Abstract

Joint space-time modulation of light fields has recently garnered intense attention for enabling precise control over both spatial and temporal characteristics of light, leading to the creation of space-time beams with unique properties, such as diffraction-free propagation and transverse orbital angular momentum. Here, we theoretically propose and experimentally demonstrate spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields by controlling the discrete rotational symmetry of a pulse’s spatiotemporal spectrum. Using a 4f pulse shaper and an x − ω modulation strategy, we generate tunable spatiotemporal Moiré patterns with varying sublattice sizes and confirm their diffraction-free behavior in time-averaged intensities. Additionally, we demonstrate spatiotemporal Moiré lattices carrying transverse orbital angular momentum. These findings provide a novel platform for studying spatiotemporal light–matter interactions and may open new possibilities for applications in other wave-based systems, such as acoustics and electron waves.

1 Introduction

Light field manipulation – the exact regulation of light’s properties – has become a fundamental aspect of modern optics. Traditionally, the spatial and temporal modulation of light fields have been treated as relatively independent processes: spatial control addressed parameters such as propagation direction, phase, and amplitude, while temporal control focused on pulse duration and frequency (or wavelength) [1], [2]. Nevertheless, recent advances have highlighted the advantages of simultaneously modulating light in both space and time, rooted in the inherent duality of these dimensions in Maxwell’s equations [3]. This joint space-time modulation has naturally led to the extension of spatially structured light into the space-time domain, resulting in space-time beams with unconventional and unique physical properties. Notable examples include spatiotemporal optical vortices carrying transverse orbital angular momentum [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11] and space-time light sheets with arbitrary group velocities [12], [13], [14], [15]. These breakthroughs open new frontiers for applications involving space-time beams, including laser processing [16], complex light–matter interactions [17], and optical communications [18].

The Moiré effect, characterized by interference patterns resulting from the superposition of two similar but distinct periodic structures, was utilized for high-precision displacement and angular measurements due to the low-frequency fringes it produces [19]. Recently, this phenomenon has garnered significant attention across various physical systems due to its connection with extremely flat spectral bands, which are characterized by minimal energy dispersion and provide an ideal platform for exploring exotic quantum states [20], [21], [22], [23]. Although Moiré patterns are conventionally observed in real space by overlapping crystalline structures at different initial angles, their complexity simplifies when viewed in momentum space. For instance, a hexagonal Moiré lattice can be understood as the superposition of two spectra, each with six-fold discrete rotational symmetry and a specific angular offset. This concept enables the generation of spatially structured light fields that exhibit crystal and Moiré lattice, characterized by diffraction-free properties and high tunability [24], [25]. However, given the distinct characteristics of space-time beams compared to conventional spatially structured light, the potential to generate spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields through joint space-time modulation remains an intriguing question.

Here, we theoretically propose and experimentally demonstrate the generation of spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields. We show that these fields can theoretically be achieved by controlling the discrete rotational symmetry of the pulse’s spatiotemporal spectrum. Based on this principle, we experimentally generate and characterize spatiotemporal Moiré lattice beams with different sublattice sizes using a custom 4f pulse shaper [2] and our previously proposed x − ω space-time modulation strategy [7]. We also show the impact of the angular offset in the spatiotemporal spectra on the resulting spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields. Furthermore, we demonstrate that these light fields exhibit diffraction-free behaviour in their time-integrated intensities. Finally, we generate spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields that carry transverse orbital angular momentum, by introducing extra phase modulation into their spatiotemporal spectra. Our results provide a pathway for studying the Moiré effect in the space-time domain and could be extended to other wave-based physical systems, such as acoustic and electron wave.

