Abstract

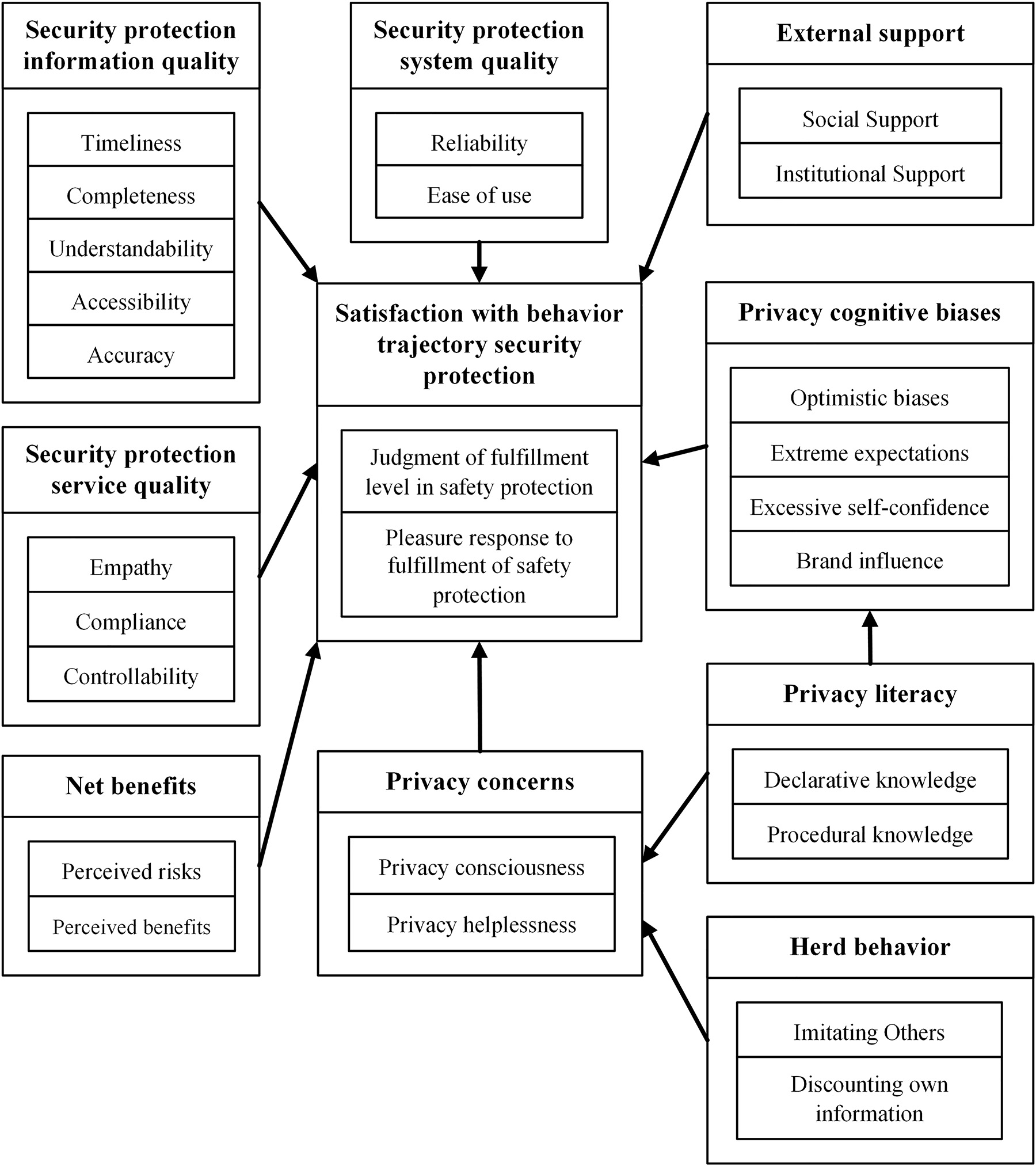

Intelligent recommender systems provide personalized recommendation for users based on their behavior trajectories. Intelligent recommendation is a double-edged sword with increasing impacts. This study investigates the influencing mechanism of social media users’ satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection in the context of intelligent recommendation, with the aim of promoting healthy development of mobile social media. This study applied the grounded theory method to identify relations among concepts and categories in terms of three-level coding. During open coding, 271 initial concepts and 26 subcategories were elicited; during axial coding, 10 categories were elicited; and during selective coding, relations among categories were identified and a theoretical model was developed. The results indicate that satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection is directly influenced by security protection information quality, security protection system quality, security protection service quality, net benefits, external support, privacy concerns, and privacy cognitive biases. Privacy literacy has direct impacts on privacy concerns and privacy cognitive biases. Meanwhile, herd behavior directly impacts privacy concerns. Implications for theory and practice are discussed.

1 Introduction

In the era of social media and big data, prolific content is generated by users (Naab and Sehl 2017), often in the form of unstructured data (Miah et al. 2017). As a result, users are frequently confronted with challenges including information overload (Fu et al. 2020), as well as cognitive load (Barabas 2023; Islam et al. 2020). With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, intelligent recommender systems have subsequently become increasingly prevalent (Wang et al. 2020). On mobile social media, intelligent recommender systems have increasing impacts on users. Intelligent recommender systems provide personalized recommendation based on behavior trajectories such as browsing, seeking, commenting, reading and etc., as well as geographic location information. Intelligent recommendation is likely to reduce information overload on the one hand, while on the other hand, it brings new issues such as behavior trajectory privacy concerns and users’ unsatisfaction.

Mobile intelligent devices possess high stickiness and portability, thereby generating abundant and sensitive behavioral trajectory information of mobile social media users. The prominence of social media platforms in providing information services is rapidly increasing and, concurrently, the ethical conflicts associated with the data underlying these services are becoming more evident (Häußler 2021; Keshavarz, Norouzi, and Shabani 2022). Personal information protection complaints and reports in China are increasing at an alarming rate, illustrated by issues such as the excessive collection of personal information, mandatory or frequent requests for permissions, and the inability to cancel an account accounting for approximately 40 % of the total complaints in 2021 (CNCERT/CC and CSAC 2021). Later, 19.6 % of Chinese netizens encountered personal information leaks during internet use in the second half of 2022 (CNNIC 2023). Furthermore, widespread application of intelligent recommender systems adds new challenges to security protection of behavior trajectory. Behavior trajectory of mobile social media users includes the traces generated by users’ behavior in physical and digital environments, as well as historical behaviors such as browsing, clicking, searching, private messaging, sharing, jumping, clipping, pasting, and other interactive behavioral traces within and across applications. Geographic location traces contained within location services or disclosure of information are also part of a user’s trajectory. Trajectory determines the content of specific user behavior, linked to user security and user privacy. In the context of intelligent recommendation, and based on the manifestation of social media users’ behavior trajectory, the following research questions guided the current study: Are users satisfied with the security protection of their own behavior trajectory? How does this satisfaction manifest? What factors affect this satisfaction and how do they affect? We believe user satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection in the context of intelligent recommendation is a critical issue, yet it has been overlooked in prior literature. The current study answered these questions, with the aim of promoting healthy growth of mobile social media platforms in the context of intelligent recommendation.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Intelligent Recommendation and Trajectory Information

