Abstract

The present study aims to throw light on the behavior of the Spanish copulas ser and estar in locative sentences, beyond their classical distinction in terms of Individual-Level (IL) versus Stage-Level (SL) predicates. The behavior of the Spanish copulas in locative contexts constitutes an oddity that we aim to probe here: events (concierto ‘concert’), despite their clear spatial and temporal anchorage, combine with ser (El concierto es en París ‘The concert is in Paris’), which is the copula typically associated with IL or permanent predicates. To do so, we discuss the behavior of copulas as locative verbs in a broader empirical context, where not just events and individuals are considered, but also other types of nominals, such as qualities and states. We argue that ser emerges with events because time and place constituents combine directly with events, without the intermediation of extra predicational structure. When carrying a marked value, that extra predicational structure triggers the insertion of estar; when there is no predication structure (such as with events) and when the predication structure is unmarked (IL predicates), ser appears as the default copula.

1 Introduction: the problem

Most studies on the distribution of Spanish ser and estar focus on ‘adjective + copula’ constructions, and to a lesser extent on passive constructions. In this line, most theoretical approaches that try to explain the contrast in (1) through aspectual information related to the Individual-Level versus Stage-Level distinction or the contrast between perfectivity and imperfectivity (Arche 2006; Carlson 1977; De Miguel 1992; Fernández Leborans 1999; Leonetti 1994; Luján 1981; Milsark 1974; Roby 2009; Romero 2009; see Fábregas 2012; Leonetti et al. 2015 for an overview). Lately, this aspectual distinction has been operationalized through the dichotomy between central versus terminal coincidence prepositions contained within the complement of the copulative verb (Brucart 2012; Gallego and Uriagereka 2016; see also Camacho 2012 for a related approach that stems from Hale 1986 and its application to Spanish in Mateu 2002).

| Eva | {es/ | *está} | inmortal. |

| Eva | isser/ | isestar | immortal |

| ‘Eva is immortal.’ | |||

| Pedro | {está/ | *es} | desnudo. |

| Pedro | isestar/ | isser | naked |

| ‘Pedro is naked.’ | |||

With the exception of works that concentrate on the prepositional contrast as a way to approach the distinction between copulas, far fewer contributions are devoted to locative constructions, which constitute a quite intricate puzzle (cf., among others, Brucart 2010, 2012; Camacho 2012; Gallego and Uriagereka 2016; Zagona 2012). Briefly, the standard view assumes that animate entities and physical objects – or individuals – are located with estar, while events are located with ser (cf., for instance, Brucart 2012; Fernández Leborans 1999; RAE and ASALE 2009: Ch. 37.8):

| El | cuchillo | {está/ | *es} | en | la | cocina. |

| the | knife | isestar/ | isser | in | the | kitchen |

| ‘The knife is in the kitchen.’ | ||||||

| Pedro | {está/ | *es} | en | Roma. |

| Pedro | isestar/ | isser | in | Rome |

| ‘Pedro is in Rome.’ | ||||

| El | concierto | {es/ | *está} | en | el | anfiteatro. |

| the | concert | isser/ | isestar | in | the | amphitheater |

| ‘The concert is in the amphitheater.’ | ||||||

| La | fiesta | {es/ | *está} | en | mi | casa. | |

| the | party | isser/ | isestar | at | my | house | |

| ‘The party is at my house.’ | |||||||

This creates minimal pairs like (4), where the choice of the copula is in principle the only element that disambiguates between the two readings of examen ‘exam’ in Spanish: an event where someone is examined (4a), and an object, the written exam on paper or some other format (4b).

| El | examen | {es/ | *está} | allí. |

| the | exam | isser/ | isestar | there |

| ‘The examination takes place there.’ | ||||

| El | examen | {*es/ | está} | allí. |

| the | exam | isser/ | isestar | there |

| ‘The (written) exam is there.’ | ||||

In this study, we aim at discussing how to better account for this distribution. Thus, the goal of this article is modest, but we believe it necessary as a first step to attempt, with enough empirical support, a full account of the locative uses of ser and estar in an integrated theory of Spanish copulas.

Many of the existing approaches (see in particular those discussed in Section 4) treat Spanish copulas in locative contexts as determined by one single contrast: locating events versus locating individuals. In this article, we want to contribute to a deeper understanding of the use of the Spanish copulas in locative contexts by framing this traditional contrast in a broader empirical context where other nominal classes are considered. We observe that the use of ser and the incompatibility of estar with events are systematically left unexplained because the distribution of the copulas in Spanish has been simplistically reduced to a binary explanation, mostly in terms of IL versus SL predicates. This narrow dichotomy, we argue, does not fully account for all the entities that have the potential to combine with the Spanish copulas. This wider examination will let us determine whether the association between ser and the location of events is a positive or a negative property, that is, whether ser combines with locating events because ser somehow selects events, or whether ser combines with events because estar, its competitor, is specialized in states and ser is the default form. We propose that once contextualized in a broader empirical examination, it is possible to argue that ser is a default copula that lacks any type of feature specification and, at the same time, explain why it combines with events, without the need of proposing that ser has any specific feature that selects events.

As mentioned, to propose a unified theoretical analysis for this particular distinction from a synchronic point of view is not a simple matter, especially if one wants to give an account that is compatible with the copular distribution with adjectives or in passive contexts. One of the reasons why locative structures are usually left unexplained by the theoretical analyses is that these proposals primarily dealt with copular verbs in combination with adjectival attributes; even fewer studies have attempted to explain the copular alternation also present in locative structures. A significant example is Camacho’s (2012) detailed analysis of the aspectual properties of the two copulas in adjectival contexts; when moving to locative copular sentences, the proposal is simply to treat the locative PP as an adjunct. Let us show first why the distribution of copulas in locative contexts is theoretically problematic in a proposal that attempts to unify its distribution with adjectival contexts.

First of all, the information to which the copula is sensitive in locative contexts has a presumed origin in a syntactic position different from the one found in adjectival copulative sentences (cf. Demonte 1979). In (1) above, the copulas are differentiated by the nature of the complement of the copula, while in the locative sentences (2)–(4) it is the subject that determines the distribution. Indeed, the semantics of these subjects, particularly the ontological properties of nouns and not the type of location expressed by the complement of the copula is what seems to be behind the choice between ser and estar.

Most of the studies that describe the contrast between ser and estar with a focus on the uses with adjectives emphasize their aspectual differences (although acknowledging the existence of other factors; Luján 1981; Marín 2004; Schmitt 1992; Schmitt and Miller 2007), proposing that estar is [+perfective] and ser [−perfective] or unmarked for aspect, or differentiating the copulas by the type of predicate they create: predicates that apply to individuals (IL predicates) go with ser and are usually described as more permanent; predicates that apply to stages or happenings of individuals (SL predicates), usually go with estar, and are typically transient, bounded spatially and temporally (Camacho 2012; Fernández Leborans 1995; Lema 1995; Marín 2010). This description is at odds with the distribution in locative contexts for two reasons. The first one is that events, which are spatiotemporally anchored, exceptionally combine with ser in locative contexts. What a sentence such as (5) describes is neither permanent, nor involves an individual entity as a subject, but it clearly has a spatiotemporal argument.

| El | discurso | fue | entre | las 7 | y | las 8 | en | el | parlamento. |

| The | speech | wasser | between | the 7 | and | the 8 | at | the | parliament |

| ‘The speech was between 7 and 8 in the parliament.’ | |||||||||

At the same time, the distribution of estar in locative contexts is equally puzzling. For instance, a sentence such as (6) cannot be explained by the temporal or transient properties of estar, its perfective aspectual characteristics, or even the SL predicate it creates because it has the distribution and behavior of an IL predicate.

| Barcelona | está | en | el | Mediterráneo. |

| Barcelona | isestar | in | the | Mediterranean |

| ‘Barcelona is in the Mediterranean.’ | ||||

Therefore, one of the main questions we want to address in this study is the following: what makes an event special so that it combines with ser and cannot combine with estar as any other expression of location does? A further goal of this study is to introduce some intriguing and novel linguistic puzzles in this debate. Whereas we will not provide a full and definite answer to the questions posed by these puzzles at this point, we hope these will open a new debate in the field.

