A new approach to the interpretation of B-type natriuretic peptide concentration in children with congenital heart disease

-

Andrei A. Svobodov

, Aleksei A. Kupryashov

Abstract

Objectives

BNP is the unique cardiac marker that reflects not as much as the degree of heart muscle damage, but mostly the severity of hemodynamic disorder, which is important in congenital heart disease. The only disadvantage of this marker is the barely studied reference values for children. It is known that the younger the child is, the higher the BNP value will be. By shifting from interpreting the absolute values towards the application of zlog-transformed data in clinical practice, we can overcome the above problems.

Methods

We performed an age-adjusted zlog transformation of BNP concentration. The age dependence was accounted for by a piecewise linear interpolation of the logarithms of BNP concentration among healthy children in different age groups from the logarithms of age.

Results

The concentration of BNP was measured in 351 patients (under 1 year old) with various heart diseases. The median age at the time of testing was 52 days [10; 166]; the median weight was 4.1 kg [3.2; 6.2]. The conditions we investigated included almost all known congenital heart diseases, as well as primary cardiac tumors. After the zlog transformation, we eliminated age-dependence, which was proved by comparing BNP concentrations in two groups of patients with univentricular and biventricular hemodynamics.

Conclusions

BNP in patients with congenital heart disease reflects the severity of hemodynamic disorders, and zlogBNP is an objective, age-independent and clear mechanism that can be used to interpret this cardiac marker.

Impact

This was the first time we proposed the zlog transformation of BNP level values, which is vital for the interpretation of this indicator in infants and newborns, characterized by age-dependent BNP concentrations. We have shown for the first time that in some congenital heart defects, zlogBNP can be negative, despite the increased absolute concentration, which indicates the absence of signs of heart failure.

By introducing our indicator into clinical practice, we will be able to re-evaluate the significance of BNP concentration in infants and newborns with CHD, and, thereby, improve the quality of care provided.

Introduction

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and its precursor NT-proBNP deserve a leading place among the markers of heart failure in general clinical practice. In addition to their diagnostic value, they allow to predict the life-expectancy and quality of life of patients, as well as to evaluate how effective the heart failure therapy is [1]. Both BNP and NT-proBNP markers demonstrate comparable diagnostic and prognostic value, and both are used for clinical and research purposes [2]. The markers differ mainly in the elimination rate. In addition, BNP concentration does not depend on renal dysfunction [3], which makes it more valuable in patients with critical conditions typical to the majority of newborns with congenital heart disease (CHD) [4].

The strong age-dependence of BNP concentration in children limits the use of the markers for similar purposes since they are characterized by broad reference ranges and significant variation at different periods of a patient’s life, especially during the first year. Such problems can be overcome by switching from interpreting absolute values in favor of using zlog-transformed data in clinical practice [5, 6]. In this case, the normal distribution is achieved by logarithmic transformation of absolute values, and standardization is done by presenting the data as the BNP concentration mean log deviation divided by the standard deviation of the logarithmically transformed values.

Previously, Palm J et al. similarly calculated the zlogNT-proBNP formula for healthy children and showed that this approach provided a more accessible interpretation of this marker of heart failure and allowed earlier and more accurate prediction of changes in the clinical condition of patients [6, 7]. In the present study, we attempted to bridge the gap in the pediatric interpretation of BNP concentration by calculating the zlogBNP function in healthy children and, thus, analyze data coming from one-year-old patients with congenital heart disease.

Materials and methods

Methods for calculating the zlogBNP function

Let us denote the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles as 10 % tile, 50 % tile, and 90 % tile. To construct the zlogBNP function, we used the BNP concentrations (50 % tile and 90 % tile) found in healthy children of different ages. The BNP concentrations were measured by applying the enzyme-enhanced chemiluminescence method using paramagnetic microparticles as a solid phase on an Access analyzer (Beckman Coulter, USA) and the TRIAGE BNP assay test systems [8].

