Abstract

This essay demonstrates the use of multimodal (inter)action (MIA) analysis to examine the role of emotions in heritage language practice in transnational immigrant families between children and grandparents through digital communication media. The research uses Norris’s MIA framework and multimodal analytical tools to examine a video conversation between a grandmother residing in Bangladesh and her grandchild in Australia. Our study uncovers an intricate interplay of semiotic resources in digital interaction that reflects empathy and a strong emotional bond between the transnational grandparent and grandchild, where family bonding serves as the primary motivator of the conversation. While heritage language practice is visible, it plays a secondary role. We show how MIA can be used to capture the full spectrum of communication in an online video interaction, including the emotional dimensions often overlooked by traditional qualitative methods. Like other MIA studies, we introduce interview data into the analyses to provide a comprehensive understanding of the context of the video call. While our paper demonstrates the utility of MIA in sociolinguistics, it has implications for educators and families, emphasising the need for regular, emotionally engaging digital interactions to support heritage language maintenance and emotional well-being.

1 Introduction

Immigrants often face challenges in maintaining their heritage language in host countries, where the dominant or host country language prevails (Wang and Dovchin 2022). Historically, there has been limited engagement with multimodal discourse analysis (MDA) in the heritage language maintenance literature. This is because most heritage language maintenance was through face-to-face interactions (f2f) between people living in the same household (Chowdhury and Rojas-Lizana 2020; Hollebeke et al. 2020). However, with the rise of multilingual, transnational migrant families (Blommaert 2010), digital communication media has emerged as a crucial tool for transnational families, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hatoss 2023), to maintain family ties and communication, leading to the formation of what Taipale (2019) has termed a “digital family” (14).

The transformation of the traditional family into a transnational digital family has meant that digitally transnational families, who seek intimacy and communication with their transnational relatives, do not have to rely on few and far between physical visits across nations or continents to meet each other (Bose et al. 2023). Indeed, seeking intimacy and emotional bonding have been identified as one of the key motivators of digital communication among transnational families (Bose et al. 2024; Said 2021).

Importantly, emotions play an essential part in heritage language maintenance among children in immigrant family contexts (Curdt-Christiansen and Huang 2020; Sevinç and Mirvahedi 2023). This paper explores the role of emotions in digital communications during heritage language maintenance using MDA. The research gap that motivates this exploration is described next in the context of existing literature on this topic.

2 Literature review

Digitally networked multimodal communications involving text, audio, emojis and especially video allow special affordances with regard to the expression and transmission of emotions during digital communication (Said 2021; Sevinç and Mirvahedi 2023). Multimodal communications, primarily through the use of video, can facilitate a high degree of social presence (Cui et al. 2013), leading to more open and intense emotional exchanges (Mehrabian and Ferris 1967) than traditional modes of communication. For instance, even in studies that do not specifically seek to engage emotions in multimodal platforms, multimodal elements like gestures and facial expressions have been found to support heritage language maintenance among immigrant families by creating interactive environments (Zhao 2019).

Sociolinguists have long acknowledged the significant role of emotions in heritage languages. Even before the rise of digital media and video communications, researchers highlighted how using heritage languages could evoke strong emotional responses and foster deeper intimacy within family settings (Curdt-Christiansen and Huang 2020; Lexander and Androutsopoulos 2023). This is particularly evident for immigrant families living in English-dominant societies, where heritage languages are often seen as the language of intimate and personal communication (Dewaele 2010). Yet, studies on emotions in such communications have, for instance, analysed emojis (Curdt-Christiansen and Iwaniec 2023) or text (King-O’Rian 2015), offering the opportunity for a deeper exploration of video data on heritage language and emotions through methods appropriate for such data. The “complex emotions” (Schwartz and Verschik 2013: 6) and heritage language practice can thus be comprehensively assessed through multimodal analysis methods (Norris 2013). MDA realised through a framework such as multimodal (inter)action analysis (MIA) proposed by Norris (2013) for unpacking the various modes (text, speech, gestures, emojis) can help gain a deeper understanding of emotions and heritage language maintenance using digital media.

Thus, for instance, Norris’s (2016) study using the MIA demonstrates that during Skype interactions between family members in New Zealand, the focus shifts from the medium (Skype) to the conversation itself, making it more natural over time. Another detailed study using MIA by Geenen (2017) explores how encouraging children to show objects during video calls can help maintain their attention, support their self-expression, and strengthen family bonds by engaging them on topics of immediate interest. Our study seeks to extend this methodological approach (MIA) into the analysis of emotions and heritage language practice during such digital conversations.

With the above strengths of MDA in mind, this essay provides a demonstration of MDA using Norris’s (Norris 2004, 2019) MIA to unpack emotions in multimodal interactions between children and their transnational family members during heritage language practice. Through a multimodal analysis of data from one Bengali immigrant family in Australia, we seek to address the following research question:

How can multimodal (inter)action analysis be used to understand emotional expression and heritage language practice in a transnational immigrant family?

In the sections that follow, we illustrate the use of Norris’s (2004) MIA to understand emotions and heritage language in an episode of digital communication between a child and a transnational grandparent. Note that in the context of this paper, transnational family member implies someone who is not living in the country where the focal family or child, who are the subjects of the essay, reside. Thus, in the example below, the child resides in Australia, while the transnational family member resides in Bangladesh.

3 Methodology

This research employed a case study design to delve into the complexities of a single family’s video communication data. A case study approach is appropriate since by focusing on one or a few cases this approach allows the analysis of complex processes, incorporation of rich detail, and application to a real-world context, all of which are relevant to MIA (McCorcle and Bell 1986). In the following sections, we first describe MDA and MIA, followed by our approach to data collection and analyses.

3.1 Multimodal discourse analysis

Multimodal Discourse Analysis is a method that extends traditional discourse analysis (Paltridge 2021) by incorporating various semiotic resources beyond language, such as images, gestures and actions, into the analysis of meaning-making processes (Qin and Wang 2021). This approach has gained prominence in different fields, including education, linguistics, and psychology, with researchers highlighting its advantages and emphasising its ability to offer unique insights and analytical parameters compared to other analytical methods (Qi and Hu 2022).

