Summary

The current article wishes to reassess the Christian texts mentioning Queen Zenobia’s potential affinity to Judaism, or her conversion to Judaism. It will be shown that the claims against the reliability of these texts are deficient or inaccurate. Furthermore, it will be clarified that she was not Jewish from birth. Instead, the sources indicate that she had a special relationship with monotheism, and Judaism in particular, and that she may have wished to convert to Judaism or did so in secret. The reasoning for this action and her relationship with Judaism will be examined while considering her politically precarious position, as well as the place of monotheism and Judaism in Palmyra, the Roman East and the Roman Army. Through this, the current article wishes to provide a better, more accurate presentation of Zenobia’s religious inclinations, how she used and manoeuvred between an ambiguous monotheism and Judaism in order to gain power and support, and what was her raison d’être for such a move and choice.

Zenobia of Palmyra is one of the most famous female leaders in history. Her story sparks the imagination,[1] as she attempted to challenge the hegemony of the Roman Empire. This fascination with Zenobia tends to centre on her political exploits and the expansion of her power, with relatively little attention paid to the personal qualities and beliefs which may have facilitated her early successes, or were employed by her in their attainment. Accordingly, the current article wishes to take a different route to examine and try to answer whether Queen Zenobia of Palmyra ever converted to Judaism, and if she did, what her potential motives were for such an action. Despite the influx of books,[2] and articles,[3] on Zenobia in the last two decades, only a few pages were dedicated to her Jewishness and none of the publications presented nor discussed all the available ancient texts.[4]

Her religious inclinations, or her possible conversion, must be examined in the context of her success, or possibly as one of its reasons, as many leaders consciously decide to show affiliation or align themselves to certain faiths and historical figures to further their goals. For example, Zenobia identified herself with Cleopatra when invading and controlling parts of Egypt.[5] Cleopatra herself, like other members of the Ptolemaic dynasty, took the title of Pharaoh, a deified monarch, i.e. a living god. Furthermore, Zenobia possibly mimicked Cleopatra and other Hellenistic rulers by filling her court with philosophers, such as Cassius Longinus, who will be noteworthy to the article’s debate.[6] Similar to many other rulers in history, Zenobia juggled numerous identities to achieve support from different groups.[7] Therefore, the current article will suggest that her relationship with monotheism, specifically Judaism and Christianity, needs to be examined through this prism.

The texts referencing her Jewishness or conversion were mentioned and partially analysed in previous publications, both in the framework of the debate around Paul of Samosata,[8] and concerning Zenobia herself.[9] However, a thorough examination of all the available evidence and an attempt to reconcile between them,[10] was never conducted. Furthermore, there has been no attempt to understand the reasons behind the wording and composition of these texts, nor has anyone endeavoured to understand Zenobia’s religious inclinations, intentions and underlying reasoning.

Nevertheless, before attempting to examine Zenobia’s conversion, it is important to highlight the two main arguments against her being Jewish from birth or converting to Judaism at a later age. Firstly, all the sources discussing her potential Jewish identity are Christian texts, with the majority of them, except for one, mentioning this in the context of Paul of Samosata.[11] He was an archbishop hailing from Antioch, whose theological views aligned with Monarchianism,[12] a doctrine that accentuated God as one, akin to Aryanism, in contrast to the Catholic Church’s doctrine of the Holy Trinity.[13] As a result of his beliefs, he was deemed a heretic by other Christian denominations. Secondly, there is an utter absence of any reference to her conversion in either the Jerusalem or the Babylonian Talmud,[14] which were the main scriptures of Rabbinic Judaism in the 4th to 7th centuries CE.[15]

In an attempt to solve these questions and issues, the current article intends to start with a very short general introduction to Queen Zenobia’s world, followed by an analysis of the Christian texts which mention her Jewishness or conversion to Judaism. This analysis will be conducted chronologically, dealing with each of the texts while determining their accuracy and implications. Secondly, an examination of the Rabbinic attitude to Zenobia, and their references to her, will be scrutinised to understand why they did not mention her possible conversion. This will be conducted alongside a presentation on the presence and impact of Jews and Judaism in Palmyra and other regions of the Near East. Finally, this article will examine the significance of Monotheism, particularly Judaism, as a means for garnering support and manpower for her wars. This will be accomplished by analysing the phenomenon of Jewish military service in the Roman Army during the 3rd century. Through all these points of analysis and debates, the present article aims to provide a comprehensive and precise understanding of Zenobia’s beliefs. It will highlight how she skilfully used and manoeuvred between ambiguous Monotheism and Judaism to gain power and support and examine her ‘raison d’êtres’ for such moves and choices.

