Abstract

Objectives

Orbital mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma with amyloidosis is an uncommon condition. This study presents three cases of this rare disease, to provide insights into its clinical manifestation, clinicopathological features, treatment options, and prognosis.

Case presentation

This study reports three cases of orbital MALT lymphoma with amyloidosis. All patients exhibited proptosis, and imaging findings revealed orbital masses. Furthermore, two cases were potentially associated with IgG4-related ophthalmic disease. The diagnosis of all patients was confirmed via immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of the biopsy samples. One patient exhibited space-occupying lesions in the lungs and kidneys. In addition, one patient underwent orbital radiotherapy, and a 1-year follow-up revealed a reduction in the orbital mass volume. Another patient underwent systemic chemotherapy, but imaging at the eight-month follow-up revealed no substantial changes in the orbital or systemic lesions.

Conclusions

The coexistence of orbital MALT lymphoma and amyloidosis presents diagnostic challenges because of its rarity and the involvement of two distinct conditions. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a key tool for establishing a definitive diagnosis. Surgery is the most commonly employed treatment method. Although it does not provide a definitive cure, the primary importance lies in obtaining biopsy samples for precise diagnosis and reducing the tumor burden to alleviate the mass effects. Orbital radiotherapy remains a key treatment option. However, in cases with systemic involvement, systemic chemotherapy or alternative therapies may be prioritized to manage systemic symptoms effectively.

Introduction

Ocular adnexal lymphoma (OAL) is the most prevalent primary orbital malignancy in adults, with extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) accounting for 70–80 % of OAL cases [1], [2], [3].

Amyloidosis is a disorder of protein metabolism characterized by the deposition of insoluble and misfolded proteins in the extracellular spaces of various organs and tissues [4], resulting in the destruction and damage of organ structures and functional damage. The occurrence of amyloid in the eyes and ocular adnexal structures has been well documented, but it remains uncommon [5]. The most common clinical signs of these conditions include visible or palpable periocular mass or tissue infiltration, ptosis, tissue infiltration, proptosis, globe displacement, limitation in ocular motility, and recurrent subconjunctival hemorrhages [5], [6], [7]. Orbital MALT lymphoma with amyloidosis is a rare condition. Thus, an understanding of the clinical presentation, clinicopathologic features, treatment strategies, and prognosis of this condition is essential.

The neoplastic cells in MALT lymphoma typically exhibit the immunophenotype of post–germinal center B cells and/or plasma cells [8]. In addition, a localized B-cell clone plays a key role in the progression of amyloidosis [9]. These factors may contribute to the coexistence of both diseases.

This study presents three rare cases of coexisting orbital MALT lymphoma with localized amyloidosis. Notably, two of these cases are also associated with IgG4-related ophthalmic disease (IgG4-ROD). A literature review of orbital MALT lymphoma with localized amyloidosis was conducted and summarized.