Intelligent mobile terminal devices are becoming increasingly sophisticated in their functions, and operating systems are constantly improving their ecosystems, allowing for a wider range of collectable data. In addition to having access to user privacy data such as their locations, posted posts, and social relationships, social media platforms capture, mine and analyze historical user behavior data. This is done through the use of machine learning tools and algorithms to provide users with personalized recommendations and search predictions that optimize recommendation algorithms (Ge and Persia 2019; Lai and Zheng 2015). To fulfill the needs of intelligent recommendations, the recommender systems collect data within the application and capture switching and sharing activities across applications. In addition, this also acquires cross-application information including application data list and clipboard usage (CNCERT/CC and CSAC 2021). While privacy-related academic achievements recognize users’ trajectory information in the mobile environment, most current research (Al-Hussaeni, Fung, and Cheung 2014; Dai et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2021) primarily focuses on the physical location aspect of such data, with little attention given to the privacy implications of trajectory data related to digital interactions. In fact, each virtual interaction in the context of intelligent recommendation can generate vast amounts of data encompassing space, time and behavior trajectory, underscoring the critical need for privacy protection.

2.2 Privacy and Security Protection on Social Media

Research on privacy and security protection for social media users has explored several aspects. Regarding the impact of security and privacy protection on user behavior, it concerns privacy paradox in the engagement of consumers with social media and their behaviors related to online privacy protection (Mosteller and Poddar 2017), how trust, privacy and security affect individuals’ utilization of the internet for social media and online shopping (Alshare, Moqbel, and Al-Garni 2019), and the effects of regulatory focus and default on the preference settings of social media users (Cho, Roh, and Park 2019). Regarding the impact of user behavior on security and privacy protection, it concerns the impact of user behaviors on privacy and security threats on social media (Cengiz, Kalem, and Boluk 2022), and the influence of behavior on the security of privacy information on social media (Liu et al. 2022). Regarding countermeasures for security protection, it concerns privacy risks and possible threats on social media, methodology for privacy issues, and trust management (Kumar, Saravanakumar and Deepa 2016). Regarding users’ confidence in security protection and evaluation criteria for security protection, it concerns how to evaluate the level of user confidence in the security and privacy of social media (Ranogajec and Badurina 2021) as well as how to develop a cross-cultural framework to enhance user privacy protection on social media (Ur and Wang 2013).

2.3 Social Media User Satisfaction

Researchers have investigated social media user satisfaction. Yang et al. (2020) used structural equation modeling to analyze the effect of presentation, content, and utility on the satisfaction levels of users who interacted with the official social media platforms of Chinese government. Pang (2021) conducted an online survey of WeChat users and found that hedonic and utilitarian values positively and significantly influence user attitudes and satisfaction of the platform, with satisfaction having a significant impact on eWOM participation. Additionally, utilitarian values indirectly impact eWOM participation through satisfaction. Khan et al. (2023) explored user satisfaction with social media using the Expectancy-Confirmation Model and found that privacy cynicism substantially impacts user satisfaction. Other research explored user satisfaction in different areas within social media, including tourism (Balbi, Misuraca, and Scepi 2018; Martínez-Navalón, Gelashvili, and Saura 2020; Narangajavana Kaosiri et al. 2019), logistics (Alshehri and O’Keefe 2019), and daily life (Uram and Skalski 2022).

3 Research Method and Data Collection

3.1 Research Method

The grounded theory method could derive theoretical explanations based on data through induction (Glaser, Strauss, and Strutzel 1968; Guetterman et al. 2019). It is a widely used qualitative research method (Timmermans and Tavory 2012) that has been applied in various studies on privacy and security (Foley and Rooney 2018; Gerlach et al. 2019). This study employed grounded theory to investigate the factors that influence the satisfaction of mobile social media users with the security protection of their behavior trajectories in the context of intelligent recommendation. To facilitate the organization and analysis of textual data and to fully record operational traces, the NVivo software was used for coding (Maher et al. 2018).

3.2 Design of Interview Outline

A semi-structured approach was used in this study to ensure the effectiveness of the interviews. Prior to conducting the interviews, a preliminary interview outline was formulated based on initial literature review, phenomena observation, and relevant research experience. Pilot interviews were conducted with several social media users including both senior and junior ones and, based on their feedback, the interview outline was improved. The final formal interview outline covers four parts.

The first part is “Introduction” which includes the following paragraph:

There is no right or wrong answers to the interview questions. Please answer truthfully based on your personal experiences and thoughts. All information gathered during the interview will be kept strictly confidential and only used for academic research purposes. Your personal information will not be revealed, and the research team will abide by confidentiality regulations and be willing to bear corresponding legal responsibilities. Ethical considerations will be taken into account throughout the research process. The interview will be audio recorded, as this is necessary to meet research requirements.

The second part is “Definition of terms” where several terms such as mobile social media, behavior trajectory, and intelligent recommendation were defined and illustrated. The third part is “General information of interviewees” where demographic information like gender, age, education level, major, location, occupation, years of internet use, and etc. were collected.

The fourth part is “Main questions” which includes the following ten main questions:

Do you use mobile social media? If so, please give examples of mobile social media platforms that you have used.

Do you understand intelligent recommendation? Please explain your understanding of intelligent recommender systems for mobile social media.

To improve the effectiveness of intelligent recommendation content, do you know whether mobile social media intelligent recommender systems collect personal information or privacy? If so, please give examples.

Do you think that intelligent recommender systems will track your browsing, searching, liking, reading, or jumping between applications within mobile social media applications? Please provide a detailed explanation.

Do you think that mobile social media intelligent recommender systems will track your location and other trajectories? Please provide a detailed explanation.

Regarding the behavior trajectories being recorded, do you feel concerned? Please provide a detailed explanation of your thought process and the reasons behind it.

Under what circumstances do you feel that your behavior trajectory is secure? Please provide a detailed explanation of the process and the reasons behind it.

Please rate or evaluate the satisfaction with the security protection of mobile social media users’ behavior trajectory in the intelligent recommendation context. Please provide a detailed description of the scoring points, lost points, and the reasons, and propose a remedy for the lost points.

In terms of behavior trajectory security protection, which App do you trust the most? Please provide a detailed explanation of the reasons and methods that make you trust the App even more.

In addition, what other factors do you think would affect the security protection of mobile social media users’ behavior trajectory in the intelligent recommendation context?

