Abstract

Providing access to knowledge and information for all citizens, including the disadvantaged ones, is a constant preoccupation of the decision-making bodies of countries across the globe, particularly of developed and developing ones. In Europe, guidelines for creating accessible informational content have been created, being constantly improved and adapted to the new social realities. As a member state of the European Union, Romania also fosters social inclusion at various levels, including that of making information accessible to all people. Nevertheless, a lot still needs to be done in the field of linguistic accessibility as the analysis presented in the article shows. For example, research should be conducted to draft guidelines for using accessible languages. Then, the study of accessible languages should be implemented in “Translation and interpreting” study programmes for the purpose of developing skills that could be employed socially to increase knowledge accessibility, through interlingual and intralingual translation and interpreting services. In this way, awareness is raised in society and professionals specialised in linguistic accessibility are provided to the labour market to contribute, as language professionals, to the creation of an inclusive society.

1 Introduction

In the previous century, the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights marked the moment when awareness of the imperative necessity to treat each and every one equally was raised. Since then, a number of documents have been issued by the United Nations, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to draw the attention to the need of being respectful and kind towards any human being, in other words to place human dignity and access to material and immaterial goods at the centre of our actions and those of the governments, respectively. However, these documents go beyond raising awareness, they urge decision-making bodies to take action, to be pro-active and change the society in which we live, to turn it into an accessible place that comfortably accommodates us all, irrespective of ethnic origin or nationality, gender or profession, health status or age, social or financial condition, migrant or immigrant status, to mention but a few (Dejica et al. 2022, Dejica et al. 2022, Maaß 2020). To achieve this goal, the Information and Communications Technologies have contributed greatly since they have reshaped the entire society, they have developed new communication methods and changed the way in which we perceive reality or interact with it (Floridi 2015, Greco 2018, Stephanidis 2009), extremely important being the access people have gained, through these new technologies, to all types of information.

Originating in the human rights movement and being intensified by the Information and Communications Technologies, accessibility has developed into a field of its own, built on interdisciplinary research in various fields: engineering, architecture, geography, cultural heritage, translation, education, computing, tourism and transportation, to mention but a few. The knowledge gathered from this interdisciplinary approach has been put at the service of the community, offering accessible solutions to overcome various barriers, for example cognitive, sensory, physical, linguistic, social and cultural ones (Baños 2017, Bernabé Caro 2020, Bernabé Caro and Orero 2019, Buhalis and Darcy 2011, Dejica et al. 2022, Dejica et al. 2022, Janelle and Hodge 2000, Litman 2017, Maaß 2020, Orero 2004, 2012, Orero and Matamala 2007, Prodan 2017, Pullin 2009, Sanchez and Brenman 2007, Stephanidis and Emiliani 1999).

In Europe, a lot has been done lately to build an inclusive society, one of the preoccupations being to offer all of us access to information and knowledge, thus creating a framework within which all citizens can reach their full potential. For instance, directives have been adopted by the European Union that regulate the provision of accessible websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies, accessible audiovisual media services as well as accessible products and services (Directive (EU) 2016/2102, Directive (EU) 2018/1808 and Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and of the Council). Since Romania is a member state of the European Union, it also embraces the European cause, striving to create a society in which language use is no longer a communication barrier.

The article aims at highlighting some of the most important actions taken in the field of linguistic accessibility at a European level, focusing on the emergence of accessible languages used to translate and interpret both interlingually and intralingually, with the purpose of showing the stage Romania has reached so far. Thus, in order to offer an overview of the linguistic accessibility in Romania, the following aspects have been researched: linguistic accessibility for people with disabilities/impairments provided by the education system, public institutions and broadcasting companies, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the bachelor’s and master’s degrees in translation and interpreting studies functioning in Romania that form specialists in linguistic accessibility, including specialists in accessible languages.

2 Overcoming communication barriers through accessible languages

Building an inclusive society means, among others, creating appropriate solutions to overcome communication barriers caused by low “perceptibility, comprehensibility, retrievability and acceptability of texts and information” (Maaß 2020, 20). In other words, communication should be tailored to the needs of the target group they address, so that the code is perceptible and comprehensible, the channel is accessible, and the final communication product is considered acceptable both by the end-users and by the rest of the community, without stigmatising the former ones (Maaß 2020). To identify the target group’s needs, eight communication barriers have been singled out, namely sensory, cognitive, motor, language, expert knowledge and/or language, cultural, media and motivational barriers (Lang 2021, Rink 2019, 2020).

Messages may be communicated visually, orally or haptically. When one of these senses is essential to understanding the informational content, but it is not available to the receiver, then we speak of a sensory barrier. It is the case, for example, of blind persons that are not able to read messages that are written in an alphabet other than Braille for which they employ their tactile sense, or of deaf persons that are not able to listen to a spoken discourse and have to use other senses to communicate efficiently. When the informational content is too complicated for the receiver to understand it, then we speak of a cognitive barrier. People with temporary or permanent motor disabilities might also face challenges when they need to access information that implies body movements, for instance when they need to use their hands to use the computer or telephone. In this case, people need to overcome a motor barrier. Language barriers appear when the communication partners do not share the same language. Expert knowledge and/or language barriers are those erected using field-specific terminology in the communication among persons that do not have the same specialised knowledge. Such a situation might be experienced by a large number of people, including people with no disability at all. Additionally, when two or more cultures get in contact, linguistic, discoursal and behavioural differences that are not understood or accepted by one of the parties might emerge. Accessing media content might be difficult for senior citizens, for people with cognitive, sensory or motor disabilities, which means they encounter media barriers. Finally, we speak of motivational barriers when the users have had bad experiences with the discourse genre they have to understand and/or work with, and consequently tend to reject it.

Considering the aforementioned communication barriers, the people that need customised access to information are as follows: (a) people that are fully developed cognitively, but have some kind of motor or sensory disability, such as motor, hearing or visual impairment; (b) people with cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer’s disease or another type of dementia; (c) people with intellectual disabilities; (d) people with learning, reading, writing and spelling difficulties, such as dyslexia; (e) people with limited language skills, such as immigrants and non-native speakers of a language; (f) people that are fully developed cognitively, but have to deal with a highly specialised discourse, such as the legal, medical or technical one; and (g) people with low literacy levels, or even functionally illiterate ones (International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions – IFLA 2010, Garcia et al. 2010, Murman 2015, Train2Validate 2020, Yaneva 2015). Therefore, in order to foster social inclusion, accessible informational content is needed, in a large variety of situations, for people with or without disabilities or impairments. Some of the solutions found to provide it are often interdisciplinary, namely they are created in the field of translation and interpreting studies and of linguistic and cultural mediation, but also resort to the new technologies to make them available to the target group. Since translation may be intralingual, i.e. rewording or paraphrase within the same language; interlingual, i.e. conveying meaning from one language into another; and intersemiotic, i.e. using non-verbal signs to convey the meaning of the verbal ones (Jakobson 1959), the creation of accessible informational content is also considered a type of translation (Bredel and Maaß 2016a, 2016b, Maaß 2019, Maaß and Rink 2020). Sometimes, however, for accessibility reasons, the translator makes use of enhancing strategies, such as adding “verbal or nonverbal semantic material as a simplification strategy” (Bernabé Caro 2020, 356). In other words, to make the information accessible for persons that are visually, aurally and/or cognitively challenged, the translator needs to employ a large range of simplification strategies that might be “both reductive and additive” (Bernabé Caro 2020, 350). The additions may be not only verbal, but also visual, such as pictograms, drawings and the like, hence the translation from standard language into accessible language varieties may also be intersemiotic, not just interlingual or intralingual (Maaß 2020).