Case description

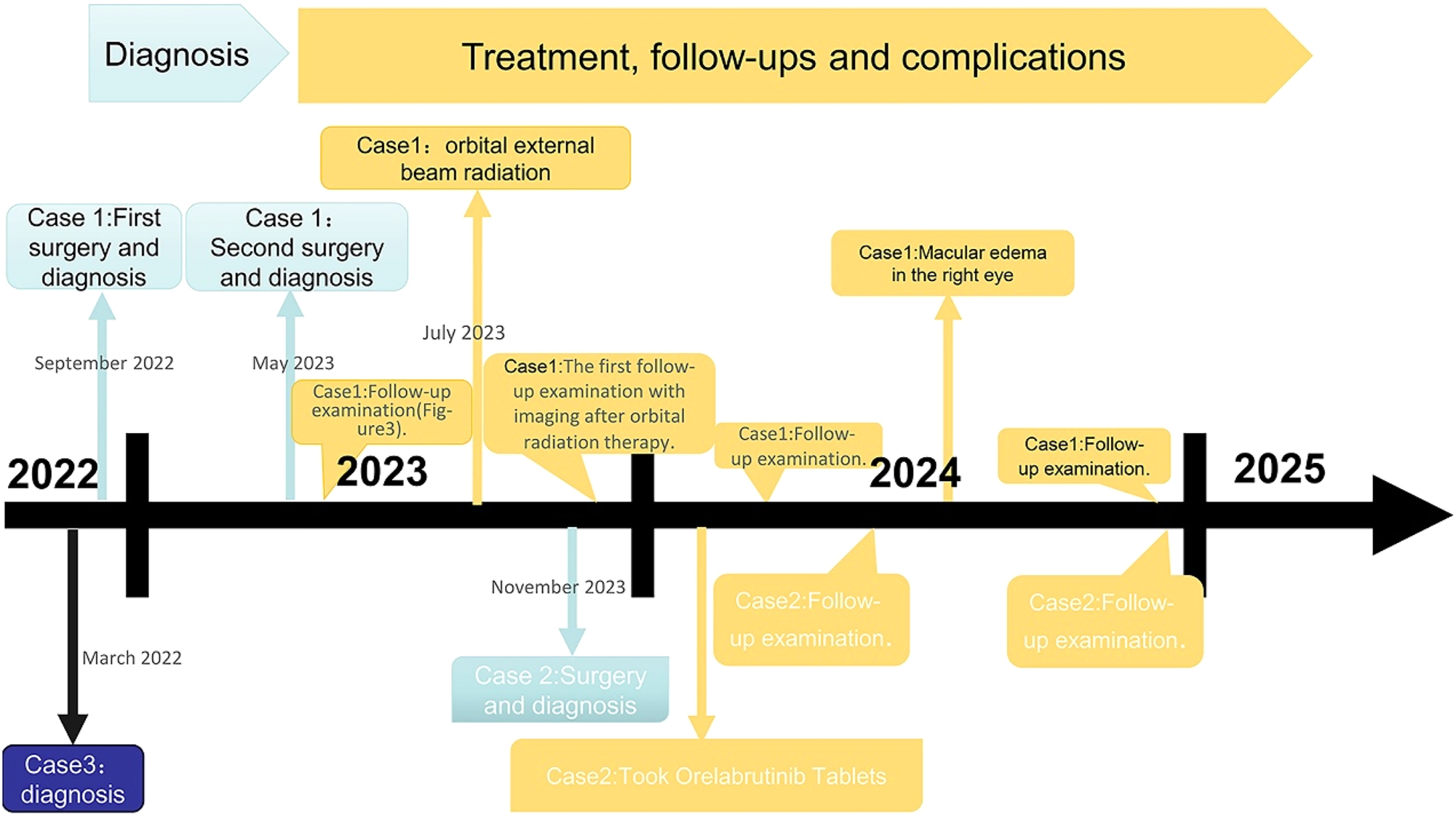

Three cases of orbital MALT lymphoma with localized amyloidosis recorded in the databases of the Ophthalmology and Pathology Departments of West China Hospital of Sichuan University from 2022 to 2025 were reviewed (Figure 1). This study was conducted considering ethical responsibilities according to the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (NO. 2025-494). The handwritten informed consent was obtained from the patients.

The timelines for three patients include the process of diagnosis, treatment, and follow-ups.