3.2 Multimodal (inter)action analysis

Norris’s (2004) framework provides a theoretical background and a set of analytical tools for MDA. This framework and set of tools, called Multimodal (Inter)action Analysis (MIA), highlight the various semiotic resources that mediate communication and interaction. The parentheses emphasize that the analysis not only examines interaction (the dynamic, real-time exchanges between people) but also considers action (the broader, contextually situated activities that people engage in) (Norris 2019). This nuanced naming underscores the importance of both immediate interactions and the larger actions within which these interactions are embedded. These interactions may involve semiotic resources such as speech, gestures, and tone to understand the social dimensions of language use. According to Norris (2016), “a main theoretical notion in this framework is the concept of mediation” (147). Norris adopted the concept of mediation into a specific unit of analysis, – “mediated action” (Norris 2016: 147), which refers to how human participants use various communication modes and cultural tools (media) to act and interact in a specific setting. Norris (2013) defines a mode as a “system of mediated action with regularities” (156) and depicts how (inter)actions can be produced through multiple modes being employed simultaneously, with some modes becoming more relevant than others in an (inter)action (Norris 2020). Recently, researchers across a wide variety of disciplines, including education, health, psychology, and literacy, have started applying Norris’s (2004) MIA. Multimodal (inter)action analysis is appropriate for breaking down elements like gaze, proximity, and arm movements. It has been used to study interactions, such as those between teachers and students (Wigham and Satar 2024) and in live classroom settings (Norris 2014). In a video ethnographic study of a Skype interaction between family members in New Zealand, Norris (2016) shows, using various analytical tools such as modal density, that as conversations proceed, the focus changes from the medium of interaction (Skype) to the conversation itself with the conversation becoming more natural.

In the MIA framework, all actions are mediated actions, and the three key methodological units of analysis are Lower-Level Mediated Action (LLMA), Higher Level Mediated Action (HLMA), and Frozen Mediated Action (Norris 2016). Norris (2020) illustrates every social (inter)action as potentially multimodal. These and the three other units described below allow us to dissect these intricate interactions across different levels of detail. The units of analysis or analytical tools are as follows:

Lower-Level Mediated Action (LLMA): The most basic unit of meaning within a specific communication mode, which is treated as a “social actor acting with or through mediational means or cultural tools” (Norris 2019: 237) represents this framework’s most granular building block. For instance, a single emoji or a brief text message would be categorised as LLMA.

Higher-Level Mediated Action (HLMA): Represents a broader concept constructed from a series of lower-level actions and can be labelled as “the multiple chains of lower-level mediated action that come together to produce the higher-level mediated action at the same time as they are produced by the higher-level mediated action” (Norris 2019: 238–239). For instance, an entire video conversation between a child and grandparent would be considered an HLMA, encompassing numerous LLMAs like gestures, spoken words, and changes in facial expressions.

Frozen-Mediated Action: Focuses on how past actions become embedded within the digital insider space, where communication is taking place, and can be featured as “lower or higher-level mediated actions, performed at an earlier time, may become frozen in objects or the environment” (Norris 2019: 241). This could involve a child customising his/her virtual background during a video call, where the background becomes a frozen representation of a prior action.

Modal Density: Analyses the intensity and complexity of lower-level actions co-occurring within a higher-level action (Norris 2019). For example, a child’s actions while excitedly talking to their grandmother on a video call might include handling the phone, smiling, and speaking – all happening concurrently. This scenario would exhibit a higher modal density than a simple text message exchange.

Modal Density Foreground-Background Continuum of Attention/Awareness: Examines how participants distribute their attention across different modes during a higher-level mediated action (Norris 2019). An example might involve a child simultaneously switching her attention to a different mode while communicating with her grandmother through a video call or a higher-level mediated action, such as changing the background of her computer screen. These analytical tools are summarised in Table 1.

Norris’s tools with examples.

| Concept | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lower-level mediated action (LLMA) | The smallest unit of meaning within a specific communication mode | During a video conversation between a child and her grandmother, the grandmother is appraising her own emotion and saying to her granddaughter, “I am feeling sad”, which represents a building block for larger communication units with specific segments of emotional appraisals such as this or emotional outbursts and expressions |

| Higher-level mediated action (HLMA) | Larger communication units are formed by chaining multiple LLMA | The entire video conversation over a smartphone between a child and her grandmother |

| Frozen-mediated action | LLMA or HLMA captured in objects or the environment | The child engages a button on the computer screen to change her virtual background- the mediated actions are frozen in the environment |

| Modal density | Intensity and complexity of LLMA within an HLMA | The child performing multiple actions simultaneously- rotating a phone, smiling, and speaking concurrently during the video call |

| Foreground-background continuum of attention/awareness | Examining attention levels paid to different HLMA simultaneously | The child shifting attention between the video call and changing the background on the phone |

Norris’s (2004) MIA is also flexible in that it allows the integration of multiple forms of data, including images, interviews, text, and video. This integration emphasises the interconnectedness of different semiotic resources, allowing researchers to analyse how these modalities interact to create meaning. Thus, for instance, integrating visual elements with spoken language, gestures and images can complement and enhance verbal communication (Norris 2002, 2011). The MIA framework is robust enough to encompass and analyse diverse data types, providing a comprehensive understanding of multimodal interactions.

It is important to realise that in addition to MIA, other approaches to multimodal analysis exist (LeVine and Scollon 2004; Van Leeuwen 2005). This essay, however, utilises Norris’s (2004) MIA framework to capture the complexities of digital communication. Unlike social semiotics, which prioritises social and cultural meaning (Karamullaoglu and Sandıkçı 2019), Norris’s (2004) framework offers an approach for exploring interactions across various modes on digital platforms like Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp. This scope is essential for understanding how digital communication modes and emotions arising during online interactions contribute to meaning-making (Norris 2016), which is a principal goal of this study. While social semiotics and Norris’s MIA have different focal points, they can be complementary. Social semiotics provides insights into the cultural and social contexts of communication, whereas Norris’s MIA offers a detailed analysis of the interactional dynamics across multiple modes, enriching our understanding of digital communication (Poria et al. 2017). This applies to our study, which aims to demonstrate the use of MIA in sociolinguistics to analyse video communication data among immigrants. The specifics of our study are described next.

