Abstract

This is an introduction to the Special Issue on Modification in Functional Discourse Grammar.

1 A general characterization of the Functional Discourse Grammar (FDG) model

As the name suggests, FDG positions itself within the functional paradigm: it views language first and foremost as a means of communication, and regards linguistic form as emerging from communicative function. More specifically, FDG takes a directional, “function-to-form” approach, taking as its input a speaker’s communicative intentions, which the grammar subsequently translates into the appropriate linguistic form. Within the functional paradigm, however, FDG takes a moderate stance. Thus, unlike radically functional approaches, which do not believe in the existence of stable function-form relations, FDG starts from the premise that, although subject to constant change, “in synchronic terms the grammar of a language is indeed a system, which must be described and correlated with function in discourse” (Butler 2003, 30). FDG thus “seeks to reconcile the patent fact that languages are structured complexes with the equally patent fact that they are adapted to function as instruments of communication between human beings” (Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, ix, cf. Dik 1997, 3).

This, in turn, has given rise to another important characteristic of the theory, namely its “form-oriented” nature, i.e. the fact that it only considers those pragmatic and semantic phenomena that are reflected in the morphosyntactic and/or phonological form of an utterance (e.g. Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, 39). This means that FDG makes a clear distinction between grammar on the one hand, and conceptualization, context and output, on the other. Finally, FDG differs from most other functional approaches in using a sophisticated formalism to allow for a concise and precise representation of both the functional and the formal properties of languages. Together, these characteristics provide FDG with a unique position in what Butler and Gonzálvez-García (2014) describe as “Functional-Cognitive space.”

2 The architecture of FDG

2.1 Distinctive features and overall organization

The general characteristics of FDG have naturally led to specific choices when it comes to the organization of the model. Thus, the “function-to-form” approach is mirrored in the model’s top-down orientation, which starts with the speaker’s intention and then works its way down to articulation. In this way, Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008, 13) observe, “FDG takes the functional approach to language to its logical extreme,” as pragmatics is taken to govern semantics, pragmatics and semantics to govern morphosyntax, and pragmatics, semantics and morphosyntax to govern phonology. The privileged role of pragmatics is further reflected in the fact that FDG does not take the clause as its basic unit of analysis, but the Discourse Act. This means that FDG can accommodate not only regular clauses, but also units larger than the clause, such as complex sentences, and units smaller than the clause, such as single phrases or words.

