Abstract

Objectives

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) can cause lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) in immunodeficiency individuals. The pathogenesis of EBV infection depends on its effective recognition and elimination. Our study investigated the effect of peripheral lymphocyte subsets (PLS) on the elimination of EBV.

Methods

A retrospective single-center study included 63 patients with 17 pediatric liver transplant recipients with EBV-induced PTLD (PTLD group) and 46 patients diagnosed with EBV-induced mononucleosis (IM group). Dynamic monitoring of PLS with EBV-DNA loads was performed.

Results

EBV-DNA replicated at a high level (5.2E3∼5.93E7 copies/mL in PBMC) before treatment in all patients in PTLD group. B lymphocytes were the main infected cells. After treatment with Rituximab, the EBV-DNA loads decreased below the lower limit of detection in 10 patients (PTLD-stable disease, PTLD-SD group), and the viral loads replicated at lower level in six patients (PTLD-partial response, PTLD-PR group). In the PTLD-SD group, the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes increased beyond the normal range with the ascending of EBV-DNA loads, then it decreased to the normal range accompanied by the clearance of EBV. In the PTLD-PR group, the CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes kept in the normal range, while the EBV kept on replication.

Conclusions

The increased number of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes occurred in parallel with the decline in EBV-DNA loads, which is the most useful index in estimating the host capacity of immuno-surveillance against EBV.

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a herpesvirus in which over 90 % of the population worldwide has been infected. It has a double-stranded, linear DNA genome enclosed by a protein capsid. The virus transmits primarily through saliva, and transmission via blood and droplets also occurs [1], [2], [3]. The incidence of EBV infection in children is increasing with each passing year, it is characterized by high fever, sore throat, lymphadenopathy, hepatitis, eyelid edema and other inflammatory symptoms accompanied by an increase of atypical lymphocytes (ALY) [4], 5]. Individuals respond differently to EBV infection due to different immune status [6]. Infectious mononucleosis (IM) is an acute infectious disease caused by EBV infection, which is a kind of self-limited disease in patients with normal immune function, and the virus will be cleaned in a few weeks. However, individuals with immunodeficiency may develop lymphoproliferative disorders and malignancies, the virus will be persistently positive for a long time, and it is difficult to be cleared. The development of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) is linked to a deficient cellular immune response due to immunosuppression administered to prevent graft rejection.

At present, the pathogenesis of EBV infection is not completely clear, but the host immune system exerts a key function in the recognition and elimination of EBV infection. Both innate and adaptive immune responses are initiated to clear the virus. The Toll-like receptors (TLRs) of immune cells are activated, triggering an interferon-mediated innate immune response. B lymphocytes express TLR7, dendritic cells express TLR9, and epithelial cells, as well as monocytes, express TLR2. EBV activates the TLRs of immune cells, mediating the expression of downstream factors, stimulating the proliferation of monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) cells. At the same time, humoral and cellular immune responses in the adaptive immune response are activated. EBV primarily targets B lymphocytes and causes changes in the surface antigen of these cells, which in turn triggers CD3+ T lymphocytes’ defense response. CD3+CD4+ lymphocyte is a type of helper T lymphocyte, where the intracellular molecules are phosphorylated to activate the signal transduction process and assist in the activation of B lymphocytes, cytotoxic T cells, and natural killer cells by secreting cytokines. CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte is a cytotoxic type of T-lymphocyte with a killing effect that directly destroys target cells or induces the apoptosis of target cells [7], 8]. Therefore, EBV infection will affect the absolute count and the percentage of peripheral lymphocyte subsets (PLS), and PLS may conversely influence the clearance of virus.

Trends of the PLS and EBV-DNA loads as well as their interaction in EBV-infected patients are still unknown. In this study, we performed dynamic monitoring of PLS and EBV-DNA loads in pediatric liver transplant recipients with PTLD and IM children, to investigate the effect of immune response on the elimination of EBV.

Materials and methods

In a period of 24 months (from January 2021 to December 2022), a total of 63 patients were enrolled in this mono-center retrospective study, including 17 pediatric liver transplant recipients with PTLD (PTLD group) and 46 patients diagnosed as IM (IM group). Based on the response to treatment, PTLD group were divided into PTLD – stable disease (PTLD – SD) group and PTLD – partial response (PTLD-PR) group.