Having the indicated measurement results, we can calculate the 10th percentile logarithm (log 10 % tile) at each age interval. The resulting BNP data set is known to have a log-normal distribution [9]. Thus, at each age interval, the logarithm of BNP concentration values has a normal distribution, and the mean and median are the same and equal to log 50 % tile (log 50 % tile is the median because the distribution functions of the original and logarithmic data are the same). The density function of the normal distribution is symmetric with respect to the median, so the value of log 10 % tile is calculated by the formula:

Based on the available measurements, 80 % prediction interval was chosen from LL=10 % tile to UL=90 % tile (LL is lower limit, UL is upper limit). The log-transformed data have a normal distribution, and the Z transformation (standardization) is performed using the formula:

where x is the value of BNP concentration, μ is the mean value, and σ is the standard deviation of the logarithmic BNP values.

After the Z transformation, the data have a standard normal distribution, so −1.28 and 1.28 are z-values corresponding to 10 and 90 % probabilities respectively. According formula (2) we get a system of equations:

where we express

We put the last two expressions into equation (2) and obtain:

The values of the

Formula (3) is correct within one age interval. In order to obtain a universal dependence of

We constructed the logarithm of BNP value as a piecewise linear function of the logarithm of age:

where x(t) is the BNP value at age t;

where

Such system of equations (6) and (7) has the unique solution:

j=1, … , n−1. We can easily find that

We can also rewrite formula (10) to be more compact:

Patient characteristics

A total of 351 patients with heart disease under 1 year old were examined. The median age was 52 days [10; 166]; the median weight was 4.1 kg [3.2; 6.2]. The conditions we examined included almost all known CHDs, as well as primary cardiac tumors. Twenty-four patients had previously undergone either the pulmonary artery banding or systemic to pulmonary artery shunt procedure. Signs of circulatory failure were noted in 197 (56 %) patients.

We divided 303 patients into subgroups depending on a CHD variant (ventricular septal defect (VSD), VSD after pulmonary artery banding, VSD combined with aortic coarctation, tetralogy of Fallot, tetralogy of Fallot after systemic to pulmonary artery shunt, common open atrioventricular canal, atrial septal defect (ASD), congenital aortic stenosis, patent ductus arteriosus, isolated pulmonary artery stenosis, aortic isthmus hypoplasia, main artery transposition, hypoplastic left-heart syndrome and aortic coarctation), each including at least 10 patients.

Laboratory tests

Venous blood sampling was performed in the morning on an empty stomach. BNP concentrations were measured by the microparticle chemiluminescence method using the Architect i1000sr immunoassay analyzer (Abbott, USA).

Statistics

The data analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 software. The dependences log 90 % tile and log 10 % tile on log (t) with regard to the number of patients were plotted using linear regression. Quantitative variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney test.

Results

zlogBNP function

The number of patients, their age, BNP concentration, and its 50 % tile and 90 % tile values used in the following analysis are given in Table 1.

Initial data for the number of patients, age and BNP concentration (based on Cantinotti et al. [8]).

| i | Age interval limits, h | Number of patients | BNP concentration, ng/L | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t min | t max | Min | Max | 50 % tile | 90 % tile | ||

| 1 | 1 | 24 | 57 | 41 | 837 | 224 | 521 |

| 2 | 25 | 48 | 49 | 53 | 866 | 242 | 457 |

| 3 | 49 | 96 | 50 | 23 | 862 | 152 | 315 |

| 4 | 97 | 192 | 32 | 10 | 739 | 45 | 224.4 |

| 5 | 193 | 720 | 34 | 9 | 63 | 27 | 55.2 |

| 6 | 721 | 8760 | 69 | 1 | 53 | 19 | 36 |

| 7 | 8761 | 105120 | 142 | 1 | 46 | 14.5 | 28.3 |

-

i is the number of the age interval.

The results of the log transformation (log 10 base) of the age and BNP concentration are presented in Table 2. The age logarithm mean values log (t) and the 10th percentile logarithm (log 10 % tile) were calculated by formulas (4) and (1), respectively.