Case 1

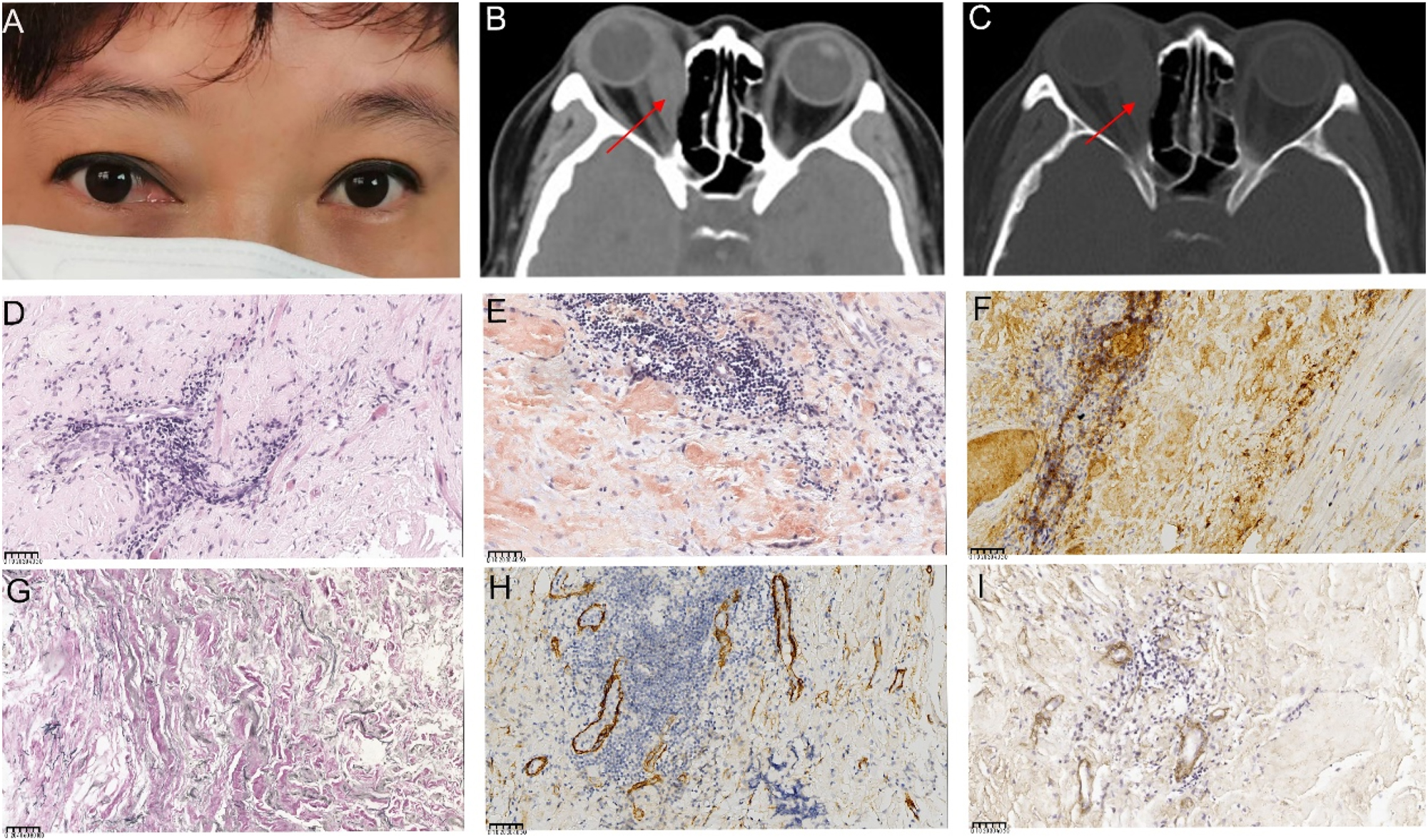

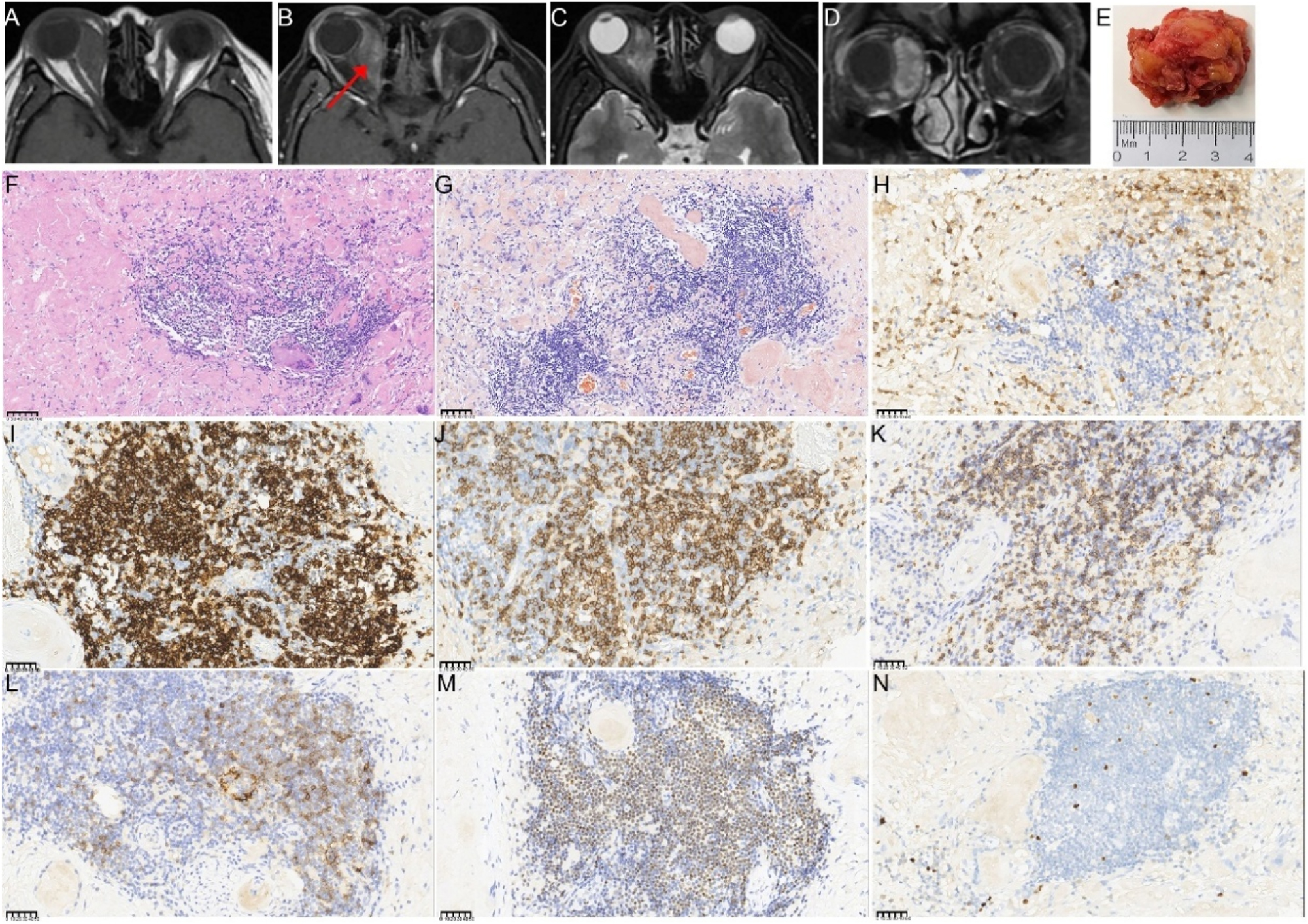

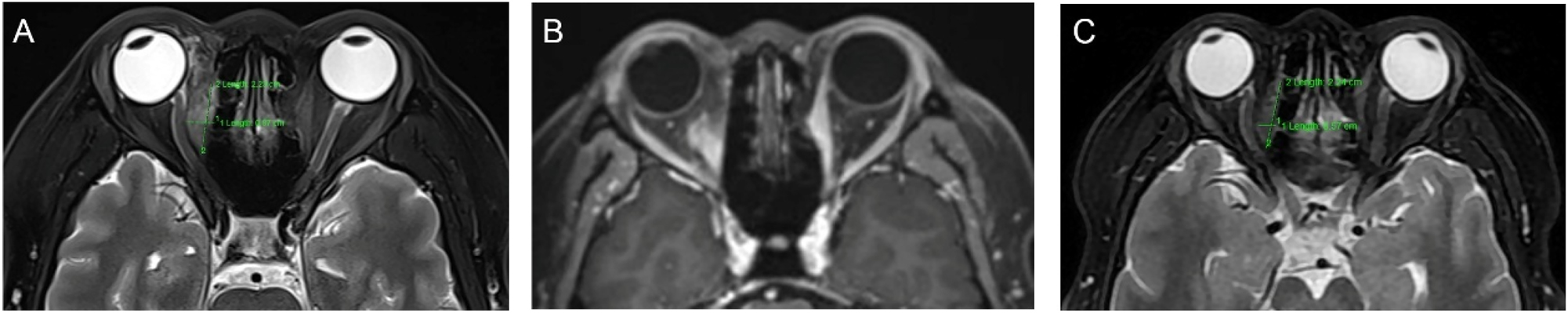

A 41-year-old woman presented with a 1-year history of right eye proptosis and restricted ocular motility. The patient’s visual acuity was 20/40 in both eyes, and the right eye exhibited pronounced proptosis, limited motility in horizontal directions, and bulbar conjunctival congestion and edema (Figure 2A). Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed fusiform enlargement of the right medial rectus muscle, whereas the tendons remained unaffected (Figure 2B and C). The pathological diagnosis indicated amyloidosis, with a significant increase in IgG4-positive cells (Figure 2D–I). The patient’s recent serum IgG4 level was 0.944 g/L, which was within the reference range of 0.03–2.01 g/L. The patient did not undergo any treatment regimen and was advised to attend regular follow-ups. One year later, the patient exhibited further enlargement of the medial rectus muscle of the right eye (Figure 2A), accompanied by a decline in visual acuity to 20/50 in the affected eye. Orbital contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an enlarged medial rectus muscle in the right eye with mixed intensity, and the maximum cross-sectional area of the tumor was approximately 2.92×1.43 cm (Figure 3A–D). A second surgical procedure was necessary, and the resected specimen appeared as hard, brittle, yellow-white masses (Figure 3E). Immunohistochemical staining (IHC staining) revealed 0–90 IgG4+cells per high-power field (HPF) in the lesion (Figure 3H). IHC staining confirmed MALT lymphoma, showing positive expression for CD20, CD3, CD5 (Figure 3I–M) and CD23 (FDC), and negative expression for CD10, Cyclin D1, CD1a, ALK, S100, Langerin, and BRAF V600E. Ki-67 staining indicated a low proliferative index of 5–10 % (Figure 3N). No clonal IgH and IgK rearrangements were detected. In addition, her serum IgG4 levels were within the normal range. Whole-body imaging revealed no signs of systemic disease. Consequently, a definitive diagnosis of orbital MALT lymphoma with primary amyloidosis was established. The patient underwent successful treatment with three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3DCRT), with a total dose of 30 Gy administered in 10 fractions using 6 MV photons. Follow-up orbital MRI one year later showed a significant reduction in tumor size, with the maximum cross-sectional area decreasing from 2.3×0.8 cm–2.3×0.57 cm (Figure 4A–C). However, fundus examination revealed macular edema in the right eye, for which the patient received a Dexamethasone Intravitreal implant (Ozurdex, Allergan Pharmaceuticals, Ireland). This condition may be a side effect of radiotherapy, and the patient remains under ongoing follow-up.

