Abstract

Coherent quantum optics, where the phase of a photon is not scrambled as it interacts with an emitter, lies at the heart of many quantum optical effects and emerging technologies. Solid-state emitters coupled to nanophotonic waveguides are a promising platform for quantum devices, as this element can be integrated into complex photonic chips. Yet, preserving the full coherence properties of the coupled emitter-waveguide system is challenging because of the complex and dynamic electromagnetic landscape found in the solid state. Here, we review progress toward coherent light-matter interactions with solid-state quantum emitters coupled to nanophotonic waveguides. We first lay down the theoretical foundation for coherent and nonlinear light-matter interactions of a two-level system in a quasi-one-dimensional system, and then benchmark experimental realizations. We discuss higher order nonlinearities that arise as a result of the addition of photons of different frequencies, more complex energy level schemes of the emitters, and the coupling of multiple emitters via a shared photonic mode. Throughout, we highlight protocols for applications and novel effects that are based on these coherent interactions, the steps taken toward their realization, and the challenges that remain to be overcome.

1 Introduction

Quantum optical research no longer focuses solely on fundamental demonstrations of the quantum nature of atoms, photons, or their interactions, but rather integrates these constituents into increasingly complex systems. These provide an ever-growing view of the rich realm of many-body quantum physics [1] and bring us closer to functional quantum technologies such as quantum networks [2], [3], [4] and, ultimately, quantum computers [5], [6].

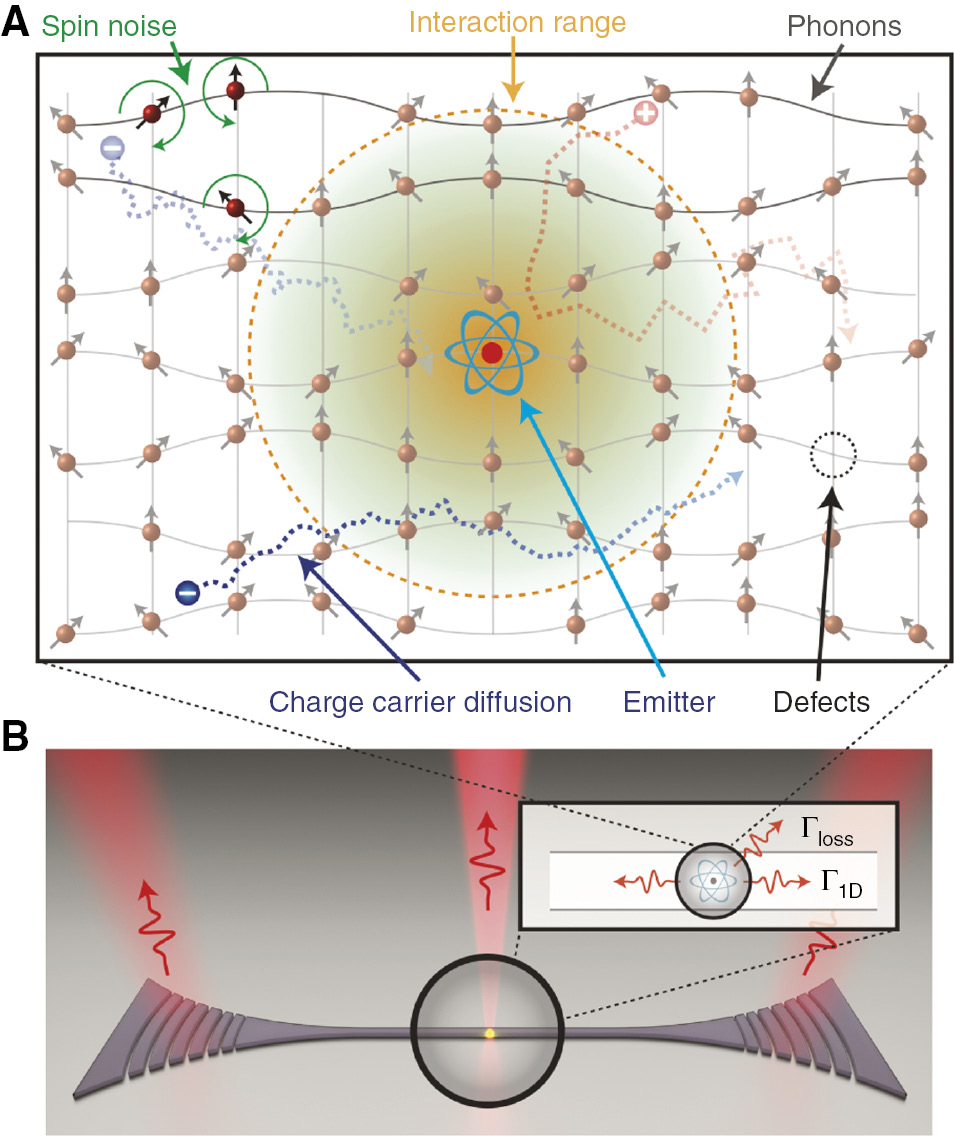

One basic element that has the potential to fulfill many of the functionalities required in complex, active quantum architectures is a quantum emitter coupled to a photonic waveguide, as sketched in Figure 1. Nanophotonic waveguides confine and guide light and reshape the emission from dipole sources to match their fundamental mode [7], [8], [9], and can be engineered to strongly suppress emission into free space [10], resulting in efficient emitter-photon coupling [11]. An emitter efficiently coupled to a waveguide can therefore act as a source of high-quality single photons [12], for example, for quantum information processing with linear optical systems [13], [14]. The strong confinement of light in waveguides also leads to the presence of a large longitudinal component of the electric field, and the interaction of this vector field with circular dipoles can result in unidirectional emission [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. These directional light-matter interactions enable the creation of chiral quantum optical elements such as optical isolators, single-photon routers, quantum logic gates, and even networks [20], [21].

The basic system considered in this review: a quantum emitter coupled to a quasi-one-dimensional photonic waveguide.

The coherence of this quantum system is degraded by the interaction of the emitter with the solid-state environment, as discussed in the text. (A) Here, sources of noise such as charge, spin, phonons, and nearby defects are schematically depicted. (B) Emission, in this system, occurs either into the guided modes, with a rate Γ1D, or is lost into other modes with a rate Γloss.

Spurred by this potential, researchers have, in the past few years, worked to couple a variety of quantum emitters to waveguides, including single organic molecules [22], [23], [24], [25], a variety of color centers in diamond [26], [27], [28], [29], atoms [30], [31], [32], [33], quantum dots (QDs) [9], and superconducting qubits [34]. These systems, with the exception of superconducting qubits and free-space Rydberg-atom quantum optics that are covered by the latter review, have, over the last decade, been brought to the nanoscale.

The challenge to interfacing solid-state emitters with nanophotonic waveguides is in keeping the ensuing light-matter interactions coherent. As sketched in Figure 1A, there are many possible sources of noise in solid-state systems, from ballistic or trapped charges near the emitter, to spin noise in the surrounding nuclear bath, to the coupling to phonons or to vibration in the vicinity of the emitter [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]. The methods implemented to overcome these processes depend on the type of quantum emitter and include, for example, the careful crystallization of the host matrix of single organic molecules [22], [45], embedding epitaxially grown QDs in a diode to shield them from electronic fluctuations [47], [48], using Purcell enhancement to overcome dephasing [26], [49], [50], and searching for better shielded defects within diamond [51].

Here, we review the current state of the art in coherent quantum optics in nanophotonic waveguides, focusing on quantum optical nonlinearities. We begin with the theoretical background that describes coherent quantum optics of two-level systems in one dimension, highlighting the important parameters and figures of merits associated with these interactions, and the corresponding experimental demonstrations. We then review higher order quantum optical nonlinearities, touching on effects that require multiple photons and extending beyond two-level systems, before concluding with a discussion of coherent quantum optics in multi-emitter systems.

2 Nonlinear response of a two-level system coupled to a waveguide

2.1 Transmission and reflection

Of the many theories developed to describe quantum light-matter interactions [52], the Green’s function formalism is particularly well suited to describe the coherent interaction of guided photons with two-level systems (TLSs) [53]. This formalism allows for a full quantum treatment of dispersive and absorbing open systems and therefore spans both plasmonic and dielectric waveguides and, importantly, can be extended to multi-emitter systems (Section 4). In this section, we briefly outline this formalism, focusing on measurable signatures of coherent light-matter interactions with TLSs embedded in one-dimensional waveguides.

The Hamiltonian describing the interaction of a TLS with light in a single photonic mode, in a reference frame rotating at the angular frequency of the light field ωP, is

where ΔP=ωP–ωA. The first term describes the TLS, whose transition energy is ħωA and whose coherences between the i and j levels are given by

The last term of Eq. (1) describes the light-matter interaction, which is mediated by the transition dipole of the emitter. Here, the dipole operator can be written in terms of the dipole matrix elements

First, however, it is instructive to consider solely the state of the emitter, using the reduced density matrix for the TLS

where the Lindblad operator for the single emitter system [55], [56]

accounts for both the decay and decoherence of the emitter. For the emitter-waveguide system, this operator has three nonzero terms: Γeg≡Γ, which is the spontaneous emission rate associated with the transition from |e〉 to |g〉, and Γee=Γgg≡Γdeph, which is the pure dephasing of the system through which it decoheres without undergoing a transition.