The structure of this article is the following: In Section 2 we will enrich the empirical picture about locative copular sentences and conclude that this empirical picture could give the prima facie impression that ser positively selects for events and cannot be considered a default copula. Section 3 explores two more contexts, beyond locative copular sentences, where an association between ser and the event reading can be found. These suggest that there might be a broader previously unnoticed generalization here, namely that the contrast between ser and estar cannot be based on a single aspectual dimension – IL versus SL or imperfective versus perfective – but has to be enriched to explain why ser is systematically associated to events. The analytical problem, which is discussed in the last two sections of the article, is how this apparent positive selection of events by ser can be made compatible with the status of ser as a default copula. Section 4 assesses a number of theories about the distinction between the Spanish copulas in locative contexts under the light of the empirical picture painted in Sections 2 and 3, differentiating among three main analytical options: (i) a unification of locative and other uses through one single feature, (ii) a unification of these uses with a system containing more than one sensitive feature, and (iii) a non-unifying approach where the locative copulas are distinct from the predicative copulas and the extension of ser and estar to locative sentences is the result of a surface syncretism. Section 5 concludes the article by proposing a possible way to integrate locative uses and the association between events and ser without giving up the claim that ser is the default copula in Spanish.

2 Ontological categories and location

Almost all syntactic approaches interpret estar as a more complex and specified element than ser, to the point that in some approaches, ser is assimilated to a spurious element without selectional properties that, like some analyses of English be, is introduced as a dummy element to support agreement (see Arche et al. 2019 for an overview, and also Brucart 2012; Escandell 2018; Escandell and Leonetti 2002; Gumiel-Molina et al. 2020; Sánchez Alonso 2018; Zagona 2012). There are good empirical reasons to make this proposal, revised in the works cited above. Some of those reasons are that estar coerces predicates to SL readings while ser does not coerce to an IL reading (Escandell 2018; Escandell and Leonetti 2002; Fábregas 2012); or that ser appears in identificational contexts lacking any predicative value (Fernández Leborans 1999) and is compulsory with relational adjectives that do not express properties (Gumiel-Molina et al. 2020).

However, the view in which ser is a default copula faces problems when one considers locative contexts because in such cases ser seems to be positively specified for events. As we will see in this section, ser combines with events, and estar combines ‘by default’ with anything else. Taken at face value, this goes against an approach in which ser is the elsewhere copula, and estar is specified for some type, as in (7).

| estar: type A |

| ser: Elsewhere |

There is a second logical possibility that has the negative consequence that it would force us to abandon the idea that ser is the default copula. Under this alternative view, ser, like estar, has its own selectional restrictions that become apparent in specific contexts. From this perspective, ser emerges in the event location contexts because of their positive selectional requisites: the two copulas divide the space of eventualities between each other, each one of them associated with one domain.

| estar: type A |

| ser: type B |

In this section, we will show that, indeed, in the locative domain it seems that estar is the default form, and ser is the verb that is specified for a particular class of subjects. We do this in order to show that there is a real descriptive and empirical problem here. Ultimately in this article, we will sketch a way to make these puzzling facts compatible with the well-established fact that ser is the default copula (Section 5), which we want to keep in our analysis. In this section and the next (Section 3), we want to convince the reader that the empirical pattern gives the impression that there is a positive selection of events by ser, even though we will later on show that this association is an epiphenomenon.

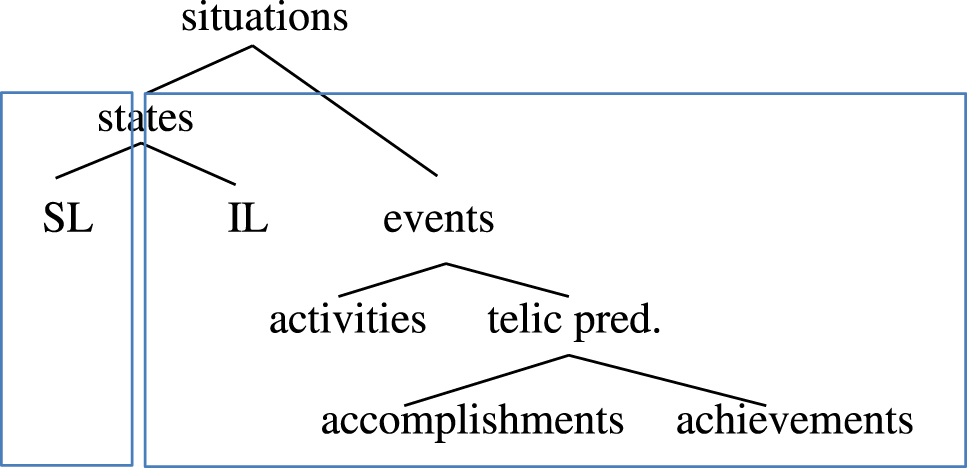

In the remaining of this section, we focus on the semantic properties of the nouns that can be located with ser/estar, and by doing so, we observe that this description needs not be limited to objects or individuals on the one hand, and events on the other hand (Section 2.1). As we will see in Section 2.2, there are other classes of nouns such as states (alegría ‘joy’) and qualities (firmeza ‘firmness’) that need to be considered, as these can also be located. After analyzing the semantic properties of the nominal classes, it becomes clear that there is only one ontological class that combines with ser, that of events, while states and any other entity that is not an event is systematically located with estar.

2.1 Object nouns and event nouns

Following the classification proposed by Fábregas and Marín (2012), we call ‘Object Nouns’ those nouns denoting any physical entity: either concrete objects, such as table or house, or animate individuals, such as teacher or Rosalía (9). On the other hand, ‘Event Nouns’ refer to non-physical entities that have a spatial and temporal anchor; i.e., entities that ‘take place’ (10).

| Juan, Marta, Saussure, alimento ‘food’, novio ‘boyfriend’, vaso ‘glass’, bala ‘bullet’, artículo ‘paper’, cirujano ‘surgeon’, avión ‘airplane’, víctima ‘victim’, lámpara ‘lamp’. |

| cena ‘dinner’, boda ‘wedding’, fiesta ‘party’, guerra ‘war’, accidente ‘accident’, concierto ‘concert’, conferencia ‘conference’, vacaciones ‘holydays’, congreso ‘congress’, entrevista ‘interview’, huelga ‘strike’. |

| reunión ‘meeting’, discusión ‘discussion’, operación ‘operation’, reparación ‘repair’, manifestación ‘demonstration’, asesinato ‘murder’. |

Note that in (9) and (10a) we have focused on underived nouns; some deverbal nominalizations (10b), of course, also denote events (Grimshaw’s 1990 ‘complex event nouns’), which pattern like the nouns in (10a) in terms of locative copulas; other nominalizations (Grimshaw’s 1990 ‘result nouns’) denote participants in the event (11), and as such, they pattern with (9):

| La | construcción | de | piedra | está | allí. |

| the | building | of | stone | isestar | there |

| ‘The stone building is there.’ | |||||

| La | construcción | del | puente | por | los | obreros | es | allí. |

| the | building | of.the | bridge | by | the | workers | isser | there |

| ‘The event of building the bridge by the workers takes place there.’ | ||||||||

As explained before, Event Nouns need to be located with ser (12a) and Object Nouns with estar (12b); this copula specialization holds strong for definite nous, but when locating an indefinite noun, -so no definiteness effects arise-, being the indefinite an event or an object, then both types of nouns combine with the same existential predicate, haber. Thus, the specialization is idiosyncratic to copular verbs:

| El | concierto | {es/ | *está} | en | Barcelona. |

| the | concert | isser/ | isestar | in | Barcelona |

| ‘The concert is in Barcelona.’ | |||||

| La | mesa | {está/ | *es} | en | la | cocina. |

| the | table | isestar/ | isser | in | the | kitchen |

| ‘The table is in the kitchen.’ | ||||||

| Hay | un | concierto | en | Barcelona. |

| have | a | concert | in | Barcelona |

| ‘There is a concert in Barcelona.’ | ||||

| Hay | una | mesa | en | la | cocina. |

| have | a | table | in | the | kitchen |

| ‘There is a table in the kitchen.’ | |||||

As already advanced, a subset of nouns such as cena ‘dinner’, examen ‘exam’, fuegos artificiales ‘fireworks’, obra de teatro ‘theater play’ can be located with both copulas, ser and estar, depending on their interpretation (Perpiñán et al. 2020). When clase ‘classroom’ refers to the physical space, it needs to combine with estar (14b), but when it refers to the lecture given during that class it combines with ser (14a).

| La | clase | es | a | las | 10. |

| the | class | isser | at | the | 10 |

| ‘The class is at 10.’ | |||||

| La | clase | está | en | el | primer | piso. |

| the | classroom | isestar | on | the | first | floor |

| ‘The classroom is on the first floor.’ | ||||||

In the following paragraphs, we will present the most relevant differences and similarities between these two types of ontological entities in order to later account for their distribution with the Spanish copulas.