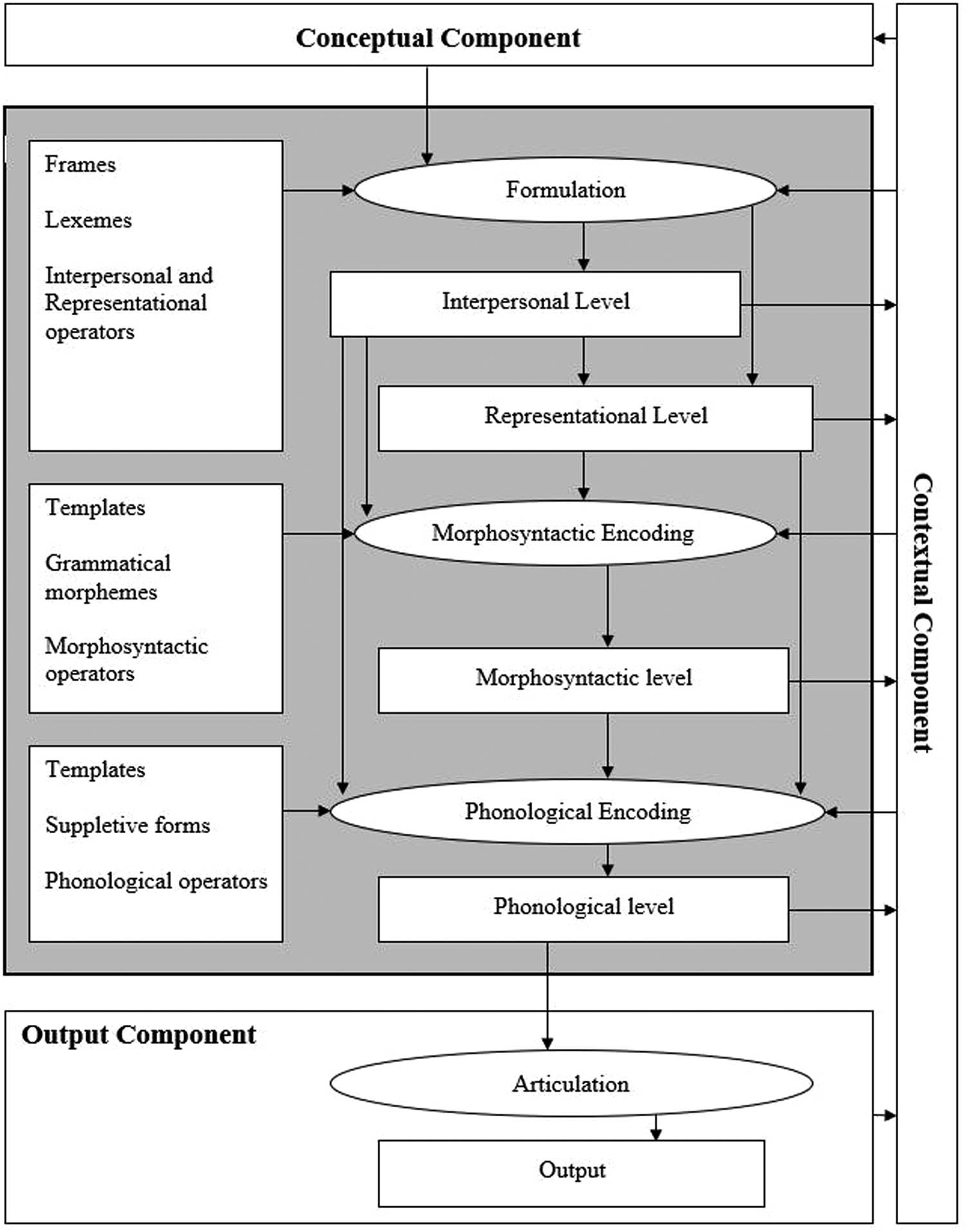

In order to represent all the linguistic information relevant for the formation of a linguistic expression, FDG analyses linguistic expressions at four separate, but interactive, levels of analysis, capturing all the systematically encoded pragmatic, semantic, morphosyntactic and phonological aspects of each expression. Together, these four levels form the Grammatical Component of the model (FDG proper). This component is part of a wider model of verbal communication in which it interacts with three other components: (i) a Conceptual Component, which contains the prelinguistic conceptual information (i.e. the speaker’s communicative intentions) relevant for the production of a linguistic expression and which forms the driving force behind the Grammatical Component (see also Connolly 2017); (ii) a Contextual Component, containing non-linguistic information from the immediate discourse context that affects the form of a linguistic utterance (see also Connolly 2007, 2014, Cornish 2009, Alturo et al. 2014, Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2014); and (iii) an Output Component, which turns the output of the Grammatical Component into acoustic, orthographic, or signed output (see also Seinhorst and Leufkens 2021). A general outline of the model is given in Figure 1.

General layout of FDG (based on Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, 13).

Apart from the four levels of analysis, Figure 1 also contains the different types of primitives feeding into the representations at each level. These primitives (given in boxes) can be regarded as the building blocks needed for the construction of an utterance: they are ready-for-use elements that together make up a speaker’s long-term knowledge of a specific language. Primitives come in three kinds. First, there are the structuring primitives (frames and templates), which define the possible combinations of elements at each level. These frames and templates consist of one or more slots which can be filled by lexical or grammatical information; some of these slots are provided with functions indicating the role of an element within the frame. The second set of primitives consists of the relevant linguistic elements at each level: lexemes (at the Formulation levels) and grammatical morphemes and suppletive forms (at the Encoding levels). The third set of primitives contains operators, which represent grammatical information at each of the levels, e.g. identifiability of a referent at the Interpersonal Level, and number, tense and aspect at the Representational Level.

In constructing a linguistic utterance, the speaker first selects the appropriate primitives, starting with the (interpersonal and representational) frames, followed by the lexical and grammatical elements to fill the slots within the frames. These primitives subsequently feed into the operation of Formulation, which results in representations at the higher two levels. This information then forms the input of the two operations of Encoding, where the relevant primitives for those levels are translated into representations at the Morphosyntactic and Phonological Levels.

Each of these levels of analysis consists of a number of hierarchically structured layers, representing a particular kind of linguistic unit. In the next section, the four levels and their internal structure will be discussed in greater detail.

2.2 Four levels of analysis

The Interpersonal Level is the first and highest level of representation, and it deals with pragmatic information, i.e. “all the formal aspects of a linguistic unit that reflect its role in the interaction between the Speaker and the Addressee” (Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, 46). The highest layer at this level is the Move (M), encompassing an entire segment of relevant discourse. Each Move is made up of one or more Discourse Acts (A) that form its (potentially complex) Head. A Discourse Act, in turn, comprises an Illocution (F), the Speech Act Participants (PS and PA) and a Communicated Content (C). On the Communicated Content layer the Speaker can evoke one or more Subacts of Reference (R) and/or Ascription (T). On each of these layers, slots are provided for modifiers (expressing additional lexical information) and operators (representing additional grammatical information).

The different interpersonal layers are illustrated in (1):

(1) a) Unfortunately, the dingo ate a koala.

b) (MI: (AI: [(FI: decl (FI)) (PI)S (PJ)A (CI: [(TI) (+id RI)Top (-id RJ)Foc] (CI): unfortunately (CI))] (AI)) (MI))

Example (1b) shows a Move which contains a single Discourse Act. This Discourse Act is composed of a declarative (DECL) Illocution, the two Speech Act Participants and a Communicated Content. The latter is made up of an Ascriptive Subact that evokes the property ‘eat’ and two Referential Subacts that evoke the entities dingo and koala. Both Subacts of Reference are specified by an identifiability operator: +id indicates that the Speaker assumes the Addressee will be able to identify the entity evoked by RI (and therefore triggers the use of the definite article during Morphosyntactic Encoding) and -id shows that the Speaker assumes the entity evoked by RJ will be unidentifiable for the Addressee (which then triggers the use of the indefinite article during Morphosyntactic Encoding). The two Referential Subacts also have a pragmatic function: The first is assigned the function of Topic (Top), marking the entity in question as relevant to the current discourse and linking it to information stored in the Contextual Component. The second is assigned the function of Focus (Foc), which marks this Subact as providing new or the most salient information within the Discourse Act. This results in prosodic prominence during Phonological Encoding. The Communicated Content, finally, is modified by the attitudinal adverb unfortunately, which indicates the Speaker’s subjective attitude towards the related content. Because of the interpersonal (Speaker-oriented) function of unfortunately, this adverb is lexically specified already at the Interpersonal Level. All the other lexical elements in (1a) have a descriptive function and thus appear at the next level.

The second level is the Representational Level and deals with the semantic information of a linguistic expression, i.e. those aspects of a linguistic unit that reflect “the ways in which language relates to the extra-linguistic world it describes” (Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, 128). Accordingly, the layers at this level capture the different linguistically relevant types (or orders) of entities with respect to this extra-linguistic world (Lyons 1977, 442–7, Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, 131). The highest of these layers is the Propositional Content (p), which is a mental entity type evaluable in terms of its truth. A Propositional Content consists of one or more Episodes (ep), which, in turn, are sets of States-of-Affairs (e). Episodes are considered coherent units in that they share temporal, spatial and participant specifications. A State-of-Affairs itself consists of a Configurational Property (fc), containing typically a verbal Property (f) and one or more Individuals (x). The Individuals usually have a nominal Property (f) as their respective head and often function as the arguments within a selected frame.

