Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is an international public health crisis without precedent in the last century. The novelty and rapid spread of the virus have added a new urgency to the availability and distribution of reliable information to help curb its fatal potential. As seasoned and trusted purveyors of reliable public information, librarians have attempted to respond to the “infodemic” of fake news, disinformation, and propaganda with a variety of strategies, but the COVID-19 pandemic presents a unique challenge because of the deadly stakes involved. The seriousness of the current situation requires that librarians and associated professionals re-evaluate the ethical basis of their approach to information provision to counter the growing prominence of conspiracy theories in the public sphere and official decision making. This paper analyzes the conspiracy mindset and specific COVID-19 conspiracy theories in discussing how libraries might address the problems of truth and untruth in ethically sound ways. As a contribution to the re-evaluation we propose, the paper presents an ethical framework based on alethic rights—or rights to truth—as conceived by Italian philosopher Franca D’Agostini and how these might inform professional approaches that support personal safety, open knowledge, and social justice.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is an international public health crisis without precedent in the last century. The novelty and rapid spread of the virus have added a new urgency to the availability and distribution of reliable information to help curb its fatal potential as long-term remedies remain under development. High speed Internet, digital technologies, and social media provide a broad-based global network for such vital communication. But like many other amplified public discussions in the web era, the pandemic has been politicized from the outset and subject to conspiracy theory driven narratives that contribute to public confusion, uncertainty, anger, and fear. Many of these conspiracies originate on the web and are created and pushed through social networks by self-interested actors to advance a political agenda or compound the existing epistemic dissonance around contentious issues or policies. However, these efforts are often subtle and sophisticated, utilizing algorithms and platform features that by design play to users’ preferences, biases, and emotions (Goodman 2020). In this setting, false and otherwise implausible narratives are embraced and exchanged over contradictory facts, logic, evidence, or expertise from sources traditionally considered authoritative and truthful. This article discusses conspiracy theories as a complex psycho-social issue with distinctive informational aspects that often serve to undermine the epistemological foundations of public discourse, democratic norms, and social justice by directly and indirectly attacking the concept of objective truth.

As seasoned and trusted purveyors of reliable public information, librarians have attempted to respond to the current “infodemic” of fake news, disinformation, and propaganda with a variety of strategies that comport with widely accepted professional methods and values.[1] However, a cluster of conspiracy theories has emerged around the COVID-19 pandemic causing librarians to question how they might help combat the negative (and potentially deadly) impacts of this trend in ethically sound ways. Indeed, the seriousness of the current situation requires that librarians and associated information professionals re-evaluate the ethical basis of their approach to information provision to help offset the growing prominence of conspiracy theories in the public sphere and in official decision-making. Using the COVID-19 conspiracy phenomenon as a backdrop, this article introduces an ethical framework based on alethic rights—or rights to truth—as conceived by Italian philosopher Franca D’Agostini. Considering the wider implications of an alethic society, the article examines how a truth-based ethics founded in social justice might inform LIS in the infodemic era. We consider some practical applications and implications of alethic rights for LIS, but mostly seek to challenge LIS professionals to re-think their ethical assumptions and initiate conversations on truth and untruth that might propel concrete actions moving forward.

2 The Conspiracy Mindset in Context

In the mid-1960s, historian Richard Hofstadter coined the phrase “paranoid style” to describe a mindset shaped by “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy” that has characterized American politics and public life since the country’s inception (1964, sec. 1, para. 1). Hofstadter described the international scope of this mentality, where groups and individuals facing social ills develop convoluted explanations and assign external blame for the problems they face, often linking these to powerful entities and interests (usually of foreign origin) beyond their control. Indeed, Hofstadter showed that, historically, the conspiracy mindset of the paranoid style surfaces along the full spectrum of political ideology, with each underlying movement focused on identifying bogeymen, punishing scapegoats, and maintaining the vanguard against nefarious threats to their varied ways of life. However, despite what the phrase suggests, the paranoid style does not necessarily emerge from individual character flaws, mental illness, or collective delusion. As Hofstadter noted, “It is the use of modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant” (1964, sec. 1, para. 1). Hofstadter viewed this “persistent psychic phenomenon” as mostly confined to a small percentage of the population, but acknowledges that certain religious traditions, social structures, national inheritances, and historical catastrophes and frustrations “may be conducive to the release of such psychic energies, and to situations in which they can more readily be built into mass movements or political parties” (1964, sec. 6, para. 2).

Unfortunately, the paranoid style has “a greater affinity for bad causes than good,” because the animating ideas of conspiracy theories find their power in how strenuously their adherents believe in them, not whether they are true or false, nor whether they conform to extant conceptions of morality (Hofstadter 1964, sec. 1, para. 2). Hofstatdter’s formulation of the paranoid style was offered in the wake of the John F. Kennedy assassination and presaged a growing academic and popular interest in the conspiracy mindset in the following decades. Other high profile assassinations, the rise of minority and anti-war social movements, anti-establishment revolutions and civil unrest, and the breakneck speed of globalization and technological advancement all gave rise to new conspiracy theories or reshaped existing ones from the mid-1960s onward, thus prompting multidisciplinary approaches to understanding their social and political origins and impact. However, according to Douglas et al. (2019), most empirical research efforts into conspiracy theories’ causes and consequences are relatively recent, roughly corresponding to the rise in networked social media and intensifying political and social division in the last decade. During this time, conspiracy theories have been increasingly linked to terror attacks, climate science denial, public health emergencies, and the rise of authoritarian impulses in ostensibly free representative democracies. Yet the factors around conspiracy theory belief and dissemination are complex, and often rooted in a basic human need to understand one’s place in the world.

Douglas et al. define conspiracy theories as “attempts to explain the ultimate causes of significant social and political events and circumstances with claims of secret plots by two or more powerful actors” (2019, 4). These often involve governments, but could also include any individual, group, or organization perceived as sufficiently powerful and malevolent. Douglas, Sutton and Cichocka (2017) identified three primary categories of psychological motivations that draw people to conspiracy theories: epistemic (the desire for understanding, accuracy, and subjective certainty), existential (the desire for control and security), and social (the desire to maintain a positive image of the self or group). Demographics play a significant role as well, with conspiracy theories often flourishing among individuals with lower levels of income and education, and frequently characterized by other psychological or social disadvantages related to employment, community status, and geographic location (Douglas et al. 2019). Conspiracy theories have a distinctive political character in that political decisions often create winners and losers, thus contributing to any preexisting sense of powerlessness, distrust in institutions, and epistemic uncertainty. Additionally, political actors often weaponize conspiracy theories to discredit opposing views, either to cast opponents as complicit in a conspiracy or to denigrate legitimate criticism as fringe or extreme.

In any case, the conspiracy mindset allows people to perceive nefarious motivations in all political or ideological activity that does not align with their own; any confrontation with viewpoints, facts, or evidence that contradicts their beliefs only tends to harden their resolve and advance any self-deception already at play. Understanding individual and social cognition is a key to recognizing how conspiracy theories take such deep root in certain sectors of the population. Personality traits, individual beliefs, and one’s immediate social environment provide the foundation for how one seeks out (or does not seek out) information, as well as how they understand and interpret it. Recent multidisciplinary research on the intersection of confirmation bias, information bubbles, motivated reasoning, and political ideology reveals that around the globe people have become less trusting of institutions and other people, more suspicious of traditional authority, and—perhaps as both cause and effect—more likely to narrowly curate their information intake (Dimock 2019; Doherty and Kiley 2016; Rainie and Perrin 2019; Washburn and Skitka 2018). This often manifests in strategies to avoid and/or attack information that explicitly calls out deeply held beliefs and to only seek out information that reflects desirable political outcomes or perspectives, regardless of its accuracy or factual basis (Griffin and Niemand 2017; Tappin, van der Leer, and McKay 2017). These underlying confirmation and disconfirmation biases driving information consumption are further activated and validated by false or pseudo-cognitive authorities (politicians, religious figures, media pundits, etc.) who push untrue conspiracy narratives across communication channels to advance their own political or ideological objectives (Froehlich 2019).

