Abstract

This article addresses the hitherto neglected topic of the Korean Nominative Object Construction (NOC) within the Cognitive Grammar (CG) framework. In the NOC, schematically illustrated as [N-NOM N-NOM PSYCH-PRED], the second NP behaves like a direct object. While the construction has puzzled many researchers in different languages, and a sizable amount of research exists, relatively little attention has been paid to Korean. It is worth noting that the findings made in the extant generative-linguistic research – including the research on Japanese, which exhibits significant typological similarities to Korean – are not sufficient to account for the Korean data. After identifying the properties of the Korean NOC, we demonstrate that the NOC merely reflects how the experiencer conceptualizes the stimulus that exists in a certain domain of mental experience within her mind. This internal representation of the stimulus is marked nominative by being the sole participant in the relationship profiled by the psychological verb at the lower level of organization. At the higher level of organization, the first nominal is the primary participant as an experiencer, thereby receiving nominative case as well. Our analysis is extended to the desiderative construction, which exhibits similar patterns to the PSYCH-PRED NOC but allows alternation of case in the second nominal between nominative and accusative marking. The case alternation is motivated by two different types of construals of the same conceptual base. The nominative marking arises when the embedded transitive relationship is backgrounded, whereas the accusative marking becomes available when the profile is given to the transitive relationship. We demonstrate that the source of the case alternation lies in the profile, rejecting the dichotomous division of the construction based on its mono- or bi-clausal properties.

1 Introduction[1]

This article aims to develop a Cognitive Grammar-based analysis of the Nominative Object Construction (NOC) in Korean. As the name indicates, the NOC is a construction in which the object nominal – the second nominal – is marked nominative, as shown in (1). The first nominal usually bears the nominative marker, which can alternate with the topic marker. While the NOC is most natural when the first nominal is the speaker as in (1a), a third-person subject is permitted, as in (1b). Note, however, that (1b) has a different interpretation than (1a); it involves the speaker’s assessment of the described situation, as indicated by the translation. Korean does not have an obligatory marking of evidentiality, and the speaker’s assessment is not coded morpho-syntactically in the NOC.[2] Throughout this article, for the NOC with the first-person subject, we add the expression I feel like within parentheses to show that this is an inferred but not linguistically encoded portion.

| a.[3] | nay-ka/na-nun | kangaci-ka | coh-ta. |

| I-NOM/I-TOP | puppy-NOM | like-DECL | |

| ‘I like puppies./As for myself, I like puppies.’ | |||

| b. | Gio-ka | kangaci-ka | coh-ta. |

| G-NOM | puppy-NOM | like-DECL | |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio likes puppies. | |||

Adopting Kumashiro’s (2016) analysis of the adjectival-experiencer construction in Japanese, the gist of our proposal is as follows: the second nominal in (1) gives rise to the internal representation of the stimulus – kagaci ‘puppy’ – that exists in a certain domain of mental experience within the experiencer. This internal representation of the stimulus is marked nominative by being the sole participant in the relationship profiled by the verb coh-ta ‘like’ at the lower level of organization.[4] At the higher level of organization, the first nominal is the primary participant as an experiencer, thereby receiving a nominative marking as well. Our proposal then is extended to the more commonly discussed construction, i.e., the desiderative construction in Korean, as shown in (2).

| nay-ka | kwail-i | mek-ko | siph-ta. |

| I-NOM | fruit-NOM | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘I want to eat fruits.’ | |||

In short, we demonstrate that double nominative marking in the NOC is ascribed to the internal nature of experience involved, causing a dual conceptualization focused on the stimulus, but not excluding the experiencer.[5]

It is well-known that Korean permits two or more nominative-marked nominals in a single sentence, as shown in (3a)–(3c).[6] These types of examples, often dubbed double or multiple nominative constructions, have drawn significant attention from various theoretical perspectives for the past several decades. In teasing out the grammatical properties of these constructions, most scholars (Kim 2016; O’Grady 1991; Yoon 2007, 2009) identify the second nominals as the grammatical subjects.

| Gio-ka | apeci-ka | pwuca-i-si-ta. |

| G-NOM | father-NOM | rich-COP-HON-DECL |

| ‘Gio’s father is rich.’ | ||

| Gio-ka | nwun-i | khu-ta. |

| G-NOM | eye-NOM | big-DECL |

| ‘Gio has big eyes.’ | ||

| yelum-i | sakwa-ka | mas-iss-ta. |

| summer-NOM | apple-NOM | taste-PST-DECL |

| ‘In the summer, apples taste good.’ | ||

Many researchers (Jung 2011; Kim and Maling 1998; Maling et al. 2001; among others) have dealt with a specific type of the NOC, as in (2), within the context of case alternation; the second nominal, kwail-i ‘fruit-NOM’, may alternate with kwail-ul ‘fruit-ACC’.[7] However, the nominative object itself is not those researchers’ primary focus; therefore, examples like (1) have drawn less attention from these scholars.

The same type of construction is found in Japanese, and a sizable amount of research exists in the generative-linguistic literature with no consensus. While Saito (1982) proposes that the NOC is the major subject construction, Koizumi (2008) argues that nominative objects are authentic objects.[8] Takano (2003) argues that nominative objects in Japanese complex predicate constructions are proleptic objects, which are base-generated outside the embedded clauses and bind pronouns in the embedded clauses. Saito’s analysis is not tenable because the first nominal in the NOC does not exhibit the typical properties of major subjects. While Takano’s analysis provides valuable insight on the structure of the NOC with complex predicates, it is challenging to apply his analysis to (1a) and (1b), which do not contain complex predicates nor exhibit a bi-clausal structure. Unlike these researchers, we believe exploring the conceptual motivation for the construction will enhance our understanding of the NOC and shed light on its nature.

In this article, we first identify the properties of the NOC and streamline the syntactic and semantic differences between the examples in (1) and (3). We then demonstrate that the second nominals in (1a–b) do not exhibit subject properties, which is similar to Koizumi’s (2008) observation of Japanese. There are two differences between Koizumi’s analysis and ours. Koizumi reaches the conclusion that second nominals shown in the Japanese examples comparable to (1) are genuine objects by demonstrating that these nominals lack subject properties. However, the objecthood tests Koizumi adopts are not applicable to Korean. Since a nominal being devoid of subject properties does not necessarily warrant its objecthood, we need more positive evidence for Korean. The second difference is our theoretical assumption. Koizumi’s analysis relies on the standard generative linguistic assumptions. By contrast, we show that the NOC needs to be understood by teasing out how an experiencer interacts with a stimulus and how the experiencer experiences the change of the internal state of mind by making mental contact with the state, which is the view proposed by Kumashiro (2016). One advantage of Kumashiro’s and our approach over Koizumi’s is that we do not need to propound any particular mechanism for nominative objects; the NOC simply reflects the internal nature of human experience. By identifying the conceptual process underlying the interaction between experiencer and stimulus, we believe we can not only explain why such a construction exists but can also reach a higher level of generalization concerning other similar constructions, such as the dative experiencer construction.[9]

As for the theoretical frameworks the previous proposals adopt, all researchers mentioned above – except for Kumashiro (2016) – work within the generative linguistics enterprise, where nominative case assignment is structurally determined and the conceptualizer’s construal process plays no role.[10] We start out from a very different assumption that case is meaningful by highlighting the cognitive conceptualization of events for linguistic processes, such as subject selection. The data we analyze in this article comes from two major sources: extant research and our native speakers’ intuition. For the examples where we believe the speakers’ judgment might vary, we conducted a short survey of 12 naive native speakers of Korean using a Likert scale of 1–6, where 6 indicates complete felicity. The examples with scores lower than an average of 2 are indicated with an asterisk. We treated the examples with an average score of 4.5 or higher as acceptable sentences. We used one or two question marks for the examples with average scores falling somewhere between 2 and 4.5.

The organization of this article is as follows. We introduce Kumashiro’s CG analysis of the Japanese adjectival-experiencer construction in Section 2, on which our analysis is based. Sections 3 through 5 discuss three fundamental properties of the NOC. These sections have a dual purpose. The first is to provide summaries of previous proposals, accompanied by our criticism if any. The second is to lay out our proposal in an informal way before we provide more technical CG analyses. The properties we discuss are [1] NOCs are sanctioned by stative predicates; [2] nominative objects, albeit marked nominative, do not exhibit typical subject properties but rather exhibit object properties, though partially; [3] nominative objects prefer a wide-scope interpretation. We then discuss the desiderative construction in more detail in Section 6. Our technical CG analyses are provided in Section 7. Section 8 is devoted to a critical review of two representative studies conducted within the generative linguistics framework. In this section, we demonstrate that the NOC is not the major subject construction, and the view of nominative objects as proleptic objects needs more careful assessment. Section 9 concludes this article by discussing the implications of our findings.

