Vortex beam nanofocusing and optical skyrmion generation via hyperbolic metamaterials

-

Wenhao Li

, Anthony Clabeau

und Natalia M. Litchinitser

Abstract

While spin angular momentum is limited to ±ℏ, orbital angular momentum (OAM) is, in principle, unbounded, enabling tailored optical transition rules in quantum systems. However, the large optical size of vortex beams hinders their coupling to nanoscale platforms such as quantum emitters. To address this challenge, we experimentally demonstrate the subdiffraction focusing of an OAM-carrying beam using a hypergrating, a flat meta-structure based on a multilayered hyperbolic composite. We show that our structure generates and guides high-wave vector modes to a deeply subwavelength spot and experimentally demonstrate the focus of an OAM-carrying beam on a spot size of ∼ λ/3. We also show how the proposed platform facilitates the formation of an optical skyrmion with spin textures as small as λ/250, opening new avenues for controlling light–matter interactions.

1 Introduction

The realization that light can carry OAM, in addition to its intrinsic spin, has expanded the landscape of optical physics by introducing new degrees of freedom for encoding information, manipulating matter, and tailoring fundamental light–matter interactions [1], [2], [3]. Unlike spin angular momentum, which is limited to ±ℏ, OAM is, in principle, unbounded and associated with helical phase fronts carrying quantized topological charge, allowing controlled delivery of angular momentum to micro- and nanoscale systems, enabling a range of phenomena, including rotational Doppler shifts, angular uncertainty relations, and spin–orbit coupling, while also opening pathways to modify selection rules in quantum systems [4]. Consequently, vortex beams, structured light fields carrying OAM, have become indispensable tools in fields such as quantum information processing [5], optical micromanipulation [6], quantum communication [7], and quantum memories [8], spurring efforts to develop compact devices for generating and manipulating OAM beams on-chip [9], [10], [11], [12], [13].

However, the spatial extent of vortex beams, which scale with topological charge, inherently limits their interaction with nanoscale systems, where strong coupling requires tight spatial confinement. While structured light can be readily engineered at the macroscale, applications such as probing dipole-forbidden transitions, subwavelength imaging, and on-chip integrated optics demand significantly reduced beam sizes [14], [15], [16], [17]. To address this demand, several theoretical strategies have proposed reshaping the emitter’s photonic environment using nanostructures or metamaterials to enhance light–matter interactions [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25] locally. However, these methods often suffer from significant fabrication challenges, limited scalability, or material-related optical losses, restricting their practical use. At the same time, a growing body of theoretical work in solid-state physics and quantum optics has highlighted the potential of tightly confined vortex beams themselves, independent of emitter-side structuring, to drive new physical phenomena, including OAM-induced currents, spin-controlled magnetic responses, and transitions that are otherwise forbidden for plane waves in systems such as quantum dots, nanorings, and semiconductor heterostructures [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]. Notably, many such processes exhibit transition rates that increase as the beam size decreases [31], reinforcing the need for an optical method to compress OAM beams while preserving their topological structure. However, despite decades of theoretical developments and partial solutions, an experimental platform capable of delivering this functionality in a planar, scalable, and material-efficient form has yet to emerge.

To bridge this long-standing gap, we experimentally demonstrate a new approach for compressing vortex beams to deep subwavelength dimensions based on a flat hyperbolic metamaterial (HMM) engineered with extreme dielectric anisotropy and governed by a hyperbolic dispersion relation. The strong focusing capability of the proposed structure, referred to as a hypergrating, arises from the combination of a Fresnel grating, which generates high in-plane wavevector modes, with planar slabs of an anisotropic medium that guide and converge these modes at a focal spot [32]. Experimental measurements show that an OAM-carrying beam is focused on a spot approximately one-third of the vacuum wavelength λ, smaller than, the diffraction-limited spot size achieved with high-NA objective lenses [33]. We show that the measured intensity and polarization profiles are in excellent agreement with theoretical predictions, confirming the robustness of the focusing mechanism. Numerical analysis of the electromagnetic field distribution at the focal plane further reveals that, under appropriate design conditions, the structure can support the formation of optical skyrmions, characterized by spin textures as small as λ/250, arising from the interplay between spin–orbit coupling and tightly confined optical modes.

