Abstract

In this article, I examine causal clauses in Polish introduced by the complementizer jako że/iż ‘because’ (lit. ‘as that’). Synchronically, I argue that jako-że/iż-clauses can express distinct reason relations operating on different semantic levels. By focusing on their content interpretation, I provide evidence showing that jako-że/iż-clauses are syntactically integrated adverbial clauses. The main arguments for this claim come from information-structural movement to the left periphery of the matrix clause and quantificational binding. Diachronically, I show that jako could already be used as a causal C-head in Old Polish (up to 1543), and that the declarative complementizer że/iż ‘that’ was incorporated into the causal clause structure in the transition from Old to Middle Polish.

1 Introduction

In Present-Day Polish, causal relations can be expressed by subordinate clauses introduced by different clause-linking elements, for example by ponieważ, bo, jako że, gdyż, or albowiem, all roughly corresponding to the English complementizer because; see (1), where the speaker takes the rain to be the reason for why the matrix subject decides to stay at home.[1]

| Zostaniemy | w | dom-u, | ponieważ / bo / jako że / gdyż / albowiem | pada | deszcz. |

| remain.1pl | in | house-loc | because | fall.3sg | rain |

| ‘We’re going to stay at home because it’s raining.’ | |||||

Not much is known about differences between these subordinate clauses, nor do we know in great detail how they came into being.[2] Skibicki (2007: 27) mentions jako-że-clauses in passing, but she does not offer any analysis. Likewise, Grochowski et al. (1984: 295) note the existence of jako że in a conjunction index, but do not discuss its use. Blümel and Pitsch (2019: 5) observe that the meaning of jako że is opaque, that is, it cannot be calculated from the meaning of its component parts in a compositional way. Markowski (2008: 358) paraphrases it as ponieważ ‘because’. These remarks strongly suggest that a detailed analysis of jako-że-clauses is called for.

The main aim of this article is to examine the synchrony and diachrony of jako-że-clauses. As (2a) and (2b), two examples from crime novels of Remigiusz Mróz, show, these clauses are often used in modern Polish:

| Co | jest | całkiem | zrozumiałe, | jako | że | dziennikarka | miała | w |

| what | be.3sg | totally | understandable | as | that | journalist.f | have.l:ptcp.sg.f | in |

| usta-ch | monet-ę. | |||||||

| lips-loc | coin-acc | |||||||

| ‘Which is totally understandable because the journalist had a coin in her mouth.’ | ||||||||

| (Przew, p. 11) | ||||||||

| Zdawał | sobie | spraw-ę, | że | Edling | jest | odporny | praktycznie | na | ||

| seem.l:ptcp.sg.m | refl.dat | issue-acc | that | Edling | be.3sg | resistant | practically | on | ||

| wszystkie | metody | manipulacyjne, | jako | że | sam | je | stosuje | lub | na | pewnym |

| all | methods | manipulative | as | that | refl | them.acc | use.3sg | or | on | certain |

| etap-ie | życi-a | stosował. | ||||||||

| period-loc | life-gen | use.l:ptcp.sg.m | ||||||||

| ‘[He] realized that Edling is resistant to practically all manipulative methods because he uses them himself or he used them at certain point of his life.’ | ||||||||||

| (Kab, p. 80) | ||||||||||

Synchronically, to my knowledge, no analysis has been proposed so far. This is not surprising because jako że is non-existent as a causal conjunction in other Slavic languages; compare, for example, (3a) for Czech (West Slavic), (3b) for Bulgarian (South Slavic), and (3c) for Russian (East Slavic).

| Zůstaneme | doma, | protože / jelikož / ponděvadž / neboť / *jako že | prší. |

| remain.1pl | home | because | rain.3sg |

| ‘We’re going to stay at home because it’s raining.’ | |||

| (Radek Šimík, pers. comm.) | |||

| Shte | ostanem | vkushti | poneže / zašhtoto / tŭj kato / *kato che | vali | (dŭžd). |

| fut | stay.1pl | at:home | because | rain.3sg | rain |

| ‘We will stay at home because it’s raining.’ | |||||

| (Vesela Simeonova, pers. comm.) | |||||

| My | ostanemsja | doma, | potomu čto / potomu kak / tak kak / *kak čto | idet | dožd’. |

| we | stay.1pl | home | because | go.3sg | rain |

| ‘We’re going to stay at home because it’s raining.’ | |||||

| (Katja Jasinskaja, pers. comm.) | |||||

Remarkably, neither jako že in Czech nor kato che in Bulgarian nor kak čto in Russian can be used to introduce a causal dependency relationship. Instead other conjunctions have to be used.[3] Diachronically, jako-że-clauses constitute an interesting case as well, because jako że literally consists of the relativizer jako ‘as’ and the complementizer że ‘that’ introducing usually complement clauses.[4] In this connection, it is interesting to figure out how the causal meaning comes about, and how jako-że-clauses came into being.

This article is structured as follows. In Section 2, I examine the semantics and syntax of jako-że-clauses in Present-Day Polish. The main focus is on their content interpretation. Section 3 is concerned with the diachrony of jako-że-clauses, whereas Section 4 offers an outline of the diachronic development. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the most important findings.

2 Jako-że-clauses in Present-Day Polish

In this section, I briefly examine the use of jako-że-clauses in Present-Day Polish. In Section 2.1, I give an overview over their possible interpretations and show that they can be interpreted as content, epistemic, or speech act causal clauses. Section 2.2 is concerned with the external syntax of jako-że-clauses, with the main focus on their content interpretation.

Before I examine jako-że-clauses at the syntax-semantics interface, it first needs to be proven that jako że is a frozen complementizer expressing a causal relation. In principle, one could intuitively argue that jako[5] is used as a relativizer (‘as’), whereas że ‘that’ introduces a subordinate clause. This would mean that the causal relation between the matrix clause and the subordinate clause is attributed to a presupposition or an implicature. However, such an analysis cannot be upheld. Consider (4), a corpus example:[6]

| Ma | ponadto | doskonale | dobrany | kolor | włos-ów, | jako | że | nie | widać | zbyt | dużej |

| have.3sg | furthermore | excellently | chosen | color | hairs-gen | as | that | neg | see.infv | too | big |

| różnic-y | między | odrost-ami | a | włos-ami | farbowanymi. | ||||||

| difference-gen | between | roots-inst | and | hairs-inst | dyed | ||||||

| ‘Furthermore, she has an excellent hair color because one cannot see a too big difference between her roots and dyed hairs.’ | |||||||||||

| (NKJP, Dziennik Zachodni, 10 April 2001) | |||||||||||

If jako and że were two independent elements, we should be able to dispense with one of them. This is impossible, though, when a causal relation is expressed:

| *Ma ponadto doskonale dobrany kolor włosów, jako nie widać zbyt dużej różnicy między odrostami a włosami farbowanymi. |

| *Ma ponadto doskonale dobrany kolor włosów, że nie widać zbyt dużej różnicy między odrostami a włosami farbowanymi. 7 |

- 7

This example is correct when że is used as an elaboration marker, but in this case it is not a declarative complementizer. Rather, it is used as a discourse marker; for more details, see Guz and Jędrzejowski (2023).