3.3 Sample Selection and Data Collection

This study followed a purposive sampling approach and selected participants who could be most informative to the research question (Corbin and Strauss 1990). The research participants were expected to have experience with mobile social media, intelligent recommender systems, and behavior trajectory security protection in order to provide substantial information for this research. Preferably, participants with experience, a robust background, and the capacity to understand and provide relevant information for the interview were selected. It was intended that they possessed higher information literacy, a wealth of knowledge reserves, clarity in expression, and a fitting background to the research. Participants must satisfy the interview requirements on certain aspects, such as time and energy, and consent to a complete recording of the interview.

The interviews were conducted over the course of five months to collect the necessary data for this research, with the interviewing process stopped after thorough verification of theoretical saturation. Ultimately, 22 interviewees were selected as the research sample for this research, which comprised 17 online and five offline sessions, with all interviewees consenting to the recording of the interviews. During the formal interviews, the questions were adjusted based on the respondents’ specific answers. Interviewers asked follow-up questions for responses that were incomplete or unclear and for topics that required greater depth. The recordings of the interviews were first transcribed once the interviews were complete, with the transcripts then manually compared to the recordings. Subsequently, the interviewees checked the transcripts for errors; in the absence of any errors, the transcripts were used as subsequent research materials. The 22 research materials were named as A to V, and stored as 22 files.

4 Grounded Analysis

4.1 Open Coding

This study analyzed original interview data sentence by sentence. In the process of open coding, “indigenous concepts” were elicited from the original statements as far as possible, while duplicate concepts were coded only once. In the end, 271 initial concepts were obtained, with examples of how initial concepts were elicited from original statements shown in Table 1.

Examples of how initial concepts were elicited from original statements.

| Original statements of interviewees | Initial concepts |

|---|---|

| F: The methods used by the app to collect geographic information are currently quite rudimentary. I don’t think it has substantial impacts compared to the other vital information leaks mentioned earlier. Knowing only the geographic information is insignificant, unless it is an extremely precise location, especially when other information is incomplete | Rudimentary geographic information, information leakage, insignificant geographic information, precise location, incomplete information |

| I: If there is relevant legislation, and there are comprehensive laws to regulate businesses, I think businesses can still be trusted | Legislation, comprehensive laws, regulate businesses, trust |

| K: It seems that people have a tendency to be submissive. I’ve already grown accustomed to being recorded, as if I’m unable to resist. It seems like everyone is being recorded in the same way as well. It’s useless to worry about it | Submissiveness, accustomed to being recorded, unable to resist, everyone being recorded in the same way as well, useless to worry |

| M: Social media requires displaying IP addresses. They make it mandatory to show your IP address when you’re online, and sometimes they don’t even allow you to avoid it. Basically, I have a strong aversion to anything mandatory. However, it doesn’t really cause me any fear or worry psychologically | Mandatory IP address display, aversion, mandatory, fear, worry |

This study carefully clustered and categorized initial concepts, resulting in 26 subcategories. The subcategories and initial concepts are shown in Table 2, which reflects data support during the identification and elicitation of subcategories.

Subcategories and initial concepts.

| Subcategories | Initial concepts |

|---|---|

| Timeliness of security protection information | Informative updates in accordance with law, timely alerts, timely requests for permissions, timely notification of information leaks |

| Completeness of security protection information | Detailed policy rules, details of personal information use, detailed privacy policy terms, asking for authorization without other explanation, describing only the approximate scope of information collection, incomplete information |

| Understandability of security protection information | Listing description contents, clear privacy terms, privacy terms with obvious elements, obscure privacy regulations, long-winded privacy regulations |

| Accessibility of security protection information | Difficult to reach users, pop-up notifications, pop-up requests for authorization, startup reminders, hiding privacy policy |

| Accuracy of security protection information | Informing what personal information is used, informing the specific information collected, informing the authorization required to use the normal functions, defining user rights, explaining precisely how the authorized information is used, asking if others are allowed to see it, convincing privacy policy |

| Reliability of security protection system | Property of the App, protection from operating system software, protection mechanisms, backed by powerful think tanks, technology of protection, platform quality, inadequate software, system security, system maintenance, inadequate hardware, tracking and handling leaked information, self-owned technology |

| Ease of using security protection system | Regular cleaning of trajectory information, complicated authorization settings, direct system settings, inconspicuous privacy settings, user migration |

| Empathy of safety protection service | High-handed provisions, unaffected experience without authorization, unavailable without authorization, rudimentary geographic information, reiterated notifications, rudimentary personal information collection, noticeable exploitation of personal information, uninformed using of personal information, precise personal information collection, following up with affected users, black box, synchronization of the background records deleting, precise location, mandatory IP address display, mandatory collection of personal information, mandatory, inducing permission granting, making me invisible to others, sensitive data collection, prior notification for information acquisition, considerate for users, restricting information collection |

| Compliance of safety protection service | Additional information collection, non-essential permission requirements, personal information storage, intensity of personal information collection, range of personal information collection, abstracted personal information, trafficking of personal information, misuse of personal information, scenarios of personal information usage, degree of personal information usage, notifications for personal information usage, purposes of personal information usage, limited usage of personal information, specific geographic location, specific information, cross-platform data sharing, implementation of privacy regulations, implementation of policies, authorization inquiry, disclosure of data status, information desensitization, data portability, privacy protection regulations, user consent, consent after regulations read, compliance with regulations |

| Controllability of safety protection service | Unable to set permissions, options for personal information collection, uncontrollable personal privacy, disabling intelligent recommendation services, options for content disclosure, permission off, data migration, data deletion, privacy protection function, user-controllable privacy |

| Perceived risks | Being audio recorded, being harassed, poor experience, increased cost, big data discriminatory pricing, risk of identity theft, location tracking, unfavorable to me, personal security risks, hacking, cross-application sharing of user information, spam marketing, tracking data of other applications, accumulation of data, risk of private content disclosure, negative recommended content, sensitive recommended content, information leakage, human flesh searching, internet streaking, information bubble, impact on many interests, user behavior tracking, inducing consumption, fraud, information extraction, knowledge of user preferences |

| Perceived benefits | Benefits, information accessing, economic incentives, discounts, pros outweigh cons, needs fulfilling, social needs fulfilling, convenient recommendation, accurate recommendation, useful recommendation, enjoy services, display and share |

| Social support | Promotion of cases, word of mouth, promotion of legislation, media coverage, comments from netizens, information disclosure, privacy education, privacy awareness, respect for privacy, application store rating, user perspective, public opinion controversy, knowledge popularization |

| Institutional support | Case transferring, penalties, public processing, third-party data security company, fines, public oversight of the businesses, public oversight of the government, regulation, rewards, legislation, judicial precedents, market self-discipline, data security standards, data security certification, data security auditing, notarization of data destruction, judiciary, complaint channel, comprehensive laws, strict employee admission, implementing harsh laws and punishments, regulate businesses, regulate government, policies, law enforcement, special inspection, strict requirements for employees, inadequate human resources |

| Optimistic biases | No worry about disadvantages, no impact on individuals, no concern about backend personnel having access to information, no serious problems as imagined, no experience of information being collected, no infringement of personal interests, no encountered information security issues |