Objects and events share the property of being countable: dos mesas ‘two tables’; tres reuniones ‘three meetings’, and they both can be located, but they differ in several other properties. As shown in the following examples, taken from Huyghe and Azzopardi (2019), objects can be modified in their different physical dimensions, as in (15), whereas events, as abstract entities, cannot, as in (16).

| un hilo amarillo/una silla naranja. |

| ‘a yellow thread/an orange chair.’ |

| una manzana de 200 gramos/un barco de tres toneladas. |

| ‘a 200 g apple/a three-ton ship.’ |

| una mesa de vidrio/una falda de algodón. |

| ‘a glass table/a cotton skirt.’ |

| #una conferencia amarilla/#un congreso naranja. |

| ‘a yellow conference/an orange congress.’ |

| #una reunión de 200 gramos/#un entierro de tres toneladas. |

| ‘a 200 g meeting/a three-ton burial.’ |

| #un concierto de vidrio/#un juicio de algodón. |

| ‘a glass concert/a cotton trial.’ |

Objects and events also differ in their temporal dimension. Observe, first, that events (17) convey a temporal extension that objects lack (18).

| una reunión de dos horas. |

| ‘a two hours meeting.’ |

| La reunión duró poco más de dos horas. |

| ‘The meeting lasted just over two hours.’ |

| #una mesa de tres horas. |

| ‘a three hours table.’ |

| #La mesa duró un poco más de tres horas. |

| ‘The table lasted just over three hours.’ |

Second, event nouns – but not object nouns – can function as temporal frames or locators and, hence, be introduced by temporal prepositions, as in the following examples, also taken from Huyghe and Azzopardi (2019).

| durante la manifestación. |

| ‘during the demonstration.’ |

| a lo largo de la ceremonia. |

| ‘throughout the ceremony.’ |

| en el momento del rodaje. |

| ‘at the time of filming.’ |

| *durante la estantería. |

| ‘during the shelving unit.’ |

| *a lo largo del yogur. |

| ‘throughout the yogurt.’ |

| *en el momento del tenedor. |

| ‘at the time of the fork.’ |

Third, event nouns can combine with predicates such as verse interrumpido ‘to be interrupted’ or modifiers such as en curso ‘in progress’ (Fábregas et al. 2012); a possibility that objects do not exhibit. Verse interrumpido requires an internal argument that exhibits some temporal progression so that it can be interrupted before its natural end, and this is only satisfied by event-denoting nouns that involve a dynamic change. In the same way, en curso requires internal dynamic change that physical entities lack.

| El rodaje se ha visto interrumpido. |

| ‘Filming has been interrupted.’ |

| una operación en curso. |

| ‘an operation in progress.’ |

| *La estantería se ha visto interrumpida. |

| ‘The shelving unit has been interrupted.’ |

| *el tenedor en curso. |

| ‘the fork in progress.’ |

But probably the most significant difference between these two types of nouns is that events take place, both in space and time, (23), while objects, (24), do not.

| La reunión tuvo lugar ayer en París. |

| ‘The meeting took place yesterday in Paris.’ |

| El concierto tendrá lugar el mes que viene en Barcelona. |

| ‘The concert will take place next month in Barcelona.’ |

| *La mesa/casa tuvo lugar ayer/en París. |

| ‘The table/house took place yesterday/in Paris.’ |

| *El gato tendrá lugar el mes que viene en Barcelona. |

| ‘The cat will take place next month in Barcelona.’ |

From here – the fact that events but not objects can be located in time – it naturally follows that ser is the only copula that can locate in time; by the same token, estar is not compatible with expressions that locate in time.

| El | concierto | {es/ | *está} | {a | las | 10/ | ahora/ | más | tarde}. |

| the | concert | isser/ | isestar | at | the | 10/ | now/ | more | late. |

| ‘The concert takes place at 10 o’clock/now/later.’ | |||||||||

2.2 State nouns and quality nouns

According to several authors (Arche and Marín 2014; Fábregas 2016; Jaque and Martín 2019), in addition to individuals and events, there are at least two other ontological noun types: states (26) and qualities (27). The nouns in (26) are used to denote temporal periods associated with eventualities, but lack any type of dynamicity or change: either when they denote the resulting state or other types of states, the nouns in (26) are not events.

| admiración ‘admiration’, alegría ‘joy’, deseo ‘desire’, desprecio ‘contempt’, decepción ‘disappointment’, disgusto ‘dislike’, enfado ‘anger’, envidia ‘envy’, fascinación ‘fascination’, frustración ‘frustration’, indignación ‘indignation’, inquietud ‘restlessness’, irritación ‘irritation’, nostalgia ‘nostalgia’, odio ‘hate’, perplejidad ‘perplexity, preocupación ‘worry’, rabia ‘rage’, sorpresa ‘surprise’, tristeza ‘sadness’. |

With respect to (27), they denote the abstract name of a quality, defined typically by their morphological base, which is an adjective.

| altura ‘height’, audacia ‘audacity’, belleza ‘beauty’, excelencia ‘excellence’, firmeza ‘firmness’, fortaleza ‘strength’, frescura ‘freshness’, hermosura ‘loveliness’, honestidad ‘honesty’, inteligencia ‘intelligence’, modestia ‘modesty’, prudencia ‘prudence’, sabiduría ‘wisdom’, sencillez ‘simplicity’, valentía ‘courage’, verosimilitud ‘verisimilitude’. |

Notably, these two types of nouns have an uncontroversial abstract denotation at least in the sense that they do not denote physical objects with a spatial location, a characteristic that has sometimes been adduced to explain the different behavior of events in comparison to objects and in particular to explain its late acquisition in L1 and L2 (Sera 1992). From this perspective, one could expect that estar will not be the copula to locate them, especially if estar selects physical objects as the subjects it locates. Thus, if estar is the only copula with selection restrictions and ser is the default, it is surprising that both states (28) and qualities (29) always require estar in locative sentences, despite its abstractness.

| Toda | su | frustración | {está/ | *es} | en | lo | que | ha | escrito. |

| all | her | frustration | isestar/ | isser | in | it | that | has | written |

| ‘All her frustration is in what she has written.’ | |||||||||

| La | {alegría/ | nostalgia} | {está/ | *es} | solo | en | su | cabeza. |

| the | joy/ | nostalgia | isestar/ | isser | only | in | her | head |

| ‘Joy/nostalgia is only in her head.’ | ||||||||

| ¿Dónde | {está/ | *es} | ahora | la | {preocupación/ | rabia} | que | tenías? |

| where | isestar/ | isser | now | the | concern/ | anger | that | had.2sg |

| ‘Where is now the concern/rage you had?’ | ||||||||

| La | belleza | {está/ | *es} | en | el | interior. |

| the | beauty | isestar/ | isser | in | the | inside |

| ‘Beauty is in the inside’ | ||||||

| ¿Dónde | {está/ | *es} | tu | firmeza? |

| where | isestar/ | isser | your | determination |

| ‘Where is your determination?’ | ||||

| (adapted from Brucart 2012) | ||||

| No | sé | dónde | {está/ | *es} | la | {inteligencia/ | valentía} | de | ||||

| not | know | where | isestar/ | isser | the | intelligence/ | bravery | of | ||||

| la | que | tanto | presumía. | |||||||||

| the | that | much | bragged | |||||||||

| ‘I don’t know where the intelligence/bravery she bragged so much about is.’ | ||||||||||||

Considered from this perspective, then, the question is what makes events incompatible with estar. With this in mind, we will now describe the properties of state and quality nouns compared to those of object and event nouns. Only with a complete picture of the grammatical characteristics of all ontological types of nouns that can be located, will we be able to properly account for the place events occupy in this classification. We will test state and quality nominals with the same diagnostics used to describe objects and events in the preceding section.

Observe, first, that both states (30a), and qualities (30b), are not count nouns, unlike event nouns, particularly those that are underived from verbs (31).

| *Los jóvenes tienen muchas indignaciones/tristezas. |

| ‘Young people have many indignations/sadnesses.’ |

| *Los monjes tibetanos tienen tres fuerzas/sabidurías. |

| ‘Tibetan monks have three forces/wisdoms.’ |

| Hay | programados | cuatro | conciertos. | |

| there | are | scheduled | four | concerts |

| ‘There are four concerts scheduled.’ | ||||

States and qualities, unlike events, take place neither in space nor in time:

| *La indignación/tristeza (de tu hermano) tuvo lugar en París/ayer. |

| ‘(The) outrage/sadness (of your brother) took place in Paris/yesterday.’ |

| *La fuerza/sabiduría (del monje) tuvo lugar en el Tíbet/el mes pasado. |

| ‘(The) force/wisdom (of the monk) took place in Tibet/last month.’ |

| El concierto tuvo lugar en Barcelona/hace un año. |

| ‘The concert took place in Barcelona/a year ago.’ |

Event nouns can combine with predicates such as verse interrumpido ‘to be interrupted’ or modifiers such as en curso ‘in progress’ (Fábregas et al. 2012); this is not possible with states or qualities.

