Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) actively participate in crucial cellular processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and communication. GPCRs play a pivotal role in the initiation and progression of tumors. In this review, focusing on non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), one of the most prevalent cancers, we highlight the roles of GPCRs including understudied receptors in cancer oncogenesis and progression. We summarize current knowledge on GPCR functions in NSCLC, detailing their contributions to tumor development, progression, and therapy resistance. Furthermore, we evaluate the therapeutic potential of agents targeting GPCR-driven tumorigenic signaling in lung cancer. Critical knowledge gaps in understanding GPCR involvement in NSCLC biology are identified, and we address the limitations and challenges of targeting GPCRs for NSCLC treatment. This review provides insights into the current landscape, recent progress, and persisting challenges in developing GPCR-targeted anticancer therapies.

Introduction

According to the Global Cancer Statistics 2022 report, cancer remains a major health problem worldwide. In 2022, there were nearly 20 million new cancer diagnoses and approximately 9.7 million cancer-related deaths [1], 2]. Lung cancer is one of the most serious diseases associated with cancer-related mortality. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the major histologic subtype of lung cancer accounting for approximately 85 % of all lung cancers [2], 3]. In recent decades, significant progress has been made in the prevention and detection of NSCLC. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) belongs to the insulin receptor superfamily and plays a significant role in various cancers. The evaluation of the ALK inhibitors approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for advanced NSCLC highlights their unique effectiveness and safety. Their significant progression-free survival (PFS), enhanced activity in the central nervous system (CNS), and outstanding patient-reported outcomes make them stand out. Although their efficacy is remarkable, there are still obstacles in achieving personalized treatment [4]. Because of the great heterogeneity of NSCLC, the proportion of patients who respond to such treatments remains low, and the duration of response is often short [5]. Consequently, the five-year survival rate of patients with NSCLC is invariably low [2]. No molecular biomarkers are available for distinguishing patients with NSCLC at various stages. Therefore, further investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the initiation and progression of NSCLC and exploration of more effective predictive biomarkers and therapeutic targets are urgently needed.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest family of membrane receptors and play an important role in cell signaling transduction. They play critical roles in differentiation, cell growth, angiogenesis, inflammation, metabolic diseases and viral infection [6], [7], [8]. Dysregulated expression and dysfunction of GPCRs are closely related to many diseases and pathophysiological processes, rendering GPCRs a prime target for pharmaceutical drug development [9], 10]. Currently, GPCRs represent one of the most “druggable” classes of molecules, representing approximately 30 % of all therapeutics on the market, there are relatively few cancer treatments targeting GPCRs [11], [12], [13], [14]. However, at present, the use of drugs targeting GPCRs in cancer treatment remains limited. Only a few drugs are used in clinical settings, while many others are in clinical trials. Especially for NSCLC (non-small cell lung cancer), the available drugs are extremely limited. Although the involvement of GPCRs in NSCLC has not been fully elucidated, accumulating evidence indicates that GPCRs play a crucial role in the tumorigenesis and progression of NSCLC and may be a candidate therapeutic target for advanced NSCLC.

In this review, we focus on the advancements in the functions and mechanisms of six GPCRs (GPR78, Protease-activated receptor 2 [PAR2], C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 [CXCR4], GPBAR1, G protein-coupled receptor, class C, group 5, member A [GPRC5A], Somatostatin receptor type 2 [SSTR2]) in the progression and chemotherapy resistance of NSCLC. We further highlight the therapeutic potential of selected drugs targeting GPCR-driven tumorigenic signaling pathways. Finally, we highlight specific GPCRs as promising therapeutic targets to inhibit NSCLC tumor growth and propose future research directions in this field.

General overview of GPCRs

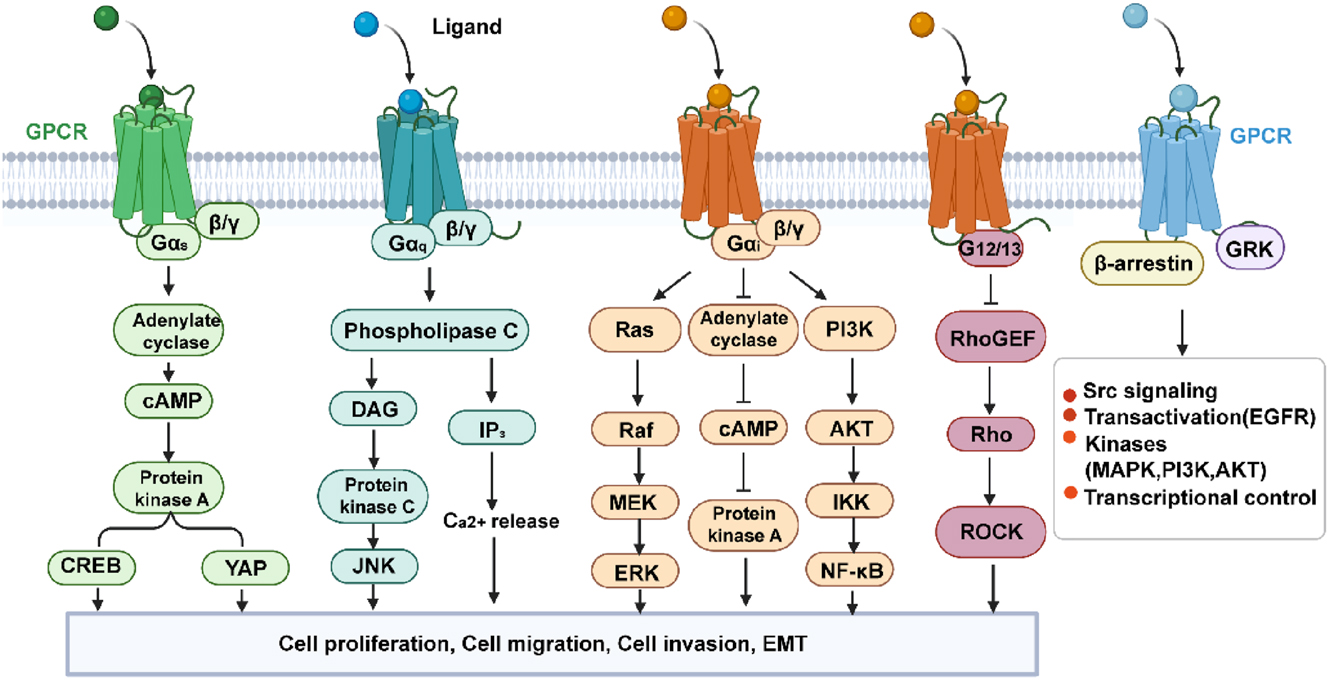

GPCRs constitute the largest and most diverse protein family in the human genome with over 800 members identified to date. GPCR modulators represent at least one-third of all clinically marketed drugs [15]. Once a GPCR is activated, its rapid conformational changes allow it to couple with a Gα, Gβ, and Gγ-containing heterotrimeric G-protein, which anchors at the inner face of the plasma membrane. GDP is displaced by GTP, allowing the dissociation of the Gα subunit from the βγ dimer subunit [16]. Both subunit complexes prompt a network of intracellular effectors, including second messenger-generating systems, small GTPases, and kinase cascades, such as Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)/Protein Kinase B (AKT), thus leading to various signaling cascades. Depending on the sequence similarity of the α subunit type (i.e., Gαs, Gαi/o, Gαq/11), the coupling of GPCR to a distinct G protein may affect diverse intracellular signaling pathways and determine distinct cell fates. In addition to G proteins, GPCRs can signal through G protein-independent pathways that may involve G protein receptor kinases (GRKs) and β-arrestins [17] (Figure 1). Dysregulation of these pathways may result in extended cell survival and uncontrolled proliferation, ultimately contributing to the development of the cancer phenotype [18], 19]. Here, we have listed the major G protein-coupled receptor families related to tumors, their representative ligands, and the associated physiological functions (Table 1). To study the distribution of established and currently investigated drug targets, we mapped approved drugs and clinical trial candidates onto the Table 2. It is foreseeable that, as candidate drugs advance in clinical trials and gain approval, the publicly available information on orphan receptors will increase.

GPCR effector pathways. GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor. (Created with BioRender.com).

The GPCR signaling pathway transmits activated receptor signals to intracellular targets through heterotrimeric G proteins. Upon ligand binding, the Gα subunit exchanges GDP for GTP and dissociates from the Gβγ dimer, each of which can regulate distinct effectors such as adenylyl cyclase, phospholipase C, ion channels, or MAP-kinase cascades. GPCRs can also signal through alternative pathways involving GRKs and β-arrestins. Dysregulation of these pathways may lead to prolonged cell survival and uncontrolled proliferation, ultimately contributing to the formation of a cancer phenotype.

GPCRs exert both oncogenic and tumor-suppressive functions in NSCLC

Owing to the pivotal and indispensable roles of GPCRs in tumorigenesis, researchers have recently attempted to understand the relationship between GPCRs and NSCLC. Emerging experimental and clinical data indicate that GPCR dysfunction of GPCRs are tightly linked to the initiation and progression of NSCLC, such as C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) [20], 21], and CXCR4 [22], 23]. The corresponding ligands and signaling pathways that regulate their functions have been deciphered. Several GPCRs are currently being pursued as potential targets for anticancer treatment [24].These findings may provide potential avenues for the development of novel GPCR-based therapeutic strategies for cancer diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Based on the available data, we grouped GPCRs into oncogenic and tumor-suppressive GPCRs according to their known and potential roles in NSCLC.

Oncogenic GPCRs in NSCLC

GPR78 promotes migration and metastasis

Some GPCRs have a structure similar to that of other identified receptors, but their endogenous selective and exclusive ligand(s) are currently unknown; therefore they are called orphan GPCRs. GPR78 is an orphan G-protein coupled receptor containing 363 amino acids and belongs to the class A family. GPR78 shares 51 % amino acid sequence identity with GPR26. In the analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset, GPR78 was identified as a potential prognostic marker for oral squamous cell carcinoma and gastric carcinoma [25].

