High-sensitivity polarization-independent terahertz Taichi-like micro-ring sensors based on toroidal dipole resonance for concentration detection of Aβ protein

-

Wencan Liu

, Mengqiang Cai

and Jiangtao Lei

Abstract

Terahertz (THz) metamaterial sensor is a newly-developing interdisciplinary technology, which combines the essential characteristics of THz spectroscopy and metamaterials, to obtain better sensitivity for trace detection of the different target analytes. Toroidal dipole resonances show great sensing potential due to their suppression of the radiative loss channel. Here, we found a high-quality planar toroidal dipole resonance in the breaking Chinese Taichi-like ring and then designed a novel polarization-independent terahertz toroidal sensor by combining four Taichi-like rings into a cycle unit. The sensor shows high-sensitivity sensing characteristics for the ultrathin analyte and refractive index. The optimized sensitivity of pure analytes under 4 μm coating thickness can numerically reach 258 GHz/RIU in the corresponding ∼1.345 THz frequency domain, which is much higher than that of previously reported sensors. We further fabricated experimentally the sensor and demonstrated its fascinating polarization-independent characteristics. Finally, it was successfully applied to the low-concentration detection (ranging from 0.0001 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL) of Aβ protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Our high-sensitivity polarization-independent THz toroidal dipole sensor would give access to rich applications in label-free biosensing.

1 Introduction

Terahertz (THz) spectroscopy has received growing attention in biomedical applications owing to its prominent characteristics of non-invasive, non-ionizing, low scattering, high penetrability, and fingerprint spectrum [1–6]. It can generally be applied to probe and characterize various biomolecules including nucleic acid [7, 8], protein [9], phospholipid [10], cell [11], and tissue [12]. However, the low sensitivity of free-space THz detector limits the trace detection of many biomolecules. Fortunately, THz metamaterials present tremendous opportunities to effectively extend the utilization of THz technology in the biosensing field by boosting light–matter interactions [13, 14].

THz metamaterials are periodic artificial electromagnetic media with extraordinary physical properties that cannot be found in nature, involving anomalous refraction [15, 16], negative permeability [17], super-absorption [18], cloakings [19, 20], etc… Besides those inspiring advances, the appearance of a spoof surface plasmon with localized electric field enhancement near the metal, as well as large values of quality factor (Q factor) [21], makes these metamaterials highly sensitive to minor environmental changes [13]. Researchers have shown that these properties generally are not derived from the physical properties of materials themselves but mostly depend on artificially constructed structures [22]. Therefore, a variety of THz metamaterial sensors based on different structures and corresponding physical rules have been proposed [23, 24]. For example, Wu et al. fabricated U-shaped golden split ring sensors with an inductor-capacitor (LC) and plasmonic dipole resonance to detect streptavidin–agarose [25]. Qin et al. designed circular apertures for the detection of tetracycline hydrochloride based on the extraordinary optical transmission (EOT) effect [26]. Zhang et al. fabricated an electromagnetic-induced-transparency (EIT) biosensor consisting of cut wires and split ring resonators to distinguish mutant and wild-type glioma cells [27]. Zhou et al. designed a label-free Fano-based THz microfluidic sensor for DNA molecule detection [28]. As sign-enhanced carriers, THz metamaterials are indeed very suitable to detect biomolecules and biological samples.

Among these THz metamaterials, toroidal dipole metamaterials have received growing attention and are considered as a novel approach to regulating intrinsic radiative losses in recent years [29]. Different from the traditional electric and magnetic dipoles, toroidal dipoles are characterized by the creation of a closed-loop configuration of the magnetic fields and currents rotating on the surface of a torus [30]. Researchers have shown that the Q factor and the figure of merit of the toroidal dipolar mode are significantly higher than traditional Fano resonance [31]. Meantime, THz toroidal metamaterial presents unique tunable properties, such as dynamically switching capacity to the fundamental electric dipole or magnetic dipole [30, 32]. Considering the unique advantages, THz toroidal metamaterials have been explored for the ultra-trace detection of biomolecules. Ahmadivand et al. achieved rapid detection of infectious envelope proteins by magnetoplasmonic toroidal metasensors [33]. Wang et al. reported ultrasensitive THz sensing with high-Q toroidal dipole resonance governed by bound states in the continuum (BIC) in an all-dielectric metasurface [34].

Alzheimer’s (AD) is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disease and mainly characterized by the deposition of extracellular plaque composed of amyloid-β protein (Aβ) [35, 36]. The Aβ levels in the blood are efficacious in predicting the severity and progression at early or preclinical stages of AD [37]. Various fluorescent biosensors are developed to provide Aβ pathology information [38]. However, fluorescence labels such as Congo red and thioflavin-T analogs have been found to inhibit further fibrillization due to Aβ binding [39], thus affecting the accuracy of the detection. Recently, label-free THz near-field spectroscopy can be used to identify the fibrillization state of Aβ protein [40]. Our group also reported that THz metal-graphene hybrid metamaterial can monitor the aggregation of Aβ16–22 peptides by successfully linking the Fermi level change of graphene to the shifting Rabi splitting peaks [41]. It is of great significance to further develop new THz metamaterials to detect Aβ concentrations more accurately.

Considering the Q factor and the measurement stability are always affected by the electric field polarization of the incident THz wave [42], we introduced symmetry breaking into the centrosymmetric Chinese Taichi-like ring, with which a high-quality planar toroidal dipole response model can be excited. Thus, a novel polarization-independent THz toroidal sensor can be designed by combining four Taichi-like rings into one unit with a 90° rotation. The sensor shows high sensitivity to environmental perturbations, such as the ultrathin thickness and refractive index of the analyte layer. The optimized sensitivity of pure analytes under 4 μm coating thickness can numerically reach a high value of 258 GHz/RIU in the corresponding ∼1.345 THz frequency domain, showing a high sensitivity characteristic. Then, we fabricated experimentally the sensor and demonstrated its attractive polarization-independent characteristics. Finally, it was successfully applied to the low-concentration detection of Aβ protein ranging from 0.0001 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL. Our high-sensitivity polarization-independent THz toroidal dipole sensor would give access to rich applications in the diagnosis of related diseases.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Structural design of THz Taichi-like ring metamaterial with toroidal dipole resonance

