Abstract

Purpose

Gen Z or younger news audiences are believed to contribute to declining news consumption as a result of decreased news interest and reduced trust, particularly in political news. It can have adverse consequences for democratic processes. This study offers a more nuanced perspective by qualifying the role of context, and generational differences and similarities in online political news consumption patterns before and after the 2020 US presidential election, which witnessed a series of unprecedented events in the country’s history.

Design/methodology/approach

To investigate these patterns, I use US aggregated website visitation data from Comscore in a quasi-experimental interrupted time series design, leveraging the 2020 election as a natural experimental condition.

Findings

While Gen Z are indeed consuming considerably less news, contrary to assumptions, there was significantly increased engagement with news websites following the election. Additionally, media audiences across generations are likely to reduce social media use during such events.

Implications

Major political events can significantly influence media use patterns such as the extent of news consumption in general and political news in particular, something not often considered in media effects-oriented research. There is also an urgent need to review and reassess our definitions of news, news sources, and its audience.

Originality/value

By using observational data in a quasi-experimental design, this study offers a more precise and refined perspective of generational patterns of online political news consumption in the context of a major political event that both corroborates as well as challenges some our existing notions of media use.

As the Fourth Estate, a vibrant media ecosystem is a critical component of any functioning democracy. During the early years, the popularity of digital media, particularly social media, was often hailed as a panacea for social inequality and ushering in positive democratic change. Yet in the years since, the optimism surrounding the so-called “Networked Fourth Estate” (Benkler 2011) has been faced with a global decline in audience trust in the press (Park et al. 2020). Factors such as a fragmented and increasingly polarized media ecosystem (Davis and Dunaway 2016), exposure to misinformation (Ognyanova 2020), and an ever-changing dynamic between audiences and the news industry (Nelson 2021) contribute to the declining trust. Recent reports suggest that an increasing percentage of media audiences are avoiding news content from traditional sources (Newman et al. 2021), owing to declining media trust as well as the growing popularity of social media as a news source (Shearer 2021). Concurrently, electoral democracies across the world have been grappling with increased political polarization – often believed to be fueled by such fragmented media ecosystems and the rise of social media (Carothers and O’Donohue 2019).

Concerns regarding the adverse impacts of declining news engagement on democratic processes, particularly among the youth, are quite justified. Among US audiences, a majority indicate receiving news from digital sources, with social media often reported as the primary source among younger populations (Newman et al. 2021), outpacing even news websites and mobile apps. Advancements in technology, coupled with changing media consumption habits among millennials have already transformed news making, production, and distribution practices (Kramp and Loosen 2018). Succeeding the millennial generation, Gen Z audiences are likely to reshape news consumption trends even further in the coming years. As digital natives, today’s youth perhaps represent the most prolific demographic of digital media consumers. As such, the media use habits of Gen Z is thought to be a major contributor to the declining popularity of traditional news sources. While some studies point to the positive impact of digital media use on civic and political engagement (Chae et al. 2019), even among the youth (Boulianne and Theocharis 2020), others offer a more nuanced take where digital media use is associated with a reinforcement effect among those who are already politically engaged (Oser and Boulianne 2020). Further, Matthes (2022) contends that social media use among the youth may actually diminish political engagement. While there is strong evidence on either side of this debate, the persistence of an effects-driven research paradigm in the discipline often overshadows a couple of more fundamental audience-centric questions – how much political news do young people consume online, and what platforms do they consume it on? An empirical examination of the underlying media consumption patterns is therefore essential to critically (re)evaluate the assumptions on which a majority of effects research rests on. It is imperative that we study the online news and media consumption patterns of Gen Z audiences in more depth to establish the extent of decline in political news consumption among younger audiences. The 2020 US presidential election presented a unique opportunity to study these patterns as Gen Z accounted for 8 % of all voters (Igielnik et al. 2021), up from 2 % in 2016 (Fry 2017). The intensified fractures in the US news ecosystem along ideological lines between these two elections (Flamino et al. 2023) and the unprecedented series of events that transpired after the 2020 election provides further incentive to study how news consumption patterns may vary across generational cohorts during a major political events.

Even with the minimal amount of available self-reported data for Gen Z adults, there are indications that they are likely to be the most educated generation and have considerable interest in political issues (Parker et al. 2019). However, barring a handful of isolated studies conducted outside the US on general media consumption habits of Gen Z, scholarly inquiry of cross-generational news use in the US involving Gen Z remains limited. Given these considerations, this study attempts to empirically explore and compare the patterns of political news consumption between Gen Z, the two preceding generations as well as the total US digital media audience. Using observational site visitation data from Comscore instead of self-reported survey data and utilizing the 2020 US presidential election as a natural experimental condition, quasi-experimental interrupted time series analyses are conducted to explore these patterns.

1 Generational patterns of media use

Previous studies have indicated that there are considerable differences in the media use patterns between generational cohorts. In his articulation of the terms “digital native” and “digital immigrant”, Prensky (2001) argued that digital literacy is a key factor that differentiated the youth from their previous generation at the turn of the millennium. Media generations are often conceptualized through the lens of Karl Mannheim’s concept of social generations, which he defined as a group in an age cohort who share similar social and historical experiences within a given geographical context (Bolin 2016). These shared experiences often manifest themselves in the form of media habits that shape a generation’s perspective of society and how they navigate social structures and relationships (Bolin 2016; Diehl et al. 2019). Millennials or Generation Y is the first generation to have grown up with digital technology during adolescence, which led to Prensky (2001) terming them as digital natives. Yet, a couple of decades on, we now have a generation who were born after the invention of the World Wide Web and have had much wider access to digital technologies than the preceding generation. Indeed, in a later article Prensky noted that the differences solely based on the use of digital technology between generations will likely become less pronounced over time (2009).

Beyond the access to digital technologies that shape patterns of general media consumption habits, news consumption habits among the youth are also influenced by social conditions and communication processes at home, school, and political climate (Lee et al. 2013; Vaala and Bleakley 2015; York and Scholl 2015). Thus, the socialization and access to digital technologies together shape a generation’s media consumption habits. From that perspective, it is easy to envision why and how Gen Z audiences are perhaps the least likely to consume news through traditional media. Considering that parents of Gen Z audiences likely belong in the Gen Y and Gen X cohorts, the shift away from traditional media is likely to grow further. A longitudinal generational cohort study of US middle and high school students between 1976 and 2016 found that there was a steady increase in the adoption of digital media; almost completely replacing the consumption of print, and a gradual decline of television (Twenge et al. 2019).