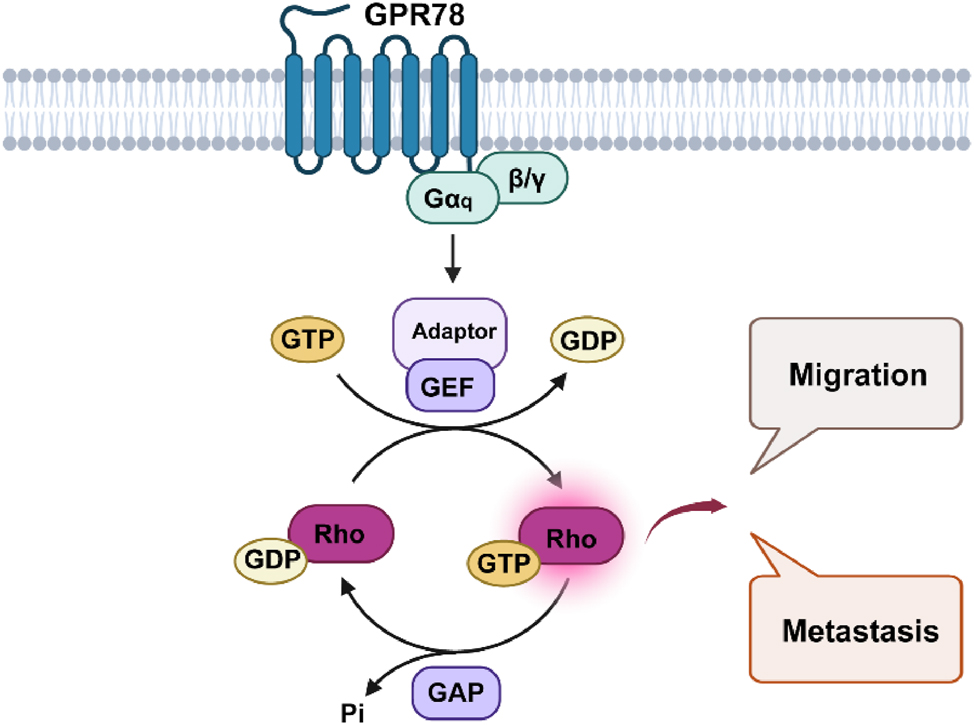

Recently, it has been reported that GPR78 is highly expressed in lung cancer cells. Knockdown of GPR78 significantly suppressed cell migration and metastasis. In this analysis, GPR78 was found to be highly expressed in lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) tissues obtained from TCGA database. Similarly, it is highly expressed in LUAD cell lines [26]. GPR78 promotes cell migration and metastasis of lung cancer cells in a Gq-Rho GTPase-dependent manner. The results suggest that GPR78 is a potential regulator of lung cancer metastasis and may serve as a potential drug target for lung cancer metastasis (Figure 2). Although these findings reveal an emerging oncogenic role for GPR78 in NSCLC, the pathological roles and mechanisms of GPR78 in NSCLC require further investigation. Notably, the ability to interfere with GPR78 may provide unique opportunities for the prevention and treatment of NSCLC. Studies have shown that the use of miRNA-936 can reduce the expression of GPR78 and regulate the proliferation, invasion and migration of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma [27].

GPR78 promotes the migration and metastasis of lung cancer cells in a Gq-Rho GTPase-dependent manner. GPR78, G Protein-Coupled Receptor 78; NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer. (Created with BioRender.com).

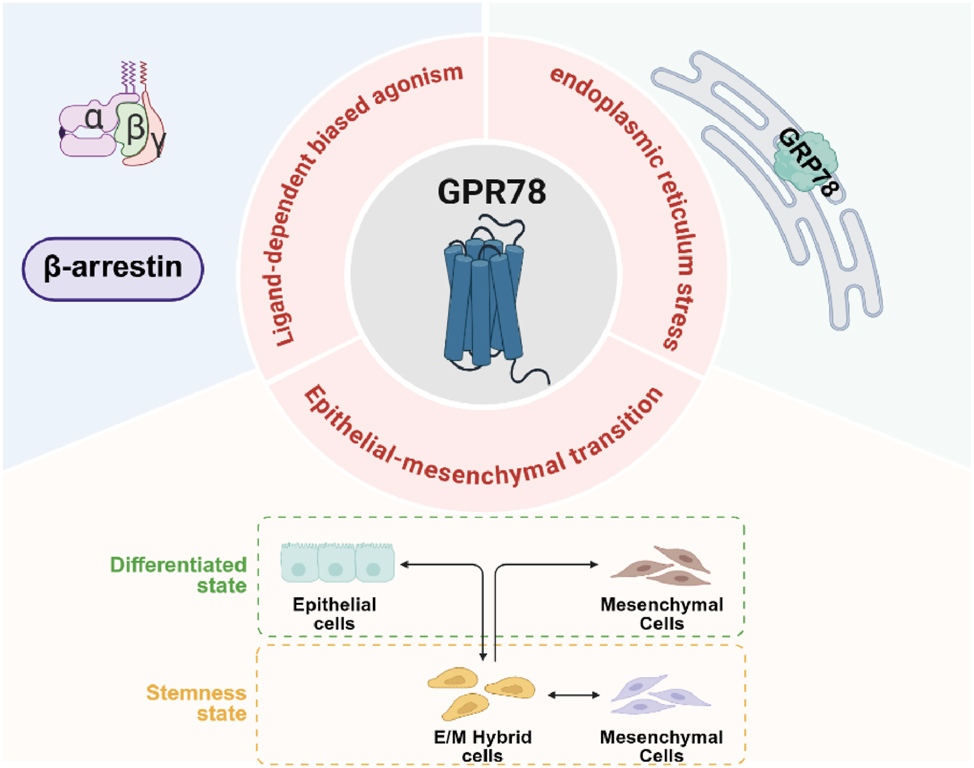

Future screening efforts to identify surrogate or natural ligands are required to delineate the exact signaling pathways in which these receptors participate. Using the AlphaFold prediction model of GPR78, a large-scale virtual screening was conducted on the endogenous metabolite library, peptide library, or known drug library to identify a group of molecules with potential binding capabilities. A recent study that employed a very similar workflow – AlphaFold modeling of GPR78 followed by structure-based virtual screening of the ChemDiv and Enamine REAL libraries – has been published [28]. Then, combined with parallelized high-throughput screening (HTS), activity verification, and pharmacological characterization, an innovative hypothesis regarding the GPR78 signaling pathway network was proposed based on existing evidence and the general laws of tumor biology: (1) GPR78 serves as a key driver node in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT); (2) there may be functional crosstalk between GPR78 on the cell membrane and the key protein GRP78 of endoplasmic reticulum stress; (3) GPR78 may exhibit ligand-dependent biased agonism (Figure 3). These analyses and hypotheses aim to provide new directions and theoretical foundations for future research, with the expectation of accelerating the translational process of GPR78 as a therapeutic target for lung cancer.

Analysis and hypotheses on the transformation of GPR78 as a target for lung cancer Treatment. GPR78, by binding to specific ligands, can regulate the transcription factors related to EMT, causing epithelial cells to lose polarity and intercellular connections, thereby transforming into mesenchymal cells. The interaction between GPR78 and GRP78 within the endoplasmic reticulum is crucial for the survival and migration capabilities of cells in stressful environments. At present, there are no experimental evidence of ligand-dependent biased agonism, but based on the general mechanism of GPCR biased agonism, it is entirely possible to achieve Gs-biased or β-arrestin-biased effects on GPR78. GPR78, G Protein-Coupled Receptor 78; EMT, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor. (Created with BioRender.com).

PAR2 drives proliferation, migration and inhibits apoptosis

PAR2 is a member of the PAR family, which belongs to the class A family and includes four members: PAR1, PAR2, PAR3, and PAR4. PAR2 is also known as coagulation factor II (thrombin) receptor-like 1 (F2RL1) or G protein-coupled receptor 11 (GPR11). PAR2 can be activated after cleavage of the N-terminus by many serine proteases, such as trypsin, tryptase, coagulation factor Xa, tissue factor (TF)-factor VIIa (FVIIa) complex, and testisin [29]. However, it is insensitive to thrombin, unlike PAR1, PAR3, and PAR4. To date, activated PAR2 has been shown to modulate several downstream signaling pathways. PAR2 transduces signals primarily through G proteins, including Gαq, Gαi, and Gα12/13, but not directly through Gαs, which further induces various signaling cascades through different downstream effectors, such as calcium ions, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), c-Jun N-terminuskinases (JNK), and RhoA [30], [31], [32]. Additionally, PAR2 couples with β-arrestins to orchestrate activation of distinct effectors, including Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK)1/2 and PI3K pathways [33]. Furthermore, PAR2 can modulate transactivation of certain cell surface receptors, such as tyrosine kinase receptors [34], 35].

