Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder for which there are currently no effective treatment options. Increasing evidence suggests that AD is a systemic disease closely associated with the immune system, not merely a central nervous system (CNS) disorder. Immune cells play crucial roles in the onset and progression of AD. Microglia and astrocytes are the primary inflammatory cells in the brain that can sensitively detect changes in the internal environment and transform into different phenotypes to exert differing effects at various stages of AD. Peripheral immune cells, such as T cells, B cells, monocytes/macrophages, and neutrophils can also be recruited to the CNS to mediate the inflammatory response in AD. As such, investigating the role of immune cells in AD is particularly important for elucidating its specific pathogenesis. This review primarily discusses the roles of central innate immune cells, peripheral immune cells, and the interactions between central and peripheral immune cells in the development of neuroinflammation in AD. Furthermore, we listed clinical trials targeting AD-associated neuroinflammation, which may represent a promising direction for developing effective treatments for AD in the future.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive cognitive and memory impairments [1]. The typical pathological hallmarks of AD include amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) containing phosphorylated tau (p-tau) [2]. However, the failure of multiple clinical trials targeting Aβ suggests that these mechanisms may not fully explain the pathogenesis of AD [3]. Neuropathological and genetic studies have recently indicated that immune dysfunction and inflammation, especially central and peripheral immune responses, are crucial for the onset and progression of AD [4], [5], [6]. Microglia are activated by the deposition of Aβ plaques and other pathological proteins. Initially, microglia exert a neuroprotective function by clearing Aβ peptides to reduce plaque burden [7], 8]. However, the persistent presence of plaques leads to the continuous production of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and neurotoxins, ultimately damaging neurons and other cells including microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [9], 10]. Due to this vicious cycle, neurons eventually degenerate and die. Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified associations between AD and key microglial genes, including triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) [11] and CD33 [12], which are involved in innate immunity. Several recent studies have further indicated that peripheral systemic immune responses promote neurodegenerative and AD-specific pathologies [13], [14], [15]. Lymphocytes and neutrophils are crucial constituents of the peripheral immune cells, which have been found to coexist with Aβ in the brain tissue of patients with AD [16]. This evidence demonstrates that peripheral immune cells can infiltrate the brain, modulating or exacerbating the neurogenic mechanisms of AD.

The brain is generally considered an immune-privileged organ. Since the blood-brain barrier (BBB) protects the brain, communication between peripheral immune cells and the brain is limited [17]. The recent discovery of meningeal lymphatics suggests that the central and peripheral immune systems are tightly connected. Our understanding suggests that complex immune interactions occur under both steady-state and pathological conditions and that the healthy brain is involved in immunological activities while being protected by resident and infiltrating peripheral immune cells [18]. Immune cells play dual roles in the immune system. These characteristics change dynamically and shape the pathogenesis of AD through intricate mechanisms as AD progresses. This review summarizes the diverse functional states of the central and peripheral immune cells during the onset and progression of AD, highlighting their specific roles at different stages of the disease and their pathological responses. We further outline the crosstalk between peripheral and central immune cells relevant to AD. Furthermore, we discuss the impact of the BBB, meningeal lymphatics, and brain-gut axis on immune crosstalk. Additionally, we summarize the current knowledge on immune cell-related biomarkers and clinical trial drugs targeting neuroinflammation in AD.

Immune cell-mediated neuroinflammatory responses in AD

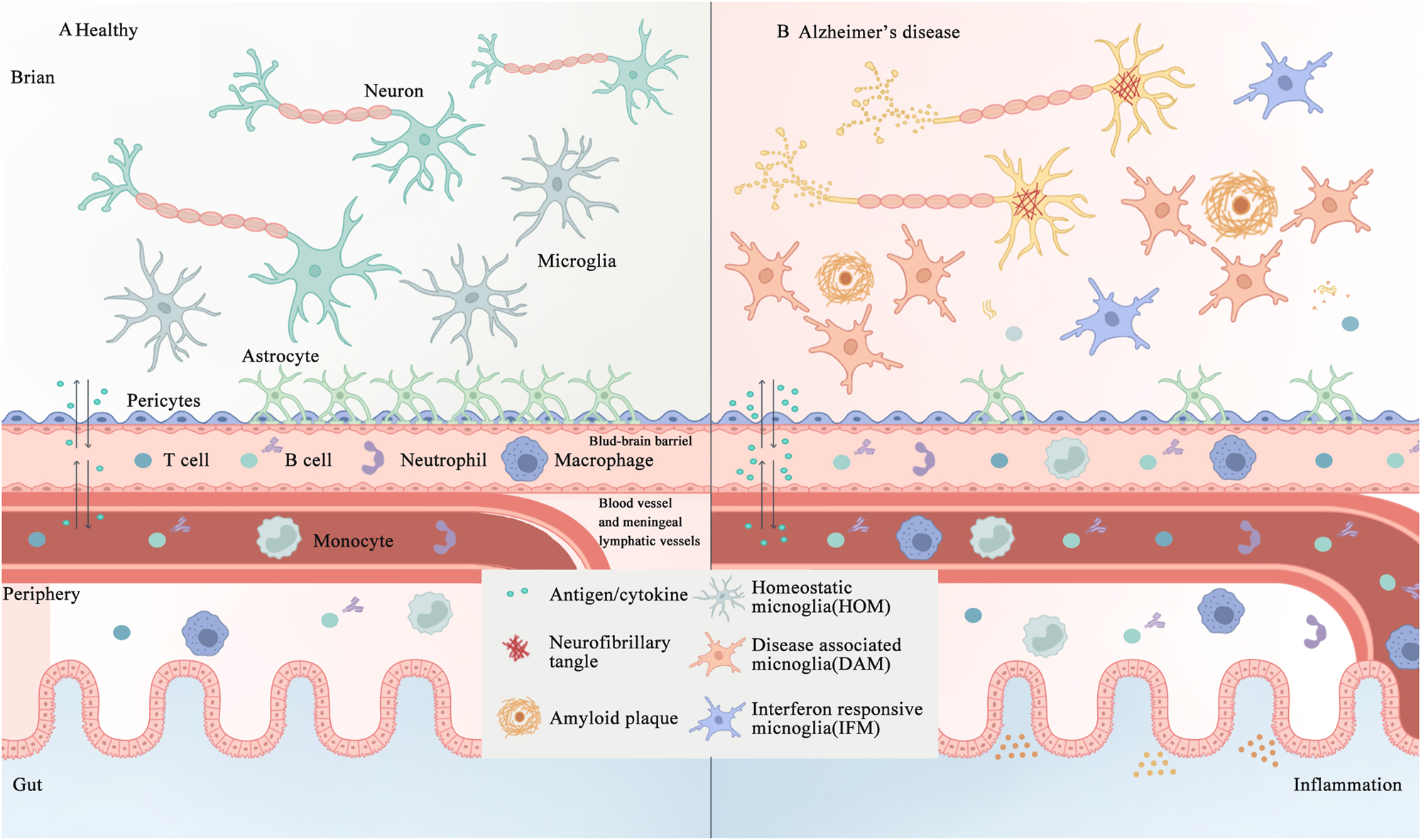

In a steady-state brain, microglia continuously monitor changes in the brain’s internal environment and initiate immune responses as needed. Microglia may trigger astrocyte-mediated immune reactions upon activation, thereby collaboratively maintaining brain homeostasis. Immune activation can exert deleterious or advantageous effects on AD. Following advances in research, it has been discovered that peripheral blood immune cells, including T cells, B cells, neutrophils, monocytes, and their derived macrophages, can also infiltrate the meninges and brain parenchyma. These cells secrete cytokines or directly interact with microglia in the central nervous system to promote central inflammation and pathology [19] (Figure 1, Table 1).

The pathological and protective mechanisms of immune cells involvement in AD.

| Pathological event cells | Genes/Molecules/Lineage markers | Possible functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microglia | TREM2-TYROBP/DAP12 | Involved in the development of microglia, regulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression, microglia migration, and propagation of Aβ | [20], [21], [22] |

| Microglia | CR1 | Activate the complement system, regulate microglial activity, and enhance the phagocytosis of immune complexes, cellular debris, and Aβ | [23], [24], [25] |

| Microglia | CD33 | Promote plaque compaction and microglia-plaque contacts, and minimize neuritic plaque pathology | [26], 27] |

| Microglia | ABCA7 | Reduce the efflux of Aβ peptides across the blood-brain barrier, decrease the phagocytosis process mediated by microglial cells, and alter the response to inflammation | [28], [29], [30] |

| Astrocytes | APOE4 | Help astrocytes to maintain homoeostatic lipid metabolism, control synaptic pruning, regulate the clearance of extracellular Aβ aggregates and cell debris, preserve BBB integrity, promote astrocytic inflammatory responses | [31], [32], [33], [34] |

| Astrocytes | GLAST/GLT-1 | Disrupt the clearance of excitatory neurotransmitters and increase levels of β-amyloid and tau from astrocytes | [35], 36] |

| Astrocytes/Microglia | JAK2-STAT3 | Disturb cholinergic neurotransmission, suppressing neuroinflammation, response to AβO administration | [37], [38], [39] |

| Astrocytes/Microglia | SIRT1 | Trigger microglia activation and response and cause oxidative damage to neurons | [40], 41] |

| CD8+ T-cells | FAS/FASL | Modulate neuronal integrity, and initiate the production of inflammasome-related cytokines and chemokines | [42], 43] |

| Th1 | IFN-γ | Increase microglial activation and Aβ deposition | [44], 45] |

| Th2 | IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, GATA3 | Reverse cognitive impairment | [45], 46] |

| Th17 | IL-17, IL-22, RORγt | Induce neuronal apoptosis or death | [47], 48] |

| Treg | CD25, FoxP3 | Induce microglia/astrocytes to phagocytose Aβ deposits in the early stage of AD, and inhibit Th1, and Th17 cell-induced neurodegeneration in the late stage of AD | [49] |

| B-cells | IL-6, TNFα, and IFNγ | Increase Aβ plaque burden and disease-associated microglia | [50] |

| Monocyte | IL-1β and TNFα | Phagocytosis of toxic elements, including Aβ | [51] |

| Neutrophil | NETs and IL-17 | Involve capillary adhesion, blood-brain barrier breaching, myeloperoxidase release, and the propensity for neutrophil extracellular trap release | [52], 53] |

-

Aβ, amyloid-β; ABCA7, ATP-binding cassette transporter A7; APOE, apolipoprotein E; BBB, Blood-brain barrier; CR1, complement receptor 1; FAS/FASL, fas cell surface death receptor/fas ligand; FOXP3, forkhead box protein P3; GATA3, GATA binding protein 3; GLAST, glutamate aspartate transporter; GLT-1, glutamate transporter-1; IFN-γ, Interferon-γ; IL-1β, Iinterleukin-1β; IL-4, Interleukin 4; IL-5, Interleukin 5; IL-6, Interleukin 6; IL-13, Interleukin 13; IL-17, Interleukin 17; IL-22, Interleukin 22; JAK2-STAT3, Janus kinase 2-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; RORγt, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γt; SIRT1, Silent information regulator sirtuin 1; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α; TREM2, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; Th1, helper T-cell 1; Th2, helper T-cell 2; Th17, helper T-cell 17; Treg, T regulatory cell.

The interplay between central and peripheral immune cells in the healthy and AD brain. A. In healthy individuals, microglial cells, astrocytes, and an intact BBB and meningeal lymphatic system collectively maintain the functionality of the brain. B. In AD, the aggregation of Aβ and formation of neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau activate immune cells, thus disrupting the integrity of the BBB, and trigger inflammation both within and outside the brain, including in the gut. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; Aβ, amyloid β-protein; BBB, blood-brain barrier.

