Abstract

Background

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) are one of the most common infections seen in all age groups and in all locations. The current knowledge on the patterns of bacterial profile, and its antibiotic resistance are essential to design and implement appropriate interventions. This study was conducted to assess the prevalence and multi-drug resistance pattern of bacterial isolates among septicemia and/or bacteremia suspected cases in Ethiopia.

Methods

Searching was conducted in databases of PubMed, Research Gate, Scopus and Google Scholar. In addition, manual searching is also conducted in bibliographies of included studies and in other meta-analysis studies. Required data were extracted from articles published up to 2020 on the bacterial profile of septicemia in Ethiopia, and analyzed using comprehensive meta-analysis version 3.3.0 software.

Results

A total of 5,823 septicemia suspected cases were extracted from 18 included studies and the overall blood culture positive rate of 31.9% (95% CI: 0.261–0.382). Of these, the overall Gram positive and Gram negative isolates was 57.8% (95% CI: 0.534–0.584) and 42.2% (95% CI: 0.416–0.466), respectively. Among Gram positives, predominantly reported isolates was Staphylococcus aureus (47.9%: 480 of 1,003), followed by Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus (42.7%: 428 of 1,003), whereas among Gram negatives, the most frequently reported isolates was Klebsiella species (29.8%: 218 of 731), followed by Escherichia coli (23.1%: 169 of 731). Significant levels of resistance was reported against ampicillin, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, co-trimoxazole and tetracycline with a pooled resistance range of 40.6–55.3% in Gram positive and 52.8–85.7% in Gram negative isolates. The pooled estimates of multi-drugs resistance (MDR) was (66.8%) among Gram positives and (80.5%) among Gram negatives, with the overall MDR rate of (74.2%).

Conclusions

The reported blood culture positive rates among septicemia cases were relatively high. Second, the level of drug and multi-drug resistant isolates against commonly prescribed antibiotics was significant. However, the scarcity of data on culture confirmed septicemia cases as well as patterns of antimicrobial resistance may overshadow the problem.

Background

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) can be sepsis and/or bacteremia and are one of the most common infectious diseases seen in all age groups, and in all locations, with the greatest burden in low-income countries [1]. These infections can be caused by bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic infections, and can be mimicked by non-infectious etiologies, making diagnosis particularly challenging where an infectious source is not immediately apparent [1], [2].

The epidemiology of bloodstream infections is different across the world: globally, an estimated of 48.9 million incident cases of septicemia and 11.0 million sepsis-related deaths (representing 19·7% of all global deaths) were reported, in 2017 [2]. Among all age groups, both sexes, and all locations, the most common underlying cause of sepsis was diarrhoeal diseases, with 9.21 million cases of sepsis attributable to diarrhoeal diseases [2]. Studies in Africa suggest that prevalence of bacterial infections among inpatients is greater than that described in wealthier regions [3], [4], [5].

Although, early treatment with appropriate antimicrobials has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in cases of bacterial infection, the threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is growing at an alarming rate and the situation is perhaps aggravated in developing countries due to gross abuse in the use of antimicrobials [6], [7]. In addition, the emergency of multi-drug resistance among Gram-negative bacteria is a major concern, given the scarcity of diagnostic microbiology laboratories and difficulty in accessing effective antibiotic therapy for resistant pathogens [8]. For instance, the estimated prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa is between 60 and 90% [8], highlighting the growing challenge of treating bloodstream infections in these countries. The increasing use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and lack of good stewardship have contributed to the increasing of these multi-drugs resistance (MDR) organisms that contribute for poor treatment outcome [9], [10].

The diagnostic test that is most often associated with bacterial sepsis is the blood culture [11]. However, in areas without advanced laboratory test, especially in our situation, many infections are treated empirically without microbiological investigation of the etiologic agents. Due to these, the current knowledge on the patterns of bacterial isolates, its antibiotic resistance profile, and associated factors was limited, although it is essential in designing and implementations of appropriate interventions. Therefore, this finding has several key implications for health policy makers, clinicians, and researchers to update infection-prevention measures and to implement in areas with the highest incidence of septicemia and/or bacteremia and among populations on which septicemia will have the greatest impact.

Methods

Study design

A meta-analysis study consisting of different studies on bacterial profile and antimicrobial resistance pattern among of septicemia and/or bacteremia suspected cases of all age group was conducted in Ethiopia. While conducting this meta-analysis, the authors tried to follow Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram and checklist (http://www.prisma-statement.org/) [12] during the screening of titles and abstracts as well as evaluation of full-texts for eligibility and final inclusion.

Study selections and search strategies

Search was carried out in the database of PubMed, Research Gate, Scopus and Google Scholar. “Bacterial profile”, OR “septicemia”, OR “bacteremia AND antimicrobial resistance”, “bloodstream infection” OR “antimicrobial resistance” OR “Sepsis” OR “antimicrobial resistance” AND “Ethiopia” were used as search strategies. In addition, relevant studies were manually searched from bibliographies of eligible studies and from other meta-analysis studies. All studies conducted in Ethiopia and that available online up to April, 2020, and studies focusing on the bacterial profile with their antimicrobial resistance pattern among septicemia and/or bacteremia suspected cases in all age groups and studies contain sufficient outcome variables were considered as appropriate for eligibility assessment.