2 Audience-centric perspectives of online news use

The primary focus of research on online news consumption has revolved around its effects on media audiences. Generally, such explanations for media use and its effects forward a user preferences perspective, which assumes that individuals consciously choose, have specific needs, and prefer certain media content (Webster 2014). People’s desire in staying informed with current events can motivate their use of online news (Wonneberger et al. 2011), which may arise from a sense of civic duty (Poindexter and McCombs 2001). This behavior is quite similar to traditional patterns of routinized news consumption. While some users actively search for and consume news content through search engines (Robertson et al. 2023), for the most part, news exposure through search engines tends to occur incidentally (Möller et al. 2020). Additionally, individuals may also come across news content while using social media, although such exposure is often involuntary (Ahmadi and Wohn 2018).

While Gen Z audiences are more likely to rely on digital media technologies and platforms for consuming news, there is a growing body of literature providing compelling evidence that news consumption is not a salient component of most people’s online media diets (Stier et al. 2022; Wojcieszak et al. 2021). Ha et al. (2018) found that while mobile phone and social media use both were positively associated with time spent consuming news, the overall news consumption time trended downwards over time. While previous studies have explored and forwarded both individual preference driven perspectives (Goyanes et al. 2023) and structural perspectives (Toff and Kalogeropoulos 2020) to explain news avoidance, it might very well be explained through some combination of both (Villi et al. 2022).

Even though news consumption may be declining, overall time spent on the internet has been increasing (Kemp 2022). This is hardly surprising since many traditionally offline services are increasingly becoming available online; a transition greatly accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Social media use also comprises a significant portion of people’s daily internet use (Kemp 2022). Given these considerations and numerous self-reports of news consumption behavior, the assumption that online audiences are increasingly getting their news from social media seems reasonable. Yet, there is a longstanding acknowledgement of the severe shortcomings of using self-reported measures for (online) news consumption, whose estimates can be extremely inaccurate due to social desirability bias (Konitzer et al. 2021). Another frequently overlooked aspect of media audience behavior pertains to the role of audience availability, wherein, any form of media consumption is conditional upon an individual having the spare time to consume the media content (Taneja et al. 2012). For a vast majority of internet users, their media diets overwhelmingly comprise the most popular platforms and outlets (Taneja 2020). This has two major implications for our understanding of online news consumption. First, time spent on online news outlets may be strongly associated with overall internet use only if it is a salient component of people’s online activities. Second, regardless of user motivation, time spent on social media will also be strongly associated with overall internet use, especially since it comprises a significant portion of people’s daily internet use.

Hence, it is necessary to assess how closely time spent on online news use is correlated with both social media use and overall time spent on the internet using passive observational data. Further, we also know that the patterns of online activity vary by age groups. But few studies have investigated whether there exists any generational difference in news consumption patterns, especially using observational data. In other words, while there is a consensus that people are consuming less news than before, more evidence is required to explain whether patterns of online media use and news avoidance are manifested differently across generations. Hence the following broad research questions are proposed:

RQ1:

How closely are internet use, news use, and social media use associated with each other?

RQ2:

Are there any generational differences between media use patterns of Gen Z, their preceding generations, and the population as a whole?

3 Gen Z political news consumption

Even though overall news consumption among younger audiences might be on the decline, it should not be interpreted as an indicator of declining interest in political issues. In fact, Gen Z and Gen Y often share similar liberal attitudes towards many hot button sociopolitical issues in the US such as race, gender, climate, economy, role of government, etc (Parker et al. 2019). Milkman (2017) posits that millennials (and likely Gen Z young adults) constitute a new political generation that not only aligns more closely with left-leaning ideals, but their sources of information and their media of expressing political opinions are markedly different from the previous generations. A 2015 study conducted by Pew Research Center (Mitchell et al. 2015) found that millennials are much more likely to receive political news content from social media compared to Baby Boomers, despite having less interest in political issues. However, in a media environment where the boundaries between news and other kinds of information are getting increasingly blurry, a large percentage of the young adult population have a broader definition of news than media researchers typically acknowledge (Edgerly and Vraga 2019; Head et al. 2018; Tamboer et al. 2022). Diehl et al.’s (2019) analysis of multi-platform news use also suggests that young adults often take advantage of a multi-platform news environment, which in turn is associated with greater political participation. However, considering that Gen Z audiences are less likely to engage with traditional news media platforms and rely mostly on online sources, there is a need to determine whether there exists any difference in the consumption of political news content across online platforms and if such patterns are consistent with the total population as well as the previous generations.

There is an overwhelming consensus on the positive effects of social media use on political participation and engagement (Boulianne and Theocharis 2020; Chae et al. 2019; Gil de Zúñiga et al. 2012). However, it is imperative to note that politically active individuals are more likely to use social media for political news consumption and be more politically engaged anyway. Indeed, a descriptive analysis of official voter data from multiple countries indicated that the generational gap in political participation has only increased or at least remained constant, despite the fact that social media usage has increased exponentially over the years, especially among the youth (Matthes 2022). Although such findings do not provide definitive proof that young adults are using social media less for political news consumption, it does motivate further inquiry into how and under what conditions individuals may use social media or other digital platforms for obtaining political news.

Given the above considerations, this study explores the generational differences in the patterns of online political and overall news consumption. It does so by leveraging the 2020 US presidential election as a natural experimental condition using aggregated observational time series data of internet use. In the months leading up to the election on November 3, Donald Trump and several other Republican politicians had repeatedly attacked mail-in ballots, suggesting that it will result in large scale voter fraud (Riccardi 2020). While the presidential debates likely drew some audience attention before the election, events after the election, particularly Trump’s refusal to accept the results, his doubling down on voter fraud claims, and attempts to overturn the results arguably attracted more attention as his actions were largely unprecedented. In addition to an expected change in the amount of time people spend consuming online news, it was also the first major election which had a considerable number of Gen Z voters. As a result, analyzing the patterns of consumption of general news, political news, and social media use between Gen Z, millennials, Gen X, and the total US digital population can provide valuable insights into how similar or how different news consumption patterns are. Accordingly, the following research questions are proposed:

RQ3:

Did the 2020 election significantly affect people’s news interest in general, in political news, and social media use?

RQ4:

If so, are there any generational differences in how the election impacted people’s media use patterns?

