Abstract

Malware has become one of the biggest risks to security due to its rapid expansion. Therefore, it must be quickly detected and removed. While convolutional neural network (CNN) models have expanded to include ensemble and transfer learning approach from previous individual CNN architectures, relatively few studies have compared how well these approaches perform when it comes to malware family detection. A small number of malware varieties have been the focus of several research efforts’ studies. In this study, both of these issues were resolved. We present our own ensemble model for the classification of malware diseases into 34 types. We merge the Microsoft malware dataset with the Malimg dataset to increase the number of malware families identified by the model. To reduce training time and resource consumption, the suggested model utilized the most significant malware features, which are chosen based on the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator method, for the purpose of classifying the malware classes. The experimental findings demonstrate that the ensemble model’s accuracy is 99.78%. Based on the experimental results, we conclude that the model will help with real-world malware classification tasks.

1 Introduction

Malware has become one of the most significant threats to network security because it can damage computer systems without the users’ permission (Sharif, Jiwani, Gupta, Mohammed, & Ansari, 2023). From stealing personal information to violating the nation’s and countries’ legitimate rights and interests, criminals commit a range of criminal crimes (Alzahrani, 2023; Zhao, Zhao, Yang, & Xu, 2023). Globally, the number of malware files discovered daily has increased by 5.2% from the average of 360,000 files detected daily in 2020 (Awan et al., 2021a,b).

Based on a 2018 Microsoft Security and Intelligence report, Ethiopia has the top average monthly ransomware encounter rates, followed by Mongolia, Cameroon, Myanmar, and Venezuela. Each of these countries had an average monthly ransomware encounter rate of at least 31% (Diana et al., 2018). Ethiopia’s Information Network Security Agency reported on May 3, 2022, that the country had prevented more than 5,856 cyber-attacks by the time (Ethiopia Situation Report, 2022) and 6,768 attempts were made to carry out cyber-attacks in 2023.

In Africa, the brand anniversary scam is a well-known phishing scheme. Threat actors pose as well-known companies, like Ethiopian Airlines and Ethio Telecom, to persuade unaware individuals into filling out a quick survey or questionnaire in exchange for a free gift. After entering their information, a person must forward the message to 20 friends or 5 WhatsApp groups to be eligible for a reward. Regretfully, those who unintentionally agree with these scammers’ requests will actually offer them with an opportunity to obtain personal information and even device information (INTERPOL, 2023).

Because malware attacks are becoming more frequent, a highly efficient method of malware detection is necessary. Numerous methods have been used for malware detection over the years. These vary from thorough manual labelling to complex hybrid systems (Mohammed, Ibrahim, & Salman, 2021). When it comes to analyzing malware, anti-malware software uses association rule mining, data mining, and information retrieval and extraction techniques. However, using these approaches has led to a sharp increase in the advent of new malware.

Static and dynamic analysis are the most popular techniques and often used methods for classifying malware. The majority of the metadata is extracted from malware binaries via static analysis, which does so without running or launching the files. Without actually executing harmful code, it enables you to recognize malware signatures. However, malware that uses polymorphism or obfuscation packaging can be extremely challenging to analyses using this technique (Djenna, Bouridane, Rubab, & Marou, 2023).

To gather information on malware behavior and its effects on the system in real time, dynamic analysis is performed by watching how the malware behaves while it is being executed. Although dynamic analysis has significant drawbacks, such as the fact that installing it would require a lengthy time to analyze the executable, it is believed to be more dependable and efficient in the long run. Dynamic analysis is always better than static analysis because, although malware may vary in structure, its behavior and other characteristics will never alter. This makes malware detection easier with dynamic analysis (Djenna et al., 2023), but these methods are feature-heavy or demand a high level of domain expertise to construct the features. This presents a challenge because malware develops at a rapid pace and this approach is unable to keep up. Still, most well-known anti-malware programs also implement a signature-based approach, which involves building a local database and storing the malware’s signature patterns (Jung, Bae, Choi, & Im, 2020). Additionally, the adoption of quantum cryptography has the potential to foster the development of highly secure communication channels. This advancement could prove invaluable in combating malicious software and facilitating the transmission of sensitive information (Canto, Sarker, Kaur, Kermani, & Azarderakhsh, 2022; Canto, Kermani, & Azarderakhsh, 2021; Kaur, Canto, Kermani, & Azarderakhsh, 2023; Kermani, Bayat-Sarmadi, Ackie, & Azarderakhsh, 2019).

In the past few years, deep learning (DL) and machine learning (ML) have shown promise in the fields of cybersecurity analytics, malware detection, cyberattack mitigation, botnet identification, malware classification, intrusion detection, prevention, incident response, network traffic analysis, cybercriminal identification, and deep packet inspection. This study aims to implement an ensemble of different neural networks for the detection of malware. The following are the paper’s significant contributions:

A novel hybrid classification model for malware detection based on ensemble learning of three models, which enables us to improve malware detection accuracy.

Using the support vector machine (SVM) classifier in conjunction with the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) algorithm as a feature selection strategy, which chooses the fewest features necessary to enhance the classification performance of an image-based malware detection system.

A new dataset was produced for the detailed experimental investigation of DL approaches for multivariate malware detection through the merging of two open-access datasets (the Microsoft malware dataset and the Malimg dataset).

The following is the format of the remaining sections of this study: a sufficient comparison of current techniques and approaches is included in Section 2, along with a discussion of related studies. The methodology employed in this article is explained in Section 3. Results are discussed in Section 4. The research conclusions are presented in Section 5.

2 Related Work

In this study, we examine current malware detection techniques, such as static, dynamic, and visualization analyses, based on DL and ML methods.