3.3 Participant selection

The family investigated in this example belonged to a larger heritage language maintenance project examining digital communication practices among transnational Bengali-speaking immigrants in Australia. Following purposive sampling (Cohen et al. 2002), the family was recruited through a Facebook advertisement posted by the researcher (Inclusion criteria specified Bengali immigrant families residing in Australia with a focal child between the ages of five and eighteen who regularly communicated at least once a week) with transnational family members, preferably grandparents, using digital platforms like WhatsApp or Facebook Messenger.

The family profile (with pseudonyms) is as follows: The Ali family has resided in Australia for over ten years. Isha (aged eight at the time of the video conversation) engages in weekly video calls with her grandmother, Nasima (a 66-year-old housewife residing in Bangladesh). Isha’s mother, Fana, lives with her daughter and husband in Australia. Bengali served as the family’s primary or heritage language.

3.4 Collecting data

In this example, data were collected from two sources. The first was a participant-led video recording provided by the mother, Fana, of the focal child or the child in the family who is being studied interacting with her transnational grandmother, captured via the Facebook Messenger App. The specific video recording was chosen because of the richness of the multimodal data in the clip, its relevance to our research objectives, and its encapsulation of critical moments in the conversation, including the crying and kissing sequence described in the analysis section.

The second source consisted of researcher-led semi-structured interviews with the immigrant parents and grandparents. The mother and grandmother were interviewed separately over the phone at times convenient to them for around an hour. The interview data included questions about the participants’ beliefs or ideologies, practices, and heritage language maintenance strategies, which helped unpack their sociocultural, emotional, and linguistic practices. Information was obtained on the participants’ multimodal communication practices, which helped influence their heritage language maintenance. The interview data provided additional layers of insight that video data may not capture on their own, and thus enabled researchers to see things from the participants’ perspective, understand the bigger picture, allow for triangulation, and ensure the accuracy and depth of their analysis (Norris 2011; Norris and Maier 2014). Interviews were translated and transcribed by the first author.

Data were collected between March and August 2022, when the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic was over though some families were not travelling internationally because of various restrictions and fear of infection.

Regarding positionality, the first author is from a similar cultural and ethnic background to the participants, and provides an emic perspective (Cohen et al. 2002), enabling a deep understanding of the data and playing a supportive role by providing context and cultural understanding that can lead to a more accurate and meaningful translation of the data. Also, the relevant University ethics board approved this study (Approval Number: HC220021).

3.5 Coding data

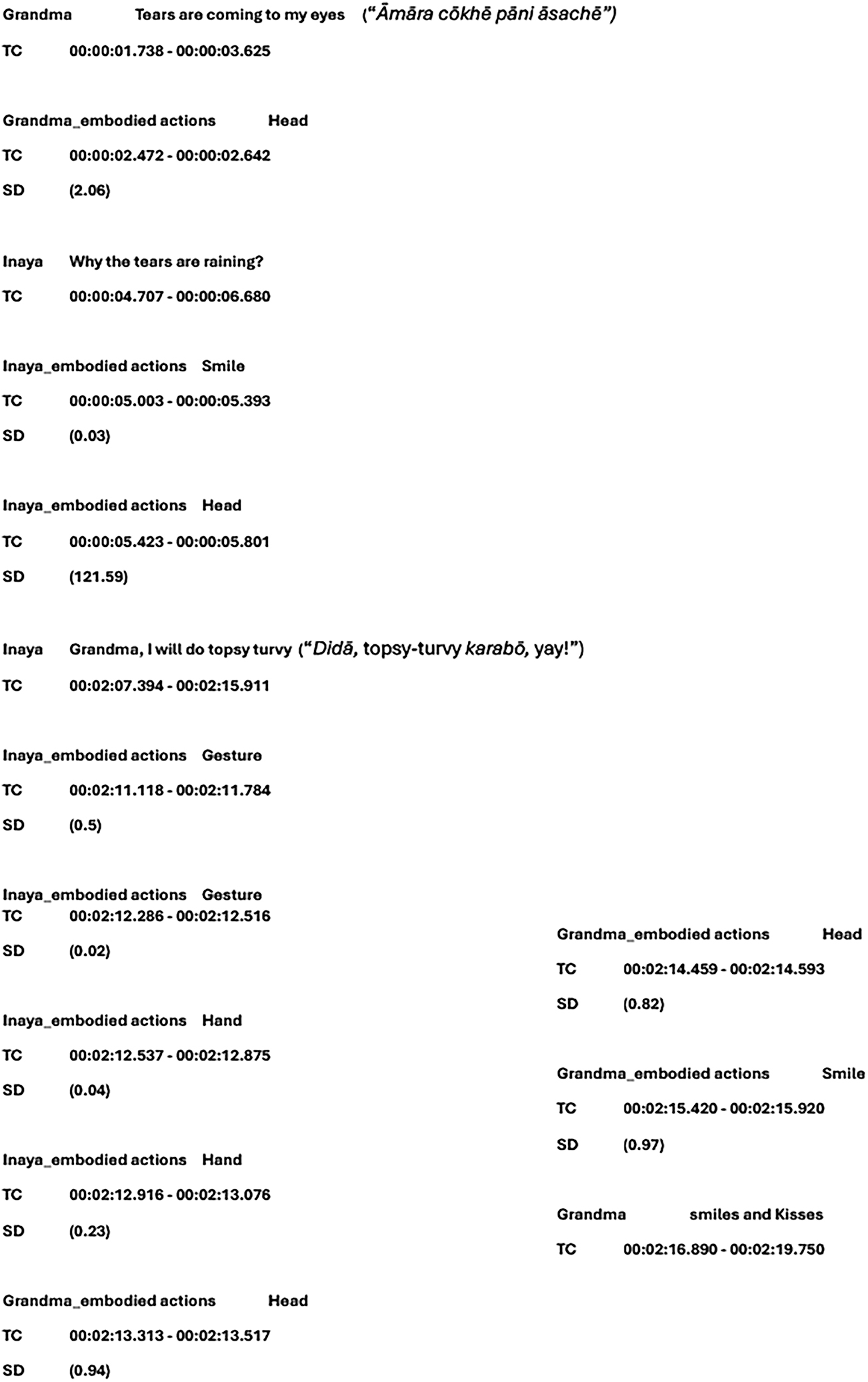

Video conversation recordings were analysed using the European distributed corpora project Linguistic ANnotator (ELAN) software (Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics 2023). The first author became aware of the ELAN multimodal software from Norris’s (2019) book, researched the software, and then translated the video recordings into English and reviewed and transcribed video recordings using the ELAN software. This software allowed for annotating and timestamping interactions and embodied actions (e.g., smiles) (Sugahara et al. 2022). A detailed step-by-step guide to how the ELAN software was used in this study is provided in supplementary material A.1. Overall, ELAN provides a comprehensive suite of tools for managing and analysing multimodal data. Figure 1 below shows a screenshot of an ELAN annotation, illustrating how communication and embodied actions are timestamped and annotated.

