Abstract

Europe is acting to fight noise pollution. The Environmental Noise Directive (2002/49/EC) requires EU Member States to determine the exposure to environmental noise through strategic noise mapping, and elaborate action plans to reduce noise pollution. Road traffic noise is a common environmental noise source; henceforth, EU countries are obliged to produce strategic noise maps for all major roads, railways, airports, and agglomerations, on a 5-year basis. These noise maps are used by national competent authorities to identify priorities for action planning and by the European Commission to globally assess noise exposure across the EU. A thorough investigation is conducted in this article to assess how different road surface types affect road traffic noise levels in selected EU member states which are incorporating CNOSSOS-EU into their national law. It has been done by comparing the nationally published noise data to those published by CNOSSOS-EU in 2021 for various vehicle categories by obtaining the rolling and propulsion noise for each road surface type while ignoring other factors. The aim of this study is to address the deficiency in the assessment and show a comparison between the noise generated from different surface types which can potentially enhance the effectiveness of strategic noise mapping.

1 Introduction

In today’s world, noise can pose a serious problem in many fields for society. One major source of environmental noise in urban areas in Europe is road traffic noise [1], which is not only considered loud but is also a persistent nuisance problem affecting a wide range of aspects of life [2]. Road traffic noise is considered the second most disturbing environmental noise source [1,3,4] affecting the daily life activities and mental health of individuals residing in noisy urban environments and negatively influences their well-being [5,6,7]. After the pollution of fine particles, road traffic noise is considered the most common environmental risk factor to our health in Europe [8]. Its adverse health effects include various detrimental consequences on both a mental and a physical level, which are usually caused by the nuisance of loud engine sounds, tire-road interaction which increases with the vehicle’s speed, and vehicle horns, leading to a weary body and mind, evoking sometimes unpleasant emotions [9]. Furthermore, this can be allied with long-term risks of cardiovascular illnesses [10,11,12], such as heart attacks or hypertension [13,14]. To a further extent, work and educational environments are affected too, and overall cognition, communication, and attention can all be weakened due to excessive prolonged noise [15,16,17]. On the other hand, the overall burden of road traffic noise in the European Union, including direct expenses and impacts like medical treatments and lost productivity, is estimated to be 40 billion euros each year [18]. Thus, some real active measures countering these adverse effects are desirable to reduce road traffic noise pollution.

To address the problem and its scale thoroughly, the Environmental Noise Directive 2002/49/E (END) was implemented in 2002 by the European Union as a common measure of environmental noise assessment [19]. Each member state is obligated to carry out a systematic evaluation in the form of dose–effect relations [20] of sound power levels in heavily inhabited locations, near transit centers, and alongside key through fares in order to harmonize the parameters of noise evaluation by creating strategic noise maps from traffic noise data collection [19,21]. Important insights can be obtained that aid the authorities in ranking locations of intervention and assessing the extent of the problem. The EU aims to produce calmer and more comfortable living conditions for member states’ residents utilizing the END. In 2019, The European Commission introduced “The European Green Deal” with the aim of protecting the well-being and health of citizens from environmental risks [22]. At the core of that, a Zero Pollution Action Plan was launched in 2021 with the ambition to reduce environmental pollution by 2030. One of its key targets is to reduce the number of people chronically affected by transport noise, including road traffic noise, by 30% compared to 2017, while striving to achieve zero pollution by 2050 [23,24]. The Commission’s aim is to tackle noise at its source, by ensuring effective on-site execution of roads and enhancing the EU noise-related regulatory framework for tyres and road vehicles, where appropriate [23]. Therefore, members are encouraged to coordinate strategies for mitigating noise pollution while ensuring public health and safety by endorsing quieter means of transport, such as electric vehicles (EVs), reducing road speed limits, promoting the use of quiet tyres, applying low-noise pavements on road surfaces [25], constructing durable noise barriers [26], and preparing strategic noise maps every round as main tools [19].

The END’s execution plan incorporates strategic noise mapping at its heart by utilizing complex methodologies and tools to visualize and calculate sound pressure levels, are they are considered well-known measures of sound quality or annoyance [27]. EU member states have been obliged to prepare strategic noise maps every 5 years since 2007 for agglomerations with over 250,000 inhabitants, and for agglomerations with over 100,000 inhabitants since 2012, in addition to roads with over 3 million vehicles passing per year outside agglomerations [19,28]. These maps are presented in a day–evening–night noise equivalent level L den, and night noise equivalent level L night as harmonized noise indicators [19,29]. This can be done by finding and categorizing noise hotspots and patterns to create a geographical map of these patterns, which in turn helps the official representative of the member states in adapting new policies or regulations regarding noise mitigation [19]. Additionally, noise mapping can simplify tracking advancement or deterioration over time, aiding a member state in evaluating its noise policies and risk communication with the public by transferring these noise maps into risk maps [30]. One vital initiative that has been developed within the END directive is the Common NOise aSSessment methOdS (CNOSSOS-EU) [8,19].

Published in 2015 under the Commission Directive (EU) 2015/996, CNOSSOS-EU utilizes a multidisciplinary strategy or a harmonized method to develop solutions to road traffic noise by taking into consideration the economic, societal, and environmental aspects. In this way, it achieves equilibrium between conservation and growth, which in turn promotes the preservation of natural habitats and cultural settlements from the adverse effects of road traffic noise pollution [31]. For instance, CNOSSOS-EU integrates nature-based solutions within urban planning, such as acoustic landscapes, and green barriers. It also summarizes the noise emissions models of internal combustion vehicles into four main categories, in addition to a fifth “open category” reserved for future needs, such as EVs [32,33,34]. The cooperation between environmentalists, law-makers, and local EU societies is often required to ensure the success of such solutions.