Equation (2) can be solved using the rotating wave approximation and by assuming Markovian dephasing processes to yield the steady-state

where Γ2=Γ/2+Γdeph and we have defined the Rabi frequency to be ΩP=d·E/ħ for the driving field amplitude at the position of the emitter

To understand how the emitter interacts with photons propagating through the waveguide, we return to Eq. (1), now writing the electric field operator as

and the negative frequency component of the field operator,

The dipole-projected Green’s function for a one-dimensional waveguide, where light propagates in the z direction, is [59], [60]

where kP is the wavenumber of the photonic mode. Here, we define the emitter-waveguide coupling efficiency β≡Γ1D/Γ as the emission rate into the guided mode Γ1D normalized by the total emission rate Γ=Γ1D+Γloss (c.f. inset to Figure 1B). Following some algebra, this equation for g(ri, rj) allows us to rewrite Eq. (6) in terms of the incident field

Equations (4), (5), and (8) allow us to quantify the light-matter interaction of the TLS with guided photons. The transmission through the waveguide, for example, is

The first term of this equation, which depends on the population of the excited state of the emitter, is typically thought to govern the incoherent interactions, while the second term depends on the atomic coherences and is therefore viewed as the source of the coherent interactions. This view is particularly attractive since

Such a separation is, however, relatively straightforward in the low-power and no-detuning limit, where we can use Eqs. (4) and (5) to rewrite the transmission as

where it is clear that, in the limit of no pure dephasing, all terms contribute. If we then define the fraction of coherent interactions to be βco≡Γ1D/2Γ2, we can rewrite the low-power transmittance as

where the first and second terms are the coherent and incoherent contributions.

More generally, the transmission expressed in terms of the system parameters is

Similarly, the reflection from the TLS is

and, in the absence of absorption, the losses due to the scattering of light out of the waveguide mode is simply S=1–T–R. Note that these equations have been derived for excitation by a weak, continuous wave beam, but they also hold for spectrally narrow single photons (in the limit of ΩP≪1) [61].

A clear signature of the coherent interaction between a TLS and an emitter can be found in the transmission (and reflection) signals [62]. For a perfect system (β→1, Γdeph→0) in the low-power limit (ΩP→0), all single photons are reflected, leading to a perfect extinction of the transmission ΔT=T(ΔP=±∞)–T(ΔP=0)=1. As is evident from Eq. (12), this extinction depends nonlinearly on the power, coupling efficiency, and dephasing rate of the emitter. Perfect extinction is not possible with tightly focused plane waves, where a theoretical maximum of ΔT=0.85 has been calculated [63]. Rather, perfect extinction in free space requires perfectly matching the dipole mode with the excitation beam, a notoriously difficult proposition that motivates the importance of nanophotonic platforms. Waveguides, as we noted earlier, both reshape the radiation pattern of dipoles to match their fundamental modes [7], [8] and are non-diffracting, meaning that these structures are particularly well suited to ideally interface with quantum emitters.

Coherent extinction has recently been observed in a variety of systems, as summarized in Figure 2 and Table 1. Multiple organic molecules have been coupled coherently to a single nanoguide, each of which has a near-lifetime-limited transition that can be addressed individually through spectral-spatial selection [22] (Figure 2A). Extinction up to ΔT≈ 0.09 has been reported for this system [23]. Likewise, ΔT≈ 0.18 has been measured for Ge vacancies, deterministically implanted in a diamond waveguide (Figure 2B) [28], and ΔT≈ 0.67 for InAs QDs embedded in a gated nanobeam waveguide [64] (Figure 2C). In all cases, the limiting factor has been the β of the systems [c.f. Eq. (12)]. For nanoguides, such as those used in the aforementioned experiments, the maximum achievable β depends on the confinement of the guided mode, which, in turn, is a function of the refractive index ratio between the waveguiding medium and its surrounding, and the geometrical size of the waveguide. These dependencies are plotted in Figure 2D, where β is semianalytically calculated for nanoguides with circular cross-sections, showing the largest possible β for the different quantum emitters.

![Figure 2: State-of-the-art coherent extinction with a variety of solid-state quantum emitters in differing nanoguide geometries, including (A) single organic molecules, (B) Ge defects in diamond, and (C) InAs quantum dots. Adapted from [22]], [[28], and [64], respectively. (D) Maximum achievable coupling coefficient β for cylindrical nanoguides of different core sizes and the refractive index contrast surrounding the core. The core size is parameterized by the unitless variable x=k2r, where k2 is the wavenumber of light in the bulk material of the core and r is the radius of the nanoguide. Achievable β-factors for the different solid-state quantum emitters are marked in red symbols (dashed red line denotes the optimal achievable β for a given refractive index contrast), as is the geometry for which the effective mode area is equal to the scattering cross-section of an emitter (dashed blue line).](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0126/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2019-0126_fig_002.jpg)

State-of-the-art coherent extinction with a variety of solid-state quantum emitters in differing nanoguide geometries, including (A) single organic molecules, (B) Ge defects in diamond, and (C) InAs quantum dots. Adapted from [22]], [[28], and [64], respectively. (D) Maximum achievable coupling coefficient β for cylindrical nanoguides of different core sizes and the refractive index contrast surrounding the core. The core size is parameterized by the unitless variable x=k2r, where k2 is the wavenumber of light in the bulk material of the core and r is the radius of the nanoguide. Achievable β-factors for the different solid-state quantum emitters are marked in red symbols (dashed red line denotes the optimal achievable β for a given refractive index contrast), as is the geometry for which the effective mode area is equal to the scattering cross-section of an emitter (dashed blue line).

State-of-the-art coherent light-matter interactions with solid-state quantum emitters coupled to nanophotonic waveguides.

| System | Extinction | Linewidtha | g2 (0)b | Details | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atoms coupled to photonic waveguides | |||||

| Cs-nanoguide | 0.01 | 5.8 (5.8) MHz | – | More than 2000 resonantly coupled emitters | [30], [65] |

| Cs-PhCW | 0.25 | 15 (4.6) MHz | – | Mean number of coupled atoms is 3; observation of superradiance | [33] |

| Rb-nanoguide | 0.20 | 6.1 (6.1) MHz | – | 1-6, mean number of coupled atoms; observation of superradiance | [66] |

| Rb-PhCC | – | 53 MHz | 0.12(4.1) | Nanophotonic control of photon phase | [67] |

| Defect centers in diamond | |||||

| GeV-PhCW | 0.18 | 73(26) MHz | <0.08(1.1) | Coherent nonlinearity at the single-photon level | [28] |

| SiV-PhCW | 0.38 | 590(90) MHz | <0.15(1.5) | Two emitters remotely entangled by Raman transitions | [26] |

| SiV-PhCC | >0.95 | 4.6 GHz | 0.23 | Two Si vacancies, near-field-coupled inside a single cavity | [68] |

| InAs QDs | |||||

| QD-nanobeam | 0.66 | 1.2(0.9) GHz | <0.01 | Charge-stabilized and tunable by a diode | [12], [64] |

| QD-PhCW | 0.07–0.35 | 1.1–4(0.9) GHz | <0.01(1.15) | Coherent nonlinearity at the single photon level | [69], [70] |

| QD-PhCW | 0.85 | 1.36(1.22) GHz | (6) | Charge-stabilized and tunable by a diode | [71] |

| QD-microcavity | – | 0.28(0.28) GHz | (25–80) | Charge-stabilized in a μ-pillar or μ-cavity diode | [72], [73] |

| Organic molecules | |||||

| DBT-nanoguide | 0.07–0.09 | 30(30) MHz | <0.01 | Observation of up to 5000 single molecules coupled to the waveguide | [22], [23] |

| DBT-microcavity | 0.99 | 40(40) MHz | 0.1(21) | Measured g2(0) limited by timing-resolution of the detectors | [74] |

Atoms are included for completeness.

PhCW, Photonic crystal waveguide; PhCC, photonic crystal cavity.

aNatural linewidth, which may be Purcell-enhanced, is given in brackets.

bBunching value observed in coherent transmission experiments is given in brackets.

Alternatively, β could be increased through the use of photonic resonators, or highly structured systems such as photonic crystals. The generalization of Eqs. (12) and (13) to account for cavity Purcell enhancement is relatively straightforward and leads to the observation of Fano-like lineshapes in the transmission, as the phase of the photons that do not interact with the emitter is now dependent on their spectral detuning from the resonance [75]. Coherent and deterministic light-matter interactions have, in fact, recently been demonstrated with a single molecule [74], defect centers [68], and QDs [72] in microcavities, where a ΔT≈ 0.99 has been observed, albeit at the cost of operational bandwidth. Here, the emission into the photonic mode was Purcell enhanced, increasing the emission rate in the desired channel relative to other radiative channels and the dephasing rate. The nonlinear dependence of ΔT has been observed for both molecules [23] and QDs [64], [69], [70], where a critical flux of ≈1 photon per lifetime was found to saturate the emitter, as shown in Figure 3A, since it can only scatter a single photon at a time. In a complementary fashion, the phase of a scattered photon can be tuned, as the presence of a TLS fundamentally changes the response of a nanophotonic system, as shown in Figure 3B [67]. Altogether, these results hint at the power of coherent quantum optics in integrated photonic systems.

