Abstract

This profile of the Pahoturi River language family of southern Papua New Guinea draws from extensive fieldwork on Idi [ISO 639-3: idi] and Ende [kit] – two of six varieties comprising this family – and brief surveying of the other four, which we illustrate in print for the first time. We present the first typological treatment of Pahoturi River in pursuit of shining more light on this understudied corner of the linguistic landscape. This profile is organized into two parts: first, we present sections on the basic structures and systems of Pahoturi River, illustrated with examples from across the family and supplemented with descriptions of Idi and Ende as relevant. From our preliminary data on the four other varieties, we gather that they are similar to Idi and Ende in many respects, but more investigation is warranted. Second, we provide an in-depth treatment of the verbal complex of Idi and Ende. We highlight two intriguing aspects of these complex systems – analytic constructions and ditransitive indexing – that distinguish the Pahoturi River family and the linguistic region of southern New Guinea.

1 Introduction[1]

This article is a profile of the Pahoturi River language family (PR) of southern New Guinea and is split into two parts. First, Sections 1–5 detail what is known about the family from a typological perspective, covering important descriptive characterizations. Section 1 provides an overview of the family; Section 2 describes PR phonology and prevalent phonological processes; Section 3 highlights PR nominal morphology; Section 4 discusses the PR verbal complex, which exhibits complex patterns at multiple levels in the structure; and Section 5 provides an overview of PR syntax, with a focus on argument alignment.

The second part of the paper, Section 6, presents an in-depth analysis of two aspects of the PR verbal construct, specifically Idi analytic constructions and Ende ditransitive indexing. These are introduced below.

The Idi sentence in (1) exemplifies a typical analytic construction in PR languages, composed of an uninflecting analytic stem (yéndhpä)[2] and an auxiliary element hosting all inflectional materials (gagn).[3] This type of verbal construction contrasts with synthetic constructions, which only contain an inflected synthetic stem (see [2] for an example). Curiously, analytic stems also function as nominals when bearing case clitics, calling into question whether these complex predicates are light verb or auxiliary verb constructions. Section 6.1 argues for the auxiliary analysis.

Turning to Ende ditransitive indexing, we find that in PR verbal complexes, four morphemes show object-oriented indexation. These four morphemes invariably index the direct object in monotransitives, as shown by the subscript Os in (2). However, these same morphemes can index either the recipient or the theme in ditransitive constructions and the choice is sensitive to both an animacy and a number hierarchy. Section 6.2 provides a comprehensive discussion.

| Bibi | … | eka de | ddob | obo | kollmällang de |

| bibi | … | eka=de | ɖ͡ʐob | obo | koɽməɽ=aŋ=de O |

| you all (2nsg.nom) | … | story=acc | some | his (3sg.poss) | follow=agt=acc |

| nälläntmenyaemeyo . | |||||

| n- O ə- O ɽənt -meɲ O -ajm O -ejo | |||||

| fut.3plO-3plO-tell-iii.plO-nsg>pl-fut.2nsgA | |||||

| ‘You all will go and tell his other followers the story.’ | |||||

| Ende (Kurupel (Suwede) and Warama 2009: ln. 855) | |||||

1.1 Introduction to the family

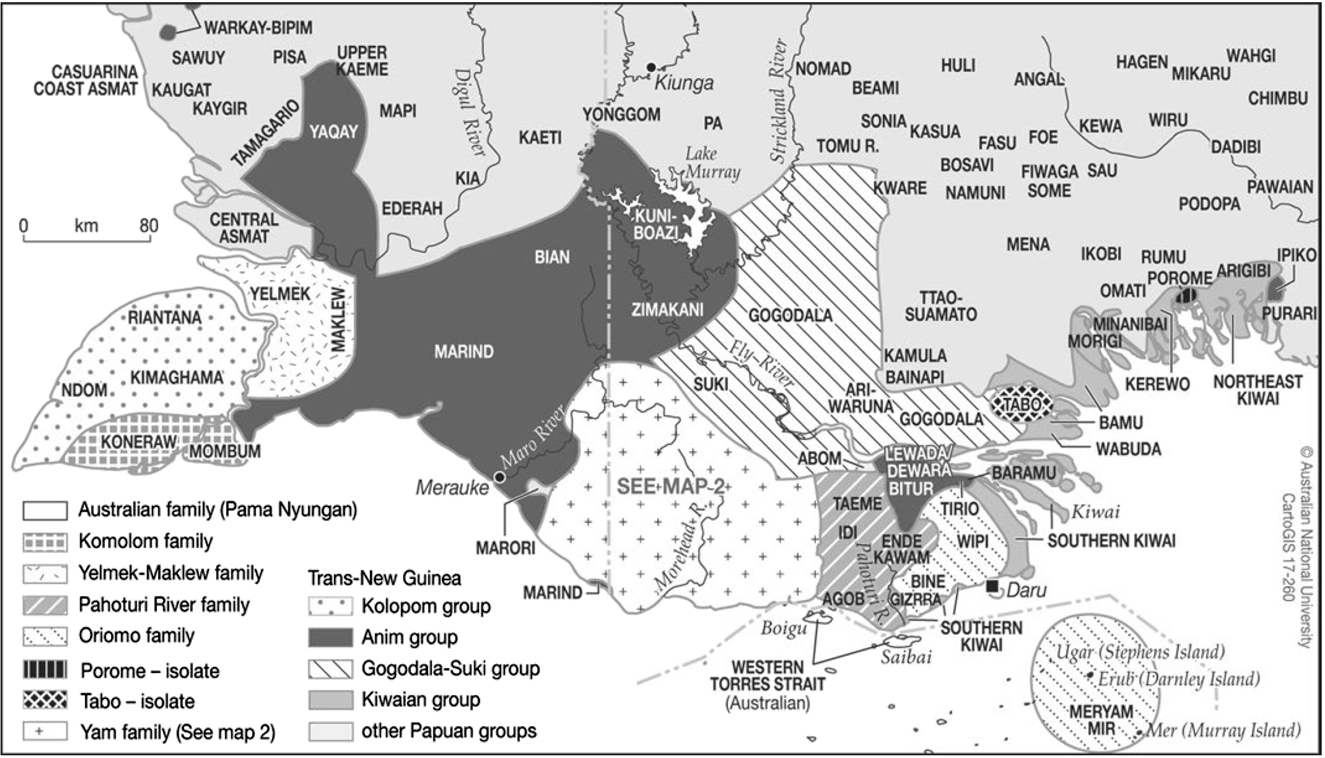

Pahoturi River is an independent family spoken in the South Fly area of southern New Guinea, a region remarkable for its linguistic diversity with eight unrelated phyla (Evans 2012: and see Figure 1). The area boasts many unique characteristics, including (i) a high degree of egalitarian multilingualism, (ii) a system of verbal morphology in which information is distributed, constructive, and cumulative, and (iii) complex tense, aspect, and number systems (Evans et al. 2018a). PR-speaking communities have extensive social relationships with speakers of several distinct language families: Yam to the west, Anim and Gogodala-Suki (Trans-New Guinea) to the north, Oriomo to the east, and Pama-Nyungan (Australian) to the south.

Languages of southern New Guinea (Evans et al. 2018a: 642).

Previous classification attempts have disagreed about how to group PR within a broader family. For example, Wurm (1975: 328) places PR in a Trans-Fly stock, part of the Trans-New Guinea phylum, while Ross (2005: 30) groups PR with Yelmek-Maklew and Morehead-Maro (Yam) in a South-Central Papuan group (non-Trans-New Guinea). Evans and colleagues deem the above classifications tenuous and instead propose five maximal clades for the region: PR, Komolom, Yelmek-Maklew, Tabo, and Yam (2018a: 641–643).

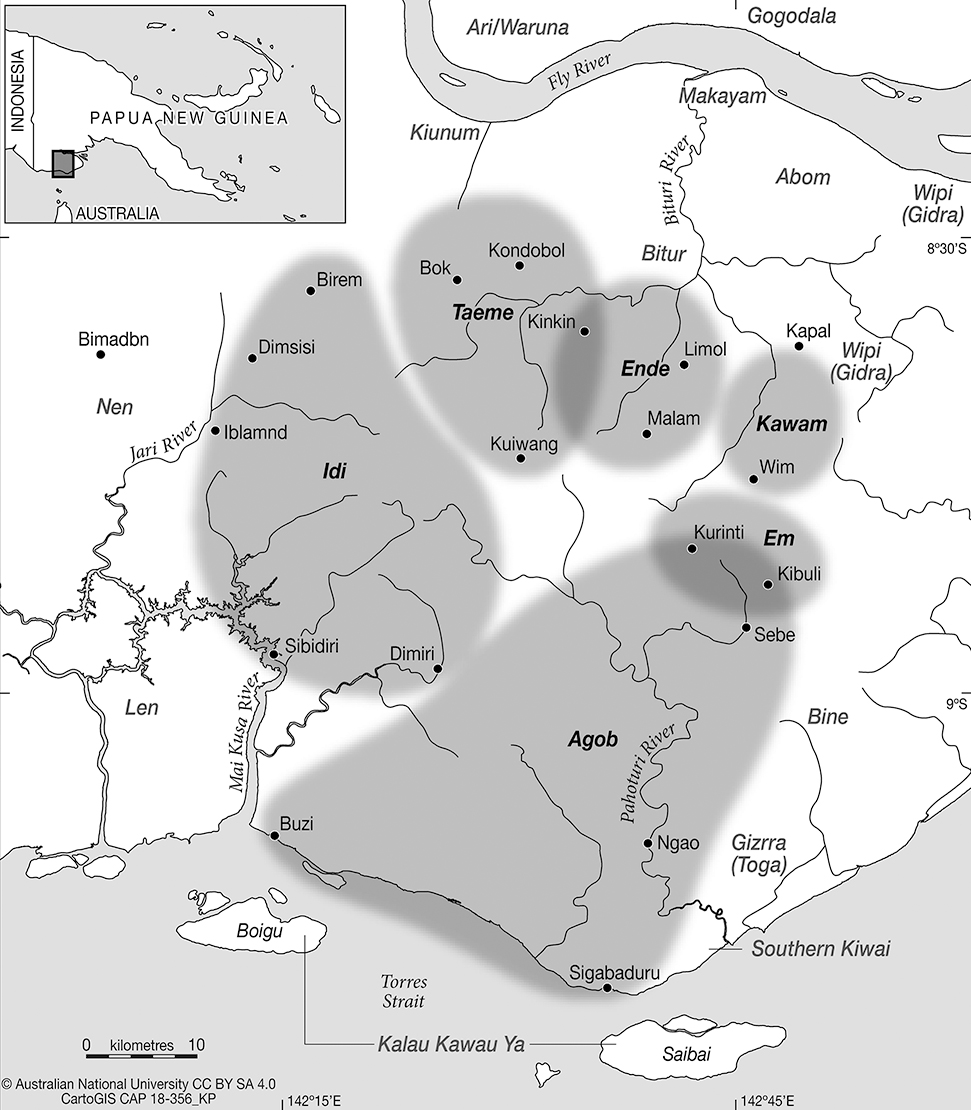

PR consists of at least seven named language varieties: Agob, Em, Ende, Idi, Idzuwe (not currently spoken), Kawam, and Taeme (see Figure 2). An eighth variety called Idan, brought to our attention in 2022 by speaker Bomso Maikong, is actively spoken in Kuiwang and surrounding areas and may be closely related to Taeme (Scanlon, p.c.). This list is longer than in prior sources (for example, Evans et al. 2018a; Lindsey 2017, 2019) as more conversations with community members have taken place. The family was once more internally diverse; speakers can recall the loss of some varieties due to shifts in clan position and composition, even in recent history (see Zakae 2018, ln. 189; Kurupel (Suwede) 2018b, ln. 140–146; Bewag 2018, ln. 112).

