Abstract

The precise measurement of gain lifetime at a specific wavelength holds significant importance for understanding the properties of photonic devices and further improving their performances. Here, we show that the evolution of gains can be well characterized by measuring linewidth changes of an optical mode in a microresonator; this method cannot be achieved using time-resolved photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy. We use an erbium-doped high-Q whispering-gallery microresonator to show the feasibility of this method. With the increase of time after the pump laser is turned off, the transmission spectrum of a probe signal exhibits transitions from a Lorentz peak to a dip; this indicates a decay of optical gains, and the corresponding lifetime is estimated to be 5.1 ms. Moreover, taper fiber coupling is used to increase the pump and collection efficiency. This method can be extended to other materials and nanostructures.

1 Introduction

Optical gain can dramatically modify the response of a system and compensate for the loss of light during communications and information processing. Such gain processes play an important role in various applications [1], including lasers and masers, optical amplifiers, and sensitive detections. The optical gain typically results from the stimulated emission process, which is generated from the recombination of electrons and holes in semiconductors or the coherent amplification through population inversion between different energy levels in gain medium. The lifetime of optical gain, a fundamental parameter and of significant importance for understanding light-matter interaction, determines various properties of a system, for example, the maximum switch speed of the input signal in an active optical switch [2]. The stimulated radiation process corresponds to specific energy level transitions. Therefore, the emission light is considered to have the same properties as those of the input light. By contrast, the luminescence, which results from the spontaneous radiation of excited states and multi-channel transitions, has a wide broadening in spectrum and contains lights in different wavelengths [3]. The lifetime of luminescence can be accurately measured through the changes of its intensity after the pump source is turned off; also, optical gain lifetime needs a simple, effective, and fast method to be characterized precisely.

The whispering-gallery mode (WGM) microresonator [4], [5], [6], which has an ultra-high-quality factor higher than 108 and mode volumes at the cubic micrometer scale, has been widely used in many applications [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Moreover, the WGM microresonator serves as a fruitful platform to study various applications of optical gains. Ultra-low-threshold micro-lasers have been implemented using a silica microsphere, microdisk, and microtoroid [15], [16]. Furthermore, sensitive metrology and detection have been realized in active microresonators [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. WGM microresonators have received strong interest for the realization of cavity quantum electrodynamical systems [7], [8] and the classical analog of quantum systems, such as parity-time optics [22], [23], [24], [25], [26] and electromagnetically induced transparency [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. To further improve the performance of WGM microresonators, one can decrease their sizes to obtain smaller mode volumes and stronger light-matter interactions; however, this approach can increase bending losses and lower Q values. Another method is to dope rare-earth ions (e.g. Er3+, Yb3+, or Nd3+) [1], [3], [15] or introduce intrinsic Raman gain from the material [18], [19], [32]. For rare-earth ions (e.g. erbium ions), transitions between internal energy levels are stable because these processes which take place in 4f shells are shielded from the interaction with other atoms by the external 5s and 5p electrons. This stability makes rare-earth ions a universal candidate for practical applications, e.g. displays or lighting, performance improvements of magnetic materials, and optical communications. Recently, rare-earth-doped WGM microresonators have been successfully applied in signal amplifiers [33], ultra-long storage of photons [34], and on-demand coupling control [35], [36].

To date, there is no related study that has been conducted to identify optical gain lifetime in microresonators. Here, we present a direct and precise measurement of this lifetime at a specific wavelength through the linewidth changes of an optical mode. An Er3+-doped material is taken as an example to demonstrate the feasibility of this method. To enhance the light-matter interaction, we dope erbium ions into WGM microresonators. In our study, a pump laser with a central wavelength of 1430 nm and an input power of 275 μW was coupled into the microtoroid through a tapered fiber to excite erbium ions into intermediate states. Then, this excitation was turned off by optothermal squeezing within 2 μs. Next, another laser in 1550 nm band with a high scanning speed of 4.2 THz/s served as the probe signal. To eliminate the influence of temperature, the thermal relaxation time was also precisely characterized to be 0.33 ms via optothermal spectroscopy. We used six different probe signals with the wavelength scanned over the range from 1528 nm to 1556 nm and wavelength differences of 5.6 nm, which is approximately one free spectral range (FSR). Gain lifetime was measured to be approximately 5.1 ms. Through continually tuning the microresonator, lifetime of optical gains at different resonant wavelengths could also be well measured. Our results precisely show the evolution of optical gain at specific wavelengths, and the lifetime can be characterized simultaneously by measuring the linewidth changes of a probe mode; by contrast, the standard time-resolved photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy technique, which is based on spontaneous emission of excited states, can just measure the lifetime of fluorescence through its changes of intensity with time. Therefore, the experimental results demonstrated here cannot be achieved by the previous PL technique. Moreover, the use of tapered fiber coupling allows for higher pump and collection efficiencies, thereby greatly decreasing the demand for detectors and measurement techniques.