Zenobia’s World

In order to debate Queen Zenobia’s Jewish status, it is important to first understand who she was, the period in which she lived and the situation of the Roman Empire at the time. In the 3rd century CE, the Roman Empire was battling both internal and external forces which rendered the empire weak.[16] Germanic tribes were pressuring the western frontier of the Empire along the whole of the Danube, while Shapur I, King of Persia, dealt numerous crushing defeats to the Romans on the Eastern frontier of the empire.[17] Furthermore, the empire lost Gaul, Iberia and Britania when Postumus revolted and created the Gallic Empire in 260 CE.[18]

Odaenathus, the King of Palmyra and Zenobia’s husband, helped the Romans to stabilise their eastern front, and even conducted campaigns against the Persians. There are debates regarding the extent of the autonomy he achieved for Palmyra,[19] and how much territory was under active Palmyrene control before his death in 267 CE.[20] Nevertheless, it seems his wife, Queen Zenobia, was the de facto creator of the Palmyrene Empire, which at its height controlled territories from Asia minor (modern day Turkey) in the north, to the heartland of Egypt in the south.[21] Zenobia eventually ruled most of the Roman East, yet only for a short time as she was defeated by Emperor Aurelian in his swift military campaign of 272 CE.[22]

The Christian Testimonies

Now that the stage is set, it is necessary to examine the texts that discuss Zenobia and her possible Jewishness chronologically. The earliest source on her Jewish identity was written by Athanasius of Alexandria in his Historia Arianorum, where he mentions her Jewishness in relation to Paul of Samosata:

Πότε οὖν ἠκούσθη τοσαύτη παρανομία; πότε τι τοιοῦτον κἂν ἐν διωγμῷ γέγονε κακόν; Ἕλληνες γεγόνασιν οἱ πρότερον διώξαντες, ἀλλ‘ οὐκ εἰς τὰς ἐκκλησίας εἰσήνεγκαν τὰ εἴδωλα. Ἰουδαία ἦν Ζηνοβία καὶ Παύλου προέστη τοῦ Σαμοσατέως, ἀλλ‘ οὐ δέδωκε τὰς ἐκκλησίας τοῖς Ἰουδαίοις εἰς συναγωγάς.[23]

“When was ever such iniquity heard of? when was such an evil deed ever perpetrated, even in times of persecution? They were heathens who persecuted formerly; but they did not bring their images into the Churches. Zenobia, was a Jewess, and a supporter of Paul of Samosata; but she did not give up the Churches to the Jews for Synagogues.”[24]

It is important to note that he discusses Zenobia not in the harshest tone as he reveals she did not convert the churches into synagogues. This text also implies that the members of the church had issues with Zenobia’s belief, not her gender,[25] and had even more concerns with the types of Christian beliefs that flourished in her domain, such as Monarchianism, the sect to which Paul of Samosata belonged. Furthermore, this is one of the texts where it is suggested that she may have been Jewish by birth, as her conversion is not stated. However, despite such testimony, past scholars argued that Zenobia was not Jewish from birth, but she might have had inclinations towards Judaism and possibly even converted.[26] Although this is the earliest text on this matter, it is vital to remember that Athanasius lived and wrote many decades after the events in the text.[27]

Due to the importance of Paul of Samosata to this current debate, a few words of note regarding this figure are required. As can be learnt from Eusebius, Paul of Samosata eventually succeeded Demetrianus as bishop of Antioch in 260 CE.[28] During his term, Paul was accused of being a heretic and was eventually declared as such around 269 CE. Yet, he refused to accept the ruling and stayed in office, leading his opponents to make a successful petition against him to Aurelian (r. 270–275 CE).[29] It was suggested that one of the reasons Aurelian agreed to rule on a Christian matter, and why Christians petitioned him, was because Paul was considered one of Zenobia’s followers and a member of her court, and they felt that Aurelian would be favourable in acting against him.

The second relevant text was written by Philastrius of Brescia in his discussions regarding heresy published around 384 CE.[30] In this text, which was written a few decades after Athanasius writings, Philastrius declared that Paul of Samosata assisted Zenobia in her conversion to Judaism:

[…] unde et Zenobiam quandam reginam in oriente tunc temporis ipse docuit iudaeizare […][31]

“[…] also taught Zenobia, at that time a queen in the East, to become a Jew […]”

Unlike Athanasius’ testimony, which was ambiguous on Zenobia being Jewish by birth or whether she converted to Judaism, Philastrius clearly states that Zenobia converted to Judaism. Moreover, Zenobia is described as a follower of Paul of Samosata (maybe because of her Jewishness) in Athanasius’ story, yet in Philastrius’ account, he was the reason for her conversion. Regarding this narrative, Millar even alleged: “We cannot actually disprove the third version of the story, that of Filastrius, that Paul influenced Zenobia in the direction of Judaism.”[32] However, unlike what was declared by Millar, it is improbable that Paul was the reason, or the vessel, for her conversion to Judaism. As he was certainly not Jewish, the story may have confused between two different perceptions and stories. Nevertheless, what is certain is that it was commonly believed that Zenobia favoured Judaism, which possibly created a good foundation for her relationship with Paul, as his Christian beliefs were not as dissimilar from Judaism compared to the beliefs of other Christian sects.