CNOSSOS-EU, in its entirety, studies the road traffic noise generated from two sources, namely: rolling noise, generated from the tire and road surface interaction, and propulsion noise produced by the driveline (engine, exhaust, etc.) of the vehicle [32,33], which is considered zero for EVs [34]. It also introduces the noise emission difference from non-standard road surface types compared to a Reference Road for all vehicle categories and expresses that as correction coefficients presented in Annex II of CNOSSOS-EU documentation [32,35].

Generally, the road surface type and its composition play an important role in defining noise emissions [36,37], and have been under consideration in recent studies of automotive/acoustic engineering [38]. However, it can be argued that the amount of road traffic noise emissions depends on road surfaces of different materials and their various acoustic properties, such as tire model, pavement aging, texture, and mixture [37,38]. Thus, policymakers promoting the use of low-noise pavements can contribute to creating more attractive urban environments to reduce the adverse effects of road traffic noise pollution.

In 2020, Annex II of CNOSSOS-EU documentation was amended and re-published in 2021 with updated correction coefficients for 14 different road surface types [39,40]. However, no specified method was officially published yet to obtain correction coefficients for new road surfaces [41]. Thus, the amendment paved the way for further research on this topic. For instance, the Nord2000 Road Model was utilized to predict the correction coefficients for Swedish roads [40]. In Italy, a study was performed to calculate the correction coefficients for a motorway consisting of 3 sections vary in their characteristics by applying the statistical pass-by (SPB) method according to ISO 11819-1:2001 followed by noise modelling [42]. In Ireland, noise measurements employing the close proximity method (CPX) in line with ISO 11819-2:2017 were conducted to obtain the correction coefficients for the 3 most common road surfaces on the Transport Infrastructure Ireland Network for strategic noise mapping purposes [41]. Moreover, another research was published recently which assesses the correction coefficients for low-noise pavements utilizing the Urban SPB methodology [43].

This article presents a holistic approach to study the influence of different road surface types in the EU member states, specifically focusing on those countries whose data is accessible through commonly used noise mapping software (SoundPLAN, IMMI, and CadnaA), namely Germany, Austria, and Finland. The published national values were compared to the CNOSSOS-EU published values in 2021 for light, medium-heavy, and heavy vehicles by obtaining the rolling and propulsion noise for each road surface type and ignoring all other factors, such as studded tires, temperature, etc. The outcome of the article is expected to fill a gap in the evaluation and comparison of different road surface types, and it could be beneficial in many aspects, such as strategic noise mapping.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Methodology

A Reference Road, which consists of an average of stone mastic asphalt 0/11 and dense asphalt concrete 0/11 between 2 and 7 years old and in representative maintenance condition, is considered the base for rolling noise coefficients (A R, B R) and propulsion noise coefficients (A P, B P) calculations in CNOSSOS-EU, where coefficients (A R, A P) represent the sound power levels at the reference speed (70 km/h) (processed from SEL to L W ) [32,44], and coefficients (B R, B P) represent the slope expressed as log(speed). Both parameters (vehicle’s pass-by speed and sound event level in dB) are recorded from field measurements. Vehicles are grouped into five different categories in the CNOSSOS-EU documentation based on their noise emission characteristics, and the rolling and propulsion noise coefficients vary for each category. These categories are as follows: Category 1 includes light motor vehicles, such as passenger cars, delivery vans weighing less or equal to 3.5 tons, sport utility vehicles, and multi-purpose vehicles including trailers and caravans. Category 2 consists of medium-heavy vehicles, such as delivery vans over 3.5 tons, touring cars, and buses with two axles and twin tire mounting on the rear axle. Category 3 includes heavy-duty vehicles, such as buses and touring cars with three or more axles. Category 4 is for Powered Two-Wheelers, divided into subclasses 4a for mopeds, tricycles, and quads with a motor capacity less or equal to 50 cc, and 4b for motorcycles, tricycles, and quads with a motor capacity of more than 50cc, in addition to Category 5, being an open category for future needs and intended mostly for EVs [32].

To assess the influence of different road surfaces on noise emissions in different EU countries, the rolling noise L WR,i,m and propulsion noise L WP,i,m for each vehicle category for the Reference Road at a constant speed of 70 km/h were first calculated by utilizing the following mathematical expressions and A and B coefficients provided in Annex II of the CNOSSOS-EU document [32,39].

where

Then, the following formula was used to obtain the total sound power level L W,m for each vehicle category for the Reference Road [32].

Since different road surface types can affect the noise emissions of vehicles [32], CNOSSOS-EU methodology introduced two correction coefficients for each road surface type: the

where

In theory, the

It should be mentioned that the propulsion noise correction factor is identical to the rolling noise correction factor at reference speed with a maximum of zero. In other words, porous road surfaces will contribute to decreasing the propulsion noise while dense road surfaces will not increase it [32]. Moreover, all road surfaces were evaluated at a vehicle speed

After obtaining the rolling and propulsion noise corrections, the total sound power level for each road surface L W, road, m was calculated by adding the rolling and propulsion sound power-level corrections to the rolling and propulsion sound power levels calculated for the Reference Road, employing the following formulas.

The same procedure was used to calculate the sound power levels L W,road,m for all different road surfaces, the arithmetic difference of each road surface’s L W from the CNOSSOS-EU Reference Road’s L W was calculated to obtain the noise emissions difference on the EU countries’ road surfaces for each vehicle category (ΔL W,road,m ), where negative calculated values indicate lower noise emissions compared to the Reference Road Surface. However, exceptions were given to Categories 4a and 4b, where rolling noise is not affected. Thus, road surface types are not expected to influence the sound emissions [32,46]. The parameters considered for the road surface L W calculations are summarized in Table 1.

Road surface parameters

| Parameter | Calculation standard | Air temperature | Tyres | Vehicle speed | Road surface conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumption | CNOSSOS-EU (2021) | 20°C | Non-studded tyres | Constant, reference speed 70 km/h* | Dry flat road surface |

*Except for road surfaces allowing a maximum speed of 60 km/h.