Ocular appearance, orbital imaging, and pathological images of the lesion specimen in the first surgery (A) Reoperative image showing proptosis along with congestion and edema of the medial bulbar conjunctiva in the right eye (B, C) computed tomography (CT) images show significant thickening and a clump-like appearance of the right medial rectus muscle, with slight calcification in the lower part. The right ethmoid sinus wall appears compressed and thinned. The red arrows indicate the right enlargement of the medial rectus muscle (D, E) pathological images of the specimen (D) high magnification showing muscle and fibroadipose tissue with interstitial lymphocytic infiltration (hematoxylin and eosin (HE) 400×), (E) Congo red staining of the orbital lesion, demonstrating a positive result under microscopy at 400× (F) HC staining shows over 40 IgG4+cells per high-powered field (HPF) in the lesion (400×) (G) positive elastic fiber immunostaining of lesion cells (200×) (H) Partial positive smooth muscle actin immunostaining of lesion cells (400×) (I) partial positive IV collagen fiber immunostaining of lesion cells (400×). The unit of scale bar is μm.

The orbital imaging, gross specimen, and pathological images of the lesion specimen in the second surgery (A–D) preoperative enhanced MRI of the orbit before the second surgery. The right retrobulbar lesions appear hyperintense with uneven enhancement on contrast imaging, surrounding the right optic nerve and right eyeball. The red arrows indicate the right enlargement of the medial rectus muscle (E) gross appearance of the resected tumor, which was whitish, hard, and measured approximately 3.5×3×1.5 cm in total volume (F–N) histopathological findings from the second surgery (F) lower magnification showing amyloidosis with a foreign body reaction and focal lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration (HE; 200×) (G) Congo red staining of the orbital lesion demonstrates a positive result under microscopy at 400×magnification (H) IHC staining for IgG (400×), showing infiltration of a few IgG4-positive plasma cells (I) partial positive CD 20 immunostaining of tumor cells (400×) (J) Partial positive CD3 immunostaining of tumor cells (400×) (K) Partial positive cytoplasmic CD5 immunostaining of tumor cells (400×) (L) A few tumor cells showed positive CD23 immunostaining of tumor cells (400×) (M) Partial positive OCT2 immunostaining of tumor cells (400×) (N) Ki67 immunostaining demonstrates strong nuclear immunoreactivity in approximately 5–10 % of tumor cells (400×). The unit of scale bar is μm.

Orbital imaging of the lesion after the second surgery (A, B) enhanced MRI of the orbit 2 weeks after the second surgery shows a significant reduction in lesion size compared with the preoperative size. The maximum cross-sectional area of the tumor measured approximately 2.3×0.8 cm (C) Enhanced MRI of the orbit 6 months after radiotherapy, demonstrating further tumor shrinkage, with a maximum cross-sectional area of approximately 2.3×0.57 cm.

