Abstract

This study compares standard negation in the indigenous languages of South America to the rest of the world. We show that South American languages not only prefer postverbal negation to preverbal negation and negative morphology to syntax, but postverbal morphological negation to any other negation strategy. The predominance of this strategy makes South America distinct from other macro-areas. The study also considers the areal distribution of negation on the South American continent. It shows that negation strategies each have their own concentration area. Postverbal morphological negation, which is the dominant strategy, turns out to be concentrated in the northwest of the continent, with the highest density around the boundaries between Colombia, Peru and Brazil. We suggest that the preference for postverbal morphological negation in South America is likely to be the result of language-internal mechanisms of negation renewal, coupled with language contact.

Reviewed Publication:

For Pieter Muysken (1950–2021)

1 Introduction

Negation is a universal feature of human language, i.e., in every language there is the linguistic means to express the denial of a proposition. She hugs me – She doesn’t hug me. It was suggested as early as Jespersen (1917: 5) and has been confirmed by a number of typological studies (e.g. Dahl 1979: 91, 2010; Dryer 1988: 102, 2013b; Vossen 2016) that languages prefer to express negation as early as possible in the sentence, and specifically, before the verbal predicate. The general principle behind this tendency has been captured by such terms as ‘Neg Early’ (cf. Dahl 1979: 93; van der Auwera et al. forthcoming a, forthcoming b), ‘Negative-Before-Verb’ (Dryer 1988: 102), and ‘Neg First’ (Horn 1989). The tendency of languages to place the negative marker early in the sentence can be explained functionally. A negator constitutes a crucial part of the message, since it changes the value of a proposition to the opposite. As a hearer, we process the sentence in a linear way, as it comes in. It is more efficient for language processing and communication purposes to have a negative marker placed early in a sentence or, at least, before the verbal predicate (Dryer 1988: 102). A pseudo-English sentence Hug me not! demonstrates a postverbal negation pattern, which is functionally dispreferred, as it requires a reanalysis. Nevertheless, there are languages world-wide which put the negative marker late in the sentence. (1) and (2) are examples.

| Qawasqar[1] (Kawesqar) (qawa1238)[2] | ||||

| Fčakiáns | sa | čo | jéksor | k’élok |

| type.of.bird | top | 1sg | see | neg |

| ‘I don’t see a bird.’ | ||||

| (Aguilera and Tonko 2006: 34) | ||||

| Chibcha (Chibchan) (chib1270) | ||

| muysca | atabie | abgu- za |

| person | some | 3kill.erg.pst-neg |

| ‘He has not killed anybody.’ | ||

| (Quesada Pacheco 2012: 54) | ||

What is also intriguing is that languages with postverbal negation are not distributed completely randomly, but seem to cluster in certain areas. Three earlier cross-linguistic studies have hinted that the South American indigenous languages are particularly special. First, in a chapter on negation by Dryer (2013a) in the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS) we find a one-line observation that ‘[t]he largest concentration of languages with negative suffixes is in the northern half of South America’. Second, Muysken et al. (2014: 305–306) use data from WALS to explore the prominence of some typological features in South America in comparison to the rest of the world. It emerges from their analysis that among all grammatical features in WALS, the top three features that turn out to be overrepresented in South America concern the postverbal position of the negator and its morphological (bound) nature. Muysken et al. (2014: 305) explicitly state that their goal was merely to affirm the existence of features that are overrepresented in South America, and that they refrain from further commenting on the nature of the grammatical features in WALS. The third study which singles out South American languages with respect to negation is Vossen (2016: 307, 321), who notes that “only in South America, the frequency of postverbal single negation is higher than preverbal single negation”. However, Vossen’s dataset represents only part of the world.[3]

Thus the observations found in Dryer (2013a) and Muysken et al. (2014) involve a comparison of a particular phenomenon, viz. postverbal negation, across different geographical areas. As such, its overrepresentation in South America does not preclude that this type is still less numerous than other types in this part of the world, as these claims do not refer to the relative frequencies of the different types of negation in South America. Different from Dryer (2013a) and Muysken et al. (2014), the claim in Vossen (2016) compares postverbal and preverbal negation, but does not single out the morphological type of negation.

Another intriguing question concerns the areal distribution of negation within South America. The fact that Dryer (2013a) singles out its northern half from the rest of the world merits further exploration. Of course, Dryer’s phrasing ‘the northern half of South America’ is vague. How far south does this northern half stretch? How big and/or how dense does an area have to be in order to compete for being considered to have the largest concentration of postverbal morphological negators? In Muysken et al. (2014) the overrepresentation of the postverbal pattern and its morphological nature is noted in the context of South America as a whole, not specifically its northern part. The South American continent is known for its impressive genealogical as well as typological diversity (Adelaar 2012: 24; Campbell 2012: 59; Crevels 2012a: 168–169);[4] one would not expect to see this much convergence at the level of a continent or a large part of it.

All-in-all, the fact that the three mentioned studies, each with a different focus and scope, independently single out South American languages with respect to negation, and the fact that all observations are basically brief side-observations pointing in the same direction but saying somewhat different things, call for a focused study of the topic.

Thus the goal of the paper is two-fold. First, we examine the way negation is marked in South America compared to languages in the rest of the world. We investigate three parameters of variation: the position of negation in the clause, the morpho-syntactic status of negators, and the relation between the position and the morpho-syntactic status. Second, we study the areal distribution of the negation patterns in South America with the aim of finding out whether negation patterns show any areal concentration. In this way we contribute to the knowledge on areal patterns within South America, which can be indications of language contact.

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section (2), the data and methodology used in the study are presented. In Section 3 we introduce the categories and parameters in negation that are relevant for our study. In Section 4 we present our results. First, we compare negation patterns in South America to the rest of the world, and we then consider areal distribution of negation patterns within South America. In Section 5 we discuss our findings in a more general context. In Section 6 we consider the factors that can help explaining postverbal morphological negation in South America. Section 7 contains the conclusions.

2 Data and methodology

2.1 Data

In order to assess the characteristics and areality of negation in South America, we compiled an extensive dataset covering different parameters of negation for 221 South America languages across 77 families, with 40 families having more than one member and 37 isolates. Thus our sample covers 59% of the isolates in South America and 90% of the families. The number of families and isolates in our sample is close to the maximum for which relevant information is available to date. Unclassifiable languages are not part of the sample, since we lack information on negation for these languages. Unavoidably, some families are better represented than others, for the simple reason that some families are better described than others. To that extent our sample is still a ‘convenience sample’, a reminder aptly stressed by a reviewer. Also, unavoidably, the branching of the various families will have happened at various and usually unknown time depths. A factor – relevant for all datasets used in studies on negation – is that we do not know whether the expression and specifically the placement of negation is diachronically stable or variable and, if variable, what determines the (in)stability.[5] Nevertheless, our South American dataset differs favorably from the one in Dryer (2013a) in three ways. First, our dataset is almost twice as big as the South American dataset in Dryer (2013a). Second, a good number of high-quality grammars have become available since 2013, and today we can make use of around 40 good-quality descriptions unavailable to Dryer at the time of his study.[6] Third, our dataset constitutes a variety sample, i.e., serving the purpose of discovering linguistic diversity (Rijkhoff et al. 1993: 171; Miestamo 2005: 29, 2016). Like Miestamo (2005), we aim at genealogical stratification. Thus we choose languages as representatives from the lowermost node of a genealogical tree. For genealogy, as well as glossonyms, we mostly follow Glottolog (Hammarström et al. 2021), which represents a fair degree of consensus, but sometimes we follow the advice of experts where it differs from Glottolog. Like Miestamo (2005) we also pay attention to geography: whenever possible, we select representatives from different regions. Like Dryer (2013a), we take South America to begin at the Panama-Colombia border. Our entire dataset with negation strategies for 221 South American languages can be found in Appendix 1.

For the rest of the world (i.e., the world minus South America), we use the best available dataset, viz. the WALS dataset of Dryer (2013a).[7] We can make use of 1,190 languages for which both spatial reference and data on negation are available. Dryer (2013a) provides no information as to how languages in the dataset have been selected.[8]

2.2 Methodology

To be able to compare negation strategies in South America to the rest of the world, we first had to join our dataset for South America with data from WALS (Dryer 2013a). To do so, we recoded the values in WALS to have a uniform set of variables. For accessing WALS, merging both datasets, and for the spatial analysis and visualization of negation patterns, we mainly relied on the glottospace R package (Norder et al. 2022). To assess whether the spatial patterns of each negation strategy in South America differs from a homogenous Poisson process (Complete Spatial Randomness, CSR) we applied one-sided chi-squared goodness-of-fit tests for spatial clustering, using the quadrat.test function of the spatstat R package (Baddeley et al. 2015). With this approach we tested which quadrats are significantly larger than expected values, given a Poisson distribution. We applied chi-squared tests for varying numbers of quadrats. To reflect the shape of South America, we varied the number of quadrats in the East-West direction between 1 and 5, and multiplied those by 1.5 to obtain the number of quadrats in the North-South direction (rounded upwards to whole numbers). To identify possible hotspots where particular negation strategies are clustered, we generated kernel density maps for each of the four negation strategies in South America. The density in each cell was estimated using a Gaussian kernel function. To assess the sensitivity of our findings to the chosen function, we also fitted a quartic kernel function. This was implemented using the density.ppp function from the spatstat R package (Baddeley et al. 2015). Rather than setting a fixed bandwidth, the smoothing bandwidth (sigma) for kernel estimation was selected using likelihood cross-validation, as implemented in the bw.ppl function in spatstat (Baddeley et al. 2015). Additional spatial data were obtained from Natural Earth (South 2017), and visualization was further enabled by the following R (R Core Team 2021) packages: glottospace (Norder et al. 2022), ggplot2 (Wickham 2016), sf (Pebesma 2018), and tmap (Tennekes 2018).

3 Negation: categories and parameters

This paper focuses on standard negation, i.e., the negation of an overt verbal predicate in a main clause declarative sentence (Miestamo 2005; Payne 1985). Other kinds of negation are not considered, unless otherwise noted, and thus the term ‘negation’ will be used for ‘standard negation’, and the term ‘negator’ for ‘standard negator’.

3.1 Exponence

Languages world-wide tend to express semantically simple negation with a single negator. We see this in the worldwide sample of 179 languages by Van Alsenoy (2014: 190): 149 languages (83%) have a single exponence strategy only. A ‘single negation’ strategy can be seen in examples (1) and (2) above. Some of the world’s languages, however, may or must use two negators, and these may or may not ‘embrace’ the verb. A pattern where two negators are either possible or obligatory will be considered as ‘double negation’, illustrated in (3).

| Yucuna (Arawakan) (yucu1253) | ||

| unka | pi=amá- la -je | o’wé |

| neg | 2sg=see-neg-fut | brother |

| ‘You will not see (my) brother.’ | ||

| (Lemus Serrano 2020: 13) | ||

There are also languages that may use three negators, and some – even four and five (see Doornenbal 2009: 271; Vossen 2016: 35), but the latter categories are marginal.