2 Results

Similar to the spatial Moiré light fields [25], the spectra of spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields can be theoretically expressed as:

Here, k

x

is the spatial frequency,

The experimental setup for generating spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields is illustrated in Figure 1(a). Femtosecond pulses from a Ti:sapphire laser, centred at a wavelength of ∼800 nm, are tailored using a custom 4f pulse shaper with a 2D phase-only spatial light modulator (SLM, PLUTO-2.1-NIR-133, Holoeye). The beam is then analysed using a Mach–Zehnder interferometer. The optical frequencies ω (or the wavelengths λ) of the reshaped beam are collimated along the horizontal y-axis using a diffraction grating (1,800 lines/mm, GH25-18V, Thorlabs) and a cylindrical lens (L

y

, f = 100 mm). The phase patterns loaded into the SLM (shown in Figure 1(a)) are calculated via Eq. (1), assigning a specific ω (or λ) to each spatial frequency

Experimental setup and generation of spatiotemporal crystal lattice light fields. (a) Experimental setup consists of three sections: (1) the space-time beam generator comprising of a grating, a cylindrical lens L y and a spatial light modulator (SLM); (2) the spatiotemporal Fourier spectra analyser, which includes a cylindrical lens L x and a CCD camera (CCD1); and (3) the time-resolved profile measurement section, realized via a Mach–Zehnder interferometer consisting of two BSs (BS1 and BS3), a 4f system including two cylindrical lenses L x2 (f = 400 mm) and L x3 (f = 200 mm), a CCD camera (CCD2) placed on the back focal plane of L x3, and a motorized translation stage in the reference path. Two SLM phase patterns for different N-fold discrete rotational symmetry modulation (N = 4, 6) are loaded. (b) The simplified graph on the top of the column reflects such structure more vividly, with black grid lines representing the structure of the spatiotemporal lattice and red lines highlighting a single lattice cell. The measured spectrum and intensity distribution for the space-time beam with four-fold discrete rotational symmetry (the initial angle is set to 22.5°) are shown, with good agreement between the experiment (Exp.) and simulation (Simu.). (c) Similar to (b) but for N = 6, with the initial angle set to 52.5°.

To measure the spatiotemporal spectra

We first generate two spatiotemporal crystal lattice light fields with four-fold (N = 4) and six-fold (N = 6) discrete rotational symmetry. The measured spatiotemporal spectra

Next, we generate spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields as described by Eq. (1). Figure 2(a)–(d) present the simulated and measured results for Moiré lattice light fields via superimposing two sets of spatiotemporal crystal lattices with four-fold discrete rotational symmetry. Notably, we fix the initial angle of one set’s spatiotemporal spectra

Generation and characterization of spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields. (a)–(d) Spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields by superimposing two spatiotemporal lattice fields with four-fold discrete rotational symmetry (N = 4). The top row illustrates the simplified lattice structures, with black grid lines representing the structure of one lattice and red lines for the other. The second row shows the measured spatiotemporal spectra, where the initial angle of one spectrum (white dashed circles) is fixed at 60°, and the shift angles of the second spectrum (red dashed circles) are set to 10°, 20°, 30°, and 45°. The third and fourth rows display the calculated and measured time-resolved light field distributions, respectively, where the yellow double arrows denote the sublattice orientation and size. (e)–(h) Similar to (a)–(d) but for N = 6, with the initial angle set to 15° and the shift angles are 5°, 15°, 25° and 30°, respectively.

We also synthesize spatiotemporal Moiré-like lattices by superimposing two spatiotemporal crystal lattice light fields, both with six-fold discrete rotational symmetry (N = 6) but varying lattice constants (or different spectral widths), while maintaining a constant shift angle of

Generation and characterization of spatiotemporal Moiré-like lattices with varying spectral width ratios. (a)–(d) The simplified diagrams at the top illustrate the Moiré-like structures generated by superimposing two spatiotemporal crystal lattice light fields with six-fold discrete rotational symmetry, but differing lattice constants. The second row shows the measured spatiotemporal spectra, where the initial angle is set to 15°, and the rotation angle between the two lattices is fixed at 5°. The spectral width ratios of the second crystal lattice to the first are r = 0.85, 0.90, 1.10, and 1.15, respectively, and two sets of spectra are indicated by the red and black dashed circles. The third and fourth rows present the calculated and measured intensity distributions of the spatiotemporal Moiré-like lattices, where the yellow curve arrows represent the twist directions.