4 Methods

4.1 Data

The data for this study comes from web analytic company Comscore. This study uses the aggregated multiplatform website use data of US online audiences that are published monthly. Comscore passively collects site visitation data through software meters installed on the devices of each of its 1 million desktop users as well as app and website visits from its panel of 30,000 mobile users (Comscore 2013). Weightings are applied to the aggregated monthly data in order to project the internet use behavior to the total US internet audience. Unlike digital trace data that may be collected from individual websites or self-reported usage data through surveys, Comscore provides a more uniform and precise measure of observed audience behavior (Taneja 2016; Wu and Taneja 2021). As such, this study uses the deduplicated data of website visits from both the desktop and mobile panel of US users.

To study the news consumption patterns between the age groups, the monthly aggregated data for a 28-month period from September 2019 to December 2021 was used. Comscore not only provides visitation data for individual websites but also offers the aggregated data for multiple major website categories such as “News/Information”, “Social Networking”, “Entertainment”, etc. Hence, the data for the overall “News/Information” category, the “Political” news sub-category, and the “Social Networking” category were downloaded. The monthly visitation data for each category were downloaded separately for different age groups. While a Pew Research Center report (Dimock 2019) is frequently cited to define the cut-off point between millennials (Gen Y) and Gen Z as 1996, other scholars and media outlets sometimes define Gen Z as individuals born since 1995. For the purpose of this study, the 18–24 age group has been defined as Gen Z i.e. those born after 2000. Due to the filtering constraints for Comscore data, instead of separately defining Gen X and Gen Y, an age filter of 25–49 was used to represent a combined cohort of the prior two generations, henceforth referred to as Gen XY. While there might be a small overlap with the Gen Z, Comscore reports the average metrics and as such, Gen XY is likely to represent the average internet user who grew up during the 80s and early 90s. Additionally, the monthly visitation data was also downloaded for the total US digital population, which represents the average internet use pattern of an individual.

4.2 Measures

4.2.1 Engagement

While media consumption can be operationalized in a variety of different ways, this study uses the time spent on a website as a proxy for online audience engagement following Nelson and Webster (2016). Accordingly, the average minutes per visitor per month metric is utilized as the key dependent variables. For the overall news engagement measure, the study uses the average minutes per visitor metric for the “News/Information” category of websites. Similarly, for political news and social media, the average minutes per visitor metric for Comscore’s “Political” news sub-category and “Social Networking” category of websites were used respectively.

4.2.2 Audience availability

The time spent on particular websites or categories of websites can reveal overall trends across age groups for that website or category. However, when we consider the overall time spent in a month across all websites i.e. web usage as a whole, the metric becomes more indicative of how much time users spent online. Substantial differences in how much time audiences spend across different website categories as a result of the website’s nature of content are balanced out when we consider the total time spent across all websites. Thus, audience availability in the form of total time spent on the internet per month is included as a control variable to account for any effect that may otherwise be explained through people’s increased availability of time that they can spend online. It also helps to account for seasonal variations in web usage behavior in the time series data.

4.2.3 Intervention

The 2020 US presidential election was held on November 3, so this study assumes the 12 months from September 2019 to October 2020 to be in the pre-election condition and November 2020 onwards to be in the post-election condition. Although this operationalization also includes 2 days prior to the election in the post-election period, Comscore only provides monthly aggregations and a more granular resolution of the time series at the daily level is difficult to achieve.

4.3 Analysis

To address RQ1 and RQ2 i.e. explore the relative strength of association between time spent across total internet, overall news category, political news websites, and social networking sites, a series of correlation analyses were conducted for each of the audience groups. Although a correlational analysis may provide some elementary insights on how audience behavior across these categories may be related, it does not quantify the effect of the election on people’s news interest and subsequent engagement.

To address the RQ3 and RQ4, a series of interrupted time series analyses were conducted. A quasi-experimental research design, interrupted time series is a particularly simple yet powerful technique for estimating the causal impact of a natural treatment when random assignment is either unavailable or unfeasible but time series data is available along with a known intervention (Kim and Steiner 2016). Although a randomized controlled trial will always be the gold standard for making causal inferences, quasi-experimental designs are frequently used in other social science disciplines and have been found to provide comparable estimates to RCTs, provided certain conditions are satisfied (Shadish et al. 2002).

Causal impact can be estimated from time series data through several different techniques. For this study, I used the segmented regression method as the 28-month time period is too short for ARIMA modeling (Li et al. 2021). For any interrupted time series design, the periods before the intervention occurrence are considered to be the control group for the time periods post intervention. In a segmented regression model, two separate regression lines are fit to the data corresponding to the pre-treatment and post-treatment time periods. The causal impact of the intervention is estimated by any significant change in the level (intercept) and/or the trend (slope) between the two regression segments. The specification for a simple segmented regression model with a single time series is as follows:

where, Y t is the outcome at time t,

time t is the value of time starting with the first time point (starts at 1) and b 1 is the coefficient for the pre-election slope or trend,

treat t is a dummy variable indicating treatment status (pre or post) and b 2 is the coefficient for the change in level or intercept after the election from the pre-election level b 0, and

∆time t is time after intervention i.e. the effective period after the election (0 for pre-election period, starts at 1 following the election) and b 3 is the coefficient for the post-election slope or trend.

The time spent on social media, political news websites, and all news websites may overlap to some extent if the assumption that news consumption is a salient component of people’s online activities holds true. Hence, to get a more accurate estimate of the impact of the natural intervention, we need to control for the total time spent on the internet. Since this study aims to estimate the impact of the 2020 election and the subsequent events on news interest among the different audience groups that may be explained over and above that of people’s availability for using the internet, the audience availability data for each month is further included in the segmented regression models. Hence, the model is re-specified as:

Before conducting the analyses, I ensured that Comscore’s methodology, weighting, and filtering did not undergo any changes during the 28-month time period. In case Comscore determined any discrepancy in their data, it was usually rectified and users are notified of the changes while downloading the data. While news consumers may have had increased interest during the initial election period and subsequent events involving Donald Trump contesting the election results in November, and again during the January 6 Capitol attack, such interest may not sustain beyond a few months. Hence, this study will only consider any significant change in the amount of time spent between the pre-election and post-election periods as the indicator of a causal impact. Autocorrelation is a common pitfall of working with time series data since the residuals are not independent. To address that issue, each segmented regression model were tested using the Breusch-Godfrey LM test. Wherever significant, the models report the heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation-consistent (Newey-West) standard errors.

5 Findings

Among Gen Z news consumers, there was a moderately strong positive correlation between time spent on political news websites and across all news websites (0.60). Surprisingly, the correlations between time spent on social media with both overall news category (−0.38) as well as political news (−0.48) were both significant and moderately negative. In contrast, none of the correlations between political news, overall news, and social media use for Gen XY audiences were significant. However, when looking at the total US digital population, there was indeed a moderately positive correlation between social media use and overall time spent on news (0.46).