Microglia

The role of microglia in AD

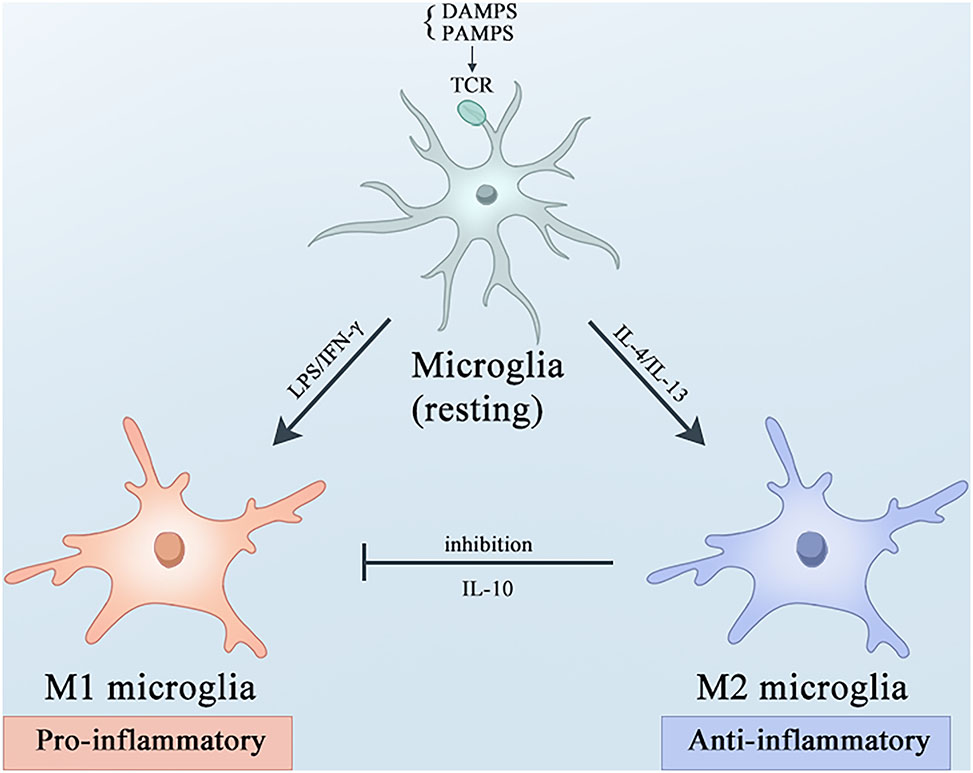

Microglia are resident macrophages in the brain, constituting approximately 10–15 % of adult central nervous system cells. This cell population plays crucial roles in brain development, maintenance of neuronal networks, and repair of damage and infection [54], 55]. As sentinels, microglia constantly monitor changes in the brain environment and switch between different activation states upon sensing signals indicating injury, infection, or other pathological conditions [56]. Activated microglia are broadly categorized into the following two types: M1, which promotes inflammation and neurotoxicity, and M2, which promotes anti-inflammatory and repair responses [57]. However, with advances in single-cell sequencing and multi-omics technologies, many distinct functional states of microglia have been identified, including disease-associated microglia (DAM), microglial neurodegenerative phenotypes (MGnD), morphologically activated microglia (PAM), and numerous unnamed subtypes [58]. In AD, research has begun to focus on the transition of microglia from the M1 to M2 phenotype. When stimulated by infection, pathological proteins or peptides, such as Aβ, microglial recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) expressed on their cell surface, subsequently becoming activated into either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory phenotypes [59], 60]. The switch between the M1 and M2 microglial phenotypes depends on environmental factors. Stimulated microglial cells can be activated via classical or alternative pathways [61]. Classical activation pathways lead to the activation of microglial phenotypes. For example, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) activate Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) containing the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain adapter to induce nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), activator protein-1 (AP-1), signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5), and interferon regulatory factor (IRF) pro-inflammatory transcription factors through both MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent pathways, resulting in microglial cells in the M1 phenotype [62]. Conversely, microglial cells are activated to the M2 phenotype via alternative activation in response to anti-inflammatory stimuli, such as interleukin (IL) -4 and IL-13 [57], 63]. Activated M2 microglial cells exert beneficial roles as they release neuroprotective cytokines, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), IL-10, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which help to resolve inflammation and promote neuronal survival [64]. Moreover, the activation of M2 microglial cells can inhibit the excessive inflammatory responses of M1 microglial cells, such as the production of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-6, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [65], [66], [67]. Under different stimuli, microglial cells can dynamically switch between the M1 and M2 phenotypes. The activation of M1 and M2 does not occur independently but represents a continuum of activation phenotypes, and different phenotypes can coexist. Therefore, accurately assessing the phenotypic characteristics of microglial cells and understanding the stage-specific switching of M1/M2 phenotypes within appropriate time windows may provide potential therapeutic insights [68] (Figure 2).

Microglial activation and polarization under basal states and amidst neuroinflammatory processes. Microglial cells undergo polarization to the M1 or M2 phenotype, accompanied by distinct immunoregulatory roles. Under resting conditions, microglia are activated by PAMPs or DAMPs via TLRs. Upon stimulation with LPS and IFN-γ, microglia polarize towards the M1 phenotype, leading to the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators, and NO. Conversely, IL-4 and IL-1β drive the alternative activation of microglia into the M2 phenotype, which dampens M1-associated functions by promoting the release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; TLRs, Toll-like receptors; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IFN-γ, interferon-gamma; NO, nitric oxide; IL-4, interleukin-4; IL-1β, interleukin-1β.

Microglial genes regulating neuroinflammation in AD

Microglia play a crucial role in AD and have been extensively validated using genomics. Nearly all late-onset AD (LOAD) GWAS risk loci (>95 % of cases) were associated with genes reported specifically or highly expressed in microglial cells [69]. Among these, TREM2 is one of the most common genetic risk factors for LOAD and is closely associated with microglia [70]. TREM2 is a cell surface protein selectively and highly expressed by microglia in the brain and peripheral bone marrow. Carrying TREM2 mutations (e.g., R47H, which accounts for approximately 0.5 % of the population) increases the risk of AD approximately threefold [5], 11]. Mutations in other microglial cell genes, such as component receptor 1 (CR1), cluster of differentiation 33 (CD33), membrane-spanning 4-domains A6A (MS4A6A), and ATP-binding cassette transporter protein (ABCA7), have also been shown to be closely associated with AD [71]. To better understand the specific mechanisms by which microglial cells contribute to AD development, it is important to consider these risk genes.

TREM2 is a cell surface receptor belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily that is widely expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) microglial cells [72]. TREM2 binds to various ligands, including bacterial lipopolysaccharides, DNA, and phospholipids. Ligand binding to TREM2 initiates a cascade of signaling events, whereby the TREM2-associated intracellular adapter tyrosine kinase-binding protein (TYROBP) is phosphorylated. Phosphorylated TYROBP recruits protein tyrosine kinase and spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), leading to the activation of downstream signaling factors including phospholipase γC2 (PLCγ2), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). PLCγ2 mediates the generation of inositol triphosphate, thus releasing Ca2+ from inositol triphosphate-gated Ca2+ stores, promoting intracellular Ca2+ elevation, and subsequently regulating cell metabolism, survival, proliferation, and phagocytic activity [72], [73], [74] (Figure 3). Hence, the normal activation of TREM2 is crucial for maintaining proper immune function. Studies have further demonstrated that elevated TREM2 expression induces microglial reprogramming, alleviates neuropathology, and improves cognitive abilities in AD mice [75]. Conversely, mutations such as R47H or deficiency in TREM2 impair Aβ degradation in primary microglial culture and mouse brain, thereby exacerbating AD-related pathology [76]. Similarly, in patients with AD harboring, the R47H variant, the coverage of microglia over neuritic and compact plaques is significantly decreased. In AD patients, this leads to an insufficient microglial response, which exacerbates plaque-associated neuronal dystrophy [77]. Furthermore, Parhizkar et al. [78] demonstrated that the functional loss of TREM2 increases the spread of amyloid plaques, further findings that the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) protein levels are strongly induced in plaque-associated microglial cells in a TREM2-dependent manner. Notably, TREM2 functions as a receptor for ApoE, triggering ApoE signaling. Targeting the TREM2-ApoE pathway restores microglial homeostasis in AD mice [79], 80]. Thus, this pathway may be a novel therapeutic target for AD treatment.

TREM2 activation and downstream signaling TREM2 binds to ligands such as Aβ, ApoE, HDL, and LDL, leading to its activation. Following activation, TREM2 interacts with the ITAMs on TYROBP, resulting in the phosphorylation of TYROBP and the recruitment of SYK. The activation of the PI3K - AKT pathway mediated by TYROBP/SYK recruits other signaling adapters, including PLCγ and MAPKs inducing an release of Ca2+. TREM2, triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells 2; Aβ, amyloid β-protein; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; ITAMs, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs; TYROBP, TYRO protein tyrosine kinase-binding protein; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PLCγ, phospholipase Cγ; MAPKs, mitogen-activated protein kinases. Created with BioRender.com.

CR1 is a member of the complement regulatory factor H family that mediates immune responses and acts as a receptor for complement components (3b/4b) in macrophages and microglial cells [81]. GWAS and multiple association studies have consistently indicated a significant correlation between CR1 polymorphisms and AD risk [82], 83]. CR1 regulates complement activity, affecting the phagocytic ability of microglial cells towards Aβ but is also associated with neuronal death [23], 84]. Crehan et al. [84] found that blocking CR1 affects the ability of microglial cells to phagocytose Aβ. This is consistent with the results of GWAS studies suggesting that CR1 mutations may lead to loss of function and reduced clearance of Aβ. Additionally, researchers have found that the CR1 protein binds to the Aβ42 peptide at its C3b binding site, thus mediating Aβ clearance [24]. These findings collectively underscore the importance of CR1 in the clearance of Aβ and its involvement in AD-related pathological processes.

CD33 (Siglec-3) is an inhibitory immune receptor and type I transmembrane protein belonging to the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin (Siglecs) family. In the brain, CD33 is expressed on the surface of microglial cells and serves as a crucial factor in the regulation of microglial function [85]. According to the GWAS results, CD33 is one of the top genes associated with the risk of AD. Two major CD33 variants, rs3865444 and rs12459419, have previously been implicated in risk of AD. CD33 is upregulated on microglial cells in the brains of patients with AD, while high levels of CD33 inhibit the uptake and clearance of Aβ by microglia [26]. The expression and selective splicing of CD33, possibly through D2 domain-dependent activation, may regulate the ability of microglial cells to clear Aβ [86]. Additionally, research has shown that TREM2 acts as a downstream target of CD33. The cross-talk between CD33 and TREM2 includes the regulation of the IL-1β/IL-1RN axis, as well as a group of genes in the “receptor active chemokines” cluster, all of which could be potential future therapeutic targets for AD [87].

ABCA7 encodes the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter A7, a member of the ABC transporter subfamily A [88]. Knocking out ABCA7 in AD mouse models may impair the phagocytic activity of microglial cells, increase amyloid protein deposition in the brain, reduce the uptake of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 oligomers by macrophages and microglial cells, and lead to memory impairment [89]. A recent study by Lyssenko et al. found that individuals who develop AD neuropathology at a younger age exhibit lower levels of ABCA7 than those who develop AD at an older age [90]. These findings highlighted the protective role of ABCA7 in AD. In summary, many at-risk genes for AD are highly expressed in microglial cells and can be expressed independently or in conjunction with other genes that regulate microglial cell functions. For example, TREM2 interacts with APOE and CD33 and plays an important role in maintaining brain homeostasis in microglial cells.