Statistical analysis (Krumbach & White, 1964) uses data mining techniques including information gain, principal component analysis based on SVM, J48, and Naïve Bayes classifiers. They extract DLLs, application program interface methods contained in each DLL of a Windows PE file, and PE header information from Windows executables. Principal component analysis is used to reduce the dimensionality of the selected features after information gain and calling frequencies of the raw features are determined to identify valuable subset features. Their system achieves a 99.6% detection rate. Shabtai, Moskovitch, Feher, Dolev, and Elovici (2012) investigated Opcodes using various classifiers and n-grame sizes. According to their claims, the 2-gram Opcode approach performed better than the byte-n-gram methods. Using neural network technology, Saxe and Berlin (2015) created a method to differentiate between malware and benignware. The entropy histogram from binary data, the executed files metadata, and DLL import were computed using four different kinds of features that they collected. These characteristics were converted to vectors of 256 dimensions. They discovered that the FPR was 0.1% and the TRP was 95.2%; nevertheless, their methodology necessitated feature engineering tools. The created method’s accuracy is not sufficient, and neither is it clear how accurate the features of the malware and benign samples are.

Using dynamic analysis, Lim and Moon (2015) created a malware identification technique by analyzing network traffic behavior. They compared character sequences to identify similarities using sequence alignment and flow feature clustering. Lim and Moon (2015) used a hidden Markov model for malware classification, relying on system calls as observed symbols.

To overcome malware family classification challenges, researchers have employed visualization techniques that minimize feature engineering costs and domain-specific knowledge. For instance, Sharif et al. (2023) used convolutional neural network (CNN), Caps-Net, VGG16, ResNet, and InceptionV3 DL algorithms with respect to an image-based malware dataset called Malimg to detect malware. With early stopping conditions, the models were trained up to epoch 50 and were 92% accurate in diagnosing malware. Twenty-five different malware types are categorized using their model. Saridou, Moulas, Shiaeles, and Papadopoulos (2023) used binary visualization on both benign and malicious files to detect malware to build a ResNet50 model. A 93.60% accuracy, 94.48% precision, 92.60% recall, and a 93.53% f-score are attained by their model. AlexNet CNN serves as the foundation for a unique malware detection technique proposed by Zhao et al. (2023). The experimental findings demonstrate that the GCJ dataset has an accuracy of 99.38% and the Microsoft malware dataset has an accuracy of 99.99%. To identify malicious executables, Alzahrani (2023) suggests a stacking-based ensemble strategy that combines CNN, LSTM, and GRU models. The experiment’s findings show that a 99.02% accuracy rate was attained. Awan et al. (2021a,b) present a DL framework based on spatial attention and CNNs for image-based malware classification of 25 popular malware families with and without class balancing. Accuracy, recall, specificity, precision, and the F1 score were used to assess performance on the Malimg benchmark dataset. They found that their proposed class-balanced model achieved 97.68, 97.95, 97.33, 97.11, and 97.32%. Salota and Singh (2023) used modified VGG based on an image-based malware dataset for malware identification. The proposed model has a 99% accuracy rate for correctly identifying malware. In Altaiy, Yildiz, and Bahadır (2023), The Long-Short-Term Memory Network, CNN, and Multitasking Deep Neural Network are the three DL techniques applied in this study. The most successful outcomes of this investigation showed that DNN has an accuracy of 0.982, a precision of 0.988, and a recall of 0.990. Shaukat, Luo, and Varadharajan (2023) suggested an approach that eliminates the necessity for complex feature engineering activities and domain expertise by combining DL and support vector ML. On the Malimg dataset, the suggested method performed better, with an accuracy of 99.06%. The work by Chen, Xing, and Ren (2023) suggests a method for classifying and identifying malware that utilizes bicubic interpolation to enhance the security of plant protection information terminal systems. According to experimental findings, the method can greatly increase the effectiveness of malware categorization. The Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge Dataset (BIG2015) can produce RGB and grey images with an accuracy of 99.76 and 99.62%, respectively. Abhinav, Akshay, Anshad, Mohan, and Usha (2023) demonstrated how effective ensemble learning is at identifying malware, particularly when combining the VGG-16 and Efficient Net models. The study found that the combination of these models achieved an overall accuracy of 96.8%. To successfully and precisely classify malware, Yadav and Tokekar (2023) make use of visualization and suggest a CNN-based DL model. The proposed model achieves 98.179, 97.39, and 97.70% for accuracy, precision, and F1-score, respectively, and with a classification speed of 3 s needed to test 934 unknown malware. Nguyen, Di Troia, Ishigaki, and Stamp (2023) use a variety of techniques to extract features from malware executable files and represent them as images. Next, they concentrate on multiclass classification using generative adversarial networks (GAN) and assess how well their GAN findings compare to those of other well-liked ML methods such as SVM, XGBoost, and RBM. Aurangzeb and Aleem (2023) offer a fast, scalable, and precise DL method for detecting obfuscated Android malware on both real and emulator-based systems. Experiments demonstrate that the suggested approach reliably and successfully detects malware, as well as features that are typically hidden by malicious software. Panda, CU, Marappan, Ma, and Veesani Nandi (2023) proposed a novel ensemble model called Stacked Ensemble Auto Encoder, GRU, and MLP, or SE-AGM, that is trained on the 25 key extracted features that are encoded from the benchmark Malimg dataset to facilitate classification. The SE-AGM achieved an average accuracy of 99.43%.

3 Methodology

3.1 Malware Datasets

In this study, we used two datasets: The Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge (BIG2015) dataset (https://www.kaggle.com/c/malware-classification/), which contains 10,868 labelled malware samples from 9 families, and the Malimg dataset (Nataraj, Karthikeyan, Jacob, & Manjunath, 2011), which consists primarily of 9,458 malware samples that have been classified into 25 different classes. Malimg typically consists of images, and the samples just need to be resized and augmented; in contrast, the Microsoft dataset has already undergone preprocessing and is ready for use right away, as Table 1 illustrates.