Screening and eligibility criteria

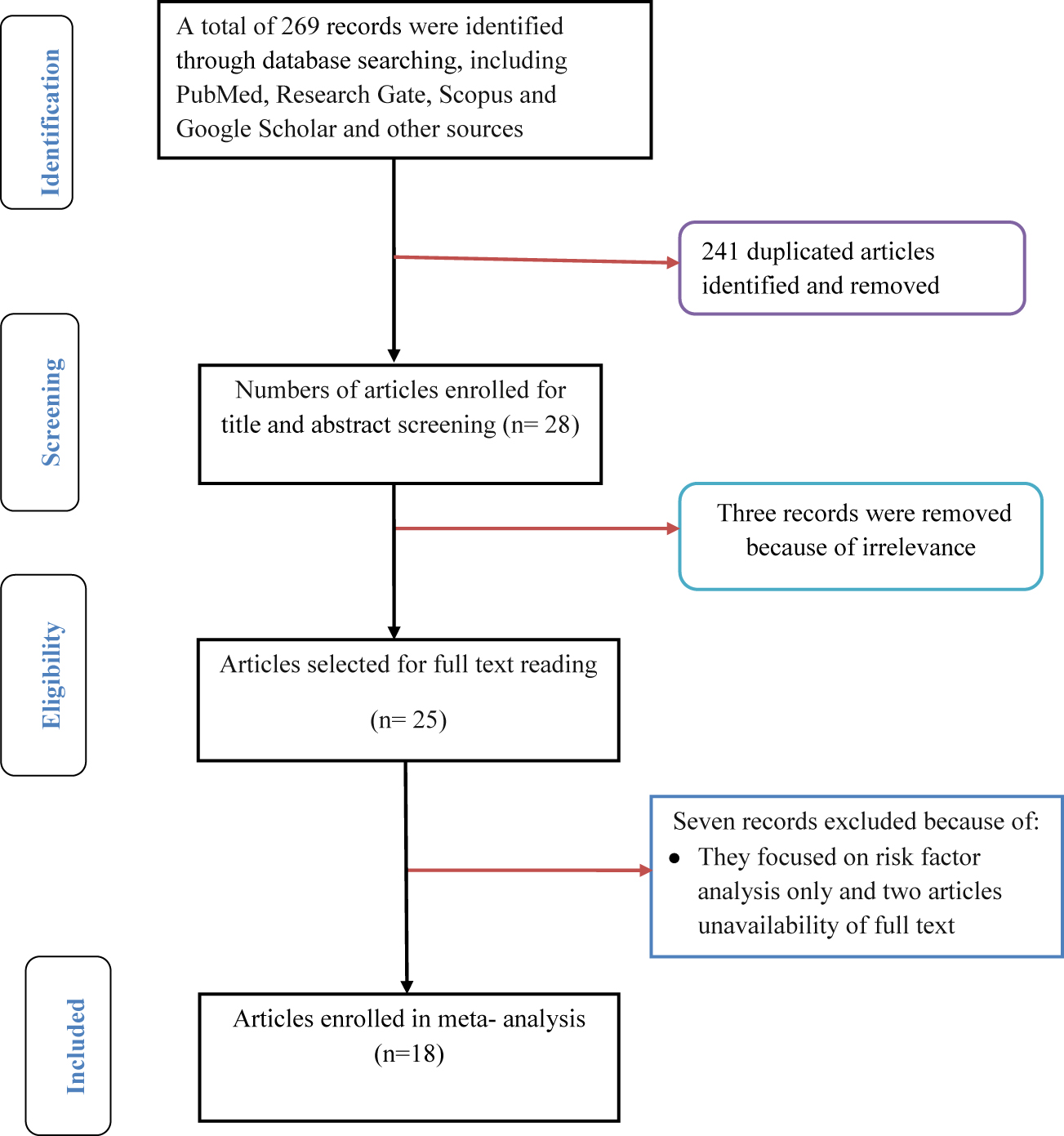

All studies conducted outside Ethiopia and those with unrelated outcomes of interest were excluded. First duplicated records were removed and then two authors (MA and SH) were independently inspected all the titles and abstracts of articles related to the study question and those irrelevant articles were excluded. Articles passed the first step were further screened in a second step by reviewing the full-texts and evaluated the eligibility of them for final inclusion (Figure 1). The third author (MA*) adjudicated disagreement arose between the first two reviewers.

Flow chart depicting the selection process of included articles.

Data extraction

Two authors (MA and SH) were independently extracted important outcome variables from each included studies. Data related to first author, study area, region of the study, study periods, year of publication, study design, sample size, target population, and outcome of interests, such as number of patients who had blood cultures sampled, the number who had positive cultures for a bacterial pathogen, number and gram reactions and common species of bacterial pathogen, and proportion and/or number of drug and multi-drug resistant isolates were recorded. Data extractions were made at least twice to remove any discordance and pre-determined and piloted forms were used as data extraction tools.

Outcome variables

The first outcome variable is the blood culture positive rates of bacteremia suspected cases in Ethiopia. The pooled blood culture positive rate was calculated per sample size (number of patients who had blood cultures sampled). The second outcome variable is antimicrobial resistance profiles and multi-drug resistance patterns of the common bacterial isolates against selected antimicrobials of different categories.

Quality assessment of included studies

Items included in strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) Statement-checklist [13], were used to check the quality of included studies. The quality scores for each study were calculated against items of the STROBE checklist adequately. There were no limits with regard to study type except that the study had to be an original study. In addition, we didn’t exclude any studies based on quality.

Data processing and analysis

A meta-analysis was done to calculate the culture positive rate of septicemia and/or bacteremia suspected cases, the proportional representation of Grams positive and Grams negative pathogen and the pooled estimates of drug and multi-drug resistance isolates using comprehensive meta-analysis version 3.3.0 software (www.Meta-analysis.com). A random-effect meta-analysis model was used to assess the outcome variables and variability of included studies and significant variation was considered at p-values <0.05 and I2>50%. A Begg’s and Egger’s test was performed to assess publication bias and statistical significant evidence was considered at p-value <0.05.

Results

Search results and selection process of included articles

Two hundred sixty nine (269) studies regarding septicemia in all age group were identified from PubMed, Research Gate, Scopus, Google Scholar and other sources. Among these, 28 articles were enrolled for abstract and title screen. After full text assessment of 25 articles, 18 articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included for meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Characteristics of included studies

All included studies (18) were hospital-based cross-sectional study design and published in the year from 2008 to 2020. All studies utilized blood specimens for detection of bacterial causes of sepsis, and were conducted among inpatient and/or outpatients as their sources of samples. Half of 9 (50.0%) [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22] the included articles were conducted in the Amhara region of Ethiopia, 3 (16.7%) [23], [24], [25] in Oromia region, 5 (27.8%) [27], [28], [29], [30], [31] were in central Ethiopia (Addis Ababa) and only 1 (5.6%) [31] study conducted in Tigray region of Ethiopia. With regard to study population, 9 (50%) [15, 17–21, 25, 30, 31] of included studies included all age groups as their study subjects, 6 (33.3%) [14, 16, 23, 24, 27, 28] focused on neonates, each of 1 (5.6%) study was focused on post-partum/aborted women [22], 1 day–12 years [26] and age group of ≥18 years [29]. The highest and the lowest proportion of culture positive sepsis cases were reported from central Ethiopia, with respective proportions of 71.0% [29] and 13.0% [30] (Table 1). The median score of studies against STROBE items was 67.2% with a range of 41.5–79.4.

Characteristics of studies included in meta-analysis of the culture positive rates of sepsis cases in Ethiopian.

| Study region | Study area | Study period | Study design | Publication year | Study population | Sample size | Culture positives cases, n (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amhara | Gondar | September 2015 to May 2016 | Cross-sectional | 2017 | 0–28 days | 251 | 117 (46.6%) | G/eyesus et al. [14] |

| Gondar | September 2006 to January 2012 | Cross-sectional | 2013 | All age groups | 390 | 71 (18.2%) | Dagnew et al. [15] | |

| Gondar | July 2011 to June 2012 | Cross-sectional | 2012 | 1–28 days | 181 | 58 (32.1%) | Gebrehiwot et al. [16] | |

| Gondar | March to May 2013 | Retrospective cross-sectional | 2018 | All age groups | 856 | 169 (19.7%) | Abebaw et al. [17] | |

| Bahir Dar | March 2013 to January 2015 | Cross-sectional | 2016 | All age groups | 561 | 220 (39.2%) | Hailu et al. [18] | |

| Gondar | March to May 2013 | Cross-sectional | 2016 | HIV patients | 100 | 31 (31%) | Alebachew et al. [19] | |

| Gondar | March 2001 to April 2005 | Cross-sectional | 2008 | All age groups | 472 | 114 (24.2%) | Ali and Kebede [20] | |

| Gondar | February to April 2017 | Cross-sectional | 2018 | All age groups | 216 | 42 (19.4) | Fentie et al. [21] | |

| Bahir Dar | January to May 2017 | Cross-sectional | 2020 | Post-partum/Aborted women | 166 | 56 (33.7%) | Admas et al. [22] | |

| Oromia | Asella | April 2016 to May 2017 | Cross-sectional | 2019 | 0–28 days | 303 | 88 (29.4%) | Sorsa et al. [23] |

| Jimma | April to October 2018 | Cross-sectional | 2020 | 0–28 days | 238 | 135 (56.7%) | Gashaw et al. [24] | |

| Jimma | March to June 2013 | Cross-sectional | 2016 | All age groups | 95 | 15 (15.8%) | Kumalo et al. [25] | |

| Central Ethiopia | Addis Ababa | October 2011 to February 2012 | Cross-sectional | 2015 | 1 day–12 years | 201 | 56 (27.9%) | Negussie et al. [26] |

| Addis Ababa | October 2006 and March 2007 | Cross-sectional | 2010 | 0–28 days | 302 | 135 (44.7%) | Shitaye et al. [27] | |

| Addis Ababa | 2007–2008 | Cross-sectional | – | 0–28 days | 578 | 166 (28.7%) | Yusuf and Worku [28] | |

| Addis Ababa | December 2011 to June 2012 | Cross-sectional | 2018 | ≥18 years | 107 | 76 (71.0%) | Arega et al. [29] | |

| Addis Ababa | August 2012 to October 2013 | Cross-sectional | 2015 | All age groups | 292 | 38 (13.0%) | Seboxa et al. [30] | |

| Tigray | Mekelle | March to October 2014 | Cross-sectional | 2015 | All age groups | 514 | 144 (28.0%) | Wasihun et al. [31] |