An illustration is given in (2):

(2) a) Last week the rabid dingo ate a koala.

b) (pi: (past epi: (ei: (fci: [(fj: eat (fj)) (1xi: (fk: dingo (fk)) (xi): (fl: rabid (fl)) (xi))A (1xj: (fm: koala (fm)) (xj))U] (fci)) (ei)) (epi): (ti: last week (ti)) (epi)) (pi))

Sentence (2a), with its analysis on the Representational Level in (2b), consists of a Propositional Content pi made up of a single Episode epi. This Episode comprises one State-of-Affairs ei, with a Configurational Property fc i as its head. The Configurational Property contains the verbal Property fj (eat) and two Individuals xi and xj. Each Individual has a nominal head (fk and fm, representing the Properties ‘dingo’ and ‘koala’, respectively). The sentence also displays two different modifiers and two types of operators. The modifiers are the temporal modifier last week (ti), modifying the Episode layer, and the adjectival modifier rabid (fl), modifying the first argument xi. The operators are the past tense operator ‘past’ at the layer of the Episode and the singular operator ‘1’ at the respective layers of the two Individuals. Finally, the semantic roles of Actor (A) and Undergoer (U) are assigned to the two Individual arguments, respectively. Here, pragmatic and semantic Formulation ends and the next two levels, the Morphosyntactic Level and the Phonological Level, are part of the formal Encoding, during which no further components of meaning can be added.

The Morphosyntactic Level captures the linear properties of, on the one hand, sentences, clauses and phrases, and, on the other hand, the internal structure of complex words. The highest layer at the Morphosyntactic Level is the Linguistic Expression (Le), which may consist of one or more Clauses (Cl). Clauses typically contain one or more Phrases and Words, as well as, potentially, other Clauses. Phrases, in turn, may consist of one or more Words, other Phrases or Clauses. Finally, at the lowest layer, Words contain one or more Morphemes belonging to one of three types: Stems (which have lexical content and can be the sole element within a Word), Roots (which have lexical content and can only be used with another Stem or Root) or Affixes (which lack lexical content and can only be used in combination with a Stem or Root). Phrases, Words, Stems and Roots are classified further with respect to their head, for instance as Verbal Phrases (Vp), Nominal Phrases (Np) and Adjectival Phrases (Ap), as well as Verbal Words (Vw), Nominal Words (Nw) and Adjectival Words (Aw). Grammatical Words (Gw) tend to correspond to operators at the Formulation levels. By way of exemplification, a morphosyntactic representation of sentence (3a) is given in (3b):

(3) a) The dingo ate a koala.

b) (Lei: (Cli: [(Npi: [(Gwi: The (Gwi)) (Nwi: (Nsi: dingo (Nsi)) (Nwi))] (Npi)) (Vpi: (Vwi: eat-past (Vwi)) (Vpi)) (Npj: [(Gwj: a (Gwj)) (Nwj: (Nsj: koala (Nsj)) (Nwj))] (Npj))] (Cli)) (Lei))

The Phonological Level is the lowest level and usually receives its input from all the other levels above it.[1] The highest phonological layer is the Utterance (U). It contains one or more Intonational Phrases (IP), which, in turn, are made up of one or more Phonological Phrases (PP). A typical Phonological Phrase contains one or more Phonological Words (PW). Phonological Words are further broken down into Feet (F) and Syllables (S). The representation in (4b) gives a simplified phonological analysis of the example sentence (4a). This representation also contains an operator ‘f,’ which serves to indicate a falling intonation at the Intonational Phrase layer.

(4) a) The dingo ate.

b) (f ipi: [(ppi: /ðəˈdɪŋɡəʊ/ (ppi)) (ppj: /eɪt/ (ppj))] (ipi))

3 Modification in FDG: state of the art

As we have seen above, modification takes place at both the Interpersonal and the Representational Level, where each modifier belongs to (scopes over) a particular interpersonal or representational layer. In what follows, we will first explain the difference between modifiers on the one hand, and operators and functions on the other (Section 3.1). Subsequently, we will look at the difference between interpersonal and representational modifiers (Section 3.2). Next, we will discuss the criteria used for establishing the exact scope (layer) of a modifier (Section 3.3).

3.1 Modifiers vs operators and functions

As mentioned above, FDG makes a distinction between lexical elements (functioning as heads of interpersonal or representational layers) and grammatical elements (operators and functions, providing grammatical information about a layer). Although it is acknowledged that the difference between lexical and grammatical information is not a strict one, with the former often gradually developing into the latter through processes of grammaticalization, the distinction is nevertheless regarded as crucial, as lexical and grammatical elements exhibit different formal behaviour.

In FDG, the distinction between the lexical and grammatical elements is based mainly on two criteria: modifiability and focalizability. Thus, lexemes are those (free) morphemes that allow for modification and can be assigned focus function. Elements that can neither be modified nor focalized (typically bound morphemes) are analysed as operators or functions. In addition, FDG recognizes an in-between category of elements that fulfil only one of the two criteria (Keizer 2007, Hengeveld 2017, 31). For instance, many free grammatical morphemes (e.g. demonstrative determiners, quantifiers, conjunctions, auxiliary verbs, etc.) can be focalized, but not modified. Such elements are analysed as lexical operators (Keizer 2007, Hengeveld 2017, 31) or functions (Giomi 2020, 325, 346–8), reflecting their in-between status on the lexical-grammatical continuum (see also Giomi, this issue; Olbertz, this issue; Portero Muñoz, this issue; Ten Wolde and Schwaiger, this issue).

The various options are illustrated in example (5) for the layer of the Individual (x). In (5a), we have two lexemes heading the lexical Properties (fi) and (fj). Both these Properties are modifiable: in example (5a) the Property ‘student’ is modified by the Property ‘diligent,’ which in turn is modified by the Property ‘extreme’ (fk).[2] The indefinite article a, on the other hand, is a grammatical element, triggered by the singularity operator ‘1’ (in combination with the unidentifiability (-id) operator at the Interpersonal Level). In (5b), on the other hand, the demonstrative determiner that (focalizable, but not modifiable) is represented as a lexical operator.