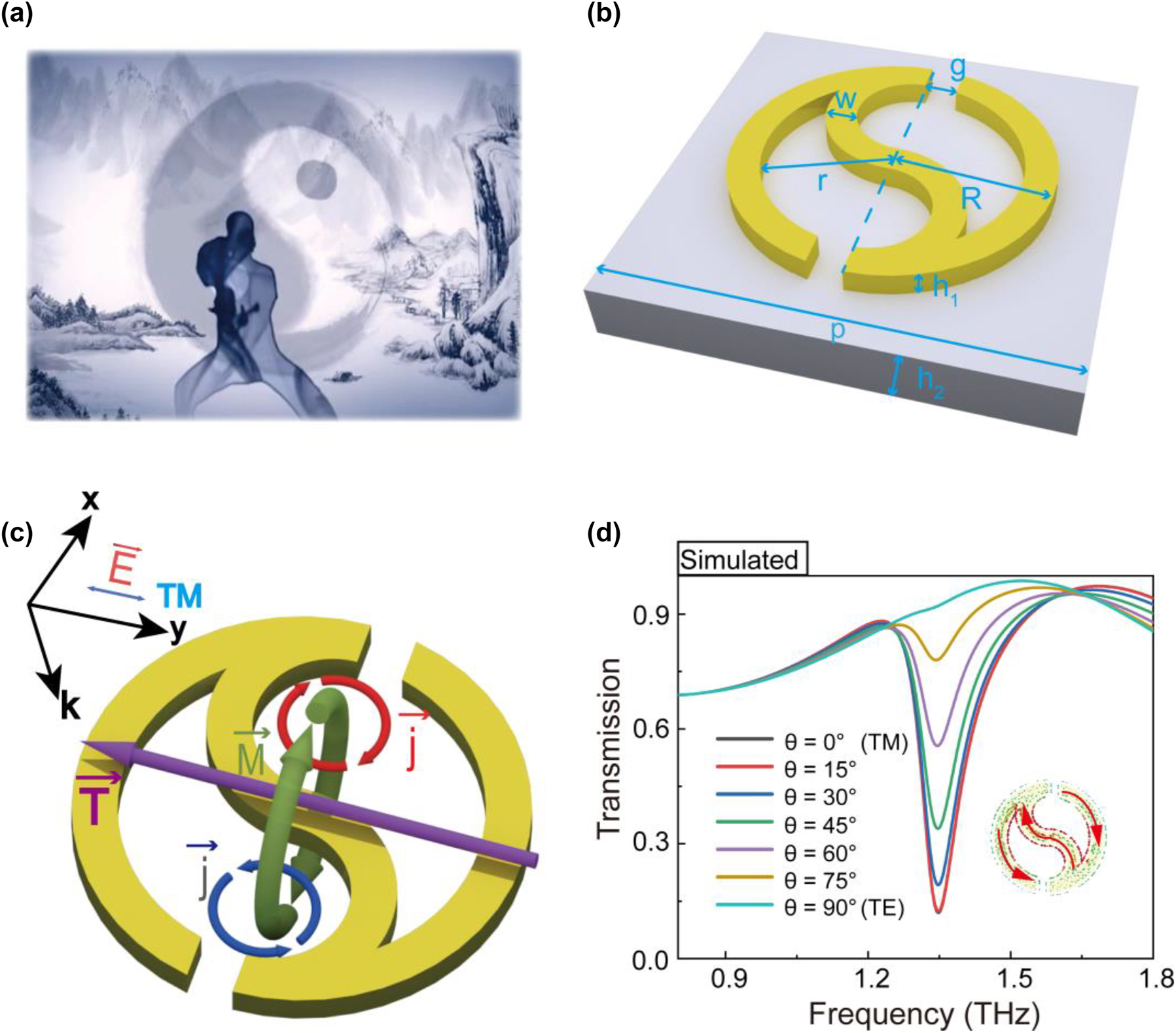

Many studies have shown that strong toroidal resonances can be aroused by extraordinary 2D metamaterials with perfect symmetric and breaking geometries [31, 33, 43]. Inspired by a large symmetric Taichi diagram from ancient and mysterious Chinese culture (shown in Figure 1a), we designed a novel high-Q planar toroidal dipole response metamaterial by introducing symmetry breaking into the Taichi ring. As shown in Figure 1b, the half of a single Taichi-like ring (STR) is wide in size at the head and gradually becomes small at the tail, and the designed unit cell of the resonator is a single ring with a split gap at the upper and lower heads. The structural parameters are as follows: the STR has an outer radius of R = 14 μm, an inner radius of r = 11 μm, a split gap of g = 3 μm, a line width of w = 3 μm (w = R − r) and a thick of h = 200 nm. The metamaterial resonator consists of copper (Cu) STR arrays with a period of p = 80 μm on a 50 μm thick polyimide (PI) substrate.

Structural design of a single Taichi-like ring for THz toroidal dipole metamaterial. (a) Taichi diagram in ancient and mysterious Chinese culture. (b) Schematic of the single Taichi-like ring (STR) metasurface. (c) Toroidal dipole resonance generated by the STR under TM polarization. (d) Transmission spectra of the STR metasurface under different polarized light incidents.

When the STR is normally illuminated by an incident THz beam with TM polarization (where the incident electric field is parallel to the y-axis), the surface currents (j) along the superatom are excited, and the current loops construct magnetic dipoles in opposite directions, and thus a head-to-tail magnetic field (M) is constructed and confined (seen in Figure 1c). According to the right-hand rule, such a loop magnetic field results in a toroidal dipole vector along the y-axis, shown as the purple arrow in Figure 1c. Detailed simulation results of the surface currents (j) and magnetic field (M) are presented in the inset of Figure 1d and Figure S1 in the Supplementary material, respectively. Figure 1d exhibits the transmission spectra of STR illuminated by incident THz beam with different polarized angles ranging from 0° to 90°. The transmission spectrum with TM polarization shows the largest resonance dip at 1.345 THz, where the spins made up of surface currents are in opposite directions (inset in Figure 1d), thus forming a toroidal dipole resonance. Though THzlight with different polarizations (except the TE model) can stimulate a resonance dip at 1.345 THz, the quality factor will reduce with the increased angle.