South Fly villages with predominant Pahoturi River speaker populations.

We use the term language varieties to refer to each of the communicative systems considered distinct by speakers and remain agnostic to the divide between language and dialect. While we are comfortable classifying Idi and Ende as distinct languages given their numerous lexical, morphological, and phonemic differences, further classifications within the family require more data. Traditionally, PR has been treated as a dialect continuum, with Idi and Taeme at one end and Agob and Ende at the other (Eberhard et al. 2019). Comparative data suggest that Kawam and Em align closer to Agob and Ende, as we present below.

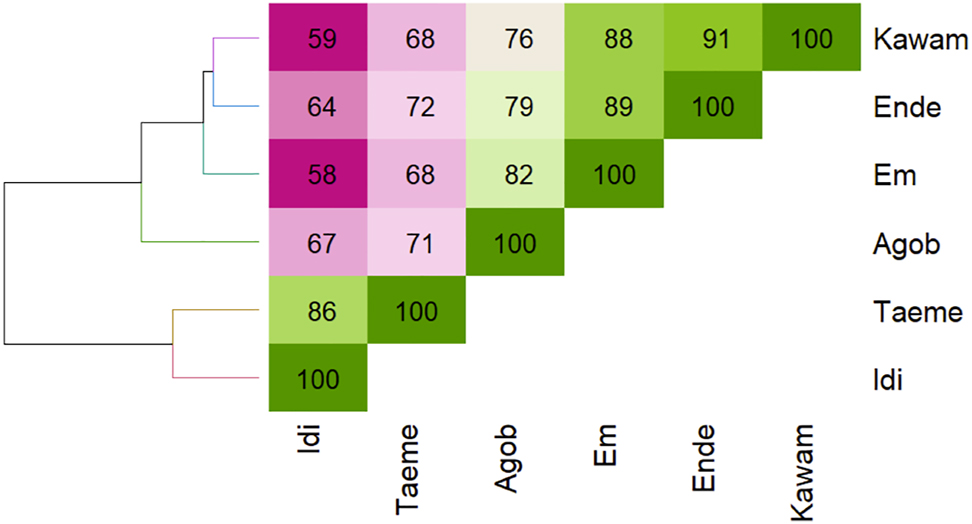

To calculate shared vocabulary among the varieties, we collected wordlist data using the Yamfinder survey (Carroll et al. 2016; Lindsey 2017) and performed a pairwise comparison analysis on all lexemes by counting cognates within each lexical concept (Ellison et al. 2017).

In Figure 3, the tree on the left indicates a first-order split between the western (Idi and Taeme) and eastern (Agob, Em, Ende, and Kawam) varieties. Idi and Taeme share 86% of their lexicon (as cognates), while Kawam and Ende share 91%. Em patterns more closely with Ende and Kawam, followed by Agob. The low numbers in the leftmost column indicate that Idi diverges the most from the eastern varieties, perhaps due to contact with Yam languages to the west.

Percentage of shared cognates in Yamfinder across six PR varieties.

We may see more divergences between the varieties when we elicit a broader lexical set from villages where Kawam, Agob, Em, and Taeme are spoken. The Yamfinder wordlist includes basic concepts, which we predict would be less susceptible to change (Swadesh 1955; Bergsland and Vogt 1962; but cf. Haspelmath 2008). Thus, these results represent conservative similarity metrics.

2 Phonology

Table 1 organizes the consonant inventories of the PR varieties, based on descriptive fieldwork and lexical surveys.[5] This collective inventory is striking for Papuan languages (cf. Foley 2000), especially because it includes three retroflex and four liquid consonants, but is not unusual for the region. The labialized velars, retroflex series, and syllable-initial velar nasals are also observed in—or can be reconstructed for—nearby Anim and Yam (Evans et al. 2017; Rogers 2021).

Pahoturi River consonant inventories.

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Labial velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | k͡p ɡ͡ba | |||

| Affricate | t͡ʃ d͡ʒb | ʈ͡ʂ ɖ͡ʐc | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Fricative | s z | ||||||

| Tap or flap | ɾ | ɽd | |||||

| Approximant | j | w | |||||

| Lateral approx. | l | ʎe |

-

aLabialized velar plosives have only been observed in Idi and Taeme. They may be realized without a labial closure (i.e. [kʷ] and [ɡʷ]). bPost-alveolar affricates are found in Kawam, corresponding with the retroflex affricates in other varieties. cRetroflex obstruents have been observed in all PR varieties except Kawam. dThe retroflex flap is found in Agob, Em, and Ende. ePalatal laterals have been observed in Idi and Taeme.

All varieties contain oral plosives at bilabial, alveolar, and velar places of articulation. The retroflex obstruents occur in all varieties except Kawam and alternate between a stopped and affricated manner of articulation.[6] In Kawam, they are realized as palato-alveolar affricates (Chon and Lindsey 2022).

Idi and Taeme have labialized velar plosives, variably produced with both bilabial and velar closures or with just one velar closure. Labial-velar plosives are also found in Yam, of which Idi is the closest neighbor. In the eastern varieties, cognates that have labialized velars in the western varieties have sequences of velar stops and rounded vowels (Brickhouse and Lindsey 2021).

The contemporary PR varieties have four liquids. An alveolar trill/tap (/r/ or /ɾ/) and an alveolar lateral (/l/) are observed universally. A retroflex flap (/ɽ/) is observed in Ende, Agob, and Em, and a palatal lateral (/ʎ/) is observed in Taeme and Idi. Table 2 presents a reconstruction analysis of these liquids for proto-PR.

Pahoturi River liquid inventories (Evans et al. 2019).

| Proto-PR | Idi | Taeme | Kawam | Ende | Em | Agob |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *r | r | r | r | r | r | r |

| *l | l | l | l | l | l | l |

| * ʎ | ʎ | ʎ | l | l | l | l |

| *ɽ | l | l | r | ɽ | ɽ | ɽ |

| *ʀ | l | ʎ | r | ɽ | ɽ | ɽ |

All varieties have high and mid front unrounded and back rounded vowels (/i, e, u, o/), one low central vowel (/a/) and two mid central vowels of varying qualities. All except Ende have the low front vowel /æ/ (see Table 3). This inventory resembles that of nearby Nen, which contains six full oral vowels (/i, e, u, o, a, æ/) and two central vowels (/ɪ, ə/) with limited distributions (Evans and Miller 2016). In contrast, nearby Bitur (Trans-New Guinea) only has five phonemic vowels (/i, e, u, o, a/) and no central vowels (Rogers 2021). The locations where Nen and Bitur are spoken are represented in Figures 1 and 2.

Pahoturi River vocalic inventories.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| Mid | e | (two central vowels) | o |

| Low | æa | a |

-

aObserved in all varieties except Ende.

2.1 Phonological processes

PR languages exhibit an interesting vowel harmony pattern, especially as it pertains to the ventive directional/associated motion systems (Gast 2017a; Reed and Lindsey 2021). For Idi, Gast (2015a) and Schokkin and colleagues (2021) categorize the vowels into a [-light] set (/a, e, o, ə/), and a [+light] set (/æ, i, u, ɪ/). [light] is a lexical feature of stems, and vowel harmony leads to systematic alternations in bound forms, for example in the nominal clitics (discussed in Section 3). In (3), the [−light] stem mangg ‘brother’ takes the [−light] allomorph of the core clitic =a, whereas the [+light] stem sémbl ‘pig’ takes the [+light] allomorph =ä.

| The core clitic =a harmonizes to =ä after [+light] words, like sémbl ‘pig’. | |||

| Bo | manggmangga | sémblä | ybdheo. |

| bo | maŋɡ∼maŋɡ=a | sɪmbl=æ | jəbəɖeo |

| my (1sg.poss) | pl∼brother=core | pig=core | kill.rem.3nsg>3sg |

| ‘My brothers killed the pig.’ | |||

| Idi (Ado 2014: ln. 32) | |||

In contrast, Lindsey identifies two types of assimilatory vowel processes in Ende. The global harmony pattern corresponding with Idi’s [light] pattern is akin to a progressive prefix- or stem-controlled height-based pattern in Ende, in which high vowels (/i, ɪ, u/) trigger raising of mid vowels (/e, o/). This is illustrated in (4) where the nominals lla ‘person’ and män ‘girl’ take the mid-vowel allomorph of the accusative clitic =de, while llɨg ‘boy’ takes the high vowel allomorph =di. The second process noted in Ende is a regressive stem-controlled total assimilation pattern affecting some verbal prefixes. For more detail, see Lindsey (2019: 190) and Reed and Lindsey (2021).

| Accusative =de harmonizes to =di after words with high vowels like llɨg ‘boy’. | |||||

| Ngäna | ako | mɨnyi | däbe | lla de | ttättle |

| ŋəna | ako | mɪɲi | dəbe | ɽa=de | ʈʂəʈʂle |

| my (1sg.nom) | also | fut | that | person=acc | correct |

| dägagalle, | män de , | o | ll ɨ g di . | ||

| dəɡaɡaɽe | mən=de | o | ɽɪɡ=di | ||

| aux.rem.hab.3sg>3sg | girl=acc | or | boy=acc | ||

| ‘I would correct those people, the girls or the boys.’ | |||||

| Ende (Bewag 2018: ln. 207) | |||||

All varieties show evidence of floating nasal patterns (Lindsey 2019: chap. 3) involving a nasal consonant that appears before and assimilates in place to the leftmost non-initial obstruent in the word. For example, compare the positioning of the velar nasal ng before the velar stop in the Kawam root chongg ‘to give’ (5) and the more left position of the now alveolar nasal n in the prefixed root nchog (6).

| Infinitival form of chongg ‘to give’: chongg | |||||

| Bo | deyarɨn | ibo | chäm | chongg e. | |

| bo | dejarən | ibo | t͡ʃæm | t͡ʃoŋɡ=e | |

| he (3sg.nom) | come.rem.ven.3sgA | us (1nsg.incl.dat) | life | give=all | |

| ‘He came to give us life.’ | |||||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 10:45) | |||||

| Inflected form of chongg ‘to give’: -nchog- | |||

| Ngɨna | bäbire | minyi | ba nchog . |

| ŋəna | bæbire | miɲi | ba-nt͡ʃoɡ |

| I (1sg.nom) | you all (2nsg.dat) | will (fut) | fut.2sgO-give |

| ‘I will give it to you.’ | |||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 6:23) | |||

Ende, Kawam, Em, and Agob allow floating nasals before voiceless and voiced obstruents. Idi and Taeme only allow these before voiced obstruents. Speakers indicate that prenasalization is absent in word-initial position, though it is weakly audible and often visible in the acoustic signal.

