Abstract

The surfactant-free synthesis of β-phase germanium dioxide nanoparticles in ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol and benzyl alcohol has been reported. Characterisation of the hexagonal β-GeO2 crystals, which involves powder X-ray diffraction, nitrogen adsorption measurements (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller method), dynamic light scattering measurements, IR spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis has been presented. Synthesis of β-GeO2 under ambient conditions in benzyl alcohol results in nanoparticles with diameters below 20 nm, whereas the synthesis under inert conditions in benzyl alcohol at reflux (205°C) gives larger nanoparticles. In ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol, agglomerates with particle sizes above 100 nm are observed under inert atmosphere conditions at room temperature.

Introduction

In the last few years, a significant progress has been reported on the synthesis of GeO2 materials (Adachi et al., 2005; Zou et al., 2005; Armelao et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2012; Seng et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). Especially, small particles show interesting features such as photoluminescence under visible light irradiation, high refractive index as compared to that of silica glasses and optical transparency in between 280 and 5000 nm (Kim et al., 2007; Chiu and Huang, 2009; Liu et al., 2010). It is of scientific as well as commercial interest to prepare GeO2 particles with variation in crystal structure, in morphology and in size from below 100 nm up to several hundreds of nanometres. For example, size control was previously achieved by hydrolysis of GeCl4 or Ge(OEt)4 in micelles and/or reverse micelle systems (Wu et al., 2006; Chiu and Huang, 2009; Zou et al., 2011). A major drawback of these synthesis routes is the need for several different reactants often including special surfactants and precise adjustment of the synthesis conditions. For instance, Chiu and Huang reported the synthesis of hexagonal GeO2 particles varying in size from around 100 to 300 nm depending on the reaction time by the use of a mixture of six reactants [precursor: Ge(OEt)4; oil phase: cyclohexane; surfactant: 4-octylphenol polyethoxylate; co-surfactant: n-hexanol; HCl; and water] (Chiu and Huang, 2009). However, simple surfactant-free non-aqueous synthesis routes for a great number of nanosized metal oxides were reported by Niederberger et al. using one single metal containing precursor and simple organic solvents such as benzyl alcohol, n-butyl ether or ethanol (Niederberger et al., 2002; Pinna et al., 2004; Ba et al., 2005; Pinna and Niederberger, 2008). Additionally, the synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles by surfactant-free non-hydrolytic sol-gel routes starting from the corresponding metal chlorides were reported by Mutin and his coworkers (Aboulaich et al., 2009, 2010, 2011). Nevertheless, reports on the synthesis of GeO2 nanoparticles by a simple surfactant-free synthesis route starting from GeCl4 are still lacking. We are currently studying the process of twin polymerisation, which has been reported recently for silicon-containing compounds such as 2,2′-spirobi[4H-1,3,2-benzodioxasiline] (see Scheme 1). This is a convenient method to form nanostructured organic-inorganic hybrid materials by a one-step synthesis (Grund et al., 2007; Spange et al., 2009; Löschner et al., 2012). Additionally, this method also gives access to metal oxide nanoparticles (Mehner et al., 2008; Böttger-Hiller et al., 2009).

![Scheme 1 Twin polymerisation of 2,2′-spirobi[4H-1,3,2-benzodioxasiline] resulting in nanostructured, interpenetrating SiO2/phenolic resin networks (Spange et al., 2009).](/document/doi/10.1515/mgmc-2013-0038/asset/graphic/mgmc-2013-0038_scheme1.jpg)

Twin polymerisation of 2,2′-spirobi[4H-1,3,2-benzodioxasiline] resulting in nanostructured, interpenetrating SiO2/phenolic resin networks (Spange et al., 2009).