Log transformation of age and BNP concentration.

| i | Log transformation of age | Log transformation of BNP concentration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log (tmin) | Log (tmax) | Log ( |

Log 10 % tile | Log 50 % tile | Log 90 % tile | |

| 1 | 0 | 1.380211 | 0.690106 | 1.983658313 | 2.350248 | 2.716837723 |

| 2 | 1.39794 | 1.681241 | 1.539591 | 2.107714532 | 2.383815 | 2.6599162 |

| 3 | 1.690196 | 1.982271 | 1.836234 | 1.865376622 | 2.181844 | 2.498310554 |

| 4 | 1.986772 | 2.283301 | 2.135036 | 0.955402175 | 1.653213 | 2.351022853 |

| 5 | 2.285557 | 2.857332 | 2.571445 | 1.120788451 | 1.431364 | 1.741939078 |

| 6 | 2.857935 | 3.942504 | 3.40022 | 1.001204701 | 1.278754 | 1.556302501 |

| 7 | 3.942554 | 5.021685 | 4.48212 | 0.870949569 | 1.161368 | 1.451786436 |

Using formulas (8)–formulas (9) and data from Table 2, we found the coefficients for the

Based on data from Table 3, we calculated the coefficients for the zlogBNP formula (11) (Table 4):

Coefficients for the zlogBNP formula (10).

| j |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.146037 | 1.882877 | −0.06701 | 2.76308 | 1 | 34.64105 |

| 2 | −0.81693 | 3.36546 | −0.54478 | 3.498657 | 34.64105 | 68.58577 |

| 3 | −3.04541 | 7.457461 | −0.49293 | 3.403441 | 68.58577 | 136.4696 |

| 4 | 0.378971 | 0.146286 | −1.39567 | 5.330833 | 136.4696 | 372.7735 |

| 5 | −0.14429 | 1.491822 | −0.22399 | 2.317915 | 372.7735 | 2513.159 |

| 6 | −0.12039 | 1.410574 | −0.0966 | 1.884778 | 2513.159 | 105120 |

-

j is the number of the age interval.

Coefficients for the zlogBNP formula (10).

| j | C |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.3229785 | 0.03951494 | 0.880202 | −0.21304 | 1 | 34.64105 |

