COVID-19 Emergency Remote Teaching: Lessons Learned from Five EU Library and Information Science Departments

-

Juan-José Boté-Vericad

, Cristóbal Urbano

, Sílvia Argudo

, Stefan Dreisiebner

, Kristina Feldvari

, Sandra Kucina Softic

, Gema Santos-Hermosa

und Tania Todorova

Abstract

Analysis of the context and response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown of five European Library and Information Science Departments: University of Barcelona (Spain), University of Hildesheim (Germany), University of Osijek, University of Zagreb (Croatia), and University of Library Studies and Information Technologies in Sofia (Bulgaria). Data about this situation in relation to higher education were collected 1 year after the lockdown when countries had returned to normality. The methodology consisted of holding focus groups with students and individual interviews with teachers. The data were analysed by unifying the information collected from each country into a centralized dataset and complemented with texts from the transcripts highlighted by each partner. The results indicate that each partner experienced a unique situation; as COVID-19 lockdowns were different in every European country, each university or even each teacher responded to the crisis differently. Nevertheless, there are points that are common to all five universities analysed in the study, such as work overload in students and teachers or the replication of face-to-face teaching models in a remote format. Moving in the future to online or hybrid learning activities will require training teachers in a more systematic way and the appropriate infrastructure.

1 Introduction

The advent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown precipitated an exigent circumstance within the realm of higher education. The aim of this paper is to analyse the Emergence Remote Teaching (ERT) response of five European Library and Information Science (LIS) Departments to the COVID-19 lockdown, highlighting unique experiences while identifying common challenges and the need for structured teacher training; infrastructure for online, blended or hybrid learning; and thorough planning of the teaching activity. We perceive hybrid learning as a model where a segment of the student group engages in face-to-face learning, while another segment participates in the class remotely through online means. In contrast, by blended learning, we mean an approach of education in which traditional in-person classes are supplemented or supported with technology and learners take advantage both of online and offline resources.

1.1 The DECriS Project and the Analysis of the ERT Response to COVID-19

This article illustrates the overall results of a qualitative study performed as part of the Erasmus + project “Digital Education for Crisis Situations: Times when there is no alternative (DECriS)” whose main objective was to investigate how the European LIS Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) practice online education and use open educational resources (OERs) in times when there was no other alternative, especially to analyse the perceptions and experience of all stakeholders involved. In this qualitative study, we analysed the attitudes, expectations, problems, adaptability, pros and cons, and lessons learned in Digital Education (DE) during the COVID-19 crisis. During the COVID-19 outbreak, UNESCO made a survey of about 222 HEIs from 67 countries about the response of the HEIs to remote teaching (UNESCO, 2020) in relation to the teaching and learning cycle. One of the results was that 79% of surveyed institutions offered forms of online remote learning for students. According to this report, surveyed HEIs offered positive solutions in the crisis situation; however, it was still unclear whether these measures had a positive impact on teachers and students.

Teaching and learning during the COVID-19 lockdown were part of the emerging crisis situation that had never been seen on a global scale before. There have been similar situations in countries with complex geopolitical characteristics, such as South Africa (Czerniewicz, Trotter, & Haupt, 2019), or when natural disasters occur, such as floods or earthquakes (Ayebi-Arthur, 2017; Collings, Gerrard, & Garrill, 2019; Liang, Chen, Wu, Yen, & Chang, 2015; Richardson et al., 2015). Nevertheless, most generations have not lived through a pandemic situation since the Spanish Flu in 1918 (Fornasin, Breschi, & Manfredini, 2018) or Ebola (Walsh, De Villiers, & Golakai, 2018). In the case of COVID-19, most HEIs shifted overnight from face-to-face teaching to remote teaching. This meant that lecturers had to teach online, either synchronously or asynchronously, and students also had to learn remotely online. In this article, we focus our attention on how remote teaching was carried out and the perceptions of the teachers and students one year after the lockdown in five LIS departments.

The process of teaching and learning during the COVID-19 lockdown has been given different names in the scientific literature, such as distance learning (Sarwari, Kakar, Golzar, & Miri, 2022), distance teaching (Boté-Vericad, 2021a), emergency remote teaching (Alqabbani, Almuwais, Benajiba, & Almoayad, 2021; Maraqa, Hamouda, El-Hassan, Dieb, & Hassan, 2022; Walsh et al., 2018), and remote learning (Stewart, Baek, & Lowenthal, 2022; UNESCO, 2020). In all cases, definitions among authors vary slightly, and a variety of names have been used for teaching and learning in a crisis scenario. In this article, we will use the terms remote teaching and remote learning.

1.2 The Context of the LIS Departments Involved

The Erasmus + project involved five partners: University of Barcelona (Spain), University of Zagreb (Croatia), University of Osijek (Croatia), University of Hildesheim (Germany), and University of Library Studies and Information Technology (Sofia, Bulgaria). During the COVID-19 lockdown, the situation in relation to teaching and mobility was different for each partner. For instance, in the case of the University of Barcelona, teachers were instructed to perform the usual teaching schedule, and mobility was seriously restricted. In the case of the University of Zagreb, at the time of the lockdown, there was an earthquake that added more difficulties to the teaching and learning activities; nevertheless, Croatian students received remote teaching. The students’ situations at the University of Osijek were similar to those of Zagreb, except for the earthquake, which did not affect Osijek. In Hildesheim, Germany, students were allowed to move around with some freedom. Finally, at the University of Library Studies and Information Technologies in Sofia, Bulgaria, students had to remain at home with mobility restrictions. From a cultural teaching context perspective, all teaching plans among partners are similar, and other cultural aspects were not considered in this study. In this regard, Hildesheim has a more tech-oriented approach, while the other centres, despite the digital transformation they have undergone, also lean towards the more traditional library-archival field. However, these differences are more pronounced at the undergraduate versus master’s level. As explained in the methodology section, we aimed to account for this by selecting professors and organizing separate focus groups for undergraduates and master’s students. Our primary objective was to identify exceptional teaching scenarios.

This article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a literature review focused on remote teaching and learning in higher education. This is followed by Section 3, which describes the methods and materials used in this study. Section 4 shows the results and provides an analysis of the main findings, complemented by Section 5 with a discussion of the results. Finally, Section 6 is devoted to conclusions and limitations.

2 Literature Review

This section will cover different situations under the COVID-19 lockdown related to the levels of satisfaction and motivation concerning the shift from face-to-face to online learning. These studies reflected the beliefs and thoughts at a precise moment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of these studies were carried out at the beginning of the lockdowns in different countries. It is certainly true that the lockdown did not start in the same way in all countries, and there was no lockdown in all countries (Boté-Vericad, 2021a).

We start with three notable studies that were conducted before COVID-19. Czerniewicz et al. (2019) carried out a study in South Africa during the student protest of 2015 to research blended learning in four universities. They interviewed 16 faculty members from the Commerce, Engineering, and Humanities faculties, as well as students and professional staff, to explore their experiences with blended learning. The study found that teachers considered blended learning a legitimate supplement to face-to-face activities, but many had yet to incorporate it into their courses. Teachers believed that it is essential for students to participate in social activities and interactions in class; however, they found low engagement from students, which may have exacerbated inequalities among students from different economic levels. Blended learning was also found to be a problematic strategy for completing the curriculum before exams, with teachers wanting to finish the curriculum and give students opportunities to practice exams. In conclusion, the study highlights the benefits and challenges of blended learning in higher education.