It straightforwardly follows from (5a) and (5b) that jako and że have to co-occur to express a causal relation between the matrix clause and the subordinate clause. However, it should be kept in mind that Polish also has another declarative complementizer, iż ‘that’, occurring mainly in higher register texts.[8] Compare (6a), a slightly modified version of (4), and (6b), a corpus example:

| Ma ponadto doskonale dobrany kolor włosów, jako iż nie widać zbyt dużej różnicy między odrostami a włosami farbowanymi. |

| Polacy | nadal | uważają, | że | trzęsienia ziemi | im | nie | zagrażają, | jako | iż |

| Poles | still | claim.3pl | that | earthquakes | them.dat | neg | threaten.3pl | as | that |

| kraj | nasz | leży | w | stref-ie | asejsmicznej. | ||||

| country | our | lie.3sg | in | zone-loc | non-seismic | ||||

| ‘Polish people still claim that earthquakes do not threaten them because our country is in a non-seismic zone.’ | |||||||||

| (NKJP, Dziennik Polski, 5 March 2005) | |||||||||

In either case jako and iż also introduce a causal relation between the matrix and the subordinate clause (see also Dunaj 1998: 336). This clearly indicates that a declarative complementizer establishing a causal relation along with jako is not restricted to any particular form. While discussing the synchronic data, I restrict myself to że due to the lack of space, but all synchronic observations made below can be carried over to iż as well.

2.1 Semantics

It is well known that causal relations can be expressed on three cognitive levels. They can operate on the content level, on the epistemic level, or on the speech act level (van Dijk 1977: 68–76; Frey 2016, 2023; Schiffrin 1987: 202; Sweetser 1990: 77; to provide but a few references). As the following examples show, jako-że-clauses can also operate on these three levels.

| Zostaniemy | w | dom-u, | jako | że | pada | deszcz. |

| remain.1pl | in | house-loc | as | that | fall.3sg | rain |

| ‘We’re going to stay at home because it’s raining.’ | ||||||

| Musi | być | teraz | w | dom-u, | jako | że | jego | auto | stoi | przed | garaż-em. |

| must.3sg | be.infv | now | in | house-loc | as | that | his | car | stay.3sg | in:front:of | garage-inst |

| ‘He must be at home now as his car is in front of the garage.’ | |||||||||||

| Jako | że | ciągle | o | to | pytasz, | nie | spotykam | się | już | z | twoją |

| as | that | still | about | this | ask.2sg | neg | meet.1sg | refl | no:longer | with | your |

| córk-ą. | |||||||||||

| daughter-inst | |||||||||||

| ‘Since you still keep asking, I don’t date your daughter any longer.’ | |||||||||||

In the content domain, causal clauses usually encode a reason relation between two events – for example, in (7a), the rain is the reason for staying at home. The core property of these clauses is that the information conveyed in the matrix clause is presupposed, whereas the proposition in the subordination clause is asserted (see Larson 2004: 31–34 for more details and Arsenijević 2021: 13–15 for a similar account):

| We stayed at home because we were playing Scrabble. |

| presupposition: we stayed at home |

| assertion: our staying at home was due to playing Scrabble |

| ∃e[staying at home(x, e) & ∃e’[Cause(e’,e) & playing Scrabble(x, e’)]] |

In (7b), in turn, the speaker provides the reason for why she or he thinks the matrix clause is true. Correspondingly, the speaker takes the car being in front of the garage to be a reasonable argument to assume that the matrix subject is at home. And in (7c), in the speech act domain, the speaker reveals the motivation for why she or he is performing a speech act.

Causal complementizers have been additionally divided into two groups, depending whether or not they convey a non-at-issue meaning. Causal clauses headed by English since, French puisque, and German denn have been claimed to be non-at-issue (e.g., Charnavel 2017, 2020; Scheffler 2013: 50–93), as their content cannot be directly dissented with, nor is their content relevant to the question under discussion (for more details about [non]-at-issueness, see Tonhauser 2012). On the other hand, causal clauses headed by because in English, parce que in French, and weil in German are taken to be at-issue. Jako-że-clauses are clearly at-issue, as their content can be directly dissented with:

| Zostaniemy | w | dom-u, | jako | że | pada | deszcz. |

| remain.1pl | in | house-loc | as | that | fall.3sg | rain |

| ‘We’re going to stay at home because it’s raining.’ | ||||||

| Ale | to | nieprawda, | nie | pada. |

| but | this | untruth | neg | fall.3sg |

| ‘But this is not truth, it is not raining.’ | ||||

In (9), speaker B denies the content of the jako-że-clause by using the demonstrative to ‘this’ with reference to the content of the subordinate clause and by negating it with the noun nieprawda ‘untruth’.

In what follows, I focus on jako-że-clauses operating on the content level, and do not elaborate on the other possible interpretations, as they express different reason relations and constitute distinct clause types; for more details, the interested reader is referred to Frey (2016), Larson (2004), Larson and Sawada (2012), and Morreall (1979).

2.2 Syntax

Although adverbial clauses can be introduced by a large number of adverbial complementizers, they can be divided into three main groups depending on the extent to which they are syntactically integrated into the matrix clause: central (= TP adjuncts), peripheral (= CP adjuncts), and disintegrated adverbial clauses (adjuncts attaching outside the clause structure). Different syntactic criteria help us to keep them apart. If an adverbial clause cannot appear on the right edge of the matrix clause and be part of it, then it must be analyzed as a disintegrated adverbial clause having its own illocutionary force. If, on the other hand, an adverbial clause is part of the matrix clause and can appear in the left periphery of it, then it is reasonable to examine to what extent it is sensitive to material occurring in the matrix clause to determine its integration status. Following Reinhart (1983: 122), I argue that quantificational binding is subject to a surface c-command condition, and adhere to the well-established view that the nominative case is checked in Spec,TP. Consequently, if an adverbial clause allows variable binding, then it is expected to be in the c-command domain of the quantificational phrase: a quantifier can bind an agreeing pronoun occurring in the subordinate clause iff the quantifier c-commands the pronoun (for more details, see Büring 2005: 83–93; Chomsky 1981: 183–230; Enç 1989: 62–64). Now, if an adverbial clause passes this test, then it cannot attach above TP because c-command would not be feasible, leading to the conclusion that the subordinate clause should be analyzed as a central adverbial clause. Table 1 summarizes the classification of adverbial clauses; for more details and tests, the interested reader is referred to Ángantýsson and Jędrzejowski (2023), Frey (2011, 2012, 2016, 2020, 2023), and Haegeman (2003, 2010, 2012). Against this background, we can safely conclude that causal jako-że-clauses operating on the content level are central adverbial clauses because they can occur in the left periphery of the matrix clause, as shown in (10a) and (10b), and because they allow variable binding, seen in (11).