Number of samples for each malware family in both datasets before and after augmentation

| No. | Malware family name | No. of samples before augmentation | Augmentation | No. of samples after augmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Allaple.L | 1,591 | No | 1,591 |

| 2 | Allaple.A | 2,949 | No | 2,949 |

| 3 | Yuner.A | 800 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 4 | Lolyda.AA 1 | 213 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 5 | Lolyda.AA 2 | 184 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 6 | Lolyda.AA 3 | 123 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 7 | C2Lop.P | 146 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 8 | C2Lop.gen!G | 200 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 9 | Instantaccess | 431 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 10 | Swizzor.gen!I | 132 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 11 | Swizzor.gen!E | 128 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 12 | VB.AT | 408 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 13 | Fakerean | 381 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 14 | Alueron.gen!J | 198 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 15 | Malex.gen!J | 136 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 16 | Lolyda.AT | 159 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 17 | Adialer.C | 125 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 18 | Wintrim.BX | 97 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 19 | Dialplatform.B | 177 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 20 | Dontovo.A | 162 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 21 | Obfuscator.AD | 142 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 22 | Agent.FYI | 116 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 23 | Autorun.K | 106 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 24 | Rbot!gen | 158 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 25 | Skintrim.N | 80 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 26 | Ramnit | 1,541 | No | 1,541 |

| 27 | Lollipop | 2,478 | No | 2,478 |

| 28 | Kelihos_Ver3 | 2,942 | No | 2,942 |

| 29 | Vundo | 475 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 30 | Simda | 42 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 31 | Tracur | 751 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 32 | Kelihos_Ver1 | 398 | Yes | 1,000 |

| 33 | Obfuscator.ACY | 1,228 | No | 1,228 |

| 34 | Gatak | 1,013 | No | 1,013 |

| Total no. of images 20,326 | Total no. of images 39,742 |

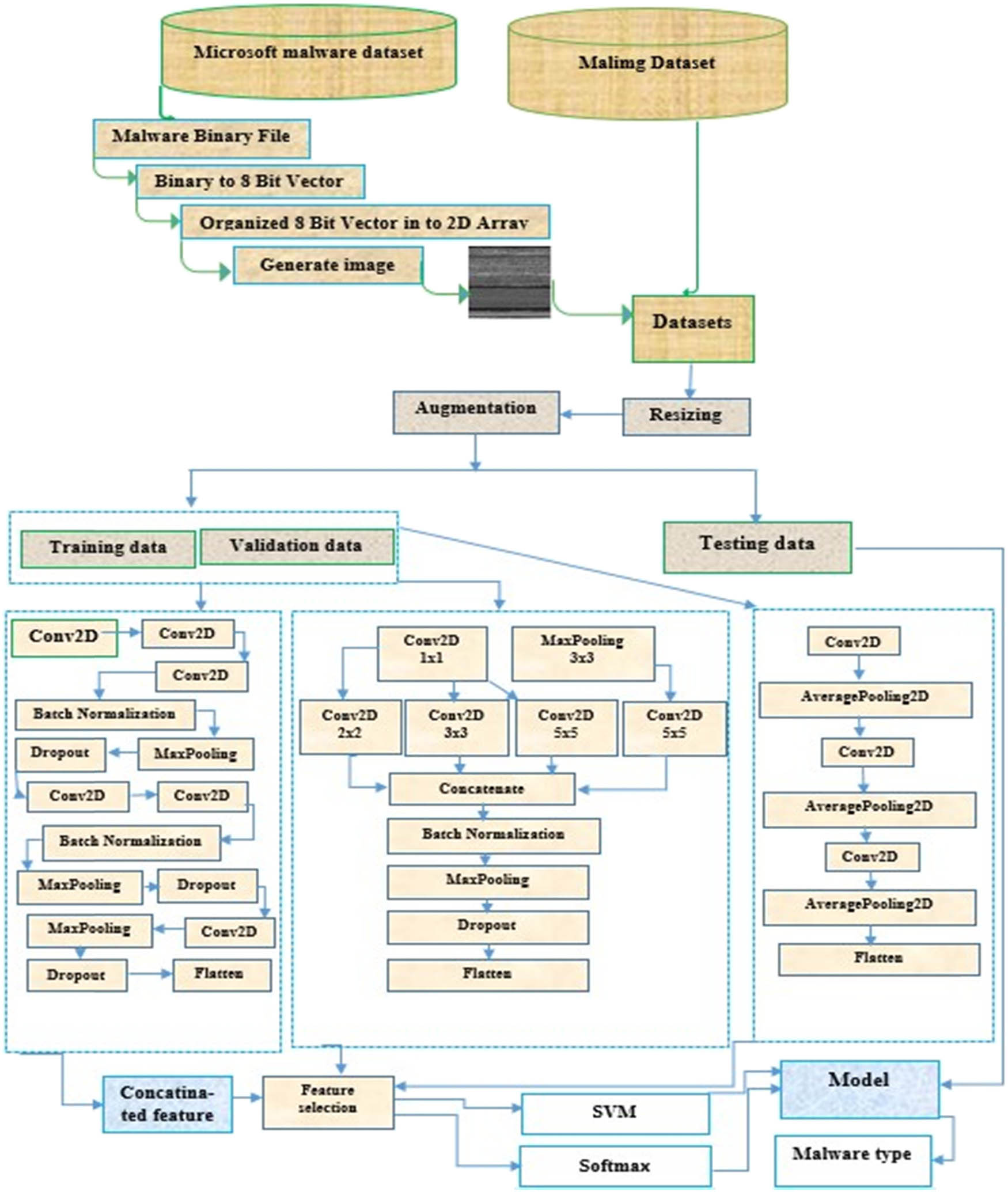

3.2 Overview of the Proposed Ensemble Model

Using concatenated deep features collected from malware images of three different models (the CNN architecture of VGGNet, AlexNet, and InceptionNet), our model aims to accurately diagnose malware families. Figure 1 shows the proposed concatenated model architecture. First, the input images are diminished to 32 × 32 to minimize resource and computational time. Second, we used the technique called augmentation to only the classes containing images less than 1,000 to make it possible for the trained model to extract a substantial amount of useful features. We apply different augmentation methods such as rotation of 45°, random vertical and horizontal flips, and random vertical and horizontal shifts. A total of 20,326 images made up the whole malware image dataset prior to augmentation, while 39,742 images exist after augmentation. The dataset was subdivided into three groups: The training set accounted for 70% of the dataset, the validation set for 10%, and the test set for 20%, both before and after augmentation. The model is trained through the execution of the training and validation phases prior to the testing phase. To evaluate how well the trained model performs with the new image dataset, the testing phase is carried out following the training and validation. Third, the most important features from the images are extracted using the concatenated model of the CNN models’ architecture. The features derived from the previous models are then integrated into a single classification descriptor.

Architecture of the proposed model.