However, our attempts to synthesise the corresponding germanium-containing compounds, which are structurally related to 2,2′-spirobi[4H-1,3,2-benzodioxasiline], starting from germanium alkoxides and GeCl4 failed so far. Benzyl alcohol derivatives that were tested as reagents gave GeO2 and partial polymerisation of the benzyl alcohol derivatives after addtion of the latter germanium containing reagents. In addition, the formation of the respective dibenzyl ether derivative as a by-product was observed. These observations prompted us to study the reactivity of benzyl alcohols in the presence of GeCl4 in more detail. We present here the preparation of β-GeO2 particles in ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol under inert conditions as well as in benzyl alcohol under inert and ambient conditions starting from GeCl4. Variation of the mean particle size from tenths up to hundreds of nanometres depends on both, the benzyl alcohol used and the synthesis conditions.

Results and discussion

Germanium dioxide was synthesised starting from GeCl4 in benzyl alcohol by the following different synthetic protocols: (i) GeCl4 was stirred in ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol under inert conditions at room temperature for 22 h (sample A); (ii) GeCl4 was dissolved and stirred in benzyl alcohol under inert conditions at reflux for 24 h (sample B); (iii) GeCl4 was added to benzyl alcohol and stirred under ambient conditions at 40°C for 24 h (sample C). All these methods gave β-GeO2, which was isolated by centrifugation followed by washing with tetrahydrofuran (THF) and ethanol, respectively. The GeO2 particles were characterised by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), nitrogen physisorption [Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method], dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements, infrared (IR) spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis. The PXRD patterns of these particles are given in Figure 1.

X-ray powder diffraction pattern of the as-prepared β-GeO2 particles. The red, blue and black curves depict the X-ray powder diffraction patterns of the GeO2 particles of samples A, B and C. The violet bars display the standard diffraction pattern of hexagonal β-GeO2 (ICDD no. C00-036-1463).

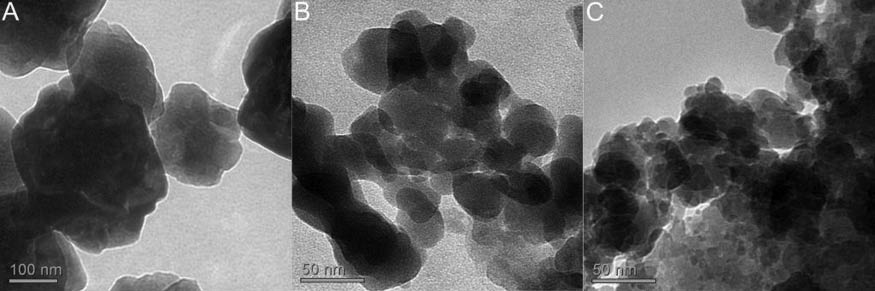

The PXRD data confirm the formation of crystalline β-GeO2 particles for all samples. Determination of the particle sizes by applying the Scherrer equation based on the (101) reflection gave particle sizes of (43±4) (sample A), (27±2) (sample B) and (9±1) nm (sample C) for the primary particles. Nitrogen adsorption measurements gave BET surface areas of 9, 10 and 146 m2/g for samples A, B and C, respectively. The corresponding TEM images of the β-GeO2 particles (samples A–C) are shown in Figure 2.

TEM images for samples A–C.