Aiming at turning written and spoken discourses into accessible communication tools for us all, these accessible language varieties, also termed easy languages (Lindholm and Vanhatalo 2021), e.g. plain language, easy language and easy language plus, have emerged as deviations from the standard ones, the latter being defined as institutionalised and prestige language varieties widely understood by a community (Crystal 2005). Since the term easy languages refers to easy to read and understand (UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities), a written variety also termed easy-to-read (Inclusion Europe 2009, International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions – IFLA 1997, 2010), as well as, more recently, to their spoken equivalents (Maaß 2020), the term easy language gains “broader conceptualisations of enhancing comprehensibility through language” (Maaß 2020, 56), be it written or spoken, but does not also include plain language. Therefore, we propose the term accessible languages because it is less confusing and most appropriate to describe all the existing or future language varieties, be they written or spoken, that aim at supporting people with various disabilities or impairments to communicate successfully in the inclusive society we want to build.

The accessible languages introduced above have been developed to create and offer accessible informational content. Although they have a common purpose, they address different end-users and follow different guidelines (Cutts 2013, Inclusion Europe n.d., International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions – IFLA 1997, 2010, Lindholm and Vanhatalo 2021, Maaß 2020, Plain Language Action and Information Network – PLAIN n.d.). Thus, plain language does not necessarily address people with disabilities, but rather those with communication impairments of various origins or lay people without an expert-field background. The plain language texts should consider the average reading age of the population, which in the case of UK is about 13 (Cutts 2013, xiii), since its main aim is to translate expert language into lay language, i.e. a simpler language that anyone can understand. Moreover, people tend to fully accept plain language because it “is seen in the context of removing red tape from communication and making it comprehensible to non-expert everyday people” (Maaß 2020, 139). From this perspective, easy language is often rejected by the society as it deviates too much from the standard language, which could “possibly lead to resentments against the target groups, who are in danger of being stigmatised through Easy Language texts” (Maaß 2020, 68). Translating a text from standard language into easy language means employing “strong reductions in structural complexity on the one hand, but … also extensive elaborations on the other hand. As a consequence, there is a relatively big amount of text conveying a relatively small amount of information on the subject” (Maaß 2020, 91). Additionally, visual support might be used to better convey the message in easy language. To sum up, plain language is “a linguistic variety with enhanced comprehensibility” (Maaß 2020, 53), while easy language is a “linguistic variety with maximally enhanced comprehensibility” (Maaß 2020, 53).

Considering the acceptability of the two language varieties among the population and the stigmatisation of the end-users in society, Christiane Maaß (2020) proposed easy language plus, in an effort to make the community embrace this accessible language as a solution for those who need it in order to be as autonomous as possible. Easy language plus is in fact a combination between plain language and easy language, which does not use the least accepted features of easy language, thus becoming “somewhat less comprehensible and perceptible (as the texts are closer to the standard), but much more acceptable” (Maaß 2020, 280).

3 Using accessible languages to extend the scope of translation and interpreting services

Translation and interpreting have been traditionally defined as conveying meaning and understanding from one language into another, in writing and speaking, respectively, considering the linguistic and the cultural conventions both of the source language and of the target one (Dejica and Dejica-Carțiș 2020, Nolan 2005, Pöchhacker 2016, Șimon 2017, Şimon and Stoian 2017). In time, translation and interpreting types have diversified to meet the needs of the ever-evolving society. Nowadays, in many countries across the globe, the inclusive society is being built striving to remove all the sensory, cognitive, motor, language, expert knowledge and/or language, cultural, media and motivational barriers (Lang 2021, Rink 2019, 2020) described above, by interlingual and intralingual translation and interpreting, among others (Arias-Badia and Matamala 2020, Bernabé Caro 2020, Bernabé Caro and Orero 2019, Dejica and Dejica-Carțiș 2020, Lindholm and Vanhatalo 2021, Maaß 2020, Pöchhacker 2016, Şimon and Stoian 2017, Witzel 2019). As such, spoken-language interpreting, sign language interpreting, interlingual subtitling, subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing (SDH), audio description for people with visual impairments, speech-to-text interpreting, film interpreting, opera or theatre supertitles/surtitles, respeaking, voiceover, dubbing, sight translation or sight interpreting, as Pöchhacker (2016) calls it, localisation, interpreting in a variety of contexts (business, media, community, conference interpreting) or transcoding text to Braille or the other way around are only some of the translation and interpreting types that have emerged lately, particularly in the field of Audiovisual Translation, broadly defined as “all forms of translation and interpreting between different modalities involving tertiary media of any type” (Maaß and Hernández Garrido 2020, 131).

Although the aforementioned translation and interpreting types, except for sign interpreting and Braille translation, on the one hand and audio description on the other hand, have been developed to transfer meaning interlingually, lately they have started to be used also to convey meaning intralingually, resorting to accessible languages (Arias-Badia and Matamala 2020, Bernabé Caro 2020, Bernabé Caro and Orero 2019, Hansen-Schirra and Maaß 2020, Lindholm and Vanhatalo 2021, Maaß 2020). Furthermore, in recent years, easy language interpreting (Schulz et al. 2020) as well as speech-to-text interpreting with complexity reduction (Witzel 2019) has been successfully practised for accessibility purposes, opening up new avenues for research, for translators’ and interpreters’ professional activity and, implicitly, for social inclusion.

Since the end-users of discourses in accessible languages have increased needs as compared to other audiences, the translators and interpreters specialising in accessible languages should also have additional competences from the ones they need to render the meaning from and into standard languages. Taking into account the recommendations of the PACTE group as well as those of Pöchhacker (2016) and Schulz et al. (2020), Maaß (2020, 172) points to the competences that translators and interpreters specialising in easy languages, i.e. accessible languages, should acquire in order to fulfil their professional duties at the highest standards:

expert domain and expert language competence is a must in order to be able to translate or interpret accurately, while standard language translators and interpreters usually specialise in a domain, accessible language translators and interpreters do not, so they have to be quite proficient in the terminology of a large number of domains and seek expert support when they need it,

comprehensive knowledge of the accessible languages used and of the problems they might pose in the translation or interpreting process, so that the translator or interpreter makes competent and effective choices that do not endanger the accessibility process,

knowledge of the target audience is essential since it helps the translator or interpreter to better understand it and to make the best decisions when they translate or interpret intra- or interlingually into accessible languages,

competence to assess the target situation is also essential in adapting the translated or interpreted content to the needs of the target audience,

translation and text competence is connected to the other competences described above since, to translate or interpret professionally into accessible languages, besides knowledge of the accessible language rules and guidelines, one also needs to be able to assess the target situation and audience, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, to preserve the genre and media features, particularly difficult to develop are the accessible language interpreting skills and the emergency strategies the interpreter might need.

Although the competences identified by Christiane Maaß (2020, 172) are in fact derived from those needed by standard language translators and interpreters, the former are much more difficult to acquire than the latter. This is proven by the fact that once the demand for accessible language translators and interpreters on the labour market increased, and the challenges faced by them seemed unsurmountable without proper academic training, master’s degrees in accessible communication have been established in Europe, for instance in Spain, Portugal, Germany and Switzerland, offering courses in translation and interpreting from and into accessible languages (Eichmeyer 2018, Maaß 2020, Maaß and Hernández Garrido 2020, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Polytechnic of Leiria, University of Mainz/Germersheim, University of Hildesheim, University of Applied Sciences of Winterthur). Yet, this endeavour is timid and further research has to be carried out to develop a comprehensive educational framework within which translators and interpreters can acquire the necessary skills to foster interlingual and intralingual accessible communication at a high level of proficiency.

4 Increasing accessibility in Romania through interlingual and intralingual translation and interpreting

As a member state of the European Union, Romania has also adhered to the principles that lie at the foundation of the inclusive society, adopting national strategies aiming to increase accessibility, particularly of the people with disabilities (Guvernul României. Ministerul Muncii si Solidarității Sociale. Autoritatea Națională pentru Protejarea Drepturilor Persoanelor cu Dizabilități n.d.). Nevertheless, Romania is aware of the fact that it has a long way to go, from architectural to educational accessibility. So, raising awareness of the benefits of an inclusive society is one of the top issues, along with concrete accessibility measures that must be taken since Romania, in comparison with its European partners, offers little if any inclusive support to its citizens with a disability and/or an impairment (Guvernul României. Ministerul Muncii si Solidarității Sociale. Autoritatea Națională pentru Protejarea Drepturilor Persoanelor cu Dizabilități n.d., Fărcașiu et al. 2022, Grigoraș et al. 2021, Nicolae 2020).

