Abstract

Background: Soluble mesothelin-related peptide (sMRP) has shown great potential for malignant mesothelioma detection. However, data on comparison with other cancer and benign diseases as well as with other established lung cancer biomarkers are rare.

Methods: In this study, SMRP was investigated in sera from 1506 individuals including 147 healthy donors, 285 patients with diverse benign diseases and 1074 patients with mesothelioma (n=39) and various malignant tumors (lung, gastrointestinal, gynecological, urological). For differential diagnosis of lung diseases, carcinoembryonic antigen, cytokeratin 19-fragments (CYFRA 21-1), neuron-specific enolase and squamous cell cancer antigen were determined additionally.

Results: Ninety-fifth percentiles of sMRP serum levels in healthy persons were 1.2 nM, in patients with benign diseases between 2.0 and 3.8 nM and in cancer patients between 1.5 and 44.3 nM. Highest values were observed in mesothelioma (median 2.3 nM; 95th percentile 44.3 nM). When differential diagnostic capacity of cancer detection vs. the relevant benign control group was tested, sMRP showed best results for mesothelioma and ovarian cancer with a sensitivity of 45% and 37%, respectively, at 95% specificity. At 100% specificity vs. normal controls, sensitivity for mesothelioma detection was found to be 59% for sMRP, 73% for CYFRA 21-1 and 88% for the combination of both. At 95% specificity vs. all other lung diseases, sensitivity for mesothelioma was 48% for sMRP, 15% for CYFRA 21-1 and 46% for the combination of both.

Conclusions: In summary, SMRP is a valuable serum biomarker that is specific at high concentrations for the detection of malignant mesothelioma. For screening purposes, the combination with CYFRA 21-1 improves the sensitivity at high specificity.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund: Das lösliche Mesothelin Related Peptide (sMRP) zeigt großes Potential für die Detektion von malignen Mesotheliomen. Jedoch sind wenige Daten zum Vergleich mit anderen Tumorarten und benignen Erkrankungen wie auch mit anderen etablierten Biomarkern des Lungenkarzinoms verfügbar.

Methoden: In dieser Studie wurde sMRP in Sera von 1506 Personen untersucht, darunter 147 gesunde Kontrollpersonen, 285 Patienten mit unterschiedlichen benignen Erkrankungen und 1047 Patienten mit malignem Mesotheliom (n=39) und verschiedenen weiteren malignen Tumorerkrankungen (Lunge, gastrointestinale, gynäkologische, urologische). Zur Differentialdiagnose von Lungenerkrankungen wurden zusätzlich das carcinoembryonale Antigen, Cytokeratin 19-Fragmente (CYFRA 21-1), die Neuronen-spezifische Enolase und das Squamous Cell Cancer Antigen bestimmt.

Ergebnisse: Die 95. Perzentile der sMRP-Serumwerte bei gesunden Personen war 1.2 nM, bei Patienten mit benignen Erkrankungen zwischen 2.0 und 3.8 nM und bei Patienten mit einer Tumorerkrankung zwischen 1.5 und 44.3 nM. Die höchsten Werte wurden beim Mesotheliom beobachtet (Median 2.3 nM; 95. Perzentile 44.3 nM). Bei der Untersuchung des Potentials für die Differentialdiagnose von Tumoren und den relevanten benignen Erkrankungen zeigte sMRP die besten Ergebnisse für das Mesotheliom und das Ovarialkarzinom mit Sensitivitäten von 45% und 37% bei einer 95% Spezifität. Bei 100% Spezifität gegenüber gesunden Kontrollpersonen war die Sensitivität für die Erkennung eines Mesothelioms bei 59% für sMRP, 73% für CYFRA 21-1 und 88% für die Kombination der beiden Marker. Bei 95% Spezifität gegenüber allen anderen Lungenerkrankungen war die Sensitivität für das Mesotheliom 48% für sMRP, 15% für CYFRA 21-1 und 46% für die Kombination der beiden Marker.

Schlussfolgerungen: SMRP ist ein wertvoller Serum-Biomarker, welcher in hohen Konzentrationen das maligne Mesotheliom spezifisch erkennt. Beim Screening verbessert die Kombination mit CYFRA 21-1 die Sensitivität bei hoher Spezifität.

Reviewed Publication:

Holdenrieder S.

Statement

This study on serum samples of more than 1500 individuals shows a comprehensive view of the high diagnostic potential of soluble mesothelin-related peptide (sMRP) for the detection of mesothelioma and ovarian cancer but not for other solid malignancies when compared with healthy controls and the organ-specific benign diseases. While sMRP outperforms other lung serum biomarkers CEA, NSE and SCC with respect to mesothelioma detection in the screening situation, the combination of sMRP with CYFRA 21-1 improves sensitivity at high specificity as compared with both markers alone.

Introduction

Malignant mesothelioma is an aggressive tumor that is known to be closely associated with the exposure to asbestos. It affects serosal surfaces such as the pleura, the peritoneum or the pericardium and is often detected by chance when unexplained pleural effusion and pleural pain are present [1, 2]. Formerly a rare disease, the incidence of malignant mesothelioma is currently increasing worldwide, probably due to the asbestos exposure until the late 1980s in modern industrialized nations. As cancerogenesis in mesothelioma is known to occur over several decades, the peak of the incidence rate is expected to peak in 2020 in Europe and 2025 in Japan. In the United States the peak is supposed to have already passed in 2004, whereas in the developing world the still high exposure to asbestos will produce high numbers of mesothelioma patients in future [2].

The median survival of patients with malignant mesothelioma from the time of diagnosis is 12 months and could not be improved substantially during recent decades. However, recent developments in surgical, chemotherapeutical and immunotherapeutical treatment programs give hope to a more intensified research in this field [1–4]. Further reasons for the increasing interest in mesothelioma are the expected economic burdens of compensations for asbestos exposure which are supposed to account for $200 billion for the United States and $80 billion for Europe in the next 40 years [2].

Early detection of mesothelioma by clinical and radiological findings is still difficult. However, as biological changes during cancerogenesis are supposed to be mirrored by blood and bodily fluid markers, new blood-based techniques are sought to improve the early detection and by earlier treatment, hopefully, also the survival of patients suffering from mesothelioma [2, 5]. One promising approach is the development of assays for the quantification of soluble mesothelin-related peptide (sMRP) that showed an excellent performance for mesothelioma detection [6–11]. Those assays demonstrated good methodical prerequisites [11–13] and enabled the measurement of sMRP in serum, pleural effusion and urine [6–15].