2 A cognitive grammar approach: Kumashiro (2016)

In Section 1, we briefly discussed several proposals based on generative linguistics. In this section, we provide a summary of Kumashiro’s (2016) CG-based analysis of the Japanese NOC upon which our technical analysis is based. It is necessary to discuss Kumashiro’s analysis before we present the descriptive properties of the NOC because our presentation in Sections 3 through 5 is accompanied by our informal CG analysis, which is comparable to Kumashiro’s (2016) analysis of Japanese. From a CG perspective, Kumashiro (2016) provides one of the most elegant analyses of the Japanese adjectival-experience construction. He states that the predicates used in this construction express three different types of mental experiences: sensations, emotions, and desires. He argues that these constructions exhibit the internal nature of the experience. When the subject is in third person as in (4), the adjectival-experiencer construction requires an inferential expression like rashii ‘to seem’. This is because the speaker cannot externally determine what is taking place inside the subject’s mind. By contrast, when the subject is first-person as in (5), no such expression is needed because the speaker can observe her own internal experience.

| Taroo-ga | hebi-ga | kowai | rashii (koto) |

| T-NOM | snake-NOM | scary | seem |

| ‘(that) Taro seems to feel scared of snakes.’ | |||

| watashi-ga | hebi-ga | kowai (koto) |

| I-NOM | snake-NOM | scary |

| ‘(that) I feel scared of snakes.’ | ||

Kumashiro then proposes the universal base for experience in Figure 1. The figure indicates that the stimulus sends some stimulation, and the experiencer – the larger circle on the right side – undergoes an internal change of state. The state is represented by a small circle within the large one because it is an internal representation of the stimulus. The state exists in a certain domain of mental experience, such as fear or pain, within the experiencer. The experiencer experiences the internal state by making mental contact with it. As a reaction to the stimulation, the experiencer may make a response. The correspondence relationship held between the stimulus and its internal representation indicates that both circles represent the same entity, which is notated by the dotted line.

Universal base for experience, reproduced from Kumashiro (2016: 210).

Based on the schematic description of experience in Figure 1, Kumashiro (2016) proposes the semantic structure for the adjectival-experiencer construction in Japanese seen in Figure 2. The figure is slightly modified to account for the NOC. In this figure, the largest circle represents the experiencer in the NOC, and the innermost circle represents the nominative object. C and C′ stand for conceptualizer and surrogate conceptualizer, respectively. The surrogate conceptualizer is identical to the experiencer for an NOC with a first-person subject. While the conceptualizer imposes a scope, shown as a large square labeled CS, the surrogate conceptualizer also imposes its own scope which is indicated by SS within the small rectangle. The two scopes are identical for an NOC with the first-person subject. For a third-person NOC, CS and SS are not identical, and neither are C and C´.

NOC depicted, adapted from Kumashiro (2016: 213).

Our view is parallel to Kumashiro’s, and how the Korean NOC is analyzed with Figure 2 is presented in Section 7.

3 Mental states

As illustrated with the examples in (3), the predicates that sanction the NOC denote stativity, particularly mental states.[11] In this section, we discuss two types of predicates: psychological predicates and the desiderative verb siph-ta.

3.1 Psychological predicates

The first type concerns psychological predicates that express a mental state. Korean psychological predicates are provided in (6), and (7) illustrates sentences with some of these predicates.[12]

| Korean psychological predicates |

| uysimccek- ‘be suspicious of’, mip- ‘hate’, pankap- ‘glad to see’, siwenchiahn- |

| ‘unsatisfactory’, silh- ‘dislike’, coh- ‘like’, anikkop- ‘feel resentful’, aswuip- ‘feel bad’, anssulep- ‘feel sorry’, anthakkap- ‘feel sorry’, mwusep- ‘be scared’, kulip- ‘miss’, kayep-ta ‘feel pity’, pwulep- ‘be jealous’, twulyep- ‘be scared’, pwukkulep- ‘be shameful’ |

| nay-ka | ku | salam-i | uysimccek-ta. |

| I-NOM | that | person-NOM | suspicious-DECL |

| ‘I am suspicious of that person.’ | |||

| na-nun | yocum | kohyang-i | nemwu | kuliw-ta. |

| I-TOP | recently | hometown-NOM | very | miss-DECL |

| ‘I miss my hometown very much recently.’ | ||||

| na-nun | swici-ahn-ko | yelsimhi | kongpwu-ha-nun | Mia-ka | ||

| I-TOP | rest-NEG-COMP | hard | study-do-ADN | M-NOM | ||

| nemwu | anssulew-ta. | |||||

| very | feel.sorry-DECL | |||||

| ‘I feel sorry about Mia who studies hard without stopping.’ | ||||||

In many languages, including English (Huddleston and Pullum 2002), Russian (Croft 1993), Lakhota (Rood and Taylor 1976), and Classical Nahuatl (Andrews 1975), predicates of psychological state fall into two main classes according to the way the thematic roles align with subject (S) and object (O). In the English examples (8a) and (9a), for instance, the experiencer is aligned with the subject, while the stimulus is aligned with the object. (8b) and (9b) illustrate the opposite case.

| a. | We enjoyed the show. | (S: Experiencer, O: Stimulus) |

| b. | The show delighted us. | (S: Stimulus, O: Experiencer) |

| (Huddleston and Pullum 2002: 234) | ||

| a. | We deplored their decision. | (S: Experiencer, O: Stimulus) |

| b. | Their decision appalled us. | (S: Stimulus, O: Experiencer) |

| (Huddleston and Pullum 2002: 234) | ||

Korean does not have experiencer-object verbs; instead, causative constructions are used to express a similar situation, as in (10).

| nay-ka | Mia-lul | sulphu-key | hay-ss-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-ACC | sad-CAUS | do-PST-DECL |

| ‘I made Mia sad.’ | |||

The stimulus may also appear in the subject position through passivization, as shown in (11).

| nay-ka | Mia-ttaymwuney | sulphe-ci-ess-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-due.to | sad-PASS-PST-DECL |

| ‘I felt sad because of Mia.’ | ||

It is worth noting that the Korean NOC is neither a passive nor a causative construction. The obvious reason the NOC is not causative is the unacceptability of (12), where the putative object cannot be marked nominative. Neither does the periphrastic causative construction, shown in (13), allow a nominative-marked object.

| *nay-ka | Mia-ka | sulphu-key | hay-ss-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-NOM | sad-CAUS | do-PST-DECL |

| Intended: ‘I made Mia sad.’ | |||

| *nay-ka | Mia-ka | sulphe-ci-key | hay-ss-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-NOM | sad-become-CAUS | do-PST-DECL |

| Intended: ‘I made Mia sad.’ | |||

The NOC neither permits passive morphology nor is compatible with passive predicates, as in (14a) and (14b), respectively; Mia cannot be marked nominative in the passive construction. One way to rescue (14a) and (14b) is to mark the second nominal with eykey ‘by’, as in (14c).

| *nay-ka | Mia-ka | silh-li-ess-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-NOM | dislike-PASS-PST-DECL |

| Intended: ‘I am disliked by Mia.’ | ||

| *nay-ka | Mia-ka | mac-ass-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-NOM | beaten-PST-DECL |

| Intended: ‘I was beaten by Mia.’ | ||

| nay-ka | Mia-eykey | mac-ass-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-by | beaten-PST-DECL |

| ‘I was beaten by Mia.’ | ||

Another noticeable difference between the NOC and the passive construction is the nature of their subjects. While the passive construction requires a theme subject, the NOC requires an experiencer subject. To demonstrate this difference, we need to identify which nominal is the subject in the construction. The subjecthood tests for the NOC will be discussed in more detail in Section 3, but let us briefly demonstrate an example of reflexive binding. The Korean reflexive, caki ‘self’, appears to prefer the subject as its antecedent. Note that only the experiencer nominal, Gio, can be the antecedent of the reflexive caki in (15a). The second nominal, Mia, which is a stimulus, cannot serve as the antecedent of caki, as shown in (15b).

| Gio i -ka | Mia j -ka | caki i -uy | hakkyo-eyse | ceyil | coh-ta. | |

| G-TOP | M-NOM | self-GEN | school-in | most | like-DECL | |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio likes Mia the most in her (Gio’s) school.’ | ||||||

| *Gio i -ka | Mia j -ka | caki j -uy | hakkyo-eyse | ceyil | coh-ta. |

| G-TOP | M-NOM | self-GEN | school-in | most | like-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio likes Mia the most in her (Mia’s) school.’ | |||||

If caki is replaced with a pronoun that does not have subject orientation, it can refer to either Gio or Mia, as in (16).

| Gio i -ka | Mia j -ka | kunye i/j -uy | hakkyo-eyse | ceyil | coh-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-NOM | she-GEN | school-in | most | like-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio likes Mia the most in her (Gio’s) school.’ | |||||

| ‘(I feel like) Gio likes Mia the most in her (Mia’s) school.’ | |||||

The passive construction shows a different behavior. Similar to the NOC, only the first nominal, Gio, can be the antecedent of caki in (17a); here, however, Gio is a theme subject, not an experiencer or an agent. (17b) is not felicitous because caki is bound by Mia.

| Gio i -ka | Mia j -eykey | caki i -uy | hakkyo-eyse | cha-i-ess-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-by | self-GEN | school-in | kick-PASS-PST-DECL |

| ‘Gio was kicked/dumped by Mia in her (Gio’s) school.’ | ||||

| *Gio i -ka | Mia j -eykey | caki j -uy | hakkyo-eyse | cha-i-ess-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-by | self-GEN | school-in | kick-PASS-PST-DECL |

| Intended: ‘Gio was kicked/dumped by Mia in her (Mia’s) school.’ | ||||

The examples above show that caki refers to experiencer subjects in the NOC, while it refers to theme subjects in passive sentences. In generative-linguistic analyses, a passive subject is a derived subject, and our data shows that derived subjects control the subject-oriented reflexives. In that type of approach, our observation may be interpreted as a claim that an experiencer subject with a psychological predicate is the underlying subject. While we do not subscribe to the derivational approach, and while the question of which subject is the underlying one is not relevant, the relationship between the generative linguistic notions of the derived and underlying subjects can be explained in our analysis. In accounting for the semantics of psychological verbs, Croft (1993) provides a valuable generalization, as in Figure 3. This figure illustrates that there are two processes involved in construing psychological predicates; the first involves the attention directed from the experiencer to the stimulus, and the second indicates that the stimulus causes the experiencer to enter into a certain mental state.