Syntactic typology of adverbial clauses.

| Left periphery of the matrix clause | Variable binding | |

|---|---|---|

| Central adverbial clause | + | + |

| Peripheral adverbial clause | + | – |

| Disintegrated adverbial clause | – | – |

| [ForceP [FocP [CP | Jako | że | lubię | dużo | czytać], | zamówiłem | wczoraj | nowe |

| as | that | like.1sg | much | read.infv | order.l:ptcp.m.1sg | yesterday | new | |

| książki | w | Empik-u]]. | ||||||

| books.acc | in | Empik-loc | ||||||

| ‘Since I like reading a lot, I ordered new books in Empik yesterday.’ | ||||||||

| Jako | że | pewnego | rok-u | wiosna | była | spóźniona | i | robot-y | w |

| as | that | certain | year-gen | spring | be.l:ptcp.sg.f | late | and | work-gen | in |

| pol-u | miał | sporo, | […] | postanowił | pojechać | w | pole. | ||

| field-loc | have.l:ptcp.sg.m | quite:a:lot | […] | decide.l:ptcp.sg.m | go.infv | in | field.acc | ||

| ‘Since the spring came late in a certain year and he had a lot to do, he decided to plant the field.’ | |||||||||

| (Bies, Jak Drozd zarazę przez rzekę przeniósł, p. 27) | |||||||||

| [Każdy | szef]i | jest | zadowolony, | jako | że | jego i | zespół | pracuje | z zapałem. |

| every | boss | be.3sg | happy | as | that | his | team | work.3sg | eagerly |

| ‘Every boss is happy because his team is working eagerly.’ | |||||||||

These two syntactic tests show that content jako-że-clauses adjoin as TP adjuncts. Examples (10a) and (10b) illustrate that information-structural movements above the TP node, for example to FocP, are possible. Furthermore, jako-że-clause allow variable binding, as (11) shows: the quantifier każdy ‘every’ occurring in the Spec,TP of the matrix clause binds the possessive pronoun jego ‘his’ occurring in the subordinate clause – that is, każdy c-commands jego. This is the main argument for the TP adjunction of jako-że-clauses. It therefore follows that jako-że-clauses can be considered neither peripheral nor disintegrated adverbial clauses.

Having briefly examined jako-że-clauses in Present-Day Polish, I now turn to their diachrony. Firstly, I elaborate on the question when causal jako-że-clauses occurred in the history of Polish for the first time. Secondly, it is also interesting to examine how they came into being, as neither jako ‘as’ nor że ‘that’ express a causal meaning in Present-Day Polish on their own.

3 Jako-że-clauses in the history of Polish

In this section, I describe the use of jako-że-clauses in historical periods of Polish. Following Klemensiewicz (2009), Walczak (1999), and Dziubalska-Kołaczyk and Walczak (2010), I distinguish the language stages in the history of Polish shown in Table 2. From now on, I use the abbreviations listed in this table when referring to the individual language periods. I also restrict myself to data from OP and MP, as in NP no language change processes took place that affected the origin or development of the causal complementizer jako że/iż.

Historical stages of Polish.

| Language period | Abbreviation | Time period |

|---|---|---|

| Old Polish | OP | Up to 1543 |

| Middle Polish | MP | 1543–1765 |

| New Polish | NP | 1765–1939 |

| Present-Day Polish | PDP | Since 1939 |

3.1 Etymology

The causal subordinate clause introduced by jako że can be decomposed into two elements that are still available in PDP: the relativizer jako ‘as’, that assigns a case value to its complement, seen in (12), and the declarative complementizer że ‘that’, which introduces canonical complement clauses, as in (13):

| Simon | ciągle | pracuje | jako | szpion. |

| Simon | still | work.3sg | as | spy.nom |

| ‘Simon still works as a spy.’ | ||||

| Agnes | przypuszcza, | że | Simon | jest | szpion-em. |

| Agnes | suspect.3sg | that | Simon | be.3sg | spy-inst |

| ‘Agnes suspects that Simon is a spy.’ | |||||

Not much is known about the history of jako że/jako iż. Brückner (1927) does not mention them at all; he only notes that jako was phonologically reduced to jak (lit. ‘how’). Decyk-Zięba et al. (2008: 54–55) trace jako back to the Proto-Slavic form *jakъ that is still attested in Czech (jako), in Lower Sorbian (ako), in Ukranian (jáko), and in Old Church Slavonic (jako). They also confirm Brückner’s observation that jako has been reduced to jak in MP, due to an accent shift, giving rise to a similar effect in other lexemes (e.g., tamo → tam ‘there’, tako → tak ‘so’, etc.; for more details on such processes in the history of Slavic languages, see Carlton 1991; Kapović 2005). Furthermore, Decyk-Zięba et al. (2008) point out that jako is mainly used as comparative preposition/relativizer that can relate different phrases, for example DPs or CPs, but they are silent about its use in connection with iż(e)/że as an adverbial causal complementizer.[9]

3.2 Old Polish: up to 1543

Jako is an exceedingly frequent element in the oldest stage of Polish. To get a clear picture of how it was used in OP, I extracted and analyzed over 550 examples in which jako occurs. For an overview, the interested reader is referred to Table 3 in Appendix B.