Microglia targeting therapeutics for AD

Microglia can transition into different functional states during AD progression. The application of exogenous drugs or chemical agents may shift microglial cells from an inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state. For instance, in animal models of AD, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been shown to attenuate the overactivation of microglial cells and the release of inflammatory factors, although the specific mechanisms of action still require further investigation. Current research suggests that NSAIDs may exert their effects by binding to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) [91], [92], [93]. Clinical trials that explored the use of NSAIDs in AD treatment have been disappointing, possibly because of the stage of clinical intervention [94], [95], [96]. Targeted therapies that aim at microglial cells have also been investigated. For example, given the significant anti-neuroinflammation role of TREM2, AL002, a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody that targets TREM2, was developed. It binds to the surface receptor of microglial cells, activates signal transduction, increases phosphorylation of downstream Syk, and induces microglial cell proliferation [97]. Therefore, targeting microglia may be a novel approach to preventing and treating AD.

Astrocytes

The role of astrocytes in AD

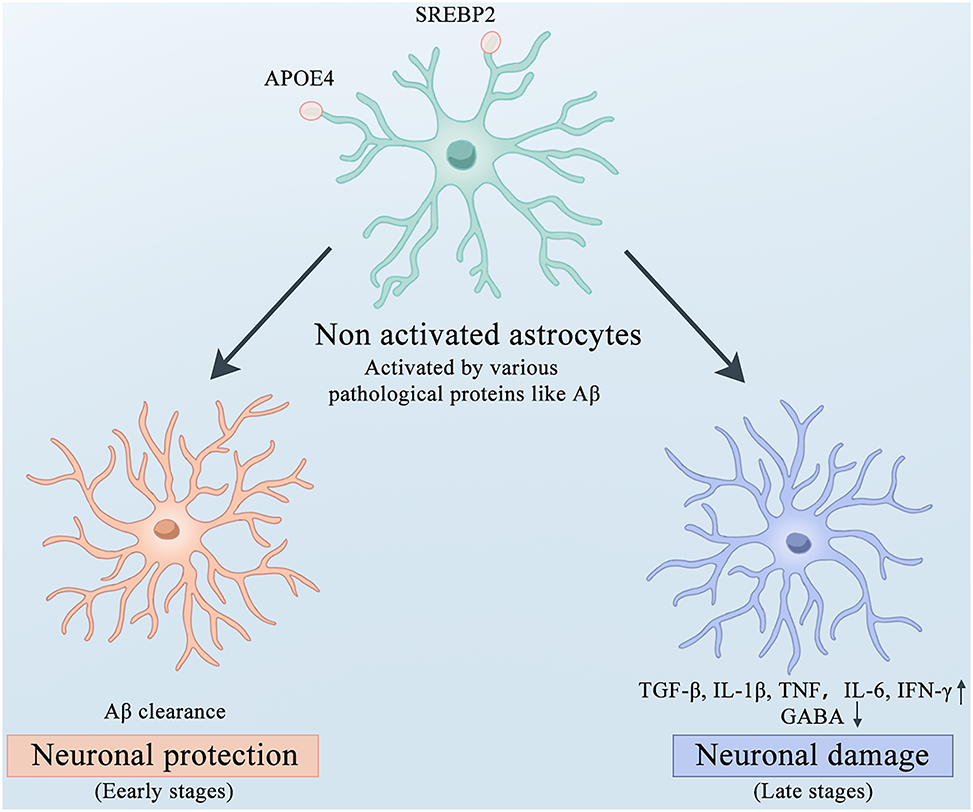

Astrocytes are the most abundant cell types in the CNS. In healthy brains, astrocytes perform various physiological functions, including neurotransmitter transmission, growth factor secretion, synaptic remodeling, and oxidative stress regulation [98], 99]. Astrocytes are major components of the BBB. The endfeet of astrocytes forms a thin barrier around endothelial cells, pericytes, and the basal lamina, playing a crucial role in interactions between the central and peripheral nervous systems [100]. Normally, astrocytes are responsible for homeostatic functions in healthy CNS. However, astrocytes, such as reactive astrocytes, undergo a series of morphological, molecular, and functional changes in response to CNS injury. Studies have found a linear increase in reactive astrocytes during AD progression, with clusters of reactive astrocytes accumulating around Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [101]. In the early stages of AD, reactive astrocytes are involved in the uptake and clearance of Aβ. The activation of astrocytes is closely associated with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin (Vim); deleting them in APP/PS1 mice increases the burden of Aβ. However, with the accumulation of Aβ, the function of reactive astrocytes may change from a protective phenotype, capable of uptake and degradation of Aβ, to a harmful phenotype, possibly capable of uptake but ineffective in its degradation [102]. Additionally, astrocytes can express different scavenger receptors, not only to clear apoptotic cells but also to facilitate Aβ uptake, particularly scavenger receptor B class member 1 (SCARB1). Studies have previously reported a significant decrease in the expression of SCARB1 in aged AD mice, leading to reduced Aβ uptake [103], 104]. Astrocytes can also promote Aβ production by releasing cytokines such as TGFβ, IL-1β, TNF, IL-6, and interferon-gamma (IFNγ) [105], 106].

Astrocytes in the CNS are regulated by a series of cell surface receptors and transport proteins, leading to impaired glutamate clearance, disrupted Ca2+ signaling, and dysregulated cholesterol metabolism. Glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS system, while excessive extracellular glutamate levels can lead to neuronal death [107]. Astrocytes maintain glutamate homeostasis by expressing high-affinity glutamate transporters, including GLAST (human homologs, EAAT1) and GLT-1 (human homolog, EAAT2) [108]. Dysfunction of glutamate transporters GLAST and GLT-1 has been confirmed in postmortem AD patient tissues and mouse models and may contribute to excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative diseases [109], 110]. Astrocytes lack voltage-gated sodium ion channels and rely on calcium ion pathways for synaptic transmission and plasticity, which are closely associated with learning and memory functions [111]. Accumulating evidence has further suggested that disrupted Ca2+ signaling functions as the pathological basis for AD progression. In AD mouse models, Aβ enhances Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes, leading to excessive Ca2+ transients near Aβ plaques [112]. However, intraventricular injection or astrocyte-specific overexpression of the calcineurin-NFAT peptide inhibitor VIVIT can restore glutamate imbalance, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal hyperactivity [113]. This suggests that calcineurin-NFAT signaling plays a significant role in neuroinflammation by downregulating calcium ion signaling in astrocytes. Cholesterol is an essential metabolic substrate required to ensure normal brain functions. Its levels are largely unaffected by dietary intake, owing to the presence of the BBB. Astrocytes express sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2) and APOE on their surfaces, facilitating cholesterol synthesis and transport [114]. The systemic overexpression of SREBP2 leads to cerebral cholesterol overload, further exacerbating AD in mouse models [115]. The expression of APOE4, the most common genetic risk factor for AD, impairs both amyloid-β uptake and cholesterol accumulation in astrocytes [116] and can activate the cyclophilin A-NF-κB-metalloproteinase 9 pathway, increasing BBB permeability and promoting neuroinflammation and AD progression [117]. Regarding the influence of APOE4 on Aβ metabolism, there is evidence to suggest that APOE4 may enhance Aβ production, however, numerous studies have found that compared to APOE3 and APOE2, APOE4 exhibits a decreased ability to clear Aβ [118], 119]. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) is the primary receptor for ApoE, mediating Aβ clearance in astrocytes and peripheral cells. However, studies have found that astrocytes expressing APOE4 exhibited reduced LRP1 expression, leading to impaired amyloid clearance in vivo [120]. In the brain, ApoE proteins are predominantly synthesized by astrocytes and microglia and are particularly important for maintaining the integrity of the BBB. A wealth of research supports the notion that ApoE4 pathogenic mutations damage the BBB integrity, induce the degeneration of brain capillary pericytes, and increase BBB permeability [121], 122]. A compromised BBB makes the brain more susceptible to toxins and pathogens, thereby increasing the risk of neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration (including AD) [123], 124] (Figure 4).

The roles of astrocytes in different stages of AD. Microglia express APOE4 and SREBP2 on their surfaces. Upon activation by various pathological proteins, microglia can clear Aβ and exert neuroprotective effects in the early stages of AD. However, in the late stages of AD, they secrete large amounts of inflammatory factors such as TGFβ, IL-1β, TNF, IL-6, and IFNγ accompanied by disturbances in GABA metabolism, which exacerbate neuronal damage. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; APOE4, Apolipoprotein E4; SREBP2, Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 2; Aβ, amyloid β-protein; TGFβ, Transforming Growth Factor beta; IL-1β, Interleukin-1 beta; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor; IL-6, Interleukin-6; IFNγ, Interferon gamma.

Astrocytes targeting therapeutics for AD

Astrocytes exhibit different reactive states. Drugs that block toxic astrocytes may slow the progression of AD. TNFα is a neuroinflammatory cytokine, and TNFα antagonists can block the transformation of astrocytes into a neurotoxic phenotype. In a case-control experiment, treatment with etanercept (a TNFα inhibitor) reduced the relative risk of developing AD in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Glucocorticoids have anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties. In vitro studies have suggested that glucocorticoids exert anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects by downregulating nitric oxide (NO) production in astrocytes, thereby inhibiting cortical astrocyte proliferation. However, current clinical trials have failed to find significant differences in the improvement of cognitive function between patients treated with glucocorticoids and those treated with a placebo [125], [126], [127]. In addition, manipulating astrocyte-mediated glutamate uptake to reduce neuronal toxicity and regulate synaptic function is a promising therapeutic approach. Treatment with the antibiotic ceftriaxone can increase the expression of EAAT2 in astrocytes and restore glutamatergic neurotransmission, and has shown beneficial effects in preclinical models of AD [128], 129].