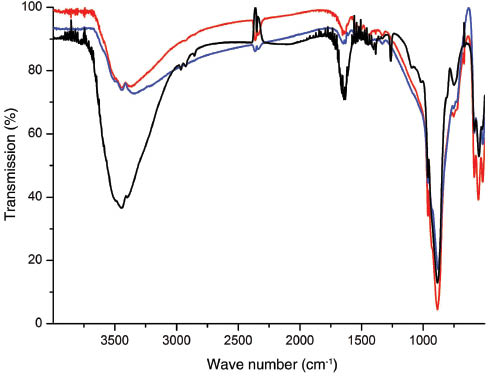

The TEM image of the β-GeO2, which was synthesised in ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol (sample A), shows that the particles are larger than 100 nm, which is significantly larger than the size of the primary particles as determined from the PXRD data and they vary in size. This is ascribed to agglomeration of the crystalline nanoparticles and the presence of some amorphous material. A lower extent of agglomeration and smaller particles are obtained by synthesising GeO2 in benzyl alcohol as demonstrated by the TEM images of samples B and C. A noteworthy observation is that GeO2 particles isolated after their synthesis in benzyl alcohol under inert conditions exhibit sizes in between 30 nm and several tens of nanometres (sample B), whereas the synthesis under ambient conditions gives GeO2 particles with diameters mainly below 20 nm (sample C). The deviations in primary particle sizes as obtained from the PXRD data result from agglomeration as observed for sample A, but to a lower extent. The EDX spectra support the formation of GeO2 without any chlorine impurities. Absence of the latter was also verified by the lack of any precipitation after addition of a 0.2 m AgNO3 solution to the filtrate of an aqueous suspension of the particles that was heated at reflux for 1 h. However, small amounts of carbon and hydrogen were detected by CH analysis for all samples in the range from 0.46% to 1.58% and from 0.13% to 0.33% for carbon and hydrogen, respectively, which might be explained by a small amount of residual organic material attached to the surface of the particles. The hydrodynamic radii as determined by DLS measurements are 535, 482 and 179 nm in THF and 360, 198 and 536 nm in toluene for samples A, B and C, respectively. These hydrodynamic radii are in agreement with the agglomeration of the particles as observed in the TEM images of the samples A–C. However, the differences in the hydrodynamic radii of each sample in different solvents indicate specific agglomeration behaviour of the particles with respect to the polarities of the employed solvents. Samples A and B exhibit less agglomeration in toluene, whereas sample C shows a larger hydrodynamic radius in toluene as compared to its value determined in THF. The IR spectroscopy reveals a significantly higher extent of OH groups at the surface of the particles for sample C, which is in accordance with the reverse behaviour of samples A and B as determined by the DLS measurements. It is noteworthy that the IR spectra of the samples A–C exhibit the absorption band maxima (517, 552, 586, 728, 753, 882, 890, 931 and 961 cm-1) which were recently reported for the hexagonal β-modification of GeO2 (Figure 3). The characteristic three absorption band maxima at 517, 552 and 586 cm-1 are indicative of the hexagonal structure. The absorption band maximum at 1642 cm-1 indicates the presence of water at the surface of the particles (Atuchin et al., 2009). The IR spectra reveal the presence of minor amounts of adsorbed organic material, which is in accordance with the low carbon content (C<1.6%) as determined by the CH analysis.

IR spectra of the as-prepared GeO2 particles; samples A (red), B (blue) and C (black).

In Table 1, a summary of the primary particle sizes as determined by PXRD and the results of the nitrogen adsorption measurements (BET method), DLS measurements and CH analysis of all samples are given.

Analytical data for the as-synthesised GeO2 particles (samples A–C).

| Sample A | Sample B | Sample C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary particle sizea | 43±4 nm | 27±2 nm | 9±1 nm |

| BET surfaceb | 9 g/m2 | 10 g/m2 | 146 g/m2 |

| Hydrodynamic radius: | |||

| In THF | 535 nm | 482 nm | 179 nm |

| In toluene | 360 nm | 198 nm | 536 nm |

| CH analysis (C/H%) | 1.06/0.24% | 0.46/0.13% | 1.58/0.33% |

aDetermined by the Scherrer equation (K=1) using the data of the (101) reflection of the X-ray powder diffraction pattern; bSingle point BET analysis p/p0=0.150.