A few years after Philastrius, John Chrysostom,[33] blamed Zenobia for being the cause of the heresy of Paul of Samosata:[34]

οὐδὲ γὰρ ἀγνοῶν, ἀλλὰ καὶ σφόδρα εἰδὼς ἡμάρτανε, ταὐτὸν παθὼν τοῖς Ἰουδαίοις. καθάπερ γὰρ ἐκεῖνοι πρὸς ἀνθρώπους ὁρῶντες, τὸ τῆς πίστεως προὔδωκαν ὑγιες, εἰδότες μὲν ὅτι αὐτός ἐστιν ὁ μονογενὴς Υἱὸς τοῦ Θεοῦ, διὰ δὲ τοὺς ἄρχοντας οὐχ ὁμολογοῦντες, ἵνα μὴ ἀποσυνάγωγοι γένωνται· οὕτω καὶ τοῦτον γυναικί τινι χαριζόμενον, τὴν σωτηρίαν φασὶν ἀποδόσθαι τὴν ἑαυτοῦ.[35]

“For he erred not ignorantly but with full knowledge, being in the same case as the Jews. For as they, looking to men, gave up sound faith, knowing that he was the only-begotten Son of God, but not confessing Him, because of their rulers, lest they should be cast out of the synagogue; so it is said that he (Paul), to gratify a certain woman (Zenobia), sold his own salvation.”[36]

This text suggests the Zenobia was Jewish, yet it is important to consider that this text may be inaccurate. Paul was already accused of heresy in 264 CE, and several times after, before being formally declared as a heretic in the council of 269 CE,[37] well before the Palmyrene Empire seized control of Antioch and Zenobia was its sole ruler.[38] Moreover, it is highly unlikely Zenobia was Jewish by birth.[39] Nonetheless, this text, like others, continues to associate Zenobia with Judaism, thus suggesting there may be truth to this theory.

The testimony of Theodoret of Cyrus from the middle of the 5th century,[40] similarly blames Zenobia for Paul of Samosata’s fall into heresy and claims that Zenobia held Jewish beliefs. Yet, it is unclear from this text whether she was Jewish from birth or converted:

Παῦλος δὲ ὁ Σαμοσατεὺς τῆς μὲν Ἀντιοχέων ἐπίσκοπος ἦν, Ζηνοβίας δὲ κατ᾿ ἐκεῖνον τὸν καιρὸν τοπαρχούσης (Πέρσαι γὰρ Ῥωμαίους νενικηκότες ταύτῃ παρέδοσαν τὴν τῆς Συρίας καὶ Φοινίκης ἡγεμονίαν) εἰς τὴν Ἀρτέμωνος ἐξώκειλεν αἵρεσιν, ταύτῃ νομίζων θεραπεύειν ἐκείνην τὰ Ἰουδαίων φρονοῦσαν.[41]

“Paul of Samosata was bishop of Antioch. During that time Zenobia was the ruler (for the Persians, having defeated the Romans, handed authority over Syria and Phoenicia to her). [Paul] fell in with the heresy of Artemon, thinking that by this he would do service to that [woman i.e Zenobia] which held Jewish beliefs.”[42]

Once again, Zenobia’s Jewish belief is mentioned in the same breath as Paul of Samosata, although in this account, Paul is said to have fallen to the heresy of Artemon (or Artemas).[43] This makes the story peculiar and illogical as if Zenobia preferred Judaism, why would the belief in Artemon help Paul gain Zenobia’s favour? Furthermore, as stated previously, Paul was accused as a heretic long before Zenobia was in sole power, or Antioch was under her control, and therefore would not have “fallen into heresy” for Queen Zenobia’s sake. This confusion between different faiths and sects in these texts, and the melding of different stories, highlights the problematic nature of the Christian sources on Queen Zenobia’s Jewish identity, rendering the pursuit of truth more challenging.

Nevertheless, numerous members of different Christian circles evidently associated Zenobia with Judaism, often in connection with Paul of Samosata. Thus, there is a likelihood that there is an element of truth to these accounts and anecdotes. But what part of these stories are true? How reliable is the connection between her and Judaism? The association of Paul with Judaism could be just slander but, as Millar pointed out, scholars:

“[…] cannot prove that Paul was not influenced by members of the substantial Jewish community in Antioch; […] But whatever was said in later Christian literature about the Judaising tendencies of Paul or his followers, this particular line of attack was not used, so far as we know, by his contemporaries. On the contrary, they clearly regarded his heresy as a revival of that of Artemon (or Artemas).”[44]