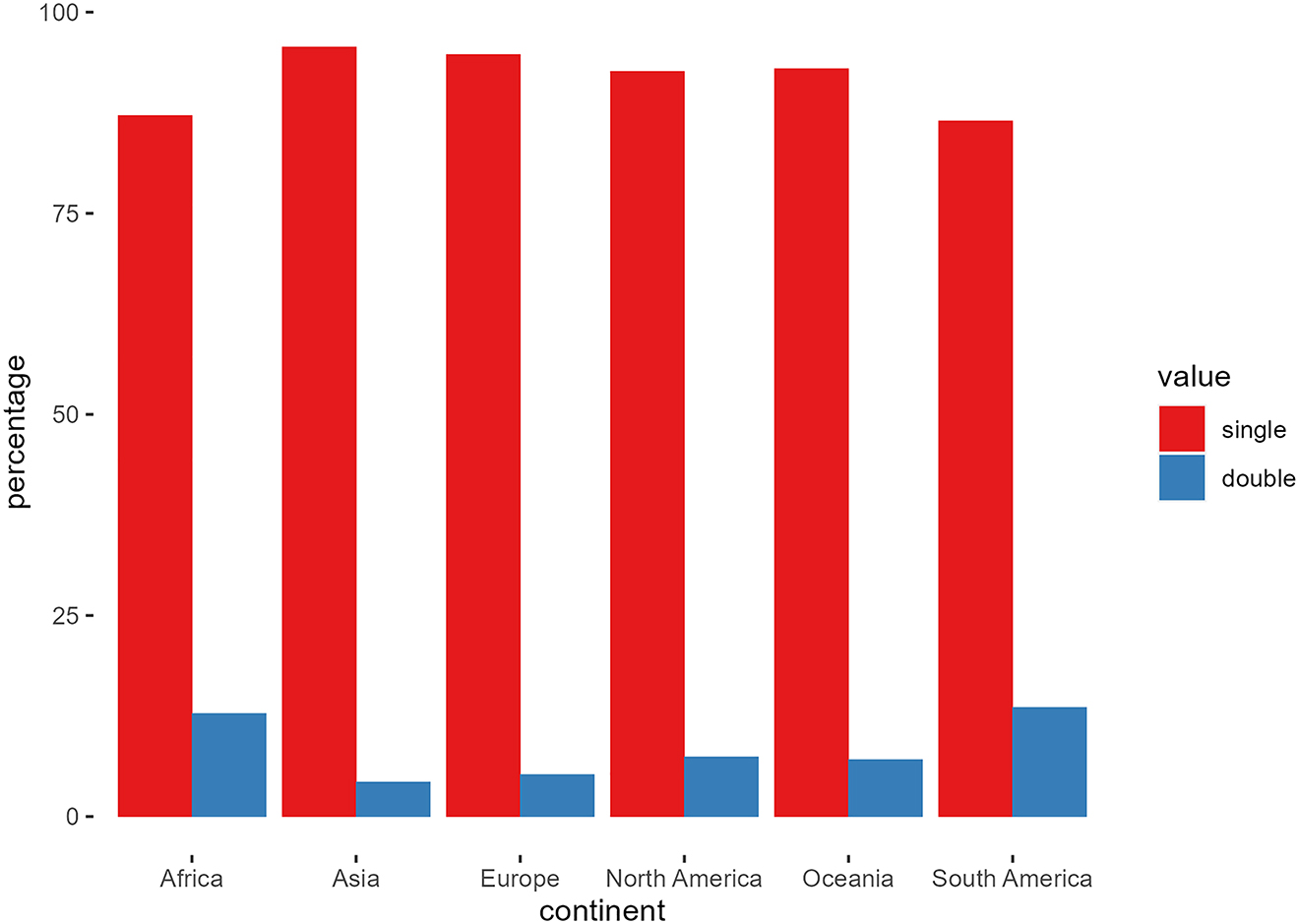

Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution of single versus double negation in the world’s languages. There are no languages in South America that use three or more negators for standard negation. For this reason and for the reason that triple negation occurs in only six languages out of 1,325 languages in Dryer (2013a) (three of which are in Africa and three in Oceania), triple negation is removed from the dataset.

Distribution of single versus double negation. Data for South America were compiled specifically for this study (Appendix 1); data for the rest of the world were obtained from Dryer (2013a).

Double negation will be considered only in the comparison of the position of negators. For the other analyses, we leave languages with double (and triple) negation aside. The main reason is that Dryer’s (2013a) data on double negation are difficult to assess and compare in a straightforward way. This is not an issue, however, given that the great majority of the world’s languages use a single negator.

It should also be mentioned that the numbers for single negation include such a rare strategy as optional single negation. Dryer (2013a) reports it only for one language in his dataset (Wyandot). In our South American sample two languages are found with this strategy: Karitiana (Tupian) and Movima (isolate).[9]

3.2 Position

Languages that use a single negator force a choice between the preverbal and the postverbal positioning of the negator. The terms ‘preverbal’ and ‘postverbal’ will here be used in the wide sense that encompasses the placement of a negator before or, respectively, after the verb, whether the negator is a syntactic (free) element or a morphological (bound) one, i.e., an affix. The use of these terms in the wide sense is not controversial, but Dryer (2013a) and Muysken et al. (2014) use the wide sense too. There is more to be said, however. First, standard negation may require the use of a positive auxiliary.[10] For example, in our South American sample, 27 languages use such auxiliaries. In studies on negation, there are two approaches as to what type of verb is taken as the reference point, i.e., the lexical verb (e.g. in Dryer 2013a) or the auxiliary, when there is one (e.g. in Dahl 1979, 2010; Miestamo 2005; Vossen 2016). In this study, we take the lexical verb as the reference point.[11] In (4) below the negator is thus postverbal, for it follows the lexical verb.

| Amarakaeri (Harakmbut) (amar1274) | ||

| WettoneɁ-mey | mba-tiaway- we | õn-mã- ẽ -mẽ-tẽ |

| woman-coll | vpl-see-neg | 3pl.ind-vpl-be-rec.pst-nvis |

| wa-mationka-eri-ta | ||

| nmlz-hunt-an-acc | ||

| ‘The (group of) women didn’t find the hunters.’ | ||

| (Van linden forthcoming) | ||

The same is true in (5) and (6). In (5) the negator follows the auxiliary, and in (6) the order is reversed, but in both, the negator follows the lexical verb. The two languages are thus classified in the same way.

| Culina (Arawan) (culi1244) | ||

| ethe | khi | o- na - hara -pa |

| dog | see | 1sg-aux-neg.m-pst |

| ‘I didn’t see the (male) dog.’ | ||

| (Dienst 2014: 83) | ||

| Kanoê (isolate) (kano1245) | ||

| aj | ja | õ- k -e- re |

| 1sg | want | 1-neg-decl-aux |

| ‘I don’t want.’ | ||

| (Bacelar 2004: 216) | ||

There are languages, however, that have more than one pattern. If one pattern involves a single negator in the preverbal position, and another pattern – a single negator in the postverbal position, as in (7) – we call it ‘asymmetric dual patterning’. This parameter is relevant for the analysis in Section 4.1.1.

| Paumarí (Arawan) (paum1247) |

| iniani, | o-noki-ri-hi | ida |

| no | 1sg-see-neg-theme | dem.f |

| ‘No, I haven’t seen it.’ | ||

| (Chapman and Derbyshire 1991: 202) | ||

| iniani, | ni=o-noki-ki | ida |

| no | neg=1sg-see-ntheme | dem.f |

| ‘No, I haven’t seen it.’ | ||

| (Chapman and Derbyshire 1991: 202) | ||

There are also languages which have more than one pattern, but the difference lies in the types of negators involved, independent of their position. This is illustrated with Sirionó, where one pattern involves a morphological negator and the other pattern a syntactic negator. Such cases are treated as ‘mixed’ negation. This parameter is relevant for the analysis in Section 4.1.2.

| Sirionó (Tupian) (siri1273) |

| a-mae-ä-te | e-rese | |||

| 1sg-see-neg-intns | 3-obl | |||

| ‘I haven’t seen it.’ | ||||

| (Priest and Priest 1980 in Dahl 2014: 122) | ||||

| papa | ke | se-mbu-tiarö | eä | nda |

| father | dk | 1sg-caus-grow | neg | fm |

| ‘My father didn’t raise me.’ | ||||

| (Dahl 2014: 122) | ||||

3.3 Morpho-syntactic status

Negation can be overtly expressed by morphological or syntactic negators, or by a combination of these. There is a rarer strategy involving a combination of morphological negators and tone, and a very rare case where only tone functions as a negator (see Dryer 2013a).[12] In the South American sample there is one language where tone combines with a morphological negator (viz. Mamaindê (Nambiquaran), Eberhard 2009: 437). We categorized this language as having double negation following Dryer (2013a) for similar cases.

Morphological negators are realized as affixes. These are either postverbal (suffixal), as in Mapudungun (9), or preverbal (prefixal), as in Sanapaná (10).

| Mapudungun (Araucanian) (mapu1245) | ||

| kuyfi | kütu | pe- la -eyu |

| long.ago | since | see-neg-1sg>2sg |

| ‘I have not seen yousg in a long time.’ | ||

| (Zúñiga 2000: 56) | ||

| Sanapaná (Lengua-Mascoy) (sana1298) | ||||

| m -o-vet’-o | mokham | meyva | ||

| neg-1-see-irr | still | lion | ||

| ‘I haven’t seen a lion yet.’ | ||||

| (Van Gysel in preparation, p.c.) | ||||

There is a single case of a language, Itonama, where monosyllabic verbs use the negative prefix (11a), while disyllabic and polysyllabic verbs use the negative infix (11b), in both cases formally realized as a glottal stop (Crevels 2012b: 257). The differences between the affirmative and negative sentences are the insertion of the negator before the last syllable of the verb stem, the addition of a relativizer mi-/ni-, which creates a nominalized form, and the addition of a dependent verb stem marker instead of the independent marker in the affirmative form. Finally, a dependent Subject or Agent cross-reference marker is used instead of the independent markers in the affirmative forms (M. Crevels, p.c.). Note, however, that monosyllabic verbs are rare in Itonama (M. Crevels, p.c.), and thus the corresponding strategy is found only marginally.

| Itonama (isolate) (iton1250) |

| dih-ni-ka-’-mo’-na-mo |

| 2pl-rel-face-neg-hit-neut-1 |

| ‘You guys don’t hit me (in the face).’ |

| (M. Crevels, p.c.) |

| wase’wa | a’-mi-ya<’>ka-na | machiriri |

| yesterday | 2sg-rel-sing/read<neg>sing/read-neut | paper |

| ‘Yesterday you were not reading the book.’ | ||

| (Crevels 2012b: 258) | ||

Clitics are an in-between category. Following Dryer (2013a) we treat clitics as syntactic elements. Particles are a second type of syntactic negators. Both clitics and particles can be either postverbal or preverbal. Finally, there are negative verbs. In Payne (1985) two types of negative verbs are distinguished, viz. higher negative verbs and negative auxiliaries. The former subordinates a lexical verb, which occurs in a complement clause, and the clausal boundary is clear. We may see this in Nivaclé (12). Though the negator has no inflection, it has future semantics and there is a subordinator.

| Nivaclé (Matacoan) (niva1238) | ||

| tan | ca | ja-vo-’a-ch’e |

| neg.fut | sub | 1s-follow-2-long |

| ‘I will not go with you.’ | ||

| (Fabre 2016: 370) | ||

We assume that many, if not all, languages can resort to periphrasis with negative verbs (see also Dahl 1979: 80–81). Therefore we count the negative verb strategy only when it is the main or the only strategy available for expressing negation, as far we can judge from the grammar. Example (13) from the Ecuadorian variety of Siona illustrates a negative auxiliary.[13] In the Ecuadorian variety (as opposed to the Colombian variety) the pragmatically unmarked strategy, i.e. standard negation, involves the use of a negative auxiliary bã ‘not.be’ (M. Bruil, p.c). Verbal inflections occur on the auxiliary and the lexical verb takes the general classifier -je/-e, functioning here as an event nominalizer (Bruil 2019: 396). A literal translation of (13) would be ‘your meat making is not’ – with ‘meat making’ expressing the idea of hunting.

| Siona, Ecuadorian variety (Tucanoan) (sion1247) | ||||

|

m |

wa’i | ne-je |

bã-k |

m |

| 2sg | meat | make-clf:gen | neg.cop-sg.m.prs-ds | 2sg=wife |

|

b |

m |

jo’-doha-i-k |

|||

| be.angry-ipfv-sg.f.prs-ds | 2sg | do-wander-ipfv-2/3sg.m.prs.nassrt | |||

| ‘You are walking around here, because your wife got mad, because you don’t hunt anything?’ | |||||

| (Bruil 2014: 204, p.c.) | |||||

As Payne (1985: 207) notes, there is no sharp boundary between negative verbs and negative auxiliaries due to a natural diachronic connection between them.

Not only is the distinction between negative verbs and negative auxiliaries often not clear, it may also be difficult to separate them from negative particles (see also Dryer 2013a). However, this is not an issue for us, for, like Dryer (2013a), we treat negative verbs, negative auxiliaries, negative particles and negative clitics all in the same category, that of the ‘syntactic negator’.

4 Results

In this section we present results of a comparison between negation in South America and in the rest of the world (Section 4.1). We focus on three parameters: i) the position of the negator in the clause, ii) the morpho-syntactic status of the negator, and iii) the relation between the position and the morpho-syntactic status. Then we offer the results of the areal distribution of negation patterns in South America (Section 4.2).