2 The methods and the evolution of transmission spectra

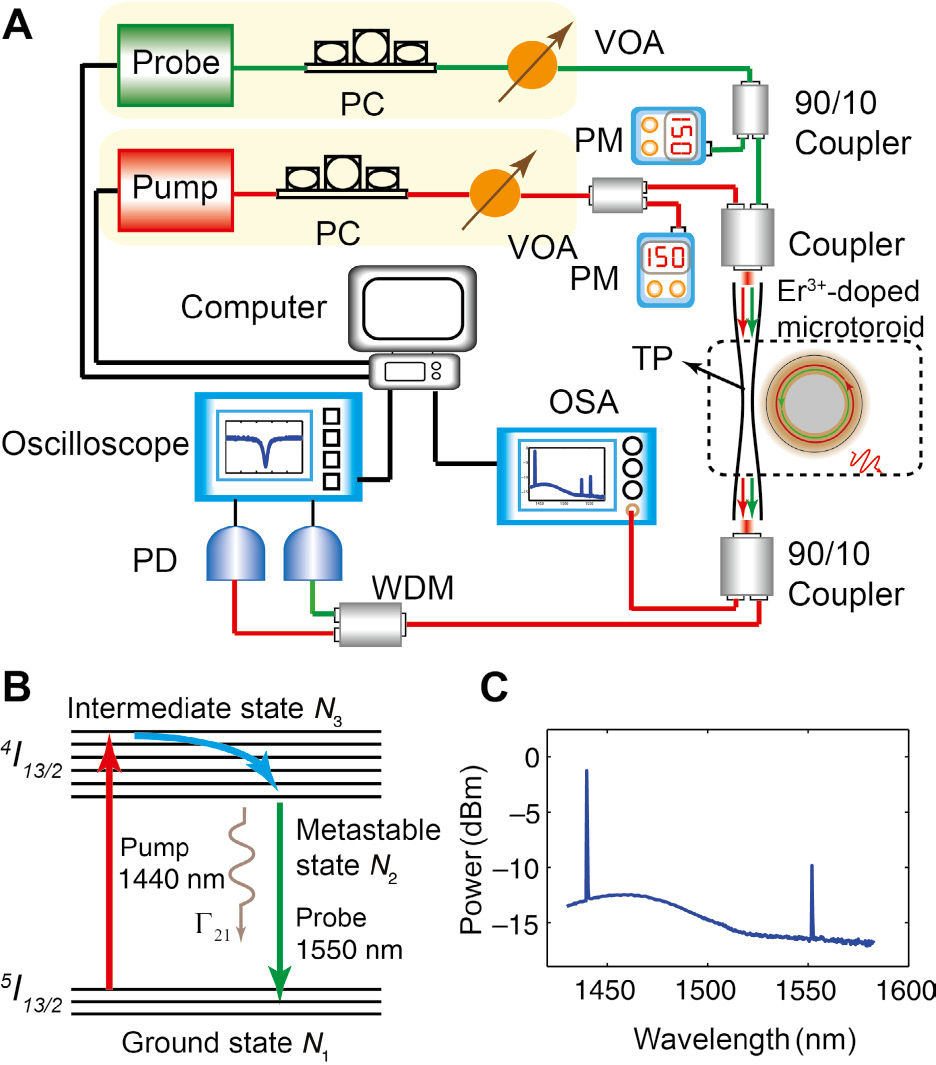

The experimental configuration is depicted in Figure 1, which shows a silica microtoroidal WGM resonator directly coupled to a tapered fiber. The WGM resonator is an Er3+-doped microtoroid, which is fabricated using the sol-gel technique [22], [37]. First, silica layers with a thickness of 2 μm and an ion concentration of 7.4×1024 ions/cm3 are fabricated on the surface of a silicon wafer. Subsequently, photolithography, pattern transfer, dry etching, and reflow are applied to form this surface-tension-induced microtoroid. Figure 1C demonstrates the emission spectum of Er3+-doped microtoroid when it is pumped around 1430 nm band. The WGM resonator has intrinsic Q values of 4.2×106 in the 1430 nm pump mode and 5.3×106 in the 1550 nm probe mode. The tapered fiber [38], [39], with a waist diameter of approximately 2 μm, is fabricated through the heat and pull process using a single-mode optical fiber operating in the 1550 nm window. The pump laser and probe signal are provided by two tunable laser diodes with linewidths less than 200 kHz. The central wavelengths and scanning speeds of these laser diodes can be precisely controlled by a computer. The light emitted from laser diodes is coupled into the microtoroid through a coupler and tapered fiber. This tapered fiber has a coupling efficiency exceeding 99%, i.e. the normalized transmission can nearly reach zero and more than 99% of input light can couple into the microtoroid when an optical mode is excited resonantly. Moreover, a three-axis stage with resolution 0.1 μm can continuously tune the coupling strength between this taper fiber and the microtoroid. The light coupled out is divided into two parts. One component (constituting 10%) part is connected with an optical spectrum analyzer (OSA), and the other component (constituting the remaining 90% part) is further divided into 1550 nm and 1430 nm bands after passing through a wavelength division multiplexer (WDM). Finally, the light from these two bands are collected by two photon detectors (PDs) and monitored by an oscilloscope. During the entire process, two variable optical attenuators (VOAs) and polarization controllers (PCs) were used to control the input power and polarization, respectively.