Case 2

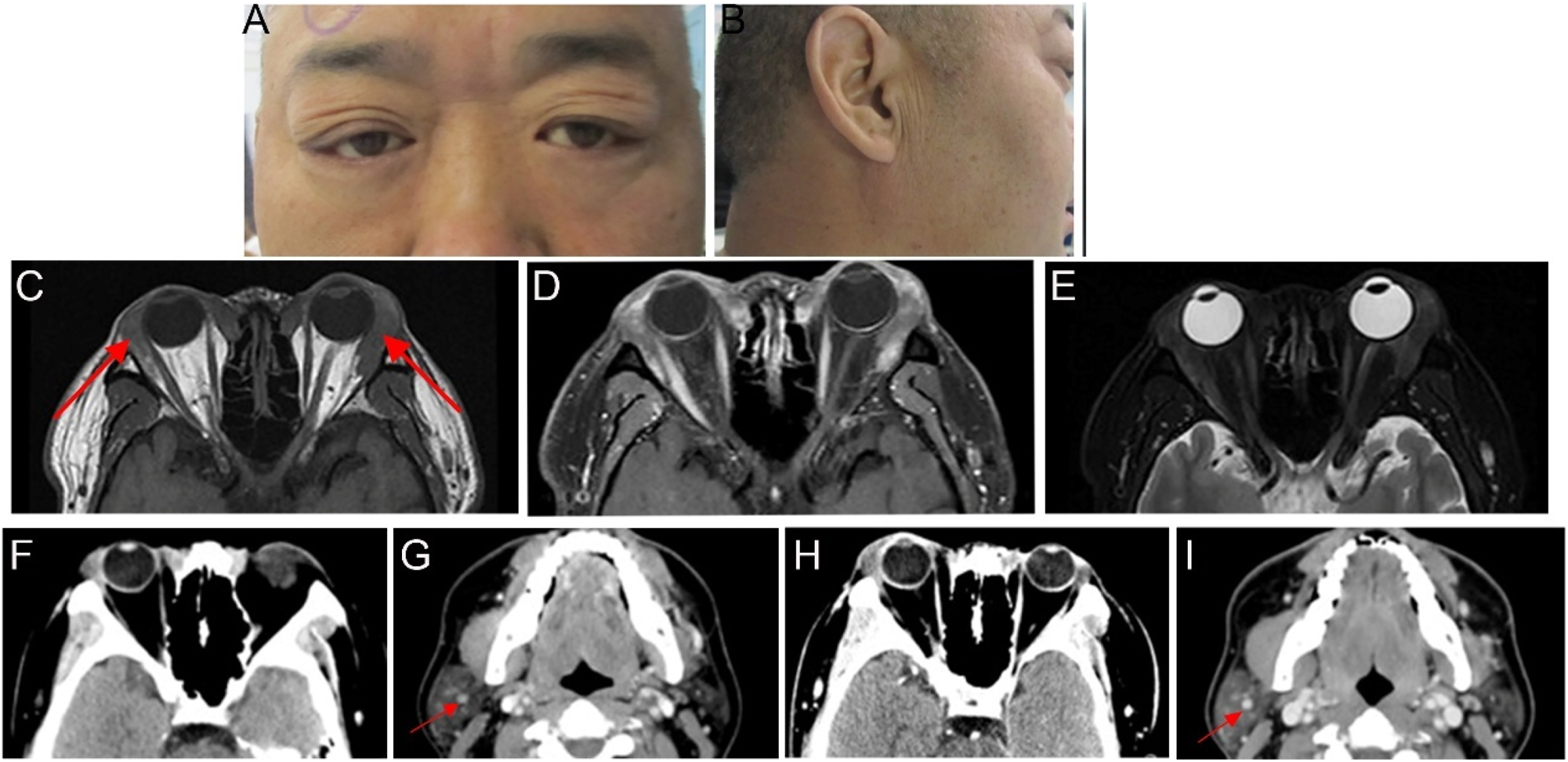

A 48-year-old man presented with bilateral upper-eyelid swelling for 2 years which was accompanied by occasional lacrimation. The medical history of the patient included chronic viral hepatitis C. Six months earlier, he had undergone surgery at another hospital, where his pathological diagnosis was confirmed as amyloidosis. Ophthalmologic examination revealed a visual acuity of 20/20. The swelling was observed on the lateral side of the upper eyelids, along with enlargement of the lacrimal glands in both eyes (Figure 5A). The rest of the ophthalmic examination findings were normal. Furthermore, significant enlargement of his bilateral parotid gland was observed (Figure 5B). Orbital contrast-enhanced MRI revealed bilateral lacrimal gland lesions with intense signal enhancement, with the maximum cross-sectional area measuring approximately 3.2×1.7 cm (Figure 5C–E). The patient underwent bilateral anterior orbitotomy with a biopsy of the bilateral lacrimal gland for histopathologic evaluation. The biopsy specimens revealed extensive pink amorphous deposits accompanied by a multinucleated giant cell reaction and focal interglandular lymphocyte infiltration. IHC staining confirmed MALT lymphoma, showing positive expression for CD20, CD30, and CD138 (plasma, +) and negative expression for IgG4. However, the patient’s recent serum IgG4 level was 2.02 g/L, exceeding the reference range of 0.03–1.500 g/L. A comprehensive evaluation, including radiological imaging of the head, abdomen, and thorax, detected no additional lesions, except for multiple nodules in the parotid gland, kidneys, and lungs (Figure 5F and G). The patient was diagnosed with MALT lymphoma with secondary amyloidosis and was subsequently referred to the hematology department. He received six treatment courses of Orelabrutinib Tablets (150 mg qid; Innocare, China) as the primary therapy. Follow-up imaging performed 3 months after discontinuing the medication revealed no signs of recurrence (Figure 5H and I).

Ocular appearance and imaging of the patients (A, B) preoperative images show swelling of the outer upper eyelids bilaterally and enlargement of the right parotid gland (C–E) imaging was performed approximately 2 months before the surgery. The red arrows indicate bilateral enlargement of the lacrimal glands. Orbital MRI revealed bilateral hypertrophy of the lacrimal glands. The bilateral lesions appeared slightly isointense on T1-weighted imaging, with uneven T2 signals and heterogeneous contrast enhancement. The boundary between the lesion and the medial rectus muscle was not clear (F–I) imaging of head CT. The red arrows indicate calcified lesions in the parotid gland (F, G) orbital CT revealed bilateral enlargement of the lacrimal glands, which was more pronounced on the right side. Head CT revealed nodules in the superficial lobe of the right parotid gland, with partial and punctate calcifications in the submandibular gland (H, I) CT scan performed 3 months after discontinuing medication demonstrated that the lesion characteristics remained consistent with previous findings.

Case 3

A 58-year-old man sought medical attention due to right-sided vision impairment persisting for a year and proptosis for the past 9 months. An ophthalmologic evaluation revealed a visual acuity of 20/50 in both eyes, along with proptosis, restricted eye movements in supravergence, and lens opacity in the right eye. Orbital contrast-enhanced MRI showed significant thickening of the right superior rectus muscle, with the tumor’s maximum cross-sectional area measuring 3.0×2.1 cm. Histopathological analysis revealed extensive extracellular, eosinophilic material, which tested positive with Congo red staining. IHC staining confirmed MALT lymphoma, showing positive expression for CD20, CD79a, bcl12, CD43, and CD23, indicating the presence of follicular dendritic cells (FDC). The lesion tested negative for CD3, CD5, CD23, CD10, bcl6, bcl12, CyclinD1, and IgG4. A cytogenetic analysis of the right eye lesion revealed clonal amplification peaks in IgH and IgK. Whole-body imaging showed no evidence of systemic disease. Based on the combined clinical presentation, imaging findings, and histopathological analysis, a diagnosis of orbital MALT lymphoma and amyloidosis was established. However, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Orbital MALT lymphoma with amyloidosis is an exceptionally rare condition. To date, only a few cases involving the ocular adnexal have been reported in the literature [10], [11], [12]. The age of the affected patients ranged from 33 to 82 years, with a median age of 63.5 years. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics and ophthalmologic findings of ocular MALT lymphoma with amyloidosis.