Other phonological processes within PR have been treated to varying degrees for Idi and Ende, most notably infinitival reduplication (Lindsey 2019: sec. 4.2) and phonologically-conditioned allomorphy in many of the nominal clitics and the verbal morphology. Stress, tone, and intonational prominence do not play significant roles in these phonological systems, as is typical for the region (Evans et al. 2018a).

A great deal of phonetic variation has been observed across the languages. Free variation of the voiced alveolar fricative /z/ ([ z, ʒ, d͡z, or d͡ʒ]) is a regional feature, observed also in Yam, Trans-New Guinea, and Oriomo (Brown et al. 2021; Kashima 2021; Lindsey 2021a; Rogers 2021; Schokkin et al. 2021). Two phonetic variables that have been studied extensively for both Idi and Ende include the variable realization of the retroflex obstruents as stops or affricates (Strong et al. 2020, 2022) and the variable deletion of /n/ in verb-final position (see Schokkin 2021b; Lindsey 2021b).

3 Nominal morphology

In contrast to the verbal morphology (see Section 4), nominal morphology is quite transparent, comprising a few derivational suffixes and 15 stacking phrasal case clitics (see Table 4). Reduplication and compounding are attested as derivational processes. Number coding can be categorized as a split system (Corbett 2000: 122–123), whereby part of the nominal class (pronouns and kinship terms) distinguish singular from nonsingular (the former by suppletion, the latter by reduplication), while the rest of the nominal class does not inflect for number. In such cases, number may be indexed in the verb or by a reduplicated adjective.

Nominal case clitics in Em (Bolet 2017b; Munu 2018).

| Semantic role | Form |

|---|---|

| Nominative | =da (sg), =ya (nsg) |

| Accusative (patient) | =de |

| Dative (recipient, beneficiary) | =bélle (sg), =bira (nsg) |

| Instrumental, comitative | =allong |

| Possessor | =bo (sg) |

| Distant possessive | =bo (sg) |

| Animate locative | =bo sére=me |

| Inanimate locative | =me |

| Animate allative | =bo sére |

| Inanimate allative | =we |

| Animate ablative | =bo sér=att |

| Inanimate ablative | =(w)att |

| Perlative | =dae |

| Proprietive | =n |

| Privative | =meny |

| Restrictive | =dae |

| Similative | =ingoll |

| Purposive | =ma |

3.1 Pronominal paradigms

Pronominal paradigms distinguish three persons and two numbers and feature a clusivity contrast in the first-person forms. Pronoun sets include nominative, accusative, dative, possessive, past possessive (source), restrictive, and emphatic. The patterns uphold Cysouw’s (2002) generalizations that pronominal paradigms that distinguish clusivity should not exhibit any person syncretism in the singular (i.e., 1sg = 2sg) or in the nonsingular. Only Taeme and Idi exhibit number syncretism in the nominative second and third persons (i.e., 2sg.nom = 2nsg.nom) and Agob in the accusative second person (i.e., 2sg.acc = 2nsg.acc). Curiously, Idi’s first-person pronouns differ from the rest of the family, with similarities to third person. Full tables organizing pronouns for all varieties are listed in Appendix B.

Nominative pronouns are used for intransitive subjects and transitive agents, while accusative pronouns are used for transitive objects. Dative pronouns may be used for recipients of ditransitive clauses, or even for affected parties, such as beneficiaries or maleficiaries. Example (7) shows a first person dative pronoun in the beneficiary sense in Agob.

| Dative pronouns can be used to introduce beneficiaries. | ||||

| Ngémlle | ngomo | yae | Kuruntti me | gozegan. |

| ŋəmɽe | ŋomo | jaj | kurunʈ͡ʂi=me | ɡozeɡan |

| me (1sg.dat) | my (1sg.poss) | mother | Kurunty=loc | birth.rem.3sg>1sg |

| ‘I was born in Kurunty.’ (lit. ‘My mother birthed me in Kurunty.’) | ||||

| Agob (Billy 2015: ln. 13) | ||||

Reflexive pronouns are created by using the possessive pronoun with a word referencing self or the body, like zaga (Ende ‘self’) or ddägane (Taeme ‘body’), as shown for Taeme (8). Reciprocal pronouns are created by reduplicating the possessive pronouns, as shown for Taeme (9).

| Reflexive pronoun constructions are comprised of the possessive pronoun and a word meaning ‘self’ or ‘body’. | |||

| Ngén | ngémo | ddagane | gwatérépenen. |

| ŋən | ŋəmo | ɖ͡ʐaɡane | ɡʷa-tərəpen-en |

| I (1sg.nom) | my (1sg.poss) | refl | refl.rem-cut-1sgA |

| ‘I cut myself.’ | |||

| Taeme (Tama 2019) | |||

| Reciprocal pronouns are reduplicated forms of the possessive pronouns. | |

| Bo | oba∼oba |

| bo | obaoba |

| they (3.nom) | themselves (3nsg.poss∼3nsg.poss) |

| gwatérépeneyo. | |

| ɡʷa-tərəpen-ejo | |

| refl.rem-cut-3nsgA | |

| ‘They cut each other.’ | |

| Taeme (Tama 2019) | |

3.2 Nominal clitics (case marking)

A set of at least 15 case clitics can be identified, covering core grammatical cases and all other case morpheme functions (e.g., adnominal, referential and complementizer) attested in Dench and Evans (1988). The case clitics observed in Em are listed in Table 4 and exemplified in Appendix C. These clitics may be hosted by any nominal, a class including nouns (e.g., Ende ine ‘water’), property nouns functioning as either a noun or an adjective (e.g., mer ‘good, goodness’), and closed subclasses of adjectives (e.g., ulle ‘big’), locational nominals (e.g., ik ‘inside’), and quantifiers (including numerals and personal and interrogative pronouns). Differential marking of animate referents is common, with languages showing differential forms for most of the spatial cases (see Table 4).

Some case clitics also occur on non-finite verbs when these function as clause complements, but in these cases, they indicate different semantic roles. For example, in Ende the clitic =me indicates a locative argument when following a nominal (e.g., ma me ‘in the house’), but simultaneity when following a non-finite verb (e.g., kängkäl me ‘while climbing’). On the other hand, the purposive clitic =ma has the same general meaning whether following a nominal (e.g., up ma ‘(going) for bananas’) or a non-finite verb (e.g., tudi ma ‘(going) for fishing’). There is no overt nominalization marker differentiating a non-finite verb form when it is used with case clitics from when it is used as the main predicate in a clause.

Case clitics are generally obligatory, adjoining to the rightmost element of the phrase, and have scope over the whole phrase. In cases of a split noun phrase (NP), the case clitic may appear twice. For example consider the following accusative-marked noun phrases in which the adjective sisor ‘new’ precedes the noun (10), follows the noun (11), and is split from the noun (12). In all cases, the accusative clitic =de follows the rightmost element in the phrase.

| Ibi | ibra | minyi | ttongo | sisor | bikwem de |

| ibi | ibra | mɪɲi | ʈoŋo | sisor | bikwem=de |

| we (1nsg.incl.nom) | for us (1nsg.incl.dat) | fut | a | new | fireplace=acc |

| ako | bangeseya. | ||||

| ako | baŋeseja | ||||

| then make.fut.1nsgA | |||||

| ‘Then we will make ourselves a new fireplace.’ | |||||

| Ende (Warama 2017: ln. 64) | |||||

| Abo | bongo | ttongo | ma | sisor de | nogo. |

| abo | boŋo | ʈoŋo | ma | sisor=de | noɡo |

| must | you (2sg.nom) | a | house | new=acc | build.fut.2sg>3sg |

| ‘You must build a new house.’ | |||||

| Ende (Warama 2017: ln. 13) | |||||

| Ako | ai | dan | ttongo | mälla de | bällädän |

| ako | ai | da=n | ʈoŋo | məɽa=de | bəɽədən |

| again | good | int.dem=cop.prs.sgS | a | woman=acc | marry.fut.3sg>3sg |

| sisor de. | |||||

| sisor=de. | |||||

| new=acc | |||||

| ‘Then it is okay for him to marry a new woman.’ | |||||

| Ende (Zakae 2016: ln. 7) | |||||

While most PR languages exhibit nominative-accusative alignment in their core argument marking, Idi differs in that nominatives and inanimate patients share the same clitic, with only animate patients marked differently from agents and subjects. Appendix C provides an inventory of case clitics in Idi.