2 Concept and theoretical prediction

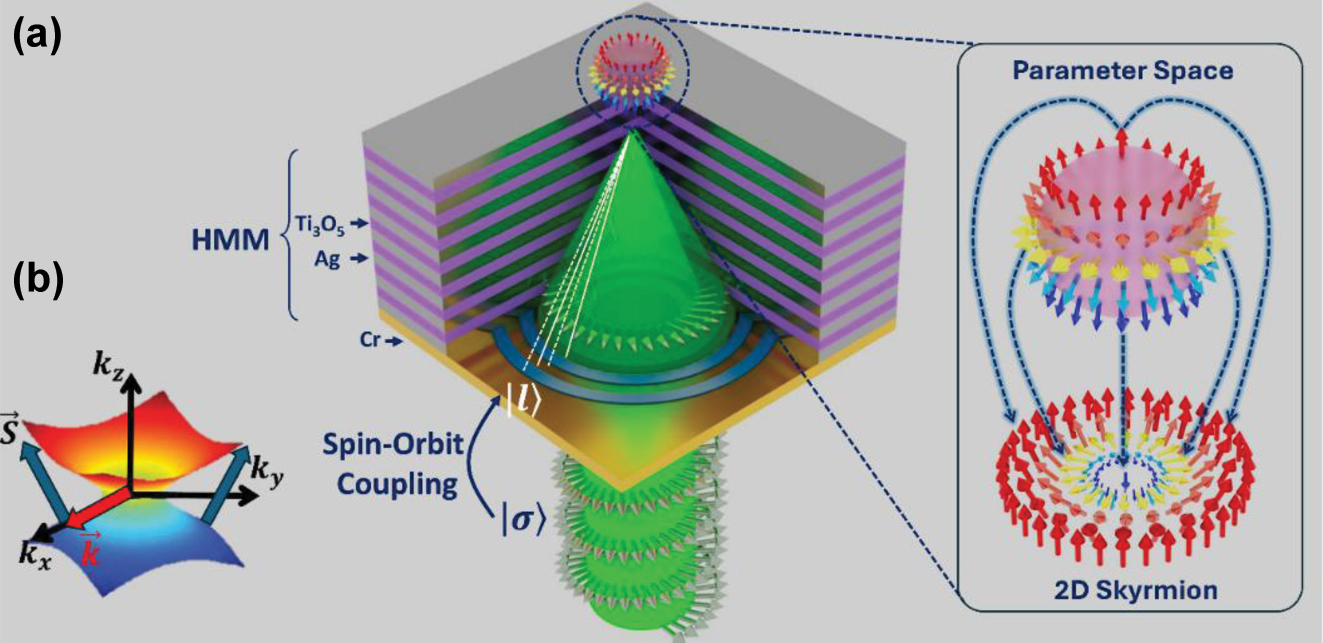

The internal structure of vortex beams inherently contains phase singularities, which fundamentally distinguish them from Gaussian beams and introduce challenges for tight spatial focusing, such that even under high numerical aperture focusing, beams carrying a topological charge of 1 typically produce focal spots larger than the free-space wavelength, with diameters exceeding λ by 10 % [33]. To tackle this problem, here, we propose a flat HMM slab that is combined with a diffractive element to form a compact focusing platform, referred to as a hypergrating, which simultaneously generates high in-plane wavevector components and guides them toward a deeply subwavelength focal region [32]. In particular, as shown in Figure 1a, circularly polarized light is first converted into a vortex beam, which is then coupled into and compressed within the HMM, resulting in strong spatial confinement of the beam’s angular momentum content.

Schematic diagram of a hypergrating structure and its working principle. (a) The Fresnel grating ensures that the beams leaving the slits in the direction of the focal spot interfere constructively with each other. Solid and dashed white lines represent directions of the interfering beams (as defined by their Poynting flux); phase shifts between the beams propagating along two solid lines and two dashed lines are multiples of 2π, while the phase shift between the beams propagating along neighboring solid and dashed lines is π. (b) Illustration of the hyperbolic effective medium response of the metamaterial (note the negative phase velocity of the plane waves).

The HMM is composed of a ten-bilayer Ag/Ti3O5 stack designed to operate in the type-II hyperbolic regime at wavelength of 532 nm. The dielectric response of the HMM is modeled using effective medium theory (EMT), with in-plane and out-of-plane components given by