![Figure 3: Nonlinear dependence of ∆T and the presence of a TLS fundamentally changes the response of a nanophotonic system.(A) The coherent nonlinear response of a TLS is seen in the power-dependent extinction of the transmitted light, which vanishes as the photon flux increases beyond one photon per lifetime (top panel). As the same time, the bandwidth of the transition begins to power-broaden (bottom panel), signifying the loss of coherence in the light-matter interactions. Adapted from [64]. (B) An efficiently coupled TLS, here an atom evanescently coupled to a photonic crystal cavity (top inset), can also modulate the phase of the scattered photons. In fact, markedly different responses are seen in the presence of the emitter (blue symbols) and in its absence (yellow symbols). The bottom inset shows the corresponding normalized count rate in one arm of an interferometer, relative to the expected cavity response (blue curve). Adapted from [67].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0126/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2019-0126_fig_003.jpg)

Nonlinear dependence of ∆T and the presence of a TLS fundamentally changes the response of a nanophotonic system.

(A) The coherent nonlinear response of a TLS is seen in the power-dependent extinction of the transmitted light, which vanishes as the photon flux increases beyond one photon per lifetime (top panel). As the same time, the bandwidth of the transition begins to power-broaden (bottom panel), signifying the loss of coherence in the light-matter interactions. Adapted from [64]. (B) An efficiently coupled TLS, here an atom evanescently coupled to a photonic crystal cavity (top inset), can also modulate the phase of the scattered photons. In fact, markedly different responses are seen in the presence of the emitter (blue symbols) and in its absence (yellow symbols). The bottom inset shows the corresponding normalized count rate in one arm of an interferometer, relative to the expected cavity response (blue curve). Adapted from [67].

2.2 Nonlinearity and photon statistics

A more profound signature of the coherent nonlinearity of the TLS can be found in the ensuing photon statistics, which explicitly demonstrates the different response of the TLS to single and multiple incident photons. This is seen in the normalized second-order correlation function

where

In the limit of no pure dephasing (Γ2→Γ/2), this equation converges to that of Chang et al. [76].

The highly nonlinear response of a TLS is encoded into the photon statistics of the transmitted light. A signature of this nonlinearity is the photon bunching observed in g(2)(0), which we plot in Figure 4A as a function of both β and the relative dephasing rate Γdeph/Γ. The strong photon bunching is observed when β→1 and Γdeph→0. Here, g(2)(0)→∞, as T→0 (c.f. Section 2.1), meaning that all single-photon components of the incident coherent state are reflected. Conversely, in transmission, the coherent superposition of the zero and multi-photon components results in photon bunching. This photon bunching has been observed with both QDs [69], [70], [71] and Ge vacancy centers [28] coupled to waveguides, with peak values of g(2)(0) ranging from 1.1 to 6. Higher values have recently been reported using a variety of emitters coupled to resonators, as summarized in Table 1. The photon statistics can be actively manipulated, for example, to alternate between bunching and antibunching, using the higher order nonlinearity of the emitter [77] or by modulating the local phase of the quantum interference [78], [79].

![Figure 4: Two-photon correlations for a weak coherent-state scattering from a TLS embedded in a waveguide.(A) g2(0) as a function of both β and Γdeph [Eq. (15)], showing a strong photon bunching for well-coupled emitters with small pure dephasing. (B) Using an integrated nanophotonic waveguide cavity coupled to a Si vacancy in diamond, researchers were able to observe a g2(0)≈1.5. Adapted from [26].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0126/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2019-0126_fig_004.jpg)

Two-photon correlations for a weak coherent-state scattering from a TLS embedded in a waveguide.

(A) g2(0) as a function of both β and Γdeph [Eq. (15)], showing a strong photon bunching for well-coupled emitters with small pure dephasing. (B) Using an integrated nanophotonic waveguide cavity coupled to a Si vacancy in diamond, researchers were able to observe a g2(0)≈1.5. Adapted from [26].

This multi-photon transmission is comprised of two components: one in which the two photons are uncorrelated and therefore scatter independently, and one where the photons are correlated and cannot be considered independently [63], [80], [81], [82]. Shen and Fan derived analytic formulas for both components using a scattering matrix approach, and later using the input-output formalism [83]. Subsequently, Ramos and Garcia-Ripoll proposed an experimental method to measure the single- and two-photon scattering matrices using weak coherent beams [84].

A part of the correlated component of the two-photon wavepacket whose shape does not change as a result of scattering from the TLS exists. This component acts like a “quantum soliton” and is known as a photon-photon bound state. This is much like photon-emitter bound states, which are characterized by the entanglement between the light and matter degrees of freedom [85], [86], a hallmark of polaritonics [87]. The work on photonic bound states was generalized to higher number multi-photon bound states [88] and to their spectral and temporal signatures in structured photonic environments [89]. Experimental signatures of the correlated components of two [90] and three [91], [92] photon scattering events were recently reported with Rydberg atoms, but an unambiguous observation of a photonic bound state is, to date, missing.

The highly nonlinear coherent scattering of guided photons from single emitters, and the ensuing strong correlations of photon-photon bound states, constitute a valuable quantum resource and have played a central role in recent proposals. The large disparity between the response of the emitter to single- and two-photon inputs can form the basis for a photon sorter, allowing for the realization of quantum nondemolition measurements [93] and for the creation of a Bell-State analyzer and controlled-sign gate [94]. This latter proposal may benefit from chiral coupling, meaning that all photons scatter in a single (forward) direction [21]. Interestingly, if this coupling could be made asymmetric but not perfectly directional, then this passive two-level nonlinearity has been predicted to act as a few-photon diode [95].

3 Nonlinearities of multilevel systems

In analogy to classical optics, there are a host of quantum optical nonlinearities beyond the interaction of photons with a TLS described above. These higher order quantum nonlinearities result from (i) the presence of multiple photons of different frequencies or (ii) a richer energy level structure of the emitter, and cannot be described by a perturbative susceptibility tensor like classical nonlinearities. In this section we describe these effects and highlight recent efforts to observe them in nanophotonic waveguides.

3.1 Dressed two-level systems

TLSs can coherently mediate the interaction between two different photons that, unlike the scenario described in Section 2, can be frequency-detuned. The resulting multi-photon nonlinear effects were first explored by Wu, Ezekiel, Duckloy, and Mollow in 1977, who measured the transmission of a weak probe beam through a large ensemble of sodium atoms in the presence of a strong excitation laser [96]. Because of the weak light-matter interactions in these initial experiments, they were conducted using large ensembles of atoms and with intense control beams. In fact, 30 years would pass before technological progress enabled the observation of these nonlinearities at the single-photon single-emitter level, as we discuss below, when spectra such as those shown in the right panel of Figure 5A were recorded using a single molecule [23], [97].

![Figure 5: Coherent quantum optical nonlinearities in dressed two-level systems.(A) The transmission spectra of photons scattering from a single organic molecule embedded in a nanoguide evolves nonlinearly as a function of the strength of a control beam with Rabi frequency Ωpmp [23]. The features of the red and orange curves can be understood in terms of the three available transitions between the states of the system, as shown to the left; each manifold of states is described by the state of the TLS and the photon number, here |e〉 or |g〉 and |m〉, respectively, and the level splitting is given by the generalized Rabi frequency ΩpmpG=Δpmp2+Ωpmp2.$\Omega _{{\rm{pmp}}}^{\rm{G}} = \sqrt {\Delta _{{\rm{pmp}}}^2 + \Omega _{{\rm{pmp}}}^2} .$ Here, a Stark shift of the resonance (red), a coherent energy transfer between the signal and control photons (green), and a coherent amplification of the signal photons (blue) are observed. (B) The nonlinear dependence of the coherent extinction and amplification as a function of control beam strength. Adapted from [23]. (C) Four-wave mixing observed using a single organic molecule as the nonlinear medium. This nonlinear signal manifests at twice the beat frequency (ii) of the scattered signal (i). Adapted from [97].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0126/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2019-0126_fig_005.jpg)

Coherent quantum optical nonlinearities in dressed two-level systems.

(A) The transmission spectra of photons scattering from a single organic molecule embedded in a nanoguide evolves nonlinearly as a function of the strength of a control beam with Rabi frequency Ωpmp [23]. The features of the red and orange curves can be understood in terms of the three available transitions between the states of the system, as shown to the left; each manifold of states is described by the state of the TLS and the photon number, here |e〉 or |g〉 and |m〉, respectively, and the level splitting is given by the generalized Rabi frequency

The physics underlying these spectra can be understood in terms of the three available transitions of the dressed state picture [98], where the bare states of the emitter hybridize with the manifold of light states, as shown in the left panel of Figure 5A. First, the emitter resonance, which is observed as an extinction of the transmission as in Section 2.1, is AC-Stark shifted by the presence of pump photons (red arrows). Second, when the pump and signal are only slightly detuned, the emitter can mediate the transfer of photons between the two beams, which appears as a kink in the transmission spectra (corresponding to the green transition). Finally, a stimulated process that requires two pump photons can coherently amplify the signal beam without the need for population inversion, resulting in the bump of the transmission signal (corresponding to the blue transition). A theoretical model, based on the optical Bloch equations, accurately reproduces these complex spectra [99], [100].