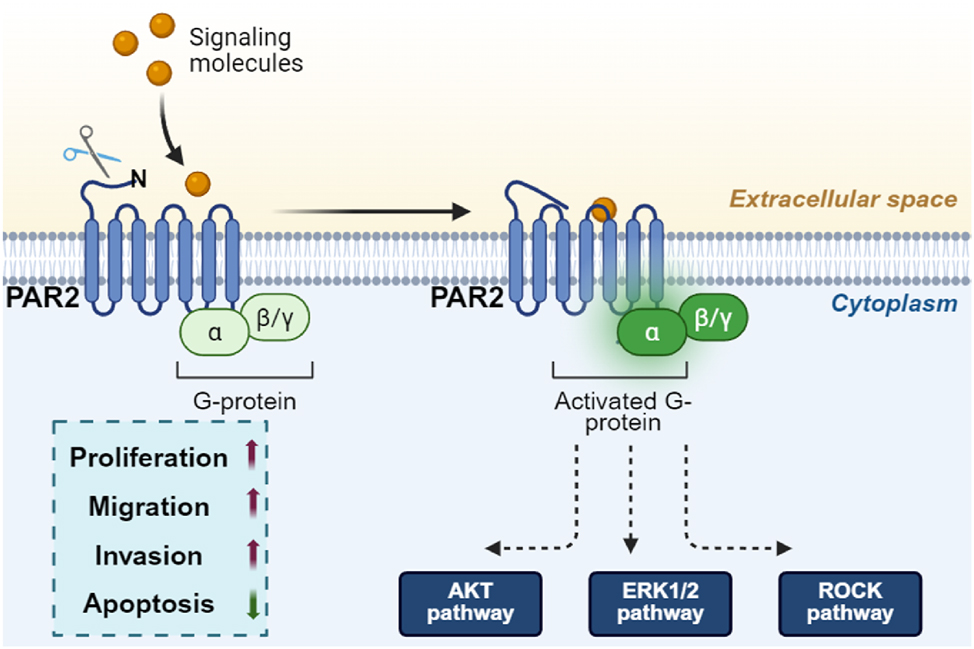

The contribution of PAR2 to tumorigenesis has gained interest over the past few years. PAR2 expression is significantly enhanced during NSCLC progression, and there is a strong correlation between PAR2 expression and the survival of patients with NSCLC [36]. Mounting evidence shows that PAR2 exerts oncogenic potential in NSCLC, although its roles and signaling mechanisms in NSCLC are not fully understood [37]. PAR2 has been reported to the promote proliferation of lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells via an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-dependent signaling pathway and to induce the migration of these cells by inhibiting the expression of microRNA-125b [38], 39]. Kallikrein-related peptidase 6 (KLK6) promotes proliferation and restrains apoptosis in NSCLC cells through PAR2 [38]. In addition, Ma et al. [40] found that Bcl2-like protein-12 mediates the effects of PAR2 on suppressing the expression of p53 in lung cancer cells. PAR2-induced migration is mediated by β-arrestin 1-dependent activation of the Src/p38 MAPK signaling pathway, whereas PAR2-induced EMT is regulated by ERK2-mediated Slug stabilization [41]. In the majority of studies to date, PAR2 plays a central role in epithelial tumor advancement and is a potent inducer of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin stabilization pathway, a core process in both developmental and tumor progression pathways [42]. PAR-mediated MCP-1 expression also depends on PAR2 activation [43]. Taken together, PAR2 contributes to the proliferation and migration of NSCLC cells and inhibits their apoptosis. Furthermore, PAR2 methylation is associated with malignant progression in NSCLC, affecting cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [44]. Therefore, PAR2 has emerged as a promising therapeutic target for inhibiting rapidly metastasizing lung cancer cells (Figure 4).

PAR2 promotes the proliferation and migration of NSCLC cells by activating the G protein-β-arrestin signaling pathway, which further induces EGFR transactivation and activates the MEK/ERK, PI3K/AKT and ROCK pathways. PAR2, Protease-activated receptor 2; NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; PI3K, Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase; AKT, Protein Kinase B. (Created with BioRender.com).

However, the elusive molecular mechanism of its activation and signaling has made it a difficult target for drug development. Understanding PAR2 signaling has been challenging compared to other GPCRs because of its unique mechanism of activation. Many researchers have identified unique ligands that bind to PAR2 and induce biased signaling. For example, DF253 (2f-LAAAAI-NH2) triggered PAR2-mediated calcium release but not ERK1/2 phosphorylation. AY77 (Isox-Cha-Chg-NH2) is a more potent calcium-biased agonist, whereas its analog AY254 (Isox-Cha-Chg-A-R-NH2) is an ERK-biased agonist [45]. FSLLRY-NH2, a PAR2 inhibitor, reduced apoptosis resistance in A549 and H1299 cells [37]. Data on putatively biased agonists and antagonists would be useful for probing their physiological roles and designing novel therapeutic applications. IK187 exhibits PAR2-dependent G protein activation and β-arrestin2 recruitment [46]. However, DF253, AY77 and AY254 showed a preference for Gαq/11 activation rather than for β-arrestin2 recruitment (Figure 5) [47]. Therefore, PAR2-tailored drug discovery is a significant challenge. While designing specific PAR2 inhibitors, we should also consider means to reduce adverse effects. Clinical trials are still limited and have been directed toward patients with diseases other than cancer.

The mechanism of action of PAR2-related ligands. Gαq/11 - calcium pathway bias: DF253, AY77; ERK pathway bias: AY254; Balanced activation: IK187; pathway inhibition: FSLLRY-NH2. PAR2, protease-activated receptor 2; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase. (Created with BioRender.com).

CXCR4 triggers invasion, metastasis and promotes therapeutic resistance

CXCR4 is a 352-amino acid rhodopsin-like GPCR known as an alpha-chemokine receptor specific for stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1; also called CXCL12). Indeed, the biological characteristics of CXCR4 have been extensively studied. CXCR4 is overexpressed in 23 types of cancer and has been studied in clinical trials of hematological malignancies and solid tumors, such as lung cancer [48], [49], [50]. The CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway plays a crucial role in the migration and transport of different cell populations and in the progression and metastasis of various tumors [51], 52].

Recently, a number of studies have shown that CXCR4 is overexpressed in NSCLC and may account for the progression, metastasis, and prognosis of NSCLC [52], 53]. In a meta-analysis [54] of 736 NSCLC patients from eight studies, CXCR4 expression was significantly higher in NSCLC than in normal lung tissue. Another meta-study of 1872 NSCLC patients reported that CXCR4 protein expression is associated with clinical stage, metastasis status, increased risk, and decreased overall survival in patients [55]. CXCR4 regulates the migration of alveolar epithelial cells by activating Rac1, MMP-2, and MMP-14 [56]. CXCR4 overexpression enhances the motility and invasion of NSCLC cells by upregulating ERK, EGFR/HER2-neu, MMP-9, and NF-κB-dependent pathways [57], 58]. Conversely, decreasing the expression of CXCR4 by genetic knockdown of CXCR4 or neutralizing antibodies significantly inhibits the invasion of NSCLC cells [59]. As the EGFR-L858R mutant has been reported to promote the expression of CXCR4 and increased NSCLC cell invasion, targeting CXCR4 significantly inhibited EGFR-L858R-dependent invasion of NSCLC cell [60]. Moreover, CXCR4 promotes EMT processes as evidenced by involvement in CD133-induced as well as miR-1246-induced EMT processes in NSCLC [61].

The CXCR4/CXCL12 axis is closely related to cancer metastasis, which involves adhesion, invasion, cell proliferation, and survival. It has been discovered that CXCL12/CXCR4 axis plays a critical role in determining the metastatic destination of NSCLC cells [23], 62]. CXCR4 promotes cancer metastasis to organs where CXCL12 is generated in large quantities. The interaction between CXCL12 and CXCR4 causes cancer cells to escape from the circulation and enter organs that contain large amounts of chemokines, thus forming metastatic tumors [63]. CXCR4 expression levels were significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis in NSCLC. CXCR4 and VEGF-C synergistically promote lymphatic metastasis in NSCLC patients [64]. CXCR4 mRNA, negatively regulated by breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 (BRMS1), was significantly higher in the NSCLC group with distant metastasis than in that without distant metastasis [65]. In addition, Li H et al. chose to block the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis with AMD3100 (a small-molecule competitive antagonist of CXCL12), and the process of lung cancer metastasis to the brain was significantly slowed down [66], providing a potential drug candidate for inhibiting lung cancer metastasis to the brain.

Researchers have reported that the development of intrinsic or acquired drug resistance is a major challenge associated with chemotherapeutic resistance in cancer cells [67]. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy is frequently used to treat NSCLC; however, the exact mechanism of cisplatin resistance in lung cancer remains unknown. Previous studies have revealed a link between CXCR4 overexpression and chemoresistance in cancer. Cisplatin treatment increases the secretion of CXCL12 and recruitment of metastasis-initiating cells and pro-invasive CXCR4+ macrophages, thereby promoting spontaneous metastasis. Combined treatment with cisplatin and CXCR4 antagonists can prevent this metastasis and emphasizes the approach of CXCR4-targeted therapy for NSCLC [68]. Li J et al. also showed that elevated CXCR4 expression in lung cancer cell lines A549 and 95D promoted cell proliferation and drug resistance to cisplatin [69]. A population of CD133+/CXCR4+ cells still survived in vivo, although lung cancer xenografts established from primary tumors with cisplatin were undertreated, indicating the role of CXCR4 in the anti-chemotherapy of lung cancer [70]. Mechanistically, Nakamura et al. observed that CXCR4 overexpression promoted drug resistance by upregulating transforming growth factor-β2 [71]. Xie et al. [72]observed that CXCR4 mediated cisplatin resistance via regulating CYP1B1 expression. Additionally, it has been shown that CXCR4 is correlated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) resistance. Despite the initial high response rate of EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations, acquired resistance inevitably occurs in patients undergoing EGFR-TKI therapy. CXCR4 overexpression in NSCLC promotes gefitinib resistance associated with EMT [73], 74]. Zhu et al. [75] showed that gefitinib induces an enhanced invasive phenotype through CXCR4, which is dependent on TGF-β1/Smad2 signaling. Furthermore, blocking CXCR4 was shown to reverse the EMT process and reduce invasiveness following gefitinib stimulation. These data suggest that the combination of EGFR-TKIs, CXCR4 antagonists, and TGFβR inhibitors may provide a novel strategy to prevent the progression of lung cancer bearing EGFR-activating mutations. Further investigation is required to address the underlying mechanisms and evaluate the clinical efficacy of this combinatorial approach.

In further support of its oncogenic role, CXCR4 has been reported to mediate the pro-tumorigenic effects of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) through pro-inflammatory molecules such as NF-κB and HIF-1α, which represent key components of the tumor microenvironment and play a key role in cellular carcinogenesis, invasion, and metastasis of NSCLC [76]. The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis also plays an important role in the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in NSCLC [77]. Collectively, these findings highlight the pro-tumorigenic function of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in NSCLC, which acts locally to promote tumor growth, enhance cell motility and invasion, facilitate metastasis, induce chemoresistance, and establish an immune-permissive tumor microenvironment.

