Abstract

This paper outlines a unit on linguistics in the curriculum of the writing seminar taken by all undergraduate students at the University of Pennsylvania. The linguistic unit introduces undergraduates to key concepts from linguistic scholarship, and compels students to engage with these language issues in order to advance their consciousness of linguistic inequity and their appreciation of linguistic diversity. Taking our cue from linguists, the unit focuses on the descriptive and contrasts it with the prescriptive approach with which they are typically accustomed. It introduces foundational ideas about language, languaging, and linguistic discrimination through readings and videos. Students write guided reflections in response to the readings and screenings, culminating in a personal narrative and questions they share with their peers on an online discussion board, exploring their own and others’ language use or language attitudes. Upon completion of this unit, many students confirm one of the unit’s learning outcomes by expressing a new awareness of a linguistic climate that they had previously assumed was neutral. Our goal, in part, is to render the campus’s linguistic climate more equitable by advancing students’ consciousness of linguistic inequity and appreciation of the rich diversity of their voices.

1 Introduction

In this paper we outline a unit on linguistics in the curriculum of the writing seminar taken by all undergraduate students at the University of Pennsylvania. The linguistic unit introduces undergraduates to key concepts from linguistic scholarship and compels students to engage with these language issues in order to advance their consciousness of linguistic inequity and their appreciation of diverse varieties of language. With the understanding that most students will not have the opportunity to take a full linguistics course before graduating, including this unit in the writing curriculum is linguistic “inreach” to all undergraduates, exposing them to key concepts surrounding linguistic diversity, languaging, and linguistic discrimination.

Founded in 1740, Penn is an Ivy League university located in Philadelphia. It has twelve graduate and four undergraduate schools. In 2007, it became the largest school in the nation to offer an all-grant, no-loan financial aid program to its 10,000 undergraduates. This aid substantially altered student demographics by providing access to students from a range of social and economic backgrounds. Drawing students from all 50 states, currently more than half of Penn’s undergraduate population identifies as BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color; see Figure 1), and 13 % are international students. The four undergraduate schools (Arts and Sciences, Engineering, Nursing, and Wharton) foster a particularly pre-professional atmosphere in which many students are preparing for careers in business, STEM fields, and healthcare. In terms of academic culture, the university remains a predominantly white institution (PWI).

First-year student demographics (Penn Admissions 2023).

The writing seminar functions as an on-ramp to Penn, a shared intellectual experience for first-year students to interact with each other in a small seminar setting (maximum 16 students) while being introduced to academic expectations for postsecondary writing, critical thinking, reading, and research. A highly collaborative course, it brings together students from across diverse cultures and language groups, an ideal setting for an exploration of attitudes toward language use.

The curriculum does not assume a background in linguistics, but we assume that students have already been taught to write in and to privilege Standard Academic English.

2 Linguistic awareness and the college writing curriculum

Both linguists and writing scholars have sought to raise awareness about language variation and diversity for many decades and have brought critical scholarship to bear on language issues in the college writing classroom. In this section we briefly sketch some of these key issues that motivate the inclusion of a linguistic unit in our writing curriculum, and which also serve as pedagogical goals.

2.1 Insights from linguistics

Linguists abide by the principle that no one variety of language is inherently more logical, efficient, or effective than another for communication; Weinreich (1953) makes early reference to this principle in writing about nonstandard language in various countries. Seminal sociolinguistic research in the US also documented nonstandard dialects, such as Labov’s (1968, 1969, 1970 documentation of grammatical and rhetorical features in African American English (AAE) and Smitherman’s (1986) cross-disciplinary work, Talkin and testifyin: The language of Black America (originally published in 1977).

Documenting language variation and diversity led linguists to identify linguistic bias and call out discrimination against speakers of minority language groups, particularly speakers of AAE. Both Labov and Smitherman, for instance, called for linguists to push back against the deficit theory of language in the education of Black children, in which nonstandard speech or writing is viewed as a deviation from a single, correct form of language and speakers of AAE are judged to be deficient in language skills and intelligence. Instead, linguists value an individual’s dialect or language as a rich resource, and bilingualism or bidialectalism as an asset that is intertwined with identity. Smitherman’s (1986) advocacy for linguistic justice in primary and secondary education has since been taken up by other linguists calling for linguistic equity and anti-racist practices, such as Baugh (2003, 2018, Charity Hudley and Mallinson (2018), Godley et al. (2006), Lippi-Green (2022), and Rickford and King (2016), among many others. This line of research has come to extend beyond the field of education, crossing disciplinary boundaries into national language policy, educational policy, and linguistic profiling in employment and housing, and has profound implications for criminal law.