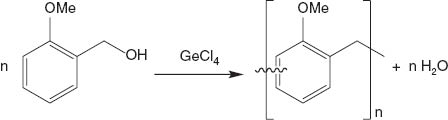

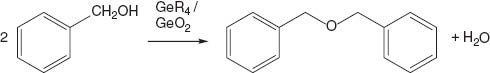

The formation of GeO2 particles in ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol (sample A) was observed under inert conditions at room temperature. The NMR spectroscopic analysis of the reaction mixture confirmed the presence of different soluble ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol derivatives, which most likely are intermediate species in the formation process of an ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol resin. It is to be noted that the as-prepared β-GeO2 (sample A) exhibits a pale pink colour, which is typical for benzyl alcohol resins obtained by cationically induced polymerisation. Thus we propose that the formation of GeO2 particles in ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol can be explained by a Lewis acid, here GeCl4, initiated polymerisation (oligomerisation) of the ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol, which in situ generates water (Scheme 2). Consecutively, the water reacts with GeCl4 to give GeO2 particles.

Reaction scheme to show the formation of water caused by Lewis acid straight composition initiated polymerisation (oligomerisation) of ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol under an inert atmosphere.

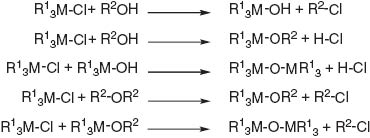

The formation of GeO2 particles in benzyl alcohol under inert conditions (sample B) was observed by stirring the mixture under reflux. The resulting mixture after removal of the GeO2 particles consisted of 29.8 mol% benzyl alcohol, 12.6 mol% benzyl chloride, 38.7 mol% dibenzyl ether and 18.9 mol% water, which was determined by NMR spectroscopic analysis. It is noteworthy that the formation of benzyl chloride was quantitative with regard to the amount of GeCl4 added. The quantitative formation of benzyl chloride indicates formation of GeO2 particles by an alkyl chloride elimination reaction mechanism in accordance with the results reviewed by Debecker and Mutin (2012) for the synthesis of a variety of metal oxides (Scheme 3).

Summary of the proposed reactions of metal(IV) halides in the non-hydrolytic sol-gel process as suggested by Debecker and Mutin (2012); R1=Cl, OH and/or benzyl alcoholate; R2=benzyl group.

However, the presence of dibenzyl ether (in a yield of 29% with regard to the amount of benzyl alcohol used for the synthesis) and water in the resulting reaction mixture indicates condensation reactions to take place as well. These condensation reactions may be catalyzed by GeCl4, other in situ generated germanium species or even by GeO2 particles as shown in Scheme 4.

Reaction scheme showing the formation of dibenzyl ether under inert conditions; R=Cl, OH and/or benzyl alcoholate intermediates.

The eliminated water might additionally give hydrolysis of germanium-containing species that finally results in GeO2. It is to be noted that the formation of water and consecutively the formation of GeO2 may also be explained by condensation of germanoles generated by the alkyl chloride elimination reaction (see Scheme 3). However, the quantitative formation of benzyl chloride indicates that the alkyl chloride reaction mechanism is the predominant reaction in benzyl alcohol under inert conditions. Although no formation of GeO2 was observed under inert conditions at lower temperature, the NMR spectroscopic analysis of a reaction mixture consisting of benzyl alcohol and GeCl4 in a molar ratio of 42:1 that was stirred under argon atmosphere at 40°C for 2 weeks revealed the formation of benzyl chloride (4.6 mol% in the mixture), some dibenzyl ether (1.4 mol% in the mixture) and germanium alkoxide species. The reaction of GeCl4 with dibenzyl ether to give benzyl chloride (see Scheme 3) was also observed in a separate experiment. Here, GeCl4 was added to pure dibenzyl ether in the same ratio as compared to the synthesis of sample B. Formation of benzyl chloride was proven by NMR spectroscopic analysis of the mixture after stirring at 206°C for 24 h, whereas this was not observed at room temperature. These observations support the hypothesis of an alkyl chloride reaction mechanism for GeO2 in benzyl alcohol. By contrast, the formation of GeO2 in benzyl alcohol under ambient conditions (sample C) was already observed by stirring the mixture at 40°C for 24 h (yield was 9%). Further stirring of the mixture at 40°C at ambient conditions gave an additional portion of β-GeO2 (yield was 37%). Therefore, we conclude that the formation of GeO2 particles in benzyl alcohol under ambient conditions results from hydrolysis and that benzyl alcohol acts as a solvent and a surfactant in the formation process of the nanoparticles.

