Abstract

Two modal verbs of German are regularly used to express deontic possibility: können (‘can’) and dürfen (‘may’). We examine how speakers select between them, focusing on modal inquiries for permission to carry out some action (darf/kann ich das machen, ‘may/can I do this’). Our data are video-recordings of everyday face-to-face interaction, which we analyze sequentially, drawing on interactional-linguistic methods. We find that local sequential context and aspects of visible turn-design systematically enter into the accomplishment of deontic meaning. (1) Position of the modal inquiry within a course of action informs verb selection: speakers select kann to nominate an action as coming “out of the blue” and initiating a new course of action; darf to nominate an action as sequentially occasioned: a solution to an already known-in-common problem. (2) Bodily behavior (gaze, body posture) guides the interpretation of modal flavor, moving a kann-inquiry towards a deontic or a circumstantial interpretation, and moving a darf-inquiry towards a deontic or a bouletic interpretation. Overall, the study demonstrates the systematic contributions of sequential position and body behavior in the accomplishment of modal meanings.

1 Introduction

This paper examines deontic meaning accomplished with two modal verbs of German, können (‘can’) and dürfen (‘may’). In everyday talk, both of these verbs are regularly used to ask about the permissibility of some action. That is, both are used to express deontic meaning, sometimes in very similar situations. In (1) and (2), board game players ask about the permissibility of a game move; Moritz uses kann in Extract 1, Marvin uses darf in Extract 2.

Extract 2

‘may one do that’ PECII_DE_Game_20210602_1448889

In Extracts 3 and 4, one and the same person, Carola, uses first kann, and a moment later, darf, to inquire about doing a “U-turn” with a car.

Extract 3

‘can I U-turn right here then’ PECII_DE_Car_20171031_1_366206 (6 mins 26 secs) (simplified)

Extract 4

‘may I U-turn here now’ PECII_DE_Car_20171031_1_417620 (6 mins 57 secs) (simplified)

We will analyze these data in more detail later. For now, just note the following:

Both the turns with kann and the ones with darf are taken by participants to concern possibility in a deontic mode – next speakers confirm the permissibility of the relevant action (1 and 2) or point out that there are rules prohibiting it (3 and 4);

These interaction data suggest that können and dürfen can be used in very similar ways to talk about deontic possibility.

It is well known that können and dürfen can both express deontic meaning. However, the systematic differences between the two verbs when used to accomplish deontic meaning are not well understood. We will argue that we can better understand how speakers select between different modal verbs by considering where the modal utterance is placed in a course of action in conversation, in short its sequential context. Interactional-linguistic research has found that language structures at different levels of organization are adapted to and rely for their core meaning on very specific contextual “home environments”. For example, it has been shown that choices in sentence mood are informed by the connection of a speech action to the wider course of activity within which they occur (in relation to requests: Raymond et al. 2021; Rossi 2012; Zinken and Ogiermann 2013; in relation to offers: Curl 2006). Here, we extend this approach to the study of lexical items. But first, we turn to some background on deontic modality and modal verbs.

Deontic modality is traditionally understood as relating to obligation or permission stemming from some authority, which can be another person or an impersonal body of rules and norms (e.g., Palmer 2001: 10). It has often, and sometimes critically (Nuyts et al. 2010), been noted that “obligation” and “permission” refer to social relations and social actions. Hence, we can initially characterize the meanings of utterances such as the first turns in the extracts above as “asking for permission”. However, on closer inspection, the associations between deontically used modal verbs and speech acts such as asking or giving permission are not straightforward. First, of course, it is well known that modal verbs such as können or dürfen can express various modal “flavors” (see discussion below). Second, modal expressions are not necessary to ask for permission (“Do you mind if I …”). And finally, when speakers do (ostensively) inquire about the acceptability of their actions using a modal verb, these moves are sometimes not well glossed as “requesting permission”: often, people already start doing the focal action (say, make a game move) as they ask, which casts doubt on the notion that the action achieved with such modal inquiries is always well glossed as requesting permission (Deppermann and Gubina 2021b). In sum, there is no necessary link between modal verbs and either expressing deontic meaning or accomplishing actions of seeking permission. The question therefore arises: what exactly do the verbs können and dürfen contribute to social actions that pave the way to some behavior? Before we tackle this question, we introduce some background on modality in general and the modal verbs können and dürfen in particular.

2 Modality and modal verbs

The term modality as it is used in linguistics captures the intuition that some utterances – those including modal expressions, for example, modal verbs – do not speak about what is plainly the case, but present an event or state of affairs in a certain way, in some “mode”. How many such modes exist and how they are related to one another is a matter of ongoing debate. Here, we only introduce some distinctions concerning non-epistemic modality that should be rather uncontroversial in order to lay the necessary conceptual ground for this study.

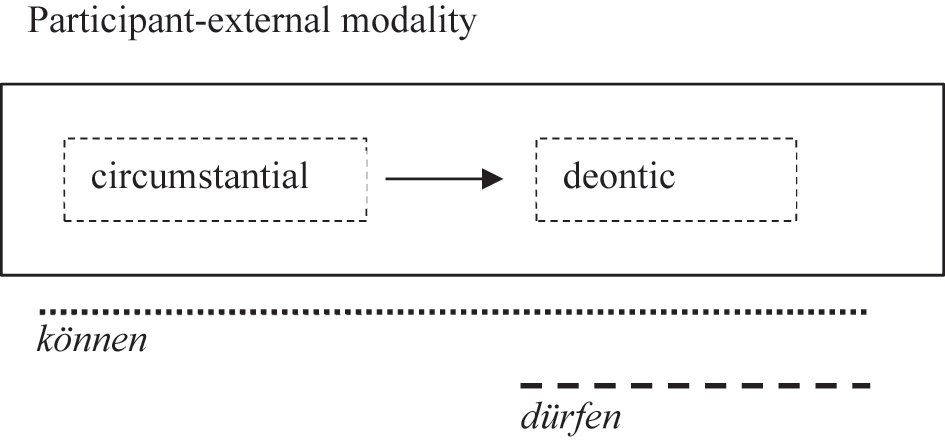

Deontic modality is often subsumed under broader categories that capture possibilities and necessities existing due to factors inherent to the situation, categories such as root (e.g., Coates 1983), agent-oriented (Bybee et al. 1994), or participant-external modality (van der Auwera and Plungian 1998). Permission by an authority is then one kind of situational factor making an action possible, alongside other, non-deontic circumstances. We will speak of circumstantial modality where some action is possible because local material circumstances provide for it, as in wir können die Treppe nehmen (‘we can take the staircase’ = this is possible because there is one). We will treat circumstantial and deontic modality as two forms of participant-external modality (Figure 1).

Snippet of modality’s semantic map, adapted from van der Auwera and Plungian (1998). The arrow indicates that across languages, structures expressing circumstantial modality tend to develop a deontic use (Bybee et al. 1994).