Effects of peripheral immune cells in AD

T-cells

The role of T-cells in the pathogenesis of AD

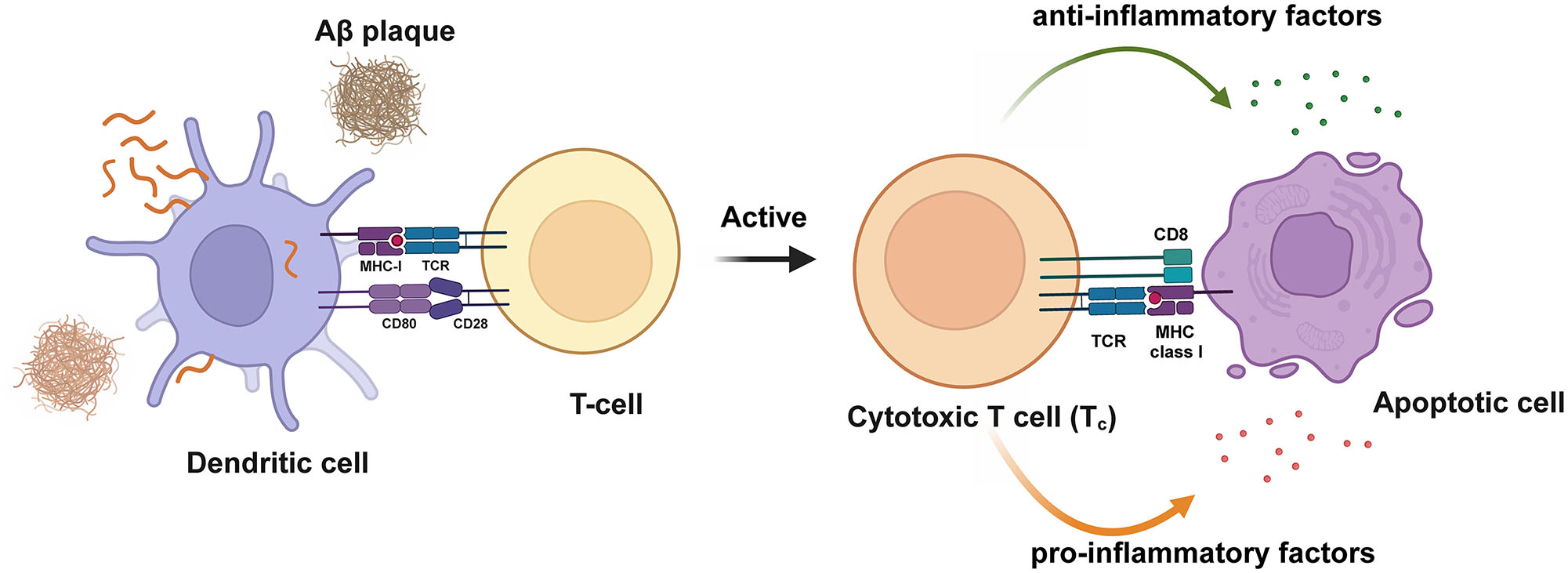

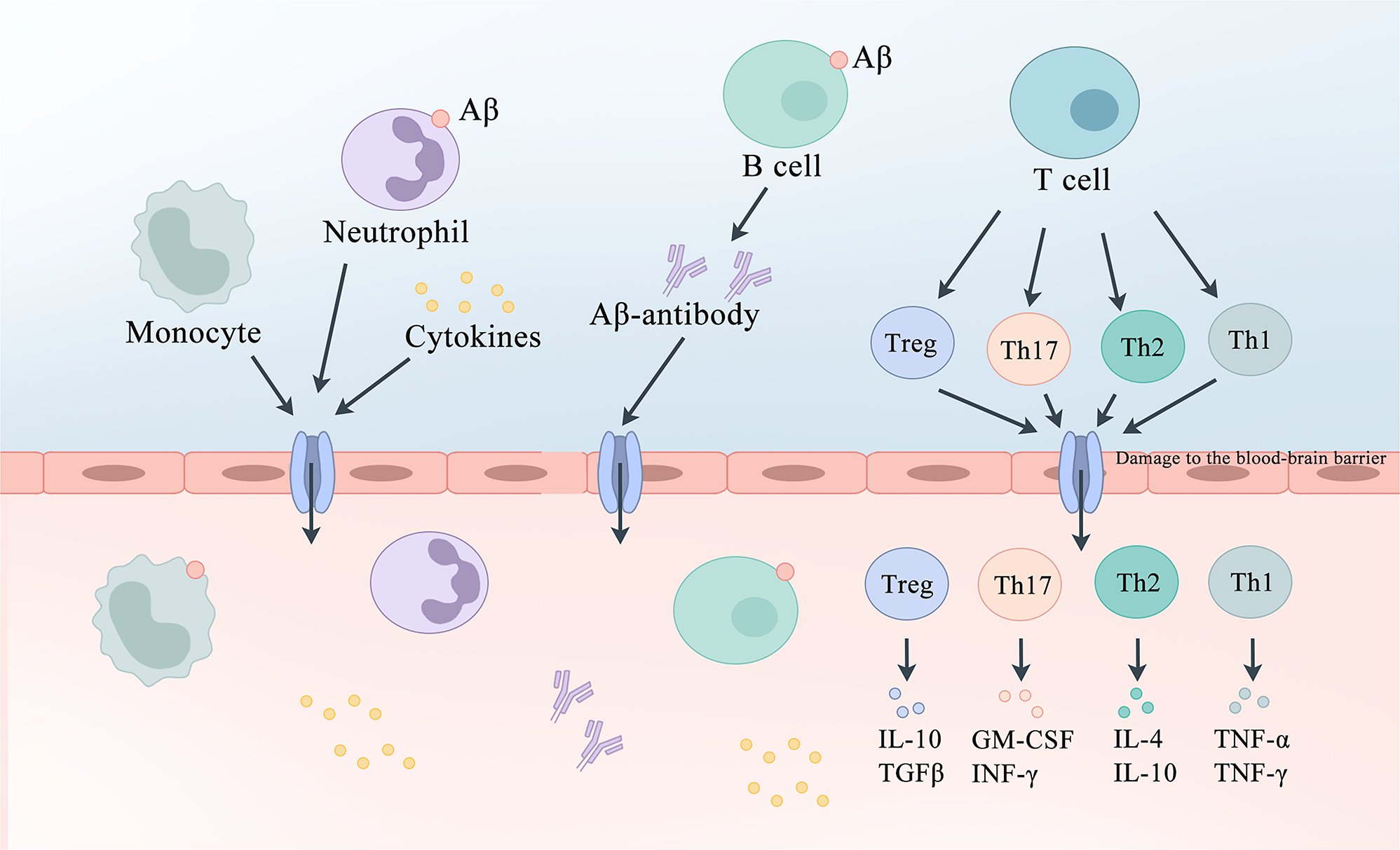

T-cells are key cells of the adaptive immune system, and their dysregulation can lead to the recognition of self-antigens as foreign antigens, resulting in harmful autoimmune reactions. T-cells originate from lymphoid progenitor cells in the bone marrow, migrate to the thymus, and differentiate into two distinct functional subsets. In the absence of antigen-specific stimulation, T-cells are referred to as naïve. Once in circulation, T-cells can interact with antigen-presenting cells (APCs) expressing major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, which present foreign (non-self) or self-antigens to T cells via the T cell receptor (TCR), thereby activating naïve T-cells and differentiating them into activated effector and memory T-cells [130]. Effector T-cells are typically divided into cytotoxic (CD8+) and unknown “helper” (CD4+) T cells. CD8+ T-cells can directly kill target T-cells by releasing perforin and granzymes to create pores in the target T-cells membrane, or by inducing apoptosis through the Fas-FasL pathway by binding to Fas molecules on the target T-cells surface [131]. CD4+ T-cells are further subdivided into subsets based on their cytokine expression and functions. Type 1 T helper (Th1) releases pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ or TNFα. Th2 cells typically produce anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13, Type 7 T helper (Th17) cells release IL-17/IL-22. T follicular helper (Tfh) cells help B-cells in the synthesis of specific antibodies by producing IL-21 and expressing Bcl6. Foxp3-expressing Treg cells, distinct from Th1/type 2 T helper (Th2)/Th17/Tfh effectors, act as regulatory immune cells to modulate immune responses, maintain immune cell homeostasis, and prevent pathological immune reactions [132], [133], [134]. Increasing evidence suggests that the immune responses related to T cells are related to AD. Infiltrating T-cells were first discovered in the postmortem brains of patients with AD in 1988 [13], and as research progressed, T-cell infiltration has further been found in different brain regions of patients with AD [135], 136]. Activated T-cells (CD25 and HLA-DR positive) have also been detected in the CSF of patients with AD [137]. Additionally, Aβ-reactive T cells have been found in the peripheral blood of patients with AD [138]. These findings indicate that T cell-mediated immune responses play a significant role in the immune and pathological processes of AD (Figure 5).

Activation of T-cells in AD. Dendritic cells present antigens to T-cells, activating T-cells and releasing pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines.Aβ, amyloid β-protein. Created with BioRender.com.

However, the role of T cells in the pathogenesis of AD has not been widely studied, although a close association between T cells and pathological changes in AD has been proposed [139]. The brain parenchymal infiltration of T-cells associated with Aβ deposition has been reported in postmortem samples from AD patients and mouse models. Th1 cells are Aβ-specific reactive cells, and the release of IFN-γ by Th1 cells significantly accelerates disease markers in AD animal models [44]. Elevated levels of Th17 cells in AD may also be detrimental and induce neuronal apoptosis through the release of pro-inflammatory factors, such as FasL, IL-17, and IL-22 [47]. However, studies have further reported that the infusion of Th2 cells into an APP/PS1 mouse model could improve cognitive impairment and pathological damage in mice. Additionally, Treg cells appear to be important in AD, as Treg-produced cytokines TGF-β and IL-35, along with the specific transcription factor Foxp3, were found to be decreased in the cortex and hippocampus of patients with AD [140]. The latest research reported that by specifically regulating the state of Tregs, microglial activation can be triggered to modulate neuroinflammation, improve cognitive impairment, and reduce Aβ accumulation in AD animal models. These findings confirm that the regulatory mechanisms of Tregs are impaired in patients with AD. Low-dose IL-2 can induce Treg expansion, effectively modulating neuroinflammation, and alleviating AD. Phase I clinical trials on the effects of low-dose IL-2 are ongoing [141].

