Abstract

In this article we identify and motivate the main word order patterns of adjectives in the English NP. Theoretically, we situate ourselves within the tradition of semiotically-based, cognitive-functional construction grammars as developed by such linguists as Halliday, Langacker and McGregor. In this tradition, the lexicogrammar is assumed to exist to symbolize semantic functions. We argue that the various semantic functions of adjectives in the English NP are coded by different modification relations, which differ in terms of where and how they fit into the structural assembly of the whole NP. We hold that function motivates structure, and that order is an epiphenomenon of structure. Therefore, we first set out our model of the functions that can be fulfilled by adjectives in the English NP. This model is innovative in a number of ways. Theoretically, it extends the distinction between representational and interpersonal modifiers. Descriptively, we elucidate the traditionally recognized representational functions of classifier and epithet as well as the interpersonal functions of noun-intensifier and secondary determiner. To this set, we add the hitherto barely recognized interpersonal functions of focus marker and metadesignative. We also systematically investigate the possibility for coordination and subordination between adjectives fulfilling the same function. In a second step, we then correlate this functional-structural model with the general ordering tendencies of the functions realized by adjectives. We specify the general left-to-right ordering of the six functions, pointing out possible and impossible orders of the functions relative to each other. We interpret the distinction between representational and interpersonal modifiers with regard to their different ordering potential. Finally, we look at the main ordering options available for multiple adjectives realizing the same function.

1 Introduction

This study of the order of adjectives in present-day English inserts itself in a long tradition of functional-structural analyses of the English NP, to which it is indebted both theoretically and descriptively.

The theoretical tradition we affiliate with can be labelled cognitive-functional in a broad sense. In this tradition, two tenets have always loomed large. Firstly, it is assumed that constructions are semiotic entities, with lexicogrammar as the symbolic stratum connecting phonology and semantics (e.g. Hjelmslev 1961 [1943]; Bolinger 1968; Halliday 1961 and Halliday 1994 [1985]; Langacker 1987 and Langacker 1991; McGregor 1997). We assume that grammar exists to symbolize semantic functions, which constitute the “semantics of grammar” (Wierzbicka 1988). In this study, we concentrate on the relation between the symbolizing (lexicogrammar) and symbolized (semantics of lexicogrammar), which lies within the linguistic sign function (Hjelmslev 1961 [1943]: 23). [1] The various semantic functions of adjectives in the English NP are coded by different modification relations, which differ in terms of where and how they fit into the structural assembly of the whole NP. Function motivates structure, of which order is an epiphenomenon, which allows us to correlate basic ordering tendencies with the different functions of adjectives. Secondly, following Halliday (1961), Langacker (1987), and Croft (2000), we adhere to the premise that grammatical categories are not primitives. Rather, the whole construction defines its elements of structure, which in turn have a motivated relation to the grammatical classes realizing them. Our approach hence does not start from grammatical categories such as adjectives, but from the modifier relations in which adjectives participate.

Our descriptive approach is indebted to the tradition distinguishing three main functions of adjectival modifiers in the NP, one central, and two peripheral, as in Bolinger (1967), Halliday and Hasan (1976), Bache (1978, 2000), Dixon (1982 [1977]), Quirk et al. (1985). The central function is that of referent-description (Bolinger 1967: 11–17), which has been referred to by such names as “descriptive modifier” (Bache 2000: 239) and “epithet” (Halliday 1994 [1985]: 184). Epithets constitute the central use of adjectives, in which they are said to describe the thing referred to. The two peripheral functions are classifiers, [2] e.g. congressional procedure, which further subclassify the category designated by the head noun, and secondary determiners, e.g. the same procedure, which share in the function of determiners. The relative order of adjectives, which is visualized in Table 1 for the example the same unpleasant congressional procedure (Bache 1978: 46), is motivated by the functional closeness of secondary determiners to determiners and of classifiers to the head noun as opposed to the epithet’s “pure” descriptive function, “untainted by determination and categorization” (Bache 2000: 239).

Order of central and peripheral adjectives.

| the | same | unpleasant | congressional | procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| secondary determiner | epithet | classifier |

In addition to these three functions, the degree modifier function has generally been recognized, as illustrated in (1), where pure heightens the gradable features of the description paranoid fantasy to its left (e.g. Bolinger 1972).

Aiming at exhaustive coverage, we add two more functions to the existing set: focus markers and metadesignatives (Breban and Davidse 2016a). The little noticed focus markers realized by adjectives situate, like adverbial focus markers (König 1991), a focus value relative to alternative values. For instance, in (2) mere conveys exclusive focus (‘only’), and it positions the focus value four against implied expectations of a higher number of hours needed. Metadesignatives have, to the best of our knowledge, not been recognized so far as a general function. [3] Metadesignatives involve the speaker assessing the relation between the designation and what it refers to, commenting on such things as goodness of fit, as in true god from true god, or the temporal relation between designation and referent, as in (3), where future signals that the categorization king of Great Britain will apply to the referent in the future only.

Here’s the handsomefutureking of Great Britain … (www.imgrum.net/media/1257519845290612374_1981430836)

What aspects of these six adjectival functions will be focused on in this article with a view to specifying their implications for order? While the functions of classifier, epithet, degree modifier and secondary determiner have been described in the literature, there is controversy about their precise structural assembly and its relation to ordering. [5] We set out to specify the precise units involved in all modification relations, the generally recognized ones as well as focus markers and metadesignatives. From the whole structural assembly, we will derive the ordering of the functions relative to each other, as well as the main ordering principles associated with subordination and coordination within each function. We will do this in the following steps. Firstly, in Section 2, we further explicate the theoretical constructs relevant to our description of adjectival modifiers. In Sections 3 to 9, we set out the modification relations involving adjectives that can be found in the English NP, beginning with the role played in them by the nominal head (Section 3). In Sections 4 to 9, we characterize the functions that can be realized by adjectives: Classifier (4), Epithet (5), Noun-intensifier (6), Secondary determiner (7), Focus marker (8), and Metadesignative (9). For each, the following topics will be discussed: 1. Semantics, 2. Grammatical behavior, 3. Structure, 4. Order relative to other functions, 5. Subordination or coordination between multiple instances. Our main interest is not in structural modelling per se, but in spelling out the consequences for ordering. We also provide diagnostic tests for recognizing the six adjectival functions by specifying their grammatical behavior such as possible and impossible alternates and relative orders. In Section 10 we summarize our predictions about functions and relative positions of adjectives as well as the types of meaning shifts these entail in case of polysemy.

2 Theoretical tenets

Theoretically, we align with semiotically-based, functional-structural construction grammars (e.g. Langacker 1987 and Langacker 1991; Halliday 1994 [1985]; McGregor 1997; Croft 2000). All versions of construction grammar hold that constructions are form-meaning couplings, but not all stress the importance of identifying the precise elements of structure between which conceptually motivated dependencies exist, with the resulting symbolic assembly qualifying as a construction (Langacker 2017: 10). Thus, in some variants of construction grammar, structures are stated simply in terms of the “mere linear contiguity” (McGregor 1997: 47) of elements of grammatical classes. The structure of NPs with classifier, e.g. a red wine, epithet, e.g. a red dress, and metadesignative, e.g. the future king, are then all represented as determiner+adjective+noun. Such a view of structure cannot, in our view, explain coercion, i.e. functions being realized by incongruent grammatical classes, as in a ten beauty, where the number ten does not measure a quantity, but heightens the degree of beauty. Explaining such cases of coercion requires recognizing the coding force of different modifier-modified relations, which can shift the original meaning of a category member into one compatible with the modifier relation in question.