Conclusions

Germanium(IV) oxide nanoparticles were synthesised in ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol under inert conditions and in benzyl alcohol under inert and under ambient conditions, respectively, starting from GeCl4 without addition of any further reactant. The as-prepared β-GeO2 particles were characterised by PXRD, nitrogen adsorption measurements (BET method), DLS measurements, IR spectroscopy, TEM and EDX analysis. The synthesis in ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol under inert conditions gave GeO2 particles with sizes >100 nm. It is proposed that Lewis acid initiated partial polymerisation of ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol gave water, which results in the formation of β-GeO2 upon hydrolysis. Nanoparticles below 100 nm in size were obtained in benzyl alcohol under inert conditions. Their formation is assumed to be a result of an alkyl chloride elimination reaction mechanism. The formation of β-GeO2 starting from benzyl alcohol under ambient conditions is a result of slow diffusion of moisture into the reaction mixture and gave the smallest GeO2 nanoparticles that exhibit sizes below 20 nm. The results demonstrate that hydrolysis must be considered as an important side reaction, even in a so-called non-hydrolytic processes, if water might be formed as a side product or the presence of moisture is not fully excluded.

Experimental

General

1H and 13C{1H}-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) ‘Avance III 500’ spectrometer at ambient temperature. CH analysis was carried out with a ‘vario MICRO’ from Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH (Hanau, Germany). The PXRD patterns were collected using a STOE-STAD IP diffractometer from STOE (STOE and Cie GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany)with Cu-Kα radiation (40 kV, 40 mA) and a Ge(111) monochromator. The crystallite size was estimated using the Scherrer equation:  where τ is the volume weighted crystallite size, K is the Scherrer constant here taken as 1.0, λ is the X-ray wavelength, θ is the Bragg’s angle (in rad) and β is the full width of the diffraction line at half of the maximum intensity (FWHM, background subtracted). The FWHM is corrected for instrumental broadening using a LaB6 standard (SRM 660) purchased from NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The value of β was corrected from (

where τ is the volume weighted crystallite size, K is the Scherrer constant here taken as 1.0, λ is the X-ray wavelength, θ is the Bragg’s angle (in rad) and β is the full width of the diffraction line at half of the maximum intensity (FWHM, background subtracted). The FWHM is corrected for instrumental broadening using a LaB6 standard (SRM 660) purchased from NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The value of β was corrected from ( and

and  are the FWHMs of measured and standard profiles):

are the FWHMs of measured and standard profiles):

The DLS measurements were performed on a Modell 802 from Viscotek™ (Malvern Instruments GmbH, Herrenberg, Germany) using a laser light emitting diode at 830 nm. The THF and toluene suspensions of the particles obtained by ultrasonic treatment were given in a quartz glass cuvette for DLS measurements. Infrared spectra were recorded with a Nicolet IR 200 spectrometer from Thermo Scientific (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) in a KBr matrix. Transmission electron micrographs and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy experiments were obtained by a 200 kV-high resolution transmission electron microscope [HRTEM, CM 20 FEG, Co. Philips (FEI Europe, Europe NanoPort, Eindhoven, The Netherlands)] with an imaging energy filter from Gatan (GIF). Specific surface analyses were performed with nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K) using a Quantachrome Autosorb IQ2 (Quantachrome, Odelzhausen, Germany), which were evaluated by the BET method using p/p0 ratio of 0.150.