ELAN annotation screenshot.

Having discussed how the analysis can be realised, in the next section, we move on to an example of using MIA to explore the close bond between Isha (child) and Nasima (grandmother). All analyses are presented with screenshot data of the interactions. Before proceeding to the application of MIA, we will discuss what additional knowledge is gleaned from the interview data, including the context in which the video calls unfold.

4 Analysis

4.1 Interview data: the importance of video calls in maintaining heritage language

The interview data provides context to the video call between Isha and Nasima. Video calls were typically made twice a week from Isha’s home in Australia and her grandmother Nasima’s home in Bangladesh, though occasionally Nasima might call from other locations in Bangladesh. The twice-a- week video calls lasted, on average, for 50 min, but if Isha had homework or other work, the conversation would be shorter. In the interview, Isha’s mother (Fana) thought that video calls through the Facebook Messenger app were essential for both Isha and Nasima (her grandmother) for emotional bonding and heritage language maintenance: “I don’t want my daughter to be very, very fluent in Bengali. I just want her to talk in Bengali to make her grandparents comfortable.”, – the statement underscoring the importance of bonding over heritage language practice in such conversations. Both Bengali and English are used during these conversations. This paper includes both the original heritage language (Bengali) and the English translations of the Bengali conversations. According to her mother (Fana), Isha is fluent in English and has basic proficiency in Bengali. In turn, Nasima is a native speaker of Bengali with some basic English proficiency.

During the interview, Nasima expressed her positive attitude towards helping her grandchild practice Bengali through the Facebook messenger app (See Excerpt 1 below):

| This is an excellent gift because I can at least talk to and see her and get to know what Isha is doing regularly. It would have been very bad or upsetting if there had not been such online tools for digital communication (Nasima). |

The interview data thus tell us that there is a strong emotional need as well as the need for heritage language to communicate regularly over video chats. In the next section, we observe how Isha consoles her distraught grandmother during a video conversation over Facebook Messenger and analyse it using Norris’s MIA.

4.2 Video data: emotions and heritage language practice using multimodal (inter)action analysis

The entire example, which is a video conversation between a child and her grandmother, is an instance of what Norris (Norris 2004, 2019) calls an HLMA since, as we shall see, this HLMA comprises multiple chains of LLMA coming together.

