Abstract

The next generation of flat optic devices aspires to a dynamic control of the wavefront characteristics. Here, we theoretically investigated the reconfigurable capabilities of an epsilon-near-zero (ENZ) metasurface augmented with resonant dielectric rods. We showed that the transmission spectrum of the metasurface is characterized by a Fano-like resonance, where the metasurface behavior changed from perfect magnetic conductor to epsilon-and-mu-near-zero material responses. The abrupt variation between these two extreme material responses suggests potential applications in dynamic metasurfaces. We highlighted the causality aspects of ENZ metasurfaces with a transient analysis and numerically investigated different reconfigurable mechanisms. Thus, this work introduces a new strategy for dynamic wavefront engineering.

1 Introduction

Metasurfaces are 2D (flat optics) devices composed of arrays of subwavelength elements with spatially varying phase, magnitude, and polarization responses [1]. They enable the control of the wavefront characteristics, with multiple functionalities including the manipulation of the usual refraction laws [2], [3], focusing [4], [5], cloaking [6], generating optical illusions [7], providing polarization control [8], or even performing mathematical operations [9]. Based on this principle, a number of practical devices have been demonstrated, including metalenses [10], [11], holograms [12], and quarter-wave plates [13], with performance comparable to those of conventional optical components. A more in-depth analysis of metasurfaces and their principle of operation and technological applications can be found in excellent reviews on the topic [1], [14], [15], [16], [17].

Inspired by the success of (passive and static) metasurfaces, the next generation of flat optic devices points toward a dynamic control of the wavefront. If possible, a real-time shaping of the wavefront will have a groundbreaking impact on holography and lidar technologies. For this reason, substantial efforts are being devoted to the development of dynamic metasurfaces, where the properties of their constituent unit cells are reconfigured with the use of electric [18], [19], optical [20], thermal [21], [22], magnetic [23], [24], and mechanical [25] actuators. In analogy with digital electronic systems, further evolutions of this concept might also lead to digital [26] and programmable [27] metamaterials and metasurfaces, into which different functionalities are encoded.

Here, we numerically investigate the potential of epsilon-near-zero (ENZ) media, i.e. a medium with near-zero permittivity [28], [29], [30], [31], for the development of reconfigurable metasurfaces. Previous works on ENZ metasurfaces have exploited their exotic properties to obtain highly directive beams [32], [33], perform beamforming and beamsteering tasks [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], and enhance their nonlinear response [39], [40], [41], [42]. Moreover, electrically tunable ENZ metasurfaces [18] have been demonstrated by exploiting the fact that the ENZ point lies at the transition between metal (opaque) and dielectric (transparent) responses. Here, we adopted a different approach to reconfigurable ENZ metasurfaces, which takes advantage of the peculiar behavior of particles immersed in ENZ media. In fact, we recently demonstrated that 2D particles immersed in a 2D ENZ medium behave as photonic “dopants”, which modify the effective permeability of the host while maintaining a near-zero permittivity [43]. This effect, we labeled as photonic doping, implies that the macroscopic parameters of a body can be reconfigured with a few and arbitrarily located particles.

Several aspects of the photonic doping theory might provide unique opportunities in the design of reconfigurable metasurfaces. (i) The effective medium description holds independently of the size of the unit cell. This implies that the response of a large metasurface can be controlled with one or very few actuators. (ii) The effective medium description also holds independently of the size, number, and/or position of the particles. This freedom in the geometry of the actuators can facilitate their integration. (iii) The effective material description is exact in the sense that it exactly recovers the same external fields at any point of space (even close to the external boundary). Therefore, one can benefit from all the properties of extreme material parameters such as epsilon-and-mu-near-zero (EMNZ) media and perfect magnetic conductor (PMC). (iv) The photonic doping theory is also valid for any shape of the host medium and/or unit cells, which could be exploited in the design of conformal or flexible metasurfaces.

Therefore, there is an obvious synergy between photonic doping and reconfigurable metasurfaces, which is the primary focus of this manuscript. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, we reviewed the concept of photonic doping and explored its possibilities to modify the transmission spectra of ENZ metasurfaces. Then, the transient analysis of ENZ metasurfaces is carried out in Section 3, which clarifies and highlights the causality aspects related to ENZ media and the theoretical lossless ENZ limit. Then, different reconfigurable mechanisms are investigated in Section 4. To finalize, conclusions and future directions are discussed in Section 5.

2 Photonic doping of ENZ metasurfaces – a brief review

We start our discussion by considering the ENZ metasurface schematically depicted in Figure 1A. In particular, the metasurface is composed of an ENZ (εh≈0) slab periodically loaded with (infinitely long) 2D dielectric rods of radius rp and relative permittivity εp, forming unit cells of size Lx×Ly. The photonic doping theory demonstrates that the response of this system can be described via effective permittivity εeff and permeability μeff regardless of the size of the unit cell and/or the cross-section of the dielectric rods [43]. Specifically, the effective permittivity of the ENZ host continues to be approximately zero εeff=εh≈0, whereas its effective permeability is given by the addition of the contributions from each of the particle/dopants μeff=1+∑pΔμp as if there were no interaction between them [43]. Moreover, the contribution from each particle is independent of its position:

![Figure 1: Transmission-reflection spectra of ENZ metasurfaces with photonic doping.(A) Sketch of the geometry: ENZ metasurface composed of rectangular unit cells of size Lx=1λp, Lx=2λp containing a 2D dielectric rod of radius rp=0.122λp and relative permittivity εp=10. The ENZ slab is modeled using a dispersive Drude model: εh=1−ωp2/(ω2+iωωc)${\varepsilon _h} = 1 - \omega _p^2/({\omega ^2} + i\omega {\omega _c})$ with ωc=0.03ωp. (B) Transmission and reflection spectra. Comparison between the results obtained with a full-wave numerical simulation [44] of the ENZ metasurface (solid) and its homogeneous equivalent with effective permittivity εeff and permeability μeff parameters (dashed). (C) Snapshot of the magnetic field distribution (z-component) at the EMNZ (ω=1.005ωp) and PMC (ω=0.993ωp) frequencies.](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2018-0012/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2018-0012_fig_001.jpg)

Transmission-reflection spectra of ENZ metasurfaces with photonic doping.

