Evaluation of a novel immunochromatographic assay using silver amplification technology for detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from throat swab samples in pediatric patients

Abstract

Objectives

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is one of the common causative pathogens of community-acquired respiratory tract infections mainly in children and young adults. Rapid and accurate diagnostic techniques for identifying the causative pathogen would be useful for initiating treatment with an appropriate antibiotic. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of a novel immunochromatographic assay using silver amplification technology using FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG2 and FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG cartridge Myco (FUJIFILM Co., Tokyo, Japan) for detection of M. pneumoniae.

Methods

Throat swab samples were collected from 170 pediatric patients who were diagnosed with bronchitis or pneumonia. The silver amplification immunochromatographic (SAI) assay was performed using these samples and the results were compared with those of real-time PCR. The time required for the SAI assay is approximately 20 min (5 min for sample preparation and 15 min for waiting time after starting the assay).

Results

The sensitivity and specificity of the SAI assay for detection of M. pneumoniae were 85.2 and 99.1%, respectively, and the assay showed positive and negative predictive values of 98.1 and 92.3%, respectively, compared with the results of real-time PCR. The diagnostic accuracy was 94.1%.

Conclusions

FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG2 and FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG cartridge Myco are appropriate for clinical use. The optimal timing of this assay is five days or more after the onset of M. pneumoniae infection. However, PCR or other molecular methods are superior, especially with regard to sensitivity and negative predictive value.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is one of the common causative pathogens of community-acquired respiratory tract infections mainly in children and young adults [1]. Macrolides are generally considered to be the drugs of choice for treatment of children with M. pneumoniae infection [2]. However, macrolide-resistant (MR) M. pneumoniae has been emerging in Asia, Europe, Canada and the USA since about 2000 [3], [4], [5], [6]. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global public health concern and unnecessary use of antibiotics has contributed to the global emergence of antimicrobial resistance [7]. Rapid and accurate diagnostic techniques for identifying the causative pathogen would be useful for initiating treatment with an appropriate antibiotic. Nucleic acid amplification techniques (NAATs) including real-time PCR assay, multiplex real-time PCR assay and loop-mediated isothermal amplification have been increasingly used for identification of respiratory pathogens including M. pneumoniae in clinical specimens due to their high levels of sensitivity and specificity [8]. However, it has been reported that NAATs were used in only 4% of patients who were suspected of having M. pneumoniae infection in Japan [9]. For the majority of patients, an antibody testing (64% of patients) and antigen testing including an immunochromatographic assay (32% of patients) were used [9]. Therefore, an immunochromatographic assay for detection of M. pneumoniae is important for clinical use in Japan. An immunochromatographic assay is generally inferior to NAATs with regard to sensitivity and specificity. However, an immunochromatographic assay can be performed easily in approximately 15 min and does not require an expert technologist or special instruments.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of a highly sensitive rapid immuno-chromatographic assay using silver amplification technology using FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG2 and FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG cartridge Myco (FUJIFILM Co., Tokyo, Japan) in pediatric patients infected with M. pneumoniae compared with the results of real-time PCR (Figure 1). Although the immunogen of a monoclonal antibody used in the FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG cartridge Myco is undocumented, this assay does not cross-react with other species of Mycoplasma, at least 20 bacteria species, candida species and at least 19 viral species, according to the instructions of the assay.

The FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG2 (Fujifilm, Kanagawa, Japan) is an analyzer (A). The FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG Cartridge Myco (Fujifilm, Kanagawa, Japan) is a reagent cartridge for detection of M. pneumoniae (B).

Throat swab samples were collected from pediatric patients who were suspected of having respiratory tract infections associated with M. pneumoniae from May 2018 to March 2020 at Touei Hospital and Sapporo Kosei General Hospital in Hokkaido, Japan. The silver amplification immunochromatographic (SAI) assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions [10], [11]. Sterile throat swabs provided in the kit were gently inserted into the throat through the mouth and rubbed against the back of the throat or tonsils several times to collect mucosal epidermis. The swab containing a specimen was placed directly in a dedicated soft extraction tube containing 600 μL of sample extraction reagent solution provided in the kit. The swab was then squeezed while rotating it several times to extract antigens from the swab. The sample was assayed using FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG2 and FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG cartridge Myco. The time required for the SAI assay is approximately 20 min (5 min for sample preparation and 15 min for waiting time after starting the assay).

The principle of the immunochromatographic assay is based on silver halide photography technology. The sample is dropped onto the sample instilling section of the cartridge. The cartridge is set in the analyzer and then measurement starts. The result is displayed automatically after 15 min.