This article assumes similar parameters and conditions for all road surface types. As such, it can be argued that the difference in the calculated noise emissions is only due to the effect of the road surface itself.

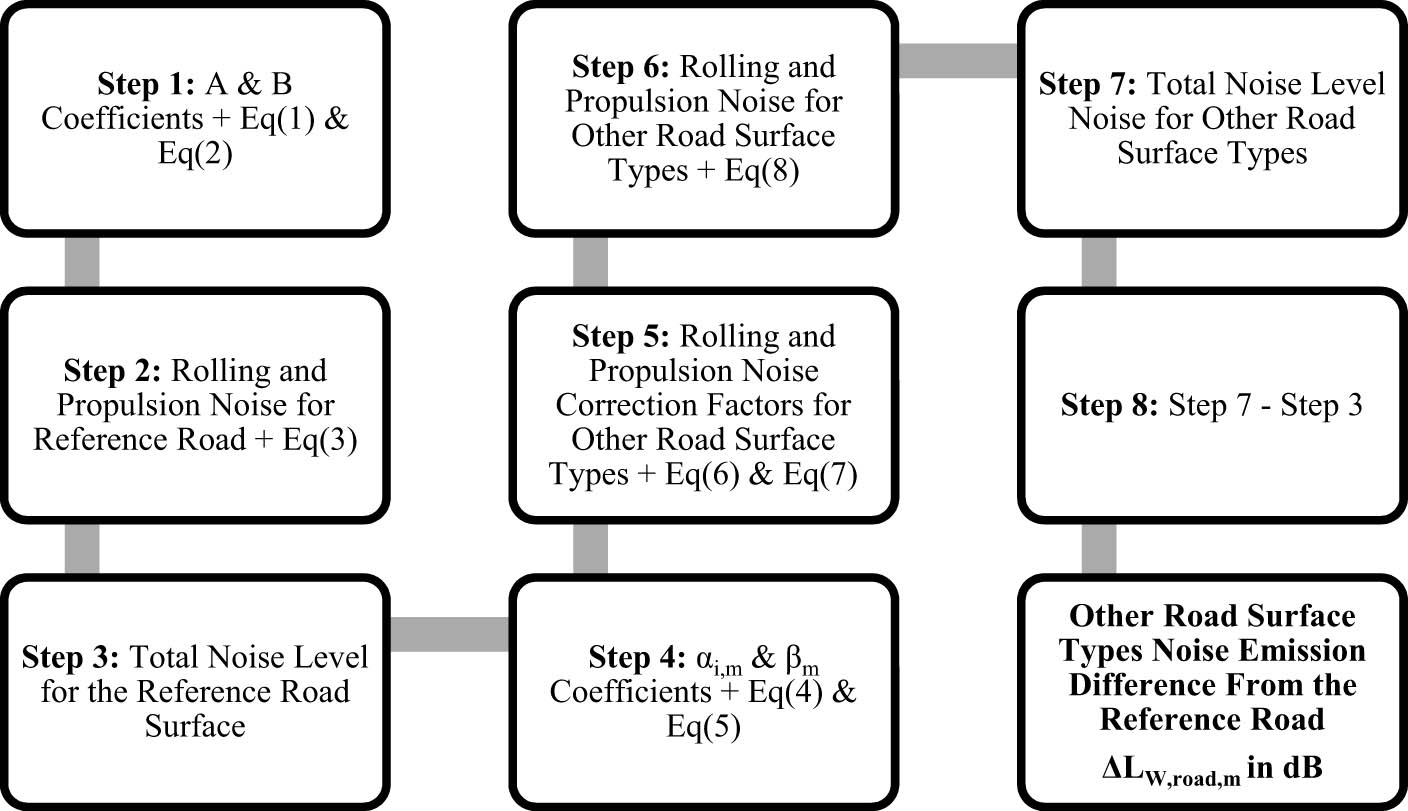

Figure 1 depicts the steps applied to calculate the noise emission difference of the road surface types from the Reference Road Surface.

Noise emission difference calculation steps.

2.2 Road surface types in EU countries

Road surface types and conditions in Europe vary significantly, which can lead to differences in their acoustic properties. For CNOSSOS-EU, no common procedure to assess the acoustic properties of all road surface types was found in the literature [32]. However, a guide containing suggestions for monitoring and checking road surfaces’ acoustic classifications was made [47]. The currently available version of CNOSSOS-EU contains tables in Annex II with

All EU member states are required to implement the transposition of the CNOSSOS-EU method into their national law to comply with EU requirements for the upcoming round of strategic noise mapping. However, this section of the article focuses on the road surface types found in the widely used noise mapping software databases, such as SoundPLAN, IMMI, and CadnaA. Table 2 illustrates the collection of road surface types across Germany [49,50], Austria [50,51], and Finland [52], as well as the road surfaces in the CNOSSOS-EU document. The selection method is based on the type of road surface, such as asphalt concrete, cement concrete, or paving blocks [53,54]. However, no actual connection between the rows is made; the entries are simply listed sequentially under each surface type category. This means that each surface type is presented independently of others based on its classification, without regard to any hierarchical or relational order among the countries.