Two-way causal relation, adapted from Croft (1993: 64).

Based on this symmetric representation, Croft makes four predictions. The most relevant one to our current discussion is summarized in (18).

| There should exist languages in which mental state verbs more directly manifest the bidirectionality of the mental state causal structure: either experiencer and stimulus are case marked identically or one of the arguments is assigned a neutral case marking |

| (Croft 1993: 64–65). |

(18) is predicted because the experiencer and the stimulus exhibit a two-way relation in the causal structure described in Figure 3; they are both simultaneously the initiator and the endpoint. Korean is a language that supports this prediction. The stimulus subject pattern is not available with psychological verbs in Korean. Instead, the experiencer and the stimulus are marked with the same case. Reinterpreting Croft’s generalization in CG terms, we propose that both the experiencer and the stimulus are marked nominative because each of them marks the head of a profiled event-chain.[13]

How the linking is established between thematic roles and grammatical relations is a complex topic. Traditionally, the thematic role hierarchy is mapped isomorphically to the (underlying) grammatical relation hierarchy, and psychological predicates show some flexibility in this mapping. In this view, there is no direct correlation between case-marking and the argument structure of verbs, though some connections can be made, e.g., Burzio’s Generalization (Burzio 1987). From this perspective, Croft’s description in Figure 3 seems to be overly simplistic. However, case marking and grammatical relations do not need an intervening linking stage in many constructional approaches, including Croft’s. In CG as well, grammatical relations are determined solely based on the trajector/landmark alignment, where the subject is defined as the clausal trajector, while the objecthood is conferred on the secondary focal participant. That is, our approach does not assume any type of intermediate linking between case and grammatical relations.

3.2 The desiderative construction

The desiderative verb siph-ta also gives rise to the NOC, shown in (19); siph-ta exhibits properties of a psychological predicate because it also represents a mental state. Therefore, the situation described in (19) is stative. The difference between siph-ta and other psychological predicates stems from the former’s nature as an auxiliary verb. As an auxiliary verb, siph-ta requires a main verb.

| nay-ka | Mia-ka | po-ko | siph-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-NOM | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘I miss Mia.’ | |||

The siph-ta construction has been discussed by many scholars, particularly within the context of case alternation; the second nominal Mia in (19) may be marked accusative, resulting in (20).

| nay-ka | Mia-lul | po-ko | siph-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-ACC | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘I want to see Mia.’ | |||

We will revisit the issues concerning the siph-ta construction in Section 6, but first, we need to address one peculiar semantic property observed in (19) and (20) here. Some extant research, such as Jung (2011), often assumes that (19) and (20) are identical in their meanings. A closer examination, however, reveals that this is not the case. As the translations of (19) and (20) indicate, (19) expresses the speaker’s mental state of missing Mia, while (20) more prominently indicates that the speaker’s desire is associated with an episodic event. The same pattern is observed with a predicate with less idiomatic connotations, as shown in (21) and (22). While (21) denotes the speaker’s mental state of craving apples, (22) is about the speaker’s mental state of desiring the episodic event of eating an apple.

| nay-ka | sakwa-ka | mek-ko | siph-ta. |

| I-NOM | apple-NOM | eat-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘I crave apples.’ | |||

| nay-ka | sakwa-lul | mek-ko | siph-ta. |

| I-NOM | apple-ACC | eat-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘I want to eat an apple.’ | |||

The different semantic interpretations of (21) and (22) can be tested truth-conditionally. In (23), the first clause denotes the speaker’s general craving that is not anchored in a specific time. This craving can be overridden by one specific event anchored in the speech time, which is denoted by the second clause. (24) contrasts with (23) in that the first clause describes the speaker’s desire to eat apples in the speech time, which contradicts the situation described by the second clause.

| nay-ka | sakwa-ka | mek-ko | siph-untey, | cikum |

| I-NOM | apple-NOM | eat-COMP | desire-CONN | now |

| sakwa-lul | mek-ko | siph-ci | anh-ney | |

| apple-ACC | eat-COMP | desire-CONN | NEG-END | |

| ‘I generally craves apples, but I don’t want to eat apples now.’ | ||||

| ??nay-ka | sakwa-lul | mek-ko | siph-untey, | cikum | |

| I-NOM | apple-NOM | eat-COMP | desire-CONN | now | |

| sakwa-lul | mek-ko | siph-ci | anh-ney | ||

| apple-ACC | eat-COMP | desire-CONN | NEG-END | ||

| Intended: ‘I want to eat apples (now), but I don’t want to eat apples now.’ | |||||

Scholars such as Kim and Maling (1998) note the different semantic properties of examples like (21) and (22) and argue that the difference comes from the two distinct syntactic structures (21) and (22) manifest. Unlike Kim and Mailing, we demonstrate that the two different grammatical patterns are the realizations of two types of construals of the same conceptual content. We further show that though (21) and (22) involve the same type of complex predicate formation, they differ in their profiles. While (21) shows a construal identical to the other examples of the NOC we have discussed thus far, the profile is given to the embedded transitive relationship in (22). Case marking patterns in these examples then become merely symptomatic of two different types of construals the speaker chooses in interpreting a given situation. The details of the mechanism will be discussed in Sections 6 and 7.

3.3 A variation of the desiderative construction

The siph-ta construction discussed in Section 3.2 can be extended with the auxiliary verb ha- ‘do’, as shown in (25a). When it occurs, the second nominal cannot be marked nominative, as in (25b).

| Gio-ka | Mia-lul | po-ko | siph-e | hay-ss-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-ACC | see-COMP | desire-COMP | do-PST-DECL |

| ‘Gio wanted to see Mia.’ | ||||

| *Gio-ka | Mia-ka | po-ko | siph-e | hay-ss-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-NOM | see-COMP | desire-COMP | do-PST-DECL |

| Intended: ‘Gio wanted to see Mia.’ | ||||

Albeit superficially similar, (25a) is different from (22) concerning agentivity and stativity. While both (21) and (22) show a lesser degree of the subject’s volitional involvement in a situation, (25a) demonstrates a higher degree of volitionality. Note that it is widely accepted that volitional involvement is a prerequisite for agenthood (see Dowty 1991; Lehmann 1991; Van Valin and LaPolla 1997; Van Valin and Wilkins 1996; Primus 1999, 2002; among others). One test for agentivity is to check the acceptability of modifying an event with adverbs indicating volitionality (see Klein and Kutscher 2002; Roeper 1987; Talmy 1976; among others).

The application of the test to examples similar to (21), (22), and (25a) is shown in (26). (25a) is still acceptable with the volitional adverb uytocekulo, as shown in (26a). (26b) and (26c), which are different versions of (21) and (22) with adverbial modification and a different verb, are not felicitous. The test results show that (25a) exhibits a higher degree of agentivity than (21) and (22). Note that the meaning of po- ‘see’ shifts to become close to ‘meet’ in (26a), due to the existence of the adverb uytocekulo ‘intentionally’. The same type of meaning shift is not available for (26b) and (26c), which again shows that the siph-e ha-ta construction forces the reading of a complex event.[14]

| Gio-ka | Mia-lul | uytocekulo | po-ko | siph-e | hay-ss-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-ACC | intentionally | see-COMP | desire-COMP | do-PST-DECL |

| ‘Gio wanted to see/meet Mia intentionally.’ | |||||

| *Gio-ka | Mia-ka | uytocekulo | po-ko | siph-ta. |

| P-NOM | M-NOM | intentionally | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Gio misses Mia intentionally.’ | ||||

| *Gio-ka | Mia-lul | uytocekulo | po-ko | siph-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-ACC | intentionally | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Gio wants to see Mia intentionally.’ | ||||

The second difference concerns stativity. As described by Verhoeven (2010), a prototypical state involves no energy to go on or be kept going (also see Comrie 1976; Lehmann 1991; Van Valin and LaPolla 1997, among others). One test for stativity is incompatibility with a progressive form (see Van Valin and LaPolla 1997; Vendler 1967). The test results show that the internal structure of (27a) is non-stative, while the internal structures of both (27b) and (27c) involve stativity.

| Gio-ka | Mia-lul | po-ko | siph-e | ha-ko | iss-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-ACC | see-COMP | desire-COMP | do-COMP | PROG-DECL |

| ‘Gio is wanting to see/meet Mia intentionally.’ | |||||

| *Gio-ka | Mia-ka | po-ko | siph-ko | iss-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-NOM | see-COMP | desire-COMP | PROG-DECL |