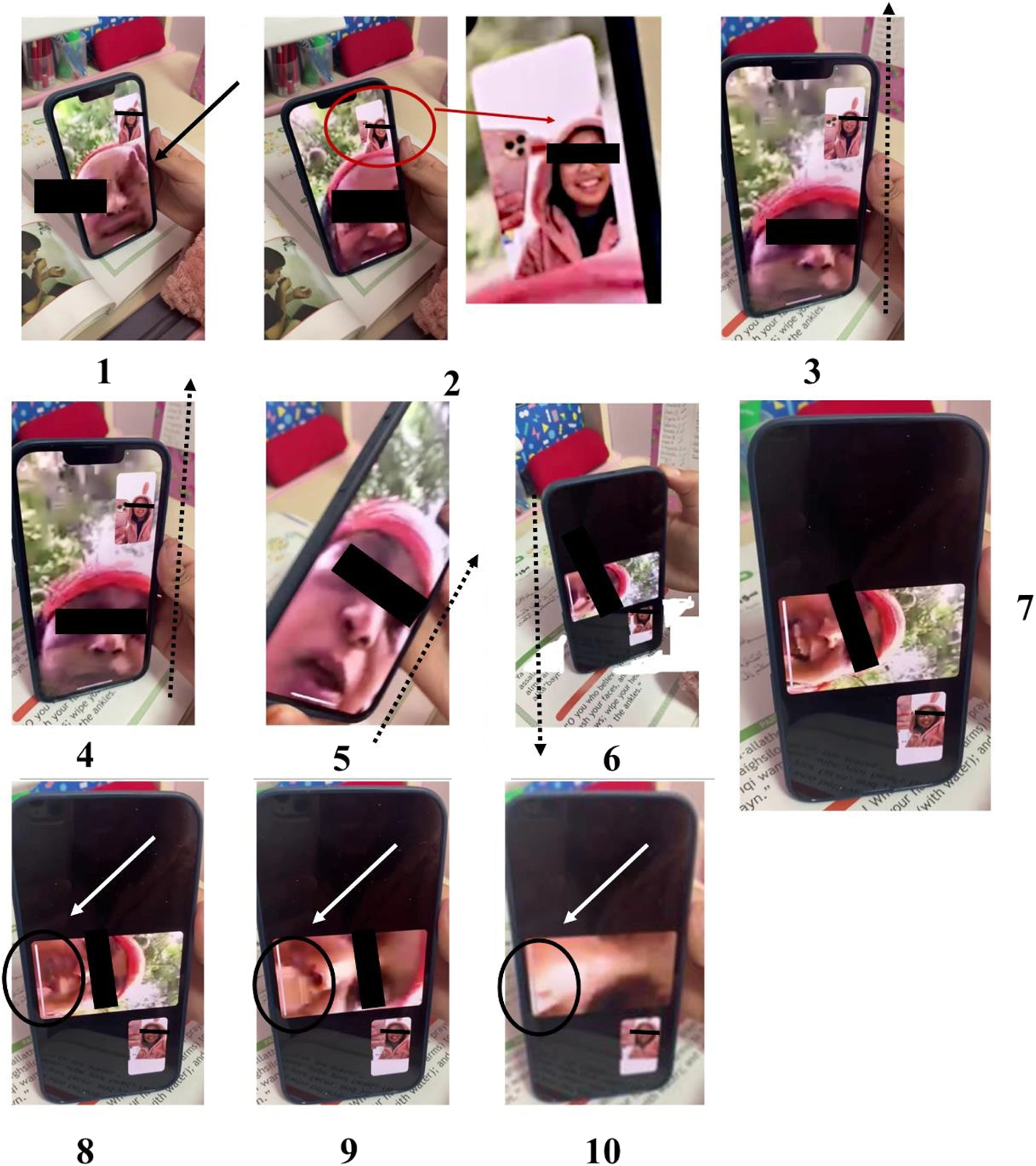

The beginning of the video conversation shows Nasima crying and appraising her emotion, saying, “Āmāra cōkhē pāni āsachē [Tears are coming to my eyes] (Figure 2: Panel 1). The image annotated with an arrow pointing to Nasima wiping tears from one eye with her left hand shows her face and mouth are contorted from crying. When Isha asks her grandma the reason (Figure 2: Panel 2, also with enlargement) with a smile, Nasima says, Tōmarā Bangladesha āschōnā. Tomar bābā sick, Māmā sick, Ēbaṁ ṭumi’ō COVID-19 ēra kāraṇē sick, ēbaṁ āmi tōmākē dēkhatēō yatna nitē pārachi nā [You are not coming to Bangladesh. Your daddy is sick, mamma is sick, and you are also sick due to COVID-19, and I can’t see and take care of you guys]. Empathising with her grandmother’s sorrow, Isha tries to console her: “Didā, please cry karōnā. Āmarā asustha halē ki habē? Āmi jāni, ānēka sad āsē. We have to deal with it. Tabē āmarā sabasamaẏa bhiḍi’ō kala karatē pāri”. [Grandma, please don’t cry. What will we do if we are sick? I know, this is very sad. We have to deal with it. But we can always do video calls].

In this case, the HLMA aims to provide emotional support and maintain the connection between a grandchild and her distant grandmother. Nasima’s initial expression of sadness (tears, emotional statement) initiates the HLMA, prompting Isha’s empathic response (words, smile) within the video call environment. This example demonstrates how HLMA facilitates emotional exchange and coping strategies within digital grandparent-grandchild relationships, highlighting the unique affordances of video calls for practising heritage language and managing strong emotions despite physical distance. The LLMAs that comprise this HLMA are discussed next.

Isha then continues by enacting a fun activity over the video, “Didā, topsy-turvy karabō, yay!” [Grandma, I will do topsy-turvy, yay!] (Figure 2: Panel 3–6, – dotted line showing phone rotation), where Isha slides the mobile phone from a vertical to a horizontal position and then again back to an upright position. These activities seem to bear fruit, as grandma Nasima is visibly happy and smiling (Figure 2: Panel 7). The grandmother then reciprocates her happiness by kissing Isha over the phone (Figure 2: Panel 8–10). The circles and arrows (Panels 8–10) point to the kissing process. In Panel 8, Nasima’s mouth is open in an “O” in preparation for kissing; in Panel 9, her mouth is pressed flat against the screen as she starts to kiss, and in Panel 10, only her nose can be seen as she presses her mouth even more into the screen to complete the kiss. Nasima’s kissing her granddaughter over the phone and Isha’s reciprocity through her smile further strengthen their love and affection for each other. Although Nasima was busy interacting with Isha, which was the main focus of the video conversation, the task consisted of multiple LLMA of high modal density, with intense emotions, switching of attention between grandmother and the phone with coordination of actions (Isha rotating the mobile phone) (Norris 2019). This interaction showcases LLMA (Norris 2019), encompassing individual actions within the “topsy-turvy” activity. Isha’s LLMA includes announcing the activity, rotating the phone, and smiling. Nasima’s LLMA includes facial expressions, responding verbally, and performing the kissing gesture. Each LLMA contributes to the goal of shared joy.

Through multimodal cues, such as smiling, sliding the mobile phone from vertical to horizontal and back again, and verbal comfort, such as announcing the phone rotation activity, Isha attempts to achieve the shared goal of easing Nasima’s sorrow and reinforcing the importance of video communication. Furthermore, high modal density is evident within each LLMA and throughout the activity. Isha’s announcement combines speech and hand gestures. Nasima’s kiss involves facial expressions, body language, and interaction with the phone screen. This dense combination of modes or high modal density enhances emotional expression and understanding. Analysing LLMA and modal density reveals the intricate communication dance between Isha and Nasima, highlighting how they use diverse modes to achieve their shared goal of emotional connection and strengthen their bond despite physical distance. In line with Norris’s (2019) foreground background continuum, the “topsy-turvy” activity (Isha’s speech, phone manipulation) becomes the foreground as a playful attempt to cheer Nasima up. Here, Nasima’s facial expressions (previously background) might become foreground again as she reacts to Isha’s actions. The act of kissing the phone (Nasima’s facial expressions, body language) becomes foreground as a display of affection. Isha’s smile (previously background) becomes foreground again in response to the kiss. The kiss also serves as an instance of frozen mediated action since it is not real-time and represents a fleeting snapshot of a social act-an act of emotional expression. The use of Bengali as a heritage language by Isha to support her actions is backgrounded.

In the above activities, the grandmother expresses sadness, and the grandchild consoles her; these actions are placed in the foreground. The child’s playful activities, like rotating the phone and making the grandmother smile, are also foregrounded. All of these foregrounded activities emphasise emotional bonding. Heritage language practice, while present, is not the main focus, it is part of the background and supports the primary goal of bonding. The use of Bengali language occurs naturally within the context of their emotional exchanges, and it is secondary to the expressions of empathy and affection. The above interaction is characterised by mutual emotional support, shared activities, and the use of heritage language. Isha and Nasima thus co-construct their identities horizontally through their peer-like relationship, emphasising emotional connection and shared experiences over hierarchical family roles.