The same can be said for a text in Syriac from around 664 CE, which blames Zenobia for Paul’s heresy and so, may again be considered inaccurate as he was condemned as a heretic long before he joined her court:

“The cause of his downfall was his association with a woman the Persians had established over Syria and Phoenicia when they defeated the Romans; her name was Zenobia. As Paul wanted to please her and she was interested in all things concerning the Jews, he was led into the heresy of Artemon.”[45]

It is interesting to note that the text once again implies that Paul went astray and became a heretic for Zenobia, who was interested in Judaism and may have wished to convert. This seems improbable, especially as the relation between the heresy of Artemon and Judaism appears dubious. It is plausible this statement may have been included due to a common Christian phrasing of Paul of Samosata’s beliefs, as some later Christian writers considered his beliefs very similar to Judaism. For example, Epiphanius claimed that the difference between Paul’s disciples and the Jews is that his disciples did not observe the Sabbath or practice circumcision.[46] However, similar to the previous texts, excluding Philastrius’, what is integral to the debate is her affinity with Judaism which was independent of Paul’s acts or heresy. Accordingly, the possibility that his unrelated heresy was confused with a different account of her religious preferences is valid, as this narrative must have originated from a specific context. Otherwise, if the story was fiction, it would be more logical for the author to claim Paul’s heresy of Artemon was encouraged by Queen Zenobia’s heresy of Artemon. Hence, this information, i.e. her Jewish inclination, came from a different source which was probably unconnected to Paul of Samosata.

What may be the most important text on the matter of her conversion was composed relatively late, and can be found in the Bibliotheca of Photios I of Constantinople:[47]

ϕασὶ δὲ τὸν Δημοσθένην δ‘ καὶ κ‘ ἔτη γεγονότα τὸν περὶ τῶν ἀτελείων ἤτοι τὸν πρὸς Λεπτίνην ϕιλοπονήσασθαι λόγον, οὗ τὸ προοίμιον Λογγῖνος μὲν ὁ κρίτικὸς ἀγωνιστικὸν νομίζει· ἐπὶ Κλαυδίου δὲ οὗτος ἤκμαζε, καὶ τὰ πολλὰ συνηγωνίζετο Ζηνοβίᾳ τῇ τῶν Ὀσροηνῶν βασιλίδι, τὴν ἀρχὴν κατεχούσῃ Ὀδενάθου τοῦ ἀνδρὸς αὐτῆς τετελευτηκότος, ἣν καὶ μεταβαλεῖν εἰς τὰ Ἰουδαίων ἔθη ἀπὸ τῆς Ἑλληνικῆς δεισιδαιμονίας παλαιὸς ἀναγράϕει λόγος· ἀλλὰ γὰρ ὁ μὲν Λογγῖνος τοιαύτην περὶ τοῦ προειρημένου προοιμίου ψῆρον ἐξάγει.[48]

“They say that at the age of 24 Demosthenes worked on the discourse On the [tax] exemptions or Against Leptines, the exordium of which is considered as combative by the critic Longinus. Longinus lived under Claudius, and he often did legal business for Zenobia, queen of Osrohene, who reigned after the death of her husband Odenathus. An old tradition reports that she adopted Jewish customs and abandoned pagan superstition. However, Longinus gave the opinion on the exordium that I mentioned. Others have wrongly said that the exordium is of a moralising type.”[49]

This is the first text where Zenobia’s conversion to Judaism is mentioned without discussing Paul of Samosata, and instead discusses her conversion to Judaism as part of a wider debate on the philosopher Longinus. Her association with the philosopher, who could have been a member of her court,[50] is attested by non-Christian sources, thereby lending credibility to Photios’ text. Conversely, her connection to Samosata is solely discussed in Christian sources.[51] The Photios’ Bibliotheca heavily relies on the writings of ancient historians, such as Aryan, Diodorus Sicilius, as well as others whose writings often survived only thanks to Photios’ work, and so this text can be viewed as relatively reliable. This is strengthened by the fact that this extract corresponds, and may be supported by, what is written in other texts, such as the Historia Augusta.[52] Thus, it is probable that Photios had an account/s mentioning her inclination towards Judaism that was independent of any Christian figure, including Paul of Samosata, and this source/s inspired the writing of all the previous Christian texts.

To summarise, there are several inaccuracies in the texts which discuss Queen Zenobia’s Jewish beliefs in relation to Paul, and thus it is possible to consider Photios’ text as the most accurate. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Photios’ assertion regarding her Jewishness is cautious, taking care to mention that the source of this story is an ancient tradition. Nevertheless, he must have felt that this tradition has a strong basis in order to include it in his text. Furthermore, Photios was aware that Zenobia was not born Jewish, but rather had tendencies toward Judaism or converted to it, as seen in his depiction of her relationship with the religion. Accordingly, Miller (who never mentioned this text in his article) is correct regarding the nature of Zenobia’s Jewish identity when he stated it was unlikely she was born a Jew.[53] However, the abundance of texts proclaiming Queen Zenobia’s Jewish identity and/or conversion does indeed imply there is truth to this matter, although it is unclear whether she fully converted, or dabbled and adopted only some aspects of the religion into her life. Furthermore, it is likely that Photios’ ancient source mentioning her penchant for Judaism, independently from any Christian figure including Paul of Samosata, inspired the previous Christian texts. In addition, this source may have been older and more accurate and may have been written in Zenobia’s lifetime.