| El rodaje se ha visto interrumpido. |

| ‘The filming has been interrupted.’ |

| una operación en curso. |

| ‘an operation in progress.’ |

| *La admiración se ha visto interrumpida. |

| ‘Admiration has been interrupted.’ |

| *la perplejidad en curso. |

| ‘perplexity in progress.’ |

| *La belleza se ha visto interrumpida. |

| ‘Beauty has been interrupted.’ |

| *la honestidad en curso. |

| ‘honesty in progress.’ |

As we have seen in the preceding section, event nouns are compatible with temporal locators; in contrast, neither states nor qualities are, as they do not denote eventualities that can progress along a temporal scale:

| *durante la indignación. |

| ‘during indignation.’ |

| *a lo largo de la alegría. |

| ‘throughout happiness.’ |

| *durante la hermosura. |

| ‘during beauty.’ |

| *a lo largo de la prudencia. |

| ‘throughout prudence.’ |

However, this does not mean that quality and state nouns do not contain any type of temporal information. While it is still a matter of debate whether quality nouns convey some type of temporal information (cf. Zato 2020 and references therein), there is little doubt about the temporal dimension of states, as shown in (39), where they allow temporal modifiers introduced as prepositional phrases. Some partial evidence for the temporal information of quality nouns might come from the fact that, like state nouns and event nouns, they can be the subject of a verb like durar ‘to last’.

| un cabreo de dos horas. |

| ‘an anger of two hours’ |

| ??una belleza de varios años. |

| ‘a beauty of several years’ |

| El cabreo me duró toda la tarde. |

| ‘The anger lasted all afternoon.’ |

| Su pobreza duró muchos años. |

| ‘Her poverty lasted many years.’ |

| El concierto duró toda la tarde. |

| ‘The concert lasted all evening.’ |

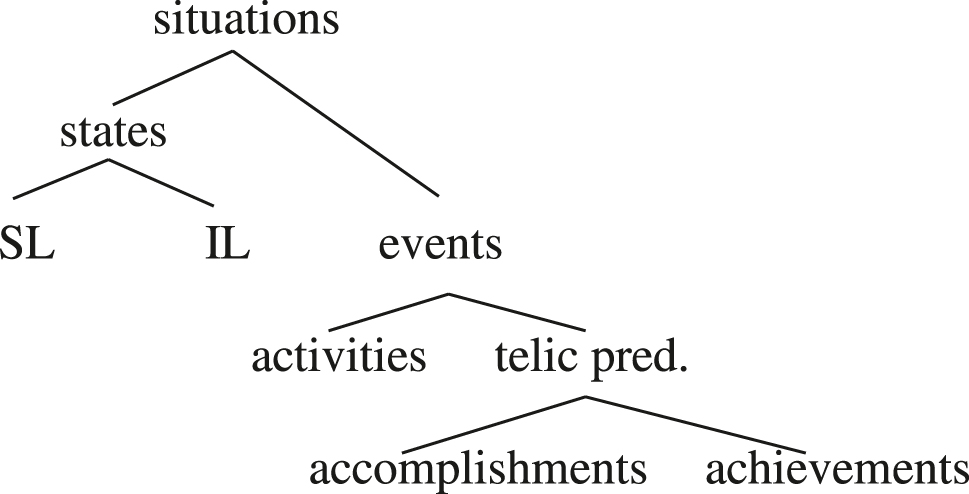

The fact that state nouns and possibly quality nouns, like event nouns, have a temporal dimension is very informative regarding whether a subject is located with ser or estar. It is particularly illuminating to compare event nouns and state nouns, as they both belong to the set of eventualities (Bach 1986). Attending to the fact that events are located with ser and states are located with estar we have to conclude that it is not the temporal dimension per se that triggers events to combine with ser. As we have seen, state nouns, despite having a duration and allowing temporal anchoring, combine with estar. In this respect, the main difference between these two classes of nouns is that events include in their temporal denotation the idea of change, action or progression, which is completely absent from the case of state nouns. Therefore, the main difference between these two classes of nouns is their inner aspect, not their coarser properties, such as whether they are concrete or abstract or even whether they are bounded or not (Table 1).

Semantic characterization of the ontological types of nouns.

| Events | Objects | States | Qualities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | + | + | − | − |

| Duration | + | − | + | − |

| Take place | + | − | − | − |

| En curso ‘in progress’ | + | − | − | − |

| Temporal locator | + | − | − | − |

| Estar | − | + | + | + |

| Ser | + | − | − | − |

In a nutshell, events constitute an altogether different class of nouns, presumably because only eventive nouns include in their denotation the idea of internal phases in their development, as emphasized – among others – in Grimshaw (1990) or Borer (2013). That is, event nouns are dynamic in a strict sense.

As a conclusion of this section, the behavior of state nouns and quality nouns shows that all nouns except for events are located with estar. This contradicts the general view that ser is a default copula that lacks any selectional capacity: in locative contexts, ser positively selects events and estar combines with anything else. One is then tempted to propose the generalization in (41).

| Ser selects events in locative copular sentences. |

Note in this respect that the location of an event is eventive itself. Assuming that the progressive periphrasis -always with estar- is a good test for eventivity, note that (42) behaves as an eventive location, while the location of anything that is not an event is stative. We hasten to nuance the claim about (42) being an eventive location to emphasize that, of course, (42) does not involve an eventive location in the sense that there is a displacement across a trajectory (in fact, see Section 3.1 below about the so-called path locations); however, it involves an eventive location in the sense that there is a progressive change or action that is identified by its temporal and spatial location.

| La | entrevista | es | en | el | tercer | piso. |

| the | interview | isser | on | the | third | floor |

| La | entrevista | está | siendo | en | el | tercer | piso. |

| the | interview | isestar | beingser | on | the | third | floor |

The claim in (41) is theoretically undesirable. It would imply that we have one default copula in the locative domain (estar) and a second default copula in non-locative uses (ser). This would make it impossible to unify the uses of copulas because it would force us to treat locative copular sentences as different from other types of copular predicates. Still, we want to preserve the idea that ser is always the default copula, but at the same time establish as an empirical fact that there is a real correlation between ser and events that requires an explanation.

At this point, two questions emerge. The first one is whether it is possible to identify other instances of ser with events beyond the purely locative context that has just been revised, and the second is how the association between events and ser can be made compatible with the general observation that ser is an IL copula and, more generally, a default copula in any other type of copulative structure. The next section is devoted to the first question, which we believe should be answered affirmatively: there are other contexts where ser combines with events.

3 Ser and events: path copular sentences and passives

We have already shown that in the domain of locative copular sentences, the empirical picture suggests that ser is a copula that specifically locates events, and estar is the copula that locates anything that is not eventive.

| {Juan/ | su | belleza/ | su | preocupación} | está | allí. |

| Juan/ | his | beauty/ | his | concern | isestar | there |

| El | concierto | es | allí. |

| the | concert | isser | there |

What we will show in this section is that ser combines with events in a broader set of contexts than previously acknowledged. Here we will concentrate on two of them, path copular sentences (Section 3.1) and eventive passives (Section 3.2).[1]

3.1 Path copular sentences

Thus far, we have drawn the following generalization: objects, as well as states and qualities, are located with estar, while the location of events requires ser. However, this is not completely accurate, as certain objects may combine with ser when their interpretation is deictically linked. The following sentences, taken from Brucart (2012), exemplify the phenomenon we refer to:

| El | aeropuerto | es | por | ahí. |

| the | airport | isser | by | there |

| ‘The airport is that way.’ | ||||

| El | decanato | es | en | frente. |

| the | dean’s office | isser | in | front |

| ‘The dean’s office is facing us.’ | ||||

| La | parada | de | taxis | es | en | la | próxima | esquina. |

| the | stand | of | taxi | isser | on | the | next | corner |

| ‘The taxi stand is on the next corner.’ | ||||||||

According to Brucart (2012: 33), this pattern involves a path interpretation of the relevant preposition where the entity in the subject position, although not an event, is located at the end of the path that is defined in the post-copular expression. For Brucart (2012) this path interpretation is what makes the use of ser available. Although quite productive, in Brucart’s description, the pattern is constrained by pragmatic conditions: (i) “it usually implies a prior request for information about the location of the corresponding place by the hearer”; (ii) “the subject typically denotes a fixed place where certain activities and services take place”; (iii) the utterance situation should be “deictically anchored to the entity that is spatially located”, and perhaps most crucially, (iv) “the sentence denotes the route that the hearer must follow to reach the goal of the path” (Brucart 2012: 33). For us, the crucial property is the last one: the hearer must follow the path to reach the location as a goal. The question is whether this dynamic interpretation is part of some kind of pragmatic condition, as Brucart proposes, or not. If there is such a pragmatic requirement, the sentences in (45) take ser because of the presence of a path; if there is not such a pragmatic requirement, then the presence of an event reading – even if the event is intended and not instantiated – determines the presence of ser. We believe that the second explanation is the correct one. Importantly, paths can be combined with both copulas, as shown in (46) (see Zagona 2012).