2.2 Bringing linguistics into the writing classroom

James Berlin’s influential history of the field of writing studies observed that “the study of linguistics in the English department during the twentieth century has been one of the most formative influences in the study of both literature and rhetoric” (Berlin 1987: 135; see also Aull and Shapiro 2023). Thus it is no surprise that the field of writing studies in the twenty-first century continues to be influenced by the work of linguists on linguistic diversity and discrimination. Along with Smitherman, some other particularly influential sociolinguists include H. Samy Alin, Esther Milu, and Elaine Richardson.

Most notable, perhaps, is Smitherman’s obvious influence as one of the authors of the 1974 position statement, “Students’ right to their own language” (SRTOL), published by the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) – the largest professional organization of rhetoric, writing, and composition scholars in the US (Butler et al. 1974). SRTOL declares: “We affirm the students’ right to their own patterns and varieties of language – the dialects of their nurture or whatever dialects in which they find their own identity and style,” and continues, pointing directly to the field of linguistics, that “language scholars long ago denied that the myth of a standard American dialect has any validity. The claim that any one dialect is unacceptable amounts to an attempt of one social group to exert its dominance over another.” (For an overview of the history of language issues in college composition, see MacDonald 2007 and Smitherman 1999.)

SRTOL continues to be the touchstone for seeing linguistic diversity as an asset and, arguably more important, as the conceptual framework for anti-racist pedagogy in writing classrooms. In 2011, Horner and colleagues, building upon the scholarship that followed the publication of that statement, called for a translingual approach to researching and teaching writing. Borrowing from linguistics scholarship, they proposed a reconceptualization of pedagogical practices to better address linguistic diversity, and that translingualism should work within, but also against, English monolingual norms. Other scholars working in the area of translingualism similarly view language as a fluid, negotiable resource in navigating communication as well as identity (see Canagarajah 2013; Canagarajah and Gao 2019; Horner 2017; Horner et al. 2011; Matsuda 2013; inter alia) and agree that translingualism remains the primary conceptual tool for addressing linguistic diversity and discrimination.

However, translingualism has also been criticized as promoting a “sameness-in-difference” problem, neglecting to foreground SRTOL’s call to address the linguistic violence against marginalized students and their language use. Keith Gilyard’s influential essay on translingualism, for example, noted that

The translanguaging subject generally comes off in the scholarly literature as a sort of linguistic every person, which makes it hard to see the suffering and the political imperative as clearly as in the heyday of SRTOL. In other words, if translanguaging is the unqualified norm, then by definition it is something that all students, including high achievers, perform … Translingualists are clear about the fact that we all differ as language users from each other and in relation to a perceived standard … [But] not all translingual writers are stigmatized in the same manner.” (Gilyard 2016: 285–286)

Gilyard warned that such an approach was likely to alienate Black and Brown scholars working in the field, who may read this as a “devaluing of the historical and unresolved struggles of groups that have been traditionally underrepresented in the academy and suffer disproportionately” from it (2016: 286).

In 2020, a group of Black writing studies scholars, including April Baker-Bell, published “This ain’t another statement! This is a DEMAND for Black linguistic justice!” and provided a list of demands for dismantling white supremacy and centering Black linguistic justice (Baker-Bell et al. 2020). Baker-Bell, a leading scholar on linguistic discrimination in writing studies, also published a book the same year that provided an approach for training instructors as well as for designing curriculum that centers Black students’ needs – linguistic, cultural, racial, and self-confidence. The approach asks teachers to interrogate all aspects of their practice, to consider how it neglects to combat racism and white supremacy. Tessa Brown examined the Writing about Writing pedagogy that she and many other writing instructors have adopted, and found that using it left “whiteness normative and undisturbed” in her classroom (Brown 2020: 599). Brown notes, “today when I teach hip-hop languaging, I do so explicitly in the tradition of the Students’ Right to Their Own Language resolution and in the context of the translingualism movement, with lessons and readings on the sociolinguistics of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and hip-hop language” (2020: 600). Brown uses “reflective writing to ask students to identify their home literacy practices so that the diversity of language experiences and norms in the room never intrudes as a surprise” (2020: 600). Most recently, a collection edited by Do and Rowan (2022) calls for a race-conscious translingualism in writing studies as a field and in writing classrooms.