(A) Sketch of the geometry: ENZ metasurface composed of rectangular unit cells of size Lx=1λp, Lx=2λp containing a 2D dielectric rod of radius rp=0.122λp and relative permittivity εp=10. The ENZ slab is modeled using a dispersive Drude model:

By definition, the concept of photonic doping operates in a finite bandwidth where the host relative permittivity is sufficiently small (εh≈0). However, this bandwidth can be enough to accommodate narrower resonant effects and thus engineer the frequency dispersion of the metasurface. To assess the dispersive response of ENZ metasurfaces, we characterize ENZ host with a Drude-like dispersion model:

It is clear from the aforementioned properties that photonic doping is essentially different from conventional effective medium theories. In addition, the flexibility in geometry it provides (size, shape, and position of the particles and unit cell while allowing for homogenization) might provide new degrees of freedom in the design of metasurfaces. For instance, of particular interest is the case in which the dielectric rods are large enough to be resonant near the ENZ frequency. In this specific case, the response of the ENZ metasurface can be described via dispersive effective material parameters given by

and

It is clear from Equation (2) that doping with resonant dielectric rods results in effective permeability with a Lorentzian dispersion profile, where the resonance frequency corresponds to the rod’s monopolar resonance (ω0m such that

The transmission and reflection spectra of the proposed configuration were computed with a full-wave numerical solver [44] and it is depicted in Figure 1B. It can be concluded from the figure that the transmission spectrum is characterized by a minimum-maximum sequence. This Fano-like response could be explained as the interference between the broadband response of the ENZ slab and the narrowband response of the rod resonance. However, the transmission spectrum can be more clearly elucidated by means of the effective material parameters obtained in accordance with the photonic doping theory. We emphasize that this description is more comprehensive as it provides an exact representation of the fields external to the metasurface [43]. First, minimum transmission takes place at the resonant frequency ω=ω0m=0.993ωp, where the permeability is maximized. Thus, the slab behaves close to a PMC, i.e. a magnetic mirror, opaque to the incident waves, which minimizes the magnetic field (and maximizes the electric field) on its surface (see Figure 1C). Second, the maximum transmission corresponds to the antiresonance frequency ω=ωpm=1.005ωp, where the effective permeability approaches zero. Thus, the response of the slab is effectively similar to that of an EMNZ medium. This material is known to exhibit the so-called EMNZ tunneling [47] (in theory, perfect transmission with zero-phase advance), whose signature here is a transmission peak and whose value is determined by the loss of the ENZ host.

As a crosscheck of our effective material parameter description, Figure 2 includes a comparison of the effective material parameters obtained via numerical extraction methods [48] and those predicted by the photonic doping theory. It can be concluded from the figure that there is an excellent agreement between both numerical and theoretical values in a bandwidth around the ENZ frequency before the effective material description breaks down at higher frequencies. In addition, this analysis confirms that the effective permittivity is not changed by the rods, although they induced a Lorentzian effective permeability.

![Figure 2: Comparison between the effective (A) permittivity and (B) permeability, obtained via numerical parameter extraction from the reflection/transmission coefficients (dashed), and their theoretical values (solid).Numerical values are obtained with the method reported in Ref. [48]. Theoretical values correspond to a permittivity following a Drude model: ε(ω)=1−ωp2/(ω2+iωωc)$\varepsilon (\omega ) = 1 - \omega _p^2/({\omega ^2} + i\omega {\omega _c})$ with ωc=0.03ωp, and a permeability following a Lorenztian model: μ(ω)=(ω2−ωpm2+iωωcm)/(ω2−ω0m2+iωωcm)$\mu (\omega ) = ({\omega ^2} - \omega _{pm}^2 + i\omega {\omega _{cm}})/({\omega ^2} - \omega _{0m}^2 + i\omega {\omega _{cm}})$ with ω0m=0.9935ωp, ωpm=ωp, and ωcm=0.25ωc. The comparison illustrates how the numerical and theoretical values agree over a bandwidth around the plasma frequency before the effective model description breaks down at higher frequencies.](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2018-0012/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2018-0012_fig_002.jpg)

Comparison between the effective (A) permittivity and (B) permeability, obtained via numerical parameter extraction from the reflection/transmission coefficients (dashed), and their theoretical values (solid).

Numerical values are obtained with the method reported in Ref. [48]. Theoretical values correspond to a permittivity following a Drude model:

Thus, we find that doping the ENZ metasurfaces with resonant dielectric rods enables nontrivial modifications of its transmission spectrum, inducing Fano-like resonant response associated with extreme materials responses such as EMNZ and PMC media. This strongly frequency-dependent feature points toward a dynamic and reconfigurable metasurface that switches between opaque and transparent modes. Different strategies for reconfiguring the response of this metasurface are investigated in Section 4. This system might also find applications as a sensing platform, where local small changes on the properties of the dielectric rod results in amplified changes in the macroscopic response of the system (i.e. the transmission coefficient).

3 Transient analysis of ENZ metasurfaces

Exotic wave phenomena related to ENZ media usually raise questions about their causality aspects. After all, how can a zero-phase advance be sustained over arbitrarily long distances? Furthermore, if the response of the system is independent of the position of the particles, could we not move the particles further and further away until the delay becomes significant? If the group velocity is zero in lossless ENZ media [49], how does the wave goes through the material? All these questions and related concerns can be addressed with the same answer: these wave phenomena take place when a finite-size system is in steady state (i.e. after its transient response has passed). In this manner, a given transient time first passes before these steady-state effects are constructed, where all constrains imposed by causality and passivity are satisfied. Naturally, the more extreme the geometry is (e.g. the larger the area of the ENZ medium is or the further way the particles are), the longer it will take for the system to reach steady state. We note that similar questions concerning causality were raised at the beginning of negative-index metamaterial research, which were satisfactorily answered with the analysis of their transient response [50].

Therefore, here we further clarify the causal response of ENZ metasurfaces by carrying out a transient analysis of EMNZ tunneling enabled by photonic doping. To this end, we excite the configuration studied in Figure 1 with an ON-OFF pulse characterized by temporal profile:

with ω0=ωp and TON=100T0 and TON=1000T0 with T0=2π/ω0. This particular pulse shape has been selected so that our numerical simulations illustrate a complete cycle of interaction in which (i) the incident signal is turned on, (ii) the steady state is reached after a transient time, and (iii) the input signal is turned off and the energy stored in the systems progressively exits it. We numerically compute the transmitted signal by transforming the incident signal, given by Equation (3), into the frequency domain, applying the transmission coefficient obtained with a full-wave numerical solver [44] and applying the inverse Fourier transform. The slab parameters (Lx=1λp, Ly=2λp, εp=0.122λp, and rp=0.122λp) are selected so that the system effectively exhibits EMNZ tunneling exactly at its plasma frequency.