Zenobia and the Rabbis

Despite the abundance of discussions on Queen Zenobia’s Jewish identity in Christian discourse, it is notable that a vital Jewish source does not infer or mention her Jewish identity: the Talmud.[54] In the discourse surrounding this matter, it is crucial to underscore the multifaceted landscape of Judaism during the 3rd century CE, emphasizing its rich diversity and dynamic manifestations, compared to modern-day Judaism. There were countless ancient Jewish sects,[55] where the most popular and incorrectly designated one was Hellenistic Judaism, which is a contentious term. However, the majority of Jews, who come from a diverse and culturally rich range of Jewish communities, fall under this category. Thus, it would be wise to suggest abandoning the term and simply referring to these individuals as Jews.[56] This gains further traction when considering the common use of the term Hellenistic Judaism as a derogatory term, which denotes it as a lesser, wrong or impure form of Judaism. The dawn of this problematic terminology progressed from anachronistic perspectives originating from modern Judaism, which is mainly composed of Orthodox schools of thought descended from the Rabbinic movement. The fact that the ancient Judaism of this silent majority died throughout the centuries does not justify relegating it to a status of inferiority.

While the complete substitution of “Judaism” for the term “Hellenistic Judaism” proves impractical due to entrenched terminology, the adoption of the term “Conventional Judaism” represents a pragmatic initial step towards rectifying this. Through a gradual evolution of terminology, the aim is to replace the divisive designation with the more encompassing and accurate labels of “Judaism” and “Jews” for this broader Jewish populace.

The Rabbis who wrote the Talmud had little influence outside Judaea/Palaestina and Babylon, i.e. modern-day Iraq, although their authority and status are debatable even in these two centres. The Rabbis and their followers suffered heavy losses during the Second Jewish Revolt in the 2nd century CE, and thus were fundamentally opposed to any attempts of rebellion against the Roman Empire. Since Queen Zenobia’s actions were essentially a revolt against the Empire, there was no incentive for the Rabbis to recognise or support her. Furthermore, the Rabbinic world was a profoundly patriarchal society and fiercely opposed the idea that pagans could convert to Judaism. If Zenobia was both a woman and a convert, the Rabbis would have seen her as an aberration, thus deeming her unsuited to lead the Jewish people.

This can be seen in several important debates regarding gentile conversion to Judaism, with strong opposition from the Rabbis towards the broad acceptance of converts into the Rabbinic Jewish world. Interestingly, various debates within the Babylonian Talmud deliberate the rationale behind the exclusion of converts hailing from Palmyra (Tarmod/Tadmor).[57] Of particular note is the unanimity among the Rabbis within the Talmudic literature consistently advocating for the rejection of converts from Palmyra. Moreover, the central Rabbi in this discussion, Rabbi Yohanan, is a contemporary of Odaenathus and Zenobia.

This underscores the substantial debate surrounding the acceptance of Jewish converts, and implies that many in Palmyra and its vicinity may have converted. It also provides credence to the assumption that the Rabbis did not refer to Zenobia’s conversion because they generally opposed conversions and proselytization. Furthermore, this discourse serves as compelling evidence attesting to the allure of ancient Judaism, and that at least part of the Jewish community in Palmyra espoused a proselytizing sect who advocated for Jewish conversion. The prevalence of Jewish converts in Palmyra, coupled with the acceptance or endorsement of such conversions by the city’s Jewish community, likely constitutes the incentive behind the recurring suspicion regarding the origins and Jewishness of Jews from Palmyra, thus categorising them as mamzerim (bastards). This may have also been the justification for Rabbi Yohanan’s argument and debate with his colleagues.[58] Additionally, it is evident that this Palmyrene faction did not adhere to Rabbinic authority, and was part of the world of Conventional Judaism (Hellenistic Judaism). The possibility exists that the theological tenets of some of these adherents evolved to something akin to Judeo-Christian beliefs in the 4th century CE,[59] which can be also seen in the 5th century CE Christian text “The Life of Alexander Akoimètos,”[60] which will be debated later. Similarly, Benjamin of Tudela’s account will shed light on this aspect of the community, and will also be discussed later.