In terms of linguistic accessibility, at the moment, printed or digital materials in accessible languages are scarce in Romania, no matter the age group they address or their communication purpose (Bolborici and Bódi 2018, Fărcașiu et al. 2022, Guvernul României. Ministerul Muncii si Solidarității Sociale. Autoritatea Națională pentru Protejarea Drepturilor Persoanelor cu Dizabilități n.d., Vrăşmaş 2014). However, although in Romania there are no easy-to-read periodicals, at the European level, the easy-to-read magazine and newsletter Europe for us is published, on the Inclusion Europe website, four times a year in several languages: English, French, German, Spanish, Romanian, Hungarian and Italian (Inclusion Europe. Europe for us, Figure 1).

Availability of Europe for us in several languages.

Nevertheless, a step forward was made in Romania at the end of 2018 when Emergency ordinance no. 112/2018 regarding the accessibility of websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies was adopted, thus establishing the framework that fostered the creation of accessible websites of official bodies. Consequently, public institutions started to turn their webpages into accessible ones (Figure 2), a process highly accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the distancing measures imposed in order to contain the disease (Șișu n.d.). For instance, 18 of the 34 public institutions listed on the website of the Government of Romania provide accessibility solutions for people with various impairments and/or disabilities (Guvernul României. Instituții publice) (Table 1). However, no materials in accessible languages exist on the website of the Government of Romania.

![Figure 2

Ministerul Familiei, Tineretului și Egalității de Șanse [Ministry of Family, Youth and Equal Opportunities] website.](/document/doi/10.1515/opli-2022-0217/asset/graphic/j_opli-2022-0217_fig_002.jpg)

Ministerul Familiei, Tineretului și Egalității de Șanse [Ministry of Family, Youth and Equal Opportunities] website.

Website accessibility of the public institutions on the website of the Government of Romania

| Public institutions on the website of the Government of Romania | Website accessibility |

|---|---|

| AGERPRES National Press Agency | YES |

| Authority for the Digitalization of Romania | |

| Constitutional Court | |

| Department for the Relation with Parliament | |

| Department for the Relation with Romanians Abroad | |

| General Secretariat of the Government | |

| Legislative Council | |

| Ministry of Culture | |

| Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration | |

| Ministry of Education | |

| Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Tourism | |

| Ministry of European Investments and Projects | |

| Ministry of Family, Youth and Equal Opportunities | |

| Ministry of Health | |

| Ministry of Interior Affairs | |

| Ministry of Justice | |

| Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure | |

| Rador Press Agency | |

| Chamber of Deputies | NO |

| Competition Council | |

| Financial Supervisory Authority | |

| Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development | |

| Ministry of Economy | |

| Ministry of Energy | |

| Ministry of Environment, Water and Forests | |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs | |

| Ministry of Labour and Social Solidarity | |

| Ministry of National Defence | |

| Ministry of Public Finance | |

| Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization | |

| Ministry of Sports | |

| National Cybersecurity Directorate | |

| President of Romania | |

| Senate of Romania |

Moreover, there are no official textbooks adapted to the needs of the children with disabilities or impairments. Hence, both teachers and parents have to adapt the teaching materials from the mainstream textbooks. In order to meet the needs of other people facing the same problems, they have even created websites (Figures 3 and 4) where such adapted materials may be uploaded for the use of the community (Chirciu 2019, Peticilă 2019, Cere un manual, Ema la școală). Still the need is higher than the materialisation of the actions taken.

![Figure 3

Cere un manual [Ask for a textbook] website.](/document/doi/10.1515/opli-2022-0217/asset/graphic/j_opli-2022-0217_fig_003.jpg)

Cere un manual [Ask for a textbook] website.

![Figure 4

Ema la școală [Ema at school] website.](/document/doi/10.1515/opli-2022-0217/asset/graphic/j_opli-2022-0217_fig_004.jpg)

Ema la școală [Ema at school] website.

Furthermore, adults do not experience a better situation since also at the university level, accessibility solutions in general and linguistic ones in particular are rather desired than implemented. Hence, although red flags have been shown for the last few years, things are still moving extremely slowly in the direction of building an inclusive educational system in Romania that offers professional development paths for all citizens (Bolborici and Bódi 2018, Chirciu 2019, Cere un manual, Diagnoza situației persoanelor cu dizabilități în România, Ema la școală, Fărcașiu et al. 2022, Guvernul României. Ministerul Muncii si Solidarității Sociale. Autoritatea Națională pentru Protejarea Drepturilor Persoanelor cu Dizabilități n.d., Peticilă 2019, Vrăşmaş 2014).

The audiovisual accessibility in Romania is also in its infant stage (Nicolae 2020, Sinu 2018, Varga 2017), although the legislative framework for implementing linguistic accessibility solutions was created in 2002 already (Legea nr. 504/11.07.2002 Legea audiovizualului). The interlingual translation is the most frequently encountered type since Romania is listed as a subtitling country. Intralingual subtitling is usually resorted to when regional pronunciation, unclear speaking, amateur films, audio or illegal recordings and spontaneous interviews are employed. From time to time, also SDH may appear on the screen. As for the oral translation, voiceover is sometimes heard in pre-recorded programmes. Interlingual interpreting is used during live events and interviews, while intralingual interpreting takes the form of sign language interpreting and it can be noticed during the major news bulletins (Nicolae 2020, Sinu 2018, Varga 2017). The conclusion drawn easily is that most of the audiovisual translation forms are not seen on the Romanian screens yet. For accessibility purposes, only SDH and sign language interpreting are used by the major broadcasting companies in Romania (Diagnoza situației persoanelor cu dizabilități în România, Nicolae 2020, Sinu 2018, Varga 2017). Even the Romanian television broadcasting company (Televiziunea română) that relies heavily on public funding and, as such, should serve all Romanian citizens, focuses mainly on sign interpreting in Romanian, not in minority languages, as a form of linguistic accessibility, disregarding other solutions that might be employed (Figure 5).

![Figure 5

Televiziunea română [Romanian Television Broadcasting Company] website.](/document/doi/10.1515/opli-2022-0217/asset/graphic/j_opli-2022-0217_fig_005.jpg)

Televiziunea română [Romanian Television Broadcasting Company] website.

While authorised sign language interpreting courses are organised in Romania by the Romanian Association of Authorised Sign Language Interpreters in nine locations across the country and there is also one optional course taught at a master’s level at Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca, there is only one course in audiovisual translation that is taught at a master’s level at George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science and Technology of Târgu Mureș (Table 2). As it can be noticed in Table 2, there are neither courses in accessible languages, nor accessible language translation and interpreting courses. This is a surprising, but somehow also expected result of the analysis of the curricula offered by the 7 bachelor’s degrees and 19 master’s degrees in Translation and Interpreting that are functioning in Romania at the moment. This situation partially explains the scarcity of linguistic accessibility in Romania because without an educational framework within which knowledge and skills are acquired, there are no experts in linguistic accessibility on the Romanian labour market.