| La | farmacia | está | hacia | el | puente. |

| the | pharmacy | isestar | towards | the | bridge |

| La | farmacia | es | hacia | el | puente. |

| the | pharmacy | isser | towards | the | bridge |

In both cases, the path preposition is interpreted in a way similar to what Svenonius (2010) calls ‘end-of-journey’ or ‘Cresswellian locations’, that is, the figure is located at the end of the path that the prepositional structure defines. Zagona (2012) proposes that in sentences like (46) the preposition lacks the path component, but it is clear that this path component is interpreted and the figure is located at the end of that intended path that extends to a location close to the bridge. Thus, the notion of path itself cannot be what distinguishes (46a) from (46b). And still, the interpretation of (46a) is different from (46b), where we understand that an unidentified speech participant is supposed to follow that path. Our claim is that what makes (46a) and (46b) different is that only in (46b) does one interpret that there is an intended event that is required to reach the intended location: in (46b), but not necessarily in (46a), the addressee not only must have asked for directions to arrive to the pharmacy, as Brucart already noticed, but she also had the intention of going to that place, presumably to do something there – a secondary point that we will get back to in a moment.

In fact, it is possible to license the alleged path copular structures with ser in contexts where there is absolutely no path at all to follow, but where the idea of the presence of an intended event is valid. Consider (47).

| -¿Dónde | es | la | farmacia? |

| where | isser | the | pharmacy? |

| -La | farmacia | es | aquí. |

| the | pharmacy | isser | here |

(47) can be an exchange where someone is looking for a pharmacy and asks somebody at the door of a shop; that person answers that the addressee is already in the location of the pharmacy. That is: there is no further path that has to be traversed to arrive at the pharmacy, but there is an intended arrival, which seems to license the ser copula in this context. Secondarily, the notion of intended event is present in these constructions, which we now know are wrongly called ‘path copular sentences, through the nature of the subject. These types of sentences, as pointed out by Salazar (2002), tend to sound natural to the extent that the figure located is in a place where one typically performs some kind of action or event, which can be ‘buying’ (as in 47), ‘visiting’ (48a), ‘receiving a treatment’ (48b) or many other types of actions. Locations that are difficult to conceptualize as places where one can perform an event are more difficult to accept unless one contextually assigns an event function to them (as in [49c], if we decide that rock is the goal in a marathon or determine that it is a touristic attraction that one visits).

| La | iglesia | es | por | ahí. |

| the | church | isser | by | there |

| ‘The church is over there’ | ||||

| El | hospital | es | por | ahí. |

| the | hospital | isser | by | there |

| ‘The hospital is over there’ | ||||

| El | puerto | es | por | ahí. |

| the | harbor | isser | by | there |

| ‘The harbor is over there’ | ||||

| #La | estrella | polar | es | por | ahí. |

| the | star | polar | isser | by | there |

| ‘The polar star is over there.’ | |||||

| #El | centro | de | la | tierra | es | por | ahí. |

| the | center | of | the | earth | isser | by | there |

| ‘The center of the earth is over there.’ | |||||||

| #La | roca | es | por | ahí. |

| the | rock | isser | by | there |

| ‘The rock is over there.’ | ||||

This – that the copula ser is only licensed if the interpretation implies an intended event, be it a path that has to be traversed or some action that one performs in the location if the path disappears – is how we interpret the following Brucart’s observation: “if ser is commuted by estar in these sentences, the notion of route is weakened and the new construction becomes an ordinary locative attributive” (Brucart 2012: 33). Hence, sentences of the type of (50), including a directional preposition, can only accept ser:

| Al | aeropuerto | es | por | ahí. |

| at.the | airport | isser | that | way |

| *Al | aeropuerto | está | por | ahí. |

| at.the | airport | isestar | that | way.’ |

In our view, the reason for this contrast is that the path preposition forces the interpretation of an intended event that involves the interlocutor, at a minimum ‘arriving at the airport’. This forces an event interpretation, and like in the case of the locative copular sentences, the copula used must be ser. Thus, if sentences with ser like (45) can be licensed by a path interpretation, this is because the notion of path can be used to give content to the intended event that the copula requires, not because the path itself licenses that copula. So-called ‘path copular structures’, we believe, should be rather called ‘intended event copular sentences’ (see also Sánchez Alonso 2018, who independently reaches a similar conclusion based on a different argumentation; see also Section 4.2 below), even if the path reading is the easiest way to give content to the intended event. Likewise, we argue, there might be a second set of structures that, like locative copular sentences, involve an event interpretation of the whole clause, only that in this case it would be an intended event.

3.2 Passives and structures with participles

According to Coussé (2011) and Marín (2016), among others, participles of telic verbs – i.e., those verbs including an endpoint (a telos) – can denote both events and states; it depends on the temporal perspective adopted with respect to the boundary. In certain cases, as in (51), the temporal perspective ends at that point, since it is denoted by an event that culminates. In other cases, (52), the perspective adopted starts just after that point, since it is denoted a resultant state.

| La | puerta | ha | sido | cerrada/ | pintada. |

| the | door | has | beenser | closed/ | painted |

| El | tornillo | ha | sido | apretado/ | retorcido. |

| the | screw | has | beenser | fastened/ | twisted |

| La | puerta | está | cerrada/ | pintada. |

| the | door | isestar | closed/ | painted |

| El | tornillo | está | apretado/ | retorcido. |

| the | screw | isestar | fastened/ | twisted |

As illustrated, eventive passives are built with ser (51), while stative passives are built with estar (52) (Bosque 1990; Fernández Leborans 1995; Jaeggli 1986; Luján 1981, among many others). This is what we observe for telic predicates, whose participles have the double possibility to denote the resulting state of a previous event, as in (52), or to denote the complete event, as in (51). Crucially, in the case of activities or processes, only eventive passives are available because the participle does not have the possibility to denote the resulting state that follows the completion of the event, as these events are atelic and lack a natural endpoint. Thus, only ser is allowed because the participle must denote an event.

| El | coche | {fue/ | *estuvo} | empujado. |

| the | car | wasser/ | wasestar | pushed |

| La | gata | {es/ | *está} | acariciada. |

| the | cat | isser/ | isestar | caressed |

In the passive, then, we have another context where ser directly associates to event interpretations, this time not expressed by the subject but rather by the complement of the copula. As in the case of locative copular sentences, this property should be a priori unexpected if the only information that the copulas care about is the distinction between IL and SL predicates. This would be incompatible with a view in which ser is the default member of the set of copulas and lacks any type of selectional restrictions.

Of course, we should keep in mind that, in general, Individual Level predicates are associated with the copula ser, and Individual Level predicates are the purest form of non-eventive element, something that is – in principle – difficult to integrate with the present empirical overview, where ser is related directly to eventive interpretations. The picture is, then, extremely puzzling: what should IL predicates have in common with events, to the exclusion of SL predicates?

Then, we move on to the second problem mentioned at the end of Section 2, namely, whether it is possible to integrate this empirical picture with the more general uses of the copulative verbs in other predicative contexts. In order to do so, we will revise a number of approaches to the locative copula and the nature of copulative verbs in general, to see which ingredients they provide as tools to potentially explain this connection.

4 An assessment of existing accounts and a possible way forward

As we have already illustrated, the facts in Section 2 suggest that it is not possible to give a general unified account of the ser/estar distribution based on a single difference, such as the IL versus SL distinction, at least if locative and adjectival uses of the copulas are to be treated as reflecting the same structure. The empirical view in the case of locative copular sentences is as follows:

Within the domain of locative sentences, ser selects eventive locations

Within the domain of locative sentences, estar selects stative locations

In this section, we will review several prominent analyses of the locative uses of ser and estar, and critically assess them in terms of what these analyses are able to capture and what they leave unexplained. In this review, we will also make the effort of confronting some other analyses that do not directly discuss the locative uses, to see how they can be extended to cover these cases. Given the extremely high number of studies about the Spanish copulas, it will be impossible to cover all analyses with their variations, and we will focus on a relatively small set that we consider representative of the main approaches to the contrast.

We will divide the approaches using two parameters: (i) whether their goal is to unify the use of ser and estar within the same type of contrast and (ii) whether ser is assumed to be an absolute default lacking any specification. See Leonetti et al. (2015) for a different type of overview, where they concentrate on the problem of whether the distinction is lexical, syntactic, or semantic.

In this overview, we present five approaches that attempt to unify the locative uses with the use in combination with adjectives, and one that treats them as different (Section 4.6). Among the unifying approaches, two treat ser as lacking a feature that estar has (Sections 4.1 and 4.2), two associate different positive specifications to each copula (Sections 4.3 and 4.4) and one assimilates the location of events to the building of IL predicates (Section 4.5).