4.1 Negative marking in South America versus the rest of the world

4.1.1 The position of the negator

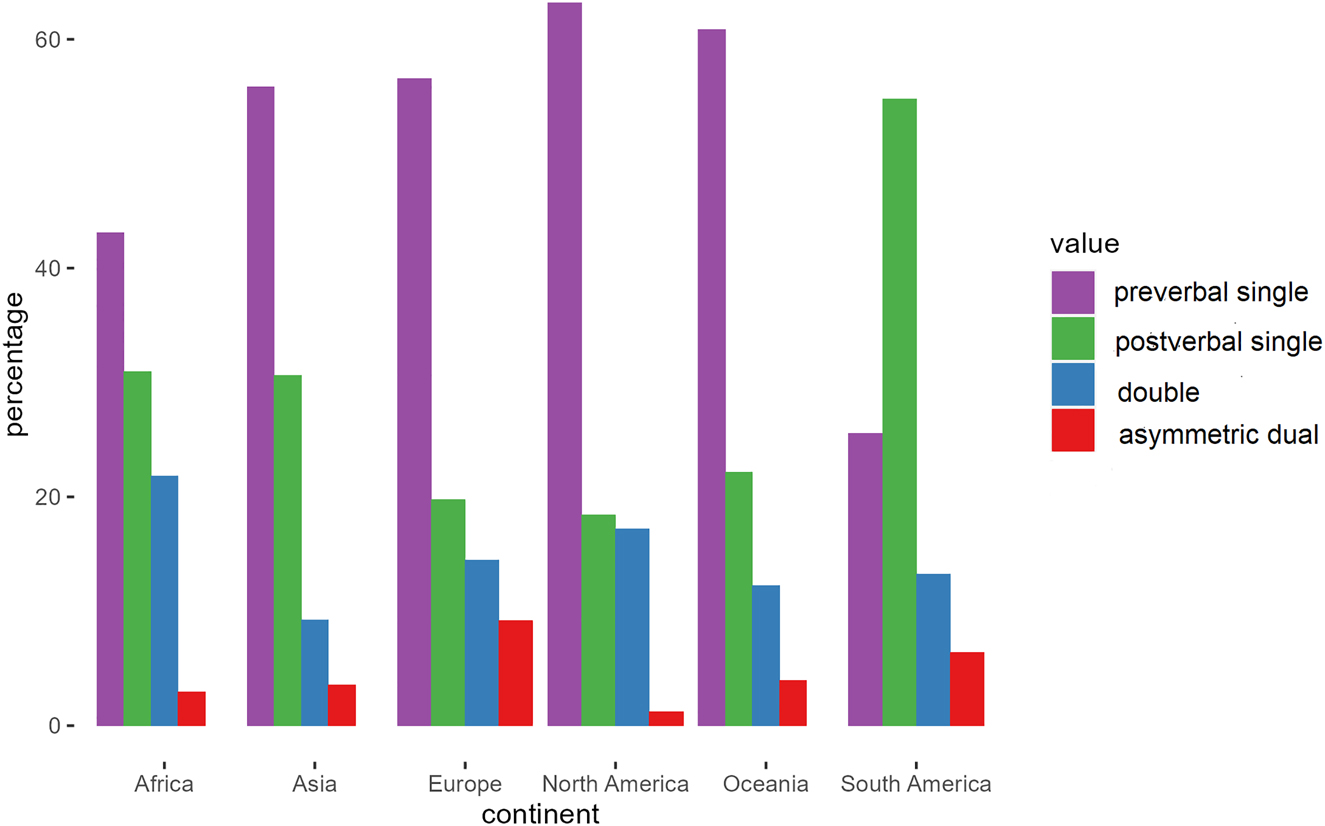

Languages of all continents except South America favor preverbal single negation (Figure 2). The preference is particularly strong in North America, Oceania, Europe, and Asia. In South America, preverbal single negation is not the preferred strategy, occurring only in 26% of the sample.

Distribution of preverbal single, postverbal single, double, and asymmetric dual negation. Data for South America were compiled specifically for this study (Appendix 1); data for the rest of the world were obtained from Dryer (2013a).

A pattern which is second in frequency on all continents except South America is postverbal single negation. It is almost two times less frequent in Asia (56 vs. 31%) and almost three times less frequent in Europe (57 vs. 20%), North America (63 vs. 18%), and Oceania (61 vs. 22%). In Africa the difference in frequency is less strong (43 vs. 31%), but it is present nevertheless. In South America, however, postverbal single negation is the dominant pattern, found in 55% of the sample. Thus the preverbal versus postverbal single patterns show an almost opposite distribution in South America versus the rest of the world.

The frequency of double negation in South America (13%) is not much different from the rest of the world; although some continents, like Africa (22%), show more of this pattern than others (e.g. Asia, 9%).

The frequency of the asymmetric dual strategy is highest in Europe (9%), followed by South America (6%). For the other continents, the numbers hover between 3 and 4%.

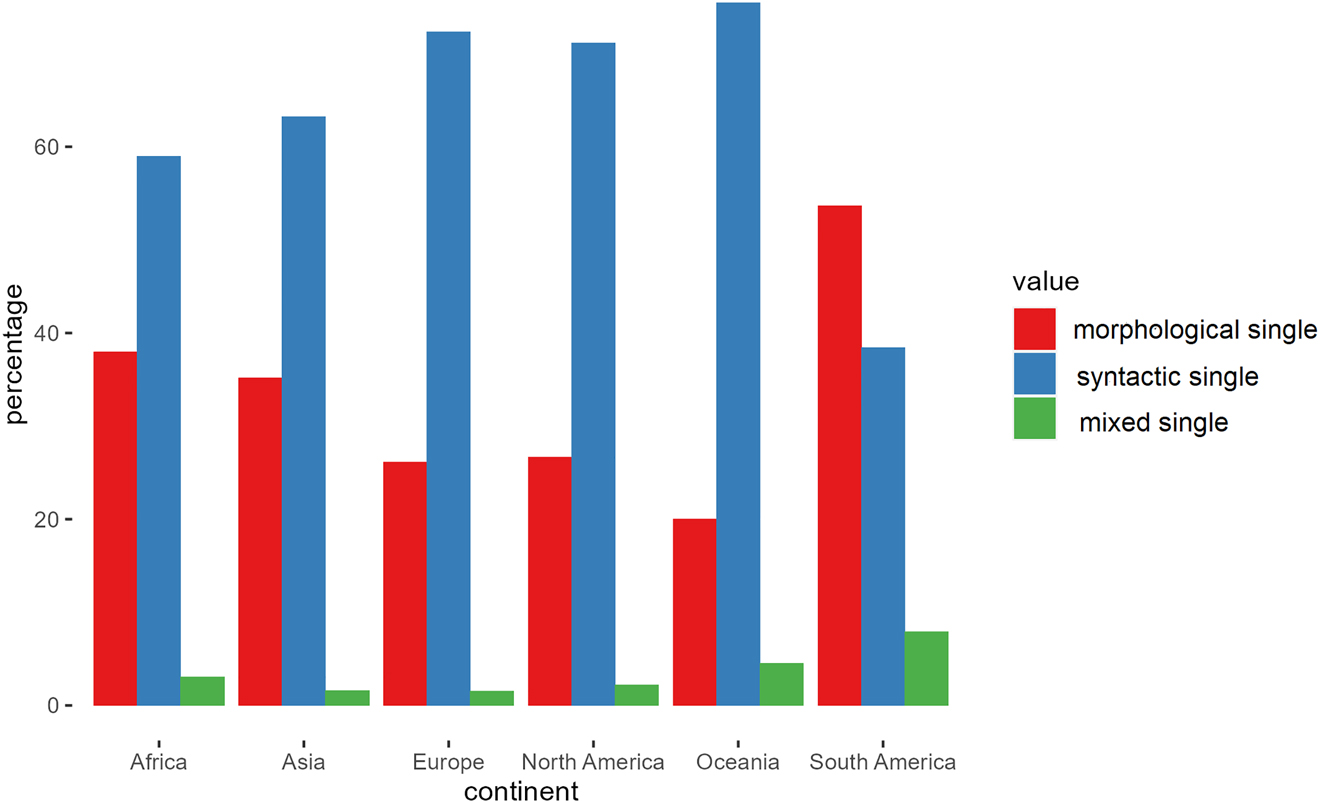

4.1.2 The morpho-syntactic status of the negator

Languages of all continents except South America prefer syntactic negators (Figure 3). The highest number is found in Oceania (75%), followed by Europe (72%), North America (71%), Asia (63%), and Africa (59%). In South America, syntactic negators account for only 38% of cases. Morphological negators, on the other hand, constitute the most frequent strategy in South America, found in 54% of cases. In the rest of the world, morphological negators are less common: they account for 38% of cases in Africa, 35% in Asia, 27% in North America, 26% in Europe, and only 20% in Oceania. We can also notice that the difference between the preferred and dispreferred strategies is highest in Oceania, but least so in South America. Languages with mixed single negation are generally infrequent. However, it is noteworthy that such languages turn out to be relatively more frequent in South America (8%), followed by Oceania (5%), Africa (3%), and Asia (2%), Europe (2%) and North America (2%).

Distribution of morphological versus syntactic versus mixed negation strategies among languages with single negation. Data for South America were compiled specifically for this study (Appendix 1); data for the rest of the world were obtained from Dryer (2013a).

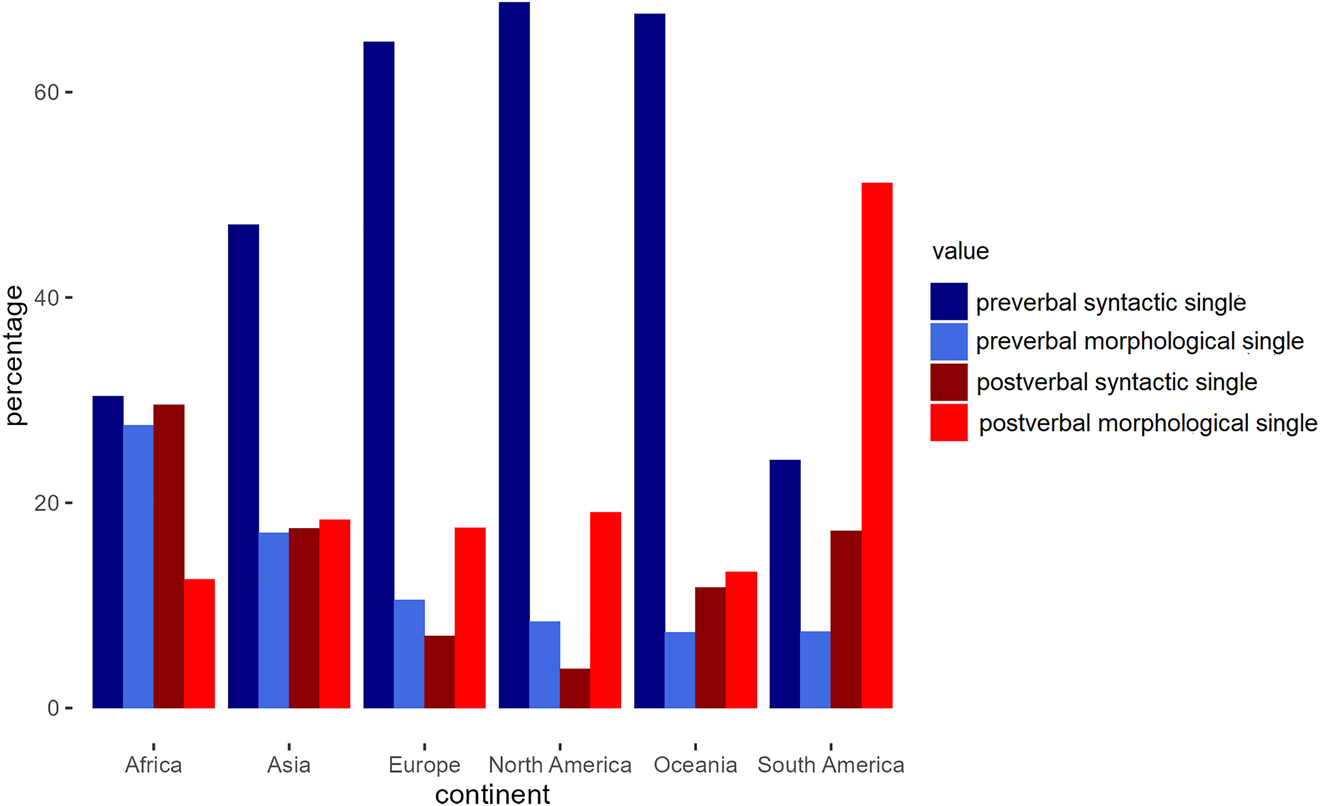

4.1.3 Position and morpho-syntactic status

In previous sections we dealt separately with the position of the negators and their morpho-syntactic status; we now combine them (Figure 4).

Distribution of preverbal syntactic, preverbal morphological, postverbal syntactic and postverbal morphological patterns among languages with single negation. Data for South America were compiled specifically for this study (Appendix 1); data for the rest of the world were obtained from Dryer (2013a).