2.3 Interventions to intentionally reduce language discrimination

While both linguists and writing scholars have emphasized the need for more equitable approaches to linguistic differences, pedagogical approaches are still emerging in the literature; we mention some recent examples here, but do not undertake a full survey. Along with the work of scholars touched upon in the prior section, the sociolinguistic work of Wolfram and Dunstan (2021) addresses language diversity across the campus. Other examples of proposals for writing assignments that implement translingual approaches include Canagarajah’s (2020) literary autobiography and Wang’s (2022) use of autoethnography. Scholars like Cushman (2016) and Presley (2022) outline practices that engage Indigenous histories and language, while Simon (2022) discusses activities focusing on the personal experiences of child language brokers. Beyond the undergraduate writing classroom, other scholarship focuses on Writing Center practices and faculty development (see, for example, Schreiber et al. 2022).

Turning to the field of social psychology, linguistic bias is also studied as part of a broader line of inquiry into social perceptions and bias; controlled experimental conditions are used to determine what specific factors may lead to in-group versus out-group perceptions, group stereotypes, bias, and so on. Two studies in particular, Hansen et al. (2013) and Weyant (2007), propose interventions for reducing or mitigating negative biases.

In an early experimental study on an intervention to reduce linguistic bias, Weyant (2007) draws from previous literature on in-group and out-group behavior and perceptions, which suggests that perspective-taking can reduce unfavorable attitudes toward another social group, particularly a stigmatized group. Perspective-taking is the act of understanding another’s point of view or perceiving an alternate point of view than one’s own. Hypothesizing that perspective-taking can reduce negative attitudes toward accented speakers (who are perceived as members of an out-group), in Weyant’s experimental condition, participants listened to audio recordings of women recounting a personal narrative; participants then wrote a “day in the life” paragraph about what they thought a typical day for that speaker would be like. The results of the study indicate that when participants had engaged in perspective-taking, they judged a speaker with a nonstandard accent to be more intelligent, competent, well educated, and so on compared to the evaluation of the same speaker by participants who had not engaged in perspective-taking.

Building upon Weyant’s findings, Hansen et al. (2013) designed an intervention in which individuals are unexpectedly required to speak in a second language before evaluating nonstandard speakers for personal traits. While participants were ostensibly waiting for the study to begin, they were approached by a peer who asked for directions in a language that was a second language for all subjects. This experience was then followed by a task in which the participants listened to speakers with standard accents and nonstandard accents. Those who had not participated in the intervention evaluated speakers with a nonstandard accent to be less competent than those with a standard accent; this effect was lessened when subjects had participated in the intervention, indicating that “bias against nonstandard-accented speakers can be prevented by an intervention that places the evaluators in the shoes of the evaluated” (Hansen et al. 2013: 73).

These two studies indicate that interventions can result in a significant change in attitudes toward nonstandard language, from which we draw the insight that even brief targeted exposure to, and reflections upon, the experiences of those speaking other language varieties can have significant impact on changing language attitudes and bias. We also follow scholars concerned with the depoliticization of marginalized Black language speakers, and draw these strands of scholarship together in the Linguistic Discrimination unit of our curriculum.

3 The Linguistic Discrimination unit

The Linguistic Discrimination unit is divided into three parts:

Part 1: An overview of key concepts in the field of linguistics, including prescriptive and descriptive grammar, language groups and dialects, Standard Academic English and African American English, linguistic insecurity, discrimination, and diversity.

Part 2: Code-switching, including an emphasis on the cultural function and urgency of code-switching in Black culture.

Part 3: Languaging and identity, with an emphasis on the value of multilingualism.

Each of the sections explores issues of linguistic discrimination as well as appreciation of linguistic diversity. All feature scholarship by and interviews with linguists. Each part concludes with a series of prompts that guide students to write a 150–300-word personal, informal reflection, which is submitted to their instructor in lieu of an open class discussion that may unproductively expose uncomfortable language differences among students. These reflections prepare students for a final discussion board exercise in which they share personal narratives and questions with one another.