4.1 Unifying approaches based on underspecified ser (1): prepositional nature

There is a first family of analyses that try to account for locative copular sentences by integrating them with other uses of the copula within a system that adopts one single aspectual distinction that is based in the IL/SL or the imperfective/perfective dichotomy. Two works that, from different perspectives, fall into this class are Brucart (2010, 2012 and Zagona (2012).

The two works share the crucial assumption that the copula ser is the underspecified copula, which emerges when some additional information is missing or when that additional information has been licensed by some other element, typically an internal property of the predicate or subject.

Moreover, their analyses relate estar to some prepositional content. In both Brucart and Zagona, but with different perspectives, estar is marked by a prepositional feature that needs to be licensed by material in the copula, following initial intuitions of Benveniste (1966) that treat some more complex light verbs as manifestations of a default copulative verb combined with a preposition.

Brucart (2012) proposes to reinterpret the traditional IL/SL dichotomy in a locative framework by assimilating it to the central coincidence versus terminal coincidence contrast in the prepositional domain (Hale 1986; Hale and Keyser 2002). This way, individual-level predicates would be characterized by central coincidence relations, and stage-level predicates would correspond to terminal coincidence relations, which are also the ones used to express paths of motion. Following Gallego and Uriagereka (2016), Brucart proposes that estar is the copula that licenses a terminal coincidence relation, and is therefore introduced when the complement of the copula contains such preposition (54). Ser is unmarked with respect to the coincidence relation and therefore emerges whenever the terminal coincidence relation is not present or has been licensed by another element, which is the crucial property in the context of locative copular structures.

| [vP estar [RP … RT …]] |

| Luis | está | cansado. |

| Luis | isestar | tired |

| El | coche | está | en | el | garaje. |

| the | car | isestar | in | the | garage |

| [vP ser [RP … RC …]] |

| Luis | es | honesto. |

| Luis | isser | honest |

| La | fiesta | es | en | el | garaje. |

| the | party | isser | in | the | garage |

The configuration illustrated in (54a) corresponds to the combination of estar with a stage-level adjective. The structure includes a terminal coincidence preposition contained in the complement of estar, where the assumption is that a predication structure marked as terminal coincidence is projected above the predicate. This terminal coincidence predication is licensed by the copula estar, which contains an ad hoc feature to license this type of relation. Brucart, furthermore, proposes that all locations contain a terminal coincidence preposition. When the located entity is a physical object, the estar copula has to be introduced in order to license the terminal coincidence relation.

The use of ser with event subjects and with path subjects emerges because in those configurations, even though the locative structure introduces a terminal coincidence relation, the subject that is located in the prepositional structure is able to license the terminal coincidence relation before the copula is introduced (2012: 18).

| [vP ser [RP [DPRT] RT …]] |

| El | concierto | es | a | las | tres. |

| the | concert | isser | at | the | three |

| ‘The concert is at three o’clock.’ | |||||

| La | parada | de | taxis | es | por | allí. |

| the | stop | of | taxis | isser | over | there |

| ‘The taxi stand is that way’ | ||||||

For (56b), Brucart’s proposal is that the event noun in the subject position is initially introduced as the specifier of the terminal coincidence relation. This subject, denoting an event, contains a feature RT that licenses the locative relation. This makes it unnecessary to introduce estar to license this feature. Consequently, ser is introduced as a default copula. Similarly, in (56c), the subject is interpreted as a path and therefore also contains a feature RT, which again licenses the locative relation without estar. In this spatial theory of aspect, then, terminal coincidence relations identify with paths of movement, and events are defined as containing a path that is mapped as the progression of the event itself.

Brucart’s account has several shortcomings. We have already argued in Section 3.1 that path copular sentences are in fact possible without any type of relevant path interpretation. One could also raise questions about the syntactic locality of the relation that allows a DP subject to license the RT feature of the prepositional structure: presumably, event nouns, which are projections headed by determiners and quantifiers, would carry the information about their eventive nature in the lexical N layer, that is, this information would be embedded within a complex constituent in a specifier position, which is a configuration that has been treated as a syntactic island in many approaches (cf. Uriagereka 1992, for instance).

However, perhaps the main problem of Brucart’s analysis is to know the nature of this RT feature, and how its content maps onto identifiable and recognizable properties of the structures involved. It is crucial in Brucart’s account that all kinds of locative relations are defined by the feature RT even though they seem to be basically stative, while at the same time, the feature RT must be contained in event nouns but not in other nominals with temporal properties, such as state nouns. Remember from Section 2 that state nouns are also located with estar, which means, for Brucart’s approach, that they cannot contain the feature RT. It is less than optimal that RT is a property that needs to identify all locative structures, but at the same time, it is severely restricted in the nominal realm to only event nouns and nouns interpreted as paths.

Zagona’s (2012) approach shares with Brucart’s the intuition that the copula ser is a default element, and in her approach ser inherits or projects whatever aspectual information is contained in its complement. The analysis proposes that the range of complements that estar can select is determined by a formal feature [uP] estar has, and forces it to combine with a prepositional structure.

| estar: [ v [uP] … ] |

Ser would then be introduced as a default option. Zagona (2012: 305) assumes a relational theory of aspect and tense (Klein 1994) where, categorially and configurationally, aspectual relations are expressed through prepositional structures, and proposes that estar has a unified selectional capacity, selecting an abstract aspectual P – for instance, when used as an auxiliary in the progressive (58) – or a locative P, which explains the extended use of estar in locative contexts even when the interpretation is not an SL one.

| Juan | está | comiendo. |

| Juan | isestar | eating |

In terms of the nature of [uP], Zagona (2012) states that estar only selects for (stative) prepositions expressing a single location. Complex prepositions that include a path or a direction are not compatible with estar. This is why, Zagona argues, (59a) is grammatical, while (59b) is not: in her approach, a is a path preposition equivalent to ‘to’, and estar forces the path prepositions to be absent from the structure.

| Juan | está | en | casa. |

| Juan | isestar | in | home |

| ‘Juan is at home.’ | |||

| *Juan | está | a | casa. |

| Juan | isestar | to | home |

| ‘Juan is to home.’ | |||

In (59b), the [uP] feature of estar cannot be checked by a. According to Zagona (2012), this also explains why estar is ungrammatical with PPs that locate events (60): like in Brucart’s analysis, the eventive nouns contain a feature equivalent to a path preposition, and this feature is incompatible with licensing the [uP] feature of estar.

| La | reunión | {es/ | *está} | a | las | ocho. |

| the | meeting | isser/ | isestar | at | the | eight |

| ‘The meeting is at eight o’clock.’ | ||||||

Along the same lines, Zagona (2012) argues that the participial phrases in (61a) and (61b) differ in structure in a manner analogous to the location versus directional PP sentences discussed above, with eventive readings having a path preposition and stative readings having a place preposition and no path preposition. Since eventive passives contain a path, only ser can be chosen as an auxiliary verb.

| Los | exámenes | serán | corregidos | mañana. |

| the | exams | will.beser | marked | tomorrow |

| Los | exámenes | estarán | corregidos | mañana. |

| the | exams | will.beestar | marked | tomorrow |

Zagona’s analysis faces a crucial problem, similar to Brucart’s, with respect to the configurational relation where the path preposition interferes with the presence of estar. In fact, for Zagona (2012) it should be crucial that path prepositions are ungrammatical with estar complements, but we already saw (Section 3.1) that this is far from being evident, and in fact prepositions that normally denote paths give a Cresswellian End-of-journey reading with estar. This is in principle problematic for her analysis, as she would need to derive the semantic interpretation involving a location at the end of a path from a structure that in theory should not contain a path structure. Of course, Zagona (2012) could argue with Svenonius (2010) that the Cresswellian location reading is caused when the path preposition is embedded under a locative preposition (62a), and that in such context the path preposition does not block the presence of estar because it is embedded under a more complex constituent. However, if (62a) saves the derivation, it is unclear why the presence of a (temporal) path in event nouns would be incompatible with estar, as presumably that feature, contained in the lexical layer of the nominal constituent, would be embedded under determiners, quantifiers, and potentially significant chunks of functional structure (62b).

| [Ploc | … [Ppath …]] |

| [DP/QP | … [NPPpath …]] |

Finally, a problem of Zagona’s analysis that Brucart’s does not have relates to the default presence of ser. Note that in Brucart (2012), ser is the default because it does not license any other structure; if the structure that the copula combines with needs to be licensed, estar is introduced. In contrast, in Zagona (2012), ser is the default because it does not need to be licensed by another structure; the structure below the copula does not need to be licensed by estar in any case. In practice, this means that in Zagona’s analysis ser could combine with locative structures in any case, and thus that there is no direct way to block (63).

| *El | libro | es | en | la | mesa. |

| the | book | isser | on | the | table |

| Intended: ‘The book is on the table’ | |||||

Zagona acknowledges this problem and offers two preliminary suggestions, one of which is that the structure of the locative copula might be different from the one used otherwise, defining estar as the main locative copula. The second possibility is that ser, being the default, can be introduced when no more specific element (in this case, estar) is introduced, but note that in her analysis nothing of the PP structure calls for the presence of estar – it is the opposite, estar calls for the prepositional structure.