The first thing to notice is that languages of most continents clearly prefer preverbal syntactic negation to the other means: North America (69%), Oceania (68%), Europe (65%), and Asia (47%). The preference is particularly strong in the first three macro-areas, as the frequency of preverbal syntactic negation lies there around 69–65%. In Africa, preverbal syntactic is most frequent too, but its occurrence is not much higher than the occurrence of either postverbal syntactic or preverbal morphological pattern. The lowest occurrence of preverbal syntactic negation in the world is found in South America (24%).

Second, it becomes evident that postverbal morphological negation is the preferred strategy in South America. In that part of the world, postverbal morphological negation accounts for 51% of cases, whereas in the rest of the world its occurrence hovers between 19% (in North America, Asia, and Europe) and 13% (in Africa and Oceania). In South America, postverbal morphological negation is almost twice as frequent as the preverbal syntactic negation (the second most frequent strategy on the continent).

Third, while South America clearly prefers morphological negators as shown in Figure 3, this only concerns negators in the postverbal position. It becomes evident from Figure 4 that morphological negators in the preverbal position constitute the least frequent negation strategy in South America. Morphological negation accounts for only 7% of cases. The occurrence of preverbal morphological negators is similarly low in Oceania (7%), North America (8%), and Europe (11%). However, it is more frequent in Asia (17%) and even more so in Africa (28%) (see also Dryer 2013a).[14]

Fourth, it can be noticed that postverbal syntactic negation shows quite different distributions across the continents. While it is most present in Africa, as also stated in Dryer (2013a), accounting for about 30% of cases in Africa, it is least common in North America, found in only 4% of cases. In South America, it is the third most frequent strategy, found in 17% of cases.

Finally, the type of the least frequent strategy is quite different per continent. In South America, as well as in Oceania, it is preverbal morphological negation. In North America and Europe, it is postverbal syntactic. In Africa, postverbal morphological is least frequent. In Asia, all three patterns other than preverbal syntactic are equally infrequent.

4.2 Areal distribution of negation strategies in South America

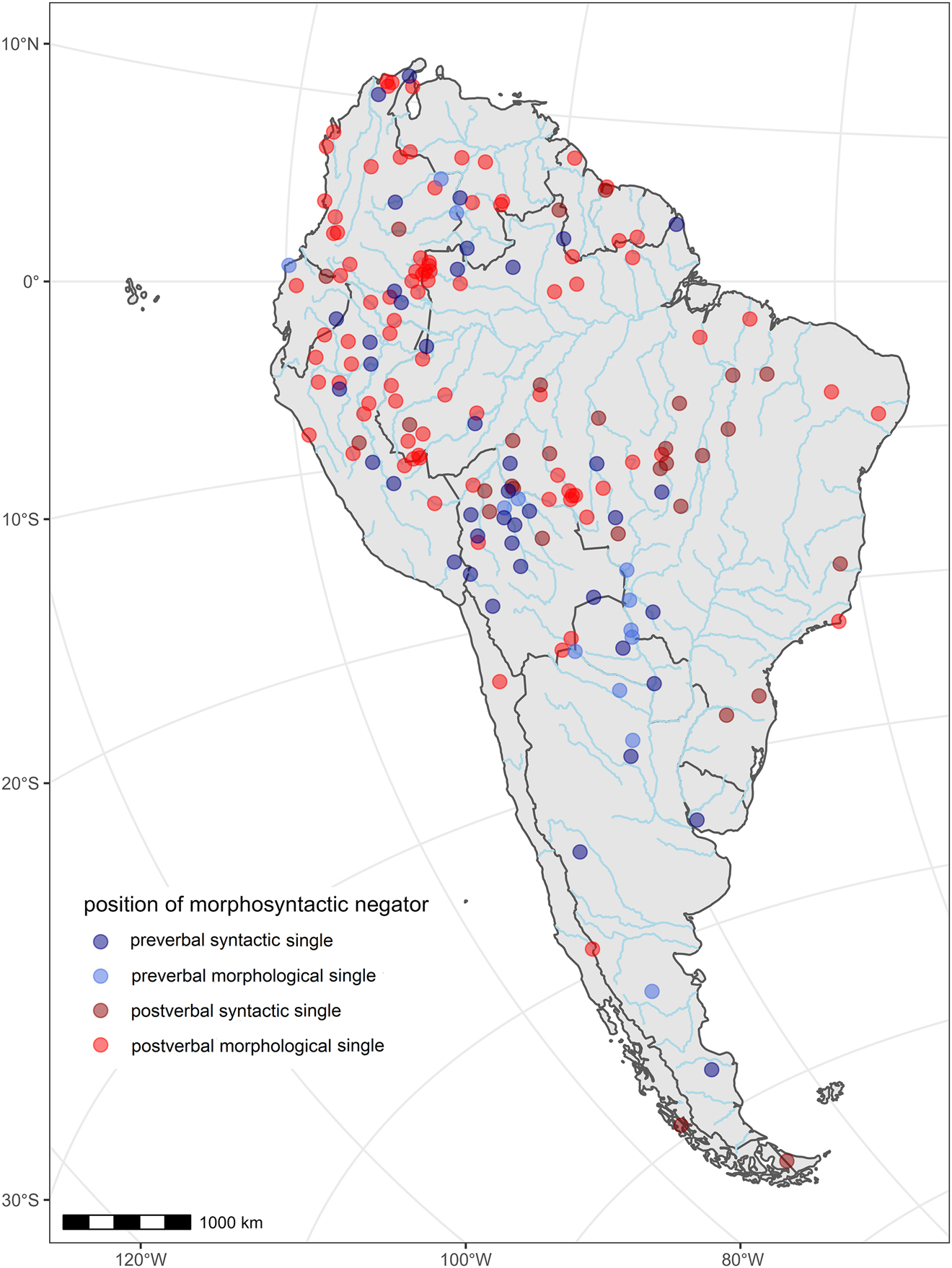

In this section we zoom in on South America and present our findings regarding the areal patterns of negation marking. The distribution of the four main negation strategies (viz. preverbal syntactic, preverbal morphological, postverbal syntactic, and postverbal morphological) is shown in Figure 5.

Distribution of four major negation strategies in South America (Azimuthal Equidistant projection). Note that this map only includes languages with single negation that have only one negation strategy, thus leaving aside languages with asymmetric dual patterning and those with mixed negation. The number of languages included on the map amounts to 174, distributed as follows: postverbal morphological negation (89 languages), preverbal syntactic (42), postverbal syntactic (30), and preverbal morphological (13).

Figure 5 obviously does not show whether particular negative strategies are spatially clustered. But we can do better. The chi-squared goodness-of-fit tests for spatial clustering (Table 1) indicate that for the number of quadrats tested, postverbal morphological and preverbal syntactic patterns differed significantly from the null hypothesis in 5/5 and 4/5 cases, showing that their distribution is non-random for the majority of cases. In contrast, postverbal syntactic and preverbal morphological differed from the null hypothesis in only 2 and 1 out of 5 cases, respectively. Those negation strategies that differ from a random pattern least often are also the negation strategies for which few data are available. Consequently, the expected counts in some quadrats will be small, suggesting care should be taken when interpreting chi-squared test statistics for these negation strategies.

Results of one-sided chi-squared goodness-of-fit tests for spatial clustering.

| Negation strategy | (nx1, ny2) | (nx2, ny3) | (nx3, ny5) | (nx4, ny6) | (nx5, ny8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preverbal syntactic | n.s. | * | ** | ** | *** |

| Preverbal morphological | n.s. | n.s. | ** | n.s. | n.s. |

| Postverbal syntactic | * | n.s. | n.s. | * | n.s. |

| Postverbal morphological | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

-

Significance levels: n.s. = p > 0.05; * = p ≤ 0.05; ** = p ≤ 0.01; *** = p ≤ 0.001.

As a logical consequence of the number of languages that use a particular negation strategy, the intensity (λ, the number of points per unit area, in this case South America) is highest for postverbal morphological negation, intermediate for preverbal syntactic and postverbal syntactic, and lowest for preverbal morphological. Kernel density maps (Figures 6–9) show, for each negation strategy, the density of languages on a smooth surface. For each of the four negation strategies, we fit models using two different kernel functions. Overall, the patterns derived from the Gaussian function (Figures 6–9) and the quartic function were highly similar. The latter can be found in Appendix 3.