The second study is related to COVID-19, although the study was carried out before the lockdown and during the lockdown. Žuljević, Jeličić, Viđak, Đogaš, and Buljan (2021) studied the satisfaction and burnout levels of medical students at the University of Split School of Medicine in Croatia before (N = 437) and after (N = 235) the COVID-19 lockdown. They found that the switch to e-learning did not affect burnout levels among medical students. The third is a study of postsecondary students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Almusharraf and Khahro (2020) surveyed (N = 283) students to evaluate their satisfaction with online learning experiences. The study found that students were satisfied with staff and faculty members and the use of Google Hangout, Google Classroom, and Moodle. However, the authors suggested that HEI teachers should reconsider assessment types and weights to better evaluate students’ learning processes. These studies highlight the importance of evaluating the effectiveness and satisfaction of online learning experiences during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the need for faculty members to adjust their teaching and assessment methods to ensure optimal student learning.

Baber (2020) made a survey in South Korea and India to explore the determinants resulting in the students’ perceptions of their learning outcomes and student satisfaction. The sample was composed of students (N = 100, 50 from each country) from different institutions in the two countries, using a convenience sample. The results indicated that students had no previous experience in online education, and online learning increased student motivation and satisfaction. These factors were due to interaction in the online class, course structure, and the role of the teacher as a knowledge facilitator.

Later, in Romania, Boca (2021) conducted a study at the Technical University of Cluj Napoca, Romania, that examined students’ behaviour in relation to online education during the pandemic. The sample comprised 300 students who completed a questionnaire with sections on sociodemographic characteristics, behaviour related to time spent using online educational tools, knowledge of the culture of virtual media, and satisfaction with the quality of online courses. The study found that 56.66% of respondents were female, and 33% thought that online education was better than face-to-face learning. Furthermore, 23% believed that online education and digital resources could complement face-to-face lectures. Multiple-choice tests were the preferred examination type for 70% of female respondents and 38.33% of all respondents. The author concluded that individual characteristics and knowledge of digital platforms were the strongest predictors of the students’ attitudes towards online learning.

Buttler et al. (2021) performed a study among students (N = 400) in Central Alberta, Canada. These authors sent a questionnaire by email and obtained a 65.5% response rate. In this questionnaire, students were asked about the quality of Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) during the COVID-19 lockdown. Using structural equation modelling, they found that students were satisfied with the final exam format, as well as teacher support and care, which led to better student learning. Moreover, technology issues did not play a major role for students or for the quality of presentations. Nevertheless, communication between the university and students and between teachers and students had a significant impact on student performance. They concluded that a range of factors should be considered in further studies: high-quality presentation, promoting interaction in the many ways that online programs allow, encouraging positive emotions, having adequate technology, and frequent contact with classes and individual students.

In Egypt, Eltaybani et al. (2021) performed a cross-sectional online survey addressed to nursing students (N = 580) and nursing educators (N = 95). The survey, on a Likert Scale, assessed participants’ preferences for online versus paper surveys and e-learning experiences. They found that 71% of students and 76% of educators preferred responding to online surveys. However, students perceived the quality of e-learning as significantly lower (2.5 ± 1.3) than educators did (3.5 ± 1.0). Students also rated teaching (2.6 ± 1.2), social (2.6 ± 1.4), and cognitive (2.8 ± 1.3) presences significantly lower than the educators did (3.9 ± 0.9,3). In fact, 72.9% of students and 46.3% of educators said that traditional learning is more effective than e-learning. They concluded that the students’ experience during the COVID-19 pandemic was worse than that of the educators. These lower scores given by students could be because the students did not receive any training in e-learning and had limited digital skills. Educators were in a similar situation, as they needed to be trained in remote learning and computer tools.

In Pakistan, Faize and Nawaz (2020) carried out a study that measured the students’ satisfaction level concerning adopting online learning. They performed a pre-modification and a post-modification test. In the first phase, they obtained 179 responses, and in the second phase 163 responses. In the first phase, they found that the main challenges in learning were connectivity, resources, and lack of interaction. However, in the second phase, they found that students were satisfied with the level of interaction with the teacher during an online class. They concluded that training teachers to teach online before the second phase led to better-reported results than in the first phase. Nevertheless, they found that online learning cannot replace formal classrooms because, despite students’ satisfaction, it was not their preferred method.

Chierichetti and Backer (2021), at the College of Engineering at San José State University (SJSU) (California, United States), explored the impact of COVID-19 on faculty who were forced to shift to an online learning environment. They performed mixed-method research using a quantitative questionnaire followed by a qualitative study using interviews. The questionnaire was completed by 98 faculty members (34%). Interviews were held with 23 participants, 6 were identified as female and 16 were identified as male. In their results, they found that in the survey 34.8% had to care for children. A total of 59% of female faculty had much higher responsibilities than male faculty because they had to take care of children or elderly people, compared to 24.6% of the male faculty. Most faculty members reported feeling more stress as a result of COVID-19, especially females (62%). In relation to online tools, the faculty reported that Canvas was the most used tool (95.7%), followed by online videos or tutorials. The teachers indicated that they had difficulties at first and had to change the evaluation system. One of the main problems was students cheating. Nevertheless, faculty members reported that they had a positive experience shifting to emergency remote teaching. They concluded that it was challenging to keep students engaged and carry out hands-on laboratory activities in a fully online environment.

Crick et al. (2020) analysed emergency remote teaching in the community of computer science teachers in the United Kingdom. They carried out a large survey (N = 2,197) among teachers who were actively involved in learning, teaching, and assessment. They sent the survey in March 2020. They found that computer science teachers were well prepared to deliver online learning, and they could access appropriate technologies to support it. The survey also had open questions for qualitative data, and they found that teachers were positive about online teaching. They concluded that there will be a considerable demand for digital skills and infrastructure to support post-COVID economic renewal.

In Jordan, a study explored students’ attitudes towards online learning during COVID-19. They surveyed (N = 4,037) students from private and public universities. They found that arts and humanities courses were better suited for online teaching/learning than science courses. Despite this difference, the attitude towards taking online courses in the future was quite similar: 49% of arts and humanities students, and 40% of science students were open to this option. They also found that lockdown measures caused stress, frustration, and depression for both student types (63% in arts and humanities; 61% in sciences) and had an adverse effect on their attitude towards online learning (Al-Salman & Haider, 2021). Another study explored the students’ perspectives on effective online learning and teaching in two institutions in the United States and one in Saudi Arabia, surveying a total of N = 890 participants. They found eight items contributed to defining effective online teaching: motivating students to achieve, communicating effectively, meeting students’ needs, providing access to a wide range of content, having a well-organized course structure, supplying numerous sources, providing explanatory feedback, and facilitating meaningful discussions (Ozfidan, Ismail, & Fayez, 2021).

Other studies focus on faculty members and students. Altwaijry et al. (2021) explored the experience of academic staff and students with remote education during the COVID-19 pandemic at the College of Pharmacy in Saudi Arabia. They performed a mixed-method approach using a survey followed by a focus group discussion. In their results, they found that participants were satisfied with their readiness for remote education (faculty = 3.89, students = 3.82 on the Likert Scale). The perception of remote education was also evaluated positively (faculty = 3.95, students = 3.47). However, they also found some barriers, such as technical difficulties during the assessment (faculty = 4.03) and teaching (faculty = 3.97) process. For students, focusing on the computer screen for a long time (students = 4.19) and limited communication compared to face-to-face classes (students = 4) were considered obstacles. Both teachers and students found focusing on a computer screen for a long time to be a problem (faculty = 4.03, students = 4.19). They concluded that the main challenge was active communication among students and faculty members. Teachers considered it an opportunity to develop teaching skills, and students regarded it as a chance to improve independent learning skills.

On a national scale and promoted by institutions of university support and cooperation, it is worth mentioning the studies carried out in Croatia and the Catalan linguistic domain in Spain. The research by the Croatian Agency for Science and Higher Education (2021) was titled Students and the pandemic: How did we survive? It was carried out with 4,300 students in higher education and indicated that the transition to online modalities of education during the pandemic had a significant impact on the mental health of students, their social inclusion, study experience, and the quality of student life. Students expressed satisfaction with certain parts of the organization of online classes and exams, such as home access to learning materials (73%), interaction with teachers in a virtual environment (60%), criteria and methods of student evaluation (63%), and the objectivity of evaluation (60%).