The diagnostic criteria of PTLD followed the Clinical guidelines on Epstein-Barr virus infection in solid organ transplantation recipients and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (2019 edition) [9]. The criteria of PTLD-SD group was that after treatment, the symptoms of PTLD disappeared, and the EBV loads in PBMC declined below the detection limit. The concept of PTLD-PR group was that after treatment, the symptoms of PTLD alleviated. The EBV loads decreased, but they have not declined below the detection limit. The IM was diagnosed following Experts’ consensus on diagnosis and treatment of Epstein-Barr virus infection-related diseases in children [10], 11].

According to our Internal Review Board guidelines, all participants provided full informed consent to participate in the study.

Blood samples for examination of PLS and EBV-DNA loads were collected right after the diagnosis and subsequent management of EBV infection. Blood samples were taken on the 1st, 7th, 14th, 21st, 28th, 35th, 42nd, 60th, 90th, 180th, 270th, and 360th day for PTLD group as well as on the 1st day for IM group.

Detection of peripheral lymphocyte subset

Heparin anticoagulated venous blood was collected from each child and stained with antibodies for the flow cytometry analysis. The antibodies used for the lymphocyte subset analysis included FITC-anti-CD3, PE-Cy7-anti-CD8, PE-anti-CD (16/56), PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-CD45, APC-Cy7-anti-CD4, APC-Alexa Fluor 750-anti-CD19. All cell suspensions were incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Red blood cells were then lysed with the lysing solution, and the cells were then washed and resuspended in 200 µL of PBS. The cells were collected by using the BD FACSCanto II Flow Cytometer. Data obtained were analyzed with the Analysis Software. Based on the scatter signals and with the use of Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780 (Invitrogen), cell debris and dead cells were removed from the analyses.

DNA extraction

DNA extraction was performed using the genomic DNA Blood isolation Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) following the instructions of the manufacturer.

Quantitative real-time PCR assays

EBV-DNA loads were determined by a commercial real-time polymerase chain reaction kit (Epstein–Barr virus PCR kit, Daan Gene Co., Ltd. of Sun Yat-Sen University, China). This kit includes a pair of EBV-specific primers, one single-strand EBV-specific fluorescence probe, PCR reaction solution, thermo-stable DNA polymerase (Taq DNA polymerase), four nucleotide monomers (deoxynucleoside triphosphates, dNTPs). All procedures were conducted following the instructions of the manufacturers. Copy numbers per mL were calculated by interpolation in a standard calibration curve. The lower detection limit of this assay was 500 copies/mL.

Detection of lymphocyte types infected by EBV

B, T and NK cells were isolated from PBMC (Peripheral blood mononuclear cell, PBMC) by immunomagnetic beads, which were analyzed by rt-PCR using EBV gene EBNA1-specific primers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the PASW Statistics 20.0 for Windows software. Variable distribution was detected by the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Variables that were normally distributed were presented as

Results

Clinical characteristics, EBV-DNA loads and lymphocyte types infected by EBV of the study population

A total of 17 pediatric liver transplant recipients (5 males and 12 females) with PTLD who were receiving immunosuppressive therapy were enrolled in this study. The etiology for liver transplantation included congenital biliary atresia (n=13), primary biliary cirrhosis (n=1), urea cycle disorders (n=2) and citrullinemia (n=1). The average age for the operation was (16.41 ± 9.63) months, and the onset time of PTLD after the operation was 12 (6, 18) months.

The main symptoms of PTLD included fever (10/17), abnormal liver function (2/17), lymphnoditis (8/17), stomachache and diarrhea (4/17), leukopenia, thrombocytopenia or anemia (2/17), enterobrosis and intestinal obstruction due to the swollen lymph node (1/17). The pathological type included early lesions (8/17), infectious mononucleosis PTLD (4/17), polymorphic PTLD (3/17), Monomorphic PTLD (Burkitt lymphoma) (1/17) and Monomorphic PTLD (diffuse large B cell lymphoma) (1/17). Patient No. 17 developed hemophagocytic syndrome eventually.