Initially, observing these multicolor nonlinear effects with single emitters proved challenging, because of the low probability of each photon interacting with an emitter in bulk. These constraints were first overcome using a combination of sensitive lock-in techniques and ultra-strong pump fields, to observe the signatures of these nonlinearities at the 10−5 level, first in the absorption [101] and then in the transmission [102] of a single QD in a bulk medium. Maser et al. improved this signal by three orders of magnitude by focusing tightly on a single organic molecule with a transform-limited transition, embedded in a thin organic matrix. Using this same platform, researchers were then able to observe these multicolor nonlinearities mediated by a single organic molecule coupled to a waveguide on a photonic chip [23], as shown in Figure 5B. Here, a clear nonlinear dependence of both the extinction and coherent amplification signals on the detuned pump photons is seen. Note, however, that even in this most recent experiment the extinction peaks at ΔT≈0.1 because of a weak molecule-waveguide coupling of only β=0.08. Regardless, this increased sensitivity both drastically reduced the amount of pump photons needed to observe these effects and allowed for the observation of additional nonlinear effects such as the four-wave mixing shown in Figure 5C [97]. Additional nonlinear frequency conversion processes have been predicted, but not yet observed, for strong driving fields and sufficiently strong coupling [103].

Experimentally, the current challenge is to reach the regime where these multicolor nonlinearities can be deterministically observed, and perhaps exploited to control light-matter interactions at the single-photon level. This requires that the light-matter coupling efficiency approaches unity while maintaining a fully coherent interaction (i.e. Γdeph=0), further motivating the use of structured nanophotonic waveguides and resonators.

3.2 Three- and four-level emitters

Although we often approximate quantum emitters as TLSs, they may actually have a much richer energy level structure that gives rise to new coherent and nonlinear quantum optical effects. In recent years, there have been many theoretical studies on the use of waveguides to enhance and exploit these effects, laying out the framework for future experiments.

A prototypical example of such a coherent, multilevel quantum optical nonlinearity is electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT). EIT occurs when, in the presence of a control field, destructive quantum interference between two transitions of a three-level system (c.f. Figure 6A) prevents absorption of a weak signal field [104]. The coherent control of quantum absorption enables, for example, the storage and retrieval of quantum states, a crucial requirement for emergent quantum technologies [107]. In this and other similar demonstrations, the low emitter-photon interaction probabilities necessitated the use of dense atomic ensembles, as was also the case when the atoms were weakly coupled to a waveguide [108], [109], [110]. Using waveguides to enhance the emitter-photon interaction can bring EIT to the single-photon and single-emitter level [106], [111], and such a system could form the basis for a single-photon all-optical switch [112].

![Figure 6: (A) Generic Ʌ-type scheme (left) and spectrum (right) for EIT where a probe field of frequency ωP and control field of frequency ωC interact with a quantum emitter. In the presence of the control beam transition |1〉→|3〉 is inaccessible and hence the absorption spectrum sharply falls to 0 on resonance. Adapted from [104]. (B) Schematic diagram of a single-photon transistor based on a three-level emitter. The storage of a gate pulse containing zero or one photon conditionally spin-flips the state of the emitter, depending on the photon number. A subsequent incident signal field is then either transmitted or reflected depending on the state of the emitter. Adapted from [76]. (C) Example of photonic cluster state generation by sequential scattering from a multilevel emitter. In the top panel, three un-entangled photons sequentially scatter from an emitter, creating a three-photon matrix product state. In the bottom panel, four photons scatter from the emitter. After the fourth photon scatters, the first and third photons are re-scattered, creating a two-dimensional projected entangled pair state. Adapted from [105]. (D) Calculated two-photon spatial probability distribution after the scattering of two photons off a driven three-level emitter (energy-level scheme shown in inset). In the low-loss limit (i.e. γ3≈0), the two-photon state is delocalized. As γ3 increases, the behavior of the driven system begins to resemble that of a two-level emitter. Adapted from [106].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0126/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2019-0126_fig_006.jpg)

(A) Generic Ʌ-type scheme (left) and spectrum (right) for EIT where a probe field of frequency ωP and control field of frequency ωC interact with a quantum emitter. In the presence of the control beam transition |1〉→|3〉 is inaccessible and hence the absorption spectrum sharply falls to 0 on resonance. Adapted from [104]. (B) Schematic diagram of a single-photon transistor based on a three-level emitter. The storage of a gate pulse containing zero or one photon conditionally spin-flips the state of the emitter, depending on the photon number. A subsequent incident signal field is then either transmitted or reflected depending on the state of the emitter. Adapted from [76]. (C) Example of photonic cluster state generation by sequential scattering from a multilevel emitter. In the top panel, three un-entangled photons sequentially scatter from an emitter, creating a three-photon matrix product state. In the bottom panel, four photons scatter from the emitter. After the fourth photon scatters, the first and third photons are re-scattered, creating a two-dimensional projected entangled pair state. Adapted from [105]. (D) Calculated two-photon spatial probability distribution after the scattering of two photons off a driven three-level emitter (energy-level scheme shown in inset). In the low-loss limit (i.e. γ3≈0), the two-photon state is delocalized. As γ3 increases, the behavior of the driven system begins to resemble that of a two-level emitter. Adapted from [106].

Other coherent effects in three-level systems can be used to control the transport of photons. Population inversion of a single molecule, for example, allowed it to act as a quantum optical transistor [113], [114], coherently attenuating or amplifying a stream of photons. Interestingly, it is possible to form an optical transistor using a three-level Ʌ system without the need for population inversion. Rather, the coherent reflection and transmission outlined in Section 2.1 can be used, in conjunction with a gate pulse that effectively couples or decouples the emitter from the waveguide, bringing the transistor to the single-photon level if the emitter is efficiently coupled to the photonic mode [76], [111] (c.f. Figure 6B). Similarly, control over the state of a ladder-type emitter coupled to a waveguide can switch, or even impart a π phase shift, to a guided photon [115]. Theories of the interaction of a few photons with three (or higher) level emitters predict the generation, or even engineering, of entangled photonic states. For example, two distinguishable photons can be entangled as they scatter from a ladder-type emitter, with the degree of entanglement depending on the spectral content of the photons [116]. The subsequent scattering of additional photons could thus be used to create large photonic entangled states, as shown in Figure 6C. The controlled rescattering of selected photon pairs from the entangled chain would create a photonic cluster state [105], which is a required resource in one-way quantum computating architectures [117].

Photonic bound states (c.f. Section 2.2) are also created when few-photon coherent states scatter from multilevel emitters [118]. In contrast to the scattering from two-level emitters, the presence of additional levels provides a route to the controlled shaping of the bound state. Driving a resonance of a Ʌ-type emitter, for example, can delocalize the two-photon wavepacket formed as the pair of photons scatter from the second transition (Figure 6D), paving a route toward control of the temporal properties of two-photon wavepackets [106]. Similarly, in an N-level emitter, multi-photon bound states can be made to destructively interfere with the standard multi-photon transmission, effectively suppressing multi-photon transmission and leading to a photonic blockade without the need for a cavity [88].

4 Nonlinear response of coupled multi-emitter systems

One of the most difficult and potentially most rewarding challenges in modern quantum optics is the scaling of individual elements into more complex quantum systems. This section covers recent works on multi-emitter waveguide quantum electrodynamics (QED), the vast majority of which are theoretical in nature, and which reflect both the difficulty and the reward of this undertaking.

Practically, the task is that the emitters of such a system simultaneously fulfill the following requirements: (i) They must all couple to the same guided mode, and in general this coupling should be efficient. (ii) The emitters should all interact coherently with passing photons (i.e. Γdeph≈0, c.f. Section 2.1). (iii) The emitters should emit at a similar transition frequency and have similar linewidths. (iv) Ideally, the emitters could be individually addressed such that their relative coupling can be controlled (e.g. by local electrical gating).

As we outlined in Section 2, conditions (i) and (ii) have been met for a single emitter coupled to a waveguide, and the current experimental challenges lie in meeting criteria (iii) and (iv). First efforts in this direction involved the entanglement of two implanted Si-vacancy defects coupled to a single waveguide, first using a remote Raman control scheme [26] and then directly via strain tuning [119]. A signature of the entanglement between the two emitters was observed in their photon correlations. Similarly, superradiance has been observed using ensembles with a mean number of atoms ≤6 coupled to waveguide [33], [66], although here the emitters could not be individually addressed. In contrast, microelectrodes were shown to Stark-shift the resonance of many individual molecules coupled to a nanoguide [120], [121] (see Figure 7A). These experiments demonstrate that an efficient and controllable coupling of multiple solid-state emitters on a photonic chip is within reach [123].

![Figure 7: (A) Stark tuning of many organic molecules found within a single confocal excitation spot, as shown in the inset. Spectra taken at different Stark voltages demonstrate that it is possible to tune multiple emitters into resonance with one another on a photonic chip. Adapted from [120]. (B) Absorption spectrum calculated for a chain of well-coupled N emitters (β=0.99) arranged at arbitrary positions about a regular lattice spaceing L=2.75 in a nanoguide (see inset). As the number of emitters increases (dark to light hues), normal-mode splitting is observed, while for N=10 narrow peaks near zero detuning Δ=0 emerge because of the presence of subradiant modes. Adapted from [59]. (C) Reflection spectra for 20 atoms interacting through the guided modes of an unstructured waveguide. The dashed blue line represents a regular separation between the atoms of λ/2. The orange curves show 10 different spectra obtained by randomly placing the atoms along the nanostructure. Adapted from [60]. (D) Nonlinear optical switch based on four-level emitters coupled to a fiber. The timing sequence for the probe, control, and switch fields (right) and the corresponding level scheme of the emitters (center). Left: In the absence of the switch field, the probe field is largely transmitted through the fiber (red data). A strong suppression of the transmission is observed when the switch field is on (blue data). Adapted from [122].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0126/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2019-0126_fig_007.jpg)

(A) Stark tuning of many organic molecules found within a single confocal excitation spot, as shown in the inset. Spectra taken at different Stark voltages demonstrate that it is possible to tune multiple emitters into resonance with one another on a photonic chip. Adapted from [120]. (B) Absorption spectrum calculated for a chain of well-coupled N emitters (β=0.99) arranged at arbitrary positions about a regular lattice spaceing L=2.75 in a nanoguide (see inset). As the number of emitters increases (dark to light hues), normal-mode splitting is observed, while for N=10 narrow peaks near zero detuning Δ=0 emerge because of the presence of subradiant modes. Adapted from [59]. (C) Reflection spectra for 20 atoms interacting through the guided modes of an unstructured waveguide. The dashed blue line represents a regular separation between the atoms of λ/2. The orange curves show 10 different spectra obtained by randomly placing the atoms along the nanostructure. Adapted from [60]. (D) Nonlinear optical switch based on four-level emitters coupled to a fiber. The timing sequence for the probe, control, and switch fields (right) and the corresponding level scheme of the emitters (center). Left: In the absence of the switch field, the probe field is largely transmitted through the fiber (red data). A strong suppression of the transmission is observed when the switch field is on (blue data). Adapted from [122].