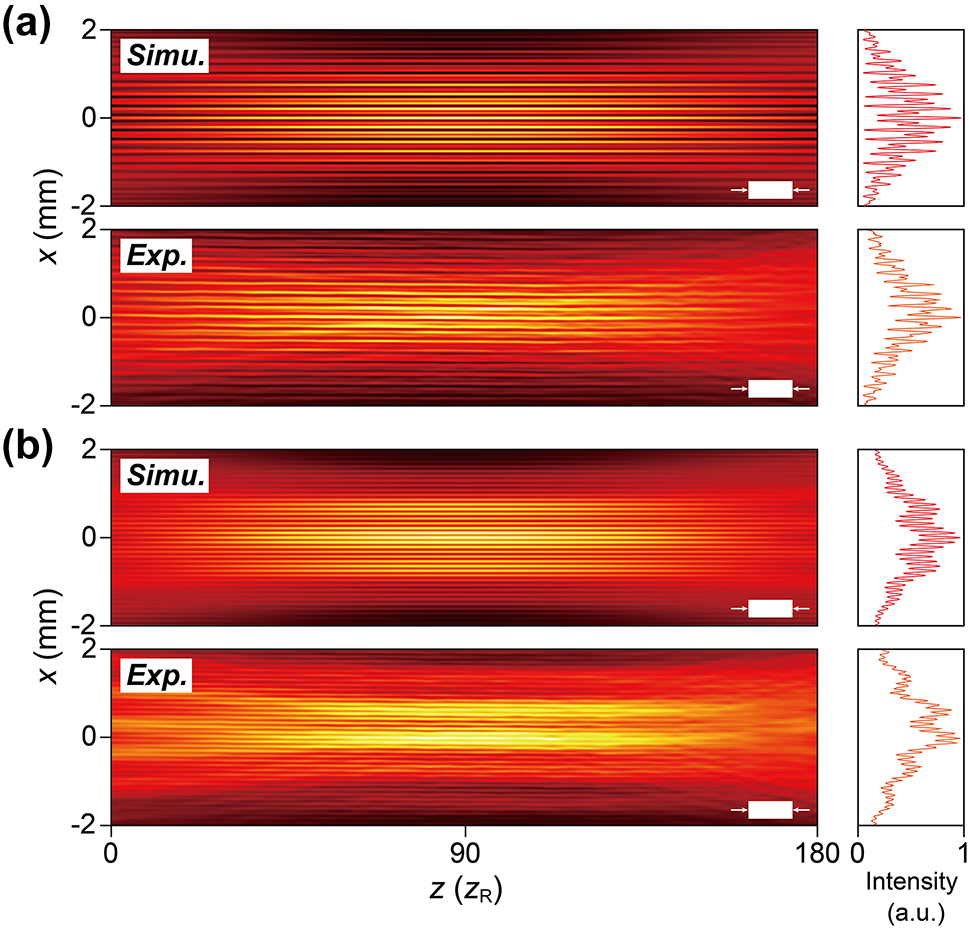

Notably, the time-averaged profile of spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields,

where

Diffraction-free propagation of spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields. (a) Simulated and experimental propagation of spatiotemporal Moiré lattices with four-fold discrete rotational symmetry (N = 4) and a shift angle of 30°. The propagation distance is up to ∼180 times the Rayleigh distance (z R) of a Gaussian beam with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of ∼33 μm. The solid white blocks in the bottom-right corners represent 50 mm. On the right, the cross-sectional intensity profiles along the x-axis at z = 90z R are shown. (b) Similar to (a) but for N = 6 with the shift angle of 15°.