While there is no strict definition of empathy in the literature, there is general agreement that empathy comprises taking another person’s perspective, sharing emotions, relating-connection-bonding, and taking action to help others (Hall et al. 2021), all of which are identifiable in the conversation between Isha and Nasima. While in Bengali culture, the open expression of emotions is not particularly common and may involve various gendered cultural norms (Gross and John 2003), the special bond between grandparents and grandchildren is cherished and considered of great importance, being observed previously in the literature, for instance, among Bengali grandparents in East London, primarily through the use of “touch, gesture and gaze” (Jessel et al. 2011: 42). There are additional reasons for the display of emotions. First, the family’s transnational nature and the stress of the COVID pandemic and forced isolation caused the visible emotional outburst. The mother vouched for the bond between grandma and grandchild, mentioning during the interview that on the video, Isha used to say regularly in Bengali, “Didā āmi tōmāẏa anēka ‘love’ kari” [Grandma, I love you very much].

The affordances of multimodal digital media-based emotional streaming (King-O’Rian 2015) allow a high degree of empathy between the child and the grandmother during heritage language practice, which would have been difficult if the communication were to be realised over a modally poor medium. This conversation, especially with the emotional context, can contribute to Isha’s overall language development (Curdt-Christiansen and Huang 2020) (Figure 2).

Emotions and heritage language practice. The dotted arrow in panels three to six shows the phone rotation.

5 Discussion

This essay highlights the utility of MIA in understanding digital communication in a transnational multilingual family. By utilising Norris’s (2004, 2019) framework for analysing multimodal data, the research captures the intricate layers of emotion within digital interactions between transnational families practising heritage language. Norris’s (2004, 2019) framework with concepts such as HLMA, LLMA, and modal density proved particularly useful in understanding emotions and heritage language practice using digital communication.

Our study sets itself apart from the existing heritage language practice-related literature in several ways. First, while previous studies have acknowledged the role of grandparents and senior family members in a child’s heritage language and multicultural development within the same household (Ruby 2012; Smith-Christmas et al. 2019), such interactions were typically face-to-face. In contrast, our study focuses on digital communications between children and their transnational grandparents. A few studies have explored heritage language in the digital realm but focus only on the conversation transcribed as text (Lexander and Androutsopoulos 2023; Sari and Moore 2024). While the previously discussed study by Curdt-Christiansen and Iwaniec (2023) explores emotions and heritage language through emojis and conversations in such digital exchanges, our study expands on the topic by leveraging the power of MIA to unpack the video data and understand how emotions and heritage language interact during digital conversations between children and transnational grandparents.

Multimodal (inter)action analysis contributed to this study of heritage language maintenance in various ways. First, analysing videos using MIA allowed us to understand the interplay of emotions alongside heritage language practice. This included gestures, emotional outbursts, and conversations situated within HLMAs. Second, dissecting HLMAs, like emotional support, and analysing LLMAs, like Isha’s phone rotation and Nasima’s kiss, provided a nuanced understanding of the digital discourse.

Third, modal density analysis of each LLMA revealed the richness of emotional expression and understanding. For instance, analysing the foreground-background continuum (shifting attention between phone and background) highlighted how digital communication facilitates emotional connection. Importantly, while emotional bonding through various activities such as crying and kissing or phone rotation are foregrounded, heritage language practice happens automatically and is backgrounded.

The study also demonstrates the value of using MIA to enhance the trustworthiness and depth of findings using different data sources (Norris 2011; Norris and Maier 2014). This enriches our understanding of emotions during heritage language practice. Overall, using MIA with video data offered a powerful lens to explore the complex interplay of emotions, gestures, and language use in digital communications, promoting heritage language practice.

To summarise, using Norris’s (2004, 2019) MIA framework and tools, MDA can provide new insights into multimodal data from different disciplines. This method provides a structured approach to explore how different semiotic modes are utilised, offering valuable insights into the creation of meaning through various modalities.

6 Conclusions

We find in this study that the primary motivator for digital interactions between the grandchild and grandmother is emotional bonding rather than heritage language practice. We show that MDA using Norris’s (2004) MIA framework and the analytical tools offer a new approach to sociolinguistic research, expanding traditional discourse analysis by analysing the interplay of various semiotic resources in digital interactions (Iedema 2003; Kress and Van Leeuwen 2001). The study underscores the importance of regular, emotionally engaging digital interactions for maintaining family bonds and supporting heritage language practice in transnational families.

6.1 Reflections on the use of multimodal (inter)action analysis

The first reflection from this study is that including interview data from the child’s mother and grandmother provided valuable context and helped understand the participants’ motivations and perspectives regarding the child’s heritage language practice during digital communication, highlighting the importance of different data sources in such analyses (Norris 2011; Norris and Maier 2014). Future MDA studies can thus utilise interviews of children to further support and contextualise their findings.

One critique of this study could be that Norris’s (2004, 2019) MIA framework was used to analyse specific aspects of digital interaction. Relying solely on one particular framework and analytical tools such as MIA may have its limitations. For instance, the MIA framework relies on dissecting multimodal elements of the data. However, broader social and contextual elements such as cultural norms or family dynamics do not guide the analyses. Alternatively, the framework does not account for the power dynamics between the people engaged in digital discourse, which may require different considerations (Van Leeuwen 2012). Also, deciding how to segment interactions into HLMA and LLMA may be subjective and require considerable effort, time, and clarity of judgment on the part of the analyst. Some analysts may find setting up tiers in the ELAN software time-consuming, though this comes with the benefit of providing analytical depth. Therefore, alternative MDA frameworks and other considerations may be contemplated depending on the research question, and these might also expose different insights.

Various aspects of our study provide directions to strengthen future research. Thus, pilot testing the chosen approach on a small sample of data before applying it to the entire dataset may reveal the nuances of the specific communication context. Also, as discussed above, multimodal analyses combined with analyses of data such as interviews, surveys, and observations are essential to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the communication process. This broadened scope could help solidify the findings and provide a more generalisable understanding. As alluded to earlier in the text, MIA can be applied and is not limited to the sociolinguistics discipline. In addition to the examples from the education discipline discussed earlier (Wigham and Satar 2024), the approach may offer researchers unique opportunities in media and advertising, where multiple media are often utilised to convey various messages (Zhao et al. 2020). For example, the richness of advertised messages could be analysed using the concept of modal density, and specific elements of advertisements, such as slogans and facial expressions, could be dissected and understood using the LLMA tool. Once again, aspects of modal density and their psychological effects or the effect of specific LLMA elements could be analysed. In addition, future research could explore how these findings apply to different family structures, languages, and technological environments. Additionally, investigating the long-term impact of these digital interactions on heritage language maintenance and emotional well-being would be a valuable area for future study.