3.1 Part 1: overview of linguistic concepts

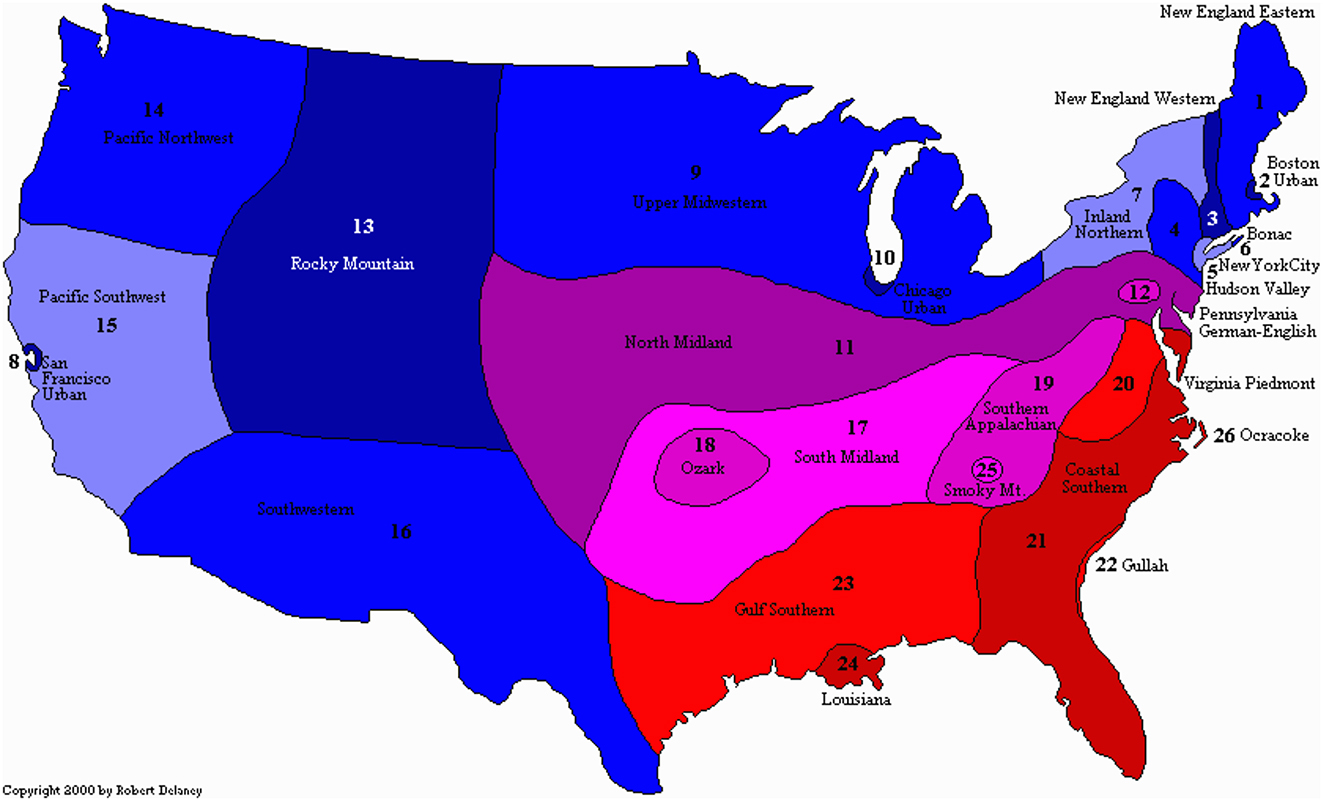

Part 1 introduces students to scholarship in linguistics as well as popular culture, including a simplified map of American English dialects by Robert Delaney (see Figure 2) that was published in the Washington Post (Wilson 2013). Our goal in this overview is to introduce students to the idea of “Englishes” and linguistic diversity, rather than one “proper” English.

Delaney’s simplified map of American dialects (Wilson 2013).

We contrast this map with the work of Jones (2015) on AAE, which demonstrates a similar plurality of AAE subdialects in the US, and also notes a different migration pattern from White English. Where White English followed housing trends in the US, AAE followed the patterns of the Great Migration (see Figure 3).

Migration patterns of African American English speakers (Jones 2015). © 2015 Taylor Jones. Used with permission.

The overview concludes with a writing prompt for a short, informal reflection on what they learned from this unit, including a few low-stakes questions that guide them to evaluate their own attitudes toward language use: “What does a smart person sound like to you? An unintelligent person? A villain? A hero?”