For the analysis of structural-functional relations, we adhere to Langacker’s (1987, 1999) notion of structural assembly, which seeks to identify not only which precise units are involved in individual dependency relations, but also in what order these relations are put together. Langacker (1999: 152) holds that grammatical constructions involve composite structures, some of whose components are transparently assembled, whilst others may be “only partially discernible (or even indiscernible) within the composite whole”. Structural analysis is concerned with “the order in which component structures are successively combined to form progressively more elaborate composite structures” (Langacker 1987: 310). The order of assembly that analysts have to identify is the one that accounts best for the composite semantics of the structure, as conceptual dependencies between elements are “largely responsible, in the final analysis, for their combinatory behavior” (Langacker 1987: 305).

Modifiers are generally accepted to be elements that are semantically dependent and select their heads (Langacker 1987: 235–236, 309–310). The head determines the semantic profile (Langacker 1987: 235–236) and the distribution of the whole modifier-head unit. The functions realized by adjectives in the English NP are almost all coded as modifiers sharing grammatical features with the head noun. Following McGregor (1997), we distinguish two basic types of modifiers, representational and interpersonal ones. Representational functions are concerned with describing the entity referred to, while interpersonal functions construe speaker stance and speaker-hearer interaction with respect to the representational content (e.g. Halliday 1994 [1985]).

With representational modification, “one unit expands on the other, adding further details, providing … a more complete representation of some referent” (McGregor 1997: 210). Representational modifier-head relations are coded in the way traditionally envisioned for modification, viz. by a sister-sister relation. This is the syntagmatic relation which exists between units which are in some sense sisters, i.e. between which a direct relationship obtains, not one mediated by a shared mother (Hudson 1984: 94). Following the convention used by Hudson (1984, 1986), such sister-sister relations will be represented by an arrow arcpointing from head to modifier, as illustrated for red wine (Figure 1).

Dependency structure: red wine.

“Interpersonal modifiers” (McGregor 1997: 236) express speaker-related meanings which are not added to the representational material designated by the unit being modified. Rather they change and mold this representational material. Take the degree modifier pure, which conveys the speaker’s qualitative assessment, in pure paranoid fantasy. Precisely because intensification does not add representational meaning, it can also be expressed paralinguistically, for instance by prosodic salience. Compare he’s a complete fool with he’s a FOOL. McGregor (1997: 209–214) argues that interpersonal modifiers should be analyzed as a relation “in which a unit applies over a certain domain, leaving its mark on the entirety of this domain” (1997: 210), i.e. as a relation between a scopal [6] domain and its (interpersonal) modifier. McGregor also notes that an interpersonal modifier “applies to just one particular type of thing that [the unit] can represent” (1997: 214), such as the gradable properties of paranoid fantasy. Following McGregor (1997: 64–70), we use boxed representations to visualize how the interpersonal modifier (in the larger box) encloses the unit it molds and changes, as illustrated for pure paranoid fantasy (Figure 2).

Dependency structure: pure paranoid fantasy.

In the following sections, we will build up a model of how representational and interpersonal modifiers are progressively integrated into the overall NP structure, in an assembly that is largely from right to left in Present-day English. We will, therefore, concentrate on pre-nominal adjectival modifiers. [7] This will allow us to specify the basic ordering tendencies for the functions of adjectives relative to each other. It also enables us to specify the general conceptual profile (e.g. entity, property, deictic relation, etc.) of adjectives fulfilling these grammatical functions. Thus, predictions can be made about the types of polysemous meanings adjectives will manifest in different positions (see Section 10).

3 The common noun as (part of) the modified in relations with adjectival modifiers

In this study we will restrict ourselves to the functions fulfilled by adjectives in NPs with a common noun head. [8] Typically, the head will be a congruently used common noun, but it can also be a member of another class, for instance an adjective, coerced into a common noun reading, e.g. the rich, the poor (Quirk et al. 1985: 419–424). The head serves a representational function, designating the general type of entity, of which the whole NP depicts an instance. Langacker (1991: 144) stresses that the common noun head in a NP designates a “pure type” of entity, but the whole NP refers to instances of that type. Adjectival modifiers of the head are conceptually dependent elements sharing grammatical features with the head noun (Langacker 1987: 235–236, 309–310).

4 Classifier

4.1 Semantics

In the functional-structural tradition, classifiers are said to “subcategorize the head they modify” (Bache 2000: 235) and to be realized typically by a noun (e.g. steam train) or by an adjective whose meaning is functionally close to that of a noun (e.g. electric train). Classifiers are typically part of culturally or scientifically sanctioned subcategorizations, which imply the existence of other subtypes in taxonomies defined by a specific principle of classification. For example, the general type ‘train’ may be subclassified according to its source of power, with electric trains and steam trains as contrasting subtypes, or according to its speed and number of stops, with fast train and all stops train as contrasting subtypes. As the distinction classifier-epithet has been questioned (e.g. Scontras et al. 2017), the semantics of the classifier are in need of further specification.

We hold that, semantically, the classifier has to be understood in its relation to the common noun functioning as head. A common noun designates a “pure type”, as is shown in constructional environments featuring a mere common noun, such as compounds like train lover (Langacker 1991: 75), which means ‘lover of the type, not of an individual, train’. It takes a full NP to designate instances of the type, as in (4), where 17/some/Ø freight trains all refer to a set of specific instances of trains.

Last night 17/some/Ø freight trains were still waiting to enter the tunnel.

Hence, a classifier, we argue, adds subcategorizing specifications to the entity-type designated by the head, “restrict[ing] the denotative scope” of the head noun (Adamson 2000: 57). The meaning of classifier-head structures is computed compositionally. We propose that the integration of classifier and head results in what could be called a “composite noun”, [9] which, like a simple common noun, is the name of an entity-type. In classifier-head structures, adjectives do not designate qualities, and hence cannot be placed on a scale, e.g. *very electric train (see 4.2). Rather, they express semantic components that contribute to the conception of the entity-type, e.g. electric train ‘type of train powered by electricity’.

This semantic analysis has some similarities with, but also differs from, McNally and Boleda’s (2004) proposal that relational adjectives as in technical architect express properties of kinds. Like them (2004: 181), we view classifying adjectives as semantically nominal: in our cognitive-functional terms, they are part of a semantic structure representing an entity-type. Unlike them, we do not adhere to Carlson’s (2005) unified analysis of “kinds”, which subsumes both reference to the class by bare generic NPs, as in (5), and the “type” meaning of common nouns functioning as part of a NP with a determiner [10] as in (4) above. Reference to the class as such can be construed only by a bare plural NP, which, as argued by Carlson (1978: 33, 196) does not denote a finite set of instances, as shown by the impossibility of adding all to the bare generic in (5): *All Diesel and electric trains were invented somewhere around the 1950’s. On our analysis, bare generic NPs are full NPs whose semantics include both deixis and categorial semantics. The deictic force of bare generics arises precisely from the identifying force of its lexically predicated type specifications, which give direct access to the class, understood as “the class of things defined by the type specifications of the plural count noun”, e.g. diesel trains (Carlson 1978: 33, 196). By contrast, common nouns that function as part of a NP to indicate the type whose instances are referred to, have categorial meaning only. [11]

4.2 Grammatical behavior

In 4.1 we argued that classifying adjectives contribute semantic elements to the conception of a type of entity, and do not designate qualities (Bolinger 1967; Quirk et al. 1985; Bache 1978, 2000; McGregor 1997). The most direct grammatical diagnostic flowing from this is, in our view, the impossibility of degree modification. In the semantic structure of a classifier-head unit, no quality can be accessed whose degree can be modified on either an open or closed scale (Kennedy and McNally 2005, see also Section 5.2 below). For instance, the entity-type red wine delineates all red wines irrespective of their actual, individual degree of redness. Therefore, on its classifier reading, it does not accept any modifiers construing a change of degree of redness, as shown by the impossibility of adding very to the composite common noun in a [*very red wine] lover. Neither is closed scale degree modification by e.g. completely possible for a classifier – head unit, as illustrated by a *completely false heir. Note that if a modifier is used, it does not have the meaning of modifying the degree of the quality, but of assessing how exhaustively the type specifications cover the instantiation actually referred to, as in a completely white audience.