Linguists studying German have – like linguists more broadly – dedicated relatively little attention specifically to deontic modality (Nuyts et al. 2010). The modal verbs können and dürfen are typically discussed in the context of overarching examinations of the entire range of modal meanings. In that context, können is sometimes treated as part of the core of the German modal auxiliary system, together with müssen (‘must’). These two verbs are the only ones that can express all the different modal “flavors” that linguists distinguish (Zifonun et al. 1997: 1888). In line with this functional versatility, können is one of the most frequently attested modal auxiliaries in corpus studies (Brünner and Redder 1983: 255ff.; Kaiser 2017: 98). The basic meaning for können is considered to be ‘possibility’ understood widely in the sense of a “root” modality, encompassing abilities as well as external circumstances (Hentschel and Weydt 2013; Zifonun et al. 1997). Können is, not surprisingly, a prime member of what Narrog (2016: 98) calls the cross-linguistically common CAN-cluster: a structure that expresses circumstantial possibilities (as well as internal abilities) and extends to deontic modality (see Figure 1).

The verb dürfen is functionally much more restricted, and is sometimes described as a marked counterpart to können (Öhlschläger 1989: 158). Although we use the English may as a gloss for dürfen throughout this paper, it should be kept in mind that dürfen seems to have no direct equivalent in the other Germanic languages, German mögen being in some ways nearer to the English may (Mortelmans et al. 2009). In indicative use, dürfen is largely restricted to the deontic meaning of permission or permissibility (see Figure 1), although some other, less commonly discussed non-epistemic uses are possible, such as a “bouletic” interpretation (relating to “wishes”) in Morgen darf es nicht regnen, ich will wandern gehen (‘it mustn’t rain tomorrow, I want to go hiking’). Accordingly, its overall frequency in corpora is much lower (again, see Brünner and Redder 1983: 255ff.; Kaiser 2017: 98). Some grammars point out that dürfen, in contrast to können, seems to require a “third authority” (Brünner and Redder 1983: 54; Hentschel and Weydt 2013: 80), or a “normative ideal” (Zifonun et al. 1997: 1891) that grants permission. Also, it has been suggested that dürfen presupposes or is responsive to somebody’s “wish” to perform the relevant action (Diewald 1999: 128; Zifonun et al. 1997: 1892).

These global characterizations of können and dürfen, however, provide little insight into how speakers would select between können and dürfen when addressing permissibility, that is, expressing a deontic meaning. They might suggest that dürfen would be the “proper” choice, given its functional specialization for deontic uses. This intuition seems to be behind that staple of teachers’ jokes, where the pupil asks, can I go to the toilet, and the teacher responds, I don’t know if you can – but you may, thus putting the pupil on the spot for having asked the “wrong” way. We may also wonder whether dürfen more “strongly” orients to a third party authority than können, in analogy with some work on modal strength hierarchies between lexical alternatives for expressing other modal flavors (e.g., you must do your homework > you should do your homework) (Kroeger 2018: 290; Narrog 2016: 100). Öhlschläger (1989: 158ff.) most directly addresses the difference between dürfen and können in “participant-external” modalities. In his analysis (of constructed sentences), the difference is that non-epistemic dürfen, but not können, encodes the prospect of sanctions.

Our study offers a sequential analysis of how speakers select between können and dürfen for accomplishing deontic meanings in the situational context of face-to-face interaction. The results will demonstrate that this context is crucial. To be sure, context has already played an important role in semantic theories of modality. Consider the “relational” theory of modality (Kratzer 1977, 1991), the standard theory of modality in formal linguistics (e.g., Kroeger 2018: 289ff. for an introduction). In a nutshell, this theory proposes that modal verbs such as can or must are semantically vague regarding the type of modality they express. The must in she must have arrived home by now (epistemic modality) is the same as the must in you must go now (deontic modality). It is the conversational background, not the lexical semantics, that determines which type of modality is expressed. A normative conversational background of rules, duties, or obligations leads to a deontic interpretation of semantically vague modal verbs (Zifonun et al. 1997: 1882). Conversational backgrounds are – the name gives it away – a conversational phenomenon. The centrality of “conversation”, or the social and situational context of talk, for the accomplishment and understanding of modal meanings has also been emphasized by functionally minded linguists (Bybee and Fleischman 1995). However, how details of context actually enter into the constitution of modal meanings has received little attention. Recent interactional work has studied the range of functions of particular modal verb constructions in social interaction (Deppermann and Gubina 2021a; Gubina 2022; Kaiser 2017).[2] Here, we zoom in on the category of deontic modality and ask: what are the contextual bases for and the interactional consequences of selecting among alternatives for accomplishing deontic meaning with modal verbs?

3 Methods and data

The data we examine come from the German part of a multi-language parallel video corpus, PECII (Parallel European Corpus of Informal Interaction), which contains about 100 h of recordings of everyday interactions among family and friends during board games, family mealtimes, and car rides (Küttner et al. in press). This corpus will become available to researchers as part of the corpus infrastructure of the Archive of Spoken German at the Leibniz-Institute for the German Language (https://agd.ids-mannheim.de/index_en.shtml).

In these data, and within the context of a larger project, we have been interested in methods that persons in everyday life use to make sure that things they want to do will be acceptable to others. One such method is to make a modal inquiry addressing the permissibility of some future or incipient action. We noticed that both können and dürfen are used in such modal inquiries, and that they seemed somewhat interchangeable, at least prima facie (see Extracts 1–4). Because of our interest in acceptability and deontic meaning, we have excluded data that formally contain modal inquiries, but that do not primarily concern permissibility. Thus, we have excluded object requests made with modal inquiries (‘can I have the salt?’ to be passed the salt [Zinken 2015]), as well as modal inquiries that mobilize a helpful bodily adjustment from the other person (‘may I?’ to get another person to move out of the way [see Deppermann and Gubina 2021b]). These modal inquiries mobilize different forms of assistance or cooperation, and do not primarily address the permissibility of the speaker’s action.

Our data include syntactically interrogative modal inquiries in the first person singular (kann ich, ‘can I’) and in the third person “impersonal” format (kann man, ‘can one’/‘is it possible’), as well as syntactically declarative modal utterances turned into an inquiry with a question tag (man kann … oder?, ‘one can/it is possible … right?’). There may well be diversity between these formats (e.g., the impersonal format might make an external source such as game rules recognizable as the relevant authority). However, such differences turn out to be orthogonal to the findings of our analysis.

In sum, our starting point was neither a particular linguistic form or construction alone, nor a particular type of action, but rather the use of a family of turn-constructional resources (können or dürfen in modal inquiries) in a specific social moment (speaker wants to do action X but also wants to ascertain its acceptability). We refer to these kinds of modal inquiries summarily as kann-inquires and darf-inquiries. Using the interactional-linguistic method of sequential analysis (e.g., Couper-Kuhlen and Selting 2018; Schegloff 2007), we examined modal inquiries in detail on a case-by-case data, cumulatively developing analytic generalizations. We also sought (and found) deviant cases offering a test to our findings (Silverman 2020). Data were annotated using ELAN (2020), transcripts follow conversation-analytic conventions (Jefferson 2004). Target lines receive a simplified (without marking of morpheme boundaries) interlinear morpheme gloss (Bickel et al. 2008). Where relevant, annotations have been added to the transcripts to describe participants’ visible behavior (Mondada 2018, see also https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription).