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Gio is missing Mia.’ | ||||

| *Gio-ka | Mia-lul | po-ko | siph-ko | iss-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-ACC | see-COMP | desire-COMP | PROG-DECL |

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Gio is wanting to see Mia.’ | ||||

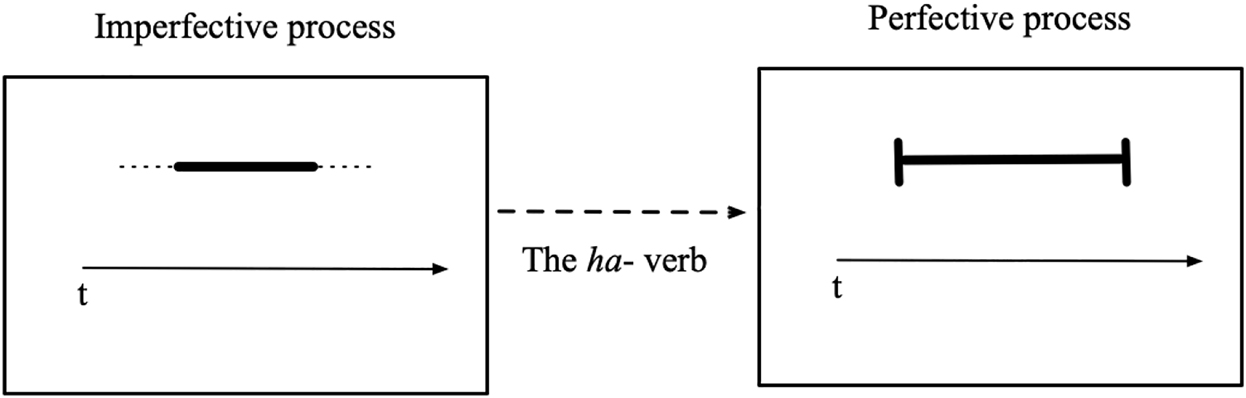

The tests demonstrate that the siph-ta construction is associated with non-agentivity and stativity, while the siph-e ha-ta construction involves agentivity and non-stativity. Since the only difference between the two constructions is the existence of the auxiliary verb ha-, it is reasonable to suggest that the function of ha- is to convert non-agentive states into agentive non-states. We propose that ha- converts an imperfective process into a perfective one, as sketched in Figure 4. In this figure, t refers to the conceived time, and the thick lines indicate the profiled portions of the process. The dotted lines in the left rectangle mean the process is unbounded, while boundedness is represented with two small vertical bars in the right rectangle.

The function of the ha- verb.

CG adopts a two-way distinction of the aspectual system: perfective and imperfective. Perfectives construe the profiled relationship as internally heterogeneous, whereas imperfectives construe it as homogeneous. While heterogeneous construals involve some type of change through time, homogeneous construals involve the continuation of a stable situation through time. In this view, earlier examples like (21) and (22) illustrate stable situations of indefinite duration, in the sense that the construal excludes the beginning and the end point from the general region of attention.

The major property of states is that they exist or obtain, as opposed to occurrences, which happen (Huddleston and Pullum 2002: 119). Due to this property, a relation involving only one participant is more common for stative construals, which is the case for (21). (22) is a deviation from this prototypical stative situation because the situation describes an episodic event. Nevertheless, it can still be construed statively. It is important to emphasize that the perfective/imperfective contrast is anything but a rigid specification. A similar situation is described in (28). Though the speaker did not continuously sleep for 20 min, the first conjunct I slept for 20 min does not contradict the second clause; this situation can be viewed as a stable situation, although it shows a certain degree of heterogeneity.

| I slept for 20 min, but I woke up five times to check the alarm clock. |

Example (22) shows a case of flexible categorization of perfectivity, whereas (21) and (25a) demonstrate typical situations for imperfective and perfective construals, respectively. This type of flexibility is not a unique consideration found only in CG or cognitive linguistics in general. While not endorsing CG rationales, Hopper and Thompson (1980), Dowty (1991), and Jacobsen (1992) argue that transitivity is a scalar notion. Proponents of this view treat transitive clauses as being more or less transitive, depending on a variety of semantic factors.

According to Jacobsen (1992: 124), a highly transitive clause is viewed as involving some change of the participants, while in transitive stative clauses “the situation expressed is viewed as constituting a property of the participant itself.” Some statives can be expressed either as intransitive or transitive. When they are realized as transitive, they may take an accusative-marked object if the object is construed as affected and specific.[15] The Korean siph-ta is one such stative predicate. Example (21) is used more naturally in the situation described in (29), in which the emphasis is on a general craving for apples. By contrast, (22) is much more natural in a situation described in (30), in which those specific apples may be affected because the speaker might purchase and eat them.

| I am craving apples these days, but I don’t have any specific kind in mind. |

| I want to eat the Honeycrisp apples displayed at the grocery store now. |

In this regard, the siph-e ha-ta construction contrasts with siph-ta in that siph-e ha-ta is construed as highly transitive, permitting only an accusative-marked object. The table in (31) summarizes our discussion on siph-ta and siph-e ha-ta. Note that we use stative tantamount to imperfective and non-stative (dynamic) to perfective. When a situation denoted by the siph-ta construction is construed as strongly imperfective, the object is marked nominative, which shows a lesser degree of transitivity. The same construction may be construed less imperfectively. While this construal still maintains stativity, the degree of transitivity is upgraded, thereby permitting an accusative-marked object. The siph-e ha-ta construction is always construed perfectively, making the choice of a nominative-marked object unviable.

Transitivity and (im)perfectivity

| Stative/Imperfective | Dynamic/Perfective | |

| Intransitive | X-NOM Y-NOM V-ko siph-ta | N/A |

| Transitive | X-NOM Y-ACC V-ko siph-ta | X-NOM Y-ACC V-ko siph-e ha-ta |

The table in (31) also shows that the situation denoted by the siph-ta construction is stative without respect to its transitivity. By contrast, the siph-e ha-ta construction is strongly associated with a perfective construal, made available by the auxiliary verb ha-ta.

4 Is the second nominative-marked NP a subject or object?

4.1 Subjecthood tests

There is no denying that a typical subject in Korean is marked nominative. However, the case marker itself does not determine subjecthood; there are many instances where the subject appears with non-nominative markers. One example is the dative subject, as shown in (33).

| apeci-eykey | ton-i | manh-usi-ta. |

| father-DAT | money-NOM | be.much-HON-DECL |

| ‘(My) father has a lot of money.’ | ||

The subject of (32) is the dative-marked nominal, apeci ‘father’, as opposed to the nominative-marked nominal, ton ‘money’. The subjecthood of apeci becomes apparent because of the honorific marker -(u)si-.[16] The inanimate entity ton ‘money’ cannot be honorified, and the only candidate for the honorification is apeci ‘father’ in (32), though it is marked dative.

We can apply the same test to the NOC to ascertain which nominative-marked nominal is a subject. When the first nominal is an entity to be honorified, the honorific marker, -(u)si-, may be affixed felicitously, as in (33). When first and the second nominals switch positions as in (34), the outcome is unacceptable. This test strongly suggests that the first nominal, not the second, is the subject of the NOC.

| apeci-ka | Gio-ka | philyoha-si-ta. |

| father-NOM | G-NOM | in.need.of-HON-DECL |

| ‘(My) father is in need of Gio.’ | ||

| *Gio-ka | apeci-ka | philyoha-si-ta. |

| G-NOM | father-NOM | in.need.of-HON-DECL |

| Intended: ‘Gio is in need of (my) father.’ | ||

That said, this test needs to be used with great caution. Honorification is a discourse phenomenon, and the agreement pattern often defies a grammatical relation. For example, if the honorific marker -(u)si- agrees with a subject, the inanimate entity, ton ‘money’, must be honorified in (35); this is not a tenable explanation. Instead, we might argue that (35) is felicitous owing to -(u)si-’s function as an addressee honorifier, which is the view supported by Lim (2000). According to him, -(u)si- agrees with an addressee that can be identified in a discourse context; -u(si)- agrees with the person who drives the BMW in (35).[17]

| (Situation: Looking at someone driving a BMW) | |

| ton-i | manh-usi-neyyo |

| money-NOM | be.much-HON-END |

| ‘(You) must be rich.’ | |

Without respect to the true function of -(u)si-, the test results provided thus far point to the fact that the nominative-marked NP does not exhibit any agreement relation with the honorific marker. We therefore can conclude that the second nominal in the NOC is devoid of this subject property.