3 Nanofocusing of vortex beams

A Fresnel grating was fabricated by milling the odd Fresnel zones on a Cr film, as shown in Figure 2a. Owing to the subwavelength radial spacing between adjacent Fresnel zones, the grating exhibits a pronounced polarization-dependent transmission behavior, wherein radially polarized light is transmitted with significantly higher efficiency than its azimuthally polarized counterpart, such that when a circularly polarized beam is incident on the structure, the azimuthal component is preferentially absorbed or reflected, while the radial component passes through, resulting in an effective conversion of the incident spin angular momentum into orbital angular momentum. To quantify the relative contributions of OAM and residual SAM content in the output beam, we performed full-wave simulations in COMSOL by modeling the transmission of a circularly polarized beam through the Cr Fresnel grating (see Supplementary Material). As shown in Figure 2b, the electric field vectors in the transmitted beam exhibit a predominantly radial orientation, consistent with the generation of an OAM-carrying mode [38]. From the simulated field distribution, we estimate that approximately 83 % of the transmitted power corresponds to the radially polarized OAM beam, with the remaining 17 % associated with residual circular polarization. The SAM to OAM conversion was confirmed by acquiring the phase information of the output beam using an interference measurement. While direct interference measurement of a polarized beam is tricky, the radially polarized beam with topological charge l = −1 can be represented as a linear combination of left-handed and right-handed circularly polarized beams with charge l = 0 and l = −2 as [39]:

where φ denotes the azimuthal angle.

Spin- to orbital-angular momentum conversion. (a) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of a Fresnel grating and the Fresnel grating rings’ radii (designed and experimentally measured). (b) Vector plot of the electric field (red arrows) in the transverse plane and the phase distribution of the radially polarized component (E r ) of the beam at 60 nm after the Fresnel grating. (c) Interference pattern of the right-handed circularly polarized (RCP) and left-handed circularly polarized (LCP) components of the output beam. (d) Experimentally measured Stokes parameters distributions in the far field (inserted: Stokes parameters calculated from simulation). (e) Intensity distribution among components of the beam after the Fresnel grating.