| 2 | 3.4320583 | −0.6808581 | 0.133197 | 0.272153 | 34.64105 | 68.58577 |

| 3 | 5.4304509 | −1.7691685 | −4.05402 | 2.552482 | 68.58577 | 136.4696 |

| 4 | 2.7385592 | −0.5083505 | 5.184547 | −1.77464 | 136.4696 | 372.7735 |

| 5 | 1.9048682 | −0.1841394 | 0.826093 | −0.0797 | 372.7735 | 2513.159 |

| 6 | 1.6476757 | −0.1084995 | 0.474204 | 0.023791 | 2513.159 | 105120 |

Clinical use of the zlogBNP function

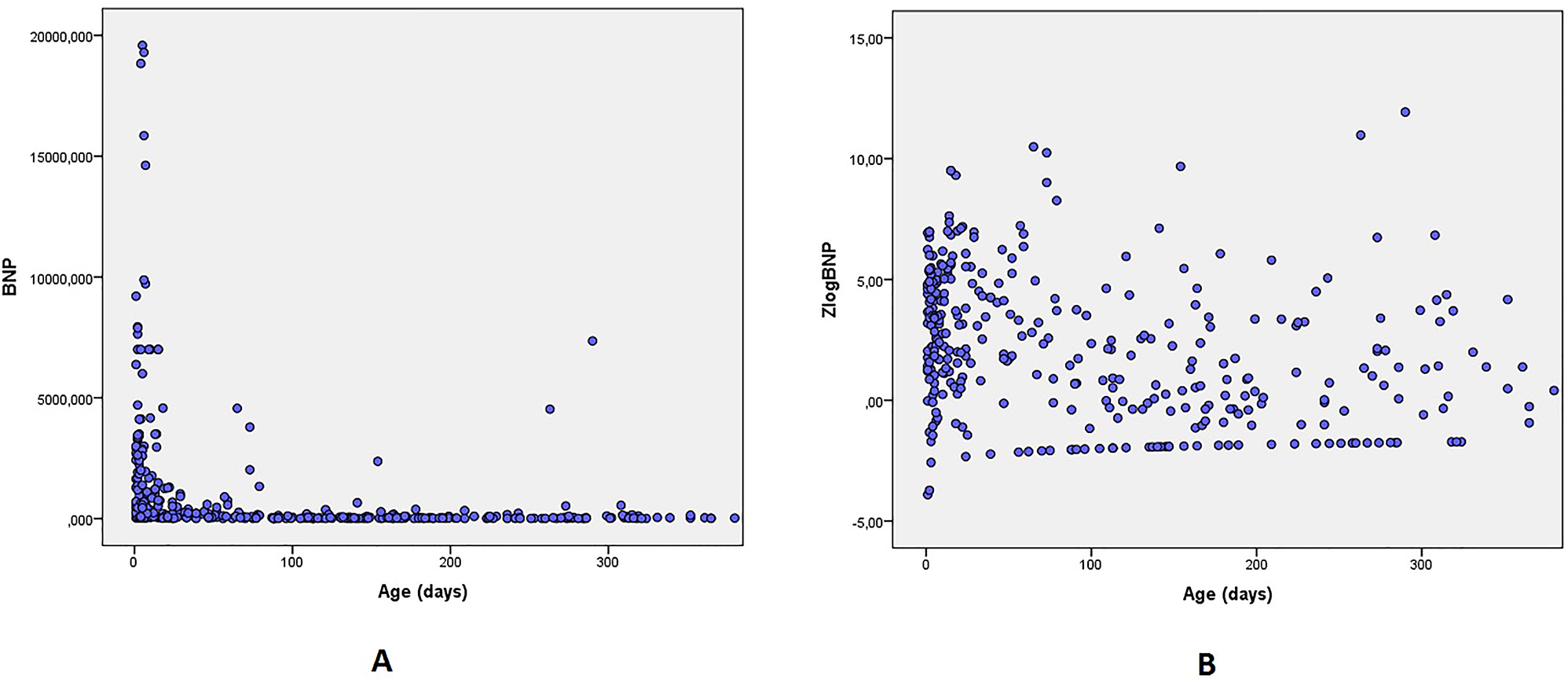

In the patient cohort we investigated, BNP concentration varied from 7 to 19,585 ng/L (arithmetic mean was 1,088 ng/L, mean square deviation was 2,657.34 ng/L, median was 90 ng/L, Q1 was 21.3 ng/L, Q3 was 700 ng/L, asymmetry ratio was 4.34, eccentricity ratio was 22.68), and the

Scatter graph of BNP concentration (A) and ZlogBNP (B) as a function of age.

BNP values were strongly dependent on the variant of congenital heart disease (Table 5).

BNP values in patients with various congenital heart diseases.

| Congenital heart disease | Number of observations | BNP concentration | zlogBNP |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Me, Q1; Q3] | [Me, Q1; Q3] | ||

| VSD | 70 | 137 [53; 664] | +2.9 [1.5; 4.7] |

| TOF | 33 | 29 [18; 67] | +0.2 [−0.6; 1.5] |

| TOF after BTS | 8 | 38 [17; 90] | +1.2 [−1.2.; 3.2] |

| VSD after PAB | 12 | 28 [13; 92] | +0.8 [−0.5; 2.8] |

| CoA | 45 | 1391 [55; 3474] | +3.7 [1.2; 5.2] |

| AVSD | 14 | 282 [70; 1,557] | +4.2 [2.0; 5.4] |

| ASD | 19 | 15 [7; 34] | −0.2 [−1.7; 1.3] |

| AS | 15 | 90 [24; 461] | +1.8 [0.4; 4.1] |

| PDA | 17 | 28 [12; 95] | +0.8 [−0.7; 3.0] |

| PS | 18 | 17 [10; 170] | −0.6 [−1.5; 1.6] |

| Aortic isthmus hypoplasia | 12 | 362 [47; 1502] | +2.3 [0.4; 5.1] |

| Double aortic arch | 10 | 7 [7; 21] | −1.8 [−2.0; −1.1] |

| TGA | 8 | 2527 [628; 6663] | +3.9 [1.8; 4.9] |

| HLHS | 15 | 2999 [950; 7000] | +4.7 [3.3; 6.9] |

-

VSD, ventricular septal defect; ToF, tetralogy of Fallot; TOF after BTS, tetralogy of Fallot after shunt operation; VSD after PAB, VSD after pulmonary artery banding; CoA, coarctation of the aorta; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; ASD, atrial septal defect; AS, aortic valve stenosis; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PS, pulmonary stenosis; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; HLHS, hypoplastic left-heart syndrome.