| Extreme expectations | No possibility of private information disclosure, no protected privacy on the internet, inevitable privacy disclosure |

| Excessive self-confidence | No exposure of personal information, confident in ability |

| Brand influence | Official support background, brand strategy failure, corporate image, company size, corporate reputation |

| Imitating others | Everyone being recorded in the same way as well, not caring like everyone else, feeling indifferent because everyone is using it, feeling okay if everyone thinks it’s okay, opinion influenced by people around |

| Discounting own information | Transferring personal information to meet government requirements, provision of IP address for public safety, conceding privacy for the collective |

| Privacy consciousness | Privacy sensitivity, attention to information protection, attention to authorization, focusing on privacy, submissiveness, indifferent to privacy, reassuring yourself, numbness, ignoring terms, accustomed to being recorded, privacy security awareness |

| Privacy helplessness | Having to trust, having to use, useless to worry, powerlessness, unable to resist, must trust due to excessive use |

| Declarative knowledge | Mastery of regulations, value of personal information, citizen qualities, technophobia, supervision of information use, understanding of recommendation algorithms, knowledge of privacy policies, familiarity with information using scenarios, perception of algorithm operations, awareness of rights protection, information literacy, definition of privacy, user rights, knowledge reserves, professional background, insignificant geographic information |

| Procedural knowledge | Internet experience, reducing interaction, reduce disclosure, algorithm adjustment, stopping using, account cancellation, self-protection, revoking permissions, digestibility of privacy and security awareness |

| Judgment of fulfillment level in safety protection | 0∼5/10, 6–7/10, 8/10, insufficient, good, professional, not satisfied, satisfied, so-so |

| Pleasure response to fulfillment of safety protection | Feeling safe, reassured, violated, supported, non-rejection, discomfort, worry, aversion, fear, recognition, feeling of loss, depend, trust |

Table 3 illustrates the connotation and related literature regarding the 26 subcategories, demonstrating literature support during the identification of subcategories.

Definitions and literature support of subcategories.

| Subcategories | Definitions | Literature support |

|---|---|---|

| Timeliness of security protection information | The degree to which behavior trajectory security protection information is updated for the given task | Timeliness refers to how well the digital object is updated for the given task (Gonçalves et al. 2007) |

| Completeness of security protection information | The degree to which behavior trajectory security protection information contains information that describes related real-world phenomena | Completeness refers to the degree to which it contains information that describes related real-world phenomena (Bardaki et al. 2011) |

| Understandability of security protection information | The ease of reading, interpretability, and understandable behavior trajectory security protection information for users, along with the expressions utilized by reviewers encompassing language, semantics, and lexicons | Information understandability entails the ease of reading, interpretability, and understandable information for users, along with the expressions utilized by reviewers encompassing semantics, language, and lexicons (Filieri and McLeay 2014) |

| Accessibility of security protection information | The extent to which there is timely and continuous access to behavior trajectory security protection information | Accessibility encompasses the requirement for prompt and uninterrupted reach to the digital content (Burda and Teuteberg 2013) |

| Accuracy of security protection information | The degree of correctness in the provided behavior trajectory security protection information | Accuracy refers to the degree of correctness in the provided output information (Bailey and Pearson 1983) |

| Reliability of security protection system | The degree to which the behavior trajectory security protection system maintains a reliable level of availability, stability, and safety throughout its lifespan | Reliability pertains to the level of dependability (e.g., technical availability) of a system throughout its lifespan (Nelson et al. 2005) |

| Ease of using security protection system | The degree to which the behavior trajectory security protection system can reduce effort | Perceived ease of use relates to an individual’s belief in the effortless nature of using a specific system (Davis 1989) |

| Empathy of safety protection service | The degree to which the behavior trajectory security protection service respects the users’ feelings and rights and provides them with intimate and personalized attention and care | Empathy encompasses the act of offering personalized attention and care to customers (Kettinger and Lee 1994), as well as prioritizing the users’ best interests within the information system (DeLone and McLean 2003) |

| Compliance of safety protection service | The degree to which the behavior trajectory security protection service complies with information security procedures, guidelines, and policies | Information policy compliance pertains to the adherence of employees to information security procedures, guidelines, and policies (Moody et al. 2018) |

| Controllability of safety protection service | The extent to which users believe they can intervene or influence the collection, access, and utilization of their personal information by the behavior trajectory security protection service | Perceived information control relates to personal belief in their capacity to influence the collecting, accessing, and using of information, with the objective of avoiding potential security and privacy breaches (Li et al. 2020) |

| Perceived risks | The potential losses that users perceive when pursuing the expected results in using social media applications | Perceived risk is the possibility of experiencing losses while striving to achieve desired outcomes through the utilization of an e-service (Featherman and Pavlou 2003) |

| Perceived benefits | Users’ perceptions of the external benefits of the overall functionality and utility of social media applications, as well as the internal benefits derived from the joy and playfulness itself, including the benefits of shaping social image | Extrinsic benefits are derived from functionality and utility, whereas intrinsic benefits stem from the inherent enjoyment and playfulness. In addition, the perceived benefit of social image, which refers to the level of respect and admiration that peers in users’ social network have for the users due to their use of information technology, is another crucial component (Yang et al. 2016) |

| Social support | The social-level provisions such as emotion, information, tools, and companionship when given the pressure that users face in safeguarding their behavior trajectories | Social support most often refers to the act of providing or seeking emotional or instrumental assistance in response to negative or stressful life events (Feeney and Collins 2015), such as emotional support, information, instrumental support, and social companionship (Flannery Jr. 1990) |

| Institutional support | The support that government and institution provided to the market, corporations, and users when given the pressure that users face in safeguarding their behavior trajectories, in response to insufficient institutional infrastructure | Institutional support denotes the level of assistance provided by the government and associated agencies to firms, aiming to alleviate the adverse consequences of insufficient institutional infrastructure (Zhang et al. 2017) |

| Optimistic biases | The extent to which users are optimistic about behavior trajectory security protection | Developed in this study |

| Extreme expectations | The extent to which users perceive the behavior trajectory security protection to have extreme effects | |

| Excessive self-confidence | The extent to which users have an overestimation of their ability or knowledge of behavior trajectory security protection | |

| Brand influence | The extent to which users’ emotions, perceptions, and attitudes towards behavior trajectory security protection are influenced by corporate brands | |

| Imitating others | The extent to which users follow the practices of previous adopters when adopting behavior trajectory security protection technology | Sun (2013) categorized herd behavior as imitating others (the extent to which individuals emulate prior adopters in embracing a specific technological form) and discounting their own information (the extent to which individuals discount their own beliefs regarding a technology during the decision-making process of its adoption) |

| Discounting own information | The extent to which users ignore their own beliefs about the behavior trajectory security protection technology when making decisions | |