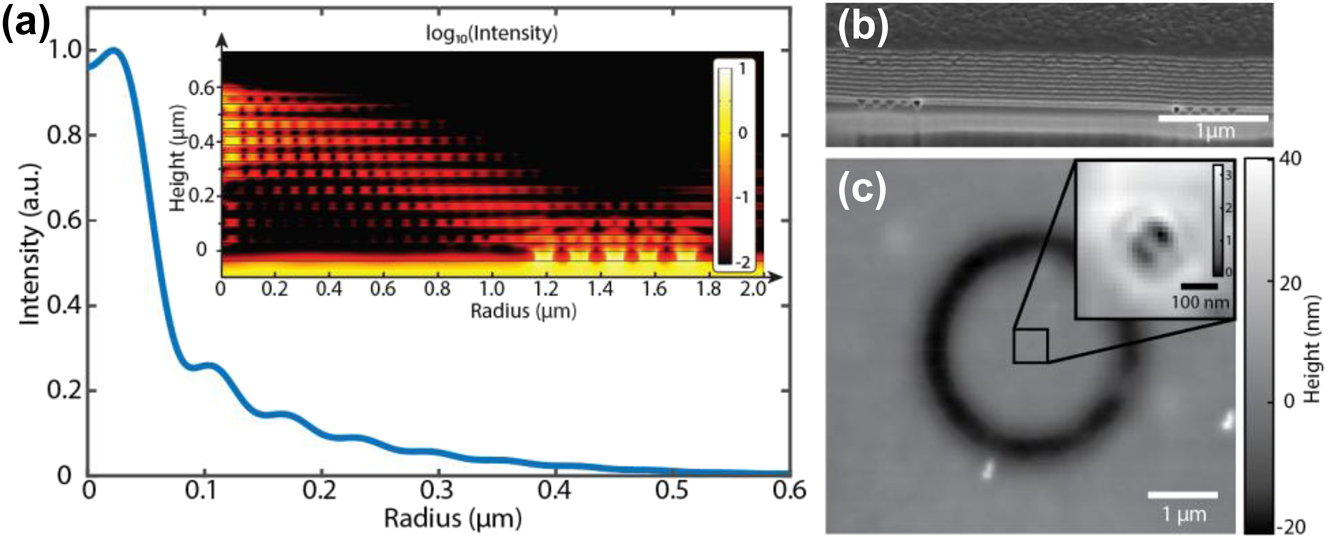

The total topological charges associated with the left-handed and right-handed circularly polarized components of the transmitted beam were measured to be 0 and –2, respectively, as shown in Figure 2c, from which it can be inferred (based on the angular momentum decomposition) that the output field contains a dominant OAM component with topological charge −1, corresponding to the expected vortex mode generated by the polarization-selective transmission through the Fresnel grating. To experimentally quantify the contribution of the radially polarized OAM beam in the transmitted field, the polarization state of the output beam was measured using the method described in [40], [41] and detailed further in the Supplementary Material, with the resulting spatial distribution of Stokes parameters shown in Figure 2d. In particular, it was determined that the radially polarized OAM component accounts for approximately 76 ± 1 % of the total transmitted intensity, while an additional 11 % of the beam appears to lose its defined polarization state after transmission through the Fresnel grating, an effect that is likely attributable to scattering-induced depolarization originating from surface roughness or fabrication imperfections (see Supplementary Material for details). Following the confirmation of OAM beam generation, the Fresnel grating was integrated onto the planar HMM to realize the complete hypergrating structure, and the subsequent propagation of light through this system was investigated both numerically and experimentally to assess the focusing behavior and field confinement enabled by the combined action of the grating and the hyperbolic medium. Figure 3a presents the numerically predicted performance of the hypergrating structure under illumination by a circularly polarized beam at a wavelength of 532 nm, where the simulated intensity distribution, evaluated 15 nm above the top surface of the HMM, reveals a tightly focused beam with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of approximately 110 nm, corresponding to about λ/5. Notably, the same hypergrating configuration is capable of focusing vortex beams carrying higher-order OAM charges with similar subdiffraction-limited resolution, outperforming what can be achieved using conventional high-numerical-aperture (NA) objective lenses (see Supplementary Material). This enhanced focusing capability originates from the propagation of high in-plane wavevector modes that are supported by the hyperbolic dispersion of the metamaterial slab, modes that cannot exist in isotropic materials such as air or immersion oil, and thus facilitate energy compression well below the free space diffraction limit. It is important to note that, due to total internal reflection at the top interface, the focused beams are not directly outcoupled into free space but instead form an evanescent field localized just above the HMM surface.

Generation and nano-focusing of OAM beam. (a) Light intensity distribution at the focus of the hypergrating (10 nm above the HMM) from numerical simulation. The inserted figure shows the light intensity distribution in HMM. Note that the intensity distribution has axial symmetry with respect to the principal axis. (b) Cross section of the hypergrating structure. (c) The surface topology of the Azo-polymer after the exposure measured by atomic force microscopy.

A cross-sectional scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the fabricated hypergrating structure is shown in Figure 3b, and further details of the fabrication procedure are provided in the Supplementary Materials. To experimentally characterize the near-field intensity distribution at the focal plane of the hypergrating, we employed an Azo-polymer film specifically designed for sensitivity to 532 nm illumination, which undergoes photoinduced isomerization between its Trans and Cis states, thereby forming nanoscale surface relief structures in response to light exposure [42]. As shown in Figure 3c, following a 5-min exposure to a 532 nm continuous-wave laser at an intensity of I inc = 216 W/cm2, the Azo-polymer revealed a distinct figure-eight-shaped surface modulation pattern located at the expected focal region of the hypergrating. This structure appears superimposed on a preexisting, donut-shaped valley approximately 20 nm deep (see Supplementary Materials) and is attributed to the interaction of the tightly focused OAM beam with the polymer surface. The relief feature at the focal point has a lateral dimension of approximately 200 nm and a peak-to-valley height of ∼3 nm, corresponding to an estimated optical spot size of λ/2.7, which, while slightly larger than the predicted λ/5, still clearly demonstrates subdiffraction focusing. It is noteworthy to mention that the surface relief pattern does not map directly onto the light intensity distribution due to the complex photomechanical response of the Azo-polymer and the presence of both transverse and longitudinal electric field components at the focal point, as discussed in prior work [43] and detailed in the Supplementary Materials. In other words, the observed figure-eight-shaped surface relief pattern is not a direct mapping of the intensity profile but rather arises from photoinduced mass migration driven by interference between the longitudinal and transverse field components near the surface, similar to mechanisms discussed in Ref. [43]. This interference becomes allowed due to symmetry breaking at the polymer–air interface and leads to surface deformations that encode the spin and phase structure of the focused field. Deviations from theoretical beam size may also arise from fabrication-induced imperfections, such as surface roughness and slight nonplanarity in the multilayer stack. We note that the ability of the hypergrating to tightly localize OAM beams holds important implications for enhancing light–matter interactions at the nanoscale. Prior theoretical studies based on multipolar expansions of electric and magnetic fields have shown that vortex beams tightly confined to subwavelength scales can give rise to new types of optical transitions in quantum emitters, particularly in quantum dots, that are otherwise forbidden for plane waves at normal incidence [14], [29]. Moreover, unlike conventional vortex beams, in which the intensity minimum near the singularity complicates alignment with atomic systems, the hypergrating enables the generation of a high-intensity focal spot, thus facilitating precise spatial overlap between the vortex field and nanoscale targets [44], [45]. We also note that the proposed framework is readily extendable to higher-order modes, offering a scalable platform for nanoscale manipulation of structured light (see Supplementary Materials).