Road surface types in the examined countries

| Surface type\Country | CNOSSOS-EU | Germany | Austria | Finland |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Reference surface – 0 | National reference (non-fluted mastic asphalt) – G0 | Reference surface – A0 | Reference surface – F0 |

| Bituminous Mixes/Asphalt Concrete Surface – ACS | Single layer porous asphalt ZOAB – NL01 | Open-pored asphalt PA 0/11 – G-ACS-1 | Open porous asphalt – A-ACS-1 | SMA/DAC 16 – F-ACS-1 |

| Two-layer porous asphalt ZOAB – NL02 | Open-pored asphalt PA 0/8 – G-ACS-2 | Noise-reducing stone mastic asphalt – A-ACS-2 | SMA 8 – F-ACS-2 | |

| Two-layer porous asphalt (fine) ZOAB – NL03 | Stone mastic asphalt SMA 0/5 and SMA 0/8 – G-ACS-3 | Stone mastic asphalt – A-ACS-3 | ||

| Stone mastic asphalt SMA-NL5 – NL04 | Stone mastic asphalt SMA 0/8 and SMA 0/11 – G-ACS-4 | Asphalt concrete – A-ACS-4 | ||

| Stone mastic asphalt SMA-NL8 – NL05 | Low-noise mastic asphalt – G-ACS-5 | |||

| Thin layer A – NL13 | Noise-optimised asphalt SMA LA 0/8 – G-ACS-6 | |||

| Thin layer B – NL14 | Thin asphalt wearing courses in hot application (≥70 km/h) – G-ACS-7 | |||

| Asphalt concrete AC 11 (≥70 km/h) – G-ACS-8 | ||||

| Noise-optimised asphalt AC D LOA – G-ACS-9 | ||||

| Cement Concrete Surface – CCS | Brushed down concrete – NL06 | Concretes according to ZTV Beton-StB 07 with washed concrete – G-CCS-10 | washed concrete – A-CCS-5 | |

| Optimized brushed down concrete – NL07 | Noise-reducing washed concrete GK8 – A-CCS-6 | |||

| Fine broomed concrete – NL08 | Noise-reducing washed concrete GK11 (2019) – A-CCS-7 | |||

| Worked surface – NL09 | ||||

| Paving Block Surface or Setts – PBS | Hard elements in herring bone – NL10 | Hard elements with flat surface with b ≤ 5 mm and b + 2f ≤ 9 mm – G-PBS-11 | Even paving stones – F-PBS-3 | |

| Hard elements not in herring bone – NL11 | Hard elements with b > 5 mm or f > 2 mm or other hard elements – G-PBS-12 | Uneven paving stones – F-PBS-4 | ||

| Quiet hard elements – NL12 |

3 Results and discussion

The present section summarizes the results obtained from calculating ΔL W,road,m for light, medium heavy, and heavy vehicles for CNOSSOS-EU road surfaces in Germany, Austria, and Finland as depicted in Table 3. Negative values indicate lower noise emissions compared to the Reference Road Surface at a constant speed of 70 km/h, except for road surfaces that allow a maximum speed of 60 km/h, which were evaluated at that speed. As CNOSSOS-EU only considers propulsion noise in Categories 4a and 4b, different road surface types at the evaluated vehicle speeds are not expected to influence the noise emissions [32,33,46]. Therefore, they were not evaluated.

Sound power level difference from the reference surface in dB

| Country | Pavement type | Road surface | ΔL W,road,m in dB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m = 1 | m = 2 | m = 3 | |||

| CNOSSOS-EU | Reference | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ACS | NL01 | −1.1 | −3.1 | −2.8 | |

| NL02 | −4.5 | −5.3 | −5.3 | ||

| NL03 | −6.6 | −5.8 | −5.7 | ||

| NL04 | −1.8 | 0 | 0 | ||

| NL05 | −0.8 | 0 | 0 | ||

| NL13 | −3.3 | −1.3 | −1.2 | ||

| NL14 | −4.9 | −1.3 | −1.2 | ||

| CCS | NL06 | 1.8 | −0.2 | −0.2 | |

| NL07 | 0.2 | −1.9 | −1.7 | ||

| NL08 | 1.7 | 2 | 2 | ||

| NL09 | 2.8 | −0.4 | −0.2 | ||

| PBS | NL10* | 2.3 | 4.4 | 4.8 | |

| NL11* | 6.1 | 8.2 | 8.4 | ||

| NL12* | −1.4 | 2.2 | 2.2 | ||

| Germany | National Reference | G0 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 3 |

| ACS | G-ACS-1 | −4 | −1.9 | −3.1 | |

| G-ACS-2 | −5.3 | −4.4 | −5.2 | ||

| G-ACS-3* | −1.5 | 1.0 | 0.1 | ||

| G-ACS-4 | −1 | 1.6 | 0.7 | ||

| G-ACS-5 | −1.2 | 2 | 1.3 | ||

| G-ACS-6 | −2.1 | -2 | -3.2 | ||

| G-ACS-7 | −2 | 1.1 | 0.2 | ||

| G-ACS-8 | −1.1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | ||

| G-ACS-9* | −2.4 | 1.5 | 0.2 | ||

| CCS | G-CCS-10 | −0.4 | 1.1 | 0.5 | |

| PBS | G-PBS-11* | 3 | 4.1 | 3.1 | |

| G-PBS-12* | 7 | 7.8 | 6.9 | ||

| Austria | Reference | A0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ACS | A-ACS-1 | −3.7 | −3.1 | −3.3 | |

| A-ACS-2 | −3 | −1.1 | −1.1 | ||

| A-ACS-3 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.9 | ||

| A-ACS-4 | −0.5 | 1.3 | 1.5 | ||

| CCS | A-CCS-5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | |

| A-CCS-6 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||

| A-CCS-7 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 4.1 | ||

| Finland | Reference | F0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ACS | F-ACS-1 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1 | |

| F-ACS-2 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.5 | ||

| PBS | F-PBS-3* | 2.7 | 1.0 | 1.1 | |

| F-PBS-4* | 5.6 | 2.2 | 2.4 | ||

*Surfaces allowing a maximum speed of 60 km/h.