Ophthalmologic findings and clinical characteristics of ocular MALT with amyloidosis.

| Sex/Age at diagnosis | Other disorders | Ocular site | Additional sites involved | MALT immune-subtype | Treatment | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female/57 [4] | No | Right lacrimal gland | NO | IGH | XRT | EMZL relapse in the right lacrimal gland after treatment for 10 months. |

| Male/33 [11] | No | Ocular adnexa | / | / | XRT and rituximab | Alive with diseases for 2 years |

| Male/73 [12] | / | Right orbit | Jaw, lung | IgG | XRT | Alive with diseases for 7 years |

| Male/82 [10] | / | Subconjunctival | / | / | Declined | Alive with disease |

| Female/72 [13] | Sjögren syndrome discoid lupus; rheumatoid arthritis | Ocular adnexa | Stomach | IgG λ | XRT | Amyloid relapse in the stomach after treatment for 14 months and follow-up for 2 years, and alive with no evidence of disease |

| Female/44 [13] | Chronic blepharitis | Ocular adnexa | Salivary gland, soft tissues | IgG λ | XRT | Follow-up for 12 years and alive with no evidence of disease |

| Female/76 [13] | Mild allergies | Ocular adnexa | Larynx | IgA κ | XRT | Follow-up for 6 years and alive with disease |

| Female/74 [26] | No | Orbit | NO | / | Declined | / |

| Male/61 [31] | / | Orbit | / | / | XRT | Amyloid only |

| Female/72 [32] | No | Lacrimal gland | / | Ig light | XRT | / |

-

XRT, external beam radiation therapy; EMZL, extranodal marginal zone lymphoma.

Orbital MALT lymphoma typically presents as a nonspecific mass that requires biopsy for definitive diagnosis. In addition, OAL can develop in the conjunctiva, eyelids, orbit, or lacrimal gland [8], often manifesting as a gradually enlarging, painless mass that leads to proptosis. HE staining revealed that the neoplastic cells exhibited a range of morphological features, including bland small lymphocytes, small to medium-sized marginal zone cells, monocytoid B cells with abundant pale cytoplasm, and plasma cells [13], 14]. In IHC staining, neoplastic B cells typically show positive expression of CD20 and CD5 but negative expression of CD10, CD23, and cyclin D1 [13], 14]. Clinically, amyloidosis is categorized as a localized condition or a systemic disease affecting multiple organs, with systemic amyloidosis generally associated with a poorer prognosis [15]. Only 4 % of localized amyloidosis cases occur in the eye socket and mainly involve the eyelids and conjunctiva [6], and lacrimal and/or extraocular muscle involvement is rare [16]. The diagnosis of localized amyloidosis is typically based on the presence of extracellular deposits of amorphous material, which exhibit characteristic Congo red staining and apple-green birefringence under polarized light microscopy [2], 13], 17]. Two patients (case 1 and case 2) in this study initially presented with ocular symptoms, were diagnosed through IHC staining, and had follow-up records extending for 1–2 years. All three patients (case 1, 2, and 3) underwent a comprehensive evaluation of imaging, and secondary systemic lesions were identified case 2, which suggests the necessity for systemic screening in patients with localized amyloidosis [18].

Localized amyloid deposition primarily consists of immunoglobulin light chains, potentially originating from a focal clone of monoclonal B cells or plasma cells [15]. Although the exact cause remains unclear, it may be associated with local epithelial infection or inflammation, triggering oligoclonal or low-grade monoclonal immunoglobulin production [13], 15]. MALT lymphoma, which arises from neoplastic B cells [1], is closely associated with infection and inflammation [8]. This association indicates that the inflammatory environment created by amyloid deposition may contribute to the development of lymphoma. Consequently, this may explain why case 1 and case 2 were first diagnosed with orbital amyloidosis before subsequently being identified with orbital amyloidosis with MALT lymphoma. An alternative perspective suggests that amyloidosis could be a complication of MALT lymphoma [19]. The recurrence of amyloid and/or development of MALT lymphoma in the lung or other sites in almost half of the 18 nodular pulmonary amyloidosis (NPA) patients indicates a potential triadic relationship between NPA, systemic syndromes, and MALT lymphoma [19]. It is also possible that both diseases develop simultaneously without a distinct sequence of occurrence. This highlights the importance of thorough evaluation to exclude systemic involvement or associated underlying lymphoproliferative disorder in amyloid deposits [20].

In addition, case 1 and case 2 indicate a potential association between MALT lymphoma and IgG4-related disease. Notably, case 2 exhibited elevated serum IgG4 levels, whereas histopathological analysis in case 1 revealed a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with more than 10–50 IgG4-positive plasma cells per HPF. Thus, case 1 and case 2 may have an association with IgG4-ROD. A clinical study reported that 13 of 30 patients with MALT lymphoma exhibited IgG4-positive plasma cells [21]. The presence of IgG4-positive cells in the microenvironment may contribute to the proliferation of neoplastic B-lymphocytes, facilitating genetic abnormalities and tumor progression [8], 22].