2.2 Polarization-independent characteristics of quadruple Taichi-like rings

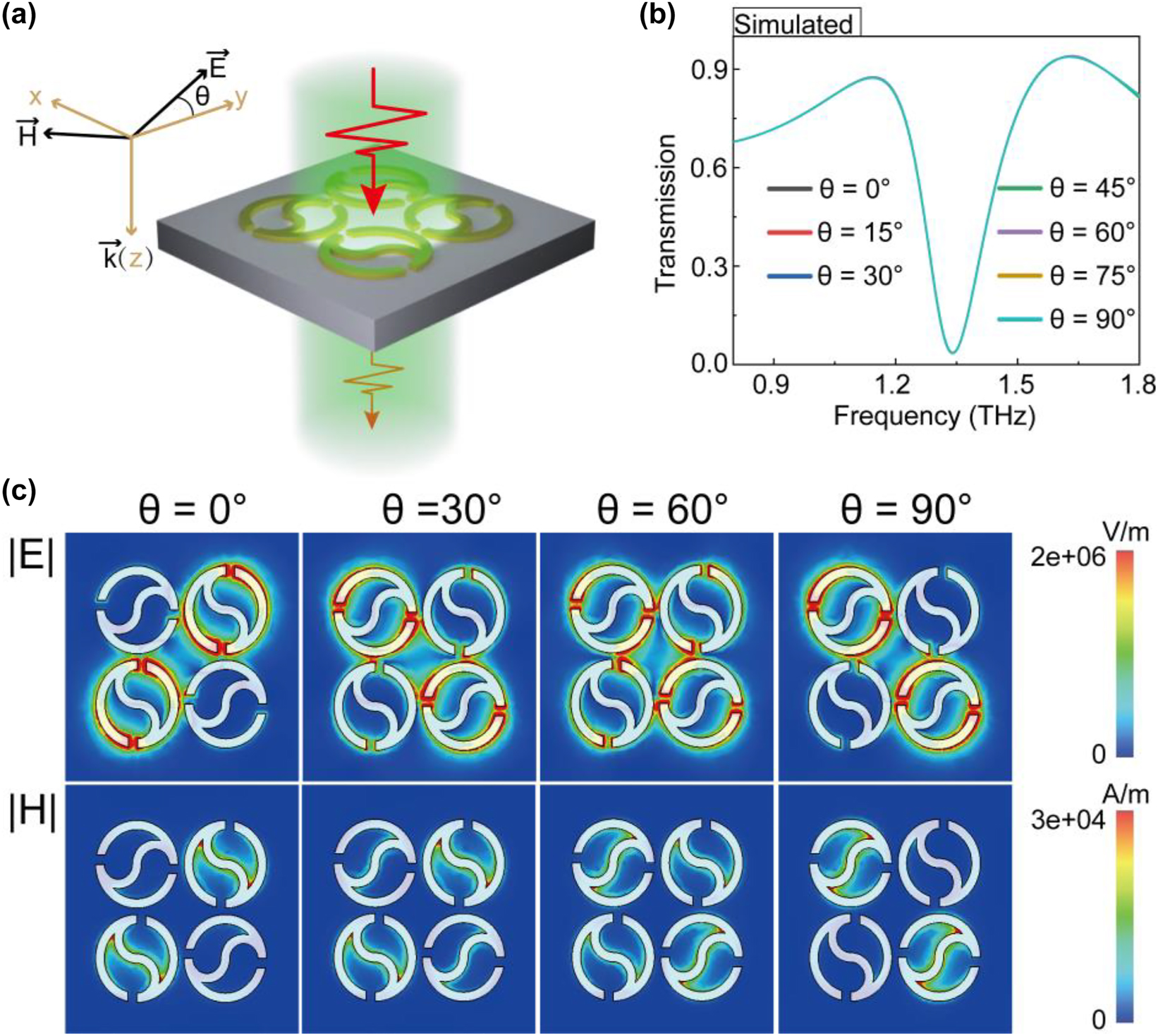

In order to eliminate the quality-factor degradation caused by the polarization angle of incident THz light, we further designed a novel polarization-independent THz toroidal sensor by combining four Taiji rings into a cycle unit with an unchanged period. As shown in Figure 2a, the two pairs of diagonal structures were perpendicular to each other and the unit cell thus has group C4 symmetry. For the quadruple Taichi ring (QTR) metasurface, the superatoms are symmetric along the x-axis and y-axis, which is expected to lead to the same frequency response under different polarization incidences. To verify this conclusion, we simulated the transmission spectra of the QTR metasurface illuminated by incident light with multiple polarization angles. It turns out that these transmission spectra overlap very well, as shown in Figure 2b, indicating that the toroidal resonance response of QTR metasurface is polarization-independent.

Quadruple Taichi-like rings (a) schematic of QTR metasurface with the incident polarization angle θ. (b) The transmission spectra of the QTR metasurface illuminated by incident light with multiple polarization angle θ. (c) Near electromagnetic field distribution of polarization excitation with various angles at toroidal resonance frequencies.

To further study the physical mechanism of polarization-independent characteristics, the electromagnetic field distributions at polarization angles of 0°, 30°, 60°, and 90° were monitored at the resonance frequency, as shown in Figure 2c. When the polarization angle is 0°, the incident light only excites the surface plasma resonance of the two Taichi-like rings on the diagonal in the supercell. Meanwhile, we noted that the areas with electric field enhancement and magnetic field enhancement are mainly located at the heads and the tail of Taichi-like ring, respectively. With the variation of polarization angle, the excitation intensity of the surface plasma resonance gradually transits to the other diagonal Taichi-like rings. These results indicate that our designed structure presents polarization-independent characteristics.