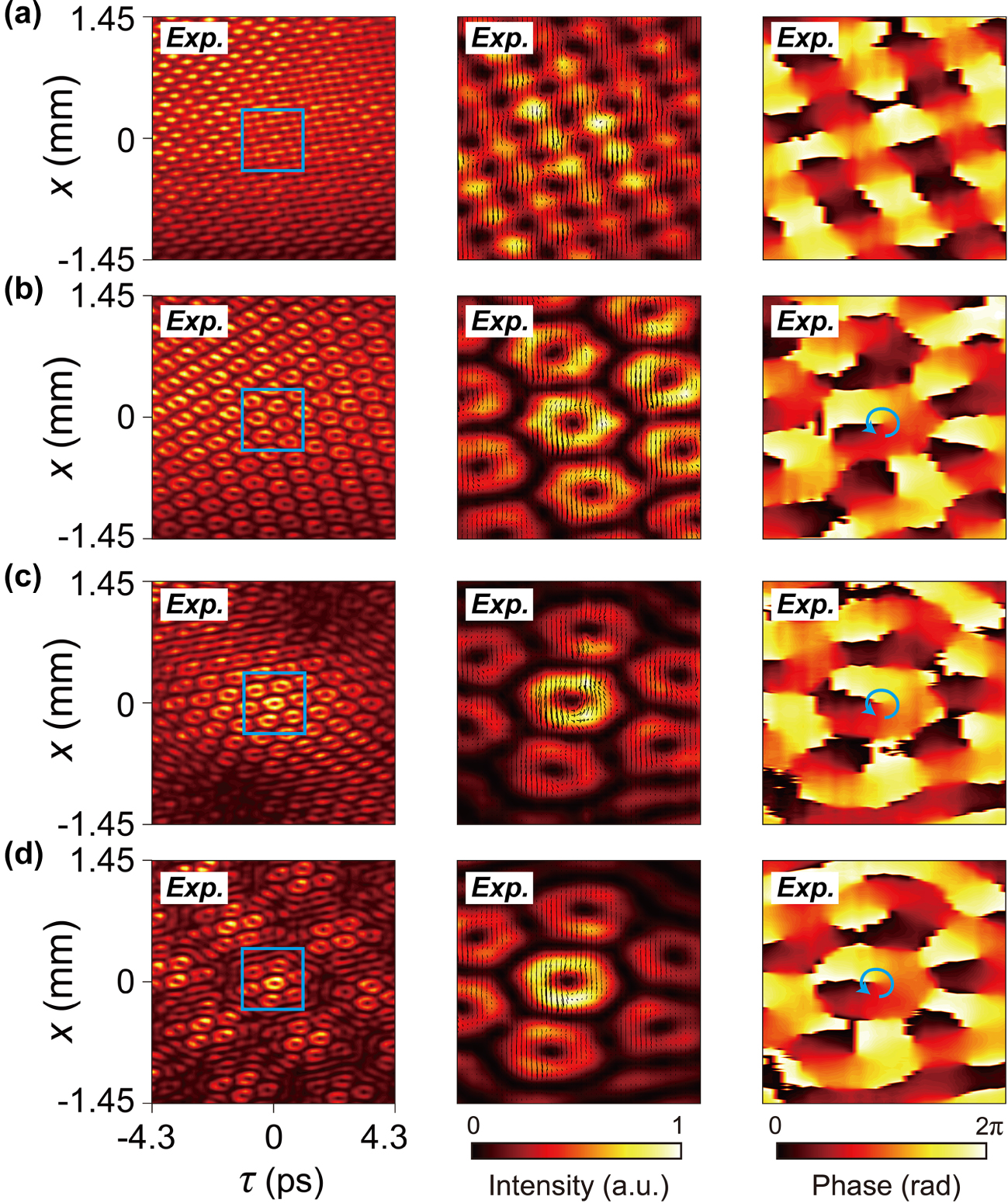

So far, the results we have presented are based on spatiotemporal spectra where all frequency components share the same phase. By modulating the momentum space (or spatiotemporal spectra), we can obtain more complex spatiotemporal lattice light fields by adjusting the relative phases of different frequency components. A typical example is introducing a spiral phase with a topological charge ℓ = 1, eiφ

(where

Phase modulation in spatiotemporal crystal and Moiré lattice light fields. (a)–(d) The four rows correspond to N = 4 and 6 spatiotemporal crystals, and spatiotemporal Moiré lattices with shift angles of 5° and 15°, respectively. The left column shows the experimentally measured intensity distributions of the space-time beams. The regions inside the blue boxes are magnified and displayed in the second column, showing the measured intensity distributions with calculated Poynting vectors indicated by the black arrows. The right column presents the measured phase distributions, where the blue arrows indicate the direction of phase increase, confirming the formation of spatiotemporal vortex arrays with a topological charge of ℓ = 1.

