The preparation of cellulose acetate capsules using emulsification techniques: high-shear bulk mixing and microfluidics

-

Katarzyna Mystek

, Bo Andreasson

Abstract

This work describes an emulsification-solvent-evaporation method for the preparation of liquid-filled capsules made from cellulose acetate. Two different emulsification techniques were applied: bulk emulsification by high-shear mixing, and droplet generation using microfluidics. The bulk emulsification method resulted in the formation of oil-in-water emulsions composed of an organic mixture of isooctane and cellulose acetate in methyl acetate, and an aqueous phase of high-molecular-weight polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Upon the solvent evaporation, the emulsion droplets evolved into isooctane-filled cellulose acetate capsules. In contrast, microfluidics led to the formation of monodisperse droplets composed of the aqueous PVA solution dispersed in the organic phase. Upon the solvent evaporation, the emulsion droplets evolved into water-filled cellulose acetate capsules. Owing to the thermoplastic properties of the cellulose acetate, the capsules formed with the bulk mixing demonstrated a significant expansion when exposed to an increased temperature. Such expanded capsules hold great promise as building blocks in lightweight materials.

1 Introduction

Cellulose is a polysaccharide that can be extracted from different natural sources, such as cotton, wood pulp, corn, rice and wheat straw, amongst others. In its native form cellulose exhibits very good mechanical performance and good chemical stability, due to a highly ordered and packed structure. The linear organization of cellulose chains facilitates formation of a crystalline structure containing inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds as well as van der Waals forces. The crystalline structure and the ordering of the glucan chains create the basis for the excellent mechanical properties of plant fiber walls and consequently also the cellulose-rich fibers (Wohlert et al. 2021). In addition to good mechanical properties, the strong inter- and intramolecular interactions also result in a water insolubility despite the overall hydrophilic nature of the glucan chains. The poor solubility of cellulose and its tendency to degrade prior to melting, limits the commercial use of cellulose in common polymer processing and molding technologies. As a result, chemically modifying cellulose to produce cellulose derivatives is often necessary to expand the applicability of cellulose beyond the native polymer (Edgar et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2020). One common commercially available cellulose derivative is cellulose acetate (CA), which today can be found in textiles, plastic tools, hygiene products, coatings and packaging materials. Owing to its good biocompatibility, CA has been also used in drug delivery and tissue engineering applications (Edgar et al. 2001; Huang and Dean 2020). CA is prepared via acetylation of cellulose, which is a well-established and effective method to reduce the ordering of the cellulose nanostructure. By altering the degree of substitution, it is possible to tune the thermal, chemical, physical and mechanical properties of the final material. CAs with higher degrees of substitution (DS) (e.g. DS = 2.5) are characterized by an enhanced solubility in relatively benign organic solvents, such as acetone or methyl acetate, an increased hydrophobicity, and processability typical for thermoplastic materials (Samios et al. 1997; Zhou et al. 2016).

Recently, the application of cellulose derivatives has moved beyond conventional consumer products and has been used to prepare more advanced materials in the form of fibers, scaffolds, membranes, as well as nano- and microspheres (Khoshnevisan et al. 2018; Mao et al. 2018; Murtinho et al. 1998; Soppimath et al. 2001; Su et al. 2020; Tan et al. 2020; Topel et al. 2021). The latter have gained both scientific and commercial interest due to their potential use as carriers for controlled release of active components and as stationary phases in chromatographic column systems. Since most commercial cellulose derivatives are soluble in volatile organic solvents, one of the more common techniques used to form spherical particles is emulsification followed by evaporation of the solvent (Gericke et al. 2013; Zhao and Winter 2015). This approach relies on the formation of an emulsion of organic solution of a polymer in water, followed by the evaporation of the organic solvent and simultaneous organization of the polymer at the water-solvent interface (Desgouilles et al. 2003). Typically, the water phase also contains surfactants to stabilize the emulsion droplets. In addition to the polymer, the organic phase can also contain other miscible components, which can be further encapsulated within the sphere. As a result, the emulsification–solvent evaporation method can be used to prepare both solid and liquid-filled spherical particles, typically referred to as beads and capsules, respectively (Staff et al. 2013).

Simple mechanical mixing is a direct and conventional emulsification method, which has been used for the fabrication of spherical cellulose-based micro- and nanosized materials (Döge et al. 2016; Joshy et al. 2017; Tirado et al. 2019; Vidal-Romero et al. 2019; Volmajer Valh et al. 2017). Although this method often leads to polydisperse emulsion droplets, it is still preferred among other emulsification techniques, as it allows for a good, simple and fast optimization of the final properties of materials. Recent progress shows, however, that to achieve a better control of the emulsion formation dynamics and to minimize disturbance from the surrounding chemical environment, more advanced emulsification methods, such as those achieved via microfluidics may be beneficial (Liu et al. 2020; Zhao 2013).

To the best of our knowledge, there has yet to be a report of the preparation of liquid-filled capsules made from CA using microfluidics, where the co-solvent of the organic phase is partially miscible with the aqueous phase. Furthermore, there are no studies introducing thermo-expandable properties of isooctane-filled CA microcapsules. A recent review by Carvalho et al. (2021) also shows that the majority of research related to CA capsules is focused on the evaluation of the encapsulation and controlled release properties of such materials. Therefore, the aim of the present work was to clarify if it is possible to prepare liquid-filled CA capsules by using high shear mixing and/or microfluidics, and to determine if such prepared materials exhibit tendency for thermal expansion considering the thermoplastic properties of the CA.

In this study, liquid-filled capsules were prepared from commercially available cellulose acetate (DS = 2.45) that was dissolved in methyl acetate. The capsules were formed using an emulsification–solvent evaporation method, where the emulsification was achieved through two different techniques: high-shear mixing and microfluidics. Furthermore, two different strategies to stabilize the capsules were adopted; incorporation of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) or cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs). The structure and surface morphology of formulated capsules were studied with electron microscopy. Furthermore, the cross-section of capsules was imaged with a focused ion beam scanning electron microscope and a transmission electron microscope. The efficiency of encapsulation of isooctane within the capsule wall was determined using thermal analysis, whereas the behavior of capsules at elevated temperatures could be observed by using an optical microscope combined with a heating chamber. The process of mixing of the organic and water phases in the microfluidic flow-focusing junction was investigated by staining the phases with oil red and methylene blue, respectively.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

Isooctane (anhydrous, 99.8 %), methyl acetate (anhydrous, 99.5 %), sulfuric acid, methylene blue, low- and high-molecular-weight polyvinyl alcohol (M w = 13,000–23,000, 87–89 % hydrolyzed and M w = 85,000–124,000, 87–89 % hydrolyzed, respectively) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Oil red was purchased from Fluka. The chemicals were used as received without any further purification. Cellulose acetate with a degree of substitution of 2.45 and M w ∼ 30,000 was purchased from Eastman. Ashless Whatman 1703-050 filter paper was purchased from GE Healthcare.

2.2 Preparation of CNCs

CNCs were prepared via sulfuric acid hydrolysis of ashless Whatman cotton filter papers following an earlier described procedure (Mystek et al. 2020). Briefly, 40 g of cotton filter was hydrolyzed in 64 wt% sulfuric acid at 45 °C for 45 min under continuous stirring. The suspension was washed using three steps of rinsing and centrifugation, followed by dialysis against Milli-Q water until the pH of the water was between 5 and 6. This suspension was then sonicated (Vibra-Cell CV33) three times for 10 min in an ice bath at 60 % amplitude, filtered through a Whatman glass fiber filter paper and stored at 4 °C. The CNCs had a sulfur content of 0.55 ± 0.02 wt% measured by conductometric titration and a zeta potential of −25 mV (Zetasizer Nano ZS; Malvern Instruments) (Abitbol et al. 2013).

2.3 Formation of capsules by high-shear mixing

Isooctane-filled CA capsules were prepared following two specific procedures. To form the first set of capsules (hereafter referred to as Capsules S1), 0.1 g of CA was dissolved in 1.4 g of methyl acetate (co-solvent) and mixed with isooctane, where the concentration of isooctane was 0.2 g per gram of CA. The mixture was first agitated for at least 10 h in a closed vial equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar. Following this, 1.5 g of the organic mixture was slowly added into 10.5 g of high-molecular-weight PVA solution at a concentration of 2.0 wt%, while continuously and vigorously mixing the solution with an IKA Ultra Turrax at 6000 rpm for 2 min. This oil-in-water emulsion containing isooctane/cellulose acetate/methyl acetate droplets in an aqueous PVA solution was then poured into 30 mL of Milli-Q water under mixing (magnetic stirrer). Subsequently, the methyl acetate was allowed to evaporate (in an open vial) under gentle stirring to initiate formation of the final capsules with a solid shell. Complete removal of methyl acetate was done by evaporation in the fume hood under gentle stirring on a magnetic stirrer for at least 12 h. The capsules were finally washed with at least 100 mL of water by continuous filtration on a Merck MF-Millipore membrane with the pore size of 0.65 µm (Andreasson et al. 2020).

The second set of capsules (hereafter referred to as Capsules S2) was prepared by dissolving 0.1 g of CA in 9.9 g of methyl acetate (co-solvent) and mixing the solution with isooctane, where the concentration of isooctane was 0.2 g per gram of CA. After at least 10 h of agitation on a magnetic stirrer, 1.5 g of the organic mixture was slowly added to 5 g of high-molecular-weight PVA solution at a concentration of 2.0 wt%, while continuously and vigorously mixing the solution with an IKA Ultra Turrax at 6000 rpm for 2 min. After emulsification, the methyl acetate was allowed to evaporate (in an open vial) under gentle stirring to initiate the formation of the final capsules with a solid shell. Complete removal of methyl acetate was done by evaporation in the fume hood under gentle stirring on a magnetic stirrer for at least 12 h. The capsules were finally washed with at least 100 mL of water by continuous filtration on a Merck MF-Millipore membrane with the pore size of 0.65 µm.

