Abstract

Study purpose

The study analyzed online editorial cartoons depicting the Israel-Palestine conflict through visual, symbolic, metaphorical, and textual analysis. The study reveals a prevailing anti-war sentiment across editorial cartoons, with a notable inclination towards supporting Palestine. This support was prominent in cartoons originating from the Global South, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa. However, there was a scarcity of such cartoons within mainstream Western media.

Methodology

The study employs an in-depth approach, analyzing cartoons from both Western and non-Western media. It utilizes Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA) and Multimodal Semiotics (MS) theories, focusing on symbolism and text to decode nuanced narratives within the cartoons.

Main findings

The cartoons depict complex narratives, using symbolism to explain how politicians and the main media are framing specific entities while undermining victimology. They reveal subjective perspectives that influence audience perceptions. They echo existing scholarly views on the influential power of editorial cartoons in communicating complex political concepts.

Social implications

The cartoons shape public understanding of the conflict, potentially influencing biases and perspectives. They present Hamas as both an aggressor and a victim, portraying multifaceted perceptions of the group.

Practical implications

The findings are instrumental in depicting political identities, including major organizations like the UN. The boldness in depicting such entities provides a practical avenue for understanding the role of such organizations.

Originality/value

The study adds to the existing literature by applying multimodal analysis to editorial cartoons, unveiling hidden narratives and perceptions. It suggests the need for a deeper analysis of the conflict’s historical, geopolitical, and power structures. This research offers a multifaceted understanding of how editorial cartoons shape perceptions and interpretations of the Israel-Palestine conflict, emphasizing their complex and influential nature within media discourse.

1 Introduction

Editorial cartoons’ ability to capture the latent fears and unspoken beliefs of antagonists offers a refreshing perspective on how the world perceives the Israeli – Palestinian war. Therefore, examining the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through editorial cartoons reveals the overlooked complexities of power imbalances pervasive in media and political discourse (Bhowmik and Fisher 2023; Bouko et al. 2017; Meidani 2015). Efforts by scholars to mediate and propose solutions encounter considerable challenges, particularly concerning historical antecedents and the nuanced identification of aggressors and victims (Badarin 2016; Butler et al. 2016; Muhtaseb 2020; Pappe 2022; Said 2012). Various perspectives depict Israel simultaneously as both victim and aggressor, while opinions on Palestine’s victimhood diverge. The characterization of Hamas as a terrorist group further fuels debates on the ultimate victim in this conflict.

This study investigates global editorial cartoons’ portrayal of the 2023 Israel-Palestine conflict. The study examines the representational and symbolic meanings within editorial cartoons from online mainstream media content across diverse regions, excluding the Middle East due to its internal divisions. We extracted impartial narratives, emphasizing insights rooted in the broader realm of visual rhetoric (Bhowmik and Fisher 2023; Bivins 1984; Wekesa 2012). Given the sensitive nature of the conflict, we argue that profound insights are often discernible within the broader frameworks of visual rhetoric. Wekesa (2012) emphasizes that “Visuals are designed to make the reader think not only about the event or the people being portrayed but also the message being communicated” (p. 23). Additionally, it is suggested that cartoons, by nature, can objectively address sensitive topics, transcending mere caricature and amusement to convey deeper truths, as observed by Bivins (1984) and Bhowmik and Fisher (2023). Consequently, this analysis, delimited to events in October and November 2023, endeavors to illuminate ideological positions without advancing any political agenda.

2 Literature review and theory

2.1 Editorial cartoons as visual metaphors

Editorial cartoons have a rich and diverse history that permeates various cultures worldwide. Their enduring appeal lies in their unique ability to convey complicated political ideas with bold, exaggerated imagery (Shaikh et al. 2019). Matwick and Matwick (2022) highlight that editorial cartoons serve as powerful tools for swiftly and fearlessly communicating complex political concepts to a broad audience. The format and genre of editorial cartoons grant them a distinctive platform for critiquing and challenging prevailing political regimes, as noted by Bivins (1984). Cartoonists can cleverly employ symbolism within their creations, often leaving interpretations open to the audience. In cases of allegations of defamation, for instance, cartoonists can artfully argue that their caricatures conveyed intentions distinct from those claimed by the accused.

Essentially, the richness of editorial cartoons lies in their enigmatic visual metaphors, as evidenced by Gondwe and Bhowmik (2022) and Ventalon et al. (2020). Decoding these metaphors requires a keen understanding of the political context being satirized. For individuals well-versed in these contexts, the symbols and references embedded within editorial cartoons can serve as effective tools for conveying campaign strategies (Said 2012) and for cultivating a culture’s political identity (Najjar 2007). However, the inherent power of this medium, grounded in simplified visual metaphor, also comes with risks. As Moloney et al. (2013) caution, editorial cartoons may inadvertently promote essentialism. In addition, they may employ prejudiced imagery, a concern articulated by Gilmartin and Brunn (1998). This captivating blend of artistic expression and political commentary in editorial cartoons not only enriches our understanding of world events but also underscores the need for critical engagement with these visual narratives, given their capacity to influence public opinion and potentially perpetuate stereotypes. This is consistent with Elewosi et al.’s (2023) argument that editorial cartoons, through their influential characteristics, can even predict the future.

Within the above discourse, scholars such as Ardèvol-Abreu (2015), Borah (2011), D’Angelo (2017), Entman (2007), and De Vreese (2005) have advanced the argument that media organizations can selectively highlight specific aspects of reality, thereby advancing particular interpretations, assessments, and recommendations concerning the subject under consideration. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as “framing,” encompassing both framing devices, including word choice, metaphors, and visual imagery, as well as reasoning devices, which involve defining the issue, attributing responsibility, moralizing the subject, and proposing solutions. In the context of editorial cartoons, these devices manifest themselves in the form of visual metaphors, stereotypes, catchphrases, and other elements that collectively communicate a particular frame. The frames, often embodied in caricatures and vibrant imagery, assume a pivotal role in shaping how readers understand complex topics such as the Israel-Palestine conflict. Two key elements are usually at play: Ideology and Semiotics.

2.2 Ideological analysis and the role of editorial cartoons

Editorial cartoons can reveal how the depicted imagery both reflects and challenges societal beliefs when viewed through an ideological lens. An ideological lens involves the examination of images within the underlying political, social, and cultural contexts (Thomson 2022). Therefore, when examining cartoons (such as those depicting the Israel-Palestine conflict) an ideological lens would consider how an image reflects the ideological position of the creator, and how the audience interprets that image within the ideological framework. This argument centers on Antonio Gramsci’s (see, Boothman 2018) work grounded in Thomson’s (2022) conceptualization of ideological modes. Gramsci’s notion of ideology as a realm of struggle, where dominant ideologies accommodate dissenting perspectives, resonates within the roles of editorial cartoons.