(5) a) an extremely diligent student

(1 xi: (fi: student (fi)) (xi): (fj: diligent (fj): (fk: extreme (fk)) (fj)) (xi))

b) that student

(that xi: (fi: student (fi)) (xi))

3.2 Interpersonal and representational modifiers

As we have seen, modifiers can be added at both the Interpersonal Level (see example (1)) and the Representational Level (see examples (2) and (5)). Modification at these two levels is different, first and foremost, in terms of function. Interpersonal modifiers have a Speaker-oriented function, such as expressing the Speaker’s attitude towards (e.g. unfortunately, surprisingly) or emphasizing the Communicated Content (e.g. absolutely, totally), or indicating the Speaker’s manner of carrying out the Illocution (e.g. frankly, honestly), or indicating that the Communicated Content has been obtained from another source (e.g. allegedly, supposedly) (see also Kaltenböck and Keizer, this issue; Kojadinović, this issue). On the other hand, representational modifiers function as additional specifications in that they provide additional information about the extra-linguistic entities that are captured by the various semantic categories at the Representational Level. Therefore, subjective modality adverbs (e.g. hopefully) modify the Propositional Content, reality (e.g. actually) and frequency (e.g. frequently) adverbs the State-of-Affairs, manner adverbs (e.g. angerly) a verbal Property, etc. Similarly, adjectives like poor in poor Jane (expressing the Speaker’s sympathy towards a referent) and utter in an utter fool (intensifying the Property denoted by the following noun) are represented at the Interpersonal level, whereas descriptive adjectives, denoting properties of a referent in the extra-linguistic world (either objectively, e.g. ‘red’, ‘square’ or subjectively, e.g. ‘kind’, ‘awful’) are analysed at the Representational Level (see also García Velasco, this issue; Keizer, this issue; Kemp and Hengeveld, this issue).

Interpersonal and representational modifiers can, according to Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008, 128–9), be distinguished by their differences in truth-conditionality, as shown in examples (6) and (7):

(6) Frankly, Sheila is ill.

a) No. (She isn’t.)

b) *No. (You are not being frank.)[3]

(7) Peter told me frankly that Sheila is ill.

a) That’s not true. (She isn’t.)

b) That’s not true. (He was not being frank.)

(Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, 128–9)

In (6), the speaker can deny the whole Propositional Content (see (6a)), but not the information expressed by the interpersonal adverb frankly (see (6b)); therefore, frankly cannot be part of the Propositional Content, and is, hence, non-truth-conditional. In (7), frankly is a representational (manner) adverb and, therefore, part of the Propositional Content, so that it is possible to negate the adverb. This adverb in this context is then truth-conditional (see (7b)).

Further support for the distinction between the two groups of modifiers is found in their relative ordering within the clause or phrase. According to the top-down and outward-inward placement of linguistic units during linearization at the Morphosyntactic Level (see Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, 311–4, 377–80), interpersonal adverbs will most likely be placed in the (left) periphery of the clause, with representational adverbs being given more central positions; this is demonstrated in (8a). In this example, unfortunately comes before the representational (evidential) adverb presumably (Keizer 2015, 189).[4] In the same way, in (8b), the interpersonal adjective poor (expressing the Speaker’s sympathy for the entity evoked) is placed more peripherally than the representational (descriptive) adjective innocent (Keizer 2015, 190, 220–1):

8) a) She unfortunately presumably saw him again last week.

b) a poor innocent dinosaur

3.3 Determining the scope of interpersonal and representational modifiers

Just like we need criteria to determine whether a modifier is interpersonal or representational, we also need criteria to determine which exact interpersonal or representational layer a modifier belongs to. As already mentioned in the previous section, the starting point for assigning a modifier to a particular layer is the function it performs (e.g. Keizer 2018a,b, 2020, Kemp 2018). The scope of modifiers is, however, also reflected in their formal behaviour. Thus, as in the case of interpersonal and representational modifiers, modifiers within each level also tend to appear in a relative order reflecting their scope, with modifiers of higher layers occurring in more peripheral positions than those of lower layers. An example can be found in (8a), where the temporal modifier last week, modifying the Episode, is in a more peripheral position than the frequency modifier again, which scopes over the State-of-Affairs within the Episode.

Further evidence for the scope of an interpersonal or representational modifier comes from coordination, since only modifiers scoping over the same layer tend to be coordinated. Thus, example (9a), where the two subjective modality adverbs probably and certainly are coordinated, is fully acceptable, whereas (9b), where certainly is coordinated with the factuality adverb really (scoping over the State-of-Affairs), is at best questionable (see Keizer 2018a,b, 2020):

(9) a) Bull was always, first and foremost, a virtuoso both of technical invention and obviously of performance, even in compositions probably or certainly intended for the organ where he appears as the direct heir of Preston and Blitheman. (BYU-BNC, non-academic)[5]

b) ?*… even in compositions really and/or certainly intended for the organ where he appears as the direct heir of Preston and Blitheman.

Finally, the scope of a modifier determines whether or not it can occur in the complement of a specific verb or noun (Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, 363–5). For instance, since the propositional attitude verb believe in (10a) takes a Propositional Content as its complement, this complement can contain adverbs modifying this layer, such as probably, as well as all lower-layer modifiers, such as the factuality adverb really; it cannot, however, contain (prosodically integrated) higher-layer (interpersonal) adverbs like reportedly (which modifies the Communicated Content). In (10b), we find the aspectual verb continue, which takes as its complement a Configurational Property. As such, this complement can only contain modifiers that occur at the layer of the Configurational Property or lower layers, such as the manner adverb systematically; modifiers belonging to higher layers, such as probably, are, however, not allowed.

(10) a) Eventually Angel came to believe that she probably/really/*reportedly had killed d’Urberville. (BYU-BNC, fiction; adapted)

b) The real irony is that if Israel continues to systematically/*probably close all community service institutions … (BYU-BNC, non-academic; adapted)

4 FDG and language change

When it comes to systematic changes in the function and form of linguistic elements, the distinctive features of FDG (its top-down orientation, as well as the presence of hierarchically organized levels and layers of analysis) allow for the formulation of certain expectations. In accordance with the functional, top-down approach taken, it is assumed that it is the Speaker’s need to express new meaning that initiates changes in the language system. In the first instance, speakers will use existing primitives to express a new communicative intention, the correct interpretation of which will depend on the context in which it is used. Gradually, this may lead to the emergence of new patterns in discourse, which in turn may become conventionalized as the grammar adapts itself to the new situation. As soon as the relation between the new meaning and the new form has become sufficiently systematic, it will be regarded as part of the grammar. These processes may involve a language’s lexicon as well as its grammar. The scenario below briefly demonstrates how these processes can be captured in FDG.