In order to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG2 and FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG cartridge Myco in comparison with real-time PCR, DNA was extracted with a DNA extraction kit (Smitest EX-R&D, Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Nagoya, Japan) from 100 μL of sample extraction reagent solution in the kit and was finally resuspended in 15 μL of buffer. One μL of DNA solution was quantified by real-time PCR using Mp181-F (TTTGGTAGCTGGTTACGGGAAT) and Mp181-R (GGTCGGCACGAATTTCATATAAG) primers and an Mp181-P probe ([FAM]-TGTACCAGAGCACCCCAGAAGGGCT-[BHQ-1]) as described elsewhere [12], [13], [14]. The plasmid containing PCR products of the real-time PCR in the vector pT7Blue (Novagene, Madison, WI, USA) was used as a positive control and for standard curves. The minimum concentrations of M. pneumoniae that would allow reproducible quantification were 10 copies per reaction. The results of real-time PCR were confirmed by two persons (NI and RS).

In order to investigate whether the assay could detect macrolide-resistant strains of M. pneumoniae, mutations associated with resistance to macrolides at sites 2,063, 2,064, and 2,617 in the M. pneumoniae 23S rRNA domain V gene region were detected by a sequencing method described elsewhere [15]. M. pneumoniae showing a point mutation in domain V of the 23S rRNA gene was defined as MR M. pneumoniae. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP software version 13.2.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