3.2 Part 2: code-switching

The second unit focuses on code-switching. Because students can find code-switching a fun concept, and in so doing miss the urgent and even life-threatening implications of code-switching for marginalized populations, we are careful to remain focused tightly on code-switching as a means of negotiating profound structural inequities. Rather than attempt to narrate this or reduce it to readings, we provide students with a series of links to YouTube videos that include firsthand multifaceted accounts of code-switching, from Black students navigating white schools and friendships, to the media reception of a Black witness, to the Travon Martin shooting and the arrest of Sandra Bland; a Black founder and CEO of a tech start-up discusses the need for code-switching to succeed not only in school but in the workplace; and finally a Black scholar talks about code-switching in his own LA neighborhoods to avoid inter-gang violence as well as in the PWI he attended and now works for.

Hearing the speakers’ own voices in these videos is important because students are engaged not only in learning the concepts, but in hearing Black speakers narrate their own histories and experiences. The example that, anecdotally, appears to be most remarked by students, however, is of former US president Barack Obama in his many displays of code-switching.

The three videos that students screen and respond to in this unit are: “What is code switching?” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QNbdn0yuUw8); “The cost of code switching” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bo3hRq2RnNI); and “Everyday struggle: Switching codes for survival” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJy5yeBSQ7o).

3.3 Part 3: languaging discussion board

In the third part, Languaging and Identity, we once again rely on videos that include interviews with linguistics scholars and firsthand accounts of multilingual experiences. They learn from Jim Cummins how we fail to recognize the linguistic capital that multilingual students bring to the university, instead casting multilingual students as lacking in language skills rather than as having a wide range of linguistic accomplishments, experiences, and resilience (“Jim Cummins on language and identity”; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xuvFaNgAv88).

In turn, in a “Spanglish” video, Spanglish speakers alongside linguist Walt Wolfram discuss how these multilingual speakers typically command two languages and an additional set of rules that govern how, when, and why to switch between the two languages – another form of “code-switching” (“Spanglish”; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nYMnNlfSMC0).

These videos can be eye-opening to students. Those who are multilingual now have ways to describe what they were doing intuitively; monolingual students are given a second lesson in the fact that these different languages, whether Spanglish or AAE, are sophisticated and rule-governed.

4 Student responses and discussion

Students’ written responses are varied, depending on their linguistic and personal histories. Some students express surprise and appreciation for their new awareness of languages issues, never having previously been exposed to concepts such as standard and nonstandard language, or the social and psychological consequences of standard language ideology. Other students respond that they were aware of negative attitudes toward certain accents or dialects, but that the unit provided them with new terminology, research, or testimonials to deepen their understanding. Some of these are American students from immigrant families or from homes where another language is spoken besides English.

Both American and international students take away new insight into the sociolinguistic situation back home, which they had previously not analyzed through the lens of language diversity or linguistic discrimination. Ebunoluwa Akadiri, an international student, writes:

My first experience with linguistic discrimination came from Nigeria, where I spent the first half of my life. Colonized by the British, Nigerians speak British English, expected to put our tribal languages on the back burner prioritizing European standards. Growing up, I attended a private school in Lagos where I was not allowed to speak Yoruba, faced with punishment every time I did not speak English. If you were intelligent, you spoke English. If you want to match the intelligence of white people, which is the goal, you speak British English, not Yoruba, not broken English, and not Pidgin. Those who spoke those languages at my school were “unintelligent” and seen as underdeveloped compared to those who spoke English. When I moved to America, I got my first taste of linguistic discrimination when a classmate asked me why, as a Black person, I talked “white.” It was not until I began to study the origin of AAVE as well as black culture in high school that I understood the implications of the question. I began to study how my privilege as someone with the ability to code-switch, had allowed me to be in spaces with her [white] privilege, [more] than Black people who only speak AAVE. It has allowed me to embody professionalism as portrayed in white spaces, but the question now is: why are languages stigmatized and how are they stigmatized?

For yet other students, the linguistics unit is confirmation of their lived experiences navigating language, identity, race, and culture. These students had already been aware of linguistic discrimination, and had been negotiating language differences at school and beyond. As one student, Laura Gboloo, reflects:

I think that understanding code-switching is an important element of how people of different backgrounds, cultures, ethnicities, etc. interact and communicate with each other. Though basically everyone is forced to code-switch based on different types of situations, code-switching between different racial contexts is especially interesting to me as a black woman. Since I’ve attended PWIs for my entire life, I, like Chandra Arthur describes in her TedTalk, was forced to learn how to code-switch from a young age. I think this is another form of cultural capital that establishes me as a “non-threatening person of color” in white spaces.