EBV-DNA replicated at a high level before treatment in all patients (5.2E3∼5.93E7 copies/mL in PBMC), and seven of them showed elevated EBV-DNA loads in serum. B lymphocytes were the mainly infected cells among 14 patients, while EBV replicated at a high level in T and NK lymphocytes among four patients (No. 4, 13, 16 and 17). After treatment with Rituximab, the EBV-DNA loads decreased below the lower limit of detection in PBMC and serum among 10 patients (PTLD-SD group), and the viral loads kept replicating at lower levels in six patients (PTLD-PR group). However, the viral load kept replicating at a high level in patient No. 17.

The standard immunosuppressant therapy consisted of Baliximab or Antithymocyte immunoglobulin (ATG) as induction therapy, followed by tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone as immunosuppressant therapy. Minimization of tacrolimus was guided by EBV-DNA levels, serum trough levels of tacrolimus and liver function tests.

After treatment with Rituximab, 10 patients were in a stable state, six patients were in partial response, one patient showed progressive disease and died from hemophagocytic syndrome at last (see Table 1).

Clinical characteristics, EBV-DNA loads and lymphocyte types infected by EBV of the study population.

| No. | Sex | Age, months | Primary disease | Onset time after operation, months | Symptoms | Histology | Loads of EBV-DNA before treatment | Loads of EBV-DNA after treatment, copies/mL | Prognosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC |

Plasma |

T Cell |

B Cell |

NK cell |

||||||||||

| copies/mL | copies/106 MC | PBMC | Plasma | |||||||||||

| 1 | F | 12 | Congenital biliary atresia | 13 | Fever | Early lesions | 1.53E7 | 1.85E4 | 1.1E2 | 5.3E6 | 7.1E2 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 2 | M | 8 | Primary biliary cirrhosis | 24 | Liver dysfunction | Infectious mononucleosis PTLD | 3.0E6 | 2.1E3 | 0 | 2.2E6 | 3.2E2 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 3 | M | 27 | Urea cycle disorders | 9 | Lymphnoditis | Early lesions | 3.2E6 | <500 | 0 | 5.1E6 | 0 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 4 | F | 36 | Urea cycle disorders | 5 | Lymphnoditis | Early lesions | 1.8E6 | 5.6E4 | 8.0E6 | 4.6E3 | 1.5E4 | 2.0E5 | 4.5E3 | PR |

| 5 | F | 24 | Citrullinemia | 5 | Fever and diarrhea | Early lesions | 2.3E7 | 4.2E4 | 0 | 8.9E6 | 0 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 6 | M | 9 | Congenital hepatic fibrosis | 30 | Lymphnoditis | Polymorphic PTLD | 1.67E4 | <500 | 0 | 9.5E2 | 0 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 7 | F | 4 | Congenital biliary atresia | 12 | Fever | Polymorphic PTLD | 6.95E5 | <500 | 1.2E4 | 3.4E5 | 4.3E4 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 8 | F | 12 | Congenital biliary atresia | 12 | Lymphnoditis | Infectious mononucleosis PTLD | 8.1E5 | <500 | 0 | 5.6E4 | 0 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 9 | F | 22 | Congenital biliary atresia | 12 | Lymphnoditis | Early lesions | 3.43E6 | 1.5E3 | 4.3E2 | 5.2E6 | 2.2E2 | 3.4E4 | 9.7E2 | PR |

| 10 | M | 10 | Congenital biliary atresia | 12 | Lymphnoditis | Infectious mononucleosis PTLD | 5.2E3 | <500 | 0 | 1.3E3 | 0 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 11 | F | 5 | Congenital biliary atresia | 6 | Fever and diarrhea | Polymorphic PTLD | 2.0E6 | <500 | 0 | 2.9E6 | 0 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 12 | F | 24 | Congenital biliary atresia | 12 | Fever and lymphnoditis | Infectious mononucleosis PTLD | 2.15E6 | 3.2E3 | 2.3E4 | 4.8E6 | 0 | 1.69E3 | <500 | PR |

| 13 | F | 8 | Congenital biliary atresia | 18 | Fever | Early lesions | 2.34E4 | <500 | 3.32E3 | 0 | 4.2E6 | 8.62E2 | <500 | PR |

| 14 | F | 12 | Congenital biliary atresia | 5 | Fever and diarrhea | Monomorphic PTLD (diffuse large B cell lymphoma) | 4.07E5 | <500 | 0 | 6.2E5 | 0 | 1.05E4 | <500 | PR |