To expose the extracted features of VGGNet, AlexNet, and InceptionNet to the LASSO feature selection algorithm, the features are lastly concatenated. The most significant features chosen by LASSO are then fed into the classifiers (Softmax and SVM) to determine which ones are the best. Both model features (VGGNet, AlexNet, and InceptionNet) are concatenated and fed to the previously trained Softmax and SVM models within the test set.

The models were trained for 70 epochs using early halting criteria. All trained models’ outcomes were compared with the support of the assessment measures. Accuracy and loss function are used to evaluate the concatenated model. We employed a categorical cross-entropy loss function, which is frequently used for multi-class problems to quantify the difference between the output predictions and the target output. To advance the model’s accuracy and decrease the loss, the learning rate and other parameters have been adjusted using an adaptive momentum estimation (Adam) optimization function, with a learning rate of 0.001. Finally, the model classification performance is computed using performance metrics.

We used the CNN models listed below, each of which has different capabilities.

3.2.1 VGG 16

It achieves 92.7% top-5 test accuracy on the 14 million images in the ImageNet dataset comprising more than 1,000 classes (Simonyan & Zisserman, 2014). It contains 16 layers requiring to be trained, 5 convolutional blocks, and 3 fully connected layers, and its architecture is shown in Figure 2. To provide the same spatial dimension for every activation map as the previous layer, the convolutional layers employed 3 × 3 kernels with 1 padding and 1 stride as their filter size. Rectified linear unit (ReLU) nonlinearity was introduced to every convolutional layer to speed up training and reduce the chance of vanishing gradient issues. A max-pooling step was also employed at each block end to reduce spatial dimensions. In max-pooling layers, a 2 × 2 kernel filter with no padding and two strides was employed to ensure that the spatial dimensions of the activation map were cut in half as compared to the previous layer. The final 1,000 fully linked Softmax layer was applied after the first two fully connected layers with 4096 ReLU-activated units were used. In this study, we used six convolution layers, two batch normalizations, three MaxPoolings, three dropout layers, and a flattening layer at the end, as presented in Figure 1.

VGG-16 architecture (Simonyan & Zisserman, 2014).

3.2.2 Inception v3

According to He, Zhang, Ren, and Sun (2015), Inception has a significantly reduced computational cost compared to VGGNet or its more successful successors. Its architecture is presented in Figure 3. The primary goal of Inception v3 is to reduce processing power consumption by making changes to the earlier Inception designs (Szegedy, Vanhoucke, Ioffe, Shlens, & Wojna, 2016). As illustrated in Figure 1, we employed an architecture consisting of five convolution layers, one batch normalization, two MaxPoolings, one dropout layer, and a flattening layer at the end.

Inception V3 architecture (Szegedy et al., 2016).

3.2.3 AlexNet

Eight layers make up the architecture: three fully connected layers and five convolutional layers. Its architecture is shown in Figure 4. At 15.3% for top-5 error rate, AlexNet became the winner in the 2012 ImageNet competition. Because the AlexNet model extracts Deep features from its layers within a short period of time, it was selected (Krizhevsky, Sutskever, & Hinton, 2012). Figure 1 illustrates an architecture we employed, which included two AveragePoolings, three convolution layers, and a flattening layer at the end.

The Architecture of AlexNet (Krizhevsky et al., 2012).

This model was chosen due to their excellent performance in several malware picture classification settings. We used two different classifier types and a feature selection approach in our ensemble model: Feature selection: in ML, feature selection is an essential step that selects the optimal attributes to decrease system training time, increase accuracy, and lower problems with overfitting (Cai, Luo, Wang, & Yang, 2018). This study selected important features from each model’s Deep features using the LASSO algorithms (Tibshirani, 1996) to accurately detect each malware among other malware families. The LASSO adjusts the linear regression’s cost function by incorporating a regularization parameter (λ) that penalizes the whole sum of all coefficients to reduce the mean square error, as expressed by the following equation (Tibshirani, 1996, 2011):

where λ is a nonnegative regularization parameter, and βj is a coefficient vector of length m. To minimize the value of the cost function, the absolute values of the weights would need to drop (shrink) as the regularization strength increased. Consequently, the features of the less important weights are eliminated from the subset and their weights become zero as a result of the LASSO. Consequently, LASSO regression offers the noteworthy benefit of carrying out an automated feature selection process. The shrinkage regulating factor, lambda (λ), is largely relied upon by the LASSO. When λ equals 0, all features are taken into account. When λ grows, fewer features are chosen; when λ gets closer to infinity, all features are eliminated from the subset. Let us say that a group of features has a high correlation with one another. Then, since their existence will increase the value of the cost function, LASSO chooses one of them and reduces the coefficient of the remaining ones to zero to choose the optimal feature subset (Tibshirani, 1996, 2011; Wang, Li, & Tsai, 2007). To train and evaluate the two key classifiers for malware family detection, the most significant features derived from the LASSO technique were utilized. The first is the supervised learning technique called Softmax classifier, which is typically applied when there are several classes involved (Ren, Zhao, Sheng, Yao, & Xu, 2017). The second is Multiclass SVMs (Williams, 2003), a well-known and efficient multi-label classification algorithm (Tan, Tan, Jiang, & Zhou, 2020).

3.3 Experimental Setup

We used the Python programming language, the Anaconda environment, the free-source CNN library Tensor Flow as the backend, and the Keras software. Jupiter Notebook was utilized to write the Python code. The proposed model was constructed in the Google Colab environment. For training, we utilized a 12-GB GPU NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 Ti, and we tested the developed model on a hardware-based, 64-bit Windows 10 HP Pavilion laptop with Intel (R) Core (TM) i38145UMQ, which has a 2.30 GHz CPU, 8 GB of RAM, and a 700 GB test hard drive.

3.4 Performance Measures

The models’ performance on the test sets will be assessed using the F1-score, test accuracy, precision, and recall metrics. The equations for each metric are illustrated in Table 2.

Equations of performance metrics (Sanderson, 2010)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Precision, recall, and F1 score are computed for each class separately in multiclass predictions, frequently treating that class as the “positive” class and the other classes as the “negative” classes. A weighted average is then typically taken into account for all classes to offer a single metric. To ensure that performance in smaller classes will have an equal impact on the final score as greater ones, we used macro-average recall, precision, and F1 score in our study. This allowed us to treat all classes equally by averaging the metrics for each class without taking into account their size.