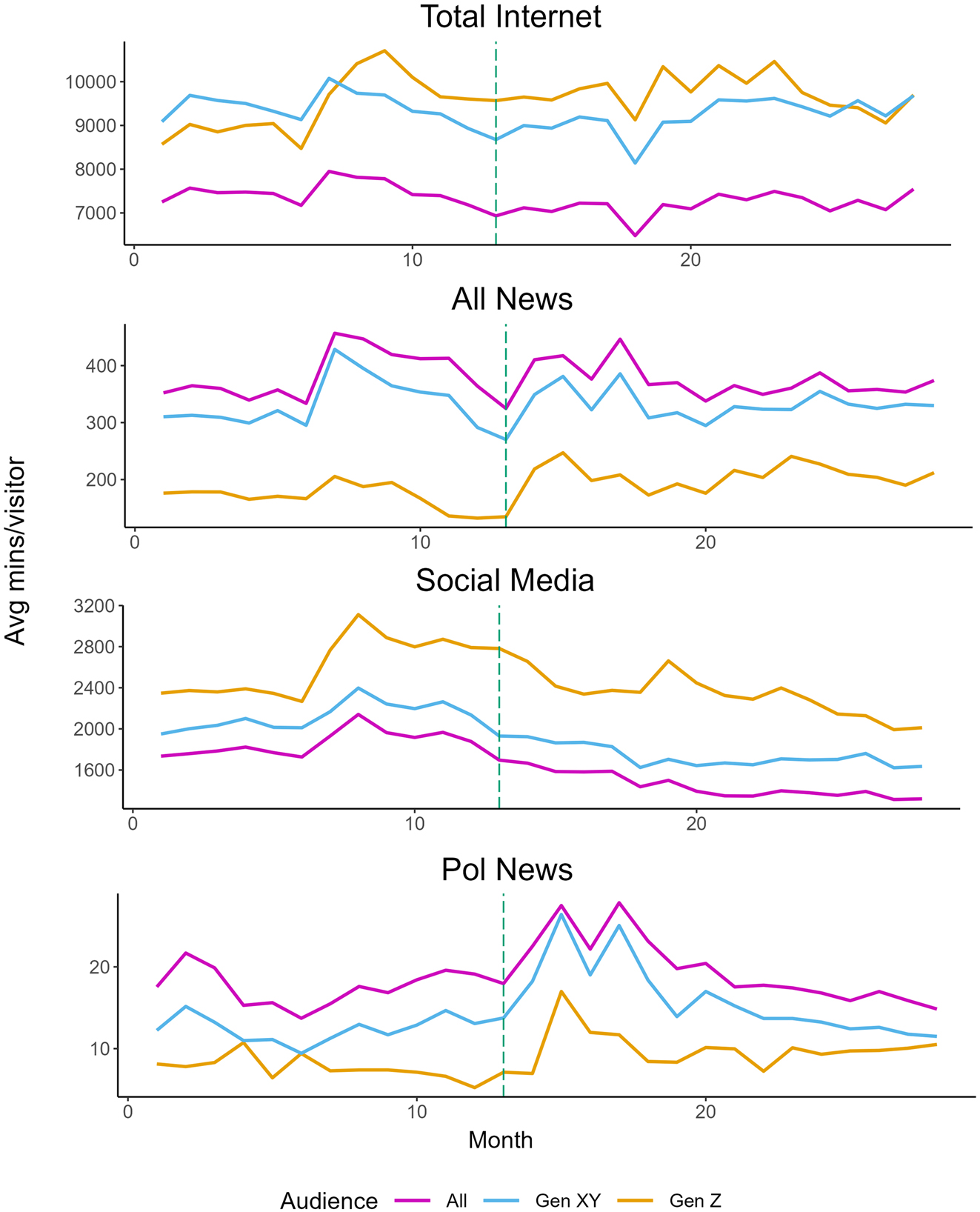

Looking at the total internet use patterns over the 28-month time period (Figure 1), Gen Z and Gen XY audiences roughly spent about the same amount of time each month, which were higher than that of the total population, consistent with previous reports of higher internet use among younger populations. Again, consistent with prior reports of declining news interest, Gen Z audiences consistently spend much less time on news websites (overall and political news) compared to the total population and even Gen XY audiences, while they also spend more time on social media compared to the other two groups.

Trend in time spent across all websites, all news websites, political news websites, and social media sites. The green dashed line indicates the breakpoint in November 2020.

Results from the interrupted time series analyses indicate that the 2020 presidential election and the subsequent events indeed had a significant positive impact on political news consumption (Table 1) among Gen Z (b = 5.66, p < 0.001), Gen XY (b = 8.82, p < 0.001), and the total US internet audiences (b = 6.90, p < 0.001). The impact was significant even after controlling for people’s availability to spend time online, which was not significant for any of the three groups. This is in line with expectations that major political events can indeed result in an increased interest in consuming political news. The fact that the impact was significant for even Gen Z audiences suggests that young adults do not always avoid consuming political news from online news websites, contrary to assumptions that they prefer alternative sources of information.

Segmented regression models for time spent across political news websites.

| Political news | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gen Z | Gen XY | All | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Pre-election trend | −0.12 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

| (0.13) | (0.16) | (0.16) | |

| Post-election | 5.66d | 8.82d | 6.90d |

| (1.30) | (1.81) | (1.78) | |

| Post-election trend | −0.14 | −1.18d | −0.98d |

| (0.18) | (0.26) | (0.23) | |

| Availability (Z) | −0.001 | ||

| (0.001) | |||

| Availability (XY) | −0.0003 | ||

| (0.001) | |||

| Availability (All) | −0.001 | ||

| (0.002) | |||

| Constant | 14.59b | 13.64 | 27.46b |

| (6.23) | (13.39) | (13.27) | |

|

|

|||

| Observations | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| R2 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 0.64 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.45 | 0.65 | 0.58 |

| Residual std. error (df = 23) | 1.71 | 2.34 | 2.27 |

| F statistic (df = 4; 23) | 6.47c | 13.41d | 10.16d |

-

Indicates HAC-corrected standard errors. bp < 0.05; cp < 0.01; dp < 0.001.

The results also indicate that the election had a significant impact on the time spent by Gen Z audiences across all news websites (b = 43.78, p < 0.01), even after controlling for availability. However, the effect was not significant among Gen XY audiences and the total US internet audience (Tables 2 and 3), suggesting that political news consumption may have temporarily increased news interest in general among Gen Z during the post-election period.