The second well-attested diagnostic for subjecthood in Korean is caki ‘self’ binding, which we briefly discussed in Section 3.1: caki strongly prefers a grammatical subject as its antecedent. (36) shows that it cannot have the second nominal as its antecedent, which again demonstrates that the first nominal, not the second, exhibits a subject property.

| Gio-nun | Mia-ka | caki-uy | hakkyo-eyse | ceyil | mip-ta. |

| G-TOP | M-NOM | self-GEN | school-in | most | hate-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio hates Mia the most in her (Gio’s) school.’ | |||||

| ‘*(I feel like) Gio hates Mia the most in her (Mia’s) school.’ | |||||

The reflexive binding test also needs to be carefully applied. In a certain situation, caki may refer to the second nominal, as shown in (37a). If caki and the first nominal refer to the same entity, na-nun, the result is not acceptable, as seen in (37b). This is because as the third-person reflexive, caki cannot be bound by na-nun, thereby making (37b) unacceptable.[18]

| na-nun | Gio i -ka | caki i | tongney-eyse | ceyil | mip-ta. |

| I-TOP | G-NOM | self | neighborhood-at | most | hate-DECL |

| ‘I hate Gio the most out of her neighbors.’ | |||||

| *na j -nun | Gio-ka | caki j | tongney-eyse | ceyil | mip-ta. |

| I-TOP | G-NOM | self | neighborhood-at | most | hate-DECL |

| Intended: ‘I hate Gio the most out of my neighbors.’ | |||||

Though (37a) shows that the second nominal may bind the reflexive, its acceptability has an independent motivation. According to Kameyama (1984), a non-subject NP construed as a “perspective” can control the reflexive in Japanese. In (37a), Gio is construed as a person who suffers from the speaker hating her. Therefore, Gio is qualified as a “perspective” in this example.

The two subjecthood tests point to the suggestion that the second nominal in the NOC is not the subject, though it is realized with the nominative marker. The observation that the second nominal is not the subject does not automatically warrant that it is an object in Korean either.[19] We already demonstrated that the nominative object exhibits different properties than those of typical objects. A typical object is marked accusative and may appear as the subject in a passive sentence. As we saw, the second nominal in the NOC is marked nominative, and the passivization of the NOC is not readily available, as illustrated in (38a)–(38c).

| *Mia-ka | Gio-eyuyhay | coh-a | ci-ess-ta. |

| M-NOM | G-by | like-COMP | PAS-PST-DECL |

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Mia was being liked by Gio.’ | |||

| *pata-ka | san-eyuyhay | toy-e | ci-ess-ta. |

| sea-NOM | mountain-by | become-COMP | PAS-PST-DECL |

| Intended: ‘It (the sea) became the sea by the mountain.’ | |||

| *Mia-ka | Gio-eyuyhay | po-ko | siph-e | ci-ess-ta. |

| M-NOM | G-by | see-COMP | desire-COMP | PAS-PST-DECL |

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Mia was missed by Gio.’ | ||||

The discussion provided so far shows that the second nominal in the NOC exhibits in-between properties of typical subjects and objects. Incorporating intermediate properties and various degrees of prototypicality is an essential task in CG. Langacker (2008: 9) states that identifying “the range of structures that are prototypical in language as well as their degree of prototypicality” is, in fact, a primary goal of functional theory. In later sections, we account for why this type of in-between property is expected in the NOC. In sum, the second nominals in the NOC are not the subjects.

4.2 Objecthood tests

In Section 3.1, we briefly discussed that the second nominals in the NOC are not passivized, which is one potential piece of evidence for their objecthood. However, they do not exhibit a full range of object properties. Let us consider the typical tests for objecthood as shown in (39). The second nominal, Mia, cannot undergo relativization and scrambling – which are typical properties of objects – while it passes clefting, pronominalization, and wh-question tests. The outcomes of the tests illustrate that the second nominal in the NOC exhibits only partial object properties. It is important to note that these tests should not be understood as defining characteristics of objects. A nominal’s objecthood is sufficient but not necessary for these properties. In other words, objects tend to exhibit these properties, whereas exhibiting these properties does not warrant a nominal’s objecthood. The purpose of these tests here is to demonstrate that nominative objects do not even pass all of the tests often used for objecthood in the generative linguistics literature.[20]

| nay-ka | Mia-ka | coh-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-NOM | like-DECL |

| ‘I like Mia.’ |

| *[nay-ka | e i | coh]-un | Mia i | |

| I-NOM | like-ADN | M | ||

| Intended: ‘Mia (who) I like’ | (relativization) | |||

| *Mia i -ka | [nay-ka | e i | coh-ta]. | |

| I-NOM | I-NOM | like-DECL | ||

| Intended: ‘I like Mia.’ | (scrambling) | |||

| [Gio-ka | coh-un | kes]-un | Mia-i-ta. | |

| G-NOM | like-ADN | thing-REL | M-COP-DECL | |

| ‘It is Mia who Gio likes.’ | (clefting) | |||

| Gio-ka | kyay-ka | coh-u-ni? |

| G-NOM | that.person-NOM | like-CONN-Q |

| ‘Does Gio like that person?’ | (pronominalization) | |

| Gio-ka | nukwu-ka | coh-u-ni? | |

| G-NOM | who-NOM | like-CONN-Q | |

| ‘Who does Gio like?’ | (wh-question) | ||

The tests in (39) provide additional evidence for the partial objecthood of the second nominal in the NOC; the second nominals in the NOC do not show a full range of the properties shared by typical objects. In our view, the second nominal in the NOC exhibits some object properties because it is a stimulus. At the same time, it corresponds to the internal representation of the stimulus in the domain of the experiencer’s mental experience; since the second nominal represents the head of the action-chain, it contrasts with typical objects.

4.3 The semi-copula toy-ta ‘become’

The verb toy-ta ‘become’ demonstrates some similarities to the NOC, and we need to examine if it also sanctions the NOC. Scholars such as Yoon (2007) and Levin (2017) assume that the toy- construction gives rise to the NOC because it shows stativity, and all the objecthood tests we used in (39) can be felicitously applied to that construction. Be that as it may, toy- does not show transitivity; it does not form either a transitive or an intransitive clause; rather, toy- denotes a relation of identity like the copula -i. If so, toy- behaves like a copula verb, though there are some differences between the two. While toy- in (40c) cannot be omitted, as shown in (40d), ellipsis of the true copula commonly occurs, as demonstrated in (40a)–(40b). For this reason, the verb toy- may be categorized as a semi-copula in terms of Hengveld (1992) and Butler (2003).

| ce-nun | khephi-i-yo. | ||

| I-TOP | coffee-COP-POL | ||

| ‘As for me, (I would like to have) coffee.’ | |||

| ce-nun | khephi-∅-yo. | ||

| I-TOP | coffee-COP-POL | ||

| ‘As for me, (I would like to have) coffee.’ | |||

| Gio-ka | kyoswu-ka | toy-ney. |

| G-NOM | professor-NOM | become-DECL |

| ‘(It is news to me that) Gio becomes a professor.’ | ||

| *Gio-ka | kyoswu-ka-∅-ney | |||

| G-NOM | dean-NOM-become-DECL | |||

| Intended: ‘(It is news to me that) Gio becomes a professor.’ | ||||

There is another reason we categorize toy- as a copula verb, whether it be a semi-copula or true copula verb. From a typological perspective, Dixon (2002) distinguishes copula clauses from transitive and intransitive clauses. Copula clauses have two core arguments – copula subject and copula complement – together with a copula verb. Dixon (2002: 1) provides criteria for the categorization of copula verbs. According to Dixon, copula verbs “show a relation of identity/equation or of attribution. It may also have some or all of the senses: location, possession, wanting or benefaction, and existence.” The toy- verb fits the description of Dixon’s categorization of (semi)-copula in that it shows a relation of identity or attribution, and it has two core arguments. For example, (40c) shows an identity relation between Gio and kyoswu ‘professor’, and the toy-ta verb maintains two core arguments – Gio and kyoswu ‘professor’ – without exhibiting any degree of transitivity. For this reason, we exclude the toy-ta construction from the NOC unlike scholars like Yoon (2007).[21]

5 Nominative objects and a wide scope reading

The property we illustrate in this section concerns scope. This issue is also discussed in detail in Takano (2003) and Koizumi (2008) for Japanese, and Jung (2011) for Korean. The observation is that the nominative object takes a wide scope over negation and siph-ta ‘desire’. As indicated by the translation, (41) illustrates this case; the nominative object with the delimiter -man takes a wide scope.

| nay-ka | Gio-man-i | po-ko | siph-ci | ahn-ass-ta. |

| I-NOM | G-only-NOM | see-COMP | desire-CONN | NEG-PST-DECL |

| ‘It is only Gio that I did not miss.’ | ||||

| (ONLY > NEG > siph-ta) | ||||

(41) contrasts with (42), where the delimiter-marked Gio is realized with the accusative marker.

| nay-ka | Gio-man-ul | po-ko | siph-ci | ahn-ass-ta. |

| I-NOM | G-only-ACC | see-COMP | desire-CONN | NEG-PST-DECL |

| ‘It is not the case that I missed only Gio.’ | ||||

| (NEG > siph-ta > ONLY) | ||||

Scholars propose different types of analyses to capture the scopal difference between the two types of examples illustrated in (41) and (42). Working within the generative linguistics framework, some scholars (Bobalijk and Wurmbrand 2005; Koizumi 1998; Nevins and Anand 2003 for Japanese; Jung 2011 for Korean) postulate a VP-complement structure in which an invisible trace is left behind from A-movement. Other scholars, such as Saito (2000), Hoshi (2001, 2005, and Takano (2003), propose a complex predicate formation before the merger of the nominative object. In this type of approach, the nominative object always appears higher than the second verb, thereby leading to a wide scope interpretation.[22]