2.4 Formation of capsules by microfluidic flow focusing

A flow-focusing chip with hydrophilic channels, tubing and all connectors needed were purchased from Dolomite Microfluidics, Royston, UK. Luer lock syringes of 5 mL having a diameter of 11 mm were purchased from VWR, and two syringe pumps (NE-1000) were purchased from AB FIA, Södra Sandby, Sweden. The microfluidic chip had an outlet channel size of 30 µm and is suitable for generating highly monodisperse organic-in-aqueous droplets with diameters between 10 and 28 µm. Two phases were mixed in the junction of the chip: a dispersed phase (central channel) composed of a mixture of isooctane and cellulose acetate in methyl acetate; and a continuous phase (side channels) containing an aqueous solution of low-molecular-weight PVA. The CA solution was used at a concentration of 1.0 wt% and mixed with isooctane to a final mass ratio of 5:1. The formation of stable and monodisperse emulsion droplets was adjusted by changing the concentration of PVA and the flow rates of the phases. After optimization, constant and stable droplet generation was achieved at two optimum conditions: i) when PVA was used at the concentration of 0.008 wt% and the flow rates of the continuous and dispersed phases were 0.067 and 0.67 μL/min, respectively; ii) when PVA was used at the concentration of 0.05 wt% and the flow rates of the continuous and dispersed phases were 0.067 and 0.47 μL/min, respectively. The formulated droplets were further stabilized in an intensively stirred collecting bath containing 4 mL of high-molecular-weight PVA solution (2.0 wt%) or CNCs dispersion (1.45 wt%). Capsules were typically collected over a period of 6 h, after which the dispersion was left to gently stir for at least 12 h in an open vial to form liquid-filled capsules by slow evaporation of methyl acetate. The microcapsules were washed with Milli-Q water by centrifugation at 10 000 rpm for 3 min.

2.5 Viscosity of solutions

Kinematic viscosity of the isooctane/cellulose acetate mixture in methyl acetate and PVA solutions at different concentrations was determined using an iVisc capillary viscometer with a thermostat ET 15 S (LAUDA, Königshofen, Germany). The measurements were performed using an EGV 702 capillary at a temperature of 23 °C. Each solution was measured three times.

2.6 Interfacial tensions of solutions

Interfacial tension measurements were performed at 23 °C and 50 % relative humidity using an optical tensiometer (Theta Lite, Biolin Scientific) equipped with a camera. Interfacial tension was measured via the pendent drop method using a 3 μL droplet of PVA solution in a bath composed of a mixture of isooctane and cellulose acetate in methyl acetate. The interfacial tension was determined using image analysis and a Young-Laplace fitting in the instrument software. The average value is calculated from three measurements.

2.7 Determination of capsule dimensions and morphology

An optical microscope (VisiScope, VWR) equipped with VisiCam 16 Plus camera (IS VisiCam Image Analyser 3.9.0.605 software) was used to image the CA capsules. The dimensions of the wet capsules were measured using Image J and presented in a size distribution profile. The morphology of the dry capsules was further characterized with a Hitachi S-4800 field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) operating at high vacuum. Prior to imaging, to eliminate charging effects of the samples, all samples were coated with Pt–Pd in a Cressington 208HR High Resolution Sputter Coater for 28 s.

2.8 Imaging of capsule internal structure

Ultrathin 70 nm thick sections were prepared to image the structure of Capsules S1 via transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The samples were examined with Talos 120 C (FEI, The Netherlands) operating at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV. The capsules were first dried in the fume hood for 2–3 days. Then, Spurr resin (Taab Laboratory Equipment Ltd, UK) was added to the capsules and the sample was left for 4–6 h under ambient conditions to assure infiltration of the resin, followed by overnight polymerization at 65 °C. Sectioning of the samples was done using an ultra-microtome (Reichert/Leica UltraCut S). The sections were collected on TEM copper grids (100 mesh) and stained for 30 min at room temperature in RuO4 vapor (Polysciences 0.5 % RuO4) by placing a few drops of the solution next to the grids. In addition to TEM, a focused ion beam (FIB) SEM Tescan GAIA3 was used to collect and image cross sections of the capsules (Giannuzzi and Stevie 2005). Prior to FIB-SEM imaging, the capsules were dried under ambient conditions and mounted with double-adhesive conductive carbon tape onto an aluminum stub, followed by deposition of a thin layer of Pt–Pd in a Cressington 208HR High Resolution Sputter Coater for 56 s. Due to the poor conductivity of the capsules, the ion beam and electron beam parameters had to be optimized according to a protocol described in the literature (Fager et al. 2020). The optimized ion beam parameters used for milling were 30 keV and 1 nA. The electron beam parameters used for imaging were 1 kV, 1 pA. A mid-angle backscattered electron detector was used for imaging.

2.9 Thermogravimetric analysis

TGA measurements were conducted using a Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC 1 STARe System under a constant nitrogen flow of 50 mL/min. A minimum of 2 mg of dry sample was heated from 25 to 400 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min and then from 400 to 600 °C at a rate of 15 °C/min. The capsules were previously dried in ambient conditions for four days. PVA and CA were also tested in their delivered powder form. For this purpose, a minimum of 5 mg of sample was heated from 25 to 600 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min.

2.10 Differential scanning calorimetry

DSC measurements were conducted using a Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC 1 STARe System under a constant nitrogen flow of 50 mL/min. A minimum of 5 mg of CA powder was firstly heated from 25 to 240 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min, then immediately quenched to −50 °C and heated again from −50 to 240 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min. The T g of the polymer was determined using the curve of the second heating cycle.

2.11 Expansion of dry capsules by an increased temperature

Thermal expansion, i.e. the increase in capsule volume, was studied using a microscope fitted with careful temperature control. This was performed by placing the capsules on a glass slide in a heating chamber (Linkam LTS420) combined with an optical microscope (Leica DM1000). The heating rate of the chamber was controlled and set to 20 °C/min. The expansion was tested in the temperature range from 25 to 230 °C. The dimensions of the spheres were continuously recorded by using an optical microscope camera (Point Grey Grasshopper3).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Microcapsules formed by the emulsification–solvent evaporation method