3.5 Transfer Learning

To reduce the time needed to train models, transfer learning is the act of moving the parameters of a neural network trained with one dataset and task to adapt to another problem with a different dataset and task (Torrey & Shavlik, 2010). In our context, fine-tuning the models for malware classification may not have a substantial effect on their performance because our datasets are smaller and models trained on the ImageNet dataset learn features that are entirely different from malware image features. To obtain malware image features, we used VGG16, Inception V3, and Alex Net base models that had previously been trained on ImageNet (Simonyan & Zisserman, 2014) by freezing their layers and utilizing a fully connected layer that contained 34 classes, or 34 malware families. These features were then used as input in training SVM classifiers.

4 Experimental Results and Discussion

4.1 Results

The proposed ensemble model achieved 99.99 training accuracy, 99.98% validation accuracy, and 99.78% testing accuracy in malware category classification under the described experimental conditions. The classification accuracy of other baseline CNNs and the proposed ensemble model are presented in Table 3.

Classification accuracy of each model and the proposed ensemble model

| Ex. no. | Model | Feature selection and classifier | Test accuracy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | VGGNet | Feature selection: no | Classifier: Softmax | 85 |

| Classifier: SVM | 86 | |||

| Feature selection: LASSO | Classifier: Softmax | 86.5 | ||

| Classifier: SVM | 87.5 | |||

| 2. | Inception V3 | Feature selection: no | Classifier: Softmax | 84.5 |

| Classifier: SVM | 85.5 | |||

| Feature selection: LASSO | Classifier: Softmax | 82 | ||

| Classifier: SVM | 83 | |||

| 3. | Alex Net | Feature selection: no | Classifier: Softmax | 83.5 |

| Classifier: SVM | 84 | |||

| Feature selection: LASSO | Classifier: Softmax | 85 | ||

| Classifier: SVM | 86.5 | |||

| 4. | VGGNet + InceptionV3 + SVM | Feature selection: no | 96 | |

| Feature selection: LASSO | 98 | |||

| 5. | Feature selection: no | 92 | ||

| VGGNet + AlexNet + SVM | Feature selection: LASSO | 93 | ||

| 6. | InceptionV3 + AlexNet + SVM | Feature selection: no | 90 | |

| Feature selection: LASSO | 91 | |||

| 7. | VGGNet + InceptionV3 + AlexNet + SVM | Feature selection: no | 97 | |

| Feature selection: LASSO | 99.78 | |||

Table 3 shows that the developed model outperformed all other models in terms of classification accuracy improvement. The findings of the experiment revealed that the proposed ensemble model was superior in accuracy (99.78%) with LASSO feature selection technique than the models that were used without feature selection algorithms (VGGNet + Softmax [85%], VGGNet + SVM [86%], Inception V3 + Softmax [84.5%], Inception V3 + SVM [85.5%] + AlexNet + Softmax [83.5%], AlexNet + SVM [84%], VGGNet + InceptionV3 + SVM [96%], InceptionV3 + AlexNet + SVM [90%], VGGNet + InceptionV3 + AlexNet + SVM [97%] and VGGNet + Softmax [86.5%], VGGNet + SVM [87.5%], InceptionV3 + Softmax [82%], InceptionV3 + SVM [83%] + Alex-Net + Softmax [85%], AlexNet + SVM [86.5%], VGGNet + InceptionV3 + SVM [98%], VGGNet + AlexNet + SVM [93%], and InceptionV3 + AlexNet + SVM [91%]) with feature selection algorithm.

As demonstrated by Figure 5, a growing trend in both training and validation accuracies shows that the model is both learning from the training data and has good generalization capabilities to new data. The gap between training and validation accuracies does not differ much; it may be a hint that overfitting is not occurring and the model functions well on both sets of data. A consistent and gradual reduction in both training and validation losses signifies the model’s enhancement over time, suggesting that it learns the underlying patterns in the data without overfitting, as observed in Figure 5. In conclusion, Figures 5 and 6 offer essential insights into the model’s learning process from the data and its capability to provide precise predictions on unseen data.

Training and validation accuracy.

Training and validation loss.

Table 4 provides a comprehensive comparison between various malware classification approaches, encompassing both ML and DL techniques, alongside our proposed model. Notably, our suggested model shows superior performance in terms of classifying more malware samples and its accuracy compared to existing approaches. This suggests that our model exhibits enhanced efficacy in identifying and categorizing malware instances. The experimental result shows that the proposed model reveals marvelous result both in performance and efficiency in 34 types of malware identification, this much types of class are not considered by other previous works. Prior to employing feature selection techniques, the model required an average of 2.5 s to categorize a malware sample. However, after implementing the LASSO feature selection technique, this time reduced significantly to 1.15 s. This reduction in processing time signifies the effectiveness of the LASSO feature selection technique in optimizing the model’s performance and streamlining the malware identification process. Overall, the comparison presented in Table 4 emphasizes the superiority of our proposed model in terms of malware classification, supported by empirical evidence of its efficiency and effectiveness in identifying malware samples within minimal processing time.

A comparative summary

| No. | Method | Feature selection | No of class | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | ResNet50 (Saridou et al., 2023) | — | 2 | 93.60 |

| 2. | Alex Net (Zhao et al., 2023) | — | 9 | 99.99 |

| 3. | Spatial Attention CNN with VGG19 (Awan et al., 2021a,b) | — | 25 | 97.68 |

| 4. | VGG16 + ResNet-50 + SVM (Vasan, Alazab, Wassan, Safaei, & Zheng, 2020) | PCA | 25 | 99.5 |