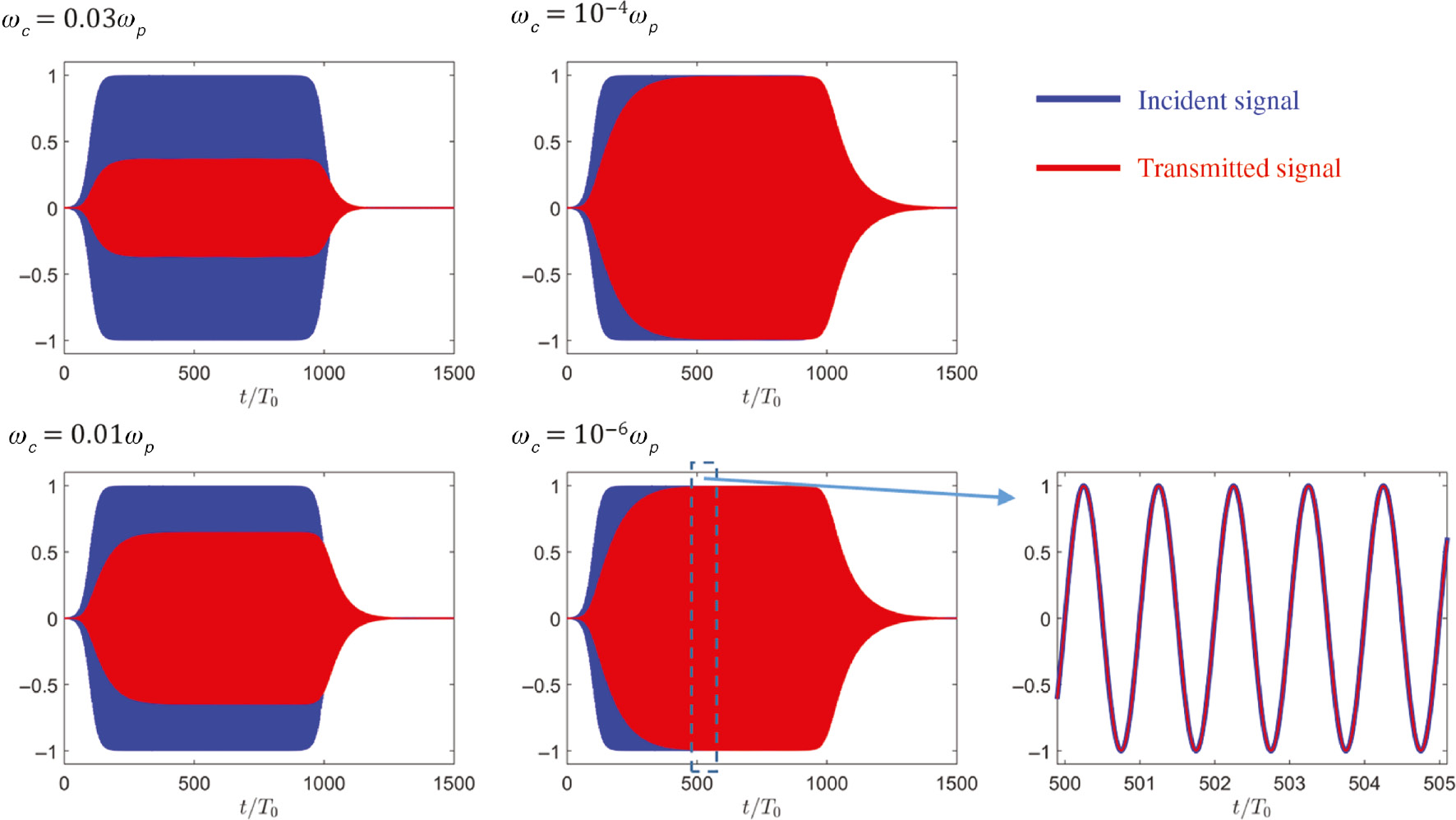

Figure 3 depicts the temporal profiles of the incident (blue) and transmitted (red) signals for different amounts of loss as prescribed by the collision frequencies ωc=0.03ωp, ωc=0.01ωp, ωc=10−4ωp, and ωc=10−6ωp. In doing so, we investigate the response of the system as it theoretically approaches to the lossless ENZ limit. In all these cases, we observe qualitatively similar dynamics. First, the input signal starts around TON and the transmitted signal progressively starts to grow and be constructed via multiple reflections. Interestingly, even when dissipation losses approach zero, the response of the system remains overdamped and no oscillations of the envelope are observed in the transmitted signal during transient time. We ascribe this effect to the dampening produced by radiation losses associated with the transmitted and reflected signals. Subsequently, steady state is reached and the amplitude of the transmitted signal stabilizes, so that it approximately behaves as a monochromatic signal. In this interval, the transmission coefficient can be identified based on the magnitude and delay between the incident and transmitted signals. Crucially, as dissipation losses approach zero, the response of the system converges to the same signal, which can be identified as the lossless (in the material sense) response of the system. Interestingly, as shown in the bottom right inset of the figure, the steady-state response of the system in this lossless limit corresponds to unit transmission with zero-phase advance, as expected from EMNZ tunneling. We note that although the group velocity vanishes in the lossless ENZ limit, this quantity plays no significant role in this scenario due to the finite size of the system. Finally, around TOFF, the incident signal is switched off. In this manner, the transmitted signal decays exponentially as the stored energy (due to the resonant nature of the transmission) leaves the system.

Transient response of ENZ metasurfaces with photonic doping.

Incident (blue) and transmitted (red) signals passing through an ENZ metasurface, photonically doped with a 2D dielectric rod discussed in Figure 1, for four increasingly small amounts of loss as prescribed by the collision frequencies ωc=0.03ωp, ωc=0.01ωp, ωc=10−4ωp, and ωc=10−6ωp. The incident signal corresponds to the ON-OFF pulse described in Equation (3). Numerical simulations describe how the tunneling effect is established after a transient time is passed once the incident pulse is switched on and how the energy of the system is released after the pulse is switched off. The right bottom inset includes a zoom-in on the incident and transmitted signals once the steady state of the system has been established. The steady-state response of the system is characterized by EMNZ tunneling, i.e. near-unity transmission with zero-phase advance.

Despite its simplicity, our numerical example serves to highlight and clarify the main aspects related to the transient response of ENZ metasurfaces: (i) how an output signal with zero-phase variation is constructed during the transient process, (ii) how energy can be transmitted through a finite-size ENZ body even if the medium exhibits zero group velocity in the lossless limit, and (iii) how the response of the system smoothly converges to the lossless ENZ response as dissipation losses decrease.

4 Reconfigurable mechanisms

The fact that the response of the metasurface can be controlled with a single or a very diluted mixture of randomly located particles suggests exciting possibilities in the development of reconfigurable metasurfaces. First, the fact that the unit cell composing the metasurfaces can span several wavelengths will reduce the number of reconfiguring units. Second, as the particles themselves can be made large too, extra space can be used to include a tuning device. Third, the fact that the response of the system is independent of the position of the particles might ease some potential fabrication constraints and facilitate its integration. In this section, we provide a number of numerical examples to illustrate the potential of different reconfigurable mechanisms for ENZ metasurfaces.