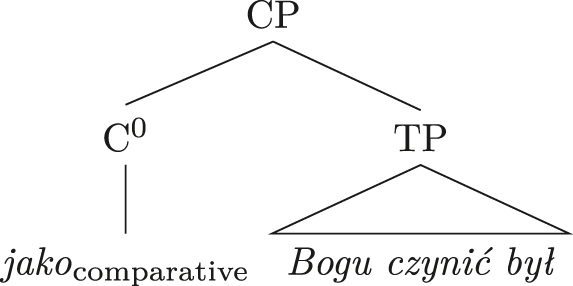

As a comparative relativizer it can relate two XPs, for examples DPs as in (14a) or TPs as in (14b), comparing them as to some manner or degree of some property:

| a | przeztoć | ja | dzisia [DP | tobie] | chwał-ę | jako [DP | Bog-u] | daję |

| and | through:this | I | today | you.dat | glory-acc | as | God-dat | give.1sg |

| ‘and based on this I praise you as God’ | ||||||||

| (KTS, Kazania Gnieźnieńskie, 1420, Kazanie II: Na Boże Narodzenie, 4v) | ||||||||

| i | [TP | nie | dał | jest | on | był | sobie | więce | chwał-y] |

| and | neg | give.l:ptcp.sg.m | be.3sg | he | be.l:ptcp.sg.m | refl.dat | more | glory-gen | |

| jako | [TP | bog-u | czynić | był] | |||||

| as | God-dat | do.infv | be.l:ptcp.sg.m | ||||||

| ‘and he didn’t want to be praised anymore, as he used to do with God’ | |||||||||

| (KTS, Kazania Gnieźnieńskie, 1420, Kazanie II: Na Boże Narodzenie, 5r) | |||||||||

As a wh-word, jako can occur as a manner wh-word introducing finite clauses embedded, for example, under verbs of perceptions, as in (15a). But it can also occur in independent contexts, such as in (15b):

| chtore | słyszeli | i | widzieli, | [CP [Spec,CP | jako] | rzeczono | jest | do |

| who | hear.l:ptcp.pl.vir | and | see.l:ptcp.pl.vir | as | said | be.3sg | to | |

| nich] | ||||||||

| them.gen | ||||||||

| ‘who have heard and seen how they told it them’ | ||||||||

| (KTS, Ewangeliarz Zamoyskich, 2nd half of the 15th century, 3v: 20) | ||||||||

| [CP [Spec,CP | Jako] | może | człowiek | narodzić | się], | gdy | jest | stary? |

| how | can.3sg | human:being | bear.infv | refl | if | be.3sg | old | |

| ‘How can a human being be borne if he is old?’ | ||||||||

| (KTS, Ewangeliarz Zamoyskich, 2nd half of the 15th century, 7r: 4) | ||||||||

These functions are still available in PDP, but mainly with the phonologically reduced form jak, and not with jako. This also holds for the use of jako as a temporal complementizer, seen in (16a), or as a declarative complementizer, as in (16b):

| A | [CP [C0 | jako] | przyszli | do | Salomonowa | kościoł-a], | tamo | było | ||

| and | as | come.l:ptcp.vir | to | Salomon | church-gen | there | be.l:ptcp.sg.n | |||

| piętnaście | stopień | ku | drzwi-am, | tako | dzieciątko | Maryja | wyrwawszy | się | ku | drzwi-om |

| fifteen | step | to | door-dat | so | baby | Mary | came:out | refl | to | doors-refl |

| z | ręk-u | swojej | matk-i | […] | sama | weszła | naprzod | przed | ||

| with | hand-gen | her | mother-gen | […] | alone | come:in.l:ptcp.sg.f | to:the:fore | ahead:of | ||

| swoim | ojce-m | i | przed | swoją | matk-ą. | |||||

| her | father-inst | and | ahead:of | her | mother-inst | |||||

| ‘And when they arrived at Salomon’s church, they saw fifteen steps to the door; the baby Mary went adrift from her mother’s hands and went alone ahead in front of her father and mother.’ | ||||||||||

| (KTS, Rozmyślanie przemyskie, p. 13, lines 12–18) | ||||||||||

| Tedy | my | Idzik-owi | skazalismy | przysiac, | [CP [C0 | jako] | nie | wie, | kto |

| then | we | Idzik-dat | command.l:ptcp.1pl | swear.infv | how | neg | know.3sg | who | |

| ji | uraził]. | ||||||||

| him.acc | insult.l:ptcp.sg.m | ||||||||

| ‘Then, we commanded Idzik to swear that he doesn’t know who insulted him.’ | |||||||||

| (KTS, Kodeks Działyńskich, 1425–1488, p. 35, lines 30–31) | |||||||||

In (16a), the dependent event expressed in the temporal jako-clause is a factual event immediately preceding the main event expressed in the matrix clause. Remarkably, the use of jako as a temporal complementizer is not very frequent in OP. In (16b), in turn, jako is employed as a declarative complementizer instead of że/iż ‘that’ (for more cross-linguistic details, see Legate 2010; Umbach et al. 2022).

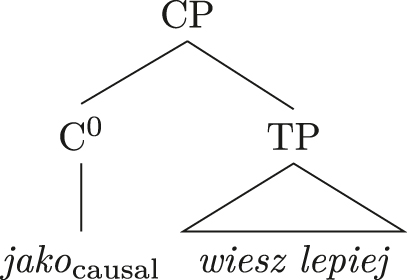

Interestingly enough, in OP jako could be also used as a causal complementizer without being accompanied by a declarative complementizer:

| Matko | Boża, | ciebie | proszę, | [CP [C0 | jako] | wiesz | lepiej] |

| Mother | of God | you.acc | ask.1sg | as | know.2sg | better | |

| ‘Mother of God, I’m asking you, as you know better’ | |||||||

| (KTS, Książeczka Nawojki, 29: 6–8) | |||||||

This option is not available in PDP, neither with jako nor with jak:

| Matko Boża, ciebie proszę, *(jako) / *(jak) / OK(jako że/iż) wiesz lepiej. |

I was not able to find any examples illustrating the use of jako in combination with iż(e)/że, in which the latter follows the former. However, the reverse word order can be attested:

| Iże | jako | to | wy | sami | dobrze | wiecie | i | te-że | wy | o | tem | to | często |

| foc:ptcl | as | this | you | alone | well | know | and | also-foc:ptcl | you | about | this | this | often |

| słychacie, | gdyżci | się | ktoremu | krol-ewi | albo | książę-ciu | syn | narodzi | |||||

| hear.2pl | that | refl | some | king-dat | or | prince-dat | son | be:born.3sg | |||||

| ‘As you know all about this and as you also often hear about this, a son was born to a king or to a prince’ | |||||||||||||

| (KTS, Kazania Gnieźnieńskie, 1420, Kazanie I: Na Boże Narodzenie, 1r) | |||||||||||||

The combination of Iże and jako in (19) does not give rise to a causal interpretation, though. Instead, Iże is to be analyzed as a focus particle, and jako as a comparative relativizer (see also footnote 8; for more details, see Meyer 2017).