Radiotherapy remains the most widely used treatment for MALT lymphoma [8], 23]. Historically, patients with OAL have been treated with moderate-to-high radiation doses, typically ranging from 25 to 54 Gy, achieving excellent local control rates of 90–100 % [1], 8]. For localized amyloidosis, management options range from observation to localized surgical interventions [7], 15], 24]. There is no proven role for radiotherapy or chemotherapy in the routine management of these patients, although certain severe presentations (e.g. unresectable airway obstruction) may justify a trial of local radiotherapy [15], 24], 25]. In more severe orbital cases, local radiotherapy may be employed to target B cells involved in amyloid light chain deposition, demonstrating effectiveness in controlling disease progression [11], 15], 25]. Basset et al. highlighted the effectiveness of radiotherapy, particularly when combined with surgical debulking [9]. Among the reported cases, seven underwent surgical resection followed by postoperative radiotherapy, while two received systemic chemotherapy. However, two of the nine patients declined treatment [10], 26]. Based on existing literature, all reported patients have survived, indicating that treatment options can be tailored accordingly [11], [12], [13]. In case 1, orbital external radiotherapy was chosen due to the presence of a localized mass, which is consistent with previous reports [4], 11], 27]. However, case 2 involved secondary kidney and lung lesions, and systemic therapy with – Orelabrutinib was initially recommended. Although the prognosis of localized amyloidosis is generally favorable, patients with localized lung amyloidosis tend to have poorer survival outcomes [28]. Imaging findings indicated potential involvement of the lung bronchi and kidney. Given the need to manage systemic diseases, a systemic treatment approach was selected as the primary course of action [29]. Yazici et al. proposed that radiotherapy is crucial for managing indolent ocular adnexal and orbital lymphomas, and combining it with systemic therapies does not improve outcomes in early-stage cases [30]. However, we emphasize that physicians should consider systematic involvement and molecular findings when selecting monoclonal antibody treatments. The management of orbital MALT lymphoma with amyloidosis requires a tailored treatment strategy with regular monitoring and follow-up to evaluate the therapeutic response and promptly detect any recurrence or disease progression.

In summary, three cases of orbital amyloidosis with MALT lymphoma were presented, with two cases also exhibiting coexisting IgG-ROD. Amyloidosis and IgG4-positive cells may contribute to an inflammatory microenvironment that supports MALT development, potentially influencing the onset and progression of both conditions. Persistent inflammation can drive immune cell proliferation and, in some cases, lead to the formation of localized lymphomas [8]. Therefore, routine immunohistochemical analysis is recommended for cases of orbital amyloidosis, particularly when HE staining reveals extensive lymphocytic infiltration or if the mass continues to progress.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients who agreed to be included in this study.

-

Research ethics: This study was conducted considering ethical responsibilities according to the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (NO. 2025-494).

-

Informed consent: The handwritten informed consent was obtained from the patients.

-

Author contributions: Huirun Zeng: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, writing original draft and review and editing, Yujiao Wang: investigation, review and editing, Weimin He: surgery, conceptualization, supervision, review, and editing.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI, and Machine Learning Tools: Not applicable.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

Research funding: Not applicable.

-

Data availability: This study has no additional data. All available data and materials have been shared within the case report.

References

1. Yen, MT, Bilyk, JR, Wladis, EJ, Bradley, EA, Mawn, LA. Treatments for ocular adnexal lymphoma. Ophthalmology 2018;125:127–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.037.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Boltezar, L, Strbac, D, Pizem, J, Hawlina, G. Ocular adnexal lymphoma – a retrospective study and review of the literature. Radiol Oncol 2024;58:416–24. https://doi.org/10.2478/raon-2024-0048.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Kalogeropoulos, D, Papoudou-Bai, A, Kanavaros, P, Kalogeropoulos, C. Ocular adnexal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Clin Exp Med 2018;18:151–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-017-0474-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Chean, CS, Sovani, V, Boden, A, Knapp, C. Lacrimal gland extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma in the presence of amyloidosis. Orbit 2022;41:350–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2020.1852578.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Jamshidi, P, Levi, J, Suarez, MJ, Rivera, R, Mahoney, N, Eberhart, CG, et al.. Clinicopathologic and proteomic analysis of amyloidomas involving the ocular surface and adnexa. Am J Clin Pathol 2022;157:620–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqab161.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Li, J, Liu, R, Ren, T, Wang, N, Guo, Q, Xu, L, et al.. Clinical analysis of 37 Chinese patients with ocular amyloidosis: a single center study. BMC Ophthalmol 2024;24:294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-024-03548-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Banerjee, P, Alam, MS, Subramanian, N, Kundu, D, Koka, K, Poonam, NS, et al.. Orbital and adnexal amyloidosis: thirty years experience at a tertiary eye care center. Indian J Ophthalmol 2021;69:1161–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.ijo_2528_20.Search in Google Scholar

8. Olsen, TG, Heegaard, S. Orbital lymphoma. Surv Ophthalmol 2019;64:45–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.08.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Basset, M, Hummedah, K, Kimmich, C, Veelken, K, Dittrich, T, Brandelik, S, et al.. Localized immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis: novel insights including prognostic factors for local progression. Am J Hematol 2020;95:1158–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.25915.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Müller, PL, Loeffler, KU, Holz, FG, Fischer, H-P, Herwig, MC. Lachsfarbener Bindehauttumor mit Amyloidablagerung. Die Ophthalmologe 2016;113:602–5.10.1007/s00347-015-0130-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Bruce, CN, Kroft, SH, Harris, GJ. Orbital MALT lymphoma with amyloid deposition. Orbit 2024;43:526–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2023.2203750.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Zhang, Q, Pocrnich, C, Kurian, A, Hahn, AF, Howlett, C, Shepherd, J, et al.. Amyloid deposition in extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: a clinicopathologic study of 5 cases. Pathol Res Pract 2016;212:185–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2015.08.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Ryan, RJH, Sloan, JM, Collins, AB, Mansouri, J, Raje, NS, Zukerberg, LR, et al.. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue with amyloid deposition. Am J Clin Pathol 2012;137:51–64. https://doi.org/10.1309/ajcpi08wakyvlhha.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Violeta Filip, P, Cuciureanu, D, Sorina Diaconu, L, Maria Vladareanu, A, Silvia Pop, C. MALT lymphoma: epidemiology, clinical diagnosis and treatment. J Med Life 2018;11:187–93. https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2018-0035.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Taylor, MS, Sidiqi, H, Hare, J, Kwok, F, Choi, B, Lee, D, et al.. Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of amyloidosis. Intern Med J 2022;52:2046–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.15974.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Tong, JY, Juniat, V, McKelvie, PA, O’Donnell, BA, Hardy, TG, McNab, AA, et al.. Clinical and radiological features of intramuscular orbital amyloidosis: a case series and literature review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2022;38:234–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/iop.0000000000002061.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Al-Nuaimi, D, Bhatt, PR, Steeples, L, Irion, L, Bonshek, R, Leatherbarrow, B. Amyloidosis of the orbit and adnexae. Orbit 2012;31:287–98. https://doi.org/10.3109/01676830.2012.707740.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Kang, S, Dehabadi, MH, Rose, GE, Verity, DH, Amin, S, Das-Bhaumik, R. Ocular amyloid: adnexal and systemic involvement. Orbit 2020;39:13–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2019.1594988.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Grogg, KL, Aubry, MC, Vrana, JA, Theis, JD, Dogan, A. Nodular pulmonary amyloidosis is characterized by localized immunoglobulin deposition and is frequently associated with an indolent B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:406–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/pas.0b013e318272fe19.Search in Google Scholar