A second diagnostic is that classifiers cannot be separated from their head by other adjectival modifiers, be it a representational modifier (epithet), *an electric brand new train, or an interpersonal modifier such as a focus marker, *a steam mere train. [12],[13] The reason for this, we argue, is the close conceptual dependency of the classifier on the head noun: together they indicate the “intension” of the category of which the NP designates instances.

4.3 Structure

The conceptual compositionality of head noun and classifier motivates the composite modification structure formed by them. The noun is the conceptually independent head: train suffices to conceive of the entity-type in question (Langacker 1987: 235–236). Classifying modifiers are semantically dependent and select their heads: the classifiers steam and electric mean ‘powered by steam or electricity’ respectively and they add these meanings to the meaning of the head ‘train’. There is a relation of direct semantic composition between head and classifier, and the classifier is structurally a direct representational modifier of the nominal head. [14] It is a direct modifier of the head in that their integration yields a unit that is internally inseparable and names – like a simple common noun does – the entity-type instances of which the whole NP refers to. Figure 3 visualizes the modification relation between head and classifier with an arrow. The point that the classifier is a direct modifier is captured by surrounding the whole resulting composite structure with square brackets (Matthews 2014: 105).

Dependency structure: electric train.

4.4 Order relative to other functions

The close integration between head and classifier is reflected positionally: the classifier either occurs immediately in front of the head noun, e.g. false heir, [15] or – exceptionally – immediately follows the head, as in heir apparent.

4.5 Multiple classifiers

English NPs may contain two or more classifiers. Such sequences allow for two different basic interpretations (Bache 1978: 86; Vandelanotte 2002: 236), illustrated in (6) and (7). In (6) human and non-human designate two different subtypes of ‘signaling’. In (7), by contrast, only one composite subtype of ‘politics’ is designated, viz. the ‘left-wing republican’ type. At first sight, these semantic differences appear to correlate with the contrast between coordination (in 6) and subordination (in 7) between the two classifiers, with the former typically marked by an explicit coordinator. However, the picture is more complicated in examples like (8), in which the two classifiers are clearly coordinated, as marked by and, and yet refer to only one subtype of ‘politics’.

there is perhaps no sharp distinction between human and non-human signaling and between language and non-language

(Lyons 1977: 93)

At the time, he espoused the left-wing, republican politics of his father. (news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/536170.stm)

I spend [sic] three and a half decades of my life actively involved in republican and left wing politics

According to Bache (1978: 23), (6) and (8) have the same structure, viz. coordination between the adjectives, but a different reading, i.e. a distributive one in (6) and a non-distributive one in (8). Against this, we propose different structural analyses for the three types, in which structural and conceptual assembly match.

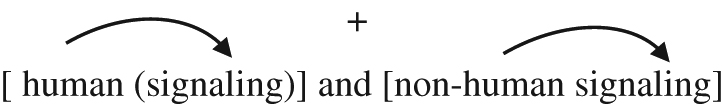

We propose that in examples involving two (or more) subtypes like (6), an elided head has to be posited following the classifiers that do not have an overt head: human and non-human signaling corresponds to the structure ‘human (signaling) and non-human signaling’, just as social, cultural or economic problems corresponds to ‘social (problems), cultural (problems) or economic problems’. There is coordination between the classifier-head units, rather than coordination between the classifiers as such. In sequences like these, the coordination is typically signaled at least once by a conjunction such as and, or, versus. The structural representation of the NP in (6) can be visualized as in Figure 4. Following Halliday (1994 [1985]: 219), we use the symbol “+” to represent the coordination relation.

Dependency structure: human and non-human signaling.

As noted by Bache (1978: 86), the word order of the classifying adjectives, which are always closely related semantically, is steered, but not absolutely determined, by morphological factors (heavier adjectives typically following lighter ones) and semantic factors (e.g. positives typically preceding negatives). Marked order offending against these tendencies, e.g. non-human and human signaling, does not affect the designation of different subtypes, but merely signals pragmatic differences relating to information structure and embedding in the discourse.

In examples like (7), left-wing republican politics, only one subtype is designated. The relation between the adjectives semantically involves recursive restriction: the NP in (7) refers to ‘republican politics’ of the left-wing type. We propose that they are structurally assembled in the following way. First, the classifier closest to the head, republican, integrates with the head noun, yielding the composite structure republican politics, which is the primary subclassification (Tucker 1998: 222). Then, the second, more leftward, classifier, left-wing, integrates with this composite structure, carving out the left-wing subtype of ‘republican politics’. This assembly is visualized in Figure 5.

Dependency structure: left-wing republican politics.

In this type, the order of the adjectives realizes the successive assembly of the modifier relations. The order codes the progressive restriction. Changing the order of the adjectives thus changes the propositional meaning. Classifiers inherently evoke the other terms of the taxonomies they are part of, and these taxonomies in turn tend to be ordered hierarchically in the cultures they are part of. Left-wing republican politics takes the implied contrast ‘republican – democratic’ as primary subclassification, and then delineates the secondary sub-classification of ‘left-wing republican politics’. A Google search yields 2530 instances of left-wing republican politics, but none of republican left-wing politics. This reflects the cultural entrenchment of the order of subclassification in this domain, and the semantic consequences of changing the order of the classifying adjectives.

Let us then turn to the third type exemplified by republican and left wing politics (8). The NP designates one subtype whose two subclassifying categorizations are represented as being on a par. We propose that in this structure type, the two classifiers form a coordinated unit, which as such modifies the head. The structure of this NP is represented in Figure 6.

Dependency structure: republican and left wing politics.

The semantic and structural composition of this type is clearly different from the other two types. More research is needed to identify the typical contexts in which this type is used. Example (8) is a context in which the juxtaposition of republican and left-wing, with the two categorizations and the coordinator stressed, is presented as somewhat surprising: republican and left-wing politics.

Importantly, all three structure subtypes feature the direct representational modification relation between classifier and head. Example (6) has coordination of the classifier-head units. Example (7) has progressive narrowing of the type specifications, with the more leftward classifier modifying the unit consisting of the most rightward classifier+head. In (8) the head is modified by the unit consisting of coordinated classifiers. A change in the order of the classifiers affects the subcategorization as such in the second type only.

5 Epithet

5.1 Semantics

The second representational modifier is the epithet. It differs from the classifier in that it does not narrow down the general entity-type denoted by the head, but ascribes a property to the instance referred to. This is an important semantic difference, as instances can manifest qualities differently, i.e. they are inherently located on a scale, either a closed or open scale (Kennedy and McNally 2005). Hence, it is when adjectives are used as epithets, i.e. ascribed to instances, that the basic semantic distinction between bounded and unbounded properties (Bolinger 1967 and Bolinger 1972; Paradis 1997; Paradis 2000 and Paradis 2001) comes into play. Bounded adjective meanings construe properties as associated with a boundary which has to be reached for the property to be present, as with the empty train cars in (9), but often they can also be construed as only approximating the boundary, e.g. an almost empty glass. Unbounded adjective uses invoke ranges on a scale and do not involve a boundary, e.g. red. If the property red is attributed to the specific instance of ‘dress’ in (10), then the notion of redness that is gradable on an open scale (‘very red’) is at stake.

They walked away from the empty train cars.

(WB)

I wanted to steer clear of black this Christmas even though it’s my favourite colour. I love this red dress.

(WB)

By contrast, with adjectives used as classifiers, e.g. red wine, false heir, (un)–boundedness is not semantically at issue.

5.2 Grammatical behavior

In the literature, two diagnostic tests for the identification of adjectives functioning as epithets have been pointed out, gradability and the predicative alternation.