Although the Jewish community in Palmyra adhered to practices and beliefs historically categorized as Judaism, their faith markedly contrasted with Rabbinic Judaism. Significant to this debate are the Talmudic references to Zenobia as they reinforce the assumption that Zenobia and her beliefs posed a tangible threat to the Rabbis and their world. The perceived imminent and cataclysmic danger posed by Queen Zenobia and the Jewish community in Palmyra likely fostered the general hatred perceived in the Talmud towards the city of Palmyra. This sentiment is reflected in passages expressing a desire for the city’s destruction under the pretext that its inhabitants assisted in the destruction of both Jewish Temples in Jerusalem:[61]

“R. Yohanan said: He who sees the destruction of Tarmod is happy, for it participated in the destruction of the First Temple and in the destruction of the Second Temple. At the destruction of the First Temple it supplied 80,000 archers and at the destruction of the Second Temple it also supplied 80,000 archers.”[62]

The rejoicing at the downfall of Palmyra, along with the association of its inhabitants with the destruction of the Jewish Temples, is principally credited to Rabbi Yohanan, a contemporary of Queen Zenobia. In addition, the claim regarding the Temples’ destruction at the hands of the Palmyrenes finds endorsement from several Rabbis, including contemporaries of Zenobia, such as Rabbi Huna and Rabbi Hanina. Such apprehension towards Palmyra, its Jewish community, and Zenobia, persisted to such an extent that hatred towards the city endured in Rabbinic debate for centuries thereafter.[63]

It is noteworthy to highlight that the sole debate in the Talmud which mentions Zenobia by name, and has received relatively little attention within academic discourse, pertains to the incarceration of certain Rabbis.[64] Millar referred to this text in only one sentence, “the Talmud has one anecdote of an appeal by Jewish elders to Zenobia, but the attitude expressed there is otherwise hostile.”[65] To clarify, the Talmudic legend explicitly opposes Zenobia throughout its entirety, contrasting with the general avoidance of her mention elsewhere in the Talmud. Instead, the Talmud focuses on expressing disdain towards converts from Palmyra and the city of Palmyra itself. Given that this legend is the only reference to Queen Zenobia within the Talmud, this anecdote serves as a singular lens into the hazardous nature of the Rabbis’ relationship with Queen Zenobia. This in turn serves to prompt a consideration of the origins and underlying motivations that shaped this negative disposition, rather than attributing this antagonistic attitude to an arbitrary source. To better understand this complex text, the second part will be discussed first:

“Zeir bar Ḥinena was captured at Safsufa. Rebbi Ammi and Rebbi Samuel went to negotiate for him. Queen Zenobia said to them, your Creator usually does wonders for you; put Him under pressure! There came a Saracen carrying a sabre. He said to them, with this sabre did Odenathus kill his brother. Zeïr bar Ḥinena was saved.”[66]

It is evident from this account that Zenobia arrested Zeir bar Ḥinena, who came from the Rabbinic world. Thus, two Rabbis went to appeal for his release. This is not a mere “[…] story of an appeal by Jewish elders to the Palmyrene queen.”[67] as Kaizer mentioned in a footnote, but rather the depiction of a considerable ideological gap.[68] The two paradoxical accounts of Zenobia’s relationship with the Jews are strong evidence of this. On the one hand, non-Jewish texts accentuate Zenobia’s good relationship with the Jewish people, while on the other hand, the only Jewish source, belonging to Rabbinic circles, claims otherwise. To reconcile this contradiction, it is safe to assume that Zenobia favoured Conventional Judaism, and not Rabbinic Judaism. This assumption is strengthened by the fact that Zeir bar Ḥinena was most probably not the only person from the Rabbinical sphere to be arrested by Zenobia:

“Rebbi Issi was captured in Safsufa. Rebbi Jonathan said, may the dead be wrapped in his shroud. Rebbi Simeon ben Laqish said, even if I should kill or be killed, I shall go and save him by force. He went and negotiated; they handed him over to him. He said to them, come to our old man, he shall pray for you. They came to Rebbi Joḥanan. He said to them, what was in your mind to do to him shall be done to these people. They did not reach Epipshrus (אפיפסרוס) when all of them were gone.”[69]

Another Rabbi, Rebbi Issi, was also captured in Safsufa. Although it does not clearly state that Zenobia’s forces arrested him, the second paragraph, which was discussed first in this article, shows this was the same place where Zeir bar Ḥinena was arrested. While both were eventually released, the circumstances and conditions surrounding this remain obscure. Furthermore, the Talmud refrains from mentioning the reasons for their arrests in both tales,[70] thus implying the reason was their beliefs or views. The narrative of the release of Zeir bar Ḥinena is especially peculiar, given the apparent absence of details on his release, which could imply a deliberate act of censorship. This, coupled with this singular reference to Zenobia within the Talmudic corpus, underscores the noticeable schism between her and the Rabbis. Moreover, the conspicuous omission of any discourse regarding Zenobia’s conversion to Judaism, or her Jewish faith, within Talmudic literature aligns with the Rabbis’ stance against conversion and proselytization, thus representing not an anomaly but rather a predictable outcome.