Experimental setup, energy levels and emission spectra of erbium ions.

(A) Experimental configuration for measuring optical gain lifetime. VOA, variable optical attenuator; WDM, wavelength division multiplexer; PD, photodetector; OSA, optical spectrum analyzer; PM, power meter; TP, tapered fiber; PC, polarization controller. (B) The energy levels of erbium ions. Γ21 stands for spontaneous decay rate of erbium ions from metastable states into ground states. (C) Emission spectra of Er3+-doped WGM microcavities pumped in the 1430 nm band.

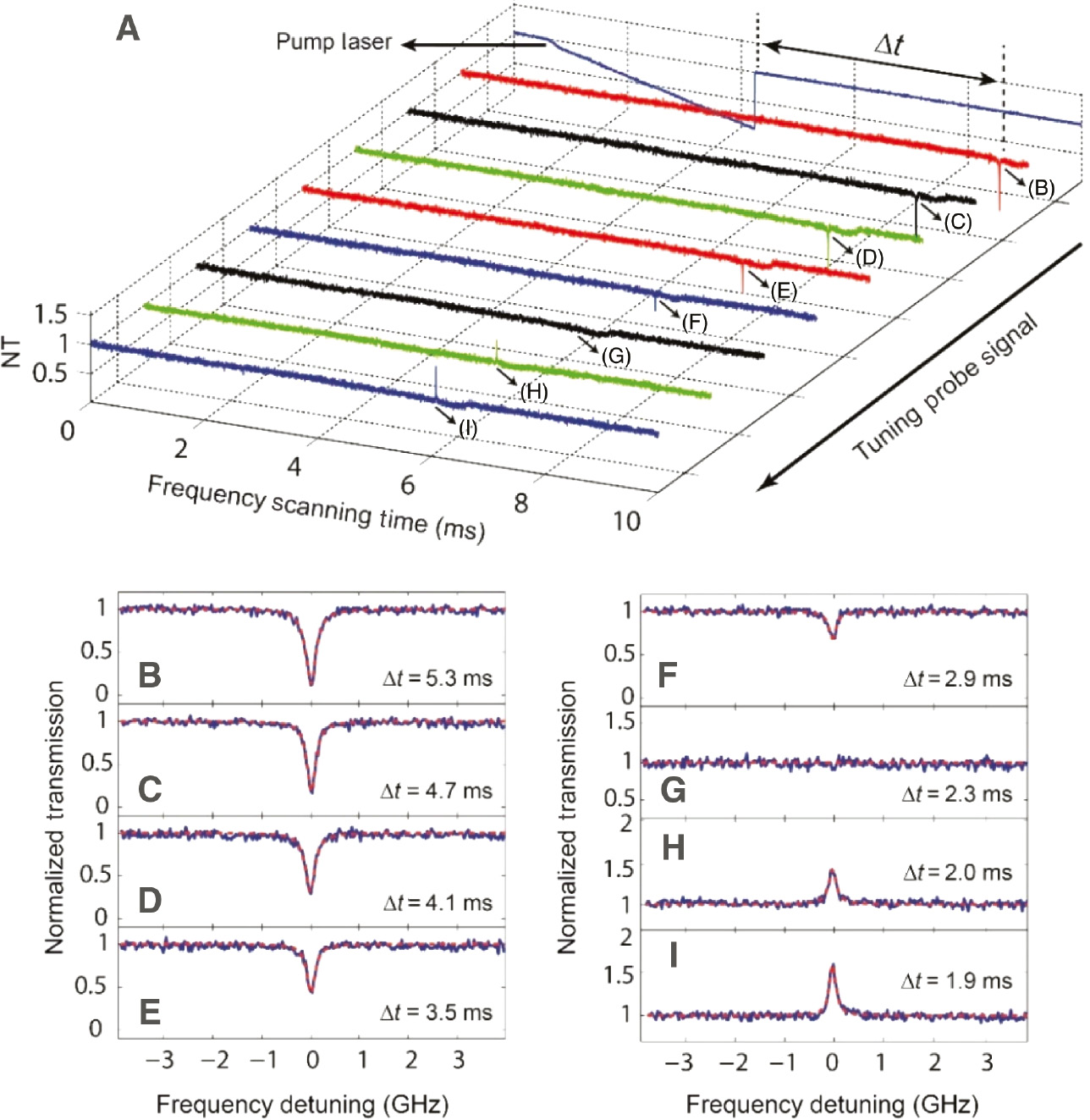

Figure 2 demonstrates the process to measure the lifetime of optical gain. Here, the pump laser in 1430 nm band is linearly modulated at a lower frequency scanning speed 1.2 THz/s, and the frequency scanning speed of the probe signal in 1550 nm band is 4.2 THz/s. The transmission spectrum of this pump laser exhibits triangular broadening due to the optothermal effect, and the probe signal has a standard Lorentz lineshape. Even after being turned off, the pump laser can still provide optical gain for this probe signal after the delay time Δt. Here, we turn off the pump laser within 2 μs through thermal mode squeezing so that the pump laser is off resonance with cavity mode and little light can couple into microtoroid. This mode squeezing is induced by the optothermal effect, where the central wavelength of this pump mode has an opposite shift direction with respect to the input light [30]. As shown in Figure 2A, we continuously tune this probe signal by decreasing. Δt while the pump laser is kept unchanged. The transmission spectra of this probe signal evolve from a Lorentz dip to a Lorentz peak. Note that the measurement in this figure is in the over coupling regime, i.e. the coupling strength between the tapered fiber and microtoroid is greater than the intrinsic dissipation rate of the cavity mode. Figure 2B–I exhibits the changes of these transmission spectra in detail. This process can be divided into three regions: the Lorentz dip region, the transparency region, and the Lorentz peak region. Figure 2B–F corresponds to the Lorentz dip region. In this region, the linewidth of this probe signal becomes increasingly small with the decrease of Δt, and the minimum transmission becomes increasingly high. At the time Δt=2.3 ms, the transmission becomes totally transparent, indicating that the existence of this microtoroid does not cause any loss of the light; that is to say, optical gain provided by erbium ions can completely compensate for the intrinsic loss. The Lorentz peak region is shown in Figure 2H and I, in which this probe signal is amplified, and the transmission is above the normalized line. In this Lorentz peak region, the linewidth of this resonance would continue to decrease, and the peak value becomes increasingly high with the decrease of Δt. The evolution of this probe signal can be described by the differential equation based on the coupled-mode theory [40], [41]:

Evolution of the transmission spectra when tuning probe signal.

(A) Evolution of the transmission spectra when measuring the optical gain lifetime. When we decrease the time Δt after the pump laser is turned off, this probe signal become increasingly amplified together with more gains. (B)–(I) Show the details and the fitting curves (red dashed lines) in (A). Note that the horizontal coordinate of (A), i.e. frequency scanning time, has been transformed into frequency detuning in (B)–(I) according to the scanning speed of this probe signal. The pump power here is 275 μW, and the probe signal power is 150 nm. NT denotes normalized transmission.

where as describes the amplitude of this probe signal inside the microtoroid,

Under the steady-state situation, the normalized transmission can be expressed by the following equation using the standard input-output relationship:

Here,

Note that when the pump laser is turned off, the temperature of the microtoroid follows an exponential decay. This decay may result in mode squeezing and cause errors in the measurement of optical gains. Therefore, the delay time Δt should be greater than the thermal relaxation time 1/γT to avoid this optothermal effect. Here, the thermal relaxation time 1/γT of the microtoroid is characterized to be 0.33 ms using the optothermal spectroscopy method (more details are introduced in Supplementary Note 1). During the gain lifetime measurement, the temperature of the microtoroid is always the same as room temperature. Moreover,

3 Measurement of gain lifetime

Figure 1B shows the energy levels of erbium ions in a standard Λ-type level system. For convenience, the 5I13/2 state is rewritten as the ground state, and the 4I13/2 state consists of both the intermediate state and metastable state. The pump laser in the 1430 nm band excites erbium ions from the ground state into the intermediate state; subsequently, this excitation decays into the metastable state quickly without the emission of photons. In addition, erbium ions in metastable states decay into ground states at a relatively low rate Γ21; the lifetime 1/Γ21 can be as long as several milliseconds [1]. When a rapidly modulated probe signal with scanning speed 4.2 THz/s in the 1550 nm band is coupled into this system, erbium ions in metastable states would jump into ground states and provide optical gain for this probe signal. The gain gs is determined by the population inversions between these two energy levels [1]:

Here,

From Eq. (3) and above analyses, the effective energy decay rate

In the above expression,

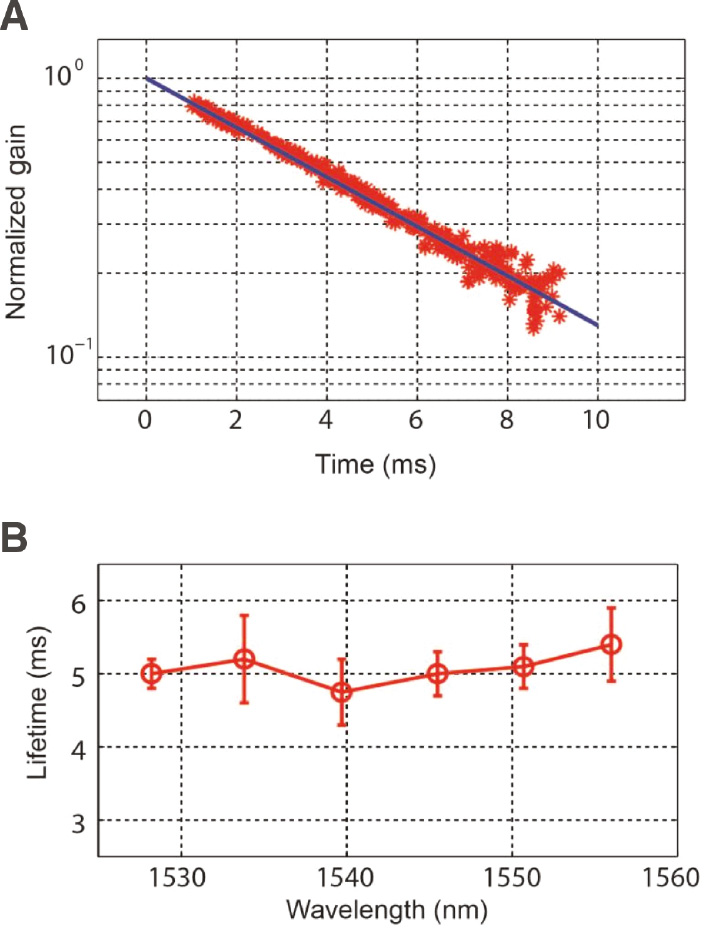

The experimental results are shown in Figure 3. As shown in Figure 3A, gain lifetime at the resonant wavelength 1551 nm is 5.1 ms when the input power of this probe signal is 150 nW; furthermore, if the input power is increased to 230 nW and 310 nW, nearly the same value is obtained (see Supplementary Figure S5). Note that gs can be regarded as a constant only when the input power is small enough; otherwise, the Fano-like resonance shape may appear [43]. Figure 3B demonstrates experimental results at various resonant wavelengths, which are all around 5.1 ms. From Eq. (4), the lifetime of optical gain is determined only by the spontaneous decay rate from the 4I13/2 state to the 5I13/2 state. Meanwhile, the strength of optical gains is also determined by the absorption and emission cross sections

The evolution of gain and gain lifetime at different wavelengths.

(A) Normalized optical gains

The population of erbium ions follows a Boltzmann’s distribution when the system is not pumped, i.e.

where Γ32 is the transition rate of erbium ions from the intermediate state into the metastable state; this rate is generally larger than Γ21 by three orders of magnitude. ϕp is the photon flux, i.e. the number of photons per unit area within a unit time.