3.3 Deictics

PR languages have elaborate demonstrative systems. Two formatives are clearly recognizable across the family: g- with proximate distance semantics, and d- with intermediate distance semantics. Two Em proximal demonstratives, ge and génymae are shown (13), while one intermediate demonstrative, do, is shown (14).

| Proximal demonstratives in Em | ||||||||

| Ge | ge | ge , | dirom da | guddellon | ge | ge | ge | |

| ɡe | ɡe | ɡe | dirom=da | ɡuɖ͡ʐeɽon | ɡe | ɡe | ɡe | |

| here (prox.dem) | here | here | cassowary=nom | stand.rem.3sgS | here | here | here | |

| génymae | dugabollon | ge . | ||||||

| ɡəɲ=maj | duɡaboɽon | ɡe | ||||||

| here=loc | stand.rem.3sgS | here | ||||||

| ‘Closer and closer, the cassowary stood right there, he stood there.’ | ||||||||

| Em (Bolet 2017a: ln. 42) | ||||||||

| Intermediate demonstratives in Em | ||

| Do | walle | godowallon. |

| do | waɽe | godowaɽon |

| there (int.dem) | water | swim.rem.3sgS |

| ‘It swam to the other side.’ | ||

| Em (Bolet 2017a: ln. 29) | ||

A distal demonstrative form is much rarer, but is observed in Idi (15) and Ende (16). They appear to be based on different formatives in both languages: namely, ḡ (/ɡ͡b/) in Idi and dem in Ende.

| Distal and proximal demonstratives in Idi | |||||

| Mk | plena | da | ḡaleḡale | gwlble, | giligili |

| mək | plen=a | da | ɡ͡baleɡ͡bale | ɡwələble | ɡiliɡili |

| battle | plane=core | foc | that_way | move.hab.3sgS | this_way |

| gwlbli. | |||||

| ɡwələbli | |||||

| move.ven.hab.3sgS | |||||

| ‘War planes used to be flying back and forth.’ | |||||

| Idi (Pid 2017: ln. 130) | |||||

| Proximal, intermediate, and distal demonstratives in Ende | ||||

| Ge | kaptte da | bɨtbɨt | dan , | |

| ɡe | kapʈ͡ʂe=da | bɪtbɪt | da=n | |

| prox.dem | cloth=nom | black | int.dem=cop.prs.sgS | |

| be de | mamam | dan. | ||

| be de | mamam | da=n | ||

| but int.dem | red | int.dem=cop.prs.sgS | ||

| Be dem | de | pällämpälläm a | eran. | |

| be dem | de | pəɽəmpəɽəm=a | era=n | |

| but dist.dem | foc | white=nom | where=cop.prs.sgS | |

| ‘This cloth is black, and that one is red, and that one way over there is white.’ | ||||

| Ende (Baewa 2018: ln. 120) | ||||

Many demonstrative forms, including those used for discourse deixis, can bear nominal morphology such as the ablative, allative, and locative case clitics, and exhibit vowel harmony for deictic directionality as do verbs (see 15).

4 The verbal complex

Verbs can be said to be the center stone of the crown that is the PR language family, as they exhibit complex patterns at multiple structural levels. The most typical verbs can be roughly divided into three categories: synthetic verbs that host their own inflection, analytic constructions that contain an uninflected analytic stem followed by an inflected auxiliary, and copulas containing a grammatical element and a copular clitic.

The three types are showcased in examples (17) and (18). (17) contains an analytic construction (one uninflecting lexical verb ① combined with one inflected auxiliary verb ②) and one synthetic verb ③ which hosts its own inflectional affixes, indicating tense, aspect, mood, argument person and number, verbal number, and directionality.

| Sana | yu ① | dägagän ② | a | nge | ine da | däbem |

| sana | ju | d-ə-ɡaɡ-ən | a | ŋe | ine=da | dəbe=m |

| sago | fire_cook | rem-3nduO-aux-3sgA | and | coconut | water=nom | that=acc |

| dikomän ③ | ||||||

| d-i-kom-ən | ||||||

| rem-ven.3nduO-bring.pl-3sgA | ||||||

| ‘He cooked the sago on the fire and brought coconut water.’ | ||||||

| Ende (Sowati (Kurupel) 2016: ln. 28) | ||||||

Copula predicates function slightly differently: they consist of a copular clitic that fuses argument number and tense and attaches to a grammatical word, such as da ‘that’ in Ende, see ④ in (18).

| Nge | däm a | obene | daeya ④ | ngämo |

| ŋe | dəm=a | obene | da=eja | ŋəmo |

| coconut | sucker=nom | his (3sg.pst.poss) | int.dem=cop.pst.sgS | my (1sg.poss) |

| kobeyam | Barekam. | |||

| kobejam | barekam | |||

| brother_in_law | personal_name | |||

| ‘This coconut sucker was from my brother-in-law Barekam.’ | ||||

| Ende (Jerry and Kaoga (Dobola) 2017: ln. 80) | ||||

In this section, we will organize information about the verbal complex as concisely as possible, starting with a description of the verbal stem, then an explanation of the form and function of the inflectional material, followed by a discussion on copula predicates. We conclude with a summary and an overview of the types of verbal constructions one might encounter in PR languages. Section 6.1 contains a more detailed discussion on analytic verbal constructions in Idi, while Section 6.2 provides more details on object-oriented inflection in Ende ditransitives.

4.1 Verbal stems

4.1.1 Analytic stem and synthetic stems

To discuss the topic of verbal stems, we use the superordinate term lemma to refer to the lexicon entry of a single verb, or a set of related verb stems. For instance, the Kawam lemma ‘to baptize’ consists of the analytic stems kumbog (npl) and kumbumeny (pl) and the synthetic stems ngkubog (npl) and ngkubumeny (pl). In contrast, the Kawam lemma ‘to see’ only contains the analytic stem ikop. Analytic stems differ from synthetic stems in that no inflectional material attaches to them directly, but must occur instead on a following auxiliary element.[7] Consider the contrast between the realization of the lemma ‘to baptize’ with a plural analytic stem kumbumeny preceding an inflected auxiliary verb (19) and with a directly inflected singular synthetic stem ngkubog (20).

| Plural analytic stem of lemma kumbog ‘to baptize’: kumbumeny | ||||

| Ngɨna | bibim | gɨnya | inä me | kumbumeny |

| ŋəna | bibim | ɡəɲa | inæ=me | kumbumeɲ |

| I (1sg.nom) | you (2nsg.acc) | here | water=loc | baptize.pl |

| anggare. | ||||

| aŋɡare | ||||

| aux.prs.1sg>2nsg | ||||

| ‘I will baptize you in this water.’ | ||||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 1:8) | ||||

| Singular synthetic stem of lemma kumbog ‘to baptize’: ngkubog | |||||

| Zon | Yesu bɨm | dɨdɨme | inä | dungkubog ɨ n | Zodɨn |

| zon | jesu=bəm | dədəme | inæ | du-ŋkuboɡ-ən | zodən |

| John | Jesus=3sg.acc | there | water | rem.3sgO-baptize.npl-3sgA | Jordan |

| wäre | poch me. | ||||

| wære | pot͡ʃ=me | ||||

| water | body=loc | ||||

| ‘John baptized Jesus in the Jordan.’ | |||||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 1:9) | |||||

4.1.2 Restricted and extended stems

In both Idi and Ende, verb stems can be divided into two main subclasses: restricted and extended. They correspond to a difference in lexical aspect: punctual/telic versus durative/atelic. In Idi, restricted and extended stems form different conjugation classes. Restricted stems do not take a past tense prefix, and they take a different set of agreement suffixes. There is often a formal similarity between restricted and extended stems from the same lemma, but derivational processes are often opaque and no longer productive. Below, the difference between inflected forms for the remote past is shown by restricted -gädzn- (21) and extended -gädz- (22), both meaning ‘take out’. The different forms reflect different event structures: a python can be removed from a hole all at once (punctual), while honeycomb is removed bit-by-bit (durative).

| Restricted form of Idi gädzn ‘take out’: -gädzn- | ||||

| Ländä | ygädznea | gp-atha. | ||

| lændæ | jə-ɡædʒn-ea | ɡəp-aʈa | ||

| together | 3sgO-take_out-1nsgA | hole-abl | ||

| ‘Together we took it (the python) out from the hole.’ | ||||

| Idi (James 2014: ln. 34) | ||||

| Extended form of Idi gädzn ‘take out’: -gädz- | |

| Kpa | begädza. |

| kəp=a | b-e-ɡædʒ-a |

| fruit=core | rem-3sgO-take_out-1nsgA |

| ‘We removed the honeycomb (from the tree).’ | |

| Idi (Ämädu 2015: ln. 171) | |

This differential inflection marking for restricted and extended stems is not observed in Ende.

4.1.3 Valency of stems

The majority of PR verb stems are either intransitive (subcategorized for a single S[8] argument) or transitive (subcategorized for an A and O argument). There are also many ambitransitive stems that can be intransitive or transitive without any overt derivational process. These are mostly patientive, where the S in the intransitive use corresponds with the O in the transitive use: examples include Kawam zän ‘enter (intransitive; 4.1.3); put into (transitive; 4.1.3)’ or Idi nglbn ‘stand up, grow up (intransitive); lift up (transitive)’. Valency cross-cuts the lexical aspectual distinction; thus, both transitive and intransitive verbs are found in restricted and extended classes.

| Intransitive use of Kawam zän: ‘to enter’ | ||||

| Ge | jhobae | rikochang | dan | Adibo aba |

| ɡe | d͡ʒobaj | rikot͡ʃ=aŋ | da=n | adibo=aba |

| prox.dem | very | difficult=att | int.dem=cop.prs.sgS | God=3sg.poss |

| chongom e | zän e. | |||

| t͡ʃoŋom=e | zæn=e | |||

| kingdom=all | enter=all | |||

| ‘It is very difficult [for rich people] to enter the kingdom of God.’ | ||||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 10:25b) | ||||

| Transitive use of Kawam zän: ‘to put in’ | ||||||

| Ärod Äntipos | […] | dandɨmoenegɨn | Zon bɨre | […] | sɨrämang | makɨp |

| ærod_æntipos | dandəmojneɡən | zon=bəre | səræmaŋ | makəp | ||

| Herod | order.rem.3sg>3pl | John=3sg.dat | dark | place | ||

| zän e. | ||||||

| zæn=e | ||||||

| put_in=all | ||||||

| ‘Herod ordered for John to be put into prison.’ | ||||||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 6:17–18) | ||||||

The intransitive template is also used in passive and anti-passive constructions with verb roots that typically take the transitive template.