3.1 Sound power level difference for CNOSSOS-EU road surfaces

Figure 2 compares the noise reduction capabilities for light motor vehicles and medium to heavy motor vehicles of the road surfaces considered in the CNOSSOS-EU calculations. According to the results, Asphalt Concrete Surfaces were found to have the highest noise reduction capabilities compared to the Reference Road Surface. Moreover, they generate lower sound emissions from Category 1 vehicles, except for NL01. Road surfaces, such as NL13 and NL14 are more suitable for roads where the proportion of light motor vehicle traffic is higher, while NL07 can be installed on roads where more medium to heavy vehicle pass-bys are expected. Moreover, the best noise reduction capabilities were found to be for the “Two-layer porous asphalt (fine) ZOAB – NL03,” which can decrease noise by 6.6 dB for light motor vehicles and an average of 5.75 dB for Category 2 and 3 vehicles. On the other hand, “Hard elements not in herringbone – NL11” can result in increasing Category 1 emissions by 6.1 dB and Category 2 and 3 emissions by 8.3 dB. However, since the maximum allowed speed on PBS is 60 km/h [32], it is recommended to avoid the use of such surfaces in urban areas with high populations in new development.

Noise reduction capabilities of CNOSSOS-EU road surfaces.

3.2 Sound power level difference for German road surfaces

In Germany, “Open-pored asphalt PA 0/8 – G-ACS-2” was found to have the highest noise reduction capabilities for all vehicle categories, while “Hard elements with b > 5 mm or f > 2 mm or other hard elements – G-PBS-12” increases the sound emissions significantly. On the other hand, and unlike CNOSSOS-EU road surfaces, G-CCS-10 can result in increasing the sound emissions of medium to heavy motor vehicles. However, road surfaces in Germany showed noticeable fluctuations between Category 2 and Category 3 vehicles compared to other countries, with higher emission increase from Category 2 vehicles. This trend was mainly, but not exclusively, observed on road surfaces allowing a maximum speed of 60 km/h, which can be attributed to the fact that rolling noise becomes dominant at lower speeds in Category 2 vehicles compared to Category 3 vehicles. This difference may contribute to the larger variations between Categories 2 and 3, based on the acoustic properties of the respective road surface types. As a result, the average noise reduction of both categories is not representative of each category’s reduction. The difference in the emissions of Category 2 and 3 vehicles is related to the

(a) and (b) Noise reduction capabilities of German road surfaces.

3.3 Sound power level difference for Austrian and Finnish road surfaces

In Austria and Finland, fewer road surfaces were evaluated in the process of transposing CNOSSOS-EU into the national law, with no Paving Block Surfaces in Austria and no Cement Concrete Surfaces in Finland [50,51,52]. “Open porous asphalt – A-ACS-1” has the highest noise reduction capabilities in all categories in Austria, while A-CCS-7 is the least in terms of noise reduction. Moreover, the Finnish ACS road surfaces were found to have slight to no influence on noise emissions compared to the Reference Road Surface in all categories. However, both PBS proved that they are not capable of reducing sound emissions; on the contrary, they increase noise emissions in all categories. Figure 4 shows the comparison of the noise reduction capabilities for light motor vehicles and medium to heavy motor vehicles of the road surfaces considered representative in Austria and Finland for strategic noise mapping purposes.

Noise reduction capabilities of Austrian and Finnish road surfaces.

3.4 General discussion

The results presented in Table 3 indicate that road surface types have a significant influence on noise levels calculated from the Reference Road Surface for all categories. Furthermore, noise levels for the same road surface type vary in the evaluated countries. For instance, ΔL W,SMA 0/8,1 varies from −1.0 to −0.5 dB, ΔL W,SMA 0/8,2 varies from −0.5 to 1.6 dB, and ΔL W,SMA0/8,3 varies from −0.5 to 0.7 dB. These deviations can be linked to the different acoustical characteristics among similar road surface types in EU countries [32]. Alternatively, porous asphalt pavements were found to have the highest noise reduction capabilities, contributed by many factors, such as the number of surface layers, air–void ratio, thickness, and texture. Generally, when the air-void ratio increases, the noise reduction increases [55]. That being said, the air-void ratio is recommended to be controlled at 20% [56]. Moreover, it was observed that for a 6 cm-thick surface with double layering, noise reduction capabilities are reduced when the bottom layer is thinner than the top layer. Additionally, the increase in the texture depth of pavements with very thin surfacing with small aggregates contributes to enhancing the sound absorption performance but extends the vibration distances of the layers which leads to generating more vibration noise. On the other hand, smooth surfaces generate less noise than surfaces with few and small texture patterns [55].

However, the recommended scope of application for porous asphalt pavements is roads with low traffic flow, without junctions, narrow curvatures, or turning lanes. This is due to durability issues of porous roads when the traffic load is high. When the weight on the porous surface increases, the voids tend to compress which increases the necessity of rehabilitation and maintenance and reduces cost-efficiency [57].

In general, Paving Block Surfaces or Setts exhibit higher noise levels compared to the Reference Road Surface across all categories, which can be linked to the low air-void ratio that negatively affects the noise levels. For instance, light motor vehicles showed the same behavior on CNOSSOS-EU, German, and Finnish herringbone surfaces with noise levels increasing by 2.5–2.8 dB. However, heavy vehicles are expected to increase noise levels by 1.3–5.3 dB on the same surfaces compared to the Reference Road. Therefore, the variations in the calculated noise levels may pose challenges in adopting CNOSSOS-EU without aligning national laws with the CNOSSOS-EU methodology. To further support this observation, relevant literature was reviewed to compare the noise reduction capabilities of different pavements. Generally, porous sound absorption, resonance sound absorption, control of the sound propagation path, vibration damping, and connected pore excretion or a combination of these, are the mechanisms used to reduce the pavement noise [58]. For example, Porous Asphalt Pavements can effectively reduce noise levels by up to 6 dB [59], while noise levels measured on Rubber Asphalt Pavements were less by 1–3 dB in comparison with ordinary asphalt pavements [60]. Moreover, Porous Elastic Road Surfaces were found to be capable of reducing noise levels by 7–12 dB in comparison with Dense Asphalt Pavements [61,62,63]. Additionally, low-noise pavements have proven to be among the most effective measures for mitigating road traffic noise. However, accurately estimating their health benefits poses a challenge, as their acoustical characteristics are yet to be fully assessed [43]. In general, different techniques were used to evaluate the noise reduction capabilities of different pavement types [58]. Therefore, the results obtained from previous research may vary if they were evaluated using the CNOSSOS-EU methodology.