| 15 | F | 12 | Congenital biliary atresia | 8 | Fever and diarrhea | Early lesions | 1.26E5 | <500 | 0 | 1.02E5 | 0 | <500 | <500 | SD |

| 16 | F | 24 | Congenital biliary atresia | 8 | Fever | Early lesions | 9.5E5 | <500 | 6.3E5 | 2.8E4 | 3.3E5 | 1.35E3 | <500 | PR |

| 17 | M | 30 | Congenital biliary atresia | 18 | Fever, lymphnoditis and liver dysfunction | Monomorphic PTLD (Burkitt lymphoma) | 5.93E7 | 8.6E5 | 7.8E7 | 9.5E7 | 8.2E7 | 4.23E7 | 2.3E5 | Progressive disease and death |

-

MC, mononuclear cells; SD, stable disease; PR, partial response.

Peripheral lymphocyte subsets in the IM group, PTLD-SD group and PTLD-PR group

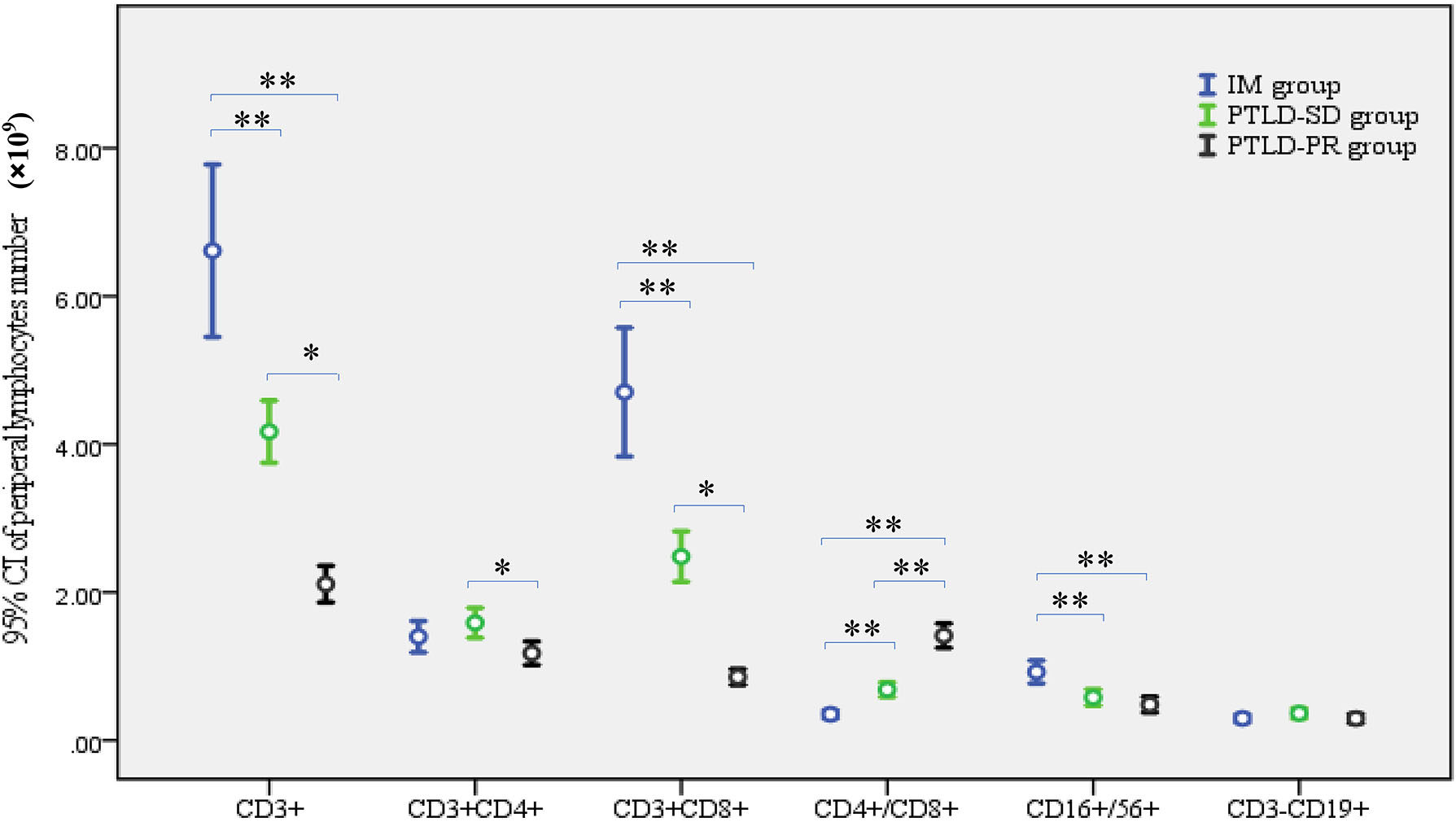

As can be seen from Tables 2-1, 2-2 and Figure 1, there were significant differences in CD3+, CD3+CD8+, CD16+CD56+ lymphocyte numbers and CD4+/CD8+ ratio among the IM group, PTLD-SD group and PTLD-PR group, p<0.05. The CD3+CD8+ lymphocyte numbers in the IM group and PTLD-SD group were obviously higher than that in the PTLD-PR group, which led to the increased number of CD3+ lymphocytes and the decreased CD4+/CD8+ ratio, all p<0.05. What is more, CD3+CD8+ lymphocyte numbers in the IM group were remarkably higher than that in the PTLD-SD group, p<0.05. Besides, the number of CD16+CD56+ lymphocytes in the IM group is higher than that in the PTLD group.

Peripheral lymphocyte subsets among the IM group, PTLD-SD group and PTLD-PR group.

| Number of lymphocytes, ×109/L | IM group | PTLD-SD group | PTLD-PR group | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3+ | 6.62 ± 3.92 | 4.17 ± 1.00 | 2.11 ± 0.57 | 19.676 | 0.000a |