Conspiracy theories invariably contain a redemptive arc that offers an eventual political or social victory of some sort for its believers. But perhaps the more immediate appeal is that they offer access to larger truths for the relatively small and close knit groups (increasingly online) looking for answers, community, and a cause to organize and proselytize around (Douglas et al. 2019). It does not matter if the details of the conspiracy are constantly in flux, lacking consistency, or easily debunked; external opposition (especially from experts) only confirms the truths these communities have constructed. The continued polarization of these communities contributes to a growing tribal epistemology, where information is “evaluated based not on conformity to common standards of evidence or correspondence to a common understanding of the world, but on whether it supports the tribe’s values and goals and is vouchsafed by tribal leaders” (Roberts 2019, sec. 1, para. 11). Although these communities tend to be isolated, there is cross-germination between groups with complementary views and/or shared opponents. As such, the central ideas of these conspiracy theories (and resulting cognitive dissonance) are easily co-opted and increasingly mainstreamed through the purposeful efforts of powerful groups and individuals, especially by governments with authoritarian leanings who seek to launder and legitimize their position through various media (Diamond 2020; Illing 2020).

Political psychologist Shawn W. Rosenberg views the rise of right wing authoritarian populism around the globe as the inevitable result of democratic successes: “the ever more democratic conditions of everyday life and the ever more democratic structuring of the public sphere, has undermined the essentially undemocratic power of ‘democratic’ elites to manage that critical structural weakness of democratic governance, a citizenry that lacks the cognitive and emotional capacities to think, feel and act in ways required” (2019, sec. 9, para. 7). The citizen incompetence that Rosenberg describes is largely rooted in the inability of individuals to critically assess and engage with the range of information available to them. The preponderance of conspiracy theories in the web age provides succor for anti-democratic movements because they frequently “offer a message that is intrinsically more comprehensible and satisfying to a recipient public hungry for meaning, security and direction,” irregardless of that message’s coherence or truth value (Rosenberg 2019, sec. 9, para. 7). The COVID-19 pandemic—with the expanding social, political, and economic reliance on web-based communication—is just the kind of disruptive event that threatens the short and long term viability of democratic institutions that typically manage such crises. The threat is accelerated by conspiracy theories created or co-opted for these unique historical circumstances, which have already had a profoundly negative impact on attempts to mitigate the pandemic.

3 The COVID-19 Conspiracy Cluster

Even if the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic are unique, the cluster of conspiracy theories around it is mostly an updated version of the One-World Government or New World Order plot template, wherein globalist economic and political forces aim at undermining the sovereignty and independence of free nations (Bieber 2020). This nefarious activity is prompted by a catastrophic event that allows hidden operatives to seize power and consolidate authority in ways that subvert constitutionally mandated rights, freedoms, and legal protections. The ultimate goals and instruments of this process vary based on the flexible contours of a given conspiracy theory; however, it is almost always aimed at the suppression of the beliefs and lifestyles of individuals and groups who oppose the globalist mantle of control. The theory exposing the conspiracy represents the alarming truth for the community under threat, a truth that must be propagated to ensure that community’s survival and existence. The COVID-19 conspiracy cluster has all of the main components that the conspiracy mindset thrives on: a public emergency or crisis creating a pretext for draconian measures; plausible and verifiable elements that support conspiracy claims; wealthy and powerful actors allegedly behind the conspiracy; and plentiful outlets for the conspiracy to spread, self-confirm, and evolve (Ball and Maxmen 2020; Evstatieva 2020).

The COVID-19 and 5G technology conspiracy tandem offers an instructive example of this process in action. The virus’ unexpected and mysterious genesis, its rapid international spread, and its exceptionally high communicability and mortality necessitated a coordinated response from the levers of global governance and public health authority that brought most social and economic activity to a standstill (Caduff 2020). Its origins within communist China, in a city (Wuhan) with an international laboratory for studying communicable diseases, instantly gave rise to speculation on covert germ warfare testing and other possible geo-political motivations for a country that is both internally repressive and globally ascendant. The prolonged shock of quarantines, lockdowns, and social distancing accompanied an evolving information landscape from the international stakeholders charged with managing the disease—namely, the World Health Organization, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the U.S. National Institutes for Health, the United Nations, and other entities already enveloped in conspiracy theory lore and subject to popular distrust (Freeman et al. 2020).

The emergence of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—as an entity that bridges the domains of global health initiatives, vaccinations, and technology—into the pandemic management conversation further fueled the fire. In combination with 5G Internet technology, the “Plandemic” conspiracy theory emerged fully formed from the not-so-dark corners of the web (Ball and Maxmen 2020). The overarching thrust of the conspiracy goes something like this: the COVID-19 pandemic was deliberately created by the global financial and political elite to spread the disease as far and wide as possible; along with the disease they created a vaccine, which they would distribute at their discretion when the populace was sufficiently pacified; the vaccine would secretly include a microchip that allows monitoring and manipulation when injected into individuals, thus allowing the powerful cabal to assert further control at a personal level; the microchips are then activated and control is operationalized through the electromagnetic waves generated by 5G network towers, which have been a popular subject of conspiratorial speculation since well before the pandemic (“Debunking COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories” 2020).

The pernicious spread of COVID-19/5G conspiracy theory mirrors that of the actual virus and is similarly characterized by tragic ironies (Imhoff and Lamberty 2020). For example, it hardly seems a coincidence that countries experiencing the highest infection and fatality rates are also those with authoritarian-minded leaders who frequently seek to downplay the seriousness of or obfuscate information around the pandemic, while also touting their singular accomplishments in managing the disease and resulting fallout (Leonhardt and Leatherby 2020). Many of these same leaders often embrace conspiracy theories promulgated by their political base, setting the tone for violent attacks against people of Asian descent (whether or not they are actually Chinese), destruction of communication towers and other infrastructure (whether or not they are linked to 5G networks), and premature rejection of COVID-19 vaccines (whether or not they prove safe and effective) (Douglas 2020; Goodman and Carmichael 2020; Vincent 2020). This top-down endorsement of conspiracy theories incentivizes and excuses personal behavior that is likely to impact the health and safety of others far removed from the initial decisions and chain of activity spurred on by the conspiracy mindset (Kovalcikova and Tabatabai 2020). The purposeful and accidental dispersion of misinformation, disinformation, and fake news through social and traditional media ensures an ever-deepening crisis of infection and harm in areas where the official leadership is unable or unwilling to combat the negative consequences of the disease (Evanega et al. 2020).

Patterns of personal information consumption—which are increasingly polarized and homogenous—represent a significant connecting thread between the conspiracy mindset and the influence of larger socio-political factors that help foster conspiracy beliefs. For example, recent polling by the Pew Research Center suggests a correlation between skepticism of verifiable facts and belief in false conspiracy theories among American respondents who strictly limit their exposure to certain news media outlets (Jurkowitz and Mitchell 2020; Mitchell et al. 2020b). As of April 2020, nearly 30% of Americans polled indicated that they believed COVID-19 was made in a lab, and approximately 62% believed that the media had slightly or greatly exaggerated the risks of the pandemic (Mitchell and Oliphant 2020; Romano 2020). Perhaps not surprisingly, those with the most limited news diet were more likely to perceive information as wrong or fraudulent in their interactions with the general news media, and tended to consider most trustworthy the information they received from their “own” resources (Mitchell and Oliphant 2020). Increasingly, these resources are determined by what they encounter online in their constructed social media environments; and the more they rely on this, the less likely they are to accept basic factual information and engage with social and political issues that should cause them concern (Mitchell et al. 2020a).