4.2 Verbal inflection

Verbal morphology templates are complex and exhibit many types of multiple and distributed exponence. Verbal inflectional categories include tense, aspect, mood, directionality, and verbal number. Inflected verbs consist of a stem and up to four affix slots on either side; exponents of all categories may be found in any of these slots. Moreover, affixes do not correspond to single values and can only be disambiguated by affixes in other slots. This is typical of languages in the area, see for example, the grammars of Yam languages Ngkolmpu (Carroll 2016) and Komnzo (Döhler 2018). Typically in PR, S and A arguments are indexed by a suffix, while O arguments are indexed by a prefix. Some ditransitive verbs, for example Ende ttongg ‘to give’, show agreement with dative-marked recipients (see Section 6.2). Table 5 illustrates the typical structure of an Ende verb, using nälläntmenyaemeyo ‘you (all) will tell them’ as an example:

Inflectional slots in Ende: nälläntmenyaemeyo.

| Tense, subject, object | Object | Verb stem | Pluractional | Tense, subject |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | ä | lläntmeny | aem | eyo |

| fut.2>3 | 3nduO | tell.plO | nsg>pl | fut.2nsgA |

Below, we will briefly discuss multiple and distributed exponence, tense-aspect-mood marking, and participant and event number. For detailed discussion of Ende argument indexing see Section 6.2, for Idi verbal number see Schokkin (2022b), for syncretism, see Appendix D, and for directionality, see Reed and Lindsey (2021).

4.2.1 Multiple and distributed exponence

As in other languages in the area (see for example, Carroll et al. 2016; Döhler 2018), PR languages exhibit distributed exponence in their verbs, meaning morphemes are specified for multiple grammatical categories and those categories are distributed across morphemes (Carroll 2022; Carroll et al. 2016; Caballero and Harris 2012; Harris 2017). Under Caballero and Harris’ (2012) typology, multiple exponence in PR is affixal and formally distinct, with no licensing dependency on each other. In other words, to determine the values for verbal categories, the entire verb must be considered.

The Ende form in (25) illustrates this complexity. Each morpheme in (25) has as many as five potential interpretations across tense (remote past, recent past, future/irrealis), arguments (A, O), person (1, 2, 3), and number (singular, dual, plural). For example, the first morpheme in (25), n-, provides five possible interpretations (rec.tr.sgO; rec.tr.plO; fut.3>2sg; fut.2>3sg; fut .2>3 pl ), while the final morpheme -eyo has three possible interpretations (rem.3nsgA; fut.3nsgA; fut .2 nsg A).[9] The co-occurrence of these two morphemes disambiguates the verb as being future tensed since that is the only interpretation compatible with both morphemes. Accordingly, the verb in (25) has an unambiguous tense, despite the ambiguity at the morpheme level.

| nälläntmenyaemeyo |

| n-ə-ɽəntmeɲ-ajm-ejo |

| fut.2>3pl-3plO-tell.plO-nsg>pl-fut.2nsgA |

| ‘You all will tell them/those stories.’ |

| Ende (Kurupel (Suwede) and Warama 2009: ln. 855) |

The glossing line in (25) illustrates how indexing of the O argument is manifest across four morphemes: the tense prefix (n-), the O-prefix (ə-), the stem (ɽəntmeɲ), and the pluractional suffix (-ajm). In transitive verbs with a single O argument, these morphemes all agree with the person and number features of that O argument and by association also accord with one another.

4.2.2 Tense-Aspect-Mood marking

All varieties have three morphological perfective tenses: remote past, typically used for events that happened before sunset yesterday, recent past for events earlier today and last night, and future for upcoming events, imperatives, and other modal extensions. A fourth inflectional paradigm, called imperfective, primarily has past habitual and irrealis uses. Examples (26) and (27) show the two past tenses in Agob, distinguished by differing tense prefixes for the verb oter ‘to sleep’.

| Remote past form of Agob oter ‘to sleep’: gwoternen | |

| Déréng de | gwoternen . |

| dərəŋ=de | ɡw-oternen |

| dog=nom | rem-sleep.3sgS |

| ‘The dog was sleeping.’ (lit. ‘The dog fell asleep a while ago.’) | |

| Agob (Billy 2015: ln. 21) | |

| Recent past form of Agob oter ‘to sleep’: noternen | |

| Déréng de | noternen . |

| dərəŋ=de | n-oternen |

| dog=nom | rec-sleep.3sgS |

| ‘The dog is sleeping.’ (lit. ‘The dog fell asleep recently.’) | |

| Agob (Billy 2015: ln. 20) | |

Formal marking of tense-aspect-mood (TAM) is distributed across the verb, appearing primarily in the first prefix slot (which also marks valency), the first suffix slot (which also marks verbal number), and the final suffix slot (which also indexes S and A arguments).

Several verbal particles are identified which add further modal meanings to a clause, like the future particle ményi in Agob (28).

| Agob future verbal particle: ményi | |||||

| Kénazbag | ngéna | ményi | obom | ikop | bege. |

| kənazbaɡ | ŋəna | məɲi | obom | ikop | b-eɡe |

| tomorrow | I (1sg.nom) | fut | him (3sg.acc) | see | fut-aux.1sg>3sg |

| ‘Tomorrow, I will see him.’ | |||||

| Agob (Billy 2015: ln. 138) | |||||

The present progressive can only be expressed in an analytic construction, see (29). This type of periphrastic construction is also used for the other TAM values for non-inflecting verbs and is discussed in Sections 4.1 and 6.1.

| The present progressive requires an analytic construction[10] | |||

| Déréng da | mon | iko | igan . |

| dərəŋ=da | mon | iko | iɡan |

| dog=nom | girl | see | aux.prs.3sg>3sg |

| ‘The dog sees the girl.’ | |||

| Agob (Billy 2015: ln. 23) | |||

4.2.3 Participant number

Participant number marking (Corbett 2000) is particularly interesting in PR, as verbs exhibit different types of number marking in multiple locations. Suffixes typically agree in number with S and A arguments, while prefixes agree with O arguments. Many verb stems also alternate according to the plurality of the absolutive participant: if the S or O argument has a plural referent (greater than two), the use of a plural stem is obligatory: compare for instance Idi wadzan ‘enter, put into (nonplural S/O)’ and dzardzar ‘enter, put into (plural S/O)’. Plural stems can also be used to mark event number, for example, with actions that are performed several times or at several places.

Interestingly, affixes and stems do not distinguish the same number categories. In Idi, the O-prefix distinguishes singular and non-singular (2+) objects, while the stem distinguishes non-plural (1–2) and plural (3+) participants. Thus, a dual object is indexed with a nonsingular prefix and a nonplural stem, see (30). In this example, paucal number (a small number greater than 2) for the A can only be deduced from the use of the suffix -m, referring to plurality of an S or A, on the second verb. See Schokkin (2022b) for an in-depth discussion of verbal number in Idi.

| Combination of nsg and npl gives dual or paucal reading, while combination of nsg and pl gives plural or paucal reading | ||

| Kublä | yabdhea , | |

| kubɪl=æ | ja-bəɖ-ea | |

| bush.wallaby=core | nsgO-kill.npl-nsgA | |

| daytha | ako | wapthnmea |

| daj=ʈa | ako | w-a-pthən-m-ea |

| int.dem=abl | again | intr-tv-depart-plS-nsgS |

| ‘We (du|pc) killed two bush wallabies, and we (pc|pl) took off again from there.’ | ||

| Idi (Yamta 2016: ln. 15) | ||

Both Idi and Ende have a dedicated slot between the stem and the S/A suffix slot, which takes a form marking the (non-)plurality of both A and O in transitive verbs. In Ende, if the A is singular and the O is plural (3+), the -neg suffix is used, see (31). If the A is nonsingular (2+) and the O is plural (3+), -aeb is used, see (32).

| Ende plural suffix -neg indexes a singular subject and a plural object | ||

| Bogo | mɨnyi | bibim |

| boɡo | mɪɲi | bibim |

| he (3sg.nom) | fut | you all (2nsg.acc) |

| yawengaemnegän. | ||

| ja-weŋajm-neɡ-ən | ||

| fut.2nsgO-forget.plO-sg>pl-3sgA.fut | ||

| ‘He will forget you (3+).’ | ||

| Ende [elicited] | ||

| Ende plural suffix -aeb/-aem indexes a nonsingular subject and a plural object | ||||

| Llɨg a | oba | bägäl a | wa | täbäll a |

| ɽɪɡ=a | oba | bəɡəl=a | wa | təbəɽ=a |

| child=nom | their (3nsg.poss) | bow=nom | and | spear=nom |

| dänglläbaebeyo. | ||||

| d-ə-ŋəɽəb-ajb-ejo | ||||

| rem-3nduO-get.plO-nsg>pl-3nsgA.rem | ||||

| ‘The children got their bows and spears.’ | ||||

| Ende (Dareda 2016: ln. 7.1) | ||||

Thus, we see multiple ways in which number marking is distributed across verbs. Sometimes, a number value does not have a dedicated form, but is constructed by combining different elements with other values, see (30). Elsewhere, number is marked simultaneously in several places on the verb without serving a disambiguation function, as in (31) where the plural (3+) quantity of the O is indexed in the prefix, the stem, and the suffix immediately following it.

4.3 Copular verbs

Copular verbs function differently from lexical verbs in that they consist of a copular enclitic that fuses number and tense and attaches to a grammatical word. Copular inflection only indicates subject number (singular, dual, or plural) and two tenses (past and present), as shown for Ende and Idi in Tables 15 and 16 in Appendix E.

To form the basic copula, these inflected elements can be attached to the intermediate demonstrative da, as shown for Taeme (33).

| Basic copula in Taeme | ||

| Bo | ngémo | dan . |

| bo | ŋəmo | da=n |

| he (3sg.nom) | my (1sg.poss) | int.dem=cop.prs.sgS |

| ‘He is mine.’ | ||

| Taeme (Tama 2019) | ||

The existential copula is formed by attaching a copular clitic to the reduplicated form of the basic copula dade, as shown for Em (34).

| Existential copula in Em | ||

| Ngémo | mélla | dadeg . |

| ŋəmo | məɽa | da∼de=ɡ |

| my (1sg.poss) | woman | exist∼int.dem=cop.prs.sgS |

| ‘I have a wife.’ (lit. ‘My wife exists.’) | ||

| Em (Bolet 2017a: ln. 8) | ||

Copular clitics can be added to other grammatical words like interrogative forms (what and where), adverbs (here or there), or pronouns (I or you).