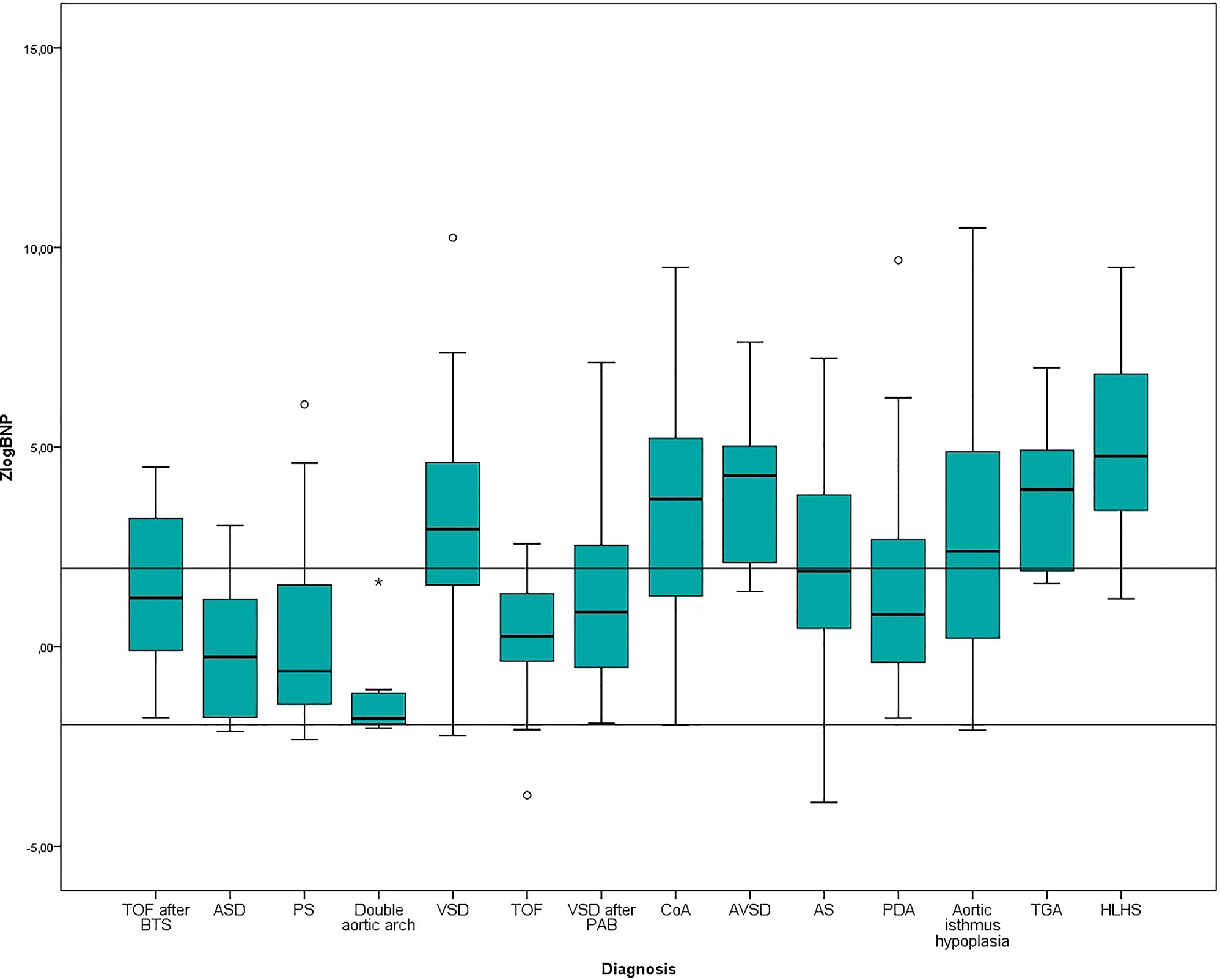

It should be noted that while some congenital diseases had predominantly high (more than 1.96) zlogBNP values (hypoplastic left heart syndrome, transposition of the great arteries), there were also CHDs with prevailing zlogBNP values less than −1.96 (atrial septal defect, isolated pulmonary artery stenosis, double aortic arch) (Figure 2). Separately, we should single out AS and moderate hypoplasia of the aortic isthmus, in which zlogBNP values are characterized by a significant interquartile range. This fact is due to hemodynamic heterogeneity of the indicated subgroups, since they included patients based on morphological features only.

Tukey graph of zlogBNP values in patients with different CHDs.

Of particular interest are the patients after pulmonary artery banding and tetralogy of Fallot after shunt operation. The former were characterized by lower zlogBNP values compared to the primary patients with VSD. In contrast, after systemic pulmonary anastomosis, the zlogBNP values were higher than in primary patients with tetralogy of Fallot.

When comparing BNP values in patients with uni-and biventricular hemodynamics (Table 6), we observed the standardization of values, expressed as the approximation of arithmetic mean to median, and significantly higher zlogBNP values in patients with univentricular hemodynamics.

Distribution of BNP and zlogBNP values depending on hemodynamic type.

| Number of patients | Median age, days | BNP | zlogBNP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | p-Value | Mean | Median | p-Value | |||

| Univentricular | 31 | 5 | 3764 | 1109 | 0.0001 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 0.0001 |

| Biventricular | 320 | 65 | 829 | 78 | 2.1 | 1.9 | ||

Discussion