Segmented regression models for time spent across all news websites.

| Overall news | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gen Z | Gen XY | All | |

| (1)a | (2)a | (3)a | |

| Pre-election trend | −2.89 | 3.87b | 5.00d |

| (2.11) | (1.81) | (1.47) | |

| Post-election | 43.78c | 20.96 | 19.66 |

| (16.42) | (21.77) | (21.27) | |

| Post-election trend | 3.40 | −8.94c | −10.60d |

| (3.51) | (2.93) | (2.19) | |

| Availability (Z) | 0.02c | ||

| (0.01) | |||

| Availability (XY) | 0.07b | ||

| (0.03) | |||

| Availability (All) | 0.09c | ||

| (0.03) | |||

| Constant | 18.56 | −312.67 | −298.46 |

| (46.12) | (241.76) | (204.75) | |

|

|

|||

| Observations | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| R2 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.52 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.43 |

| Residual std. error (df = 23) | 23.02 | 29.27 | 27.11 |

| F statistic (df = 4; 23) | 5.06c | 3.87b | 6.18c |

-

aIndicates HAC-corrected standard errors. bp < 0.05; cp < 0.01; dp < 0.001.

Segmented regression models for time spent across social media websites.

| Social Media | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gen Z | Gen XY | All | |

| (1)a | (2) | (3)a | |

| Pre-election trend | 18.90b | 13.98b | 9.62 |

| (7.86) | (6.63) | (7.01) | |

| Post-election | −337.48d | −281.17d | −223.34b |

| (90.39) | (72.88) | (88.51) | |

| Post-election trend | −45.06d | −36.98d | −36.26d |

| (10.71) | (10.28) | (8.25) | |

| Availability (Z) | 0.26d | ||

| (0.05) | |||

| Availability (XY) | 0.20d | ||

| (0.06) | |||

| Availability (All) | 0.24c | ||

| (0.08) | |||

| Constant | −19.09 | 153.95 | −20.26 |

| (412.13) | (538.78) | (617.38) | |

|

|

|||

| Observations | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| R2 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.90 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.88 |

| Residual std. error (df = 23) | 105.26 | 94.13 | 82.43 |

| F statistic (df = 4; 23) | 41.88d | 33.63d | 51.88d |

-

aIndicates HAC-corrected standard errors. bp < 0.05; cp < 0.01; dp < 0.001.

Lastly, the election was found to have had a negative impact on social media use across Gen Z audiences (b = −337.48, p < 0.001), Gen XY audiences (b = −281.17, p < 0.001), as well as the total audience (b = −223.34, p < 0.001). While numerous studies and reports using self-reported data have suggested that news audiences increasingly use social media as a source of political news, these findings directly contradict such assumptions. In fact, individuals spent significantly less time on social media platforms during the post-election period, perhaps as a means to avoid politically charged content.

6 Discussion and conclusion

This study contributes to a better understanding of how news consumption patterns may vary generationally as well as provide some indication of how such patterns may shape up in the coming years. Previous research have shown a positive association between online media use and political efficacy among young adults and first-time voters (Ha et al. 2013; Moeller et al. 2014; Ohme et al. 2018). While this study does not examine the effects of online media use among young adults, it does extend our knowledge of the intricacies of online media use patterns themselves during major political events. Overall, the findings suggest that while Gen Z audiences are spending considerably less time on news websites than audiences belonging to the previous generations and the total population, major political events can still increase news consumption through news websites, even if temporarily. Using site visitation data, this study complements the findings by Ha et al. (2013), which indicated differential media use patterns between first-time voters and the general population during the 2012 US presidential election, with college students indicating the internet as a more important political news source. Whereas political news consumption increased significantly among audiences belonging to all the audience groups, the amount of time Gen XY and the total audience spent across all news websites were not significant as compared to Gen Z. This might indicate that the temporary increase in online political news consumption perhaps contributed to a significant increase in the overall news consumption among Gen Z audiences. These results therefore reveal a far more complex dynamic of how audiences consume political news than is typically conceptualized while studying the effects of news consumption on political engagement.

It is particularly notable that social media usage was negatively impacted across all the three groups. While social media usage was positively correlated with overall news usage for the total population, it was insignificant for Generation XY audiences and negatively associated among Gen Z audiences. Although this finding may apparently contradict prior reports suggesting social media as the primary source of news (Newman et al. 2021; Shearer 2021) among younger people, it should also be interpreted in the context of the news avoidance phenomenon among the youth (Edgerly et al. 2018; Villi et al. 2022). Another plausible explanation of the difference in how the association between social media use and overall news use differs across generations is the manner in which these audiences interact with the “news content” that they might encounter on social media platforms. The news-ness of a particular piece of content or information may have different meanings for different groups of people (Edgerly and Vraga 2019). While older adults are still accustomed to a media paradigm where news content is clearly delineated from entertainment content, Gen Z audiences may have a much more fluid conception. Consequently, Gen Z audiences are perhaps less incentivized to visit dedicated news websites either directly or through social media intermediaries if they encounter the same information in a different format from non-news outlets/sources on social media.

There is also some evidence to suggest that while traditional media use has been replaced by digital media, trends in news avoidance have only increased marginally (Karlsen et al. 2020). As Comscore provides weighted average data, the surge in political news consumption of Gen Z audiences cannot be attributed to outliers who have a disproportionate interest in politics. A plausible explanation of these findings is that Gen Z may not be as detached from major political issues as previous self-reported survey studies have indicated. They may indeed seek out information from news websites rather than relying on possibly biased and unreliable information available on social media. This might particularly hold true for major political events such as the 2020 election and the unprecedented series of events that followed afterwards. For the same reason, the negative impact on social media use can be better understood as an indicator of avoiding distressing political content (Villi et al. 2022). Indeed, a recent study indicated that widespread media coverage of particularly polarizing topics can negatively impact social media discourse (Fang and Zhu 2023), which in turn can be detrimental to people’s mental well-being. Considering the events that unfolded immediately after the results were called in favor of Joe Biden, leading up to the Capitol attack, it is more than likely that social media feeds were filled with more politically polarizing content than usual at that time. As such, these findings paint a far more charitable picture of Gen Z’s political awareness than they are usually credited with. Even though this study only considered internet audiences in the US, it is reasonable to expect that the impact of major political events such as national elections on Gen Z news interest and consumption may follow a similar trajectory in countries with robust democracies and a vibrant online news ecosystem. In fact, these findings may be even more pronounced outside the US, especially in countries with higher levels of media trust, which is associated with a preference for mainstream news sources (Kalogeropoulos et al. 2019).