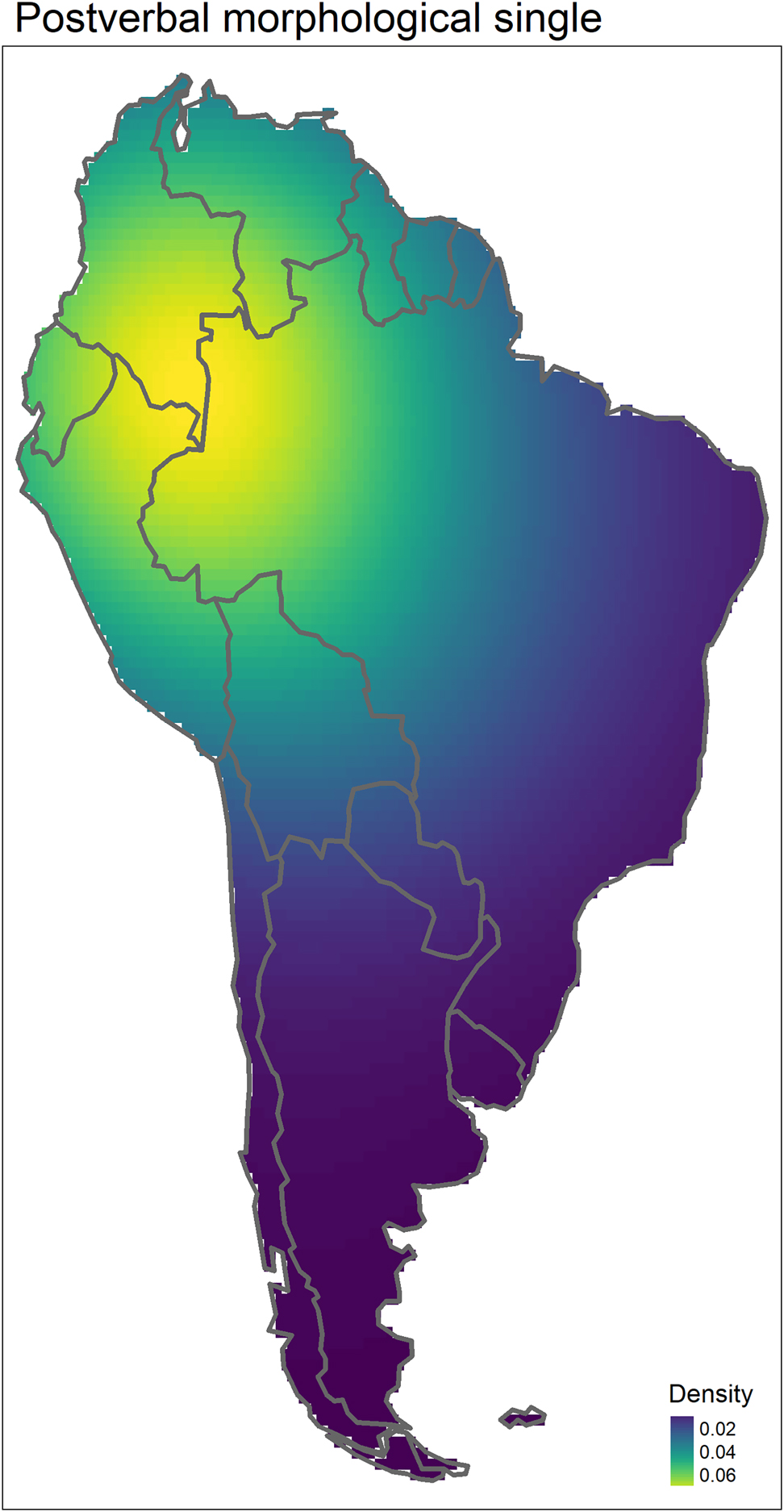

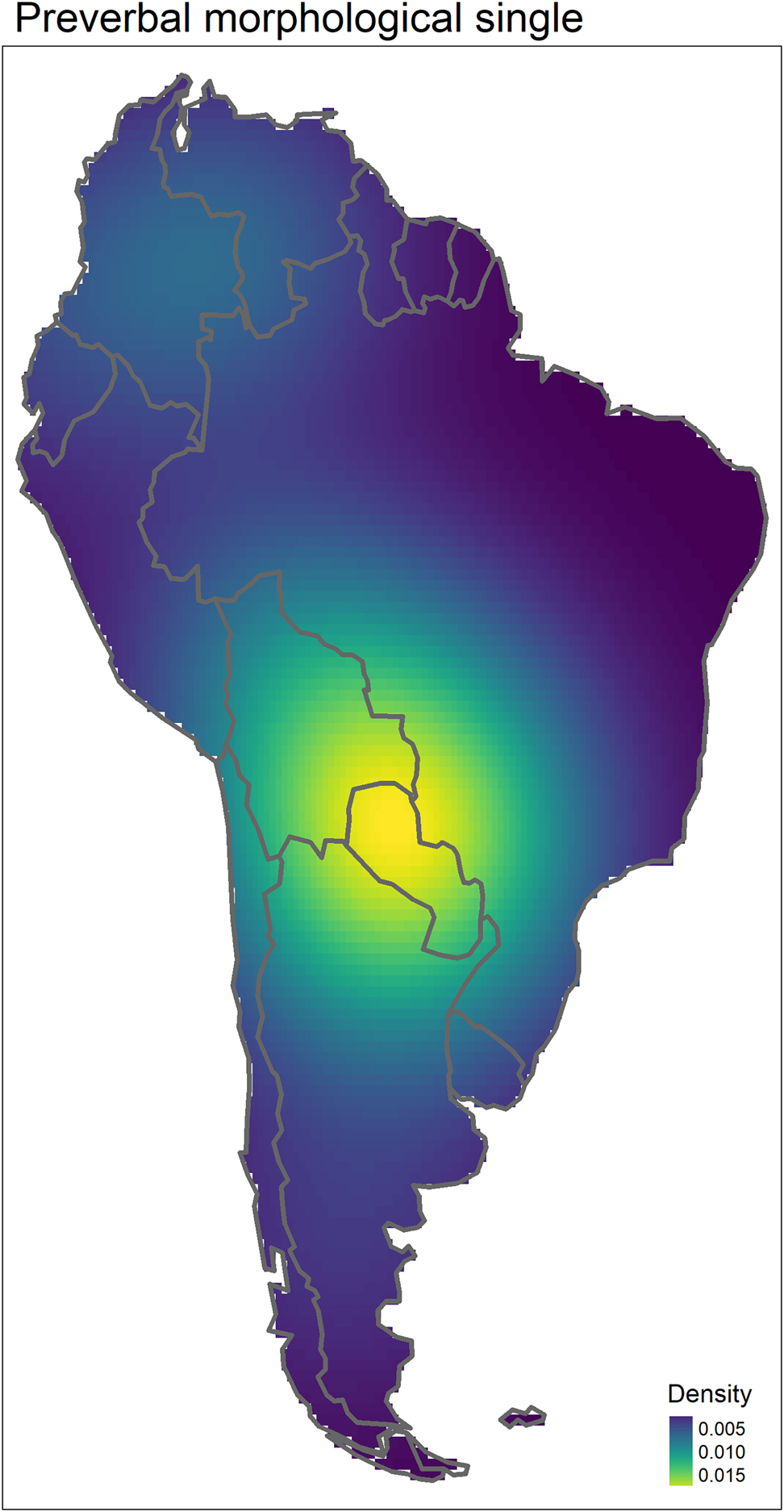

Kernel density map for the postverbal morphological single pattern. Yellow color indicates the highest density and blue color indicates the lowest density. Densities are given in number of points per square kilometer, multiplied by 104 to increase readability. The map is in Eckert IV global equal area projection (cell size ∼2200 km2). Models were fitted using a Gaussian kernel function (for maps created using a quartic kernel function, see Appendix 3).

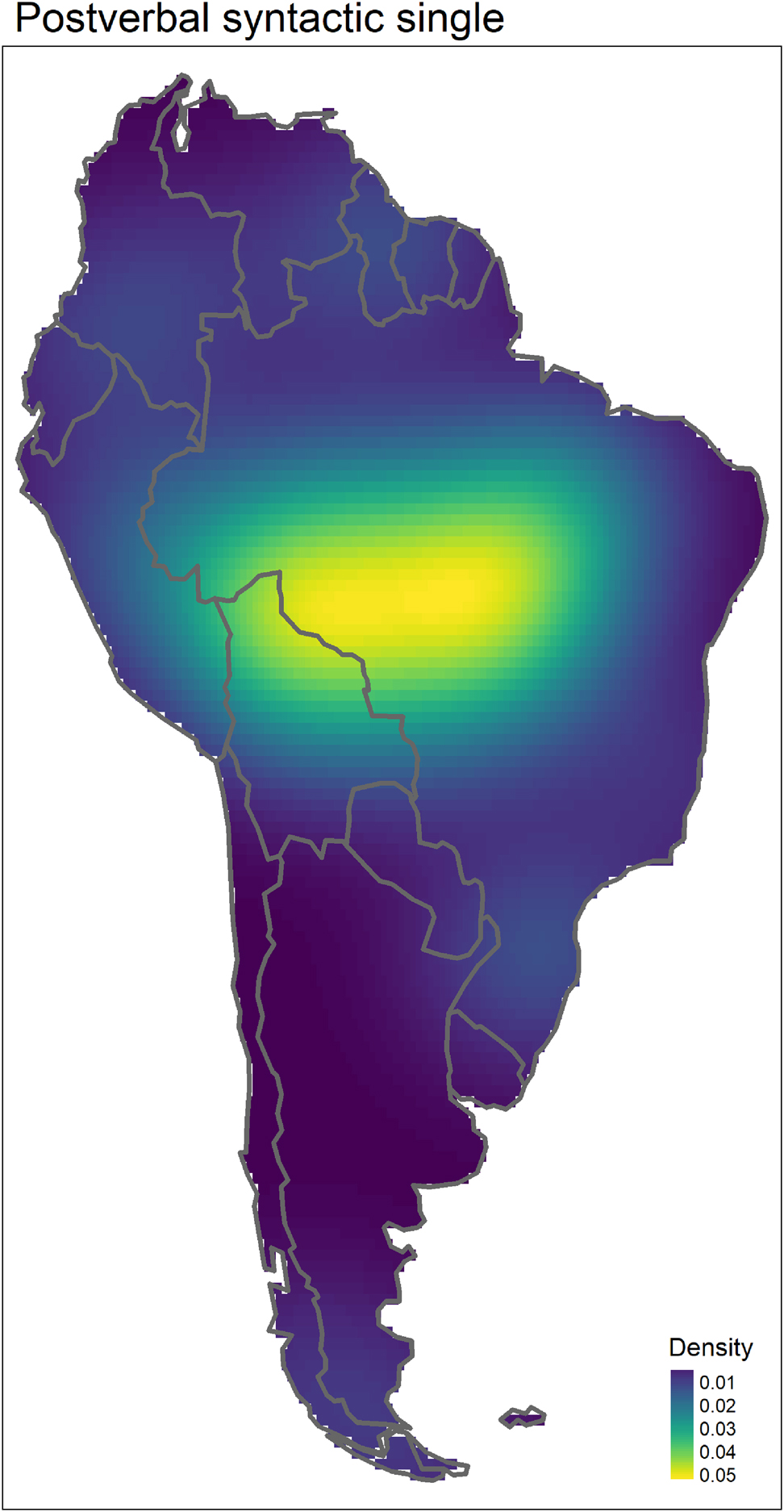

Kernel density map for the postverbal syntactic single pattern. Yellow color indicates the highest density and blue color indicates the lowest density. Densities are given in number of points per square kilometer, multiplied by 104 to increase readability. The map is in Eckert IV global equal area projection (cell size ∼2200 km2). Models were fitted using a Gaussian kernel function (for maps created using a quartic kernel function, see Appendix 3).

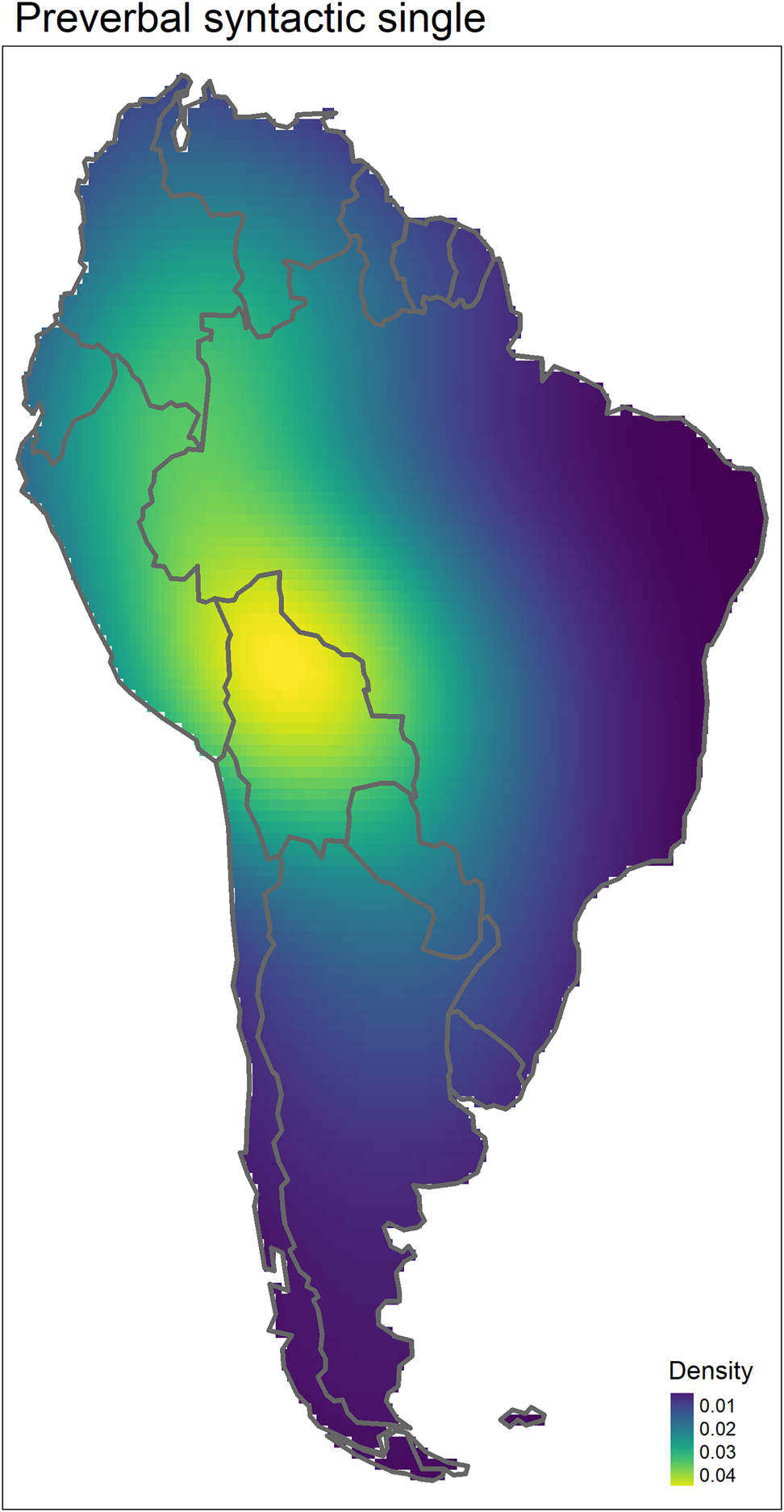

Kernel density map for the preverbal syntactic single pattern. Yellow color indicates the highest density and blue color indicates the lowest density. Densities are given in number of points per square kilometer, multiplied by 104 to increase readability. The map is in Eckert IV global equal area projection (cell size ∼2200 km2). Models were fitted using a Gaussian kernel function (for maps created using a quartic kernel function, see Appendix 3).

Kernel density map for the preverbal morphological single pattern. Yellow color indicates the highest density and blue color indicates the lowest density. Densities are given in number of points per square kilometer, multiplied by 104 to increase readability. The map is in Eckert IV global equal area projection (cell size ∼2200 km2). Models were fitted using a Gaussian kernel function (for maps created using a quartic kernel function, see Appendix 3).

As can be seen from the maps, postverbal morphological single negation (Figure 6) has the highest density in the northwest of the continent, with the highest concentration around the boundaries between Colombia, Peru and Brazil. Postverbal syntactic single negation (Figure 7) is concentrated mainly in the central part of Brazil up to the border with Bolivia. Preverbal syntactic single negation (Figure 8) shows the highest density in the northern part of Bolivia; a relatively high concentration is also found in the area stretching up northwards along the eastern part of Brazil and the western part of Peru. Preverbal morphological negation (Figure 9) is primarily concentrated around the northern part of Paraguay, northeast Argentina and the southeast of Bolivia, which approximately corresponds to the geographical region known as ‘Grand Chaco’.