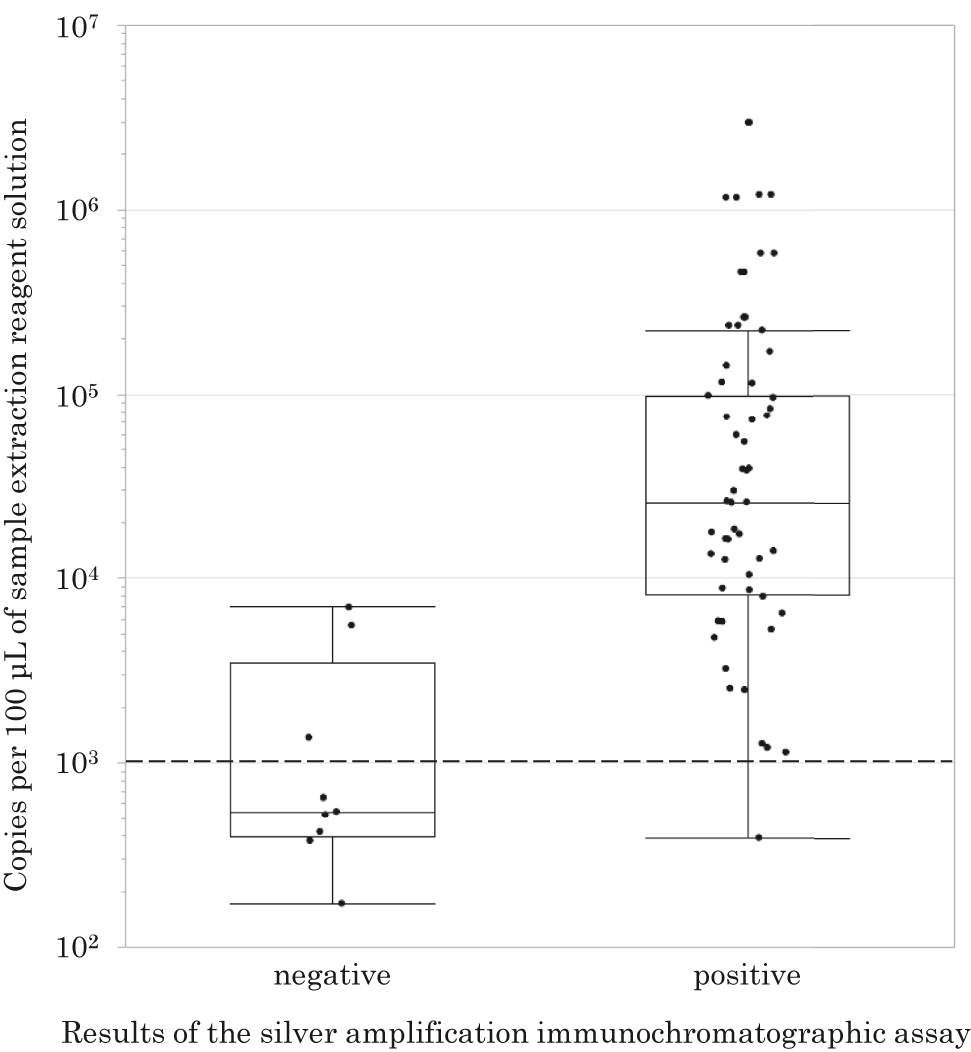

Throat swab samples were collected from 170 patients (94 males and 76 females) aged 0.8–18.6 years (average age, 7.6 years) who were diagnosed with bronchitis (n=91, 53.5%) or pneumonia (n=79, 46.5%). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or guardians. The mean body temperature of the patients was 38.2 °C (SD=1.0; range, 35.6–41.0 °C) and the mean sampling time after onset of illness was 4.0 days (SD=2.7; range, 0–15 days). M. pneumoniae was detected by real-time PCR from 61 of the 170 samples, and the copy numbers ranged from 1.72 × 102 to 2.97 × 106 copies per 100 μL of sample extraction reagent solution. M. pneumoniae was detected by the SAI assay from 51 (94.4%) of 54 samples for which copy numbers were over 1 × 103 copies per 100 μL of sample extraction reagent solution and from one (14.3%) of seven samples for which copy numbers were between 1 × 102 and 1 × 103 copies per 100 μL of sample extraction reagent solution (Figure 2). The SAI assay showed sensitivity and specificity of 85.2% (52/61) and 99.1% (108/109), respectively, and it showed positive and negative predictive values of 98.1% (52/53) and 92.3% (108/117), respectively. The diagnostic accuracy was 94.1% (160/170).

Relationship between copy numbers of M. pneumoniae per 100 μL of sample extraction reagent solution and results of the SAI assay.

According to the sentinel surveillance of M. pneumoniae infection by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases in Japan, the weekly numbers of M. pneumoniae patients were more than 0.2 from July 23, 2018 to February 3, 2019 and from August 12, 2019 to April 26, 2020 [16]. In these periods, 56 (91.8%) of 61 M. pneumoniae patients were diagnosed with a high probability.

Each dot represents the copy number of M. pneumoniae detected by real-time PCR. The first row shows copy numbers of M. pneumoniae that were negative by the SAI assay and the second row shows copy numbers of M. pneumoniae that were positive by the SAI assay. The dotted line shows the level of 1 × 103 copies per 100 μL of sample extraction reagent solution. The horizontal line inside the box represents the median, the lower and upper borders of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively, and the whiskers correspond to extension to 1.5 times the box width (i.e., the interquartile range) from both ends of the box.

Fourteen of the 61 patients with M. pneumoniae PCR-positive results were found to be infected with MR M. pneumoniae. All of those 14 patients had an A-to-G transition at position 2,063 in domain V of the 23S rRNA gene (A2063G). No mutations at site 2,064 or 2,617 in domain V of the 23S rRNA gene were observed. Twelve (85.7%) of 14 M. pneumoniae with A2063G mutation cases and 40 (85.1%) of 47 M. pneumoniae without mutation cases were detected by the SAI assay.

In the present study, the SAI assay showed sensitivity and specificity of 85.2% (52/61) and 99.1% (108/109), respectively, compared with the results of real-time PCR. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of other immuno-chromatographic assay kits for detecting M. pneumoniae in throat swabs have been reported to be 70 and 92%, respectively [1].

M. pneumoniae antigen level in the nasal cavity was significantly lower than that in the pharynx. This suggests that proliferating M. pneumoniae in the lower respiratory tract may have been transferred by coughing to the pharynx but not to the nasal cavity [17], [18]. Therefore, we used throat swab samples for the assay. Additionally, non-adherence to the validated technique is one reason why the performance of the assay often decrease in the setting of point of care testing.