A similar study was carried out by the Xarxa Vives d’Universitats (Ariño et al., 2022), a network of Spanish universities from the Catalan linguistic domain (Andorra, Balearic Islands, Catalonia, and Valencia), that every academic year publish the report Via Universitaria: Access, learning conditions, expectations and returns for university studies to gain insights from the students. The last report, covering the years 2020–2022 with a participation of 49,291 students, was mainly focused on the pandemic experience; however, the results were compared with previous years. For instance, the data collected show that the activities that students prefer continue to be the same as in the last edition, i.e. those that promote active and experiential learning, which was a real challenge during the pandemic. The study devoted particular attention to psychological issues, creating a picture of what the pandemic may have caused: 17.1% of students reported suffering from depression over the previous 12 months. In terms of anxiety, the percentage reached 19.5, whereas for other mental health problems, the percentage was 10.2.

With a similar approach to the two previous studies, but on a European scale, we should mention the work by Doolan et al. (2021), commissioned by the European Students’ Union under the title Student Life During the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown: Europe-wide Insights. The questionnaire was answered by 17,116 students from 41 European countries. Although participation had a very uneven geographical representation (almost 80% of the responses came from only four countries: Portugal, Romania, Croatia, and the Czech Republic), the topics covered and some findings are relevant to our study. It is worth noting that most of the students indicated that their study workload was larger than before the pandemic on-site classes were cancelled (50.74%). Only 19.04% said that their workload was smaller than before, whereas 25.46% reported no changes in their perceived study workload. Students indicated that their workload had increased because teachers compensated for the lack of on-site classes with additional assignments. A total of 47.43% of students indicated their performance as a student had changed for the worse since on-site classes had been cancelled.

Also with a broad international scope and with a very different methodological approach, Stracke et al. (2020) worked to identify the diverse responses that governments, educational systems and their policymakers from 13 countries (Australia, Brazil, France, India, Mexico, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Spain, South Korea, Sweden, Taiwan, Turkey, and the United Kingdom) chose and followed during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data were collected by observers who analysed institutional and government documents from the assigned areas to identify good practices of open education and recommendations from the collected case studies that can be applied in the future.

In conclusion, the studies conducted by Baber (2020), Boca (2021), Buttler (2021), Crick et al. (2020), the Croatian Agency for Science and Higher Education (2021), Faize and Nawaz (2020), Ozfidan et al. (2021), and Žuljević et al. (2021) showcase student and professor satisfaction with blended learning or emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that these authors employ varying terms to denote these teaching modalities, including blended teaching, distance learning, or e-learning. Other studies have identified challenges faced by both students and professors. Altwaijry et al. (2021), Al-Salman and Haider (2021), Chierichetti and Backer (2021), Czerniewicz et al. (2019), Doolan et al. (2021), and Eltaybani et al. (2021) discovered difficulties and barriers, including technical challenges during assessments, mental health concerns, and excessive student workloads.

In summary, most analysed articles and reports predominantly utilized survey techniques and to a lesser extent qualitative methods like interviews and focus groups. No studies focused on the LIS discipline, and few employed qualitative approaches to compare international experiences for both teachers and students. This literature review underscores the originality of our study and its complementary nature to prior research.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research Questions

Considering the context of the centres, the study’s purpose, and the framework of the literature review conducted, this article aims to answer the following research questions regarding the COVID-19 crisis based on the students’ and teachers’ views of the learning and teaching situations at that time:

RQ1. How did teachers and students cope with the challenge of the COVID-19 crisis and how did they adapt and adjust to the new circumstances?

RQ2. What differences in teaching/learning performance were observed between the first semester of teaching affected by the pandemic (spring–summer of the 2019-2020 academic year) and the second semester (autumn–winter of the 2020–2021 academic year)?

RQ3. What is the teachers’ perception of how HEIs adapted their structure, services, and policies to teaching during the lockdown and the following academic year?

RQ4. What are the lessons learned and best practices from these five HEIs?

3.2 Research Design, Sampling and Data Collection

This paper is part of the Intellectual Output 2 of the DECriS Project, a bigger research activity in which additional information has been obtained. Since the methodology is unique to the complete study, in this manuscript we show the results in relation to the HEIs’ responses to the pandemic and reflect on the digital transformation of the HEIs, looking at the attitudes, expectations, problems, adaptability, pros and cons and lessons learned in DE during the COVID-19 crisis (Table 1).

Seven blocks with topics to ask students and professors

| Attitudes | To identify, analyse, and classify teachers’ and students’ attitudes towards digital education, especially towards OER, in the COVID-19 era in contrast to their attitudes before the pandemic |

| Expectations | To identify, analyse, and classify the expectations that teachers and students had at the beginning of the crisis situation about teaching in a fully digital/remote environment |

| Problems | To identify, analyse, and classify the actual and objective problems that teachers and students encountered while working with digital material and activities during the crisis (tools, applications, platforms, connection, devices, etc.) |

| Adaptability | To identify and analyse the kind of adjustments and the degree of flexibility with which teachers and students have adapted to new circumstances, especially those teachers who had no experience in the pedagogical requirements of DE |

| Advantages and disadvantages | To identify, analyse and classify the reasons expressed by teachers and students for whether they foresee further use (or not) in “normal” situations of some of the tools that DE offers and that were used during the crisis situation |

| Lessons learned & Improvements/good practices | In a general approach, to collect, analyse, and summarize the framework of lessons learned about DE during the crisis. In a more specific approach, to collect, analyse, and classify teachers’ and students’ proposals (or good practices of third parties that have been identified) for improving the online teaching/learning, the use of digital materials and OER in the future, in the case of new crisis situations, or in an integrated way in future normal teaching, based on the lessons learned |