Coupling quantum emitters with waveguides has been the focus of intense theoretical studies in recent years, resulting in prediction of both emergent many-body phenomena and new protocols for quantum information technology. This is already exemplified in two-emitter systems, which, even when coupled to a lossy waveguide, can result in sub- and super-radiant states and allow for two-qubit gates [124] and entanglement generation [125], [126]. Conversely, the high efficiency with which individual solid-state emitters can couple to a waveguide allows for the generation of Bell states [127], the entanglement and coupling of qubits that operate at vastly different frequencies, such as superconducting qubits with single molecules [128] or QDs [129]. Similarly, the input-output formalism was used to study quantum interference and photon statistics in a two-qubit system, demonstrating the complex dynamics that result from the quantum jumps of the emitters [130].

Concurrently, frameworks describing photonic transport through waveguides coupled to many emitters have been developed. Models focusing on specific aspects of this transport have quantified both the photon-photon [131] and emitter-emitter [132] entanglement that is generated as photons interact with the emitters, showing that this entanglement is more robust and efficient in chiral geometries. Interestingly, researchers have predicted that both chiral geometries [133] and stronger photonic correlations [134] lead to lower propagation losses, even if the emitters are weakly coupled to the waveguide or in the presence of disorder. Scattering from multiple emitters can also give rise to complex Fano shapes in the transmission and reflection spectra [135], providing a new route toward the control of photon statistics [79]. At the same time, efficient multiple scattering events between the emitters have been predicted to allow for normal mode-splitting without the need for cavities, and for the emergence of localized excitations [59] (c.f. Figure 7A) and “fermionic” subradiant modes that repel one another [136].

Many different effects and geometries of one-dimensional multi-emitter systems have been modeled. These include the addition of evanescent emitter-emitter coupling for closely spaced emitters [59], [137] and the inclusion of different decoherence mechanisms and inhomogeneous broadening [110]. Likewise, Pivovarov et al. developed a general microscopic model to describe single-photon scattering from a chain of multilevel emitters that describes both ordered and disordered geometries, and including both elastic and inelastic scattering channels [138]. Das et al., meanwhile, modeled the dynamics and amplitudes of the scattering of photons from multilevel emitters in the low excitation limit, working in the Heisenberg picture [139]. In this same low-excitation regime

where zero dephasing is also assumed. Here, the superscripts i and j refer to specific emitters, Γ′ is the rate of emission into the non-guided modes, and gij is the dipole-projected Green’s function as defined in Eq. (7). Note, however, that in this case gij controls the interactions between the emitters, which can be either dispersive or dissipative, depending on whether the real or imaginary component of G(ri, rj) dominates. The general nature of this approach means that it can be applied to a variety of nanophotonic structures, including emitter chains in unstructured waveguides, cavities, and photonic crystals, as was done in [60] (Figure 7B). Protocols, based on these theories, have begun to emerge, including schemes for quantum computation [6] and the efficient generation of multi-photon states [140].

The large nonlinearity inherent to quantum emitters manifests in novel fashion when many multilevel emitters are coupled via waveguides. Emitters in the EIT configuration [141], for example, can exhibit a giant Kerr nonlinearity [142]. Using a hollow-core photonic crystal fiber as a waveguide, to which they coupled a large ensemble of Rydberg atoms, researchers were able to exploit this Kerr nonlinearity for few-photon switching [122] (Figure 7C). A recent theoretical treatment of this system predicts that, in the ideal case, single-photon switching is possible, and studies the nonlinear evolution of two-photon wavepacket (c.f. Section 2.2) [143]. Photons traveling through such a multi-emitter system have also been predicted to crystalize, forming fermionic excitations that repel one another and providing an additional route to the creation of a pure single-photon source and enabling the study of complex quantum phase transitions [144]. Interestingly, the long-range interactions in such multi-emitter-waveguide systems are expected to give rise to nonlocal optical nonlinearities [145], providing yet another route to the creation of photonic bound states [146].

5 Conclusions and outlook

Advances in the growth and preparation of solid-state emitters and nanofabrication protocols have, in recent years, brought coherent light-matter interactions to quantum photonic chips. For single-emitter systems, these advances have allowed for the observation of a variety of nonlinear optical effects at, or near, the single-photon level, bringing a host of classical and quantum functionalities tantalizingly within reach. At the same time, increasingly complex theories have been developed that model the coupling of multiple emitters via long-range, waveguide-mediated interactions. Such multi-emitter systems have been predicted to support exotic new quantum phases of light and may enable efficient new quantum information technologies. Experimentally, we stand at the cusp of this exciting field, with multi-emitter photonic architectures just around the corner.

Acknowledgments

P.L., H.J., S.F.S, and N.R. gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Danish National Research Foundation (Center of Excellence Hy-Q) and the Europe Research Council (ERC Advanced Grant SCALE). S.G. and V.S. acknowledge financial support from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, co-funded by the European Commission (project RouTe), project number 13N14839 within the research program “Photonik Forschung Deutschland”.

References

[1] Noh C, Angelakis DG. Quantum simulations and many-body physics with light. Rep Prog Phys 2017;80:016401.10.1088/0034-4885/80/1/016401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Kimble HJ. The quantum internet. Nature 2008;453:1023–30.10.1038/nature07127Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Ritter S, Nölleke C, Hahn C, et al. An elementary quantum network of single atoms in optical cavities. Nature 2012;484: 195–200.10.1038/nature11023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Lodahl P. Quantum-dot based photonic quantum networks. Quant Sci Tech 2018;3:013001.10.1088/2058-9565/aa91bbSearch in Google Scholar

[5] DiVincenzo DP, Bacon D, Kempe J, Burkard G, Whaley KB. Universal quantum computation with the exchange interaction. Nature 2000;408:339–42.10.1038/35042541Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Paulisch V, Kimble HJ, González-Tudela A. Universal quantum computation in waveguide QED using decoherence free subspaces. New J Phys 2016;18:043041.10.1088/1367-2630/18/4/043041Search in Google Scholar

[7] Chang DE, Sørensen AS, Hemmer PR, Lukin MD. Quantum optics with surface plasmons. Phys Rev Lett 2006;97: 053002.10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.053002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Friedler I, Sauvan C, Hugonin JP, Lalanne P, Claudon J, Gèrard JM. Solid-state single photon sources: the nanowire antenna. Opt Express 2009;17:2095–110.10.1364/OE.17.002095Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Lodahl P, Mahmoodian S, Stobbe S. Interfacing single photons and single quantum dots with photonic nanostructures. Rev Mod Phys 2015;87:347–400.10.1103/RevModPhys.87.347Search in Google Scholar

[10] Wang Q, Stobbe S, Lodahl P. Mapping the local density of optical states of a photonic crystal with single quantum dots. Phys Rev Lett 2011;107:167404.10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.167404Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Arcari M, Söllner I, Javadi A, et al. Near-unity coupling efficiency of a quantum emitter to a photonic crystal waveguide. Phys Rev Lett 2014;113:093603.10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.093603Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Kiršanskė G, Thyrrestrup H, Daveau RS, et al. Indistinguishable and efficient single photons from a quantum dot in a planar nanobeam waveguide. Phys Rev B 2017;96:165306.10.1103/PhysRevB.96.165306Search in Google Scholar

[13] Carolan J, Harrold C, Sparrow C, et al. Universal linear optics. Science 2015;349:711–6.10.1126/science.aab3642Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Wang J, Paesani S, Ding Y, et al. Multidimensional quantum entanglement with large-scale integrated optics. Science 2018;360:285–91.10.1126/science.aar7053Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Luxmoore IJ, Wasley NA, Ramsay AJ, et al. Interfacing spins in an InGaAs quantum dot to a semiconductor waveguide circuit using emitted photons. Phys Rev Lett 2013;110:037402.10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.037402Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Petersen J, Volz J, Rauschenbeutel A. Chiral nanophotonic waveguide interface based on spin-orbit interaction of light. Science 2014;346:67–71.10.1126/science.1257671Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] le Feber B, Rotenberg N, Kuipers L. Nanophotonic control of circular dipole emission. Nat Commun 2015;6:6695.10.1038/ncomms7695Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Söllner I, Mahmoodian S, Hansen SL, et al. Nanophotonic control of circular dipole emission. Nat Nanotech 2015;10:775–8.10.1038/nnano.2015.159Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Coles RJ, Price DM, Dixon JE, et al. Chirality of nanophotonic waveguide with embedded quantum emitter for unidirectional spin transfer. Nat Commun 2016;7:11183.10.1038/ncomms11183Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Gonzalez-Ballestero C, Moreno E, Garcia-Vidal FJ, Gonzalez-Tudela A. Nonreciprocal few-photon routing schemes based on chiral waveguide-emitter couplings. Phys Rev A 2016;94:063817.10.1103/PhysRevA.94.063817Search in Google Scholar