4 The home environments of darf-inquiries and kann-inquiries

We first present our generalizations concerning the differences between kann and darf in deontic modal inquiries, and then discuss deviant cases. We begin with the home environment of darf-inquiries. Our first example comes from an interaction between three friends on a car trip. Lara, the driver, and Roland in the passenger seat have been talking about their different temperature preferences when driving. The echt-sequence in lines 1–4 is where that line of talk peters out. Roland begins bending down towards his bag, and he takes a next turn: vielleicht muss ich was (0.4) es- (‘maybe I need something to ea-’ [line 32]). However, shortly before arriving at a possible completion point, Roland breaks off and quickly moves into a darf-inquiry: darf man in deinem auto essen oder gibt’s da so ne (‘may one/is it allowed to eat in your car or is there such a …’ [lines 33–34]). This turn is designedly left open (Chevalier and Clift 2008), lacking a noun phrase. The feminine indefinite article ne, as well as the impersonal format of the inquiry (darf man, ‘may one’) suggest that the noun that was coming might be Regel (‘rule’). In its place, Roland turns his gaze to Lara. Lara emphatically affirms that it is acceptable to eat in her car, and Roland proceeds to take chocolate crisps from his bag.

Extract 5

‘may one/is it allowed to eat in your car’ PECII_DE_Car_20180907_1095567

The crucial observation for us here is that Roland’s permission inquiry has an interactional pre-history. In fact, even within his turn-at-talk, it emerges out of something prior: his out-loud saying that ‘maybe I need to ea-’ (vielleicht muss ich was (0.4) ess- [line 5]). This ostensive self-talk is hearable as connecting back to prior matters. Indeed, Roland’s move to eat something, and his darf-inquiry, emerge out of a problem that has been the subject of talk between Lara and Roland in the minute or so leading up to Extract 5. Extract 6 shows some of this interaction. The relevant pre-history of Roland’s darf-inquiry begins when Lara notices that Roland seems to have fallen asleep. As it turns out, Roland isn’t sleeping. Responding to Lara, he connects his sleepiness with the fact that it is “mega cold” in the car (line 6). He thus articulates a problem he experiences. He moves to turn up the heating, but notices that Lara has actually turned it further down. This leads to their interchange about temperature preferences. Roland now explicitly names the problem that “when it’s cold I fall asleep” (line 20).

Extract 6

‘may one eat in your car’ PECII_DE_Car_20180907_1073360

The situation so far then is that Roland has reported a problem – he feels cold, and this makes him sleepy – and he has attempted a solution, turning up the heating, which, however, has been frustrated because Lara’s preferences run in the opposite direction. In this context, his bending down towards his bag, accompanied by his comment that vielleicht muss ich was ess- (‘maybe I need something to ea-’) is recognizable as articulating another potential solution to his problem. When Roland breaks off this emerging utterance and instead launches his darf-inquiry, he orients to the relevance of getting the driver’s (and car owner’s) permission (Rossi and Stivers 2021). At the same time, his inquiry nominates the relevant action as a solution to a problem (a need or wish) that has already been made public. Notwithstanding all the unique quirks of this particular fragment of interaction, this observation holds for darf-inquiries across our collection: darf-inquiries nominate an action as sequentially occasioned by what was made public before, specifically: as a solution to a known problem.

Here is another example, a fragment of interaction that is very different from the first one in many ways, but with a darf-inquiry that, once again, nominates an action as a solution to a problem that is out in the open. Four friends are playing the board game Catan. They are in an early phase of the game, where each player in turn can place a game piece, obeying certain rules of placement. After Anabell chooses a spot on the board for her game piece (line 1), it is Marvin’s turn. Marvin gazes at the board, his game piece in hand (line 2, Figure 2). At line 3, Jaron addresses a piece of information about the game to Marvin, and while the other two players both respond to this information, Marvin does not (lines 3–9). Instead, he keeps screening the game board. He then raises the hand that holds his game piece above the board, further considering it for another full 20 s (line 10, Figure 3). Finally, he moves his hand to a spot where he might place his figure. Hovering just above the chosen spot, he then produces a darf-inquiry, addressing it to Lena by gaze.

Marvin (right, back) gazes at the board (2), considers possible spots (3), and inquires about a candidate spot (4).

Extract 7

‘may one do this’ PECII_DE_Game_20210602_1448889

Although there is no talk here about Marvin’s task of finding a spot for his game piece, the fact that he is having difficulties finding one becomes public in several ways: (1) The known-in-common turn structure of the game, with Marvin’s turn beginning after Anabell has made her choice (on pre-allocation of turns in games, see Hofstetter [2021]); (2) the fact that Marvin “ignores” Jaron’s information addressed to him (lines 3–4), keeping his focus on the game board; and (3) the lengthy period of consideration by Marvin, made visible by his hand hovering above the board, all display the non-straightforward nature of Marvin’s task to his co-players. When it comes, then, Marvin’s darf-inquiry is hearable as nominating an action (“doing that”, i.e., placing the figure on the chosen spot) as a possible solution to a publicly accessible problem, while also soliciting the others’ approval of this action as a legitimate move in the game.

Let us now compare this to the sequential home environment of kann-inquiries. Our first case here comes from another group of friends playing Catan. It is Katharina’s turn, and she announces that she will build two roads (lines 1–3). As she is making her game move, Moritz asks about a game rule: kann man jederzeit (.) äh bauen eigentlich (‘can one, er, build at any time actually’ [line 5]). Gerald first answers in the affirmative (line 7). However, as Moritz then moves to actually build something, it turns out that there was a misunderstanding, and his move is forestalled.

Extract 8

‘can one build at any time’ PECII_DE_Game_20151113_1603916

Note first that Moritz’s kann-inquiry addresses a deontic possibility: just like Marvin in the previous case, he asks whether a particular game move is licensed by the rules of the game. What is different about this case is that the notion of Moritz building something has not been “prepared” by the current context. It is not Moritz’s turn at play, he is not even the next in line, and Moritz did nothing to make public his wish to build something. Moritz himself builds this out-of-the-blueness into the design of his turn: he begins with an audible in-breath, thus orienting to a context in which a turn by him may not be expectable (on audible inhalation in the context of turn-taking, see Robinson [2023]). At a point of possible completion (kann man jederzeit bauen, ‘can one build at any time’), he incrementally extends his utterance with eigentlich, a modal particle that indicates that the question does not emerge out of the current interactional context (König 1977: 123) but introduces a new matter (Thurmair 1989: 176) (for an interactional treatment, see Clift [2001], on English ‘actually’). Moritz’s kann-inquiry then nominates the action of him “building” something not as a solution to a publicized problem, but as a new matter. However, it seems that Moritz’s inquiry is sequentially so disjunct from what happened before that his fellow players, or Gerald at least, mistakenly try to make sense of it by connecting it to earlier talk. Consider the misunderstanding that comes into the open at line 10. What is it that Gerald initially understood and that led him to a (cautious) affirmative response at line 7? It seems that he took Moritz’s kann-inquiry as questioning the validity of Katharina’s game move (announced at lines 1–3). Gerald’s cautious affirmation was not, then, a go-ahead for any building plans of Moritz’s, but a defense of Katharina’s move, and Moritz’s actual intention only becomes apparent when he picks out the relevant resource cards on his hand and announces that he will, in that case, build something (line 8).

Throughout our collection, kann-inquiries bring up new action plans. Here is one further illustration. During a family breakfast that has lasted for about half an hour, five-year-old Timon asks: kann ich aufstehen (‘can I get up’).