5 Discussion

If we compare negation strategies in South America to those of the rest of the world, we can note at least three things.

First, we can confirm and substantiate the earlier observation of Vossen (2016), which was based on data from only part of the world: as compared to the other macro-areas, South America prefers postverbal negation over preverbal negation (see Figure 2).

Second, we can confirm that South America overrepresents morphological negators (Muysken et al. 2014: 306), as compared to the rest of the world. The distribution of morphological versus syntactic negation (if we abstract from its position) in South America is almost the opposite of what we find in the rest of the world (see Figure 3). However, the preference for morphological negators in South America concerns only the negators in the postverbal position (see Figure 4). In this respect it is interesting that, if all continents are taken together, Dryer (2013a) finds no “significant difference between the frequency of negative prefixes and negative suffixes”. He attributes this to “the general crosslinguistic suffixing preference, which competes with the preference for preverbal negative morphemes, thus resulting in roughly equal numbers of the two types of languages with negative affixes” (Dryer 2013a). We do not object to the idea of a competition between the Neg Early principle and the cross-linguistic preference for suffixes. However, as one can see in Figure 4, negative prefixes are frequent mainly in Africa, and to some degree in Asia, but they are infrequent elsewhere; negative suffixes are frequent only in South America, and are infrequent elsewhere. Thus there is a clear geographical skewing in the distribution of languages with negative prefixes and with negative suffixes. Therefore conclusions on the worldwide lack of a significant difference between the frequency of negative prefixes and negative suffixes need to be taken with care.

Third, we can state that South American languages clearly prefer the postverbal morphological negation strategy to any other strategy. The predominance of this negation pattern sets the South American continent apart from the rest of the world, as this is among the least common strategies in the non-South America part of the world (Figure 4).

With regard to the areal distribution of negation patterns in South America, we can note the following.

First, the most common negation strategy in South America, i.e. postverbal morphological single negation, shows a high density in the whole northwestern part of the continent, with the highest density around the boundaries between Colombia, Peru and Brazil (Figure 6). Among 77 language families (including 37 isolates) represented in our sample, postverbal morphological negation is found in 45 families (including 20 isolates), which corresponds to 58% of the genealogies in the sample. The fact that more than half of the South American language families have postverbal morphological negation calls for a consideration of the role of language contact in this spread. Appendix 2 offers an overview of genealogies with postverbal morphological negation. At least in the following language families (having more than one member and represented in the sample with more than one language), postverbal morphological negation is the dominant strategy and seems to be genealogically anchored: Pano-Tacanan, Tucanoan, Cariban, Chibchan (spoken in South America), Nambiquaran, Arawan, Barbacoan, Chicham, Chocoan, Saliban, Naduhup, Yanomaman, Boran and Huitotoan.

Second, postverbal syntactic single negation is concentrated in the central part of Brazil up to the border with Bolivia (Figure 7). The languages spoken in this area are primarily Macro-Je languages, but we also see the Tupian languages Gavião,[15] Karitiana, Karo, Mundurukú and Sirionó, the Chapacuran languages Napeka and Toró, the Bororoan language Umotína and the isolates Kanoê and Trumai. Among the above-mentioned Tupian languages, only Sirionó belongs to the Tupí-Guaraní branch, whereas the other languages represent different branches of the Tupí linguistic stock. The similarity between negation patterns (although not the actual negation forms) between the Macro-Je and the above-mentioned Tupian languages deserves a further exploration in the light of various instances of grammatical congruence between these families (see e.g. Rodrigues 2009). The same remark pertains to the relationship between the Macro-Je and Bororoan (see Camargos 2013).

Third, preverbal syntactic single negation (Figure 8) shows the highest density in the northern part of Bolivia. One can also observe a relatively high occurrence of the pattern in the area stretching up northward along the eastern part of Brazil and the western part of Peru. Languages accounting for this areal pattern are genealogically diverse; many of these represent small families. For example, the area of the highest concentration of the pattern involves languages of the Southern Maipuran branch of Arawakan, Tacana (Tacanan), Eastern Bolivian Guaraní (Tupian), Wari’ and Itene (Chapacuran), Uru and Chipaya, Mosetén-Chimané, Puquina, Yurakaré, Movima, and Canichana.

Finally, preverbal morphological negation (Figure 9) is concentrated primarily in the northern part of Paraguay, the northeast of Argentina and the southeast of Bolivia. This corresponds approximately to the Grand Chaco geographical region. Languages with preverbal morphological negation found in this area are mainly languages of the Guaicuruan, Matacoan and Lengua-Mascoy language families, and the isolates Cayubaba and, to some extent, Itonama[16] spoken in Bolivia. It should be noted, however, that the number of data points for preverbal morphological negation is small. Nevertheless, this concentration is interesting. The Chaco area is known to form a cultural area, although its status as a linguistic area is less strong (Campbell and Grondona 2012: 626, 657). Campbell and Grondona (2012: 657) mention that very few structural characteristics are common to the majority of Chaco languages, and none of them is unique to the area. Preverbal negation is not mentioned, however.[17] While we remain neutral to the overall question of Chaco as a linguistic area, it does look as if preverbal morphological marking of standard negation is characteristic of most languages spoken in this area.

To conclude, our maps show each of the four negation patterns with an area of concentration. While the kernel density maps for preverbal morphological and postverbal syntactic patterns suffer from a low number of data points, postverbal morphological and preverbal syntactic patterns are much more common in South America, and therefore the kernel maps give a more accurate representation of the density of these negation strategies. Recall that Dryer (2013a) observed the largest concentration of languages with postverbal morphological negators in the northern half of South America (as compared to the rest of the world). While we can confirm it, our results show that the concentration of postverbal morphological negation is, in fact, geographically more specific: the languages with this pattern are concentrated in the northwest of the continent, with the highest density around the boundaries between Colombia, Peru and Brazil.

6 Explanations?

As discussed in Krasnoukhova et al. (2021: 501), there are generally two ways in which languages can come to use postverbal morphological negation. One encompasses purely language-internal processes. The other one involves a contact-driven change, which would typically comprise language-internal processes, too. In the case of South America, where the occurrence of postverbal morphological negation is found in 58% of the language families, we suggest that both language-internal and language contact accounts are relevant.

For some individual South American languages there do exist explanations (or well-argued hypotheses) as to how their postverbal negation pattern has emerged. For most languages there aren’t any. However, we can assume that some of the existing explanations do apply to some of the other languages too. Importantly, the diversity of the existing explanations shows that the dominant postverbal (morphological) pattern has not come about in just one particular way. As of now, we can only address diachronic mechanisms and sketch a few processes relevant for South American languages.

One of the relevant diachronic processes is known as the ‘Jespersen Cycle’ (the term is due to Dahl 1979: 88). It comes in different versions, but in the typical case a language starts with a single preverbal negator, develops this into an ‘embracing’ double negator, and retains only the postverbal negator (Dahl 1979; Jespersen 1917; van der Auwera 2009; van der Auwera and Krasnoukhova 2020a). This mechanism is best described for European languages, with French being a textbook example. A sentence in modern written French, such as Il ne peut pas venir ce soir ‘He can’t come tonight’, illustrates the element pas, which functions as a negator synchronically, but originates in a lexical item pas ‘step’, initially used after the verb for emphasis (Payne 1985: 224 referring to Price 1962, 1971: 252; van der Auwera 2009). This process is documented all over the globe, also in South America (Vossen 2016: 255–337). For instance, the Arawakan languages are predominantly preverbal (Michael 2014), but some Arawakan languages spoken in the Northern part of South America have double negation (with one negator preceding and another negator following the verb) and a few have a postverbal single pattern, some of which can be plausibly accounted for by a Jespersen Cycle (van der Auwera and Vossen 2016: 210–211). The relevance of a Jespersen Cycle has been also addressed for other South American languages, for example, the Tacanan language Tacana (Guillaume forthcoming) and the Barbacoan language Awa Pit (Krasnoukhova and van der Auwera 2019), among others. Of course, interpreting single postverbal negation as the result of a Jespersen Cycle is often hazardous in the absence of sufficient diachronic materials and comparative synchronic evidence.[18]

Another line of thought starts from the observation that South American languages are predominantly verb-final at the clause level, typically with SOV order for transitive clauses and SV for intransitives (see also Birchall 2014; Dryer 2013c). When these clause-final (or, at least, ‘clause-late’) verbs have negative meanings, they could be the source of the clause-final or postverbal negator.[19] But we have to be careful: Dryer (1988: 96, 2013d) has shown that SOV languages would have either a negator directly following the verb or directly preceding the verb equally often.

Thus some languages of the Je family show evidence for a development of postverbal negators from clause-final lexical verbs with terminative semantics, such as ‘finish’/‘end’, ‘stop’. We refer the reader to van der Auwera and Krasnoukhova (2022) for an extensive discussion of the suggested path and the Je languages involved. Example (14) illustrates Canela-Krahô, where the negator nare (from *inõare, A. Nikulin, p.c.) derives from the grammaticalized form of the lexical verb ‘finish’/‘end’ (Castro Alves 2010: 468–469). This lexical verb can still be found in the closely related language Kayapó (see also Silva 2015: 189–192), shown in (15). It is of interest to note that in Canela-Krahô, the negator nare has also a short form na (Castro Alves 2004: 129), which may suggest the process of grammaticalization taking place.

| Canela-Krahô (Northern Je, Macro-Je) (cane1242) | |||||||

| Me | h-ũmre | te | cukryt | cura-n | nare. | ||

| pl | 3-m | erg | tapir | kill.sg-nf | neg | ||

| ‘Men didn’t kill the tapir.’ | |||||||

| (Miranda 2015: 249, in van der Auwera and Krasnoukhova 2022: 22) | |||||||

| Kayapó (Northern Je, Macro-Je) (kaya1330) | |||||||

| Ga | arỳm | a-kõ-m | o | Ø-inõ-re. | |||

| 2.nom | already | 2-drink-nf | instr | 3-end-dim | |||

| ‘You have already finished drinking.’ | |||||||

| (Castro Alves 2010: 469, in van der Auwera and Krasnoukhova 2022: 22) | |||||||

A third line of thought takes us to the ‘Negative Existential Cycle’ (Croft 1991; Veselinova 2014; Veselinova and Hamari forthcoming), the process in which negative existential verbs, equivalents to the English ‘not exist’, can develop into standard negators. Relevant for us is that negative existential verbs which occur in the clause-final position can develop into clause-final standard negators. A good example are languages of the Pomoan, Yukian, and Wintuan families, spoken in the Northern California (see Mithun 2021). As Mithun (2021) demonstrates, in these families postverbal negators have their origin in clause-final negative existentials. Examples (16) and (17) sketch the situation in Pomoan. In Central Pomo, the form čʰów can function synchronically as a new (standard) negator, although its use is still restricted to realis clauses (Mithun 2021: 689). The source of this negator – a perfective verb meaning čʰó- ‘not exist, be absent’ – can still be found in the language (Mithun 2021: 689). In Eastern Pomo, the same negative verb (k h ú-y ‘not.exist-pfv’) has developed into a standard negator too, but the development has gone further: the new negator has been generalized to all types of negative constructions, and it has undergone reduction in form in dependent clauses, occurring now as a suffix (McLendon 1996: 533 in Mithun 2021: 691).

| Central Pomo (Pomoan) (cent2138) |

| Mú:t̯uya=ʔkʰe | ʔ=má: | čʰó-w. | ||

| 3pl=poss | cop=land | not.exist-pfv | ||

| ‘Their land does not exist’=‘They don’t have land.’ | ||||

| (Mithun 2021: 689) | ||||

| Ɂaː | miː | wá-ːɁw-an | čʰów |

| 1sg.agt | there | one.go-around-ipfv.sg | neg |

| ‘I didn’t go.’ | |||

| (Mithun 2021: 689) | |||

| Eastern Pomo (east2545) | |

| ‘They kept traveling like that, | |

| maːxár-heɁ-bà-ya | xól-p h iːliː- k h uy. |

| crying-spec-that-loc | towards-mult.come-neg |

| ‘never coming to where their mother was crying.’ | |

| (McLendon 1977: 42.77 in Mithun 2021: 691). | |

A development of a negative existential verb into a (standard) negator has been argued for a number of South American languages too, viz, some Chibchan languages, as well as some Je languages (see van der Auwera and Krasnoukhova 2020b, 2022).