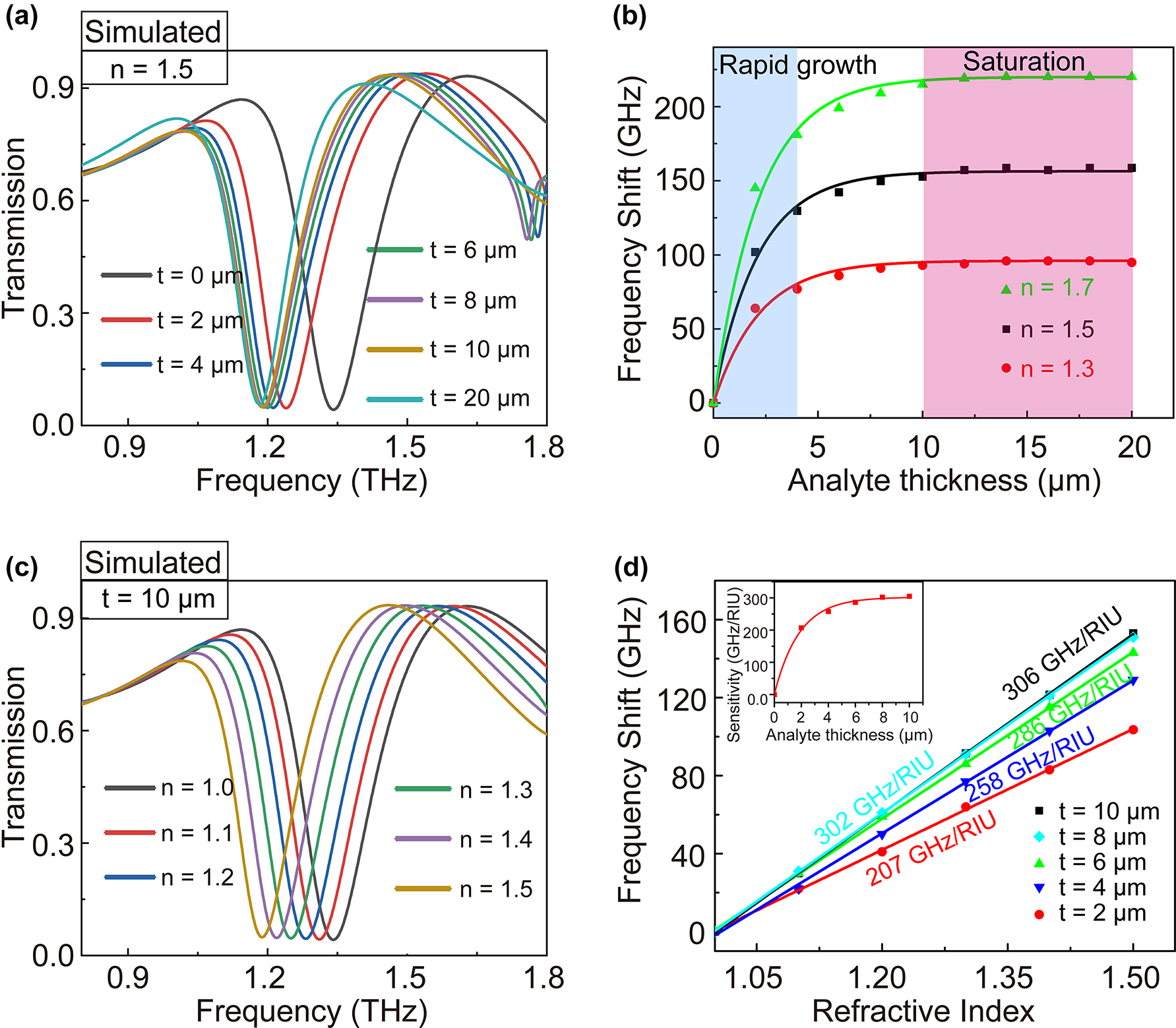

2.3 High-sensitivity sensing characteristics for ultrathin analyte

To investigate sensing characteristics for biosensing applications, we simulated the variation of transmission spectra with the refractive index n and thickness t of the covered analyte. Figure 3a shows the dependence of THz spectra on the analyte thickness when an analyte with a refractive index of 1.5 is deposited on the surface of the QTR metasurface. The transmission spectra present a gradual redshift from 1.345 to 1.187 THz, as the analyte thickness increases from 0 μm (without analyte) to 20 μm. The relative frequency shift Δf is calculated as f(t)−f(t0), where f(t) is the resonance frequency with analyte thickness t, and f(t0) is the resonance frequency without the analyte. As shown in Figure 3b, frequency shift Δf rapidly increases within the first 4 μm analyte thickness and then achieves slowly a saturation state until 10 μm, showing that Δf as a function of analyte thickness satisfies saturation nonlinearity. This phenomenon meets the localization effect of the electromagnetic field of the local surface plasma resonance.

The analyses of sensing characteristics. The simulated transmission spectra of QTR metasurface with the variation of (a) thickness (n = 1.5) and (c) refractive of the analyte (h = 10 μm). (b) The frequency shift of QTR metasurface versus the thickness of analyte (n = 1.5). (d) The frequency shifts of QTR metasurface versus the refractive index with different thicknesses of the analyte. Linear fit has been performed to determine the sensitivity of the metasurface.

Subsequently, we numerically calculated transmission spectra as the refractive index of the analyte increased from 1.0 to 1.5, by remaining a saturated thickness of 10 μm. The results were shown in Figure 3c. It can be seen that the resonance dip shows a redshift from 1.345 to 1.192 THz with the refractive index varying from 1 to 1.5. As shown in Figure 3d, different from the transformation law of frequency shift Δf versus the thickness, the fitting function Δf versus refractive index satisfies an almost linear relation. The refractive index sensitivity S can be calculated as S = Δf/Δn. For the analyte with a saturated thickness of 10 μm, the largest theoretical sensitivity reaches up to 306 GHz/RIU (RIU, Refractive Index Unit). However, biomolecular analyte generally is extremely thin in biosensing applications. Therefore, we pay more attention to the sensitivity of the ultra-thin analyte. It is important to note that the sensitivity trends to nonlinear (exponential) saturation of growth with the increased thicknesses (inset of Figure 3d). The sensitivity S = 258 GHz/RIU (with t = 4 μm) of our QTR metasurface has reached 84% of its saturation, showing its great superiority in the detection of ultrathin analytes.

To further assess the level of refractive index sensitivity of our proposed metasurface for the ultrathin analyte, we compared the performance with those of reported state-of-the-art THz metasurface sensors. According to perturbation theory [44, 45], the frequency shift Δf of the metasurface is not only related to the thickness and refractive index of the analytes but also the resonant frequency f0. The frequency shift Δf is generally large with high resonance frequency. Hence, it is unreasonable or rigorous to show the superiority of our structure by merely comparing the value of refractive index sensitivity S = Δf/Δn but ignoring the thickness and the resonance frequency f0. In Figure 4, we changed the resonance frequency f0 from 0.465 and 2.540 THz by adjusting the geometrical parameters of the QTR metasurface (shown in the inset of Figure 4). When the thickness t = 4 μm, the refractive index sensitivities are approximately proportional to the resonant frequency f0 (ranging from 0.465 to 2.540 THz). Ultimately, a comparison of the performance of our proposed metasurface to those of reported state-of-the-art THz metasurface sensors [34, 46], [47], [48], [49], [50] is presented in Figure 4. Our structure has a high sensitivity for 4 μm thick analytes and shows its great superiority in sensing applications over the previous works. These results demonstrate that our QTR ring dipole resonant metasurface is extremely sensitive to the small change in thickness and refractive index of ultrathin analyte and thus enhances its application potential for the detection of biomolecules.

Refractive index sensitivity with varying resonant frequencies for 4 µm thick analyte. Our QTR metasurfaces are shown as red squares (The aforementioned structure is specifically marked as a yellow five-pointed star). Compared metasurface sensors are shown as blue triangles and the serial number of corresponding references is marked.