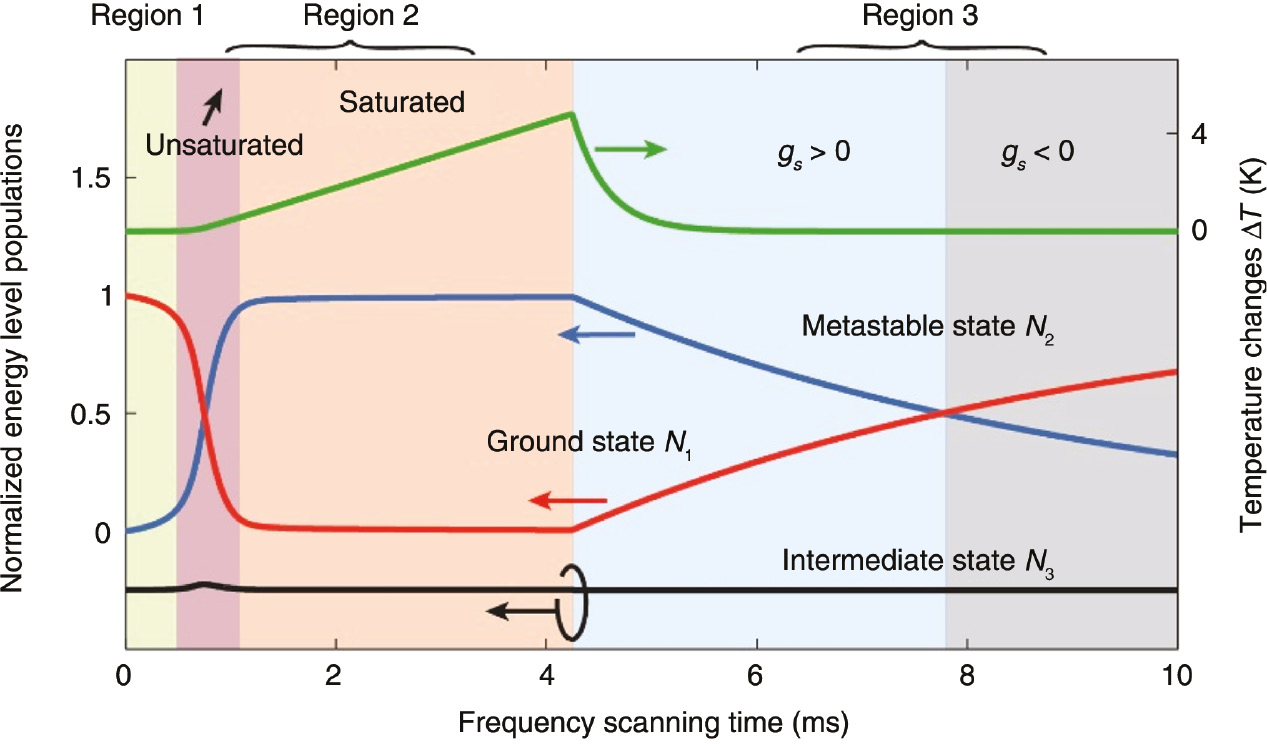

Figure 4 depicts the behavior of microtoroid and erbium ions using numerical calculations. According to the temperature changes, this figure can be divided into three regions. In Region 1, when little pump laser is coupled into the microtoroid, most erbium ions are in their ground states. Moreover, the temperature remains nearly the same as room temperature. In Region 2, more pump light is coupled into the microtoroid with the decrease of detuning Δωp, and erbium ions start to make transitions from the ground state into the intermediate state. Furthermore, this region can be divided into saturated and unsaturated areas. In the unsaturated area, population inversions increase sharply. In the saturated area, where the pump is strong enough to satisfy the condition σpϕp≫Γ21, nearly all the erbium ions are in the metastable state, i.e. N2≈Ntotal. In Region 3, when the pump laser is turned off, both the temperature and the number of erbium ions in metastable states exhibit an exponential decay. These two rates obey the relation γT/Γ21≈15.45. For

Populations of erbium ions in ground states N1 (red line), metastable states N2 (blue line), and intermediate states N3 (black line), and temperature changes Δt (green line).

Note that the intermediate state population is moved down by 0.25. The parameters are Vmode=367 μm3,

As erbium ions are doped into the microresonator, the decay rate Γ21 contains the Purcell effect enhanced spontaneous decay rate FpΓr, the erbium ion energy exchange induced decay rate

4 Conclusion

In this article, we present the direct measurement of gain lifetime at a specific wavelength through the changes of one optical mode; such a measurement cannot be achieved by the previous PL method. An erbium-doped WGM microresonator was used to show the efficiency of this method. We used six probe signals with the wavelength differences of 5.6 nm (one FSR). All the optical gain lifetime values were found to be approximately 5.1 ms, which is much longer than the thermal relaxation time of 0.33 ms. The method is universal and can be extended to other materials and structures.

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 61622103

Award Identifier / Grant number: 61727801

Award Identifier / Grant number: 11774197

Award Identifier / Grant number: 61471050

Award Identifier / Grant number: 61671083

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2016YFA0301304

Funding statement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (MOST) (grant no. 2016YFA0301304); The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 61622103, 61727801, 11774197, 61471050 and 61671083); The Fok Ying-Tong Education Foundation for Young Teachers in the Higher Education Institutions of China (grant no. 151063); The Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Information Photonics and Optical Communications (Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications), P. R. China; And the Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Future Chip (ICFC). F. Lei is supported by Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) Graduate University.