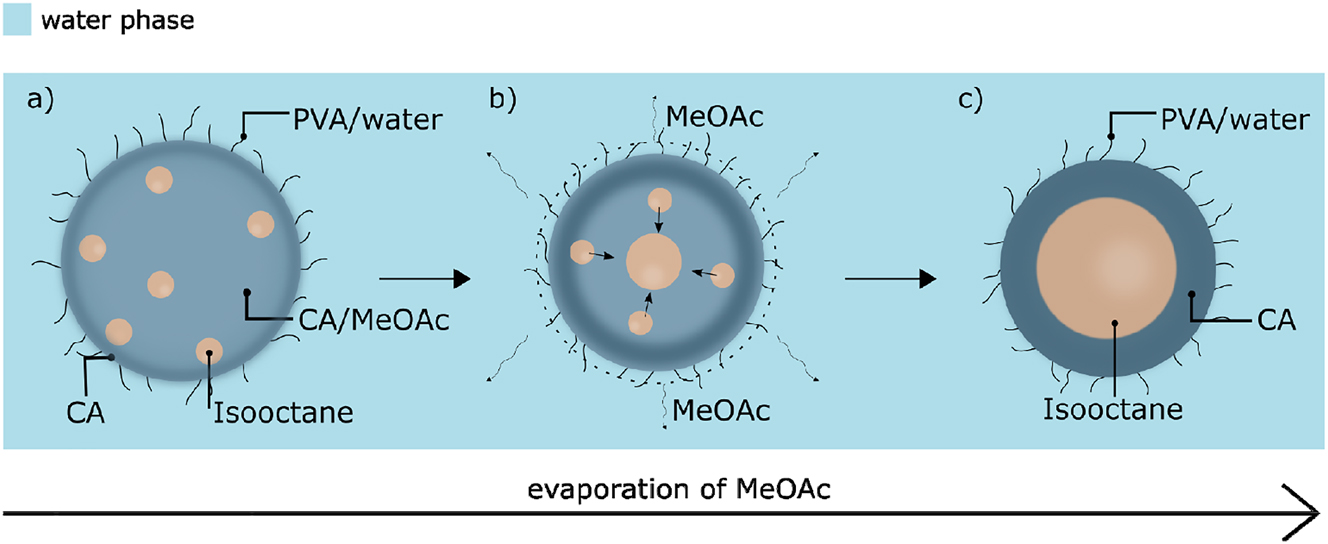

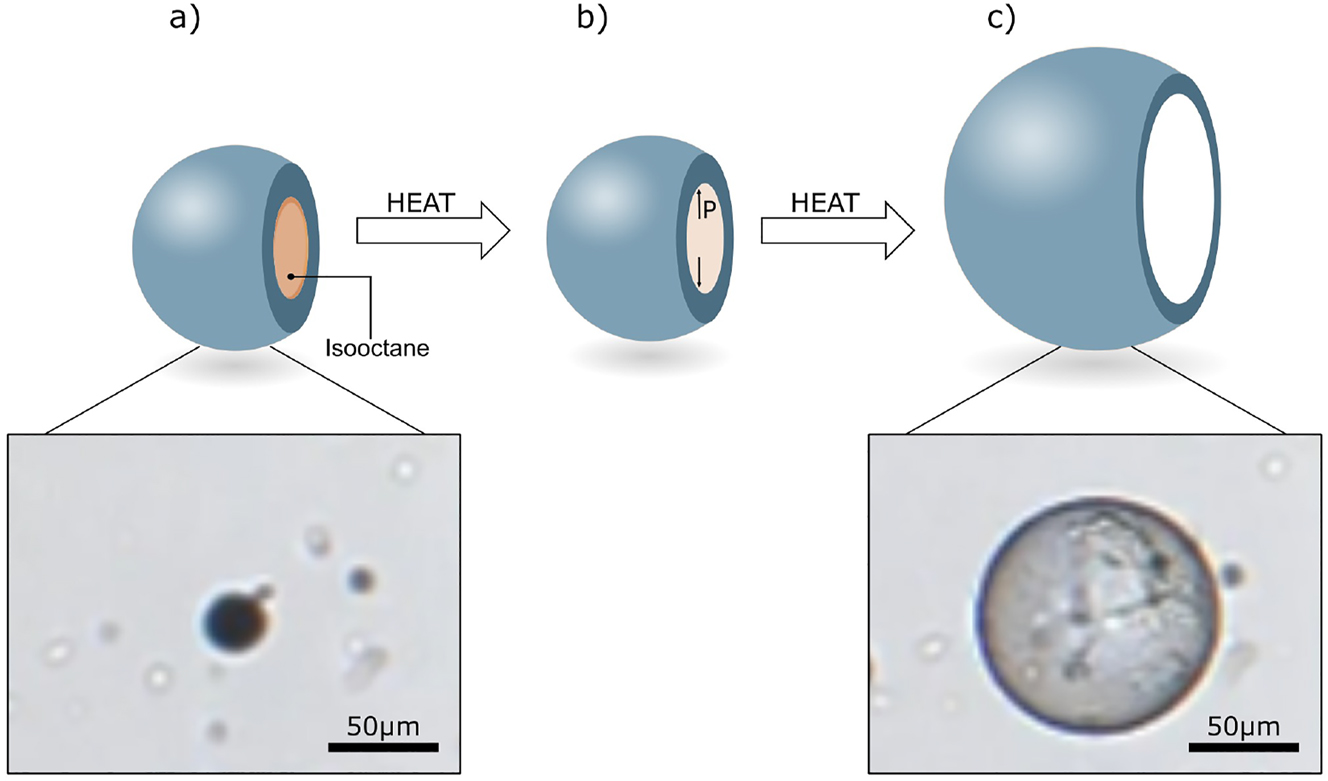

The mechanism of capsule formation via emulsification – solvent evaporation is strictly dependent on formulation parameters such as the structure of the polymer, the properties of the encapsulated liquid, the type of the solvent used and the presence of stabilizers (Li et al. 2008). In this case, cellulose acetate was dissolved in methyl acetate and mixed with isooctane at a mass ratio of 5:1. Methyl acetate was used as a co-solvent for cellulose acetate and isooctane, and is characterized by partial miscibility with water (24.5 % by mass) and high volatility (Bouchemal et al. 2004). It has been established earlier that this type organic mixture can be emulsified using an aqueous high-molecular-weight PVA solution as a stabilizing agent, presumably because this polymer can be adsorbed and tightly packed at the water-methyl acetate/cellulose interface (Freitas et al. 2005; Kristmundsdóttir and Ingvarsdóttir 1994; Lee et al. 1999). The initial emulsification was performed by high-shear mixing of the organic and water phases, which resulted in the formation of micrometer-sized droplets composed of an isooctane/cellulose acetate/methyl acetate (IO/CA/MeOAc) phase in water, presumably stabilized by PVA chains adsorbed at the interface between the phases (Figure 1a). As methyl acetate permeates into the water phase, likely during the emulsification process, the CA chains begin to regenerate and organize at the interface between water and isooctane. This process forms the initial structure of the isooctane-filled CA capsules and in turn isolates the isooctane phase in the formed droplets (Figure 1b). When all the methyl acetate has evaporated from the system, a capsule with a solid CA shell is obtained (Figure 1c). This is naturally a complex process containing several interconnected steps such as the emulsification, precipitation of CA in contact with water, adsorption of the PVA stabilizer at the organic-aqueous interface and subsequently at the hydrated CA surface, mixing of methyl acetate and water, and the evaporation of the volatile methyl acetate. In addition, these processes are occurring in a highly turbulent mixing field. The most crucial aspect of this process is likely the time required to reach the state in which the oil and polymer phases are fully separated. This likely also affects the isooctane encapsulation efficiency and the final properties of the capsules. A further complication is that the liquid core material, isooctane, is itself volatile and partly soluble in the aqueous phase (0.56 mg/L) (Reimer et al. 2017). As mentioned, the volatility of the co-solvent and its solubility in water governs the initial rate of the phase-separation between isooctane and CA and the organization of the regenerated CA at the surface of the droplet. However, this also affects the concomitant diffusion of the solvent from the interior of the droplet through the denser polymeric structure at its surface. The evaporation from the aqueous phase can however be tuned (Rosca et al. 2004) and a quick removal of methyl acetate might prevent the droplets from coalescing, but, simultaneously, does not necessarily ensure complete isooctane-polymer phase separation (Mendoza-Muñoz et al. 2016).

Schematic representation of the formation of capsules: (a) emulsion droplets composed of the IO/CA/MeOAc mixture in PVA aqueous solution, (b) phase separation of the isooctane and CA phases due to migration of the solvent molecules to the water phase and further evaporation from the system, (c) isooctane-filled CA capsules stabilized by PVA.

The emulsification of the IO/CA/MeOAc mixture in the water phase was achieved by Ultra Turrax mixing following two slightly different procedures. Capsules S1 were prepared by adding the organic mixture containing a highly concentrated solution of CA (6.7 wt%) into an aqueous solution of high-molecular-weight PVA, where the mass ratio between the organic and water phases was about 3:20. The emulsion was poured into continuously stirred water, where the evaporation of the co-solvent and simultaneous formation of capsules occurred. Capsules S2 were formed using a lower concentration of the CA solution (1.0 wt%) together with an increased mass ratio between the organic and water phases (3:10). Capsules S2 were then allowed to evaporate without any additional dilution.

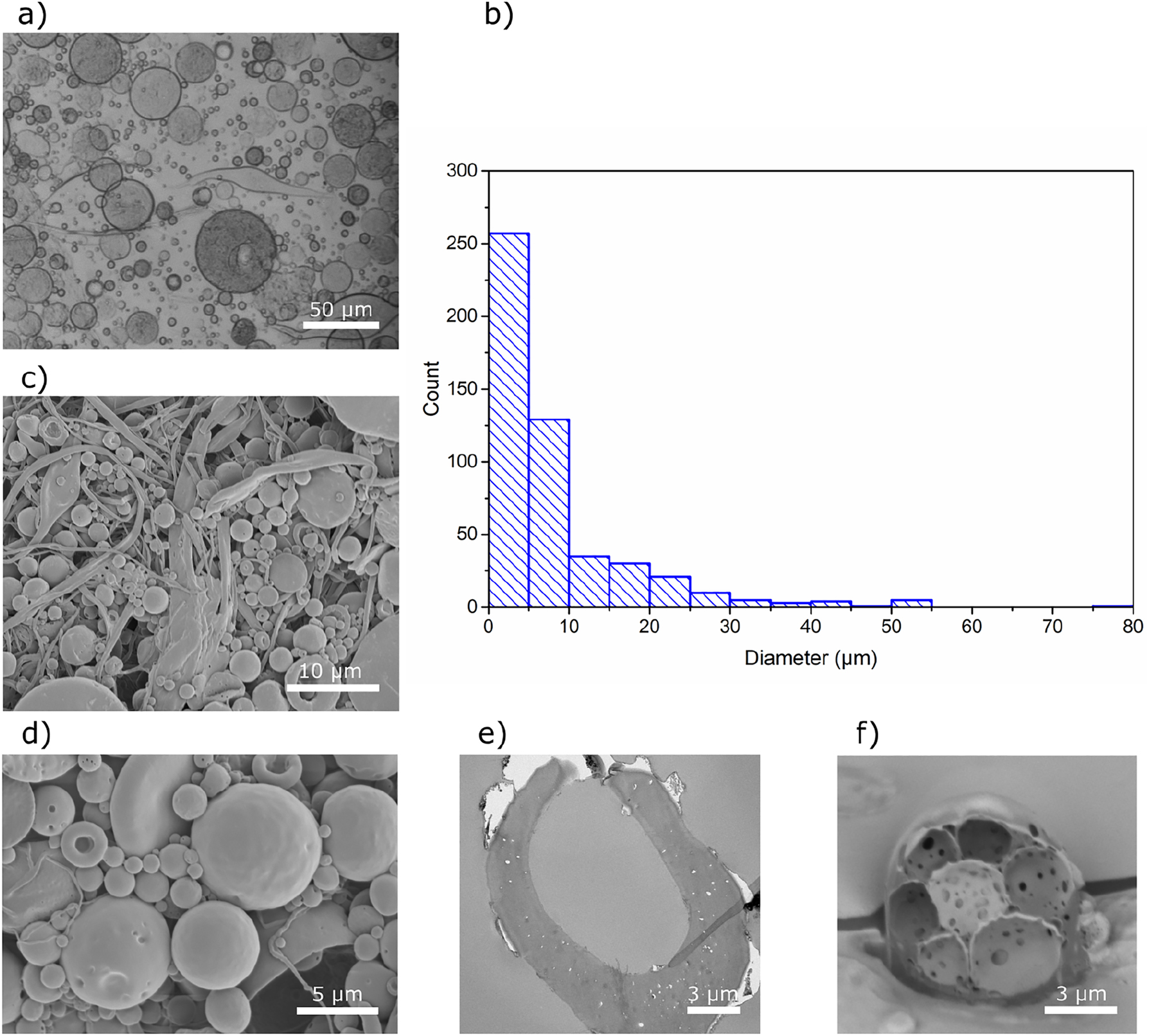

Capsules S1 were imaged in the wet state with an optical microscope. Figure 2a shows that the majority of the formulated capsules have a wet diameter below 10 µm, but larger capsules with diameters up to 80 µm are also present, in agreement with the size distribution profile (Figure 2b). As shown in Figure 2c, in addition to the spherical capsules, filamentous particles are also present, which upon drying entangle and create a fibrous network. This phenomenon has been previously reported and has been used for preparation of CA filaments suitable for textile applications (Law 2004; Sayyed et al. 2019). It is likely that a sudden removal of a large amount of methyl acetate from the organic phase facilitates precipitation of CA into fibrous aggregates (Freytag et al. 2000; Li et al. 2008). The dry capsules were imaged using SEM to investigate the morphology and structure of the capsules. The majority of the capsules maintain a spherical shape, but some were deformed under the vacuum of the SEM, suggesting that they indeed are hollow as isooctane could evaporate under these conditions (Figure 2d). The capsules are generally characterized by a smooth and uniform surface; however, some cracks in the polymer shells can be observed (Figure 2d). The structure of Capsules S1 was also studied by sectioning the dry capsules and imaging the cross-section using TEM. TEM images (Figure 2e) clearly show a core-shell structure of the CA capsules. In addition to TEM, the internal microstructure of the capsules was studied by FIB-SEM, where Figure 2f shows that some samples include not only uniform capsules, but also capsules with several internal compartments, suggesting that the encapsulated isooctane droplets likely did not have enough time to completely phase-separate from the polymer.