20. Blandford, AD, Yordi, S, Kapoor, S, Yeaney, G, Cotta, CV, Valent, J, et al.. Ocular adnexal amyloidosis: a mass spectrometric analysis. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;193:28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2018.05.032.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Sohn, EJ, Ahn, HB, Roh, MS, Jung, WJ, Ryu, WY, Kwon, YH. Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-positive ocular adnexal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and idiopathic orbital inflammation. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2018;34:313–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/iop.0000000000000965.Search in Google Scholar

22. Stone, JH. IgG4-related disease: lessons from the first 20 years. Rheumatology 2025;64:i24–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaf008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Raderer, M, Kiesewetter, B, Ferreri, AJM. Clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment of marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:152–71. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21330.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Zuo, W, Du, Y, Chen, J. Nasopharyngeal amyloidoma: report of three cases and review of the literature. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2024;150:337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-024-05873-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Hall, J, Rubinstein, S, Lilly, A, Blumberg, JM. Blu treatment of localized amyloid light chain amyloidosis with external beam radiation therapy mberg JM, chera B. Pract Radiat Oncol 2022;12:504–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prro.2022.03.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Haas, BD, Margo, CE. Orbital lymphoma, amyloid, and bone. Ophthalmology 2007;114:1237–.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.038.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Topalkara, A, Ben-Arie-Weintrob, Y, Ferry, JA, Foster, CS. Conjunctival marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MALT lymphoma) with amyloid and relapse in the stomach. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2007;15:347–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273940701375410.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Song, A, Mellgard, G, Bellofiore, C, Basset, M, Nuvolone, M, Foli, A, et al.. Diffuse lung involvement as a rare presentation of systemic AL amyloidosis: a retrospective cohort study. Blood Adv 2025. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2024015646.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Zhao, R, Dong, Y, Kong, J. Comprehensive analysis of imaging and pathological features in 20 cases of pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: a retrospective study. J Thorac Dis 2025;17:969–78. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-24-1066.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Yazici, G, Akin, S, Kahvecioglu, A, Yigit, E, Turker, FA, Yildiz, F. The role of radiotherapy in indolent ocular adnexal and orbital lymphomas. Head Neck 2025;47:891–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.27976.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Lyu, IJ, Woo, KI, Kim, YD. Primary orbital MALT lymphoma associated with localized amyloidosis. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2013;54:1109. https://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2013.54.7.1109.Search in Google Scholar

32. Grixti, A, Coupland, SE, Hsuan, J. Lacrimal gland extranodal marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-type associated with massive amyloid deposition. Acta Ophthalmol 2016;94:e667–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/oncologie-2025-0039).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Tech Science Press (TSP)

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Unveiling the hidden role of tumor-educated platelets in cancer: a promising marker for early diagnosis and treatment

- Multiple roles of mitochondria in tumorigenesis and treatment: from mechanistic insights to emerging therapeutic strategies

- The impact of JMJD5 on tumorigenesis: a literature review

- Research Articles

- A case-matched comparison of ER-α and ER-β expression between malignant and benign cystic pancreatic lesions

- Salivary gamma-glutamyltransferase activity as an indicator of redox homeostasis in breast cancer

- Cancer can be suppressed by alkalizing the tumor microenvironment: the effectiveness of “alkalization therapy” in cancer treatment

- Percutaneous-assisted laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA-mutated patients: a retrospective comparative study

- ACAT2 contributes to cervical cancer tumorigenesis by regulating the expression of the downstream gene LATS1

- Rapid Communication

- Efficacy of mild hyperthermia in cancer therapy: balancing temperature and duration

- Case Report

- Orbital marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue with amyloidosis: a case series and review of the literature

- Commentary

- Palliative external beam radiotherapy for dysphagia management in advanced esophageal cancer: a narrative perspective

- Endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer, possible connection and early diagnosis by evaluation of plasma microRNAs

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Unveiling the hidden role of tumor-educated platelets in cancer: a promising marker for early diagnosis and treatment

- Multiple roles of mitochondria in tumorigenesis and treatment: from mechanistic insights to emerging therapeutic strategies

- The impact of JMJD5 on tumorigenesis: a literature review

- Research Articles

- A case-matched comparison of ER-α and ER-β expression between malignant and benign cystic pancreatic lesions

- Salivary gamma-glutamyltransferase activity as an indicator of redox homeostasis in breast cancer

- Cancer can be suppressed by alkalizing the tumor microenvironment: the effectiveness of “alkalization therapy” in cancer treatment

- Percutaneous-assisted laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA-mutated patients: a retrospective comparative study

- ACAT2 contributes to cervical cancer tumorigenesis by regulating the expression of the downstream gene LATS1

- Rapid Communication

- Efficacy of mild hyperthermia in cancer therapy: balancing temperature and duration

- Case Report

- Orbital marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue with amyloidosis: a case series and review of the literature

- Commentary

- Palliative external beam radiotherapy for dysphagia management in advanced esophageal cancer: a narrative perspective

- Endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer, possible connection and early diagnosis by evaluation of plasma microRNAs