This essay showcases the emotional aspects of family bonding and heritage language practice within a transnational immigrant family in Australia using digital communication through Norris’s (2019) MIA framework and tools, and creates new opportunities, as seen here for researchers in socio-linguistics and applied linguistics. By employing MIA to examine the complex interplay between emotions and heritage language practice, we demonstrate that family bonding, rather than heritage language maintenance, is the key motivator of these digital interactions. This highlights the significance of MDA in uncovering the emotional landscape when practising heritage language within seemingly simple family video calls. Our study offers practical insights for families and educators, such as the need for regular, emotionally engaging interactions between children and their transnational family members. For example, grandparents and grandchildren could play online games together, share stories, or engage in creative projects. These activities can foster emotional connections and make heritage language practice more enjoyable. The findings have broader applicability beyond the immediate context of Bengali immigrant families in Australia, in other disciplines and contexts to understand digital communication and emotional bonding, providing a valuable framework for future research.

Funding source: Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP)

Funding source: New South Wales Education Waratah award

References

Blommaert, Jan. 2010. The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511845307Search in Google Scholar

Bose, P., Gao, X., Starfield, S., & Ramdani, J. M. 2023. Conceptualisation of family and language practice in family language policy research on migrants. A systematic review. Language policy. 22(3), 343–365.Search in Google Scholar

Bose, Priyanka, Xuesong Gao, Sue Starfield, Shuting, Sun & Junjun, Muhamad Ramdani 2023. Conceptualisation of family and language practice in family language policy research on migrants: A systematic review. Language Policy. 22(3), 343–365.10.1007/s10993-023-09661-8Search in Google Scholar

Bose, Priyanka, Xuesong Gao, Sue Starfield, Nirukshi, Perera. 2024. Understanding networked family language policy: A study among Bengali immigrants in Australia. Current Issues in Language Planning. 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2024.2349405.Search in Google Scholar

Chowdhury, Farzana Yesmen & Sol Rojas-Lizana. 2020. Family language policies among Bangladeshi migrants in Southeast Queensland, Australia. International Multilingual Research Journal. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2020.1846835.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion & Keith Morrison. 2002. Research methods in education. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203224342Search in Google Scholar

Cui, Guoqiang, Barbara Lockee & Cuiqing Meng. 2013. Building modern online social presence: A review of social presence theory and its instructional design implications for future trends. Education and Information Technologies 18. 661–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-012-9192-1.Search in Google Scholar

Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan & Jing Huang. 2020. Factors influencing family language policy. In Andrea C. Schalley & Susana A. Eisenchlas (eds.), Handbook of social and affective factors in home language maintenance and development, 174–193. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9781501510175-009Search in Google Scholar

Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan & Janina Iwaniec. 2023. ‘妈妈, I miss you’: Emotional multilingual practices in transnational families. International Journal of Bilingualism 27(2). 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069221125342.Search in Google Scholar

Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2010. Emotions in multiple languages. New York: Springer.10.1057/9780230289505Search in Google Scholar

Geenen, Jarret. 2017. Show and (sometimes) tell: Identity construction and the affordances of video- conferencing. Multimodal Communication 6(1). 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1515/mc-2017-0002.Search in Google Scholar

Gross, James J. & Oliver P. John. 2003. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85(2). 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, Judith A., Rachel Schwartz & Duong Fred. 2021. How do laypeople define empathy? The Journal of Social Psychology 161(1). 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2020.1796567.Search in Google Scholar

Hatoss, Anikó. 2023. Shifting ecologies of family language planning: Hungarian Australian families during COVID-19. Current Issues in Language Planning. 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2023.2205793.Search in Google Scholar

Hollebeke, Ily, Esli Struys & Orhan Agirdag. 2020. Can family language policy predict linguistic, socio- emotional and cognitive child and family outcomes? A systematic review. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1858302.Search in Google Scholar

Iedema, Rick. 2003. Multimodality, resemiotization: Extending the analysis of discourse as multi-semiotic practice. Visual Communication 2(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357203002001751.Search in Google Scholar

Jessel, John, Charmian Kenner, Eve Gregory, Mahera Ruby & Tahera Arju. 2011. Different spaces: Learning and literacy with children and their grandparents in east London homes. Linguistics and Education 22(1). 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2010.11.008.Search in Google Scholar

Karamullaoglu, Nazife & Özlem Sandıkçı. 2019. Western influences in Turkish advertising. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 12(1). 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhrm-10-2018-0050.Search in Google Scholar

King-O’Rian, Rebecca Chiyoko. 2015. Emotional streaming and transconnectivity: Skype and emotion practices in transnational families in Ireland. Global Networks 15(2). 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12072.Search in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther R. & Theo Van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

LeVine, Philip & Ron Scollon. 2004. Discourse and technology. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lexander, Kristin Vold & Jannis Androutsopoulos. 2023. ‘Doing Family’online: Translocality, connectivity, and affection. In Multilingual families in a digital age, 107–134. London: Taylor & Francis.Search in Google Scholar

Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. 2023. The language archive. ELAN, 6.6 edn. Nijmegen.Search in Google Scholar

McCorcle, Mitchell D. & Ella Louise Bell. 1986. Case study research: Design and methods. Evaluation and Program Planning 9(4). 373–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(86)90052-2.Search in Google Scholar