Gramsci argues that dominant groups in society maintain their power not only through coercion but also through the dissemination of their worldview and values. These values become ingrained in the culture and are accepted as common sense by the masses. Accordingly, this process of hegemony occurs through various institutions, including the media. Amidst the hegemony, Gramsci argues that there is also a counter-hegemonic culture (alternative ideologies) that challenges the dominant ideologies. These counter-hegemonic forces usually emerge from marginalized groups and movements, such as Black Lives Matter, or in the context of the Isreal-Palestine conflict, the South Africans who perceive the war through the apartheid lens. Therefore, from a layman’s perspective, the Isreal-Palestine conflict may be understood through the lens of Western imagery and dominant messages that accentuate the historical religious antecedents of the conflict. However, the conflict is multilayered with economic, social, and political features that may be latently manifested in the coverage, but not obvious to news consumers. In the context of the Israel-Palestine conflict, these visually pointed, and often satirical texts serve as platforms for the dissemination and debate of contrasting viewpoints.

On the other hand, Thomson’s (2022) ideological modes offer a structured framework, encompassing naturalization, dissimulation, and unification, to understand how ideology manifests in the media. The naturalization mode in which ideological beliefs and values are presented as natural, normal, and unquestionable (Thomson 2022). In this context, the situation is depicted as inherent truths or common sense, thereby obscuring their contingent and historically constructed nature (Zreik 2024). For example, the 2024 Super Bowl Ad in support of Israel, with no mention of the Palestinian victims could be an example. Dissimulation, on the other hand, involves the concealment or distortion of ideological contradictions by masking the underlying power dynamics and tension. This process would involve the framing of particular actions within the event as defensive while others as offensive (Zreik 2024). It could also imply the omission or downplaying of other perspectives. Further, the unification mode refers to a strategy where diverse and conflicting arguments/ideologies are harmonized or reconciled within a single narrative. While this approach is preferred, Thomson (2022) argues that it mostly involves a simplistic binary approach that overlooks the context, thus reinforcing the same ideas.

Editorial cartoons play a role in these modes: naturalization presents dominant ideologies as inherently correct, potentially reinforcing or challenging these beliefs. Dissimulation, using satire, challenges established ideologies, while unification integrates dissenting views into dominant ideologies, exemplified when conflicting caricatures unite to condemn war. In the Israeli-Palestinian context, this illustrates societal shifts visually, highlighting the integration of opposing views into the dominant discourse. As Lemke’s (2013) MS theory underscores, the visual components within editorial cartoons are not mere supplements to language but convey substantial meaning. They emphasize cultural norms, ideologies, and historical narratives, as crucial elements that influence the narrative of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Accordingly, they communicate implicit ideologies through visuals, employing symbols, metaphors, and historical references to convey specific perspectives. Therefore, it is essential to decipher the underlying ideologies to understand the narrative’s construction and its influence on public perception regarding the Israel-Palestine conflict.

2.3 Semiotics in Editorial Cartoons

Semiotics, focusing on signs and symbols, plays a crucial role in interpreting complex editorial cartoons (Feng 2023; Lemke 2013). These visual texts contain numerous symbols, metaphors, and cues, each carrying multiple layers of meaning (Alsadi 2016; Bhowmik and Fisher 2023). The interactions among these elements within editorial cartoons are pivotal in framing issues and conveying intended messages (Wu 2023). One frequent semiotic aspect in editorial cartoons is the use of binary opposition, rooted in Ferdinand de Saussure’s structural semiotics. It’s evident through opposing pairings or symbols juxtaposed to highlight differences and conflicts. For instance, in Israel-Palestine conflict cartoons, you may find peace doves alongside warplanes, symbolizing the struggle for peace. In the context of Kress and van Leeuwen’s (2020) MDA, these semiotic modes depict the conflict’s events, actors, and human experiences. Visuals portraying bombings, casualties, and political figures, coupled with text-like captions, encapsulate the experiential elements, facilitating an understanding of the conflict’s realities for the audience. In this sense, semiotic analysis decodes ideological underpinnings and rhetorical devices in cartoons, enhancing our understanding of their impact on public discourse (Barthes 1977; Lemke 2013).

Editorial cartoons regarding the Israel-Palestine conflict act as influential tools, evoking thoughts and discussions. They possess the power to validate or invalidate policies, ideologies, and opinions related to the conflict (Lemke 2013). This argument has been consistent among several scholars (Alsadi 2016; Bourdon and Boudana 2016; Meidani 2015) who have demonstrated the impact. As Kress and van Leeuwen’s (2020) continue to argue, the spatial arrangement of text alongside visuals or the choice of fonts and language styles profoundly impacts the interpretation of the cartoon’s message. Therefore, editorial cartoons about the war, have a significant influence on how we perceive the war, and can either bolster or weaken the legitimacy of stakeholders and policies, influencing discourse. However, there are still gaps in research regarding how people (especially in a networked society, with presumably a few media outlets with global influence) are either influenced or uninfluenced by the globally accessed editorial cartoons. Considering cartoons reflect public opinions, further exploration into diverse viewpoints is necessary. This calls for the interrogation of visual rhetoric and critical metaphor informed using Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA). Against this backdrop, we ask the following question.

Research Question:

How do editorial cartoons across leading global media outlets portray the 2023 Israeli-Palestinian war, revealing dominant themes, narratives, and emerging visual elements?

3 Method

This study employs an in-depth approach, analyzing editorial cartoons from online mainstream media within the Western and non-Western media. We employ Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA) and Multimodal Semiotics (MS) theories, focusing on symbolism and text to decode nuanced narratives within the cartoons published in major news sources across various global continents. The Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA) framework has gained prominence for dissecting the intricate interplay between diverse communication modes, encompassing text and visuals in varied contexts. Kress and van Leeuwen’s (2020) MDA, rooted in Halliday and Matthiessen (2013) meta-functions, accentuates ideational, interpersonal, and textual facets within communication, emphasizing the intertwined nature of modes and their role in conveying ideology. This framework applies effectively to the analysis of editorial cartoons related to the Israel-Palestine conflict, elucidating how visuals and text interact to represent experiences, social relations, and ideologies.

Although this approach may appear broad, it is justified by the relative scarcity of editorial cartoons in legitimate online mainstream media sources when compared to other forms of news reporting. For example, it was difficult to find cartoons published within our timeline in media outlets like the New York Times, The Washington Post, etc. The chosen time frame, spanning from October 7th, 2023, to November 30, 2023, aligns with the onset of the first attack reported and the ensuing Israeli-Palestinian war. In other words, we picked this time frame to capture the early days of the war believed to be peaks of ‘breaking news’ content. This timeline provided us with justified information to present our case.