3.3 Middle Polish: 1543–1765

The causal pattern attested in PDP is also present in the MP period. The combination of jako and of the declarative complementizer że or iż gives rise to a causal interpretation:

| Inne | przy | tym | wielkiego | walor-u | sztuki | są | bez | cen-y, | tak | dla | dawnośc-i, |

| other | at | the | big | value-gen | pieces | are.3pl | without | price-gen | so | for | antiquity-gen |

| jako | że | onym | podobnych | żaden | dom | dom-owi | austriackiemu | walecznośc-ią | onych | ||

| as | that | those-dat | similar | no | house | house-dat | Austrian | bravery-inst | their | ||

| nabyci-a | nie | zrównia. | |||||||||

| obtaining-gen | neg | equate.3sg | |||||||||

| ‘Comparatively, other pieces of big value are without a price, just for antiquity, because there are no other Austrian houses that would be equal with this one by being able to obtain them.’ | |||||||||||

| (KorBa, 1612, Diariusze, p. 163) | |||||||||||

| I. | Apostat-ę | młodzieńc-a | ś. | Andrzyj | ś. | Grzegorz | srodze | ||

| first | Apostate-acc | youngling-acc | holy | Andrew | holy | Gregory | ferociously | ||

| biczowali | tak | dla | odstępstw-a | jako | iż | dług | wdow-ie | nie | rychło |

| flagellate.3pl.nvir | so | for | deviation-gen | as | that | debt | widow-dat | neg | quickly |

| zapłacił | aż | też | że | się | z | ubogich | żebrak-ów | naśmiewał | |

| pay.sg.l:ptcp.m | foc:ptcl | also | that | refl | from | poor | men-gen | deride.sg.l:ptcp.m | |

| ‘Holy Andrew I and holy Gregory flagellated the youngling Julian the Apostate because he didn’t pay the widow quickly and because he derided poor men.’ | |||||||||

| (KorBa, Hieronim Radziwiłł, 1747–1756, Wielkie zwierciadło przykładów, p. 52) | |||||||||

If only the complementizer jako is used, a comparison is expressed:

| jako | dobrze | namienił | wielki | Kanclerz | Bacon, | każda | Monarchia | nie | mająca |

| as | well | mention.sg.l:ptcp.m | big | Chancellor | Bacon, | every | monarchy | not | having |

| Szlacht-y | jest | szczere | Tyraństwo | ||||||

| nobility-gen | be.3sg | truly | bully | ||||||

| ‘as the great Chancellor Bacon clearly mentioned, every monarchy which does not have a nobility class is a true bully’ | |||||||||

| (KorBa, Hieronim Kłokocki, 1678, Monarchia turecka, p. 87) | |||||||||

I was not able find any examples from MP in which jako would express only a causal meaning without że.

4 Development

4.1 Step 1

Jako fulfills different functions in the OP period. Importantly, it can be used as an adverbial complementizer, introducing comparative clauses, as in (23a), and causal clauses, such as in (24a):

| i | nie | dał | jest | on | był | sobie | więce | chwał-y | jako |

| and | neg | give.l:ptcp.sg.m | be.3sg | he | be.l:ptcp.sg.m | refl | more | glory-gen | as |

| bog-u | czynić | był | |||||||

| God-dat | do.infv | be.l:ptcp.sg.m | |||||||

| ‘and he didn’t want to be praised anymore, as he used to do with God’ | |||||||||

| (KTS, Kazania Gnieźnieńskie, 1420, Kazanie II: Na Boże Narodzenie, 5r) | |||||||||

| Matko Boża, | ciebie | proszę, | jako | wiesz | lepiej |

| Mother of God, | you.acc | ask.1sg | as | know.2sg | better |

| ‘Mother of God, I’m asking you, as you know better’ | |||||

| (KTS, Książeczka Nawojki, 29: 6–8) | |||||

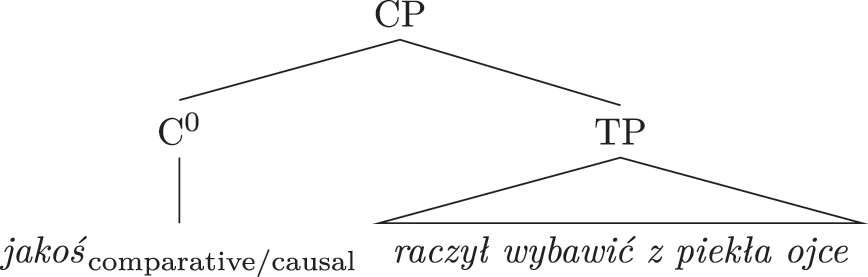

I take the use of jako as a comparative relativizer to be original and to have paved the way for the causal use of jako. Sanfelici and Rodeghiero (2024) observe a related grammaticalization path with respect to siccome ‘because’ in the history of Italian. In my view, jako-że-clauses developed in a similar way. Structurally, no radical changes are involved, as jako is a C-head throughout taking a TP-complement,[10] regardless of what kind of adverbial relation it introduces.[11] What changes is its semantics. Several properties that both comparative and causal clauses have in common underpin their diachronic affinity. Firstly, they express two interrelated events: the event expressed in the subordinate clause can either provide the manner in which the matrix event takes place or entail the reason why the matrix event takes place. Secondly, in both cases the dependent event needs to be factual and temporally contiguous to the main event. Finally, as Sanfelici and Rodeghiero (2024) persuasively show, the change towards a causal reading is additionally favored when the dependent event shares its participants with the main event.

| Jako-ś | raczył | wybawić | z | piekł-a | ojce, | |

| as-2sg.aux | deign.l:ptcp.sg.m | disembarrass.infv | from | hell-gen | fathers.acc | |

| racz | też | wybawić | z | grzech-ów | dusze | nasze. |

| deign.imper.sg | also | disembarrass.infv | from | sins-gen | souls.acc | our |

| ‘As/Since you deigned to deliver our fathers from hell, deign to deliver our souls from sin too.’ | ||||||

| (KTS, Modlitwy Wacława, 104r, 13–14; 104v, 1–2) | ||||||

Due to these properties, ambiguous (comparative vs. causal) cases are unavoidable. In (25a), the event expressed in the subordinate clause can be interpreted either as the manner in which God deigned to deliver the fathers from hell or as the reason why he should deign to deliver our souls from sin. In both scenarios, the event expressed in the subordinate clause is factual and temporally it precedes the event expressed in the matrix clause. Finally, both the matrix clause and the subordinate clause share the same participant: it is an implicit argument God, which is associated with the event of redemption. Sanfelici and Rodeghiero (2024) provide an elegant formal account of the semantic shift from a comparative to a causal interpretation. For the purposes of this article, it suffices to know that this process was completed in the OP period. As (24a) illustrates, pure causal jako-clauses without any other interpretation possibilities exist already in OP.