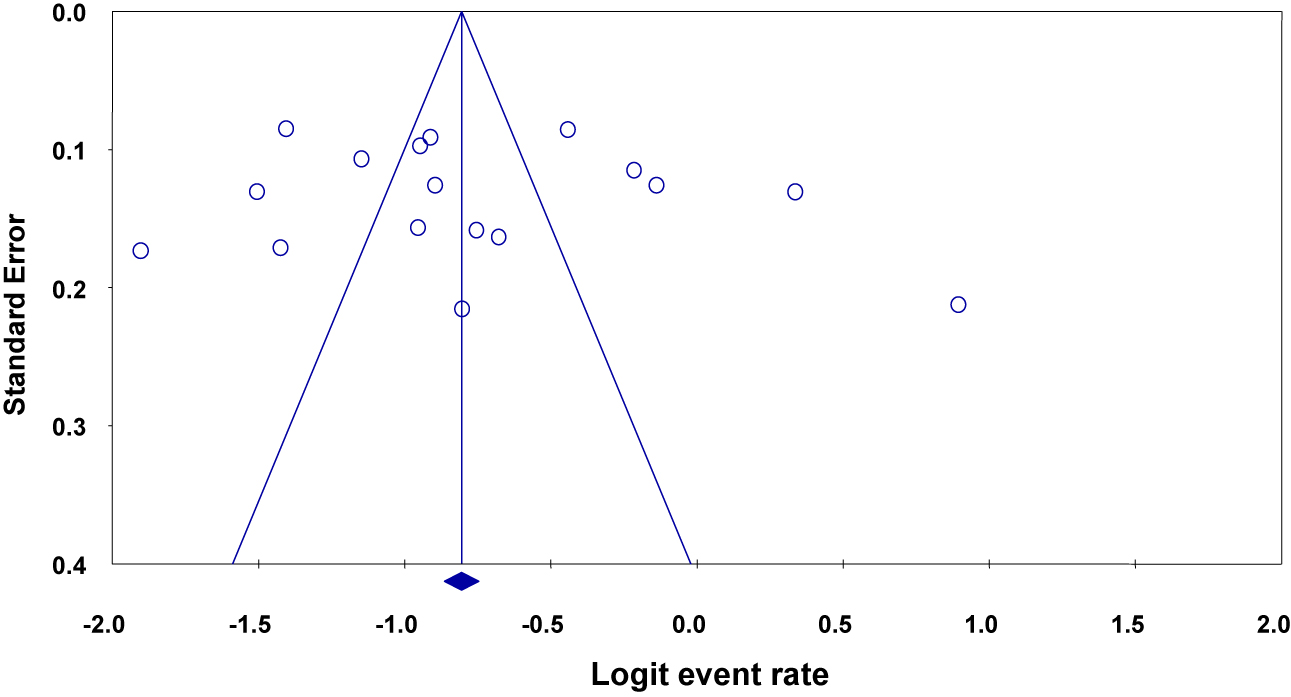

Publication bias

Non-significant effect of publication bias was observed among included studies with a Begg’s and Egger’s p-value >0.05 (Figure 3). But, Begg’s suggested that a non-significant correlation may be due to low statistical power, and cannot be taken as evidence that bias is absent.

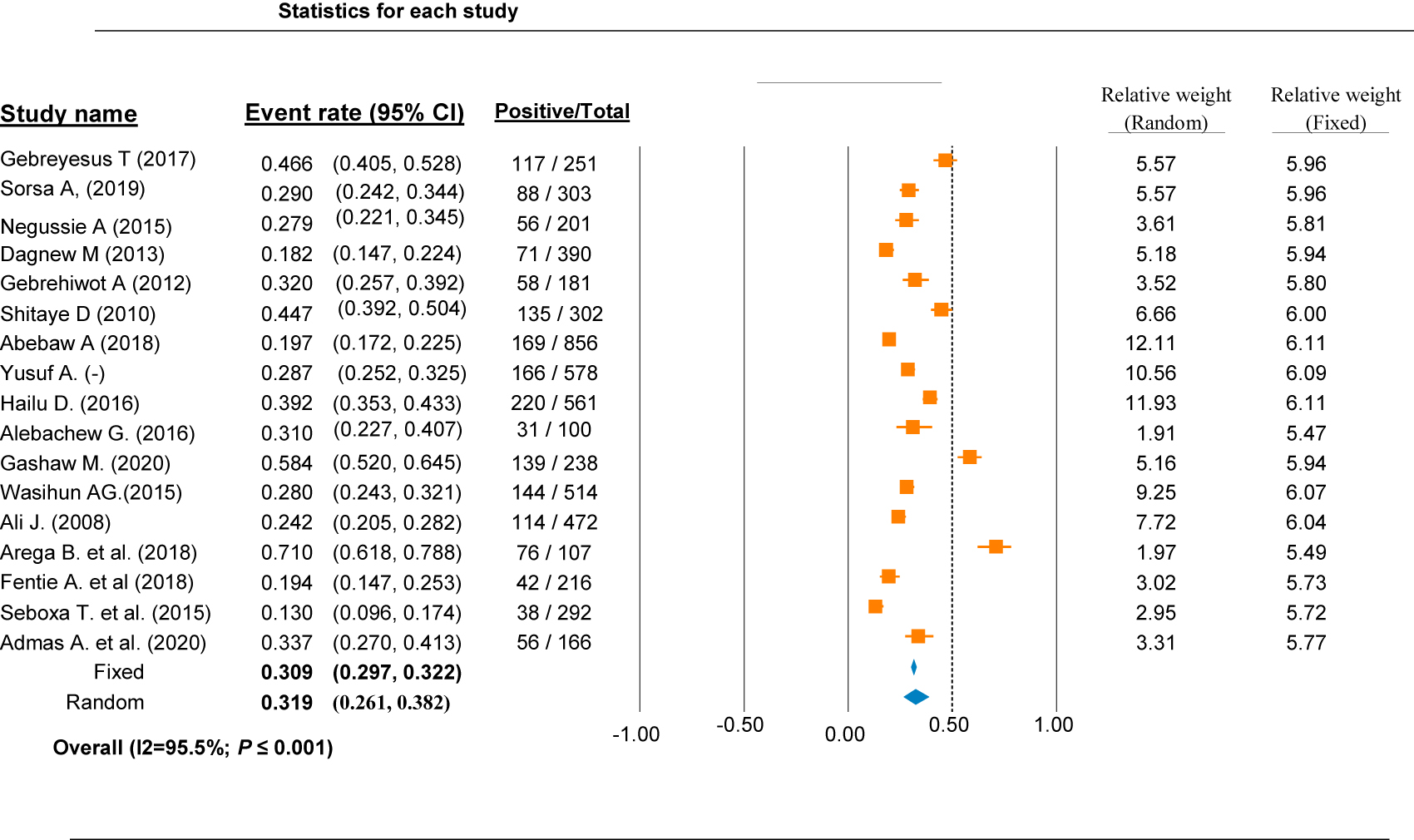

Culture positive rates of septicemia cases in Ethiopia

This study, the overall estimated culture positive bacteremia and/or sepsis case was 31.9% with a confidence interval of (95% CI: 0.261, 0.382). The pooled proportions of culture positive bacteremia and/or sepsis cases was estimated by using a random and fixed effect model and overall significant heterogeneity was observed between the studies (I2=95.5%; p-value ≤0.001) (Figure 2). The variation in the study setups, study periods, and study populations, could have an effect on the severity of heterogeneity among the included studies.

Overall blood culture positive rate of septicemia cases in different region of Ethiopia.

Funnel plot depicting publication bias of studies reporting the bacterial profiles causing septicemia and/or bacteremia in different parts of Ethiopia.

Bacterial profiles causing bacteremia in Ethiopia

In this study, from a total of 5,823 patients suspected of bacteremia, 1,734 were confirmed to be positive for blood culture. Of these, the overall reported Gram positive and Gram negative isolates was 57.8% (95% CI: 0.534, 0.584) and 42.2% (95% CI: 0.416, 0.466), respectively (p-value=1.000). Among Gram positives, the most predominant reported isolates was Staphylococcus aureus (47.9%: 480 of 1,003 Gram positives), followed by Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus (42.7%: 428 of 1,003 Gram positives). Among Gram negatives, the most frequently reported isolates was Klebsiella species with a rate of 29.8% (218 of 731 Gram negatives), followed by Escherichia coli with the proportion of 23.1% (169 of 731 Grams negatives) (Table 2).