3.1 Sample selection

Our criteria for identifying legitimate media sources were determined based on attributes claimed by the news sources, such as professionalism, accuracy, objectivity, transparency, accountability, and independence. To avoid replicating the same content, we selected news sources believed to represent continental values, based on the size of the readership, and the nationality of the cartoonist. For instance, we used the African News Agency (https://www.africannewsagency.com/) and Africa News (https://www.africanews.com/) to characterize editorial content from Africa, in addition to other global media outlets operating within the African continent. A similar approach was employed for the Americas, Europe, and the UK, and Asia. For the sake of convenience, we did not analyze content from Latin America, Brazil, and the Caribbean.

It is important to note that not all editorial cartoons were included in our study except those meeting the following criteria: Published within our defined timeframe (7–31 October 2023), the cartoons were about the current conflict, and they made a reasonable attempt to reflect the ongoing situation of the war. In total, 58 cartoons met the criteria but 14 were included in our analysis based on their salience and representative nature of the population sample. Out of the 58 cartoons meeting the specified criteria, the breakdown by country is as follows: Africa: 25 cartoons; Americas: 13 cartoons; Europe and the UK: 8 cartoons; Asia: 12 cartoons; Among the 14 cartoons included in our analysis based on their salience and representative nature, the breakdown by country is as follows: Africa: 6 cartoons; Americas: 2 cartoons; Europe and the UK: 4 cartoons; and Asia: 2 cartoons.

In selecting 14 samples for analysis in our paper, we aimed to ensure diversity, representativeness, and relevance to the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict. Our criteria included prioritizing cartoons that demonstrated salience and pertinence to the conflict’s dynamics, while also encompassing a range of perspectives and themes. Additionally, we sought to include cartoons from reputable media sources across different regions, such as American mainstream media, Europe, the United Kingdom, Asia (including Japan and China), and Africa to capture a comprehensive overview of global perspectives on the issue. The rationale behind selecting these regions was based on their significant geopolitical influence and media landscape coverage of international affairs. This selection process was carried out after an extensive review of the profiles of our sample size, involving two trained coders who achieved an intercoder reliability accuracy of 89 %. With such a high level of accuracy, the two coders and authors worked independently to collect the images.

3.2 Data analysis

Our examination of the cartoons was grounded in the theoretical frameworks of Kress and Van Leeuwen (2006) and Lemke (2013), specifically utilizing Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA) and Multimodal Semiotics (MS). It is important to note that Kress and Van Leeuwen’s (2006) methodology heavily draws upon Halliday and Matthiessen’s (2013) Systemic Functional Grammar (SFG), recognized as the ideational or experiential meta-function employed for textual analysis in editorial cartoons. The amalgamation and expansion of Halliday’s approach by Kress and Van Leeuwen result in three meta-functions that scrutinize representational meaning, encompassing ideational, interpersonal, and textual interpretations. Consequently, our analytical approach adhered to these three dimensions.

Primarily, our analysis delved into representational meanings, involving the examination of the conceptual, analytical, and symbolic structures within the editorial cartoons. Conceptually, we sought to grasp the main theme of each cartoon at a glance. Analytically, we systematically broke down the visual images into their constituent parts, dissecting the visual elements for a more granular understanding. Symbolically, we probed deeper into the meaning behind the images, exploring symbolism such as a dove carrying an olive vine. Subsequently, we shifted our focus to the interactive meaning of the cartoons through the interpersonal meta-function. Within this analysis, we scrutinized the objects and subjects depicted in the editorial cartoons, paying specific attention to details such as the spaces within the objects, the nature of intimacy portrayed, and additional factors like the angle of the image. This interpersonal analysis aimed to reveal the social dynamics represented in the cartoons and how these elements contributed to the overall communicative intent.

Finally, we engaged in an exploration of symbolic compositional meaning, elucidating the informational value, salience, and framing within the editorial cartoons. This involved an examination of how the composition of visual and textual elements influenced the interpretation of the cartoons. This process allowed for a nuanced appreciation of the intended impact on the audience, emphasizing aspects such as what information is highlighted, how prominence is achieved, and the framing choices made by the cartoonists.

4 Findings

Our study investigates how different global regions portrayed the 2023 Israeli-Palestinian conflict through editorial cartoons. Our analysis covers America, The United Kingdom & Europe, Asia, and Africa. We explore the representational, interactive, and symbolic meanings conveyed by these cartoons. The study reveals a prevailing anti-war sentiment across editorial cartoons, with a notable inclination towards supporting Palestine. This support was evident in cartoons originating from the Global South, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa. However, there was a scarcity of such cartoons within mainstream Western media. Cartoons culled from the Asian region were similarly limited and evoked moral questions about the conflict. Nevertheless, we were able to discern perspectives that often diverged from the prevalent narrative in most Western mainstream media coverage by examining contributions from key artists associated with these media outlets.

4.1 Editorial cartoons in the American mainstream media

We found very few cartoons from America’s mainstream media. Of the few, the majority appeared to support Israel except in cases of opinion pieces. The Washington Times and The Washington Post presented most of such cartoons as illustrated below:

The cartoons in both Figures 1 and 2 are multimodal, depicting a combination of text and image. In the first editorial cartoon published by the Washington Times, a striking visual of a Hamas soldier takes center stage. It depicts Hamas as proudly responsible for violence, implying that they give reasons to support their cause. The soldier, depicted with bloodied hands raised in a gesture of pride, stands amidst a backdrop of bloody victims. Accompanying this stark image are the impactful yet sarcastic words, “Hamas gives the world a thousand more perfectly good reasons to support its cause.”

Depicting Hamas illustration by Alexander Hunter for The Washington Times (published October 12, 2023).

Depicting the Middle East in reference to the Israel-Palestine war (Michael de Adder/The Washington Post. October 10, 2023).

This composition aims to convey a powerful narrative: the soldier’s posture and the accompanying text paint a vivid picture of Hamas taking credit for the violence, seemingly boasting about their actions. This representation appears designed to dissuade any potential support for Hamas by highlighting their perceived role in perpetuating bloodshed. The text accompanying the image directly reinforces the negative portrayal of Hamas, suggesting that their actions provide reasons not to support their cause. It’s a direct commentary on the depicted scene.

The Washington Post’s cartoon depicts a desolate Middle East scene featuring two ghoulish figures engaged in conflict. One represents an “intermittent state of war,” while the other signifies a “perpetual state of war.” The haunting imagery of these ghouls engaged in combat amidst a barren landscape conveys a deeper message about the enduring conflicts in the region. This conceptual representation uses symbolic characters to convey the idea of ongoing strife, suggesting a critique of the constant state of conflict and its consequences. The text labels the ghouls as representatives of different states of conflict, creating an allegory. Essentially, the labels on the ghoulish figures serve as textual cues, framing the narrative around the persistent nature of conflict, possibly advocating for a resolution or highlighting the destructive cycle of perpetual instability in the Middle East. This representation symbolizes the ongoing and relentless nature of conflict in the region, with textual labels adding emphasis to the enduring strife and instability.