Gradability is implemented in different ways depending on the bounded/unbounded distinction. With unbounded adjectives, which are inherently conceptualized as degrees, we find scalar modifiers, which change the designated degree, as in very red lips (11a). Bounded adjectives take either totality modifiers, which emphasize that the boundary has been completely reached, as in completely empty streets (12a), or proportional modifiers, which indicate how far the property is removed from the boundary, as in an almost empty glass (Kennedy and McNally 2005: 349–353).

Seigl was struck by how unnaturally white her skin was. A milky skin and very red lips.

(WB)

Her lips were very red.

(WB)

I … cycled through completely empty streets …

(WB)

The streets are completely empty…

(WB)

The proportionality between attribution by a prenominal epithet and predication of the subject has been recognized to be a crucial feature of the epithet in functional (Bolinger 1967 and Bolinger 1972; McGregor 1997; Bache 2000) and formal accounts (Larson 1998; Cinque 2010 and Cinque 2014) alike. We venture that it is precisely because epithets ascribe a property or state to the instances referred to that they can do this either by predicating on a subject NP or by premodifying a head noun. Predicated adjectives obviously ascribe properties to specific instances, viz. the referents of the subject NPs, such as her lips in (11b) and the streets in (12b). But the prenominal epithets in (11a) and (12a) apply to instances too: the NP in (11a) indicates that the lips of the woman in question are ‘very red’. Likewise, completely empty in (12a) applies to the specific streets the speaker cycled through. In sum, the distinctive grammatical behavior of adjectives used as epithets is motivated by the fact that they ascribe properties to instances. In the cognitive-functional tradition, this point has not been made explicitly. Whilst Langacker (1991: 144–148), for instance, stresses that the head noun designates an entity-type and the whole NP an instance, he does not indicate at which point in the structural assembly this shift from type specification to instantiation takes place. He associates instantiation with identifiers and quantifiers, which, he says, “presuppose” instantiation. He makes no difference between epithets and classifiers, which as modifiers he appears to associate indiscriminately with the general function of type specification. Against this, our position is that the designation of instances starts to be coded when epithets get assembled into NP-structure.

5.3 Structure

Structurally, the epithet functions as a representational modifier of either the head or the head plus any classifiers it may have. If classifiers are present they first integrate as direct modifiers with the head, yielding an internally inseparable structure dedicated to naming the subcategorizations that define the entity-type. The epithet integrates next with the type designation-part, but not in the same way as the classifier.

In the functional tradition, Dixon (1982 [1977]: 25) has characterized epithets as independent modifiers, whose specific nature comes most clearly to the fore when there are multiple epithets. Both a clever brave man and a brave clever man ascribe, irrespective of order, the properties of cleverness and braveness to the instance of ‘man’ in question (see Section 5.5 below). [16] By contrast, multiple classifiers, e.g. left-wing, republican politics (7), progressively narrow down the entity-type and order matters. The specificity of the epithet as a representational modifier is brought out by meta-grammatical glosses which associate it with the instance referred to, rather than the type designation:

a brave man: a brave instance of the type ‘man’

a brave military man: a brave instance of the type ‘military man’

a brave clever man: a brave and clever instance of the type ‘man’

The structural assembly of (13b) can be represented as in Figure 7.

A brave military man.

Adjectives fulfilling the epithet function can rather exceptionally and under specific conditions follow the head. Factors motivating this marked order appear to be mainly aspects of information structure such as end focus and end weight (Bache 2000: 236–237), as in They were military men brave and humble. Such postposed epithets are also independent modifiers that ascribe the properties in question, such as braveness and humility, without recursive narrowing to the instances of the type-designation, military men.

5.4 Order relative to other functions

The coding of epithets by independent representational modifiers determines the position of the epithet in the premodifier string. It occurs right in front of the head, in the case of a simple type designation, but in front of prenominal classifiers, in case of a composite type designation, as in the same unpleasant (epithet) congressional (classifier) procedure (head), cited in Table 1 above. Kotowski and Härtl (this volume) evaluate the epithet-classifier distinction, which they refer to as quality vs. relational adjectives. Their research provides empirical evidence that the order “quality before relational” is a core grammatical constraint.

5.5 Multiple epithets

As is well-known from the literature, one NP can contain multiple epithets. This issue is at the heart of many papers in this volume (see Trotzke and Wittenberg this volume). The main questions we address in this section are the following. Is the coordination-subordination contrast relevant to different types of sequences of multiple epithets? Are there other principles on the basis of which different types of epithet sequences can be distinguished? How do the main principles of ordering advanced in the literature (e.g. semantic, phonological) interact with different types of epithet sequences?

Vandelanotte (2002) proposes specific answers to these questions. Firstly, he distinguishes two types of epithet sequences based on the distinction coordinated vs. non-coordinated.

Then our hospitals will be an example to the world unprecedented in history: a pure, pristine, platonic form of hospital administration.

(WB, Vandelanotte 2002: 224)

I’m a Democrat and he’s a capable and knowledgeable and inspiring leader.

(WB, Vandelanotte 2002: 226)

I’ll watch out for your good-looking wealthy blond ex

(WB)

Memo mounds found in Africa and the Americas are strange small rounded sandy hillocks

(WB)

Examples like (14) and (15), which typically involve some overt mark of coordination like conjunction and or the use of commas, are analysed as coordinated sequences. It is to these coordinated epithets, Vandelanotte (2002: 229) argues, that Dixon’s (1982 [1977]) notion of independent modification applies, or Bache’s (1978: 20–22) explanation that “such adjectives separately modify the head of the construction”. This structural analysis is visualized by Figure 8.

Dependency structure: a pure, pristine, platonic form (Vandelanotte 2002: 229).

As to the main principles governing the order of epithets in this type, Vandelanotte (2002: 234) puts forth phonological principles such as Behaghel’s law of increasing constituents. In his quantified corpus study, about 75% of tokens of this type either complied with – the majority – or did not offend against this law.

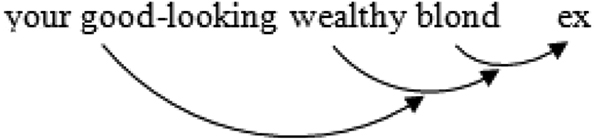

Examples like (16) and (17), in which the epithets are not linked by any overt mark, are analyzed as being subordinated to each other. To these allegedly subordinated epithets, Vandelanotte (2002: 238) applies an analysis of recursive modification, as in Figure 9.

Dependency structure: your good-looking wealthy blond ex.

For multiple epithets of this type, the law of increasing constituents did not apply in the majority of cases, but the semantic principles proposed in the literature did. More specifically, the order from more subjective to more objective epithets proposed by authors such as Quirk et al. (1972, 1985), Hetzron (1978), Dixon (1982 [1977]), Halliday (1994 [1985]) and Tucker (1998) applied in about 75% of cases. We summarize how the cline from more subjective to more objective relates to more specific semantic notions in Table 2.

Semantic subclasses in the cline from more subjective to more objective.

| more subjective | > | more objective |

|---|---|---|

| (individually) evaluative | (collectively) accessible | |

| momentaneous | permanent, inherent | |

| not potentially defining | potentially defining | |

| affective category, dimension, epithet, age, physical quality, color (Tucker 1998) | ||

For instance, in (16) the most leftward adjective, good-looking, is a matter of more subjective evaluation, while the property wealthy is more collectively assessable, and the color blond is the most objective, inherent quality of the referent. The epithets in (17) illustrate the order affective category>dimension>physical quality.