Extract 9

‘can I get up’ PECII_DE_Brkfst_20160424_2110402 (simplified)

Again, we see that this request to leave the table comes without “warning”: the last topic of conversation has been the cheese that Timon’s dad, Florian, is spreading on his bread roll (lines 1–3). After that, there are a few seconds of silence, filled with the babbling of Timon’s little sister, Emma. To be sure, the sight of a child sitting in front of an empty plate may suggest to the alert observer that this child may want to get up soon. However, Timon does not do anything that would make public any problem to which getting up would be the solution – say, ostentatiously displaying boredom. Instead, during the 6 s of silence (line 5), he observes his dad’s cheese-spreading for a second or so, then turns his gaze to his babbling sister, before launching his inquiry. In a word, Timon’s kann-inquiry comes out of the blue. It does not connect back to any problem that he would have made public.

Having illustrated the different sequential environments in which speakers select darf or kann to make a modal inquiry, we now turn to consider the forms of addressee participation that the two forms of inquiry invite. We begin, again, with darf-inquiries.

5 Response space

We have seen that speakers select darf and kann in systematically different situations to launch an inquiry about permission. The response spaces created by darf-inquiries and by kann-inquiries offer us further leverage for examining differences between these two verbs. In this section, we show that darf-inquiries, which nominate an action as a solution to a publicized problem, make relevant the authorization of the relevant action (or alternatively: blocking the action). In contrast, kann-inquiries, which nominate an action that broaches an entirely new project, invite a consideration of conditions that would make it (deontically) possible. While such consideration can lead to authorization, it regularly goes beyond merely giving a go-ahead.

We begin with a darf-inquiry that occurs during a game of Dixit. As part of this game, picture cards are laid out on the table (this is what Carola does at line 1), which then need to be considered by all players. At line 2, Antonia torques her body, bringing it closer to the cards. A moment later, as she extends her hand towards the cards, she asks, wos isn des (‘what is this’ [line 4]), making it explicit that she is having problems seeing (and making sense of) at least one of the cards. As she takes the card, she self-selects for a further turn-constructional unit (TCU) that addresses a darf-inquiry to her co-players: darf ich ma genau anschaun (‘may I take a close look’ [line 5]).

Extract 10

‘may I take a close look’ PECII_DE_Game_20160207_1549512

We can see that Antonia’s darf-inquiry, just like the cases in Extracts 5 and 7, emerges out of a problem that she has (seeing the picture on a game card) and that has already become public, both in Antonia’s embodied conduct (adjusting her body position, line 2) and in her talk (line 4). In her darf-inquiry, Antonia nominates the action she is carrying out as a solution to this problem.

We suggest that darf-inquiries target only authorization, because they come in a sequential context in which they nominate an action as a viable solution to a publicly known problem. In such a situation, all that is left to do for a person who is asked about permissibility is to give a go-ahead (or block the action). Indeed, we find that next speakers regularly provide token approval in turn-initial position. Carola grants Antonia’s request with a yes (line 7). Gisela provides her approval in a marked format, repeating the modal verb (darfst du, ‘you may’ [line 8]). She thereby orients to Antonia’s inquiry as specifically requesting a locally and contingently needed discretion (“regardless of what the codified rules of the game may have to say about this, I approve that you deal with your problem in this way”). This darf-inquiry, while seeking the co-players’ authorization, can be seen to lie on the border to a bouletic understanding, in the sense that not rules or norms, but needs and desires form the relevant background. In any case, Gisela’s marked response constitutes no more than a polar answer (Enfield et al. 2019). Looking back to the other darf-inquiries examined so far, we can see that all response speakers (Lena and Jaron in Extract 7, Lara in Extract 5) begin their responses with a polar answer (ja, ‘yes’, or a head nod in the case of Lena in Extract 7), even if they go on to expand their respective turns. Let’s compare this with responses to deontic kann-inquiries.

Here is an example of a kann-inquiry from another family breakfast. Not for the first time, Sibille and Christof are trying to get their daughter Nora to put away her mobile phone (lines 1–11). While this interaction takes its course, the family’s older daughter Lissi first briefly glances at her mum (line 5), then straightens up on the bench where she has been crouching, and produces a kann-inquiry: kann ich mir eben- kann ich mir die pferde vom (pappel)hof angucken (‘can I just – can I go look at the horses from the [pappelhof] stables?’ [lines 8–9]).

Extract 11

PECII_DE_Brkfst_20160213_3039443

As in earlier cases, this kann-inquiry comes out of the blue. There is no publicly known problem of Lissi’s that the nominated action would solve. Instead, her inquiry launches a new project: leaving the breakfast to watch horse videos or pictures.

Her mum’s response is largely affirmative, but consider the details. It does not begin with a polar answer token. Sibille’s response instead explores the conditions that would make a granting possible. She begins with a tentative approval (ich glaub ja, ‘I think yes’ [line 12]), then articulates a judgment-cum-proposal that would put Lissi’s horse-watching into the context of a more general change of activity on behalf of all the family (wir lösen dann die runde auch langsam auf oder, ‘we slowly bring proceedings to a close, right?’ [lines 12–13]), and she then formulates further conditions that the children should fulfill before turning to other pastimes (clearing away plates, closing the chocolate spread jar [lines 15–16]). In sum, Lissi’s kann-inquiry has created a context not simply for authorization, but rather for exploring deontic “possibilities” by formulating conditions that would make her wish acceptable.

Looking back at Extract 9, we now see that the situation was similar. Timon’s kann-inquiry about getting up from the table was met with a return question from Florian that inserts a sequence clarifying the conditions for approval (bist du satt, ‘are you full’ [line 8]) (see Schegloff [2007], on such “pre-second” insertions). Only after Timon confirms this question does Florian give his approval (with a nod and a soft ja [lines 10 and 12]), although Timon’s mum then further interrogates Timon (line 11) before he finally “can” get up. In this context, Extract 8 from the game of Catan represents an outlier: it is the only kann-inquiry that we have seen that does receive a version of ja (joa [line 7]) in response – but recall that Gerald’s response was based on a misunderstanding.

6 Body and sequence in modal inquiries

We now have the core of our analysis of kann-inquiries and darf-inquiries in place. Let us take a moment for a brief summary and consider the upshots of our findings. Both kann and darf are used in modal inquiries that seek approval, acceptance, or permission for an upcoming action. But as we have seen, the choice of one or the other verb is sensitive to the position of the inquiry in relation to a wider course of action. A kann-inquiry nominates an action as initiating a new activity. Coming “out of the blue”, it presents this new matter for consideration and, ultimately, permission. A darf-inquiry, by contrast, nominates an action as a chosen solution to an already public problem. This leaves nothing more to do for the addressed party than to let the nominated action happen (or to block it). With a darf-inquiry, a speaker seeks another’s approval so that the action they have identified as a solution would be carried out as “okayed” by relevant others.

The different contextual “habitats” of darf- and kann-inquiries have consequences for how deontic meaning can be achieved. The situation in which speakers select darf (person “A” is experiencing a problem, that problem has been publicly available, and “A” is nominating an action as a solution to this problem) is a very specific contextual constellation that naturally attracts a particular kind of deontic interchange: the only role left for the addressee is that of authorizer (or blocker). In contrast, the situation in which speakers select kann for a modal inquiry (person “A” broaches a new matter) is relatively generic and ubiquitous in social life, and open to a wide variety of developments. In other words, in the case of darf-inquiries, the emergence of an interchange with deontic meaning (permitting, accepting, approving of something) is promoted by the relation of the nominated action to ongoing public affairs. For kann-inquiries, this is not the case – these therefore rely on further interactional means for accomplishing deontic meaning.