3 Conclusions

In conclusion, we theoretically describe and experimentally generate spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields. We demonstrate that these fields are constructed by superimposing two sets of spatiotemporal spectra with discrete rotational symmetry and a specific shift angle. Our results show that the shift angle is inversely proportional to the size of the sublattices in the spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields. Additionally, we demonstrate that the ratio of the spectral widths of the two original spatiotemporal spectra provides an extra degree of freedom for tailoring the distribution of these Moiré lattices. Furthermore, by modulating the phase of the spatiotemporal spectra, we introduce even greater complexity, such as generating spatiotemporal vortex arrays that carry transverse orbital angular momentum.

Future research could explore the interaction between these space-time beams and artificial microstructures, such as nonlinear optical superlattices [28], [29] and liquid crystals [30], [31]. By combining the control of symmetry in spatiotemporal spectra with complex amplitude modulation strategies, a broader range of novel spatiotemporal beams may be uncovered [32], [33]. While our experimental setup is effective and easy to operate, more compact or even on-chip schemes are potentially developed, particularly using metasurfaces that simultaneously control spatial and temporal frequencies [34], [35], [36]. To date, the regulation of frequency symmetry to generate Moiré structures is not yet widely utilized for space-time beam manipulation, and our work highlights the versatility of this method as an efficient platform for controlling the spatiotemporal dynamics of pulsed light fields. Finally, we believe this scheme applies to other wave systems, such as acoustic [37], [38], water waves [39], and even electron waves [40], opening new avenues for the study and application of these beams across a wide range of fields.

Funding source: Basic Research Program of Jiangsu Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: BK20232040

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: BK20241191

Funding source: National Key Research and Development Program of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2022YFA1405000

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 62305157

Award Identifier / Grant number: T2488302

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, Major Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: BK20243067

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1405000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (T2488302, 62305157), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, Major Project (BK20243067), Basic Research Program of Jiangsu Province (BK20232040), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20241191).

-

Author contribution: AZY and WZ contributed equally to this work. WZ and WC proposed the original idea and developed the theoretical and experimental framework for this work. AZY, WZ, WC, YL, CQM, and JCY carried out the measurements. YQL, WC and YL guided the data analysis and supervised the project. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

-

Data availability: Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but could be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

[1] N. Yu, et al.., “Light propagation with phase discontinuities: generalized laws of reflection and refraction,” Science, vol. 334, no. 6054, pp. 333–337, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1210713.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] A. M. Weiner, “Femtosecond pulse shaping using spatial light modulators,” Rev. Sci. Instrum., vol. 71, no. 5, pp. 1929–1960, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1150614.Search in Google Scholar

[3] G. Patera, D. B. Horoshko, and M. I. Kolobov, “Space-time duality and quantum temporal imaging,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 98, no. 5, p. 053815, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.98.053815.Search in Google Scholar

[4] S. W. Hancock, S. Zahedpour, A. Goffin, and H. M. Milchberg, “Free-space propagation of spatiotemporal optical vortices,” Optica, vol. 6, no. 12, pp. 1547–1553, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.6.001547.Search in Google Scholar

[5] A. Chong, C. Wan, J. Chen, and Q. Zhan, “Generation of spatiotemporal optical vortices with controllable transverse orbital angular momentum,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 350–354, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-020-0587-z.Search in Google Scholar

[6] K. Y. Bliokh, “Spatiotemporal vortex pulses: angular momenta and spin-orbit interaction,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 126, no. 24, p. 243601, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.243601.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] W. Chen, W. Zhang, Y. Liu, F.-C. Meng, J. M. Dudley, and Y.-Q. Lu, “Time diffraction-free transverse orbital angular momentum beams,” Nat. Commun., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 4021, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31623-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] C. Wan, Q. Cao, J. Chen, A. Chong, and Q. Zhan, “Toroidal vortices of light,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 519–522, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-022-01013-y.Search in Google Scholar