These students present nuanced personal narratives about code-switching, both by necessity and by choice, while touching upon the “cultural capital” granted by their language ability.

At the conclusion of the three lessons and after writing self-reflections, students are now asked to post to a class discussion board where they (a) recount a personal narrative that involved an experience with language; and (b) post a genuine question that they want to ask of the other students in the seminar. We caution them to be earnest rather than provocative or rhetorical in their questions.

Responses to this discussion board are diverse and personalized, and allow classmates to glimpse the range of their peers’ lived experiences. Students write about being child language brokers who are forced to translate for immigrant parents; moving to a new town or another country and being ridiculed for their accent; traveling to the country of their ethnic origin and being immersed in the language; and learning sign language and being introduced to Deaf culture; among many other experiences.

The subsequent questions posed under the narratives are respectful and productive (as are the responses to those questions). For example: “Why do you think people form these stereotypes so easily?”; “What would you do if you couldn’t understand your TA [teaching assistant] because of their accent – what is the respectful thing to do?”; “Do you think it’s rude if my friends and I speak Chinese when we’re together, and other people are around who don’t understand Chinese?”

Writing faculty teaching the seminar also find the open-ended writing activities in the linguistic unit to be valuable as a pedagogical approach. One faculty member commented that the asynchronous discussion board “gives students some freedom from how they are perceived in class (verbalizing) their observations. Some students might feel uncomfortable speaking about speaking or could become suddenly aware of their own self-presentation in an in-class discussion. Indeed, I’ve noticed that students who talk less in class often speak a lot more on the Languaging discussion board.” Since the issues can be difficult to broach as an instructor, where classroom discussions risk marginalizing some students, written responses and online discussion allow all students’ voices to be expressed in dialogue with one another. Additionally, the linguistic unit establishes a shared vocabulary of language-related concepts. One instructor remarked that the unit allows him to “thread the conversation about the cultural and social capital of Standard Academic English (and its attendant forms of discrimination and gatekeeping) throughout the next several weeks of class.”

As a final note, developing the linguistic unit as a stand-alone element in the curriculum, rather than explaining these concepts throughout other units, is intentional. Consolidating these important issues in one unit elevates language issues to the same status as other threshold concepts – genre, rhetorical awareness, and logical reasoning – in the writing curriculum. Our goal is to encourage students to engage with these language issues so that their writing process is informed by an awareness of linguistic diversity and linguistic discrimination, rather than a tacit assumption that the standard language of academe is, and should be, default. We should also note that since about 96 % of students enroll in this class in their first year, the lessons they learn spill into the halls, clubs, and dorms, where they continue to be discussed and debated. Our most ambitious goal is that these lessons follow them beyond Penn.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank our writing seminar students for their assignment responses and discussion board posts over the years, which have contributed to our own understanding in meaningful ways. Student feedback included in this paper is quoted with their consent. Thank you also to our colleagues in the writing faculty at Penn for discussions and feedback on the linguistics units in the curriculum. A special thanks to April Baker-Bell for an engaging 2022 workshop with our faculty members.

References

Aull, Laura & Shawna Shapiro. 2023. FAQs about language and linguistics in writing. WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/articles/faqs-about-language-and-linguistics-in-writing/ (accessed 1 June 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Baker-Bell, April. 2020. Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. New York: Taylor & Francis.10.4324/9781315147383Search in Google Scholar