Characterization of Capsules S1. (a) Optical microscopy image of capsules in the wet state, (b) size distribution determined for wet capsules, (c, d) SEM images of the dry capsules captured at two different magnifications, (e) TEM micrograph and (f) FIB-SEM image of the cross-section of capsules.

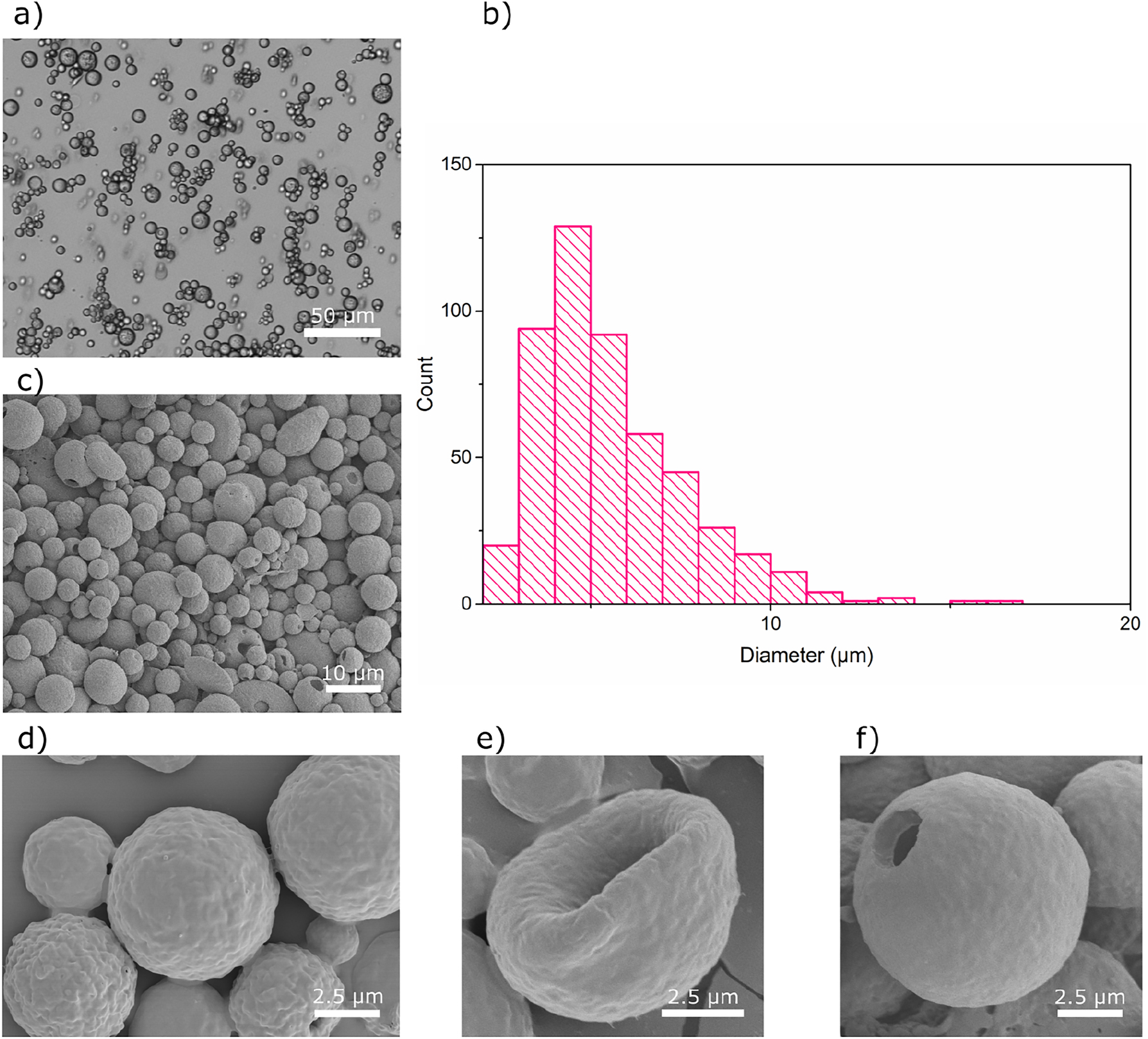

Capsules S2 were prepared following the second mixing procedure, using less CA in the organic phase, and resulted in the formulation of more homogeneous oil-in-water emulsion droplets; however, some double emulsion droplets were also present (Supplementary Figure S1). Upon solvent evaporation, the organic emulsion droplets developed into uniform CA capsules (Figure 3a) with a narrow size distribution. The size distribution profile (Figure 3b) and the SEM images show that the majority of the capsules have a wet diameter below 10 µm, and that the procedure effectively prevented the formation of filamentous particles (Figure 3c).

Characterization of Capsules S2. (a) Optical microscopy image of capsules in the wet state, (b) size distribution determined for wet capsules, (c, d) SEM images of the dry capsules captured at two different magnifications, (e, f) SEM images of two deformed capsules.

The formation of a relatively homogeneous dispersion is presumably related to the fact that the amount of methyl acetate present in the mixture is close to the saturation level in water (24.5 % by mass) (Bouchemal et al. 2004), and consequently the solvent evaporates slower, so that an equilibrium diameter of the emulsion droplets can be reached (Rosca et al. 2004). Furthermore, a decrease in the CA concentration results in a lower viscosity of the organic mixture, which likely makes it easier for the stirrer to shear the mixture to produce smaller droplets (Sanghvi and Nairn 1993). A slower removal of methyl acetate can also assist the IO/CA phase-separation and the formation of liquid-filled microcapsules. The SEM images show that only some capsules deformed in the high vacuum conditions (Figure 3e), while the majority kept a spherical shape or had holes on the surface (Figure 3f).

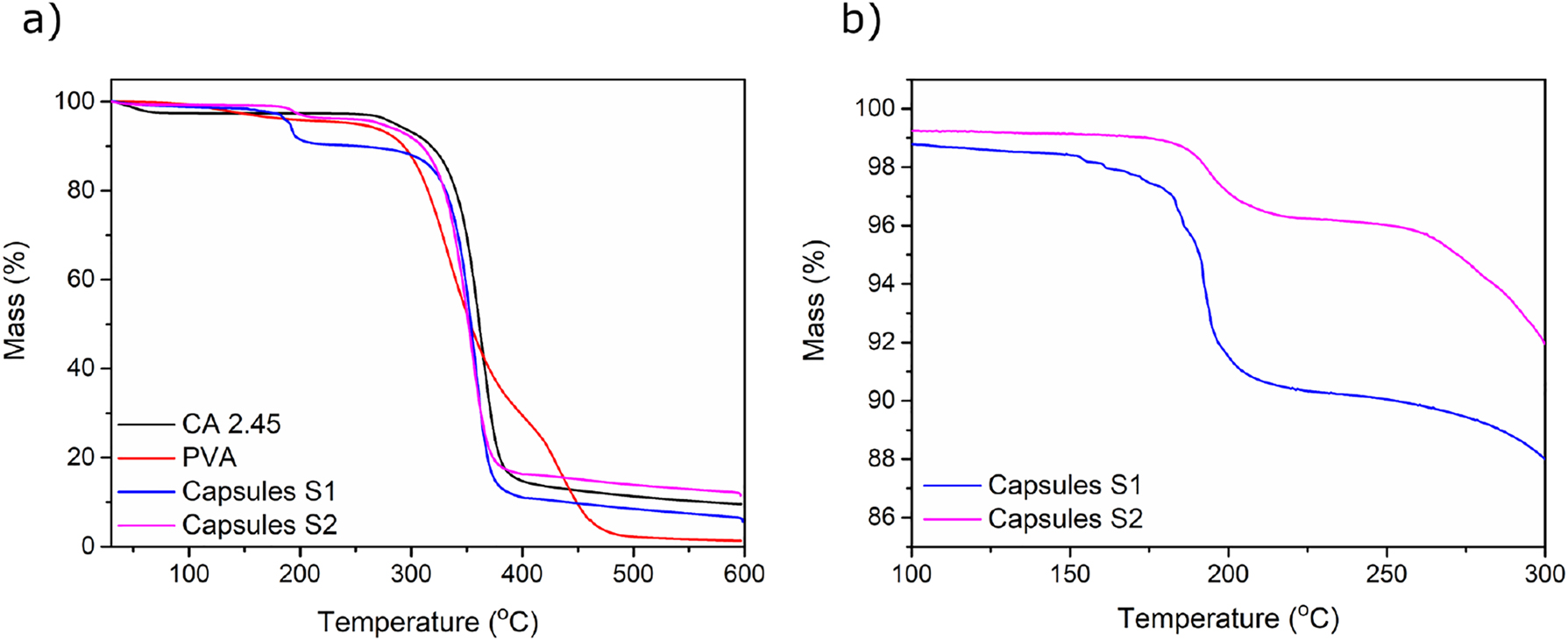

The efficiency of the oil encapsulation was quantitatively determined by thermogravimetric analysis (Figure 4). The experiments indicate that the concentration of isooctane was approximately 8 and 3 wt% for Capsules S1 and Capsules S2, respectively (Figure 4). Considering these values, and the fact that the initial concentration of isooctane was 16.7 % of the total solid mass, it can be concluded that after four days of drying, Capsules S1 contain about 50 % of the initial amount of isooctane, whereas Capsules S2 contain less than 20 %. These results show that the higher concentration of CA solution combined with a faster evaporation of methyl acetate improved the efficiency of isooctane encapsulation for Capsules S1. The use of the higher concentration of CA likely results in a better packing of the polymeric chains. A similar trend has also been reported in the literature for other types of capsules, and was explained by formation of a denser capsule wall composed of more entangled polymeric chains when a higher polymer concentration was used (Rosca et al. 2004). Even though the boiling temperature of isooctane is 99 °C (at 1 atm), the most significant mass change shown in Figure 4 occurred at a temperature close to 190 °C. This will be further elaborated upon in conjunction with the discussion about the expansion properties of the CA capsules upon heating. As presented in Figure 4a, the high-temperature part of the TGA curves of the capsules, for both procedures, follows the behavior of pure CA curve, which indicates that most of PVA was effectively removed during the washing of the capsules.