4.2 Unifying analyses based on underspecified ser (2): anchoring to an external situation or contextual parameter

There are also analyses that argue that ser lacks a specification that estar contains, but do not play around with prepositional contents. Here we will highlight two works, one that proposes that estar spatiotemporally anchors the predication to a reference situation (Escandell 2018), and one that uses the notion of contextual boundedness (Sánchez Alonso 2018).

The starting point of Escandell (2018) is that, within the domain of adjectival predicates, estar introduces the presupposition that there should be a relevant and specific situation that the predication relates with; in contrast, the function of ser is only to support the predicative relation. Adopting the notation in Maienborn (2005), Escandell (2018; see also Arche 2006; Escandell and Leonetti 2002) adopts the entry in (64b) for estar, where, in contrast to ser, estar introduces an abstract relation A between the predication e and an external situation s e .

| ser: λPλxλe [P(x)≈e] |

| estar: λPλxλe ∃se [[P(x) ≈e] & [A(e,se)]] |

When estar combines with a stage-level predicate, which in itself predicates from spatiotemporal stages or slices of the individual, there is a complete matching in features. When, on the other hand, the predicate is the individual level, there is a mismatch in features that is resolved by the meaning of estar imposing a coerced interpretation of the predicate forcing it to adopt a stage-level-like interpretation. The lexical properties of the adjective do not get altered, and the combination between estar and the adjective is a case of semantic composition where the copula imposes its interpretation. This makes it possible to explain so-called evidential uses of estar (Mangialavori 2013), where estar does not impose the reading that the properties are temporally bound when exhibited by the subject, or that there is any comparison between stages of the individual, but rather that the speaker commits herself to the belief that the property is truthfully predicated from the subject and that she has first-hand experience of that property (Escandell 2018: 79). In (65), the speaker signals that she has tasted the paella and has concluded, in this first-hand experience, that is exquisite.

| Esta | paella | está | exquisita. |

| this | paella | isestar | exquisite |

It is difficult, from our perspective, to understand exactly how this account can cover the location of events and the path of copular sentences that have been described above. The use of estar in the location of individuals, states, properties and so on might be included in the analysis if, along Brucart (2012), one proposes that any location act is in fact an act that requires to take as a point of reference an external entity, defining as ‘external’ the reference point employed to locate the subject. However, the question that would emerge is what makes that reference point different when the located entity is an event: would that reference point, then, be internal to the situation and not external? The approach might be able to make a claim along these lines if it accepts the core claims of Leonetti (1994) (see Section 4.5 below), where the temporal and locative dimensions are inherent properties of events that are not predicated from them. If it is possible to extend the event account to path copular sentences, this approach might be successful in accommodating also these facts, but we believe that it is fair to say that the approach has not developed an explicit account of these cases yet.

Another work that follows the same spirit, where estar relates the predication to some external parameters is Sánchez Alonso (2018). Also inspired by Maienborn’s (2005) presuppositional account, Sánchez Alonso proposes that estar, as the marked copulative verb, introduces a boundedness-presupposition. Following Maienborn (2005), ser signals that the circumstance of evaluation i is not the minimal verifying circumstance: in other words, it signals that when the parametric properties of the circumstances of evaluation change – time, space, degree expectation, etc.– the predication with ser continues to be true. In contrast, estar signals that the truth of the evaluation depends on a changeable contextual parameter so that the claim made is boundedly true with respect to one of the contextually determined parameters (Sánchez Alonso 2018: 92): that is, for instance, how she captures that Juan está guapo ‘Juan isestar handsome’ does not allow us to guarantee that Juan is handsome if the contextual temporal value changes. This boundedness to a contextual parameter can be temporal (referring to a time period, (66a)), spatial (66b) or signal-lowered contextual standards (66c) where a speaker had a previous expectation that is not confirmed (Sánchez Alonso 2018: 95). For instance, in a sentence such as Los zapatos me están anchos ‘The shoes areestar wide for me’, Sánchez Alonso (2018: 104) argues that estar is possible because context provides a certain degree of wideness that is exceeded by the shoes.

| Estás | muy | monja | últimamente. |

| areestar | very | nun-like | lately |

| Intended: ‘You act a lot like a nun lately.’ | |||

| En | el | kilómetro | tres | la | carretera | está | ancha. | [adapted] |

| in | the | kilometer | three | the | road | isestar | broad | |

| ‘The road is broad at km 3’ | ||||||||

| Vale, | ese | edificio | está | alto. |

| ok, | that | building | isestar | tall |

These results are very solid when adjectival attributes are considered (see, in fact, Sánchez Alonso et al. 2017, for experimental results), but they are difficult to extend to the location of events and path structures. The authors would need to argue that events lack any type of contextually-relevant parameters that could vary across time, space or degree, but (see below, Section 4.4) there are clear cases where events involve change across degree values. In this case, for us, the problem is that it becomes very difficult to interpret in which sense a sentence like (65), which is normally taken to be an IL location, involves some sort of contextually determined parameter that makes the sentence boundedly true.

| España | está | en | Europa. |

| Spain | isestar | in | Europe |

Sánchez Alonso (2018: 96) needs to say that in such cases there is a neutral reading of the verb estar, which follows from the absence of a difference between the expected (spatial) value p and its value in the context of evaluation. It is unclear to us, however, why Spanish would not simply use ser in such cases where using the stronger estar has no effect. Sánchez Alonso’s (2018: 112) approach is extended for locative cases so that what is contextually bound in sentences like (65) is the world parameter, that is, the speaker compares to all other worlds which are identical in any property but the location of the subject, which would take us to the metaphysical question of whether the speaker who says (65) automatically entertains the possibility that Spain might have been on any other continent. We do not discard that such examples can be included in a further extension of the approach, but it is fair to conclude that this integration has not been performed yet.

Finally, Sánchez Alonso (2018) addresses the case of path copular sentences, which she treats as a subcase of the location of events – a position that we have independently adopted in this article. The so-called path copular sentences are, in fact, sentences that locate an entity where an event will take place, for instance, an exiting event in (66).

| ¿Dónde | es | la | salida? |

| where | isser | the | exit? |

In her proposal, what is crucial in (66) is that the exit is not at-issue content (Simons et al. 2017), because the content of la salida is presupposed to be known on the common ground. This means that there cannot be falsifying circumstances: the addressee is assumed to know the existence of the exit, and the question is not about the location of that exit, but about how one can get out of the building (Sánchez Alonso 2018: 116). As there can be several ways of exiting the building, one cannot assume that the answer would be the only one that maximally satisfies the circumstances of evaluation, and as such estar cannot be used in this context. This is, however, more complex when the verb appears outside of a question, and a speaker answers something like (67), where it is explicitly stated that there is only one way to exit the building. Ser can still be used in this context.

| La | única | salida | es | en | el | segundo | piso. |

| the | only | exit | isser | in | the | second | floor |

This is an interesting approach that gives an answer to many of the puzzles that other theories cannot cover, and at least makes an explicit proposal about how it can be extended to the uses of ser with events and paths, which are assumed also to connect to events. However, this is done at the cost of making some potentially problematic assumptions about the intention of the speaker when stating (65) or (66): one has to assume in the first case that the speaker always entertains the possibility that an object could be located in some other place, and in the second case one has to assume that the subject is never at-issue content and other alternatives to perform the event are present.

4.3 Unifying analysis with non-default ser (1): IL predicates, events and temporal intervals

The previous approaches discussed share with many other analyses of the copula the assumption that ser is the default element, and estar is the only one that specifies its selectional restrictions. We start here with an overview of theories that treat ser as equally specified as estar: the two copulas are associated with a contrasting pair of elements, time intervals or degree objects. These approaches avoid overgenerating structures, as they block that ser combines with arguments that in principle must combine with estar. In contrast, they face the problem of how they can group together IL predicates and events to the exclusion of SL predicates, which is empirically required by the distribution of the copulas. Here, we will divide these theories into three main approaches: one where the distinction is based on the nature of the temporal objects that each copula selects (Section 4.3), one where the distinction has to do with the class of comparison or the scale associated with the adjective (Section 4.4), and one based in the more standard IL versus SL distinction (Section 4.5), but attempting to integrate it with locative copular sentences.