The mesothelin antigen is a 40 kDa glycoprotein attachted to the cell surface by phosphatidylinositol, which has putative functions in cell-to-cell adhesion and possibly in cell-to-cell recognition and signalling [16–18]. It originates from a precursor 69 kDa protein that forms the membrane-bound mesothelin and a soluble protein megakaryocyte potentiating factor (MPF) [6, 7]. Mesothelin is recognized by the monoclonal antibody OV569 on normal mesothelial cells [16], and is overexpressed on malignant mesothelioma [19, 20], ovarian cancer [17, 19, 21], pancreatic cancer [22, 23], sarcomas [23], gastrointestinal cancers [19, 24] and lung cancers [19, 25] but not on healthy tissues.

Even if the exact mechanism of mesothelin release from mesothelial cells is not clear yet, it was detected in elevated amounts in serum of patients with mesothelioma and ovarian cancer [6–11, 17, 26–28]. These studies were based on the OV569 antibody which was shown to also detect a third member of the mesothelin family [17]; therefore, the antigens measured in blood were named sMRP [6]. In several reports, sMRP was shown to specifically discriminate mesothelioma patients from other lung-related diseases particularly from individuals who have been exposed to asbestos [6–11, 27–29]. Others have compared sMRP with MPF and found similar or better diagnostic performance for sMRP [30, 31]. While osteopontin was found to have high diagnostic potential in mesothelioma as well [32], a recent study showed that the combination of sMRP and ostopontin further improves the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity [33]. In contrast, sMRP was superior to hyaluronic acid [34], CA 125 and cytokeratin 19 fragments (CYFRA 21-1) in the diagnosis of mesothelioma [35]. Further studies showed the relevance of sMRP in therapy monitoring and prognosis of mesothelioma [8, 9, 36]. In addition, the first therapeutic approach to target mesothelin-related peptides in mesothelioma using a chimeric anti-mesothelin monoclonal antibody MORAb-009 was reported [37].

Despite the numerous studies on sMRP in mesothelioma and lung diseases, there are only few systematic data available on the release of sMRP in various malignant and non-malignant diseases so far [11]. However, comprehensive knowledge on the marker release would be necessary if sMRP is used as a screening tool for mesothelioma. Although earlier studies indicated a role of other lung cancer biomarkers for mesothelioma detection such as CYFRA 21-1 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) [38–41], there are few reports on the direct comparison of sMRP with those lung cancer biomarkers [35, 41].

Following the recommendations of the European Group on Tumor Markers (EGTM) [42] for the clinical investigation of new biomarkers, we started a comprehensive study including patients with a variety of cancer types as well as with various benign diseases that potentially interfere with the mesothelin metabolism. Further, we investigated other serum biomarkers in parallel which are already established for lung cancer detection such as CEA, CYFRA 21-1, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and squamous cell cancer antigen (SCCA) [43–45] to enable a fair comparison with sMRP for differential diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma and to test any potential additive value of the markers for mesothelioma detection.

Materials and methods

Patient sera

The current study was done retrospectively using 1506 samples of frozen serum stored at –80 °C. We included samples from 147 healthy donors, 285 patients with benign diseases and 1074 patients with malignant tumors. The group with benign diseases included 106 patients with lung diseases (tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, allergic, autoimmune and infectious lung diseases and others), 50 with benign gastrointestinal diseases (adenoma, polyposis, colitis, Crohn’s disease, gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, cholecystolithiasis and others), 49 with gynecologic diseases (ovarian cysts, endometriosis, uterus myomatosus and others), 50 with breast diseases (mastitis, fibroadenoma and others) and 30 with benign urological diseases (nephritis, nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency and others). Serum samples were obtained at time of diagnosis or at acute stage of disease before start of the respective therapy, i.e., prior to surgery, anti-inflammatory or antibiotic treatment, etc.

The group with malignant diseases comprised 39 patients with pleural mesothelioma, 476 with lung cancer, 69 with nasopharyngeal cancer, 214 with gastrointestinal cancers (esophagus, stomach, hepatocellular, pancreatic, colorectal and anal cancer), 171 with gynecological cancers (ovarian, cervical and uterus cancer), 49 with breast cancer and 56 with urological cancers (prostate and renal cell cancer). Serum samples from all cancer patients were obtained prior to surgery, which was the most frequent treatment modality, or before start of chemotherapy or radiotherapy, respectively.

All samples were centrifuged, aliquoted and stored at –80 °C at day of collection. They were thawed only once for measurement of the markers. Study samples were residues of samples that were drawn for routine diagnostics of patients treated at the University Hospital Munich; therefore, no additional blood was taken from patients beyond that for clinical diagnostic purposes. All clinical patient data were anonymized at time of evaluation.

Methods

Serum levels of sMRP were determined by a sandwich ELISA (Fujirebio Diagnostics, Malvern, PA, USA) using monoclonal 4H3 as capture and monoclonal OV 569 as tracer antibody. In brief, patient sera and calibrator control were incubated in microplates coated with 4H3 antibodies for 1 h. Subsequently, plates were washed and incubated with conjugate containing OV 569 antibodies for 1 h. Finally, plates were washed and developed using the TMB Peroxidase Substrate System for 15 min. Then HCL stop solution was added, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Calculation of concentrations was done using software of Courbes RD and a four-point calibration curve.

Serum levels of cytokeratin 19 fragments (CYFRA 21-1), CEA and NSE were measured by electrochemoluminescense using the Elecsys 2010 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). SCCA was determined at the ImX System (Abbott Diagnostics, Wiesbaden, Germany).