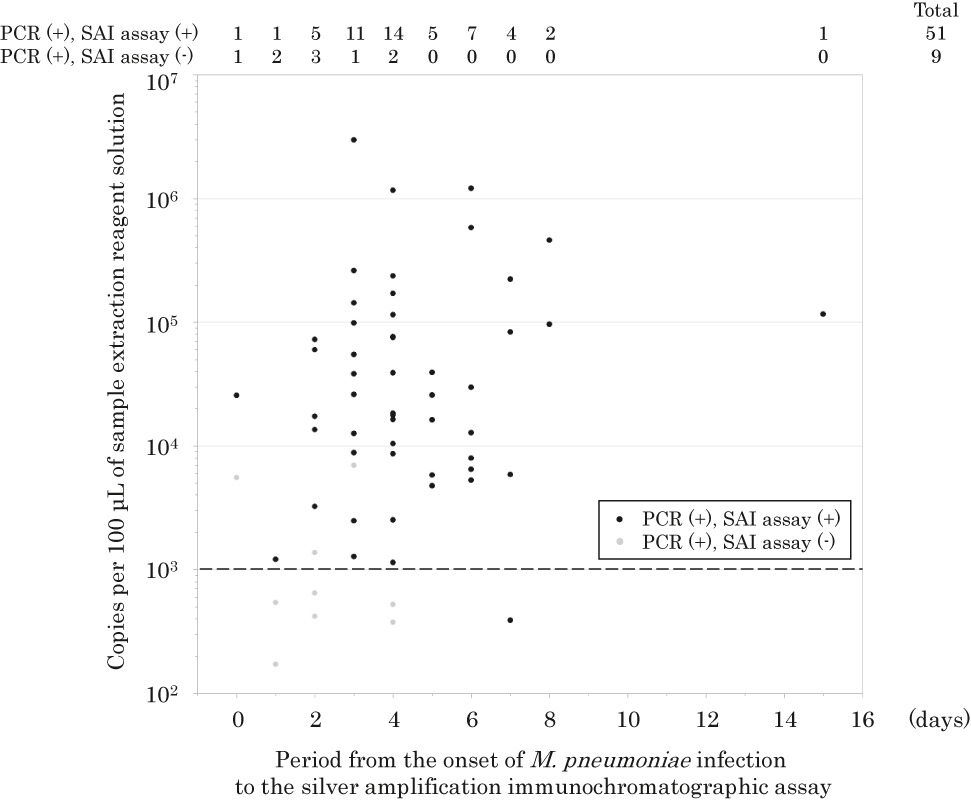

The time from onset of M. pneumoniae infection to the SAI assay and results of the real-time PCR assay are shown in Figure 3. M. pneumoniae in the real-time PCR-positive and SAI assay-negative samples (gray dots) was detected within four days after the onset of M. pneumoniae infection but was not detected in those samples 5–15 days after the onset of M. pneumoniae infection. These results suggest that the optimal timing of the SAI assay is five days or more after the onset of M. pneumoniae infection. There was no statistically significant difference in the copy numbers of M. pneumoniae between patients with bronchitis and those with pneumonia or between patients in different age groups.

Relationship between copy numbers of M. pneumoniae per 100 μL of sample extraction reagent solution and period from the onset of M. pneumoniae infection to the SAI assay.

Black dots represent real-time PCR-positive and SAI assay-positive samples, and gray dots represent real-time PCR-positive and SAI assay-negative samples. The dotted line shows the level of 1 × 103 copies per 100 μL of sample extraction reagent solution.

This study showed high sensitivity and high specificity of the SAI assay for detecting M. pneumoniae from throat swab samples. FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG2 and FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG cartridge Myco (FUJIFILM Co., Tokyo, Japan) are therefore appropriate for clinical use. However, PCR or other molecular methods are superior, especially with regard to sensitivity and negative predictive value.

Funding source: The research funds for this study including immunochromatographic assay kits, FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG2 and FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG cartridge Myco (FUJIFILM Co., Tokyo, Japan), were provided by FUJIFILM MEDICAL Co.

Award Identifier / Grant number: N/A

Acknowledgments

We thank Stewart Chisholm for proofreading the manuscript.

-

Research funding: The research funds for this study including immunochromatographic assay kits, FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG2 and FUJI DRI-CHEM IMMUNO AG cartridge Myco (FUJIFILM Co., Tokyo, Japan), were provided by FUJIFILM MEDICAL Co.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or guardians.

-

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Hokkaido University Hospital for Clinical Research (017-0443).

References

1. Yoon, SH, Min, IK, Ahn, JG. Immunochromatography for the diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2020;15:e0230338. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230338.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Waites, KB, Talkington, DF. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:697–728. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.17.4.697-728.2004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Okazaki, N, Ohya, H, Sasaki, T. Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolated from patients with respiratory infection in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1976–2006: emergence of macrolide-resistant strains. Jpn J Infect Dis 2007;60:325–6.10.7883/yoken.JJID.2007.325Search in Google Scholar