Despite this unfavourable account from the Talmud, there is further evidence to suggest that Zenobia had amicable relations with most Jewish communities and sects. For instance, in certain non-Rabbinic Jewish texts, her husband Odaenathus is depicted as a lion sent from the sun, who destroyed rebellions against Rome and defeated Persia, with an ultimate destiny to rule over Rome.[71] This portrayal suggests unequivocal support for Odaenathus from many Jewish communities, even if he attempted to become the Roman Emperor. Consequently, such support likely extended to Queen Zenobia and their younger son following the death of Odaenathus and their elder son. This may be supported by a mosaic found in one of the Jewish prayer halls/synagogues found in Palmyra.[72] Another such evidence is a bilingual Greek and Latin inscription from Egypt that confirms an old Ptolemaic grant of asylum to a synagogue:[73]

βασιλίσσης καὶ βασι|λέως προσταξάντων | ἀντὶ τῆς προανακει|μένης περὶ τῆς ἀναθέσε|ως τῆς προσευχῆς πλα| |κὸς ἡ ὑπογεγραμμένη | ἐπιγραφήτω· [uacat] | βασιλεὺς Πτολεμαῖος Εὐ|εργέτης τὴν προσευχὴν ἄσυλον. | Regina et | | rex iusser(un)t.[74]

“On the orders of the queen and king, in place of the previous plaque about the dedication of the proseuche let what is written below be written up. King Ptolemy Euergetes (proclaimed) the proseuche inviolate. The queen and king gave the order.”[75]

This inscription has been prominently referenced in scholarly discourse pertaining to the connection between Zenobia, Judaism and Christianity. However, during such debates, it was raised that rights of asylum were uncommon in the 3rd century CE. Therefore, it was conjectured that the individuals responsible for reaffirming such privileges were more probably “Cleopatra VII and her brother Ptolemy XIV (47–44 BCE) or her son Ptolemy XV (Caesarion).”[76] Consequently, prudence is warranted when utilising this inscription in the debate.

Nevertheless, certain conclusions can be reached even if this inscription was not included in the debate. It is conceivable to posit that both Queen Zenobia and Palmyra’s Jewish community in the 3rd century CE epitomised a manifestation of Conventional Judaism. The Rabbinical establishment would likely be apprehensive of a hypothetical scenario involving the establishment of a Palmyrene Empire led by Queen Zenobia. They possibly foresaw her potential to encourage the flourishing of a Judaism characterised by cosmopolitanism and inclusivity. Furthermore, had she triumphed over the formidable Roman Empire, such an outcome could have been interpreted as divinely endorsed. This in turn would have further exacerbated the concerns of the rabbinical leadership regarding the erosion of their traditional influence and authority, an outcome she may have already attempted to create according to the only relevant Talmudic legend. Therefore, the purported omission of Queen Zenobia and her conversion to Judaism from Talmudic narratives can be construed as consistent with the ideological stance of the Rabbinical tradition.

Why Judaism?

While the principal contention challenging Queen Zenobia’s Jewish inclinations is readily disproved, it is necessary to question the motivations underlying the potential contemplation of conversion to Judaism by an individual of her eminence and stature. It is important to highlight that Queen Zenobia’s purported conversion to Judaism does not stand as a singular instance of royal conversion to Judaism within the annals of history. For example, Queen Helena of Adiabene converted to Judaism in the 1st century CE.[77] Similarly, King Abikarib As‘ad of Himyar (r. c 383–433 CE),[78] his dynasty, many subsequent rulers, and substantial segments of the aristocracy of the Himyarite Kingdom converted and remained ardent Jews until the demise of their kingdom at the hands of the Aksumites in 525–531 CE.[79] The final recorded conversion of a pagan royal family, accompanied by substantial segments of their aristocracy, occurred in the Khazar Kingdom in the 9th or 10th century CE.[80] Furthermore, there was an intriguing phenomenon where numerous aristocratic women from Rome adopted Jewish customs in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE.[81] Consequently, Judaism merits recognition as a dominant, pervasive and appealing religion at least until the 6th century CE, and even later.