4.1 Dielectric rod actuator

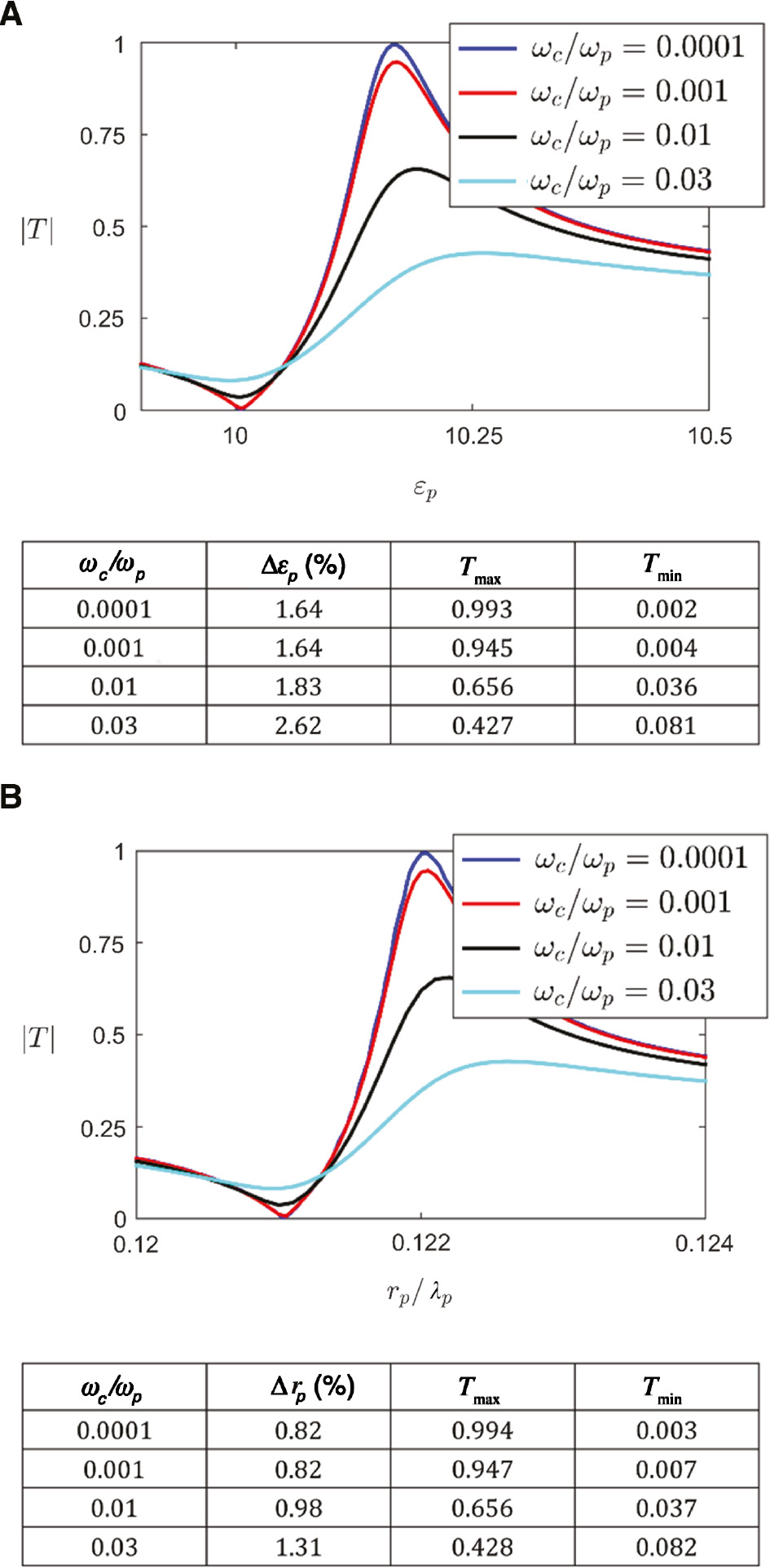

Conceptually, the most straightforward approach to tune the response of the metasurface is to directly change the characteristics of the dielectric rod, i.e. its permittivity εp and radius rp. Figure 4 gathers a parametric analysis of the transmission coefficient as a function of the permittivity and radius of the dielectric rod for the configuration studied in Figure 1, for different amounts of loss characterized by the collision to plasma frequency ratio ωc/ωp. Intuitively, increasing the rod permittivity and/or radius (while keeping the operating frequency fixed) is similar to increasing the frequency of operation (for a given rod permittivity and/or radius) in Figure 1B. Therefore, we find from Figure 4 that as the rod permittivity and/or radius is increased, the transmission coefficient undergoes a minimum-maximum transition, associated with the PMC and EMNZ points, similar to what was observed in its spectrum in Figure 1B. More quantitatively, it is found that for low loss it would be possible to switch the metasurface from opaque (Tmin=0.002) to transparent (Tmax=0.993) configurations with a small percentage change of the rod permittivity,

Switching ENZ metasurfaces photonically doped with a single actuator.

Transmission coefficient as a function of variations of the rod (A) permittivity (with rp=0.121λp fixed) and (B) radius (with εp=10 fixed) for different amounts of loss. Inset tables include data for the maxima and minima transmission coefficients and the percentage permittivity and radius variation between them. The geometry of the metasurface corresponds to the system analyzed in Figure 1. The numerical simulations illustrate the possibility of switching on and off the transmission through an ENZ metasurface with small percentage variations of the characteristics of the particles.

These numerical results provide a first quantitative estimation of the order of magnitude of the quantities involved. However, these configurations are not optimized and a better performance will be obtained with more sophisticated designs (for example, using a heterogeneous rod or a different rod cross-section). Different strategies could also be used in practice to implement these permittivity and radius changes. On the one hand, nonlinear materials (e.g. Kerr-effect [51] and phase change [21], [52], [53], [54] materials) can provide permittivity changes. Here, a design procedure for the reconfigurable metasurface might include integrating the nonlinear medium in the regions within the dielectric rod where the electric field is maximized (i.e. at the boundary of the dielectric rod), so that the interaction of the nonlinear material with the incoming light is maximized. Interestingly, we note that as the response of the metasurface is independent of the position of the rod, its response will remain reciprocal even if it is nonlinear and with a highly asymmetric geometry. On the other hand, changes in the rod radius could be induced via thermal expansion. Again, one could directly use a homogeneous rod or take advantage of a heterogeneous rod, in which the dielectric rod is covered by a material with a large thermal expansion coefficient. The design of these reconfigurable mechanisms is specific to each one of them and left for future efforts.