[21] Lodahl P, Mahmoodian S, Stobbe S, et al. Chiral quantum optics. Nature 2017;541:473–80.10.1038/nature21037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Faez S, Türschmann P, Haakh HR, Götzinger S, Sandoghdar V. Coherent interaction of light and single molecules in a dielectric nanoguide. Phys Rev Lett 2014;113:213601.10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.213601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Türschmann P, Rotenberg N, Renger J, et al. Chip-based all-optical control of single molecules coherently coupled to a nanoguide. Nano Lett 2017;17:4941.10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b02033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Lombardi P, Ovvyan AP, Pazzagli S, et al. Photostable molecules on chip: integrated sources of nonclassical light. ACS Photon 2017;5:126.10.1021/acsphotonics.7b00521Search in Google Scholar

[25] Skoff SM, Papencordt D, Schauffert H, Bayer BC, Rauschenbeutel A. Optical-nanofiber-based interface for single molecules. Phys Rev A 2018;97:043839.10.1103/PhysRevA.97.043839Search in Google Scholar

[26] Sipahigil A, Evans RE, Sukachev DD, et al. An integrated diamond nanophotonics platform for quantum optical networks. Science 2016;354:847–50.10.1126/science.aah6875Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Schukraft M, Zheng J, Schröder T, et al. Invited article: precision nanoimplantation of nitrogen vacancy centers into diamond photonic crystal cavities and waveguides. APL Photon 2016;1:020801.10.1063/1.4948746Search in Google Scholar

[28] Bhaskar MK, Sukachev D, Sipahigil A, et al. Quantum nonlinear optics with a Germanium-vacancy color center in a nanoscale diamond waveguide. Phys Rev Lett 2017;118:223603.10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.223603Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Burek MJ, Meuwly C, Evans RE, et al. Fiber-coupled diamond quantum nanophotonic interface. Phys Rev Appl 2017;8:024026.10.1103/PhysRevApplied.8.024026Search in Google Scholar

[30] Vetsch E, Reitz D, Saguè G, Schmidt R, Dawkins ST, Rauschenbeutel A. Optical interface created by laser-cooled atoms trapped in the evanescent field surrounding an optical nanofiber. Phys Rev Lett 2010;104:203603.10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.203603Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Goban A, Choi KS, Alton DJ, et al. Demonstration of a state-insensitive, compensated nanofiber trap. Phys Rev Lett 2012;109:033603.10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.033603Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Mitsch R, Sayrin C, Albrecht B, Schneeweiss P, Rauschenbeutel A. Quantum state-controlled directional spontaneous emission of photons into a nanophotonic waveguide. Nat Commun 2014;5:5713.10.1038/ncomms6713Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Hood JD, Goban A, Asenjo-Garcia A, et al. Atom–atom interactions around the band edge of a photonic crystal waveguide. Proc Nat Acad Sci 2016;113:10507–12.10.1073/pnas.1603788113Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Roy D, Wilson CM, Firstenberg O. Colloquium: strongly interacting photons in one-dimensional continuum. Rev Mod Phys 2017;89:021001.10.1103/RevModPhys.89.021001Search in Google Scholar

[35] Ambrose WP, Moerner WE. Fluorescence spectroscopy and spectral diffusion of single impurity molecules in a crystal. Nature 1991;349:225–7.10.1038/349225a0Search in Google Scholar

[36] Tamarat P, Maali A, Lounis B, Orrit M. Ten years of single-molecule spectroscopy. J Phys Chem A 2000;104:1–16.10.1021/jp992505lSearch in Google Scholar

[37] Batalov A, Jacques V, Kaiser F, et al. Low temperature studies of the excited-state structure of negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy color centers in diamond. Phys Rev Lett 2009;102:195506.10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.195506Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Ramsay AJ, Gopal AV, Gauger EM, et al. Damping of exciton rabi rotations by acoustic phonons in optically excited InGaAs/GaAs quantum dots. Phys Rev Lett 2010;104:017402.10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.017402Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Acosta VM, Santori C, Faraon A, et al. Dynamic stabilization of the optical resonances of single nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys Rev Lett 2012;108:206401.10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.206401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Kuhlmann AV, Houel J, Ludwig A, et al. Charge noise and spin noise in a semiconductor quantum device. Nat Phys 2013;9:570–5.10.1038/nphys2688Search in Google Scholar

[41] Yamamoto T, Umeda T, Watanabe K, et al. Extending spin coherence times of diamond qubits by high-temperature annealing. Phys Rev B 2013;88:075206.10.1103/PhysRevB.88.075206Search in Google Scholar

[42] Chu Y, de Leon N, Shields B, et al. Coherent optical transitions in implanted nitrogen vacancy centers. Nano Lett 2014;14:1982–6.10.1021/nl404836pSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Thoma A, Schnauber P, Gschrey M, et al. Exploring dephasing of a solid-state quantum emitter via time- and temperature-dependent hong-ou-mandel experiments. Phys Rev Lett 2016;116:033601.10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.033601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Grandi S, Major KD, Polisseni C, Boissier S, Clark AS, Hinds EA. Quantum dynamics of a driven two-level molecule with variable dephasing. Phys Rev A 2016;94:063839.10.1103/PhysRevA.94.063839Search in Google Scholar

[45] Gmeiner B, Maser A, Utikal T, Götzinger S, Sandoghdar V. Spectroscopy and microscopy of single molecules in nanoscopic channels: spectral behavior vs. confinement depth. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2016;18:19588–94.10.1039/C6CP01698GSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Tighineanu P, Dreeßen CL, Flindt C, Lodahl P, Sørensen AS. Phonon decoherence of quantum dots in photonic structures: broadening of the zero-phonon line and the role of dimensionality. Phys Rev Lett 2018;120:257401.10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.257401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Somaschi N, Giesz V, De Santis L, et al. Near-optimal single-photon sources in the solid state. Nat Photon 2016;10:340–5.10.1038/nphoton.2016.23Search in Google Scholar

[48] Löbl MC, Söllner I, Javadi A, et al. Narrow optical linewidths and spin pumping on charge-tunable close-to-surface self-assembled quantum dots in an ultrathin diode. Phys Rev B 2017;96:165440.10.1103/PhysRevB.96.165440Search in Google Scholar

[49] Ding X, He Y, Duan Z-C, et al. On-demand single photons with high extraction efficiency and near-unity indistinguishability from a resonantly driven quantum dot in a micropillar. Phys Rev Lett 2016;116:020401.10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.020401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Rattenbacher D, Shkarin A, Renger J, Utikal T, Götzinger S, Sandoghdar V. Coherent coupling of single molecules to on-chip ring resonators. New J Phys 2019;21:062002.10.1088/1367-2630/ab28b2Search in Google Scholar

[51] Rose BC, Huang D, Zhang Z-H, et al. Observation of an environmentally insensitive solid-state spin defect in diamond. Science 2018;361:60–3.10.1126/science.aao0290Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Liao Z, Zeng X, Nha H, Zubairy MS. Photon transport in a one-dimensional nanophotonic waveguide QED system. Phys Scr 2016;91:063004.10.1088/0031-8949/91/6/063004Search in Google Scholar

[53] Vogel W, Welsch D-G. Quantum optics. 3rd ed, Berlin, Wiley-VCH, 2006.10.1002/3527608524Search in Google Scholar

[54] Meystre P, Sargent M. Elements of quantum optics. Berlin, Springer, 2007.10.1007/978-3-540-74211-1Search in Google Scholar

[55] Dung HT, Knöll L, Welsch D-G. Resonant dipole-dipole interaction in the presence of dispersing and absorbing surroundings. Phys Rev A 2002;66:063810.10.1103/PhysRevA.66.063810Search in Google Scholar

[56] Ficek Z, Tanas R. Entangled states and collective nonclassical effects in two-atom systems. Phys Rep 2002;372:369–443.10.1016/S0370-1573(02)00368-XSearch in Google Scholar

[57] Gruner T, Welsch D-G. Green-function approach to the radiation-field quantization for homogeneous and inhomogeneous Kramers-Kronig dielectrics. Phys Rev A 1996;53:1818–29.10.1103/PhysRevA.53.1818Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Buhmann SY. Dispersion forces I. Berlin, Springer, 2012.10.1007/978-3-642-32466-6Search in Google Scholar

[59] Haakh HR, Faez S, Sandoghdar V. Polaritonic normal-mode splitting and light localization in a one-dimensional nanoguide. Phys Rev A 2016;94:053840.10.1103/PhysRevA.94.053840Search in Google Scholar

[60] Asenjo-Garcia A, Hood JD, Chang DE, Kimble HJ. Atom-light interactions in quasi-one-dimensional nanostructures: a Green’s-function perspective. Phys Rev A 2017;95:033818.10.1103/PhysRevA.95.033818Search in Google Scholar

[61] Ramos T, García-Ripoll JJ. Correlated dephasing noise in single-photon scattering. New J Phys 2018;20:105007.10.1088/1367-2630/aae73bSearch in Google Scholar