Furthermore, it is necessary to keep an eye on future modifications on the road surface types in the CNOSSOS-EU document. For instance, if a new pavement is widespread in Europe, such as new formations of low-noise pavements, the affected countries should evaluate the new pavement’s influence on road traffic noise emissions and update their regulations accordingly. Low-noise pavements are typically implemented during road resurfacing or when required by law. However, the END’s 2023 evaluation recommended that member states consider them as a key mitigation measure, in addition to quiet tyres and road speed limits reduction [25]. The EU has enabled member states to define new surfaces in the CNOSSOS-EU road traffic model by introducing their specific

The comparison presented in this article is limited to countries that have their national road surface types and their coefficients accessible in the noise mapping software after adopting CNOSSOS-EU at the national level, specifically Germany, Austria, and Finland. The results from this work can serve as a valuable foundation for other EU countries that are currently transitioning the CNOSSOS-EU method to their national law for comparison purposes.

This groundwork will support further investigations into a broader range of road surfaces, addressing the deviations in noise levels across different road surfaces. Consequently, the outcome of this work is expected to be useful for noise mapping experts in the industrial field, as it provides a summary of the difference in noise levels on various road surface types across different countries.

Therefore, when selecting the applicable road surface type from the noise mapping software database for road traffic noise mapping projects that employ the CNOSSOS-EU calculation method, it is crucial to consider that similar road surface types can vary from one country to another. To achieve accurate results, the CNOSSOS-EU method should only be applied to countries whose data is already available in the noise mapping software databases. This approach ensures consistency and reliability in noise mapping across different regions and road surfaces in the EU.

4 Conclusion

In this article, the influence of road surface types in Europe on the total sound power levels of light, medium heavy, and heavy vehicles was evaluated by excluding all other parameters indicated in CNOSSOS-EU such as temperature, studded tires, etc. A virtual road with an average of stone mastic asphalt 0/11 and dense asphalt concrete 0/11 between 2 and 7 years old and in representative maintenance condition was selected to be the base for the road traffic noise calculations, and is referred to as “Reference Road.”

Data in the literature are available in 1/1 octave bands for rolling and propulsion noise separately. Therefore, the summation of both noise sources was calculated by utilizing the CNOSSOS-EU formulas to obtain the total sound power level for each road surface type, and then, the obtained value was subtracted from the total sound power level of the Reference Road, which is referred to in this article as ΔL W,road,m . A negative difference indicates that the noise level for the evaluated surface is expected to be lower than that for the Reference Road. Based on the results, it was observed that ΔL W,road,m for the same road surface type in different countries varies significantly in some cases from CNOSSOS-EU road surface types, which can be related to the uneven sound characteristics of the similar road surface types in Europe.

Although this article focuses on highlighting the differences between accessible coefficients in the noise mapping software for different road surfaces at the national level, in Germany, Austria, and Finland, it paves the way for future possible comparisons. This will become feasible once all EU member states publish their road surface coefficients officially, following the transposition of CNOSSOS-EU into their respective laws.