Statistical analysis

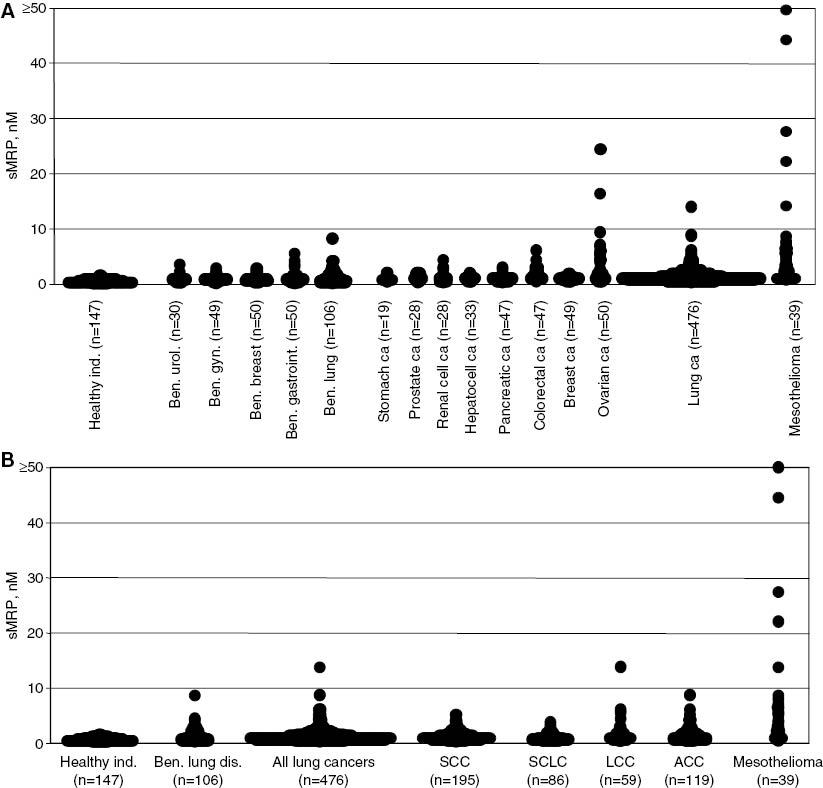

SMRP concentrations in sera of healthy individuals, patients with benign diseases and cancer patients were expressed graphically as dot plots and statistically as median, range, and 75th and 95th percentiles.

To assess the diagnostic capacity of sMRP, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were established to cover the entire spectrum of sensitivity and specificity. This analysis was done for all cancer types investigated when compared with the relevant benign control group, and areas under the curves (AUC) were given. In addition, diagnostic sensitivity of sMRP at 95% specificity vs. the relevant benign control group was indicated.

To assess the diagnostic capacity of sMRP for mesothelioma detection in comparison with other established lung cancer biomarkers such as CYFRA 21-1, CEA, NSE and SCCA, ROC curves were established for all markers using various control groups: healthy individuals, patients with benign lung diseases and patients with all (benign and malignant) lung diseases. In addition, diagnostic sensitivity of all markers at 95% specificity vs. the various control groups were indicated. Finally, these calculations were done for the combination of sMRP and CYFRA 21-1, too. Combination of two markers in ROC curves was done by testing sensitivity and specificity at all possible cutoff combinations. At a given specificity the best sensitivity of the combinations was chosen.

Results

Tumor specificity

Serum sMRP levels showed only low concentrations in healthy individuals ranging from 0.1 to 1.6 nM with the median at 0.5 nM and the 95th percentile at 1.2 nM (Table 1 and Figure 1). In benign diseases, sMRP levels were only slightly higher with medians between 0.7 and 0.8 nM, as well as 95th percentiles between 2.0 and 3.8 nM. Highest values up to 8.4 nM were observed in single patients with benign lung diseases; however, the 95th percentile was only at 2.8 nM in this group. Slightly higher at 3.8 nM was the 95th percentile in patients with benign gastrointestinal diseases including those with impaired liver function potentially relevant for sMRP metabolism. sMRP levels in benign gynecological and breast diseases were homogeneously low, ranging up to 2.9 and 2.8 nM (95th percentiles 2.0 and 2.4 nM, respectively). Benign urological diseases such as renal insufficiency potentially involved in sMRP elimination did not affect sMRP concentrations, too. Highest values observed were 3.5 nM, and the 95th percentile was at 2.8 nM (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Serum levels of sMRP.

(A) Serum levels of sMRP in healthy individuals, patients with benign diseases and patients with malignant tumors. (B) Serum levels of sMRP in healthy individuals and in patients with benign lung diseases and with lung cancer and its various histological subtypes (SCC, squamous cell cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; LCC, large-cell cancer; ACC, adeno cell cancer) and with mesothelioma.

SMRP levels in sera of healthy individuals and patients with various benign and cancer diseases.

| Diagnosis | Subtype | n | Median, nM | Range, nM | 75th percentile, nM | 95th percentile, nM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy individuals | 147 | 0.5 | 0.1–1.6 | 0.7 | 1.2 | |

| Benign gastrointestinal diseases | 50 | 0.8 | 0.2–5.5 | 1.2 | 3.8 | |

| Benign breast diseases | 50 | 0.8 | 0.3–2.8 | 0.8 | 2.4 | |

| Benign gynecological diseases | 49 | 0.7 | 0.1–2.9 | 1.1 | 2.0 | |

| Benign urological diseases | 30 | 0.7 | 0.3–3.5 | 0.9 | 2.8 | |

| Benign lung diseases | 106 | 0.8 | 0.2–8.4 | 1.6 | 2.8 | |

| Esophagus cancer | 49 | 0.7 | 0.1–3.8 | 1.1 | 2.8 | |

| Stomach cancer | 19 | 0.6 | 0.3–2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | |

| Hepatocellular cancer | 33 | 1.0 | 0.3–1.9 | 1.2 | 1.8 | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 47 | 0.7 | 0.1–2.8 | 0.9 | 2.4 | |

| Colorectal cancer | 47 | 1.2 | 0.4–6.0 | 1.9 | 3.6 | |

| Anal cancer | 19 | 0.7 | 0.1–3.5 | 1.3 | 3.5 | |

| Breast cancer | 49 | 0.8 | 0.3–1.8 | 1.0 | 1.5 | |

| Ovarian cancer | 50 | 1.5 | 0.3–24.1 | 4.1 | 19.8 | |

| Cervix cancer | 90 | 0.8 | 0.1–3.2 | 1.1 | 2.4 | |

| Endometrial cancer | 31 | 0.9 | 0.4–3.8 | 1.2 | 3.2 | |

| Prostate cancer | 28 | 0.9 | 0.2–2.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