Comparatively, there is considerable generational difference in media use patterns across the three groups studied. While social media use was moderately correlated with total internet use among the total population and Gen Z audiences, it was found insignificant for the Gen XY group. In fact, total internet usage was only correlated with overall news use for this group. While the positive correlation between social media use and overall news consumption among the total US internet audience is consistent with recent reports, it was found insignificant for the Gen XY group and even negatively correlated among Gen Z. It is perhaps yet another indicator of how Gen Z audiences may actually be more discerning of their news sources compared to the general population. Results from the segmented regression analysis also tell a similar story of increased consumption of political news through websites and a significant negative effect on social media use during the election season. In many ways, these findings confirm and further enhance Ha et al.’ (2018) findings that demonstrated a somewhat similar pattern of political news use among college students. But the generational differences evidenced from this study’s findings may also manifest differently in settings beyond the US. For example, a majority of Global South countries are mobile-first markets, where social media and messaging platforms often act as primary sources of both legitimate and misleading political information (Newman et al. 2021). As a result, cleavages along generational cohorts may be less pronounced in the patterns of online political news consumption than the differences attributable to levels of media literacy and political interest.

Taken together, this study offers the following key insights. First, patterns of digital media consumption are not uniform across age groups. More specifically, the assumption that media audiences have a uniform set of motivations and consumption patterns that can consequently explain certain behavioral outcomes can lead to erroneous conclusions. Second, the differences in media consumption patterns across age groups vary across different digital media platforms. Thus, it is important to differentiate between social media news use and news consumed from websites. Further, as shown in this study, news consumption may very well be context dependent and as such, it is important to assess engagement with news sub-categories. While older adults may consume more news in general and prefer other media platforms for obtaining political information, the interest in political news among young adults during major political events may in fact be associated with a significant increase in overall news consumption. As opposed to expectations that audiences might be more active on social media to obtain political news and information, social media use actually decreased significantly during the election. Third, concerns about declining political interest in Gen Z audiences may be overstated. For younger adults, the concept of news is perhaps much broader than those belonging to the previous generations. However, the broader scope does not necessarily exclude consumption of content that we traditionally define as news, as evidenced by the significant surge in engagement with political news during the 2020 election. Faced with this constantly evolving media ecosystem, our definitions of news, its consumption, and its audiences should also be expanded.

Although using observational data in a naturalistic setting makes these findings more robust and externally valid than survey designs, there are some key limitations to this study. First and foremost, the absence of any psychographic data considerably limits the scope of analysis in this study and consequently, is unable to offer more nuanced interpretations of the findings, especially pertaining to the mechanisms and motivations of news consumption across generations. Next, this study included 2 days prior to the election in the post-election time period, which may have confounded the results. Unfortunately, in the absence of more granular data at the daily level from Comscore, this was unavoidable. The operationalization of media consumption as the average minutes spent per month may not adequately indicate people’s engagement with news content. Using multi-modal datasets that combine longitudinal web traffic data with self-reported psychographic variables can significantly alleviate some of these problems. The age filters offered by Comscore also posed a challenge in defining the generational cohorts. Although this study’s design considered the 25–49 age group as representative of people who grew up in the 80s and early-90s, it is plausible that there exists considerable difference in the online media use patterns between millennials and Gen X. This study also focused on broad categories of political news websites, all news websites, and all social media websites. It is likely that usage patterns may vary across individual websites. Lastly, the patterns observed in this study are specific to the US. As discussed previously, the impact of major political events on news interest and generational patterns of news use are likely to vary in other countries due to a range of factors such as robustness of media ecosystems, type of administration, modes of internet access, levels of media literacy, etc. As such, future studies should focus on investigating these patterns using observational data in non-US contexts to enhance our understanding of how news audiences and indeed, the definition of news itself is evolving. Nevertheless, this study’s quasi-experimental design using observational data adds considerable nuance to our present understanding of generational online news use patterns, while also offering evidence that challenge some existing notions of Gen Z news audience behavior, especially when it comes to political news consumption.

References

Ahmadi, Mousa & Donghee Yvette Wohn. 2018. The antecedents of incidental news exposure on social media. Social Media + Society 4(2). 205630511877282. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118772827.Search in Google Scholar

Benkler, Yochai. 2011. A free irresponsible press: Wikileaks and the battle over the soul of the networked fourth estate. Harvard Civil Rights – Civil Liberties Law Review 46. 311.10.7146/politik.v15i2.27508Search in Google Scholar

Bolin, Goran. 2016. Media generations: Experience, identity and mediatised social change. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Boulianne, Shelley & Yannis Theocharis. 2020. Young people, digital media, and engagement: A meta-analysis of research. Social Science Computer Review 38(2). 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318814190.Search in Google Scholar

Carothers, Thomas & Andrew O’Donohue. 2019. Democracies divided: The global challenge of political polarization. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chae, Younggil, Sookjung Lee & Yeolib Kim. 2019. Meta-analysis of the relationship between internet use and political participation: Examining main and moderating effects. Asian Journal of Communication 29(1). 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2018.1499121.Search in Google Scholar

Comscore. 2013. ComScore media metrix description of methodology. https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2014/03/comScore-Media-Metrix-Description-of-Methodology.pdf (accessed 1 August 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Davis, Nicholas T. & Johanna L. Dunaway. 2016. Party polarization, media choice, and mass partisan-ideological sorting. Public Opinion Quarterly 80(S1). 272–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw002.Search in Google Scholar

Diehl, Trevor, Matthew Barnidge & Homero Gil De Zúñiga. 2019. Multi-platform news use and political participation across age groups: Toward a valid metric of platform diversity and its effects. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96(2). 428–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018783960.Search in Google Scholar

Dimock, Michael. 2019. Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/ (accessed 1 August 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Edgerly, Stephanie & Emily K. Vraga. 2019. News, entertainment, or both? Exploring audience perceptions of media genre in a hybrid media environment. Journalism 20(6). 807–826. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917730709.Search in Google Scholar

Edgerly, Stephanie, Emily K. Vraga, Leticia Bode, Kjerstin Thorson & Esther Thorson. 2018. New media, new relationship to participation? A closer look at youth news repertoires and political participation. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 95(1). 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699017706928.Search in Google Scholar

Fang, Anna & Haiyi Zhu. 2023. Measuring the stigmatizing effects of a highly publicized event on online mental health discourse. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’23), 1–18. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery.10.1145/3544548.3581284Search in Google Scholar