| CD3+CD4+ | 1.40 ± 0.71 | 1.59 ± 0.48 | 1.19 ± 0.36 | 2.799 | 0.066 |

| CD3+CD8+ | 4.71 ± 2.93 | 2.48 ± 0.81 | 0.86 ± 0.24 | 26.223 | 0.000a |

| CD4+/CD8+ | 0.35 ± 0.19 | 0.69 ± 0.24 | 1.42 ± 0.37 | 129.148 | 0.000a |

| CD16+CD56+ | 0.93 ± 0.52 | 0.58 ± 0.26 | 0.49 ± 0.24 | 10.724 | 0.000a |

| CD3−CD19+ | 0.30 ± 0.19 | 0.37 ± 0.17 | 0.30 ± 0.14 | 1.4 | 0.252 |

-

IM, infectious mononucleosis; PTLD-SD, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease-stable disease; PTLD-PR, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease-partial response. ap<0.01.

Peripheral lymphocyte subsets between two groups.

| LSD-t, p | IM group vs. PTLD-PR group | PTLD-SD group vs. PTLD-PR group | IM group vs. PTLD-SD group |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD3+ | 4.50, 0.000b | 2.06, 0.016a | 2.44, 0.001b |

| CD3+CD4+ | 0.22, 0.146 | 0.41, 0.02a | 0.19, 0.21 |

| CD3+CD8+ | 3.85, 0.000b | 1.63, 0.011a | 2.22, 0.000b |

| CD4+/CD8+ | −1.06, 0.000b | −0.73, 0.000b | −0.33, 0.000b |

| CD16+CD56+ | 0.44, 0.000b | 0.10, 0.443 | 0.35, 0.001b |

| CD3−CD19+ | 0.002, 0.962 | 0.07, 0.173 | −0.07, 0.122 |

-

IM, infectious mononucleosis; PTLD-SD, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease-stable disease; PTLD-PR, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease-partial response. ap<0.05, bp<0.01.

Peripheral lymphocyte subsets in the IM group, PTLD-SD group and PTLD-PR group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. IM, infectious mononucleosis; PTLD-SD, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease-stable disease; PTLD-PR, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease-partial response.