The process of grammaticalization can be defined as the change of a lexical element (or elements) to a new grammatical element (i.e. an operator or function). Grammatical elements can also grammaticalize further, moving outward to the next layer or upward to the next level (e.g. Boland 2006, Hengeveld 2011, Dall’Aglio Hattnher et al. 2016, Giomi 2017, Olbertz and Honselaar 2017, Giomi 2020). A classic example from the grammaticalization literature is the development of English will (Bybee et al. 1991, see also Hengeveld 2011). This is initially a lexical verb, then begins to function as an indicator of obligation and intention, afterward developing into a posterior marker, then a future marker, and ultimately a marker of supposition (a form of inference, as in The children will be finished with dinner by now). Table 1 shows how this process would be modelled at the Representational Level.

| Inference | Future | Posteriority | Obligation/intention | Lexical verb (OE willan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evidentiality | Absolute tense | Relative tense | Participant-oriented modality | Verbal property |

| p | ep | e | fc | f |

|

||||

Something similar is predicted by FDG for processes of semantic change such as ‘subjectification’ (e.g. Traugott 1995, Traugott and Dasher 2002), which involves a lexical item moving up to a higher layer of the same level. Thus, manner adverbs may gradually assume new, more subjective meanings, causing them to move up in the hierarchy. The adverb deliberately, indicating the manner in which an action is performed (as in She rose very deliberately from her chair), for instance, has developed a more subjective meaning, indicating the subject’s mental attitude towards the State-of-Affairs as a whole (in this case intention: She deliberately didn’t look at him), i.e. from the layer of the lexical Property to the layer of the State-of-Affairs (see also Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008, 209). In many cases, representational adverbs develop an interpersonal meaning, as in the case of the adverb frankly (from a manner adverb scoping over a Property at the Representational Level to an Illocutionary adverb at the Interpersonal Level) or the adjective poor (from a descriptive Property to an expression of sympathy) (see also Olbertz, this issue; Ten Wolde and Schwaiger, this issue). In such cases, we are dealing with the (additional) process of pragmaticalization.

5 Issues addressed in this special issue

A number of publications have been dedicated to specific kinds of modification within the framework of FDG and its predecessor, Dik’s Functional Grammar (FG). Some early work on the classification of adverbs in FG can be found in Hengeveld (1989, 1997), while a series of more recent papers have developed these early ideas within the theory of FDG: Keizer (2018a) deals with modal adverbs, Keizer (2018b) with the illocutionary adverb frankly, Kemp (2018) with evidential adverbs, Keizer (2020) with stance adverbs and Keizer (2019) with the non-restrictive use of adverbs like cleverly and stupidly. When it comes to adjectival modification, Van de Velde (2007, 2009, 2011) studies the (increasing) use of interpersonal modifiers within the noun phrase, Mackenzie (2013) offers an FDG analysis of different types of secondary predications, García Verlasco (2013) deals with degree modification, Ten Wolde (2018) with premodification in evaluative binominal noun phrases and Keizer (2022) with premodification patterns in fact/point is constructions. Finally, Ten Wolde (2021) offers an FDG treatment of postnominal modifiers. Nevertheless, there are still a large number of unresolved issues and unexplored areas when it comes to the analysis of modifiers in FDG. The aim of the current collection of papers is to address some of these issues and to offer new analyses of a range of modifiers at the clausal and phrasal level.

The first two papers are concerned with premodification within the noun phrase (the first addressing the role of the general notion of compositionality, the second focusing on NPs with prenominal adjectives):

Looking at privative (e.g. fake), non-subsective (e.g. alleged) and relative (e.g. tall) adjectives, Daniel García Velasco argues that FDG can no longer maintain a strict distinction between interpersonal and representational modifiers. In particular, he argues that adopting a weak notion of compositionality is not only in keeping with the basic principles of FDG, but, by assigning a more prominent role to context, also allows the model to capture more precisely the semantics of the kinds of modifiers investigated.

Using English corpus data, Evelien Keizer investigates noun phrases in which a modifier precedes a numeral (e.g. a staggering 30 singles, that short 14 months). After showing that such NPs are far more heterogeneous than previously assumed, she argues that the variation observed can only be accounted for if different subtypes are distinguished. She demonstrates how FDG can be used to capture the main features of the construction as a whole, as well as the more specific semantic and syntactic properties of each subtype.

The next two papers provide detailed analyses of groups of adverbs (evidential adverbs within the noun phrase, illocutionary adverbs at the clausal level):

Lois Kemp and Kees Hengeveld examine the use of evidential -ly adverbs within the noun phrase. In a corpus-based study, they discuss the distribution of these adverbs and classify the types of adjectives that these adverbs modify. In particular, they demonstrate how FDG as a model can capture the features and functions of these adverb-adjective combinations (e.g. restrictiveness, permanence) and discuss how these would explain the distribution patterns found in the study. They end by discussing the pragmatic effects of the presence of evidential adverbs in the noun phrase.

Zlatan Kojadinović looks at the complex relation between the prosody and the discourse pragmatic functions of the English illocutionary adverbs frankly, honestly and seriously. In a qualitative, corpus-based study, using the speech analysis software Praat, he empirically substantiates previous FDG hypotheses concerning the interplay between the Interpersonal Level and the Phonological Level in this research area. Specifically, he shows the need for a discourse-functional approach to the so-called syntax-prosody interface, while at the same time accounting for the variation in the prosodic features of the three modifiers in question.

We then move on to a discussion of degree modifiers (simple and constructionalized ones) and from there to synchronic accounts of various constructionalized modifiers:

Carmen Portero Muñoz, in a larger corpus study, explores the form, function and linguistic classification of a number of non-prototypical degree words and phrases in Spanish and English: the single lexemes muy, way, proper and bare, and the syntactically complex phrase no, lo siguiente. Using some of the specific features of FDG, such as the distinction between interpersonal and representational information, as well as the distinction between modifiers, operators and lexical operators, she suggests analyses for these elements that capture the semantic and pragmatic differences between them.

Mainly based on English data, but occasionally also referring to Latin and several modern Romance languages, Riccardo Giomi investigates similative (e.g. She sings like a nightingale) and comparative (e.g. John is more intelligent than his brother) constructions within the FDG framework. He argues that the two types of modifying construction have an identical structure but different semantic categories in that the former are Manners and the latter are Quantities. Moreover, the author gives a principled account of a range of exceptional cases for which this basic characterization does not hold. Finally, he offers an alternative treatment of the alternation between the analytic and synthetic expression of comparative constructions.