The real challenge, however, comes from the fact that scope-related interpretations are much more flexible than the previous researchers observed.[23] Example (43) illustrates the NOC with a simple psychological predicate. Once given an appropriate context, NEG in (43) can have wide scope over -man. The same scopal interpretation is possible in (44), which is a variation of (43).

| nay-ka | Gio-man-i | mip-ci | ahn-ass-e. |

| I-NOM | G-only-NOM | hate-CONN | NEG-PST-DECL |

| nehuy-tul | motwu | ta | miwe-ss-tako! |

| you-PL | all | all | hate-PST-END |

| ‘It is not the case that I hated only Gio. I hated all of you guys!’ | |||

| (NEG > ONLY) | |||

| nay-ka | Gio-man-i | po-ko | siph-ci | ahn-ass-e. |

| I-NOM | G-only-NOM | see-COMP | desire-CONN | NEG-PST-DECL |

| nehuy-tul | motwu | ta | po-ko | siph-ss-tako! |

| you-PL | all | all | see-COMP | desire-PST-END |

| ‘It is not the case that I missed only Gio. I missed all of you guys!’ | ||||

| (NEG > siph-ta > ONLY) | ||||

The wide scope interpretation of the nominative object is indeed more natural than the narrow scope reading, but it is not an absolute property of the nominative object. It is also true that we need more contextual and prosodic information to get the readings in (43) and (44). Granted, it is crucial to recognize that this type of flexible scopal interpretation is difficult to explain in the previous analyses, where the conceptualizer’s construal ability plays no role. Another important consideration in analyzing Examples (41–44) is the role of the delimiter -man ‘only’. The scopal differences shown in (41) and (42) might be due to the delimiter as well as different types of construals the speaker utilizes at different levels of conceptualization of the structure.[24] Regarding the flexibility of scope-related predictions, the accusative-marked nominal can also take scope over the negation in a certain speech context, which is shown in (45a). As a result, (45a) yields the same interpretation as the topicalized version in (45b).

| nay-ka | Gio-man-ul | po-ko | siph-ci | ahn-ass-ta. |

| I-NOM | G-only-ACC | see-COMP | desire-CONN | NEG-PST-DECL |

| ‘Only Gio, I didn’t want to see.’ | ||||

| (ONLY > NEG > siph-ta) | ||||

| Gio-man-ul | nay-ka | po-ko | siph-ci | ahn-ass-ta. |

| G-only-ACC | I-NOM | see-COMP | desire-CONN | NEG-PST-DECL |

| ‘Only Gio, I didn’t want to see.’ | ||||

| (ONLY > NEG > siph-ta) | ||||

What we have shown is that different readings based on scopal differences cannot be accounted for in isolation from how the speaker construes a given situation. For this reason, purely structure-based analyses, which pay little to no attention to how speakers conceptualize a situation in different ways, cannot provide the full picture.

6 The desiderative construction and case alternation

The desiderative construction was briefly discussed in Section 3.2. This section examines this construction in more detail.

6.1 The VP-complement approach to the desiderative construction

Kim (2016: 86–89) discusses three possible analyses of the desiderative construction. The first is a VP approach, where case alternation does not entail differences of structure. This view is supported by Choi (2009) and Jung (2011). A simplified analysis of this approach is provided in (46) with the bracket notation. In these examples, siph-ta takes the embedded VP as a complement.

| Gio-ka | [[Mia-ka | [po-ko]] | siph-ta.] |

| G-NOM | M-NOM | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio misses Mia.’ | |||

| Gio-ka | [[Mia-lul | po-ko] | siph-ta.] |

| G-NOM | M-ACC | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio wants to see Mia.’ | |||

Kim (2016: 87–88) provides criticism of this type of analysis by pointing out that Choi’s (2009) VP analysis faces a theory-internal challenge. For example, the main verb po- ‘see’ is transitive and requires an accusative-marked object. When it occurs with siph-ta, the object may be marked nominative. This case marking pattern is a strong indication that siph-ta is responsible for the nominative marking of the object. If so, the nominative case must be assigned non-locally; siph-ta and the object belong to two different case domains. Depending on the researcher’s viewpoint, this might not be a serious issue. With some theoretical modifications, we can certainly fix the non-local case assignment problem. In fact, the same problem does not arise in a later VP complement approach, such as Jung’s (2011).

Another problem with this approach comes from examples like (47). While (47a) is acceptable as expected, the unacceptability of (47b) is not easily explained; there is no mechanism to block the occurrence of the adverb between the main verb and siph-ta in Choi’s (2009) analysis.

| Gio-ka | Mia-lul | ppalli | po-ko | siph-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-ACC | quickly | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio wants to see Mia soon.’ | ||||

| *Gio-ka | Mia-lul | po-ko | ppalli | siph-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-ACC | see-COMP | quickly | desire-DECL |

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Gio wants to see Mia soon.’ | ||||

An even more vexing problem concerns the interpretation of (47a). When the object is marked accusative in examples like (47), the sentence denotes complex events. Since we assume that forms reflect meanings, the question of how these meanings are reflected in different case forms becomes a crucial and relevant question. In Choi’s analysis, the different semantic properties of the case marking patterns have not been addressed nor discussed. We will address this in later subsections and Section 7.

6.2 The complex predicate approach to siph-ta

The second view is a complex predicate approach, which is the view Kim (2016) adopts for his analysis. While we support Kim’s approach in the sense that the main verb and -ko siph-ta form a sort of complex predicate, we suggest that Kim’s proposal be modified, especially to account for the complex event reading we have addressed in the previous subsection.

In Kim’s approach, the main verb and siph-ta form a complex predicate in the syntax. Kim’s analysis is based on two major pieces of evidence: Negative Polarity Item (NPI) licensing and syntactic cohesion. Syntactic cohesion was already addressed in the previous section: adverbs cannot intervene between the main verb and siph-ta. Kim’s NPI test demonstrates the quintessential properties of complex predicates. Korean NPIs need to be licensed by a clause-mate negative expression. (48a) is not felicitous because the negative auxiliary verb ahn- ‘NEG’ is in a different VP domain from the NPI amwukes-to. By contrast, the negative particle, an, appears in the same clause as the NPI in (48b), yielding an acceptable result.

| *Mimi-lul | [amwukes-to | mek-tolok] | seltukha-ci | anh-ass-ta. |

| M-ACC | anything-also | eat-CONN | persuade-CONN | NEG-PST-DECL |

| ‘Intended: (We) did not persuade Mimi to eat anything.’ | ||||

| (Kim 2016: 91) | ||||

| Mimi-lul | [amwukes-to | an | mek-tolok] | seltukha-yess-ta. |

| M-ACC | anything-also | NEG | eat-CONN | persuade-PST-DECL |

| ‘(We) persuaded Mimi not to eat anything.’ | ||||

| (Kim 2016: 91) | ||||

The same test can be extended to the siph-ta construction to check if V + siph-ta forms a complex predicate. Our prediction is borne out as shown in (49); the acceptability of (49) shows that it is indeed mono-clausal, and V + siph-ta is a single predicate.

| Mimi-nun | [amwukes-to/amwukes-ul | mek-ko | siph-ci | |

| M-TOP | anything-also/anything-ACC | eat-COMP | desire-CONN | |

| anh-ass-ta.] | ||||

| NEG-PST-DECL | ||||

| ‘(I feel like) Mimi didn’t feel like eating anything.’ | ||||

This is a good place to identify what complex predicates are in Korean. According to Amberber et al. (2010), there is no widely accepted answer to this question nor an agreed-upon set of criteria to classify them. The researchers put forward a criterion to distinguish two types of complex predicate constructions: coverb and serial verb constructions. While coverb constructions typically involve a light verb, serial verb constructions are a sequence of verbs without any overt marker of syntactic dependency. The siph-ta construction does not fit either category; siph-ta is not a light verb, and the overt connector, -ko, is required between the main verb and siph-ta. Nonetheless, it shares fundamental properties with the serial verb construction described by Comrie (1995), which are summarized in (50).

| a. | The sequence of verbs in a serial verb construction occurs within a single clause. |

| b. | The verbs in the serial verb construction are interpreted as expressing a single event. |

We have demonstrated that (50a) holds true for the siph-ta construction. We have also indicated that the desiderative NOC denotes a single event, such as (I feel like) Gio misses Mia or I crave apples. The NOC examples we have discussed precisely exhibit the properties shown in (49).

The challenge is when the object of the siph-ta construction is realized with the accusative marker. Though the accusative siph-ta construction shares some grammatical properties with the nominative siph-ta construction, it appears to denote complex events as indicated with our translations like I want to eat apples and (I feel like) Gio wants to see Mia. These are perplexing examples, but we believe the complex event interpretation does not undermine the complex predicate-based analysis. Whether simple or complex events are denoted, siph-ta can form a complex predicate with the main verb. The complex predicate can then be construed either as a psychological verb or as a transitive verb that denotes complex events. In other words, one typical role of a complex predicate is to express a simple event, but the speaker can construe it as a situation denoted by a complex event. As unorthodox as it may sound, this type of availability of alternative construals might be the reason there is no consensus on the definition of the serial verb construction or complex predicates in general. It seems that there is a consensus on the mono-clausality of serial verb constructions among scholars (Butt 2010). However, the definition described in (50b) is far from settled. While Aikhenvald (2006) agrees with Comrie (1995) on the single event nature of the serial verb construction, Amberber et al. (2010) and Foley (2010) claim that the serial verb construction primarily denotes multi-events. How to define serial verbs or complex predicates in Korean is not the primary concern of our research here, but it is worth pointing out that whether or not a clause denotes a single event is not a robust measure to identify a complex predicate.