Meanwhile, the exposure to conspiracy theories, fake news, misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda proliferates in these environments, further reinforcing popular uncertainty and mistrust around COVID-19 (Jamieson and Albarracin 2020). Ahmed et al. (2020) demonstrated how quickly the COVID-19/5G conspiracy cluster spread across Twitter in the early days of the pandemic, when facts and information about the disease were still relatively fluid and official governing bodies were in the process of formalizing courses of action. The exponential speed and reach of the conspiracy theory helped fill the information vacuum that often exists in emergency situations, but perhaps what was most troubling was its ability to penetrate outside of the information bubbles where it first appeared. Ahmed et al. (2020) found that information on COVID-19/5G conspiracy was as likely to be shared by those who opposed it or had no discernible opinion of it as it was by those who believed it. The viral nature of networked social media all but assures wide dissemination regardless of belief or believability, especially in the absence of any authority figure to refute the conspiracy theory or halt its spread (Bruns, Harrington, and Hurcombe 2020). Lacking the wide deployment of kill-switches or circuit breakers similar to those designed to prevent stock market meltdowns, the need for responsible and reliable information intermediaries seems more urgent than ever (Bond 2020).

4 LIS in the Current Epistemic Crisis

In many ways, the COVID-19 conspiracy theories and myriad others that are so pervasive in the infosphere correspond to the resurgent fake news phenomenon. Indeed, conspiracy theories are dependent on an ever-evolving dynamic that blends misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, and skepticism. Librarians and other information professionals were not slow to engage with the issue of fake news when it became a dominant political and social trope in the latter half of the 2010s. The range of professional responses to the perceived threat includes building balanced collections, providing authoritative information to inquirers, assisting journalists in refuting fake news, educating users about its negative effects, participating in initiatives to rescue oceanographic and environmental databases under threat, and emphasizing the role of libraries as safe spaces where users can access information without harassment and discrimination (Alvarez 2016; Bern 2017; Flynn and Hartnett 2018; Haasio, Mattila, and Ojaranta 2018; Hoover 2017; Lor 2018; Pun 2017).

Of all the library responses, the inculcation of information and media literacy features most prominently in the relevant professional discourse. The term information literacy first appeared in print in 1974, and since the 1990s, information literacy in its various guises has been a major growth area in LIS scholarship and praxis.[2] As such, much of the related literature is practical and pedagogical in nature—how to teach information literacy effectively. As an area of professional emphasis, information literacy is attractive for academic librarians in particular, because those seeking faculty status and scholarly credibility can utilize the wide range of pedagogical approaches and instructional contexts that lend themselves to empirical research.

In light of the emphasis placed on information literacy in the library profession, and in spite of three decades of intensive work teaching and researching it, it seems counterintuitive that the impact of fake news seems to have only grown during this time. If recent electoral behavior in the UK and the US is any indication, widespread teaching of information literacy in schools and colleges has had little effect beyond academe. However, librarians remain undiscouraged and have seized upon the “opportunity” offered by the need to combat fake news. Some have done so with almost indecent haste. In a recent article, Eva and Shea (2018, 168) enthused:

… “fake news” is the topic du jour. And while it’s not a good news story for the world in general, it’s presenting a great opportunity for libraries to show their worth. The heightened awareness of the need for information literacy—media literacy, digital literacy, and all the other literacies associated with it—is a wonderful opportunity for libraries to show that they are as relevant and important today as they ever were, perhaps even more so.

While many librarians advocate for information literacy as a means of combating fake buschmannews, it is evident that some are seeking more innovative and effective methods of teaching students by focusing on social media, critical thinking skills, and hands-on programs (Johnson and Ewbank 2018; Mooney, Oehrli, and Desai 2018; Neely-Sardon and Tignor 2018; Ponzani 2018; Rush 2018). Others have adopted more nuanced approaches, informed by a better understanding of the phenomenon through user-centered research (Aharony et al. 2017; LaPierre and Kitzie 2019; Rose-Wiles 2018). Yet others are much more critical of librarians’ information and media literacy efforts. Indeed, there is a growing literature questioning the effectiveness of information literacy. Those who critique librarians’ efforts, and call for rethinking it, often do not believe it is effective, mainly because it is undertaken without adequate understanding of the social, political, psychological, and epistemological issues (and how these relate to each other) underlying fake news and its reception (Barclay 2019; Bluemle 2018; Fister 2017; Lamb 2017; Sullivan 2019).

There are also objections on ideological grounds. For example, Buschman (2019) critiques the neoliberal, instrumental, and technocratic biases inherent in approaches to information literacy and fact checking. While libraries were traditionally regarded as bulwarks of democracy, this relationship has been critically re-examined in light of recent social, political, and technological developments (Braddock 2020; Buschman 2017). Similarly, adherents of contemporary critical librarianship and social justice activism raise questions about library neutrality in social contexts characterized by systemic injustice, where the cultural and media landscapes are dominated by the voices of elite, white, heterosexual, Christian males. Some argue that in such a context neutrality constitutes tacit support of an oppressive system (Branum 2008; Buschman 2018; Farkas 2017; Keer and Bussman 2019). On the other side of this debate are those who argue that librarians can and should maintain professional neutrality while serving individual clients and assisting them in developing skills for critical information use, but respecting their right to make their own decisions (Anderson 2017).

In contrast with the (primarily American) soul-searching about the actions and duties of LIS workers in the face of the Trump-era fake news phenomenon and its associated problems, it is worth noting some Italian authors writing in defence of library neutrality. Zanotti (2018, 453) complains about a “repressive tolerance of an upside-down inquisition,” which, by tolerating and standardizing everything, in fact rejects every contrary view. Roncaglia (2018, 87) attempts to find a balance between library neutrality and social responsibility, suggesting that strategies and instruments be defined “for a ‘rational’ public and transparent negotiation between different values, all worthy of consideration and protection.” He recommends that librarians “should aspire not to an impossible neutrality but rather to principles of rationality, publicness and transparency” (2018, 90).

The issue of neutrality is multifaceted and multilevel. At a deep level, critical librarians and others argue that library neutrality simply reinforces built in societal biases. In this regard, neutrality is neither desirable nor actionable in diverse and complex modern library settings, and claims of neutrality in the past were mostly a charade aimed at perpetuating underlying power relationships between social actors. At a more surface level, however, neutrality is often manifested in the belief that library users are entitled to any information they ask for—a sort of laissez-faire position that says to give people the information they want, regardless of what it is or what they do with it. The ethical implications of such neutrality were tested in oft-cited experiments conducted by Robert Hauptman (1976) and Robert C. Dowd (1989), where information was deliberately sought from a variety of librarians on illegal and potentially harmful activities. Hauptman (1976) noted that none of the librarians he approached refused to help him find information on bomb-making even as he indicated that he might use it to destroy a house. Similarly, librarians were cooperative, if not entirely supportive, in helping Dowd (1989) locate information on how to free-base cocaine. Hauptman considered the librarian response an appalling abrogation of professional duties, while Dowd rejected the idea that a librarian’s facilitation role in a patron’s right to access dangerous information presented an irreconcilable ethical conflict (Hauptman 1996).

These experiments demonstrate that a sense of responsibility and situational context must inform librarian decision-making in such ethically fraught interactions. However, the specific instances they relate in no way compare to the world altering scale of the current infodemic. The prospect of a destroyed building or individual drug use are relatively unimportant when considering the dire implications of inaccurate or inadequate information provision in a global health crisis, especially when so much of that information is characterized by a fundamental epistemic rift along political and ideological lines. Indeed, the preventable loss of life continues with no clear end in sight, and it will take decades to fully absorb and comprehend the social impact of the pandemic. There is no way to seriously claim that librarians and other information professionals could have predicted what is happening right now and much less done anything to prevent it. In addition, our ability to make any difference beyond our institutions is also limited, especially if we continue to “aid and abet egregiously antisocial acts” with a laissez-faire approach that favors dubious professional obligations over principled judgements (Hauptman 1996, 329). We propose that a more defensible ethical stance begins with reconsidering the concept of truth across LIS—how essential truths might be reached and understood.