Vandelanotte’s (2002) corpus-based study reveals convincingly, in our view, that there are two types of multiple epithet sequences whose order is motivated by different factors. However, on reflection it seems to us that the distinction between the two types of sequences is not a matter of coordination versus subordination. A number of observations argue against the epithets in examples like (16) and (17) participating in recursive modification the way the two classifiers in left-wing, republican politics (7) do. As we saw in Section 4.4, with recursive modification, the first classifier of the head represents the primary subclassification, republican politics, to which the second classifier adds the secondary subclassification, left-wing within republican. If we cite such subcategorizations, the subordination is retained semantically and structurally, as illustrated by the following example which considers primary and secondary subclassifications in American politics.

Is ‘Right Wing’ Republican or Democrat? I don’t know how to answer this question I’ve heard people say ‘right wing democrat’ and I’ve also heard ‘right wing republican”.

(http://www.education.com/question/social-studies-wing-republican-democrat/)

By contrast, if we cite the epithets used in an example like (16), it is clear that there is no comparable relation of recursive modification between them. It does not make sense to consider whether the hearer’s ex is good-looking wealthy, or wealthy blond. We therefore conclude that the two types of epithet sequences both involve coordination and the structure of independent modification represented in Figure 8. This is consonant with Dixon’s (1982 [1977]) view that epithets are inherently independent modifiers, which we subscribe to.

The difference between the two types of epithet sequences lies instead, in our view, in different tendencies of information structuring, as reflected by their intonation when read aloud. It seems plausible that the two types are associated with different tendencies for the distribution of accents and the division into tone units (Halliday 1994 [1985]). If the epithets are separated by a coordinator or a comma, they are more likely to be individually salient, and they might get divided over more than one tone unit. Both these prosodic features reflect greater informational salience of the individual epithets. By contrast, if epithets are not separated by commas in writing, as in (16) and (17), this can be taken to signal that they will be accented less as individual items, and are more likely to be integrated into an overarching contour. This reflects lower informational salience of the individual epithets. Looked at in this way, the recognition criteria used by Vandelanotte (2002) to distinguish the two types of epithet sequences remain valid. Hence, the factors proposed by Vandelanotte (2002) as motivating order in the two types can be roughly maintained. The first type, in which the epithets tend to be given greater individual informational salience, has its order determined by phonological principles like the law of increasing constituents. The second type, in which the sequence as such tends to be prosodically integrated into the information unit, has its order motivated mainly by semantic principles that can be generalized over by the subjective-objective continuum (see Table 2).

6 Noun-intensifier

6.1 Semantics

Noun-intensifiers are interpersonal modifiers that always have scope over units containing a noun. Whereas representational modifiers add lexical, categorizing material to their head, noun-intensifiers qualitatively change the descriptive meaning of the unit they relate to, more specifically its scalar properties. For instance, in (19), pure intensifies the scalar features of the noun filth. Noun-intensifiers convey subjective speaker-assessment of descriptive features relative to scales (Ghesquière and Davidse 2011), which makes them attitudinal interpersonal modifiers in McGregor’s (1997: 211) terms.

Arthur, the things you say, some of them are pure filth, dirty, disgusting words

(WB)

6.2 Grammatical behavior

Noun-intensifiers, as in pure filth (19), do not display the behavior of the central adjective function, the epithet. They cannot themselves be measured on a scale, e.g. *very pure filth, (which is different from the coordination of noun-intensifiers discussed in 6.4). Neither can they occur as predicative adjectives on their own, e.g. *the filth is pure. The impossibility of these alternates can serve as diagnostics of noun-intensifiers.

6.3 Structure

In the structural assembly of the NP, the noun-intensifier is an interpersonal modifier of a unit that always includes the head (19–21), and may also include classifiers and epithets, as in (20). All three elements that can be found in its scope are representational elements.

It is pure cold racial abuse.

(paullinford.blogspot.com/2009/01/my-grandparents-cat-was-called-sooty.html)

Sad, utter stupidity all the way around. (https://www.ar15.com/archive/topic.html?b=1&f=5&t=1208296)

As noted by McGregor (1997: Ch. 6), the dependent-head model of representational modification does not really work for interpersonal modification. An interpersonal modifier is a “suprasegmental” element which relates to, and impacts on, a domain potentially consisting of several segments – a notion which is very appropriate for noun-intensifiers. This relation between the overlaying, molding element and the unit being changed is captured by boxed representations as in Figures 10 and 11 of Examples (20) and (21), which are integrated with the arrows representing representational modification. In Figure 10, the noun abuse is first modified by classifier racial. The entire type description racial abuse is modified by subjective epithet cold, and it is this composite structure that falls under the scope of the noun-intensifier pure. In Figure 11, noun-intensifier utter only has the noun stupidity in its scope. The epithet sad adds a further subjective property description: the (utter) stupidity is sad.

Dependency structure: pure cold racial abuse.

Dependency structure: sad, utter stupidity.

6.4 Order relative to other functions

Signaling the scopal domain the noun-intensifier applies to is essential to the meaning coded by a noun-intensifier, and this requires the noun-intensifier to be positioned precisely at one of the boundaries of the scoped over unit. Noun-intensifiers are almost always premodifiers in English. They then appear to the left of the whole unit they have in their scope, as illustrated by (19–21). This position is crucial to the interpretation of examples with multiple adjectives like (20–21). In (20), pure heightens the degree of cold, as well as of the gradable properties in racial abuse. In (21) the unit of noun-intensifier+noun is itself preceded by the epithet sad that is outside its scope. Very occasionally, noun-intensifiers may occur at the right end of the descriptive material in their scope, i.e. following the head, as in (22), where, as a result, it is unclear whether virtual stupidity, or only stupidity, fall in the scope of complete (22).

BEAVIS AND BUTTHEAD VIRTUAL STUPIDITY COMPLETE. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4BmZ98tTzU)

6.5 Multiple noun-intensifiers

In contrast with classifiers and particularly epithets, multiple noun-intensifiers are typically restricted to two. In such sequences the noun-intensifiers are coordinated: the intensifier to the left does not submodify the noun-intensifier to its right, but the two together modify the unit in their scope. Figure 12 represents these structural relations for the NP in (23).

Dependency structure: pure dead big superstars.

Pure dead big superstarslike the Wheel of Fortune Prize Guy

(WB)

What an utter utter dump!

The semantic effect is to further heighten the degree of the scalable properties inherent in the scoped over material. In (23), pure dead very strongly heightens the gradable features inherent in the unit big superstars consisting of epithet+noun. To achieve strong upscaling of the gradable features in the representational unit, it is also possible to repeat the same noun-intensifier as in (24).

7 Secondary determiner

7.1 Semantics

Semantically, adjectives realizing the secondary determiner function do not describe the referent of the NP, but have a reference-oriented function (Bolinger 1967). They add information to the meaning expressed by the primary determiner with the aim of making the identifiability status of the referent more precise. Secondary determiners further specify deictic or discursive relations (Davidse et al. 2008).

In Example (25) the combination of the indefinite article a and different specifies that a new instance of the type ‘girl’ is involved on every occasion: each time the speaker is with a different girl, in the sense of another girl. As argued by Breban (2002/2003), secondary determiners convey general grammatical, viz. determining, meanings, in this case, non-coreferentiality. In the case of another, the univerbation of an and other orthographically signals the unit status of primary and secondary determiner. We can contrast this secondary determiner use with the referent-describing use of different in (26), where it functions as epithet and attributes very different personality traits to Gemma than to Nicola. Example (27) contains secondary determiner identical, which indicates identity of reference. [17] The primary determiner the signals that the referent is presumed known, and identical explicitly marks the point that the fence which caused the fall of One Man is co-referential with the one that caused the fall of Wild Orchid. Hence, identification is possible (the) and the identifying mechanism is co-referentiality (identical). The identical in (27) has the same referential meaning as the same (whose equivalents in Dutch, dezelfde, hetzelfde and German, derselbe, dieselbe, dasselbe are univerbated).

I thought about how corrupt I was, always wanting to be drunk or stoned, always with a different girl.