Syntheses

Reactions using ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol were performed in an inert atmosphere (argon) glovebox. Reactions using benzyl alcohol were performed in an inert atmosphere (argon) glovebox as well as under ambient conditions to allow water diffusion into the reaction mixture. Solvents were purified and dried by applying standard techniques. Benzyl alcohol and ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol were purchased from Merck Schuchardt OHG (Hohenbrunn, Germany) and Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA), respectively. Benzyl alcohol was used without any purification for the synthesis under ambient conditions (sample C). Ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol and benzyl alcohol were dried over molecular sieves for 3 weeks before using them for the syntheses under inert conditions. GeCl4 was purchased from ABCR GmbH & Co. KG (Karlsruhe, Germany) and used without further purification.

Synthesis of GeO2 in ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol – sample A

GeCl4 (529.4 mg, 2.47 mmol) was added to ortho-methoxy benzyl alcohol (12.79 mL, 103.7 mmol) and the mixture was stirred under an inert atmosphere at room temperature for 22 h. The suspension was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min for separating the pale pink GeO2 particles, which were then purified by centrifugation (at 3000 rpm for 15 min) of a suspension of the particles in THF (5 mL) and in ethanol (5 mL) two times each, respectively, to quantitatively give pale pink GeO2. The CH analysis [%] found for GeO2: C 1.06 and H 0.24. Both PXRD and EDX analyses proved the formation of GeO2.

Synthesis of GeO2 in benzyl alcohol under inert conditions – sample B

GeCl4 (942.0 mg, 4.39 mmol) was added to benzyl alcohol (20.00 mL, 192.3 mmol) and the mixture was stirred under an inert atmosphere at reflux for 24 h. The pale yellow suspension was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to separate the GeO2 particles, which were then suspended and purified by centrifugation (at 3000 rpm for 10 min) in THF (5 mL) and in ethanol (5 mL) two times each, respectively, to quantitatively give colourless GeO2. The CH analysis [%] found for GeO2: C 0.46 and H 0.13. Both PXRD and EDX analyses proved the formation of GeO2.

Synthesis of GeO2 in benzyl alcohol under ambient conditions – sample C

GeCl4 (713.8 mg, 3.33 mmol) was added to benzyl alcohol (14.54 mL, 139.8 mmol) at 40°C. The mixture was stirred at 40°C under ambient conditions for 24 h. The colourless suspension was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to separate the GeO2 particles, which were then suspended and purified by centrifugation (at 3000 rpm for 10 min) in THF (5 mL) and in ethanol (5 mL) two times each, respectively. Additional stirring of the transparent, colourless, overlaying liquid at 40°C at ambient conditions for another 18 h gave further fractions of colourless GeO2. Yield: 56% (all fractions); the CH analysis [%] found for GeO2: C 1.58 and H 0.33. Both PXRD and EDX analyses proved the formation of GeO2.

We gratefully acknowledge financial support by the DFG Forschergruppe 1497 ‘organic and inorganic nanocomposites through twin polymerisation’ and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie for a fellowship (P. Kitschke).

References

Aboulaich, A.; Lorret, O.; Boury, B.; Mutin, P. H. Surfactant-free organo-soluble silica-titania and silica nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 2577–2579.Suche in Google Scholar

Aboulaich, A.; Boury, B.; Mutin, P. H. Reactive and organosoluble anatase nanoparticles by a surfactant-free nonhydrolytic synthesis. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 4519–4521.Suche in Google Scholar

Aboulaich, A.; Boury, B.; Mutin, P. H. Reactive and organosoluble SnO2 nanoparticles by a surfactant-free non-hydrolytic sol-gel route. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 3644–3649. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ejic.201100391/abstract.10.1002/ejic.201100391Suche in Google Scholar