Nevertheless, other editorial cartoons, such as those by Ann Telnaes, an editorial cartoonist for the Washington Post, especially emerge to strongly condemn the war, depicting it as a humanitarian crisis ignored by Israel and the US government. Similar sentiments are expressed by Patrick Chappatte, a former New York Times editorial cartoonist and a pioneer of graphic journalism or comics journalism, who currently works for The Boston Globe (USA), Der Spiegel (Germany), le Canard enchaîné (France), Le Temps, and NZZ am Sonntag (Switzerland). Essentially, most of his artwork is directed toward biased media that continue to frame the war from the perspective of their governments (Ideology at play).

Portraying media’s strategic coverage. The State of the Debate – November 5, 2023 (https://chappatte.com/en/editorial-cartoons).

4.2 Editorial cartoons from Europe and the United Kingdom

Like the American scenario, only a limited number of editorial cartoons were found originating from the mainstream media in Europe and the United Kingdom. At the outset of the conflict, the European media did not appear to engage substantially in editorial cartoons. However, in November 2023, there was a shift as a response to a global public outcry against antisemitism, leading to the emergence of such cartoons. On the other hand, the UK exhibited more active involvement with editorial cartoons, notably evident in the Guardian newspaper, as outlined below.

Figure 4, from The Guardian, depicts a Hamas soldier holding a missile while civilians are tied to him as a shield. This image conveys a powerful message about the perceived actions of Hamas. The soldier holding the missile represents aggression or control, portraying Hamas as a militant force using civilians as human shields. This aligns with the social action/meta-function as it suggests a particular view or framing of Hamas’s actions, highlighting the idea of using civilians in warfare, likely to evoke a sense of condemnation or criticism towards Hamas.

Using human shield. Nicola Jennings on the innocent people caught up in the Israel-Gaza war (The Guardian, October 13th 2023).

Figure 5 shows a Hamas soldier releasing a hostage but hiding a bloody finger behind their back. This image likely aims to convey a sense of distrust or deception, emphasizing the idea that even when seemingly making a positive gesture, there’s an underlying indication of violence or harm. This represents the conceptual aspect by engaging the viewer in an interpretation of the character’s intentions, fostering a particular perception of the depicted entity (Hamas) and its actions.

Hostage release narrative. Nicola Jennings on Monday’s Hamas hostage release – (The Guardian, October 25th, 2023).

4.3 Editorial cartoons from Asia

In this section, we draw on the depictions elevated in the artwork that reveal the moral evaluations performed by cartoonists from the Asian region. The figures illustrate the presence of blame, impunity and a clear warning of impending danger signified by the Israeli leader. Figure 6 involves Thierry Vissol’s artwork depicting Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, with text that reads, “Residents of Gaza, Get out now.” This representation involves an interaction between the visual image and the text. The text is directive and confrontational, directly addressing the viewer and evoking a response or call to action. This interaction between text and image aims to influence the viewer’s interpretation and potentially elicit a particular response or emotional reaction, aligning with the interactive aspect of multimodal representation.

Depicting Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Thierry Vissol, Director of the Librexpression centre, Foundation Giuseppe Di Vagno, presented this article initially in Italian on Pagina 21, detailing the events of October 9, 2023.

However, the depictions are very different from those who consider themselves independent cartoonists. Essentially, most of them depicted Israel in a negative light. Essentially, unlike editorial cartoons from the West, Asia seemed to condemn the Israeli–Palestinian war, but in varying ways. China seemed partial but with a less clear stance. Journalist Mohammed Sinan Siyech described the relationship in the following manner, “China’s position on the Israel-Palestine conflict has defied expectations, refusing to explicitly condemn Hamas while allowing open criticism of Israel. How will its push for a ceasefire affect its standing in the region?” This is depicted in some of the editorial cartoons below.

The cartoon depicted in Figure 7 focuses on social action and ideational meta-function. Here, the crocodile, anthropomorphized and shedding tears while looking at the photo of a Muslim woman (presumed to be Palestinian), symbolizes a false display of emotion. The image of the crocodile crying represents insincere sorrow or faux empathy, suggesting a performative emotional response. This visual narrative implies that the crocodile’s outward display of emotion contrasts sharply with its actual actions and intentions, highlighting a disconnect between displayed sentiment and true motivations.

Crocodile tears cannot fool anyone. By Luo Jie | China Daily | Updated: 2023-11-15 08:22.

Regarding the conceptual representation that realizes the interpersonal meta-function, the cartoon’s symbolic elements – such as the elegant attire of the crocodile and its perch atop a pile of gold coins labeled as the “Military-industrial complex” – convey a message of underlying self-interest and vested motives. The juxtaposition of the elegantly dressed crocodile and the wealth it sits upon implies a sense of opulence and possibly exploitation or profit-making from conflicts, indicating a conceptual representation of hidden agendas or ulterior motives behind seemingly emotional gestures. In terms of the interactive representation that realizes the textual meta-function, the headline “Crocodile tears cannot fool anyone” serves as a textual element guiding the interpretation of the visual narrative. It acts as a caption that directly addresses the visual elements, reinforcing the central message of insincerity and attempting to sway interpretation in a specific direction. This interactive representation, through the headline, guides viewers toward a particular understanding of the crocodile’s behavior, urging skepticism toward feigned emotions or deceptive actions.

In another cartoon by China Daily, captured in Figure 8, a robot observes human behaviors illustrating wars and heinous crimes. The accompanying inscription reads, “Do the humans really expect me to learn from them.” While this cartoon appears as a standalone, the portrayal of a Muslim woman mourning the loss of her young daughter reflects the current situation surrounding the Gaza conflict. As a non-human entity, the robot’s commentary symbolizes skepticism and a critique of the human condition unworthy of emulation or human transfer. The cartoon also evokes sentiments of a broken moral compass, human depravity, death, and destruction triggered without sensitivity to human life.

What are humans teaching AI? “Wrong example” by Luo Jie | China Daily | Updated: 2023-11-03 08:20.

In contrast, Japan’s depiction seems more direct, potentially attributing responsibility to the United States for supporting Israel, as illustrated in Figure 9 below.

