Abstract

Electrochromic (EC) windows based on reversible metal electro-deposition/dissolution (RME) are exciting alternatives to static lighting control using blinds and shades. However, the difficulty of reversibly and uniformly electrodepositing large-area metal layers seriously hinders the development of RME-type EC windows. In this paper, we develop a novel EC system based on reversible oxide electro-deposition/dissolution (ROE) of MnO2, achieving a profound and bistable color change between rust brown and completely transparent. This ROE-MnO2 system exhibits a significantly high optical modulation amplitude (ΔT) without any deterioration within 1000 switching cycles (ΔT 550nm actually increases from 44.8 % up to 46.9 % after the cycling test), which is almost double compared to the traditional cation-insertion/extraction triggered MnO2 (RCI-MnO2) EC system. This work may inspire the exploration of novel ROE-type EC systems.

1 Introduction

In the past few decades, electrochromic (EC) materials have found many potential applications in fields such as smart windows, switchable mirrors, anti-glare eyewear, passive display, electronic tags, etc., thanks to their flexibly tunable optical properties, low operation voltages and small energy consumption [1–3]. Electrochemically, the EC abilities stem from the redox reaction of active materials [4–6]. The primary reaction mechanisms of EC materials include reversible metal electro-deposition/dissolution (RME, Cu [7], Ag [8, 9], Bi [10], etc., Table S1) or cation insertion/extraction (RCI) [11–14].

In RME-type EC devices, the metal cations in the electrolytes can be readily reduced and deposited on the surfaces of working electrodes (typically FTO or ITO transparent conductive glasses) as metallic layers by applying a proper negative potential, transforming the devices from clear to dark [15]. Applying a positive enough potential can electrochemically oxidize the metallic layers back into metal cations, and thereby bleach the devices [16]. Indeed, there are many metals that can be reversibly electro-deposited/dissolved within cheap and nontoxic aqueous electrolytes [17]. These metals always exhibit high extinction coefficients. Therefore, a uniform metal layer of only 20–30 nm thickness is enough to block out the sunlight, resulting in high optical contrast [18]. Since the metallic layers are in-situ deposited, the RME devices are always structurally simpler than their RCI counterparts, making the fabrication more efficient in both materials and preparation cost [17, 19].

The long-term operation of RME devices requires strict control over the metal nucleation/growth process, in order to ensure uniform deposition and avoid metal dendrite growth derived by “tip discharge effect” [20, 21]. For example, McGehee et al. decorated the surfaces of ITO glass substrate with Pt nanoparticles, which can effectively improve the deposition uniformity of the metal layers as heterogeneous nucleation seeds [21, 22]. Besides, electrolyte formulation [23], adoption of co-deposition system [7], and counter electrode design [20, 24] have also been explored to improve the cycling lifespans of the RME devices. Nevertheless, the dendrite growth driven by “tip discharge effect” is a self-reinforcing and chronic vicious circle, leaving the achievement of durable and large area metal deposition still a substantial challenge [2, 25], [26], [27].

RCI is another common EC mechanism, which works very like the ubiquitous lithium-ion batteries [28, 29]. When a proper electric field is applied, cations and electrons simultaneously insert into or extract from the EC materials, leading to profound color changes due to the optical effects of valence variation [2, 30, 31]. Take MnO2 as an example, its color switching (i.e., cation insertion/extraction) processes can be expressed as [32]:

where A+ represents the inserting cations, which are typically Li+ or K+. The commonly used electrolytes in the RCI-MnO2 systems are LiClO4-PC [33–35] and KCl–H2O solutions [32].

Owing to the obvious optical absorption of A x MnO2, the bleached state of this EC system is still tinted [34], which therefore seriously limits the optical modulation amplitude (ΔT). For this reason, MnO2 is usually combined with other EC materials (e.g., PANI [33], V2O5 [36], and PB [32, 35]) to synergistically achieve high performances.

In this paper, we develop a novel EC system based on reversible oxide electro-deposition/dissolution (ROE) reaction of MnO2. To activate this ROE reaction (Mn2+ + H2O – 2e− ↔ MnO2 + 4H+) [37, 38], an acidic electrolyte containing 0.5 M H2SO4 is adopted to accelerate the reaction kinetics, achieving a profound color change from rust brown to completely transparent, along with more than doubled optical modulation amplitudes compared to the conventional RCI-MnO2 system (ΔT: 45 % vs. 22.5 % at 550 nm, or 88.14 % vs. 12.7 % at 420 nm). To further improve the cycling durability of this ROE system, 15 mM Fe3+ is introduced into the electrolyte as catalysis to facilitate the dissolution of MnO2, resulting in an impressive cycling stability without any EC performance deterioration within 1000 switching cycles (ΔT 550nm actually increases from 44.6 % up to 46.9 % after 1000 cycles). To demonstrate the practical application of this EC system, an ROE-MnO2 dynamic window is assembled with a Cu foil counter electrode, which achieves not only impressive EC performance but also decent energy storage ability. The establishment of this ROE-MnO2 EC system may inspire further exploration of novel EC systems.