Baker-Bell, April, Bonnie J. Williams-Farrier, Davena Jackson, Lamar Johnson, Carmen Kynard & Teaira McMurtry. 2020. This ain’t another statement! This is a DEMAND for Black linguistic justice! Conference on college composition and communication, National Council Teachers of English. https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/demand-for-black-linguistic-justice (accessed 1 May 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Berlin, James. 1987. Rhetoric and reality: Writing instruction in American colleges, 1900–1985. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Baugh, John. 2003. Linguistic profiling. In Sinfree Makoni, Geneva Smitherman, Arnetha F. Ball & Arthur K. Spears (eds.), Black linguistics: Language, society and politics in Africa and the Americas, 155–168. London & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Baugh, John. 2018. Linguistics in pursuit of justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316597750Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Tessa. 2020. What else do we know? Translingualism and the history of SRTOL as threshold concepts in our field. College Composition & Communication 71(4). 591–619. https://doi.org/10.58680/ccc202030726.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, Melvin A., Adam Casmier, Nina Flores, Jennifer Giannasi, Myrna Harrison, Robert F. Hogan, Richard Lloyd-Jones, Richard A. Long, Elizabeth Martin, Elisabeth McPherson, Nancy S. Prichard, Geneva Smitherman & W. Ross Winterowd. 1974. Students’ right to their own language. College Composition & Communication 25(3). [Special issue].10.58680/ccc197417210Search in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, A. Suresh. 2013. Introduction. In A. Suresh Canagarajah (ed.), Literacy as translingual practice: Between communities and classrooms. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203120293Search in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, A. Suresh. 2020. Transnational literacy autobiographies as translingual writing. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780429259999Search in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, A. Suresh & Xuesong Gao. 2019. Taking translingual scholarship farther. English Teaching & Learning 43. 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-019-00023-4.Search in Google Scholar

Charity Hudley, Anne H. & Mallinson Christine. 2018. Dismantling “the master’s tools”: Moving students’ right to their own language from theory to practice. American Speech 93(3–4). 513–537. https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-7271305.Search in Google Scholar

Cushman, Ellen. 2016. Translingual and decolonial approaches to meaning making. College English 78(3). 234–242. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce201627654.Search in Google Scholar

Do, Tom & Karen Rowan (eds.). 2022. Racing translingualism in composition: Toward a race-conscious translingualism. Denver: University Press of Colorado.10.7330/9781646422104Search in Google Scholar

Gilyard, Keith. 2016. The rhetoric of translingualism. College English 78(3). 284–289. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce201627660.Search in Google Scholar

Godley, Amanda J., Sweetland Julie, Rebecca S. Wheeler, Angela Minnici & Brian D. Carpenter. 2006. Preparing teachers for dialectally diverse classrooms. Educational Researcher 35(8). 30–37. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x035008030.Search in Google Scholar

Hansen, Karolina, Tamara Rakić & Melanie C. Steffens. 2013. When actions speak louder than words: Preventing discrimination of nonstandard speakers. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 33(1). 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x13499761.Search in Google Scholar

Horner, Bruce. 2017. Teaching translingual agency in iteration: Rewriting difference. In Bruce Horner & Laura Tetreault (eds.), Crossing divides: Exploring translingual writing pedagogies and programs, 87–97. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.10.7330/9781607326205.c005Search in Google Scholar

Horner, Bruce, Min-Zhan Lu, Jacqueline Jones Royster & John Trimbur. 2011. Language difference in writing: Toward a translingual approach. College English 73(3). 303–321. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce201113403.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, Taylor.. 2015. Toward a description of African American Vernacular English dialect regions using “Black Twitter.”. American Speech 90(4). 403–440. https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-3442117.Search in Google Scholar

Labov, William.. 1968. A study of the non-standard English of Negro and Puerto Rican speakers in New York City. In Phonological and grammatical analysis (Cooperative Research Project 3288, Office of Education, US Dept. of Health), vol. 1. Washington: Columbia University.Search in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 1969. Contraction, deletion, and inherent variability of the English copula. Language 45(4). 715–762. https://doi.org/10.2307/412333.Search in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 1970. The logic of nonstandard English. In Frederick Williams (ed.), Language and poverty: Perspectives on a theme, 153–189. New York: Academic Press.10.1016/B978-0-12-754850-0.50014-3Search in Google Scholar

Lippi-Green, Rosina. 2022 [1997]. English with an accent: Language, ideology and discrimination in the United States, 2nd edn.. London & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

MacDonald, Susan Peck. 2007. The erasure of language. College Composition & Communication 58(4). 585–625. https://doi.org/10.58680/ccc20075924.Search in Google Scholar

Matsuda, Paul Kei. 2013. It’s the wild west out there: A new linguistic Frontier in US college composition. In A. Suresh Canagarajah (ed.), Literacy as translingual practice: Between communities and classrooms, 128–138. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Penn Admissions. 2023. Demographics. https://admissions.upenn.edu/how-to-apply/what-penn-looks-for/incoming-class-profile (accessed 1 June 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Presley, Rachel. 2022. Dis/locating linguistic terrorism: Writing American Indian languages back into the rhetoric classroom. In Brooke R. Schreiber, Eunjeong Lee, Jennifer T. Johnson & Norah Fahim (eds.), Linguistic justice on campus: Pedagogy and advocacy for multilingual students, 58–71. Jackson, TN: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781788929509-005Search in Google Scholar