5 Is Truth Relevant to LIS?

In a long essay on post-truth, fake news, and intellectual neutrality in the library, Riccardo Ridi (2018) argues that truth is not a very relevant concept for librarians because there are many different levels of truth and large parts of library holdings cannot be classified as true or false. Determining the veracity of documents is, in many cases, beyond the competence of librarians; hence, fact checking should be done by clients, not by librarians. However, the library is a suitable venue for this activity since librarians have resources and skills in evaluating the “paratext” of documents, which refers to descriptive material supplied by the authors, editors, printers, and publishers (Ridi 2018, 476). This includes the front and back matter, editor’s notes, and the design as distinct from the substance of the document. Ridi supports the professional neutrality of the librarian, which he considers a defence against the twin temptations of indulging in propaganda and exercising censorship.

Underlying this and similar conversations are nagging questions about truth in society. Who decides what is true? As indicated in the preceding discussion of conspiracy theories and fake news, the relationship between information and truth is complex. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights refers to opinion, expression, information, and ideas, but truth is not mentioned.[3] In its statement of principles, the organization Right2Know refers to a right of people to “share information, including opinion” and the rights and duties of media to “access and disseminate information, including opinion, freely and fairly” in the interests of accountability, transparency, and informed public participation (Right2Know Campaign n.d.). These precede a statement on Truth and Quality of Information asserting: “The rights to access information must be served through the provision of information that is reliable, verifiable and representative of the data from which it is derived, and must include the right to access source data itself. Information must be provided transparently and equally, untainted by partisan interests” (Right2Know Campaign n.d.).

Here it is implied that information is true which is reliable (the recipients of the information can be sure that it is truthful), verifiable (it is possible for recipients to check and confirm it), and representative of the data from which it is derived (it is possible to determine that the data on which the information is based has not been distorted or selectively omitted). In the present era of alternative facts, fake news, and conspiracy theories, the issue of truth surfaces on a daily basis at the highest levels of public discourse. If citizens, journalists, and librarians militate to combat this reality, there seems to be a basic assumption that we are entitled to the truth. But, to the extent that they deal with users’ rights, standard practices based on codes of ethics in LIS are mainly concerned with the right to documents, information, and (sometimes) knowledge—but not necessarily the truth.

Librarians mostly assume that access to information is per se beneficial. LIS disciplinary literature bristles with statements asserting that information is useful and essential for personal development, social cohesion, democratic participation, economic growth, and other desirable features of contemporary life. This reflects two other implicit assumptions. First, that most information is mostly truthful—even taking into account the huge and growing volume of misinformation, disinformation, fake news, and conspiracy theories discussed above. Thus, the negative potential of information is mostly neglected. LIS scholars and practitioners may define information in such a way that misinformation and disinformation are excluded (and the notion of truth is taken for granted), but any distinctions or qualifications seldom surface in library policies, procedures, and institutional activity, and whatever position the library takes is likely not perceptible to most users.

A second assumption is that information mostly does no harm. Given that librarians often strenuously argue that unfettered information access is beneficial, the assumption that it can do no harm appears disingenuous. It embodies an asymmetrical concept of information potential. On the basis of this assumption, the LIS profession often exhibits a categorical and even dogmatic opposition to any form of censorship or selectivity. We have argued that a great deal of information is potentially untruthful and harmful. Therefore, we suggest that the emphasis in LIS on the right to information is idealistic and unrealistic. LIS workers need to face the complex and unpopular issue of truth and untruth in the materials they collect and make available, but this must begin with a fundamental rethinking of our ethical assumptions on these notions. A relevant input into this larger discussion of truth is provided by the concept of alethic rights, or rights to truth, proposed by the noted Italian philosopher Franca d’Agostini.

6 Alethic Rights—Rights to Truth

The term “alethic” comes from the Greek word ἀλήθεια, aletheia, meaning truth or disclosure—literally a state of not being hidden. D’Agostini defines truth in the traditional Platonic realistic sense as knowledge of things as they really are. For an audience of critical librarians and information workers, this may be hard to swallow. In modern philosophy, the traditional realistic notion has been eclipsed by the “deflationary” theory of truth. There are several varieties of deflationism. Distinguishing them is quite a technical matter and beyond the scope of this paper, but the upshot is that doubt is cast on the very concept of truth: “philosophers looking for the nature of truth are bound to be frustrated … because they are looking for something that isn’t there” (Stoljar and Damnjanovic 2010, sec. 1, para. 2). A general contemporary skepticism that allows everyone to have their own truth is a reaction to the misuse of the concept in religious and ideological dogmas. D’Agostini (2017, 33–35) points out that accepting the “truth function” is used for inferring, doubting and discussing, and is essential for skepticism. From a practical perspective, we can add that the traditional realistic concept of truth has the advantage of corresponding to the laypersons’ understanding of truth.

D’Agostini considers truth as both a legal good and a political good. As a legal good, withholding, distorting, and falsifying truth is a violation of a person’s rights and can be justiciable. An extreme example would be a medical experiment in which participants are not told of life-threatening conditions and in which they are given only a placebo, as in the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study (Cave and Holm 2003). As a political good, truth is essential for conversation and cooperation among political agents and for the functioning of social institutions. In either case, there must be a relation of adequacy between language and the world (the “truth function”). An illustration is the indiscriminate labelling by certain politicians of anything that displeases them as fake news, and of attaching this term to certain media, as if to inoculate their audience against infection by the truth. Ultimately this distortion makes rational political discourse impossible, especially in democratic systems, and can lead to dysfunctional policies and actions, as seen in the ineffective responses by certain governments to the COVID-19 pandemic. D’Agostini writes that “democratic life is based on the opinions (true or false) of politicians and citizens, therefore true power in democracy is power of truth and falsehood, therefore of the truth-function, and how we make use of it” (Ferrera and D’Agostini 2018).

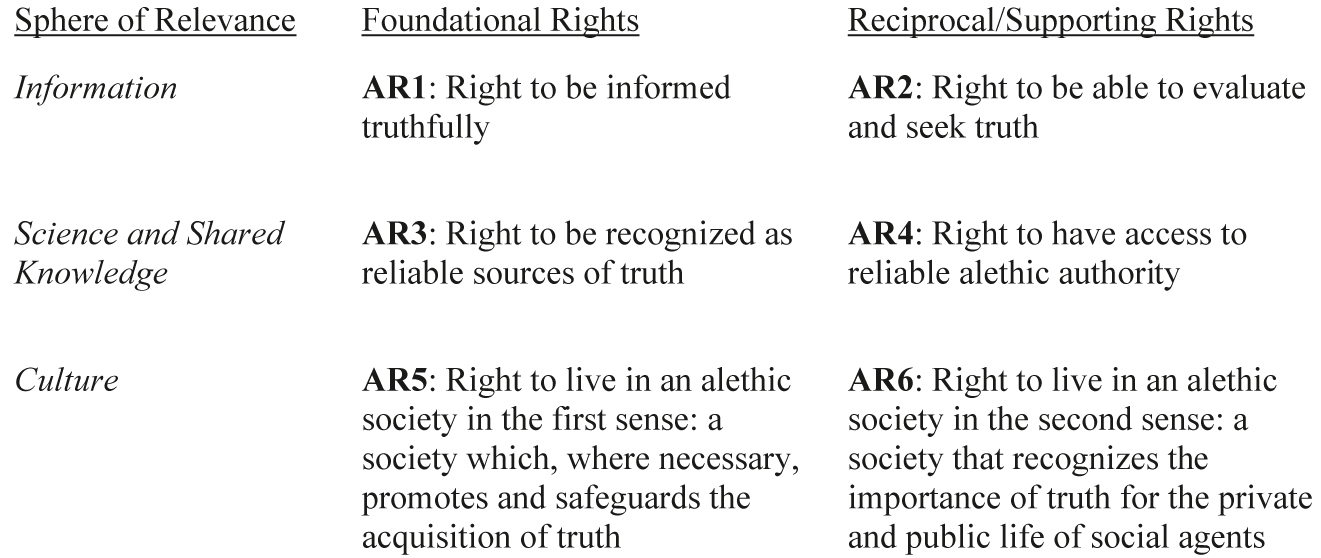

For purposes of discussion D’Agostini proposed a symmetrical set of six alethic rights (see Figure 1). They concern three spheres in which the truth is regarded as a socially important good, those of information, science and shared knowledge, and culture. Here, we have added a distinction to d’Agostini’s model between foundational and reciprocal or supporting rights, as this suggests a mutually reinforcing relationship between them. D’Agostini explains that the six rights are “progressively corrective” in the sense that the observance of a right serves to correct or limit the disproportionate observance of the preceding rights. For the non-philosophical reader, they may also appear to become progressively abstract and difficult to distinguish.