Adachi, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Sago, K.; Murata, Y.; Nishikawa, Y. Formation of GeO2 nanosheets using water thin layers in lamellar phase as a confined reaction field – in situ measurement of SAXS by synchrotron radiation. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2005, 2381–2383. http://pubs.rsc.org/en/Content/ArticleLanding/2005/CC/b419017c#!divAbstract.10.1039/b419017cSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Armelao, L.; Heigl, F.; Kim, P.-S. G.; Rosenberg, R. A.; Regier, T. Z.; Sham, T.-K. Visible emission from GeO2 nanowires: site-specific insights via x-ray excited optical luminescence. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 14163–14169.Suche in Google Scholar

Atuchin, V. V.; Gavrilova, T. A.; Gromilov, S. A.; Kostrovsky, V. G.; Pokrovsky, L. D.; Troitskaia, I. B.; Vemuri, R. S.; Carbajal-Franco, G.; Ramana, C. V. Low-temperature chemical synthesis and microstructure analysis of GeO2 crystals with alpha-quartz structure. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 1829–1832.Suche in Google Scholar

Ba, J. H.; Polleux, J.; Antonietti, M.; Niederberger, M. Non-aqueous synthesis of tin oxide nanocrystals and their assembly into ordered porous mesostructures. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 2509–2512.Suche in Google Scholar

Böttger-Hiller, F.; Lungwitz, R.; Seifert, A.; Hietschold, M.; Schlesinger, M.; Mehring, M.; Spange, S. Nanoscale tungsten trioxide synthesized by in situ twin polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8878–8881.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, G.; Chen, B.; Liu, T.; Mei, Y.; Ren, H.; Bi, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhang, L. The synthesis and characterization of germanium oxide aerogel. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2012, 358, 3322–3326.Suche in Google Scholar

Chiu, Y.-W.; Huang, M. H., Formation of hexabranched GeO2 nanoparticles via a reverse micelle system. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 6056–6060.Suche in Google Scholar

Debecker, D. P.; Mutin, P. H. Non-hydrolytic sol-gel routes to heterogeneous catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3624–3650.Suche in Google Scholar

Grund, S.; Kempe, P.; Baumann, G.; Seifert, A.; Spange, S. Nanocomposites prepared by twin polymerization of a single-source monomer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 628–632.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, H. W.; Shim, S. H.; Lee, J. W. Cone-shaped structures of GeO2 fabricated by a thermal evaporation process. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 253, 7207–7210.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Q.-J.; Liu, Z.-T.; Feng, L.-P.; Tian, H. First-principles study of structural, elastic, electronic and optical properties of rutile GeO2 and alpha-quartz GeO2. Solid State Sci. 2010, 12, 1748–1755.Suche in Google Scholar

Löschner, T.; Mehner, A.; Grund, S.; Seifert, A.; Pohlers, A.; Lange, A.; Cox, G.; Hahnle, H. J.; Spange, S. A modular approach for the synthesis of nanostructured hybrid materials with tailored properties: the simultaneous twin polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3258–3261.Suche in Google Scholar

Mehner, A.; Rüffer, T.; Lang, H.; Pohlers, A.; Hoyer, W.; Spange, S. Synthesis of nanosized TiO2 by cationic polymerization of (mu(4)-oxido)-hexakis(mu-furfuryloxo)-octakis(furfuryloxo)-tetra-titanium. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 4113–4117.Suche in Google Scholar

Niederberger, M.; Bartl, M. H.; Stucky, G. D. Benzyl alcohol and titanium tetrachloride – a versatile reaction system for the nonaqueous and low-temperature preparation of crystalline and luminescent titania nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 4364–4370.Suche in Google Scholar

Pinna, N.; Niederberger, M. Surfactant-free nonaqueous synthesis of metal oxide nanostructures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5292–5304.Suche in Google Scholar

Pinna, N.; Neri, G.; Antonietti, M.; Niederberger, M. Nonaqueous synthesis of nanocrystalline semiconducting metal oxides for gas sensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4345–4349.Suche in Google Scholar

Seng, K. H.; Park, M. H.; Guo, Z. P.; Liu, H. K.; Cho, J. Catalytic role of Ge in highly reversible GeO2/Ge/C nanocomposite anode material for lithium batteries. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 1230–1236.Suche in Google Scholar