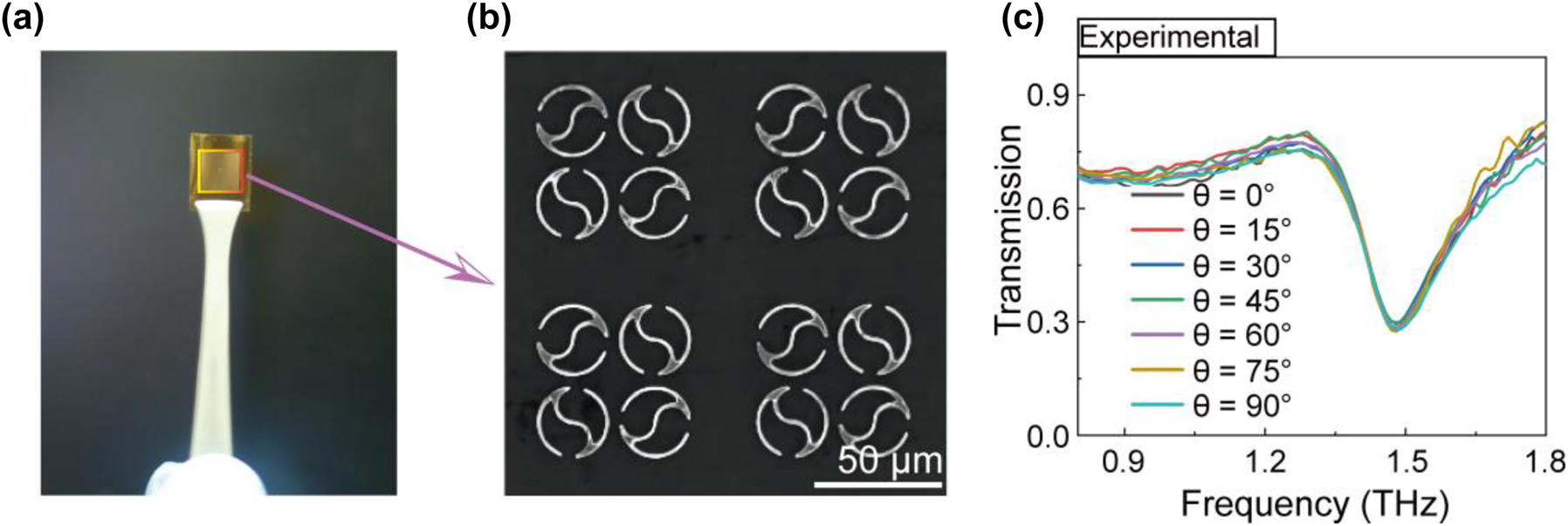

2.4 Experimental preparation and validation

To verify the proposed structure, a 200 nm thick 80 × 80 QTR array was fabricated by photolithography on a 50 μm thick polyimide film (Figure 5a). The detailed fabrication method is shown in Supplementary Figure S3. An optical microscopy image of the metasurface is shown in Figure 5b. We first investigated the independence of QTR’s toroidal resonance on the polarization angles of the THz beam by measuring the transmission spectra with a commercial THz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDs) system (BATOP-TDS1008). As seen in Figure 5c, the resonance frequency dip of the transmission spectrum under Ey-polarized (θ = 0°) THz waves emerged at 1.490 THz. As the variation of polarization angles of the THz beam from 0° to 90°, the transmission spectra and their resonance frequency dip overlap very well, consistent with the simulational results (Figure 2b). Compared to the numerically simulated spectra (Figure 2b), the experimental resonant intensity decrease and frequency blueshift with the value of 0.145 THz. The differences result from the slight absorption of polyimide film and the structural parameter deviation between the simulation and experiment. With the variation of the split gap, the tail, the outer radius and the inner radius, the resonance frequency shows a blue or red shift in the transmission spectrum (Figure S3). In addition, the roughness of the structure in the experiment would increase the Ohmic loss, which is reflected in the lower Q factor than the simulated transmission spectrum. Despite these biases, these experimental results still confirm that the toroidal resonance of our designed QTR is independent of the polarization of the incident light.

Polarization-independent behavior of QTR metasurface in the experiments (a) metasurface structure on PI substrate. (b) Microscopic image of QTR ring metasurface. (c) Experimental verification of resonant frequency response for different polarization angles.

2.5 Concentration detection of Aβ protein

To investigate the performance of our QTR metasurface for biosensing applications, Aβ proteins with different concentrations were chosen as the analytes. Figure 6a shows a schematic illustration of Aβ protein deposited to the structure surface. Aβ solution samples with concentrations of 10 mg/mL, 1 mg/mL, 0.1 mg/mL, 0.01 mg/mL 0.001 mg/mL, and 0.0001 mg/mL were dropped onto the QTR surface, and then are quick-freezed at −80 °C after five-minute waiting and finally are freeze-dried at −20 °C in vacuum. Aβ aggregation involves the formation of different species of aggregates, including oligomers, protofilaments and mature fibrils [51]. The transition from monomers to initial oligomers, subsequent protofilaments, and eventual fibrils is considered to follow a nucleation–elongation process, consisting of three phases: lag phase, elongation phase, and steady phase [52, 53]. A large number of experiments show that the whole aggregation process generally needs to spend several hours [54–56]. In our experiment, we strictly control the incubation time in a matter of five minutes. As in any kinetical reaction, the Aβ fibrillization is strongly dependent on the temperature [57]. Therefore, quick-freezing (−80 °C) and vacuum freeze-drying (−20 °C) technique was used to block the Aβ aggregation and maintain its aqueous states as much as possible. As a result, our sensor primarily is used to detect Aβ monomers in the early stage of aggregation through these steps. The micrographs of protein analytes with the first three concentrations are shown in Figure 6b. The thin layers of Aβ protein with high concentrations of 10 mg/mL and 1 mg/mL and their drying cracks can be seen on the sensor surface. As the concentration decreases from 0.1 mg/mL to 0.0001 mg/mL, the reduction of sporadic protein accumulations could be observed (Figure 6b and Figure S4). Transmission spectra of QTR metasurface with Aβ protein were measured using THz-TDs system (Figure 6c). It can be seen that the resonance frequency of QTR metasurface without Aβ analyte coverage is 1.490 THz. As Aβ is covered by 10 mg/mL, 1 mg/mL, and 0.1 mg/mL, the resonance frequency blueshifts to 1.245, 1.431, and 1.482 THz, respectively. The reason for blueshift is that the variation of Aβ concentration covered on the surface of the structure shows a great effect on the equivalent refractive indices and thicknesses. The variation curve of resonance frequency shift versus Aβ concentration is shown in Figure 6d and all error bars also are shown in Supplementary Tables S1. Limited to the resolution ratio of our THz TDS system, the lowest detection limit of Aβ concentration is 0.0001 mg/mL with a 7 GHz frequency shift.

Concentration detection of Aβ protein. (a) Schematic illustration of QTR metasurface biosensor with Aβ protein. (b) Microscopic images of Aβ protein deposited on the metasurface with different concentrations. (c) The measured transmission spectra of Aβ protein deposited on the metasurface with different concentrations. (d) The frequency shift versus different concentrations of Aβ protein.

To assess the sensing level of our QTR metasurface biosensor for Aβ protein, we compared detection range with those of some representative biosensors. As seen in Table 1, the conventional detection sensors of Aβ include colorimetric [58, 59], electrochemistry [60, 61], fluorescent [62, 63] and immune [64, 65] sensor. The lower limit of detection of our QTR metasurface biosensor is comparable to that of colorimetric, electrochemistry and fluorescent biosensor but not as good as that of these immunosensor. The results indicate that our sensor indeed has great potential for detection of Aβ.