Think back to Extract 9, in which Timon asks whether he “can” get up. The following aspects of the situation, at least, contribute to giving this kann-inquiry a deontic meaning (asking for permission): firstly, consider the way Timon designs his interactional move: he directs his gaze to the would-be authorizer, his dad; and he stays immobile, making no move to get up from the table, thus “waiting” for permission. Secondly, consider the social roles of child and father and the history of meal times that the two share in these roles (Stevanovic and Peräkylä 2012). These further elements of context provide for an interpretation of Timon’s inquiry as concerning permission (rather than, say, questioning his ability to get up against the background of his sore muscles).

To see this more clearly still, consider the following kann-inquiry that the participants do not treat as a request for permission. Three friends are getting into the car. At line 7, Julica begins to put on her seat belt: she torques towards the seat belt, turns her gaze around, and pulls the belt toward her. And now she notices something: one of the cameras, the one filming the road ahead, is mounted on that side of her car seat (see Figure 5). She voices this observation in a kann-inquiry: ach so, kann ich mich da jetzt anschnallen? (‘oh right, can I buckle up there now?’ [line 8]).

Extract 12

‘can I buckle up there now’ PECII_DE_Car20160924_13377

Note first that this kann-inquiry lives in the same contextual habitat as earlier ones: it comes “out of the blue”. Before Julica’s turn at line 8, there is nothing that could alert her friends that Julica is having a problem with the seatbelt. In fact, with her turn-initial achso, Julica herself frames her inquiry as concerning a problem that she encountered “just now” (on “achso” in a different context [Golato and Betz 2008]).

Note also that it is certainly possible to imagine giving this kann-inquiry a deontic meaning: Julica might be asking whether Carola minds her buckling up, in case this might ruin the camera set up. However, neither Julica herself nor her friends treat her kann-inquiry that way. Julica does not look to a would-be authorizer (say, Carola, since she is the one who mounted the cameras and is recording the event). Instead, Julica looks at the area where the camera might be blocking the seat belt. Also, Julica does not stay immobile and wait for permission – she pulls the seat belt towards her, thus testing whether she “can” in fact buckle up. And of course, in terms of the social roles in this group of friends, it is just implausible that Carola would prioritize the success of her recording over her friend’s safety, and thus prohibit buckling up. In sum, it seems clear enough that Julica’s kann-inquiry addresses not permissibility, but “circumstantial” possibility. Fittingly, it is Julica who answers her own question as she sees that it is “possible” to use the seat belt (line 8), and none of her co-passengers respond or even raise their heads, effectively treating Julica’s turn as self-talk.

We can see clearly now how context (the position of the inquiry within a sequence of actions) and visible behavior (gaze and posture orientation) enter into the construction and action of modal inquiries. This is summarized in Table 1.

Firstly, speakers create different contexts by orienting to the participation structure of the event. Speakers can treat another person as an authority whose permission is sought by looking at them and “waiting” while inquiring (e.g., Extracts 7 and 9) (see also Deppermann and Gubina 2021b). Alternatively, speakers can orient to the matter at hand, through gaze and manipulation, thereby treating others’ permission as less relevant or even irrelevant (e.g., Extracts 10 and 12). These aspects of embodied behavior create a distinct kind of context that provides an important part of the background for interpreting a particular modal “flavor”. Secondly, speakers nominate actions they want to carry out in different sequential environments: where the nominated action either presents a new matter, or where it is interpretable as a solution to a known problem. This positional kind of context informs the selection of kann or darf in modal inquiries. As the examples in Table 1 illustrate, sequential position (as indexed by modal verb selection) and orientation to an authority both contribute to the deontic quality of a modal inquiry.

Body and sequence in the accomplishment of modal meanings.

| Nominated action | Modal verb | Position in course of action | Gaze, body posture | Modal flavor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ex. 8 ‘do that’ | darf | Sequentially occasioned | Orientation to authority | Deontic |

| Ex. 11 ‘take a look’ | darf | Sequentially occasioned | Orientation to circumstances | Deontic/bouletic |

| Ex. 10 ‘get up’ | kann | Sequentially disjunct | Orientation to authority | Deontic |

| Ex. 13 ‘buckle up’ | kann | Sequentially disjunct | Orientation to circumstances | Circumstantial |

7 Deviant cases

As a last section of our analysis, we turn to the examination of deviant cases – data that do not seem to support our generalizations. The most relevant challenges for our analysis come from kann-inquiries concerning a problem that has already occupied the speakers, and from darf-inquiries that seem to come out of the blue. We consider relevant data for each of these constellations.

The first of these comes from another recording of three friends on a car ride. As the car waits at red lights, Carola broaches a possible course of action in a kann-inquiry (line 24): kann ich hier dann direkt n ju turn machen (‘can I make a U-turn here then directly?’ [line 3]).

Extract 13

‘can I U-turn right here then’ PECII_DE_Car_20171031_1_364820

The design of Carola’s inquiry gives away that this matter has occupied the women before. Her ‘then’ (dann [line 3]) displays a connection to something prior; the nominated choice of doing the U-turn “here directly” suggests that the matter of whether to do it at all has already been settled; and of course, the very action of doing a U-turn is something that drivers tend to do in response to a driving problem. Notice also that Carola’s turn does not include any turn-initial objects that would mark it as coming unexpectedly, such as an achso (‘oh right’ [Extract 12]) or an audible in-breath (Extract 8). Indeed, this modal inquiry does connect to a known-in-common problem: in the minute before this fragment, the women noticed that the road exit they had wanted to take is closed, and they decided to make a U-turn. Carola changed lanes accordingly and the car came to a standstill in front of red traffic lights. This is where our fragment sets in.

It would seem then that this is the “right” context for a darf-inquiry, and of course the selection of darf would be entirely possible here. But it would carry a different meaning: according to our analysis, it would nominate “doing the U-turn here directly” as Carola’s chosen solution to the problem, and would seek only authorization from her co-travelers. By selecting kann, Carola instead raises the action of “doing the U-turn here now” as a matter for consideration, opening up, as it were, a new sub-project within the global project of effecting a U-turn. In the way Carola designs her move, we see her own orientation to her modal inquiry as broaching a matter for joint consideration. She gazes to the road layout and “manipulates” it with her pointing gestures (see Figure 6). Upon possible completion of her utterance, she extends her turn to tentatively answer her own question (nee ne (.) ich muss schon da vorne nochmal (links), ‘no, right (.) I do have to go up there (left)’ [lines 4–6]). In sum, we can see some clear parallels to the way in which Julica designed her circumstantial inquiry in Extract (12), and Carola’s modal inquiry would seem to be open to be interpreted both circumstantially and deontically. Katharina’s response (lines 7–8) picks up on this openness: she first provides information about the (il-)legality of the move (das is in jedem fall illegal, ‘that is in any case illegal’ [line 7]) before suggesting how to best proceed in the given circumstances, aligning with the solution (or parts of the solution, the element vorne, ‘forward/ahead’ [line 6]) Carola has formulated in her own alternative: aber geh ruhig n stück weiter vor ja (‘but do go a bit further ahead yes’ [line 8]). Valeska joins in with yet another possible way to solve their problem (line 9), before Carola announces the solution she has settled on (lines 12–13). This case illustrates how practices of speaking (in our case: the selection of a kann-inquiry or a darf-inquiry) are not determined by context, but reflexively turn aspects of the situation into relevant context (Garfinkel 1967).