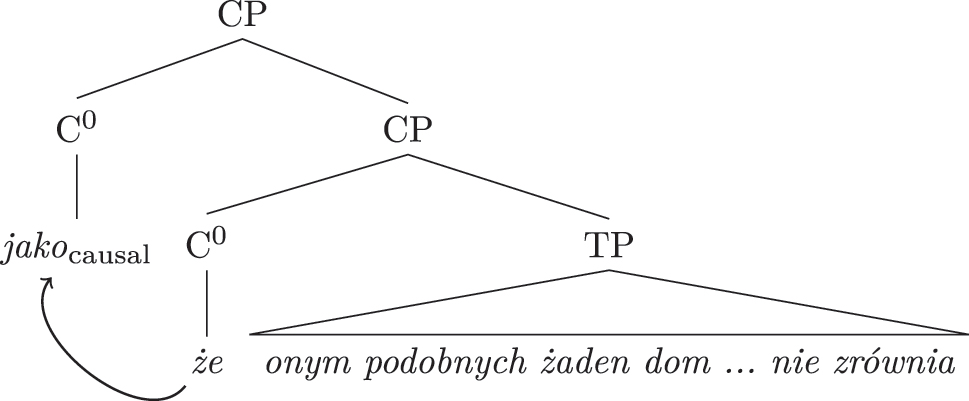

4.2 Step 2

Jako is an ambiguous adverbial C-head. It can introduce comparative, temporal or causal clauses. To disambiguate the adverbial relation expressed by jako, the declarative complementizer że/iż is recruited into the left periphery of the causal clause.[12] The combination jako + że/iż is restricted to a causal meaning, that is, the causal presupposition becomes syntactically encoded:

| Inne | przy | tym | wielkiego | walor-u | sztuki | są | bez | cen-y, | tak | dla |

| other | at | the | big | value-gen | pieces | are.3pl | without | price-gen | so | for |

| dawnośc-i, | jako | że | onym | podobnych | żaden | dom | dom-owi | austriackiemu | ||

| antiquity-gen | as | that | those | similar | no | house | house-dat | Austrian | ||

| walecznośc-ią | onych | nabyci-a | nie | zrównia. | ||||||

| bravery-inst | their | obtaining-gen | neg | equate.3sg | ||||||

| ‘Comparatively, other pieces of big value are without a price, just for antiquity, because there are no other Austrian houses that would be equal with this one by being able to obtain them.’ | ||||||||||

| (KorBa, 1612, Diariusze, p. 163) | ||||||||||

When a jako-clause is used as a causal clause, a dependency relationship between the matrix clause and the subordinate clause emerges. Concretely, the event expressed in the subordinate clause causes the event expressed in the matrix clause to take place. To syntactically mark this subordinate dependency the declarative complementizer, which usually introduces complement clauses, że/iż is added. Sanfelici and Rodeghiero (2024) make a similar observation about siccome ‘because’ followed by che ‘that’ in various Venetian dialects. No such dependency relationship is involved when jako is employed as a comparative relativizer relating two propositions. In this case, both propositions are interrelated with regard to some property giving rise to an equivalence relation, and jako itself is deemed to encode this relation (for similar cases of comparative clauses and more details, see Bücking 2017).

4.3 Step 3

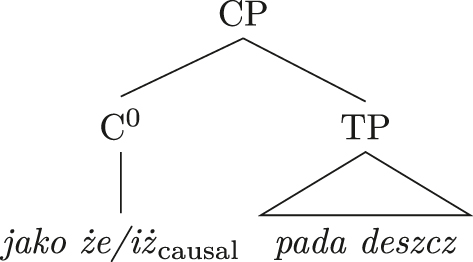

Having syntacticized the pragmatic causal inference, jako-że/iż is a single C-head expressing a causal relation:

| Zostaniemy | w | dom-u, | jako że/iż | pada | deszcz. |

| remain.1pl | in | house-loc | because | fall.3sg | rain |

| ‘We’re going to stay at home because it’s raining.’ | |||||

Jako-że/iż is frozen in the sense that none of its elements can be dropped (see (5a) and (5b)). This is mainly due to the fact that jako itself lost its causal meaning altogether. This process must have happened before the accent shift and the drop of final vowels, as jak ‘how’ can introduce comparative and temporal clauses in PDP, but not causal clauses. Presumably, this led Blümel and Pitsch (2019: 5) to the assumption that the meaning of jako że is opaque.

5 Conclusions

The main objective of this article was to examine the synchrony and diachrony of causal jako-że/iż-clauses in Polish. Synchronically, I discussed evidence showing that jako-że-clauses can express different causal relations, and that they should be analyzed as central adverbial clauses if they operate on the content level. Diachronically, I briefly outlined a grammaticalization path, according to which comparative clauses develop into causal clauses, and which additionally involves head adjunction of two complementizers to syntactically signal a causal dependency relationship. One of the main issues that needs to be addressed in a broader context is the extent to which jako-że/iż-clauses differ from causal clauses headed by ponieważ, bo, gdyż, and albowiem (see (1)), and how they were interrelated in older stages of Polish. I leave these questions open for future research.

Funding source: Daimler und Benz Stiftung

Award Identifier / Grant number: 32-06/18

Acknowledgments

Some parts of this article were presented at the 24th International Conference on Historical Linguistics (ICHL24) at the Australian National University in Canberra (July 2019). For valuable comments, data, and questions, I would like to thank Augustin Speyer, Jadranka Gvozdanović, Katja Jasinskaja, Vesela Simeonova, Radek Šimík, Magdalena Stankiewicz-Dancheva, Igor Yanovich, Constanze Fleczoreck, and two anonymous reviewers who provided productive comments that significantly strengthened this work. I dedicate this paper to Joanna Błaszczak, a wonderful person to spend time with, who encouraged me to work on subordinate clauses in Polish and who is greatly missed. Of course, all errors and inconsistencies are my own responsibility.

-

Conflict of interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. The author is one of the guest editors of the special issue, but was not involved in the reviewing and the decision process of the present article.

-

Research funding: This work was partially supported by the Daimler and Benz Foundation (grant number: 32-06/18), and the German Academic Exchange Service (grant number: 57445292).

Appendix A: Primary sources

The following are the sources used for the primary data in this study, together with the codes used to refer to them in examples:

Bies Andrzej Potocki, 2021, Księga legend i opowieści bieszczadzkich [The storybook of Bieszczady legends and stories], Rzeszów: Carpathia.

Kab Remigiusz Mróz, 2023, Kabalista [The cabalist], Poznań: Filia.

KorBa Elektroniczny korpus tekstów polskich z XVII i XVII w. (do 1772 r.) [Electronic corpus of 17th and 18th century Polish texts (up to 1772)/The Baroque corpus of Polish]: https://korba.edu.pl/query_corpus/.

KTS Korpus tekstów staropolskich do roku 1500 [Corpus of Old Polish texts up to 1500]: https://ijp.pan.pl/publikacje-i-materialy/zasoby/korpus-tekstow-staropolskich/.