BA and MA degrees in the field of translation and interpreting studies in Romania and the course offer in the field of linguistic accessibility

| University name | BA in the field of translation and interpreting studies | MA in the field of translation and interpreting studies | Courses in the field of linguistic accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| “1 Decembrie 1918” University of Alba Iulia | 1 BA degree | — | — |

| Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași | 1 BA degree | 1 MA degree | — |

| Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca | — | 2 MA degrees | Sign language |

| “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galați. | — | 2 MA degrees | — |

| “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology of Târgu Mureș. | — | 1 MA degree | Audiovisual translation: dubbing and subtitling for the hard-of-hearing |

| Hyperion University of Bucharest | — | 1 MA degree | — |

| “Lucian Blaga” University of Sibiu | — | 1 MA degree | — |

| Politehnica University of Timișoara | 1 BA degree | — | — |

| Sapientia University of Cluj-Napoca | 1 BA degree | — | — |

| “Ștefan cel Mare” University of Suceava | — | 1 MA degree | — |

| Technical University of Civil Engineering of Bucharest | 1 BA degree | 1 MA degree | — |

| University of Bucharest | 1 BA degree | 4 MA degrees | — |

| University of Craiova | 1 BA degree | 1 MA degree | — |

| University of Pitești | — | 2 MA degrees | — |

| West University of Timișoara | — | 1 MA degree | — |

| Sum total | 7 BA degrees | 18 MA degrees | 2 courses taught at MA degrees |

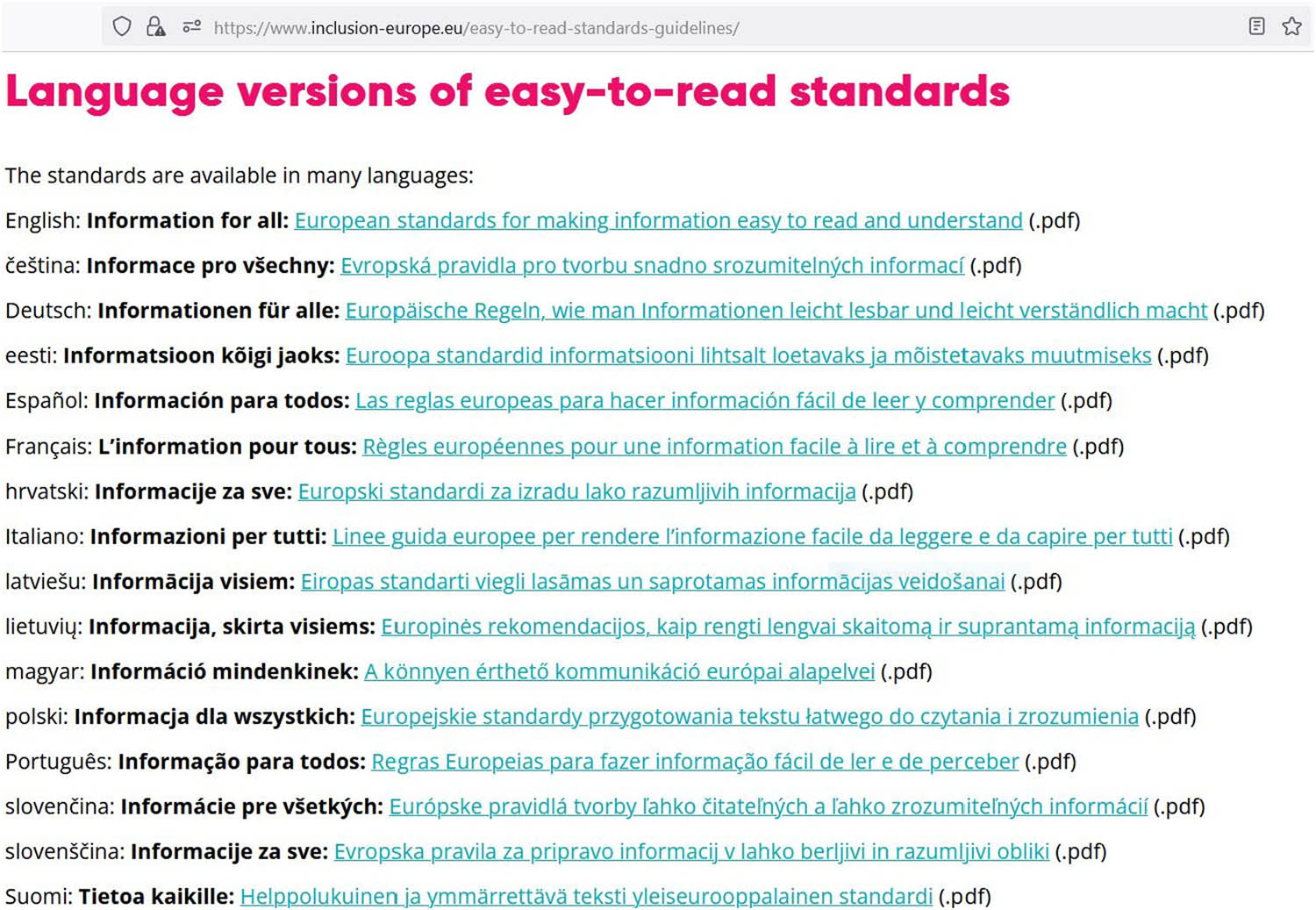

Furthermore, whereas in many European countries, guidelines for easy-to-read have been created and published, in Romania there are no guidelines for any accessible language, easy-to-read included, which also contributes to the lack of specialists in accessible languages on the labour market, be they teachers, professionals or researchers. Even on the Inclusion Europe website, guidelines for easy-to-read and understand in Romanian do not exist (Inclusion Europe. Information for all: European standards for making information easy to read and understand, Figure 6).

European guidelines for making information easy to read and understand, available in several languages.

5 Concluding remarks

Being rooted in the accessibility movement started by the United Nations last century, the field of accessibility has emerged as an interdisciplinary one, getting more and more attention in Europe. Since the European countries have decided to pursue a common goal, namely that of building an inclusive society to the benefit of all citizens, many actions have been taken to improve the access to information and knowledge. To overcome sensory, cognitive, motor, language, expert knowledge and/or language, cultural, media and motivational communication barriers (Lang 2021, Rink 2019, 2020), interlingual and intralingual translation and interpreting may be used. Although interlingual and intralingual translation and interpreting offered in standard languages are the most popular linguistic accessibility solutions, lately, with the creation of accessible languages, as we have termed all languages that have emerged or will emerge in the future as deviations from the standard ones have been employed, too, in an effort to make communication accessible to all people, irrespective of their disabilities or impairments. Additionally, with the development of the audiovisual sector, several translation and interpreting types have arisen to serve linguistic accessibility purposes.

Apart from this, for the informational content in a standard language to be translated or interpreted into an accessible one, translators and interpreters specialising in accessible languages are needed on the labour market. For this purpose, some competences must be developed while pursuing an academic education. As such, in Europe, courses in accessible language translation and interpreting have been established at a master’s level. Nevertheless, further research is necessary to develop a comprehensive educational framework for training specialists in accessible language translation and interpreting.

Romania, though a member state of the European Union, cannot boast about the same promising situation, in terms of linguistic accessibility, as the one existing in other European countries, neither regarding the formal education of the experts in linguistic accessibility, nor regarding the existence of linguistic accessibility solutions and products on the market and in the mass-media. Printed or digital materials in accessible languages are almost inexistent in Romanian, irrespective of the age group they address, although, at a European level, the digital easy-to-read magazine and newsletter Europe for us is published in Romanian as well as in several other languages. Regarding website accessibility, public institutions have turned institutional webpages into accessible ones as a result of the legislative measures taken in Romania. So, almost 53% of the webpages of the public institutions listed on the webpage of the Government of Romania are accessible to people with disabilities or impairments of various kinds. Still, no information in accessible languages is to be found.

Furthermore, adapted textbooks for people with various disabilities or impairments, in printed or digital formats, do not exist in Romania. Hence, parents and teachers had to create websites where such materials, conceived by themselves, can be uploaded and used for free.

As for the audiovisual accessibility in Romania, this is achieved through intralingual and interlingual subtitling, SDH, voiceover, interlingual interpreting, intralingual interpreting, i.e. sign language interpreting. Even the Romanian television broadcasting company offers sign interpreting services for the main news bulletins, but only in the Romanian language without considering the minority languages. However, in Romania, there are nine organisations that are authorised to teach courses in sign language interpreting, there is no course in accessible languages, and there are only two courses in audiovisual translation taught at a master’s level. This is rather surprising considering the new trends in linguistic accessibility in the European Union and the Romanian educational offer in terms of BA and MA degrees in translation and interpreting, i.e. 7 BA degrees and 18 MA degrees. The lack of courses and guidelines for accessible languages in Romanian partly explain the scarcity of linguistically accessible materials available either in standard languages or in accessible ones.