4.2 Microfluidics

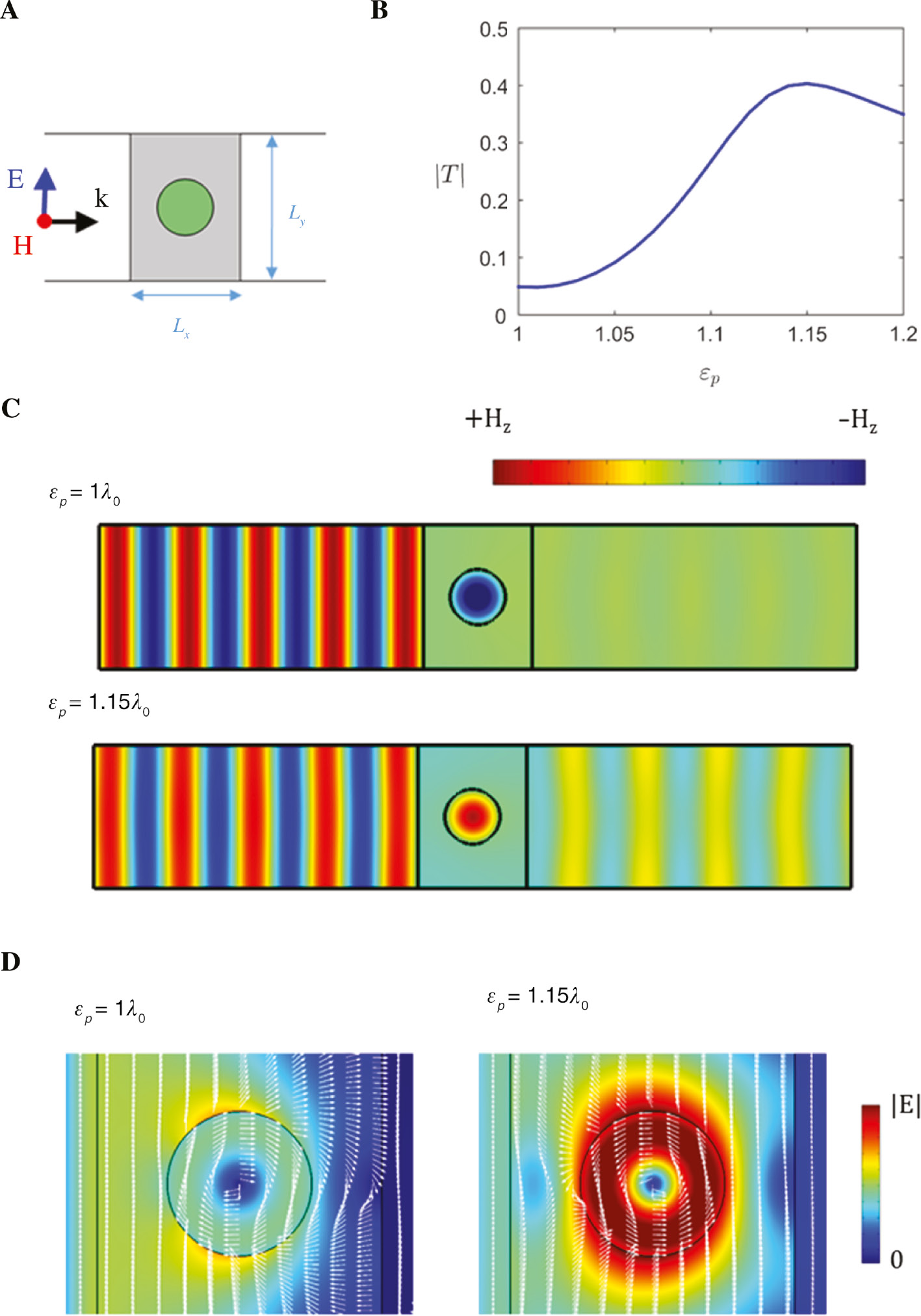

One can also take advantage of the fact that, within the photonic doping paradigm, the description with effective parameters holds even for particles with a size comparable to the wavelength of operation. This enables the use of low relative permittivity resonators, with potential application in microfluidics. For example, we could consider the extreme case in which the dielectric rod is actually a resonant vacuum (or air) channel (εp=1, rp=0.381λp). Then, a liquid could circulate through this channel, increasing the value of εp. Ideally, the transmission through the metasurface should be switched from minimum to maximum with small permittivity values. Figure 5B depicts the magnitude of the transmission coefficient as a function of the channel permittivity for this configuration. Again, the response of the system is characterized by a minimum-maximum transition, switching from Tmin=0.048 to Tmax=0.403 as the permittivity is increased from εp=1 (vacuum) to εp=1.15. Therefore, these numerical simulations confirm that the ENZ metasurface can operate even when hosting relatively large (rp=0.381λp) and low-permittivity resonators. Interestingly, the system can still be described with effective parameters. This effect is illustrated by the behavior of the transmission coefficient shown in Figure 5B as well as in the field distributions depicted in Figure 5C, corresponding to the (lossy) PMC and EMNZ points.

ENZ metasurfaces for microfluidics.

(A) Sketch of the geometry: ENZ metasurface composed of rectangular unit cells of size Lx=1.5λp, Lx=2λp containing a vacuum (or air) rod of radius rp=0.381λp. We assume that a fluid with low-permittivity εp flows along the rod axis facilitating its inspection with an external field. (B) Transmission coefficient as a function of the relative permittivity of the fluid. (C) Snapshot of the magnetic field distribution for εp=1 and εp=1.15 corresponding to the minimum and maximum of transmission, respectively. (D) Electric field distribution (color map of the field magnitude and normalized vectorial plot) characterized by resonantly enhanced circulating fields within the microfluidic channel.

Other aspects of ENZ metasurfaces might also be of interest for microfluidics. In particular, inspecting the electric field distribution on the channel (see Figure 5D) reveals that it is dominated by a resonantly enhanced and circulating (divergence-free) field distribution. We remark that this effect is qualitatively different from the usual enhancement of localized electric fields (e.g. nanoantennas or plasmonic nanoparticles [55], [56]), which rely on charge accumulation and thus exhibit field lines arising from the boundaries of the particles. In contrast, here we have a localized and enhanced electric field that nevertheless preserves a divergence-free characteristics near the boundary of the channel. This strong circulating electric field could be used to manipulate the particles flowing through the channel with via the optical forces exerted by them. Due to its circulating character, gradient forces would trap the particles within a closed-loop path. One can envision how this effect could be used to link the orbital angular momentum of the particles flowing through the channel to their interaction with the incoming light.