4 Optical quasiparticles

Originally introduced by Tony Skyrme in 1961 as topologically protected quasiparticles describing solitonic structures in nucleons, skyrmions have since emerged in a variety of physical systems, including magnetic materials, liquid crystals, Bose–Einstein condensates, and, more recently, optical fields [46]. In optics, skyrmions are realized as structured vector fields characterized by nontrivial mappings of polarization or spin textures onto the unit sphere, with their topology defined by their skyrmion numbers. The hypergrating platform we developed for subdiffraction focusing of OAM beams inherently produces a tightly confined and spatially structured electromagnetic field at the focal region, where strong spin–orbit coupling coexist.

As a result, the same structure can serve not only as a tool for deep-subwavelength beam compression but also as a compact and planar source of optical skyrmions, enabling experimental access to topologically nontrivial light fields that hold potential for applications in nanoscale imaging, ultrafast vectorial field mapping, and topological photonic information processing [46]. To demonstrate the capability of the proposed hypergrating in generating optical skyrmions, we performed a parametric study by varying the radius of the Fresnel grating from 800 nm to 1,040 nm and evaluated the resulting electric and magnetic field distributions at a plane located 15 nm above the HMM surface (i.e., approximately 615 nm from the source plane), where the focal region forms and the vectorial field structure becomes strongly pronounced. We analyzed the vectorial spin texture formed in the focal region by computing the spin angular momentum density, defined as

where the integration is carried out over the region confining the topological quasiparticle. Upon evaluating this integral across different textures, we find that the skyrmion number decreases gradually by approximately 0.02 between successive configurations, suggesting structural similarities among the spin fields; however, this smooth variation does not imply topological equivalence, as even small deviations in the skyrmion number reflect nontrivial changes in the vector field topology.

Analysis of spin-vector distribution in the vicinity of focal spot. (a) Normalized spin vector fields σ plotted at 15 nm above the HMM surface for various Fresnel grating radii, showing the evolution of spin textures as the radius increases from 860 nm to 1,040 nm. Hedgehog-like textures characteristic of Néel-type skyrmions are observed at r = 860 nm (dashed blue line), while more complex and nontopological textures emerge for larger radii. The skyrmion number N

sk

is computed for each configuration, showing a quantized value of N

sk

= 1 for the 860 nm case and a gradual decrease (∼0.02 per step) for larger radii. (b) Top row: cross-sectional profiles of the spin vector σ for N

sk

= 1, illustrating the radial spin reversal near the beam center and a second reversal in the outer domain. Bottom rows: local spin structure parameter

Most notably, for the specific case of r = 860 nm, the skyrmion number is found to be exactly N

sk

= 1, which unambiguously confirms the presence of a topologically protected Néel-type skyrmion, characterized by its hedgehog-like spin texture. This discrete quantization at unity serves as a clear topological marker that distinguishes this configuration from neighboring cases, whose skyrmion numbers deviate from integer values and, therefore, do not correspond to classical skyrmionic quasiparticles. For the specific case corresponding to the Néel-type skyrmion at r = 860 nm, where the skyrmion number is quantized at N

sk

= 1, the spin vector exhibits a distinct and continuous reversal from the “up” to the “down” state along the radial direction, as shown in the top row of Figure 4b, illustrating the hedgehog-like spin topology associated with this configuration. To demonstrate that the reversal of the spin vector within the domains occurs at deep subwavelength scales, we introduce a spin-related contrast parameter

5 Conclusions

In summary, we proposed and experimentally demonstrated a planar hypergrating platform capable of sub-diffraction focusing of vortex beams and supporting the formation of optical skyrmions. Numerical simulations predict that the radially polarized OAM beam can be focused down to λ/5 due to the excitation of high in-plane wavevector modes within the hyperbolic metamaterial, achieving spatial confinement far beyond that of high-NA objective lenses. The spin texture at the focal plane reveals deep-subwavelength topological structure, with spin-flip transitions occurring over distances as small as λ/250, consistent with the emergence of a Néel-type optical skyrmion. Experimental realization of the hypergrating confirms beam compression to approximately λ/3, validating the strong focusing capability of the platform. Beyond enhanced field confinement, the demonstrated system provides a compact and versatile route toward topological field engineering and offers new opportunities for controlling light–matter interactions at the nanoscale, particularly in the context of chiral quantum systems and OAM-based photonic applications.

Funding source: Army Research Office

Award Identifier / Grant number: W911NF2310057

Funding source: National Science Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: DMR 2004298

Acknowledgment

NML would like to acknowledge the support of this research by the Army Research Office Award no. W911NF2310057. VAP would like to acknowledge the support of this research by the National Science Foundation, Division of Materials Research Award no. DMR 2004298. TO would like to acknowledge the financial support by JSPS KAKENHI Grants-in-Aid (Grant Nos. JP22H05131, JP22H05138, JP23H00270) and JST-CREST (Grant No. JPMJCR1903).