Some erstwhile copular forms appear to have been (partly) reanalyzed and function primarily as markers of information structure, a process also attested for various Yam languages (Evans et al. 2018b). Example (15) shows a similar use of da in Idi, where it functions as a focus particle for the phrase mk plena rather than as a spatial demonstrative, as evidenced by the distal demonstrative ḡaleḡale immediately following it. Example (35) shows a copular question with ‘what’, while (36) shows the use of eragaya ‘where was’ as a focus particle after the subject of a copular clause.

| Copular clitic + kada ‘what’ in Kawam | ||||

| Kujhur ach | pɨnongg dabo | mog | kadan | ke? |

| kud͡ʒur=at͡ʃ | pənoŋɡ=da=bo | moɡ | kada=n | ke |

| death=abl | rise=nom=3sg.poss | meaning | what=cop.prs.sgS Q | |

| ‘What is the meaning of rising from the dead?’ | ||||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 9:10) | ||||

| Copular clitic + era ‘where’ in Kawam | ||||

| oba | tikop | eragaya | jhobae | rikochang |

| oba | tikop | era=ɡaja | d͡ʒobaj | rikot͡ʃaŋ |

| their (3nsg.poss) | heart | where=cop.pst.plS | very | hard |

| dagaya | ||||

| da=ɡaja | ||||

| int.dem=cop.pst.plS | ||||

| ‘Their hearts were hardened.’ | ||||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 6:52) | ||||

Copular verbs also support the possessive verbal construction, in which verbs of having, knowledge and desire are paired with the possessive pronouns (ngämo umllang da …dan ‘my knowledge is …’), and the simple past, present, and future tenses, in which the ablative, locative, allative clitics, respectively, pair with an analytic stem (ngäna …=att/me/we dan ‘I am from/in/about to …’).

5 Syntax

Word order in PR varieties is flexible (Brown 2020) but is typically subject-verb (SV) in intransitive clauses (see (39)) and agent-object-verb (AOV) in transitive clauses (see (41)). One notable exception is the experiencer-object construction, ordered OAV (see (37) and Section 6.1.5).

| Experiencer-object constructions have OAV word order. | |||

| Babom | nya | ngémi | dekolnea. |

| [babom] O | ɲa | [ŋəmi] A | d-ə-ekol=neja |

| you (2sg.acc) | mod | we (1nsg.excl.nom) | rem-2O-scratch=1nsgA |

| ‘You were scratched by us.’ (lit. ‘We scratched you.’) | |||

| Taeme (Tama 2019) | |||

Phrasal heads are phrase-final with a few exceptions: many nominal modifiers occur after the noun (e.g., Agob késre ‘small’, see (38)), and one deictic demonstrative acts as a preposition (Ende do ‘there; until’). PR uses a system of non-finite verbs paired with auxiliary and phasal verbs instead of the clause chaining patterns common among Trans-New Guinea languages (Pawley and Hammarström 2018: 98–99).

| Many nominal modifiers, like késre ‘small’, follow nouns. | ||

| Mén | késre de | notarnen. |

| mən | kəsre=de | notarnen |

| girl | small=nom | sleep.rec.3sgS |

| ‘The young girl is sleeping.’ | ||

| Agob (Billy 2015: ln. 19) | ||

5.1 Alignment and marking of core arguments

As detailed in Section 3.1, pronominal systems show nominative-accusative alignment. For example, the first-person nominative and accusative pronouns in Ende are distinguished by a suffixal -m (ngäna 1sg.nom and ngänäm 1sg.acc). In Ende and Idi, these pronouns are only used for humans or anthropomorphic characters in stories, while demonstrative forms refer to non-human referents. In Ende, the suffixal -m also marks the accusative form for demonstratives, but not in Idi. Non-pronominal arguments are indexed with nominative case in typical subject and agent roles and with accusative case in typical patient roles, as shown for Em (39).

| Non-pronominal arguments exhibit nominative-accusative alignment. | |||

| Llabo da | mon de | ikop | négagon. |

| [ɽabo=da] A | [mon=de] O | ikop | nəɡaɡon |

| man=nom | woman=acc | see | aux.rec.3sg>3sg |

| ‘The man saw the woman.’ | |||

| Em (Munu 2018: ln. 89) | |||

Idi stands out within the family because it shows neutral alignment on full NPs when the O argument has a non-human referent.[11] A phrasal clitic =A {=ä; a}, glossed core, flags NPs functioning as S, A and O arguments: see (40) and (41), where all arguments bear the same case marker in a transitive and intransitive clause, respectively. =A is not attested on nouns that end in the vowel /a/ or on proper names.

| In Idi transitive clauses, both A and O are marked with core clitic =A. | ||

| Bo | manggmangga | sémblä |

| [bo | maŋɡ∼maŋɡ=a] A | [sɪmbl=æ] O |

| my (1sg.poss) | pl∼brother=core | pig=core |

| ybdheo. | ||

| jəbəɖeo | ||

| kill.rem.3nsg>3sg | ||

| ‘My brothers killed the pig.’ | ||

| Idi (Ado 2014: ln. 32) | ||

| In Idi intransitive clauses, S is marked with core clitic =A. | ||

| Qändä | kpa | wäsplin. |

| [k͡pændæ | kəp=a] S | w-æ-spl-in |

| tree_species | fruit=core | intr-tv-fall-3sgS.rem |

| ‘A qändä nut fell.’ | ||

| Idi (Purgä 2014: ln. 3) | ||

O arguments with human or anthropomorphic reference may be marked by suffixal -m, see (42). This is also observed in Taeme.

| Idi and Taeme exhibit differential object marking; human and anthropomorphic objects are marked with suffixal -m. | |||||

| Obo | mélbä | gta | yépi | lam | yéndhpä |

| [obo | mɪlbæ] A | [ɡəta | jɪpi | la-m] O | jɪnɖpæ |

| his (3sg.poss) | sister | this | supernatural_being | man-acc | see |

| begän. | |||||

| beɡæn | |||||

| aux.pfv.npl.rem.3sg>3sg | |||||

| ‘His sister saw the yépi man.’ | |||||

| Idi (Ämädu 2014: ln. 18–19) | |||||

The syntactic role of arguments in cases like (40) is disambiguated through a range of factors including discourse pragmatics, constituent order (with AOV more common than OAV in clauses with activity verbs), and animacy.

Idi’s neutral alignment is probably a result of historical vowel changes and consonant loss, leading to a merger of proto-PR *=(d)a ‘subject/agent marker’ and *=de ‘object marker’. This neutralizing process may have been reinforced by nearby Nen’s ergative-absolutive alignment in pronominal and noun marking systems. As there are many bilingual speakers, some convergence may have occurred. Detailed research modeling language change in Nen and Idi is needed to infer how the two grammars have been affected by contact.

Other PR languages, like Taeme, distinguish nominative and accusative clitics for all referents, but animacy still affects case marker selection. NPs with non-human referents take case clitics =(d)a and =de to mark nominative and accusative cases, respectively. For the nominative, =da occurs after vowel-final words, while =a follows consonant-final words.

| Intransitive subjects are marked with nominative: =da | ||

| La da | gaben | alan. |

| [la=da] S | ɡaben | alan |

| man=nom | stand | aux.prs.3sgS |

| ‘The man is standing.’ | ||

| Taeme (Geser 2018a: ln.41) | ||

| Transitive subjects are marked with nominative: =da; transitive objects are marked with accusative: =de | |||

| La da | mla de | yékép a | nagan. |

| [la=da] A | [mla=de] O | jəkəp=a | naɡan |

| man=nom | woman=acc | eye=vb | aux.rec.3sg>3sg |

| ‘The man saw the woman.’ | |||

| Taeme (Geser 2018a: ln.43) | |||

For full NPs with human referents, =(d)a is used for nominative but the pronominal accusative clitic, e.g., Kawam =bɨm marks accusative case (45).

| Animate accusative objects are marked with a pronominal accusative case clitic | ||||

| ubi | tɨmamae | Yesu b ɨ m | ikop | dɨgag yɨng |

| [ubi | təmamaj] A | [jesu=bəm] O | ikop | dəɡaɡjəŋ |

| they (3sg.nom) | all | Jesus=3sg.acc | see | aux.rem.3nsg>3sg |

| ‘They all saw Jesus.’ | ||||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 6:50) | ||||

Finally, conjoined objects are marked with the nominative case clitic =(d)a as opposed to the accusative case clitic =de (46). This pattern, in which A and O are both marked nominative, is curiously similar to the core case marking in Idi described above.

| Conjoined objects are marked with nominative case: =da | |||||||

| Ede | adibach | deda | mit ach | ra da | medi da | wa | mɨg da |

| ede | adibat͡ʃ | deda | mit=at͡ʃ | [ra=da] A | [medi=da] O | wa | [məɡ=da] O |

| so | because | this | reason=abl | man=nom | father=nom | and | mother=nom |

| wanysɨgeny | yaran. | ||||||

| waɲsəɡeɲ | jaran | ||||||

| leave | aux.prs.3sg>3du | ||||||

| ‘This is why a man will leave his father and mother.’ | |||||||

| Kawam (The Kawam Language Committee and The Lewada Bible Translation Centre 2010: Mark 10:7) | |||||||

Transitive clauses with two overt core arguments (as pronouns or NPs) are rare because core arguments are not usually expressed when retrievable from the discourse context. Person/number values of core arguments can additionally be indexed by verbal agreement affixes. However, due to many syncretisms, referents are often not fully recoverable based on just the verb, and a form like Idi nabdhan could either mean ‘I hit you’ or ‘he hit me’, depending on the context. This kind of under-specification is an areal feature of southern New Guinea (see Evans et al. 2018a).

6 An in-depth look at the PR verbal complex

We will now discuss two topics related to PR verbs in more detail: analytic constructions, illustrated by Idi, and indexing on ditransitive verbs, illustrated by Ende. These topics were chosen both for their interest to typologists, as they illustrate features that may be rare cross-linguistically, and for their apparent centrality to how PR grammars are organized with respect to verbs. Although this discussion is based on analyses of Idi and Ende, we consider them to be pivotal elements determining the “genius” (Sapir 1921) of the family.

6.1 Analytic constructions in Idi

The distinction between constructions with an inflected verb stem (synthetic constructions) and those in which an auxiliary element is inflected (analytic constructions) is discussed in Section 4.1. Here we focus on analytic constructions, illustrated with examples from Idi. We consider these to be a type of complex predicate, and question whether they should be treated as light verb or auxiliary verb constructions. To this end, we include a detailed discussion of the uninflecting elements in Section 6.1.1 and of the inflecting elements in Section 6.1.2. Next, the discussion will turn to other constructions that show similarities to analytic constructions, but are not considered complex predicates. The overview will finish with a hypothetical grammaticalization path along which analytic constructions could have developed. Ende shows clear parallels with Idi in this respect, and the data we have on the other PR languages suggest that they operate comparably.