(WB)

As is usually the case, Gemma is turning out to be a very different girl than Nicola. (www.igs.net/~jonesb/xmas04letter.htm)

Ironically, One Man’s fatal fall came at the identical fence which caused the retirement of another great grey, Wild Orchid.

(WB)

Determiner complexes (units of primary and secondary determiner), like simple determiners, determine the instance or set of instances referred to (Halliday 1994 [1985]: 183). We view determiners, be they simplexes or complexes, as interpersonal modifiers, which semantically have the whole nominal referent in their scope. By their choice of determiner the speaker assigns a cognitive status to the referent which will allow the hearer to track that referent in the discourse. Breban (2010a) has argued that the meaning of determiner units is textually intersubjective, because they are used by speakers to introduce and track referents in the discourse in a way that takes into account the hearer’s knowledge (2010a: 115–117).

7.2 Grammatical behavior

The grammatical behavior of secondary determiners is that of peripheral, rather than central, adjectives. As a number of adjectives, e.g. different, can be used as either secondary determiners (25) or epithets (26), we can contrast the different syntactic behavior motivated by the meaning differences. In (26) different is used as an epithet: it is graded on an open scale by very and can be predicated of the subject with the same sense: Gemma is very different from Nicola. In (25), by contrast, different cannot be graded and cannot be used predicatively: I was always with a girl that was very different conveys a different meaning.

In Section 5.2, we saw that epithets cannot enter the unit consisting of head and classifier(s). In parallel fashion, epithets cannot enter the unit formed by the primary determiner and secondary determiner(s). Whether an adjective really is a secondary determiner can thus be tested by checking whether it resists insertion of an epithet in front of it. Consider the following two examples.

DeLancey pointed out that the difference between (66a) and (66b) does not concern the difference in certainty. The former example … (https://books.google.co.uk/books?isbn=9027250618)

He had to watch his former colleagues become consultants while he trained for something else.

(WB)

In (28) we cannot insert an epithet: *the unclear former example is not possible, but the former unclear example is. In (29), by contrast, an epithet can separate former from colleagues, e.g. his ambitious former colleagues. This shows that it is only in (28) that former functions as secondary determiner: it instructs the reader to identify the example in question with the referent of the NP closest to it in the preceding discourse. By contrast, former in (29) assesses the relation between the referent and the designation colleagues: the designation colleagues applied to the referents in question only in the past of the character referred to by he (Breban and Davidse 2016b). We refer to this latter function as metadesignative and discuss it in more detail in Section 9. Existing lists of secondary determiner adjectives (e.g. Halliday 1994 [1985]: 183; Sinclair 1990: 70; Bache 2000: 241; Davidse et al. 2008, Breban 2010b) do not always distinguish them properly from metadesignatives: they include adjectives such as future and old, which can be used only as metadesignatives, and polysemies such as just discussed for former in (28–29) are not noted.

7.3 Structure

In this section we broach the structural issues associated with the secondary determiner, both the relation of the whole determiner complex to the rest of the NP, and the relation of the secondary to the primary determiner. With regard to the latter, a distinction has to be made between complex determiners, which are basically compounds, and determiner complexes, which have internal structure (see Breban 2010b).

Payne and Huddleston (2002: 391) argue convincingly that another forms one compound determiner. We propose that univerbation as such is not the only criterion to assign this status – although it helps show up compound status – but also grammatical behavior and meaning. Thus, we propose a compound determiner analysis not only for another, but also for the same, and their functional-structural equivalents such as a different (25) and the identical (27). Semantically, their two components share many meaning elements. For instance, in a different girl in (25) (‘another girl’), the newness signaled by a is semantically restated, i.e. clarified and refined, by different. Likewise, in the identical fence in (27) (‘the same fence’), the meaning of co-referentiality is expressed by both the definite article and identical, which emphasizes the co-referentiality. The compound determiners another and the same are internally inseparable (that is, if other and same have determinative, not representational meanings). We venture that, in their complex determiner uses, a different and the identical are also internally inseparable.

Determiner complexes, by contrast, consist of more freely combinable elements and have internal structure that codes different compositional meanings. This is particularly clear with contrasting examples such as the two other candidates versus another two candidates, whose internal structure is discussed in Section 7.5.

As a unit, the determiner – be it a simplex or a complex – is the last layer to integrate into the NP’s composite structure (Langacker 1991: 432). It is the most grammatical and semantically most abstract element in the NP (Langacker 2002: 9–13; Langacker 2004), that is, it integrates with the head noun and any other modifiers the head may have. For the semantic reasons set out in 7.1, we view determiners as interpersonal modifiers. We can represent the structure of a different girl (‘another girl’) in (25) as in Figure 13.

Dependency structure: a different girl.

7.4 Order relative to other functions

The whole determiner unit is an interpersonal modifier, indicating the referential status of the noun phrase referent. The unit has scope over the entire NP, which is reflected by its position at the uttermost left end of the NP. Internal to the determiner complex, secondary determiners may either immediately precede or follow the primary determiner, that is, they may be pre- or postdeterminers. Typical predeterminers are such/what (a), double/half/all (the), etc. Postdeterminers are the unmarked option in that they represent the more common order, and have a broader distribution, including the possibility of accommodating multiple postdeterminers (Section 7.5).

Order relative to other functions has been invoked as a recognition criterion. Halliday and Hasan (1976: 160) hold that position relative to numeratives shows up the status of postdeterminer or epithet of polysemous adjectives. They hold that if the adjective precedes the numerative it is a postdeterminer, whereas if it follows the numerative it is an epithet, as in (30–31).

Against this, we (Breban and Davidse 2003: 284–285) hold that such polysemous adjectives can be either postdeterminer or epithet when they follow a numerative, with the context often disambiguating the two possible readings. In (32) different stresses that two different instances of ‘boys’ were involved, whereas in (33) different ascribes different qualities to the two towers of Chartres cathedral. When these polysemous adjectives precede a numerative, as in (34), they are indeed always a secondary determiner in the sense of functioning within the determiner complex. We consider sequences with multiple secondary determiners like (34) in Section 7.5 below.

I slept with two different boys just after I broke up with my boyfriend.

(WB)

Part of the charm of Chartres is its two different towers — the simple, early Gothic spire on the south and the more flamboyant late Gothic design on the north

Madonna and Mick Jagger get by with a different two out of the three [charisma, sex appeal and glamour]: sex appeal and glamour.

(WB)

We conclude that secondary determiners form a composite unit with the primary determiner, which is positioned at the extreme lefthand side of the English NP. Representational modifiers and quality-intensifying modifiers are barred from occurring in this unit.

7.5 Multiple secondary determiners

Determiner units may contain multiple reference-oriented elements, between which relations of coordination or subordination may obtain. Without claiming to cover all possible cases, we will look at these two structural possibilities, which are motivated by different scopal relations. Again the difference between compound determiners versus determiner complexes is crucial.

Firstly, compound determiners stressing identity of reference may be intensified in two ways, either by two coordinated secondary determiner adjectives, as in (35), or by submodifying the secondary determiner, as in (36).

Roberta [Wallach], Rebecka Ray and Sidney Williams have opened in Robert Glaudini’s “The Identical Same Temptation”

(WB)

a poll reveals that 66% of company chief executives are now against Britain joining the euro. It wasn’t that long ago that the very same people were warning we would go down the pan if we did not join the euro.

(WB)

The determiner units in (35) and (36) can be visualized as in Figures 14 and 15. In Figure 15, very, as an intensifier of same, is an interpersonal submodifier, and the relation with its scopal domain has to be represented separately.

Dependency structure: the identical same temptation.

Dependency structure: the very same people.

Secondly, in determiner complexes containing a numerative and a secondary determiner like other, different, same, the position of the secondary determiner is motivated by scopal relations, yielding differing interpretations for different orders.

Scotland Yard says two letter bombs have been intercepted at the House of Commons … Police are also investigating two other letter bombs.