References

[1] Becker PC, Olsson NA, Simpson JR. Erbium-doped fiber amplifiers: fundamentals and technology. San Diego, USA, Academic Press, 1999.10.1016/B978-012084590-3/50007-7Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Ilchenko VS, Matsko AB. Optical resonators with whispering-gallery modes-part II: applications. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron 2006;12:5–32.10.1109/JSTQE.2005.862943Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Reynolds T, Riesen N, Meldrum A, et al. Fluorescent and lasing whispering gallery mode microresonators for sensing applications. Laser Photonics Rev 2017;11:1600265.10.1002/lpor.201600265Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Vahala KJ. Optical microcavities. Nature 2003;424:839–46.10.1038/nature01939Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Chiasera A, Dumeige Y, Féron P, et al. Spherical whispering- gallery-mode microresonators. Laser Photonics Rev 2010;4:457–82.10.1002/lpor.200910016Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Armani DK, Kippenberg TJ, Spillane SM, Vahala KJ. Ultra-high-Q toroid microcavity on a chip. Nature 2003;421:925–8.10.1038/nature01371Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Dayan B, Parkins AS, Aoki T, Ostby EP, Vahala KJ, Kimble HJ. A photon turnstile dynamically regulated by one atom. Science 2008;319:1062–5.10.1126/science.1152261Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Scheucher M, Hilico A, Will E, Volz J, Rauschenbeutel A. Quantum optical circulator controlled by a single chirally coupled atom. Science 2016;354:1577–80.10.1126/science.aaj2118Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Zhi Y, Yu X-C, Gong Q, Yang L, Xiao Y-F. Single nanoparticle detection using optical microcavities. Adv Mater 2017;29:1604920.10.1002/adma.201604920Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Monifi F, Zhang J, Özdemir ŞK, et al. Optomechanically induced stochastic resonance and chaos transfer between optical fields. Nat Photonics 2016;10:399–405.10.1038/nphoton.2016.73Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Zhu J, Özdemir ŞK, Yang L. Infrared light detection using a whispering-gallery-mode optical microcavity. Appl Phys Lett 2014;104:171114.10.1063/1.4874652Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Kippenberg TJ, Holzwarth R, Diddams SA. Microresonator-based optical frequency combs. Science 2011;332:555–9.10.1126/science.1193968Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Bo F, Wang J, Cui J, et al. Lithium-Niobate-Silica hybrid whispering-gallery-mode resonators. Adv Mater 2015;27:8075–81.10.1002/adma.201504722Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Jiang X, Shao L, Zhang S-X, et al. Chaos-assisted broadband momentum transformation in optical microresonators. Science 2017;358:344.10.1126/science.aao0763Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Yang L, Armani DK, Vahala KJ. Fiber-coupled erbium microlasers on a chip. Appl Phys Lett 2003;83:825.10.1063/1.1598623Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Kippenberg TJ, Kalkman J, Polman A, Vahala KJ. Demonstration of an erbium-doped microdisk laser on a silicon chip. Phys Rev A 2006;74:051802(R).10.1103/PhysRevA.74.051802Suche in Google Scholar

[17] He L, Özdemir ŞK, Zhu J, Kim W, Yang L. Detecting single viruses and nanoparticles using whispering gallery microlasers. Nat Nanotechnol 2011;6:428.10.1038/nnano.2011.99Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Özdemir ŞK, Zhu J, Yang X, et al. Highly sensitive detection of nanoparticles with a self-referenced and self-heterodyned whispering-gallery raman microlaser. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:E3836–44.10.1073/pnas.1408283111Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Li B-B, Clements WR, Yu X-C, Shi K, Gong Q, Xiao Y-F. Single nanoparticle detection using split-mode microcavity raman Lasers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:14657–62.10.1073/pnas.1408453111Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Liu Z-P, Zhang J, Özdemir ŞK, et al. Metrology with PT-symmetric cavities: enhanced sensitivity near the PT-phase transition. Phys Rev Lett 2016;117:110802.10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.110802Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Asano M, Bliokh KY, Bliokh YP, et al. Anomalous time delays and quantum weak measurements in optical micro-resonators. Nat Commun 2016;7:13488.10.1038/ncomms13488Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Peng B, Özdemir ŞK, Lei F, et al. Parity-time-symmetric whispering-gallery microcavities. Nat Phys 2014;10:394–8.10.1038/nphys2927Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Chang L, Jiang X, Hua S, et al. Parity-time symmetry and variable optical isolation in active-passive-coupled microresonators. Nat Photonics 2014;5:524–9.10.1038/nphoton.2014.133Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Peng B, Özdemir ŞK, Rotter S, et al. Loss-induced suppression and revival of lasing. Science 2014;346:328–32.10.1126/science.1258004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Jing H, Özdemir ŞK, Lü X-Y, Zhang J, Yang L, Nori F. PT-symmetric phonon laser. Phys Rev Lett 2014;113:053604.10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.053604Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Hodaei H, Miri M-A, Heinrich M, Christodoulides DN, Khajavikhan M. Parity-time-symmetric microring lasers. Science 2014;346:975–8.10.1126/science.1258480Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Weis S, Riviere R, Deleglise S, et al. Optomechanically induced transparency. Science 2010;330:1520–3.10.1126/science.1195596Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Shen Z, Zhang Y-L, Chen Y, et al. Experimental realization of optomechanically induced non-reciprocity. Nat Photonics 2016;10:657–61.10.1038/nphoton.2016.161Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Peng B, Özdemir ŞK, Chen W, Nori F, Yang L. What is and what is not electromagnetically-induced-transparency in whispering-gallery-microcavities. Nat Commun 2014;5:5082.10.1038/ncomms6082Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Dong C, Fiore V, Kuzyk MC, Wang H. Optomechanical dark mode. Science 2012;338:1609–13.10.1126/science.1228370Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Fan L, Fong KY, Poot M, Tang HX. Cascaded optical transparency in multimode-cavity optomechanical systems. Nat Commun 2015;6:5850.10.1038/ncomms6850Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Yang X, Özdemir ŞK, Peng B, et al. Raman gain induced mode evolution and on-demand coupling control in whispering-gallery-mode microcavities. Opt Express 2015;23:29573–83.10.1364/OE.23.029573Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Totsuka K, Tomita M. Optical microsphere amplification system. Opt Lett 2007;32:3197–9.10.1364/OL.32.003197Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Huet V, Rasoloniaina A, Guilleme P, et al. Millisecond photon lifetime in a slow-light microcavity. Phys Rev Lett 2016;116:133902.10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.133902Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Rasoloniaina A, Huet V, Nguyen TKN, et al. Controling the coupling properties of active ultrahigh-Q WGM microcavities from undercoupling to selective amplification. Sci Rep 2014;4:4023.10.1038/srep04023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Liu X-F, Lei F, Gao M, et al. Gain competition induced mode evolution and resonance control in erbium-doped whispering-gallery microresonators. Opt Express 2016;24:9550–60.10.1364/OE.24.009550Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Yang L, Vahala KJ. Gain functionalization of silica microresonators. Opt Lett 2003;28:592–4.10.1364/OL.28.000592Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Spillane SM, Kippenberg TJ, Painter OJ, Vahala KJ. Ideality in a fiber-taper-coupled microresonator system for application to cavity quantum electrodynamics. Phys Rev Lett 2003;91:043902.10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.043902Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Cai M, Painter O, Vahala KJ. Observation of critical coupling in a fiber taper to a silica-microsphere whispering-gallery mode system. Phys Rev Lett 2000;85:74.10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.74Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Carmon T, Yang L, Vahala KJ. Dynamical thermal behavior and thermal self-stability of microcavities. Opt Express 2004;12:4742–50.10.1364/OPEX.12.004742Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Braginsky VB, Gorodetsky ML, Ilchenko VS. Quality-factor and nonlinear properties of optical whispering-gallery modes. Phys Lett A 1989;137:393–7.10.1016/0375-9601(89)90912-2Suche in Google Scholar