D’Agostini’s alethic rights.

The first two rights (AR1 and AR2) are concerned with the knowledge of truth. Citizens have the right to be informed truthfully about reasons for government decisions, public finances, the moral and professional trustworthiness of their representatives, health and climate issues, and so forth. This right can be defended on practical (economic and strategic) grounds as well as on ethical grounds. Recipients may suffer injury by accepting and acting on untruths. This is illustrated by the health hazards to which citizens may be exposed as a result of outdated, inaccurate, or fanciful information about how to prevent COVID-19 infections, for example. The right to be able to evaluate and seek truth includes the right to receive adequate schooling imparting plausibly true information about the natural and human worlds, and to acquire means of improving one’s own knowledge and critically evaluate the information one receives. The current proliferation of information and communication entails risks of confusion between true and false, giving rise to dogmatism and error, with potentially limitless negative social consequences. This implies that citizens should have the right to be in a position to recognize and search for truth, and to distinguish when falsehood is put forward as truth.

The next two rights (AR3 and AR4) are concerned with public recognition of the truth or falsehood of statements and theories. The right to be recognized as reliable sources of truth is personal and institutional. Every human being has the right, as a matter of principle, to be considered as a potential epistemic agent, the carrier of true information. This right is often violated in the case of members of subaltern and marginal groups such as minorities, women, the poor, or immigrants. Echoing Miranda Fricker (2007), D’Agostini here uses the term “testimonial injustice” to refer to the violation of this right. Not only do these individuals suffer injury, but so does society as a whole; by ignoring someone who speaks truth we deprive ourselves and society of the truth, with potentially damaging consequences. We note here that testimonial injustice and hermeneutical injustice are the two forms of epistemic injustices distinguished by Fricker (2007). Although d’Agostini’s essay does not deal with it in any detail, from the perspective of LIS epistemic injustice is a violation of social justice—in particular, justice as recognition, which we define as the recognition of the autonomy and value of every human being (Britz 2008). This form of justice insists on a pursuit of equitable treatment of all people because they are of equal moral dignity.

The right to have access to reliable alethic authority means living in a society that applies truth-oriented evaluation criteria to its scientific systems. Such a right can be seen as an expression of justice as participation, ensuring fair terms of participation at all institutional and societal levels. This enables us to evaluate individual and institutional epistemic agents as true information. Every public participant deserves a hearing, but not all should receive the same kind of hearing. Society has a range of means and institutions to confer credibility, but if the system for assigning credibility is corrupted, this will have serious consequences for society. For example, the role of donors, corporations, and governments in funding research may be problematic and lead to the defunding of research and the suppression or distortion of results. This is well documented in the case of climate science (Climate Council of Australia 2019; Lewis 2015; Waters 2018).

The last two rights (AR5 and AR6) are concerned with the notion of an alethic society or environment, which is characterized by an awareness of the importance of truth and of the risks and opportunities related to the use of truth. D’Agostini identifies two senses of the term alethic society, which explain the subtle distinction between the last two rights. One sense of the term has to do with societal safeguards for truth. The second has to do with a shared awareness that supports the agencies and institutions that safeguard truth. If distortion of the truth is socially acceptable and left unchecked, widespread social skepticism will erode the individual’s motivation to learn, to behave responsibly, or to share knowledge with others. It opens the way to the discrediting of social bonds, resulting in opportunistic misconduct and increasing violence. These rights call for the provision of norms, bodies, and agencies responsible for checking and safeguarding the truth, thus ensuring an alethic society. By safeguarding the truth, society adheres to justice as enablement, which supports self-determination and allows people to make informed decisions for their personal well-being (Britz 2008).

However, an alethic society should not become a dictatorship of truth (d’Agostini 2017, n.p.). The right to live in a culture and society in which the importance of truth (in positive and negative senses) for the private and public life of social agents is recognized requires collective awareness and participation. The institutions required for the exercise of alethic rights are not enough to ensure an alethic society in the full sense, which is characterized by a collective mandate which charges these agencies and bodies with the authentic management of their roles. An alethic society is a society whose members are aware of the nature of the truth concept, of its importance in public life, of the risks inherent in its violation and distortion, and of the risks of using the concept without falling into extremes of dogmatism or skepticism. From an LIS social justice perspective, it is worth relating this to the systemic perspective of epistemic justice as a virtue of social systems, which was developed by Elizabeth Anderson (2012) as a counterpart to Fricker’s concept of individual epistemic virtue.

7 Libraries, Alethic Principles, and the COVID-19 Infodemic

D’Agostini’s suggestion that everyone deserves a hearing, but not all deserve the same hearing, has implications for the notion of “balance” in library collections. As an extreme example, few would argue that literature on astronomy should be balanced by works on astrology or flat earth theory; but should creationism receive as much shelf space as evolution, or global warming denial as much as the peer-reviewed findings of climate scientists? If not, how do librarians decide to whom epistemic authority is assigned? And what about the various alternative scientific paradigms such as African, feminist, and indigenous science? The herbal cure for COVID-19 promoted by the president of Madagascar is a case in point (Baker 2020). Librarians should take care that in selection of materials they do not ignore the voices of subaltern groups. However, respect for alternative viewpoints must be balanced with the health risks to library clients who may access such information if it is not accurate.

Librarians often feel unqualified to make these calls. But given the hazard constituted by the COVID-19 infodemic, libraries should be wary of potential harm caused by materials espousing views that are unsupported by research findings from legitimate cognitive authorities, even if they only acquire them as specimens for purposes of example and research. When making them available to lay users librarians have a duty to give a sort of “health warning” or other contextual information that puts them in perspective. This of course runs counter to the professional abhorrence of “labelling” materials and it certainly can present a conflict of ethical positions. But in parallel with the right to receive adequate and truthful education, one might posit that citizens have the right to receive adequate supplementary information even if it conflicts with the information originally sought.

Many libraries create web pages and other resources that provide guidelines and list trustworthy sources that can be used for checking facts. As such they tacitly support the agencies, norms, and bodies that produce and vet the information purported to be true or false. We would argue that libraries have a duty to offer their support to these fact-checking organizations by providing them with reference and information services, in addition to disseminating their findings. Unfortunately, as the COVID-19 infodemic reveals, in many countries, it is clear that large swathes of the population have a poor awareness of how to obtain accurate information generally and truthful information about the pandemic specifically—evidence of endemic social injustice. The various instruments of public education have failed in this respect. Similarly, the teaching of information literacy, however much it has been emphasized in libraries and expounded in the literature of the LIS field, has failed to make a significant impact. Other approaches in support of factual public discourse are needed.

D’Agostini calls for the inculcation of philosophical competencies at all levels of education, which is in line with the philosophical tradition of the West. We would go further and argue that information hygiene should be inculcated among all citizens from the earliest age. Just as children are taught to brush their teeth daily and wash their hands after visiting the toilet, we should be teaching them not to believe everything they are told, to recognize trustworthy and untrustworthy sources of information, and not to repeat information that does not come from a trustworthy source. As a moral imperative based on social justice, this would require massive investment analogous to the public hygiene messaging that is still ongoing in many countries. This is well beyond the scope of libraries, but supporting such campaigns is not.