2 Experimental

2.1 Establishment of ROE-MnO2 EC system

The ROE-MnO2 system was established in a two-electrode configuration, where a FTO glass (2.5 × 2.5 cm), a Cu foil and a 0.5 M H2SO4 + 1 M MnSO4 + 15 mM CuSO4 aqueous solution were employed as the working electrode, counter/reference electrode and electrolyte, respectively. CV tests indicate that Cu can be smoothly and reversibly striped/plated in this electrolyte (Figure S1), and therefore is used as the counter electrode to compensate charge. To demonstrate the practical application of this EC system, an ROE-MnO2 dynamic window was constructed with a FTO glass working electrode, a narrow Cu belt counter electrode. The Cu counter electrode was attached onto a piece of float glass. These two glasses were separated and adhered by 2-mm thick double-sided tapes (3 M Company), forming a double-paned EC device. Afterwards, the electrolyte was injected into the internal cavity of the device using a syringe.

2.2 Assembly of RCI-MnO2 dynamic window

Preparation of MnO 2 film: The MnO2 film was pre-electrodeposited on a FTO glass at a constant potential of 0.6 V for 500 s by using an electrochemical workstation (CHI660E, Shanghai Chenhua Instruments, Inc.) [39]. The electrodeposition process was performed in a three-electrode configuration that contained a Pt foil (10 mm × 10 mm) counter electrode, an Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) reference electrode and a FTO glass working electrode. In this electrodeposition experiment, a 0.1 M Mn(CH3COO)2 + 0.1 M Na2SO4 aqueous solution was used as the electrolyte. The as-prepared MnO2-coated FTO glass was rinsed with de-ionized water and dried at room temperature.

Assembly of RCI-MnO 2 dynamic window: An RCI-MnO2 dynamic window was constructed with a MnO2-coated FTO glass working electrode and a narrow Cu belt counter electrode. In the cavities of this device, an organic electrolyte consisting of 1 M LiClO4 + 15 mM Cu(ClO4)2 in polycarbonate was injected with a syringe.

2.3 Material characterization

Surficial morphologies of the FTO glass substrate and the deposited MnO2 layers were observed by a JEOL JSM-7610F field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the FTO glasses before and after MnO2 deposition were collected within 10–80° on a D/max-2500/PC X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.1542 nm). XPS (X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy) spectra was collected on Thermo Scientific K-AlphaTM+ spectrometer respectively, in order to investigate the oxidation states of deposited layer.

2.4 Electrochemical and optical characterization

Transmittance tests were carried out on a Persee TU-1810 UV–Vis spectrophotometer within a wavelength range of 200∼1100 nm. All the transmittances are calibrated with a blank device as baseline. To test the EC performance and cycling durability, a CHI-660E electrochemical workstation were used to impose controlled stimulating voltages on the EC systems to activate the color switching reactions. Electrochemical tests of the ROE-MnO2 or RCI-MnO2 were performed in a two-electrode configuration, with a pure FTO glass and a Cu foil as the working and counter/reference electrode, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

Figure 1a shows the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curve of the ROE-MnO2 system in a two-electrode configuration, which shows two cathodic peaks and an anodic peak at 0.4/0.6 V and 1.4 V, respectively. The anodic and cathodic processes can be expressed as [40]:

Characterizations of the ROE-MnO2 system: (a) photographs and typical CV curves swept at 10 mV s−1, (b) XRD pattern, (c) typical SEM images, (d) elemental mapping and (e–g) XPS spectra and fitting results of the in-situ deposited MnO2 in the colored state.

During the anodic process, the FTO working electrode is gradually tinted brown due to the deposition of amorphous MnO2 layer (Figure 1b–d) [41–44]. When the voltage sweeps back to low voltage, the layer and the brown tinct are completely wiped off by the cathodic process (insets of Figure 1a), indicating the occurrence of reverse reaction.

Figure 1c depicts the surficial morphology of the deposited layer, which is composed by uniform and tightly-packed nanoparticles. The successful deposition of MnO2 layer is also confirmed by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). As shown in Figure 1d, the Mn and O elements uniformly distribute to form a 182.9 nm thick layer. Figure 1e presents the Mn 2p X-ray photoelectron spectrum (XPS) of the layer, which can be deconvoluted into two components: Mn4+ at 642.4 and 654.5 eV, and Mn3+ at 641.1 and 653.0 eV, respectively. The valence contributions of Mn4+ and Mn3+ are determined to be 63.65 % and 36.35 %, based on the areas of the deconvoluted peaks. The fitting result of the valence-sensitive Mn 3s peaks demonstrate a spin-energy splitting (ΔEs) of 4.75 eV (Figure 1f), corresponding to a Mn charge state of 3.57 [45], in good line with the Mn 2p-determined value. The deconvoluting result of the O 1s spectrum (Figure 1g) further indicates the co-existence of three Mn states: Mn–O–Mn peak from MnO2 (529.5 eV), Mn–OH peak from MnOOH (531.1 eV), and H–O–H peak from chemosorbed water (532.5 eV). According to the XPS results, the deposited layer should be nonstoichiometric manganese oxide (MnO x ) that consists of amorphous MnO2, MnOOH and chemosorbed water. As expressed in Equations (3) and (4), MnOOH is an intermediate product in the electro-dissolution of MnO2 [40, 46].