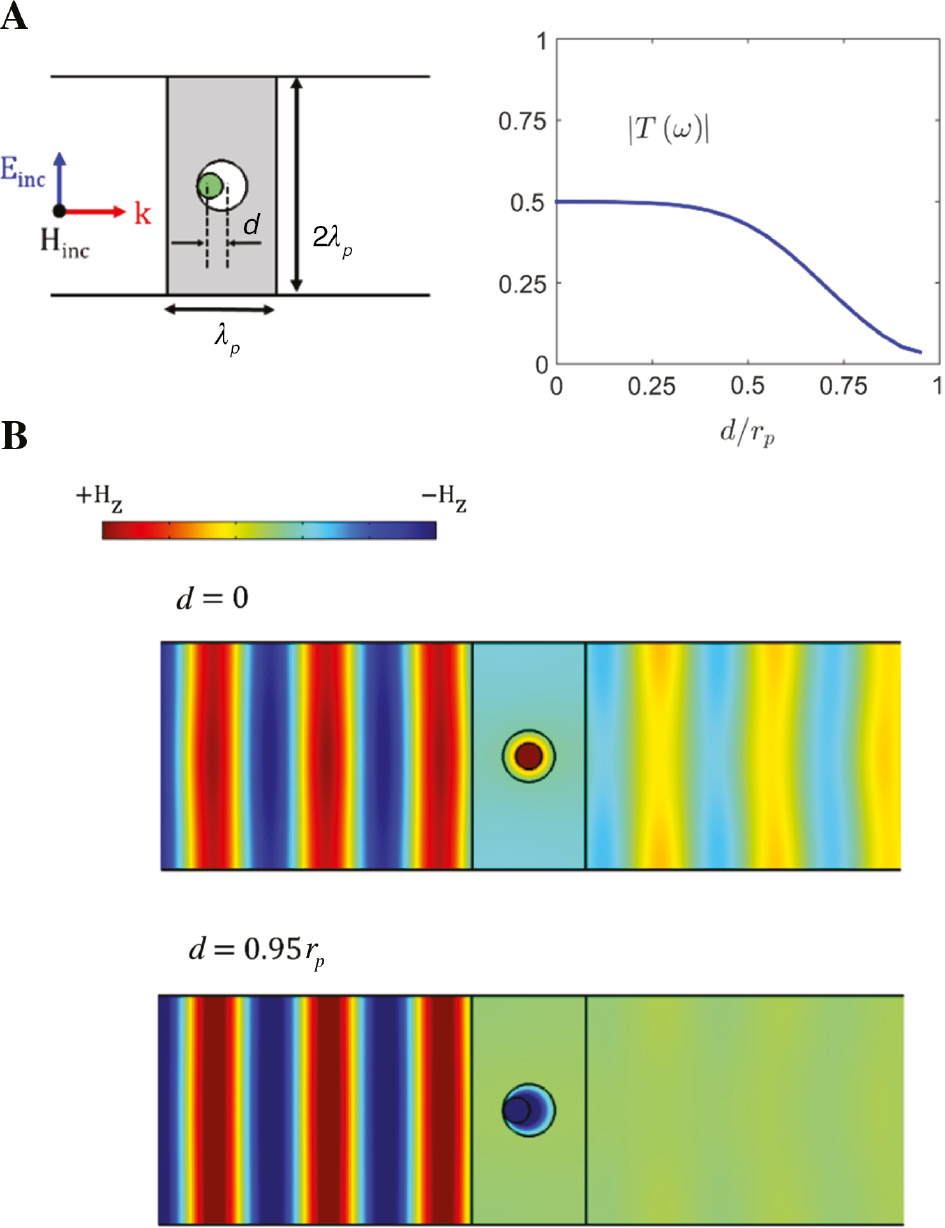

4.3 Mechanical actuators

A dynamic control of the characteristics of the particles within the ENZ metasurface could also be implemented via changes on their geometry induced by mechanical actuators. As an example, we consider the case in which the dielectric rod (εp=10, rp=0.114λp) is itself immersed in a vacuum channel of twice its radius (εc=1, rc=2rp). We assume that a mechanical actuator will allow us to shift the position of the rod from the center to the boundary of the vacuum channel. Due to symmetry considerations and the preferred excitation of the monopole mode, the direction in which the dielectric rod is shifted from the center of the vacuum channel has a negligible impact on the performance of the system. Figure 6 depicts the predicted transmission coefficient as a function of the position of the dielectric rod. It can be concluded from the numerical simulation that switching the rod position from the center (d=0rp) to the side (d=0.95rp) of the vacuum channels shifts the transmission coefficient from Tmax=0.5 to Tmin=0.036.

Tuning ENZ metasurfaces photonically doped with mechanical actuators.

(A) Sketch of the geometry: ENZ rectangular unit cell of size 2λp×λp containing a dielectric rod of radius rp=0.114λp and relative permittivity εp=10, which is located within a vacuum rod of radius 2rp. The transmission of the metasurface is modulated by shifting the position of the dielectric rod a distance d from the center of the vacuum rod. Magnitude of the transmission coefficient as a function of the position of the dielectric rod. (B) Snapshot of the magnetic field distribution at the position for the positions (B-top) d=0 (maximal transmission) and (B-bottom) d=0.95rp (minimal transmission). The numerical simulations illustrate the possibility of modulating the transmission coefficient from 0.5 to nearly 0 with the use of a mechanical actuator.

Interestingly, the performance in this case is better than that reported in Section 4.1 for the homogeneous dielectric rod. In particular, the top transmission coefficient is 7% larger than in the homogeneous case. This enhancement in the performance can be explained by inspecting the fields excited in the structure (see Figure 6B). It can be concluded from the figure that the air gap around the rod acts as a separation between the resonant cylinder and the dielectric host. This separation enhances the decoupling between the resonator and ENZ host fields, reducing the power dissipated in the ENZ host and increasing the quality factor of the resonant transmission. Overall, this result illustrates the possibility of optimizing the performance of the system with the electromagnetic design of the actuator, which may have potential applications in microelectromechanical and nanoelectromechanical devices.

5 Conclusions

We investigated theoretically the reconfigurable capabilities of ENZ metasurfaces augmented with resonant dielectric rods. Using the photonic doping theory, we showed that the transmission spectrum of this metasurface is characterized by a Fano-like resonance, whose minima and maxima features correspond to PMC and EMNZ material responses. This spectral response can be reconfigured by changing the properties of the particles, which benefit from the rapid spectral variation between opaque (PMC) and transparent (EMNZ) conditions. We analyzed several reconfigurable mechanisms, illustrating how their implementation could benefit from the fact that both the unit cell and the particles can be larger than the wavelength while still preserving the description with effective parameters.