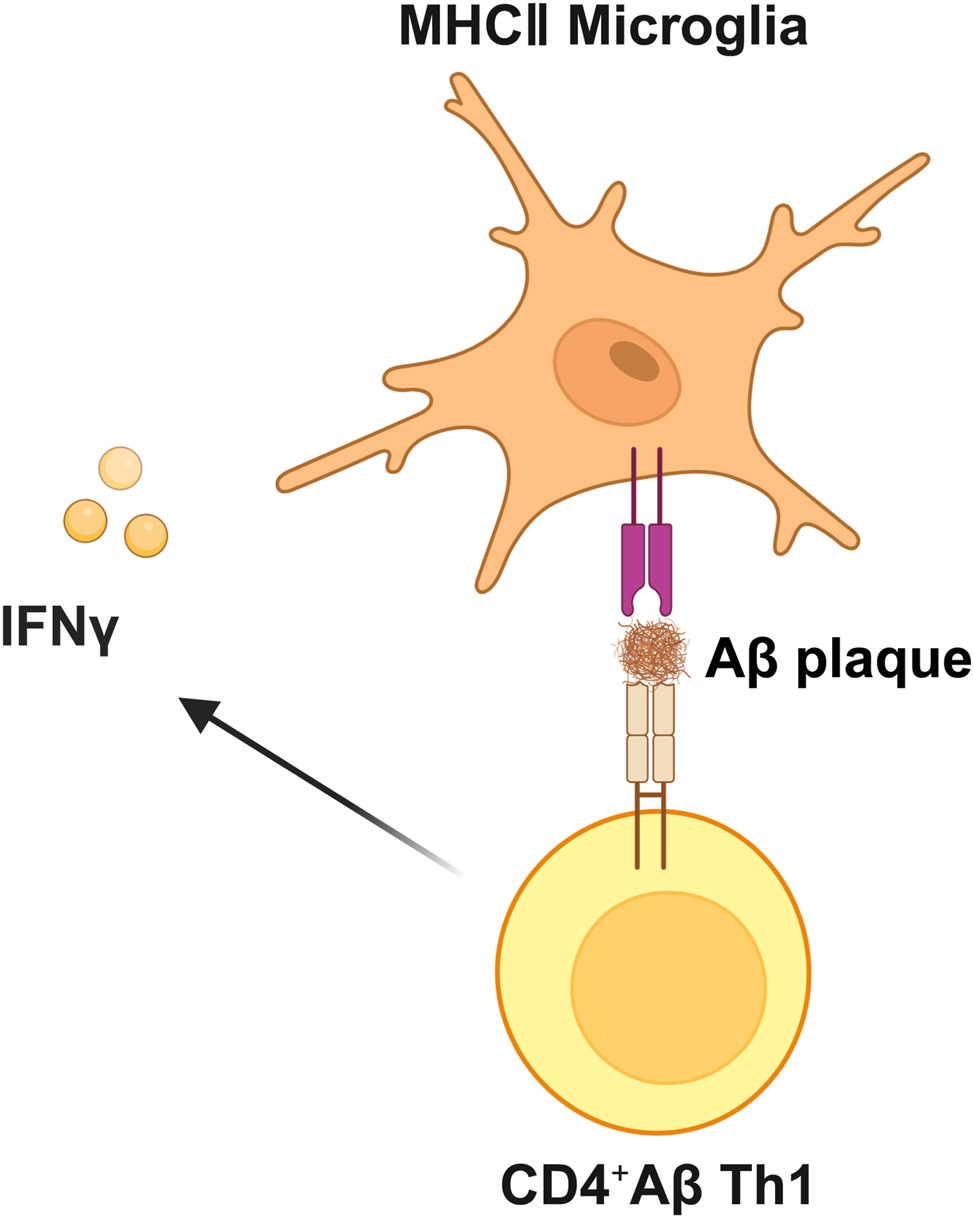

Crosstalk between T-cells and microglia

The crosstalk between T cells and microglia contributes to nervous system stability. Some studies have suggested that the interaction between microglia and infiltrating CD4+ T cells plays a critical role in coordinating immunoregulatory mechanisms underlying AD pathogenesis [142], 143]. For example, Aβ-specific CD4+ Th1 cells induce the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) on microglia, which alleviates AD-like pathology in the 5XFAD mouse model, possibly mediated by the IFN-γ cytokine signaling pathway [143] (Figure 6). Conversely, the injection of Aβ-specific CD4+ Th1 and Th17 cells into the brains of APP/PS1 mice exacerbates Aβ load, microglial proliferation, neuroinflammation, and cognitive impairment [143]. These studies underscore the key and complex disease-modifying role of CD4-T cells in AD pathogenesis. One article evaluating the age-related CNS infiltration of T-cells found that T-cell entry into the brain was associated with activated microglia and cognitive impairment [144]. Additionally, research suggests that infiltrating T-cells may alter microglial phenotypes, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration. Therefore, studying the influence of peripheral immune cells (including different subsets of infiltrating CD4+ T cells and other cells) on microglia and their interactions with neuronal cells during AD pathogenesis is crucial [145].

Crosstalk between T-cells and microglia in AD. Aβ-specific CD4+ Th1 cells induce the expression of major histocompatibility MHCII on microglia, potentially mediated by the IFN-γ cytokine signaling pathway. Aβ, amyloid β-protein; Th1, type 1 T helper; MHCII, major histocompatibility complex class II; IFN-γ, interferon-gamma. Created with BioRender.com.

T-cell targeting therapeutics for AD

Different T-cell subtypes play varying roles in AD, and the transplantation or depletion of different T-cell subtypes in AD mice has the potential to alter the progression of AD pathology. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), consisting of over 98 % human immunoglobulin G (hIgG), is increasingly used to treat various diseases and is generally safe and well-tolerated [146], 147]. In 2013, the results of a large clinical study using IVIg to treat AD showed no improvement in cognitive scores in patients with mild to moderate AD at the study dose; however, subgroup analysis showed improvement in cognitive endpoints in APOE4 carriers [148]. Additionally, peripheral T-cells to the choroid plexus (CP), disrupt Treg-mediated systemic immune tolerance, maintain the activation of astrocytes, and remove Aβ plaques, ultimately improving cognitive deficits. The beneficial immunomodulatory effect in APP/PS1 mice suggests a promising strategy for AD therapy [149]. Holtzman et al. [150] treated human tau (P301S) transgenic AD mice aged 8.5–9 months (the time window for brain atrophy) with one week of PD1-PDL1 immune checkpoint blockade therapy. The results showed that increased levels of immunosuppressive FOXP3+CD4+ Tregs and PDCD1+FOXP3+CD4+ Tregs, significantly reduced tau-mediated neurodegeneration and p-tau staining, further indicating that T-cells may play a key role in tau-mediated neurodegeneration. This suggests that future immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies may extend from the field of tumors to the treatment of AD [150].

B-cells

Role of B-cells in the pathogenesis of AD

B cells, which originate from hematopoietic stem cells are the cornerstone of humoral immunity and play a critical role in the immune system [151]. Upon encountering specific antigens and T cells, B cells further differentiate into plasma cells that secrete specific antibodies or memory B cells [152]. In addition to antibody production, mature B-cells serve as unique professional antigen-presenting cells. When antigens recognized by the B-cell receptor (BCR) are presented to T-cells that recognize the same antigen, the efficiency and specificity of antigen presentation by memory B-cells are higher than those of other APCs [153]. Conversely, B-cells can also participate in coordinating the immune responses by producing a wide range of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. B-cells release cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) to promote inflammatory responses and can also secrete IL-10 and IL-35 to exert anti-inflammatory effects [154] (Figure 7).

Functions of B-cells in AD. Mature B-cells can act as specialized antigen-presenting cells, presenting antigens to T-cells. On the other hand, B-cells release cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and GM-CSF to promote inflammatory responses, while also secreting IL-10 and IL-35 to exert anti-inflammatory effects. Aβ, amyloid β-protein; IL, interleukin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Created with BioRender.com.

Compared to healthy individuals, the absolute number and percentage of B cells in the peripheral blood of patients with AD are decreased, and this decrease in the number of B cells is correlated with the severity of AD, indicating that B cells may play an important role in AD [155]. However, the specific mechanisms through which B cells affect AD are not fully understood. B cells can mitigate Aβ pathology and memory impairments in transgenic AD mouse models by producing immunoglobulins [139]. B cells secrete AD-ameliorating cytokines [156]. Although B cells have long been considered to have neuroprotective effects, recent research has suggested that they may contribute to the progression of AD-related pathologies and diseases. In animal models of AD, genetic or transient loss of B cells alleviates AD-related pathologies, indicating a significant negative impact of B-cells on AD progression [139]. In transgenic AD mice, depletion or inactivation of B cells at the early stages of AD pathology can restore TGFβ+ microglia, yielding beneficial therapeutic effects. TGFβ+ microglia have the enhanced ability to clear Aβ oligomers and slow AD progression [50]. Research has shown that in the 3xTg AD mouse model, therapeutic B-cell depletion can significantly reduce β-amyloid plaque load and reverse learning and memory deficits in mice [50]. Furthermore, this study indicates that while B cells infiltrating the brain parenchyma can produce potentially beneficial IgG around β-amyloid plaques, they also exacerbate AD-like pathology [50]. Therefore, further research is needed to thoroughly investigate the effects of targeting B cells.

B-cell targeting therapeutics for AD

In AD, naturally occurring antibodies to β-amyloid (NAbs-Aβ) can be generated through humoral immunity. NAbs-Aβ is currently believed to have a preventive effect against AD. Compared to healthy controls, patients with AD have lower levels of self-antibodies targeting different Aβ epitopes in their blood [157]. Unlike monoclonal antibodies that target Aβ, NAbs-Aβ antibodies are polyclonal and can bind to a broader range of Aβ epitopes. Therefore, intravenous injection of immunoglobulin G containing NAbs-Aβ has been tested in a phase III trial for treating AD. However, the treatment outcomes were negative [158]. In this study, the recruited patients with AD were already in the late stage of disease progression. This may be the reason for the suboptimal intervention effects.

Monocytes/macrophages

The role of monocytes/macrophages in the pathogenesis of AD

Peripheral blood monocytes in humans originate from myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow [159]. In steady-state circulation, monocytes migrate between lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs and are recruited to tissues with severe inflammation, where they differentiate into macrophages (Mφ) or dendritic cells (DC) to clear pathogens. They play crucial roles in the immune response through phagocytosis, cytokine production, and antigen presentation [160]. Human peripheral blood monocytes primarily consist of three subsets: classical (CD14+, CD16−), intermediate (CD14+, CD16+), and non-classical (CD14dim, CD16+) [161]. Different subsets have different functions in AD, with the intermediate subset exhibiting the highest Aβ uptake capacity. Compared to healthy individuals, the Aβ uptake capacity of each subset is reduced in patients with AD [162]. In the prodromal or early stages of AD, monocyte activation may play a neuroprotective role by further promoting the clearance of Aβ from the blood, thereby reducing its accumulation in the brain. However, in the later stages, monocyte function appears to be impaired as phagocytic activity decreases and shifts toward a more pro-inflammatory state, thereby exacerbating neuroinflammation and promoting AD progression [162], 163].