The trend of EBV-DNA loads and the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes among pediatric liver transplant recipients in the PTLD-SD group and PTLD-PR group

As can be seen from Table 3 and Figure 2, the trend of EBV-DNA loads and the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes in patients with stable disease differed from those with partial response. In the PTLD-SD group, the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes increased beyond the normal range with the ascending of EBV-DNA loads. After a period (usually ranging from 42 to 360 days), the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes decreased to the normal range accompanied by the clearance of EBV. However, in the PTLD-PR group, the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes kept in the normal range, which was too low to clear the virus. Therefore, the EBV kept on replicating. As for patient No. 17, both the EBV-DNA loads and the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes kept on replicating at a high level due to hemophagocytic syndrome.

The EBV-DNA loads and percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes among pediatric liver transplant recipients in PTLD-SD group and PTLD-PR group.

| PTLD-SD group | PTLD-PR group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBV-DNA loads (copies/mL, Log10) | Percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes, % | EBV-DNA loads (copies/mL, Log10) | Percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes, % | |

| 1st day | 6.02 [4.23, 6.48] | 0.42 ± 0.12 | 3.76 [3.63, 4.90] | 0.32 ± 0.07 |

| 7th day | 5.15 [4.31, 7.17] | 0.42 ± 0.10 | 4.58 [4.52, 4.74] | 0.33 ± 0.06 |

| 21st day | 5.84 [5.48, 6.10] | 0.46 ± 0.09 | 4.90 [4.76, 5.64] | 0.34 ± 0.06 |

| 28th day | 5.51 [4.96, 5.92] | 0.49 ± 0.09 | 4.58 [4.46, 5.61] | 0.34 ± 0.06 |

| 35th day | 4.41 [3.48, 5.31] | 0.50 ± 0.06 | 5.39 [4.53, 6.26] | 0.33 ± 0.07 |

| 42nd day | 3.85 [1.52, 5.31] | 0.51 ± 0.06 | 5.03 [4.48, 5.95] | 0.30 ± 0.03 |

| 60th day | 3.01 [0, 5.29] | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 4.79 [4.50, 5.60] | 0.30 ± 0.04 |

| 90th day | 0 [0, 4.67] | 0.48 ± 0.09 | 4.44 [4.32, 4.74] | 0.29 ± 0.04 |

| 180th day | 0 [0, 1.78] | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 4.26 [4.22, 4.44] | 0.28 ± 0.04 |

| 270th day | 0 [0, 1.46] | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 3.6 [3.03, 4.53] | 0.28 ± 0.04 |

| 360th day | 0 [0, 0] | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 3.98 [3.19, 4.38] | 0.29 ± 0.04 |

-

IM, infectious mononucleosis; PTLD-SD, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease-stable disease; PTLD-PR, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease-partial response.

The trends of EBV-DNA loads and the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes among patients in PTLD-SD group and PTLD-PR group. (A and B) Show the trend of EBV-DNA loads and the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes of patients in PTLD-SD group. (C and D) Show the trend of EBV-DNA loads and the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes of patients in PTLD-PR group.

Discussion

Liver transplantation has become a standard procedure for children with end-stage liver disease, but immunosuppressive drugs have serious side effects in both short and long perspective. Complications caused by EBV infection are frequent, which show as a disease spectrum ranging from asymptomatic EBV infection to PTLD, and sometimes develop into malignant lymphomas with high mortality. Successful transplantation of liver transplantation requires effective control of EBV infection. Previous studies have given evidence that molecular EBV monitoring is effective in finding patients with a high risk of developing PTLD. However, it has become also evident that molecular EBV monitoring alone is not sufficient to achieve complete prediction and hence prevention of PTLD [12]. Some researchers propose that monitoring of humoral immune parameters, including serum immunoglobulin concentrations and mono-/oligoclonal gammopathy, in combination with EBV monitoring, is valuable in identifying high-risk patients [13], 14].

EBV infection will bring a series of pathophysiological changes, such as activation of immune cells, secretion of cytokines, production of EBV-specific antibodies, and even tissue damage and inflammation. EBV initially attacks B lymphocytes, the viral envelope glycoprotein 350 (GP350) binds to the B lymphocyte membrane receptor CD21 for latent infection and then promotes EBV replication, which triggers CD3+ T lymphocytes’ defense response [15], 16]. Based on the antigen-dependent and cytokine-dependent manner, CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes differentiate into functional helper T cell subset, which plays a key role in initiating and strengthening immune response to promote humoral and innate immune response. Besides, it can regulate the biological activity of other immune cells in inflammation and infection. CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte is a cytotoxic subtype of T cell, which can directly destroy target cells or induce the apoptosis of target cells by secreting perforin interferon-gamma, as well as granzyme. Some studies have indicated that, in IM patients, CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes were highly activated, which could produce functional cytokines and help CD3+CD8+ T cells to recognize and kill EBV-infected cells [17], 18].