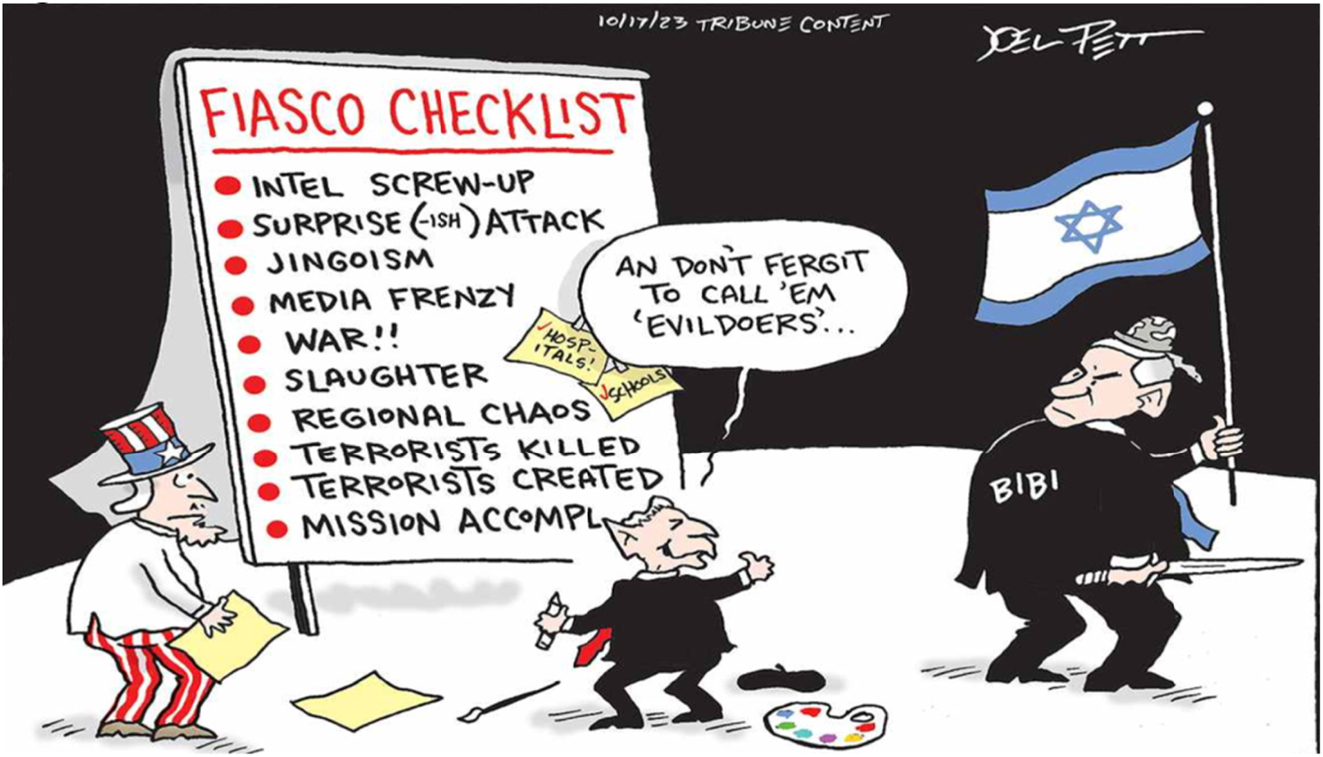

The fiasco checklist. October 18, 2023 (although the above is from the Tribune, it got published in The Japan News by the Yomiuri Shimbun).

Figure 9 focuses on narrative representation concerning the social action/ideational meta-function, conceptual representation realizing the interpersonal meta-function, and the interactive representation embodying the textual meta-function. The visual narrative portrays ‘Uncle Sam,’ clad in American Flag attire, instructing a man in a black suit and red tie to create a fiasco checklist. This checklist, featuring items like “intel screw-up,” “media frenzy,” and “slaughter,” appears to be intended for a man holding an Israeli flag, referred to as “BIBI” on the image. Additionally, the directive BIBI receives emphasizes, “And Don’t forget to call them evildoers.” This narrative construct encompasses the social action/ideational meta function by presenting a complex scenario of influence and orchestration, suggesting a behind-the-scenes involvement in creating or managing crises and narratives. The conceptual representation in this image embodies the interpersonal meta-function by symbolizing power dynamics and influence. The visual elements, such as ‘Uncle Sam’ giving instructions, symbolize the United States, the proverbial Uncle Sam, as a major player, with the checklist enabled by diabolic means to orchestrate chaos. Symbolic representations of the devil are often depicted by a midget with pointed ears, which Figure 9 captures in parody. The directives to the Israeli figure holding the Israeli flag, which appears to be Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, endearingly addressed as BIBI, collectively convey a conceptual representation of geopolitical manipulation, possibly insinuating the exertion of control or influence over events in the depicted context.

Regarding the interactive representation, Figure 9 employs textual elements to further guide interpretation. The text “And Don’t forget to call them evildoers,” serves as an interactive component that directs the viewer’s attention and interpretation toward a specific understanding of the depicted scenario, reinforcing the notion of deliberate narrative construction or manipulation. There also appears to be attribution of responsibility through discursive frame construction of the events to register blame for the post-Oct 7 conflict.

Moving to Figure 10, the visual narrative portrays a gentleman situated within what resembles a spaceship or a nuclear facility labeled ‘Iran’. Next to him is a grocery store sign labeled “MIDEAST Grocery,” and beside this scene stands another individual in traditional attire. The textual content in this image features dialogue from the individual in traditional clothing, addressing the gentleman preparing for potential actions concerning Biden and the UN sanction on the missile program. In this image, the social action/ideational meta function is reflected in the depiction of geopolitical tensions and discussions around missile programs, hinting at potential international implications and negotiations.

The MIDEAST grocery.

The conceptual representation here pertains to international relations and diplomacy, suggesting a scenario of diplomatic dialogue and implications regarding the expiration of UN sanctions. The interactive representation involves textual elements that guide interpretation, elucidating the dialogue between the depicted characters and inviting viewers to contemplate diplomatic negotiations and implications related to missile programs and international sanctions.

As a key player in the Middle East, Iran is featured more indirectly in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the cartoon signifies the US-UN optic on the geopolitical ally of the Palestinians. The cartoon also illustrates Iran’s seemingly deliberate inactivity calculated to deflect from its potentially harmful arsenal.

4.4 Editorial cartoons from Sub-Saharan Africa depicting the Israel-Palestine conflict

Our analysis focused on African mainstream media outlets, excluding major international entities like BBC-Africa or CCTV–Africa. Instead, we examined content from platforms such as African News Agency, African News, African Stream, and AllAfrica. These media predominantly share their content on widely used social media platforms including Facebook, Instagram, and X (formerly Twitter). In tracking the source of images, we utilized Google Photos despite the presence of names on most images. Our examination revealed that African media, in their editorial cartoons, demonstrated a tendency towards a broader perspective on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict compared to other continents. The cartoons exhibited a remarkable boldness in both text and imagery, often explicitly condemning the alignment of Israel and the US. Additionally, some cartoons contextualized the ongoing situation by drawing parallels to apartheid. Included below are examples of these prevailing cartoons, providing a glimpse into the distinct approaches taken by African media in portraying and commenting on the conflict.

Figure 11 presents a complex multimodal representation illustrating an individual presumed to be a member of Hamas, clad in attire reminiscent of Israel’s Prime Minister, Netanyahu. Within this image, several visual and symbolic elements contribute to its meaning. The soldier is visually represented wearing a headband inscribed with the name “Netanyahu,” a salient visual cue aligning the character with Israel’s leadership. Moreover, the soldier is depicted engaging in an action: inserting a missile into a baby carriage containing a visibly distressed infant. Importantly, the carriage prominently displays a Palestinian flag, serving as a symbolic representation of the innocent Palestinian children affected by the conflict.