-

Research funding: Army Research Office Award no. W911NF2310057; National Science Foundation, Division of Materials Research Award no. DMR 2004298. JSPS KAKENHI Grants-in-Aid (Grant Nos. JP22H05131, JP22H05138, JP23H00270); JST-CREST (Grant No. JPMJCR1903).

-

Author contributions: NML, WL, and VP initiated the idea of this study. JL, ES, and VP conducted theoretical and numerical studies of the meta-grating and Fresnel Lens. TO performed the Azo polymer characterization of the demagnified beam. The samples were fabricated by WL, AC, JD, and JF. JT and HBS conducted theoretical and numerical studies of optical skyrmions. All authors contributed to the design and discussions. NML supervised the study performed in this work. All authors collectively contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Research ethics: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

-

Data availability: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

[1] M. J. Padgett, “Orbital angular momentum 25 years on,” Opt. Express, vol. 25, no. 10, pp. 11265–11274, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.25.011265.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] S. Franke-Arnold, L. Allen, and M. Padgett, “Advances in optical angular momentum,” Laser Photon. Rev., vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 299–313, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.200810007.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] K. Y. Bliokh, F. J. Rodríguez-Fortuño, F. Nori, and A. V. Zayats, “Spin-orbit interactions of light,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 796–808, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2015.201.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] C. T. Schmiegelow, J. Schulz, H. Kaufmann, T. Ruster, U. G. Poschinger, and F. Schmidt-Kaler, “Transfer of optical orbital angular momentum to a bound electron,” Nat. Commun., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 12998, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12998.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] R. Fickler, R. Lapkiewicz, M. Huber, M. P. Lavery, M. J. Padgett, and A. Zeilinger, “Interface between path and orbital angular momentum entanglement for high-dimensional photonic quantum information,” Nat. Commun., vol. 5, no. 1, p. 4502, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5502.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] J. E. Curtis and D. G. Grier, “Modulated optical vortices,” Opt. Lett., vol. 28, no. 11, pp. 872–874, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.28.000872.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] M. Mirhosseini, et al.., “High-dimensional quantum cryptography with twisted light,” New J. Phys., vol. 17, no. 3, p. 033033, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/17/3/033033.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] A. Nicolas, L. Veissier, L. Giner, E. Giacobino, D. Maxein, and J. Laurat, “A quantum memory for orbital angular momentum photonic qubits,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 234–238, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.355.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] P. Miao, et al.., “Orbital angular momentum microlaser,” Science, vol. 353, no. 6298, pp. 464–467, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8533.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Z. Zhang, et al.., “Tunable topological charge vortex microlaser,” Science, vol. 368, no. 6492, pp. 760–763, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba8996.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Z. Zhang, et al.., “Spin–orbit microlaser emitting in a four-dimensional Hilbert space,” Nature, vol. 612, no. 7939, pp. 246–251, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05339-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] H. Zhao, et al.., “High-purity generation and switching of twisted single photons,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 131, no. 18, p. 183801, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.131.183801.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] H. Zhao, et al.., “Integrated preparation and manipulation of high-dimensional flying structured photons,” eLight, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 10, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1186/s43593-024-00066-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] G. F. Quinteiro and T. Kuhn, “Light-hole transitions in quantum dots: Realizing full control by highly focused optical-vortex beams,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 90, no. 11, p. 115401, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.90.115401.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] N. Rivera, I. Kaminer, B. Zhen, J. D. Joannopoulos, and M. Soljačić, “Shrinking light to allow forbidden transitions on the atomic scale,” Science, vol. 353, no. 6296, pp. 263–269, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf6308.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] X. Fang, H. Ren, and M. Gu, “Orbital angular momentum holography for high-security encryption,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 102, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-019-0560-x.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] C. He, Y. Shen, and A. Forbes, “Towards higher-dimensional structured light,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 11, no. 1, p. 205, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-022-00897-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] V. E. Lembessis and M. Babiker, “Enhanced quadrupole effects for atoms in optical vortices,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 110, no. 8, p. 083002, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.110.083002.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] A. Afanasev, C. E. Carlson, and A. Mukherjee, “High-multipole excitations of hydrogen-like atoms by twisted photons near a phase singularity,” J. Optics, vol. 18, no. 7, p. 074013, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8978/18/7/074013.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] M. Mahdavi, Z. A. Sabegh, M. Mohammadi, M. Mahmoudi, and H. R. Hamedi, “Manipulation and exchange of light with orbital angular momentum in quantum-dot molecules,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 101, no. 6, p. 063811, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.101.063811.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] R. W. Heeres and V. Zwiller, “Subwavelength focusing of light with orbital angular momentum,” Nano Lett., vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 4598–4601, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1021/nl501647t.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Y. Liang, et al.., “Bound states in the continuum in anisotropic plasmonic metasurfaces,” Nano Lett., vol. 20, no. 9, pp. 6351–6356, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c01752.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Y. Tang, et al.., “Chiral bound states in the continuum in plasmonic metasurfaces,” Laser Photon. Rev., vol. 17, no. 4, p. 2200597, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202200597.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] S. Hu, Z. Guo, W. Liu, S. Chen, and H. Chen, “Hyperbolic metamaterial empowered controllable photonic Weyl nodal line semimetals,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 2773, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47125-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Z. Guo, et al.., “Exceptional point empowered near-field routing of hyperbolic polaritons,” Sci. Bull., vol. 69, no. 22, pp. 3491–3495, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2024.09.027.