[62] Gerhardt I, Wrigge G, Bushev P, et al. Exploring dephasing of a solid-state quantum emitter via time- and temperature-dependent hong-ou-mandel experiments. Phys Rev Lett 2007;98:033601.10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.033601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Zumofen G, Mojarad NM, Sandoghdar V, Agio M. Perfect reflection of light by an oscillating dipole. Phys Rev Lett 2008;101:180404.10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.180404Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Thyrrestrup H, Kiršanske˙ G, Le Jeannic H, et al. Quantum optics with near-lifetime-limited quantum-dot transitions in a nanophotonic waveguide. Nano Lett 2018;18:1801–6.10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b05016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Corzo NV, Raskp J, Chandra A, Sheremet AS, Gouraud B, Laurat J. Waveguide-coupled single collective excitation of atomic arrays. Nature 2019;566:359–62.10.1038/s41586-019-0902-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Solano P, Barberis-Blostein P, Fatemi FK, Orozco LA, Rolston SL. Super-radiance reveals infinite-range dipole interactions through a nanofiber. Nat Commun 2017;8:1857.10.1038/s41467-017-01994-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[67] Tiecke TG, Thompson JD, de Leon NP, Liu LR, Vuletić V, Lukin MD. Nanophotonic quantum phase switch with a single atom. Nature 2014;508:241–4.10.1038/nature13188Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Evans RE, Bhaskar MK, Sukachev DD, et al. Photon-mediated interactions between quantum emitters in a diamond nanocavity. Science 2018;362:662–5.10.1126/science.aau4691Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Javadi A, Söllner I, Arcari M, et al. Single-photon non-linear optics with a quantum dot in a waveguide. Nat Commun 2015;6:8655.10.1038/ncomms9655Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Hallett D, Foster AP, Hurst DL, et al. Electrical control of nonlinear quantum optics in a nano-photonic waveguide. Optica 2018;5:644–50.10.1364/OPTICA.5.000644Search in Google Scholar

[71] Le Jeannic H, et al. In preparation.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Najer D, Söllner I, Sekatski P, et al. A gated quantum dot far in the strong-coupling regime of cavity-QED at optical frequencies. 2018; arXiv:1812.08662v1.Search in Google Scholar

[73] Snijders H, Frey JA, Norman J, et al. Purification of a single-photon nonlinearity. Nat Commun 2016;7:12578.10.1038/ncomms12578Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[74] Wang D, Kelkar H, Martin-Cano D, et al. Turning a molecule into a coherent two-level quantum system. Nat Phys 2019;15:483–9.10.1038/s41567-019-0436-5Search in Google Scholar

[75] Auffèves-Garnier A, Simon C, Gèrard J-M, Poizat J-P. Giant optical nonlinearity induced by a single two-level system interacting with a cavity in the Purcell regime. Phys Rev A 2007;75:053823.10.1103/PhysRevA.75.053823Search in Google Scholar

[76] Chang D, Sørensen A, Demler E, Lukin M. A single-photon transistor using nanoscale surface plasmons. Nat Phys 2007;3:807–12.10.1038/nphys708Search in Google Scholar

[77] Roy D, Bondyopadhaya N. Statistics of scattered photons from a driven three-level emitter in a one-dimensional open space. Phys Rev A 2014;89:043806.10.1103/PhysRevA.89.043806Search in Google Scholar

[78] Schulte CHH, Hansom J, Jones AE, Matthiesen C, Le Gall C, Atatür M. Quadrature squeezed photons from a two-level system. Nature 2015;525:222–5.10.1038/nature14868Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[79] Foster AP, Hallett D, Iorsh IV, et al. Tunable photon statistics exploiting the Fano effect in a waveguide. Phys Rev Lett 2019;122:173603.10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.173603Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] Rupasov VI, Iudson VI. A rigorous theory of Dicke superradiation – Bethe wave functions in a model with discrete atoms. Eksp Zh. Teor Fiz 1984;86:819–25.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Shen J-T, Fan S. Strongly correlated two-photon transport in a one-dimensional waveguide coupled to a two-level system. Phys Rev Lett 2007;98:153003.10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.153003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[82] Shen J-T, Fan S. Strongly correlated multiparticle transport in one dimension through a quantum impurity. Phys Rev A 2007;76:062709.10.1103/PhysRevA.76.062709Search in Google Scholar

[83] Fan S, Kocabaş SE, Shen J-T. Input-output formalism for few-photon transport in one-dimensional nanophotonic waveguides coupled to a qubit. Phys Rev A 2010;82:063821.10.1103/PhysRevA.82.063821Search in Google Scholar

[84] Ramos T, García-Ripoll JJ. Multiphoton scattering tomography with coherent states. Phys Rev Lett 2017;119:153601.10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.153601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[85] Longo P, Schmitteckert P, Busch K. Few-photon transport in low-dimensional systems: interaction-induced radiation trapping. Phys Rev Lett 2010;104:023602.10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.023602Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Longo P, Schmitteckert P, Busch K. Few-photon transport in low-dimensional systems. Phys Rev A 2011;83:063828.10.1103/PhysRevA.83.063828Search in Google Scholar

[87] Törmä P, Barnes WL. Strong coupling between surface plasmon polaritons and emitters: a review. Rep Prog Phys 2014;78:013901.10.1088/0034-4885/78/1/013901Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[88] Zheng H, Gauthier DJ, Baranger HU. Waveguide QED: many-body bound-state effects in coherent and fock-state scattering from a two-level system. Phys Rev A 2010;82:063816.10.1103/PhysRevA.82.063816Search in Google Scholar

[89] Sánchez-Burillo E, Zueco D, Martín-Moreno L, García-Ripoll JJ. Dynamical signatures of bound states in waveguide QED. Phys Rev A 2017;96:023831.10.1103/PhysRevA.96.023831Search in Google Scholar

[90] Firstenberg O, Peyronel T, Liang Q-Y, Gorshkov AV, Lukin MD, Vuletić V. Attractive photons in a quantum nonlinear medium. Nature 2013;502:71–5.10.1038/nature12512Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[91] Liang Q-Y, Venkatramani AV, Cantu SH, et al. Attractive photons in a quantum nonlinear medium. Science 2018;359:783.10.1126/science.aao7293Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[92] Stiesdal N, Kumlin J, Kleinbeck K, et al. Observation of three-body correlations for photons coupled to a rydberg superatom. Phys Rev Lett 2018;121:103601.10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.103601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[93] Witthaut D, Lukin MD, Sørensen AS. Photon sorters and QND detectors using single photon emitters. EPL (Europhys Lett) 2012;97:50007.10.1209/0295-5075/97/50007Search in Google Scholar

[94] Ralph TC, Söllner I, Mahmoodian S, White A, Lodahl P. Tunable photon statistics exploiting the fano effect in a waveguide. Phys Rev Lett 2015;114:173603.10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.173603Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[95] Roy D. Few-photon optical diode. Phys Rev B 2010;81:155117.10.1103/PhysRevB.81.155117Search in Google Scholar

[96] Wu FY, Ezekiel S, Ducloy M, Mollow BR. Observation of amplification in a strongly driven two-level atomic system at optical frequencies. Phys Rev Lett 1977;38:1077–80.10.1103/PhysRevLett.38.1077Search in Google Scholar

[97] Maser A, Gmeiner B, Utikal T, Götzinger S, Sandoghdar V. Few-photon coherent nonlinear optics with a single molecule. Nat Photon 2016;10:450–3.10.1038/nphoton.2016.63Search in Google Scholar

[98] Lezama A, Zhu Y, Kanskar M, Mossberg TW. Radiative emission of driven two-level atoms into the modes of an enclosing optical cavity: the transition from fluorescence to lasing. Phys Rev A 1990;41:1576–81.10.1103/PhysRevA.41.1576Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[99] Papademetriou S, Chakmakjian S, Stroud CR. Optical subharmonic Rabi resonances. J Opt Soc Am B 1992;9:1182–8.10.1364/JOSAB.9.001182Search in Google Scholar

[100] Jelezko F, Lounis B, Orrit M. Pump–probe spectroscopy and photophysical properties of single di-benzanthanthrene molecules in a naphthalene crystal. J Chem Phys 1997;107: 1692–702.10.1063/1.474525Search in Google Scholar

[101] Xu X, Sun B, Berman PR, et al. Coherent optical spectroscopy of a strongly driven quantum dot. Science 2007;317: 929–32.10.1126/science.1142979Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[102] Xu X, Sun B, Kim ED, et al. Single charged quantum dot in a strong optical field: absorption, gain, and the ac-stark effect. Phys Rev Lett 2008;101:227401.10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.227401Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[103] Gheeraert N, Zhang XHH, Sèpulcre T, et al. Particle production in ultrastrong-coupling waveguide QED. Phys Rev A 2018;98:043816.10.1103/PhysRevA.98.043816Search in Google Scholar

[104] Fleischhauer M, Imamoglu A, Marangos JP. Electromagnetically induced transparency: optics in coherent media. Rev Mod Phys 2005;77:633–73.10.1103/RevModPhys.77.633Search in Google Scholar

[105] Xu S, Fan S. Generate tensor network state by sequential single-photon scattering in waveguide QED systems. APL Photon 2018;3:116102.10.1063/1.5044248Search in Google Scholar