| Privacy consciousness | The extent to which users are aware of social media violating their privacy by recording information against their wishes | Developed in this study |

| Privacy helplessness | The extent to which users feel powerless regarding social media violating their privacy by recording information against their wishes | |

| Declarative knowledge | Users’ understanding of the technical aspects, laws, directives, and institutional practices related to online privacy data protection | Declarative knowledge encompasses users’ understanding of technical components of safeguarding online data, as well as comprehending laws, directives, and institutional practices. Procedural knowledge pertains to users’ capacity to implement strategies to regulate personal privacy and safeguard data (Bartsch and Dienlin 2016) |

| Procedural knowledge | Users’ ability to implement strategies to regulate personal privacy and safeguard data | |

| Judgment of fulfillment level in safety protection | User’s judgment on the degree of satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | Satisfaction refers to the response of customers towards products or services. It entails customers’ assessment of whether a specific feature or the overall product/service fulfilled their requirements to a satisfactory extent, encompassing both under and over fulfillment (Oliver 2014) |

| Pleasure response to fulfillment of safety protection | The degree to which users have a pleasant response to behavior trajectory security protection |

4.2 Axial Coding

During axial coding, the 26 subcategories were reorganized and clustered based on prior literature, resulting in 10 categories, as presented in Table 4.

Axial coding.

| Categories | Subcategories | Category connotation |

|---|---|---|

| Security protection information quality | Timeliness of security protection information | DeLone and McLean (1992) developed the information system success model (i.e. D&M model), and updated the D&M model ten years later (DeLone and McLean 2003). Based on the updated D&M model, this study extracted three categories, namely, security protection information quality, security protection system quality, and security protection service quality |

| Completeness of security protection information | ||

| Understandability of security protection information | ||

| Accessibility of security protection information | ||

| Accuracy of security protection information | ||

| Security protection system quality | Reliability of security protection system | |

| Ease of using security protection system | ||

| Security protection service quality | Empathy of safety protection service | |

| Compliance of safety protection service | ||

| Controllability of safety protection service | ||

| Net benefits | Perceived risks | The privacy calculus theory suggests that individuals are more likely to disclose information when they perceive that the benefits of disclosure outweigh or are at least equal to the perceived risks (Dinev and Hart 2006). The updated D&M model also chose to classify all effects measures into one category of impacts or benefits called “net benefits” (DeLone and McLean 2003). This research defines the “net benefits” as the combined benefit level of perceived risks and perceived benefits |

| Perceived benefits | ||

| External support | Social support | This study considers external support from the viewpoint of mobile social media users to comprise social support and institutional support provided by official and business sectors. Building on the theory of social support (Cobb 1976), the study categorizes the perceived social and institutional support among mobile social media users as external support |

| Institutional support | ||

| Privacy cognitive biases | Optimistic biases | Waldman (2020) noted that online environments compel us to disclose information and activate cognitive biases that persuade us to abandon our privacy rights. Based on the concept of cognitive biases, this study summarizes users’ privacy rights related beliefs as privacy cognitive biases |

| Extreme expectations | ||

| Excessive self-confidence | ||

| Brand influence | ||

| Herd behavior | Imitating others | Banerjee (1992) proposed that herd behavior refers to the phenomenon where people follow the actions of the masses, even if their own private information suggests that they should take completely different actions. This study summarizes imitating others and discounting own information as herd behavior by following Banerjee (1992) and Sun (2013) |

| Discounting own information | ||

| Privacy concerns | Privacy consciousness | Based on Moreham’s research (2014) on privacy, this study contends that privacy concerns pertain to the degree to which social media users perceive their behavior trajectories as being under “unwanted observation and recording” in the context of intelligent recommendations |

| Privacy helplessness | ||

| Privacy literacy | Declarative knowledge | Online privacy literacy covers declarative knowledge which concerns “knowing what” and procedural knowledge which concerns “knowing how” about online privacy (Bartsch and Dienlin 2016) |

| Procedural knowledge | ||

| Satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | Judgment of fulfillment level in safety protection | Following Oliver (2014), satisfaction with the currently provided behavior trajectory security protection includes judgment of the fulfillment level in safety protection and the pleasure response to fulfillment of safety protection |

| Pleasure response to fulfillment of safety protection |

4.3 Selective Coding

During selective coding, after careful and repeated comparison, the relationships among categories emerged as revolving around satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection. Consequently, satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection was identified as the core category. Table 5 displays the typical relationship between categories. Figure 1 shows a theoretical model regarding the influencing mechanism of satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection in the context of intelligent recommendation.

Typical relationships between categories.

| Typical relationship between categories | Connotations | Representative original statements |

|---|---|---|

| Security protection information quality→ Satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | Security protection information quality in terms of five subcategories such as accessibility of security protection information has a direct impact on satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | H: Every time I open the App it pops up and asks if you allow it to access your geolocation… I’m kind of feeling okay about the privacy |

| Security protection system quality →Satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | Security protection system quality in terms of two subcategories such as reliability of the security protection system has a direct impact on satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | B: Nowadays, social media, including its environmental setup, utilization of databases, and its system architecture, is, in general, running quite stably. It is relatively secure, with rare occurrences of major failures leading to information leaks. In this respect, I am quite satisfied |

| Security protection service quality →Satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | Security protection service quality in terms of three subcategories such as empathy of safety protection service has a direct impact on satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | E: For example, certain functions in the software may have mandatory requirements. If you decline to click “Agree,” you may be unable to access some parts of the software. This could potentially result in being unable to use the software at all, which might make you feel as though you have lost your user rights |

| Net benefits →Satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | Net benefits in terms of two subcategories such as perceived benefits have a direct impact on satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | C: I believe that the gathering of this information can also have its own positive aspects. Nowadays, many people tend to be overly sensitive about it. By studying and analyzing your location, the App can display nearby places that are more suited to your preferences when you open it. This is actually a beneficial feature for users |

| External support →Satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | External support in terms of two subcategories such as social support has a direct impact on satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | J: If the government were to use or support this platform, it would greatly alleviate many of my worries about it |

| Privacy literacy →Privacy concerns | Privacy literacy in terms of two subcategories such as declarative knowledge has a direct impact on privacy concerns | L: For example, those of us studying information management, including studying confidentiality, might generally be more concerned because we often come across a lot of related knowledge and case studies in our regular studies, making us a bit more sensitive to these matters |

| Herd behavior → Privacy concerns | Herd behavior in terms of two subcategories such as imitating others has a direct impact on privacy concerns | L: Earlier, we were discussing about during the pandemic… individuals might feel influenced by the people around them. As they could see that everybody’s information is out there and it seems nobody cares about it, this could lead someone to adopt a more carefree attitude towards their own privacy |

| Privacy concerns →Satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | Privacy concerns in terms of two subcategories such as privacy consciousness has a direct impact on satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | G: Personally, in order to improve my satisfaction, I try to relax and avoid having too much insecurity or doubt. After all, I use this platform because I trust it and rely on it |

| Privacy literacy → Privacy cognitive biases →Satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | Privacy literacy in terms of two subcategories such as procedural knowledge has a direct impact on privacy cognitive biases which further has a direct impact on satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection | B: If I have a high level of information or data literacy, it can increase my satisfaction and confidence in my abilities. As a consequence, I would likely have more confidence in the security protection for my personal trajectories, and this would contribute to an overall sense of satisfaction |

Theoretical model of influencing mechanism of satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection in the context of intelligent recommendation.