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Z. Ji, et al.., “Photocurrent detection of the orbital angular momentum of light,” Science, vol. 368, no. 6492, pp. 763–767, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9192.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] G. F. Quinteiro and J. Berakdar, “Electric currents induced by twisted light in Quantum Rings,” Opt. Express, vol. 17, no. 22, pp. 20465–20475, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.17.020465.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] O. Reinhardt and I. Kaminer, “Theory of shaping electron wavepackets with light,” Acs Photonics, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 2859–2870, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.0c01133.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] G. F. Quinteiro, D. E. Reiter, and T. Kuhn, “Formulation of the twisted-light-matter interaction at the phase singularity: Beams with strong magnetic fields,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 95, no. 1, p. 012106, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.95.012106.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] H. B. Sedeh, et al.., “Manipulation of scattering spectra with topology of light and matter,” Laser Photon. Rev., vol. 17, no. 3, p. 2200472, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202200472.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] C. T. Schmiegelow and F. Schmidt-Kaler, “Light with orbital angular momentum interacting with trapped ions,” Eur. Phys. J. D, vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 1–9, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjd/e2012-20730-4.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] S. Thongrattanasiri and V. A. Podolskiy, “Hypergratings: nanophotonics in planar anisotropic metamaterials,” Opt. Lett., vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 890–892, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.34.000890.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] L. Rao, J. Pu, Z. Chen, and P. Yei, “Focus shaping of cylindrically polarized vortex beams by a high numerical-aperture lens,” Opt. Laser Technol., vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 241–246, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2008.06.012.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] C. L. Cortes, W. Newman, S. Molesky, and Z. Jacob, “Quantum nanophotonics using hyperbolic metamaterials,” J. Optics, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 063001, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8978/14/6/063001.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] A. Poddubny, I. Iorsh, P. Belov, and Y. Kivshar, “Hyperbolic metamaterials,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 948–957, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.243.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] J. Elser, V. A. Podolskiy, I. Salakhutdinov, and I. Avrutsky, “Nonlocal effects in effective-medium response of nanolayered metamaterials,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 90, no. 19, p. 191109, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2737935.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] I. Avrutsky, “Guided modes in a uniaxial multilayer,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, Optics, Image Sci. Vis., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 548–556, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1364/josaa.20.000548.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Q. Zhan, “Cylindrical vector beams: from mathematical concepts to applications,” Adv. Optics Photon., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–57, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1364/aop.1.000001.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Y. Liu, L. Zhou, Y. Wen, Y. Shen, J. Sun, and J. Zhou, “Optical vector vortex generation by spherulites with cylindrical anisotropy,” Nano Lett., vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 2444–2449, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c00171.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] K. Singh, N. Tabebordbar, A. Forbes, and A. Dudley, “Digital Stokes polarimetry and its application to structured light: Tutorial,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, Optics, Image Sci. Vis., vol. 37, no. 11, pp. C33–C44, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1364/josaa.397912.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] S. Chen, X. Zhou, Y. Liu, X. Ling, H. Luo, and S. Wen, “Generation of arbitrary cylindrical vector beams on the higher order Poincaré sphere,” Opt. Lett., vol. 39, no. 18, pp. 5274–5276, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.39.005274.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] K. Masuda, S. Nakano, D. Barada, M. Kumakura, K. Miyamoto, and T. Omatsu, “Azo-polymer film twisted to form a helical surface relief by illumination with a circularly polarized Gaussian beam,” Opt. Express, vol. 25, no. 11, pp. 12499–12507, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.25.012499.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] A. Ambrosio, L. Marrucci, F. Borbone, A. Roviello, and P. Maddalena, “Light-induced spiral mass transport in azo-polymer films under vortex-beam illumination,” Nat. Commun., vol. 3, no. 1, p. 989, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1996.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] B. S. Davis, L. Kaplan, and J. H. McGuire, “On the exchange of orbital angular momentum between twisted photons and atomic electrons,” J. Optics, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 035403, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8978/15/3/035403.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] A. M. Konzelmann, S. O. Krüger, and H. Giessen, “Interaction of orbital angular momentum light with Rydberg excitons: Modifying dipole selection rules,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 100, no. 11, p. 115308, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.100.115308.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Y. Shen, Q. Zhang, P. Shi, L. Du, X. Yuan, and A. V. Zayats, “Optical skyrmions and other topological quasiparticles of light,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 15–25, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-023-01325-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] L. Du, A. Yang, A. V. Zayats, and X. Yuan, “Deep-subwavelength features of photonic skyrmions in a confined electromagnetic field with orbital angular momentum,” Nat. Phys., vol. 15, no. 7, p. 650, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-019-0487-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] X. Yin, P. Shi, L. Du, and X. Yuan, “Spin-resolved near-field scanning optical microscopy for mapping of the spin angular momentum distribution of focused beams,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 116, no. 24, p. 1107, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0004750.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2025-0315).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial on special issue “The 11th International Conference on Surface Plasmon Photonics (SPP11)”