In the present study, the expression of lymphocyte markers was analyzed in pediatric liver transplant recipients with PTLD. The absolute number of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes in the PTLD-SD group was higher than that in the PTLD-PR group, whereas lower than that of IM children, which is in accordance with previous studies [19]. As can be seen from the two patterns of the trends between EBV-DNA loads and the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes, if the CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes increased beyond the normal range following the infection of EBV, the virus would be cleared in a few months. However, the depletion of CD8+ T cells results in increased viral load and persistent viremia in pediatric liver transplant recipients might reflect a weak EBV-specific immune response resulting from a poor induction of EBV-specific CD3+CD8+ lymphocytes when primary EBV infection is acquired during immunosuppressive therapy. Therefore, immunomodulation is more important than antivirus therapy in immunodeficiency patients [20].

The increase of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte numbers as well as the decrease in CD4/CD8 ratio was considered to reflect the recovery of T lymphocyte functions because these changes occurred in parallel with the decline in EBV-DNA loads. CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes are the most useful index in estimating the host capacity of immuno-surveillance against EBV because its increase was more prominent in those patients whose EBV-DNA loads decreased to an undetectable level than whose EBV-DNA loads retained high viral load.

Our limitation lies in the fact that test blood samples were obtained after the initiation of management. Prospective serial monitoring of PLS from the time of diagnosis through the course of management in a large cohort of children is necessary to confirm these observations. Despite this limitation, we believe that the results are important, this is the first observation between EBV-DNA loads and PLS in the long-term EBV viremia of children with different immunity. In conclusion, PLS, the easily available laboratory test, may be used as a potential surrogate measure of disease progression and treatment effects.