TGA curves of (a) CA capsules, PVA and CA in the temperature range of 25–600 °C, (b) CA capsules in the temperature range of 100–300 °C.

3.2 Heat-induced expansion of capsules prepared by high-shear mixing

The relatively simple modification of native cellulose by substituting hydroxyl groups to acetyl groups provides thermal softening and thus processability at temperatures beyond the glass transition temperature (T g ), without any significant degradation of the polymer. It has been shown that both thermal and mechanical properties of CA are governed by the degree of substitution, and that the T g decreases with an increase in DS values (e.g. from 2.33 to 2.48) (de Freitas et al. 2017; Teramoto 2015). In the present approach, the thermoplastic properties of CA (DS = 2.45) are utilized to prepare capsules with thermo-responsive properties. The expansion was tested by placing the capsules in a heating chamber with the heating rate set to 20 °C/min. The results show that when the temperature is increased, the dry Capsules S1 expand significantly in volume without any significant damage to the capsule wall. The expansion began at a temperature near 199 °C and the change in diameter reached a maximum factor of 3.8, which corresponds to a change in volume of approximately 57 times, compared to the initial volume at a temperature of 228 °C. Figure 5 shows the proposed, schematic mechanism of the expansion as well as images of one of the tested PVA-stabilized capsules. First, the isooctane-filled capsule is heated (Figure 5a), and when the temperature reaches the boiling point of isooctane (99 °C), the core of the capsule starts to evaporate, increasing the pressure inside the capsule (Figure 5b). This pressure naturally creates stress on the capsule wall, but not enough to expand the capsule since the CA is too stiff to yield. However, as the temperature is further increased and approaches the T g of CA, the capsule wall will soften sufficiently to allow expansion (Figure 5c). During the expansion, the softened CA presumably also allows isooctane to diffuse from the core of the capsule. This loss of isooctane can be seen in Figure 4, where a significant mass change occurs at the temperature close to T g of the CA, measured by the DSC to be 193 °C (Supplementary Figure S2), in agreement with literature (de Freitas et al. 2017; Puleo et al. 1989). Further experiments reveal that some, but relatively fewer, Capsules S2 also expand upon an increased temperature (Supplementary Figure S3) showing that despite more uniform capsule formation, isooctane encapsulation efficiency was hence not as good and the reasons to this need to be investigated further.

Expansion of Capsules S1 upon increased temperature. (a) Capsule at a temperature below the boiling point of isooctane, (b) evaporation of the liquid isooctane at temperatures beyond its boiling point, but significantly below the glass transition temperature of CA, (c) expanded capsule at a temperature close to the T g of CA in the capsule shell.

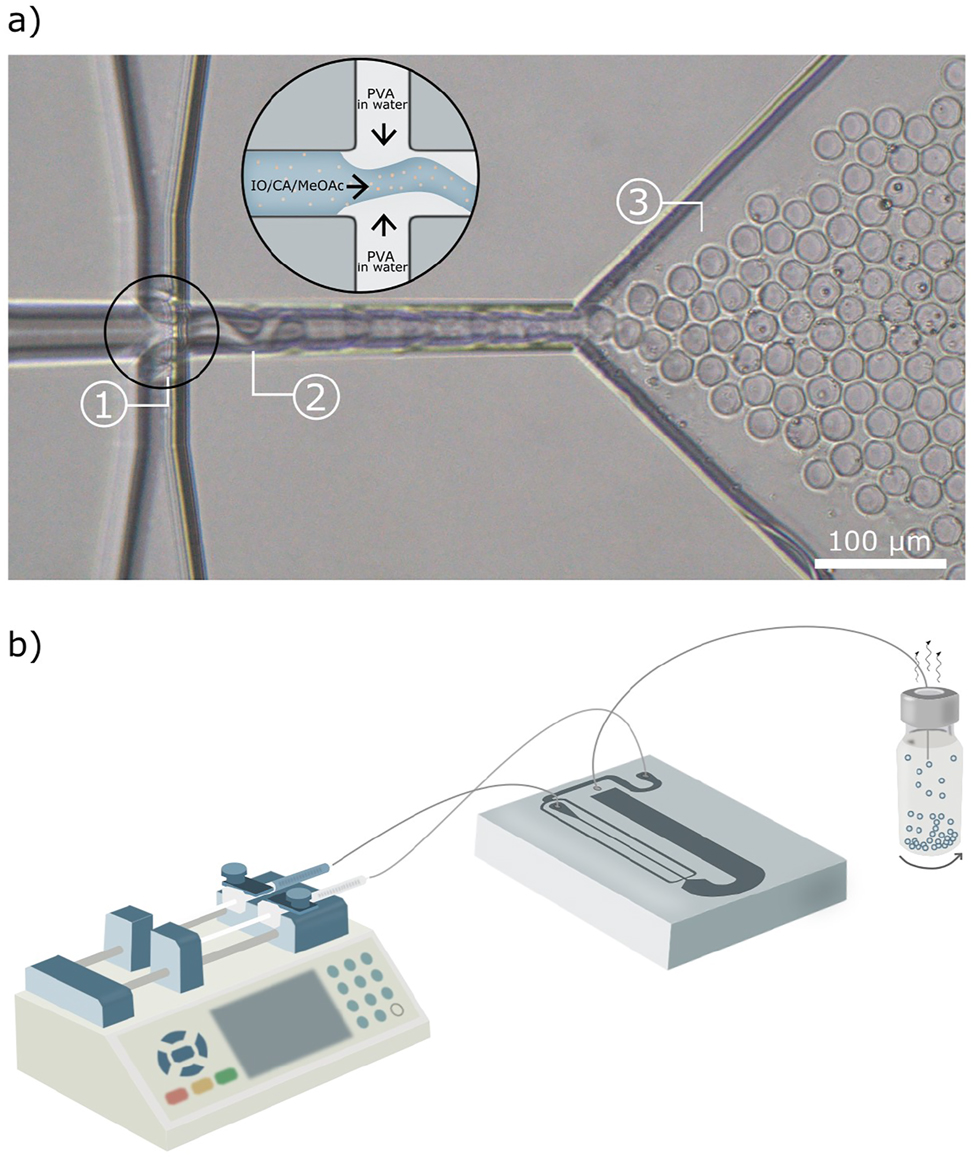

3.3 Emulsification by microfluidic flow-focusing

Microfluidics is one of the most effective techniques for controlled emulsification, and has been previously proposed for the production of microparticles from cellulose derivatives (Liu et al. 2017; Yeap et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2020). In the current case, the dispersed and continuous phases were composed of an IO/CA/MeOAc mixture and a low-molecular-weight PVA solution in Milli-Q water, respectively. The most suitable conditions for emulsification were adjusted by testing different concentrations of the continuous phase, as well as different flow rates of the continuous and dispersed phases. Interestingly and surprisingly, it was not possible to create stable, monodisperse droplets with the conditions used for the high-shear mixing. A thorough optimization procedure showed that emulsification was only possible when the concentration and the flow rate of the dispersed phase were significantly higher than the continuous phase. It was, as an example, possible to form stable and monodisperse droplets when the dispersed mixture (central flow) was used at a concentration of 1.2 wt% at a flow rate of 0.67 μL/min, and the continuous phase (side channels) had a concentration of 0.008 wt% (PVA) at a flow rate of 0.067 μL/min (Figure 5a). Based on these experiments, the stable and continuous production of monodisperse emulsion droplets with the average diameter of about 23 µm could be obtained when the PVA concentration was between 0.008 and 0.05 wt% (Figure 5b). This flexibility of the parameters is presumably related to the fact that in this range of PVA concentrations the difference in viscosities and interfacial tensions characteristic for the system is negligible (Table 1). Application of higher flow rates and higher concentrations of the PVA phase (e.g. 1 wt%) caused formation of films in the outlet channel and chaotic formation of a highly polydisperse emulsion. When the organic phase meets the water phase in the junction, the methyl acetate diffuses from the organic phase and mixes with the water phase, and in this new methyl acetate/water mixture, the solubility of PVA is hypothesized to decrease.

Properties of the dispersed (central flow) and continuous phases (side channels) of the microfluidic system.

| PVA in water (0.008 wt%) | PVA in water (0.05 wt%) | IO/CA in MeOAc (0.2 wt% IO, 1 wt% CA) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinematic viscosity (mm2/s) | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 |

| PVA 0.008 wt% – IO/CA/MeOAc | PVA 0.05 wt% – IO/CA/MeOAc | – | |

| Interfacial tension (mN/m) | 1.37 ± 0.01 | 1.39 ± 0.01 | – |

Figure 6a presents an optical microscopy image of the flow-focusing junction during the emulsification process. Partial miscibility of methyl acetate with water is observed by the presence of two menisci in the junction (Figure 6a, Location 1). It can be seen that the cone of the organic phase and the formulated droplets do not flow in the center of the outlet, instead they exhibit tendency to wet the walls of the channel (Figure 6a, Location 2). However, the emulsification results in a continuous generation of highly monodisperse and non-aggregating droplets (Figure 6a, Location 3), which is also demonstrated in a movie provided in the Supplementary Material.