NKJP Narodowy Korpus Języka Polskiego [National Corpus of Polish]: http://www.nkjp.pl/.

Przew Remigiusz Mróz, 2023, Przewieszenie [Overhang], 3rd edn., Poznań: Filia.

Below I list all sources that I analyzed for OP. They are available in the KTS corpus for free. The abbreviations are taken from the corpus website. For each source, a PDF file is available, downloadable, and searchable.

Blaz Żywot świętego Błażeja.

Dzial Kodeks Działyńskichi.

EwZam Ewangeliarz Zamoyskich.

Fl Psałterz floriański.

Gn Kazania gnieźnieńskie.

Ksw Kazania świętokrzyskie.

ListTat List chana perekopskiego z r. 1500 do króla Jana Olbrachta.

MW Modlitwy Wacława.

Naw Książeczka do nabożeństwa Jadwigi księżniczki polskiej, tzw. Książeczka Nawojki.

R XXII 230–318 Kazanie na dzień Wszech Świętych.

Sul Kodeks Świętosławówi.

Appendix B: jako (że) in Old Polish

Here, I provide an overview of how jako (że) was used in Old Polish. The data presented in Table 3 have been extracted from over ten texts from the Korpus tekstów staropolskich do roku 1500 (KTS; ‘Corpus of Old Polish texts up to 1500’). The abbreviations used in the table headers are: jakocomparative for the complementizer introducing comparative clauses; jakocausal for the complementizer introducing causal clauses; jako że/iż(e) for the complementizer introducing causal clauses; and jakoother for the relativizer relating two XPs (but not two propositions), the complementizer introducing complement clauses, and so on. I analyzed all attested cases manually by identifying them in the text and interpreting them in particular contexts.

The occurrence of jako (że/iż(e)) in the KTS corpus.

| Source | jako comparative | jako causal | jako że/iż(e) | jako other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blaz | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dzial | 13 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 37 |

| EwZam | 9 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 15 |

| Fl | 36 | 1 | 0 | 171 | 208 |

| Gn | 19 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 26 |

| Ksw | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| ListTat | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| MW | 21 | 1 | 0 | 34 | 56 |

| Naw | 12 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 26 |

| R XXII 230-318 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 50 |

| Sul | 93 | 3 | 0 | 57 | 153 |

| Total | 237 | 7 | 0 | 333 | 577 |

References

Ángantýsson, Ásgrímur & Łukasz Jędrzejowski. 2023. Layers of subordinate clauses: A view from causal af-ϸví-að-clauses in Icelandic. In Łukasz Jędrzejowski & Constanze Fleczoreck (eds.), Micro- and macro-variation of causal clauses. Synchronic and diachronic insights (Studies in Language Companion Series 231), 184–220. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.231.07angSuche in Google Scholar

Arsenijević, Boban. 2021. Situation relatives: Deriving causation, concession, counterfactuality, condition, and purpose. In Andreas Blümel, Jovana Gajić, Ljudmila Geist, Uwe Junghanns & Hagen Pitsch (eds.), Advances in formal Slavic linguistics 2018 (Open Slavic Linguistics 4), 1–34. Berlin: Language Science Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bański, Piotr. 2000. Morphological and prosodic analysis of auxiliary clitics in Polish and English. Warsaw: Uniwersytet Warszawski PhD Dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Bański, Piotr. 2001. Last resort prosodic support in Polish. In Gerhild Zybatow, Uwe Junghanns, Grit Mehlhorn & Luka Szucsich (eds.), Current issues in formal Slavic linguistics (Linguistik International 5), 179–186. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Bielfeldt, Hans Holm. 1961. Altslawische Grammatik. Halle, Saale: Niemeyer.Suche in Google Scholar

Blümel, Andreas & Hagen Pitsch. 2019. Adverbial clauses: Internally rich, externally null. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 4(1). 1–29. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.600.Suche in Google Scholar

Boryś, Wiesław. 2005. Słownik etymologiczny języka polskiego [Etymological dictionary of Polish]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie.Suche in Google Scholar

Brückner, Aleksander. 1927. Słownik etymologiczny języka polskiego [Etymological Dictionary of Polish]. Kraków: Krakowska Spółka Wydawnicza.Suche in Google Scholar

Bücking, Sebastian. 2017. Composing wie wenn: The semantics of hypothetical comparison clauses in German. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 35(4). 979–1025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9364-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Büring, Daniel. 2005. Binding theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511802669Suche in Google Scholar

Carlton, Terence R. 1991. Introduction to the phonological history of the Slavic languages. Columbus, OH: Slavica.Suche in Google Scholar

Charnavel, Isabelle. 2017. Non-at-issueness of since-clauses. Proceedings of SALT 27. 43–58. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v27i0.4127.Suche in Google Scholar

Charnavel, Isabelle. 2020. French causal puisque-clauses in the light of (not)-at-issueness. In Irene Vogel (ed.), Romance languages and linguistic theory 15: Selected papers from the 47th linguistic symposium on romance languages (LSRL47), Newark, Delaware (Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 16), 50–64. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/rllt.16.04chaSuche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding: The Pisa lectures (Studies in Generative Grammar 9). Dordrecht: Foris.Suche in Google Scholar

Decaux, Étienne. 1955. Morphologie des enclitiques polonais (Travaux de l’Institut d’études slaves 23). Paris: l’Institut d’études slaves.Suche in Google Scholar

Decyk-Zięba, Wanda, Krystyna Długosz-Kurczabowa, Stanisław Dubisz, Zygmunt Gałecki, Justyna Garczyńska, Halina Karaś, Alina Kępińska, Anna Pasoń, Izabela Stąpor, Barbara Taras & Izabela Winiarska-Górska. 2008. Glosariusz staropolski: Dydaktyczny słownik etymologiczny [Glossary of Old Polish: An etymological-didactic dictionary]. In Wanda Decyk-Zięba & Stanisław Dubisz (eds.), Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.10.31338/uw.9788323517078Suche in Google Scholar

van Dijk, Teun A. 1977. Text and context: Explorations in the semantics and pragmatics of discourse (Longman Linguistics Library 21). London: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Dunaj, Bogusław (ed.). 1998. Słownik współczesnego języka polskiego [Dictionary of modern Polish]. Warsaw: Przegląd Reader’s Digest.Suche in Google Scholar

Dziubalska-Kołaczyk, Katarzyna & Bogdan Walczak. 2010. Polish. Revue Belge de Philologie et d’Histoire 88(3). 817–840.10.3406/rbph.2010.7805Suche in Google Scholar

Enç, Mürvet. 1989. Pronouns, licensing, and binding. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 7(1). 51–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00141347.Suche in Google Scholar