Gunther Kaltenböck and Evelien Keizer discuss the function of insubordinate if-clauses in English and Dutch (e.g. if you want or if only). Linking functional features with formal ones, they group insubordinate if-clauses into three categories: modifiers of different layers on the Interpersonal Level, Subsidiary Discourses Acts pragmatically dependent on another Discourse Act, and autonomous Discourse Acts. Looking at synchronic corpus data, the paper demonstrates the formal features of each of the uses of insubordinate if-clauses follow from their status at the Interpersonal Level.

The final two papers offer diachronic accounts of (grammaticalizing/grammaticalized and lexicalized) elements:

Using corpus data, Elnora ten Wolde and Thomas Schwaiger track the development and union of English just and so from just functioning as a focus particle modifying so as a degree word and manner proform (e.g. She is just so wrong), via just so together functioning as a subordinator of purpose and condition (e.g. We need to have kids, just so I can justify the toys) to, finally, just so as part of the pragmatic marker just so you know. They demonstrate how FDG can model the ‘courtship’ and subsequent ‘marriage’ of just and so at the different stages of this process.

Hella Olbertz explores the diachrony of the reportative adverb dizque in American (Colombian and Mexican) Spanish. On the basis of written corpus data from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, she argues this predominantly interpersonal modifier to be the result of lexicalization instead of grammaticalization, and treats it as a lexical item showing gradual scope decrease in its various uses. While FDG would expect an increase of functional scope for grammaticalizing elements, the author thus demonstrates that the development of lexicalized items may also go in the opposite direction.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state there is no conflict of interest.

References

Alturo, Núria, Evelien Keizer, and Lluís Payrato, eds. 2014. “The interaction between context and grammar in Functional Discourse Grammar.” Pragmatics 24(2) (special issue). 10.1075/prag.24.2.Search in Google Scholar

Bellert, Irena. 1977. “On semantic and distributional properties of sentential adverbs.” Linguistic Inquiry 8(2), 337–50.Search in Google Scholar

Boland, Annerieke. 2006. Aspect, Tense and Modality: Theory, Typology, Acquisition. Utrecht: LOT.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, Christopher S. 2003. Structure and Function: A Guide to Three Major Structural-Functional Theories. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.63Search in Google Scholar

Butler, Christopher S. and Francisco Gonzálvez-García. 2014. Exploring Functional-Cognitive Space. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 10.1075/slcs.157.Search in Google Scholar

Bybee, Joan, William Pagliuca, and Revere Perkins. 1991. “Back to the future.” In Approaches to Grammaticalization, Vol. 2: Types of Grammatical Markers, edited by Traugott, Elisabeth Closs and Bernd Heine, p. 17–58. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 10.1075/tsl.19.2.04byb.Search in Google Scholar

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and Functional Heads: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195115260.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Connolly, John H. 2007. “Context in Functional Discourse Grammar.” Alfa – Revista de Lingüística 51(2), 11–33.Search in Google Scholar

Connolly, John H. 2014. “The Contextual Component within a dynamic implementation of the FDG model: Structure and interaction.” Pragmatics 24(2), 229–48. 10.1075/prag.24.2.03con.Search in Google Scholar

Connolly, John H. 2017. “On the Conceptual Component of Functional Discourse Grammar.” Web Papers in Functional Discourse Grammar 89.10.1515/9783110197112.89Search in Google Scholar

Cornish, Francis. 2009. “Text and discourse as context: Discourse anaphora and the FDG Contextual Component.” In The London Papers I, edited by Keizer, Evelien and Gerry Wanders, Special issue of Web Papers in Functional Discourse Grammar 82, 97–115.Search in Google Scholar

Dall’Aglio Hattnher, Marize Mattos, and Kees Hengeveld. 2016. “The grammaticalization of modal verbs in Brazilian Portuguese: A synchronic approach.” Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 15(1), 1–14. 10.5334/jpl.1.Search in Google Scholar

Davies, Mark. 2004. BYU-BNC. (Based on the British National Corpus from Oxford University Press). <http://corpus.byu.edu/bnc/>.Search in Google Scholar

Dik, Simon C. 1997. The Theory of Functional Grammar. Part II: Complex and Derived Constructions, edited by Hengeveld, Kees. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110218374Search in Google Scholar

Ernst, Thomas. 2002. The Syntax of Adjuncts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

García Verlasco, Daniel. 2013. “Degree words in English: A Functional Discourse Grammar account.” Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses 67, 79–96.Search in Google Scholar

Giomi, Riccardo. 2017. “The interaction of components in a Functional Discourse Grammar account of grammaticalization.” In The Grammaticalization of Tense, Aspect, Modality, and Evidentiality: A Functional Perspective, edited by Hengeveld, Kees, Heiko Narrog and Hella Olbertz, p. 39–74. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. 10.1515/9783110519389-003.Search in Google Scholar

Giomi, Riccardo. 2020. Shifting Structures, Contexts and Meanings: A Functional Discourse Grammar Account of Grammaticalization. PhD dissertation. Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Lisboa.Search in Google Scholar

Haumann, Dagmar. 2007. Adverb Licensing and Clause Structure in English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.105Search in Google Scholar

Hengeveld, Kees. 1989. “Layers and operators in Functional Grammar.” Journal of Linguistics 25(1), 127–57.10.1515/9783110901191.1Search in Google Scholar

Hengeveld, Kees. 1997. “Adverbs in Functional Grammar.” In Toward a Functional Lexicology, edited by Wotjak, Gerd, p. 126–36. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Hengeveld, Kees. 2011. “The grammaticalization of tense and aspect.” In The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization, edited by Heine, Bernd and Heiko Narrog, p. 580–94. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199586783.013.0047Search in Google Scholar

Hengeveld, Kees. 2017. “A hierarchical approach to grammaticalization.” The Grammaticalization of Tense, Aspect, Modality, and Evidentiality: A Functional Perspective, edited by Hengeveld, Kees, Heiko Narrog and Hella Olbertz, p. 13–37. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110519389-002Search in Google Scholar