An important aspect of the situation that allows for Carola’s kann-inquiry to be heard as broaching a “new” matter for consideration is time. Carola produces her inquiry just as she has brought the car to a standstill in front of red traffic lights. The specific situation of waiting at traffic lights, with its relaxed temporality, thus sheds further light on the different trajectories that we have shown to be mobilized with kann- and darf-inquiries: while kann-inquiries invite consideration of the nominated action, darf-inquiries prefer a simple go-ahead. We see this when, a few moments later, the lights turn green and the car begins to move. Talk up to line 6 in Extract 14 (which is not a deviant case) is still occupied with banter about a previous outing. As the car approaches the spot where Carola was going to turn the car around, the multiactivity of driving and talking leads to disfluencies in her talk (lines 3–4) (Mondada 2012), until she finally abandons her in-progress TCU to produce a darf-inquiry: darf ich jetzt hier u-turnen (‘may I U-turn here now’ [lines 4–5]).

Extract 14

‘may I U-turn here now’ PECII_DE_Car_20171031_1_411340

Carola’s darf-inquiry comes at a moment when the nominated action is already in progress and it is all but too late to change it. Clearly Carola’s modal inquiry at this moment in time cannot lead to elaborate consideration, and her selection of darf shows that Carola only seeks the others’ approval so as to realize the action as okayed by all. The fact that Valeska in next position again points to the illegality of this maneuver in terms of the traffic rules (nie, ‘never’ [line 7]) does not change the course of events as Carola begins to turn the car around.

As a final case, we turn to a darf-inquiry that puts a challenge to our analysis that these are selected in sequential positions where the nominated action can be heard as the solution to a known-in-common problem. During a family breakfast (the same one as in Extract 9), two-year-old Emma is “playing” with a small piece of cheese, and her dad, Florian, watches her. She also has an untouched buttered bread roll on her plate. At line 2, Florian stretches out his hand to take hold of the bread roll, and he simultaneously launches a darf-inquiry: darf papa mal abbeißen hier (‘may dad take a bite off here?’). Emma blocks this action (line 3), and Florian retracts his hand as he registers his daughter’s refusal (line 4). After this, he goes back to monitoring Emma’s conduct.

Extract 15

‘may dad bite off here’ PECII_DE_Brkfst_20160424_18:35

There does not seem to be a publicly shared problem that Florian is experiencing in the run-up to his inquiry, to which taking a bite of Emma’s bread roll would be a possible solution. It rather seems that Florian just “wants” a bite of the bread roll. However, closer inspection reveals additional layers to Florian’s inquiry. Note that Florian monitors Emma’s conduct during the seconds leading up to his modal inquiry, and also that he goes back to this straight after its failure. These details might already be a sign that his inquiry does not spring simply from an appetite for bread roll. In fact, looking back in the interaction, this is not the first time Florian tries to get Emma to eat it. Some two minutes earlier (16:42), when Emma suggested she would lick the butter off the bread roll, Florian rejected this idea and instructed her to “bite off” some bread roll instead (nicht die butter ablecken, du sollst was abbeißen, ‘don’t lick off the butter, you are supposed to bite something off’). As it happens, Sarah does go on to lick butter off the bread roll, and so, 30 s later (and a good minute before our Extract 15), Florian intervenes: Emma, du sollst was abbeißen davon, nicht nur ablecken (‘Emma, you are supposed to bite something off that, not just lick it’). If we now go back to Extract 15, it is noteworthy that Florian formulates his nominated action (abbeißen hier, ‘bite off here’ [line 2]) in the same way as he had in his earlier instructions to Emma, when other formulations (such as the nominal einen biss haben, ‘have a bite’, or alternatives such as was abhaben, ‘have some’, or mal probieren, ‘try’) would have been available, and possibly more common – if the matter at hand was a request to share some food. These details of formulation suggest that Florian’s bid to bite off a piece of bread roll was instead a (maybe too subtle) parental ploy to finally get Emma’s eating of the bread roll off the marks. Note also that Florian here refers to himself in his parental role as papa, ‘dad’, while elsewhere in the interaction he refers to himself pronominally when talking to his daughter (Schegloff 1996). In sum, it seems that Florian’s selection of darf does carry an orientation to the nominated action’s connection to a known-in-common problem: that the bread role must finally be eaten (even though, of course, Florian taking a bite could at most begin to solve the problem that his daughter is making no progress in her food intake). Ultimately, this case supports our generalization that darf-inquiries place the nominated action in the context of a problem that is in common ground.

8 Discussion

In this study, we have examined how two modal auxiliaries of German, können (‘can’) and dürfen (‘may’), enter into turns that address the acceptability of some upcoming action. In the examined turns, these verbs occur in the first person (kann ich, ‘can I’) or in the third person with an impersonal pronoun (kann man, ‘can one/is it possible’), with interrogative or declarative word order (man kann, ‘one can/it is possible’). Accordingly, we have spoken of the turn structures in our focus as kann-inquiries and darf-inquiries. We have found the following systematic difference between the selection of kann versus darf: speakers select darf to nominate the action formulated by the verb phrase as a solution to a known-in-common problem. In contrast, speakers select kann to nominate the action formulated by the verb phrase as a new project.

Our evidence has mostly been sequential: speakers select darf to raise the acceptability of a nominated action in interactional contexts in which that same person has made a related problem they are experiencing publicly appreciable in the run-up to the darf-inquiry, by talking about it (Extracts 5 and 6, “may one eat in your car”), in their embodied behavior (Extract 7, “may one do that”), or both (Extract 10, “may I have a closer look”). Speakers select kann to raise the acceptability of a nominated action in interactional contexts in which nothing in the course of action so far has made this inquiry expectable, so that it comes “out of the blue” (e.g., Extract 8, “can one build at any time”; Extract 9, “can I get up”; Extract 11, “can I look at the horses”). The selection between the two verbs for achieving deontic meaning is intimately bound up with these two different positional orientations, as the examination of seemingly deviant cases has demonstrated (Extracts 13 and 15). Also, in cases where modal inquiries achieve other modal flavors (consider the circumstantial kann-inquiry in Extract 12 and the borderline-bouletic darf-inquiry in Extract 10), the sequential environments for kann and darf remain the same. In sum, we have demonstrated the relevance of a particular kind of context, sequential position, for the selection of modal verbs.

Previously, semantic theories have considered context to be important primarily for the accomplishment of a particular modal flavor, such as deontic as opposed to circumstantial meaning (e.g., Kratzer 1977). Our analyses support the view that one modal verb can achieve different modal flavors depending on aspects of context. We have focused on the speaker’s bodily (in particular, gaze) behavior as one element of turn-design that makes a kann-inquiry hearable as deontic or circumstantial (consider Extract 9 vs. Extract 12), or that participates in moving a darf-inquiry in a bouletic direction (consider Extract 7 vs. Extract 10). What these analyses suggest is that a normative conversational background is not simply “present” (say, traffic regulations when in the car, board game rules when playing a game), but that the efficacy of a normative background is actively achieved by speakers’ behavior.