| 5. | DL + SVM (Shaukat et al., 2023) | — | 25 | 99.06 |

| 6. | CNN + Cycle-GAN (Chen et al., 2023) | — | 9 | 99.76 |

| 7. | VGG-16 and Efficient Net | — | 25 | 96.8 |

| 8. | CNN (Yadav & Tokekar, 2023) | — | 25 | 98.179 |

| 9. | SE-AGM (Panda et al., 2023) | — | 25 | 99.43 |

| 10. | Proposed (VGGNet + InceptionV3 + AlexNet + SVM) | LASSO | 34 | 99.78 |

4.2 Discussion

Our findings pointed out that the proposed model that we created is still better than any other baseline available today. We use a group of fine-tuning schemes to identify the exact features in our dataset. All models produced meaningful results using the SVM classifier when the CNN was adjusted using Softmax and SVM classifications. This occurred as a result of Softmax classifier failing to do a one-versus-all comparison when classifying images and malware families that did not exhibit significant differences, whereas one-versus-all multiclass SVMs are capable of differentiating between malware families that exhibit little variation. Because the proposed model incorporates the generalizability of both VGG16, Inception V3, and Alex Net models, it can recognize slight variations among malware types. For this reason, the suggested model’s classification accuracy remained higher than that of the other baseline techniques as shown in Table 3. Because the proposed model incorporates the benefits of several approaches, it was able to correctly categorize images that each of the more specific models had incorrectly classified. The proposed model achieves the best results at epoch 70 after trying a lot of epochs. Because only the most crucial features are chosen by the LASSO algorithm and utilized by the model, the suggested model can identify image samples in a short time.

5 Conclusion

This study presents an effective ensemble DL approach based on the LASSO feature selection algorithm to classify malware families. It attained high accuracy while increasing detected malware varieties. Generally, the accuracy of the proposed ensemble model was 99.78%. This shows the efficiency of the model in extracting Deep features from the 34 malware images and achieving accurate detection of malwares. The experimental outcomes exposed that the LASSO feature selection algorithm improved the approach performance with a few selected Deep features instead of using the total Deep features in the classification process. Moreover, the LASSO algorithm improves the model performance, in reducing number of selected features, and execution time. As well as, the SVM classifier provided high system performance compared with the Softmax classifier. The proposed ensemble DL model resulted in the best results of 99.78% testing accuracy, 99.99% training accuracy, 99.98% validation accuracy, 99.93% precision, 99.67% sensitivity, 99.95% specificity, and 99.87% F1-score. This performance was achieved by extracting Deep features from the combined dataset Malimg dataset and Microsoft malware dataset using VGGNet, Inception V3, and Alex Net model, applying the LASSO feature selection algorithm.

For the future researchers, we recommend the use of different segmentation and noise-filtering techniques that may increase the performance of the model. Additionally, it is recommended the inclusion of an integrated approach that combines malware analysis, post-quantum cryptography, and ML concepts to achieve better accuracy as adopting post-quantum cryptography measures is crucial in ensuring robust security in the face of advancing quantum computing technology to establish resilient encryption methods that can withstand potential quantum-based attacks (Canto, Kermani, & Azarderakhsh, 2022; Cintas-Canto, Kermani, & Azarderakhsh, 2022; Cintas-Canto, Kaur, Mozaffari-Kermani, & Azarderakhsh, 2023; Kermani, 2007; Kermani, Azarderakhsh, & Mirakhorli, 2016; Koziel, Jalali, Azarderakhsh, Jao, & Mozaffari-Kermani, 2016; Mozaffari-Kermani, Azarderakhsh, Ren, & Beuchat, 2016; Niasar, Azarderakhsh, & Kermani, 2020).

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All three authors made substantial contributions to different aspects of this work. Abebech Jenber played a key role in the selection and preparation of the datasets. Melaku Bitew concentrated on the literature review and methodological design, and Dr. Yelkal Mulualem took an active part in the evaluation of the findings and the writing of the conclusion. Melaku Bitew was the supervisor of the research. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article (Nataraj et al., 2011) and the Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge (BIG2015) dataset is available at https://www.kaggle.com/c/malware-classification/.

References

Abhinav, A. D., Akshay, C. P., Anshad, P. V., Mohan, V., & Usha, K. (2023). Malware detection using ensemble learning. India: Irjmets.Suche in Google Scholar

Altaiy, M., Yildiz, İ., & Bahadır, U. Ç. A. N. (2023). Malware detection using deep learning algorithms. AURUM Journal of Engineering Systems and Architecture, 7(1), 11–26.10.53600/ajesa.1321170Suche in Google Scholar

Alzahrani, M. E. (2023). Multi-model deep learning ensemble approach for detection of malicious executables. The Islamic University Journal of Applied Sciences (JESC), 2023(7), 139–153.Suche in Google Scholar

Aurangzeb, S., & Aleem, M. (2023). Evaluation and classification of obfuscated Android malware through deep learning using ensemble voting mechanism. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 3093.10.1038/s41598-023-30028-wSuche in Google Scholar

Awan, M. J., Farooq, U., Babar, H. M. A., Yasin, A., Nobanee, H., Hussain, M., & Zain, A. M. (2021a). Real-time DDoS attack detection system using big data approach. Sustainability, 13(19), 10743.10.3390/su131910743Suche in Google Scholar

Awan, M. J., Masood, O. A., Mohammed, M. A., Yasin, A., Zain, A. M., Damaševičius, R., & Abdulkareem, K. H. (2021b). Image-based malware classification using VGG19 network and spatial convolutional attention. Electronics, 10(19), 2444.10.3390/electronics10192444Suche in Google Scholar

Cai, J., Luo, J., Wang, S., & Yang, S. (2018). Feature selection in machine learning: A new perspective. Neurocomputing, 300, 70–79.10.1016/j.neucom.2017.11.077Suche in Google Scholar

Canto, A. C., Kermani, M. M., & Azarderakhsh, R. (2021). CRC-based error detection constructions for FLT and ITA finite field inversions over GF (2 m). IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems, 29(5), 1033–1037.10.1109/TVLSI.2021.3061987Suche in Google Scholar

Canto, A. C., Kermani, M. M., & Azarderakhsh, R. (2022). Reliable constructions for the key generator of code-based post-quantum cryptosystems on FPGA. ACM Journal on Emerging Technologies in Computing Systems, 19(1), 1–20.10.1145/3544921Suche in Google Scholar

Canto, A. C., Sarker, A., Kaur, J., Kermani, M. M., & Azarderakhsh, R. (2022). Error detection schemes assessed on FPGA for multipliers in lattice-based key encapsulation mechanisms in post-quantum cryptography. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing, 11(3), 791–797.10.1109/TETC.2022.3217006Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Z., Xing, S., & Ren, X. (2023). Efficient Windows malware identification and classification scheme for plant protection information systems. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1123696.10.3389/fpls.2023.1123696Suche in Google Scholar