Future investigations might consider doping the metasurface with rods of different sizes and characteristics, which will enable more complex spectral responses that can be harnessed to further enhance the reconfiguration performance. In addition, because photonic doping works independently of the shape of the ENZ host, future investigations could take advantage of this property to develop conformal or even flexible dynamic metasurfaces.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the partial support from the Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship program sponsored by the Basic Research Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering and funded by the Office of Naval Research (grant N00014-16-1-2029) and partial support from the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiatives (grant FA9550-14-1-0389). I.L. acknowledges support from Juan de la Cierva-Incorporación Fellowship. Y.L. acknowledges partial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 61771280).

References

[1] Yu N, Capasso F. Flat optics with designer metasurfaces. Nat Mater 2014;13:139–50.10.1038/nmat3839Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Yu N, Genevet P, Kats MA, et al. Light propagation with phase discontinuities: generalized laws of reflection and refraction. Science 2011;334:333–7.10.1126/science.1210713Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Ni X, Emani NK, Kildishev AV, Boltasseva A, Shalaev VM. Broadband light bending with plasmonic nanoantennas. Science 2012;335:427.10.1126/science.1214686Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Aieta F, Genevet P, Kats MA, et al. Aberration-free ultrathin flat lenses and axicons at telecom wavelengths based on plasmonic metasurfaces. Nano Lett 2012;12:4932–6.10.1021/nl302516vSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Monticone F, Estakhri NM, Alù A. Full control of nanoscale optical transmission with a composite metascreen. Phys Rev Lett 2013;110:1–5.10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.203903Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Ni X, Wong ZJ, Mrejen M, Wang Y, Zhang X. An ultrathin invisibility skin cloak for visible light. Science 2015;349:1310–4.10.1126/science.aac9411Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Teo JYH, Wong LJ, Molardi C, Genevet P. Controlling electromagnetic fields at boundaries of arbitrary geometries. Phys Rev A 2016;94:23820.10.1103/PhysRevA.94.023820Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Desiatov B, Mazurski N, Fainman Y, Levy U. Polarization selective beam shaping using nanoscale dielectric metasurfaces. Opt Express 2015;23:22611.10.1364/OE.23.022611Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Silva A, Monticone F, Castaldi G, Galdi V, Alù A, Engheta N. Performing mathematical operations with metamaterials. Science 2014;343:160–4.10.1126/science.1242818Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Khorasaninejad M, Chen WT, Devlin RC, Oh J, Zhu AY, Capasso F. Metalenses at visible wavelengths: diffraction-limited focusing and subwavelength resolution imaging. Science 2016;352:1190–4.10.1126/science.aaf6644Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Lalanne P, Chavel P. Metalenses at visible wavelengths: past, present, perspectives. Laser Photonics Rev 2017;3:1600295.10.1002/lpor.201600295Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Ozaki M, Kato J, Kawata S. Surface-plasmon holography with white-light illumination. Science 2011;332:218–20.10.1126/science.1201045Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Yu N, Aieta F, Genevet P, Kats MA, Gaburro Z, Capasso F. A broadband, background-free quarter-wave plate based on plasmonic metasurfaces. Nano Lett 2012;12:6328–33.10.1021/nl303445uSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Genevet P, Capasso F, Aieta F, Khorasaninejad M, Devlin R. Recent advances in planar optics: from plasmonic to dielectric metasurfaces. Optica 2017;4:139.10.1364/OPTICA.4.000139Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Glybovski SB, Tretyakov SA, Belov PA, Kivshar YS, Simovski CR. Metasurfaces: from microwaves to visible. Phys Rep 2016;634:1–72.10.1016/j.physrep.2016.04.004Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Zhu AY, Kuznetsov AI, Luk’Yanchuk B, Engheta N, Genevet P. Traditional and emerging materials for optical metasurfaces. Nanophotonics 2017;6:452–71.10.1515/nanoph-2016-0032Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Khorasaninejad M, Chen WT, Zhu AY, et al. Visible wavelength planar metalenses based on titanium dioxide. IEEE J Sel Top Quant Electron 2017;23:4700216.10.1109/JSTQE.2016.2616447Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Huang YW, Lee HWH, Sokhoyan R, et al. Gate-tunable conducting oxide metasurfaces. Nano Lett 2016;16:5319–25.10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b00555Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Park J, Kang JH, Kim SJ, Liu X, Brongersma ML. Dynamic reflection phase and polarization control in metasurfaces. Nano Lett 2017;17:407–13.10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04378Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Kinsey N, DeVault C, Kim J, Ferrera M, Shalaev VM, Boltasseva A. Epsilon-near-zero Al-doped ZnO for ultrafast switching at telecom wavelengths. Optica 2015;2:616–22.10.1364/OPTICA.2.000616Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Driscoll T, Kim H-T, Chae B-G, et al. Memory metamaterials. Science 2009;325:1518–21.10.1126/science.1176580Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Ou JY, Plum E, Jiang L, Zheludev NI. Reconfigurable photonic metamaterials. Nano Lett 2011;11:2142–4.10.1021/nl200791rSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Labrador A, Gómez-Polo C, Pérez-Landazábal JI, et al. Magnetotunable left-handed FeSiB ferromagnetic microwires. Opt Lett 2010;35:2161–3.10.1364/OL.35.002161Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Liberal I, Nefedov IS, Ederra I, Gonzalo R, Tretyakov SA. Reconfigurable artificial surfaces based on impedance loaded wires close to a ground plane. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 2012;60:1921–30.10.1109/TAP.2012.2186264Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Pryce IM, Aydin K, Kelaita YA, Briggs RM, Atwater HA. Highly strained compliant optical metamaterials with large frequency tunability. Nano Lett 2010;10:4222–7.10.1021/nl102684xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Della Giovampaola C, Engheta N. Digital metamaterials. Nat Mater 2014;13:1115–21.10.1038/nmat4082Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Cui TJ, Qi MQ, Wan X, Zhao J, Cheng Q. Coding metamaterials, digital metamaterials and programmable metamaterials. Light Sci Appl 2014;3:e218.10.1038/lsa.2014.99Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Liberal I, Engheta N. Near-zero refractive index photonics. Nat Photon 2017;11:149–58.10.1038/nphoton.2017.13Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Engheta N, Ziolkowski RW. Metamaterials: physics and engineering explorations. Piscataway, NJ, John Wiley & Sons, 2006.10.1002/0471784192Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Silveirinha MG, Engheta N. Tunneling of electromagnetic energy through subwavelength channels and bends using e-near-zero materials. Phys Rev Lett 2006;97:157403.10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.157403Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Liberal I, Engheta N. The rise of near-zero-index technologies. Science 2017;358:1540–1.10.1126/science.aaq0459Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Enoch S, Tayeb G, Sabouroux P, Guérin N, Vincent P. A metamaterial for directive emission. Phys Rev Lett 2002;89:213902.10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.213902Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Ziolkowski RW. Propagation in and scattering from a matched metamaterial having a zero index of refraction. Phys Rev E 2004;70:46608.10.1103/PhysRevE.70.046608Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Alù A, Silveirinha MG, Salandrino A, Engheta N. Epsilon-near-zero metamaterials and electromagnetic sources: tailoring the radiation phase pattern. Phys Rev B 2007;75:155410.10.1103/PhysRevB.75.155410Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Pacheco-Peña V, Torres V, Orazbayev B, et al. Mechanical 144GHz beam steering with all-metallic epsilon-near-zero lens antenna. Appl Phys Lett 2014;105:243503.10.1063/1.4903865Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Torres V, Orazbayev B, Pacheco-Peña V, et al. Experimental demonstration of a millimeter-wave metallic ENZ lens based on the energy squeezing principle. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag 2015;63:231–9.10.1109/TAP.2014.2368112Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Pacheco-Peña V, Torres V, Beruete M, Navarro-Cía M, Engheta N. e-near-zero (ENZ) graded index quasi-optical devices: steering and splitting millimeter waves. J Opt 2014;16:94009.10.1088/2040-8978/16/9/094009Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Soric JC, Alù A. Longitudinally independent matching and arbitrary wave patterning using e-near-zero channels. IEEE Trans Microw Theory Tech 2015;63:3558–67.10.1109/TMTT.2015.2479589Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Argyropoulos C, Chen PY, D’Aguanno G, Engheta N, Alù A. Boosting optical nonlinearities in e-near-zero plasmonic channels. Phys Rev B 2012;85:45129.10.1103/PhysRevB.85.045129Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Capretti A, Wang Y, Engheta N, Dal Negro L. Comparative study of second-harmonic generation from epsilon-near-zero indium tin oxide and titanium nitride nanolayers excited in the near-infrared spectral range. ACS Photonics 2015;2:1584–91.10.1021/acsphotonics.5b00355Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Alam MZ, De Leon I, Boyd RW. Large optical nonlinearity of indium tin oxide in its epsilon-near-zero region. Science 2016;352:6287.10.1126/science.aae0330Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Caspani L, Kaipurath RP, Clerici M, et al. Enhanced nonlinear refractive index in e-near-zero materials. Phys Rev Lett 2016;116:233901.10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.233901Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Liberal I, Mahmoud AM, Li Y, Edwards B, Engheta N. Photonic doping of epsilon-near-zero media. Science 2017;355:1058–62.10.1126/science.aal2672Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] The numerical calculations were all performed in COMSOL Multiphysics 5.0, 2016. Available at: www.comsol.com.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Caldwell JD, Lindsay L, Giannini V, et al. Low-loss, infrared and terahertz nanophotonics using surface phonon polaritons. Nanophotonics 2015;4:44–68.10.1515/nanoph-2014-0003Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Kim J, Dutta A, Naik GV, et al. Role of epsilon-near-zero substrates in the optical response of plasmonic antennas. Optica 2016;3:339.10.1364/OPTICA.3.000339Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Mahmoud AM, Engheta N. Wave-matter interactions in epsilon-and-mu-near-zero structures. Nat Commun 2014;5:5638.10.1038/ncomms6638Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Luukkonen O, Maslovski SI, Tretyakov SA. A stepwise Nicolson-Ross-Weir material parameter extraction method. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag Lett 2011;10:1295–8.10.1109/LAWP.2011.2175897Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Javani MH, Stockman MI. Real and imaginary properties of epsilon-near-zero materials. Phys Rev Lett 2016;117:107404.10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.107404Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Ziolkowski RW, Heyman E. Wave propagation in media having negative permittivity and permeability. Phys Rev E 2001;64:56625.10.1103/PhysRevE.64.056625Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Boyd RW. Nonlinear optics. Burlington, MA, Academic Press, 2003.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Verleur HW, Barker AS, Berglund CN. Optical properties of VO2 between 0.25 and 5 eV. Rev Mod Phys 1968;172:788–98.10.1103/PhysRev.172.788Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Li P, Yang X, Maß TWW, et al. Reversible optical switching of highly confined phonon-polaritons with an ultrathin phase-change material. Nat Mater 2016;15:870–5.10.1038/nmat4649Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Wang Q, Rogers ETF, Gholipour B, et al. Optically reconfigurable metasurfaces and photonic devices based on phase change materials. Nat Photon 2015;10:60–5.10.1038/nphoton.2015.247Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Biagioni P, Huang J-S, Hecht B. Nanoantennas for visible and infrared radiation. Rep Prog Phys 2012;75:24402.10.1088/0034-4885/75/2/024402Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Novotny L, van Hulst N. Antennas for light. Nat Photon 2011;5:83–90.10.1038/nphoton.2010.237Suche in Google Scholar