- Review

- Beyond limits: a tribute to Dai-Sik Kim’s academic legacy and vision

- Letters

- Meso-chiral optical properties of plasmonic nanoparticles: uncovering hidden chirality

- Modulation of the type and excitation region of plasmonic topological quasiparticles in a metasurface by tailoring the excitation light

- Research Articles

- Nonlocal electrodynamics of two-dimensional anisotropic magnetoplasmons

- Goos–Hänchen effect singularities in transdimensional plasmonic films

- Nature inspired design methodology for a wide field of view achromatic metalens

- Vortex beam nanofocusing and optical skyrmion generation via hyperbolic metamaterials

- Strong coupling of double resonance designs and epsilon-near-zero modes for mode-matching enhancement of second-harmonic generation

- Super-resolution imaging of resonance modes in semiconductor nanowires by detecting photothermal nonlinear scattering

- Cross-polarized and stable second harmonic generation from monocrystalline copper

- Dual-state six-channel polarization multiplexing in reconfigurable metasurfaces

- Metasurface-based Fourier ptychographic microscopy

- Dual-band spectral filter array integrated with a telecentric lens for real-time surface plasmon resonance sensing and imaging

- Visualization of plasmonic diffraction-guided carrier dynamics in silicon photodetectors

- Directional enhancement of photoluminescence from phosphor plates with TiO2 nanoantenna stickers

- Charge reservoir as a design concept for plasmonic antennas

- Cavity-mediated coupling between local and nonlocal modes in Landau polaritons

- Polarization-encoded color images for information encryption enabled by HfN refractory plasmonic metasurfaces

- Wavelength- and angle-multiplexed full-color 3D metasurface hologram

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial on special issue “The 11th International Conference on Surface Plasmon Photonics (SPP11)”

- Review

- Beyond limits: a tribute to Dai-Sik Kim’s academic legacy and vision

- Letters

- Meso-chiral optical properties of plasmonic nanoparticles: uncovering hidden chirality

- Modulation of the type and excitation region of plasmonic topological quasiparticles in a metasurface by tailoring the excitation light

- Research Articles

- Nonlocal electrodynamics of two-dimensional anisotropic magnetoplasmons

- Goos–Hänchen effect singularities in transdimensional plasmonic films

- Nature inspired design methodology for a wide field of view achromatic metalens

- Vortex beam nanofocusing and optical skyrmion generation via hyperbolic metamaterials

- Strong coupling of double resonance designs and epsilon-near-zero modes for mode-matching enhancement of second-harmonic generation

- Super-resolution imaging of resonance modes in semiconductor nanowires by detecting photothermal nonlinear scattering

- Cross-polarized and stable second harmonic generation from monocrystalline copper

- Dual-state six-channel polarization multiplexing in reconfigurable metasurfaces

- Metasurface-based Fourier ptychographic microscopy

- Dual-band spectral filter array integrated with a telecentric lens for real-time surface plasmon resonance sensing and imaging

- Visualization of plasmonic diffraction-guided carrier dynamics in silicon photodetectors

- Directional enhancement of photoluminescence from phosphor plates with TiO2 nanoantenna stickers

- Charge reservoir as a design concept for plasmonic antennas

- Cavity-mediated coupling between local and nonlocal modes in Landau polaritons

- Polarization-encoded color images for information encryption enabled by HfN refractory plasmonic metasurfaces

- Wavelength- and angle-multiplexed full-color 3D metasurface hologram