The blame of Hamas is reversed to Israel. Simon Regis 5 November 2023.

From a multimodal perspective, this representation is rich in narrative and meaning, aligning with Kress and Van Leeuwen’s theory. The narrative, operating within the social action and ideational meta-function, constructs a visual story implying a significant social commentary. The portrayal challenges the established narrative of Hamas perpetrating violence by suggesting that the perceived wrongdoings typically attributed to Hamas might actually originate from Israel. Conceptually, the image engages the viewer on an interpersonal level, fulfilling the conceptual representation and realizing the interpersonal meta-function. By amalgamating the visual elements, such as the headband with Netanyahu’s name and the missile in the carriage, the representation conveys a conceptual message. This message is suggestive of a critical perspective, aiming to provoke reflection on the underlying causes of the conflict and question the conventional attributions of blame.

In terms of the interactive representation and the textual meta-function, the image interacts with its audience through the visual language it employs. It does so by strategically utilizing symbols and visual cues to communicate a particular stance on the conflict. Through these visual choices, the image invites interpretation and fosters critical engagement, encouraging viewers to reflect on the complexities of the situation beyond surface-level attributions of fault.

Figure 12, an artwork by Salum Matata, employs various visual elements to convey a poignant commentary on the Israel-Palestine conflict. The image features a dominant visual of a large hand, adorned with an Israeli flag, firmly squeezing a small figurine holding a Palestinian flag. This visual representation symbolizes the overpowering dominance of Israel over Palestine, highlighting the severe power imbalance in the conflict. Adjacent to this central imagery is a depiction of a well-fed man, a symbolic representation of wealth in many Sub-Saharan African cultures. This figure, with a contented expression, is depicted taking photographs, seemingly pleased, while one hand rests casually in the pocket. Notably, the man is clothed in a blue shirt bearing the conspicuous letters “UN,” signifying his embodiment of the United Nations.

Challenging the role of the United Nations in the Israel – Palestine war. Originally published in 2016, this image resurfaced in October 2023.

The narrative representation within the image operates on multiple levels. Targeting the social action and ideational meta-function, it conveys a narrative suggesting the United Nations’ complacency and apathy toward the suffering of the Palestinians. The portrayal of the hand squeezing the Palestinian figure signifies the oppressive control exercised by Israel, while the relaxed demeanor of the UN figure captures a sense of detachment, indifference to this plight, or endorsement of Israel’s relative advantage in the conflict based on the scope of international support.

Conceptually, the image fulfills the interpersonal meta-function through its conceptual representation. It conveys a critical message regarding the lack of proactive intervention or assistance from the United Nations, effectively positioning the UN as a disinterested observer in the conflict. The visual juxtaposition of the UN figure’s contentment with the suffering depicted in the foreground reinforces this conceptual critique. Regarding the interactive representation and textual meta-function, the image interacts with its audience by employing powerful visual symbolism and metaphorical representations. Through these visual choices, the artwork prompts viewers to critically engage with the perceived role of international organizations, specifically the United Nations, in addressing humanitarian crises and fostering a dialogue about responsibility and intervention. The image also appears to activate the UN’s complicity in the conflict, thus evoking a sense of angst among viewers.

Figure 13 depicts the barrages of rockets released by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) hitting hospitals and schools reportedly used as hideout grounds by Hamas, while scores of women and children who are in close proximity of that raid become easy targets, as the missiles miss the intended target (in this case, Hamas). The narrative emphasizes the vulnerability of these individuals and portrays the situation as one-sided aggression against defenseless civilians. Conceptually, the image establishes an interpersonal connection by highlighting the asymmetry of power and the impact of conflict on vulnerable populations. It communicates a sense of imbalance, where the IDF, represented by the barrages of rockets, holds the upper hand, targeting spaces associated with the safety and well-being of civilians. The portrayal of women and children as “easy targets” underscores the interpersonal dynamics of vulnerability and victimhood.

Barrages of rockets released by the IDF. Kenny Tosh 15 November 2023.

The text interacts with the visual components to guide the viewer’s understanding and emotional response to the depicted scenario and signifies the conflict as unrelenting despite the human casualties. Peacebuilding is framed as elusive notwithstanding the presence of schools and hospitals.

In Figure 14, the visual representation portrays Israel’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, visibly enraged by the October 7 attack and striving to retaliate by initiating an aggressive response towards Gaza. The image depicts Netanyahu holding a knife, which symbolizes Gaza, while the handle of the knife is illustrated as the head of Hamas. Furthermore, Netanyahu is depicted with a lit matchstick, implying his intent to set ablaze the sharp edge of the knife marked as Gaza. Hamas, in turn, is shown requesting a ceasefire following extensive destruction in Gaza.

The ceasefire irony. Kenny Tosh 14 November 2023.

In the context of Kress and Van Leeuween’s multimodal theory, this visual narrative encapsulates various layers of meaning. The social action/ideational meta-function is evident through the portrayal of Netanyahu’s aggressive stance and his perceived retaliation against Gaza and Hamas, reflecting the ideological conflict and actions in response to the attack.

The conceptual representation, as part of the interpersonal meta-function, embodies the interpersonal relationship between Netanyahu, Gaza, and Hamas. The use of the knife as a symbol of Gaza and Hamas signifies a conceptual representation of conflict, power, and control, illustrating Netanyahu’s intention to exert dominance over them. The interactive representation, linked to the textual meta-function, involves the audience’s engagement with the visual elements. It prompts interpretation and understanding of the depicted scenario, framing the narrative of Netanyahu’s forceful response to the attack and Hamas’s plea for a ceasefire, potentially shaping the viewer’s perception of the conflict dynamics.

5 Discussion and conclusion

The study explores how various global regions depicted the 2023 Israeli-Palestinian conflict through editorial cartoons, covering America, the United Kingdom & Europe, Asia, and Africa. It reveals a prevalent anti-war sentiment across cartoons, particularly in support of Palestine, with a scarcity of such depictions in mainstream Western media. American cartoons often favored Israel, while European and UK cartoons emerged more actively after public outcry against anti-Semitism. Asian cartoons tended to condemn the conflict but with varying stances, and African media demonstrated a bold condemnation of Israel-US alignment, often paralleling the conflict with apartheid. The analysis highlights diverse perspectives challenging prevailing narratives, particularly evident in cartoons from independent artists like Ann Telnaes and Patrick Chappatte in the US. Similarly, African cartoons offered a broader critique of the conflict, while Asian cartoons raised moral questions. The study underscores the nuanced portrayal of the conflict across different global regions through editorial cartoons.