| Renal cell cancer | 28 | 0.8 | 0.2–4.1 | 1.0 | 3.5 | |

| ENT cancer | 69 | 0.8 | 0.2–3.9 | 1.3 | 2.7 | |

| Lung cancer | 476 | 0.9 | 0.1–13.7 | 1.4 | 2.7 | |

| SCC | 195 | 0.9 | 0.1–4.9 | 1.4 | 2.5 | |

| ACC | 119 | 1.1 | 0.3–8.7 | 1.7 | 4.1 | |

| LCC | 59 | 1.0 | 0.3–13.7 | 1.5 | 5.4 | |

| SCLC | 86 | 0.7 | 0.3–3.6 | 1.1 | 2.3 | |

| Other histologies | 17 | |||||

| Mesothelioma | 39 | 2.3 | 0.4–50.0 | 6.3 | 44.3 |

Organ specificity

Also in various cancer diseases, sMRP levels were only slightly elevated. In gastrointestinal cancers, median levels ranged between 0.6 nM in gastric cancer and 1.2 nM in colorectal cancer. The highest concentrations were found in colorectal cancer up to 6.0 nM and a 95th percentile at 3.6 nM. Lower were the 95th percentiles in anal cancer (3.5 nM), esophagus cancer (2.8 nM), pancreatic cancer (2.4 nM), gastric cancer (2.0 nM) and hepatocellular cancer (1.8 nM), respectively. Similarly, low or even lower values were observed in breast cancer (median 0.8 nM; 95th percentile 1.5 nM) and gynecological cancers such as cervical cancer (median 0.8 nM; 95th percentile 2.4 nM) and endometrial cancer (median 0.9 nM; 95th percentile 3.2 nM). However, patients with ovarian cancer had a considerably higher release of sMRP with concentrations up to 24.1 nM (median 1.5 nM; 95th percentile 19.8 nM). As expected, very high value levels up to 50.0 nM were found in mesothelioma patients, too. In this group, the median was at 2.3 nM and the 95th percentile at 44.3 nM. In contrast, other lung tumors showed only slightly elevated sMRP levels (median 0.9 nM; 95th percentile 2.7 nM) (Table 1 and Figure 1A).

Histological specificity

Among the various histological lung cancer subtypes, medians were in a comparable range between 0.7 and 1.1 nM. However, 95th percentiles were highest for adenocarcinoma (4.1 nM) and large-cell cancer (5.4 nM), which are known to be the most relevant ones for differential diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. In these subgroups, single patients showed serum sMRP levels up to 13.7 nM (Table 1 and Figure 1B).

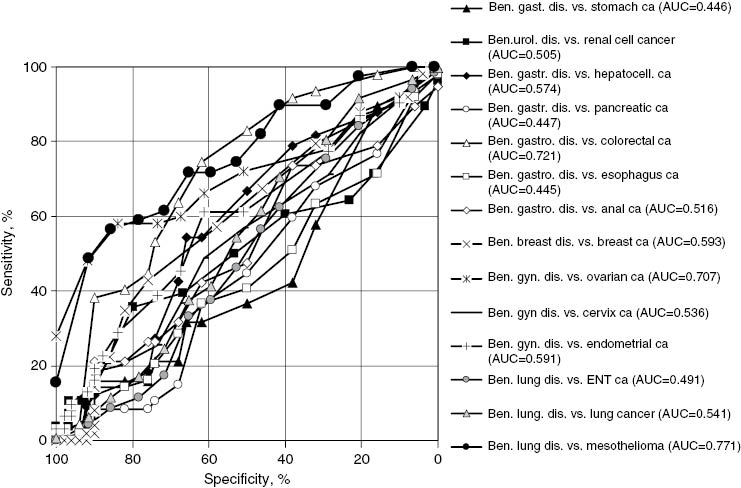

ROC curves illustrating the diagnostic capacity of sMRP for the detection of various cancers vs. the respective benign control group over the whole spectrum of sensitivity and specificity.

Diagnostic sensitivity for cancer detection

Following the recommendations of the EGTM [42] for the clinical investigation of new biomarkers, the diagnostic capacity of sMRP for the detection of various cancers was assessed by ROC curves when compared with the relevant benign control groups (Table 2 and Figure 3). Corresponding with the low sMRP value ranges found in most cancer types, the differential diagnostic potential of sMRP was poor, particularly for esophageal, gastric, hepatocellular, pancreatic, anal, breast, cervical, endometrial, renal, nasopharyngeal and lung cancer, respectively, with AUCs <0.60. Accordingly, the diagnostic sensitivity for cancer detection at 95% specificity vs. the relevant benign control group was lower than 10% for all these cancer types. Higher diagnostic sensitivities were only found for the detection of mesothelioma with an AUC of 0.77 and a diagnostic sensitivity of 45% at 95% specificity vs. benign lung diseases, for ovarian cancer with an AUC of 0.71 and a diagnostic sensitivity of 37% at 95% specificity vs. benign gynecological diseases, and for colorectal cancer with an AUC of 0.72 but only a diagnostic sensitivity of 4% at the high specificity level of 95% vs. benign gastrointestinal diseases (Table 2 and Figure 2).

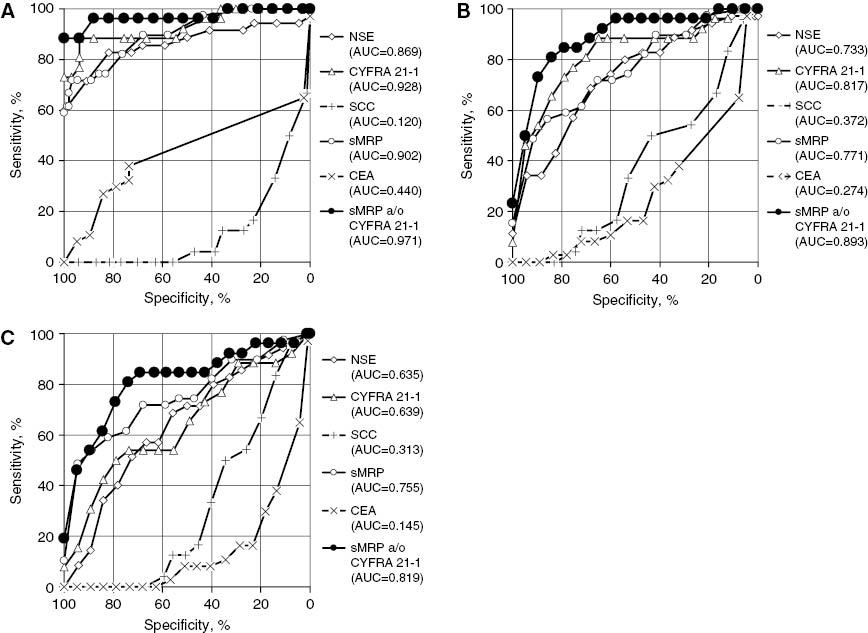

ROC curves illustrating the diagnostic capacity of sMRP, CYFRA 21-1, CEA, NSE, SCC and the combination of sMRP and CYFRA 21-1 for the detection of malignant mesothelioma when compared (A) with the group of healthy individuals, (B) with the group of patients with benign lung diseases, and (C) with the group of patients with all other lung diseases being benign or malignant.