6.1.1 The uninflecting element: analytic stems

As mentioned, most lexical verbs have two stems: an analytic form used in a periphrastic construction for the present tense, and a synthetic form used for the other tenses. For example, the verb ‘to bite, eat (meat)’ has the analytic stem dhndhg (47), and the synthetic stem -ndhg- (48).[12]

| ngn | dhndhga | dhndhg | yran. |

| ŋən | ɖənɖəɡ=a | ɖənɖəɡ | jəran |

| I (1sg.nom) | meat=core | eat | aux.prs.3sg>3sg |

| ‘I am eating meat.’ | |||

| Idi (Elicited) | |||

| Gta | päklä | bi | thayabe | bendhga. |

| ɡəta | pæklæ | bi | ʈajabe | b-e-nɖəɡ-a |

| this | python | us (1nsg.excl.nom) | every | rem-3sgO-eat.meat-1nsgA |

| ‘All of us ate the python.’ | ||||

| Idi (Ämädu 2017: ln. 98) | ||||

In addition to the verb lemmas with both types of stem, we also find many lemmas containing only analytic stems. These are never inflected directly but always followed by a separate form, not only in the present, but also the other TAM categories. Frequently occurring examples are yeka ‘to tell, speak’ (also a noun meaning ‘language’) and yéndhpä ‘to see’ (related to yéndhép ‘eye’). Below, the use of yéndhpä is illustrated for the present, remote past, and recent past tenses, respectively.

| Yéndhpä | yrälä | bä | gta | tmea? |

| jɪnɖpæ | jərælæ | bæ | ɡəta | təme=a |

| see | aux.prs.npl.2sg>3sg | you (2.nom) | this | crocodile=core |

| ‘Do you (still) see this crocodile?’ | ||||

| Idi (Eka 2015: ln. 326) | ||||

| Dia | bom | yéndhpä | gagn. |

| dia | bom | jɪnɖpæ | ɡaɡən |

| deer | me (1sg.acc) | see | aux.pfv.npl.rem.3sg>1sg |

| ‘The deer saw me.’ | |||

| Idi (Qbr 2015: ln. 64) | |||

| Yau | ngay | yéndhpä | nagn. |

| jau | ŋai | jɪnɖpæ | naɡən |

| neg | just | see | aux.pfv.npl.rec.1sg>3sg |

| ‘I didn’t really see it.’ | |||

| Idi (Ämädu 2015: ln. 184) | |||

Analytic stems subcategorize for transitivity of the accompanying form. Yeka, for instance, combines with either transitive or intransitive inflected forms, whereas yéndhpä occurs exclusively with a transitive inflected form. Many analytic stems refer to bodily processes, emotions and physical sensations, or to states, such as si ‘to urinate’, ngndä ‘to cry’, or yéndu ‘to sleep’.

Borrowed verb forms only occur in analytic constructions and are never inflected directly. Obvious loans are, for instance, the English verbs miks ‘to mix’ and lus ‘to lose’. Also English nouns, such as sespin (‘to boil in water’, lit. ‘saucepan’) or paia (‘to shoot with a gun’, lit. ‘fire’) are encountered in this construction. Facilitating the use of loanwords as verbs is a function of complex predicates observed across the Southern New Guinea region and elsewhere. For example, in Lavukaleve, a Papuan language of the Solomon Islands, there is a special verb-adjunct construction used just for loanwords (Terrill 2003: 399–400). For discussion of Komnzo (Yam), see Döhler (2018: 115), for Urdu, see Butt (2010), and for Bardi, see Bowern (2010).

Within the category of analytic stems, it is difficult to make a principled distinction between primarily verbal and primarily nominal stems. As mentioned in Section 3.2, analytic stems can function in non-finite subordinate clauses, taking nominal case marking. They can also function as core arguments to verbs (bearing a core case clitic, see Section 3.2), and be possessed. Below, (52) shows allative case on käkäly ‘to load’ (synthetic stem -käly-) to express purposive meaning, and (53) shows locative case on wélwél ‘to wait’ (synthetic stem -wl-) to express simultaneity of events. These suffixes are also found on nouns (see (54) and (55)) with the same semantics, as well as in their original spatial sense. Crucially, there is no formal difference in flagging case on a stem with uncontroversial verbal origins like ‘to load’, (52), and an uncontroversial nominal stem like ‘basket’, (54).

| Doatha | ält | dinggiä | dzirun, | oblä |

| do=aʈa | ælt | dɪŋɡi=æ | djirun | oblæ |

| given_location=abl | health | dinghy=core | go.rem.ven.3sgS | her (3sg.dat) |

| käkälyäwä. | ||||

| kækæʎ=æwæ | ||||

| load=purp | ||||

| ‘From there, an emergency dinghy came to pick her up.’ | ||||

| Idi (Purgä 2016: ln. 37–38) | ||||

| Wélwélmä | sémblä | mk | begän. |

| wɪlwɪl=mæ | sɪmbl=æ | mək | beɡæn |

| wait=sim | pig=core | shoot | aux.pfv.npl.rem.3sg>3sg |

| ‘While waiting, he shot a pig.’ | |||

| Idi (Ḡambia 2014: ln. 29) | |||

| Gl | thämä | gaytha | btrpnmndeo | spelénggäwä. |

| ɡəl | ʈæm=æ | ɡaj=ʈa | bətrəpənməndeo | spelɪŋɡ=æwæ |

| fut | leaf=core | prox.dem=abl | cut.fut.ext.3nsg>3nsg | basket=purp |

| ‘They will be cutting the leaves from it [the coconut] for baskets.’ | ||||

| Idi (Gegera 2015: ln. 24) | ||||

| Ngiä | gta | plomä | ybänyin. |

| ŋi=æ | ɡəta | plo=mæ | jəbæɲin |

| coconut=core | this | single_man=sim | plant.rem.1sg>3sg |

| ‘I planted this coconut while I was single.’ | |||

| Idi (Kbd 2015: ln. 31) | |||

When a verbal lemma has both an analytic and a synthetic form, the analytic stem always contains either the same amount of or more morphological material than the synthetic stem. Thus, the former are analyzed as derived from the latter.

6.1.2 The inflecting element: auxiliary verbs

We will now turn our discussion to the elements bearing inflection in analytic constructions, and show that they are best analyzed as auxiliaries. We consider Idi analytic constructions a type of complex predicate: they involve two predicational elements that predicate as a single unit, and whose core arguments map onto a mono-clausal syntactic structure (Butt 2010: 2). Mono-clausal structure follows from the fact that the analytic stem always appears unmarked in the construction under discussion here. By contrast, when an analytic stem is used in a subordinate clause, and thus the construction as a whole is multi-clausal, the analytic stem is marked by a nominal case suffix, see (52–53). Neither is there any indication that the analytic stem functions as a core argument to the inflected element, as it is never marked with a core case clitic.[13]

Although the issue has received much attention in the typological and theoretical linguistic literature (both formalist and functionalist), it has proven difficult to establish good cross-linguistic criteria to distinguish between the various types of complex predicates. One such attempt puts forward the following criteria to tell apart light verb constructions from other complex predicates, most notably auxiliary verb constructions (Seiss 2009: 509; also cf. Butt 2010; Butt and Lahiri 2002):[14]

Light verbs are always identical in form to the corresponding main verb, whereas auxiliaries are usually form identical only at the initial stage of reanalysis from verb to auxiliary.

Light verbs always span the entire verbal paradigm, and are not restricted to appear with just one tense or aspect form.

Light verbs do not display defective paradigms.

Light verbs exhibit subtle lexical semantic differences in terms of combinatorial possibilities with main verbs, and are thus restricted in their combinations. Auxiliaries, on the other hand, are not restricted in their combinatorial possibilities (although they do not have to combine with every main verb).

The first criterion implies that in languages exhibiting light verbs, there will be a fully productive lexical counterpart to each of these elements. What is more, in order for the elements to count as light verbs “proper,” they have to be identical in form to these lexical counterparts. It is here that Idi analytic constructions depart most radically from more prototypical light verb constructions as found in many languages of Australia and the Indian subcontinent. Only a very limited number of Idi stems are encountered fulfilling the function of an inflecting element in a complex predicate, and moreover, these stems are encountered in only two additional functions: in copula and experiencer-object constructions, discussed below in Section 6.1.4–6.1.5. Also in these latter functions, they can be considered semantically empty forms.

Present tense is only expressed with an analytic construction, with a dedicated auxiliary -r- ∼ -l- (plural stem -nga-); see Appendix E, and, for example, (49). Other TAM values exhibit both analytic and synthetic constructions, and here we find perfective -g- (suppletive 3sgO -gä-, plural -gädzi-), and imperfective -nd- (plural -ndr-). None of these are found outside the three construction types under discussion in this paper, which indicates that they cannot serve the same function as lexical verbs. Instead, they are highly grammaticalized items serving as a vehicle for verbal inflectional categories like TAM, directionality, and person/number of core arguments, when combining with forms that are not allowed to bear verbal inflection themselves.

A brief contemplation of potential lexical sources points to the same conclusion. The present progressive stem is homophonous with the basic motion verb ‘to go ∼ come’,[15] whereas the perfective and imperfective stems are formally similar to the lexical verb ḡg ‘to make’ and the 1|3sg present copula =nd, respectively. However, their inflectional paradigms do not show much similarity (but note that both the present progressive stem and the motion verb show the same type of person suppletion, a rare feature cross-linguistically). The inflecting forms in analytic constructions may have grammaticalized from lexical verbs at some point, but this historical relationship is now shrouded in obscurity due to the complexity of Idi inflectional patterns.

Thus, it is clear that the inflecting forms in the Idi analytic construction do not meet the first criterion as stated above, to be considered light verbs. Additionally, as the present tense has a separate form, they do not adhere to criterion (2) very well either. The forms do not show defective paradigms compared to lexical verbs, as, for instance, the copulas do, and so they do meet criterion (3). As for criterion (4), there appear to be few to no combinatorial restrictions on non-inflecting and inflecting forms, which indicates that Idi also does not meet this criterion.

Based on this, it appears that the inflected forms in Idi analytic constructions would be better analyzed as auxiliary verbs, as opposed to light verbs. This raises issues because the term auxiliary verb is reserved for elements that consitute a complex predicate exclusively with unambiguously verbal forms. Anderson (2006, 2011 provides a thorough cross-linguistic study of auxiliary verb constructions and other complex predicate types, taking a functional-constructional approach, and includes discussion of cases which may not be considered auxiliary verb constructions under stricter approaches. Nevertheless, Anderson (2011: 796) defines auxiliary verb constructions as “mono-clausal verb phrases that minimally consist of an auxiliary verb component that contributes some grammatical content to the expression and a lexical verb component that contributes lexical content to the expression” [emphasis ours]. When discussing light verb constructions, the author is more agnostic as to what the non-inflecting element can pertain to (2011: 812): “one element is predicative and lexically rich, but the other element is lexically empty and merely instantiates the argument structure of the construction and allows for the predicative element to be expressible morphosyntactically.”