Therefore, although the legislative measures taken so far in Romania support the social inclusion of the people in need of linguistic accessibility, linguistically accessible solutions are almost inexistent. One major reason identified is the lack of trained professionals in the field of linguistic accessibility. Obviously, further research needs to be done to draft guidelines for accessible languages in Romanian, to create an educational framework within which the necessary competences are acquired by translators and interpreters specialising in accessible languages as well as to identify all the causes that have led to the disastrous situation of linguistic accessibility in Romania in order to find solutions to improve it.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest. D.D. is a member of the Open Linguistics Editorial Board. He was not, however, involved in the review process of this article. It was handled entirely by other editors of the journal.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Arias-Badia, B. and A. Matamala. 2020. “Audio description meets Easy-to-Read and Plain Language: results from a questionnaire and a focus group in Catalonia.” Zeitschrift für Katalanistik 33, 251–70.Search in Google Scholar

Baños, R. 2017. “Audiovisual translation.” In Manual of romance languages in the media, edited by K. Bedijs and C. Maaß, p. 471–88. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110314755-021Search in Google Scholar

Bernabé Caro, R. 2020. “New taxonomy of easy-to-understand access services.” In Traducción y Accesibilidad en los medios de comunicación: de la teoría a la práctica. MonTI 12, edited by Richart-Marset, Mabel and Francesca Calamita, p. 345–80. http://hdl.handle.net/10045/106621.10.6035/MonTI.2020.12.12Search in Google Scholar

Bernabé Caro, Rocío and Pilar Orero. 2019. “Easy to read as multimode accessibility service.” Hermēneus. Revista de Traducción e Interpretación 21, 53–74. 10.24197/her.21.2019.53-74.Search in Google Scholar

Bolborici, A.-M. and Bódi, D.-C. 2018. “Issues of special education in Romanian schools.” In European Journal of Education 1(3), September–December 2018, 135–39. https://revistia.org/files/articles/ejed_v1_i3_18/Bolborici.pdf.10.26417/ejed.v1i3.p135-141Search in Google Scholar

Bredel, Ursula and Christiane Maaß. 2016a. Leichte sprache. Theoretische Grundlagen, Orientierung für die Praxis. Berlin: Duden.Search in Google Scholar

Bredel, Ursula and Christiane Maaß. 2016b. Ratgeber Leichte sprache. Berlin: Duden.Search in Google Scholar

Buhalis, D. and Darcy, S. 2011. “Introduction: From disabled tourists to accessible tourism.” In Accessible tourism: Concepts and issues, edited by D. Buhalis and S. Darcy, p. 1–20. Bristol, United Kingdom: Channel View Publications.10.21832/9781845411626-004Search in Google Scholar

Chirciu, S. 2019. “Manuale gratuite pentru copiii cu cerinţe educaţionale speciale, disponibile online.” Adevarul. https://adevarul.ro/stiri-interne/educatie/manuale-gratuite-pentru-copiii-cu-cerinte-1969847.html (24.09.2022).Search in Google Scholar

Crystal, D. 2005. The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cutts, M. 2013. Oxford guide to plain English. Oxford: University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Dejica, D. and Dejica-Carțiș, A. 2020. “The multidimensional translator. Roles and responsibilities.” In Translation studies and information technology – new athways for researchers, teachers and professionals, edited by Dejica, D., C. Eugeni, and A. Dejica-Carțiș, p. 45–57. Timișoara: Editura Politehnica.Search in Google Scholar

Dejica, D., O. García Muñoz, S. Șimon, M. Fărcașiu, and A. Kilyeni. (eds.). 2022. The status of training programs for E2R validators and facilitators in Europe. CoMe Book Series – Studies on Communication and Linguistic and Cultural Mediation. Scuola Superiore per Mediatori Linguistici di Pisa, Italy. Lucca: Esedra.Search in Google Scholar

Dejica, Daniel, Simona Șimon, Marcela Fărcașiu, and Annamaria Kilyeni. 2022. “The background and training programs for E2R validators and facilitators in facts and figures. A European Perspective.” In The Status of Training Programs for E2R Validators and Facilitators in Europe. CoMe Book Series – Studies on Communication and Linguistic and Cultural Mediation. Scuola Superiore per Mediatori Linguistici di Pisa, Italy, edited by Dejica, D., O. García Muñoz, S. Șimon, M. Fărcașiu, and A. Kilyeni, p. 138–52. Lucca: Esedra.Search in Google Scholar

Eichmeyer, D. 2018. “Interpreting into plain language: accessibility of on-site courses for people with cognitive impairments.” In Proceedings of the 2nd Swiss Conference on Barrier-free Communication: Accessibility in educational settings (BFC 2018), edited by Pierrette Bouillon, Silvia Rodríguez and Irene Strasly, p. 32–5. https://bfc.unige.ch/files/7115/6925/3922/Proceedings_BFC2018.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Fărcașiu, Marcela, Daniel Dejica, Simona Șimon, and Annamaria Kilyeni. 2022. “Easy-to-read in Romania: current status and future perspectives in a European context.” Swedish Journal of Romanian Studies 5(1/2022), 221–40.10.35824/sjrs.v5i2.23692Search in Google Scholar

Floridi, L. 2015. “Introduction.” In The online manifesto. Being human in a hyperconnected era, edited by L. Floridi, p. 1–3. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-04093-6_1Search in Google Scholar

Garcia, S. F., E. A. Hahn, and E. A. Jacobs. 2010. “Addressing low literacy and health literacy in clinical oncology practice.” In The Journal of Supportive Oncology 8(2), 64.Search in Google Scholar

Greco, G.M. 2018. “The nature of accessibility studies.” Journal of Audiovisual Translation 1(1), 205–32.10.47476/jat.v1i1.51Search in Google Scholar

Grigoraș, V., M. Salazar, C. I. Vladu, and C. Briciu. (coord.). 2021. “Diagnosis of the situation of people with disabilities in Romania.” http://anpd.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Diagnosis-of-the-situation-of-persons-with-disabilities-in-Romania.pdf (25.05.2022).Search in Google Scholar

Hansen-Schirra, S. and C. Maaß. (eds.). 2020. Easy language research: text and user perspectives, p. 131–62. Berlin: Frank and Timme.10.26530/20.500.12657/42088Search in Google Scholar

Jakobson, R. 1959. “On linguistic aspects of translation.” In On translation, edited by Reuben A. Browner, p. 233–9. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP.Search in Google Scholar

Janelle, D. G. and D. C. Hodge. (eds.). 2000. Information, place and cyberspace: Issues in accessibility. New York, NY: Springer.10.1007/978-3-662-04027-0Search in Google Scholar

Lang, K. (2021). Auffindbarkeit, Wahrnehmbarkeit, Akzeptabilität: Webseiten von Behörden in Leichter Sprache vor dem Hintergrund der rechtlichen Lage. Berlin: Frank & Timme.10.26530/20.500.12657/58667Search in Google Scholar

Lindholm, C. and U. Vanhatalo. (eds.). 2021. Handbook of easy languages in Europe. Berlin: Frank and Timme GmbH Verlag.10.26530/20.500.12657/52628Search in Google Scholar

Litman, T. 2017. Evaluating accessibility for transportation planning: Measuring people’s ability to reach desired goods and activities. Victoria, Canada: Victoria Transport Policy Institute.Search in Google Scholar

Maaß, C. 2019. Übersetzen in Leichte Sprache. In Handbuch Barrierefreie Kommunikation, edited by Maaß, Christiane and Rink, Isabel, p. 273–302. Berlin: Frank and Timme.Search in Google Scholar

Maaß, C. 2020. Easy language – Plain language – Easy language Plus. Balancing comprehensibility and acceptability. Berlin: Frank and Timme GmbH Verlag für wissenschaftliche Literatur.10.26530/20.500.12657/42089Search in Google Scholar

Maaß, C. and S. Hernández Garrido. 2020. “Easy and plain language in audiovisual translation.” In Easy Language Research: Text and user perspectives, edited by Silvia Hansen-Schirra and Christiane Maaß, p. 131–62. Berlin: Frank and Timme.10.26530/20.500.12657/42088Search in Google Scholar