Flamino, James, Alessandro Galeazzi, Stuart Feldman, Michael W. Macy, Brendan Cross, Zhenkun Zhou, Matteo Serafino, Alexandre Bovet, Hernán A. Makse & Boleslaw K. Szymanski. 2023. Political polarization of news media and influencers on Twitter in the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections. Nature Human Behaviour 7(6). 904–916. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01550-8.Search in Google Scholar

Fry, Richard. 2017. Gen Zers, Millennials and Gen Xers outvoted Boomers and older generations in 2016 election. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2017/07/31/gen-zers-millennials-and-gen-xers-outvoted-boomers-and-older-generations-in-2016-election/ (Accessed 1 August 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Nakwon Jung & Sebastián Valenzuela. 2012. Social media use for news and individuals’ social capital, civic engagement and political participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17(3). 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01574.x.Search in Google Scholar

Goyanes, Manuel, Alberto Ardèvol-Abreu & Homero Gil de Zúñiga. 2023. Antecedents of news avoidance: Competing effects of political interest, news overload, trust in news media, and “news finds me” perception. Digital Journalism 11(1). 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1990097.Search in Google Scholar

Ha, Louisa S., Fang Wang, Ling Fang, Chen Yang, Xiao Hu, Liu Yang, Fan Yang, Ying Xu & David Morin. 2013. Political efficacy and the use of local and national news media among undecided voters in a swing state: A study of general population voters and first-time college student voters. Electronic News 7(4). 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1931243113515678.Search in Google Scholar

Ha, Louisa, Ying Xu, Chen Yang, Fang Wang, Liu Yang, Mohammad Abuljadail, Xiao Hu, Weiwei Jiang & Itay Gabay. 2018. Decline in news content engagement or news medium engagement? A longitudinal analysis of news engagement since the rise of social and mobile media 2009–2012. Journalism 19(5). 718–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916667654.Search in Google Scholar

Head, Alison J., John Wihbey, P. Takis Metaxas, Margy MacMillan & Dan Cohen. 2018. How students engage with news: Five takeaways for educators, journalists, and librarians. Executive summary. Project Information Literacy Research Institute. https://projectinfolit.org/pubs/news-study/pil_news-study_2018-10-16.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2023).10.2139/ssrn.3503183Search in Google Scholar

Igielnik, Ruth, Keeter Scott & Hannah Hartig. 2021. Behind Biden’s 2020 victory. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/06/30/behind-bidens-2020-victory/ (Accessed 1 August 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Kalogeropoulos, Antonis, Jane Suiter, Linards Udris & Mark Eisenegger. 2019. News media trust and news consumption: Factors related to trust in news in 35 countries. International Journal of Communication 13(0). 22.Search in Google Scholar

Karlsen, Rune, Audun Beyer & Kari Steen-Johnsen. 2020. Do high-choice media environments facilitate news avoidance? A longitudinal study 1997–2016. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 64(5). 794–814. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2020.1835428.Search in Google Scholar

Kemp, Simon. 2022. Digital 2022: Global overview report. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report (accessed 1 August 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Yongnam & Peter Steiner. 2016. Quasi-experimental designs for causal inference. Educational Psychologist 51(3–4). 395–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2016.1207177.Search in Google Scholar

Konitzer, Tobias, Jennifer Allen, Stephanie Eckman, Baird Howland, Markus Mobius, David Rothschild & Duncan J. Watts. 2021. Comparing estimates of news consumption from survey and passively collected behavioral data. Public Opinion Quarterly 85(S1). 347–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfab023.Search in Google Scholar

Kramp, Leif & Wiebke Loosen. 2018. The transformation of journalism: From changing newsroom cultures to a new communicative orientation? In Andreas Hepp, Andreas Breiter & Uwe Hasebrink (eds.). Communicative figurations: Transforming communications in times of deep mediatization. Cham: Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-319-65584-0_9Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Nam-Jin, Dhavan V. Shah & Jack M. McLeod. 2013. Processes of political socialization: A communication mediation approach to youth civic engagement. Communication Research 40(5). 669–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212436712.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Lihua, Meaghan S. Cuerden, Bian Liu, Salimah Shariff, Arsh K. Jain & Madhu Mazumdar. 2021. Three statistical approaches for assessment of intervention effects: A primer for practitioners. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 14. 757–770. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S275831.Search in Google Scholar

Matthes, Jörg. 2022. Social media and the political engagement of young adults: Between mobilization and distraction. Online Media and Global Communication 1(1). 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/omgc-2022-0006.Search in Google Scholar

Milkman, Ruth. 2017. A new political generation: Millennials and the post-2008 wave of protest. American Sociological Review 82(1). 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416681031.Search in Google Scholar

Mitchell, Amy, Jeffrey Gottfried & Katerina Eva Matsa. 2015. Millennials and political news. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2015/06/01/millennials-political-news/ (Accessed 1 August 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Moeller, Judith, Claes de Vreese, Esser Frank & Ruth Kunz. 2014. Pathway to political participation: The influence of online and offline news media on internal efficacy and turnout of first-time voters. American Behavioral Scientist 58(5). 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213515220.Search in Google Scholar

Möller, Judith, Robbert Nicolai Van De Velde, Lisa Merten & Cornelius Puschmann. 2020. Explaining online news engagement based on browsing behavior: Creatures of habit? Social Science Computer Review 38(5). 616–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319828012.Search in Google Scholar

Nelson, Jacob L. 2021. Imagined audiences: How journalists perceive and pursue the public. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780197542590.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Nelson, Jacob L. & James G. Webster. 2016. Audience currencies in the age of big data. The International Journal on Media Management 18(1). 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2016.1166430.Search in Google Scholar

Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andi, Craig T. Robertson & Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2021. Reuters institute digital news report 2021. SSRN Scholarly Paper Rochester. NY: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.Search in Google Scholar

Ognyanova, Katherine. 2020. Misinformation in action: Fake news exposure is linked to lower trust in media, higher trust in government when your side is in power. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 1(4). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-024.Search in Google Scholar

Ohme, Jakob, Claes H. de Vreese & Erik Albaek. 2018. The uncertain first-time voter: Effects of political media exposure on young citizens’ formation of vote choice in a digital media environment. New Media & Society 20(9). 3243–3265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817745017.Search in Google Scholar

Oser, Jennifer & Shelley Boulianne. 2020. Reinforcement effects between digital media use and political participation: A meta-analysis of repeated-wave panel data. Public Opinion Quarterly 84(S1). 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa017.Search in Google Scholar