Though the complex predicate approach overcomes the challenge demonstrated in the examples in (45), it makes some similar predictions to those of the VP analysis. Since the complex predicate analysis does not entail different structures for the siph-ta construction, the nominative and the accusative cases are licensed in the same position in a simpler syntactic structure (see Kim 2016: 76). Then, under this analysis, the scopal difference between (43) and (44) cannot be explained. This is because the case alternation is accounted for by one structure, and the scopal relations among NEG, siph-ta, and ONLY are identical for both case patterns. We can avoid this problem by stating that scopal relations are completely semantic notions and are orthogonal to structure. But this is not what Kim’s analysis assumes nor pursues; therefore, Kim’s proposal needs some revisions to fully incorporate our observations.

6.3 The mixed approach

The third approach, proposed by Kim and Maling (1998), is a case of a mixed analysis. Kim and Maling posit two different structures for the case patterns of the siph-ta construction. When the object of the verb bears the accusative marking, the construction exhibits a full range of VP-complementation properties. By contrast, the siph-ta construction with a nominative-marked object does not show any of the properties of VP-complementation. For instance, Kim and Maling argue that (51a) and (51c) have a VP complement structure where two VPs are conjoined, and -ko siph is gapped in the first conjunct (see also Sells and Cho 1991). The operations are not applicable to the nominative-marked siph-ta construction as shown in (51b) and (51d).[25] This indicates that X-ko siph-ta behaves like one unit: a complex predicate.

| Cheli-nun | pap-ul | cis-ko, | ppallay-lul | ha-ko | siph-ess-ta. |

| C-TOP | rice-ACC | cook-CONJ | laundry-ACC | do-COMP | desire-PST-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Cheli wanted to cook rice and do the laundry.’ | |||||

| (Kim and Maling 1998: 140) | |||||

| Cheli-nun | pap-i | cis-ko, | ppallay-ka | ||

| C-TOP | rice-NOM | cook-CONJ | laundry-NOM | ||

| ha-ko | siph-ess-ta. | ||||

| do-COMP | desire-PST-DECL | ||||

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Cheli wanted to cook rice and do the laundry.’ | |||||

| (Kim and Maling 1998: 140) | |||||

| Cheli-nun | Ford-lul | sa-ko, | Swuni-nun | BMW-lul | sa-ko | |

| C-TOP | F-ACC | buy-CONJ | S-TOP | B-ACC | buy-COMP | |

| siph-ess-ta. | ||||||

| desire-PST-DECL | ||||||

| ‘(I feel like) Cheli wanted to buy a Ford, and Swuni a BMW.’ | ||||||

| (Kim and Maling 1998: 140) | ||||||

| *Cheli-nun | Ford-ka | sa-ko, | Swuni-nun | BMW-lul | sa-ko | |

| C-TOP | F-NOM | buy-CONJ | S-TOP | B-ACC | buy-COMP | |

| siph-ess-ta. | ||||||

| desire-PST-DECL | ||||||

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Cheli wanted to buy a Ford, and Swuni a BMW.’ | ||||||

| (Kim and Maling 1998: 140) | ||||||

Though their analysis has an advantage in explaining the examples provided in (51a)–(51d), it makes some problematic predictions. Since there are two siph-ta verbs in (51a), for instance, we predict that there are two independent events. However, it is highly unlikely that we interpret (51a) as something like (I feel like) Cheli wanted to cook rice and wanted to do the laundry (not necessarily in that order). To us, only the sequential reading is available: (I feel like) Cheli wanted to cook rice and do the laundry (in that order). If that is the case, what siph-ta takes as the first conjunct is not a full VP, and the conjoined structure has only one ‘desiring state.’

A more serious issue with Kim and Maling’s analysis is the increased acceptability of examples like (51b) with an appropriate choice of verbs coupled with relevant pauses, as shown in (52). Here, both // and /// represent pauses, where /// notates a longer pause than //.

| nay-ka | cikum // pap-i | mek-ko /// | |||||

| I-NOM | now rice-NOM | eat-CONJ | |||||

| swul-i | masi-ko | siph-ta-n | maliya! | ||||

| alcohol-NOM | drink-COMP | desire-DECL-CONN | DM | ||||

| ‘I want to eat rice and drink alcoholic drinks now.’ | |||||||

Kim and Maling’s analysis predicts that (52) must be unacceptable; since mek-ko cannot form a complex predicate with siph-ta in the first conjunct, the nominative marking is not allowed. Contrary to this prediction, (52) is natural in casual conversation, which weakens the validity of their dichotomous structure-based claim.

Despite some weaknesses, Kim and Maling provide an insightful analysis of the siph-ta construction. In particular, their argument that the single-event and the multi-event readings are associated with different structures resembles the proposal we put forward, though our focus is on semantic structures. That being said, our analysis takes the opposite direction; while Kim and Maling assume that the structural difference leads to different interpretations of the siph-ta construction, we show that the different case patterns are a mere reflection of the two types of conceptualization that the siph-ta construction motivates. A detailed discussion of our analysis is provided in Section 7.

6.4 On case alternation and different types of construals

We have thus far made two assumptions in dealing with meanings. First, the semantic structure is determined based on the interlocuter’s construals. Second, grammatical forms determine meanings. As for the first assumption, Croft (2012) characterizes a construal as a conceptual semantic structure, as in (53).

| a. | There are multiple alternative construals of an expression available. |

| b. | A speaker has to choose one construal or another; they are mutually exclusive. |

| c. | No construal is the “best” or “right” one out of context. |

| (Croft 2012: 14) |

The characteristics provided in (53) accurately summarize our view. Alternative construals are ubiquitously observed in everyday language use. The English verb see is often categorized as a state verb in Vendler’s classification (Vendler 1967) because the situation described by the verb does not change over time and does not have a natural endpoint. However, the same verb may have alternative construals as in (54a) and (54b). Without any morphological derivation, the situation described by the verb can be construed as a transitory state as in (54a), or the verb may have an achievement construal as in (54b) with the past morphology.[26]

| a. | I see Lake Tahoe right now. |

| b. | I reached the top of the hill and saw Lake Tahoe. |

Similar types of alternative construals are available in Korean. The verb a(l)- ‘know’ that is typically analyzed as a state verb may have alternative construals. While (55a) shows an example of a transitory state construal, (55b) shows an achievement construal. Note that the a(l)- verb in (55b) is interpreted as past, though there is no past marking.

| na | ku | tap | cikum | al-a! |

| I | that | answer | now | know-DECL |

| ‘Now I know the answer!’ | ||||

| na | wenlay | ku-ke | a-nuntey, |

| I | originally | that-thing | know-CONN |

| cikum | ic-e | peli-ess-ta. | |

| now | forget-COMP | AUX-PST-DECL | |

| ‘I originally knew the answer, but I forgot it now.’ | |||

Working from this perspective, the suggestion that case alternation is an outcome of alternative construals is expected. In dealing with adverbial case marking in Korean like (56), Park (2013) argues that accusative marking is a result of the predicate’s perfective construal of a situation, while the nominative-marked variety arises when the same predicate is construed imperfectively. For example, (56a) is understood as a continuation of an ongoing stable situation. In (56b), however, the raining event is internally heterogenous, resulting in the interpretation of undirected activity in terms of Talmy (1985).[27]

| pi-ka | twu-sikan | tongan-i | nayli-ess-ta. |

| rain-NOM | two-hours | during-NOM | fall-PST-DECL |

| ‘It rained for 2 h.’ | |||

| pi-ka | twu-sikan | tongan-ul | nayli-ess-ta. |

| rain-NOM | two-hours | during-ACC | fall-PST-DECL |

| ‘Rain fell for 2 h.’ | |||

More specifically, Park argues that the case alternation is tied to how the speaker construes a given situation. When the situation is construed imperfectivly, the adverbial functions as a global setting that includes a whole event. In this situation, it is marked nominative. By contrast, when the situation is construed perfectively, the adverbial characterizes a fragment of a setting, i.e., a location, which is the site of a single participant. In this instance, it is marked accusative.[28] We will not go into detail on Park (2013), but his analysis demonstrates how different construals lead to different case markings, thereby showing how our two assumptions – construal and form/meaning connection – are satisfied in analyzing case alternation phenomena.