Design of the microfluidic device. (a) Optical microscopy image of the flow-focusing junction during emulsification. The black circle includes a schematic illustration of the mixing in the junction. (b) Schematic illustration of the microfluidic setup that facilitates controlled emulsification. The blue color together with the small beige dots in the enlarged junction illustrate the organic mixture composed of CA solution and isooctane, whereas the grey color illustrates an aqueous PVA solution.

A strategy based on partial miscibility of the phases, extremely low concentration of the stabilizer, and a flow rate of the continuous phase being 10 times lower than the flow rate of the organic inner phase has not been demonstrated earlier, at least to the knowledge of the authors. Typically, it is more favorable to have the continuous liquid phase wet the outlet channel walls. Furthermore, the continuous phase usually contains a highly concentrated stabilizer solution that can alter the interfacial tension between the two immiscible or partially miscible phases, but this is obviously not the case for the present system (Baret 2012; Christopher and Anna 2007; Du et al. 2020; Ho et al. 2021). Therefore, a further investigation of the current system was crucial to better understand the mechanism of emulsification in the flow-focusing junction and the subsequent formation of capsules. For this purpose, the organic and water phases were stained with oil red and methylene blue, respectively, and the process of mixing was observed under an optical microscope. The results presented in Supplementary Figure S4, show that this combination of parameters leads to the formation of water-in-oil emulsion composed of aqueous PVA droplets dispersed in the organic mixture and presumably stabilized by CA.

The emulsion droplets formed in the flow-focusing device were transformed to an open glass vial containing an intensively stirred solution of an additional stabilizer (Figure 6b). The stirring caused shaking of the outlet tubing of microfluidics, which most likely facilitated formation of non-aggregated microsized capsules. Two different types of the stabilizers were used for these experiments: an aqueous solution of high-molecular-weight PVA and an aqueous dispersion of CNCs.

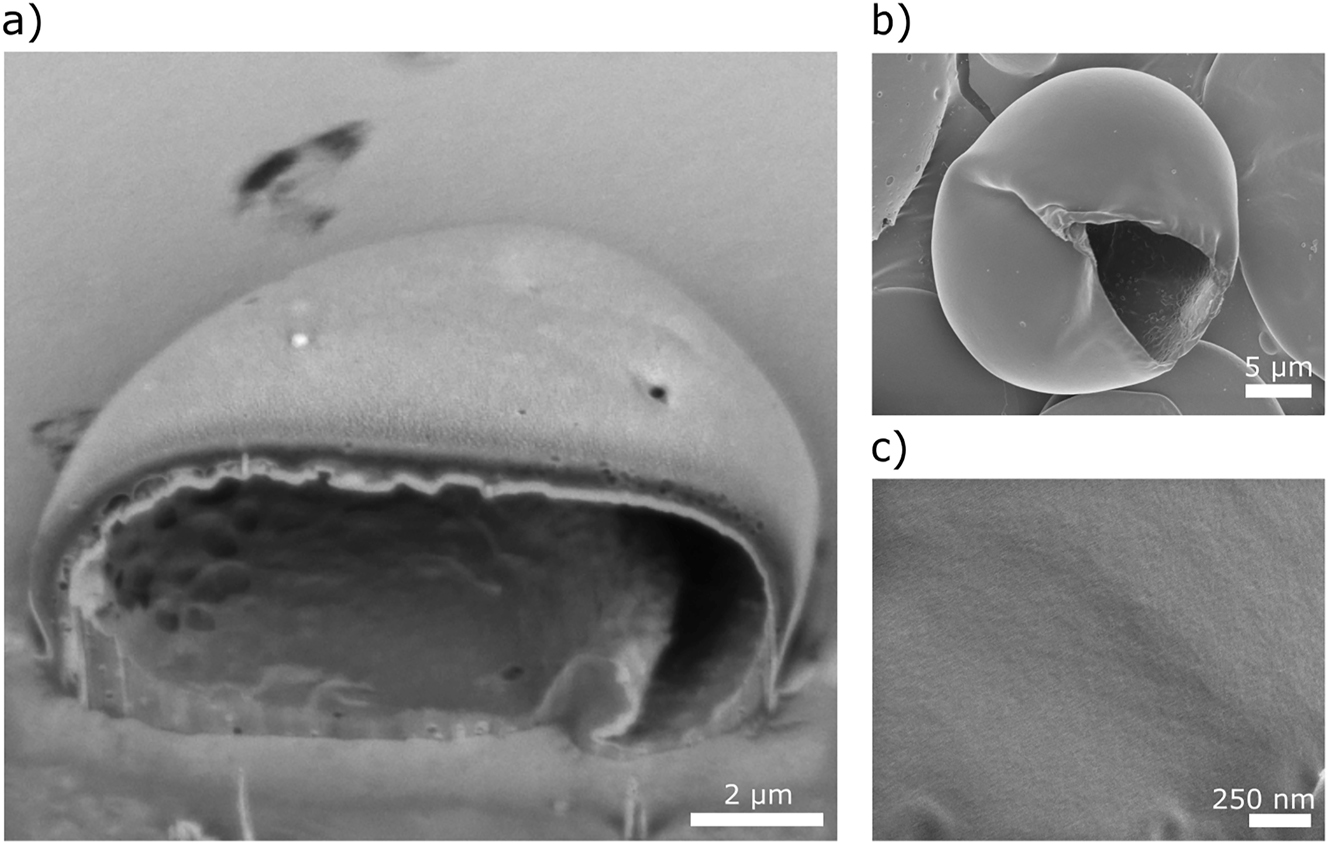

The PVA-stabilized microcapsules have smooth and homogeneous shells (Figure 7), suggesting gradual evaporation of methyl acetate without any apparent disruption of the polymer film on the surface. Most of the capsules burst on the edge in the high-vacuum conditions used for SEM analysis and hence collapsed into disk-like structures. A capsule cross-section is shown in Figure 7a, cut and imaged by using FIB-SEM. Some capsules ruptured under vacuum, which supports that they are indeed thin-walled (Figure 7b).

Micrographs of PVA-stabilized microcapsules formed using microfluidics. (a) FIB-SEM and (b) SEM images of the capsules. (c) High-magnification image of the surface of the capsule wall.

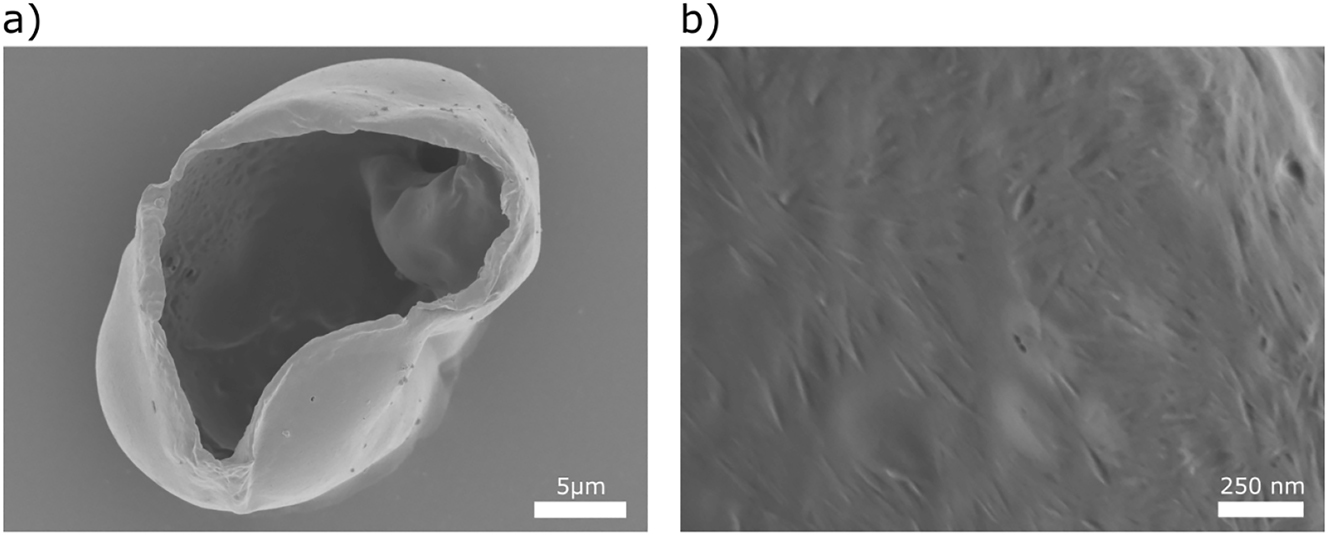

CNCs are bio-sourced nanoparticles with highly ordered structure, tunable surface chemistry, excellent mechanical properties, and good thermal and chemical stability (Habibi et al. 2010; Mystek et al. 2020). They have also been used as stabilizers for different types of emulsions (Capron et al. 2017; Gestranius et al. 2017). In this study, an aqueous CNCs dispersion was utilized to improve the stability and inhibit the aggregation of CA capsules. The SEM images in Figure 8a show a ruptured CNC-stabilized CA capsule. The morphology of the capsule wall and the organization of the individual rod-like CNCs along the surface can be seen in Figure 8b. Such modification of capsules governs changes in the surface morphology and surface chemistry, and gives access to controlled functionalization of capsules that leads to a broader range of applications.

Micrographs of CNC-stabilized microcapsules formed using microfluidics. (a) SEM image of capsule. (b) High-magnification image of the surface of the capsule.

This work shows that it is possible to form CA capsules with targeted structure and morphology by using microfluidics, but it is beyond the scope of this work to study how to further improve the long-term stability of the capsules. Images of the synthetized capsules, as well as their size distribution presented in Supplementary Figure S5, show that the optimization of the stabilizing conditions is necessary in order to prevent coalescence of the solvent-swollen droplets before stable and solvent-free microcapsules are obtained. Based on the increased size of the capsules, it is expected that fusion between several smaller droplets occurred. This type of a physical instability has also been reported for particles made from other cellulose derivatives (e.g. ethyl cellulose) (Desgouilles et al. 2003).

