012).10.1021/om3008772Search in Google Scholar

[17] T. Saget, D. Perez, N. Cramer. Org. Lett. 15, 1354 (2013).Search in Google Scholar

[18] H. Lebel, J.-F. Marcoux, C. Molinaro, A. B. Charette. Chem. Rev. 103, 977 (2003).Search in Google Scholar

[19] A. de Meijere. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 18, 809 (1979).10.1002/anie.197908093Search in Google Scholar

[20] T. Saget, N. Cramer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 13014 (2012).Search in Google Scholar

[21] (a) M. Burwood, B. Davies, I. Diaz, R. Grigg, P. Molina, V. Sridharan, M. Hughes. Tetrahedron Lett. 36, 9053 (1995); (b) T. Harayama, H. Akamatsu, K. Okamura, T. Miyagoe, T. Akiyama, H. Abe, Y. Takeuchi. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 523 (2001); (c) L. C. Campeau, M. Parisien, M. Leblanc, K. Fagnou. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 9186 (2004); (d) M. Leblanc, K. Fagnou. Org. Lett. 7, 2849 (2005); (e) L. C. Campeau, M. Parisien, A. Jean, K. Fagnou. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 581 (2006); (f) C. Huang, V. Gevorgyan. Org. Lett. 12, 2442 (2010); (g) D. G. Pintori, M. F. Greaney. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 1209 (2011); (h) C. B. Bheeter, J. K. Bera, H. Doucet. Adv. Synth. Catal. 354, 3533 (2012).Search in Google Scholar

[22] T. Saget, N. Cramer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 7865 (2013).Search in Google Scholar

[23] H. W. Lam. Synthesis 43, 2011 (2011).10.1055/s-0030-1260022Search in Google Scholar

Article note

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 17th International IUPAC Conference on Organometallic Chemistry Directed Towards Organic Synthesis (OMCOS-17), Fort Collins, Colorado, USA, 28 July–1 August 2013.

©2014 by IUPAC & De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Conference papers

- International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

- Enantioselective palladium(0)-catalyzed C–H arylation strategy for chiral heterocycles

- Organometallic catalysis for applications in radical chemistry and asymmetric synthesis

- Rhenium(I)-catalyzed reaction of terminal alkynes with imines leading to allylamine derivatives

- Copper-catalyzed aminoboration and hydroamination of alkenes with electrophilic amination reagents

- Activation of stable σ-bonds for organic synthesis

- Pd-catalyzed reactions of unactivated Csp3−I bonds

- Pd- and Ni-catalyzed C–H arylations using C–O electrophiles

- Nickel-catalyzed oxidative cross-coupling of arylboronic acids with olefins

- Stereoselective C-glycosylation of furanosyl halides with arylzinc reagents

- Transition-metal clusters as catalysts for chemoselective transesterification of alcohols in the presence of amines

- Cu(I)/Cu(III) catalytic cycle involved in Ullmann-type cross-coupling reactions

- Beyond C–H and C–O activation: the evolution of components in cross-coupling reactions

- The effect of acceptor-substituted alkynes in gold-catalyzed intermolecular reactions

- Chemoselective silver-catalyzed nitrene insertion reactions

- The strategic generation and interception of palladium-hydrides for use in alkene functionalization reactions

- 3-Acyloxy-1,4-enyne: A new five-carbon synthon for rhodium-catalyzed [5 + 2] cycloadditions

- Cobalt-catalyzed directed alkylation of arenes with primary and secondary alkyl halides

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Assessment of international reference materials for isotope-ratio analysis (IUPAC Technical Report)

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Conference papers

- International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

- Enantioselective palladium(0)-catalyzed C–H arylation strategy for chiral heterocycles

- Organometallic catalysis for applications in radical chemistry and asymmetric synthesis

- Rhenium(I)-catalyzed reaction of terminal alkynes with imines leading to allylamine derivatives

- Copper-catalyzed aminoboration and hydroamination of alkenes with electrophilic amination reagents

- Activation of stable σ-bonds for organic synthesis

- Pd-catalyzed reactions of unactivated Csp3−I bonds

- Pd- and Ni-catalyzed C–H arylations using C–O electrophiles

- Nickel-catalyzed oxidative cross-coupling of arylboronic acids with olefins

- Stereoselective C-glycosylation of furanosyl halides with arylzinc reagents

- Transition-metal clusters as catalysts for chemoselective transesterification of alcohols in the presence of amines

- Cu(I)/Cu(III) catalytic cycle involved in Ullmann-type cross-coupling reactions

- Beyond C–H and C–O activation: the evolution of components in cross-coupling reactions

- The effect of acceptor-substituted alkynes in gold-catalyzed intermolecular reactions

- Chemoselective silver-catalyzed nitrene insertion reactions

- The strategic generation and interception of palladium-hydrides for use in alkene functionalization reactions

- 3-Acyloxy-1,4-enyne: A new five-carbon synthon for rhodium-catalyzed [5 + 2] cycloadditions

- Cobalt-catalyzed directed alkylation of arenes with primary and secondary alkyl halides

- IUPAC Technical Report

- Assessment of international reference materials for isotope-ratio analysis (IUPAC Technical Report)