-

Research ethics: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Kedi Wang: writing – original draft, methodology, data curation, conceptualization. Dongjiang Xu: writing – review & editing, writing – original draft, supervision, project administration, formal analysis, conceptualization. Yan Gao: methodology, data curation. Kaihui Ma: writing – review & editing, validation. Wen Zhao: methodology, data curation.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Damania, B, Kenney, SC, Raab-Traub, N. Epstein-Barr virus: biology and clinical disease. Cell 2022;185:3652–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.08.026.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Fujiwara, S, Nakamura, H. Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection: is it immunodeficiency, malignancy, or both? Cancers 2020;12:3202. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12113202.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Tascini, G, Lanciotti, L, Sebastiani, L, Paglino, A, Esposito, S. Complex investigation of a pediatric haematological case: haemophagocytic syndrome associated with visceral leishmaniasis and Epstein-Barr (EBV) co-infection. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2018;15:2672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122672.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Liu, M, Wang, R, Xie, Z. T cell-mediated immunity during Epstein-Barr virus infections in children. Infect Genet Evol 2023;112:105443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2023.105443.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Subspecialty Group of Infectious Diseases, the Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association National Group of EpsteinBarr Virus Associated Diseases in Children. Principle suggestions for diagnosis and treatment of main nontumorous Epstein-Barr virus-associated diseases in children. Chin J Pediatrics 2016;54:563–8. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2016.08.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Dunmire, SK, Verghese, PS, Balfour, HHJr. Primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Clin Virol 2018;102:84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2018.03.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Hagn, M, Panikkar, A, Smith, C, Balfour, HHJr, Khanna, R, Voskoboinik, I, et al.. B cell-derived circulating granzyme B is a feature of acute infectious mononucleosis. Clin Transl Immunology 2015;4:e38. https://doi.org/10.1038/cti.2015.10.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Chen, J, Longnecker, R. Epithelial cell infection by Epstein-Barr virus. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2019;43:674–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuz023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Shi, BY, Zhang, YQ, Sun, LY. Clinical guidelines on Epstein-Barr virus infection in solid organ transplantation recipients and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (2019 edition). Organ Transplant 2019;10:149–57.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Infectious Diseases Group of the Pediatric Branch of the Chinese Medical Association and National Children’s EB Virus Infection Collaboration group. Experts consensus on diagnosis and treatment of Epstein-Barr virus infection-related diseases in children. Chin J Pediatr 2021;59:905–11.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Xie, ZD. Clinical features and diagnostic criteria of infectious mononucleosis associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection in children. J Appl Clin Pediatr 2007;22:1759–80.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Kimura, H, Kwong, YL. EBV viral loads in diagnosis, monitoring, and response assessment. Front Oncol 2019;12:62. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00062.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Davis, JE, Sherritt, MA, Bharadwaj, M, Morrison, LE, Elliott, SL, Kear, LM, et al.. Determining virological, serological and immunological parameters of EBV infection in the development of PTLD. Int Immunol 2004;16:983–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxh099.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Rosselet, A, Vu, DH, Meylan, P, Baur Chaubert, AS, Schapira, M, Pascual, M, et al.. Associations of serum EBV DNA and gammopathy with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. Clin Transplant 2009;23:74–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00904.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Peng, RJ, Han, BW, Cai, QQ, Zuo, XY, Xia, T, Chen, JR, et al.. Genomic and transcriptomic landscapes of Epstein-Barr virus in extranidal natural killer T-cell lymphoma. Leukemia 2019;33:1451–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-018-0324-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Li, W, He, C, Wu, J, Yang, D, Yi, W. Epstein-Barr virus encodes miRNAs to assist host immune escape. J Cancer 2020;11:2091–100. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.42498.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Hudnall, SD, Patel, J, Schwab, H, Martinez, J. Comparative immunophenotypic features of EBV-positive and EBV-negative atypical lymphocytosis. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2003;55:22–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/cyto.b.10043.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Long, HM, Chagoury, OL, Leese, AM, Ryan, GB, James, E, Morton, LT, et al.. MHC II tetramers visualize human CD4+ T cell responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection and demonstrate atypical kinetics of the nuclear antigen EBNA1 response. J Exp Med 2013;210:933–49. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20121437.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Chen, L, Chen, X, Yao, W, Wei, X, Jiang, Y, Guan, J, et al.. Dynamic distribution and clinical value of peripheral lymphocyte subsets in children with infectious mononucleosis. Indian J Pediatr 2021;88:113–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-020-03319-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Moss, DJ, Lutzky, VP. EBV – specific immune response: early research and personal reminiscences. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2015;390:23–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22822-8_3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- “Images from the Medical Laboratory” – editorial remarks

- Review

- Advances and challenges in platelet counting: evolving from traditional microscopy to modern flow cytometry

- Original Articles

- Comparison of two different technologies measuring the same analytes in view of the In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR)

- Assessing the stability of uncentrifuged serum and plasma analytes at various post-collection intervals

- Evaluation of different needle gauge blood collection sets (23G/25G) in aged patients

- The trend of Epstein-Barr virus DNA loads and CD8+ T lymphocyte numbers can predict the prognosis of pediatric liver transplant recipients with PTLD

- Preoperative serum glutathione reductase activity and alpha-fetoprotein level are associated with early postoperative recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Short Communication

- Comparison between detection power of MBT STAR-Carba test and KBM CIM Tris II for carbapenemase-producing bacteria

- Images from the Medical Laboratory

- Clarithromycin crystalluria

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- “Images from the Medical Laboratory” – editorial remarks

- Review

- Advances and challenges in platelet counting: evolving from traditional microscopy to modern flow cytometry

- Original Articles

- Comparison of two different technologies measuring the same analytes in view of the In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR)

- Assessing the stability of uncentrifuged serum and plasma analytes at various post-collection intervals

- Evaluation of different needle gauge blood collection sets (23G/25G) in aged patients

- The trend of Epstein-Barr virus DNA loads and CD8+ T lymphocyte numbers can predict the prognosis of pediatric liver transplant recipients with PTLD

- Preoperative serum glutathione reductase activity and alpha-fetoprotein level are associated with early postoperative recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Short Communication

- Comparison between detection power of MBT STAR-Carba test and KBM CIM Tris II for carbapenemase-producing bacteria

- Images from the Medical Laboratory

- Clarithromycin crystalluria