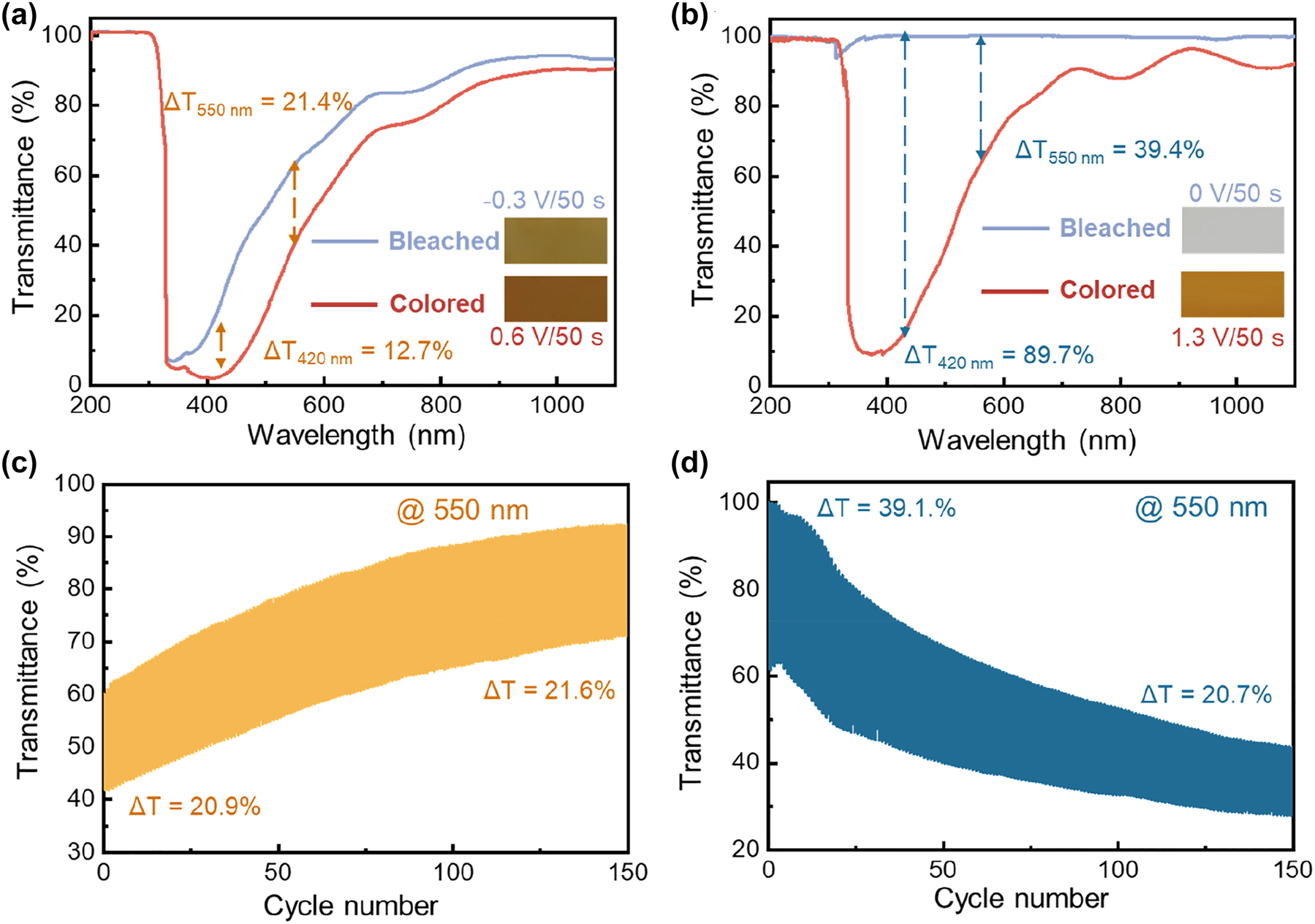

Figure 2a and b compare the transmittance spectra and photographs of the RCI- and ROE-MnO2 EC systems in their bleached and colored state, respectively. The RCI system delivers obviously smaller ΔT in the entire wavelength range, e.g., 12.7 % at 420 nm and 21.4 % at 550 nm, due to the relatively strong optical adsorption of its bleached state. In striking contrast, the ROE system exhibits much stronger color change between rust brow and transparent, thanks to the complete electro-deposition/dissolution of the MnO2 layer. As a result, the system achieves a significant ΔT of 89.7 % at 420 nm, or 39.4 % at 550 nm. However, both of these EC systems suffers from poor cyclic stability (Figure 2c and d). As shown in Figures 2c and S2, the transmittance of the RCI system undergoes a dramatic increase, even through its ΔT 550nm keeps relatively stable (increase from 20.9 % to 21.6 %), suggesting the occurrence of “ion trapping” process [47–49]. On the other hand, the ROE system’s ΔT 550nm gradually deteriorates from 39.1 % down to 20.7 % after 150 times continuous color switching. During cyclic color switching, the transmittances of the ROE system remarkably decrease regardless of the color state, due to the formation and accumulation of residual MnO2 deposits on the FTO glass substrate (Figure S3). During bleaching, the dissolution of MnO2/MnOOH may disconnect the deposits from the substrate, kinetically limiting the complete dissolution of the deposits due to electrically insulation [46].

Electrochromic performance comparison of RCI- and ROE-MnO2 systems: (a and b) transmittance spectra and photographs (inset) in the colored and bleached states, (c and d) transmittance evolution curves at 550 nm during continuous color switching.

To facilitate the dissolution of MnO2, 15 mM FeCl3 is introduced into the electrolyte as a redox mediator. Fe3+/Fe2+ couple has a lower redox potential than the Mn4+/Mn2+ one (Figure 3a and S4) [46], therefore this couple can be used to accelerate the dissolution of MnO2 and MnOOH:

Electrochromic performances of the ROE-MnO2 system in the FeCl3-modified electrolyte: (a) typical CV curves swept at 10 mV s−1, (b) transmittance evolution curves at 550 nm during continuous color switching, (c) transmittance spectra and photographs (inset) in colored and bleached states, (d) transmittance evolution and current response curves showing the coloring/bleaching times, (e) optical density (ΔOD, @550 nm) versus charge density curves.