8 Conclusion: Engaging with the Truth—A Challenge for LIS

In LIS, we have a long history of aiming to improve people; for example, encouraging people to read “better literature” and non-fiction rather than popular fiction for self-education and social improvement. In the second half of the twentieth century, this was increasingly viewed as paternalistic and undemocratic. The earlier idealism was eroded by the spread of relativism throughout the social sciences, as manifested in the adoption of critical theory and critical librarianship. Notions of quality and truth were devalued in the postmodernist critique of the logical positivism that gave birth to modern libraries. Librarians abdicated from value-based selection of materials, leaving it to public demand and blanket orders. Clients seeking information were pointed to resources and told to make their own subjective judgments about what was true or not true. The profession retains some of that early paternalism, but now seems to reflect a more activist social justice impulse even among those who might feel more strongly about maintaining librarian neutrality or impartiality. In any event, the question of the truth seems not to factor much into attendant professional discussions.

Ridi has argued cogently that determining truth is not the business of librarians. For this stance, he finds support in the ethical code of the Italian Library Association (Associazione Italiana Biblioteche 2020), which states:

It is not the duty of librarians, unlike other figures (such as parents, teachers, researchers, critics and booksellers), to control or limit—except for specific legal obligations—the access to documents by under age users, or—in general—to express positive or negative evaluations on the documents requested, used or made available to the public. Librarians can provide instructions and advice on the most effective tools and methods for the search, the selection and the evaluation of documents and information, but they refrain from giving advice in professional fields other than their own.

This stance is commonly reflected in literature, ethical codes, and training of the LIS profession around the world. However, the COVID-19 infodemic, which is merely the latest and most striking manifestation of a growing deluge of conspiracy-theory based misinformation and disinformation, requires reconsideration of LIS attitudes and approaches to the truthfulness of materials in the collections we build and the information we provide to users.

Because various institutions have laid claim to being bearers of the truth—truth as determined in terms of religious, political, and ideological dogma—claims to truth are often looked at with suspicion. This is not what is intended by the analysis offered in this article. An alethic culture does not decide what truth is to be believed, but inculcates in members of the society a clear awareness of the use of truth to equip them with the means of disentangling what is true from what is dogmatically declared to be true. Such a system does not rule out skepticism. On the contrary, the truth function is indispensable for inferring, doubting, and discussing. Establishing processes to arrive at the truth is vital for functioning democracies. We would argue that this is a matter of social justice.

It is time for the LIS profession to engage in a discussion about users’ right to truth and our concomitant responsibilities. This implies that truth should be given a higher place in the hierarchy of values which guide the practice of library and information workers. We need to re-evaluate our ethical stance, which was traditionally based on the notions of neutrality, freedom of expression, and objectivity. John Rawls argued that “justice is the first virtue of social institutions just as truth is for systems of thoughts [emphasis added]” (1973, 5). If truth is the core virtue of our systems of thought, then it can indeed be argued that knowing the world “truthfully” (things as they really are) and allowing information about “real things” to be communicated in a truthful way are indeed matters of social justice, freedom, and well-being. Librarians should be the guardians of this truth and it should become the core value underpinning their moral reasoning and sense of social justice.

In support of a right to the truth, it is therefore clear that social justice should be a normative instrument for librarians in the evaluation of the truthfulness of a society. As the first virtue of social institutions, justice sets out important principles for the protection and promotion of truth as the first virtue of our systems of thought. Furthermore, a positive assertion of principles based on social justice should not only protect the truth, but also prevent its distortion. This should stand as a moral imperative for LIS. Future deliberations and research among scholars and practitioners in the LIS field can help determine concrete steps to develop policies and procedures that center truth in information provision, while also investigating the best ways to reach people and communities less receptive to traditional information authorities. Similarly, curricular requirements in LIS schools and ongoing professional training should attempt to equip current and future professionals with perspectives and models for discerning truth that go beyond value-free postmodern skepticism. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the perils of an epistemic free-for-all; librarians must recognize their role in supporting the common base of facts and evidence that social justice requires.

References

Aharony, N., L. Limberg, H. Julien, K. Albright, I. Fourie, and J. Bronstein. 2017. “Information Literacy in an Era of Information Uncertainty.” Proceedings of the Association Information Science and Technology 54 (1): 528–31, https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2017.14505401063.Search in Google Scholar

Ahmed, W., J. Vidal-Alaball, J. Downing, and F. Lopez Segui. 2020. “COVID-19 and the 5G Conspiracy Theory: Social Network Analysis of Twitter Data.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (5): e19458, https://doi.org/10.2196/19458.Search in Google Scholar

Alvarez, B. 2016. “Public Libraries in the Age of Fake News.” Public Libraries 55 (6): 24–7, http://publiclibrariesonline.org/2017/01/feature-public-libraries-in-the-age-of-fake-news/.Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, E. 2012. “Epistemic Justice as a Virtue of Social Institutions.” Social Epistemology 26 (2): 163–73, https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2011.652211.Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, R. 2017. “Fake News and Alternative Facts: Five Challenges for Academic Libraries.” Insights 30 (2): 4–9, https://doi.org/10.1629/uskg.356.Search in Google Scholar

AssociazioneItaliana Biblioteche. 2020. Codice Deontologico dei Bibliotecari: Principi Fondamentali [Librarians’ Code of Ethics: Fundamental Principles]. https://www.aib.it/chi-siamo/statuto-e-regolamenti/codice-deontologico/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Baker, A. 2020. “‘Could It Work as a Cure? Maybe.’ A herbal remedy for Coronavirus is a Hit in Africa, but Experts have their Doubts.” Time. https://time.com/5840148/coronavirus-cure-covid-organic-madagascar/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Ball, P., and A. Maxmen. 2020. “The Epic Battle against Coronavirus Misinformation and Conspiracy Theories.” Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01452-z (accessed January 7, 2021).10.1038/d41586-020-01452-zSearch in Google Scholar

Barclay, D. A. 2019. “The Fake News Phenomenon – An Opportunity for the Library Community to Make a Splash?” Against the Grain 29 (3). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5p09c4gr (accessed January 7, 2021).10.7771/2380-176X.7779Search in Google Scholar

Bern, A. 2017. “Fake News vs. the Democratic Surround.” ALSC Intellectual Freedom Committee. http://www.ala.org/alsc/sites/ala.org.alsc/files/content/professional-tools/fake-news-alan-bern.docx (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Bieber, F. 2020. “Global Nationalism in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Nationalities Papers, https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.35.Search in Google Scholar

Bluemle, S. R. 2018. “Post-facts: Information Literacy and Authority after the 2016 Election.” Portal: Libraries and the Academy 18 (2): 265–82, https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2018.0015.Search in Google Scholar

Bond, S. 2020. “Can Circuit Breakers Stop Viral Rumors on Facebook, Twitter?” NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/09/22/915676948/can-circuit-breakers-stop-viral-rumors-on-facebook-twitter (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Braddock, J. 2020. “Libraries and Authoritarianism 1940, 2020.” LA Review of Books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/libraries-and-authoritarianism-1940-2020/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Branum, C. “The Myth of Library Neutrality.” 2008, https://doi.org/10.17613/M6JP2R.Search in Google Scholar

Britz, J. J. 2008. “Making the Global Information Society Good: A Social Justice Perspective on the Ethical Dimensions of the Global Information Society.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 59 (7): 1171–83, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20848.Search in Google Scholar

Bruns, A., S. Harrington, and E. Hurcombe. 2020. “‘Corona? 5G? or Both?’: The Dynamics of COVID-19/5G Conspiracy Theories on Facebook.” Media International Australia 177 (1): 12–29, https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20946113.Search in Google Scholar

Buschman, J. 2017. “November 8, 2016: Core Values, Bad Faith, and Democracy.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 87 (3): 277–86. https://doi.org/0024-2519/2017/8703-0009.10.1086/692305Search in Google Scholar

Buschman, J. 2018. “The Politics of Academic Libraries: Fake News, Neutrality and ALA.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 44 (3): 430–1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acadlib.2018.04.013.Search in Google Scholar

Buschman, J. 2019. “Good News, Bad News, and Fake News.” Journal of Documentation 75 (1): 213–28, https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-05-2018-0074.Search in Google Scholar