The zlog transformation of absolute values of BNP concentration we performed served three purposes. First, it facilitated the standardization and approximation of values to the normal distribution. Second, we simplified the clinical interpretation of laboratory results, meaning that we did not try to interpret 3-4-digit numbers, but rather to estimate how distant a zlogBNP value from 0 was (the normal range is from −1.96 to +1.96) [5]. Third, we eliminated the age dependence of values we interpreted.

Natriuretic peptides in terms of clinical laboratory diagnostics are a unique kind of cardiac markers, reflecting not so much as the degree of organ or tissue damage or the severity of morphological changes, but mostly showing the degree of a hemodynamic compromise.

The key to the correct interpretation of NP values is to know the conditions of their synthesis and secretion. In the healthy heart of an adult, ANP and BNP are synthesized by atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes, which, thus, act as preload sensors. The preformed natriuretic peptides are found in mature secretory granules, and the ratio of ANP to BNP in them is fixed. NP secretion can be carried out exocytically by their mature secretory granules or by the constitutive pathway, which involves the de novo synthesis of natriuretic peptides and their incorporation into cisternae of the Golgi apparatus. In the healthy heart, the first pathway predominantly provides basal secretion, and the second ensures stimulated secretion. BNP is predominantly secreted through the constitutive pathway. Neurohormones (endothelin 1, angiotensin 2), mechanical distension of the atrial paries stimulate NP secretion, while cytokines also stimulate BNP secretion [10].

In the fetal heart, BNP synthesis reaches the maximum level during mid-pregnancy, followed by a decrease, but the level is still higher than in the heart of an adult [11]. After birth, the decrease in NP secretion occurs gradually against the background of changes in the ratio of cardiac contractile protein isoforms [12]. However, a high BNP concentration in neonates may also be a consequence of a higher preload due to a relatively larger circulating blood volume compared to adults.