©2018 Nader Engheta et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial

- Metasurfaces – from science to applications

- Review articles

- The future and promise of flat optics: a personal perspective

- Material platforms for optical metasurfaces

- Metasurfaces and their applications

- Controlling the phase of optical nonlinearity with plasmonic metasurfaces

- Molding light with metasurfaces: from far-field to near-field interactions

- A review of dielectric optical metasurfaces for wavefront control

- Bianisotropic metasurfaces: physics and applications

- Design, concepts, and applications of electromagnetic metasurfaces

- Reconfigurable epsilon-near-zero metasurfaces via photonic doping

- A review of gap-surface plasmon metasurfaces: fundamentals and applications

- Dimerized high contrast gratings

- Metasurface holography: from fundamentals to applications

- Wavefront manipulation by acoustic metasurfaces: from physics and applications

- Huygens’ metasurfaces from microwaves to optics: a review

- Nonconventional metasurfaces: from non-Hermitian coupling, quantum interactions, to skin cloak

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial

- Metasurfaces – from science to applications

- Review articles

- The future and promise of flat optics: a personal perspective

- Material platforms for optical metasurfaces

- Metasurfaces and their applications

- Controlling the phase of optical nonlinearity with plasmonic metasurfaces

- Molding light with metasurfaces: from far-field to near-field interactions

- A review of dielectric optical metasurfaces for wavefront control

- Bianisotropic metasurfaces: physics and applications

- Design, concepts, and applications of electromagnetic metasurfaces

- Reconfigurable epsilon-near-zero metasurfaces via photonic doping

- A review of gap-surface plasmon metasurfaces: fundamentals and applications

- Dimerized high contrast gratings

- Metasurface holography: from fundamentals to applications

- Wavefront manipulation by acoustic metasurfaces: from physics and applications

- Huygens’ metasurfaces from microwaves to optics: a review

- Nonconventional metasurfaces: from non-Hermitian coupling, quantum interactions, to skin cloak