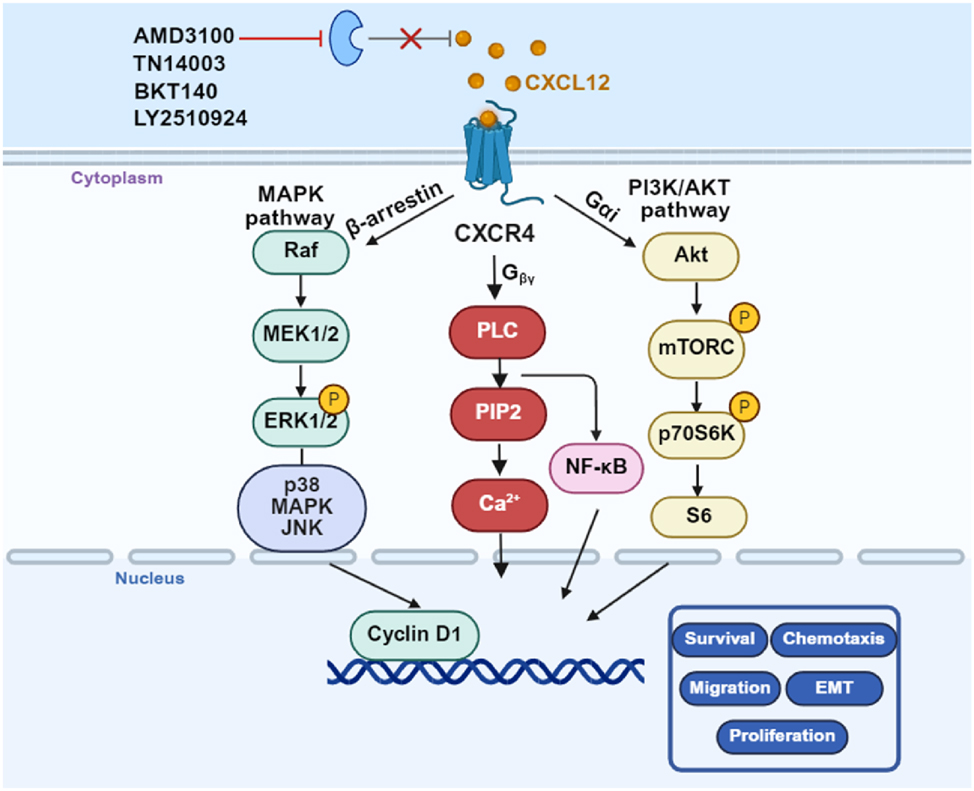

The accumulating knowledge regarding the fundamental roles that CXCL12/CXCR4 plays in solid malignancies has driven multiple pharmaceutical companies to develop specific CXCR4 antagonists. Several promising anti-cancer drugs targeting CXCR4 are currently under evaluation in preclinical and clinical studies. AMD3100 is the most potent non-peptide, small-molecule CXCR4 antagonist. It inhibits the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis by binding to the negatively charged region within the second extracellular loop of CXCR4, thereby blocking downstream signal transduction. This inhibition results in elevated levels of tight junction proteins, reduced blood-brain barrier (BBB) damage, and decreased BBB permeability [66]. In the fifth week, although three mice in the AMD3100-treated group developed brain metastases, the size and number of metastatic foci were significantly smaller than those in the control group. The process of lung cancer metastasis to the brain was substantially slowed [66]. Another small-peptide CXCR4 antagonists, TN14003, is utilized as an adjuvant in traditional anticancer therapies against NSCLC by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation [78], 79], although it is currently not undergoing further clinical development. BKT140 (BL-8040), a small CXCR-4 inhibitor more potent than AMD3100, was shown to increase the effects of standard chemotherapy and radiotherapy in NSCLC cells [80]. LY2510924 is a small cyclic peptide antagonist of CXCR4 that shows antitumor effects in NSCLC [81]. Based on these findings, phase I and II trials using LY2510924 are currently ongoing in patients with advanced tumors. Thus, these findings provide useful information for further study of these effects and a guide for further research on the role of CXCR4 and its prognostic significance in NSCLC (Figure 6).

CXCR4 triggers invasion, metastasis and promotes chemoresistance in NSCLC. CXCR4 drives tumor cell invasion and metastatic spread by activating the CXCL12-CXCR4 axis and downstream MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling. High CXCR4 have been shown to confer resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy. Targeting CXCR4 (AMD3100, TN14003, BKT140 and LY2510924) can simultaneously suppress invasion, chemoresistance, and metastasis making it a promising therapeutic target in NSCLC. CXCR4, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4; NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer; MAPK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3K, Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase; AKT, Protein Kinase B (Created with BioRender.com)

GPBAR regulates the malignant phenotype of NSCLC

GPBAR, also known as TGR5 or GPR131, was first discovered in 2002 as a membrane receptor activated by bile acids [82]. GPBAR can interact with endogenous bile acids such as cholic acid (CA), chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), deoxycholic acid (DCA), and lithocholic acid (LCA), as well as various ligands including synthetically derived bile acid analogs such as INT-777, and small-molecule compounds R399 and P395. These ligands recognize and bind to GPBAR, thereby activating multiple signaling pathways and inducing the transcription and expression of downstream target genes. They participate in regulating various physiological and pathological processes, including energy metabolism, inflammatory responses, cell proliferation, and apoptosis [83], [84], [85], [86], [87].

GPBAR is widely expressed in various tissues, including the lungs. However, at present, there is limited research on GPBAR in lung-related diseases, and studies investigating its role in NSCLC remain scarce. Existing studies have reported that in NSCLC cells, GPBAR promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by activating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway; Further analysis has indicated that GPBAR influences NSCLC cell proliferation primarily by modulating cell cycle progression, whereas its effects on migration and invasion involve the regulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and the RhoA/Rho kinase signaling pathways [88]. The net effect produced by the activation of GPBAR is complex and highly dependent on the specific context. GPBAR would exhibit a biased agonistic effect, that is, depending on the specific ligand, it preferentially activates Gαs or other pathways (for example, β-arrestin). This flexibility of the signal, known as biased agonism, is increasingly regarded as a key factor for its possible dual role in cancer. For instance, the activation of LCA on GPBAR in breast cancer cells induces cell-inhibitory oxidative stress [89], while the activation of SBA on GPBAR in colon cancer cells promotes the recruitment of regulatory T cells through the β-catenin/CCL28 signaling pathway, thereby facilitating immune escape [90]. The Gαs-preferring GPBAR activation induced by INT-777 or DCA inhibited YAP activity and suppressed proliferation. In contrast, the β-arrestin 1-preferring agonist R399 activated YAP and promoted the growth of NSCLC, indicating that a Gs-biased GPBAR agonist has a therapeutic window. That is to say, two specific GPBAR agonists, R399 and INT 777, regulate YAP activity via the Gs/β-arrestin pathway, which may affect the malignant phenotype of NSCLC cells [91]. Moreover, studies have shown that GPBAR promotes the differentiation of TAMs into M2 type by activating the cAMP-STAT3/STAT6 signaling pathway, thereby promoting tumor growth in NSCLC. It was also observed that CDCA-induced phenotypic changes in macrophages are dependent on GPBAR, resulting in attenuated M1 polarization, enhanced M2 polarization, and upregulated expression of anti-inflammatory genes in response to conditioned medium collected from Lewis lung carcinoma cell [92]. Yi-Fei-San-Jie Formula (YFSJF), a patented drug from Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine’s First Affiliated Hospital, has been widely used in clinical practice in China for several years. The unique role of YFSJF in inhibiting immune escape lies in blocking the STAT3/PD-L1 pathway mediated by GPBAR, weakening the binding of PD-L1 and PD-1, and restoring the immune activity of T cells to inhibit immune escape, thereby combating immune escape in lung cancer and exerting anti-tumor effects [93]. In conclusion, GPBAR interacts with various bile acids and plays a significant role in the progression of multiple tumor types [85]. In the “biased agonism” of the GPBAR, how can different receptor conformations be preferentially stabilized to selectively activate specific downstream signaling pathways (such as the Gαs-cAMP and β-arrestin pathways, which leads to the multi-effect and sometimes contradictory results of cellular outcomes; for example, the activation of GPBAR may be anti-proliferative or pro-tumorigenic, depending on the specific ligand and the involved pathways). This complexity not only makes therapeutic regulation difficult, but also provides a complex opportunity for drug design: developing new, biased GPBAR ligands that can selectively promote beneficial anti-inflammatory signaling while avoiding the activation of pro-tumorigenic pathways.

Tumor-suppressive GPCRs in NSCLC

In contrast to the oncogenic GPCRs in NSCLC described above, emerging evidence indicates that certain GPCRs exhibit tumor-suppressive functions.

GPRC5A exhibits tumor suppressive role

GPRC5A, located on chromosome 12p13.1, belongs to the family of orphan GPCRs. GPRC5A is predominantly expressed in the lungs and exhibits weak or negligible expression in other tissues, suggesting a potential role in maintaining lung tissue homeostasis [94], [95], [96]. Some studies have indicated that GPRC5A may function as an oncogene in breast, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers, whereas it has been identified as a tumor suppressor in NSCLC. Notably, p53-null human NSCLC H1299 cells showed increased GPRC5A expression, while p53 wild-type A549 cells showed decreased expression of GPRC5A, suggesting its involvement in the antitumor activity of p53 in NSCLC cells [97]. These findings suggest that GPRC5A may exert context-dependent roles across different cancer types, highlighting its biological complexity and making it a compelling candidate for further investigation.

Previous studies have provided valuable insights into the role of GPRC5A in the development of NSCLC. Both mRNA and protein expression levels of GPRC5A are significantly reduced in lung cancer tissues compared to those in healthy lung tissues [98]. Reduced GPRC5A expression has been linked to poorly differentiated NSCLC cells [99]. Consistently, downregulation of GPRC5A in NSCLC is closely correlated with poor tumor differentiation and advanced TNM stage [100]. Furthermore, studies have shown that the low expression of GPRC5A is related to the early pathological stage of NSCLC, and it has been observed that the low expression of GPRC5A is related to the increased infiltration of immune cells, elevated IPS, and spatial distribution of PD-L1-positive tumor cells [101]. Studies using mouse models have demonstrated that homozygous GPRC5A knockout mice are more susceptible to developing lung tumors at 1–2 years of age compared to heterozygous or wild-type mice. Simultaneously, nicotine-derived nitrosamine ketone (NNK) enhances lung tumorigenesis in GPRC5A−/− mice [102], suggesting that GPRC5A functions as a lung-specific tumor suppressor. Mechanistically, recent advances have shown that GPRC5A is involved in various tumor-associated signaling pathways, including cAMP, NF-κB, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3, and focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/Src signaling. Biologically, knockout of GPRC5A promotes lung inflammation and tumorigenesis through activation of NF-κB, and enhances the malignant transformation of normal lung epithelial cells via activation of STAT3 and downstream signals [103], 104]. A recent study revealed the potential role of GPRC5A in inhibiting EGFR expression and activation through direct translational suppression in combination with the eIF4F complex [98], 105]. Deletion of GPRC5A significantly enhanced the expression of ionizing radiation (IR)-stimulated EGFR, increasing IR-induced lung tumor incidence. In addition, GPRC5A deficiency contributes to dysregulated MDM2 via activated EGFR signaling, which promotes lung tumor development [106]. In summary, GPRC5A deficiency may lead to dysregulation of oncogenic pathways that are crucial for lung tumorigenesis.