Maaß, C. and Rink, I. 2020. “Scenarios for easy language translation: How to produce accessible content for users with diverse needs.” In Easy language research: text and user perspectives, edited by Hansen-Schirra, Silvia and Maaß, Christiane, p. 41–56. Berlin: Frank and Timme.10.26530/20.500.12657/42088Search in Google Scholar

Murman, D. L. 2015. “The impact of age on cognition.” Thieme E-Journals: Seminars in Hearing 36(3), p. 111–21. 10.1055/s-0035-155511 (22.05.2022).Search in Google Scholar

Nicolae, C. 2020. “Subtitling for the deaf and hard-of-hearing audience in Romania.” Romanian Journal of English Studies, RJES 17(2020), 53–62.10.1515/rjes-2020-0007Search in Google Scholar

Nolan, J. 2005. Interpretation. Techniques and exercises. Cleveland, Buffalo, Toronto: Multilingual Matters Ltd.Search in Google Scholar

Orero, P. 2004. “Audiovisual translation: A new dynamic umbrella.” In Topics in audiovisual translation, edited by P. Orero, p. VII–XIII. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Benjamins.10.1075/btl.56.01oreSearch in Google Scholar

Orero, P. 2012. “Film reading for writing audio descriptions: A word is worth a thousand images?.” Emerging topics in translation: Audio description, edited by E. Perego, p. 13–28. Trieste, Italy: EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste.Search in Google Scholar

Orero, P. and A. Matamala. 2007. “Accessible opera: Overcoming linguistic and sensorial barriers.” Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 15, 262–77.10.1080/13670050802326766Search in Google Scholar

Peticilă, M. 2019. “Mama unei eleve cu CES a făcut manuale simplificate și le oferă gratuit. Cere ministrului Educației să adapteze manualele pentru copiii cu cerințe speciale.” Edupedu. https://www.edupedu.ro/mama-unei-eleve-cu-ces-a-facut-manuale-simplificate-si-le-ofera-gratuit-cere-ministrului-educatiei-sa-adapteze-manualele-pentru-copiii-cu-cerinte-speciale/ (24.09.2022).Search in Google Scholar

Pöchhacker, F. 2016. Introducing interpreting studies. London and New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315649573Search in Google Scholar

Prodan, A. C. 2017. “The sustainability of digital documentary heritage.” In Going beyond: Perceptions of sustainability in heritage studies, edited by M.-T. Albert, F. Bandarin and A. P. Roders, No. 2, p. 59–69. New York, NY: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-57165-2_5Search in Google Scholar

Pullin, G. 2009. Design meets disability. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rink, I. 2019. “Kommunikationsbarrieren.” In Handbuch Barrierefreie Kommunikation, edited by Maaß, Christiane and Rink, Isabel, p. 29–65. Berlin: Frank and Timme.Search in Google Scholar

Rink, I. 2020. Rechtskommunikation und Barrierefreiheit. Zur Übersetzung juristischer Informations- und Interaktionstexte in Leichte Sprache. Berlin: Frank and Timme.10.26530/20.500.12657/43215Search in Google Scholar

Sanchez, T. W. and M. Brenman. 2007. The right to transportation: Moving to equity. Chicago, IL: Planners Press.Search in Google Scholar

Schulz, Rebecca, Kirsten Czerner-Nicolas, and Julia Degenhard. 2020. “Easy language interpreting.” Easy language research: text and user perspectives, edited by Hansen-Schirra, Silvia and Christiane Maaß, p. 163–78. Berlin: Frank and Timme.Search in Google Scholar

Sinu, R. 2018. “Audiovisual translation in Romanian TV news programmes.” Linguaculture 2(2018), 129–45.10.47743/lincu-2018-2-0128Search in Google Scholar

Stephanidis, C. (ed.) 2009. The universal access handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.10.1201/9781420064995Search in Google Scholar

Stephanidis, C., and P. L. Emiliani. 1999. “Connecting to the information society: a European perspective.” Technology and Disability 10, 21–44.10.3233/TAD-1999-10104Search in Google Scholar

Șimon, S. 2017. “The interpreter’s DO’S and DON’TS.” British and American Studies XXIII, 275–82.Search in Google Scholar

Şimon, S. and C. E. Stoian, 2017. “Developing interpreting skills in undergraduate students.” In ICERI2017 Proceedings, edited by Gómez Chova, L, A. López Martínez, and I. Candel Torres, p. 6180–4. IATED Academy, iated.org.10.21125/iceri.2017.1604Search in Google Scholar

Șișu, I. 2020 “Pandemia arată că digitalizarea instituțiilor de stat nu este doar un moft.” Wall-Street. https://www.wall-street.ro/articol/Economie/258867/pandemia-arata-ca-digitalizarea-institutiilor-de-stat-nu-este-doar-un-moft.html#gref (24.09.2022).Search in Google Scholar

Varga, C. 2017. “Subtitling in Romania. General Presentation”. In Debating Globalization. Identity, Nation and Dialogue. Section: Language and Discourse. edited by Boldea, Iulian and Cornel Sigmirean. Tîrgu Mureş: Arhipelag XXI Press.Search in Google Scholar

Vrăşmaş, T. 2014. “Adults with disabilities as students at the university.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 142, 235–42.10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.584Search in Google Scholar

Witzel, J. 2019. “Ausprägungen und Dolmetschstrategien beim Schriftdolmetschen,” In Handbuch Barrierefreie Kommunikation, edited by Maaß, Christiane and Isabel Rink. p. 303–25. Berlin: Frank and Timme.Search in Google Scholar

Yaneva, V. 2015. “Easy-read documents as a gold standard for evaluation of text simplification output.” In Proceedings of the Student Research Workshop, p. 30–6.Search in Google Scholar

Webography

Cere un manual [Ask for a Textbook]. https://cereunmanual.ro/ (24.09.2022).

Diagnoza situației persoanelor cu dizabilități în România [Diagnosis of the situation of people with disabilities in Romania]. 2020. http://anpd.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Diagnoza-situatiei-persoanelor-cu-dizabilitati-in-Romania-2020-RO.pdf (24.09.2022).

Directive (EU) 2016/2102 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 October 2016 on the accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies. 2016. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32016L2102 (25.09.2022).

Directive (EU) 2018/1808 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 November 2018 amending Directive 2010/13/EU on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services (Audiovisual Media Services Directive) in view of changing market realities. 2018. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/1808/oj (25.09.2022).

Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the accessibility requirements for products and services. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2019.151.01.0070.01.ENG (25.09.2022).

Ema la școală [Ema at School]. https://emalascoala.ro/category/clasa-pregatitoare/ (24.09.2022).

Guvernul României. [Government of Romania]. https://gov.ro/ (24.09.2022).

Guvernul României. Instituții publice [Government of Romania. Public institutions]. https://gov.ro/ro/institutii/institutii-publice (24.09.2022).

Guvernul României. Ministerul Muncii si Solidarității Sociale. Autoritatea Națională pentru Protejarea Drepturilor Persoanelor cu Dizabilități [The Government of Romania. Ministry of Labor and Social Solidarity. National Authority for the Protection of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities]. http://anpd.gov.ro/web/ (20.05.2022).

IFLA – International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Guidelines for easy-to-read materials. Revision by Misako Nomura, Gyda Skat Nielsen, and Bror Tronbacke. The Hague: IFLA Headquarters. IFLA Professional Reports 120. 2010. https://www.ifla.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/assets/hq/publications/professional-report/120.pdf (25.05.2022).

IFLA – International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. LSN/IFLA Professional Reports. https://www.ifla.org/publications/lsn-ifla-professional-reports/ (25.05.2022).

Inclusion Europe Checklist on easy-to-read. https://www.inclusion-europe.eu/easy-to-read/ (16.02.2022).

Inclusion Europe. Europe for us. https://www.inclusion-europe.eu/europe-for-us/ (25.09.2022).