4. Li, X, Atkinson, TP, Hagood, J, Makris, C, Duffy, LB, Waites, KB. Emerging macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children: detection and characterization of resistant isolates. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009;28:693–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/inf.0b013e31819e3f7a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Pereyre, S, Charron, A, Renaudin, H, Bebear, C, Bebear, CM. First report of macrolide-resistant strains and description of a novel nucleotide sequence variation in the P1 adhesin gene in Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical strains isolated in France over 12 years. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:3534–9. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01345-07.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Eshaghi, A, Memari, N, Tang, P, Olsha, R, Farrell, DJ, Low, DE, et al.. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in humans, Ontario, Canada, 2010–2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19:1525–7. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1909.121466.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Berild, D, Abrahamsen, TG, Andresen, S, Bjørløw, E, Haug, O, Kossenko, IM, et al.. A controlled intervention study to improve antibiotic use in a Russian paediatric hospital. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008;31:478–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.01.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Diaz, MH, Winchell, JM. The evolution of advanced molecular diagnostics for the detection and characterization of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Front Microbiol 2016;7:232. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00232.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. The National Statistics Center. Statistics of medical care activities in public health insurance; 2019. Available from: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en.Search in Google Scholar

10. Namkoong, H, Yamazaki, M, Ishizaki, M, Endo, I, Harada, N, Aramaki, W, et al.. Clinical evaluation of the immunochromatographic system using silver amplification for the rapid detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Sci Rep 2018;8:1430. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19734-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Miyashita, N, Ogata, M, Fukuda, N, Nomura, S. Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae using a highly sensitive rapid diagnostic method with silver amplification technology. J Infect Chemother 2020;26:527–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2019.12.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Winchell, JM, Thurman, KA, Mitchell, SL, Thacker, WL, Fields, BS. Evaluation of three real-time PCR assays for detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in an outbreak investigation. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:3116–8. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.00440-08.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Ishiguro, N, Koseki, N, Kaiho, M, Kikuta, H, Togashi, T, Oba, K, et al.. Regional differences in prevalence of macrolide resistance among pediatric Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in Hokkaido, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis 2016;69:186–90. https://doi.org/10.7883/yoken.jjid.2015.054.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Ishiguro, N, Koseki, N, Kaiho, M, Ariga, T, Kikuta, H, Togashi, T, et al.. Therapeutic efficacy of azithromycin, clarithromycin, minocycline and tosufloxacin against macrolide-resistant and macrolide-sensitive Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in pediatric patients. PloS One 2017;12:e0173635. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173635.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Matsuoka, M, Narita, M, Okazaki, N, Ohya, H, Yamazaki, T, Ouchi, K, et al.. Characterization and molecular analysis of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical isolates obtained in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004;48:4624–30. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.48.12.4624-4630.2004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Infectious Disease Surveillance Center of National Institute of Infectious Diseases. Infectious diseases weekly report (IDWR); 2018–2019. Available from: https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/ja/idwr.html.Search in Google Scholar

17. Räty, R, Rönkkö, E, Kleemola, M. Sample type is crucial to the diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia by PCR. J Med Microbiol 2005;54:287–91. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.45888-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Onari, S, Okada, T, Okada, T, Okano, S, Kakuta, O, Kutsuma, H, et al.. Immunochromatography test for rapid diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Pediatr Int 2017;59:1123–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13383.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Nobuhisa Ishiguro et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- The COVID-19 Pandemia – Challenges in Laboratory Medicine

- Molecular (real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infections: complexity and challenges

- Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests

- Analysis of blood index characteristics in COVID-19 patients and their associations with different outcomes

- Opinion Paper

- Rational clinical use of near-patient analytical systems for molecular detection of infectious agents

- Review

- Bacterial profile and multi-drug resistance pattern of bacterial isolates among septicemia suspected cases: a meta-analysis report in Ethiopia

- Original Articles

- Parvovirus B19 associated autoantibodies upregulation in women and children in Southern China

- Effect of sample heating on results of therapeutic drug monitoring

- Short Communication

- Evaluation of a novel immunochromatographic assay using silver amplification technology for detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from throat swab samples in pediatric patients

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- The COVID-19 Pandemia – Challenges in Laboratory Medicine

- Molecular (real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infections: complexity and challenges

- Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests

- Analysis of blood index characteristics in COVID-19 patients and their associations with different outcomes

- Opinion Paper

- Rational clinical use of near-patient analytical systems for molecular detection of infectious agents

- Review

- Bacterial profile and multi-drug resistance pattern of bacterial isolates among septicemia suspected cases: a meta-analysis report in Ethiopia

- Original Articles

- Parvovirus B19 associated autoantibodies upregulation in women and children in Southern China

- Effect of sample heating on results of therapeutic drug monitoring

- Short Communication

- Evaluation of a novel immunochromatographic assay using silver amplification technology for detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from throat swab samples in pediatric patients