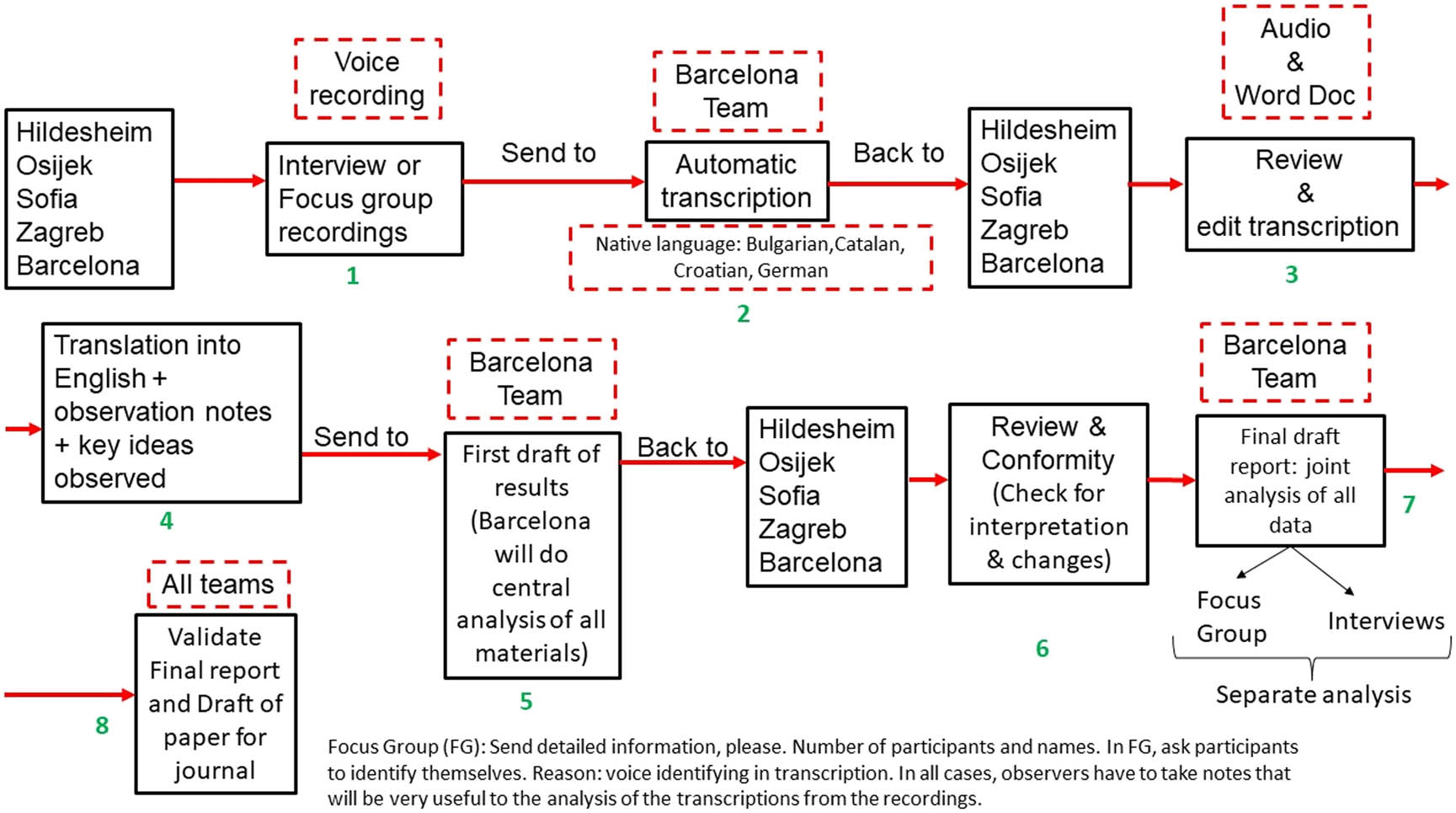

We created a methodological guide to analyse the data obtained by the different partners (Boté-Vericad, Argudo, & Urbano, 2022). This guide explained which concepts should be covered in the interviews and in the focus groups, as well as the data flow. We decided that just one partner (the Barcelona team) would analyse all the datasets to avoid different sorts of analyses being used or completely different interpretations being made. The partners chose their sample from teachers and students according to the methodological guide.

As we use two qualitative techniques that involve a relatively small number of people compared to the total teacher and student populations, it was necessary to determine the criteria and the sampling system very well to decide who would be interviewed and who would be part of the focus groups. Purposive sampling (i.e., non-probabilistic sampling) was performed according to the criteria of each partner to coordinate their interviews and focus groups. The criteria for selecting students and professors were consistent across all partners, as explained in the following paragraph.

To simplify carrying out the interviews and focus groups, once the criteria and the sampling routine had been established, each partner institution selected participants considering that it was necessary to ensure that the samples had the appropriate representation of the different levels and types of subjects included in the study. It was necessary to include the following:

Students of various courses and levels of education who were enrolled during the pandemic period of lockdowns (2020–2021). Both bachelor’s and master’s degree students had to be represented. There needed to be proportionality between genders and age groups. For example, the proportionality of genders had to ensure that there were participants of both genders.

Bachelor’s degree teachers, master’s degree teachers, and teachers who teach at both levels of education had to be represented. The proportionality between genders and age groups also had to be respected.

The teaching area of each teacher also had to be considered as a variable, keeping in mind that some people teach in more technological/practical areas and other people in less technological/practical areas, and each area involved a different approach for shifting to the emergency digital remote teaching.

Participants were requested to give their informed consent and the process of interviews and focus groups was approved by the Bioethics Commission (CBUB) of the University of Barcelona as the project team from the UB led this work package, and the outputs of this study were planned in a unitary approach (Figure 1).

Methodological pathway to analyse data among partners.

The interviews and focus groups were conducted by each partner following common guidelines and were recorded in their corresponding native languages: Bulgarian, Catalan, Croatian, German, and Spanish. The composition of the focus groups was balanced, including both men and women. Table 2 represents the composition of all focus groups and interviews conducted by partners.

Number of interviews and focus groups held by all partners in alphabetical order

| Partner | Interviews | Focus Groups (Students) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | Bachelor | Master | Number of participants | |

| Barcelona (BA) | 7 | 7 | 1 (4) | 1(6) | 10 |

| Hildesheim (HI) | 1 | 2 | — | 2(9) | 9 |

| Osijek (OJ) | 5 | 4 | 1 (6) | — | 6 |

| Sofia (SO) | 4 | 4 | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 16 |

| Zagreb (ZA) | 2 | 3 | 1 | — | 6 |

| Total | 19 | 20 | 7 | 3 | 47 |

The audio recordings were transferred to the University of Barcelona team, who made an automatic transcription into the language of each partner through a commercial platform, Happy Scribe. All partners were in charge of editing and verifying their own transcriptions to check accuracy. Once the transcription process was done, all transcriptions were subsequently edited and translated into English by each of the participating teams. During the editing and translation process, the most important phrases and concepts were highlighted to guide the Barcelona team with the relevant sections of the conversations. Then, all partners sent the transcript translated into English with the most relevant parts highlighted to avoid bias in the interpretation of the results.

Later, the Barcelona team analysed the complete dataset. The analysis was double-checked to avoid bias and misunderstandings. Once the data had been analysed, a report was prepared and sent to all partners, so they could check and verify that what was analysed corresponded to the context. With all the text files in English, the Barcelona team worked on the inductive coding of all the transcripts and data analysis to prepare the reports of each centre and the final joint report. Using inductive coding, codes and categories emerge from the data itself, without preconceived notions. It involves identifying patterns and themes to develop a grounded understanding of the information.

The data were analysed following the qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2010). A total of 39 interviews with teachers and 10 focus groups with a total of 47 students were conducted during the first quarter of the year 2022. The breakdown by partners is in Table 2. Throughout the report, all the quotes from the interviews are labelled with the partner code followed by the interview number (e.g. [OJ_1] for Osijek teacher #1); for focus groups, we added the letters FG before the number (e.g. [OJ_FG_1] for Osijek focus group #1).

4 Results

The results of this study show that there were a wide variety of situations among partners. The different partners showed some similarities in perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic; nevertheless, there were also some differences. In this section, we summarize the adaptation to new circumstances, the students’ performance, the adaptation of the HEIs’ structures, services, and policies to teaching during the lockdown, as well as the lessons learned and best practices. In terms of digital infrastructures, all partners share similar systems, such as an educational content management platform like Moodle, to deliver educational materials to students. However, there are slight differences in video conferencing applications, with variations in software choices like Big Blue Button, Blackboard Collaborate, or Google Meet. Despite these nuances, the overall situation among all partners was very similar.

4.1 Adaption and Adjustments to New Circumstances

Amidst the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers’ experiences in adapting to remote learning were marked by distinct patterns. These patterns emerged based on the teachers’ prior familiarity with blended learning or their encounter with the pandemic-induced lockdown as an innovative challenge. This division served as a significant precursor to understanding their varied approaches to transitioning to virtual classrooms.