Cintas-Canto, A., Kaur, J., Mozaffari-Kermani, M., & Azarderakhsh, R. (2023). ChatGPT vs Lightweight security: First work implementing the NIST cryptographic standard ASCON. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.08178.Suche in Google Scholar

Cintas-Canto, A., Kermani, M. M., & Azarderakhsh, R. (2022). Reliable architectures for finite field multipliers using cyclic codes on FPGA utilized in classic and post-quantum cryptography. IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems, 31(1), 157–161.10.1109/TVLSI.2022.3224357Suche in Google Scholar

Diana, K., Abhishek, A., David, F., Debraj, G., Elia, F., Eric, A., … Yaniv, Z. (2018). Microsoft security intelligence report. SIR Report (Vol. 24, p. 35). https://info.microsoft.com/rs/157-GQE-382/images/EN-US_CNTNT-eBook-SIR-volume-23_March2018.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Djenna, A., Bouridane, A., Rubab, S., & Marou, I. M. (2023). Artificial intelligence-based malware detection, analysis, and mitigation. Symmetry, 15(3), 677.10.3390/sym15030677Suche in Google Scholar

Ethiopia Situation Report. (2022). Insecurity Insight. https://insecurityinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/18-July-2022-Ethiopia-Situation-Report.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2015). Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 1026–1034).10.1109/ICCV.2015.123Suche in Google Scholar

INTERPOL. (2023). African cyberthreat assessment report cyberthreat trends. March 2023, 1–32. https://www.interpol.int/content/download/19174/file/2023_03%20CYBER_African%20Cyberthreat%20Assessment%20Report%202022_EN.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Jung, B., Bae, S. I., Choi, C., & Im, E. G. (2020). Packer identification method based on byte sequences. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience, 32(8), e5082.10.1002/cpe.5082Suche in Google Scholar

Kaur, J., Canto, A. C., Kermani, M. M., & Azarderakhsh, R. (2023). Hardware constructions for error detection in WG-29 stream cipher benchmarked on FPGA. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems.10.1109/TCAD.2023.3338108Suche in Google Scholar

Kermani, M. M. (2007). Fault detection schemes for high performance vlsi implementations of the Advanced Encryption Standard. (Doctoral dissertation). Ontario, Canada: University of Western Ontario.Suche in Google Scholar

Kermani, M. M., Azarderakhsh, R., & Mirakhorli, M. (2016, June). Multidisciplinary approaches and challenges in integrating emerging medical devices security research and education. In 2016 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition.Suche in Google Scholar

Kermani, M. M., Bayat-Sarmadi, S., Ackie, A. B., & Azarderakhsh, R. (2019, February). High-performance fault diagnosis schemes for efficient hash algorithm blake. In 2019 IEEE 10th Latin American Symposium on Circuits & Systems (LASCAS) (pp. 201–204). IEEE.10.1109/LASCAS.2019.8667597Suche in Google Scholar

Koziel, B., Jalali, A., Azarderakhsh, R., Jao, D., & Mozaffari-Kermani, M. (2016). NEON-SIDH: Efficient implementation of supersingular isogeny Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol on ARM. In Cryptology and Network Security: 15th International Conference, CANS 2016, Milan, Italy, November 14–16, 2016, Proceedings 15 (pp. 88–103). Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-319-48965-0_6Suche in Google Scholar

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G. E. (2012). Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 25.Suche in Google Scholar

Krumbach, Jr, A. W., & White, D. P. (1964). Moisture, pore space, and bulk density changes in frozen soil. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 28(3), 422–425.10.2136/sssaj1964.03615995002800030036xSuche in Google Scholar

Lim, H., & Moon, S. (2015). Stable nonpolar solvent droplet generation using a poly (dimethylsiloxane) microfluidic channel coated with poly-p-xylylene for a nanoparticle growth. Biomedical Microdevices, 17, 1–8.10.1007/s10544-015-9974-5Suche in Google Scholar

Mohammed, M. A., Ibrahim, D. A., & Salman, A. O. (2021). Adaptive intelligent learning approach based on visual anti-spam email model for multi-natural language. Journal of Intelligent Systems, 30(1), 774–792.10.1515/jisys-2021-0045Suche in Google Scholar

Mozaffari-Kermani, M., Azarderakhsh, R., Ren, K., & Beuchat, J. L. (2016). Guest editorial: introduction to the special section on emerging security trends for biomedical computations, devices, and infrastructures. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, 13(3), 399–400.10.1109/TCBB.2016.2518874Suche in Google Scholar

Nataraj, L., Karthikeyan, S., Jacob, G., & Manjunath, B. S. (2011, July). Malware images: Visualization and automatic classification. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Visualization for Cyber Security (pp. 1–7).10.1145/2016904.2016908Suche in Google Scholar

Nguyen, H., Di Troia, F., Ishigaki, G., & Stamp, M. (2023). Generative adversarial networks and image-based malware classification. Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques, 19(4), 579–595.10.1007/s11416-023-00465-2Suche in Google Scholar

Niasar, M. B., Azarderakhsh, R., & Kermani, M. M. (2020). Optimized architectures for elliptic curve cryptography over Curve448. Cryptology ePrint Archive.Suche in Google Scholar

Panda, P., CU, O. K., Marappan, S., Ma, S., & Veesani Nandi, D. (2023). Transfer learning for image-based malware detection for iot. Sensors, 23(6), 3253.10.3390/s23063253Suche in Google Scholar

Ren, Y., Zhao, P., Sheng, Y., Yao, D., & Xu, Z. (2017). Robust softmax regression for multi-class classification with self-paced learning. In Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (pp. 2641–2647).10.24963/ijcai.2017/368Suche in Google Scholar

Salota, R., & Singh, I. (2023). Efficient image based malware classification using a modified VGG based deep learning model. Journal of Harbin Engineering University, 44(5), 419–431.Suche in Google Scholar

Sanderson, M., & Christopher D. (2010). Manning, Prabhakar Raghavan, Hinrich Schütze, Introduction to Information Retrieval, Cambridge University Press. 2008, xxi + 482 pages. Natural Language Engineering, 16(1), 100–103. doi: 10.1017/S1351324909005129.Suche in Google Scholar