Hengeveld, Kees and J. Lachlan Mackenzie. 2008. Functional Discourse Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199278107.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Hengeveld, Kees and J. Lachlan Mackenzie. 2014. “Grammar and context in Functional Discourse Grammar.” Pragmatics 24(2), 203–227. 10.1075/prag.24.2.02hen.Search in Google Scholar

Ifantidou, Elly. 1993. “Sentential adverbs and relevance.” Lingua 90(1–2), 69–90.10.1016/0024-3841(93)90061-ZSearch in Google Scholar

Jackendoff, Ray S. 1972. Semantic Interpretation in Generative Grammar. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Keizer, Evelien 2007. “The grammatical-lexical dichotomy in Functional Discourse Grammar.” Alfa – Revista de Lingüística 51(2), 35–56.Search in Google Scholar

Keizer, Evelien 2015. A Functional Discourse Grammar for English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Keizer, Evelien. 2018a. “Interpersonal adverbs in FDG: The case of frankly.” In Recent Developments in Functional Discourse Grammar, edited by Keizer, Evelien and Hella Olbertz, p. 48–88. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 10.1075/slcs.205.03kei.Search in Google Scholar

Keizer, Evelien 2018b. “Modal modifiers in FDG: Putting the theory to the test.” Open Linguistics 4, 356–90. 10.1515/opli-2018-0019.Search in Google Scholar

Keizer, Evelien 2019. “The problem of non-truth-conditional, lower-level modifiers: A Functional Discourse Grammar solution.” English Language and Linguistics 24(2), 365–92. 10.1017/S136067431900011X. Search in Google Scholar

Keizer, Evelien 2020. “Modelling stance adverbs in grammatical theory: Tackling heterogeneity with Functional Discourse Grammar.” Language Sciences 82, 101273. 10.1016/j.langsci.2020.101273.Search in Google Scholar

Keizer, Evelien. 2022. “Premodification in X-is constructions: Fact and point.” In English Noun Phrases from a Functional-Cognitive Perspective: Current Issues, edited by Sommerer, Lotte and Evelien Keizer, p. 235–75. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.221.07keiSearch in Google Scholar

Keizer, Evelien and Hella Olbertz. 2018. “Functional Discourse Grammar: A brief outline.” In Recent Developments in Functional Discourse Grammar, edited by Keizer, Evelien and Hella Olbertz, p. 1–15. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 10.1075/slcs.205.01kei.Search in Google Scholar

Kemp, Lois. 2018. “English evidential -ly adverbs in main clauses: A functional approach.” Open Linguistics 4, 743–61. 10.1515/opli-2018-0036.Search in Google Scholar

Laenzlinger, Christopher. 2004. “The feature-based theory of adverb syntax.” In Adverbials: The Interaction between Meaning, Context and Syntactic Structure, edited by Austin, Jennifer R., Stefan Engelberg and Gisa Rauh, p. 205–52. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 10.1075/la.70.08lae.Search in Google Scholar

Laenzlinger, Christopher. 2015. “Comparative adverb syntax: A cartographic approach.” In Adverbs: Functional and Diachronic Aspects, edited by Pittner, Karin, Daniela Elsner and Fabian Barteld, p. 207–38. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.170.09laeSearch in Google Scholar

Lyons, John. 1977. Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Mackenzie, J. Lachlan. 2013. “The family of secondary predications in English: An FDG view.” Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses 67, 43–58.Search in Google Scholar

Olbertz, Hella and Wim Honselaar. 2017. “The grammaticalization of Dutch moeten: Modal and post-modal meanings.” In The Grammaticalization of Tense, Aspect, Modality, and Evidentiality: A Functional Perspective, edited by Hengeveld, Kees, Heiko Narrog and Hella Olbertz, p. 273–300. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. 10.1515/9783110519389-011.Search in Google Scholar

Rouchota, Villy. 1998. “Procedural meaning and parenthetical discourse markers.” In Discourse Markers: Descriptions and Theory, edited by Juncker, Andreas and Yael Ziv, p. 97–126. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/pbns.57.07rouSearch in Google Scholar

Seinhorst, Klaas and Sterre Leufkens. 2021. “Phonology and phonetics in Functional Discourse Grammar: Interfaces, mismatches, and the direction of processing.” In Interfaces in Functional Discourse Grammar: Theory and Applications, edited by Contreras García, Lucía and Daniel García Velasco, p. 101–26. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. 10.1515/9783110711592-004.Search in Google Scholar

Ten Wolde, Elnora. 2018. “Premodification in evaluative of-binominal noun phrases: An FDG vs a zone-based account.” In Recent Developments in Functional Discourse Grammar, edited by Keizer, Evelien and Hella Olbertz, p. 170–206. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 10.1075/slcs.205.06ten.Search in Google Scholar

Ten Wolde, Elnora. 2021. “A Functional Discourse Grammar account of postnominal modification in English.” In Interfaces in Functional Discourse Grammar: Theory and Applications, edited by Contreras García, Lucía and Daniel García Velasco, p. 369–98. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. 10.1515/9783110711592-011.Search in Google Scholar

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs 1995. “Subjectification in grammaticalization.” In Subjectivity and Subjectivisation, edited by Stein, Dieter and Susan Wright, p. 31–54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511554469.003.Search in Google Scholar

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs and Richard B. Dasher. 2002. Regularity in Semantic Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486500Search in Google Scholar

Van de Velde, Freek. 2007. “Interpersonal modification in the English noun phrase.” Functions of Language 14(2), 203–30.10.1075/fol.14.2.05vanSearch in Google Scholar

Van de Velde, Freek. 2009. “The emergence of modification patterns in the Dutch noun phrase.” Linguistics 47(4), 1021–49.10.1515/LING.2009.036Search in Google Scholar

Van de Velde, Freek. 2011. “A structural-functional account of NP-internal mood.” Lingua 122(1), 1–23.10.1016/j.lingua.2011.10.007Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Evelien Keizer et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A perceptual study of language chunking in Estonian

- Metaphors of cancer in the Arabic language: An analysis of the use of metaphors in the online narratives of breast cancer patients

- A comparative corpus stylistic analysis of thematization and characterization in Gordimer’s My Son’s Story and Coetzee’s Disgrace

- On explaining stable dialect features: A real- and apparent-time study on the variable (en) in Austrian base dialects