[42] He L, Özdemir SK, Xiao Y-F, Yang L. Gain-induced evolution of mode splitting spectra in a high-Q active microresonator. IEEE J Quantum Electron 2010;46:1626–33.10.1109/JQE.2010.2055549Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Lei F, Peng B, Özdemir ŞK, Long GL, Yang L. Dynamic Fano-like resonances in erbium-doped whispering-gallery-mode microresonators. Appl Phys Lett 2014;105:101112.10.1063/1.4895632Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Purcell EM. Spontaneous emission probabilities at radio Frequencies. Phys Rev 1946;69:681.10.1007/978-1-4615-1963-8_40Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material:

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2018-0130).

©2018 Gui-Lu Long and Chuan Wang et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Glancing angle deposition meets colloidal lithography: a new evolution in the design of nanostructures

- Digital laser micro- and nanoprinting

- Magnetic hot-spot generation at optical frequencies: from plasmonic metamolecules to all-dielectric nanoclusters

- Nonlinear optical properties and applications of 2D materials: theoretical and experimental aspects

- Intraoperative biophotonic imaging systems for image-guided interventions

- Research Articles

- Broadband terahertz absorber based on dispersion-engineered catenary coupling in dual metasurface

- Gain lifetime characterization through time-resolved stimulated emission in a whispering-gallery mode microresonator

- Coherent surface plasmon amplification through the dissipative instability of 2D direct current

- Time-domain dynamics of reverse saturable absorbers with application to plasmon-enhanced optical limiters

- Large phase modulation of THz wave via an enhanced resonant active HEMT metasurface

- Design of aluminum nitride metalens for broadband ultraviolet incidence routing

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Glancing angle deposition meets colloidal lithography: a new evolution in the design of nanostructures

- Digital laser micro- and nanoprinting

- Magnetic hot-spot generation at optical frequencies: from plasmonic metamolecules to all-dielectric nanoclusters

- Nonlinear optical properties and applications of 2D materials: theoretical and experimental aspects

- Intraoperative biophotonic imaging systems for image-guided interventions

- Research Articles

- Broadband terahertz absorber based on dispersion-engineered catenary coupling in dual metasurface

- Gain lifetime characterization through time-resolved stimulated emission in a whispering-gallery mode microresonator

- Coherent surface plasmon amplification through the dissipative instability of 2D direct current

- Time-domain dynamics of reverse saturable absorbers with application to plasmon-enhanced optical limiters

- Large phase modulation of THz wave via an enhanced resonant active HEMT metasurface

- Design of aluminum nitride metalens for broadband ultraviolet incidence routing