(WB)

she decided to try standing up. That took her several minutes, even using the wall for support. Then it took another five minutes to bend down again

(WB)

In (37), two has scope over other, which in turn has scope over letter bombs. The interpretation of the NP in (37) is that new instances of the type ‘letter bombs’ are introduced. Other is an anaphoric marker pointing back to the type specification letter bombs. Two then provides the quantitative measure for this newly introduced set. Other and two are both modifiers agreeing with the head in terms of plural number. In the progressive assembly of the NP, other is first integrated with letter bombs, and two then integrates with other letter bombs. Figure 16 visualizes this structural assembly. In (38), by contrast, another has scope over five only and signals that a quantity of five is added to the already mentioned quantity several. As an anaphoric marker another points back to the quantity several. The questions probing the quantities in the two examples reveal the different meanings. In (37) two answers the question How many other letter bombs are there?, while in (38) How many minutes did it take to bend down again? is answered by Another five. In this example, only five is a modifier of minutes, not another, which is singular. We therefore analyze another as an interpersonal modifier of five only, as visualized in Figure 17.

Dependency structure: two other letter bombs.

Dependency structure: another five minutes.

8 Focus marker

8.1 Semantics

Adjectives used as focus markers in the NP serve a semantic function similar to adverbs such as only, even, just. They are interpersonal modifiers by which the speaker situates the focus value in relation to alternative (implied) values, which contrast with the focus value or are situated on a shared scale. For instance, in (39), the sight of a dentist’s chair is positioned on an implied mirative scale (DeLancey 2001) as a very surprising value to inspire fear (in contrast with, for instance, actually being in the chair). This is a case of inclusive focus (‘even’), as a highly surprising value is focused on, which also evokes and includes all the less surprising values on the mirative scale. The announced tune-in is recommended for all those who are afraid of dentists: those who are afraid even at the sight of a dental chair, as well as, by implication, those who are afraid when they actually are in the chair, etc. In (40), four is positioned as a lower value on a quantitative scale than the longer period of time needed. The focus is exclusive here: ‘into only four hours’. In (41), Margaret Thatcher’s position in 1977 is characterized as ‘nothing more than’, i.e. only, leader of the Conservative party. The focus is exclusive and contrasts with the implied category ‘Prime Minister’, the status which Thatcher had not yet reached in 1977.

Anyone who freezes with fright at the mere sight of the dentist’s chair will be pleased to know that you can now tune into something … more relaxing than a screeching drill.

(WB)

… you can imagine how hard it proved to cram 12 whole quatrains into a mere four hours.

(WB)

Mrs Thatcher was mere leader of the Conservative opposition at the time

(WB)

In McGregor’s terms (1997: 211), the semantic function of focus markers is rhetorical: they “indicat[e] how the unit fits into the framework of knowledge and expectations relevant to the interaction”. They put focus values in contrasts or on scales in ways that seek to involve the hearer in building common ground, or go against hearer expectations. Focus markers are thus one of the means by which speakers can incorporate propositions and evaluations into the shared beliefs, knowledge, expectations, and presuppositions of speaker and hearer (McGregor 1997: 222). As focus markers “crucially involve SP/W’s [speaker/writer’s] attention to AD/R [addressee/reader] as a participant in the speech event” (Traugott and Dasher 2002: 22), we hold that their meaning is intersubjective.

8.2 Grammatical behavior

Adjectives used as focus markers obviously do not manifest the behavior of central adjectives: they do not designate a quality located on a scale, and cannot be expressed as predicates. An alternation that adjectival focus marker uses tend to display is with focusing adverbials, i.e. Quirk et al.’s (1985: 604–612) “focusing subjuncts”. All three examples quoted above have counterparts with focusing merely, which reveal the different scopal domains, as discussed in Section 8.1.

Anyone who freezes with fright at merely the sight of the dentist’s chair

To cram 12 whole quatrains into merely four hours.

Mrs. Thatcher was merely leader of the Conservative opposition at the time

8.3 Structure

The questions to be answered concern the different NP-units an adjectival focus marker can relate to, and at which stages of the structural assembly of the English NP these specific interpersonal modifiers come in.

Adjectival focus markers share two of the types of units they scope over with secondary determiners, viz. the whole NP referent, as in (39), and a numerative, as in (40). These interpersonal modifier relations are visualized in Figures 18 and 19. Adjectival focus markers can also scope over units that secondary determiners cannot scope over, viz. components relating to the representation of entities. In (41) above, the scopal domain of mere is formed by the determinerless predicate nominative leader of the Conservative opposition which designate a “pure type” (Langacker 1991: 69). In an example like (42), mere also has only the entity-type designated by muggle in its scope.

Dependency structure: mere leader of the conservative opposition.

Dependency structure: a mere four hours.

FOR a mere muggle like me this film is a magical mystery tour through the world of Harry Potter.

(WB)

8.4 Order relative to other functions

Focus markers typically occur in front of the material they have scope over, as illustrated by (40)–(42) above. The one exception is when they have scope over the whole nominal referent. They then appear in postdeterminer position, as in the mere sight of the dentist’s chair (39).

8.5 Multiple focus markers

As with noun-intensifiers (see Section 6.5), multiple focus markers are typically restricted to two, with a relation of coordination obtaining between them. The semantic effect is to heighten the focusing operation such as the inclusive focus in (43).

Those are the simple and pure facts, but there is a lot more that goes on in the background.

(WB)

9 Metadesignative

9.1 Semantics

The final function that can be realized by adjectives [18] is the newly distinguished function that we refer to as “metadesignative”. We understand this function as an interpersonal modifier by which the speaker assesses the relationship between (parts of the) designation and referent. We chose this term because “designation” is generally accepted to refer to both proper names and lexical elements such as common nouns and adjectives, and metadesignatives can be used with both. As put forward by Frege (1892), [19] two different aspects of the significance of linguistic elements have to be distinguished: 1) reference or denotation, i.e. the relation to the entity referred to, 2) sense, i.e. the mode of representing entities. Using a metadesignative involves taking a distance from the referring and/or representation relation between a linguistic element and the referent in order to comment on it. With proper names, the relation between name and referent can be commented on, for instance, by indicating that the referent is the true bearer of the name, as in true God. With lexical elements such as common nouns and adjectives, the relation between mode of representation (i.e. type specifications and qualities) and referent can be commented on. Because senses are made to apply to multiple actual referents, various sorts of discrepancies between sense and entity may occur. In the first place, the precision of the match can be commented on: the fit of the referent to the designation, the strictness which the categorization applies with, or the appropriateness of the linguistic designators used. The referent can, for instance, be judged a worthy or non-worthy instance of the type designated by the head noun, as in a true friend versus a so-called friend. Other discrepancies between the designation and the referent that may be indexed by metadesignatives are temporal, modal or evidential relations. For instance, in Jordan’s future king it is indicated that the category king will apply to the referent in the future only. In the likely winner and his alleged murderer the metadesignatives indicate that the categorization is epistemically likely to be the correct one, or is so only according to hearsay.

Metadesignatives seem, as a general category, to be absent from descriptions of the English NP, even though some specific instances have been discussed, e.g. so-called (McGregor 1997: 267; Vandelanotte 2002: 248–251). In functional approaches, metadesignatives have tended to be conflated with, and subsumed under, secondary determiners (e.g. Halliday 1994 [1985]; Sinclair 1990; Bache 2000; Davidse et al. 2008, Breban 2010b). This may be for a number of reasons. Firstly, they clearly do not have representational meaning. [20] Secondly, metadesignatives with temporal and modal meaning invoke the deictic coordinates of the speech event, which determiner complexes do too, e.g. the former example (see Section 7.2). However, metadesignatives do so not to more precisely determine the referent, but to comment on the relation between designation and referent. Thirdly, they often follow the determiner, as in all the examples quoted above, which contributed to the perception of their being “post-determiners”. However, as we saw in Section 7.2, metadesignatives can, in contrast with secondary determiners, be separated by epithets from the determiner, as in Jordan’s handsome future king. We return to this issue in Section 9.4 below.