Summary of studies included regarding the most common isolated bacterial species causing sepsis in Ethiopian.

| First authors [references] | Total # of isolates | Commonly detected species of bacteria | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram positives | Gram negatives | ||

| G/eyesus et al. [14] | 120 | 81 (67.5%) CoNs = 26, S. aureus = 49, S. pyogenes = 6 |

39 (32.5%) K. pneumoniae = 19, E. coli = 12, Serratia = 1, E. cloacae = 4 and K. rhinose = 3 |

| Dagnew et al. [15] | 71 | 49 (69%) CoNs = 30, S. aureus = 17, Other = 2 |

22 (31%) Klebsiella spps = 9, E. coli = 5, Others = 8 |

| Gebrehiwot et al. [16] | 58 | 22 (37.9%) CoNs = 4, S. aureus = 17, Other = 1 |

36 (62.1%) Klebsiella spps = 16, E. coli = 6, Others = 12 |

| Abebaw et al. [17] | 174 | 112 (64.4%) CoNs = 55, S. aureus = 48, S. pyogenes = 6, Other = 3 |

62 (35.6%) Klebsiella spps = 11, E. coli = 15, Citrobacter spp. = 8, Others = 28 |

| Hailu et al. [18] | 220 | 105 (47.7%) CoNs = 35, S. aureus = 50, E. faecalis = 6, Other = 14 |

115 (52.3%) K. pneumoniae = 35, E. coli = 19, P. aeruginosa = 15, Proteus spps = 6, Others = 40 |

| Alebachew et al. [19] | 31 | 26 (83.9%) CoNs = 8, S. aureus = 13, Other = 5 |

5 (16.1%) K. ozaenae = 1, E. coli = 1, Others = 3 |

| Ali and Kebede [20] | 114 | 80 (70.2%) CoNs = 38, S. aureus = 34, Other = 6 |

34 (29.8%) Klebsiella spps = 10, E. coli = 2, Others = 19 |

| Fentie et al. [21] | 43 | 25 (58.1%) CoNs = 11, S. aureus = 12, Other = 2 |

18 (41.9%) Klebsiella spps = 2, E. coli = 9, Others = 7 |

| Admas et al. [22] | 56 | 23 (41.1%) CoNs = 4, S. aureus = 19, Other = 0 |

33 (58.9%) Klebsiella spps = 7, E. coli = 18, Others = 8 |

| Sorsa et al. [23] | 88 | 49 (55.7%) CoNs = 22, S. aureus = 16, Enterococcus spps = 6, S. pneumoniae, L. monocytogenes and Candida = 5 |

39 (44.3%) Klebsiella spps = 11, E. coli = 18, Enterobacter spps = 6, Citrobacter spp = 4 |

| Gashaw et al. [24] | 135 bacteria & eight fungi | 70 (51.8%) CoNs = 36, S. aureus = 27, Other = 7 |

65 (48.2%) Klebsiella spps = 21, E. coli = 5, Others = 39 |

| Kumalo et al. [25] | 15 | 8 (53.3%) CoNs = 2, S. aureus = 6, Other = 0 |

7 (46.7%) Klebsiella spps = 1, E. coli = 1, Others = 5 |

| Negussie et al. [26] | 55 bacteria + one fungi | 26 (46.4%) CoNs = 11, S. aureus = 13, Other = 2 |

29 (51.8%) Klebsiella spps = 9, E. coli = 1, Serratia marcescens = 12, Others = 7 |

| Shitaye et al. [27] | 135 | 59 (43.7%) CoNs = 10, S. aureus = 30, Other = 19 |

76 (56.3%) Klebsiella spps = 50, E. coli = 10, Others = 16 |

| Yusuf and Worku [28] | 166 | 104 (62.7%) CoNs = 69, S. aureus = 37, Other = 9 |

62 (37.3%) Klebsiella spps = 11, E. coli = 15, Others = 36 |

| Arega et al. [29] | 71 bacteria + 11 fungi | 43 (60.5%) CoNs = 12, S. aureus = 31, Other = 0 |

28 (39.5%) Klebsiella spps = 3, E. coli = 1, Others = 24 |

| Seboxa et al. [30] | 38 | 18 (47.4%) CoNs = 11, S. aureus = 7, Other = 0 |

20 (52.6%) Klebsiella spps = 1, E. coli = 15, Others = 2 |

| Wasihun et al. [31] | 144 | 103 (71.5%) CoNs = 44, S. aureus = 54, Other = 5 |

41 (28.5%) Klebsiella spps = 1, E. coli = 16, Others = 25 |

| Total, n (%; 95% CI) | 1,734 | 1,003 (57.8%; 0.534, 0.584) | 731 (42.2%; 0.416, 0.466) |

-

CoNs, Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus; CI, confidence interval; Other: Pseudomonas spps, Serratia spps, Enterobacter spps, Citrobacter spps, Acinetobacter spps, Streptococci spps, Enterococcus spps, Listeria spps, Salmonella spps and fungi.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of bacterial isolates

In this study, antimicrobial resistance profiles of the extracted Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria were analyzed against few selected antibiotics and have been presented in Table 3. Accordingly, among Gram positive and Gram negative isolates, high resistant rates were observed against ampicillin (55.3%; 95% CI: 0.455, 0.646) and (85.7%; 95% CI: 0.801, 0.900) and amoxicillin (40.6%; 95% CI: 0.348, 0.488) and (57.4%; 95% CI: 0.493, 0.651), respectively. The pooled proportion of resistance against ceftriaxone was 43.3% (95% CI: 0.338, 0.533) and 52.8% (95% CI: 0.408, 0.645), respectively. Resistance rate of Gram positive and Gram negative isolates against co-trimoxazole was 52.6% (95% CI: 0.403, 0.646) and 60.3% (95% CI: 0.515, 0.864) and against tetracycline was 49.1% (95% CI: 0.311, 0.675) and 69.5% (95% CI: 0.529, 0.822), respectively. Both Gram positive and Gram negative isolates recorded with lower levels of resistance against ciprofloxacillin 23.8% (95% CI: 0.185, 0.299) and 22.4% (95% CI: 0.166, 0.296) and gentamycin 32.4% (95% CI: 0.229, 0.436) and 44.2% (0.314, 0.579), respectively.

Pooled antibiotic resistance rates of bacteria causing septicemia in Ethiopia.

| First authors [references] | Gram reactions of isolates | Antibiotic resistance profiles, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | AMX | CRO | CN | CIP | SXT | TE | ||

| G/eyesus et al. [14] | GP=81 | 30/81 (37.0) | – | 22/81 (27.2%) | 28/81 (34.6) | 16/81 (19.8) | 34/81 (42.0) | 28/81 (34.6) |

| GN=39 | 33/39 (84.6) | 11/39 (28.2) | 22/39 (56.4%) | 5/39 (17.2) | 5/39 (12.8) | 17/39 (43.6) | 10/39 (25.6) | |

| Sorsa et al. [23] | GP=49 | 33/49 (67.4) | – | 29/49 (59.2%) | 27/49 (55.1) | 13/49 (26.5) | 31/49 (63.3) | – |

| GN=39 | 28/39 (71.8) | – | – | 27/39 (69.2) | 11/39 (28.2) | 24/39 (61.5) | – | |

| Negussie et al. [26] | GP=26 | 24/26 (92.3) | – | 10/26 (38.5) | 9/26 (34.6) | 6/26 (23.1) | 17/26 (65.4) | 14/26 (53.8) |

| GN=29 | 29/29 (100) | – | 19/29 (65.5) | 26/29 (89.7) | 4/29 (13.8) | 25/29 (86.2) | 23/29 (79.3) | |

| Dagnew et al. [15] | GP=49 | 20/49 (40.8) | 13/49 (26.5) | 17/47 (36.2) | 14/47 (29.9) | 12/47 (25.5) | 26/47 (55.3) | 28/47 (59.6) |

| GN=22 | 17/22 (77.3) | 10/22 (45.5) | 10/22 (45.4) | 7/22 (31.8) | 6/22 (27.3) | 11/22 (50.0) | 13/22 (59.1) | |

| Gebrehiwot et al. [16] | GP=22 | 17/22 (77.3) | 6/22 (27.3) | 16/22 (72.7) | – | 11/22 (50.0) | 18/21 (85.1) | 19/21 (90.5) |