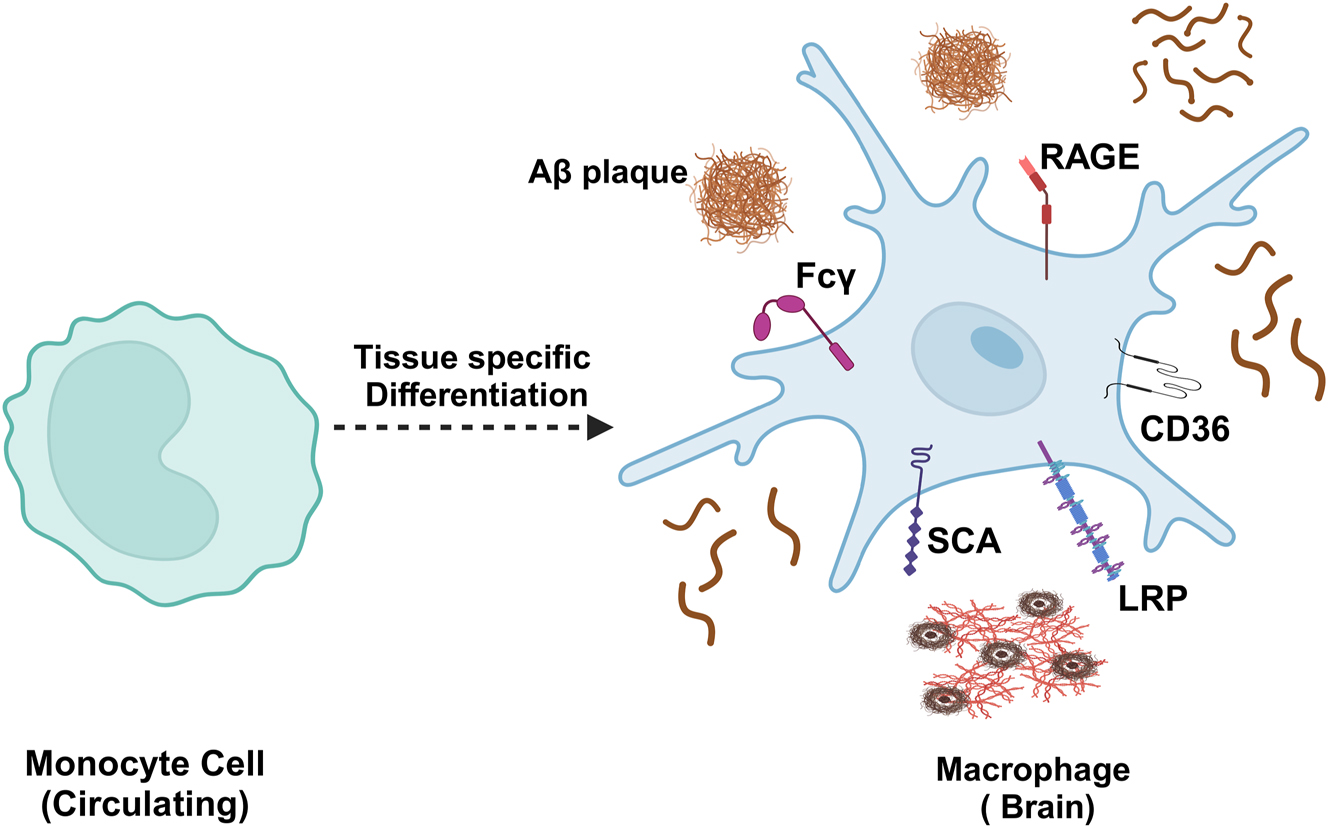

As AD progresses, it triggers the recruitment of leukocytes, including monocytes, into the brain. Studies have found an increase in GFP-positive cells in the brains of the APP/PS1-dE9 mouse model of AD, indicating that AD can promote the recruitment of bone marrow-derived leukocytes into the brain [164]. By using GFP-expressing bone marrow chimeric mice expressing APP, researchers compared GFP-positive cells in aged and young mice, finding a significant increase in these cells in the brains of aged mice [165]. Additionally, another study found that monocytes regulate blood levels of Aβ and might be involved in the development of AD. The recovery of Aβ uptake function by blood monocytes represents a potential therapeutic strategy for AD [162]. Research has indicated that during the neuroinflammatory stage of AD, blood-derived monocytes can cross the BBB and differentiate into bone marrow-derived macrophages with characteristics similar to microglia, which are more efficient at clearing Aβ than resident microglia [164], [166]–168]. Under steady-state conditions, monocytes can differentiate into perivascular, meningeal, and choroidal plexus macrophages at the border [169]. Monocytes infiltrate the brain and/or Aβ deposition sites in AD in response to chemokines, inflammatory mediators secreted by Aβ, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [170], [171], [172], [173]. Blood-derived monocytes entering the brain parenchyma express various receptors to clear Aβ, including Fcγ receptors, scavenger receptor A (SCA), CD36, RAGE, and low-density lipoprotein receptor-associated protein (LRP) [51] (Figure 8). Additionally, Vanessa Donega et al. found that exposure of human monocyte-derived microglial-like (MDMi) cells to Aβ oligomers induced an increase in the expression of metallothioneins, which are involved in metal ion regulation, protecting against oxidative damage, thus and possessing anti-inflammatory properties [174].

Monocytes in the brain. Blood-derived monocytes entering the brain parenchyma express various receptors to clear Aβ, including Fcγ, SCA, CD36, RAGE, and LRP receptors.Aβ, amyloid β-protein; SCA, scavenger receptor A; CD36, cluster of differentiation 36; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end-products; LRP, low-density lipoprotein receptor-associated protein. Created with BioRender.com.

Monocytes/macrophages targeting therapeutics for AD

Current research suggests that monocytes may be beneficial throughout the AD course, and regulating them could potentially be used to clear excess Aβ in the brain. The immunomodulatory drug glatiramer acetate (GA), is widely used to treat multiple sclerosis (MS) and has been shown to increase brain infiltration of monocyte-derived macrophages. Researchers found that weekly immunotherapy with glatiramer acetate or injection of transplanted CD115 monocytes into the peripheral blood of transgenic APPswePS1ΔE9 mice delayed AD progression by increasing levels of MMP9 protein (an enzyme capable of degrading Aβ) and monocyte infiltration into the brain [175]. Muramyl dipeptide (MDP), a ligand for the NOD2 receptor, is a drug with mild immunomodulatory effects that specifically targets certain subsets of monocytes without activating microglia. In one study, different frequencies of MDP administered intraperitoneally to male APPswe/PS1 transgenic mice resulted in the conversion of Ly6Chigh to Ly6Clow monocytes (Ly6Clow monocytes play crucial roles in the pathology of AD) which was associated with improved memory function, expression of synaptic plasticity markers, and increased Aβ clearance [176]. The phenotype and function of monocytes/macrophages were evaluated in individuals with subjective memory complaints (SMC), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and AD and compared with cognitively healthy controls. Higher levels of reactive oxygen species are found in the monocytes of patients with SMC, with the most pronounced activation of peripheral blood monocytes (hyperactivation) in the MCI group. Chemotaxis, reactive oxygen species generation, and cytokine production by monocytes increased significantly following stimulation with TLR2 and TLR4 [177]. Collectively, these studies suggest that using monocytes and macrophages to compensate for the intrinsic microglial dysfunction holds therapeutic promise.

Neutrophils

The role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of AD

Neutrophils are the most abundant type of white blood cells in the body. Neutrophils are involved in inflammatory responses by clearing pathogens through phagocytosis, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) via myeloperoxidase activity, degranulation, and the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [178]. They serve as the first line of defense against pathogens. Neutrophils exhibit various beneficial effector functions [179]. However, during prolonged tissue stress and damage-induced sterile inflammation, neutrophils can exert subtle harmful effects that cause chronic tissue damage. If not controlled, it can promote pathological conditions, such as autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases [180].

The role of neutrophils in AD pathogenesis is gaining support. In the brains of patients with AD, infiltrating neutrophils have been detected and found to coexist with Aβ deposits in brain tissues [52]. The adhesive function of neutrophils plays a significant role in AD. Neutrophil adhesion and migration in patients with AD are positively correlated with disease severity, indicating that neutrophils are involved in AD-related chronic inflammation [181]. Baik et al. further demonstrated the real-time imaging of neutrophil entry into the brain parenchyma in the 5xFAD mouse model, a phenomenon not observed in wild-type control mice. Importantly, neutrophils entering the parenchyma remained motile and accumulated around Aβ plaques in AD mice [182]. Subsequently, Zenaro et al. validated this process, finding that lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) promoted neutrophil infiltration [52]. Studies on transgenic mouse models of AD have reported that depletion of neutrophils reduces Aβ-like pathology and improves cognitive impairment in mice. In the early stages of AD, blocking integrin LFA-1 in 3xTg-AD mice prevents neutrophil adhesion and brain infiltration, reduces AD neuropathological features, and improves learning and memory. Additionally, experiments involving neutrophil depletion or blocking of neutrophil adhesion and infiltration in the early stages of the disease using anti-Gr1, anti-Ly6G, or anti-LFA-1 antibodies have shown improved cognitive function in mice [52]. In addition, the accumulation of neutrophils in blood vessels may damage normal vascular function and BBB. Neutrophil accumulation can lead to stagnation of capillary blood flow (CBF), reducing blood perfusion in adjacent brain areas and exacerbating cognitive dysfunction in mouse models [183]. Vascular dysfunction has been observed in patients with AD before cognitive impairment becomes evident, and it is associated with reduced CBF, inadequate perfusion, disruption of endothelial tight junctions, neuronal death, and infiltration of immune cells in the brain, including neutrophils [184], 185]. Peripheral neutrophil-related soluble factors, including TNF, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), myeloperoxidase (MPO), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta (MIP-1β), are associated with cognitive decline in patients with mild AD [186].

Neutrophils targeting therapeutics for AD

Inhibiting neutrophils may be beneficial for AD. Therefore, reducing neutrophil infiltration in the brain or inhibiting their migration may be effective therapeutic approaches for alleviating AD. Antibodies against interleukin-17A (anti-IL-17A) and interleukin-23 (anti-IL-23) are known to interfere with neutrophil infiltration in psoriasis and are also used to treat various diseases such as psoriasis, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and airway hyperresponsiveness [187]. Clinical trials in patients with psoriasis have not reported severe neutrophil depletion, suggesting that anti-IL-17A therapy may be promising as a potential treatment strategy for patients with AD [188]. Heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans play an essential role in the release, uptake, and misfolding of Aβ. Recent studies have shown that HS derived from porcine mucosa can enhance the clearance of peripheral circulating Aβ1-42 by augmenting phagocytosis by neutrophils, reduce the peripheral flow of Aβ1-42 into the brain, alleviate neutrophil infiltration, attenuate neuroinflammation, and thereby improve cognitive deficits in APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice [189]. Targeting neutrophil migration may be a promising therapeutic approach in the future. However, the mechanisms underying neutrophil migration, accumulation, and CNS parenchymal tissue damage are not yet fully understood. Further research to elucidate these aspects is warranted.

Channels of communication between the periphery and the center: the BBB and meningeal lymphatics

Although the role of the immune system in the development of AD is not entirely clear, current research suggests that peripheral immune cells are paramount to AD pathogenesis. This is not only because infiltrative peripheral immune cells have been found in or near the CNS, but also because increasing evidence suggests interactions between peripheral and central immune cells. For a long time, the brain was considered an immune-privileged site. However, the mechanisms by which peripheral immune cells enter the brain and exert their effects are yet to be fully elucidated. Two aspects should be considered: the BBB and meningeal lymphatic system.

BBB breakdown during AD pathogenesis

The BBB, located at the interface between the blood and brain tissue, is composed of vascular endothelial cells that are tightly connected to astrocytes and pericytes. These tight connections limit the migration of lymphocytes from blood and prevent the entry of pathogens and immune cells into the CNS. Under physiological conditions, the BBB separates the CNS from the peripheral immune system. Increasing evidence suggests that changes in the BBB may serve as predisposing factors for and the progression of various neurodegenerative diseases, such as late-onset AD [190]. Other findings in AD cases indicate that dysregulation of interactions between endothelial cells, vascular pericytes, and astrocytes contributes to BBB disruption [191]. Astrocytes, the most abundant glial cells in the CNS, extend their processes around blood vessels and secrete homeostatic soluble factors that play a crucial role in maintaining the structure and function of the BBB. In patients with AD, activated astrocytes express high levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein near Aβ plaques, enhancing their phagocytic capacity. Activated astrocytes undergo morphological changes, including swollen endfeet and somata shrinkage and possess loss, contributing to the disruption of vascular integrity at the capillary and arteriolar levels (Figure 9).

The potential role of peripheral immune cells in AD. In AD, the BBB is compromised, allowing peripheral immune cells located at the meningeal borders to be stimulated by antigens such as Aβ. T-cells release cell-derived cytokines such as IL-12, IL-4, TGF-β, and IL-6 to regulate the development of Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg cells, which subsequently secrete anti or pro-inflammatory factors to modulate neurons. Antigens can also directly stimulate B-cells, which on the one hand produce antibodies to eliminate Aβ and on the other hand secrete inflammatory factors to regulate the immune response. Blood-derived monocytes can cross the BBB and differentiate into bone marrow-derived macrophages with microglia-like properties, which are more effective at clearing Aβ than resident microglia. Neutrophils migrate to the brain parenchyma and secrete inflammatory factors. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; Aβ, amyloid β-protein; BBB, blood-brain barrier; IL-12, Interleukin-12; IL-4, Interleukin-4; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; IL-6, Interleukin-6; Th1, T-helper 1 cells; Th2, T-helper 2 cells; Th17, T-helper 17 cells; Treg, regulatory T-cell. BBB, blood-brain barrier.