Diagnostic capacity of sMRP for the detection of various cancers indicated by the AUC of the ROC curves and the sensitivity at 95% specificity versus the relevant benign comparison group.

| Diagnosis | n | Sensitivity at 95% specificity vs. the relevant benign comparison group | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagus cancer | 49 | 2% | 0.445 |

| Stomach cancer | 19 | 0% | 0.446 |

| Hepatocell. cancer | 33 | 0% | 0.574 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 47 | 0% | 0.447 |

| Colorectal cancer | 47 | 4% | 0.721 |

| Anal cancer | 19 | 0% | 0.516 |

| Breast cancer | 49 | 0% | 0.593 |

| Ovarian cancer | 50 | 37% | 0.707 |

| Cervical cancer | 90 | 8% | 0.536 |

| Endometrial cancer | 31 | 9% | 0.591 |

| Renal cell cancer | 28 | 10% | 0.505 |

| ENT cancer | 69 | 3% | 0.491 |

| Lung cancer | 476 | 4% | 0.541 |

| Mesothelioma | 39 | 45% | 0.771 |

Comparison of diagnostic sensitivity for mesothelioma with other lung cancer biomarkers

According to the recommendations of the EGTM [42], the diagnostic capacity of sMRP for the detection of mesothelioma was compared with other established lung cancer biomarkers such as CYFRA 21-1, CEA, NSE and SCCA vs. various control groups. Against healthy individuals, sMRP (AUC 0.90; 71% sensitivity at 95% specificity) and CYFRA 21-1 (AUC 0.93; 75% sensitivity at 95% specificity) turned out to be the best parameters followed by NSE (AUC 0.87; 66% sensitivity at 95% specificity). In contrast, CEA and SCCA showed “negative” ROC curves with AUCs of 0.44 for CEA and even 0.12 for SCCA, meaning that mesothelioma patients had lower marker levels than healthy individuals. If a combination of the best markers sMRP and CYFRA 21-1 was established, results were further improved, reaching an AUC of 0.97 and a diagnostic sensitivity of 88% at 95% specificity (Table 3 and Figure 3A).

Diagnostic capacity of sMRP, CYFRA 21-1, CEA, NSE, SCC and the combination of sMRP and CYFRA 21-1 for the detection of malignant mesothelioma given by the AUC of the ROC curve and the sensitivity at 95% specificity versus healthy individuals, benign lung diseases, lung cancer and all lung diseases, respectively.

| Marker | Mesothelioma vs. healthy individuals | Mesothelioma vs. benign lung diseases | Mesothelioma vs. lung cancer | Mesothelioma vs. all lung diseases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity at 95% specificity | Sensitivity at 100% specificity | AUC | Sensitivity at 95% specificity | AUC | Sensitivity at 95% specificity | AUC | Sensitivity at 95% specificity | AUC | |

| SMRP | 71% | 59% | 0.902 | 45% | 0.771 | 48% | 0.751 | 48% | 0.755 |

| CYFRA 21-1 | 75% | 73% | 0.928 | 46% | 0.817 | 11% | 0.610 | 15% | 0.639 |

| NSE | 66% | 60% | 0.869 | 32% | 0.733 | 8% | 0.615 | 8% | 0.635 |

| CEA | 8% | 0% | 0.440 | 0% | 0.274 | 0% | 0.119 | 0% | 0.145 |

| SCC | 0% | 0% | 0.120 | 0% | 0.372 | 0% | 0.300 | 0% | 0.313 |

| SMRP a/o CYFRA 21-1 | 88% | 88% | 0.880 | 50% | 0.893 | 46% | 0.807 | 46% | 0.819 |

When benign lung diseases, which are known to be associated with higher serum concentrations of biomarkers than healthy individuals, were considered as control group, the resulting AUCs were somewhat lower. Once again, sMRP (AUC 0.77; 45% sensitivity at 95% specificity) and CYFRA 21-1 (AUC 0.82; 46% sensitivity at 95% specificity) turned out to be the best parameters. The combination of both improved the AUC to 0.89 and the diagnostic sensitivity to 50% at 95% specificity (Table 3 and Figure 3B).

The differential diagnosis of mesothelioma from other lung cancers by serum markers is supposed to be difficult, because various lung cancer subtypes are known to release high amounts of various biomarkers. Therefore, when lung cancers were considered as control group, the diagnostic sensitivity of most markers for mesothelioma detection dropped down such as for CYFRA 21-1 (AUC 0.61; only 11% sensitivity at 95% specificity), NSE (AUC 0.62; only 8% sensitivity at 95% specificity), CEA (AUC 0.12; 0% sensitivity at 95% specificity) and SCCA (AUC 0.30; 0% sensitivity at 95% specificity). However, because sMRP is released only rarely by other lung tumors, its diagnostic sensitivity for mesothelioma remained high with an AUC of 0.75 and a sensitivity of 48% at 95% specificity. Here, the combination with CYFRA 21-1 achieved only a marginal improvement (AUC 0.81; 46% sensitivity at 95% specificity) (Table 3).

If, finally, mesothelioma was differentiated from all other lung diseases, being benign or malignant, sMRP was clearly still superior to CYFRA 21-1 (AUC 0.76 vs. 0.64; 48% vs. 15% sensitivity at 95% specificity). Once again, the combination of both markers resulted in an only slightly higher AUC of 0.82. However, the diagnostic sensitivity (46%) at 95% specificity could not be improved with respect to the sole use of sMRP (Table 3 and Figure 3C).

Diagnostic sensitivity for mesothelioma screening

Specific preconditions are given if biomarkers are used for screening purposes. Most individuals investigated will be healthy or will, at least, not have severe diseases. If a marker is relevant in this setting, it should provide a high sensitivity at an extremely high specificity, to achieve as few false positive results as possible. Therefore, the diagnostic sensitivity of all markers for mesothelioma detection was tested at a specificity level of 100% against healthy individuals. Then, the highest sensitivities were found for CYFRA 21-1 with 73%, NSE with 60% and sMRP with 59%. However, if CYFRA 21-1 and sMRP were combined, diagnostic sensitivity was improved to 88% (Table 3 and Figure 3A).