Frey, Werner. 2011. Peripheral adverbial clauses, their licensing and the prefield in German. In Eva Breindl, Gisella Ferraresi & Anna Volodina (eds.), Satzverknüpfungen: zur Interaktion von Form, Bedeutung und Diskursfunktion (Linguistische Arbeiten 534), 41–77. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110252378.41Suche in Google Scholar

Frey, Werner. 2012. On two types of adverbial clauses allowing root-phenomena. In Lobke Aelbrecht, Liliane Haegeman & Rachel Nye (eds.), Main clause phenomena: New horizons (Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today 190), 405–429. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.190.18freSuche in Google Scholar

Frey, Werner. 2016. About some correlations between formal and interpretative properties of causal clauses. In Ingo Reich & Augustin Speyer (eds.), Co- and subordination in German and other languages (Linguistische Berichte Sonderheft 21), 153–179. Hamburg: Buske.Suche in Google Scholar

Frey, Werner. 2020. German concessives as TPs, JPs and ActPs. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5(110). 1–31. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.763.Suche in Google Scholar

Frey, Werner. 2023. Types of German causal clauses and their syntactic-semantic layers. In Łukasz Jędrzejowski & Constanze Fleczoreck (eds.), Micro- and macro-variation of causal clauses: Synchronic and diachronic insights (Studies in Language Companion Series 231), 51–100. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.231.03freSuche in Google Scholar

van Gelderen, Elly. 2011. The linguistic cycle: Language change and the language faculty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199756056.003.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Grochowski, Maciej, Stanisław Karolak & Zuzanna Topolińksa. 1984. Gramatyka współczesnego języka polskiego – składnia [Grammar of modern Polish – syntax]. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.Suche in Google Scholar

Guz, Wojciech & Łukasz Jędrzejowski. 2023. Polish że ‘that’ as an elaboration marker: Language-internal and cross-linguistic perspectives. In Alessandra Barotto & Simone Mattiola (eds.), Discourse phenomena in typological perspective (Studies in Language Companion Series 227), 167–199. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.227.07guzSuche in Google Scholar

Haegeman, Liliane. 2003. Conditional clauses: External and internal syntax. Mind and Language 18(4). 317–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0017.00230.Suche in Google Scholar

Haegeman, Liliane. 2010. The internal syntax of adverbial clauses. Lingua 120(3). 628–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2008.07.007.Suche in Google Scholar

Haegeman, Liliane. 2012. Adverbial clauses, main clause phenomena, and the composition of the left periphery (Cartography of Syntactic Structures 8). Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199858774.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Kapović, Mate. 2005. The development of Proto-Slavic quantity (from Proto-Slavic to modern Slavic languages). Wiener Slavistisches Jahrbuch 51. 73–111.10.1553/wsj51s73Suche in Google Scholar

Klemensiewicz, Zenon. 2009. Historia języka polskiego [A history of Polish]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.Suche in Google Scholar

Larson, Richard. 2004. Sentence-final adverbs and “scope”. In Keir Moulton & Matthew Wolf (eds.), Proceedings of the north eastern linguistics society annual meeting 34 (NELS 34) at the Stony Brook University, 23–43. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, GLSA Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Larson, Richard K. & Miyuki Sawada. 2012. Root transformations and quantificational structure. In Lobke Aelbrecht, Liliane Haegeman & Rachel Nye (eds.), Main clause phenomena: New horizons (Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today 190), 47–78. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.190.03larSuche in Google Scholar

Legate, Julie Anne. 2010. On how how is used instead of that. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 28(1). 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-010-9088-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Łoś, Jan. 1928. Krótka gramatyka historyczna języka polskiego [A short historical grammar of Polish]. Lwów: K.J. Jakubowski.Suche in Google Scholar

Markowski, Andrzej (ed.). 2008. Wielki słownik poprawnej polszczyzny PWN [The big dictionary of correct Polish]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.Suche in Google Scholar

Meyer, Roland. 2017. The C system of relatives and complement clauses in the history of Slavic languages. Language 93(2). e97–e113. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2017.0032.Suche in Google Scholar

Migdalski, Krzysztof. 2016. Second position effects in the syntax of Germanic and Slavic languages. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego.Suche in Google Scholar

Morreall, John. 1979. The evidential use of because. Papers in Linguistics 12(1–2). 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351817909370469.Suche in Google Scholar

Pisarkowa, Krystyna. 1984. Historia składni języka polskiego [Historical syntax of Polish]. Wrocław: Ossolineum.Suche in Google Scholar

Reinhart, Tanya. 1983. Anaphora and semantic interpretation. London: Croom Helm.Suche in Google Scholar

Sadnik-Altzetmüller, Linda & Rudolf Altzetmüller. 1955. Handwörterbuch zu den altkirchenslavischen Texten. ‘s-Gravenhage: Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Sanfelici, Emanuela & Sira Rodeghiero. 2024. From comparative to causal relations: The case of siccome ‘because’ in the history of Italian. Linguistics Vanguard 10. 1–13 Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2021-0121.Suche in Google Scholar

Scheffler, Tatjana. 2013. Two-dimensional semantics: Clausal adjuncts and complements (Linguistische Arbeiten 549). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110302332Suche in Google Scholar

Schiffrin, Deborah. 1987. Discourse markers (Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics 5). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Skibicki, Monika. 2007. Polnische Grammatik. Hamburg: Buske.Suche in Google Scholar

Sonnenhauser, Barbara. 2015. Functionalising syntactic variance declarative complementation with kako and če in 17th to 19th century Balkan Slavic. Wiener Slavistisches Jahrbuch 3(1). 41–72.Suche in Google Scholar

Sweetser, Eve. 1990. From etymology to pragmatics: Metaphorical and cultural aspects of semantic structure (Cambridge Studies in Linguistics 54). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511620904Suche in Google Scholar

Tonhauser, Judith. 2012. Diagnosing (not-)at-issue content. Semantics of Under-Represented Languages of the Americas 6. 239–254.Suche in Google Scholar

Trunte, Nikolaos. 2005. Ein praktisches Lehrbuch des Kirchenslavischen in 30 Lektionen: Zugleich eine Einführung in die slavische Philologie. Band 1: Altkirchenslavisch. Munich: Otto Sagner.Suche in Google Scholar

Umbach, Carla, Stefan Hinterwimmer & Helmar Gust. 2022. German wie-complements: Manners, methods and events in progress. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 40(1). 307–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-021-09508-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Vondrák, Wenzel. 1928. Vergleichende slavische Grammatik. Vol. 2: Formenlehre und Syntax. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.Suche in Google Scholar

Walczak, Bogdan. 1999. Zarys dziejów języka polskiego [An outline of the history of Polish grammar]. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.