During the bleaching process, Fe3+ is firstly electrochemically reduced to Fe2+ (Equation (5)), which then reduces the residual MnOOH and MnO2 deposits into soluble Mn2+ (Equations (6) and (7), Figure S5), ensuring the complete dissolution of the deposited layer (Figure S6). Sine the generated Fe3+ can be readily reduced into Fe2+ again, the introduction of Fe3+/Fe2+ couple ensures a long-term effectiveness. As shown in Figure S7a and b, no any residual MnO2 deposits are detected on the working electrode after 150 cycles in this FeCl3-modified electrolyte, leaving the surfaces of the working electrode dense and uniform in both colored and bleached state (Figure S7c and d). As a result, the degradation of optical modulation amplitude is completely eliminated in this electrolyte (Figure 3b). In fact, the ΔT 550nm increases slightly from 44.8 % up to 46.9 % after 1000 cycles.

Besides increasing cycling stability, the addition of FeCl3 also improves the EC performance of this ROE-MnO2 system, thanks to the enhancement of reaction reversibility. As shown in Figure 3c–e, ΔT 550nm of this system increases from 39.4 % up to 45.0 % after FeCl3 addition, while the switching times and coloration efficiency keep comparable (Figure S8a and b). Table S2 systematically compares the performances of the RCI- and ROE-MnO2 EC systems, indicating that this ROE-MnO2 system delivers the best optical contrast.

To demonstrate the practical application of this ROE system, an EC device was assembled by using a FTO glass working electrode, a Cu foil counter electrode, and a FeCl3-modified electrolyte. Figure 4a shows the transmittance spectra and photographs (insets) of this device, which manifest an optical modulation amplitude of 46.6 % at 550 nm, and a coloration/bleaching time of 45/27 s, respectively (Figure 4b). Figure 4c further shown the optical memory ability of this device [50]. After 3600 s open-circuit storage, T bleaching keeps unchanged, while T coloring increased by 17.0 %, because of the current leakage caused by the reaction between Fe2+ and MnO2 (Figure S8c). As expected, the ROE-MnO2 dynamic window shows a decent lifetime with just a slight decrease of the optical modulation amplitude from 46.1 % to 40.9 % after 500 cycles (Figure 4d). Due to the largely different redox potentials of the working and counter electrode, this device shows also a noteworthy energy storage ability. As shown in Figure 4e, the device manifests a charge plateau of ca. 1.2 V and a discharge curve of ca. 1.0 V, in good line with the CV results (Figure 3a). The device exhibits a high capacity of 34.8 µAh cm−2 at a current density of 200 μA cm−2, 17 times higher than that of PB EC layer under the same current density [51]. As shown in Figure S9, two charged (i.e., colored) devices connected in series can successfully light up an LED, highlighting their promising application potential as electrochromic energy storage devices.

Electrochromic performance of the ROE-MnO2 dynamic window: (a) transmittance spectra and photographs (inset) in the colored and bleached states, (b) transmittance evolution curves showing the coloring/bleaching times, (c) transmittance evolution curves during open-circuit storage, (d) transmittance curves at 550 nm during continuous color switching. (e) GCD profiles at a verity of current densities.