Comparison of the representative sensors for detection of Aβ protein.

| Method | Signal element | Detection range | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric | Au nanoparticles | 10.5 nM–313.5 nM | [58] |

| Au nanoparticles | 35 nM–700 nM | [59] | |

| Electrochemistry | Carbon nanotubes, Au nanoparticles and gelsolin-Au-Th bioconjugate | 0.2 nM–40 nM | [60] |

| Au nanoparticle on carbon electrode | 0.5 μM–10 μM | [61] | |

| Fluorescent | Resveratrol and graphene oxide | 0–200 μM | [62] |

| Polydopamine nanospheres | 20 nM–10000 nM | [63] | |

| Immunosensor with surface plasmon resonance | Au films and antibody | 0.02 nM–5 nM | [64] |

| Au substrate, Au nanoparticle, and antibody | 1 fg/mL–109 fg/mL | [65] | |

| THz metamaterial | Cu QTR arrays | 0.0001 mg/mL–10 mg/mL (23 nM–2.3 × 103 μM) | This work |

3 Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that a high-quality planar toroidal dipole response model can be excited from a symmetry-breaking centrosymmetric Taichi-like ring. To eliminate the quality-factor degradation caused by the polarization angle of incident THz light, we further designed a novel polarization-independent THz toroidal sensor by combining four Taichi-like rings into a cycle unit with a 90° rotation. The QTR sensor shows high-sensitivity sensing characteristics for the ultrathin analyte and different refractive indices. The optimized sensitivity of pure analytes under 4 μm coating thickness can numerically reach a high value of 258 GHz/RIU in the corresponding ∼1.345 THz frequency domain. Compared to reported THz metasurface sensors under the same condition, our structure has a higher sensitivity for 4 μm thick analytes. Then, we fabricated experimentally the sensor to verify our simulation results and demonstrated its attractive polarization-independent characteristics. Finally, it was successfully applied to the low-concentration detection of Aβ protein ranging from 0.0001 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL. These results indicate that the presented QTR metasurface has great sensing characteristics and promising applications for label-free biosensing.

Different biological samples have different physical properties such as refractive index. It is achievable to distinguish pure biological samples by using our all-metal THz metasurface sensors. For example, Chiben Zhang et al. has reported terahertz toroidal metasurface biosensor for the sensitive distinction of various lung cancer cells [66]. Jin Zhang et al. have shown a metamaterial-based biosensor for the recognition of molecule types of glioma cells [27]. However, it is limited to realizing biological sample detection in a hybrid system via using all-metal sensors due to the lack of specific binding surfaces. The functionalization of THz metasurface sensors by modifying and fixing special functional groups will be a very promising route for practical use.

Funding source: Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 20212BAB214056

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 11804174

Award Identifier / Grant number: 11904152

Award Identifier / Grant number: 12104203

Award Identifier / Grant number: 12264027

Award Identifier / Grant number: 61927813

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This work has been supported by the NSF of China (Grant No. 12264027; 12104203;11904152; 11804174; 61927813), Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 20212BAB214056).

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

[1] X. Yang, X. Zhao, K. Yang, et al.., “Biomedical applications of terahertz spectroscopy and imaging,” Trends Biotechnol., vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 810–824, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.04.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Q. Sun, Y. He, K. Liu, S. Fan, E. P. J. Parrott, and E. Pickwell-MacPherson, “Recent advances in terahertz technology for biomedical applications,” Quant. Imaging. Med. Surg., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 345–355, 2017. https://doi.org/10.21037/qims.2017.06.02.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] M. Danciu, T. Alexa-Stratulat, C. Stefanescu, et al.., “Terahertz spectroscopy and imaging: a cutting-edge method for diagnosing digestive cancers,” Materials, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 1519, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12091519.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Y. Peng, C. Shi, Y. Zhu, M. Gu, and S. Zhuang, “Terahertz spectroscopy in biomedical field: a review on signal-to-noise ratio improvement,” PhotoniX, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 12, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43074-020-00011-z.Search in Google Scholar

[5] D. Samanta, M. P. Karthikeyan, D. Agarwal, A. Biswas, A. Acharyya, and A. Banerjee, “Trends in terahertz biomedical applications,” in Generation, Detection and Processing of Terahertz Signals, A. Acharyya, A. Biswas, and P. Das, Eds., Singapore, Springer, 2022, pp. 285–299.10.1007/978-981-16-4947-9_19Search in Google Scholar

[6] Z. Yan, L. G. Zhu, K. Meng, W. Huang, and Q. Shi, “THz medical imaging: from in vitro to in vivo,” Trends Biotechnol., vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 816–830, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2021.12.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] E. Pickwell-MacPherson and V. P. Wallace, “Terahertz pulsed imaging--a potential medical imaging modality?” Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 128–134, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.07.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] K. A. Niessen, M. Xu, D. K. George, et al.., “Protein and RNA dynamical fingerprinting,” Nat. Commun., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1026, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08926-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] R. Liu, M. He, R. Su, Y. Yu, W. Qi, and Z. He, “Insulin amyloid fibrillation studied by terahertz spectroscopy and other biophysical methods,” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., vol. 391, no. 1, pp. 862–867, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.153.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] J. Yang, C. Tang, Y. Wang, et al.., “The terahertz dynamics interfaces to ion-lipid interaction confined in phospholipid reverse micelles,” Chem. Commun., vol. 55, no. 100, pp. 15141–15144, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9cc07598d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] X. Zheng and G. Gallot, “Dynamics of cell membrane permeabilization by saponins using terahertz attenuated total reflection,” Biophys. J., vol. 119, no. 4, pp. 749–755, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.05.040.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Z. Zhou, T. Zhou, S. Zhang, et al.., “Multicolor T-ray imaging using multispectral metamaterials,” Adv. Sci., vol. 5, no. 7, p. 1700982, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201700982.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] W. Xu, L. Xie, and Y. Ying, “Mechanisms and applications of terahertz metamaterial sensing: a review,” Nanoscale, vol. 9, no. 37, pp. 13864–13878, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7nr03824k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] M. Seo and H. R. Park, “Terahertz biochemical molecule-specific sensors,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 8, no. 3, p. 1900662, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201900662.Search in Google Scholar

[15] D. R. Smith, J. B. Pendry, and M. C. K. Wiltshire, “Metamaterials and negative refractive index,” Science, vol. 305, no. 5685, pp. 788–792, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1096796.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] N. K. Grady, J. E. Heyes, D. R. Chowdhury, et al.., “Terahertz metamaterials for linear polarization conversion and anomalous refraction,” Science, vol. 340, no. 6138, pp. 1304–1307, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1235399.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] H. Němec, P. Kužel, F. Kadlec, C. Kadlec, R. Yahiaoui, and P. Mounaix, “Tunable terahertz metamaterials with negative permeability,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 79, no. 24, p. 241108, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.79.241108.Search in Google Scholar