To the best of our knowledge, the best example of the first type of analysis is García-Pardo and Menon (2020). These authors propose that the contrast between ser and estar has as its origin the nature of the time arguments of the predicates that are selected by each one of the copulas. The specification of each copula is equally definite: ser combines with predicates whose time argument denotes an interval, irrespective of whether that interval corresponds to an event or a state. In contrast, estar is selected when the time argument associated with the predicate denotes a point in time, that is, a nonextended temporal object (cf. Piñón 1997 for a substantiation of the ontological assumptions behind this, with boundaries and bodies that combine to produce full-fledged temporal objects).

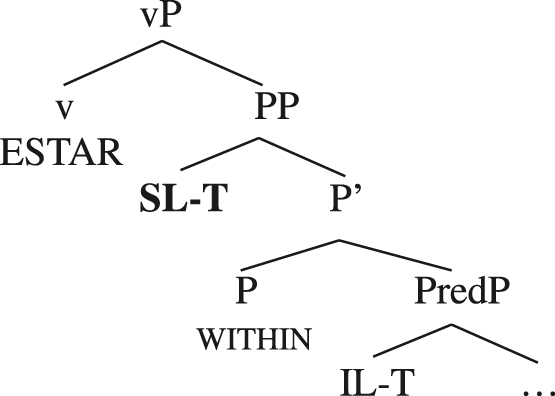

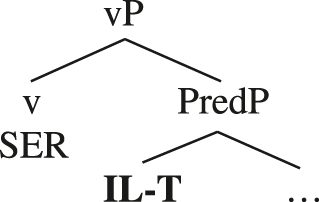

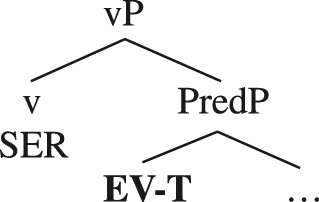

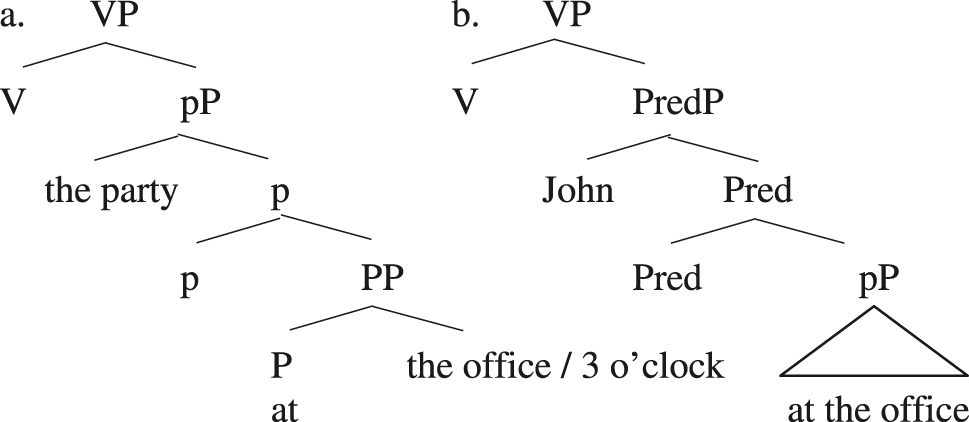

Even if both ser and estar have equally definite selectional restrictions, in line with other authors Fábregas (2012), Zagona (2012), and García-Pardo and Menon (2020) propose that SL predicates are derived from IL predicates. As illustrated in (68), stage-level predicates contain in their structure individual-level predicates. Individual-level predicates consist of a simple predicational structure with only one temporal argument (IL-T). The stage level predicate builds, on top of the predication, a relational PP structure that carries a prepositional head with a WITHIN meaning – roughly comparable to Brucart’s central coincidence relation – which introduces a second temporal argument. The SL-T argument is a point in time (Stage-Level Time) which is located by the P WITHIN as being part of the interval denoted by the IL-T (Individual-Level Time) introduced by Pred.

|

IL predicates only have a predicational structure marked with an IL-T, which denotes the whole interval in which the individual manifests a given property (69). Importantly, both SL and IL predicates are different from eventive predicates, which only have an EV-T argument (Event Time) that denotes the whole interval in which the event holds – that is, like IL predicates, the temporal argument of events denotes an interval in (70).

|

|

As can be seen in (69)–(70), in contrast to (68) the copula emerges as ser. The reason why, according to these authors, is that ser picks time intervals – and it does not care if these time intervals are stative (69) or eventive, as in (70) – whereas estar picks moments in time, i.e. instants (68). This unifying approach splits the domain of temporal objects into two parts, equally positively defined. Its main problem is, however, how to characterize in a unified way the type of temporal object that estar selects. There is no clear evidence that estar chooses instants; prima facie, it is rather the opposite. Note, to begin with, that most estar predicates have a duration that in fact can be explicitly marked with a phrase involving desde ‘since’ or durante ‘for’, which denotes that the situation described by the predicate holds at any single temporal point in the interval defined by the modifier. This is the case in adjectival copulative sentences (71a), locative sentences (71b), and passives (71c).

| Eva | está | enferma | desde | ayer. |

| Eva | isestar | sick | since | yesterday |

| Juan | estuvo | en | la | oficina | (durante) | varias | horas. |

| Juan | wasestar | in | the | office | for | several | hours |

| El | coche | está | reparado | desde | ayer. |

| the | car | isestar | repaired | since | yesterday |

At the same time, it is not clear that ser always picks intervals; according to the standard characterization of achievements since Vendler (1967), achievements express events that lack a temporal extension. At least initially, one should accordingly expect that event nominals corresponding to achievements (72a) or the eventive passive of achievements (72b) should combine with estar, not with ser, but that expectation goes against the attested facts.

| {Su | llegada/ | su | desaparición} | {fue/ | *estuvo} | a | las | tres. |

| her | arrival/ | his | disappearance | wasser/ | wasestar | at | the | three |

| ‘Her arrival/His disappearance took place at three o’clock.’ | ||||||||

| El | cadáver | {fue/ | #estuvo} | encontrado | a | las | 3:05 | de | la | mañana. |

| the | corpse | wasser/ | wasestar | discovered | at | the | 3.05 | of | the | morning |

| *El | cadáver | fue | encontrado | durante | varias | horas. |

| the | corpse | wasser | found | for | several | hours |

Yet, perhaps the strongest problem of this approach is that, as we have repeatedly observed, it is not true that any locative copular sentence with estar is an SL predicate. Sentences like (73) seem to behave as IL predicates, and in fact intuitively express situations that denote intervals and not points included within an internal, but still take estar. Like Brucart’s (2012) problem that he has to consider any location an SL location, this approach would have to treat any location (not involving an event) as an SL location, against facts such as (73b).

| Barcelona | está | en | el | Mediterráneo. |

| Barcelona | isestar | in | the | Mediterranean |

| *Siempre | que | Barcelona | está | en | el | Mediterráneo, | vamos |

| always | that | Barcelona | isestar | in | the | Mediterranean, | we.go |

| a | la | playa. | |||||

| to | the | beach | |||||

| Intended: ‘Whenever Barcelona is in the Mediterranean, we go to the beach.’ | |||||||

4.4 Unifying analysis with non-default ser (2): scales and comparison classes determine the distribution

In a series of works, Gumiel-Molina and Pérez-Jiménez (2012) and Gumiel-Molina et al. (2015, 2020: Ch. 5) advocate for the idea that the degree properties of the predicate underlie the distribution of the two copulas. These authors have modified their proposal across time: in their (2012) work, inspired by Husband (2010), their proposal was that adjectives whose internal scales are open act as homogeneous properties, while those that have closed scales behave as quantized predicates. Estar would signal the presence of a quantized predicate, that is, a predicate with a closed scale. In (2015) and (2020: Ch. 5), however, their claim – still concentrating on the degree structure of the adjective – is that what is crucial is not the scalar structure of the adjective per se, but the distinction between relative and absolute adjectives reflected on the type of class of comparison that their DegP head introduces as a second argument. The reason is that they find that some adjectives with a closed scale (74) (cf. the modifier completamente ‘completely’, restricted to closed scales; Kennedy and McNally 2005) can combine with ser (Gumiel-Molina et al. 2015: 959).

| La | cortina | {es/ | está} | completamente | transparente. |

| the | curtain | isser/ | isestar | completely | transparent |

On the reasonable assumption that the scalar properties of an adjective are lexically determined, they modify the analysis so that the distinction is defined on the functional structure that dominates the adjective, specifically depending on a degree head pos defined as (75) (Gumiel-Molina et al. 2015: 982).

| [[ Deg pos]] = λgλPλx.g(x) ≥ M(g)(P) |