4 Conclusions

In summary, a novel electrochromic system based on reversible MnO2 electro-dissolution/deposition is established, in order to boost the optical performance of MnO2-based dynamic windows. This system achieves distinct bistable color change between rust brown and completely transparent, delivering much higher visible modulation amplitude than the traditional cation insertion/extraction MnO2 devices. By introducing Fe3+ into the electrolyte, cycling lifespan of this electrochromic system is effectively prolonged, thanks to the enhancement of MnO2 dissolution by the Fe3+/Fe2+ couple. We also assemble a reversible oxide electro-dissolution/deposition dynamic window, inorder to demonstratet the potential application of this electrochromic system.

Funding source: Open Foundation of Key Laboratory for Palygorskite Science Applied Technology of Jiangsu Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: HPK202103

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: ZR2020ME024

Award Identifier / Grant number: ZR2023QB184

Funding source: Shanghai Municipal Education Commission

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2019-01-07-00-09-E00020

Funding source: Independent Deployment Project of Qinghai Institute of Salt Lakes

Award Identifier / Grant number: E260GC0401

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 22309159

Award Identifier / Grant number: 51502194

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: Unassigned

Funding source: Shanghai Municipal Education Commission

Award Identifier / Grant number: Unassigned

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51502194), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020ME024), the Open Foundation of Key Laboratory for Palygorskite Science Applied Technology of Jiangsu Province (HPK202103), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (No. 2019-01-07-00-09-E00020), and Independent Deployment Project of Qinghai Institute of Salt Lakes, Chinese Academy of Sciences (E260GC0401) for financial support.

-

Research funding: The National Natural Science Foundation of China (51502194), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020ME024), the Open Foundation of Key Laboratory for Palygorskite Science Applied Technology of Jiangsu Province (HPK202103), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (No. 2019-01-07-00-09-E00020), Independent Deployment Project of Qinghai Institute of Salt Lakes, Chinese Academy of Sciences (E260GC0401).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Xuan Liu: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft. Hanbing Wang: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – Original Draft. Junsen Zhong: Data Curation, Formal analysis. Menghan Li: Investigation, Resources. Rui Zhang: Resources. Dongjiang You: Supervision. Lingyu Du: Supervision. Yanfeng Gao: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Resources. Litao Kang: Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding acquisition, Resources.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

-

Data availability: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] M. Buyan, P. A. Brühwiler, A. Azens, G. Gustavsson, R. Karmhag, and C. G. Granqvist, “Facial warming and tinted helmet visors,” Int. J. Ind. Ergon., vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 11–16, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2005.06.005.Search in Google Scholar

[2] F. Zhao, B. Wang, W. Zhang, et al.., “Counterbalancing the interplay between electrochromism and energy storage for efficient electrochromic devices,” Mater. Today, vol. 66, pp. 431–447, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2023.05.003.Search in Google Scholar

[3] B. Wang, F. Zhao, W. Zhang, et al.., “Inhibiting vanadium dissolution of potassium vanadate for stable transparent electrochromic displays,” Small Sci., vol. 3, no. 9, p. 2300046, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/smsc.202300046.Search in Google Scholar

[4] C. Gu, A.-B. Jia, Y.-M. Zhang, and S. X.-A. Zhang, “Emerging electrochromic materials and devices for future displays,” Chem. Rev., vol. 122, no. 18, pp. 14679–14721, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c01055.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] H. Li and A. Y. Elezzabi, “Simultaneously enabling dynamic transparency control and electrical energy storage via electrochromism,” Nanoscale Horiz., vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 691–695, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9nh00751b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] W. Dong, Y. Lv, N. Zhang, L. Xiao, Y. Fan, and X. Liu, “Trifunctional NiO–Ag–NiO electrodes for ITO-free electrochromic supercapacitors,” J. Mater. Chem. C, vol. 5, no. 33, pp. 8408–8414, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7tc03120c.Search in Google Scholar

[7] C. J. Barile, D. J. Slotcavage, J. Hou, M. T. Strand, T. S. Hernandez, and M. D. McGehee, “Dynamic windows with neutral color, high contrast, and excellent durability using reversible metal electrodeposition,” Joule, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 133–145, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2017.06.001.Search in Google Scholar

[8] J. Zhou and Y. Han, “Design of a widely adjustable electrochromic device based on the reversible metal electrodeposition of Ag nanocylinders,” Nano Res., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1421–1429, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-022-4638-2.Search in Google Scholar

[9] W. Zhang, H. Li, and A. Y. Elezzabi, “Nanoscale manipulating silver adatoms for aqueous plasmonic electrochromic devices,” Adv. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 9, no. 19, p. 2200021, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.202200021.Search in Google Scholar

[10] T. S. Hernandez, C. J. Barile, M. T. Strand, T. E. Dayrit, D. J. Slotcavage, and M. D. McGehee, “Bistable black electrochromic windows based on the reversible metal electrodeposition of Bi and Cu,” ACS Energy Lett., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 104–111, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.7b01072.Search in Google Scholar