However, the process of adapting was not without its hurdles. The pandemic’s unexpected shift to remote learning brought personal limitations to the forefront. A teacher from the University of Barcelona, for instance, expressed concerns related to the transition from a formal teaching environment to their own homes. The absence of specialized teaching equipment, suitable communication platforms, and an organized teaching setup posed initial concerns for educators, potentially affecting their teaching effectiveness and students’ learning experiences:

“The first feeling, in a way, was one of concern. Well, that’s because you’re not in the teaching environment where you usually conduct classes. You’re in your home. You’re not in a place where you have cameras, where you have sound, where you have a space set up to communicate. You have your home set up just for what you set up a home. But you don’t have a space to communicate with the network and that. The first feeling was this.” [BA_5]

In the University of Osijek, one teacher’s assumption that students preferred independent tasks over online classes was debunked. Students, contrary to this presumption, expressed a desire for online lectures that mirrored the structure of traditional classroom interactions. This mismatch between assumptions and student preferences highlighted the complexities of adapting pedagogical strategies to the unprecedented remote learning landscape:

“So, from the beginning when we started, the first two weeks, it seemed to me that it would be simpler for students to have more independent tasks because it seemed to me that somehow it would be easier to work if they managed their own time. So, I wouldn’t give lectures, I’d give them a text to read. And then through online consultations we would comment on that text. Which turned out to be a completely wrong assumption, because students literally wanted online classes. They wanted to go into online classes that were really no different from contact classes in the classroom.” [OJ_9]

Student experiences also played a pivotal role in shaping the transition. The importance of social connections became evident, as students in various institutions sought to maintain a sense of camaraderie. For instance, students from Hildesheim utilized WhatsApp groups to stay connected with peers and instructors, bridging the gap left by physical classroom interactions:

“Yes, I also tried via WhatsApp to keep in touch with the people I already knew from before Corona, so to speak, and who I had met a few times. Then in the summer, when it was allowed again and so on, and yes, with the lecturers. I don’t think I asked many questions in person before Corona, but in the first semester I think you only have these big lectures, so you didn’t really need it. But yes, when I did, I also wrote in the forum or asked questions by email. But I always got answers relatively quickly. So, it wasn’t like I didn’t get an answer or anything. Otherwise, we also had a WhatsApp group, somehow from [the degree program], where sometimes people asked or answered questions. Sometimes you found out about something faster there than if you had written an email to the lecturer.” [HI_FG_2]

The earthquake in Zagreb added an additional layer of challenge to remote learning. Students and teachers navigated through various approaches to lectures, with some instructors opting for synchronous sessions while others provided pre-recorded content. The response of students to these different approaches varied, with some students resisting asynchronous methods, underlining the complexities of catering to diverse learning preferences in a remote setting.

“For me, there was a big difference between the study groups. In [subject X], for example, teachers most often left a recorded lecture that we could listen to later. Or they would have a live lecture, but they would also record it and leave the recorded version for us to view and listen later. In the case of [subject Y], for example, classes were held in real time, and some people would even object a lot if they left us recordings.” [ZA_FG_1]

Assessing, monitoring, and grading in remote teaching was one of the main concerns that emerged during the pandemic period. The contrast between the teacher's experience and the student’s expectations and experience is very interesting. In general, students expected a more tailored assessment. For them, the exams were very similar to the usual ones, but conducted online with a series of complex mechanisms to ensure that they did not copy.

“I must mention that the examinations were conducted online, which introduced challenges related to cheating and monitoring student behaviour. Implementing time limits was a strategy to mitigate this issue. Striking the right balance was crucial – too little time might pressure students unduly, while too much time could facilitate cheating. Despite these concerns, there haven’t been any reported complaints about this approach.” [OJ_5]

Adapting to the COVID context, teachers’ experiences varied between those familiar with blended learning and those finding the lockdown innovative. Personal limitations impacted adaptation, exemplified by a University of Barcelona teacher’s concerns about home setup. At the University of Osijek, a teacher’s initial assumption that students preferred independent tasks over online classes proved wrong. Students emphasized social aspects, using WhatsApp groups to connect. In earthquake-affected Zagreb, diverse approaches to synchronous and recorded lectures were noted, with some students resisting asynchronous methods. The accounts underscore the complexities of transitioning to remote learning amid personal, technological, and social considerations.

In summary, teachers’ adaptation to remote learning was influenced by their prior exposure to blended learning, while personal limitations further complicated the process. Student perspectives underscored the importance of social connections, and the unique challenges faced by earthquake-affected institutions added an extra layer of complexity. The narrative of adaptation during the pandemic is one marked by multifaceted considerations, ranging from technological constraints to student engagement, and speaks to the resilience of the academic community in the face of unprecedented challenges.

4.2 Teaching and Learning Performance

The main topic of the interviews and focus group discussions was the initial confinement period from March to July 2020, which affected the ability to conduct exams and evaluations in person. The participants were interviewed in the first trimester of 2022 and were asked about the September 2020–July 2021 academic year. Despite some resolved issues, the following academic year was far from normal, and the teaching staff had to prepare multiple plans for their courses. Most teachers, with few exceptions, acknowledged the pandemic’s negative impact on academic performance and learning levels. For example, most students did not have a dedicated space at home to work, affecting their pace of work, which in turn influenced their performance and results. A Barcelona professor emphasizes this issue, which is similarly present among the other partners, regardless of students’ gender:

“I remember a student once explaining the issues she faced while working at home. This, I believe, became quite apparent. Many people don’t have what this girl told me about, how ‘both my parents work remotely.’ I have a sister who’s also studying, and we all have to share one computer. And of course, the time I can have access to it is very limited, right? Well, this also poses a problem.” [BA_3]

Final-year students expressed concerns about lowered learning standards and potential effects on their integration into the labour market. The transcripts revealed a lowering of passing thresholds and teacher adaptation to the situation. The return to lockdowns and restrictions due to new waves of the pandemic in autumn 2020 caused confusion, fatigue, and pessimism among all involved parties, highlighting the pandemic’s far-reaching effects on education.

In general, teachers said that the exceptionality of the situation affected academic performance and learning levels, although, in some very specific and minority subjects, performance was assessed as even better than in the normal situation immediately before. However, in general, the impression obtained from reading all the transcripts is that there was a “lowering” of the thresholds so that students could pass the subjects and that teachers adapted the assessment to the precarious circumstances of the teaching provided. Some students, especially those in the final years, were also concerned about the lowering of learning standards and what this might mean for their integration into the labour market.

4.3 The Teachers’ View

Teachers were forced to be flexible with deadlines during the first year of the pandemic, which may have affected academic performance. A teacher from Barcelona pointed out that this flexibility was necessary:

“[…] I attempted to be more lenient regarding the deadlines of assignments. It was mentioned that several students were distressed, and it’s possible that many students were experiencing complex family situations. Due to these circumstances, I decided to be more accommodating with the submission deadlines.” [BA_12]

A teacher from Osijek addressed the difficulty of evaluating students’ grades amid the emergency situation. Surprisingly, online grades were poorer compared to physical classes, even with on-time test submissions. The absence of clear instruction and tutorials for assessment and exam development, despite support for online tools like BigBlueButton and Moodle, compounded challenges. Crafting evaluations to suit virtual learning, including defining suitable time limits and question formats, proved particularly complex. These observations underline the intricacies of remote evaluation, necessitating a delicate balance between academic rigour, coherent guidance, and the need to adapt assessments effectively for an online environment:

“Surprisingly, grades were worse online than in the physical classroom, despite students submitting their tests before the deadline. The lack of instruction and tutorials on assessment and exam creation were identified as issues, despite good support for using online tools such as BigBlueButton and Moodle. The evaluation process, including determining appropriate time limits and question types, was a particular challenge.” [OJ_6]

During the pandemic’s initial year, teachers adjusted deadlines due to student distress. A Barcelona teacher highlighted flexibility due to complex family situations. In Osijek, online grades were unexpectedly lower than in physical classes, despite timely submissions. Lack of assessment guidance, despite online tool support, complicated evaluations. Crafting virtual assessments with suitable limits and formats posed challenges. Remote evaluation complexity, balancing rigour and guidance, became evident. Grades were worse online, even with timely submissions. Instruction and tutorials were lacking for assessment. Crafting virtual assessments proved complex due to diverse formats and limits, highlighting evaluation intricacies in remote learning.