From non-cognitive viewpoints, Kim and Sells’s (2010) and Lee’s (2017) analyses of Korean adverbial case also strongly demonstrate that a syntactic account alone is not satisfactory to understand case alternation phenomena. These researchers emphasize the importance of the predicate’s aspectual type and the degree of animacy of the subject. They go even further to show that aspectual types and the degree of animacy might vary depending on the given context, or depending on the speaker’s construal if we rephrase their arguments.[29]

Turning back to the case alternation in the siph-ta construction, we propose that the complex predicate, V + siph-ta, may be construed as a psychological predicate, which yields a nominative-marked object. Alternatively, the same complex predicate may be construed as a complex event. One curious example is shown in (57). At first glance, it seems that po-ko siph-ta cannot have a psychological verb construal due to the existence of the manner adverbial ppali ‘quickly’. Even then, the object is marked nominative.

| Gio-ka | Mia-ka | ppali | po-ko | siph-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-NOM | quickly | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio misses Mia a lot.’ | ||||

Note, however, that the adverb ppali ‘quickly’ is polysemous, and it has the meaning of an intensifier, as indicated by the translation in (57). So (57) is identical to (58) in its intended meaning, and the nominative marking on the object is expected.

| Gio-ka | Mia-ka | nemwu | po-ko | siph-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-NOM | much | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio misses Mia a lot.’ | ||||

Thus far, we have identified major properties of the Korean NOC. The next section provides our technical CG analysis of the NOC.

7 A CG analysis of Korean nominative objects

In this section, we provide an analysis of each of the two types of the NOC we have discussed. After analyzing the NOC with psychological predicates, we analyze case alternation patterns of the desiderative construction. The major properties of the NOC we have discussed are summarized in (59).[30]

A summary of the properties of nominative objects

| Subject- or objecthood of the nominative object | Major subject | ✗ |

| Subject | ✗ | |

| Object | ✓ (partial) | |

| Experiencer or stimulus properties of the nominative object | Experiencer | ✗ |

| Stimulus | ✓ | |

| Scope | Narrow scope | ✓ |

| Wide scope | ✓(preferred) | |

| Predicate type | Psychological verbs | ✓ |

| Complex predicate or VP complementation properties of X-ko siph-ta | Complex predicate | ✓ |

| VP complement | ✗ | |

| Case alternation between NOM and ACC | Regular NOC | ✗ |

| Siph-ta NOC | ✓ |

7.1 NOCs with psychological verbs

We begin with the NOC with simple psychological predicates. The CG diagrams for (60) are provided in Figure 5.

Third-person versus first-person NOC.

| Gio-ka | Mia-ka | coh-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-NOM | like-DECL |

| (I feel like) Gio likes Mia. | ||

| nay-ka | Mia-ka | coh-ta. |

| I-NOM | M-NOM | like-DECL |

| ‘I like Mia.’ | ||

Figure 5(a) is for (60a), where the speaker (S) takes the viewpoint of the third-person experiencer (C′) by creating a surrogate scope (SS). The stimulus, Mia, sends a stimulative signal to the surrogate experiencer, Gio.[31] Gio then undergoes an internal change of state, and Mia existing in the CS is a part of the state resulting from the change. Gio experiences this state of mind by making mental contact with it, indicated by the dashed arrow within the largest circle. Note that (61a) is construed as the subject’s experience assessed by the speaker. (60b) is essentially identical to (60a) except for one component. In (60b), the conceptualizer and the surrogate conceptualizer are identical; therefore, the two scopes collapse, yielding the semantic structure in Figure 5(b).

As for the case marking pattern in (60a), Mia is the sole participant in the relationship described within the surrogate scope and is the head of the action-chain; therefore, it is marked nominative. The surrogate experiencer, Gio, is the primary participant in the profiled process, which makes mental contact with the state of mind. Therefore, it is marked nominative as well.

7.2 The NOC with the verb siph-ta

The major issue concerning the desiderative construction revolves around the case alternation the construction allows. We reintroduce the alternation in (61).

| Gio-ka | Mia-ka | po-ko | siph-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-NOM | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio misses Mia.’ | |||

| Gio-ka | Mia-lul | po-ko | siph-ta. |

| G-NOM | M-ACC | see-COMP | desire-DECL |

| ‘(I feel like) Gio wanted to see Mia.’ | |||

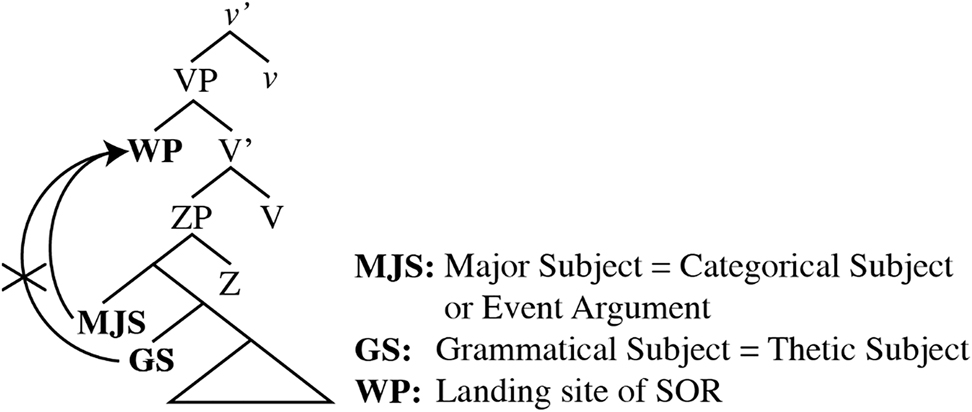

(61a) and (61b) are illustrated in Figure 6(a) and (b), respectively. Let us first discuss Figure 6(a) where the thick lines indicate the profile. The internally represented stimulus, Mia, is not a participant in the profiled process but a part of the embedded relationship, which is enclosed within the dashed rectangle. The verb siph-ta profiles both the existential relationship denoted by the solid-line arrow and the experiential relationship denoted by the dashed-line arrow. The former represents the existence of the transitive process within an emotional domain in the mind of the experiencer. The zigzag line inside the dashed rectangle represents the transitive relationship, po-ko ‘see-COMP’. In the embedded relationship, the trajector of the transitive relationship is only schematically represented and is identified as the surrogate experiencer (C′) by the correspondence relation indicated by the dotted line. Within the surrogate scope, Mia is the sole participant, thereby gaining the trajector status and being marked nominative. The semantic structure for (61b) is essentially identical to that of (61a), with the only difference manifesting in the profile; the profile is given to the embedded transitive relationship in (61b), and all the outer layers pertaining to experience are in the background and out of profile, as indicated by non-bold lines.

![Figure 6:

Two types of [V + siph-ta] constructions, based on Kumashiro (2016: 219).](/document/doi/10.1515/ling-2020-0248/asset/graphic/j_ling-2020-0248_fig_006.jpg)

Two types of [V + siph-ta] constructions, based on Kumashiro (2016: 219).

Our analysis makes several desirable predictions concerning the desiderative construction. The first concerns the case-marking patterns. When siph-ta is construed as having the semantic structure in Figure 6(a), the object nominal is realized with the nominative marker because the new trajector status is conferred on the nominal. Figure 6(b) shows how the accusative marking arises. In the embedded transitive relationship, the active participant of the profiled process is Gio, and the passive participant is Mia. Therefore, the nominative and accusative markings are given to them, respectively.

One might view the structure in Figure 6(b) similar to the VP complement analysis proposed by Kim and Maling (1998). Our analysis is similar in that the embedded clause is required by siph-ta, which leads to an interpretation similar to the VP complement structure found in Kim and Maling. The noticeable difference is we do not have to compose the full VP first in the structure shown in Figure 6(b). For example, X-ko siph-ta is composed with the verb po-ta ‘see-DECL’ to create a complex predicate, followed by the elaboration of the object and the subject.[32] Our analysis systematically accounts for coordination and gapping upon which Kim and Maling rely to support their analysis. (62a) is felicitous, where two siph-ta constructions are conjoined. When the first conjunct is used without -ko siph as in (62b), the most natural interpretation is to view the event as a sequenced one. The interpretation indicated in (62c) is only marginally acceptable, or not available at all.

| Gio-ka | sakwa-lul | mek-ko | siph-ko | ||

| G-NOM | apple-ACC | eat-COMP | desire-CONJ | ||

| mwul-ul | masi-ko | siph-ta. | |||

| water-ACC | drink-COMP | desire-DECL | |||

| ‘(I feel like) Gio wants to eat an apple and wants to drink water | |||||

| (not necessarily in this order).’ | |||||

| Gio-ka | sakwa-lul | mek-ko | |||

| G-NOM | apple-ACC | eat-CONJ | |||

| mwul-ul | masi-ko | siph-ta. | |||

| water-ACC | drink-COMP | desire-DECL | |||

| ‘(I feel like) Gio wants to eat an apple first and then drink water.’ | |||||

| *Gio-ka | sakwa-lul | mek-∅ | ∅-ko | ||

| G-NOM | apple-ACC | eat-COMP | desire-CONJ | ||

| mwul-ul | masi-ko | siph-ta. | |||

| water-ACC | drink-COMP | desire-DECL | |||

| Intended: ‘(I feel like) Gio wants to eat an apple and wants to drink water (but she does not care which one comes first).’ | |||||

Kim and Maling’s analysis cannot explain the (62c) interpretation easily because the first VP conjunct is fully loaded with -ko ‘COMP’ and -siph, followed by the gapping of these elements. Then, we expect to have the intended meaning without difficulty because there are two independent ‘desiring states’ denoted by two instances of siph-ta. The same issue does not arise in our analysis because there is only one ‘desiring state’ in the siph-ta construction. Therefore, examples like (62c) are interpreted as one ‘desiring state’ of a sequence of events, as opposed to desiring two independent events.