Anderson states in a following footnote that in some languages the boundary between light verbs and auxiliaries may be near impossible to draw, citing data from the Papuan language Mek, and it is likely not the author’s intention to propose a principled distinction, per se, between auxiliary verb and light verb constructions. The above examples have shown that Idi too poses difficulties for classifying uninflected elements in analytic constructions as either primarily verbal or non-verbal. This is problematic for analyzing these constructions as auxiliary verb constructions under a strict definition. Moreover, in the other construction types to be discussed (in Section 6.1.3), they do combine with forms that are unambiguously nominal, although they do not form a complex (verbal) predicate with these forms. In terms of its function, the Idi analytic construction fits Anderson’s definition of light verb construction well.

Another recurring issue in the analysis of complex predicates is which of the participating forms, if any, can be considered the head of the construction. From the literature, it appears that certain characteristics associated with the predicate head can be shared by two or more forms in both light verb and auxiliary verb constructions. Thus, this criterion appears not to be a good diagnostic in distinguishing between the two types of constructions. Both the Idi non-inflecting form and inflecting form in the analytic construction can be said to have characteristics of (verbal) predicate heads. The non-inflecting form determines the valency of the construction as a whole, since it subcategorizes for arguments, and can be marked for verbal number, whereas the inflecting form (in addition to bearing all TAM, directional, and agreement marking) is needed to form a grammatical sentence and can be considered the syntactic head of the construction.

The above discussion has shown that Idi (and by extension, the PR family) poses a challenge to the current typology of complex predicates. It appears that the definition of either the light verb construction or the auxiliary verb construction has to be broadened to accommodate the Idi phenomena. Either a definition of light verb constructions has to allow for the fact that the light verbs in question could entail highly grammaticalized elements not occurring also as lexical verbs, or a definition of auxiliary verb constructions has to allow for a non-inflecting element with a structurally ambivalent status in terms of its part-of-speech.

Despite the difficulties presented in analyzing the construction as a whole, the inflecting stems that can occur in Idi analytic constructions clearly form a separate verbal category based on language-specific criteria, and henceforth will be referred to by the term auxiliaries.

6.1.3 Other constructions that show similarities to analytic constructions

Two further construction types in Idi resemble the analytic construction, but do not form a complex predicate: constructions in which the auxiliaries function as copulas (Section 6.1.4), and experiencer-object constructions (Section 6.1.5). Due to their similarities, these construction types may be connected to the analytic construction, and could explain its origin. The sections below discuss the constructions in turn, followed by a discussion of a possible historical relationship with the analytic construction.

6.1.4 Copula constructions with auxiliaries

In addition to the copular enclitics, which show a reduced inflectional paradigm and can attach to different parts-of-speech (see Section 4.3), Idi also exhibits copular use of the same auxiliaries encountered in analytic constructions. Each of the three is attested in such constructions. The present progressive auxiliary is encountered both with the sense ‘be’ and ‘become’, while the perfective and imperfective auxiliaries mostly have the sense ‘become’. Because the predicative expression (PE) in a copula construction is not marked by a core case clitic, many of the constructions in which one of the auxiliaries is used as a copula are formally identical to analytic constructions. Below, examples are given: (56) and (57) with the present progressive auxiliary, and (58) and (59) with the perfective auxiliary.

| La mg | wlan. |

| la_məɡ | wəlan |

| old_man | aux.prs.npl.1sgS |

| ‘I am an old man.’ | |

| Idi (Gangge 2014: ln. 104) | |

| Miäng | wlan. |

| mi-æŋ | wəlan |

| flower-att | aux.prs.npl.1sgS |

| ‘It [the coconut tree] is flowering.’ | |

| Idi (Daiba 2015: ln. 28) | |

| Ydi | la mg | gwagn? |

| jɪdi | la_məɡ | ɡwaɡən |

| Q | old_man | aux.pfv.npl.rem.3sgS |

| ‘Did he become an old man?’ | ||

| Idi (Kawa 2015: ln. 48) | ||

| Mer | begäyo. |

| mɛr | beɡæjo |

| good | aux.pfv.npl.rem.3nsg>3sg |

| ‘They fixed it up.’ | |

| Idi (Greh 2014: ln. 71) | |

These examples show that the auxiliaries can fulfill both the copular function of expressing a relation of identity or class membership (see (56, 58)), and expressing an attributive relation (57, 59), in addition to other copular functions such as expressing locatives. When it expresses a relation of identity, the PE is a noun such as la mg ‘old man’, and when it expresses an attributive relation, the PE is an attributive adjective such as mer ‘good’ or miäng ‘with flowers’ (derived from a noun with the attributive suffix).[16] We also find auxiliaries with transitive inflection, particularly when the predicative expression refers to a property, as in (59). In essence, this yields a causative of a copula construction: ‘they made it (be) good.’

The copular enclitics are not attested with the ‘become’ sense, and neither do they occur with transitive inflection. But (56–57), for instance, do have counterparts with the 1|3sg present copula =nd, cliticized to a demonstrative form. At present, the exact factors that determine the use of the auxiliary-as-copula construction instead of the use of the enclitic form are not well understood. The permanency of the reference may play a role, in addition to whether the referent is available in the immediate physical or discourse context or not. This remains an area for further research.

6.1.5 Experiencer-object constructions

The construction termed experiencer-object construction is transitive, and contains two argument NPs, one referring to an affected entity and one to an affecting entity, in addition to an inflected auxiliary. The main difference between experiencer-object constructions and analytic constructions is that the former are not complex predicates. For them, the auxiliary is unambiguously the sole predicate head, and the other constituents are unambiguously nominal, serving as core arguments to the verbal predicate head, marked by a core case clitic when expressed as full NPs. The two construction types have in common that in both cases, the inflected verb is semantically empty, and primarily functions to license the morphosyntactic expression of a particular event type, by serving as a vehicle for verbal inflectional categories. The main lexical contribution comes from the NP referring to the affecting entity, and this can be said to be the “semantic head” of the construction.

Experiencer-object constructions typically convey states or changes of states, in which a human or highly animate participant (the experiencer) is affected by an entity over which they have no control. The experiencer is the O argument of the construction, whereas the affecting entity is the A argument. Typically, the O is highly animate but low in volition, whereas the A is inanimate or abstract. Experiencer-object constructions tend to have OAV constituent order, whereas in general, AOV is more standard. This construction type is widely attested in Papuan languages; see for example, Foley (1986: 121–124, 2018: 925–926) and Pawley and Hammarström (2018: 113–115).

Not many lexical verbs refer to bodily sensations and emotions, and experiencer-object constructions often convey these meanings. They employ the same auxiliaries as mentioned above: -r- ∼ -l- for present tense, and -g- or -nd- for the other tenses. Some examples are given below; (60) has the typical OAV order shown by experiencer-object constructions, while (61) shows AOV order.

| Bom | wota | nalan. | |

| [bom] O | [wot=a] A | nalan | |

| me (1sg.acc) | garden_food=core | aux.prs.npl.3sg>1sg | |

| ‘I am hungry.’ (lit. ‘food affects me’) | |||

| Idi | |||

| Dhndhg mga | bim | dzagn | |

| [ɖənɖəɡ məɡ=a] A | [bim] O | djaɡən | |

| meat real=core | us (1nsg.acc) | aux.pfv.npl.rem.3sg>1nsg | |

| Peireälä. | |||

| Peire=ælæ | |||

| personal_name=com | |||

| ‘Peire and I were really hungry for meat.’ (lit. ‘meat affected the two of us’) | |||

| Idi (Baiio 2014: ln. 8) | |||

From the examples, it is clear that the meaning of the construction as a whole is determined by the noun heading the NP referring to the affecting entity. Substituting dhndhg ‘meat’ for wot ‘garden food’ has the effect that now the construction specifies that the affected human participants are hungry for meat specifically.

The noun referring to the affecting entity is usually abstract, like ‘sleep’, ‘hunger’ or ‘thirst’, but can also refer to an animate being. Example (62) comes from a story in which the hunting protagonist encountered a Papuan black snake (Pseudechis papuanus), a venomous snake species notorious for its aggression. The storyteller relates how he was paralyzed with fear after he narrowly escaped, and how his companions described his condition:

| Obom | qébiägä | ada | da |

| [obom] O | [k͡pɪbiæɡ=æ] A | ada | da |

| him (3sg.acc) | Papuan_black=core | thus | int.dem |

| nagn. | |||

| naɡən | |||

| aux.pfv.npl.rec.3sg>3sg | |||

| ‘[They said,] “A Papuan black snake affected him like this.”’ | |||

| Idi (Sawe 2015: ln. 97) | |||

OAV word order is also a minority pattern encountered in analytic constructions, as exemplified below. Reported speech is introduced by an analytic construction combining the semantically empty form ada ‘like this; thus’ with an inflected auxiliary. When both the A and O arguments, the speaker and recipient of the speech act, respectively, are humans, both OAV and AOV orders are found: example (63) shows OAV order and (64) shows AOV. Across the board, AOV appears to be more common in analytic constructions.

| Bom | Kwandze | ada | gagn… |

| [bom] O | [kwandʒe] A | ada | ɡaɡən |

| me (1sg.acc) | personal_name | thus | aux.pfv.npl.rem.3sg>1sg |

| ‘Kwandze told me, “…”’ | |||

| Idi (James 2014: ln. 38) | |||

| Wigu | mladam | ada | nagn, | “Abe.” |

| [wiɡu] A | [mla-da-m] O | ada | naɡən | abe |

| personal_name | woman-poss.kin-acc | thus | aux.pfv.npl.rec.3sg>3sg | come.fut.2sg |

| ‘Wigu told his wife, “Come.”’ | ||||

| Idi (Purgä 2014: ln. 17) | ||||

Nevertheless, rather than a clear-cut divide between experiencer-object constructions and “regular” transitive constructions, there is a gradient scale on which constructions can be placed with respect to the affectedness and degree of volitionality of a human O argument relative to that of the A argument, which has a bearing on constituent order. This is furthermore governed by information structure: topical O arguments tend to be fronted, even when inanimate.

6.1.6 Grammaticalization of analytic constructions