4 Conclusions

The results of the current work demonstrate that it is indeed possible to prepare micrometer-sized, liquid-filled capsules made from CA via emulsification and solvent evaporation using two methods: bulk high-shear mixing and microfluidic flow-focusing. The emulsion droplets and ultimately the CA capsules formed with these methods were carefully characterized to establish the formation mechanism and to determine the properties of the capsules. The results show that each of the methods yields different properties of the final capsules. The bulk emulsification resulted in two types of oil-in-water emulsions, depending on the applied procedure. A high concentration of CA combined with a fast evaporation of the organic solvent led to formation of a heterogeneous dispersion of single core capsules, capsules with several liquid compartments and fibrous aggregates. TGA measurements showed that at least 50 % of the initial amount of isooctane could be effectively encapsulated within these capsules. The dry capsules were found to expand when heated close to or beyond the T g of the CA polymeric shell to a maximum expansion of 57 times the original volume, demonstrating their potential use in the preparation of lightweight materials or for controlled release applications. More homogeneous CA capsules were formed when the concentration of the CA solution was decreased and the evaporation of the solvent was slower. However, the so prepared dry capsules were characterized by a lower efficiency of isooctane encapsulation (<20 %). The application of microfluidics provided a precise control of the emulsification process with similar components as used in the bulk emulsification. However, following an optimization procedure, it was found that the composition of the phases and the flow rates were significantly different from commonly reported for similar oil/water systems. A better understanding of the type of emulsion formed in the microfluidic system was achieved after staining of the organic and water phases. These experiments revealed that uniform water-in-oil emulsions were formed using microfluidics, which consequently resulted in the formation of water-filled CA capsules. Both polymers and solid particles such as CNCs can be used as stabilizing agents in the capsule formation process, however, the initially formed capsules did not display perfect long-term stability, showing a future need for further optimization of the stabilizing conditions to prevent capsule coalescence.

Funding source: Svenska Forskningsrådet Formas

Award Identifier / Grant number: 942-2016-12

Acknowledgments

Dr. Naga Venkata Gayathri Vegesna, Umeå Core Facility for Electron Microscopy (UCEM) and National Microscopy Infrastructure, NMI (VR-RFI 2016-00968) are acknowledged for providing the TEM images.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Katarzyna Mystek: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, validation, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Bo Andreasson: conceptualization, methodology, investigation. Michael S. Reid: methodology, investigation, writing – review and editing. Hugo Françon: visualization, investigation. Cecilia Fager: methodology, investigation. Per A. Larsson: conceptualization, investigation, supervision, funding acquisition, writing – review and editing. Anna J. Svagan: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, supervision, writing – review and editing. Lars Wågberg: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, writing – review and editing.

-

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Research funding: Formas Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agriculture and Spacial Planning (942-2016-12) and Nouryon AB are gratefully acknowledged for funding.

-

Data availability: Data will be made available on request.

References

Abitbol, T., Kloser, E., and Gray, D.G. (2013). Estimation of the surface sulfur content of cellulose nanocrystals prepared by sulfuric acid hydrolysis. Cellulose 20: 785–794, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-013-9871-0.Search in Google Scholar

Andreasson, B., Wijtmans, R., Larsson Kron, A., From, M., López Cabezas, A., Ruda, M., and Martirez, P. (2020). Thermally expandable cellulose-based microspheres. WO2020099440A1.Search in Google Scholar

Baret, J.C. (2012). Surfactants in droplet-based microfluidics. Lab Chip 12: 422–433, https://doi.org/10.1039/c1lc20582j.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Bouchemal, K., Briançon, S., Perrier, E., and Fessi, H. (2004). Nano-emulsion formulation using spontaneous emulsification: solvent, oil and surfactant optimisation. Int. J. Pharm. 280: 241–251, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.05.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Capron, I., Rojas, O.J., and Bordes, R. (2017). Behavior of nanocelluloses at interfaces. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 29: 83–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cocis.2017.04.001.Search in Google Scholar

Carvalho, J.P.F., Silva, A.C.Q., Silvestre, A.J.D., Freire, C.S.R., and Vilela, C. (2021). Spherical cellulose micro and nanoparticles: a review of recent developments and applications. Nanomaterials 11: 2744, https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11102744.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Christopher, G.F. and Anna, S.L. (2007). Microfluidic methods for generating continuous droplet streams. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 40: R319–R336, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/40/19/R01.Search in Google Scholar

de Freitas, R.R.M., Senna, A.M., and Botaro, V.R. (2017). Influence of degree of substitution on thermal dynamic mechanical and physicochemical properties of cellulose acetate. Ind. Crop. Prod. 109: 452–458, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.08.062.Search in Google Scholar

Desgouilles, S., Vauthier, C., Bazile, D., Vacus, J., Grossiord, J.L., Veillard, M., and Couvreur, P. (2003). The design of nanoparticles obtained by solvent evaporation: a comprehensive study. Langmuir 19: 9504–9510, https://doi.org/10.1021/la034999q.Search in Google Scholar

Döge, N., Hönzke, S., Schumacher, F., Balzus, B., Colombo, M., Hadam, S., Rancan, F., Blume-Peytavi, U., Schäfer-Korting, M., Schindler, A., et al.. (2016). Ethyl cellulose nanocarriers and nanocrystals differentially deliver dexamethasone into intact, tape-stripped or sodium lauryl sulfate-exposed ex vivo human skin – assessment by intradermal microdialysis and extraction from the different skin layers. J. Contr. Release 242: 25–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.07.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Du, J., Ibaseta, N., and Guichardon, P. (2020). Generation of an O/W emulsion in a flow-focusing microchip: importance of wetting conditions and of dynamic interfacial tension. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 159: 615–627, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2020.04.012.Search in Google Scholar

Edgar, K.J., Buchanan, C.M., Debenham, J.S., Rundquist, P.A., Seiler, B.D., Shelton, M.C., and Tindall, D. (2001). Advances in cellulose ester performance and application. Prog. Polym. Sci. (Oxf.) 26: 1605–1688, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6700(01)00027-2.Search in Google Scholar

Fager, C., Röding, M., Olsson, A., Lorén, N., Von Corswant, C., Särkkä, A., and Olsson, E. (2020). Optimization of FIB-SEM tomography and reconstruction for soft, porous, and poorly conducting materials. Microsc. Microanal. 26: 837–845, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1431927620001592.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Freitas, S., Merkle, H.P., and Gander, B. (2005). Microencapsulation by solvent extraction/evaporation: reviewing the state of the art of microsphere preparation process technology. J. Contr. Release 102: 313–332, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Freytag, T., Dashevsky, A., Tillman, L., Hardee, G.E., and Bodmeier, R. (2000). Improvement of the encapsulation efficiency of oligonucleotide-containing biodegradable microspheres. J. Contr. Release 69: 197–207, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-3659(00)00299-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Gericke, M., Trygg, J., and Fardim, P. (2013). Functional cellulose beads: preparation, characterization, and applications. Chem. Rev. 113: 4812–4836, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr300242j.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Gestranius, M., Stenius, P., Kontturi, E., Sjöblom, J., and Tammelin, T. (2017). Phase behaviour and droplet size of oil-in-water pickering emulsions stabilised with plant-derived nanocellulosic materials. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 519: 60–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.04.025.Search in Google Scholar

Giannuzzi, L.A. and Stevie, F.A. (2005). Introduction to focused ion beams: instrumentation, theory, techniques and practice. In: Introduction to focused ion beams: instrumentation, theory, techniques and practice. Springer, New York, NY, USA.10.1007/b101190Search in Google Scholar

Habibi, Y., Lucia, L.A., and Rojas, O.J. (2010). Cellulose nanocrystals: chemistry, self-assembly, and applications. Chem. Rev. 110: 3479–3500, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr900339w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ho, T.M., Razzaghi, A., Ramachandran, A., and Mikkonen, K.S. (2021). Emulsion characterization via microfluidic devices: a review on interfacial tension and stability to coalescence. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 299: 102541, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2021.102541.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Huang, H. and Dean, D. (2020). 3-D printed porous cellulose acetate tissue scaffolds for additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 31: 100927, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.100927.Search in Google Scholar

Joshy, K.S., Snigdha, S., George, A., Kalarikkal, N., Pothen, L.A., and Thomas, S. (2017). Core–shell nanoparticles of carboxy methyl cellulose and compritol-PEG for antiretroviral drug delivery. Cellulose 24: 4759–4771, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1446-z.Search in Google Scholar

Khoshnevisan, K., Maleki, H., Samadian, H., Shahsavari, S., Sarrafzadeh, M.H., Larijani, B., Dorkoosh, F.A., Haghpanah, V., and Khorramizadeh, M.R. (2018). Cellulose acetate electrospun nanofibers for drug delivery systems: applications and recent advances. Carbohydr. Polym. 198: 131–141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.072.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kristmundsdóttir, T. and Ingvarsdóttir, K. (1994). Influence of emulsifying agents on the properties of cellulose acetate butyrate and ethylcellulose microcapsules. J. Microencapsul. 11: 633–639, https://doi.org/10.3109/02652049409051113.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Law, R.C. (2004). Cellulose acetate in textile application. In: Macromolecular symposia, Vol. 208. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, New York, NY, USA, pp. 255–266.10.1002/masy.200450410Search in Google Scholar

Lee, S.C., Oh, J.T., Jang, M.H., and Chung, S.I. (1999). Quantitative analysis of polyvinyl alcohol on the surface of poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles prepared by solvent evaporation method: effect of particle size and PVA concentration. J. Contr. Release 59: 123–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-3659(98)00185-0.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, J., Lee, J., Jeon, H., Park, H., Oh, S., and Chung, I. (2020). Studies on the melt viscosity and physico-chemical properties of cellulose acetate propionate composites with lactic acid blends. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 707: 8–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/15421406.2020.1741814.Search in Google Scholar