| GN=36 | 35/36 (97.2) | 1/36 (2.8) | 21/36 (58.3) | – | 14/34 (41.2) | 12/17 (70.6) | 22/33 (66.7) | |

| Shitaye et al. [27] | GP=59 | 22/59 (37.3) | 16/59 (27.1) | 10/59 (16.9) | 12/59 (20.3) | 0 | 6/59 (10.2) | – |

| GN=76 | 70/70 (100) | 53/70 (75.7) | 65/70 (92.9) | 65/70 (92.9) | 2/70 (2.9) | 34/70 (48.6) | – | |

| Abebaw et al. [17] | GP=112 | 71/112 (63.4) | 64/112 (57.1) | 44/109 (40.4) | 49/112 (43.8) | 36/111 (32.4) | – | – |

| GN=62 | 56/62 (90.3) | 55/62 (88.7) | 19/61 (31.2) | 33/58 (56.9) | 18/58 (31.0) | 38/61 (62.3) | 46/62 (74.2) | |

| Yusuf and Worku [28] | GP=105 | 83/105 (79.1) | – | 48/105 (45.7) | 71/105 (67.6) | 25/105 (23.8) | 68/105 (64.8) | – |

| GN=61 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Hailu et al. [18] | GP=105 | 46/85 (54.1) | – | – | 1/6 (16.7) | 13/90 (14.4) | 23/88 (26.1) | 6/86 (7.0) |

| GN=115 | 95/115 (82.6) | – | 68/100 (68.0) | 60/115 (52.2) | 24/115 (20.9) | 66/100 (66.0) | – | |

| Alebachew et al. [19] | GP=26 | 17/26 (65.4) | 0 | 0 | 3/26 (11.5) | 1/26 (3.8) | 17/26 (65.4) | 8/26 (30.8) |

| GN=5 | 5/5 (100) | 4/5 (80.0) | 1/5 (20.0) | 1/5 (20.0) | 0 | 5/5 (100) | 4/5 (80.0) | |

| Gashaw et al. [24] | GP=70 | – | – | 50/70 (71.4) | – | – | 60/70 (85.7) | 54/70 (77.1) |

| GN=65 | 65/65 (100) | 65/65 (100) | 54/65 (83.1) | 35/65 (53.8) | 26/65 (40.0) | 47/65 (72.3) | 56/65 (85.2) | |

| Wasihun et al. [31] | GP=103 | – | 13/103 (12.6) | 54/103 (52.4) | 26/103 (25.4) | 34/103 (33.0) | 77/103 (74.8) | – |

| GN=41 | – | 4/41 (7.8) | 21/41 (51.2) | 8/41 (19.5) | 3/41 (7.3) | 12/41 (29.3) | – | |

| Arega et al. [29] | GP=43 | 16/43 (37.2) | 27/43 (62.8) | 29/43 (67.4) | – | – | 13/43 (30.3) | 19/43 (44.2) |

| GN=28 | 18/24 (75.0) | 20/24 (83.3) | 11/24 (45.8) | 5/24 (20.8) | 3/24 (12.5) | 19/24 (79.2) | 11/24 (45.8) | |

| Fentie et al. [21] | GP=25 | – | – | – | 5/25 (20.0) | 7/25 (28.0) | 10/25 (40.0) | 5/25 (20.0) |

| GN=18 | 15/18 (83.3) | 14/18 (77.8) | 4/18 (22.2) | 5/18 (27.8) | 5/18 (27.8) | – | – | |

| Seboxa et al. [30] | GP=18 | – | 0 | 1/7 (14.9) | 0 | 0 | 3/7 (42.9) | – |

| GN=20 | – | 7/20 (35.0) | 9/20 (57.1) | 9/20 (45.0) | 8/20 (40.0) | 13/20 (65.0) | – | |

| Admas et al. [22] | GP=23 | 12/23 (52.2) | – | 4/23 (17.4) | – | 3/23 (13.0) | 8/23 (34.8) | 23/23 (100) |

| GN=33 | 33/33 (100) | 18/33 (54.6) | 16/33 (48.5) | 7/33 (21.2) | 8/33 (24.2) | 16/33 (48.5) | 31/33 (93.9) | |

| Kumalo et al. [25] | GP=8 | 6/8 (75.0) | 2/8 (25.0) | 1/8 (12.5) | 0 | 1/8 (12.5) | 0 | 5/8 (62.5) |

| GN=7 | 6/7 (85.7) | 1/7 (14.9) | 4/7 (57.1) | 2/7 (28.6) | 1/7 (14.9) | 4/7 (57.1) | 5/7 (71.4) | |

| Pooled resistance rate, % (95% CI) | GP | 55.3 (0.455, 0.646) | 40.6 (0.348, 0.488) | 43.3 (0.338, 0.533) | 32.4 (0.229, 0.436) | 23.8 (0.185, 0.299) | 52.6 (0.403, 0.646) | 49.1 (0.311, 0.675) |

| GN | 85.7 (0.801, 0.900) | 57.4 (0.493, 0.651) | 52.8 (0.408, 0.645) | 44.2 (0.314, 0.579) | 22.4 (0.166, 0.296) | 60.3 (0.515, 0.864) | 69.5 (0.529, 0.822) | |

| Combined resistance rate, % (95% CI) | 73.0 (0.657, 0.792) | 47.5 (0.428, 0.523) | 47.9 (0.401, 0.559) | 39.9 (0.314, 0.490) | – | 57.7 (0.499, 0.652) | 55.2 (0.380, 0.712) | |

-

NB, not analyzed; GP, Gram positives; GN, Gram negatives; AMP, ampicillin; AMX, ampicillin; CRO, ceftriaxone; CN, gentamycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; SXT, trimethoprim–sulphamethoxazole; TE, tetracycline; CI, confidence interval.

Multi-drugs resistance (MDR) profiles of bacterial isolates

In this study, the pooled proportional estimates of MDR Gram positive isolates was found to be 66.8% (95% CI: 0.556, 0.759), whereas among Gram negative isolates MDR was found to be 80.5% (95% CI: 0.672, 0.888). The overall MDR rate was 74.2% (95% CI: 0.640, 0.823) (Table 4).

Pooled multi-drug resistance (MDR) rates of bacteria causing septicemia in Ethiopia.

| First authors [references] | Total MDR | Gram reaction of isolates | # of MDR | Pooled MDR rate, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G/eyesus et al. [14] | 78/120 (65%) | Gram positives (n=81) | 56/81 | 69.1 (0.583, 0.782) |

| Gram negatives (n=39) | 22/39 | 56.4 (0.709, 0.425) | ||

| Sorsa et al. [23] | 63/88 (72%) | Gram positives (n=49) | 32/49 | 65.3 (0.511, 0.772) |

| Gram negatives (n=39) | 31/39 | 79.5 (0.640, 0.894) | ||

| Negussie et al. [26] | 51/55 (92.7%) | Gram positives (n=26) | 25/26 | 96.2 (0.772, 0.955) |

| Gram negatives (n=29) | 26/29 | 89.7 (0.724, 0.964) | ||

| Gebrehiwot et al. [16] | 52/58 (85.7%) | Gram positives (n=22) | 19/22 | 86.4 (0.652, 0.955) |

| Gram negatives (n=36) | 33/36 | 91.7 (0.771, 0.973) | ||

| Shitaye et al. [27] | 91/135 (67.4%) | Gram positives (n=59) | 27/59 | 45.8 (0.336, 0.585) |

| Gram negatives (n=76) | 64/76 | 84.2 (0.742, 0.908) | ||

| Abebaw et al. [17] | 151/174 (86.9%) | Gram positives (n=112) | 94/112 | 83.9 (0.759, 0.896) |

| Gram negatives (n=62) | 57/62 | 91.9 (0.820, 0.966) | ||

| Alebachew et al. [19] | 25/31 (80.6%) | Gram positives (n=26) | 21/26 | 80.8 (0.613, 0.918) |