It has been suggested that one quality that sets dürfen apart from other modal verbs is that it invokes an outside authority who decides upon the permissibility in question (e.g., Brünner and Redder 1983; Hentschel and Weydt 2013). Our analysis has demonstrated that kann-inquiries in deontic contexts orient to an authority just as much as darf-inquiries do. An appeal to outside authority then is not the crucial difference between deontic uses of dürfen and können. In fact, some of the most typical examples of requests for permission in our data are done with kann-inquiries, not darf-inquiries (see Extracts 9 and 11). Still, our data do show a connection between darf-inquiries and authority in the following way: since darf is selected to orient to the upcoming action as a ready solution to a known problem, all that is left to do for the addressed party is to authorize or block the nominated action. Darf-inquiries then address the other person(s) solely in their role as authorizer, and addressed parties regularly begin their (affirmative) response with a simple response token (a “yes” as, for example, in Extract 5, or a nod as in Extract 7). Deontic kann-inquiries, on the other hand, coming “out of the blue”, typically mobilize a contribution towards realizing the nominated action that goes beyond minimal authorization (considering the circumstances that would make nominated action acceptable as in Extracts 9 and 11, assisting by proposing ways forward as in Extract 13).

Some work has suggested that dürfen specifically presupposes a wish by the speaker to do something (e.g., Diewald 1999; Zifonun et al. 1997). Again, this observation does not seem to help us explain when darf is selected in deontic inquiries, as the children who ask whether they “can” get up in Extracts 10 and 12 clearly also wish to do so. However, our findings support these earlier intuitions in the following way: darf is selected in contexts in which the inquiry nominates an action as responsive to some already appreciable motive (the “wish” to eat something and to be warm, Extract 5; to find out “what this is”, Extract 10, etc.). It is the public status of the motive that seems to be crucial, not its presence.

Still other work has analyzed dürfen to be different from können in so far as the former, but not the latter, would, in deontic uses, encode the prospect of sanctions (Öhlschläger 1989). This analysis seems to be in line with some of our sequential findings: darf is selected for modal inquiries when the action to be carried out can be made accountable as a solution to a known-in-common problem. The main point of addressing an inquiry to co-present parties in such a situation at all seems to be to ensure that the action will be carried out as “okayed” by all. This is particularly clear in the recurrent cases where a darf-inquiry does not so much ask for permission, as it displays a sensitivity to the potentially problematic nature of an unfolding action and tries to get others on-board (Extracts 10 and 14).

Researchers of language usually consider modal verbs in relation to a system of semantic categories expressing different modal flavors. Here, we have examined a system of a different kind. A social event or course of action is a system with different ordered sequential “positions”, where each position invites considering potential actions in particular ways, or “modes”. An inquiry that broaches a new course of action (such as the kann-inquiries in our study) invites consideration of the conditions or circumstances that would make this action “possible”. In this context, deontic possibility (“permissibility” or “acceptability”) is one variety of enabling circumstances. An inquiry that prepares the ground for concluding an event or course of action (such as the darf-inquiries in our study) invites consideration of the nominated action for its “acceptability” or “desirability”. On the time-scale of interactional events, then, we see a development from circumstantial to deontic-bouletic modes of orienting towards an action – the same development that has been shown to be common on the time-scale of grammaticization processes (Bybee et al. 1994).

A caveat is in order. We have offered a qualitative exploration that has yielded systematic findings concerning the selection between modal verbs. Future research might aim to confirm or falsify these findings using statistical tests and a larger data base. Also, further research might examine to what extent the differences we have identified carry over to other action environments (say, making requests or mobilizing body adjustments with modal inquiries, see “Methods and Data” section). What we have shown here is that researchers’ attention to the extended contexts of actual social interaction can contribute to a better understanding of both the lexical semantics of modal verbs and of the nature of modal semantic categories.

Funding source: Leibniz-Gemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: #K232/2019

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge helpful feedback on earlier versions of this report by our colleagues in the NoRM-aL project, Uwe-A. Küttner, Laurenz Kornfeld, and Jowita Rogowska, and by Arnulf Deppermann and Alex Gubina.

-

Research funding: The reported work was supported by the Leibniz Association under a Leibniz Cooperative Excellence Grant (grant # K232/2019 to Jörg Zinken).

References

Bickel, Balthasar, Bernard Comrie & Martin Haspelmath. 2008. The Leipzig glossing rules: Conventions for interlinear morpheme-by-morpheme glosses. https://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/pdf/Glossing-Rules.pdf (accessed 17 May 2010).Search in Google Scholar

Brünner, Gisela & Angelika Redder. 1983. Studien zur Verwendung der Modalverben: Mit einem Beitrag von Dieter Wunderlich (Studien zur deutschen Grammatik 19). Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Bybee, Joan L. & Suzanne Fleischman. 1995. Modality in grammar and discourse: Papers from a symposium on mood and modality held at the University of New Mexico in 1992 (Typological Studies in Language 32). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Bybee, Joan L., Revere D. Perkins & William Pagliuca. 1994. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect, and modality in the languages of the world. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chevalier, Fabienne H. & Rebecca Clift. 2008. Unfinished turns in French conversation: Projectability, syntax and action. Journal of Pragmatics 40(10). 1731–1752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.12.007.Search in Google Scholar

Clift, Rebecca. 2001. Meaning in interaction: The case of actually. Language 77(2). 245–291. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2001.0074.Search in Google Scholar

Coates, Jennifer. 1983. The semantics of the modal auxiliaries. London: Croom Helm.Search in Google Scholar

Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth & Margret Selting. 2018. Interactional linguistics: Studying language in social interaction. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne & Singapore: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Curl, Traci S. 2006. Offers of assistance: Constraints on syntactic design. Journal of Pragmatics 38(8). 1257–1280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2005.09.004.Search in Google Scholar

Deppermann, Arnulf & Alexandra Gubina. 2021a. Positionally-sensitive action-ascription: Uses of Kannst du X? ‘can you X?’ in their sequential and multimodal context. Interactional Linguistics 1(2). 183–215. https://doi.org/10.1075/il.21005.dep.Search in Google Scholar

Deppermann, Arnulf & Alexandra Gubina. 2021b. When the body belies the words: Embodied agency with darf/kann ich? (“May/Can I?”) in German. Frontiers in Communication 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.661800.Search in Google Scholar

Diewald, Gabriele. 1999. Die Modalverben im Deutschen: Grammatikalisierung und Polyfunktionalität. Erlangen, Nürnberg, University: Habil.-Schr., 1998 (Reihe germanistische Linguistik 208). Tübingen: Niemeyer.10.1515/9783110945942Search in Google Scholar

ELAN . 2020. Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan (accessed 1 February 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Enfield, N. J., Tanya Stivers, Penelope Brown, Christina Englert, Katariina Harjunpää, Makoto Hayashi, Trine Heinemann, Gertie Hoymann, Tiina Keisanen, Mirka Rauniomaa, Chase W. Raymond, Federico Rossano, Kyung-Eun Yoon, Inge Zwitserlood & Stephen C. Levinson. 2019. Polar answers. Journal of Linguistics 55(2). 277–304. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226718000336.Search in Google Scholar

Fox, Barbara & Trine Heinemann. 2016. Rethinking format: An examination of requests. Language in Society 45. 499–531. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404516000385.Search in Google Scholar

Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Studies in ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.Search in Google Scholar

Golato, Andrea & Emma Betz. 2008. German ach and achso in repair uptake: Resources to sustain or remove epistemic asymmetry. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 27(1). 7–37. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsw.2008.002.Search in Google Scholar