[18] W. Li and J. Valentine, “Metamaterial perfect absorber based hot electron photodetection,” Nano Lett., vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 3510–3514, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl501090w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] D. Schurig, J. J. Mock, B. J. Justice, et al.., “Metamaterial electromagnetic cloak at microwave frequencies,” Science, vol. 314, no. 5801, pp. 977–980, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1133628.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] W. Cai, U. K. Chettiar, A. V. Kildishev, and V. M. Shalaev, “Optical cloaking with metamaterials,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 224–227, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2007.28.Search in Google Scholar

[21] J. B. Pendry, L. Martín-Moreno, and F. J. Garcia-Vidal, “Mimicking surface plasmons with structured surfaces,” Science, vol. 305, no. 5685, pp. 847–848, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1098999.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] C. R. Simovski, P. A. Belov, A. V. Atrashchenko, and Y. S. Kivshar, “Wire metamaterials: physics and applications,” Adv. Mater., vol. 24, no. 31, pp. 4229–4248, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201200931.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] T. Chen, S. Li, and H. Sun, “Metamaterials application in sensing,” Sensors, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 2742–2765, 2012. https://doi.org/10.3390/s120302742.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] S. Shen, X. Liu, Y. Shen, et al.., “Recent advances in the development of materials for terahertz metamaterial sensing,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 2101008, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202101008.Search in Google Scholar

[25] X. Wu, B. Quan, X. Pan, et al.., “Alkanethiol-functionalized terahertz metamaterial as label-free, highly-sensitive and specific biosensor,” Biosens. Bioelectron., vol. 42, pp. 626–631, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2012.10.095.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] J. Qin, L. Xie, and Y. Ying, “A high-sensitivity terahertz spectroscopy technology for tetracycline hydrochloride detection using metamaterials,” Food Chem., vol. 211, pp. 300–305, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.05.059.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] J. Zhang, N. Mu, L. Liu, et al.., “Highly sensitive detection of malignant glioma cells using metamaterial-inspired THz biosensor based on electromagnetically induced transparency,” Biosens. Bioelectron., vol. 185, p. 113241, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2021.113241.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] R. Zhou, C. Wang, Y. Huang, et al.., “Label-free terahertz microfluidic biosensor for sensitive DNA detection using graphene-metasurface hybrid structures,” Biosens. Bioelectron., vol. 188, p. 113336, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2021.113336.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] A. Ahmadivand, B. Gerislioglu, R. Ahuja, and Y. K. Mishra, “Toroidal metaphotonics and metadevices,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 14, no. 11, p. 1900326, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201900326.Search in Google Scholar

[30] M. Gupta, Y. K. Srivastava, and R. Singh, “A toroidal metamaterial switch,” Adv. Mater., vol. 30, no. 4, p. 1704845, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201704845.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] M. Gupta and R. Singh, “Toroidal versus Fano resonances in high Q planar THz metamaterials,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 4, no. 12, pp. 2119–2125, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201600553.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Z. Song, Y. Deng, Y. Zhou, and Z. Liu, “Terahertz toroidal metamaterial with tunable properties,” Opt. Express, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 5792–5797, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.27.005792.Search in Google Scholar

[33] A. Ahmadivand, B. Gerislioglu, P. Manickam, et al.., “Rapid detection of infectious envelope proteins by magnetoplasmonic toroidal metasensors,” ACS Sens., vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 1359–1368, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.7b00478.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Y. Wang, Z. Han, Y. Du, and J. Qin, “Ultrasensitive terahertz sensing with high-Q toroidal dipole resonance governed by bound states in the continuum in all-dielectric metasurface,” Nanophotonics, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 1295–1307, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0582.Search in Google Scholar

[35] M. Pitschke, R. Prior, M. Haupt, and D. Riesner, “Detection of single amyloid β-protein aggregates in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s patients by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy,” Nat. Med., vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 832–834, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0798-832.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] J. P. Taylor, J. Hardy, and K. H. Fischbeck, “Toxic proteins in neurodegenerative disease,” Science, vol. 296, no. 5575, pp. 1991–1995, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1067122.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] A. Leuzy, N. Mattsson-Carlgren, S. Palmqvist, S. Janelidze, J. L. Dage, and O. Hansson, “Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease,” EMBO Mol. Med., vol. 14, no. 1, p. e14408, 2022. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202114408.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Y. Zhou, L. Liu, Y. Hao, and M. Xu, “Detection of Aβ monomers and oligomers: early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease,” Chem. Asian J., vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 805–817, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.201501355.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] I. Maezawa, H. S. Hong, R. Liu, et al.., “Congo red and thioflavin-T analogs detect Abeta oligomers,” J. Neurochem., vol. 104, no. 2, pp. 457–468, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04972.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] C. Heo, T. Ha, C. You, et al.., “Identifying fibrillization state of Aβ protein via near-field THz conductance measurement,” ACS Nano, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 6548–6558, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b08572.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] L. Xu, J. Xu, W. Liu, et al.., “Terahertz metal-graphene hybrid metamaterial for monitoring aggregation of Aβ16–22 peptides,” Sens. Actuators, B, vol. 367, p. 132016, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2022.132016.Search in Google Scholar

[42] X. Deng, Y. Shen, B. Liu, et al.., “Terahertz metamaterial sensor for sensitive detection of citrate salt solutions,” Biosensors, vol. 12, no. 6, p. 408, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12060408.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] B. Gerislioglu, A. Ahmadivand, and N. Pala, “Tunable plasmonic toroidal terahertz metamodulator,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 97, no. 16, p. 161405, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.97.161405.Search in Google Scholar

[44] C. Zhang, L. Liang, L. Ding, et al.., “Label-free measurements on cell apoptosis using a terahertz metamaterial-based biosensor,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 108, no. 24, p. 241105, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4954015.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Z. Zhang, H. Ding, X. Yan, et al.., “Sensitive detection of cancer cell apoptosis based on the non-bianisotropic metamaterials biosensors in terahertz frequency,” Opt. Mater. Express, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 659–667, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.8.000659.Search in Google Scholar

[46] M. Gupta, Y. K. Srivastava, M. Manjappa, and R. Singh, “Sensing with toroidal metamaterial,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 110, no. 12, p. 121108, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4978672.Search in Google Scholar

[47] R. Singh, W. Cao, I. Al-Naib, L. Cong, W. Withayachumnankul, and W. Zhang, “Ultrasensitive terahertz sensing with high-Q Fano resonances in metasurfaces,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 105, no. 17, p. 171101, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4895595.Search in Google Scholar