In summary, the results show that road surface type correction factors presented in the CNOSSOS-EU documentation do not apply to all EU countries’ road surface types despite being in the same pavement category. However, the approach and methodology utilized in CNOSSOS-EU for road traffic noise calculations shall be adopted in all European countries to calculate their national road surface correction factors which urges the necessity of the transposition of CNOSSOS-EU in all EU member states to serve several purposes such as the preparation of strategic maps.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Omar Odeh: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing – original draft; Aiham Khayyat: resources, writing – original draft; and Dénes Kocsis: conceptualization, supervision, validation, writing – review & editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] European Environmental Agency. Managing exposure to noise in Europe. 2017. https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/human/noise/sub-sections/noise-in-europe-updatedpopulation-exposure.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Juhani P. A-weighted sound pressure level as a loudness/annoyance indicator for environmental sounds – Could it be improved? Appl Acoust. 2007;68(1):58–70. 10.1016/j.apacoust.2006.02.004.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Ablenya B, Jarl K, Kampen CV. Noise barriers as a mitigation measure for highway traffic noise: Empirical evidence from three study cases. J Environ Manag. 2024;367:121963. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121963.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Hänninen O, Knol AB, Jantunen M, Lim TA, Conrad A, Rappolder M, et al. Environmental burden of disease in Europe: assessing nine risk factors in six countries. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(5):439–46. 10.1289/ehp.1206154.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] World Health Organization. Environmental health inequalities in Europe: Second assessment report. Copenhagen, Denmark: Regional Office for Europe; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Mac Domhnaill C, Douglas O, Lyons S, Murphy E, Nolan A. Road traffic noise and cognitive function in older adults: A cross-sectional investigation of The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1814. 10.1186/s12889-021-11853-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Clark C, Paunovic K. WHO environmental noise guidelines for the European region: A systematic review on environmental noise and quality of life, wellbeing and mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2400. 10.3390/ijerph15112400.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Murphy E, Faulkner JP, Douglas O. Current state-of-the-art and new directions in strategic environmental noise mapping. Curr Pollut Rep. 2020;6:54–64. 10.1007/s40726-020-00141-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Hume K, Ahtamad M. Physiological responses to and subjective estimates of soundscape elements. Appl Acoust. 2013;74(2):275–81. 10.1016/j.apacoust.2011.10.009.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] World Health Organization. Environmental noise guidelines for the European region. Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2018. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289053563.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Cai Y, Ramakrishnan R, Rahimi K. Long-term exposure to traffic noise and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence between 2000 and 2020. Environ Pollut. 2021;269:116222. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116222.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Ndrepepa A, Twardella D. Relationship between noise annoyance from road traffic noise and cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis. Noise Health. 2011;13(52):251–9. 10.4103/1463-1741.80163.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Lee PJ, Park SH, Jeong JH, Choung T, Kim KY. Association between transportation noise and blood pressure in adults living in multi-storey residential buildings. Environ Int. 2019;132:105101. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105101.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Bodin T, Albin M, Ardö J, Stroh E, Östergren P-O, Björk J. Road traffic noise and hypertension: results from a cross-sectional public health survey in southern Sweden. Environ Health. 2009;8(1):38. 10.1186/1476-069X-8-38.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Thompson R, Smith RB, Karim YB, Shen C, Drummond K, Teng C, et al. Noise pollution and human cognition: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of recent evidence. Environ Int. 2022;158:106905. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106905.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Schubert M, Hegewald J, Freiberg A, Starke KR, Augustin F, Riedel-Heller SG, et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders and transportation noise among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3336. 10.3390/ijerph16183336.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Śliwińska-Kowalska M, Zaborowski K. WHO environmental noise guidelines for the European region: A systematic review on environmental noise and permanent hearing loss and tinnitus. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(10):1139. 10.3390/ijerph14101139.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Džambas T, Ivančev A, Dragčević V, Bezina Š. Analysis of road traffic noise in an urban area in Croatia using different noise prediction models. Noise Mapp. 2024;11(1):20240003. 10.1515/noise-2024-0003.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] European Union. Directive 2002/49/EC of the European parliament and the Council of 25 June 2002 relating to the assessment and management of environmental noise. Off J Eur Communities, L. 2002;189:12–26.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] European Commission. Recommendation concerning the guidelines on the revised interim computation methods for industrial noise, aircraft noise, road traffic noise and railway noise, and related emission data. Off J Eur Union, L. 2003;212:0049–64.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] King EA, Rice HJ. The development of a practical framework for strategic noise mapping. Appl Acoust. 2009;70(8):1116–27. 10.1016/j.apacoust.2009.01.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, The European Green Deal. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Pathway to a Healthy Planet for All EU Action Plan: ‘Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil’. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2024/1735 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on establishing a framework of measures for strengthening Europe’s net-zero technology manufacturing ecosystem and amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1724. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2024.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the Implementation of the Environmental Noise Directive in accordance with Article 11 of Directive 2002/49/EC. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Leiva C, Arenas C, Vilches LF, Arroyo F, Luna-Galiano Y. Assessing durability properties of noise barriers made of concrete incorporating bottom ash as aggregates. Eur J Environ Civ Eng. 2017;23(12):1485–96. 10.1080/19648189.2017.1355852.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Hall DA, Irwin A, Edmondson-Jones M, Phillips S, Poxon JEW. An exploratory evaluation of perceptual, psychoacoustic and acoustical properties of urban soundscapes. Appl Acoust. 2013;74(2):248–54. 10.1016/j.apacoust.2011.03.006.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Bolognese M, Fredianelli L, Stasi G, Ascari E, Crifaci G, Licitra G. Citizens’ exposure to predominant noise sources in agglomerations. Noise Mapp. 2024;11(1):20240007. 10.1515/noise-2024-0007.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Mac Domhnaill C, Douglas O, Lyons S, Murphy E, Nolan A. Road traffic noise, quality of life, and mental distress among older adults: evidence from Ireland. Cities Health. 2022;6(3):564–74. 10.1080/23748834.2022.2084806.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Selamat FE, Tagusari J, Matsui T. Mapping of transportation noise-induced health risks as an alternative tool for risk communication with local residents. Appl Acoust. 2021;178:107987. 10.1016/j.apacoust.2021.107987.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Faulkner J-P, Murphy E. Road traffic noise modelling and population exposure estimation using CNOSSOS-EU: Insights from Ireland. Appl Acoust. 2022;192:108692. 10.1016/j.apacoust.2022.108692.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Commission Directive (EU). 2015/996 of 19 May 2015, establishing common noise assessment methods according to Directive 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. Off J Eur Union. 2015;168:1–823.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Tombolato A, Brambilla G, Troccoli A, Sanchini A, Bonomini F. Basics of meteorology for outdoor sound propagation and related modelling issues. Noise Mapp. 2024;11(1):20240006. 10.1515/noise-2024-0006.