[9] S. Huang, et al.., “Spatiotemporal vortex strings,” Sci. Adv., vol. 10, no. 19, p. eadn6206, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adn6206.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] W. Chen, et al.., “Observation of chiral symmetry breaking in toroidal vortices of light,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 132, no. 15, p. 153801, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.132.153801.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] X. Liu, Q. Cao, N. Zhang, A. Chong, Y. Cai, and Q. Zhan, “Spatiotemporal optical vortices with controllable radial and azimuthal quantum numbers,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 5435, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49819-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] H. E. Kondakci and A. F. Abouraddy, “Diffraction-free space–time light sheets,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 733–740, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-017-0028-9.Search in Google Scholar

[13] H. E. Kondakci and A. F. Abouraddy, “Optical space-time wave packets having arbitrary group velocities in free space,” Nat. Commun., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 929, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08735-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] M. Yessenov and A. F. Abouraddy, “Accelerating and decelerating space-time optical wave packets in free space,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 125, no. 23, p. 233901, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.233901.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] M. Yessenov, L. A. Hall, K. L. Schepler, and A. F. Abouraddy, “Space-time wave packets,” Adv. Opt. Photonics, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 455–570, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1364/AOP.450016.Search in Google Scholar

[16] M. Duocastella and C. B. Arnold, “Bessel and annular beams for materials processing,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 607–621, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201100031.Search in Google Scholar

[17] K. A. Sitnik, et al.., “Spontaneous Formation of time-periodic vortex cluster in nonlinear fluids of light,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 128, no. 23, p. 237402, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.237402.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] J. Wang, “Advances in communications using optical vortices,” Photonics Res., vol. 4, no. 5, pp. B14–B28, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.4.000B14.Search in Google Scholar

[19] O. Kafri and I. Glatt, The Physics of Moire Metrology, New York, Wiley, 1990.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Y. Cao, et al.., “Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices,” Nature, vol. 556, no. 7699, pp. 43–50, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature26160.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Y. Cao, et al.., “Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices,” Nature, vol. 556, no. 7699, pp. 80–84, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature26154.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] T. Li, et al.., “Quantum anomalous Hall effect from intertwined moiré bands,” Nature, vol. 600, no. 7890, pp. 641–646, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04171-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Y. Xu, et al.., “Correlated insulating states at fractional fillings of moiré superlattices,” Nature, vol. 587, no. 7833, pp. 214–218, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2868-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] M. Kumar and J. Joseph, “Generating a hexagonal lattice wave field with a gradient basis structure,” Opt. Lett., vol. 39, no. 8, pp. 2459–2462, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.39.002459.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] C. Shang, C. Lu, S. Tang, Y. Gao, and Z. Wen, “Generation of gradient photonic moiré lattice fields,” Opt. Express, vol. 29, no. 18, pp. 29116–29127, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.434935.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] J. Patera, Quasicrystals and Discrete Geometry, USA, American Mathematical Soc, 1998.10.1090/fim/010Search in Google Scholar

[27] K. Y. Bliokh, A. Y. Bekshaev, and F. Nori, “Optical momentum, spin, and angular momentum in dispersive media,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 119, no. 7, p. 073901, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.073901.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] N. V. Bloch, K. Shemer, A. Shapira, R. Shiloh, I. Juwiler, and A. Arie, “Twisting light by nonlinear photonic crystals,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 108, no. 23, p. 233902, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.233902.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Y. Liu, et al.., “Nonlinear conformal transformation for in situ IR-visible detection of orbital angular momentum,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 17, no. 4, p. 2200656, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202200656.Search in Google Scholar

[30] P. Chen, B.-Y. Wei, W. Hu, and Y.-Q. Lu, “Liquid-crystal-mediated geometric phase: from transmissive to broadband reflective planar optics,” Adv. Mater., vol. 32, no. 27, p. 1903665, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201903665.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] J.-T. Pan, et al.., “Nonlinear geometric phase coded ferroelectric nematic fluids for nonlinear soft-matter photonics,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 8732, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53040-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Q. Cao, N. Zhang, A. Chong, and Q. Zhan, “Spatiotemporal hologram,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 7821, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52268-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] W. Chen, et al.., “Tailoring spatiotemporal wavepackets via two-dimensional space-time duality,” arXiv:2402.07794, 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.07794.Search in Google Scholar