Inclusion Europe. Informação para todos! Regras Europeias para fazer informação fácil de ler e de perceber [Information for all! European Standards for making information easy to read and understand]. 2009. https://www.fenacerci.pt/web/LF/docs/7.pdf (15.12.2020).

Inclusion Europe. Information for all: European standards for making information easy to read and understand. https://www.inclusion-europe.eu/easy-to-read-standards-guidelines/ (16.02.2022).

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights (15.05.2022).

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights (15.05.2022).

Legea nr. 504/11.07.2002 Legea audiovizualului [Law no. 504/11.07.2002 Audiovisual Law]. https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/37503 (25.09.2022).

n.a. 2011. “Cognitive impairment: A Call for Action, Now!.” In Policymaker, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/cognitive_impairment/cogimp_poilicy_final.pdf (22.05.2022).

Ordonanţa de urgenţă nr. 112/2018 privind accesibilitatea site-urilor web şi a aplicaţiilor mobile ale organismelor din sectorul public [Emergency ordinance no. 112/2018 regarding the accessibility of websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies]. Monitorul Oficial, Partea I, nr. 1105/27.12.2018. https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/209421 (24.09.2022).

PACTE – Procés d’Adquisició de la Competència Traductora i Avaluació. https://grupsderecerca.uab.cat/pacte/en (16.02.2022).

PLAIN – Plain Language Action and Information Network. https://www.plainlanguage.gov/about/ (16.02.2022).

Polytechnic of Leiria. Master’s in Accessible Communication (B-Learning). https://www.rocapply.com/study-in-portugal/portugal-universities/polytechnic-of-leiria/masters-in-accessible-communication-(b-learning).html (25.09.2022).

Romanian Association of Authorized Sign Language Interpreters. http://ailg.ro/ (20.05.2022).

Televiziunea română. Site accesibilizat pentru persoane cu dizabilităţi [Romanian Television Broadcasting Company. Website Accessible for People with Disabilities]. http://www.tvr.ro/site-accesibilzat-pentru-persoane-cu-dizabilitati_36517.html (25.09.2022).

Train2Validate https://plenainclusionmadrid.org/train2validate/project/ (22.05.2022).

Universal Declaration of Human Rights https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (15.05.2022).

Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona. Course in Accessible Digital Communication: Easy-to-Understand Language. https://www.uab.cat/web/postgraduate/course-in-accessible-digital-communication-easy-to-understand-language/general-information-1345468608438.html/param1-4468_en/ (25.09.2022).

Universitatea “Dunărea de Jos” din Galați. Discurs specializat. Terminologii. Traduceri [“Dunarea de Jos” University of Galați. Specialized Discourse. Terminology. Translation]. https://litere.ugal.ro/files/educatie/plan_invatamant/2020/Pl_Inv_07_FL_2019_M_Discurs_specializat._Terminologii_traduceri_(in_limba_franceza).pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea “Dunărea de Jos” din Galați. Traducere și Interpretariat [“Dunarea de Jos” University of Galați. Translation and Interpreting]. https://litere.ugal.ro/files/educatie/plan_invatamant/2020/Pl_Inv_07_FL_2019_M_Traducere_si_interpretariat_(in_limba_engleza).pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea “Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu. Teoria și Practica Traducerii și Interpretării [“Lucian Blaga” University of Sibiu. Theory and Practice of Translation and Interpreting]. https://litere.ulbsibiu.ro/documente/planuri/Plan_M_TPTE_2020_2022.pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea”Ștefan cel Mare” din Suceava. Teoria și practica traducerii [“Ștefan cel Mare” University of Suceava. Theory and practice of translation]. http://litere.usv.ro/planmaster.html (25.09.2022).

Universitatea 1 Decembrie 1918 din Alba Iulia. Traducere și interpretare [“1 Decembrie 1918” University of Alba Iulia. Translation and interpreting]. http://istoriefilologie.uab.ro/index.php?pagina=date_pg_planuri_inv&id=49&l=ro (25.09.2022).

Universitatea Alexandru Ioan Cuza din Iași. Traducere și interpretare [Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași. Translation and interpreting]. https://litere.uaic.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Planuri-de-invatamant-LICENTA-2021-2022.pdf (pp. 38-42) (25.09.2022).

Universitatea Alexandru Ioan Cuza din Iași. Traducere și terminologie [Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași. Translation and Terminology]. http://media.lit.uaic.ro/wp-uploads/plinv-MASTER-2021-2022.pdf (pp. 17–18) (25.09.2022).

Universitatea Babeș-Bolyai din Cluj-Napoca. Masterat european de interpretare de conferință [Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca. European Master of Conference Interpreting]. http://masteric.lett.ubbcluj.ro/docs/curriculum.pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea Babeș-Bolyai din Cluj-Napoca. Masterat european de traductologie-terminologie [Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca. European Master in Translation and Terminology]. https://lett.ubbcluj.ro/mastertt/programa.html (25.09.2022).

Universitatea de Medicina, Farmacie, Științe și Tehnologie “George Emil Palade” din Târgu Mureș. Traducere multimodală [“George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology of Târgu Mureș. Multimodal Translation]. https://www.umfst.ro/fileadmin/master/Planuri/2021-2022/FSL/Plan_invatamant_TMM_2021_2022.pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea de Vest din Timișoara. Teoria si Practica Traducerii [West University of Timişoara. Theory and Practice of Translation (English and French)]. https://litere.uvt.ro/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/2019-2020_Pl-inv_MA_TPT.pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din București. Limba rusă aplicată. Tehnici de traducere [University of Bucharest.Translation techniques]. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1EnpJysRJ4cdZhumR5C1mwmwLdCsCMR0- (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din București. Masteratul European de Formare a interpreților de conferință [University of Bucharest. European MA for Training Conference Interpreters]. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1EnpJysRJ4cdZhumR5C1mwmwLdCsCMR0- (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din București. Traducere și interpretare [University of Bucharest. Translation and interpreting]. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/13COI9ul2oY32zkffDPQCTgdVdOnvIL4y (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din București. Traducere specializată și studii terminologice [University of Bucharest. Specialized Translation and Terminological Studies]. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1EnpJysRJ4cdZhumR5C1mwmwLdCsCMR0- (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din București. Traducerea textului literar contemporan [University of Bucharest. Translation of contemporary literary text]. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1EnpJysRJ4cdZhumR5C1mwmwLdCsCMR0- (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din București. Traductologie latino-romanică [University of Bucharest. Latin-Romance Translation]. https://lls.unibuc.ro/facultate/studii/planuri-de-invatamant/ (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din Craiova. Traducere si interpretare [University of Craiova. Translation and interpreting]. https://litere.ucv.ro/litere/ro/content/planuri-de-%C3%AEnv%C4%83%C8%9B%C4%83m%C3%A2nt (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din Craiova. Traducere și terminologii în context european [University of Craiova. Translation and Terminology in a European Context]. https://litere.ucv.ro/litere/sites/default/files/litere/Invatamant/Master/m-traducatori_2018.pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din Pitești. Limbaje specializate și traducere asistată de calculator [University of Pitesti. Specialized Languages and Computer-Aided Translation]. https://www.upit.ro/ro/academia-reorganizata/facultatea-de-teologie-litere-istorie-si-arte/departamentul-limbi-straine-aplicate2/programe-de-master-lsa/limbaje-specializate-si-traducere-asistata-de-calculator/plan-de-invatamant2 (25.09.2022).

Universitatea din Pitești. Traductologie – Limba engleză/Limba franceză. Traduceri în context european [University of Pitești. Translation Studies – English/French. Translation Studies in a European Context] https://www.upit.ro/admitere/oferta/programe-de-master/traductologie-limba-engleza-limba-franceza-traduceri-in-context-european-810 (25.09.2022).

Universitatea Hyperion din București. Comunicare interculturală și traducere profesională [Hyperion University of Bucharest. Intercultural communication and professional translation]. http://litere.hyperion.ro/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Plan-invatamant-Master-I-II.pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea Politehnica Timișoara. Traducere și interpretare [Politehnica University of Timișoara. Translation and interpreting]. https://sc.upt.ro/attachments/article/36/2021_2022_SC_TI_Anii_I-III_ZI_14sept_v1000.pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea Sapientia din Cluj-Napoca. Traducere și interpretare [Sapientia University of Cluj-Napoca. Translation and interpreting]. https://ms.sapientia.ro/ro/studenti/planuri-de-invatamant (25.09.2022).