[106] Roy D. Two-photon scattering by a driven three-level emitter in a one-dimensional waveguide and electromagnetically induced transparency. Phys Rev Lett 2011;106:053601.10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.053601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[107] Chanelièr T, Matsukevich DN, Jenkins SD, Lan S-Y, Kennedy TAB, Kuzmich A. Storage and retrieval of single photons transmitted between remote quantum memories. Nature 2005;483:833–6.10.1038/nature04315Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[108] Sayrin C, Clausen C, Albrecht B, Schneeweiss P, Rauschenbeutel A. Storage of fiber-guided light in a nanofiber-trapped ensemble of cold atoms. Optica 2015;2:353–6.10.1364/OPTICA.2.000353Search in Google Scholar

[109] Le Kien F, Rauschenbeutel A. Electromagnetically induced transparency for guided light in an atomic array outside an optical nanofiber. Phys Rev A 2015;91:053847.10.1103/PhysRevA.91.053847Search in Google Scholar

[110] Song G-Z, Munro E, Nie W, Deng F-G, Yang G-J, Kwek L-C. Photon scattering by an atomic ensemble coupled to a one-dimensional nanophotonic waveguide. Phys Rev A 2017;96:043872.10.1103/PhysRevA.96.043872Search in Google Scholar

[111] Witthaut D, Sørensen AS. Photon scattering by a three-level emitter in a one-dimensional waveguide. New J Phys 2010;12:043052.10.1088/1367-2630/12/4/043052Search in Google Scholar

[112] Bermel P, Rodriguez A, Johnson SG, Joannopoulos JD, Soljačić M. Single-photon all-optical switching using waveguide-cavity quantum electrodynamics. Phys Rev A 2006;74:043818.10.1103/PhysRevA.74.043818Search in Google Scholar

[113] Hwang J, Pototschnig M, Lettow R, et al. A single-molecule optical transistor. Nature 2009;460:76–80.10.1038/nature08134Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[114] Kewes G, Schoengen M, Neitzke O, et al. A realistic fabrication and design concept for quantum gates based on single emitters integrated in plasmonic-dielectric waveguide structures. Sci Rep 2016;6:28877.10.1038/srep28877Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[115] Kolchin P, Oulton RF, Zhang X. Nonlinear quantum optics in a waveguide: distinct single photons strongly interacting at the single atom level. Phys Rev Lett 2011;106:113601.10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.113601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[116] Li TY, Huang JF, Law CK. Scattering of two distinguishable photons by a Ξ-type three-level atom in a one-dimensional waveguide. Phys Rev A 2015;91:043834.10.1103/PhysRevA.91.043834Search in Google Scholar

[117] Raussendorf R, Briegel HJ. A one-way quantum computer. Phys Rev Lett 2001;86:5188–91.10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.5188Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[118] Zheng H, Gauthier DJ, Baranger HU. Strongly correlated photons generated by coupling a three- or four-level system to a waveguide. Phys Rev A 2012;85:043832.10.1103/PhysRevA.85.043832Search in Google Scholar

[119] Machielse B, Bogdanovic S, Meesala S, et al. Quantum interference of electromechanically stabilized emitters in nanophotonic devices. Phys Rev X 2019;9:031022.10.1103/PhysRevX.9.031022Search in Google Scholar

[120] Türschmann P, Rotenberg N, Renger J, et al. On-chip linear and nonlinear control of single molecules coupled to a nanoguide. 2017; arXiv:1702.05923.10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b02033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[121] Türschmann P. Coherent coupling of organic dye molecules to optical nanoguides. Boca Raton, FL: FAU University Press, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[122] Bajcsy M, Hofferberth S, Balic V, et al. Efficient all-optical switching using slow light within a hollow fiber. Phys Rev Lett 2009;102:203902.10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.203902Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[123] Lodahl P. Scaling up solid-state quantum photonics. Science 2018;362:646.10.1126/science.aav3076Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[124] Dzsotjan D, Sørensen AS, Fleischhauer M. Quantum emitters coupled to surface plasmons of a nanowire: a Green’s function approach. Phys Rev B 2010;82:075427.10.1103/PhysRevB.82.075427Search in Google Scholar

[125] Gonzalez-Tudela A, Martin-Cano D, Moreno E, Martin-Moreno L, Tejedor C, Garcia-Vidal FJ. Entanglement of two qubits mediated by one-dimensional plasmonic waveguides. Phys Rev Lett 2011;106:020501.10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.020501Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[126] Martín-Cano D, González-Tudela A, Martín-Moreno L, García-Vidal FJ, Tejedor C, Moreno E. Dissipation-driven generation of two-qubit entanglement mediated by plasmonic waveguides. Phys Rev B 2011;84:235306.10.1103/PhysRevB.84.235306Search in Google Scholar

[127] Zhang XHH, Baranger HU. Heralded bell state of dissipative qubits using classical light in a waveguide. Phys Rev Lett 2019;122:140502.10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.140502Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[128] Das S, Elfving VE, Faez S, Sørensen AS. Interfacing superconducting qubits and single optical photons using molecules in waveguides. Phys Rev Lett 2017;118:140501.10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.140501Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[129] Elfving VE, Das S, Sørensen AS. Enhancing quantum transduction via long-range waveguide mediated interactions between quantum emitters. 2018; arXiv:1810.01381.10.1103/PhysRevA.100.053843Search in Google Scholar

[130] Zhang XHH, Baranger HU. Quantum interference and complex photon statistics in waveguide QED. Phys Rev A 2018;97:023813.10.1103/PhysRevA.97.023813Search in Google Scholar

[131] Fang Y-LL, Baranger HU. Waveguide QED: power spectra and correlations of two photons scattered off multiple distant qubits and a mirror. Phys Rev A 2015;91:053845.10.1103/PhysRevA.91.053845Search in Google Scholar

[132] Mirza IM, Schotland JC. Multiqubit entanglement in bidirectional-chiral-waveguide QED. Phys Rev A 2016;94:012302.10.1103/PhysRevA.94.012302Search in Google Scholar

[133] Mirza IM, Hoskins JG, Schotland JC. Chirality, band structure, and localization in waveguide quantum electrodynamics. Phys Rev A 2017;96:053804.10.1103/PhysRevA.96.053804Search in Google Scholar

[134] Mahmoodian S, Čepulkovskis M, Das S, Lodahl P, Hammerer K, Sørensen AS. Strongly correlated photon transport in waveguide quantum electrodynamics with weakly coupled emitters. Phys Rev Lett 2018;121:143601.10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.143601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[135] Mukhopadhyay D, Agarwal GS. Multiple Fano interferences due to waveguide-mediated phase-coupling between atoms. 2019; arXiv:1902.10855.10.1103/PhysRevA.100.013812Search in Google Scholar

[136] Albrecht A, Henriet L, Asenjo-Garcia A, Dieterle PB, Painter O, Chang DE. Subradiant states of quantum bits coupled to a one-dimensional waveguide. New J Phys 2019;21:025003.10.1088/1367-2630/ab0134Search in Google Scholar

[137] Cheng M-T, Xu J, Agarwal GS. Waveguide transport mediated by strong coupling with atoms. Phys Rev A 2017;95:053807.10.1103/PhysRevA.95.053807Search in Google Scholar

[138] Pivovarov VA, Sheremet AS, Gerasimov LV, et al. Light scattering from an atomic array trapped near a one-dimensional nanoscale waveguide: a microscopic approach. Phys Rev A 2018;97:023827.10.1103/PhysRevA.97.023827Search in Google Scholar

[139] Das S, Elfving VE, Reiter F, Sørensen AS. Photon scattering from a system of multilevel quantum emitters. II. Application to emitters coupled to a one-dimensional waveguide. Phys Rev A 2018;97:043838.10.1103/PhysRevA.97.043838Search in Google Scholar

[140] González-Tudela A, Paulisch V, Kimble HJ, Cirac JI. Coherent interaction of light and single molecules in a dielectric nanoguide. Phys Rev Lett 2017;118:213601.10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.213601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[141] Mirza IM, Schotland JC. Influence of disorder on electromagnetically induced transparency in chiral waveguide quantum electrodynamics. J Opt Soc Am B 2018;35:1149–58.10.1364/JOSAB.35.001149Search in Google Scholar

[142] Schmidt H, Imamoglu A. Giant Kerr nonlinearities obtained by electromagnetically induced transparency. Opt Lett 1996;21:1936–8.10.1364/OL.21.001936Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[143] Hafezi M, Chang DE, Gritsev V, Demler E, Lukin MD. Quantum transport of strongly interacting photons in a one-dimensional nonlinear waveguide. Phys Rev A 2012;85:013822.10.1103/PhysRevA.85.013822Search in Google Scholar

[144] Chang DE, Gritsev V, Morigi G, Vuletić V, Lukin MD, Demler EA. Crystallization of strongly interacting photons in a nonlinear optical fibre. Nat Phys 2008;4:884–9.10.1038/nphys1074Search in Google Scholar

[145] Shahmoon E, Grišins P, Stimming HP, Mazets I, Kurizki G. Highly nonlocal optical nonlinearities in atoms trapped near a waveguide. Optica 2016;3:725–33.10.1364/OPTICA.3.000725Search in Google Scholar

[146] Douglas JS, Caneva T, Chang DE. Photon molecules in atomic gases trapped near photonic crystal waveguides. Phys Rev X 2016;6:031017.10.1103/PhysRevX.6.031017Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 Nir Rotenberg et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Optically accessible memristive devices

- Role of nanophotonics in the birth of seismic megastructures

- Perovskite nanocrystals for energy conversion and storage

- Coherent nonlinear optics of quantum emitters in nanophotonic waveguides