GPRC5A contains multiple phosphorylation sites that have been implicated in various biological processes. The biological functions of GPRC5A seem to be differentially regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation. Although GPRC5A does not affect cell proliferation and migration regardless of tyrosine phosphorylation status [107], tyrosine phosphorylation decreases or abolishes GPRC5A-mediated inhibition of EGF-enhanced anchoring-independent growth of NSCLC cells [108]. EGFR-mediated phosphorylation of GPRC5A at TYR-317/TYR-320 and TYR-347/TYR-350, two conserved double-tyrosine (TYR) motifs, leads to weakened tumor-suppressive activities of GPRC5A [108], 109]. Thus, targeting EGFR can restore the tumor-suppressive function of GPRC5A in lung cancer. As previously discussed, GPRC5A is dysregulated in NSCLC and plays a critical role in suppressing tumorigenesis, suggesting its potential as both a diagnostic biomarker and a therapeutic target. Notably, GPRC5A holds significant promise in guiding the optimization of clinical medication strategies. EGFR inhibitors have been shown to be more effective in GPRC5A knockout lung cancer cells compared to GPRC5A wildtype lung cancer cells [98]. Some studies have demonstrated that chromosome deletion at 12p12.3 is rare in NSCLC and that epigenetic alterations may contribute to GPRC5A downregulation [110]. As a complex signaling node, GPRC5A’s regulatory network may extend beyond the EGFR/STAT3 and NF-κB pathways. The way GPRC5A inhibits EGFR may not be simply through direct binding. GPRC5A may play the role of a “signal scaffold protein” on the cell membrane. Its intracellular domain may recruit protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs, such as PTPN1/2) to specifically dephosphorylate the specific sites of EGFR, thereby “blocking” the activation of the EGFR signaling pathway at multiple levels. Furthermore, the absence of GPRC5A leads to the continuous activation of the EGFR/STAT3 and NF-κB pathways, which drives significant metabolic reprogramming.

Despite biochemical evidence supporting its critical role in NSCLC, further studies are required to elucidate the specific mechanisms through which GPRC5A contributes to NSCLC development and metastasis. Although previous investigations have sought to identify a potential ligand for GPRC5A [103], 111], these efforts have not yet been successful; therefore, additional research is necessary to characterize its possible ligands. Moreover, further analyses are warranted to confirm the potential utility of GPRC5A as an independent prognostic marker for NSCLC. Therefore, the successful “orphanicization” of GPRC5A is not only expected to offer new treatment options for lung cancer patients, but also to provide a model for understanding the complex role of GPCRs in cancer.

Somatostatin receptor type 2 behaves as a tumor suppressor

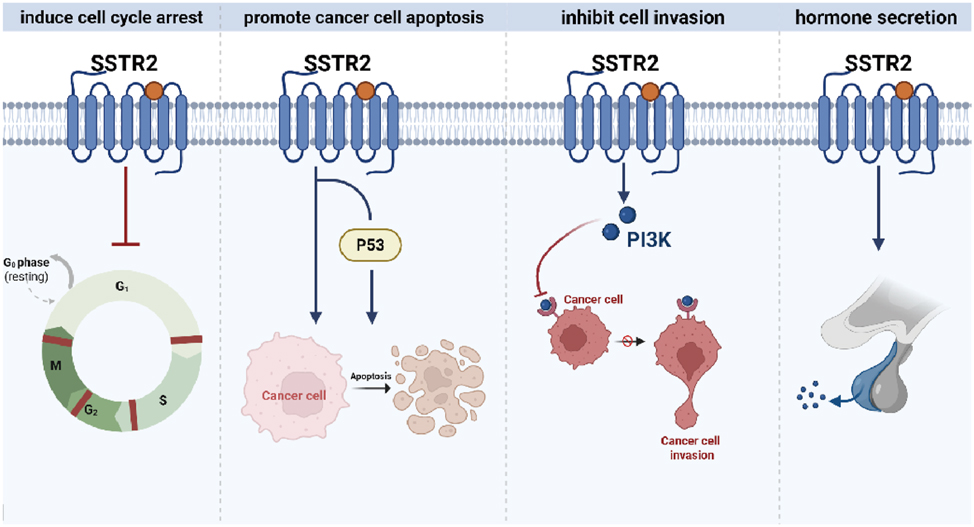

The somatostatin receptor family comprises five distinct members, each encoded by a separate gene located on a different chromosome. Somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) are highly expressed in a variety of tumors [98], 99]. The endogenous high-affinity ligand for SSTRs is somatostatin, a polypeptide naturally present in the CNS as well as various peripheral tissues and organs. Somatostatin is an inherently pleiotropic inhibitory neuropeptide with anti-secretory, anti-proliferative, and anti-angiogenic properties [100]. However, its clinical application is limited due to an extremely short half-life of approximately 2–3 min, which has led to the development of numerous synthetic somatostatin analogs (SSAs). Somatostatin and its analogs or agonists inhibit tumor growth and metastatic progression by activating SSTRs in both cancer cells and components of the tumor microenvironment. Among the five receptor subtypes, SSTR2 is the most frequently overexpressed subtype in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) [112]. However, accumulating evidence indicates that SSTR2 functions as a tumor suppressor in NSCLC. Upon activation, SSTR2 induces cell cycle arrest [113], promotes cancer cell apoptosis via a p53-dependent or p53-independent mechanism [114], suppresses cell invasion by modulating the PI3K pathway, and restores gap junction communication, which plays a critical role in contact inhibition and the maintenance of cellular differentiation (Figure 7).

The mechanism of SSTR2 in NSCLC. Activation of SSTR2 induces cell cycle arrest, promotes cancer cell apoptosis through p53-dependent or -independent mechanisms, inhibits cell invasion by modulating the PI3K pathway, and restores gap junctional communication. SSTR2, Somatostatin receptor type 2; NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer; PI3K, Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase. (Created with BioRender.com).

Furthermore, SSTR2 is also associated with other molecules and pathways. The co-expression of SSTR2A and EGFR suggests the existence of a potential synergistic signaling pathway [115], which is worthy of further exploration for the potential of combined targeting; the expression of SSTR2 is positively correlated with neuroendocrine genes such as NEUROD1 and ASCL1, suggesting that some NSCLC may have a neuroendocrine phenotype [116]. Although mainly reported in SCLC, the downregulation of SSTR2 can lead to a decrease in AMPKα phosphorylation and an increase in oxidative metabolism. This mechanism has yet to be verified in NSCLC [112].

Currently, various strategies such as gene transfection [117], radioactive ligands, and traditional somatostatin analogs have been validated for their inhibitory effects in experimental models, providing a theoretical basis for future clinical translation. Shen and colleagues evaluated the antitumor effects of a conjugate formed by linking two molecules of paclitaxel to octreotide (SMS 201–995, Sandostatin), an octapeptide analog of endogenous somatostatin with high affinity for SSTR2, in a xenograft model using A549 human NSCLC cells implanted in nude mice [118]. The conjugate significantly inhibited tumor growth and increased necrosis. These findings suggest that the paclitaxel-octreotide conjugate may serve as a potential targeted therapeutic agent for NSCLC. Similarly, Sun et al. developed paclitaxel-octreotide conjugates that exhibited dose- and time-dependent inhibition of A549 and Calu-6 NSCLC cell proliferation. Paclitaxel and its conjugated derivatives were also shown to increase the G2/M phase population in A549 cells [119]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that targeting SSTR2 effectively inhibits lung tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo. These findings suggest that SSTR2 and associated signaling pathways may represent promising biomarkers for personalized therapeutic strategies in NSCLC.

Conclusions and perspectives

The escalating global burden of cancer necessitates more effective biomarkers and novel therapeutic approaches. As the largest family of cell surface receptors, GPCRs regulate diverse signaling pathways and show promise as diagnostic, predictive, and prognostic biomarkers in NSCLC (Table 3). Comprehensive reviews of GPCR-related biomarkers in NSCLC emphasize their role in tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis, and propose them as diagnostic and prognostic markers (e.g., CXCR2, CXCR4 and PAR2). Further, GPCRs – exemplified by GPRC5A and SSTR2 – represent a promising frontier for improving NSCLC diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment. Continued interdisciplinary research will be pivotal to harness their full clinical potential. While our understanding of GPCR involvement in NSCLC pathogenesis is advancing, few GPCR-targeted agents have been translated to clinical use for this malignancy (Table 4). Only a handful of GPCR-targeted agents have entered clinical testing for NSCLC, and most of them are still early-phase or exploratory studies. For each drug–receptor pair the GPCRdb database computes an Association Score (0–1) that reflects the strength of experimental, pharmacological and clinical evidence linking the ligand to the receptor and to a disease indication. A high score (>0.5) typically requires multiple independent activity data points, structural validation, and/or successful clinical outcomes. Although the CXCR4 inhibitors have strong preclinical data supporting their effectiveness in inhibiting the migration of non-small cell lung cancer cells and mobilizing stem cells, clinical trials have not yet demonstrated their clear therapeutic efficacy. Therefore, these drugs have an association score of less than 0.2 in GPCRdb. The orphan receptor GPR87 is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer due to its overexpression. However, there are currently no selective clinical candidate drugs for it, so the database has given it an extremely low score (<0.05). The GPCRdb currently reflects modest association scores for GPCR-targeted agents in NSCLC, mirroring the early-stage translational status of these drugs. Strengthening clinical evidence, improving selectivity, and leveraging new structural models are the most direct routes to elevate these scores and move GPCR therapeutics from bench to bedside.