In patients with AD, pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, NO, ROS, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) released by chronically activated peripheral and central immune cells may all impair the integrity and permeability of the BBB, thus leading to the entry of potentially neurotoxic substances from the periphery into the brain, thereby accelerating neuronal damage [192]. Over a decade ago, electron microscopy was used to identify abnormalities in the ultrastructure of pericytes in the cortical regions of patients [193]. More recent studies have confirmed this finding, revealing a significant reduction in pericytes in the hippocampus and cortex of patients with AD compared to normal individuals, along with an increase in soluble markers of pericyte injury such as PDGFR-β in the CSF of patients with AD [194], 195]. Furthermore, pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress have been shown to affect the tight junctions of brain vascular endothelial cells [196], 197], whereas MMPs can degrade the endothelial basement membrane necessary for BBB integrity [198], thereby affecting BBB permeability and integrity. Recently, it was also discovered that brain border macrophages located near the blood vessels and meninges can alleviate AD-related pathological changes by regulating the CSF flow, suggesting that targeting these peripheral border macrophages may offer therapeutic benefits in AD [199].

The gut microbiota (GMB) regulates the permeability of the BBB, which is composed of trillions of bacteria, archaea, protozoa, viruses, and fungi, and has been shown to potentially modulate neuroinflammation in a variety of neurological disorders, including AD [200], [201], [202]. Changes in GMB have further been observed in patients with AD compared to those without AD [203], 204]. Moreover, GMB manipulation in AD mouse models has been shown to alter pathology and neuroinflammation [205], 206]. Studies have suggested that GMB regulates BBB permeability through its metabolites derived from GMB [207], 208]. Research has further found that Germ-free mice exhibit increased BBB permeability due to the decreased expression of tight junction proteins during fetal development, a reduction that persists into adulthood. Recolonization of germ-free mice with conventional microbiota reversed these effects. Additionally, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) have been shown to regulate the expression of tight junction proteins, suggesting that changes in BBB permeability due to SCFA production by GMB are one underlying mechanism [207]. Another study showed that a different GMB-derived metabolite, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), enhanced BBB integrity by altering the expression of claudin-1 (a tight junction protein). TMAO also limits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated memory impairment by restricting neuroinflammation mediated by microglia and astrocytes [208]. Overall, these studies suggested that GMB influences BBB integrity via its metabolites. However, further research is needed to elucidate the relationship between GMB, BBB, and AD.

Impaired meningeal lymphatic vessels in AD

The meningeal immune system is primarily composed of the meningeal lymphatic vessels, which are crucial for understanding the bidirectional interactions between the peripheral and central immune cells. The meningeal lymphatic system further contributes to brain homeostasis by facilitating the exchange of soluble substances between the CSF and the interstitial fluid [209]. The directed flow of CSF in the brain leads to the non-selective clearance of metabolic waste, including Aβ and Tau [210], [211], [212]. Impaired lymphatic drainage due to sleep disorders or chronic damage has also been associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [213]. Reduced meningeal lymphatic drainage is also associated with age-related cognitive decline and impaired CSF recirculation in the glymphatic system of the brain. Lymphatic vessels are the primary pathway for the drainage of large and small molecules from the CSF. Studies have further reported that defects in the age-related C-C chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) lead to reduced meningeal lymphatic inflow, cognitive impairment, and increased Aβ deposition in 5xFAD mice [214], 215]. Additionally, one study revealed that APOE promotes the premature constriction of meningeal lymphatic vessels, thereby impairing their function [216]. Consequently, the impaired function of meningeal lymphatic vessels reduces the clearance rate of Aβ, indicating that the meningeal lymphatic system is a novel target for regulating the pathological processes of AD and is a critical structure connecting the central and peripheral immune systems [217].

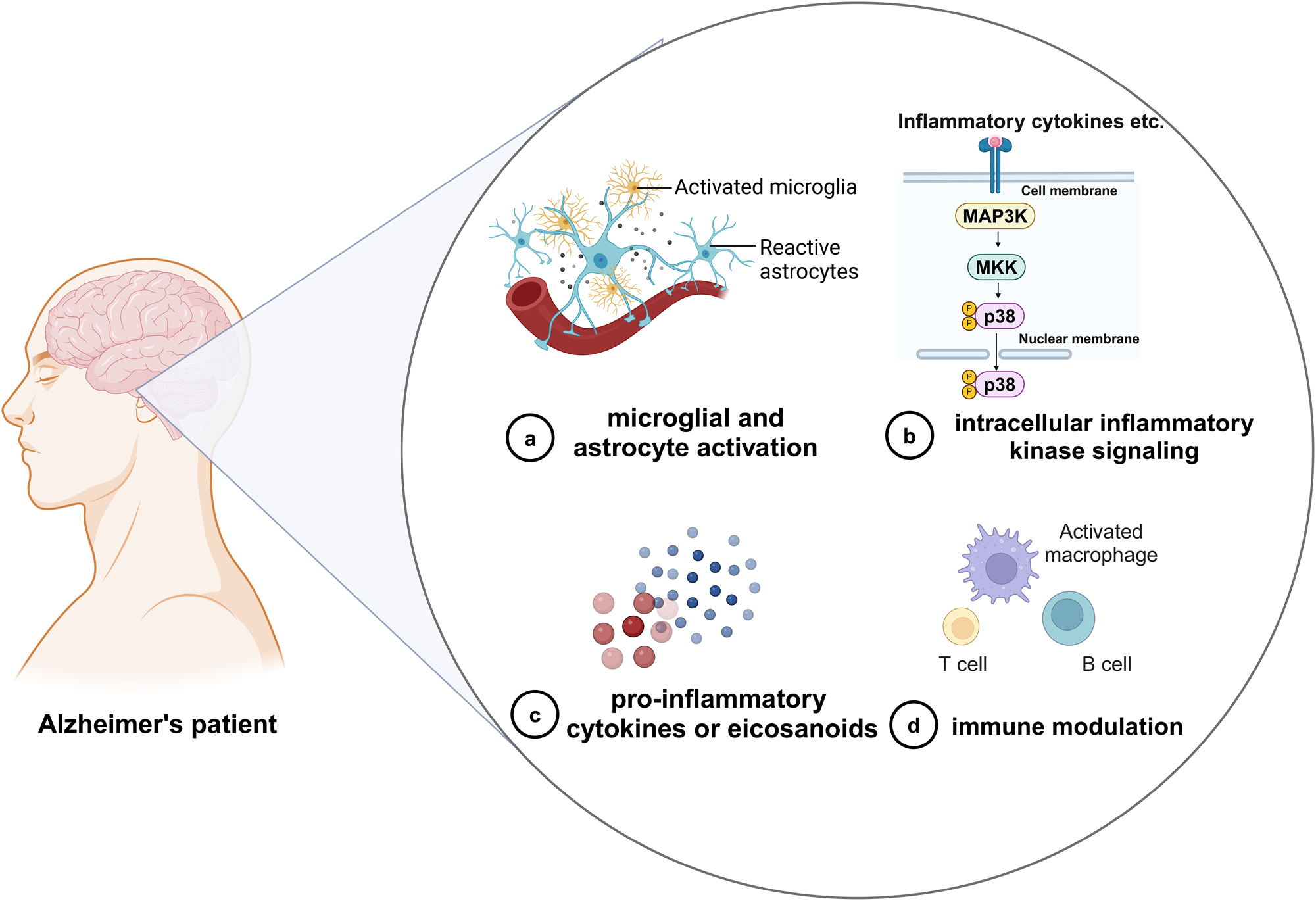

Clinical trials targeting neuroinflammation

The development of drugs for the treatment of AD is challenging. Early trials targeting Aβ and p-tau proteins failed to meet expectations. Recently, with the accumulation of knowledge regarding neuroinflammation, it has been discovered that the brains of patients with AD exhibit sustained inflammation. Consequently, several clinical trials targeting neuroinflammation have been conducted. However, clinical trials of drugs for the treatment of AD are still in the early stages of development. Current trials have therefore focused on four targets: (1) microglial and astrocyte activation, (2) intracellular inflammatory kinase signaling, (3) pro-inflammatory cytokines or eicosanoids, and (4) immune modulation (Table 2) (Figure 10). The treatment of neuroinflammation in AD represents a breakthrough. However, the inflammatory status of AD patients may change at different stages of the disease. Phenotypic transformations of microglia and astrocytes (protective or pro-inflammatory) suggest that indiscriminate use of anti-inflammatory drugs may harm rather than benefit patients with AD. One way to overcome this problem is to classify patients with AD based on changes in inflammatory markers and treat them accordingly. The success of this approach largely depends on our understanding of the mechanisms by which inflammation plays a role in AD progression.

Clinical trials of investigating the targeting of neuroinflammation in AD.

| Drug | Target/Mechanism | Sponsor | Phase | Status | CT identifier | Study population | Start date | Estimated end date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Drugs targeting microglia and astrocyte activation | ||||||||

| AL002 | TREM2: Membrane receptor that activates microglia in disease | Alector Inc | II | Recruiting | NCT05744401 | Early AD | January 2023 | December 2025 |

| TB006 | Humanized monoclonal antibody targeting galectin 3 | TrueBinding, Inc | I/II | Completed | NCT05074498 | Mild to severe AD | October 2021 | October 2022 |

| Edicotinib (JNJ-40346527) | CSF-1 receptor antagonist | University of Oxford | I | Unknown status | NCT04121208 | MCI | November 2020 | December 2021 |

| Sargramostim | Recombinant human GM-CSF, activate microglia | University of Colorado, Denver | II | Recruiting | NCT04902703 | Mild-to-moderate AD | June 2022 | July 2025 |

| Daratumumab | The human monoclonal antibody that targets CD38 | Marc L Gordon, MD | II | Completed | NCT04070378 | Mild to moderate AD | November 2019 | August 2023 |

|

|

||||||||

| Drugs targeting intracellular inflammatory kinase signaling | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| NE3107 | ERK/NF-κB inhibitor | BioVie Inc. | III | Completed | NCT04669028 | Mild to moderate probable AD | August 2021 | October 2023 |

| MW150 | Stress kinase inhibitor | Neurokine therapeutics | II | Not yet recruiting | NCT05194163 | Mild to moderate AD | May 2022 | November 2024 |

| Neflamapimod | p38 mitogen-activated serine/threonine protein kinase p38 MAPK selective inhibitor | EIP Pharma Inc | II | Completed | NCT03402659 | Mild AD | December 2017 | July 2019 |

| Baricitinib | Janus kinase inhibitor | Massachusetts general hospital | I/II | Recruiting | NCT05189106 | Cognitive disorder, MCI, AD | December 2022 | June 2025 |

|

|

||||||||

| Drugs targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines or eicosanoids | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Canakinumab (ACZ885) | IL-1β: a Secreted extracellular and cytosolic protein that regulates inflammation | Novartis Pharmaceuticals | II | Active | NCT04795466 | MCI or mild AD | October 2021 | March 2024 |

| XPro1595 | TNF inhibitor | Inmune Bio, Inc. | II | Recruiting | NCT05318976 | Early AD with biomarkers of inflammation | February 2022 | December 2024 |

| Salsalate | NSAIDs | Adam Boxer | I | Unknown status | NCT03277573 | Mild to moderate AD | July 2017 | December 2021 |

| ALZT-OP1 | NSAIDs | AZTherapies, Inc. | III | Completed | NCT02547818 | Early stage AD | September 2015 | November 2020 |

| Huperzine A | Reduce lymphocyte proliferation and the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines | NIA | II | Completed | NCT00083590 | AD | April 2004 | November 2007 |

|

|

||||||||

| Drugs targeting immune modulation | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylpurine-2,6-dione) | Favors autoimmunity treg and decreases cytokines needed for Th17 and Th1 | University hospital, lille | III | Recruiting | NCT04570085 | AD at beginning to moderate stages | March 2021 | November 2024 |