Caduff, C. 2020. “What Went Wrong: Corona and the World after the Full Stop.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly: 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12599.Search in Google Scholar

Cave, E., and S. Holm. 2003. “Milgram and Tuskegee—Paradigm Research Projects in Bioethics.” Health Care Analysis 11 (1): 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025333912720.10.1023/A:1025333912720Search in Google Scholar

Climate Council of Australia 2019. “Climate Cuts, Cover-Ups and Censorship.” https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/climate-cuts-cover-ups-censorship/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

D’Agostini, F. 2017. “Diritti Aletici [Alethic Rights].” Biblioteca Della Libe 52 (218): 5–42, https://doi.org/10.23827/BDL_2017_1_2.Search in Google Scholar

Debunking COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories.” The Medical Futurist. 2020. https://medicalfuturist.com/debunking-covid-19-theories/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Diamond, L. 2020. “Democracy versus the Pandemic: The Coronavirus is Emboldening Autocrats the World over.” Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-06-13/democracy-versus-pandemic (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Dimock, M. 2019. “An Update on Our Research into Trust, Facts, and Democracy.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/2019/06/05/an-update-on-our-research-into-trust-facts-and-democracy/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Doherty, C., and J. Kiley. 2016. “Key Facts about Partisanship and Political Animosity in America.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/06/22/key-facts-partisanship/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Douglas, K. M. 2020. “Psychological Science and COVID-19: Conspiracy Theories.” Association for Psychological Science Coronavirus News Source. https://www.newswise.com/coronavirus/psychological-science-and-covid-19-conspiracy-theories/?article_id=732369 (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Douglas, K. M., R. M. Sutton, and A. Cichocka. 2017. “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 26 (6): 538–42, https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417718261.Search in Google Scholar

Douglas, K. M., J. E. Uscinski, R. M. Sutton, A. Cichocka, T. Nefes, C. Sian Ang, and F. Deravi. 2019. “Understanding Conspiracy Theories.” Advances in Political Psychology 40, no. 1 : 3–35 https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12568.Search in Google Scholar

Dowd, R. C. 1989. “I Want to Find Out How to Freebase Cocaine or yet Another Unobtrusive Test of Reference Performance.” The Reference Librarian 11 (25–26): 483–93.10.1300/J120v11n25_22Search in Google Scholar

Eva, N., and E. Shea. 2018. “Marketing Libraries in an Era of ‘Fake News’.” Reference and User Services Quarterly 57 (3): 168–71, https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.57.3.6599.Search in Google Scholar

Evanega, S., M. Lynas, J. Adams, and K. Smolenyak. 2020. “Coronavirus Misinformation: Quantifying Sources and Themes in the COVID-19 ‘Infodemic’.” Cornell Alliance for Science. https://allianceforscience.cornell.edu/misinformation-disinformation/ (accessed October 1, 2020).10.2196/preprints.25143Search in Google Scholar

Evstatieva, M. 2020. “Anatomy of a COVID-19 Conspiracy Theory.” NPR All Things Considered. https://www.npr.org/2020/07/10/889037310/anatomy-of-a-covid-19-conspiracy-theory (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Eysenbach, G. 2002. “Infodemiology: The Epidemiology of (Mis)Information.” The American Journal of Medicine 113 (9): 763–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01473-0.Search in Google Scholar

Farkas, M. 2017. “Never Neutral: Critical Librarianship and Technology.” American Libraries. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2017/01/03/never-neutral-critlib-technology/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Ferrera, M., and F. d’Agostini. 2018. “Diritti Aletici e Informazione. La Verità è un Bene da Tutelare [Alethic Rights and Information. The Truth is an Asset to be Protected].” Corriere della Sera 30. http://www.corriere.it/la-lettura/18_gennaio_30/diritti-aletici-fake-news-cultura-dibattito-politica-notizie-societa-213925bc-05d4-11e8-b2bd-b642cbae90d8.shtml (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Fister, B. 2017. “Practicing Freedom for the Post-Truth Era.” Paper presented at the Marjorie Whetstone Ashton Annual Lecture, University of New Mexico Libraries, Albuquerque, New Mexico, https://doi.org/10.17613/M6H35Q.Search in Google Scholar

Flynn, K. A., and C. J. Hartnett. 2018. “Cutting through the Fog: Government Information, Librarians, and the Forty-Fifth Presidency.” Reference and User Services Quarterly 57 (3): 208–16, https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.57.3.6608.Search in Google Scholar

Freeman, D., F. Waite, L. Rosebrock, A. Petit, C. Causier, A. East, L. Jenner, A.-L. Teale, L. Carr, S. Mulhall, E. Bold, and S. Lambe. 2020. “Coronavirus Conspiracy Beliefs, Mistrust, and Compliance with Government Guidelines in England.” Psychological Medicine: 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001890.Search in Google Scholar

Fricker, M. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237907.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Froehlich, T. J. 2019. “The Role of Pseudo-cognitive Authorities in the Dissemination of Fake News.” Open Information Science 3: 115–36, https://doi.org/10.1515/opis-2019-0009.Search in Google Scholar

Goodman, E. P. 2020. “Digital Information Fidelity and Friction.” Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University. https://knightcolumbia.org/content/digital-fidelity-and-friction (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Goodman, J., and F. Carmichael. 2020. “Coronavirus: 5G and Microchip Conspiracies Around the World.” BBC Reality Check. https://www.bbc.com/news/53191523 (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Griffin, L., and A. Neimand. 2017. “Why Each Side of the Partisan Divide Thinks the Other is Living in an Alternate Reality.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/why-each-side-of-the-partisan-divide-thinks-the-other-is-living-in-an-alternate-reality-71458 (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Haasio, A., M. Mattila, and A. Ojaranta. 2018. “The Role of Libraries in Avoiding Hate Speech and False Information.” Library & Information Science Research 22: 9–15.Search in Google Scholar

Hauptman, R. 1976. “Professionalism or Culpability? An Experiment in Ethics.” Wilson Library Bulletin 50: 626–7.Search in Google Scholar

Hauptman, R. 1996. “Professional Responsibility Reconsidered.” RQ 35 (3): 327–9.Search in Google Scholar

Hofstadter, R. 1964. “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Harper’s Magazine. https://harpers.org/archive/1964/11/the-paranoid-style-in-american-politics/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Hoover, A. 2017. “The Fight against Fake News is Putting Librarians on the Front Line – and They Say They’re Ready.” Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/The-Culture/2017/0215/The-fight-against-fake-news-is-putting-librarians-on-the-front-line-and-they-say-they-re-ready (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Illing, S. 2020. “‘Flood the Zone with Shit’: How Misinformation Overwhelmed Our Democracy.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/1/16/20991816/impeachment-trial-trump-bannon-misinformation (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Imhoff, R., and P. Lamberty. 2020. “A Bioweapon or Hoax? The Link between Distinct Conspiracy Beliefs about the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak and Pandemic Behavior.” Social Psychological and Personality Science: 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620934692.Search in Google Scholar

Jamieson, K. H., and D. Albarracin. 2020. “The Relation between Media Consumption and Misinformation at the Outset of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in the US.” The Harvard Kennedy School of Misinformation Review 1: 1–22, https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-012.Search in Google Scholar

Johnson, S. T., and A. D. Ewbank. 2018. “Heuristics: An Approach to Evaluating News Obtained through Social Media.” Knowledge Quest 47 (1): 8–14.Search in Google Scholar

Jurkowitz, M., and A. Mitchell. 2020. “About One-fifth of Democrats and Republicans Get Political News in a Kind of Media Bubble.” Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2020/03/04/about-one-fifth-of-democrats-and-republicans-get-political-news-in-a-kind-of-media-bubble/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Keer, G., and J. D. Bussman. 2019. “A Case for a Critical Information Ethics.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 2 (1), https://doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v2i1.57.Search in Google Scholar