The development of both global and local myocardial hypertrophy with fetalization of the cardiomyocyte phenotype is combined with the NP synthesis reprogramming [13]: there is an increase in BNP mRNA content in cardiomyocytes, its accumulation in secretory granules occurs, and the constitutive secretion pathway is supplemented by the exocytic one [10]. Considering a neonate with congenital heart disease, one should be aware that high BNP concentrations may be due to both the persistent fetal phenotype of cardiomyocytes, which can transform into the adult one quite quickly, and it’s reprogramming in case of an abnormality, as well as specific hemodynamic disturbances, inherent to a certain congenital heart disease. Increased preload with elevated myocardial tension suggests increased NP secretion. CHDs, characterized by low preload, low end-diastolic pressure, low tension of cardiac cavity parietes, will proceed with low NP concentration. These facts explain the low zlogBNP values in the subgroups with atrial septal defect and isolated pulmonary artery stenosis, as well as the differences in zlogBNP that existed between the subgroups with primary CHD and the same name CHD after salvage procedures. Thus, BNP concentration in early life is strongly dependent on both physiological and pathological factors, and it is vital for clinicians to identify the root cause of increased BNP concentration.

The zlog transformation of BNP concentration eliminates its age-dependence and allows to expand the possibilities of applying this marker in children. Such an example is our comparison of patients with uni-and biventricular hemodynamics. If we compared the absolute values of BNP concentration, we would not be confident that the results we would obtain would be reliable since the groups differed significantly in terms of age. However, by analyzing age-independent zlogBNP, we could reliably say that patients with univentricular hemodynamics had a higher level of BNP secretion.

By improving this research, we can also solve more specific tasks. In the recent study, researchers measured NT-proBNP concentration in children after the Norwood procedure and proved that there were changes due to the shunt type. It was proved that the Sano modification of the operation led to a greater prevalence of right ventricular dysfunction and higher NT-proBNP values [14].

Different test systems for determining BNP concentration have a highly variable degree of consistency of the results. Calculating the zlogBNP formula for each of the existing test systems requires the accumulation of sufficient samples from healthy children of all ages, which seems difficult to achieve, including for ethical reasons. The presented zlog transformation model calculated on the basis of the results obtained with the TRIAGE BNP assay test system showed satisfactory results with the ARCHITECT BNP Assay test system. The formula we proposed may have limited application when determining the limits and evaluating the results obtained with other tests systems and may require adjustments. However, this formula is viable when comparing the values of different patients or following up on them if they are examined using the same test system.

Zlog transformation of absolute BNP values in this paper was based on the available data [8]. Direct use of BNP 10 % tile and 90 % tile as upper and lower limits of age intervals in zlog formula may lead to considerable jumps of zlog values from one age group to the next [15]. In our research age dependence of zlog values was achieved via interpolation of UL and LL values from each age interval. More accurate age-dependent limits may be calculated by the methods with higher resolution [16].

Conclusions

Thus, the synthesis and secretion of BNP in patients with congenital heart disease primarily reflects the nature and severity of hemodynamic abnormalities, and zlogBNP is an objective (age-independent primarily) and clear mechanism allowing to interpret this cardiac marker. In addition, we believe that further study of zlogBNP has the potential to profoundly

Funding source: Russian Science Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 21-71-30023

-

Research funding: The results presented in Section 2.1 were performed at the Marchuk Institute of Numerical Mathematics of the Russian Academy of Sciences with the support of the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 21-71-30023).

-

Author contributions: AS conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. AS, AK are wrote the main manuscript text. TD provide mathematical and statistical calculations. EL prepared data base. MT, AA carried out the selection of patients. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The investigation was approved by the Ethical committee of “A. N. Bakulev National Medical Research Center of Cardiovascular Surgery” of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Protocol No. 3 of July 7, 2021). The research was carried out following the Declaration of Helsinki.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Yancy, CW, Jessup, M, Bozkurt, B, Butler, J, Casey, DE, Drazner, MH, et al.. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:e147–239, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Weber, M. Role of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and NT-proBNP in clinical routine. Heart 2005;92:843–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.071233.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Rørth, R, Jhund, PS, Yilmaz, MB, Kristensen, SL, Welsh, P, Desai, AS, et al.. Comparison of bnp and nt-probnp in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Circ Hear Fail 2020;13:e006541. https://doi.org/10.1161/circheartfailure.119.006541.Search in Google Scholar

4. Nourbakhsh, N, Benador, N. Assessment of fluid status in neonatal dialysis: the need for new tools. Pediatr Nephrol 2023;38:1373–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-022-05829-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Hoffmann, G, Klawonn, F, Lichtinghagen, R, Orth, M. The zlog value as a basis for the standardization of laboratory results. J Lab Med 2018;42:63–5. https://doi.org/10.1515/labmed-2017-0135.Search in Google Scholar