4.4 The Students’ View

In comparison to the assessment systems prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, during the outbreak, students pointed out experiencing a significant diversity in grading and assessment methods. This implies that not all courses adhere to the same approach in evaluating student performance. Students noted various grading techniques and a wide array of assessment systems employed in their subjects. This variability in assessment approaches might have emerged due to the adjustment to the exceptional circumstances of remote learning. The existence of this diversity could have impacted students’ expectations, study methods, and their ability to adapt to different forms of assessment. While it can provide an enriched learning environment, it may also necessitate greater comprehension and adaptability from students to excel in different academic contexts.

“There were many different requirements. Some teachers, for example, asked that a test be written and sent to them. The others required term papers, various tests, presentations and additional assignments to the specific subject being taught.” [SO_FG_3]

According to students in Zagreb, the 2020–2021 academic year was better organized and showed improved teaching performance.

“Yes, well it was much better. Everybody knew how to use the online system better and the teachers were better organized. And I know that in the summer I only had one teacher who kept live lectures, with the option to join the online class for those who are not from the city or who don’t want to come for health reasons.” [ZA_FG_1]

During the initial confinement (March–July 2020), interviews and discussions focused on remote exams and evaluations. Participants reflected on the 2020–2021 academic year in early 2022. Despite adapted plans, the year remained abnormal, impacting learning. Teachers noted negative effects on academic performance and learning levels due to the pandemic, leading to lowered passing thresholds. Teachers showed flexibility with deadlines, accommodating students’ distress. Challenges in online evaluation arose, affecting grades. Students reported varied evaluation methods. The 2020–2021 academic year saw improved organization and teaching quality in Zagreb. Overall, the pandemic caused confusion, fatigue, and pessimism, highlighting its profound impact on education.

Collectively, this discourse analysis encapsulates the intricate interplay of factors in the educational landscape during unprecedented times. It unravels the complex web woven by teachers’ adaptability, students’ resilience, and the evolving paradigms of teaching and learning in an era defined by the pandemic.

4.5 Structures, Services, and Policies for Teaching

The lockdown has clearly caused a rapid change in the functioning of HEIs. The structures, services such as the library for students and teachers, and policies regarding evaluation have been adapted to various degrees, but these have sometimes collapsed with the crisis situation. It seems that there were no initial guidelines for this new situation, and HEIs had to adapt in their own ways. We found that teachers in general have a common way of thinking. First, they organized lectures and their aim was not to lose contact with students. Second, they used the different services that the university provided, such as the digital library or virtual campus, which depend on different units in each university.

“We didn’t have any guidelines for the new situation, so we decided not to replicate the face-to-face teaching plan. Instead, we provided clear weekly work guidelines and held synchronous meetings once a week to address doubts. We aimed to maintain contact with students as a reference point and wanted them to have self-paced learning instructions to organize themselves. Therefore, we maintained a weekly synchronous session of an hour and a half.” [BA_10]

It was overwhelmingly observed that teachers universally aimed to maintain student engagement. They employed university-provided services like digital libraries and virtual campuses, tailored to each institution’s units. In Sofia, book deliveries through Biblio Car, daily consultations, and department head’s guidance were crucial in navigating the situation. Teachers shifted from replicating in-person teaching to offering structured weekly guidelines and synchronous sessions.

“The university library provided support to colleagues and students during the lockdown by giving access to necessary resources. Colleagues were able to request scanned parts of documents and students had access to various resources, including book deliveries through Biblio Car. Daily consultations were available as needed, and the department head sent regular letters with updates and instructions for quick and efficient communication.” [SO_1]

Students have different perceptions, and they use a combination of resources. They used commercial databases provided by their university but also looked for digital content online. This situation was similar for all partners.

“Well, I definitely think that digital materials that we use a lot now, especially those articles that we can find in databases, they somehow reduce the need to go to the library because you can actually find a lot of content online, for seminars and other things. I think that very often, before and during the pandemic, when I had seminars or presentations, I mostly looked for online sources instead of going to the library. And now I even look for a book or something online, so I mostly use digital materials.” [ZA_FG_1]

Since the lockdown situation was different in the various countries, this was reflected in the access to the library as well. And in some cases, students asked for an appointment. This situation was also explained by students from other universities.

“We could look for some articles in the beginning if we couldn’t access them from our devices from home and we could scan them. However, to do so you had to call, make an appointment and then you had to go and they would leave it at the library window. However, I personally did not use the library services at all during the whole time of the lockdown because everything we needed we either got through Moodle from the teacher or we found it ourselves in the online databases.” [OJ_FG_1]

The lockdown swiftly reshaped HEIs, affecting structures, services like libraries, and evaluation policies. Adaptations varied across institutions, with some struggling due to a lack of initial guidelines. Common teacher strategies emerged: maintaining contact, using university-provided services (like digital libraries), and setting clear guidelines for self-paced learning. Sofia introduced book deliveries via Biblio Car, while department heads played a pivotal role. Students utilized diverse resources, combining university databases and online content. Digital materials reduced library reliance, influenced by varying lockdown situations. Some accessed libraries by appointment, while others used Moodle and online databases for required materials during lockdowns.

4.6 Lessons Learned and Best Practices

Considering the circumstances of the crisis scenario, students and teachers considered that best practices in teaching were performed. The text presents insights into remote teaching and learning. For instance, it discusses adapting projects to online contexts and describes a successful virtual museum project. Lessons learned encompass improvements in student self-organization, enhancements in teachers’ digital skills, and the establishment of videoconferencing as a new norm. Students’ perspectives highlight the advantages of videos, podcasts, and recorded lectures, showcasing the adaptation of teaching methods for virtual environments. They also underscore adaptability and express appreciation for well-organized deadlines. Overall, the text showcases creative approaches to remote teaching, the evolution of practices, the value of hybrid models, and the importance of structured online learning. It delves into the challenges and opportunities arising from the transition to virtual education.

There were different activities that we considered as best practices, including online oral exams through videoconferencing tools, short quick quizzes, flexible organization of the timetables, certain activities, and also ways of delivering teaching. This was the case with the role-playing in Osijek, in which the students’ projects could be carried out in a virtual setting with role-playing gamification functionalities.

“And as for the advantages, I would mention these projects with students, we just had to tailor them to online circumstances. Although we couldn’t go to some bookstores or a publishing house to do a practical project. So we did some virtual projects that are very good. For example, a virtual museum of students and their works in publishing, where they were very engaged. We met in a virtual classroom on a weekly basis, talking about this project all year round and they did it. Some things turned out to be good, nice for them. I tried to make some sense of what they were doing, so when the course is over, they can have some result, something they can say ‘I did this’.” [OJ_2]

All the different partners had many thoughts on the lessons learned. These included the student’s shift to self-organization skills, the teacher’s improvement in digital skills, recognizing of the value of face-to-face teaching contact for certain activities, and videoconferencing as the new normal for meetings with students and mentoring.

In Zagreb, the blended and hybrid learning modes were highlighted as key players for the future of traditional face-to-face activities:

“I would definitely like teaching to be more hybrid, I have already said that, because I don’t think exclusively traditional teaching works anymore and students are asking for a lot more than that. Especially some types of students, like part-time or postgraduate students, so there is no need to bring them back and force them into something that actually suits them less.” [ZA_5]

Students had different views from the teachers and they found that creating videos and podcasts to facilitate the flipped classroom, promoting the creation and reuse of educational resources, and recording lectures for further clarification and reuse extended the scope of what is meant by recommended bibliography.

Students from Barcelona also found that videos and podcasts were useful for the flipped classroom.

“[Teacher X] used to make videos and in the end he stopped giving classes. He uploaded the videos to the campus and you had to watch the video by a particular day and do this questionnaire. Yes, …. So, for example, that seemed much more comfortable and good, and it wasn’t so tiring. We met once a week, I think, to discuss the subject and I think that’s the way to do it. And not to transfer everything that is face-to-face to the virtual, you have to adapt, both in terms of the means and the dynamics.” [BA_FG_1]

Students from Osijek found that a good practice was that deadlines were better organized and easy to follow. Online teaching and learning require better planning, defined deadlines, and milestones to ensure a more structured learning pace.