[11] J. Chu, X. Li, Y. Cheng, and S. Xiong, “Electrochromic properties of Prussian Blue nanocube film directly grown on FTO substrates by hydrothermal method,” Mater. Lett., vol. 258, p. 126782, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2019.126782.Search in Google Scholar

[12] S. Zhou, S. Wang, S. Zhou, et al.., “An electrochromic supercapacitor based on an MOF derived hierarchical-porous NiO film,” Nanoscale, vol. 12, no. 16, pp. 8934–8941, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0nr01152e.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] W. Dong, Y. Lv, L. Xiao, Y. Fan, N. Zhang, and X. Liu, “Bifunctional MoO3-WO3/Ag/MoO3-WO3 films for efficient ITO-free electrochromic devices,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 8, no. 49, pp. 33842–33847, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b12346.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] W. Zhang, H. Li, W. W. Yu, and A. Y. Elezzabi, “Transparent inorganic multicolour displays enabled by zinc-based electrochromic devices,” Light: Sci. Appl., vol. 9, p. 121, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-020-00366-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] X. Tao, D. Liu, J. Yu, and H. Cheng, “Reversible metal electrodeposition devices: an emerging approach to effective light modulation and thermal management,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 9, no. 8, p. 2001847, 2021.10.1002/adom.202001847Search in Google Scholar

[16] T. S. Hernandez, M. Alshurafa, M. T. Strand, et al.., “Electrolyte for improved durability of dynamic windows based on reversible metal electrodeposition,” Joule, vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 1501–1513, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2020.05.008.Search in Google Scholar

[17] G. Cai, A. L.-S. Eh, L. Ji, and P. S. Lee, “Recent advances in electrochromic smart fenestration,” Adv. Sustain. Syst., vol. 1, no. 12, p. 1700074, 2017.10.1002/adsu.201700074Search in Google Scholar

[18] O. S. Heavens and S. F. Singer, “Optical properties of thin solid films,” Phys. Today, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 24–26, 1956. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3059910.Search in Google Scholar

[19] S. Zhao, B. Wang, N. Zhu, et al.., “Dual‐band electrochromic materials for energy‐saving smart windows,” Carbon Neutralization, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 4–27, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnl2.38.Search in Google Scholar

[20] S. M. Islam and C. J. Barile, “Dynamic windows using reversible zinc electrodeposition in neutral electrolytes with high opacity and excellent resting stability,” Adv. Energy Mater., vol. 11, no. 22, p. 2100417, 2021.10.1002/aenm.202100417Search in Google Scholar

[21] M. T. Strand, C. J. Barile, T. S. Hernandez, et al.., “Factors that determine the length scale for uniform tinting in dynamic windows based on reversible metal electrodeposition,” ACS Energy Lett., vol. 3, no. 11, pp. 2823–2828, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01781.Search in Google Scholar

[22] M. Cui, Y. Xiao, L. Kang, et al.., “Quasi-isolated Au particles as heterogeneous seeds to guide uniform Zn deposition for aqueous zinc-ion batteries,” ACS Appl. Energy Mater., vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 6490–6496, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.9b01063.Search in Google Scholar

[23] M. T. Strand, T. S. Hernandez, M. G. Danner, et al.., “Polymer inhibitors enable >900 cm2 dynamic windows based on reversible metal electrodeposition with high solar modulation,” Nat. Energy, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 546–554, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-021-00816-7.Search in Google Scholar

[24] S. M. Islam, T. S. Hernandez, M. D. McGehee, and C. J. Barile, “Hybrid dynamic windows using reversible metal electrodeposition and ion insertion,” Nat. Energy, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 223–229, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0332-3.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Y. Zuo, K. Wang, P. Pei, et al.., “Zinc dendrite growth and inhibition strategies,” Mater. Today Energy, vol. 20, p. 100692, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtener.2021.100692.Search in Google Scholar

[26] A. Hagopian, M.-L. Doublet, and J.-S. Filhol, “Thermodynamic origin of dendrite growth in metal anode batteries,” Energy Environ. Sci., vol. 13, no. 12, pp. 5186–5197, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ee02665d.Search in Google Scholar

[27] D. Lin, Y. Liu, and Y. Cui, “Reviving the lithium metal anode for high-energy batteries,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 194–206, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2017.16.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] W. Zhang, H. Li, and A. Y. Elezzabi, “Electrochromic displays having two‐dimensional CIE color space tunability,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 32, no. 7, p. 2108341, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202108341.Search in Google Scholar