6. Palm, J, Hoffmann, G, Klawonn, F, Tutarel, O, Palm, H, Holdenrieder, S, et al.. Continuous, complete and comparable NT-proBNP reference ranges in healthy children. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020;58:1509–16. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2019-1185.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Palm, J, Holdenrieder, S, Hoffmann, G, Hörer, J, Shi, R, Klawonn, F, et al.. Predicting major adverse cardiovascular events in children with age-adjusted NT-proBNP. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78:1890–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.08.056.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Cantinotti, M, Law, Y, Vittorini, S, Crocetti, M, Marco, M, Murzi, B, et al.. The potential and limitations of plasma BNP measurement in the diagnosis, prognosis, and management of children with heart failure due to congenital cardiac disease: an update. Heart Fail Rev 2014;19:727–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-014-9422-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Cantinotti, M, Storti, S, Parri, MS, Murzi, M, Clerico, A. Reference values for plasma B-type natriuretic peptide in the first days of life. Clin Chem 2009;55:1438–40. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2009.126847.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Goetze, JP, Bruneau, BG, Ramos, HR, Ogawa, T, de Bold, MK, de Bold, AJ. Cardiac natriuretic peptides. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;17:698–717. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-0381-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Sergeeva, IA, Christoffels, VM. Regulation of expression of atrial and brain natriuretic peptide, biomarkers for heart development and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2013;1832:2403–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Nakagawa, Y, Nishikimi, T, Kuwahara, K. Atrial and brain natriuretic peptides: hormones secreted from the heart. Peptides 2019;111:18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2018.05.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Pol, A, Hoes, MF, Boer, RA, Meer, P. Cardiac foetal reprogramming: a tool to exploit novel treatment targets for the failing heart. J Intern Med 2020;288:491–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13094.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Piber, N, Ono, M, Palm, J, Kido, T, Burri, M, Röhlig, C, et al.. Influence of shunt type on survival and right heart function after the Norwood procedure for aortic atresia. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;34:1300–10. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semtcvs.2021.11.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Klawitter, S, Hoffmann, G, Holdenrieder, S, Kacprowski, T, Klawonn, F. A zlog-based algorithm and tool for plausibility checks of reference intervals. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023;61:260–5. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2022-0688.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Zierk, J, Baum, H, Bertram, A, Boeker, M, Buchwald, A, Cario, H, et al.. High-resolution pediatric reference intervals for 15 biochemical analytes described using fractional polynomials. Clin Chem Lab Med 2021;59:1267–78. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2020-1371.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Diagnostic accuracy of stool sample-based PCR in detecting Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis

- Original Articles

- Assessment of antibody titer and side effects after fourth doses of COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in 38 healthy volunteers

- The predictive value of the C-reactive protein/albumin ratio in adult patients with complicated appendicitis

- A novel multimodal approach for the assessment of phlebotomy performance in nurses

- A new approach to the interpretation of B-type natriuretic peptide concentration in children with congenital heart disease

- Bilirubin is a superior biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and for differential diagnosis of benign liver disease

- Congress Abstracts

- German Congress of Laboratory Medicine: 18th Annual Congress of the DGKL and 5th Symposium of the Biomedical Analytics of the DVTA e. V.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Diagnostic accuracy of stool sample-based PCR in detecting Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis

- Original Articles

- Assessment of antibody titer and side effects after fourth doses of COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in 38 healthy volunteers

- The predictive value of the C-reactive protein/albumin ratio in adult patients with complicated appendicitis

- A novel multimodal approach for the assessment of phlebotomy performance in nurses

- A new approach to the interpretation of B-type natriuretic peptide concentration in children with congenital heart disease

- Bilirubin is a superior biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and for differential diagnosis of benign liver disease

- Congress Abstracts

- German Congress of Laboratory Medicine: 18th Annual Congress of the DGKL and 5th Symposium of the Biomedical Analytics of the DVTA e. V.