Mehrabian, Albert & Susan R. Ferris. 1967. Inference of attitudes from nonverbal communication in two channels. Journal of Consulting Psychology 31(3). 248. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0024648.Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Sigrid. 2002. The implication of visual research for discourse analysis: Transcription beyond language. Visual Communication 1(1). 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/147035720200100108.Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Sigrid. 2004. Analyzing multimodal interaction: A methodological framework. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203379493Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Sigrid. 2011. Identity in (inter) action: Introducing multimodal (inter) action analysis. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9781934078280Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Sigrid. 2013. Multimodal (inter)action Analysis. In Peggy Albers, Teri Holbrook & Amy Flint (eds.), New methods of literacy research. London, New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Sigrid. 2014. Learning tacit classroom participation. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 141. 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.030.Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Sigrid. 2016. Concepts in multimodal discourse analysis with examples from video conferencing. In Yearbook of the Poznan linguistic meeting. This is a conference proceeding with no further information.10.1515/yplm-2016-0007Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Sigrid. 2019. Systematically working with multimodal data: Research methods in multimodal discourse analysis. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.10.1002/9781119168355Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Sigrid. 2020. Multimodal theory and methodology: For the analysis of (inter) action and identity. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429351600Search in Google Scholar

Norris, Sigrid & Carmen Maier. 2014. Interactions, images and texts: A reader in multimodality. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781614511175Search in Google Scholar

Paltridge, Brian. 2021. Discourse analysis: An introduction. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Poria, Soujanya, Zhaoxia Wang, Ram Bajpai & Amir Hussain. 2017. A review of affective computing: From unimodal analysis to multimodal fusion. Information Fusion 37: 98–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2017.02.003.Search in Google Scholar

Qi, Wenjin & Yutao Hu. 2022. A multimodal ecological discourse analysis of presentation PowerPoint slides in business English class. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 13(6). 1341–1350. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1306.23.Search in Google Scholar

Qin, Yongli & Ping Wang. 2021. How EFL teachers engage students: A multimodal analysis of pedagogic discourse during classroom lead-ins. Frontiers in Psychology 12. 793495. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.793495.Search in Google Scholar

Ruby, Mahera. 2012. The role of a grandmother in maintaining Bangla with her granddaughter in East London. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 33(1). 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2011.638075.Search in Google Scholar

Said, Fatma F. S. 2021. ‘Ba-SKY-a P with her each day at dinner’: Technology as supporter in the learning and management of home languages. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 42(8). 747–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1924755.Search in Google Scholar

Sari, Artanti Puspita & Leslie C. Moore. 2024. Learning Qur’anic Arabic in a virtual village: Family religious language policy in transnational Indonesian Muslim families. International Journal of Bilingualism. 13670069241256194. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069241256194.Search in Google Scholar

Schwartz, Mila & Anna Verschik. 2013. Achieving success in family language policy: Parents, children and educators in interaction. Successful family language policy: Parents, children and educators in interaction, 1–20. London: Springer.10.1007/978-94-007-7753-8_1Search in Google Scholar

Sevinç, Yeşim & Seyed Hadi Mirvahedi. 2023. Emotions and multilingualism in family language policy: Introduction to the special issue. International Journal of Bilingualism 27(2). 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069221131762.Search in Google Scholar

Smith-Christmas, Cassie, Mari Bergroth & Irem Bezcioğlu-Göktolga. 2019. A kind of success story: Family language policy in three different sociopolitical contexts. International Multilingual Research Journal 13(2). 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2019.1565634.Search in Google Scholar

Sugahara, Mayara Kamimura, Simoni Camilo da Silva, Monica Scattolin, Fernanda Miranda da Cruz, Jacy Perissinoto & Ana Carina Tamanaha. 2022. Exploratory study on the multimodal analysis of the joint attention. Audiology – Communication Research 27: e2447.10.1590/2317-6431-2020-2447ptSearch in Google Scholar

Taipale, Sakari. 2019. What Is a ‘Digital Family’? In Intergenerational connections in digital families, 11–24. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-11947-8_2Search in Google Scholar

Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2005. Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203647028Search in Google Scholar

Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2012. Critical analysis of multimodal discourse. In: Chapelle CA (ed.) The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. 1–5. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0269Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Min & Sender Dovchin. 2022. “Why should I not Speak My Own Language (Chinese) in Public in America?”: Linguistic racism, symbolic violence, and resistance. Tesol Quarterly 57. 1139–1166. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3179.Search in Google Scholar

Wigham, Ciara R. & Müge Satar. 2024. Adapting and extending multimodal (inter) action analysis to investigate synchronous multimodal online language teaching. Multimodal Communication 13(3). 415–426. https://doi.org/10.1515/mc-2024-0048.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, Meng-dan, Zi-qing Lyu, Qiu-xian Cheng & Ri-liu Huang. 2020. Tobacco control intervention: A comparative multimodal discourse analysis of video advertisements in China and Australia. Journal of Literature and Art Studies 10(4). 313–320. https://doi.org/10.17265/2159-5836/2020.04.007.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, Sumin. 2019. Social media, video data and heritage language learning: Researching the transnational literacy practices of young children from immigrant families. In The Routledge international handbook of learning with technology in early childhood, 107–126. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315143040-8Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The role of gestures in logic

- A multimodal discourse analysis of the music video ‘IBA’

- Discourses of division during the cost-of-living crisis: digital popular culture responds to governmental actions

- Italia: Open to meraviglia at the intersection of art, gender and tourism discourses

- ‘Why do they not want to play with me?’: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of the construction of colourism in cartoon films

- Essay

- Multimodal (inter)action analysis in sociolinguistics: an essay analysing a digital video conversation illustrating emotion and heritage language maintenance

- Research Articles

- ‘Title gone’: a multimodal appraisal of Nigerian internet users’ visual representation of Arsenal football club

- Beyond bonding icons: memes in interactional sequences in digital communities of practice

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The role of gestures in logic

- A multimodal discourse analysis of the music video ‘IBA’

- Discourses of division during the cost-of-living crisis: digital popular culture responds to governmental actions

- Italia: Open to meraviglia at the intersection of art, gender and tourism discourses

- ‘Why do they not want to play with me?’: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of the construction of colourism in cartoon films

- Essay

- Multimodal (inter)action analysis in sociolinguistics: an essay analysing a digital video conversation illustrating emotion and heritage language maintenance

- Research Articles

- ‘Title gone’: a multimodal appraisal of Nigerian internet users’ visual representation of Arsenal football club

- Beyond bonding icons: memes in interactional sequences in digital communities of practice