| Gram negatives (n=5) | 4/5 | 80.0 (0.309, 0.973) | ||

| Gashaw et al. [24] | 114/135 (84.4%) | Gram positives (n=70) | 51/70 | 72.9 (0.613, 0.820) |

| Gram negatives (n=65) | 63/65 | 96.9 (0.885, 0.992) | ||

| Wasihun et al. [31] | 85/144 (59.0%) | Gram positives (n=103) | 64/103 | 62.1 (0.524, 0.710) |

| Gram negatives (n=41) | 21/41 | 51.2 (0.363, 0.660) | ||

| Arega et al. [29] | 19/71 (26.9%) | Gram positives (n=43) | 13/43 | 30.2 (0.184, 0.454) |

| Gram negatives (n=28) | 6/16 | 37.5 (0.179, 0.623) | ||

| Fentie et al. [21] | 20/43 (46.5%) | Gram positives (n=25) | 10/25 | 40.0 (0.230, 0.597) |

| Gram negatives (n=18) | 10/18 | 55.0 (0.330, 0.760) | ||

| Admas et al. [22] | 47/56 (83.9%) | Gram positives (n=23) | 14/23 | 60.9 (0.402, 0.782) |

| Gram negatives (n=33) | 33/33 | 98.5 (0.804, 0.999) | ||

| Kumalo et al. [25] | 12/15 (80.0%) | Gram positives (n=8) | 7/8 | 87.5 (0.312, 0.764) |

| Gram negatives (n=7) | 5/7 | 71.4 (0.321, 0.542) | ||

| Total MDR rate % [95% CI] | Gram positives (n=647) | 433 | 66.90 (0.556, 0.759) | |

| Gram negatives (n=478) | 375 | 80.50 (0.672, 0.888) | ||

|

|

||||

| Combined MDR rate % [95% CI] | GP ‘plus’ GN=1,125 | 808 | 74.20 (0.640, 0.823) | |

-

GP, Gram positives; GN, Gram negatives; MDR, multi-drug resistance; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Bacterial profile of septicemia is constantly changing thus, current knowledge on the patterns of bacterial isolates, its antibiotic resistance profile, and associated factors, are essential to design and implement appropriate interventions. It is the first a meta-analysis study conducted to determine pooled prevalence of blood culture positive rate of septicemia and/or bacteremia suspected cases and bacterial profiles with their antimicrobial resistance in Ethiopia. Accordingly, in this meta-analysis, the overall estimated rate of positive blood culture was (31.9%), which is in agreement with other finding in developing countries [32], [33], [34]. However, this finding is relatively higher [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], and lower [40], [41], [42] than a study findings from low- and middle-income countries.

Although, laboratory confirmed blood culture remains the best approach and the gold standard measure to identify microorganisms when a bloodstream infection is suspected, to guarantee that the antimicrobial treatment is adequate [43], [44], the limited number of studies in African regions, including Ethiopia with laboratory confirmed cases would underestimate the prevalence of sepsis in this meta-analysis. Rapid microbiological investigations of the causative agent with their antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) are very important to adjust the anti-infectious therapy and to avoid inefficient treatment, to reduce the spectrum of the anti-infectious therapy so as to limit the selection of resistant strains [11]. However, the population screened for bloodstream infections often may not have bacterial infection, and those that do may not be detectable with blood cultures. This is because of unavailability and sensitivity and specificity of blood culture is overall low, partly because it depends on the blood volume drawn, the timing of the blood draw, any prior treatment with antibiotics, and the presence of viable organisms [45], [46].

In this meta-analysis, the overall prevalence for Grams positive and Grams negative isolates was 57.8 and 42.2%, respectively. The higher prevalence of Gram negative than Grams positive isolates was reported in low- and middle-income and developed countries [38, 43, 47, 48]. In contrast, higher prevalence of Gram positive than Grams negative isolates was reported in Egypt and China [42], [49]. In this study, the most predominant reported Gram positives and Gram negatives isolates was S. aureus (47.9%), CoNs (42.7%), Klebsiella spps (29.8%) and E. coli (23.1%). The predominance of the above isolates as common causes of septicemia was also reported in many previous studies [34, 38, 49]. Another large systematic review on causative pathogens of community-acquired sepsis in low- and middle-income countries demonstrated that, the most prevalent bacterial pathogens for neonatal sepsis as S. aureus, E. coli, and Klebsiella species [50], [51].

With regard to AMR, in this study, the pooled proportion of MDR Grams positive isolates was (66.8%), whereas Grams negative isolates was (80.5%) with the overall MDR rate of (74.2%). The higher rate of MDR isolates among Grams negatives might be related to frequencies of infections caused by Grams-negative bacteria which leads them for frequent exposure to antimicrobial agents, which again helps them for selective pressure. In addition, significant resistance rates was observed against ampicillin, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, co-trimoxazole and tetracycline with a pooled resistance ranges of (40.6–55.3%) in Grams positive and (52.8–85.7%) in Gram negative isolates. In contrast, slightly lower levels of resistance were observed against ciprofloxacillin and gentamycin with a pooled resistance ranges of (23.8–32.4%) in Gram positive and (22.4–44.2%) in Gram negatives, respectively. The high levels of resistance rate against the above antibiotics were also reported from many countries [38, 42, 47, 49, 52].

The root causes of the spread of antibiotic resistance are multi-factorials and interconnected. In the fact that, microorganisms have their own natural mechanisms for the development of resistance, however, many possible human related factors may contribute for highly aggravated and continuous deployment of resistance [53], [54]. Some of these factors may include inappropriate prescription practices, inadequate patient education, limited diagnostic facilities, unauthorized sale of antimicrobials, lack of appropriate functioning drug regulatory mechanisms, and non-human use of antimicrobials such as in animal production are the main drivers of AMR in both humans and animals, combined by a low level of compliance of the patients [53], [54], [55].

Ecological studies have demonstrated almost linear relationships between antibiotic consumption and the prevalence of AMR [55], [56]. Broad-spectrum antibiotics increase the selective pressure of bacteria and stimulate the emergence of multi-drug resistant pathogens. A Survey study in Mongolia showed that, 42.3% of caregivers had used non prescribed antibiotics to treat symptoms in their child during the previous six months [57]. A systematic review and meta-analysis across 38 studies from 24 countries from eastern European and central Asian found that the pooled proportion of non-prescription supply of antibiotics was 62% [58]. Especially it is a common practice in developing countries, where the prevalence of infectious disease burden is aggravated by uncontrolled access to antibiotics. In those countries, antibiotics are prescribed to 44–97% of patients in hospital, and are often unnecessary [59], [60], [61], [62], [63].

In addition, although many countries have been endorsed clinical guidelines or treatment protocols for some common infections in hospitals, only 30% of health workers suggested that were generally accepted and followed that guidelines “all of the time” and 54% accepted and followed “sometimes” and around 15% used rarely [64]. This will lead to the increase of microbial resistance, an undesirable effect that causes antibiotic ineffectiveness and not only harmful to the patient but also to the society [63], [64]. With the new and emergent issue regarding the development of AMR, government agencies have engaged in new action plans in order to combat the AMR issue. However, actions toward this have been severely lacking in developing countries especially those in Africa where high quality regulatory agencies are lacking.

The current study had some limitations. First, although we have performed a comprehensive literature search, data from several provinces were limited, therefore the same estimates cannot be guaranteed from further studies that include these regions in the future. Second, we could not perform a detailed sub-group analysis other than what was presented in the manuscript, because the majority of studies included in the meta-analysis did not classify the neonatal sepsis cases based on type of delivery, birth weight and community-onset/hospital-associated infections.

Conclusions

Like other developing countries, the problems related to bloodstream infection that caused by microorganisms, including multi-drug resistance bacteria was significant in Ethiopia. The limited availability of data on culture confirmed bloodstream infections and underlying risk factors, and patterns of antimicrobial resistance may overshadow the problem. In addition, most etiological data was from hospital-based studies and may have little relevance to community-acquired infections. Therefore, improving the knowledge of pathogens causing bloodstream infections with their antimicrobial resistance pattern is essential for devising management strategies.

-

Research funding: No funding was allocated for this study.