Rickford, John R. & Sharese King. 2016. Language and linguistics on trial: Hearing Rachel Jeantel (and other vernacular speakers) in the courtroom and beyond. Language 92(4). 948–988. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2016.0078.Search in Google Scholar

Schreiber, Brooke R., Eunjeong Lee, Jennifer T. Johnson & Norah Fahim (eds.). 2022. Linguistic justice on campus: Pedagogy and advocacy for multilingual students. Jackson, TN: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781788929509Search in Google Scholar

Simon, Kaia L. 2022. Audience awareness, multilingual realities: Child language brokers in the first year writing classroom. In Brooke R. Schreiber, Eunjeong Lee, Jennifer T. Johnson & Norah Fahim (eds.), Linguistic justice on campus: Pedagogy and advocacy for multilingual students, 72–86. Jackson, TN: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781788929509-006Search in Google Scholar

Smitherman, Geneva. 1986 [1977]. Talkin and testifyin: The language of Black America. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Smitherman, Geneva. 1999. CCCC’s role in the struggle for language rights. College Composition & Communication 50(3). 349–376. https://doi.org/10.2307/358856.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Zhaozhe. 2022. Autoethnographic performance of difference as antiracist pedagogy. In Brooke R. Schreiber, Eunjeong Lee, Jennifer T. Johnson & Norah Fahim (eds.), Linguistic justice on campus: Pedagogy and advocacy for multilingual students, 41–57. Jackson, TN: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781788929509-004Search in Google Scholar

Weinreich, Uriel. 1953. Languages in contact. In Hugo Steger & Herbert Ernst Wiegand (eds.), Contact linguistics, 709–714. New York: Walter de Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Weyant, James M. 2007. Perspective taking as a means of reducing negative stereotyping of individuals who speak English as a second language. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 37(4). 703–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00181.x.Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, Reid. 2013. What dialect do you speak? A map of American English. Washington Post, 2 December. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/govbeat/wp/2013/12/02/what-dialect-to-do-you-speak-a-map-of-american-english/.Search in Google Scholar

Wolfram, Walt & Stephany Dunstan. 2021. Linguistic inequality and sociolinguistic justice in campus life: The need for programmatic intervention. In Gaillynn Clements & Marnie Jo Petray (eds.), Linguistic discrimination in US higher education, 156–173. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780367815103-9Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Introduction to the special collection on public outreach in linguistics

- To go big, we have to go home: building foundations for the future of community-engaged and public-facing research in linguistics

- Towards a theory of linguistic curiosity: applying linguistic frameworks to lingcomm and scicomm

- Linguistic discrimination and diversity: the pivotal role of linguistics in the University of Pennsylvania’s writing program

- Using constructed languages to introduce and teach linguistics

- “Science is in everything, whether we realize it or not”: using the IPA to encourage interest in the scientific study of language

- Bridging linguistics and high school students: the example of Noorlingvistide keeleklubi in Estonia

- The Linguistics Roadshow

- The Language Science Station at Planet Word: a language research and engagement laboratory at a language museum

- The moving project: exploring language, migration, and identity using participatory podcasting during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Talk about testimony: courtroom dialogue as racialized interactions

- Language science outreach through schools and social media: critical considerations

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Introduction to the special collection on public outreach in linguistics

- To go big, we have to go home: building foundations for the future of community-engaged and public-facing research in linguistics

- Towards a theory of linguistic curiosity: applying linguistic frameworks to lingcomm and scicomm

- Linguistic discrimination and diversity: the pivotal role of linguistics in the University of Pennsylvania’s writing program

- Using constructed languages to introduce and teach linguistics

- “Science is in everything, whether we realize it or not”: using the IPA to encourage interest in the scientific study of language

- Bridging linguistics and high school students: the example of Noorlingvistide keeleklubi in Estonia

- The Linguistics Roadshow

- The Language Science Station at Planet Word: a language research and engagement laboratory at a language museum

- The moving project: exploring language, migration, and identity using participatory podcasting during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Talk about testimony: courtroom dialogue as racialized interactions

- Language science outreach through schools and social media: critical considerations