| Albumin and immunoglobulin | Inhibitor of T cell adhesion in vitro. Negatively correlated with Th17, positively correlated with treg | Instituto Grifols, S.A. | II/III | Completed | NCT01561053 | Probable mild to moderate AD | April 2012 | March 2018 |

| Nasal insulin | Increase treg | University of southern California | II/III | Completed | NCT01767909 | MCI or mild AD | January 2014 | December 2018 |

| Ladostigil | Reduce lymphocyte proliferation and the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines | Avraham Pharmaceuticals ltd | II | Completed | NCT01354691 | Mild to moderate AD | February 2011 | March 2013 |

| Dasatinib and quercetin | Immunosuppressive, inhibit Th17 | James L. Kirkland, MD, PhD | I/II | ENROLLING | NCT04785300 | MCI or AD | July 2022 | December 2024 |

| Masitinib | Inhibit mast cell and microglia/macrophage activity | AB science | III | Not yet recruiting | NCT05564169 | Mild to moderate AD | January 2024 | December 2026 |

| VT301 | Autologous regulatory T cells | VTBIO co. LTD | I | Unknown status | NCT05016427 | Mild to moderate AD | November 2020 | April 2022 |

| PrimeC | Anti-inflammatory | NeuroSense therapeutics ltd. | II | Recruiting | NCT06185543 | Mild to moderate AD | November 2023 | November 2025 |

| Resveratrol | Phenol antioxidant | ADCS | II | Completed | NCT01504854 | Probable AD | May 2012 | March 2014 |

| Simvastatin | Anti-inflammatory | NIA | III | Completed | NCT00053599 | Mild to moderate AD | December 2002 | October 2007 |

| IVIG | Anti-inflammatory | Sutter health | II | Completed | NCT01300728 | MCI | January 2011 | March 2020 |

-

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADCS, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study; CD38, Cluster of Differentiation 38; CSF-1, Colony Stimulating Factor-1; GM-CSF, Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor; ERK/NF-κB inhibitor, Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase/Nuclear Factor-kappa B inhibitor; IVIG, immunoglobulin; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NSAIDs, Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs; NIA, National Institute on Aging; TREM2, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; Th1, helper T-cell 1; Th17, helper T-cell 17; Treg, T regulatory cell; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor.

Clinical trials targeting neuroinflammation in AD. Clinical trials targeting neuroinflammation in AD can be divided into (a) microglial and astrocyte activation; (b) intracellular inflammatory kinase signaling; (c) pro-inflammatory cytokines or eicosanoids; and (d) immune modulation. AD, Alzheimer’s disease. Created with BioRender.com.

Conclusion and perspective

As research on AD has advanced, increasing evidence has highlighted the importance of the immune system in AD pathogenesis. The dysfunction of peripheral and central immune functions can exacerbate neuroinflammation and AD pathologies. Damage to the BBB, lymphatic system, and meningeal lymphatic drainage can also lead to immune dysregulation, which contributes to cognitive decline in patients with AD. Immunotherapy has shown great promise in the treatment of AD.

Recent studies have demonstrated immune abnormalities in both the central and peripheral nervous systems of patients with AD that are closely associated with the regulation of key pathological proteins. These abnormalities are potential therapeutic targets. Various candidate therapeutic approaches that target multicellular neuroinflammatory pathways at different stages of AD have shown promising efficacy in experimental models of AD. However, clinical validation of this method is currently lacking. Third, AD is a systemic disease that involves crosstalk between the central and peripheral immune cells. Monitoring and regulating these changes are key challenges for future research.

Considering all of the above, large-scale prospective clinical studies are required to validate the roles of the immune system in AD. The design and implementation of clinical trials, especially those that specifically target immune cells, should consider the disease stage and individual patient characteristics, such as genetic background. The dynamic monitoring of changes in inflammation-related biomarkers in patients and the timely adjustment of treatment plans are also essential for achieving optimal therapeutic outcomes. Although immune-related therapies for AD have shown efficacy, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the biology of immune cells in the brain, particularly peripheral immune cells. Furthermore, the mechanisms underlying the entry of peripheral immune cells into the CNS and their precise roles are not yet fully understood. Further understanding of the diverse functions of the immune system in AD, including the interactions between immune cells and other brain cell components is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies.

Funding source: the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals' Ascent Plan

Funding source: Beijing Brain Initiative from Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission

Award Identifier / Grant number: Z201100005520016

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 81870825, 82071194

Funding source: STI2030-Major Projects

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant No.2022ZD0211600, 2022ZD0211605

Funding source: Natural Science Foundation of Beijing Municipality

Award Identifier / Grant number: 7202061

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Xiaofeng Fu: Investigation, Visualization, Writing original draft. Huimin Cai, Shuiyue Quan, and Yinghao Xu: Writing-review & editing. Longfei Jia: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing-review & editing. All authors have read the final draft of the manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: No large language models, AI, or machine learning tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81870825 and 82071194), the Beijing Brain Initiative from the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Grant No. Z201100005520016), the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 7202061), the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (Grant No. 2022-2-2017), the STI2030-Major Projects (Grant No. 2022ZD0211600, 2022ZD0211605) and the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’ Ascent Plan.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Tanzi, RE, Bertram, L. Twenty years of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell 2005;120:545–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Krstic, D, Knuesel, I. Deciphering the mechanism underlying late-onset Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2013;9:25–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2012.236.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Huimin, C, Xiaofeng, F, Shuiyue, Q, Ziye, R, Changbiao, C, Longfei, J. Amyloid-β-targeted therapies for Alzheimer’s disease: currently and in the future. Ageing Neurodegener Dis 2023;3:13. https://doi.org/10.20517/and.2023.16.Search in Google Scholar

4. Cribbs, DH, Berchtold, NC, Perreau, V, Coleman, PD, Rogers, J, Tenner, AJ, et al.. Extensive innate immune gene activation accompanies brain aging, increasing vulnerability to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration: a microarray study. J Neuroinflammation 2012;9:179. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-9-179.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Guerreiro, R, Wojtas, A, Bras, J, Carrasquillo, M, Rogaeva, E, Majounie, E, et al.. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2013;368:117–27. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1211851.Search in Google Scholar

6. Zimmer, ER, Leuzy, A, Benedet, AL, Breitner, J, Gauthier, S, Rosa-Neto, P. Tracking neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: the role of positron emission tomography imaging. J Neuroinflammation 2014;11:120. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-11-120.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Colonna, M, Butovsky, O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Immunol 2017;35:441–68. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052358.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Nayak, D, Roth, TL, McGavern, DB. Microglia development and function. Annu Rev Immunol 2014;32:367–402. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120240.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Hansen, DV, Hanson, JE, Sheng, M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol 2018;217:459–72. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201709069.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Hong, S, Beja-Glasser, VF, Nfonoyim, BM, Frouin, A, Li, S, Ramakrishnan, S, et al.. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 2016;352:712–6. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad8373.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Jonsson, T, Stefansson, H, Steinberg, S, Jonsdottir, I, Jonsson, PV, Snaedal, J, et al.. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2013;368:107–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1211103.Search in Google Scholar

12. Hollingworth, P, Harold, D, Sims, R, Gerrish, A, Lambert, JC, Carrasquillo, MM, et al.. Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 2011;43:429–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.803.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Rogers, J, Luber-Narod, J, Styren, SD, Civin, WH. Expression of immune system-associated antigens by cells of the human central nervous system: relationship to the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 1988;9:339–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-4580(88)80079-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Tao, Q, Ang, TFA, DeCarli, C, Auerbach, SH, Devine, S, Stein, TD, et al.. Association of chronic low-grade inflammation with risk of alzheimer disease in ApoE4 carriers. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e183597. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3597.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Walker, KA, Gottesman, RF, Wu, A, Knopman, DS, Gross, AL, Mosley, THJr., et al.. Systemic inflammation during midlife and cognitive change over 20 years: the ARIC study. Neurology 2019;92:e1256–7. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000007094.Search in Google Scholar

16. Scali, C, Prosperi, C, Bracco, L, Piccini, C, Baronti, R, Ginestroni, A, et al.. Neutrophils CD11b and fibroblasts PGE(2) are elevated in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2002;23:523–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00346-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Medawar, PB. Immunity to homologous grafted skin; the fate of skin homografts transplanted to the brain, to subcutaneous tissue, and to the anterior chamber of the eye. Br J Exp Pathol 1948;29:58–69.Search in Google Scholar

18. Croese, T, Castellani, G, Schwartz, M. Immune cell compartmentalization for brain surveillance and protection. Nat Immunol 2021;22:1083–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-021-00994-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Dionisio-Santos, DA, Olschowka, JA, O’Banion, MK. Exploiting microglial and peripheral immune cell crosstalk to treat Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 2019;16:74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-019-1453-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. D’Errico, P, Ziegler-Waldkirch, S, Aires, V, Hoffmann, P, Mezo, C, Erny, D, et al.. Microglia contribute to the propagation of Abeta into unaffected brain tissue. Nat Neurosci 2022;25:20–5.10.1038/s41593-021-00951-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Kierdorf, K, Erny, D, Goldmann, T, Sander, V, Schulz, C, Perdiguero, EG, et al.. Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via Pu.1- and Irf8-dependent pathways. Nat Neurosci 2013;16:273–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3318.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Masuda, T, Tsuda, M, Yoshinaga, R, Tozaki-Saitoh, H, Ozato, K, Tamura, T, et al.. IRF8 is a critical transcription factor for transforming microglia into a reactive phenotype. Cell Rep 2012;1:334–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Crehan, H, Hardy, J, Pocock, J. Blockage of CR1 prevents activation of rodent microglia. Neurobiol Dis 2013;54:139–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2013.02.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Rogers, J, Li, R, Mastroeni, D, Grover, A, Leonard, B, Ahern, G, et al.. Peripheral clearance of amyloid beta peptide by complement C3-dependent adherence to erythrocytes. Neurobiol Aging 2006;27:1733–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.043.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Johansson, JU, Brubaker, WD, Javitz, H, Bergen, AW, Nishita, D, Trigunaite, A, et al.. Peripheral complement interactions with amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease: polymorphisms, structure, and function of complement receptor 1. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:1438–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Griciuc, A, Federico, AN, Natasan, J, Forte, AM, McGinty, D, Nguyen, H, et al.. Gene therapy for Alzheimer’s disease targeting CD33 reduces amyloid beta accumulation and neuroinflammation. Hum Mol Genet 2020;29:2920–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddaa179.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Wissfeld, J, Nozaki, I, Mathews, M, Raschka, T, Ebeling, C, Hornung, V, et al.. Deletion of Alzheimer’s disease-associated CD33 results in an inflammatory human microglia phenotype. Glia 2021;69:1393–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/glia.23968.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Aikawa, T, Ren, Y, Yamazaki, Y, Tachibana, M, Johnson, MR, Anderson, CT, et al.. ABCA7 haplodeficiency disturbs microglial immune responses in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019;116:23790–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908529116.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Fu, Y, Hsiao, JH, Paxinos, G, Halliday, GM, Kim, WS. ABCA7 mediates phagocytic clearance of amyloid-beta in the brain. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;54:569–84. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-160456.Search in Google Scholar

30. Lamartiniere, Y, Boucau, MC, Dehouck, L, Krohn, M, Pahnke, J, Candela, P, et al.. ABCA7 downregulation modifies cellular cholesterol homeostasis and decreases amyloid-beta peptide efflux in an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier. J Alzheimers Dis 2018;64:1195–211. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-170883.Search in Google Scholar PubMed