4.4 Test of Theoretical Saturation

When no new categories and relationships emerge during coding, theoretical saturation is likely to be achieved (Francis et al. 2010). This study followed the theoretical saturation principle for coding and sample selection. After analyzing the seventeenth sample, no new categories or relationships were identified. To ensure theoretical saturation, an additional five interviews were conducted and analyzed, and no new categories or relationships were identified either. Consequently, it can be suggested that the theoretical model developed in Figure 1 achieved theoretical saturation.

5 Discussion and Implications

5.1 Discussion of Results

From Figure 1, it can be seen that security protection information quality, security protection system quality, and security protection service quality have direct impacts on satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection. This is consistent with the information system success model which suggests that information quality, system quality, service quality, and satisfaction are critical for a successful information system (DeLone and McLean 2003). The results suggest that the success of behavior trajectory security protection is embodied in the success of an information system. Indeed, information quality could potentially measure semantic success of behavior trajectory security protection, system quality could potentially measure technical success of behavior trajectory security protection, and service quality could potentially measure application success of behavior trajectory security protection. Additionally, satisfaction could potentially measure effectiveness of behavior trajectory security protection (Zha et al. 2015).

5.2 Implications for Theory

The results have important theoretical implications. First, this study contributes to the development of the theoretical model of the influencing mechanism of satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection in the context of intelligent recommendation. Second, much research has been conducted to extend the information system success model, however, behavior trajectory security protection in the context of intelligent recommendation has been overlooked in prior literature; this study usefully extended the information system success model to the field of behavior trajectory security protection. Third, following Waldman (2020) who proposed cognitive biases, this study proposed privacy cognitive biases to summarize users’ privacy rights related beliefs. These beliefs include optimistic biases, extreme expectations, excessive self-confidence, and brand influence, all of which were developed in this study.

5.3 Implications for Practice

The results have important practical implications. First, when security protection information quality is high, the security protection information is updated, complete, understandable, accessible, and accurate. When security protection system quality is high, the security protection system is reliable and easy to use. When security protection service quality is high, the security protection service is empathetic, compliant, and controllable. It is thus recommended that developers and managers of behavior trajectory security protection should bear in mind the importance of the information system success model. Second, in the context of intelligent recommendation, users’ behavior trajectories are usually recorded by the system. When behavior trajectories are looked at, listened to, or recorded against a person’s wishes, his or her privacy is breached (Moreham 2014). It can be seen from Figure 1 that three categories related to privacy were identified, namely, privacy literacy, privacy concerns, and privacy cognitive biases. It is found that privacy literacy directly impacts privacy concerns and privacy cognitive biases, both of which have direct impacts on satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection. It is thus recommended that users’ privacy should be given top consideration and protected as far as possible.

6 Conclusion

Intelligent recommendation is a double-edged sword. It could possibly reduce information overload to benefit users, however, it could also possibly breach users’ privacy by recording their behavior trajectory against their wishes, bringing new issues such as behavior trajectory privacy concerns and users’ dissatisfaction. This study applied the grounded theory method to conduct three-level coding, with the results conveying the influencing mechanism of social media users’ satisfaction with behavior trajectory security protection in the context of intelligent recommendation. This study extended the information system success model by highlighting that the success of behavior trajectory security protection is characterized by the success of an information system. Three categories related to privacy were identified, which provide useful insights on privacy literacy, privacy concerns, and privacy cognitive biases. Consequently, when the importance of the information system success model and users’ privacy is borne in the mind of developers and managers, users are more likely to have higher judgment of and more satisfaction toward the fulfillment of safety protection. Future research could employ other methods such as the quantitative method to test the relationships developed in this study, and it is reasonable to suggest that this and future studies could promote healthy development of mobile social media in the context of intelligent recommendation.

Funding source: National Social Science Fund of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 23&ZD223

Acknowledgment

This study is supported by the National Social Science Fund of China [grant number 23&ZD223].

References

Al-Hussaeni, K., B. C. M. Fung, and W. K. Cheung. 2014. “Privacy-Preserving Trajectory Stream Publishing.” Data & Knowledge Engineering 94: 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.datak.2014.09.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Alshare, K. A., M. Moqbel, and M. A. Al-Garni. 2019. “The Impact of Trust, Security, and Privacy on Individual’s Use of the Internet for Online Shopping and Social Media: A Multi-Cultural Study.” International Journal of Mobile Communications 17 (5): 513–36. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMC.2019.102082.Suche in Google Scholar

Alshehri, A., and R. O’Keefe. 2019. “Analyzing Social Media to Assess User Satisfaction with Transport for London’s Oyster.” International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 35 (15): 1378–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2018.1526442.Suche in Google Scholar

Bailey, J. E., and S. W. Pearson. 1983. “Development of A Tool for Measuring and Analyzing Computer User Satisfaction.” Management Science 29 (5): 530–45. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.5.530.Suche in Google Scholar

Balbi, S., M. Misuraca, and G. Scepi. 2018. “Combining Different Evaluation Systems on Social Media for Measuring User Satisfaction.” Information Processing & Management 54 (4): 674–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2018.04.009.Suche in Google Scholar

Banerjee, A. V. 1992. “A Simple Model of Herd Behavior.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (3): 797–817. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118364.Suche in Google Scholar

Barabas, R. 2023. “What’s the News about Bad News? A Review of Bad News Games as a Tool to Teach Media Literacy.” Libri – International Journal of Libraries and Information Services 73 (4): 283–92. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2023-0043.Suche in Google Scholar

Bardaki, C., P. Kourouthanassis, and K. Pramatari. 2011. “Modeling the Information Completeness of Object Tracking Systems.” The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 20 (3): 268–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2011.03.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Bartsch, M., and T. Dienlin. 2016. “Control Your Facebook: An Analysis of Online Privacy Literacy.” Computers in Human Behavior 56: 147–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.022.Suche in Google Scholar

Burda, D., and F. Teuteberg. 2013. “Sustaining Accessibility of Information through Digital Preservation: A Literature Review.” Journal of Information Science 39 (4): 442–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551513480107.Suche in Google Scholar

Cengiz, A. B., G. Kalem, and P. S. Boluk. 2022. “The Effect of Social Media User Behaviors on Security and Privacy Threats.” IEEE Access 10: 57674–684. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3177652.Suche in Google Scholar