The recent clinical investigations of several targeted agents in NSCLC provide a nuanced picture of efficacy and safety. A study investigating iloprost’s efficacy in preventing cancer in high-risk lung cancer patients reported rare serious adverse reactions compared to a placebo group (4.00 % vs. 7.79 %), indicating a lower toxicity profile for iloprost while still achieving histologic improvement in bronchial dysplasia. In a phase II trial of ZD4054 (Zibotatin) for non-small cell lung cancer, combination therapy with ZD4054 reduced severe adverse reactions of pemetrexed (11.11 % vs. 23.33 %), suggesting that ZD4054 may mitigate chemotherapy-induced toxicity. The clinical efficacy of mogamulizumab combined with docetaxel in non-small cell lung cancer primarily resulted in serious adverse reactions related to the blood and lymphatic systems. These adverse reactions were the primary safety concern of the regimen, reflecting the expected myelosuppressive effects of both agents. An evaluation of anamorelin chloride for weight loss and anorexia in advanced NSCLC patients found no significant difference in severe adverse reactions compared to a placebo, with main issues involving respiratory system, chest, and mediastinal diseases, consistent with the underlying disease burden rather than drug toxicity (Table 5). These findings collectively support continued development of targeted and supportive therapies that not only enhance antitumor activity but also prioritize patient safety and quality of life. Consequently, elucidating the physiological functions of both characterized and uncharacterized GPCRs may reveal novel therapeutic opportunities for NSCLC. Notably, the GPCRs discussed herein represent a non-exhaustive selection. Receptors such as CXCR1, CXCR2, A2a, OR2J3, and MRGPRD may offer unique avenues for NSCLC prevention and treatment. However, research on many GPCRs remains nascent, and comprehensive characterization of their pathological roles in NSCLC is imperative. Key challenges – including target validation, mechanistic studies, and therapeutic optimization – must be addressed to advance this field.

New targets validation: Through large-scale, multicenter studies with well-matched cohorts, integrated multi-omics analysis combined with functional experiments, new target GPCRs closely related to the occurrence, development, and treatment response of NSCLC need to be further identified. By using double-gene CRISPR screening and network centrality analysis within the redundant GPCR family, the key “hub” GPCR was identified. Utilizing spatial omics technology to confirm the uniformity of GPCR expression (taking into account the heterogeneity within tumors, and screening suitable patient subgroups.)

Ligand discovery and mechanistic analysis: Despite the proven success of GPCRs as drug targets, clinically useful ligands remain unavailable for most receptors, particularly orphan GPCRs (e.g., GPR78 and GPRC5A). Deorphanization efforts to identify natural ligands and define their roles and underlying mechanisms in NSCLC pathophysiology are therefore essential. By using structure prediction (AlphaFold-multimer) combined with virtual screening, new ligands or biased agonists for orphan receptors were discovered. Given the complexity and diversity of downstream signaling pathways activated by GPCRs, future research should prioritize the development of agents, such as biased agonists or antagonists, that selectively modulate pathogenic signaling pathways, with the aim of maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. For example, GPR78 mainly promotes migration through Gαq-RhoA/Rac1. Designing Gαq-biased antagonists is the main direction of effort. Candidate compounds can be rapidly discovered through artificial intelligence-molecular docking + HTS. GPRC5A seems to play a role in inhibiting oncogenic pathways such as NF-κB/STAT3. The Gαs-biased agonist (which increases cAMP) may enhance its anti-cancer function while avoiding the activation of the possible oncogenic β-arrestin pathway.

Elucidation of the structural-functional relationships in GPCRs: The structural complexity of GPCRs, involving multiple ligand-binding sites, biased signaling potential, and receptor homo-/heterodimerization, presents significant challenges in drug design. These characteristics represent both opportunities in drug discovery and major obstacles in the design of efficient and low-toxic anti-cancer therapies. By integrating the latest high-resolution structures, biophysical dynamics, single-cell omics, and artificial intelligence technologies, breakthroughs can be achieved at the following levels: (i)Develop dimer/iso-dimer-specific drugs to achieve tumor-specific targeting; (ii) Utilize tissue-specific expression information to reduce off-target effects throughout the body; (iii) Construct an AI-assisted drug design platform to accelerate the transformation from structure to clinical application. A comprehensive understanding of the structural basis underlying GPCR signaling and functional dynamics is essential and warrants thorough investigation in future research to facilitate the development of highly effective and low-toxicity anticancer therapeutics.

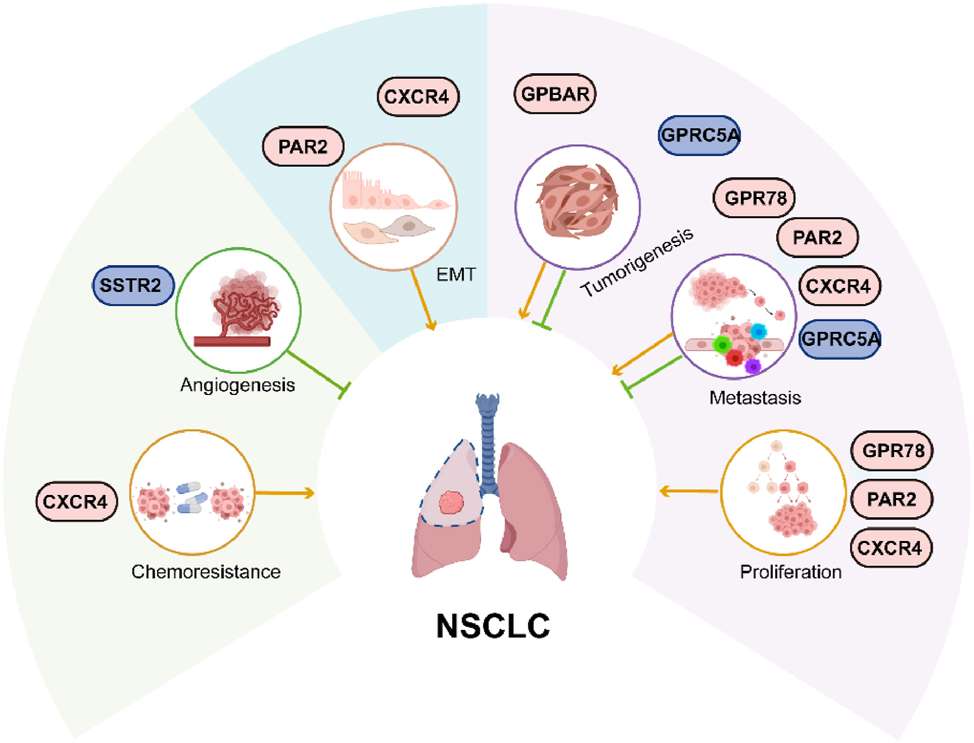

In summary, current literature and clinical evidence indicate that GPCRs play a critical role in NSCLC initiation and progression (Figure 8, oncogenic GPCRs: CXCR4, PAR2, GPBAR, GPR78; tumor-suppressive GPCRs: SSTR2, GPRC5A). GPCR-targeting regulators hold significant promise as a transformative therapeutic strategy for NSCLC. However, further research is necessary to elucidate the detailed molecular mechanisms by which GPCRs influence cancer progression, in order to develop more precise GPCR-targeted therapeutic agents and benefit more patients.

Summary of NSCLC-associated GPCRs. The aberrant expression of GPCRs alters normal physiological signaling pathways, and governs the proliferation, invasion, metastasis, EMT and chemoresistance in NSCLC progression. The light gray icons represent the driver oncogenes; the blue icons represent tumor suppressors. NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptors; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition. (Created with BioRender.com).

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: ZR202211150041

Funding source: Science and Technology Tackling Key Project of Henan Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: NO.242102311014