-

Author contributions: MA, SH and MA* participated in the study design and gathered data. MA analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors support data analysis, read, revised and approved the final version manuscript.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Availability of data and materials: All the data supporting our findings were incorporated within the manuscript, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

References

1. Singer, M, Deutschman, CS, Seymour, CW, Shankar-Hari, M, Annane, D, Bauer, M, et al.. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). J Am Med Assoc 2016;315:801–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0287.Search in Google Scholar

2. Rudd, KE, Johnson, SC, Agesa, KM, Shackelford, KA, Tsoi, D, Kievlan, DR, et al.. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020;395:200–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32989-7.Search in Google Scholar

3. Bahwere, P, Levy, J, Hennart, P, Donnen, P, Lomoyo, W, Dramaix-Wilmet, M, et al.. Community-acquired bacteremia among hospitalized children in rural Central Africa. Int J Infect Dis 2001;5:180–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1201-9712(01)90067-0.Search in Google Scholar

4. Kuppermann, N Occult bacteremia in young febrile children. Pediatr Clin 1999;46:1073–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70176-0.Search in Google Scholar

5. Haddon, RA, Barnett, PL, Grimwood, K, Hogg, GG. Bacteraemia in febrile children presenting to a pediatric emergency department. Med J Aust 1999;170:475–8. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb127847.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Byarugaba, DK. A view on antimicrobial resistance in developing countries and responsible risk factors. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2004;24:105–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.02.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Ayukekbong, JA, Ntemgwa, M, Atabe, AN. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies. Antimicrob Resist Infect Contr 2017;6:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-017-0208-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Le Doare, K, Bielicki, J, Heath, PT, Sharland, M. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance rates among Gram-negative bacteria in children with sepsis in resource-limited countries. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc 2015;4:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piu014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Brierley, J, Carcillo, JA, Choong, K, Cornell, T, Decaen, A, Deymann, A, et al.. Clinical practice parameters for hemodynamic support of pediatric and neonatal septic shock: 2007 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 2009;37:666–88. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819323c6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Kunz, AN, Brook, I. Emerging resistant Gram-negative aerobic bacilli in hospital-acquired infections. Chemotherapy 2010;56:492–500. https://doi.org/10.1159/000321018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Coburn, B, Morris, AM, Tomlinson, G, Detsky, AS. Does this adult patient with suspected bacteremia require blood cultures? J Am Med Assoc 2012;308:502–11. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.8262.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, Altman, DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Malta, M, Cardoso, LO, Bastos, FI, Magnanini, MM, Silva, CM. STROBE initiative: guidelines on reporting observational studies. Saude Publica 2010;44:559–65. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89102010000300021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. G/eyesus, T, Moges, F, Eshetie, S, Yeshitela, B, Abate, E. Bacterial etiologic agents causing neonatal sepsis and associated risk factors in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr 2017;17:137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0892-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Dagnew, M, Yismaw, G, Gizachew, M, Gadisa, A, Abebe, T, Tadesse, T, et al.. Bacterial profile and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern in septicemia suspected patients attending Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:283. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-283.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Gebrehiwot, A, Lakew, W, Moges, F, Anagaw, B, Yismaw, G, Unakal, C. Bacterial profile and drug susceptibility pattern of neonatal sepsis in Gondar University hospital, Gondar Northwest Ethiopia. Der Pharm Lett 2012;4:1811–6.Search in Google Scholar

17. Abebaw, A, Tesera, H, Belachew, T, Mihiretie, GD. The bacterial profile and antibiotic susceptibility pattern among patients with suspected bloodstream infections, Gondar, north-west Ethiopia. Pathol Lab Med Int 2018;10:1–7.10.2147/PLMI.S153444Search in Google Scholar

18. Hailu, D, Abera, B, Yitayew, G, Mekonnen, D, Derbie, A. Bacterial blood stream infections and antibiogram among febrile patients at Bahir Dar Regional Health Research Laboratory Center, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Sci Technol 2016;9:103-12. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejst.v9i2.3.Search in Google Scholar

19. Alebachew, G, Teka, B, Endris, M, Shiferaw, Y, Tessema, B. Etiologic agents of bacterial sepsis and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns among patients living with human immunodeficiency virus at Gondar University teaching hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BioMed Res Int 2016;2016:5371875. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5371875.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Ali, J, Kebede, Y. Frequency of isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates from blood culture, Gondar University teaching hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 2008;46:155–61.Search in Google Scholar

21. Fentie, A, Wondimeneh, Y, Balcha, A, Amsalu, A, Adankie, BT. Bacterial profile, antibiotic resistance pattern and associated factors among cancer patients at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist 2018;11:2169–78. https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.s183283.Search in Google Scholar

22. Admas, A, Gelaw, B, Tessema, B, Worku, A, Melese, A. Proportion of bacterial isolates, their antimicrobial susceptibility profile and factors associated with puerperal sepsis among post-partum/aborted women at a referral hospital in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Contr 2020;9:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0676-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Sorsa, A, Früh, J, Loraine, S, Abdissa, S. Blood culture result profile and antimicrobial resistance pattern: a report from neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), Asella teaching and referral hospital, Asella, south East Ethiopia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Contr 2019;8:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0486-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Gashaw, M, Ali, S, Tesfaw, G, Eshetu, B, Workneh, N, Berhane, M, et al.. Bacterial profile and drug resistance patterns in neonates admitted with sepsis to a tertiary teaching hospital in Ethiopia 2020. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.19534/v1 [under review].Search in Google Scholar

25. Kumalo, A, Kassa, T, S/Mariam, Z, Daka, D, Tadesse, AH. Bacterial profile of adult sepsis and their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern at Jimma University specialized hospital, south West Ethiopia. Health Sci J 2016;10:3.Search in Google Scholar

26. Negussie, A, Mulugeta, G, Bedru, A, Ali, I, Shimeles, D, Lema, T, et al.. Bacteriological profile and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of blood culture isolates among septicemia suspected children in selected hospitals Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Biol Med Res 2015;6:4709–17.Search in Google Scholar

27. Shitaye, D, Asrat, D, Woldeamanuel, Y, Worku, B. Risk factors and etiology of neonatal sepsis in Tikur Anbessa university hospital, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 2010;48:11–21.Search in Google Scholar

28. Yusuf, A, Worku, B. Descriptive cross-sectional study on neonatal sepsis in the neonatal intensive care unit of Tekur Anbessa Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Pediatr Child Health 2010;6:175–82.Search in Google Scholar

29. Balew Arega, B, Woldeamanuel, Y, Adane, K, Sherif, AA, Asrat, D. Microbial spectrum and drug-resistance profile of isolates causing bloodstream infections in febrile cancer patients at a referral hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist 2018;11:1511–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.s168867.Search in Google Scholar

30. Seboxa, T, Amogne, W, Abebe, W, Tsegaye, T, Azazh, A, Hailu, W, et al.. High mortality from blood stream infection in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, is due to antimicrobial resistance. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144944.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Wasihun, AG, Wlekidan, LN, Gebremariam, SA, Dejene, TA, Welderufael, AL, Haile, TD, et al.. Bacteriological profile and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of blood culture isolates among febrile patients in Mekelle Hospital, Northern Ethiopia. SpringerPlus 2015;4:314. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1056-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Almohammady, MN, Eltahlawy, EM, Reda, NM. Pattern of bacterial profile and antibiotic susceptibility among neonatal sepsis cases at Cairo University Children Hospital. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 2020:15.39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2019.12.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Nwankwo, EOK, Shehu, AU, Farouk, ZL. Risk factors and bacterial profile of suspected neonatal septicaemia at a teaching hospital in Kano, Northwestern, Nigeria. Sierra Leone J Biomed Res 2011;3:104–9. https://doi.org/10.4314/sljbr.v3i2.71811.Search in Google Scholar