Gubina, Alexandra. 2022. Grammatik des Handelns in der sozialen Interaktion: Eine interaktionslinguistische, multimodale Untersuchung der Handlungskonstitution und ‐zuschreibung mit Modalverbformaten im gesprochenen Deutsch. Mannheim: University of Mannheim PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Hentschel, Elke & Harald Weydt. 2013. Handbuch der deutschen Grammatik, 4th rev. edn. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110312973Search in Google Scholar

Hofstetter, Emily. 2021. Achieving preallocation: Turn transition practices in board games. Discourse Processes 58(2). 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1816401.Search in Google Scholar

Jefferson, Gail. 2004. Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In Gene H. Lerner (ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation, 13–31. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/pbns.125.02jefSearch in Google Scholar

Kaiser, Julia. 2017. “Absolute” Verwendungen von Modalverben im gesprochenen Deutsch: Eine interaktionslinguistische Untersuchung (OraLingua 15). Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter.10.33675/978-3-8253-7705-2Search in Google Scholar

König, Ekkehard. 1977. Modalpartikeln in Fragesätzen. In Harald Weydt (ed.), Aspekte der Modalpartikeln: Studien zur deutschen Abtönung (Konzepte der Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft 23), 115–130. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Kratzer, Angelika. 1977. What ‘must’ and ‘can’ must and can mean. Linguistics and Philosophy 1(3). 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00353453.Search in Google Scholar

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. Modality. In Arnim von Stechow & Dieter Wunderlich (eds.), Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung = Semantics (Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft 6), 639–650. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110126969.7.639Search in Google Scholar

Kroeger, Paul. 2018. Analyzing meaning: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics (Textbooks in Language Sciences 5). Berlin & Geneva: Language Science Press & European Organization for Nuclear Research. http://oapen.org/search?identifier=1000382 (accessed 1 February 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Küttner, Uwe-A., Laurenz Kornfeld, Christina Mack, Lorenza Mondada, Jowita Rogowska, Giovanni Rossi, Marja-Leena Sorjonen, Matylda Weidner & Jörg Zinken. In press. Introducing the “Parallel European Corpus of Informal Interaction” (PECII): A novel resource for exploring cross-situational and cross-linguistic variability in social interaction. In Margret Selting & Dagmar Barth-Weingarten (eds.), New perspectives in interactional linguistic research. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Mondada, Lorenza. 2012. Talking and driving: Multiactivity in the car. Semiotica 2012(191). 223–256. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2012-0062.Search in Google Scholar

Mondada, Lorenza. 2018. Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction 51(1). 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878.Search in Google Scholar

Mortelmans, Tanja, Kasper Boye & Johan van der Auwera. 2009. Modals in the Germanic languages. In Björn Hansen & Ferdinand de Haan (eds.), Modals in the Languages of Europe (Empirical Approaches to Language Typology [EALT]), 11–70. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110219210.1.11Search in Google Scholar

Narrog, Heiko. 2016. The expression of non-epistemic modal categories. In Jan Nuyts & Johan van der Auwera (eds.), The Oxford handbook of modality and mood (Oxford Handbooks in Linguistics), 89–116. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Nuyts, Jan, Pieter Byloo & Janneke Diepeveen. 2010. On deontic modality, directivity, and mood: The case of Dutch ‘mogen’ and ‘moeten’. Journal of Pragmatics 42. 16–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.05.012.Search in Google Scholar

Öhlschläger, Günther. 1989. Zur Syntax und Semantik der Modalverben des Deutschen. Heidelberg: Heidelberg University dissertation, 1981/82 (Linguistische Arbeiten 144). Tübingen: Niemeyer.Search in Google Scholar

Palmer, Frank R. 2001. Mood and modality, 2nd edn. (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Raymond, Chase W., Jeffrey D. Robinson, Barbara A. Fox, Sandra A. Thompson & Montiegel Kristella. 2021. Modulating action through minimization: Syntax in the service of offering and requesting. Language in Society 50(1). 53–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/s004740452000069x.Search in Google Scholar

Robinson, Jeffrey D. 2023. Audible inhalation as a practice for mitigating systemic turn-taking troubles: A conjecture. Research on Language & Social Interaction 56(2). 165–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2023.2205306.Search in Google Scholar

Rossi, Giovanni. 2012. Bilateral and unilateral requests: The use of imperatives and mix? Interrogatives in Italian. Discourse Processes 49. 426–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853x.2012.684136.Search in Google Scholar

Rossi, Giovanni & Tanya Stivers. 2021. Category-sensitive actions in interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly 84(1). 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272520944595.Search in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1996. Some practices for referring to persons in talk-in-interaction. In Barbara A. Fox (ed.), Studies in anaphora (Typological Studies in Language 33), 437–485. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.33.14schSearch in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2007. Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511791208Search in Google Scholar

Silverman, David. 2020. Interpreting qualitative data, 6th edn. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington, DC & Melbourne: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Stevanovic, Melisa & Anssi Peräkylä. 2012. Deontic authority in interaction: The right to announce, propose, and decide. Research on Language and Social Interaction 45(3). 297–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.699260.Search in Google Scholar

Thurmair, Maria. 1989. Modalpartikeln und ihre Kombinationen. Munich: University of Munich dissertation, 1987 (Linguistische Arbeiten 223). Tübingen: Niemeyer.10.1515/9783111354569Search in Google Scholar

van der Auwera, Johan & Vladimir A. Plungian. 1998. Modality’s semantic map. Linguistic Typology 2(1). 79–124. https://doi.org/10.1515/lity.1998.2.1.79.Search in Google Scholar

Wootton, Anthony J. 1997. Interaction and the development of mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511519895Search in Google Scholar

Zifonun, Gisela, Ludger Hoffmann & Bruno Strecker. 1997. Grammatik der deutschen Sprache, vol. 3. Berlin: De Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Zinken, Jörg. 2015. Contingent control over shared goods: ‘Can I have x’ requests in British English informal interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 82. 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.03.005.Search in Google Scholar

Zinken, Jörg & Eva Ogiermann. 2013. Responsibility and action: Object requests in English and Polish everyday interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction 46(3). 256–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.810409.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Clausal agreement on adverbs in Andi

- On analysing fragments: the case of No?

- Generic and vague uses of a second-person singular pronoun in an open-class person-reference system and speaker creativity in reported speech: the case of anata in Japanese

- Sequence, gaze, and modal semantics: modal verb selection in German permission inquiries

- Aspectual reduplication in Sign Language of the Netherlands: reconsidering phonological constraints and aspectual distinctions

- From LIKE/LOVE to habitual: the case of Mainland East and Southeast Asian languages

- Opening up Corpus FinSL: enriching corpus analysis with linguistic ethnography in a study of constructed action

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Clausal agreement on adverbs in Andi

- On analysing fragments: the case of No?

- Generic and vague uses of a second-person singular pronoun in an open-class person-reference system and speaker creativity in reported speech: the case of anata in Japanese

- Sequence, gaze, and modal semantics: modal verb selection in German permission inquiries

- Aspectual reduplication in Sign Language of the Netherlands: reconsidering phonological constraints and aspectual distinctions

- From LIKE/LOVE to habitual: the case of Mainland East and Southeast Asian languages

- Opening up Corpus FinSL: enriching corpus analysis with linguistic ethnography in a study of constructed action