[48] M. Gupta and R. Singh, “Terahertz sensing with optimized Q/veff metasurface cavities,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 8, no. 16, p. 1902025, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201902025.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Q. Xie, G. X. Dong, B. X. Wang, and W. Q. Huang, “High-Q Fano resonance in terahertz frequency based on an asymmetric metamaterial resonator,” Nanoscale Res. Lett., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 294, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-018-2677-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] M. Chen, L. Singh, N. Xu, R. Singh, W. Zhang, and L. Xie, “Terahertz sensing of highly absorptive water-methanol mixtures with multiple resonances in metamaterials,” Opt. Express, vol. 25, no. 13, pp. 14089–14097, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.25.014089.Search in Google Scholar

[51] S. Chimon, M. A. Shaibat, C. R. Jones, D. C. Calero, B. Aizezi, and Y. Ishii, “Evidence of fibril-like β-sheet structures in a neurotoxic amyloid intermediate of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid,” Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., vol. 14, no. 12, pp. 1157–1164, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb1345.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] A. Lomakin, D. B. Teplow, D. A. Kirschner, and G. B. Benedek, “Kinetic theory of fibrillogenesis of amyloid β-protein,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 94, no. 15, pp. 7942–7947, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.15.7942.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] W. Wang and C. J. Roberts, “Protein aggregation – mechanisms, detection, and control,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 550, no. 1, pp. 251–268, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.08.043.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] M. Cuccioloni, V. Cecarini, L. Bonfili, et al.., “Enhancing the amyloid-β anti-aggregation properties of curcumin via arene-ruthenium(II) derivatization,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 23, no. 15, p. 8710, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158710.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] T. Sakata, R. Shiratori, and M. Kato, “Hydrogel-coated gate field-effect transistor for real-time and label-free monitoring of β-amyloid aggregation and its inhibition,” Anal. Chem., vol. 94, no. 6, pp. 2820–2826, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.1c04339.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] V. Romanucci, S. García-Viñuales, C. Tempra, et al.., “Modulating Aβ aggregation by tyrosol-based ligands: the crucial role of the catechol moiety,” Biophys. Chem., vol. 265, p. 106434, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpc.2020.106434.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] R. Sabaté, M. Gallardo, and J. Estelrich, “Temperature dependence of the nucleation constant rate in β amyloid fibrillogenesis,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 9–13, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2004.11.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Y. Zhou, H. Dong, L. Liu, and M. Xu, “Simple colorimetric detection of amyloid β-peptide (1–40) based on aggregation of gold nanoparticles in the presence of copper ions,” Small, vol. 11, no. 18, pp. 2144–2149, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201402593.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] C. Deng, H. Liu, M. Zhang, et al.., “Light-up nonthiolated aptasensor for low-mass, soluble amyloid-β40 oligomers at high salt concentrations,” Anal. Chem., vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 1710–1717, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03468.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Y. Yu, L. Zhang, C. Li, X. Sun, D. Tang, and G. Shi, “A method for evaluating the level of soluble β-amyloid(1–40/1–42) in Alzheimer’s disease based on the binding of gelsolin to β-amyloid peptides,” Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., vol. 53, no. 47, pp. 12832–12835, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.201405001.Search in Google Scholar

[61] M. Chikae, T. Fukuda, K. Kerman, K. Idegami, Y. Miura, and E. Tamiya, “Amyloid-β detection with saccharide immobilized gold nanoparticle on carbon electrode,” Bioelectrochemistry, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 118–123, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2008.06.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] X. P. He, Q. Deng, L. Cai, et al.., “Fluorogenic resveratrol-confined graphene oxide for economic and rapid detection of Alzheimer’s disease,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 6, no. 8, pp. 5379–5382, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1021/am5010909.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] L. Liu, Y. Chang, J. Yu, M. Jiang, and N. Xia, “Two-in-one polydopamine nanospheres for fluorescent determination of beta-amyloid oligomers and inhibition of beta-amyloid aggregation,” Sens. Actuators, B, vol. 251, pp. 359–365, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2017.05.106.Search in Google Scholar

[64] N. Xia, L. Liu, M. G. Harrington, J. Wang, and F. Zhou, “Regenerable and simultaneous surface plasmon resonance detection of Aβ(1−40) and Aβ(1−42) peptides in cerebrospinal fluids with signal amplification by streptavidin conjugated to an N-Terminus-Specific antibody,” Anal. Chem., vol. 82, no. 24, pp. 10151–10157, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac102257m.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[65] J. H. Lee, D. Y. Kang, T. Lee, S. U. Kim, B. K. Oh, and J. W. Choil, “Signal enhancement of surface plasmon resonance based immunosensor using gold nanoparticle-antibody complex for beta-amyloid (1-40) detection,” J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol., vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 7155–7160, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2009.1613.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] C. Zhang, T. Xue, J. Zhang, et al.., “Terahertz toroidal metasurface biosensor for sensitive distinction of lung cancer cells,” Nanophotonics, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 101–109, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0520.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2023-0010).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Structural color generation: from layered thin films to optical metasurfaces

- Research Articles

- Tunable localization of light using nested invisible metasurface cavities

- Spectral tuning of Bloch Surface Wave resonances by light-controlled optical anisotropy

- Tunable on-chip mode converter enabled by inverse design

- Fast tunable metamaterial liquid crystal achromatic waveplate

- Polarization-dependent phase-modulation metasurface for vortex beam (de)multiplexing

- Wide field of view and full Stokes polarization imaging using metasurfaces inspired by the stomatopod eye

- Dual-resonance sensing for environmental refractive index based on quasi-BIC states in all-dielectric metasurface

- Plasmonic spin induced Imbert–Fedorov shift

- Nonmechanical varifocal metalens using nematic liquid crystal

- High-sensitivity polarization-independent terahertz Taichi-like micro-ring sensors based on toroidal dipole resonance for concentration detection of Aβ protein

- Topologically-optimized on-chip metamaterials for ultra-short-range light focusing and mode-size conversion

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Structural color generation: from layered thin films to optical metasurfaces

- Research Articles

- Tunable localization of light using nested invisible metasurface cavities

- Spectral tuning of Bloch Surface Wave resonances by light-controlled optical anisotropy

- Tunable on-chip mode converter enabled by inverse design

- Fast tunable metamaterial liquid crystal achromatic waveplate

- Polarization-dependent phase-modulation metasurface for vortex beam (de)multiplexing

- Wide field of view and full Stokes polarization imaging using metasurfaces inspired by the stomatopod eye

- Dual-resonance sensing for environmental refractive index based on quasi-BIC states in all-dielectric metasurface

- Plasmonic spin induced Imbert–Fedorov shift

- Nonmechanical varifocal metalens using nematic liquid crystal

- High-sensitivity polarization-independent terahertz Taichi-like micro-ring sensors based on toroidal dipole resonance for concentration detection of Aβ protein

- Topologically-optimized on-chip metamaterials for ultra-short-range light focusing and mode-size conversion