“In online classes, knowing that there’s a quiz each week at a certain time or that we have a certain deadline was much easier. Everything was synchronous with a defined schedule.” [OJ_FG_1]

In response to the crisis scenario, students and teachers adopted commendable teaching practices. These included online oral exams, quick quizzes, flexible timetables, and innovative teaching methods. Role-playing in Osijek showcased virtual project execution with gamification features. Advantages encompassed tailored virtual projects, improved self-organization for students, enhanced digital skills for teachers, and recognition of videoconferencing’s norm. Hybrid learning emerged vital in Zagreb, meeting diverse student needs. Videos, podcasts, and structured deadlines facilitated flipped classroom approaches, creating reusable educational content. Notably, a consensus emerged about the value of adaptability, emphasizing tailored approaches and structured scheduling in online education. The synthesis of best practices and lessons learned showcases the resilience and dynamism of educators and students amid the challenges posed by the crisis. These findings offer valuable insights for the future of education, advocating for hybrid models and personalized approaches to cater to diverse learning needs.

5 Discussion

This study explores the perceptions of teachers and students from the five European university LIS departments involved in the DECriS Project. Our findings reflect the different situations under which students and teachers were living during the pandemic and there were different circumstances that were challenging for them.

In relation to RQ1, our results indicate that there were different challenges. On the teachers’ side, the challenges included adapting to a new environment and being able to engage students in learning activities. The finding underscores the challenges teachers faced, transitioning to a new educational environment and fostering student engagement. To address this, institutions could offer training on effective online teaching strategies and encourage interactive learning methods to enhance student participation and comprehension. This also included the lack of privacy due to the use of private space and webcams for both teachers and students (Rajab, Soheib, Rajab, & Soheib, 2021). On the other hand, students had to quickly shift to the digital world and use technology effectively as it was supposed that they could do so (Kozimor, 2020; Rughoobur-Seetah, 2022). This observation highlights the swift adaptation of students to the digital realm, necessitating effective technology utilization. Institutions could offer digital literacy workshops to ensure students are equipped with the skills needed for efficient online learning. Furthermore, clear guidelines and resources can help bridge the gap for those less familiar with technology, fostering an inclusive learning environment.

Teachers had to transfer their lectures from face-to-face to the virtual environment (Bartusevičienė, Pazaver, & Kitada, 2021; Singh et al., 2022; Turnbull, Chugh, & Luck, 2021). This discovery underscores the challenging transition teachers faced in moving lectures from in-person to virtual platforms. To facilitate this shift, institutions could provide comprehensive training in online teaching methodologies, emphasizing the effective use of virtual tools and interactive strategies. Offering technical support and platforms with user-friendly interfaces would further aid educators in delivering engaging and impactful virtual lectures.

Both teachers and students also experienced work overload (Conrad et al., 2022; dos Santos, dos Silva, & Belmonte, 2021; Radovan & Makovec, 2022). The identified issue of work overload affecting both teachers and students highlights the need for balanced expectations. Institutions should set realistic workload guidelines for courses, ensuring manageable assignments and assessments. Encouraging effective time management skills and promoting communication between teachers and students can help prevent overwhelming workloads. Additionally, offering workshops on stress management and productivity strategies can equip individuals to handle their responsibilities more effectively while maintaining well-being.

Finally, we observed that health issues, such as burnout, loneliness, and even depression, emerged among both teachers and students (Gao & Sai, 2020; Raimondi, 2021). This finding underscores the critical issue of health concerns, encompassing burnout, loneliness, and depression among teachers and students. Institutions should prioritize well-being by offering mental health support services, promoting work-life balance, and encouraging open communication. Implementing regular check-ins, stress management resources, and fostering a supportive community can mitigate these challenges and create a more resilient learning environment.

In relation to RQ2, the performance among students varied depending on the partner institution. However, the use of digital infrastructure was commonly mentioned by all students. Having synchronous lectures seems to be a preference among all partners, and students appear to perform better with these. This finding emphasizes the significance of digital infrastructure in education. The preference for synchronous lectures and improved student performance suggests its effectiveness. Institutions should prioritize robust digital platforms, ensuring seamless connectivity and providing training for both teachers and students. To enhance learning outcomes, encourage interactive elements within synchronous sessions, such as Q&A sessions and collaborative activities. Furthermore, offering flexible attendance options and asynchronous access to recorded sessions can accommodate diverse learning preferences and schedules. This result is similar to the findings of Chisadza, Clance, Mthembu, Nicholls, and Yitbarek (2021), who found that students had a higher academic performance in live lectures than when they watched recorded lectures. First-year students seemed to have lower performance and poorer communication with their peers. This is translated to lower learning results than usual.

This outcome highlights the challenges faced by first-year students, manifesting as reduced performance and communication, leading to lower learning outcomes. Institutions should implement targeted support programs for first-year students, offering mentorship, study skills workshops, and social integration initiatives. Encouraging peer collaboration through online platforms, discussion forums, and virtual study groups can enhance engagement and foster a sense of belonging. Monitoring and intervention strategies should be established to identify struggling students early and provide personalized assistance to mitigate the negative impact on their learning journey. This finding is similar to a study carried out in Chinese universities, which found that studying from home or a boarding house had a direct correlation with lower grades (Li & Che, 2022).

In relation to RQ3, students and teachers generally indicated that their HEIs adapted their structures to their situations. Therefore, it can be observed that this adaptation was carried out at different levels. This insight highlights the adaptability of both students and teachers within their HEIs. Institutions should acknowledge this commendable flexibility by formalizing adaptable frameworks. Establishing clear communication channels and feedback mechanisms between administration, faculty, and students can further facilitate collaborative decision-making during uncertain times. Encourage the documentation and sharing of successful adaptation strategies within the institution, fostering a supportive learning community. Regular assessments of these adapted structures can provide insights for continuous improvement, ensuring that the institution remains resilient in the face of future challenges. This finding is similar to those of Boté-Vericad, Palacios-Rodríguez, Gorchs-Molist, and Cejudo-Llorente (2023) and Boté-Vericad (2021b), who found that teachers lacked training on how to adapt their teaching to the online situation.

Services, such as special book loans or facilitating electronic resources provided by the library, were helpful for students. This outcome highlights the positive impact of library services, such as special book loans and access to electronic resources. Institutions should continue and expand these services, considering a hybrid approach for the future. Enhance digital library platforms and ensure user-friendly interfaces for easy resource access. Regularly survey students to identify their evolving needs and preferences. Collaborate with librarians to provide guidance on effectively navigating digital resources. Additionally, establish a feedback mechanism to gather students’ input on the usefulness and accessibility of these services, enabling on-going improvements that align with students’ learning requirements. This finding is similar to those of a study performed in Zimbabwe, where the library played a key role in providing access to information resources. This situation helped the libraries to position themselves to support e-learning (Tsekea & Chigwada, 2020), although more capacity building would be necessary to transfer knowledge about training materials and courses (Boté-Vericad, 2022; Santos-Hermosa & Atenas, 2022). It also led to a high level of engagement from the teachers (Begum & Elahi, 2022).

In relation to RQ4, there were several lessons learned that are consistent with findings from other studies in the literature. First, universities have a significant social impact on students and teachers, and while the use of webcams may increase emotional expression, it does not necessarily enhance socialization (Yeung, Yau, & Lee, 2023). This finding underscores universities’ social influence on students and teachers. Although webcams may amplify emotional expression, they might not foster socialization. Institutions should prioritize holistic student support programs, focusing on social integration. Encourage interactive activities in virtual classrooms, such as group discussions and collaborative projects, to build meaningful connections. Implement regular virtual social events and networking opportunities to create a sense of community. Faculty development workshops can guide educators in creating inclusive online spaces that encourage active participation and peer engagement. A balanced approach to technology use can enrich emotional connections and interpersonal relationships.