[29] L. Xiao, Y. Lv, W. Dong, N. Zhang, and X. Liu, “Dual-functional WO3 nanocolumns with broadband antireflective and high-performance flexible electrochromic properties,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 8, no. 40, pp. 27107–27114, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b08895.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] H. Li, W. Zhang, and A. Y. Elezzabi, “Transparent zinc-mesh electrodes for solar-charging electrochromic windows,” Adv. Mater., vol. 32, no. 43, p. e2003574, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202003574.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] L. Xiao, Y. Lv, J. Lin, et al.., “WO3‐Based electrochromic distributed bragg reflector: toward electrically tunable microcavity luminescent device,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 6, no. 1, p. 1700791, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201700791.Search in Google Scholar

[32] D. Ma, A. Lee-Sie Eh, S. Cao, P. S. Lee, and J. Wang, “Wide-spectrum modulated electrochromic smart windows based on MnO2/PB films,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1443–1451, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c20011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] D. Zhou, B. Che, and X. Lu, “Rapid one-pot electrodeposition of polyaniline/manganese dioxide hybrids: a facile approach to stable high-performance anodic electrochromic materials,” J. Mater. Chem. C, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 1758–1766, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6tc05216a.Search in Google Scholar

[34] S.-M. Wang, Y.-H. Jin, T. Wang, K.-H. Wang, and L. Liu, “Polyoxometalate-MnO2 film structure with bifunctional electrochromic and energy storage properties,” J. Materiomics, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 269–278, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmat.2022.10.007.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Y. Ding, M. Wang, Z. Mei, and X. Diao, “Novel prussian white@MnO2-based inorganic electrochromic energy storage devices with integrated flexibility, multicolor, and long life,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 14, no. 43, pp. 48833–48843, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c12484.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] S. Sajitha, U. Aparna, and B. Deb, “Ultra‐Thin manganese dioxide‐encrusted vanadium pentoxide nanowire mats for electrochromic energy storage applications,” Adv. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 6, no. 21, p. 1901038, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201901038.Search in Google Scholar

[37] M. Wang, X. Zheng, X. Zhang, et al.., “Opportunities of aqueous manganese‐based batteries with deposition and stripping chemistry,” Adv. Energy Mater., vol. 11, no. 5, p. 2002904, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202002904.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Y. Liu, C. Xie, and X. Li, “Bromine assisted MnO2 dissolution chemistry: toward a hybrid flow battery with energy density of over 300 Wh L-1,” Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., vol. 61, no. 51, p. e202213751, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202213751.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] S. Xie, Y. Chen, Z. Bi, et al.., “Energy storage smart window with transparent-to-dark electrochromic behavior and improved pseudocapacitive performance,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 370, pp. 1459–1466, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.03.242.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Z. Feng, Z. Gao, Z. Xue, M. Yang, and X. Zhao, “Acidity modulation of electrolyte enables high reversible Mn2+/MnO2 electrode reaction of electrolytic Zn-MnO2 battery,” J. Electron. Mater., vol. 51, no. 11, pp. 6041–6046, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-022-09845-8.Search in Google Scholar

[41] J. Shao, W. Li, X. Zhou, and J. Hu, “Magnetic-field-assisted hydrothermal synthesis of 2 × 2 tunnels of MnO2 nanostructures with enhanced supercapacitor performance,” CrystEngComm, vol. 16, no. 43, pp. 9987–9991, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ce01385a.Search in Google Scholar

[42] H. Sun, Z. Hu, C. Yao, J. Yu, and Z. Du, “Silver doped amorphous MnO2 as electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction in Al-air battery,” J. Electrochem. Soc., vol. 167, no. 8, p. 080539, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/ab91c7.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Y. Wang, J. Liu, H. Yuan, F. Liu, T. Hu, and B. Yang, “Strong electronic interaction between amorphous MnO2 nanosheets and ultrafine Pd nanoparticles toward enhanced oxygen reduction and ethylene glycol oxidation reactions,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 33, no. 21, p. 2211909, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202211909.Search in Google Scholar

[44] H. Bai, S. Liang, T. Wei, et al.., “Enhanced pseudo-capacitance and rate performance of amorphous MnO2 for supercapacitor by high Na doping and structural water content,” J. Power Sources, vol. 523, p. 231032, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2022.231032.Search in Google Scholar

[45] M. Sun, B. Lan, T. Lin, et al.., “Controlled synthesis of nanostructured manganese oxide: crystalline evolution and catalytic activities,” CrystEngComm, vol. 15, no. 35, pp. 7010–7018, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ce40603b.Search in Google Scholar

[46] X. Ye, D. Han, G. Jiang, et al.., “Unraveling the deposition/dissolution chemistry of MnO2 for high-energy aqueous batteries,” Energy Environ. Sci., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 1016–1023, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3ee00018d.Search in Google Scholar

[47] S. Huang, R. Zhang, P. Shao, Y. Zhang, and R. T. Wen, “Electrochromic performance fading and restoration in amorphous TiO2 thin films,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 10, no. 16, p. 2200903, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202200903.Search in Google Scholar