34. Medugu, N, Iregbu, K, Iroh Tam, P-Y, Obaro, S. Aetiology of neonatal sepsis in Nigeria, and relevance of Group b streptococcus: a systematic review. PLoS One 2018;13:e0200350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200350.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Akindolire, AE, Tongo, O, Dada-Adegbola, H, Akinyinka, O. Etiology of early onset septicemia among neonates at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries 2016;10:1338–44. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.7830.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Aku, FY, Akweongo, P, Nyarko, K, Sackey, S, Wurapa, F, Afari, EA, et al.. Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of common isolates of neonatal sepsis, Ho Municipality, Ghana-2016. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol 2018;4:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-017-0071-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Chan, GJ, Lee, AC, Baqui, AH, Tan, J, Black, RE. Prevalence of early-onset neonatal infection among newborns of mothers with bacterial infection or colonization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0813-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Droz, N, Hsia, Y, Ellis, S, Dramowski, A, Sharland, M, Basmaci, R. Bacterial pathogens and resistance causing community acquired pediatric blood-stream infections in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Contr 2019;8:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0673-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Akbarian-Rad, Z, Riahi, SM, Abdollahi, A, Sabbagh, P, Ebrahimpour, S, Javanian, M, et al.. Neonatal sepsis in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis on national prevalence and causative pathogens. PLoS One 2020;15:e0227570. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227570.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Phua, J, Ngerng, WJ, See, CK, Tay, CK, Kiong, T, Lim, HF, et al.. Characteristics and outcomes of culture-negative versus culture-positive severe sepsis. Crit Care 2013;17:R202. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12896.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Rishi, S, Panday, N, Lammers, EMJ, Alam, N, Nanayakkara, PWB. An overview of positive cultures and clinical outcomes in septic patients: a subanalysis of the Prehospital Antibiotics Against Sepsis (PHANTASi) trial. Crit Care 2019;23:182.10.1186/s13054-019-2431-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Shehab El-Din, EM, El-Sokkary, MM, Bassiouny, MR, Hassan, R. Epidemiology of neonatal sepsis and implicated pathogens: a study from Egypt. BioMed Res Int 2015;2015:509484. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/509484.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Opota, O, Croxatto, A, Prod’hom, G, Greub, G. Blood culture-based diagnosis of bacteraemia: state of the art. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:313–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.01.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Rawat, S, Neeraj, K, Preeti, K, Prashant, M. A review on type, etiological factors, definition, clinical features, diagnosis management and prevention of neonatal sepsis. J Sci Ind Res 2013;2:802–13.Search in Google Scholar

45. Miller, JM, Binnicker, MJ, Campbell, S, Carroll, KC, Chapin, KC, Gilligan, PH, et al.. A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2018 update by the infectious diseases society of America and the American society for microbiology. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:813–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy584.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Sweeney, TE, Liesenfeld, O, May, L. Diagnosis of bacterial sepsis: why are tests for bacteremia not sufficient? Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2019;19:959–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737159.2019.1660644.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Akya, A, Rostamian, M, Rezaeian, S, Ahmadi, M, Janatolmakan, M, Sharif, SA, et al.. Bacterial causative agents of neonatal sepsis and their antibiotic susceptibility in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and neonatal wards in Iran: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis 2020;8:e92212. https://doi.org/10.5812/pedinfect.92212.Search in Google Scholar

48. Verma, P, Berwal, PK, Nagaraj, N, Swami, S, Jivaji, P, Narayan, S. Neonatal sepsis: epidemiology, clinical spectrum, recent antimicrobial agents and their antibiotic susceptibility pattern. Int J Contemp Pediatr 2015;2:176–80. https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20150523.Search in Google Scholar

49. Li, JY, Chen, SQ, Yan, YY, Hu, YY, Wei, J, Wu, QP, et al.. Identification and antimicrobial resistance of pathogens in neonatal septicemia in China—a meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2018;71:89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2018.04.794.Search in Google Scholar

50. Waters, D, Jawad, I, Ahmad, A, Luksić, I, Nair, H, Zgaga, L, et al.. Aetiology of community-acquired neonatal sepsis in low and middle income countries. J Glob Health 2011;1:154–70.Search in Google Scholar

51. Huynh, BT, Padget, M, Garin, B, Herindrainy, P, Kermorvant-Duchemin, E, Watier, L, et al.. Burden of bacterial resistance among neonatal infections in low income countries: how convincing is the epidemiological evidence? BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0843-x.Search in Google Scholar

52. Mouiche, MMM, Moffo, F, Akoachere, JTK, Okah-Nnane, NH, Mapiefou, NP, Ndze, VN, et al.. Antimicrobial resistance from a one health perspective in Cameroon: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Publ Health 2019;19:1135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7450-5.Search in Google Scholar

53. O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations: government of the United Kingdom; 2016. Available from: http://amr-review.org/ [Accessed 27 Jan 2021].Search in Google Scholar

54. Ayukekbong, JA, Ntemgwa, M, Atabe, AN. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies. Antimicrob Resist Infect Contr 2017;6:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-017-0208-x.Search in Google Scholar

55. Holmes, AH, Moore, LSP, Sundsfjord, A, Steinbakk, M, Regmi, S, Karkey, A, et al.. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet 2016;387:176–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00473-0.Search in Google Scholar

56. WHO report on surveillance of antibiotic consumption: 2016–2018 early implementations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.Search in Google Scholar

57. Togoobaatar, G, Ikeda, N, Ali, M, Sonomjamts, M, Dashdemberel, S, Mori, R, et al.. Survey of non-prescribed use of antibiotics for children in an urban community in Mongolia. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:930–36. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.10.079004.Search in Google Scholar

58. Auta, A, Hadi, MA, Oga, E, Adewuyi, EO, Abdu-Aguye, SN, Adeloye, D, et al.. Global access to antibiotics without prescription in community pharmacies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2018;78:8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2018.07.001.Search in Google Scholar

59. Orrett, FA. Antimicrobial prescribing patterns at a rural hospital in Trinidad: evidence for intervention measures. Afr J Med Med Sci 2001;30:161–4.Search in Google Scholar

60. Chukwuani, CM, Onifade, M, Sumonu, K. Survey of drug use practices and antibiotic prescribing at a general hospital in Nigeria. Pharm World Sci 2002;24:188–95. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020570930844.10.1023/A:1020570930844Search in Google Scholar

61. Arya, SC. Antibiotics prescription in hospitalized patients at a Chinese university hospital. J Infect 2004;48:117–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0163-4453(03)00131-2.Search in Google Scholar

62. Abdulah, R. Antibiotic abuse in developing countries. Pharmaceut Reg Affairs 2012;1:e106.10.4172/2167-7689.1000e106Search in Google Scholar

63. Vialle‐Valentin, C, Lecates, R, Zhang, F, Desta, A, Ross‐Degnan, D. Predictors of antibiotic use in African communities: evidence from medicines household surveys in five countries. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:211–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02895.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

64. WHO report. Assessing non-prescription and inappropriate use of antibiotics. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Mengistu Abayneh et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- The COVID-19 Pandemia – Challenges in Laboratory Medicine

- Molecular (real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infections: complexity and challenges

- Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests

- Analysis of blood index characteristics in COVID-19 patients and their associations with different outcomes

- Opinion Paper

- Rational clinical use of near-patient analytical systems for molecular detection of infectious agents

- Review

- Bacterial profile and multi-drug resistance pattern of bacterial isolates among septicemia suspected cases: a meta-analysis report in Ethiopia

- Original Articles

- Parvovirus B19 associated autoantibodies upregulation in women and children in Southern China

- Effect of sample heating on results of therapeutic drug monitoring

- Short Communication

- Evaluation of a novel immunochromatographic assay using silver amplification technology for detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from throat swab samples in pediatric patients

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- The COVID-19 Pandemia – Challenges in Laboratory Medicine

- Molecular (real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infections: complexity and challenges

- Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests

- Analysis of blood index characteristics in COVID-19 patients and their associations with different outcomes

- Opinion Paper

- Rational clinical use of near-patient analytical systems for molecular detection of infectious agents

- Review

- Bacterial profile and multi-drug resistance pattern of bacterial isolates among septicemia suspected cases: a meta-analysis report in Ethiopia

- Original Articles

- Parvovirus B19 associated autoantibodies upregulation in women and children in Southern China

- Effect of sample heating on results of therapeutic drug monitoring

- Short Communication

- Evaluation of a novel immunochromatographic assay using silver amplification technology for detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from throat swab samples in pediatric patients