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Licitra G, Bernardini M, Moreno R, Bianco F, Fredianelli L. CNOSSOS-EU coefficients for electric vehicle noise emission. Appl Acoust. 2023;211:109511. 10.1016/j.apacoust.2023.109511.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Ledee FA, Goubert L. The determination of road surface corrections for CNOSSOS-EU model for the emission of road traffic noise. Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress on Acoustics. 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Gardziejczyk W. Influence of the speed of electric vehicles on noise emission level. Sustain Cities Soc. 2022;85:104004. 10.1016/j.scs.2022.104004.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Bueno M, Luong J, Terán F, Viñuela U, Paje SE. Macrotexture influence on vibrational mechanisms of the tyre–road noise of an asphalt rubber pavement. Int J Pavement Eng. 2013;15(7):606–13. 10.1080/10298436.2013.790547.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Knabben RM, Trichês G, Gerges SNY, Vergara EF. Evaluation of sound absorption capacity of asphalt mixtures. Appl Acoust. 2016;114:266–74. 10.1016/j.apacoust.2016.08.008.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Commission Delegated Directive (EU). 2021/1226 of 21 December 2020 amending, for the purposes of adapting to scientific and technical progress, Annex II to Directive 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards common noise assessment methods. Off J Eur Union. 2021;269:65–142.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Larsson K. Swedish input data for road traffic noise in CNOSSOS-EU. Proceedings of BNAM. 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Transport Infrastructure Ireland. Common noise assessment methods in Europe (CNOSSOS-EU): Interim Road Surface Correction Factors for National Roads in Ireland. Technical Report RE-ENV-07006. Dublin, Ireland: Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII); 2022.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Borchi F, Colucci G, Falchi A, Pulella P, Luzzi S, Ciampini A, et al. A new procedure to determine correction coefficients for CNOSSOS database for motorways road surfaces. Proceedings of the 10th Convention of the European Acoustics Association. 2023. 10.61782/fa.2023.1194.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Ascari E, Cerchiai M, Fredianelli L, Melluso D, Licitra G. Tuning user-defined pavements in CNOSSOS-EU towards reliable estimates of road noise exposure. Transp Res Part D: Transp Environ. 2024;130:104195. 10.1016/j.trd.2024.104195.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] van Blokland G, Peeters B. Proposal for a procedure to determine the source power of road vehicles for CNOSSOS-EU. Technical Report. Aalsmeer, Netherlands: M+P Consulting Engineers; 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Lédée FA. Report on the compatibility of the proposed noise characterization procedure with CNOSSOS-EU and national calculation methods. Deliverable D2.5 of the ROSANNE Project. Bouguenais, France: ROSANNE Project Consortium; 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Evensen KB, Dutilleux G, Olsen H. Adaptation of Cnossos from octave bands to 1/3 octave band. SINTEF, Norway: SINTEF Report No. 2021:00435; 2021. p. 24. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2827888.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Morgan P. Guidance manual for the implementation of low-noise road surfaces. EU-FP5 project SILVIA, final report. Brussels: FEHRL; 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Minister of Infrastructure and the Environment in Netherlands. RMG2012 - Reken- en meetvoorschrift geluid 2012 (Noise calculation and measurement regulations 2012). The Hague, Netherlands: Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat. Reken- en meetvoorschrift geluid (Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management); 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety/Federal Ministry for Transport and Digital Infrastructure in Germany. BUB - Berechnungsmethode für den Umgebungslärm von bodennahen Quellen (Calculation method for ambient noise from ground-level sources-roads, railways, industry, and commerce). Berlin, Germany: Federal Ministry for Transport and Digital Infrastructure; 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] SoundPLAN GmbH. SoundPLAN 9.0 noise mapping software database. Backnang, Germany: SoundPLAN GmbH; 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Austrian Research Association for Roads, Railways, and Transport. RVS 04.02.11 Berechnung von Schallemissionen und Lärmschutz (Calculation of sound emissions and noise protection). Vienna, Austria: Austrian Research Association for Roads, Railways and Transport; 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Wölfel Group. IMMI Noise Mapping Software Database. Höchberg, Germany: Wölfel; 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Jonasson H, Sandberg U, van Blokland G, Ejsmont J, Watts G, Luminari M. Source modelling of road vehicles. Deliverable 9 of the Harmonoise Project, Technical Report. Borås, Sweden: Swedish National Testing and Research Institute (SP); 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Conter M. Proposal for a draft European standard on the characterization of the acoustic properties of road surfaces. Deliverable D2.4 of the ROSANNE Project. Vienna, Austria: Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH; 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Liu M, Huang X, Xue G. Effects of double-layer porous asphalt pavement of urban streets on noise reduction. Int J Sustain Built Environ. 2016;5(1):165–72. 10.1016/j.ijsbe.2016.02.001.Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Xue G. Research on low noise asphalt pavements of urban road (Doctoral dissertation). Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China: Southeast University; 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Guo Z, Yi J, Xie S, Chu J, Feng D. Study on the influential factors of noise characteristics in dense-graded asphalt mixtures and field asphalt pavements. Shock Vib. 2018;2018:5742412. 10.1155/2018/5742412.Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Ling S, Yu F, Sun D, Sun G, Xu L. A comprehensive review of tire-pavement noise: Generation mechanism, measurement methods, and quiet asphalt pavement. J Clean Prod. 2021;287:125056. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125056.Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Menglan Z, Liangqing P, Chaofan W, Bangyao T. Experimental study of the performance of ultrathin asphalt friction course. J Wuhan Univ Technol. 2012;34(4):637–41. 10.3963/j.issn.1671-4431.2012.04.008.Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Kehagia F, Mavridou S. Noise reduction in pavement made of rubberized bituminous top layer. Open J Civ Eng. 2014;4(3):245–52. 10.4236/ojce.2014.43017.Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Biligiri KP, Kalman B, Samuelsson A. Understanding the fundamental material properties of low-noise poroelastic road surfaces. Int J Pavement Eng. 2013;14(1):89–100. 10.1080/10298436.2011.608798.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Sandberg U, Goubert L. Persuade: a European project for exceptional noise reduction by means of poroelastic road surfaces. In 40th International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering 2011 (INTER-NOISE 2011). 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Świeczko-Żurek B, Ejsmont J, Motrycz G, Stryjek P. Risks related to car fire on innovative poroelastic road surfaces-PERS. Fire Mater. 2015;39(2):191–8. 10.1002/fam.2231.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Sound event detection by intermittency ratio criterium and source classification by deep learning techniques

- Influence of land cover on noise simulation output – A case study in Malmö, Sweden

- Main design parameters to build acoustic maps by measurements in Uruguay

- Combining generative adversarial networks with urban noise mapping

- Review Article

- A review of the studies investigating the effects of noise exposure on humans from 2017 to 2022: Trends and knowledge gaps

- Letter to the Editor

- Rethinking environmental noise assessment through a noise footprint framework

- Special Issue: Strategic noise mapping in the CNOSSOS-EU era - Part II

- CNOSSOS-EU road surface types: Evaluation of the influence of different national values on noise emissions

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Sound event detection by intermittency ratio criterium and source classification by deep learning techniques

- Influence of land cover on noise simulation output – A case study in Malmö, Sweden

- Main design parameters to build acoustic maps by measurements in Uruguay

- Combining generative adversarial networks with urban noise mapping

- Review Article

- A review of the studies investigating the effects of noise exposure on humans from 2017 to 2022: Trends and knowledge gaps

- Letter to the Editor

- Rethinking environmental noise assessment through a noise footprint framework

- Special Issue: Strategic noise mapping in the CNOSSOS-EU era - Part II

- CNOSSOS-EU road surface types: Evaluation of the influence of different national values on noise emissions