Discussion

Because of its increasing incidence as a consequence of widespread asbestos exposure during the recent decades and its limited therapeutic options, malignant mesothelioma is a persistent medical challenge. In addition, high economic compensations are expected in many modern industrialized nations for asbestos-related diseases in the next years [1, 2]. However, diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma by clinical investigation and imaging techniques remains difficult [1, 5]. Because the shedding of tumor-related proteins is an early feature in cancerogenesis, much emphasis has been given to the research and development of new mesothelioma serum markers [6, 46]. Two molecules, the sMRP and osteopontin [6, 7, 32], have shown great potential for mesothelioma detection. sMRP was elevated in more than 80% of mesothelioma patients when compared with healthy persons and/or patients with benign lung diseases at a specificity of more than 80% [6, 27]. Similar results were obtained for osteopontin with a sensitivity for mesothelioma detection of 78% at a specificity of 86% vs. asbestos exposed individuals [32]. Recently, the combination of sMRP and osteopontin was shown to have additive impact, and an index of both markers was proposed to improve diagnostic accuracy [33].

Despite these promising results, release of sMRP in various malignant and non-malignant diseases have been investigated only sporadically so far [11, 17]. Therefore, it was the aim of this study to test a representative number of a variety of cancer entities and benign diseases which might interfere with the mesothelin metabolism to evaluate the differential diagnostic relevance sMRP for other cancer diseases. Further, a comparison with other lung cancer biomarkers should clarify the specific role of sMRP for mesothelioma detection and/or the potential additive value of a marker panel as it is recommended by the guidelines of the EGTM [42].

As expected, serum sMRP levels were low in healthy individuals but considerably elevated in mesothelioma and ovarian cancer patients. In other benign and malignant diseases, only single patients showed elevated sMRP values; medians were mostly comparable with those of healthy persons. This fact appears to be highly relevant if sMRP is used as screening tool for mesothelioma detection. Neither any other cancer disease nor hepatic, renal, infectious or other benign pathologies interfere with the release and/or the concentration of sMRP in patients’ serum. In contrast to our findings, a recent report indicates some effect of renal function and also of age and body mass index on sMRP values [47]. In consequence, diagnostic capacity of sMRP for the detection of most cancer types compared with the relevant benign control groups was poor. It was only for mesothelioma and ovarian cancer that satisfying results were obtained with sensitivities of 45% and 37% at a 95% specificity vs. the relevant benign control group.

Earlier studies have found higher sensitivities of sMRP for mesothelioma detection but at a considerably lower cutoff discrimination level [6, 11, 27]. A very high diagnostic capacity of sMRP for the diagnosis of mesothelioma was found in our study when healthy individuals served as control group. Then, a sensitivity of 71% at a specificity of 95% was obtained. Even better was the performance of CYFRA 21-1 (75% sensitivity at 95% specificity) and the combination of both markers (88% sensitivity at 95% specificity). Interestingly, CEA and SCCA showed a negative ROC curve indicating that mesothelioma patients had even lower serum levels than healthy individuals. This is in line with earlier reports on CEA negativity in pleural effusion of mesothelioma patients [41, 48].

When mesothelioma should be differentiated from all lung diseases being benign or malignant, sMRP was clearly superior to CYFRA 21-1. The drop of diagnostic sensitivity of CYFRA 21-1 in this comparison was expected because of the well-known increased release of this marker in other lung cancer diseases [43–45]. The non-release of sMRP in other lung cancer histologies, however, underlined its high specificity for mesothelioma in high value levels. Here, the combination of both markers could not improve the diagnostic capacity to the sole use of sMRP.

As cancer diagnosis in the screening situation is associated with numerous consecutive and sometimes invasive investigations as well as with an enormous psychological burden, particularly if the tested individuals feel healthy, the diagnostic method has to be highly specific for a defined tumor disease. If in our study a specificity of 100% vs. normal controls was required, the single parameters sMRP and CYFRA 21-1 achieved a sensitivity of 59% and 73%, and the combination of both markers resulted in a sensitivity of 88%. As it is known for many tumor-related molecules that median serum concentrations of healthy persons but also of tumor patients are far below the so-called reference range and the release of these biomarkers during carcinogenesis occurs already at low value levels [44], it seems to be promising to include sMRP and CYFRA 21-1 kinetics in future trials to enhance the diagnostic sensitivity at a high specificity. Additional options are the inclusion of further biomarkers such as osteopontin, MPF, the vascular endothelial growth factor and microRNA biomarkers that have shown high diagnostic and/or prognostic power in mesothelioma management [32, 49, 50].

Conclusions

Taken together, our study provides comprehensive information regarding the clinical value of sMRP analysis in various benign and malignant diseases. We demonstrate that sMRP has high potential for the differential diagnosis of mesothelioma and ovarian cancer. In other cancer types the diagnostic potential is, as expected, very low. Specific interferences by benign diseases have not been observed. Depending on the control group, sMRP and CYFRA 21-1 achieved the best sensitivity for mesothelioma detection and had a clear additive sensitivity. To our knowledge, these comprehensive data show for the first time the high diagnostic power of the combination of sMPR and CYFRA 21-1 for the detection of malignant mesothelioma. The inclusion of longitudinal sMRP and CYFRA 21-1 values in prospective trials might further strengthen their relevance for mesothelioma screening.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Conzelmann and Dr. Cartalas from CisBio Diagnostics for providing sMRP assays and technical assistance.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Pass HI, Vogelzang N, Hahn S, Carbone M. Malignant pleural mesothelioma. Curr Probl Cancer 2004;28:93–174.10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2004.04.001Search in Google Scholar

2. Robinson BW, Lake RA. Advances in malignant mesothelioma. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1591–603.10.1056/NEJMra050152Search in Google Scholar

3. Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, Denham C, Kaukel E, Ruffie P, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2636–44.10.1200/JCO.2003.11.136Search in Google Scholar

4. Tsao AS, Wistuba I, Roth JA, Kindler HL. Malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2081–90.10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8523Search in Google Scholar

5. Sterman DH, Albelda SM. Advances in the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Respirology 2005;10:266–83.10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00714.xSearch in Google Scholar

6. Robinson BW, Creaney J, Lake R, Nowak A, Musk AW, de Klerk N, et al. Mesothelin-family proteins and diagnosis of mesothelioma. Lancet 2003;362:1612–6.10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14794-0Search in Google Scholar