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Lijuan Ma: investigation, resources writing-original draft. Pengju Zhang: conceptualization and funding acquisition. Jin-peng Sun: conceptualization and supervisor project administration. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The work was supported by grants from Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR202211150041 to P.-J.Z.), and Science and Technology Tackling Key Project of Henan Province (Project No. 242102311014 to L.-J. M).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Bray, F, Laversanne, M, Sung, H, Ferlay, J, Siegel, RL, Soerjomataram, I, et al.. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:229–63. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Siegel, RL, Giaquinto, AN, Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:12–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21820.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Nicholson, AG, Tsao, MS, Beasley, MB, Borczuk, AC, Brambilla, E, Cooper, WA, et al.. The 2021 WHO classification of lung tumors: impact of advances since 2015. J Thorac Oncol 2022;17:362–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2021.11.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Parvaresh, H, Roozitalab, G, Golandam, F, Behzadi, P, Jabbarzadeh Kaboli, P. Unraveling the potential of ALK-targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer: comprehensive insights and future directions. Biomedicines 2024;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12020297.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Su, PL, Furuya, N, Asrar, A, Rolfo, C, Li, Z, Carbone, DP, et al.. Recent advances in therapeutic strategies for non-small cell lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2025;18:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-025-01679-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Arakaki, AKS, Pan, WA, Trejo, J. GPCRs in cancer: protease-activated receptors, endocytic adaptors and signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19071886.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Lee, S, Chung, YH, Lee, C. US28, a virally-encoded GPCR as an antiviral target for human cytomegalovirus infection. Biomol Ther 2017;25:69–79. https://doi.org/10.4062/biomolther.2016.208.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Jin, C, Chen, H, Xie, L, Zhou, Y, Liu, LL, Wu, J, et al.. GPCRs involved in metabolic diseases: pharmacotherapeutic development updates. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2024;45:1321–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-023-01215-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Cho, YY, Kim, S, Kim, P, Jo, MJ, Park, SE, Choi, Y, et al.. G-Protein-Coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling and pharmacology in metabolism: physiology, mechanisms, and therapeutic potential. Biomolecules 2025;15. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15020291.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Downey, ML, Peralta-Yahya, P. Technologies for the discovery of G protein-coupled receptor-targeting biologics. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2024;87:103138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2024.103138.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Lappano, R, Maggiolini, M. G protein-coupled receptors: novel targets for drug discovery in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011;10:47–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3320.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Santos, R, Ursu, O, Gaulton, A, Bento, AP, Donadi, RS, Bologa, CG, et al.. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017;16:19–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2016.230.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Sriram, K, Insel, PA. G protein-coupled receptors as targets for approved drugs: how many targets and how many drugs? Mol Pharmacol 2018;93:251–8. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.117.111062.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Lorente, JS, Sokolov, AV, Ferguson, G, Schiöth, HB, Hauser, AS, Gloriam, DE, et al.. GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2025;24:458–79. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-025-01139-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Hauser, AS, Chavali, S, Masuho, I, Jahn, LJ, Martemyanov, KA, Gloriam, DE, et al.. Pharmacogenomics of GPCR drug targets. Cell 2018;172:41–54.e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.033.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Cvicek, V, Goddard, WA3rd, Abrol, R. Structure-based sequence alignment of the transmembrane domains of all human GPCRs: phylogenetic, structural and functional implications. PLoS Comput Biol 2016;12:e1004805. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004805.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Magalhaes, AC, Dunn, H, Ferguson, SS. Regulation of GPCR activity, trafficking and localization by GPCR-interacting proteins. Br J Pharmacol 2012;165:1717–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01552.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Wong, TS, Li, G, Li, S, Gao, W, Chen, G, Gan, S, et al.. G protein-coupled receptors in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric disorders. Signal Trans Target Ther 2023;8:177. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01427-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Chaudhary, PK, Kim, S. An insight into GPCR and G-Proteins as cancer drivers. Cells 2021;10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10123288.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Saintigny, P, Massarelli, E, Lin, S, Ahn, YH, Chen, Y, Goswami, S, et al.. CXCR2 expression in tumor cells is a poor prognostic factor and promotes invasion and metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2013;73:571–82. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-12-0263.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Keane, MP, Belperio, JA, Xue, YY, Burdick, MD, Strieter, RM. Depletion of CXCR2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in a murine model of lung cancer. J Immunol 2004;172:2853–60. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2853.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Spano, JP, Andre, F, Morat, L, Sabatier, L, Besse, B, Combadiere, C, et al.. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 and early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: pattern of expression and correlation with outcome. Ann Oncol 2004;15:613–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdh136.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Cavallaro, S. CXCR4/CXCL12 in non-small-cell lung cancer metastasis to the brain. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:1713–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14011713.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Lappano, R, Maggiolini, M. Pharmacotherapeutic targeting of G protein-coupled receptors in oncology: examples of approved therapies and emerging concepts. Drugs 2017;77:951–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0738-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Wang, W, Wang, S, Chu, X, Liu, H, Xiang, M. Predicting the lung squamous cell carcinoma diagnosis and prognosis markers by unique DNA methylation and gene expression profiles. J Comput Biol 2019;27:1041–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/cmb.2019.0138.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Dong, DD, Zhou, H, Li, G. GPR78 promotes lung cancer cell migration and metastasis by activation of Gαq-Rho GTPase pathway. BMB Rep 2016;49:623–8. https://doi.org/10.5483/bmbrep.2016.49.11.133.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Lin, XJ, Liu, H, Li, P, Wang, HF, Yang, AK, Di, JM, et al.. miR-936 suppresses cell proliferation, invasion, and drug resistance of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma and targets GPR78. Front Oncol 2020;10:60. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00060.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Garisetti, V, Varughese, RE, Anandamurthy, A, Haribabu, J, Allard Garrote, C, Dasararaju, G, et al.. Virtual screening, molecular docking and dynamics simulation studies to identify potential agonists of orphan receptor GPR78 targeting CNS disorders. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 2024;44:82–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10799893.2024.2405488.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Yau, MK, Liu, L, Fairlie, DP. Toward drugs for protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). J Med Chem 2013;56:7477–97. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm400638v.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Katritch, V, Cherezov, V, Stevens, RC. Structure-function of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2013;53:531–56. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-032112-135923.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Ghosh, E, Kumari, P, Jaiman, D, Shukla, AK. Methodological advances: the unsung heroes of the GPCR structural revolution. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015;16:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3933.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Kimple, AJ, Bosch, DE, Giguère, PM, Siderovski, DP. Regulators of G-protein signaling and their Gα substrates: promises and challenges in their use as drug discovery targets. Pharmacol Rev 2011;63:728–49. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.110.003038.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Adams, MN, Ramachandran, R, Yau, MK, Suen, JY, Fairlie, DP, Hollenberg, MD, et al.. Structure, function and pathophysiology of protease activated receptors. Pharmacol Ther 2011;130:248–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Hugo de Almeida, V, Guimarães, IDS, Almendra, LR, Rondon, AMR, Tilli, TM, de Melo, AC, et al.. Positive crosstalk between EGFR and the TF-PAR2 pathway mediates resistance to cisplatin and poor survival in cervical cancer. Oncotarget 2018;9:30594–609. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.25748.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Chung, H, Ramachandran, R, Hollenberg, MD, Muruve, DA. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor and transforming growth factor-β receptor signaling pathways contributes to renal fibrosis. J Biol Chem 2013;288:37319–31. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m113.492793.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Jiang, Y, Zhuo, X, Fu, X, Wu, Y, Mao, C. Targeting PAR2 overcomes gefitinib resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer cells through inhibition of EGFR transactivation. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:625289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.625289.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Wang, B, Wu, MD, Lan, YJ, Jia, CY, Zhao, H, Yang, KP, et al.. PAR2 promotes malignancy in lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Transl Res 2024;16:7416–26. https://doi.org/10.62347/stsi5751.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Michel, N, Heuzé-Vourc’h, N, Lavergne, E, Parent, C, Jourdan, ML, Vallet, A, et al.. Growth and survival of lung cancer cells: regulation by kallikrein-related peptidase 6 via activation of proteinase-activated receptor 2 and the epidermal growth factor receptor. Biol Chem 2014;395:1015–25. https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2014-0124.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Huang, SH, Li, Y, Chen, HG, Rong, J, Ye, S. Activation of proteinase-activated receptor 2 prevents apoptosis of lung cancer cells. Cancer Invest 2013;31:578–81. https://doi.org/10.3109/07357907.2013.845674.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Ma, G, Wang, C, Lv, B, Jiang, Y, Wang, L. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 enhances Bcl2-like protein-12 expression in lung cancer cells to suppress p53 expression. Arch Med Sci 2019;15:1147–53. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2019.86980.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Tsai, CC, Chou, YT, Fu, HW. Protease-activated receptor 2 induces migration and promotes Slug-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2019;1866:486–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.10.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Nag, JK, Kancharla, A, Maoz, M, Turm, H, Agranovich, D, Gupta, CL, et al.. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 is a novel coreceptor of protease-activated receptor-2 in the dynamics of cancer-associated β-catenin stabilization. Oncotarget 2017;8:38650–67. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16246.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Li, X, Tai, HH. Thromboxane A2 receptor-mediated release of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) induces expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) by activation of protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) in A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Carcinog 2014;53:659–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.22020.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Wu, K, Xu, L, Cheng, L. PAR2 promoter hypomethylation regulates PAR2 gene expression and promotes lung adenocarcinoma cell progression. Comput Math Methods Med 2021;2021:5542485. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5542485.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Jiang, Y, Yau, MK, Kok, WM, Lim, J, Wu, KC, Liu, L, et al.. Biased signaling by agonists of protease activated receptor 2. ACS Chem Biol 2017;12:1217–26. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.6b01088.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Klösel, I, Schmidt, MF, Kaindl, J, Hübner, H, Weikert, D, Gmeiner, P, et al.. Discovery of novel nonpeptidic PAR2 ligands. ACS Med Chem Lett 2020;11:1316–23. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00154.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Jiang, Y, Yau, MK, Lim, J, Wu, KC, Xu, W, Suen, JY, et al.. A potent antagonist of protease-activated receptor 2 that inhibits multiple signaling functions in human cancer cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2018;364:246–57. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.117.245027.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Nengroo, MA, Khan, MA, Verma, A, Datta, D. Demystifying the CXCR4 conundrum in cancer biology: beyond the surface signaling paradigm. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2022;1877:188790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188790.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Qiu, L, Xu, Y, Xu, H, Yu, B. The clinicopathological and prognostic value of CXCR4 expression in patients with lung cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2022;22:681. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09756-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Yang, Y, Li, J, Lei, W, Wang, H, Ni, Y, Liu, Y, et al.. CXCL12-CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in cancer: from mechanisms to clinical applications. Int J Biol Sci 2023;19:3341–59. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.82317.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Jacquelot, N, Enot, DP, Flament, C, Vimond, N, Blattner, C, Pitt, JM, et al.. Chemokine receptor patterns in lymphocytes mirror metastatic spreading in melanoma. J Clin Investig 2016;126:921–37. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci80071.Suche in Google Scholar

52. Otsuka, S, Klimowicz, AC, Kopciuk, K, Petrillo, SK, Konno, M, Hao, D, et al.. CXCR4 overexpression is associated with poor outcome in females diagnosed with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:1169–78. https://doi.org/10.1097/jto.0b013e3182199a99.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Wald, O. CXCR4 based therapeutics for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Med 2018;7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7100303.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Zhou, XM, He, L, Hou, G, Jiang, B, Wang, YH, Zhao, L, et al.. Clinicopathological significance of CXCR4 in non-small cell lung cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015;9:1349–58. https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.s71060.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Zhang, C, Li, J, Han, Y, Jiang, J. A meta-analysis for CXCR4 as a prognostic marker and potential drug target in non-small cell lung cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015;9:3267–78. https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.s81564.Suche in Google Scholar

56. Ghosh, MC, Makena, PS, Gorantla, V, Sinclair, SE, Waters, CM. CXCR4 regulates migration of lung alveolar epithelial cells through activation of Rac1 and matrix metalloproteinase-2. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2012;302:L846–56. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00321.2011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Huang, YC, Hsiao, YC, Chen, YJ, Wei, YY, Lai, TH, Tang, CH, et al.. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 enhances motility and integrin up-regulation through CXCR4, ERK and NF-kappaB-dependent pathway in human lung cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2007;74:1702–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.025.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Zuo, J, Wen, M, Li, S, Lv, X, Wang, L, Ai, X, et al.. Overexpression of CXCR4 promotes invasion and migration of non-small cell lung cancer via EGFR and MMP-9. Oncol Lett 2017;14:7513–21. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2017.7168.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Su, L, Zhang, J, Xu, H, Wang, Y, Chu, Y, Liu, R, et al.. Differential expression of CXCR4 is associated with the metastatic potential of human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:8273–80. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-05-0537.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Tsai, MF, Chang, TH, Wu, SG, Yang, HY, Hsu, YC, Yang, PC, et al.. EGFR-L858R mutant enhances lung adenocarcinoma cell invasive ability and promotes malignant pleural effusion formation through activation of the CXCL12-CXCR4 pathway. Sci Rep 2015;5:13574. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13574.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61. Tu, Z, Xie, S, Xiong, M, Liu, Y, Yang, X, Tembo, KM, et al.. CXCR4 is involved in CD133-induced EMT in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Oncol 2017;50:505–14. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2016.3812.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Yan, L, Cai, Q, Xu, Y. The ubiquitin-CXCR4 axis plays an important role in acute lung infection-enhanced lung tumor metastasis. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4706–16. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-13-0011.Suche in Google Scholar

63. Müller, A, Homey, B, Soto, H, Ge, N, Catron, D, Buchanan, ME, et al.. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature 2001;410:50–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/35065016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