Depictions in editorial cartoons are multifaceted and laden with symbolism. They often amalgamate visual elements, textual cues, and symbolic representations to communicate intricate narratives. The classification of entities like Hamas, Israel, or the UN within these cartoons serves as visual rhetoric, framing the conflict and influencing audience perceptions. These depictions are inherently subjective and can significantly impact how readers interpret and understand complex geopolitical issues. Nonetheless, the findings cohere theoretically with Kress and van Leeuwen’s Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA) and Lemke’s Multimodal Semiotics (MS) based on the visual and textual symbolism elevated across the cartoons we analyzed from both Western and non-Western media. The findings also confirm what most scholars contend that editorial cartoons, “serve as powerful tools for swiftly and fearlessly communicating complex political concepts to a broad audience” (Bivins 1984; Matwick and Matwick 2022; Shaikh and Najeeb-us-Saqlain 2016).

Arguably, we see editorial cartoonists fearlessly pointing out sensitive information that most mainstream media were unable to discuss. Hamas, for instance, though declared as a terrorist group, is often portrayed both as a central figure and a victim. Essentially, cartoonists frequently depicted Hamas members as aggressive or militant, wielding symbols of violence, such as weapons or missiles. These depictions are evident in Figures 1 and 2. However, they are ironic as the cartoonists seem to be playing to the galleries of most Western governments. Within the depiction of Hamas as a terrorist group, the cartoonists were also able to decipher a narrative of a victim of oppression, a group used as a scapegoat, etc.

Najjar (2007), notes that cartoons cultivate a culture’s political identity. Simultaneously cartoons promote oppositional reading of a culture (Moloney et al. 2013). These assertions correspond with cartoons published by the Washington Times and the Washington Post in the wake of the conflict. Figure 1, published by the Washington Times, embodies multimodal depictions of the Hamas political group on a path of death and destruction, while Figure 2, published by the Washington Post, depicts the Middle East as an unstable region, thus problematizing their political identity based on prolonged conflict. Nonetheless, our findings also coincide with concerns by Gilmartin and Brunn (1998) who felt that messages embedded in cartoons tend to elevate prejudice. While Ventalon et al. (2020) found that cartoons accentuate visual metaphors correspondingly we discerned that both Figures 1 and 2 evoke perceptions of death, fear, internal strife, and conflict perpetrated by Palestinians. The accompanying text in Figure 1 also invites anti-Hamas viewer perceptions of a [terrorist] group undeserving of sympathy. These manifestations of the attribution of blame and responsibility are consistent with the notion that perceptions and interpretations are influenced by selective media frames (Ardèvol-Abreu 2015; Borah 2011; D’Angelo 2017; De Vreese 2005; Entman 2007). Figure 3 further illustrates the commentary of issue-salience and frames embedded within media coverage to seemingly prime audience interpretations.

Cartoon depictions in Figures 4 and 5 further reinforce blame, but we note the presence of Lemke’s Multimodal Semiotics (MS) in Figure 4, with Jennings symbolizing innocent casualties as a direct effect of Israel’s response to the Oct 7 attack. The semiotics of the Hamas fighter situated among civilian casualties embody cultural representation of the fearless suicide missions often associated with Islamic jihads. Thus, hidden messages depict Hamas, though violent, as a non-entity that Israel is using to justify the IDF response to Palestine. Some narratives equated the event to apartheid and genocide intended to wipe out all the Palestinians. These depictions also align with Thomson’s (2022) ideological modes of naturalization, dissimulation, and unification. For example, Hamas is presented as an instigator of conflict, highlighting its role in perpetuating violence. Yet, the root cause is often ignored and not highlighted in the common narratives (dissimulation).

Conversely, editorial cartoons portrayed Israel and its Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, as further igniting rather than quelling the war. Figures 6 and 9 in particular act as moral discourses and collaboratively question Netanyahu’s role in the conflict. The narrative espouses the ideology that Netanyahu has the power to end the war but he chooses self-aggrandizement and opts to function as a symbol of war. Essentially, the Prime Minister is depicted as an authoritative or assertive figure, wielding power symbols or engaging in actions that signify control. The Prime Minister was usually presented in binary opposing motions, or through oppositional pairings and paradigmatic relationships, wherein contrasting elements or symbols are juxtaposed to emphasize differences and conflicts, thus consistent with Alsadi (2013), Lemke (2013), and Wu (2023). In other words, the cartoons portray Israel as holding the keys to the war with the ability to stop it whenever they wanted.

The United Nations (UN), which should symbolize unity and global peace, is depicted as passive, failing to prevent the conflict’s escalation or protect vulnerable populations. Some underlying messages depict the UN as a Western organization controlled by the US. As a result, it is seen as siding with Israel and ignoring the implications of the war. In other words, the portrayals tend to challenge the notion of the UN as an effective peacekeeping body, instead suggesting its ineffective or complicit role in the conflict.

Overall, the findings of this study suggest that visual representations of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict magnified by cartoonists offer both discrete and unstable interpretations of the issue. The cartoons revealed the ideological nature of the war, victims, and victimhood through distinct interpretations. While we relied on existing theoretical and conceptual models to analyze the cartoons, the multilayered nature of the conflict, signification, and signifiers all contribute to the critical lens that is necessary for a deeper meaning to be located across the imageries. We suggest that a full-scale analysis of the historical, geopolitical, and power structures engaged in the war is necessary to complement our findings. We also consider a thematic analysis of news coverage and accompanying photos instrumental to offering a more in-depth interpretation of frames within the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Against this backdrop, we want to rehash the limitations of this study. Firstly, our study cannot be generalized as it points to a few cartoons. We believe that more other cartoons would provide a bigger picture. Second, our selection criteria, though rigorously designed, were not perfect in the sense that we relied upon internet searches. There is a high likelihood that we missed some relevant caricature that could provide a better explanation. Nonetheless, we strongly believe that our findings will largely contribute to the gaps in research particularly amid the sensitivity of the topic of ongoing conflict in Israel and Palestine.