A (clause-final) negative existential verb can become a (clause-final) standard negator not only via the Negative Existential Cycle. We argue that a negative existential verb can become a standard negator in constructions of verb serialization, verb incorporation and verb compounding. These processes are productive in different language families in South America. For example, in Mapudungun, verbal roots/stems incorporated into other verbs are abundant (Zúñiga 2017: 115), and noteworthy is the fact that derivational affixes “seem to have verbal etymons” (Zúñiga 2017: 115). Along these lines a serialization path has been proposed for standard negation in the Tucanoan languages (Krasnoukhova et al. 2022).

Of course, the question remains as to why specifically South America as a whole has a preference for postverbal morphological negation. Here (ancient) language contact could have played a role. The postverbal pattern is dominant in several large language families (Pano-Tacanan, Tucanoan, Macro-Je, Cariban, the Chibchan languages of the Magdalenic branch),[20] as well as in different small language families (viz. Nambiquaran, Arawan, Barbacoan, Chicham, Chocoan, Saliban, Naduhup, Yanomaman, Boran, and Huitotoan – see Appendix 2). We can hypothesize that the postverbal pattern (possibly involving a syntactic negator at that time) has developed in a family with major extensions, or a dominant language group, and that it subsequently spread through language contact by means of smaller spreads.[21] Here contact among genealogically related languages (see Epps et al. 2013 for a discussion) is likely to be as relevant as contact among unrelated languages. Different processes could have been at play at different times, including contact-induced grammaticalization (Heine and Kuteva 2003) and direct affix borrowing – see Seifart (2017: 397, 415), who also stresses the importance of sociolinguistic factors (Seifart 2015: 100; Thomason and Kaufman 1988).

Note that contact in earlier times seems most probable here. It emerges from a recent study by van Gijn et al. (2022) that data from linguistics and genetics in the sampled language groups in the Amazon region suggest a shared history (which may point to common ancestry or admixture) in the period before ca. 500 AD. Van Gijn et al.’s study focuses on the languages spoken in the Northwest Amazon region, which corresponds approximately to the area where the highest density of the postverbal morphological negation is identified (Figure 6).

If language contact is responsible for the dominance of postverbal (morphological) negation, it is likely that contact also played a role in maintaining this pattern. The postverbal negation strategy is functionally disfavored. One would thus expect that it is unstable, and that the ‘Neg Early’ pressure makes languages dispose of the pattern. However, it has been argued that some cognitively dispreferred patterns (e.g. ergativity, cf. Nichols 1993, 2003: 289; Bickel et al. 2015) have higher chances to ‘survive’ in situations of language contact (see Bickel 2015: 911–912; Nichols 2003: 295).

7 Conclusions

We can draw the following conclusions with respect to the way South American languages encode negation as compared to the rest of the world.

First, South American languages have a clear preference for the postverbal negation pattern, which goes against the global cross-linguistic preference for the preverbal pattern. Second, it was also shown that there is an overrepresentation of morphological negation, but this only concerns negators in the postverbal position. Third, we can state that South American languages prefer postverbal morphological negation to any other strategy. The dominance of postverbal morphological negation sets the South American continent apart from the rest of the world, since this strategy is among the least common ones elsewhere. Fourth, with respect to areal distribution of negation strategies within South America, we can conclude that the four main patterns of negation (i.e., postverbal morphological, postverbal syntactic, preverbal morphological and preverbal syntactic) each has their own area of concentration. The areal concentration of the dominant strategy, i.e., postverbal morphological negation, is found in the northwest of the continent, with the highest concentration around the boundaries between Colombia, Peru and Brazil. The fact that the postverbal morphological negation occurs in 58% of language families in South America calls for a consideration of language-internal developments as well as processes rooted in language contact.

Abbreviations

- 1

-

1st person;

- 2

-

2nd person;

- 3

-

3rd person;

- acc

-

accusative;

- agt

-

grammatical agent;

- an

-

animate;

- aux

-

auxiliary;

- caus

-

causative;

- clf

-

classifier;

- coll

-

collective;

- cop

-

copula;

- decl

-

declarative;

- dem

-

demonstrative;

- dim

-

diminutive;

- dk

-

direct knowledge;

- ds

-

different subject;

- erg

-

ergative;

- f

-

feminine;

- fm

-

final marker;

- fut

-

future;

- gen

-

general;

- ind

-

indicative;

- instr

-

instrumental;

- intns

-

intensifier;

- ipfv

-

imperfective;

- irr

-

irrealis;

- loc

-

locative;

- m

-

masculine;

- mult

-

multiple;

- nassrt

-

non-assertive;

- neg

-

negative;

- nf

-

non-finite;

- neut

-

neutral aspect;

- nmlz

-

nominalization/nominalizer;

- nom

-

nominative;

- ntheme

-

non-theme;

- nvis

-

non-visual;

- obl

-

oblique;

- pfv

-

perfective;

- pl

-

plural;

- poss

-

possessive;

- prs

-

present;

- pst

-

past;

- rec

-

recent;

- rel

-

relativiser;

- s

-

subject of intransitive or stative verb;

- sg

-

singular;

- spec

-

specific;

- sub

-

subordinator;

- theme

-

theme;

- top

-

topic marker;

- vpl

-

verbal plural

Funding source: Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek

Award Identifier / Grant number: G024117N

Funding source: Horizon 2020 Framework Programme

Award Identifier / Grant number: ERC SAPPHIRE grant 818854, Marie Skł odowska-Curie grant agreement No 895548

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the editors for all constructive and very helpful comments on the earlier versions of the manuscript. We would also like to express our thanks to Angela Terrill for proofreading the paper and taking care of the editorial matters. Many thanks are due to language specialists who provided us with additional information or data on languages used for our analysis: Adam Tallman (Chácobo), Alain Fabre (Nivaclé), Andrey Nikulin (Je languages), Anne Schwarz (Ecuadorian Secoya), Frank Seifart (Boran), Jens Van Gysel (Enlhet-Enenlhet), Joshua Birchall (Chapacuran), Kees Hengeveld (Cofán), Leo Wetzels (Nambiquaran), Martine Bruil (Ecuadorian Siona), Maxwell Miranda (Canela-Krahô), Mily Crevels (Itonama) and Rodrigo Gonzalo Becerra Parra (Kawésqar).

-

Funding: Olga Krasnoukhova would like to acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 895548. Johan van der Auwera would like to thank the Research Foundation-Flanders for its financial support of the project on the typology of negation in South American languages. Sietze Norder would like to acknowledge financial support by the European Research Council under the EU H2020 and Research and Innovation Program (SAPPHIRE grant 818854).

-

Contribution statement: OK and JvA initiated this study and collected and analyzed the data for South America. SN merged the South American data with the world’s data from Dryer (2013), conducted the spatial analyses and visualizations of negation patterns. All authors contributed to writing.

References

Adelaar, Willem. 2012. Historical overview. Descriptive and comparative research on South American Indian languages. In Lyle Campbell & Verónica Grondona (eds.), The indigenous languages of South America: A comprehensive guide, 1–57. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110258035.1Search in Google Scholar

Aguilera, F. Oscar, E. & José, S. Tonko, P. 2006. Manual para la Enseñanza de la Lengua Kawésqar. Nivel Básico 1b. Punta Arenas: Fundación para el Desarrollo XII° Región de Magallanes [FIDE XII]/Conadi.Search in Google Scholar

Bacelar, Laércio Nora. 2004. Gramática da língua Kanoê. Nijmegen: Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen Doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Baddeley, Adrian, Ege Rubak & Rolf Turner. 2015. Spatial point patterns: Methodology and applications with R. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press.10.1201/b19708Search in Google Scholar

Bernander, Rasmus, Maud Devos & Hannah Gibson. submitted. Bantu negative verbs: A typological-comparative investigation of form, function and distribution. In Zhen Li, Allen Asiimwe, Elisabeth Kerr, Ernest Nshemezimana & Jenneke van der Wal (eds.), Linguistique et Langues Africaines (Special issue on Bantu Universals and Variation).Search in Google Scholar

Bickel, Balthasar. 2015. Distributional typology: Statistical inquiries into the dynamics of linguistic diversity. In Bernd Heine & Heiko Narrog (eds.), Oxford handbook of linguistic analysis, 2nd edn., 901–923. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bickel, Balthasar, Alena Witzlack-Makarevich, Kamal K. Choudhary, Matthias Schlesewsky & Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky. 2015. The neurophysiology of language processing shapes the evolution of grammar: Evidence from case marking. PLoS One 10(8). e0132819. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132819.Search in Google Scholar

Birchall, Joshua. 2014. Argument marking (Features ARGEX1-1, ARGEX1-2). In Pieter Muysken, Harald Hammarström, Olga Krasnoukhova, Neele Müller, Joshua Birchall, Simon van de Kerke, Loretta O’Connor, Swintha Danielsen, Rik van Gijn & George Saad (eds.), South American Indian language structures (SAILS) online. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. Available at: https://sails.clld.org.Search in Google Scholar

Bruil, Martine. 2014. Clause-typing and evidentiality in Ecuadorian Siona. Leiden: Rijksuniversiteit Leiden Doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Bruil, Martine. 2019. The rise of the nominalizations: The case of grammaticalization of clause types in Ecuadorian Siona. In Roberto Zariquiey, Masayoshi Shibatani & David W. Fleck (eds.), Nominalization in languages of the Americas, 391–417. [Typological Studies in Languages, 124.]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/tsl.124.10bruSearch in Google Scholar

Camargos, Lidiane Szerwinsk. 2013. Consolidando uma proposta de Família Linguística Boróro. Contribuição aos estudos histórico-comparativos do Tronco Macro-Jê. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília Doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Lyle. 2012. Classification of the indigenous languages of South America. In Lyle Campbell & Verónica Grondona (eds.), The indigenous languages of South America: A comprehensive guide, 59–166. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110258035.59Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Lyle. 2017. Language isolates and their history. In Lyle Campbell (ed.), Language isolates, 1–18. London & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315750026-1Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Lyle & Verónica Grondona. 2012. Languages of the Chaco and Southern Cone. In Lyle Campbell & Verónica Grondona (eds.), The indigenous languages of South America: A comprehensive guide, 625–667. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110258035.625Search in Google Scholar

Castro Alves, Flavia de. 2004. O Timbira falaso pelos Canele Apãniekrá: uma contribuição aos estudoes da morfossintaxe de uma língua Jê. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas Doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Castro Alves, Flávia de. 2010. Evolution of alignment in Timbira. International Journal of American Linguistics 76(4). 439–475. https://doi.org/10.1086/658054.Search in Google Scholar

Chapman, Shirley & Desmond C. Derbyshire. 1991. Paumarí. In Desmond C. Derbyshire & Geoffrey K. Pullum (eds.), Handbook of Amazonian languages, 161–354. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Crevels, Mily. 2012a. Language endangerment in South America: The clock is ticking. In Lyle Campbell & Verónica Grondona (eds.), The indigenous languages of South America: A comprehensive guide, 167–233. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110258035.167Search in Google Scholar

Crevels, Mily. 2012b. Itonama. In Mily Crevels & Pieter Muysken (eds.), Ambito Andino, 233–294. La Paz: Plural Editores.Search in Google Scholar

Croft, William. 1991. The evolution of negation. Journal of Linguistics 27. 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226700012391.Search in Google Scholar

Dahl, Östen. 1979. Typology of sentence negation. Linguistics 17. 79–106. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1979.17.1-2.79.Search in Google Scholar

Dahl, Östen. 2010. Typology of negation. In Laurence R. Horn (ed.), The expression of negation, 9–38. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110219302.9Search in Google Scholar

Dahl, Östen. 2014. Sirionó. In Pieter Muysken & Mily Crevels (eds.), Oriente, 99–133. La Paz: Plural Editores.Search in Google Scholar

Dienst, Stefan. 2014. A grammar of Kulina. (Mouton Grammar Library, 66). Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110341911Search in Google Scholar

Doornenbal, Marius. 2009. A grammar of Bantawa: Grammar, paradigm tables, glossary and texts of a Rai language of Eastern Nepal. Leiden: Leiden University Doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew. 1988. Universals of negative position. In Michael Hammond, Edith Moravcsik & Jessica Wirth (eds.), Studies in syntactic typology, 93–124. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.17.10drySearch in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew. 2013a. Order of negative morpheme and verb. In Matthew Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), The world atlas of language structures online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available at: http://wals.info/chapter/143.Search in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew. 2013b. Negative morphemes. In Matthew Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), The world atlas of language structures online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available at: http://wals.info/chapter/112.Search in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew. 2013c. Order of subject, object and verb. In Matthew Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), The world atlas of language structures online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available at: http://wals.info/chapter/81.Search in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew. 2013d. Position of negative morpheme with respect to subject, object, and verb. In Matthew Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), The world atlas of language structures online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available at: http://wals.info/chapter/144.Search in Google Scholar