9.2 Grammatical behavior

Metadesignatives do not function as central adjectives: their meaning cannot be measured on a scale (*the very future king), and they cannot be constructed as predicates (*the king is future). This is also pointed out by Cinque (2014), who views adjectives as in a possible (‘potential’) candidate as direct modifiers, like classifiers. As argued in Section 4.3, we analyze classifiers as direct representational modifiers, but metadesignatives as interpersonal modifiers.

9.3 Structure

The two units involved in the interpersonal modification relation are the metadesignative and the representational unit it has in its scope. This relation fits into the structural assembly of the whole NP in terms of where the unit being modified comes in. For instance, in Jordan’s handsome future king, future functions as metadesignative of king. The epithet handsome is a representational modifier, which expands the head. With the resulting composite structure, the determiner Jordan’s is integrated as the final structural, interpersonal, layer. The assembly is visualized in Figure 20.

Dependency structure: Jordan’s handsome future king.

9.4 Order relative to other functions

In terms of the positions that metadesignatives can take up in the NP, they differ from both secondary determiners (as noted in Sections 7.2 and 9.1) and noun-intensifiers. Metadesignatives are banned from occurring in the determiner complex (*the former following user is not a possible alternative of the NP in (44)), but they can relate to all representational functions. Whereas noun-intensifiers basically relate to the head, or to composite units in which the head is expanded with representational modifiers, metadesignatives can apply to all three representational elements in the English NP (nominal head, classifier and epithet) in combination but also in isolation. In pure industrial banks, it is stressed that the classifier industrial applies strictly. In a so-called “good” death, metalinguistic attention is drawn to the epithet good, for instance to convey that the meaning associated with good is not its default sense, but a qualified one such as ‘involving as little pain as possible’. Metadesignatives can also scope over combinations of classifier and head (45), and epithet and head (46), just as they can apply to the head only with preceding classifier (47) or with the epithet (48) falling outside of its scope. For instance, in (45) former indicates that the classifier communist and the categorization societies of Eastern Europe applied to the referents in the past, but not anymore at the time of speaking (they are no longer communist and some of the country boundaries have been redrawn). In (47), by contrast, the classifier Marxist still applies to the referent but no longer the categorization mayor of Lima.

Thus, there is always the problem of temptation, as the following former user pointed out

(BNC)

there is a complex “crisis of legitimacy” … in the former communist societies of Eastern Europe

(BNC)

The contrast between her hand-to-mouth existence in Cochabamba and the former vibrant activist who inspired people all over the world was very striking.

(BNC)

If he fails to gain an outright majority the Marxist former mayor of Lima, Alfonso Barrantes, might win the second round.

(BNC)

The Peking Daily, […], accused the disgraced former leader of trying to turn the party into little more than a “social club”; shorn of power.

(BNC)

These examples show that the metadesignative’s position right in front of the left boundary of its scopal domain is essential to its delineation of that scopal domain. (The identification of the right boundary of the scopal domain may be a matter of context and world knowledge.) Finally, it can also be noted that metadesignatives occasionally occur in postmodifying position, as in the city proper.

9.5 Multiple metadesignatives

Multiple metadesignatives are not common but not non-existent either. Coordinated metadesignatives, which emphasize the speaker’s assessment, as in a true true friend have been a feature of English from its early stages on, as in (49).

our most dradde soverayne Lorde Kynge Hary the syxte, verrey trueundoutyde Kynge of Englonde and of Fraunce

(The Warkworth Chronicle, Part V, 1483, http://www.r3.org/links/to-prove-a-villain-the-real-richard-iii/these-supposed-crimes/warkworths-chronicle/part-v-warkworths-chronicle/)

10 Concluding discussion

In this article, we have elaborated our view on structure, functions and order of adjectives in the English NP. We set out to reveal the structural-functional relations that motivate and restrain the order of adjectives. The model proposed makes certain predictions for language use (synchrony), as well as for language change (diachrony).

The synchronic predictions hinge on mappings between meaning and (relative) position. As we made clear in this article, these mappings are not arbitrary. Rather, structural combinatorics code the specific semantic contribution an adjective makes in a particular NP: the semantic function it has and which other meanings in the NP it applies to. The position of any adjective is hence determined by its meaning in context.

A first consequence of this is that adjectives that are polysemous, i.e. that can have different functions in the NP, are also attested in multiple relative positions in the NP. Example (50) illustrates this for the adjective soft: in the first NP in bold soft is used as a classifier denoting a type of cheese, soft cheeses as opposed to hard cheeses. In the second NP in bold, describing a different cheese, Pencarreg, soft is the first in a series of adjectives, soft Welsh organic. The function of soft is not to specify the type of cheese. The head noun Brie already incorporates that type specification as it is a subtype of soft cheese. Instead, soft attributes the quality of being soft to this particular brie. The same epithet meaning of soft occurs a second time in the comparative as a predicate, it is softer. This excerpt thus illustrates the connection between meaning and position.

Milleensis an Irish soft cheese with a washed rind, similar to Port Salut. It is clean and fresh, although well flavoured. Pencarreg is a soft Welsh organic Brie, made from unpasteurised milk, so has a full flavour. Single Gloucester is another traditional cheese that is enjoying a revival. It should be made from just the morning milk taken from Old Gloucester cows. It is softer and milder than Double Gloucester and, although it tastes creamy, is relatively low in fat.

(BNC)

A second consequence is that adjectives can take up different positions depending on which – simple or complex – unit they modify. We illustrated this in several sections above, including those on noun-intensifiers (pure filth vs. pure cold racial abuse), secondary determiners (two different boys vs. a different two), focus markers (mere leader of the Conservative party vs. a mere four hours), and metadesignatives (the former communist societies of Eastern Europe vs. the Marxist former mayor of Lima). These different possible positions cannot be explained in a model that invokes only semantic classes, out of context. Attested examples of multiple positions for one specific adjective provide evidence for the two aspects of our analysis: one adjective can make different functional contributions and these contributions can interact in different ways with other units in the NP. Our analysis highlights that it is not possible to posit a single fixed ordering pattern – neither at the level of individual adjectives nor at the level of functions. In particular, the four interpersonal functions, noun-intensifier, secondary determiner, focus marker and metadesignative, each allow in their own way for differing scopal domains, and thus for different positions relative to the other functions. We thus need a flexible model that allows functions to be realized in different positions depending on the modification relations in context. Figure 21 is an attempt at visualizing the main ordering possibilities of prenominal adjectives in the NP in Present-day English. [21]

Visualization of the different possible relative orderings (SD=secondary determiner, NI=noun-intensifier, FM=focus marker, MD=metadesignative).

Diachronically our model predicts paths of functional changes affecting adjectives, viz. the different relative positions they move to and the meaning shifts that are involved. Many diachronic studies have charted systematic patterns of polysemy, and functional layering (Hopper 1991: 22), manifested by adjectives. This sort of polysemy has been well covered for the shift from epithet to noun-intensifier, as illustrated by terrible murder – terrible idiot, pure voice – pure passion, e.g. Bolinger (1972), Paradis (2000), Paradis and Wilners (2006), Kennedy and McNally (2005), Vandewinkel and Davidse (2008), Ghesquière and Davidse (2011), Ghesquière (2014). However, study of the shift from epithet to secondary determiner has been more patchy, e.g. Breban (2008, 2010a, 2014), Breban and Davidse (2003, 2016a), Davidse et al. (2008) and the shift from epithet to focus marker and metadesignative has been barely broached (Davidse and Ghesquière 2016; Breban and Davidse 2016a and Breban and Davidse 2016b).