7. Creaney J, Robinson BW. Detection of malignant mesothelioma in asbestos-exposed individuals: the potential role of soluble mesothelin-related protein. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2005;19:1025–40.10.1016/j.hoc.2005.09.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Grigoriu BD, Scherpereel A, Devos P, Chahine B, Letourneux M, Lebailly P, et al. Utility of osteopontin and serum mesothelin in malignant pleural mesothelioma diagnosis and prognosis assessment. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:2928–35.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2144Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Schneider J, Hoffmann H, Dienemann H, Herth FJ, Meister M, Muley T. Diagnostic and prognostic value of soluble mesothelin-related proteins in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma in comparison with benign asbestosis and lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:1317–24.10.1097/JTO.0b013e318187491cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Cristaudo A, Foddis R, Vivaldi A, Guglielmi G, Dipalma N, Filiberti R, et al. Clinical significance of serum mesothelin in patients with mesothelioma and lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:5076–81.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0629Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Beyer HL, Geschwindt RD, Glover CL, Tran L, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE, et al. MESOMARK: a potential test for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Clin Chem 2007;53:666–72.10.1373/clinchem.2006.079327Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Weber DG, Taeger D, Pesch B, Kraus T, Brüning T, Johnen G. Soluble mesothelin-related peptides (SMRP) – high stability of a potential tumor marker for mesothelioma. Cancer Biomark 2007;3:287–92.10.3233/CBM-2007-3602Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Di Serio F, Fontana A, Loizzi M, Capotorto G, Maggiolini P, Mera E, et al. Mesothelin family proteins and diagnosis of mesothelioma: analytical evaluation of an automated immunoassay and preliminary clinical results. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007;45:634–8.10.1515/CCLM.2007.112Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Pass HI, Wali A, Tang N, Ivanova A, Ivanov S, Harbut M, et al. Soluble mesothelin-related peptide level elevation in mesothelioma serum and pleural effusions. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:265–72.10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.042Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Creaney J, Musk AW, Robinson BW. Sensitivity of urinary mesothelin in patients with malignant mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1461–6.10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181e392d7Search in Google Scholar

16. Chang K, Pai LH, Pass H, Pogrebniak HW, Tsao MS, Pastan I, et al. Monoclonal antibody K1 reacts with epithelial mesothelioma but not with lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:259–68.10.1097/00000478-199203000-00006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Scholler N, Fu N, Yang Y, Ye Z, Goodman GE, Hellstrom KE, et al. Soluble member(s) of the mesothelin/megakaryocyte potentiating factor family are detectable in sera from patients with ovarian carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:11531–6.10.1073/pnas.96.20.11531Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Rump A, Morikawa Y, Tanaka M, Minami S, Umesaki N, Takeuchi M, et al. Binding of ovarian cancer antigen CA125/MUC16 to mesothelin mediates cell adhesion. J Biol Chem 2004;279:9190–8.10.1074/jbc.M312372200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Chang K, Pastan I. Molecular cloning of mesothelin, a differentiation antigen present on mesothelium, mesotheliomas, and ovarian cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:136–40.10.1073/pnas.93.1.136Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Ordonez NG. Value of mesothelin immunostaining in the diagnosis of mesothelioma. Mod Pathol 2003;16:192–7.10.1097/01.MP.0000056981.16578.C3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Yen MJ, Hsu CY, Mao TL, Wu TC, Roden R, Wang TL, et al. Diffuse mesothelin expression correlates with prolonged patient survival in ovarian serous carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:827–31.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1397Search in Google Scholar

22. Hassan R, Laszik ZG, Lerner M, Raffeld M, Postier R, Brackett D. Mesothelin is overexpressed in pancreaticobiliary adenocarcinomas but not in normal pancreas and chronic pancreatitis. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;124:838–45.10.1309/F1B64CL7H8VJKEAFSearch in Google Scholar

23. Ordonez NG. Application of mesothelin immunostaining in tumor diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:1418–28.10.1097/00000478-200311000-00003Search in Google Scholar

24. Liebig B, Brabletz T, Staege MS, Wulfanger J, Riemann D, Burdach S, et al. Forced expression of deltaN-TCF-1B in colon cancer derived cell lines is accompanied by the induction of CEACAM5/6 and mesothelin. Cancer Lett 2005;223:159–67.10.1016/j.canlet.2004.10.013Search in Google Scholar

25. Frierson HF Jr, Moskaluk CA, Powell SM, Zhang H, Cerilli LA, Stoler MH, et al. Large-scale molecular and tissue microarray analysis of mesothelin expression in common human carcinomas. Hum Pathol 2003;34:605–9.10.1016/S0046-8177(03)00177-1Search in Google Scholar

26. McIntosh MW, Drescher C, Karlan B, Scholler N, Urban N, Hellstrom KE, et al. Combining CA 125 and SMR serum markers for diagnosis and early detection of ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2004;95:9–15.10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.07.039Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Scherpereel A, Grigoriu B, Conti M, Gey T, Gregoire M, Copin MC, et al. Soluble mesothelin-related peptides in the diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1155–60.10.1164/rccm.200511-1789OCSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Hassan R, Remaley AT, Sampson ML, Zhang J, Cox DD, Pingpank J, et al. Detection and quantitation of serum mesothelin, a tumor marker for patients with mesothelioma and ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:447–53.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1477Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Creaney J, Olsen NJ, Brims F, Dick IM, Musk AW, de Klerk NH, et al. Serum mesothelin for early detection of asbestos-induced cancer malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:2238–46.10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0346Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Hollevoet K, Nackaerts K, Thimpont J, Germonpré P, Bosquée L, De Vuyst P, et al. Diagnostic performance of soluble mesothelin and megakaryocyte potentiating factor in mesothelioma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:620–5.10.1164/rccm.200907-1020OCSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Creaney J, Yeoman D, Demelker Y, Segal A, Musk AW, Skates SJ, et al. Comparison of osteopontin, megakaryocyte potentiating factor, and mesothelin proteins as markers in the serum of patients with malignant mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:851–7.10.1097/JTO.0b013e318180477bSearch in Google Scholar

32. Pass HI, Lott D, Lonardo F, Harbut M, Liu Z, Tang N, et al. Asbestos exposure, pleural mesothelioma, and serum osteopontin levels. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1564–73.10.1056/NEJMoa051185Search in Google Scholar

33. Cristaudo A, Bonotti A, Simonini S, Vivaldi A, Guglielmi G, Ambrosino N, et al. Combined serum mesothelin and plasma osteopontin measurements in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:1587–93.10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821e1c08Search in Google Scholar