[48] R. T. Wen, C. G. Granqvist, and G. A. Niklasson, “Eliminating degradation and uncovering ion-trapping dynamics in electrochromic WO3 thin films,” Nat. Mater., vol. 14, no. 10, pp. 996–1001, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4368.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] P. Shao, S. Huang, B. Li, Q. Huang, Y. Zhang, and R.-T. Wen, “Eradicating β-trap induced bleached-state degradation in amorphous TiO2 electrochromic films,” Mater. Today Phys., vol. 30, p. 100958, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2022.100958.Search in Google Scholar

[50] B. Wang, M. Cui, Y. Gao, et al.., “A long‐life battery‐type electrochromic window with remarkable energy storage ability,” Sol. RRL, vol. 4, no. 3, p. 1900425, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/solr.202070036.Search in Google Scholar

[51] B. Huang, J. Song, J. Zhong, et al.., “Prolonging lifespan of Prussian blue electrochromic films by an acid-free bulky-anion potassium organic electrolyte,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 449, p. 137850, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.137850.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2023-0573).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Thermal photonics for sustainability

- Review

- Switchable radiative cooling and solar heating for sustainable thermal management

- Perspective

- Radiative cooling: arising from practice and in turn serving practice

- Research Articles

- Superhydrophobic bilayer coating for passive daytime radiative cooling

- Investigation of recycled materials for radiative cooling under tropical climate

- A scalable and durable polydimethylsiloxane-coated nanoporous polyethylene textile for daytime radiative cooling

- Three-dimensionally printable hollow silica nanoparticles for subambient passive cooling

- High albedo daytime radiative cooling for enhanced bifacial PV performance

- Enhanced radiative cooling with Janus optical properties for low-temperature space cooling

- Efficient radiative cooling of low-cost BaSO4 paint-paper dual-layer thin films

- Radiative cooling textiles using industry-standard particle-free nonporous micro-structured fibers

- Aqueous double-layer paint of low thickness for sub-ambient radiative cooling

- Porous polymer bilayer with near-ideal solar reflectance and longwave infrared emittance

- Visible light electrochromism based on reversible dissolution/deposition of MnO2

- Energy scavenging from the diurnal cycle with a temperature-doubler circuit and a self-adaptive photonic design

- Reverse-switching radiative cooling for synchronizing indoor air conditioning

- Porous vanadium dioxide thin film-based Fabry−Perot cavity system for radiative cooling regulating thermochromic windows: experimental and simulation studies

- Theoretical study of a highly fault-tolerant and scalable adaptive radiative cooler

- Ultra-broadband and wide-angle nonreciprocal thermal emitter based on Weyl semimetal metamaterials

- Transparent energy-saving windows based on broadband directional thermal emission

- Lithography-free directional control of thermal emission

- GAGA for nonreciprocal emitters: genetic algorithm gradient ascent optimization of compact magnetophotonic crystals

- Ultra-broadband directional thermal emission

- Tailoring full-Stokes thermal emission from twisted-gratings structures

- Effectiveness of multi-junction cells in near-field thermophotovoltaic devices considering additional losses

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Thermal photonics for sustainability

- Review

- Switchable radiative cooling and solar heating for sustainable thermal management

- Perspective

- Radiative cooling: arising from practice and in turn serving practice

- Research Articles

- Superhydrophobic bilayer coating for passive daytime radiative cooling

- Investigation of recycled materials for radiative cooling under tropical climate

- A scalable and durable polydimethylsiloxane-coated nanoporous polyethylene textile for daytime radiative cooling

- Three-dimensionally printable hollow silica nanoparticles for subambient passive cooling

- High albedo daytime radiative cooling for enhanced bifacial PV performance

- Enhanced radiative cooling with Janus optical properties for low-temperature space cooling

- Efficient radiative cooling of low-cost BaSO4 paint-paper dual-layer thin films

- Radiative cooling textiles using industry-standard particle-free nonporous micro-structured fibers

- Aqueous double-layer paint of low thickness for sub-ambient radiative cooling

- Porous polymer bilayer with near-ideal solar reflectance and longwave infrared emittance

- Visible light electrochromism based on reversible dissolution/deposition of MnO2

- Energy scavenging from the diurnal cycle with a temperature-doubler circuit and a self-adaptive photonic design

- Reverse-switching radiative cooling for synchronizing indoor air conditioning

- Porous vanadium dioxide thin film-based Fabry−Perot cavity system for radiative cooling regulating thermochromic windows: experimental and simulation studies

- Theoretical study of a highly fault-tolerant and scalable adaptive radiative cooler

- Ultra-broadband and wide-angle nonreciprocal thermal emitter based on Weyl semimetal metamaterials

- Transparent energy-saving windows based on broadband directional thermal emission

- Lithography-free directional control of thermal emission

- GAGA for nonreciprocal emitters: genetic algorithm gradient ascent optimization of compact magnetophotonic crystals

- Ultra-broadband directional thermal emission

- Tailoring full-Stokes thermal emission from twisted-gratings structures

- Effectiveness of multi-junction cells in near-field thermophotovoltaic devices considering additional losses