Li, M., Rouaud, O., and Poncelet, D. (2008). Microencapsulation by solvent evaporation: state of the art for process engineering approaches. Int. J. Pharm. 363: 26–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.07.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Liu, Y., Nambu, N.O., and Taya, M. (2017). Cell-laden microgel prepared using a biocompatible aqueous two-phase strategy. Biomed. Microdevices 19: 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10544-017-0198-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Liu, Y., Li, Y., Hensel, A., Brandner, J.J., Zhang, K., Du, X., and Yang, Y. (2020). A review on emulsification via microfluidic processes. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 14: 350–364, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11705-019-1894-0.Search in Google Scholar

Mao, D., Li, Q., Bai, N., Dong, H., and Li, D. (2018). Porous stable poly(lactic acid)/ethyl cellulose/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds prepared by a combined method for bone regeneration. Carbohydr. Polym. 180: 104–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.10.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mendoza-Muñoz, N., Alcalá-Alcalá, S., and Quintanar-Guerrero, D. (2016). Preparation of polymer nanoparticles by the emulsification-solvent evaporation method: from Vanderhoff’s Pioneer approach to recent adaptations. In: Polymer nanoparticles for nanomedicines. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, pp. 87–121.10.1007/978-3-319-41421-8_4Search in Google Scholar

Murtinho, D., Lagoa, A.R., Garcia, F.A.P., and Gil, M.H. (1998). Cellulose derivatives membranes as supports for immobilisation of enzymes. Cellulose 5: 299–308, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009255126274.10.1023/A:1009255126274Search in Google Scholar

Mystek, K., Reid, M.S., Larsson, P.A., and Wågberg, L. (2020). In situ modification of regenerated cellulose beads: creating all-cellulose composites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59: 2968–2976, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.9b06273.Search in Google Scholar

Puleo, A.C., Paul, D.R., and Kelley, S.S. (1989). The effect of degree of acetylation on gas sorption and transport behavior in cellulose acetate. J. Membr. Sci. 47: 301–332, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-7388(00)83083-5.Search in Google Scholar

Reimer, A., Wedde, S., Staudt, S., Schmidt, S., Höffer, D., Hummel, W., Kragl, U., Bornscheuer, U.T., and Gröger, H. (2017). Process development through solvent engineering in the biocatalytic synthesis of the heterocyclic bulk chemical ε-caprolactone. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 54: 391–396, https://doi.org/10.1002/jhet.2595.Search in Google Scholar

Rosca, I.D., Watari, F., and Uo, M. (2004). Microparticle formation and its mechanism in single and double emulsion solvent evaporation. J. Contr. Release 99: 271–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.07.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Samios, E., Dart, R.K., and Dawkins, J.V. (1997). Preparation, characterization and biodegradation studies on cellulose acetates with varying degrees of substitution. Polymer 38: 3045–3054, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861(96)00868-3.Search in Google Scholar

Sanghvi, S.P. and Nairn, J.G. (1993). A method to control particle size of cellulose acetate trimellitate microspheres. J. Microencapsul. 10: 181–194, https://doi.org/10.3109/02652049309104384.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Sayyed, A.J., Deshmukh, N.A., and Pinjari, D.V. (2019). A critical review of manufacturing processes used in regenerated cellulosic fibres: viscose, cellulose acetate, cuprammonium, LiCl/DMAc, ionic liquids, and NMMO based lyocell. Cellulose 26: 2913–2940, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-019-02318-y.Search in Google Scholar

Soppimath, K.S., Kulkarni, A.R., Aminabhavi, T.M., and Bhaskar, C. (2001). Cellulose acetate microspheres prepared by o/w emulsification and solvent evaporation method. J. Microencapsul. 18: 811–817, https://doi.org/10.1080/02652040110065486.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Staff, R.H., Landfester, K., and Crespy, D. (2013). Recent advances in the emulsion solvent evaporation technique for the preparation of nanoparticles and nanocapsules. Adv. Polym. Sci. 262: 329–344, https://doi.org/10.1007/12_2013_233.Search in Google Scholar

Su, X., Yang, Z., Tan, K.B., Chen, J., Huang, J., and Li, Q. (2020). Preparation and characterization of ethyl cellulose film modified with capsaicin. Carbohydr. Polym. 241: 116259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116259.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Tan, H.L., Kai, D., Pasbakhsh, P., Teow, S.Y., Lim, Y.Y., and Pushpamalar, J. (2020). Electrospun cellulose acetate butyrate/polyethylene glycol (CAB/PEG) composite nanofibers: a potential scaffold for tissue engineering. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 188: 110713, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110713.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Teramoto, Y. (2015). Functional thermoplastic materials from derivatives of cellulose and related structural polysaccharides. Molecules 20: 5487–5527, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules20045487.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Tirado, D.F., Palazzo, I., Scognamiglio, M., Calvo, L., Della Porta, G., and Reverchon, E. (2019). Astaxanthin encapsulation in ethyl cellulose carriers by continuous supercritical emulsions extraction: a study on particle size, encapsulation efficiency, release profile and antioxidant activity. J. Supercrit. Fluids 150: 128–136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2019.04.017.Search in Google Scholar

Topel, S.D., Balcioglu, S., Ateş, B., Asilturk, M., Topel, Ö., and Ericson, M.B. (2021). Cellulose acetate encapsulated upconversion nanoparticles – a novel theranostic platform. Mater. Today Commun. 26: 101829, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101829.Search in Google Scholar

Vidal-Romero, G., Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L., Martínez-Acevedo, L., Leyva-Gómez, G., Mendoza-Elvira, S.E., and Quintanar-Guerrero, D. (2019). Design and evaluation of pH-dependent nanosystems based on cellulose acetate phthalate, nanoparticles loaded with chlorhexidine for periodontal treatment. Pharmaceutics 11: 604, https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics11110604.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Volmajer Valh, J., Vajnhandl, S., Škodič, L., Lobnik, A., Turel, M., and Vončina, B. (2017). Effects of ultrasound irradiation on the preparation of ethyl cellulose nanocapsules containing spirooxazine dye. J. Nanomater. 2017: 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4864760.Search in Google Scholar

Wohlert, M., Benselfelt, T., Wågberg, L., Furó, I., Berglund, L.A., and Wohlert, J. (2021). Cellulose and the role of hydrogen bonds: not in charge of everything. Cellulose 29: 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-021-04325-4.Search in Google Scholar

Yeap, E.W.Q., Acevedo, A.J., and Khan, S.A. (2019). Microfluidic extractive crystallization for spherical drug/drug-excipient microparticle production. Org. Process Res. Dev. 23: 375–381, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00432.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, M., Guo, W., Ren, M., and Ren, X. (2020). Fabrication of porous cellulose microspheres with controllable structures by microfluidic and flash freezing method. Mater. Lett. 262: 127193, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2019.127193.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, C.X. (2013). Multiphase flow microfluidics for the production of single or multiple emulsions for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 65: 1420–1446, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2013.05.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Zhao, X.F. and Winter, W.T. (2015). Cellulose/cellulose-based nanospheres: perspectives and prospective. Ind. Biotechnol. 11: 34–43, https://doi.org/10.1089/ind.2014.0030.Search in Google Scholar

Zhou, X., Lin, X., White, K.L., Lin, S., Wu, H., Cao, S., Huang, L., and Chen, L. (2016). Effect of the degree of substitution on the hydrophobicity of acetylated cellulose for production of liquid marbles. Cellulose 23: 811–821, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-015-0856-z.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/npprj-2023-0051).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Biorefining

- Effects of trace elements (Fe, Cu, Ni, Co and Mg) on biomethane production from paper mill wastewater

- Paper Technology

- Water-dispersible paper for packaging applications – balancing material strength and dispersibility

- Recyclable oil resistant paper with enhanced water resistance based on alkyl ketene dimer modified sodium alginate

- Coating

- Preparation and properties of a novel decorative base paper for formaldehyde-free adhesive impregnation

- The effect of carbon nanoparticles on cellulosic handsheets

- Environmental Impact

- Effects of programmed maintenance shutdowns on effluent quality of a bleached kraft pulp mill

- Carbon emissions analysis of the pulp molding industry: a comparison of dry-press and wet-press production processes

- Nanotechnology

- Effect of cellulose nanofibril concentration and diameter on the quality of bicomponent yarns

- The preparation of cellulose acetate capsules using emulsification techniques: high-shear bulk mixing and microfluidics

- Lignin

- Great potentials of lignin-based separator for Li-ion battery with electrospinning in aqueous system

- Using guaiacol as a capping agent in the hydrothermal depolymerisation of kraft lignin

- Preparation of flexible and binder-free lignin-based carbon nanofiber electrode materials by electrospinning in aqueous system

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Biorefining

- Effects of trace elements (Fe, Cu, Ni, Co and Mg) on biomethane production from paper mill wastewater

- Paper Technology

- Water-dispersible paper for packaging applications – balancing material strength and dispersibility

- Recyclable oil resistant paper with enhanced water resistance based on alkyl ketene dimer modified sodium alginate

- Coating

- Preparation and properties of a novel decorative base paper for formaldehyde-free adhesive impregnation

- The effect of carbon nanoparticles on cellulosic handsheets

- Environmental Impact

- Effects of programmed maintenance shutdowns on effluent quality of a bleached kraft pulp mill

- Carbon emissions analysis of the pulp molding industry: a comparison of dry-press and wet-press production processes

- Nanotechnology

- Effect of cellulose nanofibril concentration and diameter on the quality of bicomponent yarns

- The preparation of cellulose acetate capsules using emulsification techniques: high-shear bulk mixing and microfluidics

- Lignin

- Great potentials of lignin-based separator for Li-ion battery with electrospinning in aqueous system

- Using guaiacol as a capping agent in the hydrothermal depolymerisation of kraft lignin

- Preparation of flexible and binder-free lignin-based carbon nanofiber electrode materials by electrospinning in aqueous system