Cho, H. C., S. Roh, and B. Park. 2019. “Of Promoting Networking and Protecting Privacy: Effects of Defaults and Regulatory Focus on Social Media Users’ Preference Settings.” Computers in Human Behavior 101: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.001.Suche in Google Scholar

CNCERT/CC, and CSAC. 2021. “App Illegal Collection and Use of Personal Information Monitoring Analysis Report.” Beijing, China: CNCERT/CC. https://www.cert.org.cn/publish/main/upload/File/APP%20abusing%20report.pdf (accessed July 25, 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

CNNIC. 2023. The 51st Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development. Beijing: CNNIC. https://www.cnnic.cn/NMediaFile/2023/0322/MAIN16794576367190GBA2HA1KQ.pdf (accessed July 25, 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Cobb, S. M. D. 1976. “Social Support as A Moderator of Life Stress.” Psychosomatic Medicine 38 (5): 300–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003.Suche in Google Scholar

Corbin, J. M., and A. Strauss. 1990. “Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria.” Qualitative Sociology 13 (1): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593.Suche in Google Scholar

Dai, Y., J. Shao, C. Wei, D. Zhang, and H. T. Shen. 2018. “Personalized Semantic Trajectory Privacy Preservation through Trajectory Reconstruction.” World Wide Web 21 (4): 875–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11280-017-0489-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Davis, F. D. 1989. “Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology.” MIS Quarterly 13 (3): 319–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.Suche in Google Scholar

DeLone, W. H., and E. R. McLean. 1992. “Information Systems Success: The Quest for the Dependent Variable.” Information Systems Research 3 (1): 60–95. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.3.1.60.Suche in Google Scholar

DeLone, W. H., and E. R. McLean. 2003. “The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: A Ten-Year Update.” Journal of Management Information Systems 19 (4): 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2003.11045748.Suche in Google Scholar

Dinev, T., and P. Hart. 2006. “An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for E-Commerce Transactions.” Information Systems Research 17 (1): 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1060.0080.Suche in Google Scholar

Featherman, M. S., and P. A. Pavlou. 2003. “Predicting E-Services Adoption: A Perceived Risk Facets Perspective.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 59 (4): 451–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00111-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Feeney, B. C., and N. L. Collins. 2015. “A New Look at Social Support: A Theoretical Perspective on Thriving through Relationships.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 19 (2): 113–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544222.Suche in Google Scholar

Filieri, R., and F. McLeay. 2014. “E-WOM and Accommodation: An Analysis of the Factors that Influence Travelers’ Adoption of Information from Online Reviews.” Journal of Travel Research 53 (1): 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513481274.Suche in Google Scholar

Flannery Jr, R. B. 1990. “Social Support and Psychological Trauma: A Methodological Review.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 3 (4): 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490030409.Suche in Google Scholar

Foley, S. N., and V. Rooney. 2018. “A Grounded Theory Approach to Security Policy Elicitation.” Information & Computer Security 26 (4): 454–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICS-12-2017-0086.Suche in Google Scholar

Francis, J. J., M. Johnston, C. Robertson, L. Glidewell, V. Entwistle, M. P. Eccles, and J. M. Grimshaw. 2010. “What Is an Adequate Sample Size? Operationalising Data Saturation for Theory-Based Interview Studies.” Psychology and Health 25 (10): 1229–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903194015.Suche in Google Scholar

Fu, S. X., H. X. Li, Y. Liu, H. Pirkkalainen, and M. Salo. 2020. “Social Media Overload, Exhaustion, and Use Discontinuance: Examining the Effects of Information Overload, System Feature Overload, and Social Overload.” Information Processing & Management 57 (6): 102307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102307.Suche in Google Scholar

Ge, M., and F. Persia. 2019, “Factoring Personalization in Social Media Recommendations.” In: c2019. ICSC 2019. Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 13th International Conference on Semantic Computing; 2019 January 30 - February 1; Newport Beach, CA, USA, 344–7. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE.10.1109/ICOSC.2019.8665624Suche in Google Scholar

Gerlach, J. P., N. Eling, N. Wessels, and P. Buxmann. 2019. “Flamingos on A Slackline: Companies’ Challenges of Balancing the Competing Demands of Handling Customer Information and Privacy.” Information Systems Journal 29 (2): 548–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12222.Suche in Google Scholar

Glaser, B. G., A. L. Strauss, and E. Strutzel. 1968. “The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research.” Nursing Research 17 (4): 364. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-196807000-00014.Suche in Google Scholar

Gonçalves, M. A., B. L. Moreira, E. A. Fox, and L. T. Watson. 2007. “What Is a Good Digital Library? - A Quality Model for Digital Libraries.” Information Processing & Management 43 (5): 1416–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2006.11.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Guetterman, T. C., W. A. Babchuk, M. C. H. Smith, and J. Stevens. 2019. “Contemporary Approaches to Mixed Methods-Grounded Theory Research: A Field-Based Analysis.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 13 (2): 179–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689817710877.Suche in Google Scholar

Häußler, H. 2021. “The Underlying Values of Data Ethics Frameworks: A Critical Analysis of Discourses and Power Structures.” Libri – International Journal of Libraries and Information Services 71 (4): 307–19. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2021-0095.Suche in Google Scholar

Islam, A. N., S. Laato, S. Talukder, and E. Sutinen. 2020. “Misinformation Sharing and Social Media Fatigue during COVID-19: An Affordance and Cognitive Load Perspective.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 159: 120201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120201.Suche in Google Scholar

Keshavarz, H., Y. Norouzi, and A. Shabani. 2022. “The Roles of Social Media in Information Services: Systematic Review and Expert Scrutiny.” Libri – International Journal of Libraries and Information Services 72 (4): 417–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2021-0124.Suche in Google Scholar

Kettinger, W. J., and C. C. Lee. 1994. “Perceived Service Quality and User Satisfaction with the Information Services Function.” Decision Sciences 25 (5–6): 737–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1994.tb01868.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Khan, M. I., J. M. Loh, A. Hossain, and M. J. H. Talukder. 2023. “Cynicism as Strength: Privacy Cynicism, Satisfaction, and Trust Among Social Media Users.” Computers in Human Behavior 142: 107638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107638.Suche in Google Scholar

Kumar, N. S., K. Saravanakumar, and K. Deepa. 2016. “On Privacy and Security in Social Media – A Comprehensive Study.” Procedia Computer Science 78: 114–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2016.02.019.Suche in Google Scholar

Lai, T. P., and X. H. Zheng. 2015. “Machine Learning Based Social Media Recommendation.” In c2015. ICSDM 2015. Proceedings of the 2015 2nd IEEE International Conference on Spatial Data Mining and Geographical Knowledge Services; 2015 July 8-10; Fuzhou, China, 28–32. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE.10.1109/ICSDM.2015.7298020Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Y., K. C. Chang, and J. G. Wang. 2020. “Self-Determination and Perceived Information Control in Cloud Storage Service.” Journal of Computer Information Systems 60 (2): 113–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2017.1405294.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Y. X., W. K. Tse, P. Y. Kwok, and Y. H. Chiu. 2022. “Impact of Social Media Behavior on Privacy Information Security Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process.” Information 13 (6): 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13060280.Suche in Google Scholar