Eberhard, David M. 2009. Mamaindē Grammar: A Northern Nambikwara language and its cultural context. Utrecht: LOT Doctoral dissertation, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.Search in Google Scholar

Epps, Patience, John Huehnergard & Na’ama Pat-El. 2013. Introduction: Contact among genetically related languages. Journal of Language Contact 6(2). 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1163/19552629-00602001.Search in Google Scholar

Fabre, Alain. 2016. Gramática de la lengua Nivacle (familia Mataguayo, Chaco Paraguayo). (LINCOM Studies in Native American Linguistics, 78.). München: Lincom.Search in Google Scholar

Givón, Talmy. 1973. The time-axis phenomenon. Language 49. 890–925. https://doi.org/10.2307/412067.Search in Google Scholar

Givón, Talmy. 1978. Negation in language: Pragmatics, function, ontology. In Peter Cole (ed.), Syntax and semantics, vol. 9 (Pragmatics), 69–112. New York: Academic Press.10.1163/9789004368873_005Search in Google Scholar

Givón, Talmy. 2001. Syntax: An introduction, vol. I. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.syn2Search in Google Scholar

Goebel, Ted, Michael R. Waters & Dennis H. O’Rourke. 2008. The late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans in the Americas. Science 319(5869). 1497–1502. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1153569.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Amy, Alexis Mychajliw & Elisabeth Hadly. 2016. Post-invasion demography of prehistoric humans in South America. Nature 532. 232–235. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17176.Search in Google Scholar

Gómez-Carballa, Alberto, Jacobo Pardo-Seco, Stefania Brandini, Alessandro Achilli, Ugo A. Perego, Michael D. Coble, Toni M. Diegoli, Vanesa Álvarez-Iglesias, Federico Martinón-Torres, Anna Olivieri, Antonio Torroni & Antonio Salas. 2018. The peopling of South America and the trans-Andean gene flow of the first settlers. Genome Research 28. 767–779. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.234674.118.Search in Google Scholar

Guillaume, Antoine. forthcoming. Negation in Tacana (Amazonian Bolivia): Synchronic description and diachronic reconstruction. In Ljuba Veselinova & Arja Hamari (eds.), The negative existential cycle. (Research on Comparative Grammar 1). Berlin: Language Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hammarström, Harald, Robert Forkel, Martin Haspelmath & Sebastian Bank. 2021. Glottolog 4.5. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available at: http://glottolog.org.Search in Google Scholar

Haude, Katharina. 2006. A grammar of Movima. Doctoral dissertation, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. Zetten: Manta.Search in Google Scholar

Haude, Katharina. 2018. Nonverbal predication in Movima. In Simon E. Overall, Rosa Vallejos & Spike Gildea (eds.), Nonverbal predication in Amazonian languages, 217–244. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/tsl.122.08hauSearch in Google Scholar

Heine, Bernd & Tania Kuteva. 2003. On contact-induced grammaticalization. Studies in Language 27(3). 529–572. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.27.3.04hei.Search in Google Scholar

Hengeveld, Kees. 1992. Non-verbal predication. (Functional grammar series, 15). Berlin/New York: Mouton De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110883282Search in Google Scholar

Horn, Laurence R. 1989. A natural history of negation, 2nd edn. 2001. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Jespersen, Otto. 1917. Negation in English and other languages. Negation in English and other languages. Kopenhagen: Høst.Search in Google Scholar

Krasnoukhova, Olga & Johan van der Auwera. 2019. Standard negation in Awa Pit: From synchrony to diachrony. Folia Linguistica Historica 40(2). 439–474. https://doi.org/10.1515/flih-2019-0017.Search in Google Scholar

Krasnoukhova, Olga, Johan van der Auwera & Mily Crevels. 2021. Postverbal negation: Typology, diachrony, areality. Studies in Language 45(3). 499–519. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.00020.int.Search in Google Scholar

Krasnoukhova, Olga, Martine Bruil & Johan van der Auwera. 2022. Negation in Tucanoan: A closer look at diachrony. Paper presented at The workshop on ‘Negation in clause combining’. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.Search in Google Scholar

Landin, David J. 1984. An outline of the syntactic structure of Karitiâna sentences. In Robert A. Dooley (ed.), Estudos sobre linguas tupi do Brasil, 219–254. Brasilia: Summer Institute of Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Lemus Serrano, Magdalena. 2020. Pervasive nominalization in Yukuna: An Arawak language of Peruvian Amazonia. Lyon: Doctoral dissertation Université Lumière Lyon 2.Search in Google Scholar

McLendon, Sally. 1977. Bear kills her own daughter-in-law, Deer (Eastern Pomo). In Victor Golla & Shirley Silver (eds.), Northern California texts, 26–70. International Journal of American Linguistics Text Series 2(2). Chicago: University of Chicago.Search in Google Scholar

McLendon, Sally. 1996. Sketch of Eastern Pomo, a Pomoan language. In Ives Goddard (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians 17: Languages, 507–550. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.Search in Google Scholar

Michael, Lev. 2014. A typological and comparative perspective on negation in Arawak languages. In Lev Michael & Tania Granadillo (eds.), Negation in Arawak languages, 235–291. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004257023Search in Google Scholar

Miestamo, Matti. 2005. Standard negation. The negation of declarative verbal main clauses in a typological perspective. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110197631Search in Google Scholar

Miestamo, Matti. 2010. Negatives without negators. In Jan Wohlgemuth & Michael Cysouw (eds.), Rethinking universals: How rarities affect linguistic theory, 169–194. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110220933.169Search in Google Scholar

Miestamo, Matti, Dik Bakker & Antti Arppe. 2016. Sampling for variety. Linguistic Typology 20(2). 233–296. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2016-0006.Search in Google Scholar

Miranda, Maxwell. 2015. Negação em Krahô (família Jê) em uma perspectiva comparativa. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Antropológica 7. 245–274.10.26512/rbla.v7i2.20599Search in Google Scholar

Mithun, Marianne. 2021. Stories behind post-verbal negation clustering. Studies in Language 45(3). 684–706. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.19040.mit.Search in Google Scholar

Moore, Denny. 2016. Negation in Gavião of Rondônia. Paper presented at Amazoncas VI, Leticia & Tabatinga May 23–28, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

Muysken, Pieter, Harald Hammarström, Joshua Birchall, Swintha Danielsen, Love Eriksen, Ana Vilacy Galucio, Rik van Gijn, Simon van de Kerke, Vishnupraya Kolipakam, Olga Krasnoukhova, Neele Müller & Loretta O’Connor. 2014. The languages of South America: Deep families, areal relationships, and language contact. In Loretta O’Connor & Pieter Muysken (eds.), The native languages of South America. Origins, development, typology, 299–322. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781107360105.017Search in Google Scholar

Nichols, Johanna. 1993. Ergativity and linguistic geography. Australian Journal of Linguistics 13. 39–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268609308599489.Search in Google Scholar

Nichols, Johanna. 2003. Diversity and stability in language. In Brian D. Joseph & Richard D. Janda (eds.), The handbook of historical linguistics, 283–310. Malden, MA & Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470756393.ch5Search in Google Scholar

Norder, Sietze, Laura Becker, Hedvig Skirgård, Leo Arias, Alena Witzlack-Makarevich & Rik van Gijn. 2022. glottospace: R package for language mapping and geospatial analysis of linguistic and cultural data. Journal of Open Source Software 7(77). 4303. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.04303.Search in Google Scholar

Pacheco, Quesada, Miguel Ángel. 2012. Esbozo gramatical de la lengua Muisca. Estudios de Lingüística Chibcha 31. 7–92.Search in Google Scholar

Patte, Marie-France. 2014. Negation in Guianese Lokono/Arawak. In Lev Michael & Tania Granadillo (eds.), Negation in Arawak languages, 54–73. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004257023_004Search in Google Scholar

Payne, John R. 1985. Negation. In Timothy Shopen (ed.), Language typology and syntactic description, vol. 1. Clause structure, 197–242. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Pebesma, Edzer. 2018. Simple features for R: Standardized support for spatial vector data. The R Journal 10(1). 439–446. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-009.Search in Google Scholar

Price, Glanville. 1962. The negative particles pas, mie, and point in French. Archivum Linguisticum 14. 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191620140201.Search in Google Scholar

Price, Glanville. 1971. The French language: Present and past. London: Edward Arnold (publishing).Search in Google Scholar

Priest, Anne & Perry N. Priest. 1980. Textos sirionó. Riberalta: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.Search in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.Search in Google Scholar

Rijkhoff, Jan, Dik Bakker, Kees Hengeveld & Peter Kahrel. 1993. A method of language sampling. Studies in Language 17. 169–203. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.17.1.07rij.Search in Google Scholar

Rodrigues, Aryon D. 2009. A case of affinity among Tupí, Karíb, and Macro-Jê. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Antropológica 1. 137–162.10.26512/rbla.v1i1.12289Search in Google Scholar

Rosenkvist, Henrik. 2021. Clause-final negative particles in varieties of Swedish: Distribution, grammatical properties, and possible etymologies. Studies in Language 45(3). 598–620. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.19037.ros.Search in Google Scholar

Rybka, Konrad & Lev Michael. 2019. A privative derivational source for standard negation in Lokono (Arawakan). Journal of Historical Linguistics 9(3). 340–377. https://doi.org/10.1075/jhl.18020.ryb.Search in Google Scholar

Seifart, Frank. 2015. Does structural-typological similarity affect borrowability? A quantitative study on affix borrowing. Language Dynamics and Change 5. 92–113. https://doi.org/10.1163/22105832-00501004.Search in Google Scholar

Seifart, Frank. 2017. Patterns of affix borrowing in a sample of 100 languages. Journal of Historical Linguistics 7(3). 389–431. https://doi.org/10.1075/jhl.16002.sei.Search in Google Scholar

Silva, Lucivaldo Costa da. 2015. Uma descrição gramatical da língua Xikrín do Cateté (família Jê, tronco Macro-Jê). Brasília: Universidade de Brasília Doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

South, Andy. 2017. rnaturalearth: World map data from natural earth. R package version 0.1.0. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=rnaturalearth.Search in Google Scholar

Storto, Luciana. 1999. Aspects of a Karitiana grammar. Cambridge, Mass.: Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Search in Google Scholar

Storto, Luciana. 2018. Negation in Karitiana. In Lisa Matthewson, Erin Guntly, Marianne Huijsmans & Michael Rochemont (eds.), Wa7 xweysás i nqwal’utteníha i ucwalmícwa: He loves the people’s language. Essays in honour of Henry Davis, 229–240. University of British Columbia Occasional Papers in Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Tennekes, Martijn. 2018. tmap: Thematic maps in R. Journal of Statistical Software 84(6). 1–39. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v084.i06.Search in Google Scholar

Thomason, Sarah G. & Terrence Kaufman. 1988. Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.10.1525/9780520912793Search in Google Scholar

Van Alsenoy, Lauren. 2014. A new typology of indefinite pronouns, with a focus on negative indefinites. Antwerp: University of Antwerp Doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

van der Auwera, Johan. 2009. The Jespersen cycles. In Elly van Gelderen (ed.), Cyclical change, 35–71. [Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today, 146]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.146.05auwSearch in Google Scholar

van der Auwera, Johan, Daniel Van Olmen & Frens Vossen. forthcoming a. Negation. In Alexander Adelaar & Antoinette Schapper (eds.), The Oxford guide to the Malayo-Polynesian languages of Asia and Madagascar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

van der Auwera, Johan & Frens Vossen. 2016. Jespersen cycles in Mayan, Quechuan and Maipurean languages. In Elly van Gelderen (ed.), Cyclical change continued, 189–218. [Linguistics Today, 227]. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.227.07auwSearch in Google Scholar

van der Auwera, Johan & Olga Krasnoukhova. 2020a. The typology of negation. In Viviane Déprez & Maria Teresa Espinal (eds.), The Oxford handbook of negation, 91–116. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198830528.013.3Search in Google Scholar

van der Auwera, Johan & Olga Krasnoukhova. 2020b. Standard negation in Chibchan. LIAMES: Línguas Indígenas Americanas 20. e020005. https://doi.org/10.20396/liames.v20i0.8658401.Search in Google Scholar