- Between exonormative traditions and local acceptance: A corpus-linguistic study of modals of obligation and spatial prepositions in spoken Ugandan English

- When estar is not there: A cross-linguistic analysis of individual/stage-level copular sentences in Romance

- Acquisition of referentiality in elicited narratives of Estonian-speaking children

- Breaking the silence: A corpus-assisted analysis of narratives of the victims of an Egyptian sexual predator

- “Establish a niche” via negation: A corpus-based study of negation within the Move 2 sections of PhD thesis introductions

- Implicit displays of emotional vulnerability: A cross-cultural analysis of “unacceptable” embarrassment-related emotions in the communication within male groups

- Reconstruction of Ryukyuan tone classes of Middle Japanese Class 2.4 and 2.5 nouns

- The Communication of Viewpoints in Jordanian Arabic: A Pragmatic Study

- Productive vocabulary learning in pre-primary education through soft CLIL

- NMT verb rendering: A cognitive approach to informing Arabic-into-English post-editing

- Ideophones in Arusa Maasai: Syntax, morphology, and phonetics

- When teaching works and time helps: Noun modification in L2 English school children

- A pragmatic analysis of Shylock’s use of thou and you

- Linguistic repercussions of COVID-19: A corpus study on four languages

- Special Issue: Translation Times, edited by Titela Vîlceanu and Daniel Dejica

- Editorial

- Deviant language in the literary dialogue: An English–Romanian translational view

- Transferring knowledge to/from the market – still building the polysystem? The translation of Australian fiction in Romania

- “‘Peewit,’ said a peewit, very remote.” – Notes on quotatives in literary translation

- Equivalence and (un)translatability: Instances of the transfer between Romanian and English

- Categorizing and translating abbreviations and acronyms

- “Buoyantly, nippily, testily” – Remarks on translating manner adverbs into Romanian

- Performativity of remixed poetry. Computational translations and Digital Humanities

- Ophelia, more or less. Intersemiotic reinterpretations of a Shakespearean character

- Considerations on the meaning and translation of English heart idioms. Integrating the cognitive linguistic approach

- New trends in translation and interpreting studies: Linguistic accessibility in Romania

- Special Issue: Modification in Functional Discourse Grammar, edited by Thomas Schwaiger, Elnora ten Wolde, and Evelien Keizer

- Modification in Functional Discourse Grammar: State of the art and issues addressed

- Modification and context

- Modifier-numeral word order in the English NP: An FDG analysis

- English evidential -ly adverbs in the noun phrase from a functional perspective

- Variation in the prosody of illocutionary adverbs

- “It’s way too intriguing!” The fuzzy status of emergent intensifiers: A Functional Discourse Grammar account

- Similatives are Manners, comparatives are Quantities (except when they aren’t)

- Insubordinate if-clauses in FDG: Degrees of independence

- Modification as a linguistic ‘relationship’: A just so problem in Functional Discourse Grammar

- American Spanish dizque from a Functional Discourse Grammar perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A perceptual study of language chunking in Estonian

- Metaphors of cancer in the Arabic language: An analysis of the use of metaphors in the online narratives of breast cancer patients

- A comparative corpus stylistic analysis of thematization and characterization in Gordimer’s My Son’s Story and Coetzee’s Disgrace

- On explaining stable dialect features: A real- and apparent-time study on the variable (en) in Austrian base dialects

- Between exonormative traditions and local acceptance: A corpus-linguistic study of modals of obligation and spatial prepositions in spoken Ugandan English

- When estar is not there: A cross-linguistic analysis of individual/stage-level copular sentences in Romance

- Acquisition of referentiality in elicited narratives of Estonian-speaking children

- Breaking the silence: A corpus-assisted analysis of narratives of the victims of an Egyptian sexual predator

- “Establish a niche” via negation: A corpus-based study of negation within the Move 2 sections of PhD thesis introductions

- Implicit displays of emotional vulnerability: A cross-cultural analysis of “unacceptable” embarrassment-related emotions in the communication within male groups

- Reconstruction of Ryukyuan tone classes of Middle Japanese Class 2.4 and 2.5 nouns

- The Communication of Viewpoints in Jordanian Arabic: A Pragmatic Study

- Productive vocabulary learning in pre-primary education through soft CLIL

- NMT verb rendering: A cognitive approach to informing Arabic-into-English post-editing

- Ideophones in Arusa Maasai: Syntax, morphology, and phonetics

- When teaching works and time helps: Noun modification in L2 English school children

- A pragmatic analysis of Shylock’s use of thou and you

- Linguistic repercussions of COVID-19: A corpus study on four languages

- Special Issue: Translation Times, edited by Titela Vîlceanu and Daniel Dejica

- Editorial

- Deviant language in the literary dialogue: An English–Romanian translational view

- Transferring knowledge to/from the market – still building the polysystem? The translation of Australian fiction in Romania

- “‘Peewit,’ said a peewit, very remote.” – Notes on quotatives in literary translation

- Equivalence and (un)translatability: Instances of the transfer between Romanian and English

- Categorizing and translating abbreviations and acronyms

- “Buoyantly, nippily, testily” – Remarks on translating manner adverbs into Romanian

- Performativity of remixed poetry. Computational translations and Digital Humanities

- Ophelia, more or less. Intersemiotic reinterpretations of a Shakespearean character

- Considerations on the meaning and translation of English heart idioms. Integrating the cognitive linguistic approach

- New trends in translation and interpreting studies: Linguistic accessibility in Romania

- Special Issue: Modification in Functional Discourse Grammar, edited by Thomas Schwaiger, Elnora ten Wolde, and Evelien Keizer

- Modification in Functional Discourse Grammar: State of the art and issues addressed

- Modification and context

- Modifier-numeral word order in the English NP: An FDG analysis

- English evidential -ly adverbs in the noun phrase from a functional perspective

- Variation in the prosody of illocutionary adverbs

- “It’s way too intriguing!” The fuzzy status of emergent intensifiers: A Functional Discourse Grammar account

- Similatives are Manners, comparatives are Quantities (except when they aren’t)

- Insubordinate if-clauses in FDG: Degrees of independence

- Modification as a linguistic ‘relationship’: A just so problem in Functional Discourse Grammar

- American Spanish dizque from a Functional Discourse Grammar perspective