Universitatea Tehnică de Construcții București. Traducere și interpretare [Technical University of Civil Engineering of Bucharest. Translation and interpreting]. https://fils.utcb.ro/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/STI_curriculum_2016-2021.pdf (25.09.2022).

Universitatea Tehnică de Construcții din București. Traducere și interpretare specializată [Technical University of Civil Engineering of Bucharest. Specialised Translation and Interpreting Studies]. https://fils.utcb.ro/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/MATIS_curriculum_2018-2019.pdf (25.09.2022).

University of Applied Sciences of Winterthur. Swiss Centre for Barrier-free Communication https://www.zhaw.ch/en/linguistics/research/barrier-free-communication/#c127149 (25.09.2022).

University of Hildesheim. MA in Accessible Communication. https://www.uni-hildesheim.de/en/leichtesprache/ma-barrierefreie-kommunikation/ (25.09.2022).

University of Mainz/Germersheim. Graduiertenkolleg “Einfach komplex – Leichte Sprache.” https://leichtesprache.uni-mainz.de/ (25.09.2022).

© 2022 Simona Șimon et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A perceptual study of language chunking in Estonian

- Metaphors of cancer in the Arabic language: An analysis of the use of metaphors in the online narratives of breast cancer patients

- A comparative corpus stylistic analysis of thematization and characterization in Gordimer’s My Son’s Story and Coetzee’s Disgrace

- On explaining stable dialect features: A real- and apparent-time study on the variable (en) in Austrian base dialects

- Between exonormative traditions and local acceptance: A corpus-linguistic study of modals of obligation and spatial prepositions in spoken Ugandan English

- When estar is not there: A cross-linguistic analysis of individual/stage-level copular sentences in Romance

- Acquisition of referentiality in elicited narratives of Estonian-speaking children

- Breaking the silence: A corpus-assisted analysis of narratives of the victims of an Egyptian sexual predator

- “Establish a niche” via negation: A corpus-based study of negation within the Move 2 sections of PhD thesis introductions

- Implicit displays of emotional vulnerability: A cross-cultural analysis of “unacceptable” embarrassment-related emotions in the communication within male groups

- Reconstruction of Ryukyuan tone classes of Middle Japanese Class 2.4 and 2.5 nouns

- The Communication of Viewpoints in Jordanian Arabic: A Pragmatic Study

- Productive vocabulary learning in pre-primary education through soft CLIL

- NMT verb rendering: A cognitive approach to informing Arabic-into-English post-editing

- Ideophones in Arusa Maasai: Syntax, morphology, and phonetics

- When teaching works and time helps: Noun modification in L2 English school children

- A pragmatic analysis of Shylock’s use of thou and you

- Linguistic repercussions of COVID-19: A corpus study on four languages

- Special Issue: Translation Times, edited by Titela Vîlceanu and Daniel Dejica

- Editorial

- Deviant language in the literary dialogue: An English–Romanian translational view

- Transferring knowledge to/from the market – still building the polysystem? The translation of Australian fiction in Romania

- “‘Peewit,’ said a peewit, very remote.” – Notes on quotatives in literary translation

- Equivalence and (un)translatability: Instances of the transfer between Romanian and English

- Categorizing and translating abbreviations and acronyms

- “Buoyantly, nippily, testily” – Remarks on translating manner adverbs into Romanian

- Performativity of remixed poetry. Computational translations and Digital Humanities

- Ophelia, more or less. Intersemiotic reinterpretations of a Shakespearean character

- Considerations on the meaning and translation of English heart idioms. Integrating the cognitive linguistic approach

- New trends in translation and interpreting studies: Linguistic accessibility in Romania

- Special Issue: Modification in Functional Discourse Grammar, edited by Thomas Schwaiger, Elnora ten Wolde, and Evelien Keizer

- Modification in Functional Discourse Grammar: State of the art and issues addressed

- Modification and context

- Modifier-numeral word order in the English NP: An FDG analysis

- English evidential -ly adverbs in the noun phrase from a functional perspective

- Variation in the prosody of illocutionary adverbs

- “It’s way too intriguing!” The fuzzy status of emergent intensifiers: A Functional Discourse Grammar account

- Similatives are Manners, comparatives are Quantities (except when they aren’t)

- Insubordinate if-clauses in FDG: Degrees of independence

- Modification as a linguistic ‘relationship’: A just so problem in Functional Discourse Grammar

- American Spanish dizque from a Functional Discourse Grammar perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A perceptual study of language chunking in Estonian

- Metaphors of cancer in the Arabic language: An analysis of the use of metaphors in the online narratives of breast cancer patients

- A comparative corpus stylistic analysis of thematization and characterization in Gordimer’s My Son’s Story and Coetzee’s Disgrace

- On explaining stable dialect features: A real- and apparent-time study on the variable (en) in Austrian base dialects

- Between exonormative traditions and local acceptance: A corpus-linguistic study of modals of obligation and spatial prepositions in spoken Ugandan English

- When estar is not there: A cross-linguistic analysis of individual/stage-level copular sentences in Romance

- Acquisition of referentiality in elicited narratives of Estonian-speaking children

- Breaking the silence: A corpus-assisted analysis of narratives of the victims of an Egyptian sexual predator

- “Establish a niche” via negation: A corpus-based study of negation within the Move 2 sections of PhD thesis introductions

- Implicit displays of emotional vulnerability: A cross-cultural analysis of “unacceptable” embarrassment-related emotions in the communication within male groups

- Reconstruction of Ryukyuan tone classes of Middle Japanese Class 2.4 and 2.5 nouns

- The Communication of Viewpoints in Jordanian Arabic: A Pragmatic Study

- Productive vocabulary learning in pre-primary education through soft CLIL

- NMT verb rendering: A cognitive approach to informing Arabic-into-English post-editing

- Ideophones in Arusa Maasai: Syntax, morphology, and phonetics

- When teaching works and time helps: Noun modification in L2 English school children

- A pragmatic analysis of Shylock’s use of thou and you

- Linguistic repercussions of COVID-19: A corpus study on four languages

- Special Issue: Translation Times, edited by Titela Vîlceanu and Daniel Dejica

- Editorial

- Deviant language in the literary dialogue: An English–Romanian translational view

- Transferring knowledge to/from the market – still building the polysystem? The translation of Australian fiction in Romania

- “‘Peewit,’ said a peewit, very remote.” – Notes on quotatives in literary translation

- Equivalence and (un)translatability: Instances of the transfer between Romanian and English

- Categorizing and translating abbreviations and acronyms

- “Buoyantly, nippily, testily” – Remarks on translating manner adverbs into Romanian

- Performativity of remixed poetry. Computational translations and Digital Humanities

- Ophelia, more or less. Intersemiotic reinterpretations of a Shakespearean character

- Considerations on the meaning and translation of English heart idioms. Integrating the cognitive linguistic approach

- New trends in translation and interpreting studies: Linguistic accessibility in Romania

- Special Issue: Modification in Functional Discourse Grammar, edited by Thomas Schwaiger, Elnora ten Wolde, and Evelien Keizer

- Modification in Functional Discourse Grammar: State of the art and issues addressed

- Modification and context

- Modifier-numeral word order in the English NP: An FDG analysis

- English evidential -ly adverbs in the noun phrase from a functional perspective

- Variation in the prosody of illocutionary adverbs

- “It’s way too intriguing!” The fuzzy status of emergent intensifiers: A Functional Discourse Grammar account

- Similatives are Manners, comparatives are Quantities (except when they aren’t)

- Insubordinate if-clauses in FDG: Degrees of independence

- Modification as a linguistic ‘relationship’: A just so problem in Functional Discourse Grammar

- American Spanish dizque from a Functional Discourse Grammar perspective