34. Grigoriu B, Chahine B, Zerimech F, Grégoire M, Balduyck M, Copin MC, et al. Serum mesothelin has a higher diagnostic utility than hyaluronic acid in malignant mesothelioma. Clin Biochem 2009;42:1046–50.10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.03.007Search in Google Scholar

35. Gube M, Taeger D, Weber DG, Pesch B, Brand P, Johnen G, et al. Performance of biomarkers SMRP, CA125, and CYFRA 21-1 as potential tumor markers for malignant mesothelioma and lung cancer in a cohort of workers formerly exposed to asbestos. Arch Toxicol 2011;85:185–92.10.1007/s00204-010-0580-2Search in Google Scholar

36. Grigoriu BD, Chahine B, Vachani A, Gey T, Conti M, Sterman DH, et al. Kinetics of soluble mesothelin in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma during treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:950–4.10.1164/rccm.200807-1125OCSearch in Google Scholar

37. Hassan R, Cohen SJ, Phillips M, Pastan I, Sharon E, Kelly RJ, et al. Phase I clinical trial of the chimeric anti-mesothelin monoclonal antibody MORAb-009 in patients with mesothelin-expressing cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:6132–8.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2275Search in Google Scholar

38. Marukawa M, Hiyama J, Shiota Y, Ono T, Sasaki N, Taniyama K, et al. The usefulness of CYFRA 21-1 in diagnosing and monitoring malignant pleural mesothelioma. Acta Med Okayama 1998;52:119–23.Search in Google Scholar

39. Schouwink H, Korse CM, Bonfrer JM, Hart AA, Baas P. Prognostic value of the serum tumour markers Cyfra 21-1 and tissue polypeptide antigen in malignant mesothelioma. Lung Cancer 1999;25:25–32.10.1016/S0169-5002(99)00044-6Search in Google Scholar

40. Paganuzzi M, Onetto M, Marroni P, Filiberti R, Tassara E, Parodi S, et al. Diagnostic value of CYFRA 21-1 tumor marker and CEA in pleural effusion due to mesothelioma. Chest 2001;119:1138–42.10.1378/chest.119.4.1138Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. van den Heuvel MM, Korse CM, Bonfrer JM, Baas P. Non-invasive diagnosis of pleural malignancies: the role of tumour markers. Lung Cancer 2008;59:350–4.10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.08.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. European Group on Tumour Markers (EGTM). Consensus recommendations. Anticancer Res 1999;19:2785–820.Search in Google Scholar

43. Molina R, Holdenrieder S, Auge JM, Schalhorn A, Hatz R, Stieber P. Diagnostic relevance of circulating biomarkers in patients with lung cancer. Cancer Biomark 2010;6:163–78.10.3233/CBM-2009-0127Search in Google Scholar

44. Stieber P, Heinemann V. Sensible use of tumor markers. J Lab Med 2008;32:339–60.Search in Google Scholar

45. Stieber P, Holdenrieder S. Lung cancer biomarkers – where we are and what we need. Cancer Biomark 2010;6:221–4.10.3233/CBM-2009-0132Search in Google Scholar

46. van der Bij S, Schaake E, Koffijberg H, Burgers JA, de Mol BA, Moons KG. Markers for the non-invasive diagnosis of mesothelioma: a systematic review. Br J Cancer 2011;104:1325–33.10.1038/bjc.2011.104Search in Google Scholar

47. Hollevoet K, Nackaerts K, Thas O, Thimpont J, Germonpré P, De Vuyst P, et al. The effect of clinical covariates on the diagnostic and prognostic value of soluble mesothelin and megakaryocyte potentiating factor. Chest 2012;141:477–84.10.1378/chest.11-0129Search in Google Scholar

48. Fuhrman C, Duche JC, Chouaid C, Abd Alsamad I, Atassi K, Monnet I, et al. Use of tumor markers for differential diagnosis of mesothelioma and secondary pleural malignancies. Clin Biochem 2000;33:405–10.10.1016/S0009-9120(00)00157-0Search in Google Scholar

49. Demirag F, Unsal E, Yilmaz A, Caglar A. Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor, tumor necrosis, and mitotic activity index in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Chest 2005;128:3382–7.10.1378/chest.128.5.3382Search in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Santarelli L, Strafella E, Staffolani S, Amati M, Emanuelli M, Sartini D, et al. Association of MiR-126 with soluble mesothelin-related peptides, a marker for malignant mesothelioma. PLoS One 2011;6:e18232.10.1371/journal.pone.0018232Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2015 by De Gruyter

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Klinische Chemie und Stoffwechsel/Clinical Chemistry and Metabolism

- Lipoprotein(a): wann messen, wie behandeln?

- Endokrinologie/Endocrinology

- Qualitätssicherung der Analytik von Wachstumshormon und Insulin-Like Growth Factor I bei Erkrankungen der somatotropen Achse

- Hämostaseologie/Hemostaseology

- Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria revisited: news on pathophysiology, clinical course and treatment

- Onkologie/Oncology

- Biomarker – vom Sein und Wesen

- Improved diagnosis of mesothelioma by a combination of soluble mesothelin-related peptide and CYFRA 21-1

- Point-of-Care Testing

- Kongressbericht: 2. Münchner POCT-Symposium, 15. – 17. September 2014, Klinikum rechts der Isar der TU München

- Buchbesprechungen/Book Reviews

- A practical guide to ISO 15189 in laboratory medicine

- A practical guide to ISO 15189 in laboratory medicine

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Klinische Chemie und Stoffwechsel/Clinical Chemistry and Metabolism

- Lipoprotein(a): wann messen, wie behandeln?

- Endokrinologie/Endocrinology

- Qualitätssicherung der Analytik von Wachstumshormon und Insulin-Like Growth Factor I bei Erkrankungen der somatotropen Achse

- Hämostaseologie/Hemostaseology

- Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria revisited: news on pathophysiology, clinical course and treatment

- Onkologie/Oncology

- Biomarker – vom Sein und Wesen

- Improved diagnosis of mesothelioma by a combination of soluble mesothelin-related peptide and CYFRA 21-1

- Point-of-Care Testing

- Kongressbericht: 2. Münchner POCT-Symposium, 15. – 17. September 2014, Klinikum rechts der Isar der TU München

- Buchbesprechungen/Book Reviews

- A practical guide to ISO 15189 in laboratory medicine

- A practical guide to ISO 15189 in laboratory medicine