64. Bi, MM, Shang, B, Wang, Z, Chen, G. Expression of CXCR4 and VEGF-C is correlated with lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer 2017;8:634–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.12500.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

65. Yang, J, Zhang, B, Lin, Y, Yang, Y, Liu, X, Lu, F, et al.. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 inhibits SDF-1alpha-induced migration of non-small cell lung cancer by decreasing CXCR4 expression. Cancer Lett 2008;269:46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Li, H, Chen, Y, Xu, N, Yu, M, Tu, X, Chen, Z, et al.. AMD3100 inhibits brain-specific metastasis in lung cancer via suppressing the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis and protecting blood-brain barrier. Am J Transl Res 2017;9:5259–74.Suche in Google Scholar

67. Holohan, C, Van Schaeybroeck, S, Longley, DB, Johnston, PG. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer 2013;13:714–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3599.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

68. Bertolini, G, Cancila, V, Milione, M, Lo Russo, G, Fortunato, O, Zaffaroni, N, et al.. A novel CXCR4 antagonist counteracts paradoxical generation of cisplatin-induced pro-metastatic niches in lung cancer. Mol Ther 2021;29:2963–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.05.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69. Li, J, Guan, J, Long, X, Wang, Y, Xiang, X. mir-1-mediated paracrine effect of cancer-associated fibroblasts on lung cancer cell proliferation and chemoresistance. Oncol Rep 2016;35:3523–31. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2016.4714.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

70. Bertolini, G, Roz, L, Perego, P, Tortoreto, M, Fontanella, E, Gatti, L, et al.. Highly tumorigenic lung cancer CD133+ cells display stem-like features and are spared by cisplatin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:16281–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0905653106.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71. Nakamura, T, Shinriki, S, Jono, H, Guo, J, Ueda, M, Hayashi, M, et al.. Intrinsic TGF-β2-triggered SDF-1-CXCR4 signaling axis is crucial for drug resistance and a slow-cycling state in bone marrow-disseminated tumor cells. Oncotarget 2015;6:1008–19. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.2826.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

72. Xie, S, Tu, Z, Xiong, J, Kang, G, Zhao, L, Hu, W, et al.. CXCR4 promotes cisplatin-resistance of non-small cell lung cancer in a CYP1B1-dependent manner. Oncol Rep 2017;37:921–8. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2016.5289.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

73. Hu, Y, Zang, J, Qin, X, Yan, D, Cao, H, Zhou, L, et al.. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition correlates with gefitinib resistance in NSCLC cells and the liver X receptor ligand GW3965 reverses gefitinib resistance through inhibition of vimentin. OncoTargets Ther 2017;10:2341–8. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.s124757.Suche in Google Scholar

74. Shahverdi, M, Hajiasgharzadeh, K, Sorkhabi, AD, Jafarlou, M, Shojaee, M, Jalili, TN, et al.. The regulatory role of autophagy-related miRNAs in lung cancer drug resistance. Biomed Pharmacother 2022;148:112735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112735.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

75. Zhu, Q, Zhang, Z, Lu, C, Xu, F, Mao, W, Zhang, K, et al.. Gefitinib promotes CXCR4-dependent epithelial to mesenchymal transition via TGF-β1 signaling pathway in lung cancer cells harboring EGFR mutation. Clin Transl Oncol 2020;22:1355–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-019-02266-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

76. Yusen, W, Xia, W, Shengjun, Y, Shaohui, Z, Hongzhen, Z. The expression and significance of tumor associated macrophages and CXCR4 in non-small cell lung cancer. J BUON 2018;23:398–402.Suche in Google Scholar

77. Rogado, J, Pozo, F, Troule, K, Pacheco, M, Adrados, M, Sánchez-Torres, JM, et al.. The role of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in the immunotherapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 2025;27:2970–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-024-03828-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

78. Jung, MJ, Rho, JK, Kim, YM, Jung, JE, Jin, YB, Ko, YG, et al.. Upregulation of CXCR4 is functionally crucial for maintenance of stemness in drug-resistant non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncogene 2013;32:209–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.37.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

79. Wald, O, Izhar, U, Amir, G, Kirshberg, S, Shlomai, Z, Zamir, G, et al.. Interaction between neoplastic cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts through the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis: role in non-small cell lung cancer tumor proliferation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141:1503–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.11.056.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

80. Fahham, D, Weiss, ID, Abraham, M, Beider, K, Hanna, W, Shlomai, Z, et al.. In vitro and in vivo therapeutic efficacy of CXCR4 antagonist BKT140 against human non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:1167–75.e1161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.07.031.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

81. Galsky, MD, Vogelzang, NJ, Conkling, P, Raddad, E, Polzer, J, Roberson, S, et al.. A phase I trial of LY2510924, a CXCR4 peptide antagonist, in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:3581–8. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-13-2686.Suche in Google Scholar

82. Kawamata, Y, Fujii, R, Hosoya, M, Harada, M, Yoshida, H, Miwa, M, et al.. A G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J Biol Chem 2003;278:9435–40. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m209706200.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

83. Zhao, RY, He, SJ, Ma, JJ, Hu, H, Gong, YP, Wang, YL, et al.. High expression of TGR5 predicts a poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2018;11:3567–74.Suche in Google Scholar

84. Guo, C, Chen, WD, Wang, YD. TGR5, not only a metabolic regulator. Front Physiol 2016;7:646. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00646.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

85. Guo, C, Su, J, Li, Z, Xiao, R, Wen, J, Li, Y, et al.. The G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor Gpbar1 (TGR5) suppresses gastric cancer cell proliferation and migration through antagonizing STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2015;6:34402–13. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5353.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

86. Reich, M, Deutschmann, K, Sommerfeld, A, Klindt, C, Kluge, S, Kubitz, R, et al.. TGR5 is essential for bile acid-dependent cholangiocyte proliferation in vivo and in vitro. Gut 2016;65:487–501. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309458.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

87. Fiorucci, S, Distrutti, E. The pharmacology of bile acids and their receptors. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2019;256:3–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2019_238.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

88. Liu, X, Chen, B, You, W, Xue, S, Qin, H, Jiang, H, et al.. The membrane bile acid receptor TGR5 drives cell growth and migration via activation of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett 2018;412:194–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2017.10.017.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

89. Kovács, P, Csonka, T, Kovács, T, Sári, Z, Ujlaki, G, Sipos, A, et al.. Lithocholic acid, a metabolite of the microbiome, increases oxidative stress in breast cancer. Cancers 2019;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11091255.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

90. Sun, L, Zhang, Y, Cai, J, Rimal, B, Rocha, ER, Coleman, JP, et al.. Bile salt hydrolase in non-enterotoxigenic bacteroides potentiates colorectal cancer. Nat Commun 2023;14:755. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36089-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

91. Ma, L, Yang, F, Wu, X, Mao, C, Guo, L, Miao, T, et al.. Structural basis and molecular mechanism of biased GPBAR signaling in regulating NSCLC cell growth via YAP activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022;119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2117054119.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

92. Zhao, L, Zhang, H, Liu, X, Xue, S, Chen, D, Zou, J, et al.. TGR5 deficiency activates antitumor immunity in non-small cell lung cancer via restraining M2 macrophage polarization. Acta Pharm Sin B 2022;12:787–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.07.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

93. Chen, Z, Rao, X, Sun, L, Qi, X, Wang, J, Wang, S, et al.. Yi-Fei-San-Jie Chinese medicine formula reverses immune escape by regulating deoxycholic acid metabolism to inhibit TGR5/STAT3/PD-L1 axis in lung cancer. Phytomedicine 2024;135:156175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2024.156175.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

94. Cheng, Y, Lotan, R. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel retinoic acid-inducible gene that encodes a putative G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem 1998;273:35008–15. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.52.35008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

95. Tao, Q, Fujimoto, J, Men, T, Ye, X, Deng, J, Lacroix, L, et al.. Identification of the retinoic acid-inducible Gprc5a as a new lung tumor suppressor gene. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:1668–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djm208.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

96. Xu, J, Tian, J, Shapiro, SD. Normal lung development in RAIG1-deficient mice despite unique lung epithelium-specific expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;32:381–7. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2004-0343oc.Suche in Google Scholar

97. Jin, E, Wang, W, Fang, M, Wang, L, Wu, K, Zhang, Y, et al.. Lung cancer suppressor gene GPRC5A mediates p53 activity in non-small cell lung cancer cells in vitro. Mol Med Rep 2017;16:6382–8. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2017.7343.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

98. Zhong, S, Yin, H, Liao, Y, Yao, F, Li, Q, Zhang, J, et al.. Lung tumor suppressor GPRC5A binds EGFR and restrains its effector signaling. Cancer Res 2015;75:1801–14. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-14-2005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

99. Jin, E, Wang, W, Fang, M, Wang, W, Xie, R, Zhou, H, et al.. Clinical significance of reduced GPRC5A expression in surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett 2019;17:502–7. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.9537.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

100. Ye, X, Tao, Q, Wang, Y, Cheng, Y, Lotan, R. Mechanisms underlying the induction of the putative human tumor suppressor GPRC5A by retinoic acid. Cancer Biol Ther 2009;8:951–62. https://doi.org/10.4161/cbt.8.10.8244.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

101. Lin, Y, Wang, Y, Xue, Q, Zheng, Q, Chen, L, Jin, Y, et al.. GPRC5A is a potential prognostic biomarker and correlates with immune cell infiltration in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2024;13:1010–31. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-23-739.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

102. Fujimoto, J, Kadara, H, Men, T, van Pelt, C, Lotan, D, Lotan, R, et al.. Comparative functional genomics analysis of NNK tobacco-carcinogen induced lung adenocarcinoma development in Gprc5a-knockout mice. PLoS One 2010;5:e11847. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011847.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

103. Chen, Y, Deng, J, Fujimoto, J, Kadara, H, Men, T, Lotan, D, et al.. Gprc5a deletion enhances the transformed phenotype in normal and malignant lung epithelial cells by eliciting persistent Stat3 signaling induced by autocrine leukemia inhibitory factor. Cancer Res 2010;70:8917–26. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-10-0518.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

104. Deng, J, Fujimoto, J, Ye, XF, Men, TY, Van Pelt, CS, Chen, YL, et al.. Knockout of the tumor suppressor gene Gprc5a in mice leads to NF-kappaB activation in airway epithelium and promotes lung inflammation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev Res 2010;3:424–37. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.capr-10-0032.Suche in Google Scholar