Second, some teachers implemented innovative teaching methods, such as the use of videos and podcasts, which were particularly useful for students who were unable to attend synchronous lectures (Mayo-Cubero, 2021; Tuma, Stanley, & Stansbie, 2020). These finding highlights teachers’ adoption of innovative methods like videos and podcasts, aiding students unable to attend synchronous lectures. Encourage educators to diversify instructional strategies, offering various formats for content delivery. Develop comprehensive guidelines and training resources on creating effective educational videos and podcasts. Implement accessibility measures to ensure all students benefit from these resources. Encourage teachers to provide supplementary materials to reinforce learning, accommodating different learning styles and schedules. Regularly gather feedback from students to refine and enhance the quality and accessibility of these materials, ensuring a well-rounded and inclusive learning experience.

Videos and podcasts were useful for students if they could not attend synchronous lectures (Almendingen, Morseth, Gjølstad, Brevik, & Tørris, 2021; Chen, Ayoob, Desser, & Khurana, 2022; Rapanta, Botturi, Goodyear, Guàrdia, & Koole, 2020). This outcome highlights the value of videos and podcasts for students who miss synchronous lectures. Institutions should emphasize the creation of high-quality video and podcast content, ensuring clear and concise delivery of key concepts. Develop a centralized repository for these resources, organized by subject and topic, for easy access. Offer guidelines on effective note-taking techniques for these asynchronous materials to enhance comprehension. Encourage teachers to incorporate interactive elements, like quizzes or reflection questions, within the videos or podcasts to maintain student engagement and promote active learning. Regularly assess the effectiveness and relevance of these resources through student feedback for on-going improvement.

However, some teachers faced initial limitations in creating educational videos (Boté-Vericad, 2020, 2021b). This finding underscores the initial challenges some teachers encountered when creating educational videos. Institutions should provide comprehensive training in video creation, covering technical skills and pedagogical strategies. Offer dedicated support, including technical assistance and access to video editing tools. Encourage collaboration among teachers, facilitating knowledge sharing and best practices. Develop a library of resources, such as tutorials and templates, to expedite video creation. Regularly assess teachers’ progress and address concerns promptly. Emphasize a growth mindset, encouraging continuous improvement and experimentation. Recognize and celebrate teachers’ efforts in adapting to new methods, fostering a culture of innovation and resilience.

It also seems that with the synchronous mode, students are better able to organize their schedules and deliver tasks more efficiently (Sanoto, 2021). This result indicates that synchronous mode benefits students’ schedule organization and task efficiency. Institutions should encourage teachers to maintain synchronous components in their courses. Provide guidelines for structuring synchronous sessions, ensuring clear objectives and interactive elements. Advocate for transparent communication of session timings to help students plan effectively. Offer resources on time management techniques, aiding students in optimizing their schedules. Implement periodic assessments to gauge the impact of synchronous sessions on learning outcomes and time management skills. Encourage teachers to create opportunities for active engagement during these sessions, fostering a productive and participatory learning environment.

Finally, all participants in this study mentioned the pros and cons of the different modes of teaching/learning, which could be considered by HEIs in the future. This finding highlights the unanimous mention of the convenience of a more flexible approach with a complement of blended and hybrid teaching to pure face to face. Institutions should actively explore hybrid and blended models for the future. Design workshops to guide teachers in creating effective hybrid courses, balancing in-person and online components. Develop a flexible scheduling system that accommodates both virtual and physical interactions. Establish a feedback loop with students and faculty to continuously refine teaching approaches based on their experiences. Prioritize investments in technology infrastructure to support seamless integration of virtual and in-person activities.

6 Conclusion and Limitations

We conclude that although the COVID-19 lockdown was a crisis situation, many positive aspects can be highlighted in the field of higher education. HEIs shifted to the digital mode at different levels and speeds. Teachers and students had to adapt their personal and professional situations to the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a diversity of positive aspects, including better practices in teaching, innovation, and improved use of digital skills by students and teachers.

The study reveals diverse situations among partners during the pandemic. Teachers adapted differently, influenced by prior experience. Personal limitations and challenges emerged, as exemplified by the teacher’s concerns about equipment. Students emphasized social connections, using WhatsApp groups. In most cases, the centres showed varied approaches to synchronous lectures, highlighting student preferences. The pandemic’s effects on academic performance were evident, with flexible deadlines offered by teachers. Online evaluation issues impacted grades. Library services and structures were adjusted, with digital resources gaining importance. Lessons learned include self-organization skills for students, digital competence for teachers, and the value of blended learning. Videoconferencing emerged as a new norm for meetings. Hybrid learning was seen as the future in certain situations, while videos and podcasts aided flipped classroom approaches. Structured deadlines and planning were noted as beneficial for online teaching and learning. The findings underscore the complexities of adapting to remote education, emphasizing the need for tailored approaches and careful planning.

Several proposals are recommended to enhance information policies and elevate academic library services, alongside fostering digital literacy among teachers and students. First, institutions should develop comprehensive information policies that prioritize open access to digital resources, ensuring equitable access for all. Second, academic libraries should embrace technological advancements by offering personalized digital resources and collaborative platforms, catering to diverse learning needs. Additionally, embedding digital literacy programs within the curriculum can empower educators and learners to navigate the evolving digital landscape effectively. Moreover, continuous training initiatives for both teachers and students will ensure adeptness in utilizing digital tools for research and learning. Collaborative efforts between institutions, libraries, and educators will establish a robust foundation for embracing the digital age in higher education.

This study has various limitations. It was carried out in five LIS departments from four European countries and represents a partial view of other LIS departments around the world. Although all researchers in this study have tried to communicate their situation in their corresponding HEIs as best they can, some situations during the research process could have been missed or biased.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the DECriS project teams for the realization of the interviews and focus groups. We also thank the support from the DECriS project coordinators, Tatjana Aparac-Jelušić and Boris Bosančić from the University of Osijek (Croatia).

-

Funding information: This article is an outcome from the ERASMUS + Project DECriS “Digital Education for Crisis Situations: Times When There is no Alternative.” Contract Number: 2020-1- HR01-KA226-HE-094685. The European Commission support for producing this publication does not constitute endorsement of the contents, which only reflect the views of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained in this article.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Juan-José Boté-Vericad, Cristóbal Urbano, Sílvia Argudo, Gema Santos-Hermosa. Methodology: Juan-José Boté-Vericad, Cristóbal Urbano. Data curation: Juan-José Boté-Vericad. Transcription and data analysis country by country: Juan-José Boté-Vericad, Sílvia Argudo, Stefan Dreisiebner, Kristina Feldvari, Sandra Kucina Softic, Tania Todorova. Integrated data analysis: Juan-José Boté-Vericad, Cristóbal Urbano. Writing – original draft: Juan-José Boté-Vericad, Cristóbal Urbano. Writing – review & editing: Juan-José Boté-Vericad, Cristóbal Urbano, Sílvia Argudo, Stefan Dreisiebner, Kristina Feldvari, Sandra Kucina Softic, Gema Santos-Hermosa, Tania Todorova.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The complete research report with the analysis of a comprehensive selection of the anonymized transcriptions, country by country, will be available at the end of the project at the official website: https://decris.ffos.hr/intellectual-outputs/o2.

References

Almendingen, K., Morseth, M. S., Gjølstad, E., Brevik, A., & Tørris, C. (2021). Student’s experiences with online teaching following COVID-19 lockdown: A mixed methods explorative study. PLOS ONE, 16(8), e0250378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250378.Suche in Google Scholar

Almusharraf, N., & Khahro, S. (2020). Students satisfaction with online learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (IJET), 15(21), 246–267.10.3991/ijet.v15i21.15647Suche in Google Scholar