Saridou, B., Moulas, I., Shiaeles, S., & Papadopoulos, B. (2023). Image-based malware detection using α-cuts and binary visualisation. Applied Sciences, 13(7), 4624.10.3390/app13074624Suche in Google Scholar

Saxe, J., & Berlin, K. (2015). Deep neural network based malware detection using two dimensional binary program features. In 2015 10th International Conference on Malicious and Unwanted Software (MALWARE) (pp. 11–20). doi: 10.1109/MALWARE.2015.7413680.Suche in Google Scholar

Shabtai, A., Moskovitch, R., Feher, C., Dolev, S., & Elovici, Y. (2012). Detecting unknown malicious code by applying classification techniques on OpCode patterns. Security Informatics, 1, 1. doi: 10.1186/2190-8532-1-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Sharif, M. D. H. U., Jiwani, N. A. S. M. I. N., Gupta, K. E. T. A. N., Mohammed, M. A., & Ansari, D. R. M. F. (2023). A deep learning based technique for the classification of malware images. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 101(1), 135–160.Suche in Google Scholar

Shaukat, K., Luo, S., & Varadharajan, V. (2023). A novel deep learning-based approach for malware detection. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 122, 106030.10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106030Suche in Google Scholar

Simonyan, K., & Zisserman, A. (2014). Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556.Suche in Google Scholar

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. (2016). Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (Vol. 2016, pp. 2818–2826). Las Vegas, NV, USA. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2016.308.Suche in Google Scholar

Tan, Z. H., Tan, P., Jiang, Y., & Zhou, Z. H. (2020). Multi-label optimal margin distribution machine. Machine Learning, 109, 623–642. doi: 10.1007/s10994-019-05837-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 58(1), 267–288. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1996.tb02080.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Tibshirani, R. (2011). Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso: A retrospective. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B: Statistical Methodology, 73(3), 273–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2011.00771.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Torrey, L., & Shavlik, J. (2010). Transfer learning. In Handbook of research on machine learning applications and trends: algorithms, methods, and techniques (pp. 242–264). IGI Global.10.4018/978-1-60566-766-9.ch011Suche in Google Scholar

Vasan, D., Alazab, M., Wassan, S., Safaei, B., & Zheng, Q. (2020). Image-Based malware classification using ensemble of CNN architectures (IMCEC). Computers and Security, 92, 101748. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2020.101748.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, H., Li, G., & Tsai, C. L. (2007). Regression coefficient and autoregressive order shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology, 69(1), 63–78.10.1111/j.1467-9868.2007.00577.xSuche in Google Scholar

Williams, C. K. I. (2003). Learning with kernels: Support vector machines, regularization, optimization, and beyond. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 98(462), 489. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2003.s269.Suche in Google Scholar

Yadav, B., & Tokekar, S. (2023). Malware multi-class classification based on malware visualization using a convolutional neural network model. International Journal of Information Engineering and Electronic Business (IJIEEB), 15(2), 20–29.10.5815/ijieeb.2023.02.03Suche in Google Scholar

Zhao, Z., Zhao, D., Yang, S., & Xu, L. (2023). Image-based malware classification method with the AlexNet convolutional neural network model. Security and Communication Networks, 2023, 1–15.10.1155/2023/6390023Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- FSLSM-Based Analysis of Student Performance Information in a Blended Learning Course Using Moodle LMS

- AI in Indian Libraries: Prospects and Perceptions from Library Professionals

- Comprehensive Examination of Version Number Attacks in IoT Networks: Nodes Hyperactivity as Specific Criterion

- AI Literacy and Zambian Librarians: A Study of Perceptions and Applications

- Awareness and Perception of Students Toward Execution of Internet of Things in Library Services: A study of Indian Institute Technologies of Northern India

- Hybrid RSA–AES-Based Software-Defined Network to Improve the Security of MANET

- Enhanced Image-Based Malware Multiclass Classification Method with the Ensemble Model and SVM

- A Qualitative Analysis of Open-Access Publishing-Related Posts on Twitter

- Exploring the Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Academic Libraries: A Study on Librarians’ Perspectives in India

- “Librarying” Under the Candlelight: The Impact of Electricity Power Outages on Library Services

- Management of Open Education Resources in Academic Libraries of Nigerian Public Universities

- The Evolution of Job Displacement in the Age of AI and Automation: A Bibliometric Review (1984–2024)

- Review Article

- Open Network for Digital Commerce in India: Past, Present, and Future

- Communications

- Publishing Embargoes and Versions of Preprints: Impact on the Dissemination of Information

- The Detection of ChatGPT’s Textual Crumb Trails is an Unsustainable Solution to Imperfect Detection Methods

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- FSLSM-Based Analysis of Student Performance Information in a Blended Learning Course Using Moodle LMS

- AI in Indian Libraries: Prospects and Perceptions from Library Professionals

- Comprehensive Examination of Version Number Attacks in IoT Networks: Nodes Hyperactivity as Specific Criterion

- AI Literacy and Zambian Librarians: A Study of Perceptions and Applications

- Awareness and Perception of Students Toward Execution of Internet of Things in Library Services: A study of Indian Institute Technologies of Northern India

- Hybrid RSA–AES-Based Software-Defined Network to Improve the Security of MANET

- Enhanced Image-Based Malware Multiclass Classification Method with the Ensemble Model and SVM

- A Qualitative Analysis of Open-Access Publishing-Related Posts on Twitter

- Exploring the Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Academic Libraries: A Study on Librarians’ Perspectives in India

- “Librarying” Under the Candlelight: The Impact of Electricity Power Outages on Library Services

- Management of Open Education Resources in Academic Libraries of Nigerian Public Universities

- The Evolution of Job Displacement in the Age of AI and Automation: A Bibliometric Review (1984–2024)

- Review Article

- Open Network for Digital Commerce in India: Past, Present, and Future

- Communications

- Publishing Embargoes and Versions of Preprints: Impact on the Dissemination of Information

- The Detection of ChatGPT’s Textual Crumb Trails is an Unsustainable Solution to Imperfect Detection Methods