References

Alsadi, Wejdan. 2016. I see what is said: The interaction between multimodal metaphors and intertextuality in cartoons, 13–19. Dublin: University College Cork.10.33178/boolean.2015.4Search in Google Scholar

Ardèvol-Abreu, Alberto. 2015. Framing theory in communication research. Origins, development and current situation in Spain. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 70. 423–450. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2015-1053en.Search in Google Scholar

Badarin, Emile. 2016. Palestinian political discourse: Between exile and occupation. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315656755Search in Google Scholar

Barthes, Roland. 1977. Image-music-text, 6135. New York: Macmillan – Hill & Wang.Search in Google Scholar

Bhowmik, Sima & Jolene Fisher. 2023. Framing the Israel-Palestine conflict 2021: Investigation of CNN’s coverage from a peace journalism perspective. Media, Culture & Society 45(5). 1019–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437231154766.Search in Google Scholar

Bivins, Thomas H. 1984. Format preferences in editorial cartooning. Journalism Quarterly 61(1). 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769908406100128.Search in Google Scholar

Boothman, Derek. 2018. Gramsci: Structure of language, structure of ideology. Revisiting Gramsci’s notebooks, 65–81. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004417694_006Search in Google Scholar

Borah, Porismita. 2011. Conceptual issues in framing theory: A systematic examination of a decade’s literature. Journal of Communication 61(2). 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01539.x.Search in Google Scholar

Bouko, Catherine, Laura Calabrese & Orphée De Clercq. 2017. Cartoons as interdiscourse: A quali-quantitative analysis of social representations based on collective imagination in cartoons produced after the Charlie Hebdo attack. Discourse, Context & Media 15. 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2016.12.001.Search in Google Scholar

Bourdon, Jerome & Sandrine Boudana. 2016. Controversial cartoons in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: Cries of outrage and dialogue of the deaf. The International Journal of Press/Politics 21(2). 188–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161215626565.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, Judith, Zeynep Gambetti & Leticia Sabsay (eds.). 2016. Vulnerability in resistance. Durham: Duke University Press.10.1515/9780822373490Search in Google Scholar

D’Angelo, Paul. 2017. Framing: Media frames. The international encyclopedia of media effects, 1–10. New Jersey: JohnWiley & Sons, Inc.10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0048Search in Google Scholar

De Vreese, Claes H. 2005. News framing: Theory and typology. Information Design Journal+ Document Design 13(1). 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1075/idjdd.13.1.06vre.Search in Google Scholar

Elewosi, Millicent, Michael Ofori & Felicity Sena Dogbatse. 2023. “We are only to appear to be fighting corruption … we can’t even bite”: Online memetic anti-corruption discourse in the Ghanaian media. Online Media and Global Communication 2(1). 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1515/omgc-2023-0001.Search in Google Scholar

Entman, Robert M. 2007. Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of Communication 57(1). 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x.Search in Google Scholar

Feng, Pin-chia. 2023. Visual imagination and narrativisation of COVID-19: The case of Sonny Liew. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 24(1). 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2023.2156681.Search in Google Scholar

Gilmartin, Patricia & Stanley D. Brunn. 1998. The representation of women in political cartoons of the 1995 World Conference on Women. Women’s Studies International Forum 21(5). 535–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-5395(98)00063-6.Search in Google Scholar

Gondwe, Gregory & Sima Bhowmik. 2022. Visual representation of the 2020 Black Lives matter protests: Comparing US mainstream media images to citizens’ social media postings. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies 12(4). e202238. https://doi.org/10.30935/ojcmt/12494.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood & Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 2013. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. Revised by Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. Birmingham: Routledge.10.4324/9780203431269Search in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther & Theo Van Leeuwen. 2020. Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003099857Search in Google Scholar

Lemke, Jay L. 2013. Multimedia and discourse analysis. The Routledge handbook of discourse analysis, 79–89. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Matwick, Keri & Kelsi Matwick. 2022. Comics and humor as a mode of government communication on public hygiene posters in Singapore. Discourse, Context & Media 46. 100590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2022.100590.Search in Google Scholar

Meidani, Mahdiyeh. 2015. Holocaust cartoons as ideographs: Visual and rhetorical analysis of holocaust cartoons. Sage Open 5(3). 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015597727.Search in Google Scholar

Moloney, Gail, Peter Holtz & Wolfgang Wagner. 2013. Editorial political cartoons in Australia: Social representations & and the visual depiction of essentialism. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 47. 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-013-9236-0.Search in Google Scholar

Muhtaseb, Ahlam. 2020. US media darlings: Arab and Muslim women activists, exceptionalism and the “rescue narrative”. Arab Studies Quarterly. ASQ 42(1 & 2). 7–24. https://doi.org/10.13169/arabstudquar.42.1-2.0007.Search in Google Scholar

Najjar, Orayb Aref. 2007. Cartoons as a site for the construction of Palestinian refugee identity: An exploratory study of cartoonist Naji al-Ali. Journal of Communication Inquiry 31(3). 255–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/019685990730.Search in Google Scholar

Pappe, Ilan. 2022. A history of modern Palestine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108233743Search in Google Scholar

Said, Edward W. 2012. The politics of dispossession: The struggle for Palestinian self-determination, 1969–1994. New York: Vintage Books.Search in Google Scholar

Shaikh, Nazra Zahid, Ruksana Tariq & Najeeb-us-Saqlain Saqlain. 2019. Cartoon war …… A political dilemma! A semiotic analysis of political cartoons. Journal of Media Studies 31(1). 74–92.Search in Google Scholar

Thomson, Alex. 2022. An introduction to African politics. London: Taylor & Francis.10.4324/9781003031840Search in Google Scholar

Ventalon, Geoffrey, Grozdana Erjavec, Sanghun Bang & Charles Tijus. 2020. Resource allocation for visual metaphor processing: A study of political cartoons. Visual Cognition 28(4). 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13506285.2020.1787570.Search in Google Scholar

Wekesa, Nyongesa Ben. 2012. Cartoons can talk? Visual analysis of cartoons on the 2007/2008 post-election violence in Kenya: A visual argumentation approach. Discourse & Communication 6. 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481312439818.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Anping. 2023. The images of China in political cartoons of foreign media. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 13(4). 523–558. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2023.134033.Search in Google Scholar

Zreik, Mohamad. 2024. Decolonizing the developmental agenda: A prerequisite for African democracy and governance. Democratization of Africa and its impact on the global economy, 122–138. Hershey: IGI Global.10.4018/979-8-3693-0477-8.ch008Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Victims or villains? How editorial cartoons depict the 2023 Israel – Palestine war

- Affect, credibility, and solidarity: strategic narratives of NGOs’ relief and advocacy efforts for Gaza

- “Tears have never won anyone freedom:” a multimodal discourse analysis of Ukraine’s use of memes in a propaganda war of global scale

- City images in transnational travel vlogs from a multimodal perspective: an investigation of 20 port cities worldwide

- Mobile app adoption comparison between U.S. and Chinese college students: information processing style and use frequency after download

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- Automation of visual communication and aesthetic construction of national image: a computational aesthetic analysis of social bots on Twitter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Victims or villains? How editorial cartoons depict the 2023 Israel – Palestine war

- Affect, credibility, and solidarity: strategic narratives of NGOs’ relief and advocacy efforts for Gaza

- “Tears have never won anyone freedom:” a multimodal discourse analysis of Ukraine’s use of memes in a propaganda war of global scale

- City images in transnational travel vlogs from a multimodal perspective: an investigation of 20 port cities worldwide

- Mobile app adoption comparison between U.S. and Chinese college students: information processing style and use frequency after download

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- Automation of visual communication and aesthetic construction of national image: a computational aesthetic analysis of social bots on Twitter