Maher, C., M. Hadfield, M. Hutchings, and A. de Eyto. 2018. “Ensuring Rigor in Qualitative Data Analysis: A Design Research Approach to Coding Combining NVivo with Traditional Material Methods.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17 (1): 1609406918786362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918786362.Suche in Google Scholar

Martínez-Navalón, J. G., V. Gelashvili, and J. R. Saura. 2020. “The Impact of Environmental Social Media Publications on User Satisfaction with and Trust in Tourism Businesses.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (15): 5417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155417.Suche in Google Scholar

Miah, S. J., H. Q. Vu, J. Gammack, and M. McGrath. 2017. “A Big Data Analytics Method for Tourist Behaviour Analysis.” Information & Management 54 (6): 771–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.11.011.Suche in Google Scholar

Moody, G. D., M. Siponen, and S. Pahnila. 2018. “Toward a Unified Model of Information Security Policy Compliance.” MIS Quarterly 42 (1): 285–311. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2018/13853.Suche in Google Scholar

Moreham, N. 2014. “Beyond Information: Physical Privacy in English Law.” The Cambridge Law Journal 73 (2): 350–77. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008197314000427.Suche in Google Scholar

Mosteller, J., and A. Poddar. 2017. “To Share and Protect: Using Regulatory Focus Theory to Examine the Privacy Paradox of Consumers’ Social Media Engagement and Online Privacy Protection Behaviors.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 39 (1): 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2017.02.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Naab, T. K., and A. Sehl. 2017. “Studies of User-Generated Content: A Systematic Review.” Journalism 18 (10): 1256–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916673557.Suche in Google Scholar

Narangajavana Kaosiri, Y., L. J. Callarisa Fiol, M. Á. Moliner Tena, M. R. Rodríguez Artola, and J. Sánchez García. 2019. “User-Generated Content Sources in Social Media: A New Approach to Explore Tourist Satisfaction.” Journal of Travel Research 58 (2): 253–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517746014.Suche in Google Scholar

Nelson, R. R., P. A. Todd, and B. H. Wixom. 2005. “Antecedents of Information and System Quality: An Empirical Examination within the Context of Data Warehousing.” Journal of Management Information Systems 21 (4): 199–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2005.11045823.Suche in Google Scholar

Oliver, R. L. 2014. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective On The Consumer. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315700892Suche in Google Scholar

Pang, H. 2021. “Identifying Associations between Mobile Social Media Users’ Perceived Values, Attitude, Satisfaction, and eWOM Engagement: The Moderating Role of Affective Factors.” Telematics and Informatics 59: 101561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101561.Suche in Google Scholar

Ranogajec, M. G., and B. Badurina. 2021. “Measuring User Confidence in Social Media Security and Privacy.” Education for Information 37 (4): 427–42. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-211556.Suche in Google Scholar

Sun, H. S. 2013. “A Longitudinal Study of Herd Behavior in the Adoption and Continued Use of Technology.” MIS Quarterly 37 (4): 1013–41. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.4.02.Suche in Google Scholar

Timmermans, S., and I. Tavory. 2012. “Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis.” Sociological Theory 30 (3): 167–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275112457914.Suche in Google Scholar

Ur, B., and Y. Wang. 2013. “A Cross-Cultural Framework for Protecting User Privacy in Online Social Media.” In c2013. WWW 2013. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web; 2013 May 13-17; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 755–62. New York: Association for Computing Machinery.10.1145/2487788.2488037Suche in Google Scholar

Uram, P., and S. Skalski. 2022. “Still Logged in? The Link Between Facebook Addiction, FoMO, Self-Esteem, Life Satisfaction, and Loneliness in Social Media Users.” Psychological Reports 125 (1): 218–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294120980970.Suche in Google Scholar

Waldman, A. E. 2020. “Cognitive Biases, Dark Patterns, and the ‘Privacy Paradox.” Current Opinion in Psychology 31: 105–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.025.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, S. J., G. Pasi, L. Hu, and L. B. Cao. 2020. “The Era of Intelligent Recommendation: Editorial on Intelligent Recommendation with Advanced AI and Learning.” IEEE Intelligent Systems 35 (5): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2020.3026430.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Y. F., M. Z. Li, Y. Xin, G. C. Yang, Q. F. Tang, H. L. Zhu, Y. X. Yang, and Y. L. Chen. 2021. “Exchanging Registered Users’ Submitting Reviews towards Trajectory Privacy Preservation for Review Services in Location-Based Social Networks.” PLoS One 16 (9): e0256892. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256892.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, F., S. Zhao, W. Y. Li, R. Evans, and W. Zhang. 2020. “Understanding User Satisfaction with Chinese Government Social Media Platforms.” Information Research 25 (3): 865. https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper865.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, H., J. Yu, H. Zo, and M. Choi. 2016. “User Acceptance of Wearable Devices: An Extended Perspective of Perceived Value.” Telematics and Informatics 33 (2): 256–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.08.007.Suche in Google Scholar

Zha, X. J., J. C. Zhang, Y. L. Yan, and Z. L. Xiao. 2015. “Does Affinity Matter? Slow Effects of E-Quality on Information Seeking in Virtual Communities.” Library & Information Science Research 37 (1): 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2014.04.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, S. S., Z. Q. Wang, X. D. Zhao, and M. Zhang. 2017. “Effects of Institutional Support on Innovation and Performance: Roles of Dysfunctional Competition.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 117 (1): 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-10-2015-0408.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- The Potential of Telepresence in Libraries: Students’ Perspectives

- Satisfaction with Behavior Trajectory Security Protection in Social Media Intelligent Recommendations

- Agricultural Information Needs and Resources of Smallholder Sugarcane Farmers in Swaziland

- Bridging the Digital Divide: Developing Local Digital Heritage Content and Investigating Localized Digital Solutions

- Identifying the Applications of Gamification for Audience Attraction in Public Libraries

- Construction of Intellectual Property Literacy Education Mode in University Libraries

- Digital Divide and University Students’ Online Learning amidst Covid-19 Pandemic in Malaysia

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- The Potential of Telepresence in Libraries: Students’ Perspectives

- Satisfaction with Behavior Trajectory Security Protection in Social Media Intelligent Recommendations

- Agricultural Information Needs and Resources of Smallholder Sugarcane Farmers in Swaziland

- Bridging the Digital Divide: Developing Local Digital Heritage Content and Investigating Localized Digital Solutions

- Identifying the Applications of Gamification for Audience Attraction in Public Libraries

- Construction of Intellectual Property Literacy Education Mode in University Libraries

- Digital Divide and University Students’ Online Learning amidst Covid-19 Pandemic in Malaysia