Spange, S.; Kempe, P.; Seifert, A.; Auer, A. A.; Ecorchard, P.; Lang, H.; Falke, M.; Hietschold, M.; Pohlers, A.; Hoyer, W.; et al. Nanocomposites with structure domains of 0.5 to 3 nm by polymerization of silicon spiro compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8254–8258.Suche in Google Scholar

Wu, H. P.; Liu, J. F.; Ge, M. Y.; Niu, L.; Zeng, Y. W.; Wang, Y. W.; Lv, G. L.; Wang, L. N.; Zhang, G. Q.; Jiang, J. Z. Preparation of monodisperse GeO2 nanocubes in a reverse micelle system. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 1817–1820.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, L.; Chen, G.; Chen, B.; Liu, T.; Mei, Y.; Luo, X. Monolithic germanium oxide aerogel with the building block of nano-crystals. Mater. Lett. 2013, 104, 41–43.Suche in Google Scholar

Zou, X. D.; Conradsson, T.; Klingstedt, M.; Dadachov, M. S.; O’Keeffe, M. A mesoporous germanium oxide with crystalline pore walls and its chiral derivative. Nature 2005, 437, 716–719.Suche in Google Scholar

Zou, X.; Liu, B.; Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Wu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Sui, Y.; Li, D.; Zou, B.; et al. One-step synthesis, growth mechanism and photoluminescence properties of hollow GeO2 walnuts. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 979–984.Suche in Google Scholar

©2013 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Review

- Structural characterization of heterometallic platinum complexes with non-transition metals. Part V: Heterooligo- and heteropolynuclear complexes

- Research Articles

- {Sn10Si(SiMe3)2[Si(SiMe3)3]4}2-: cluster enlargement via degradation of labile ligands

- Unusual reaction pathways of gallium(III) silylamide complexes

- Molecular structures of pyridinethiolato complexes of Sn(II), Sn(IV), Ge(IV), and Si(IV)

- Arylphosphonic acid esters as bridging ligands in coordination polymers of bismuth

- Synthesis of germanium dioxide nanoparticles in benzyl alcohols – a comparison

- X-ray crystal structures of [(Cy2NH2)]3[C6H3(CO2)3]·4H2O and [i-Bu2NH2][(Me3 SnO2C)2C6H3CO2]

- Crystal and molecular structure of bis(di-n-propylammonium) dioxalatodiphenylstannate, [n-Pr2NH2]2[(C2O4)2SnPh2]

- Short Communication

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a dimeric N,N-dimethylformamide solvate of isobutyltin(IV) dichloride hydroxide, [iBuSnCl2(OH)(DMF)]2

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Review

- Structural characterization of heterometallic platinum complexes with non-transition metals. Part V: Heterooligo- and heteropolynuclear complexes

- Research Articles

- {Sn10Si(SiMe3)2[Si(SiMe3)3]4}2-: cluster enlargement via degradation of labile ligands

- Unusual reaction pathways of gallium(III) silylamide complexes

- Molecular structures of pyridinethiolato complexes of Sn(II), Sn(IV), Ge(IV), and Si(IV)

- Arylphosphonic acid esters as bridging ligands in coordination polymers of bismuth

- Synthesis of germanium dioxide nanoparticles in benzyl alcohols – a comparison

- X-ray crystal structures of [(Cy2NH2)]3[C6H3(CO2)3]·4H2O and [i-Bu2NH2][(Me3 SnO2C)2C6H3CO2]

- Crystal and molecular structure of bis(di-n-propylammonium) dioxalatodiphenylstannate, [n-Pr2NH2]2[(C2O4)2SnPh2]

- Short Communication

- Synthesis and structural characterization of a dimeric N,N-dimethylformamide solvate of isobutyltin(IV) dichloride hydroxide, [iBuSnCl2(OH)(DMF)]2