Park, Sora, Caroline Fisher, Flew Terry & Uwe Dulleck. 2020. Global mistrust in news: The impact of social media on trust. The International Journal on Media Management 22(2). 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2020.1799794.Search in Google Scholar

Parker, Kim, Nikki Graf & Igielnik Ruth. 2019. Generation Z looks a lot like millennials on key social and political issues. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/01/17/generation-z-looks-a-lot-like-millennials-on-key-social-and-political-issues/ (Accessed 1 August 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Poindexter, Paula M. & Maxwell E. McCombs. 2001. Revisiting the civic duty to keep informed in the new media environment. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78(1). 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900107800108.Search in Google Scholar

Prensky, Marc. 2001. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 2: Do they really think differently? On the Horizon 9(6). 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424843.Search in Google Scholar

Prensky, Marc. 2009. H. Sapiens digital: From digital immigrants and digital natives to digital wisdom. Innovate Journal of Online Education 5(3).Search in Google Scholar

Riccardi, Nicholas. 2020. Here’s the reality behind Trump’s claims about mail voting. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-joe-biden-election-2020-donald-trump-elections-3e8170c3348ce3719d4bc7182146b582 (Accessed 1 August 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Robertson, Ronald, E., Jon Green, Damian, J., Katherine Ognyanova, Christo Wilson & David Lazer. 2023. Users choose to engage with more partisan news than they are exposed to on Google Search. Nature 618. 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06078-5.Search in Google Scholar

Shadish, William R., Thomas D. Cook & Donald Thomas Campbell. 2002. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.Search in Google Scholar

Shearer, Elisa. 2021. More than eight-in-ten Americans get news from digital devices. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/01/12/more-than-eight-in-ten-americans-get-news-from-digital-devices/ (Accessed 1 August 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Stier, Sebastian, Mangold Frank, Michael Scharkow & Johannes Breuer. 2022. Post post-broadcast democracy? News exposure in the age of online intermediaries. American Political Science Review 116(2). 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001222.Search in Google Scholar

Tamboer, Sanne L, Mariska Kleemans & Serena Daalmans. 2022. ‘We are a neeeew generation’: Early adolescents’ views on news and news literacy. Journalism 23(4). 806–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920924527.Search in Google Scholar

Taneja, Harsh. 2016. Using commercial audience measurement data in academic research. Communication Methods and Measures 10(2–3). 176–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2016.1150971.Search in Google Scholar

Taneja, Harsh. 2020. The myth of targeting small, but loyal Niche audiences: Double-Jeopardy effects in digital-media consumption. Journal of Advertising Research 60(3). 239–250. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2019-037.Search in Google Scholar

Taneja, Harsh, James G. Webster, Edward C. Malthouse & Thomas B. Ksiazek. 2012. Media consumption across platforms: Identifying user-defined repertoires. New Media & Society 14(6). 951–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811436146.Search in Google Scholar

Toff, Benjamin & Antonis Kalogeropoulos. 2020. All the news that’s fit to ignore: How the information environment does and does not shape news avoidance. Public Opinion Quarterly 84(S1). 366–390. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa016.Search in Google Scholar

Twenge, Jean M., Gabrielle N. Martin & Brian H. Spitzberg. 2019. Trends in U.S. Adolescents’ media use, 1976–2016: The rise of digital media, the decline of TV, and the (near) demise of print. Psychology of Popular Media Culture 8. 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000203.Search in Google Scholar

Vaala, Sarah E. & Amy Bleakley. 2015. Monitoring, mediating, and modeling: Parental influence on adolescent computer and internet use in the United States. Journal of Children and Media 9(1). 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2015.997103.Search in Google Scholar

Villi, Mikko, Tali Aharoni, Keren Tenenboim-Weinblatt, Pablo J. Boczkowski, Kaori Hayashi, Eugenia Mitchelstein, Akira Tanaka & Neta Kligler-Vilenchik. 2022. Taking a break from news: A five-nation study of news avoidance in the digital era. Digital Journalism 10(1). 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1904266.Search in Google Scholar

Webster, James G. 2014. The marketplace of attention: How audiences take shape in a digital age. Cambridge: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9892.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Wojcieszak, Magdalena, Sjifra de Leeuw, Ericka Menchen-Trevino, Seungsu Lee, Ke M. Huang-Isherwood & Brian Weeks. 2021. No polarization from Partisan News: Over-time evidence from trace data. The International Journal of Press/Politics 28(3). 601–626, 19401612211047190. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211047194.Search in Google Scholar

Wonneberger, Anke, Klaus Schoenbach & Lex van Meurs. 2011. Interest in news and politics—or situational determinants? Why people watch the news. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 55(3). 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2011.597466.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Angela Xiao & Harsh Taneja. 2021. Platform enclosure of human behavior and its measurement: Using behavioral trace data against platform episteme. New Media & Society 23(9). 2650–2667. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820933547.Search in Google Scholar

York, Chance & Rosanne M. Scholl. 2015. Youth antecedents to news media consumption: Parent and youth newspaper use, news discussion, and long-term news behavior. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 92(3). 681–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015588191.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Essay

- Gen Z’s social media use and global communication

- Research Articles

- Identity, migration, and social media: Generation Z in USMCA

- Online news platforms still matter: generational news consumption patterns during the 2020 presidential election

- Differences in perceived influencer authenticity: a comparison of Gen Z and Millennials’ definitions of influencer authenticity during the de-influencer movement

- Why does Gen Z watch virtual streaming VTube anime videos with avatars on Twitch?

- Para-kin relationship between fans and idols: a qualitative analysis of fans’ motivations for purchasing idol-dolls

- From the Traditionalists to GenZ: conceptualizing intergenerational communication and media preferences in the USA

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- Co-writing journalism on TikTok: media legitimacy and edutainment communities

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Essay

- Gen Z’s social media use and global communication

- Research Articles

- Identity, migration, and social media: Generation Z in USMCA

- Online news platforms still matter: generational news consumption patterns during the 2020 presidential election

- Differences in perceived influencer authenticity: a comparison of Gen Z and Millennials’ definitions of influencer authenticity during the de-influencer movement

- Why does Gen Z watch virtual streaming VTube anime videos with avatars on Twitch?

- Para-kin relationship between fans and idols: a qualitative analysis of fans’ motivations for purchasing idol-dolls

- From the Traditionalists to GenZ: conceptualizing intergenerational communication and media preferences in the USA

- Featured Translated Research Outside the Anglosphere

- Co-writing journalism on TikTok: media legitimacy and edutainment communities