[34] P. Huo, et al.., “Observation of spatiotemporal optical vortices enabled by symmetry-breaking slanted nanograting,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 3055, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47475-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] J. Huang, J. Zhang, T. Zhu, and Z. Ruan, “Spatiotemporal differentiators generating optical vortices with transverse orbital angular momentum and detecting sharp change of pulse envelope,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 16, no. 5, p. 2100357, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202100357.Search in Google Scholar

[36] L. Chen, et al.., “Synthesizing ultrafast optical pulses with arbitrary spatiotemporal control,” Sci. Adv., vol. 8, no. 43, p. eabq8314, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abq8314.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] H. Ge, et al.., “Spatiotemporal acoustic vortex beams with transverse orbital angular momentum,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 131, no. 1, p. 014001, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.014001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] H. Zhang, et al.., “Topologically crafted spatiotemporal vortices in acoustics,” Nat. Commun., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 6238, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41776-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] S. Zhu, X. Zhao, L. Han, J. Zi, X. Hu, and H. Chen, “Controlling water waves with artificial structures,” Nat. Rev. Phys., vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 231–245, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-024-00701-8.Search in Google Scholar

[40] J. Verbeeck, H. Tian, and P. Schattschneider, “Production and application of electron vortex beams,” Nature, vol. 467, no. 7313, pp. 301–304, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09366.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2024-0562).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Special issue on spatiotemporal optical fields

- Reviews

- Synthesis of space-time wave packets using correlated frequency comb and spatial field

- Temporal and spatiotemporal soliton molecules in ultrafast fibre lasers

- Research Articles

- Spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields

- Vector spatial and spatiotemporal laser solitons

- Spatiotemporal optical vortex reconnections of loop vortices

- Double-helix singularity and vortex–antivortex annihilation in space-time helical pulses

- Optical branched flow in nonlocal nonlinear medium

- Observation of replica symmetry breaking in filamentation and multifilamentation

- Optical control of topological end states via soliton formation in a 1D lattice

- Transverse orbital angular momentum of amplitude perturbed fields

- Universal transient radiation dynamics by abrupt and soft temporal transitions in optical waveguides

- Temporal localization of optical waves supported by a copropagating quasiperiodic structure

- Variational approach to multimode nonlinear optical fibers

- Space-time couplings in ultrashort lasers with arbitrary nonparaxial focusing

- Dynamics of dual-orbit rotations of nanoparticles induced by spin–orbit coupling

- Optics of spatiotemporal optical vortices for atto- and nano-photonics

- Photocurrent-induced harmonics in nanostructures

- Transverse orbital angular momentum and polarization entangled spatiotemporal structured light

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Special issue on spatiotemporal optical fields

- Reviews

- Synthesis of space-time wave packets using correlated frequency comb and spatial field

- Temporal and spatiotemporal soliton molecules in ultrafast fibre lasers

- Research Articles

- Spatiotemporal Moiré lattice light fields

- Vector spatial and spatiotemporal laser solitons

- Spatiotemporal optical vortex reconnections of loop vortices

- Double-helix singularity and vortex–antivortex annihilation in space-time helical pulses

- Optical branched flow in nonlocal nonlinear medium

- Observation of replica symmetry breaking in filamentation and multifilamentation

- Optical control of topological end states via soliton formation in a 1D lattice

- Transverse orbital angular momentum of amplitude perturbed fields

- Universal transient radiation dynamics by abrupt and soft temporal transitions in optical waveguides

- Temporal localization of optical waves supported by a copropagating quasiperiodic structure

- Variational approach to multimode nonlinear optical fibers

- Space-time couplings in ultrashort lasers with arbitrary nonparaxial focusing

- Dynamics of dual-orbit rotations of nanoparticles induced by spin–orbit coupling

- Optics of spatiotemporal optical vortices for atto- and nano-photonics

- Photocurrent-induced harmonics in nanostructures

- Transverse orbital angular momentum and polarization entangled spatiotemporal structured light