Kovalcikova, N., and A. Tabatabai. 2020. “Five Authoritarian Pandemic Messaging Frames and How to Respond.” German Marshall Fund of the United States. https://www.gmfus.org/publications/five-authoritarian-pandemic-messaging-frames-and-how-respond (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Lamb, A. 2017. “Fact or Fake? Curriculum Challenges for School Librarians.” Teacher Librarian 45 (1): 56–60.Search in Google Scholar

LaPierre, S. S., and V. Kitzie. 2019. “‘Lots of Questions about Fake News’: How Public Libraries Have Addressed Media Literacy, 2016-2018.” Public Library Quarterly 38 (4): 428–52, https://doi.org/10.1080/0161846.2019.1600391.Search in Google Scholar

Leonhardt, D., and L. Leatherby. 2020. “Nations Led by Populists See Fastest Virus Spread: [Foreign Desk].” New York Times. https://ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/docview/2409466068?accountid=15078 (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, T. 2015. “If Florida Censors Climate Change Talk, It’s Not Alone.” Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/Science/2015/0310/If-Florida-censors-climate-change-talk-it-s-not-alone (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Lor, P. J. 2018. “Democracy, Information, and Libraries in a Time of Post-truth Discourse.” Library Management 39 (5): 307–21, https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-06-2017-0061.Search in Google Scholar

Merriam-Webster. n.d. Words We’re Watching: ‘Infodemic’.https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/words-were-watching-infodemic-meaning (accessed August 1, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Mitchell, A., and J. B. Oliphant. 2020. “Americans Immersed in COVID-19 News; Most Think Media are Doing Fairly Well Covering It.” Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2020/03/18/americans-immersed-in-covid-19-news-most-think-media-are-doing-fairly-well-covering-it/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Mitchell, A., M. Jurkowitz, J. Baxter Oliphant, and E. Shearer. 2020a. “Americans Who Mainly Get Their News on Social Media are Less Engaged, Less Knowledgeable.” Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2020/07/30/americans-who-mainly-get-their-news-on-social-media-are-less-engaged-less-knowledgeable/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Mitchell, A., M. Jurkowitz, J. B. Oliphant, and E. Shearer. 2020b. “Political Divides, Conspiracy Theories and Divergent News Sources Heading into 2020 Election.” Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2020/09/16/political-divides-conspiracy-theories-and-divergent-news-sources-heading-into-2020-election/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Mooney, H., J. A. Oerhli, and S. Desai. 2018. “Cultivating Students as Educated Citizens: The Role of Academic Libraries.” In Information Literacy and Libraries in the Age of Fake News, edited by D. E. Agosto, 136–50. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.10.5040/9798400670091.ch-011Search in Google Scholar

Neely-Sardon, A., and M. Tignor. 2018. “Focus on Facts: A News and Information Literacy Instructional Program.” The Reference Librarian 59 (3): 108–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/027638877.2018.1468849.Search in Google Scholar

Ponzani, V. 2018. “L’alfabetizzazione Sanitaria: Biblioteche e Bibliotecari per il Benessere dei Cittadini.” AIB Studi 57 (3): 433–43, https://doi.org/10.2426/aibstudi-11751.Search in Google Scholar

Pun, R. 2017. “Hacking the Research Library: Wikipedia, Trump, and Information Literacy in the Escape Room at Fresno State.” The Library Quarterly 87 (4): 330–6, https://doi.org/10.1086/693489.Search in Google Scholar

Rainie, L., and A. Perrin. 2019. “Key Findings about American’s Declining Trust in Government and Each Other.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/07/22/key-findings-about-americans-declining-trust-in-government-and-each-other/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Rawls, J. 1973. A Theory of Justice. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ridi, R. 2018. “Livelli di Verita: Post-Verita, Fake News e Neutralità Intellettuale in Biblioteca.” AIB Studi 58 (2): 455–77, https://doi.org/10.2426/aibstudi-11833.Search in Google Scholar

Right2Know Campaign. “Mission, Vision, and Principles.” https://www.r2k.org.za/about/mission-vision-and-principles/ (accessed September 15, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Roberts, D. 2019. “Donald Trump and the Rise of Tribal Epistemology.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/3/22/14762030/donald-trump-tribal-epistemology (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Romano, A. 2020. “Study: Nearly a Third of Americans Believe a Conspiracy Theory about the Origins of the Coronavirus.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/covid-19-coronavirus-us-response-trump/2020/4/12/21217646/pew-study-coronavirus-origins-conspiracy-theory-media (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Roncaglia, G. 2018. “Fake News: Bibliotecario Neutrale o Bibliotecario Attivo?” AIB Studi 58 (1): 83–93, https://doi.org/10.2426/aibstudi-11772.Search in Google Scholar

Rosenberg, S. W. 2019.“Democracy Devouring Itself: The Rise of the Incompetent Citizen and the Appeal of Right Wing Populism.” UC Irvine Previously Published Works. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8806z01m (accessed March 1, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Rose-Wiles, L. 2018. “Reflections on Fake News, Librarians, and Undergraduate Research.” Reference and User Services Quarterly 57 (3): 200–4, https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.57.3.6606.Search in Google Scholar

Rush, L. 2018. “Examining Student Perceptions of Their Knowledge, Roles, and Power in the Information Cycle: Findings from a ‘Fake News’ Event.” Journal of Information Literacy 12 (2): 121–30, https://doi.org/10.11645/12.2.2484.Search in Google Scholar

Stoljar, D., and N. Damnjanovic. 2010. “The Deflationary Theory of Truth.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archive, Fall 2014 Edition. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2014/entries/truth-deflationary/ (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Sullivan, M. C. 2019. “Why Librarians Can’t Fight Fake News.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 51 (4): 1146–56, https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618764258.Search in Google Scholar

Tappin, B. M., L. van der Leer, and R. T. McKay. 2017. “The Heart Trumps the Head: Desirability Bias in Political Belief Revision.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 146 (8): 1143–9, https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000298.Search in Google Scholar

United Nations. 1948. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (accessed October 1, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Vincent, J. 2020. “Something in the Air.” The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2020/6/3/21276912/5g-conspiracy-theories-coronavirus-uk-telecoms-engineers-attacks-abuse (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Washburn, A. N., and L. J. Skitka. 2018. “Science Denial across the Political Divide: Liberals and Conservatives are Similarly Motivated to Deny Attitude-Inconsistent Science.” Social Psychology and Personality Science 9 (8): 972–80, https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617731500.Search in Google Scholar

Waters, H. 2018. “How the U.S. Government is Aggressively Censoring Climate Science.” Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/magazine/summer-2018/how-us-government-aggressively-censoring-climate (accessed January 7, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Zanotti, A. 2018. “La Post-Verita Come Volto di Una Nuova Inquisizione.” AIB Studi 58 (3): 439–53, https://doi.org/10.2426/aibstudi-11835.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Re-thinking Information Ethics: Truth, Conspiracy Theories, and Librarians in the COVID-19 Era

- User Expectations and Acceptance of Library Services at the African Union Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- Health and Safety Information Behaviour of Coal Miners in Pakistan

- Recounting the Empowerment of Women in Rural Areas of KwaZulu-Natal from Information and Knowledge in the Fourth Industrial Revolution Era

- Engaging Children’s Reading with Reflective Augmented Reality

- Evaluating Public Library Events using a Combination of Methods

- Individual Social Capital of Librarians: Results of Research Conducted in 20 Countries

- Announcement

- Best Student Research Paper Award 2021

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Re-thinking Information Ethics: Truth, Conspiracy Theories, and Librarians in the COVID-19 Era

- User Expectations and Acceptance of Library Services at the African Union Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- Health and Safety Information Behaviour of Coal Miners in Pakistan

- Recounting the Empowerment of Women in Rural Areas of KwaZulu-Natal from Information and Knowledge in the Fourth Industrial Revolution Era

- Engaging Children’s Reading with Reflective Augmented Reality

- Evaluating Public Library Events using a Combination of Methods

- Individual Social Capital of Librarians: Results of Research Conducted in 20 Countries

- Announcement

- Best Student Research Paper Award 2021