The partiality to Judaism amongst women appears to have been more pronounced than among men, a trend paralleled in the successful efforts of Christianity,[82] an offshoot of Judaism, to attract female adherents.[83] Moreover, Zenobia consolidated her leadership amidst conflicts with both the Persians and the Romans,[84] while lacking in Palmyrene forces who were too few to defend her territories against the dual threats. Conjecture suggests these forces may have been too limited even to deter Arab incursions. Thus, she reverted to diplomacy, fostering benevolence and goodwill in a bid to acquire and mobilise pro-Palmyrene sentiments within the cities she controlled and beyond.[85]

Who were the men Zenobia sought to persuade to join her army and endeavoured to gain their support to realise her imperial ambitions? It is plausible that she recruited from among the local populace, a practice akin to that of Roman garrisons. Notably, in regions such as Palmyra and the broader Eastern Mediterranean, there were numerous adherents of monotheistic religions. The expansion of monotheistic ideologies encompassed not only the dissemination of Judaism,[86] and Christianity,[87] but also their influence on other beliefs, notably evident in the prevalence of the so-called ‘anonymous god’ which enjoyed significant popularity in Palmyra.[88] The belief in the ‘anonymous god’ did not necessarily refer to one god,[89] although it utilised numerous terminologies and blessings attributed to Judaism and Christianity, such as: “Lord of the Universe”, and “Merciful” in Palmyra; “Our Lord, Our Lady and the Son of Our Lords” in Hatra and finally “Lord of the Gods” in Edessa.[90]

The praising in Palmyra – “He whose name is blessed forever” (bryk šmh lʿlmʾ), “Lord of the Universe” (mr ʿlmʾ), “Merciful” (rḥmnʾ) – is in a more monotheistic vein, possibly suggesting a greater Jewish influence.[91] On the other hand, the inscriptions in Hatra refer “to the city triad called in the local dialect of Aramaic: ‘Our Lord’ – Maren (mrn), ‘Our Lady’ – Marten (mrtn), ‘Son of Our Lords’ – Bar-Marin (brmryn),”[92] implying a greater Christian influence in the region, although this is a gross simplification of the process and terminology. Nevertheless, certain terms were employed in conjunction with names of different deities across different centuries, prompting suggestions that some of these terms were known and adopted from other cultures.[93] However, many of these cultures disappeared centuries before Rome annexed the Eastern Mediterranean. Thus, the greater use of the anonymised form, as well as the choice of terms like “merciful,” can indicate a Jewish or Christian influence in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE that was gradually absorbed into the neighbouring cultures as they evolved during this period. This process may have been shaped by individuals who practised syncretism, moving between faiths without full conversion or commitment.

Therefore, according to this line of argument, the terminology implies that there was greater Jewish influence in Palmyra, while in Hatra there was more Christian influence. Unfortunately, this hypothesis remains speculative due to limited evidence. However, a thorough examination of references to the “anonymous god(s)” and a refined typology could enhance understanding of changes over time. This analysis may reveal shifts in the deity’s anonymity and alterations in associated terminology, shedding light on potential influences.

The hypothesis linking the ‘anonymous god’ cult in Palmyra to Judaism gains support from its earliest attestations in the first decades of the 2nd century CE.[94] The Diaspora Revolt and the Second Jewish Revolt occurred in the early 2nd century CE, leading to significant Jewish refugee influx from Cyrenaica, Cyprus, Judaea, and Egypt, potentially resulting in many settling in Syria, possibly with a special concentration in Palmyra. This displacement facilitated the dissemination of Jewish ideas and culture across the Empire, likely contributing to heightened interest in the religion. Moreover, out of the said connections regarding the worship of the ‘anonymous god’, associating the shift of the terminology in Palmyra to Judaism receives substantial support when compared with the birth of the worship of a “one God” called the “Merciful” (rḥmnʾ) in South Arabia, especially Himyar, from the early 4th century CE, due to Jewish presence and influence. The said influence and growing belief in the “One God” drove the King of Himyar, Abikarib As‘ad (c 383–433 CE), to convert to Judaism.[95] The shift in South Arabia is not normally discussed in relation to Palmyra. Nevertheless, such a case in an entirely different location is an excellent example of Jewish influence on the local groups in the area, especially Arab groups, who absorbed changes similar to those seen in Palmyra, eventually leading their local rulers to convert to Judaism. However, the similarity in terms is great, and the time and cultural correlations between the two ethnic groups are immense. This implies that these two separate phenomena may be connected and not so isolated. There is always the possibility that the change in South Arabia from the beginning of the 4th century CE was also driven by Jews, and/or believers of the anonymous god who were influenced by Jews, who may have immigrated to Arabia from Palmyra after the fall of Zenobia in 272 CE.

Further Evidence for the Jews of Palmyra

According to the archaeological record, Palmyra’s Jewish community endured at least from the Principate until Late Antiquity. Remarkably, the extent of evidence for this community from the Roman period surpasses that of any other Jewish Diaspora community, except for the community of the city of Rome. This exceptional abundance of evidence, particularly notable compared to other Syrian cities, is exemplified by the presence of remains from three distinct buildings in Palmyra which potentially held Jewish religious affairs, and may have also functioned simultaneously. The most renowned of these structures, recently designated as the Mezuzah Building by Cussini,[96] comprises only the surviving doorway that indicates its former grandeur. The presence of Deuteronomy quotes on the doorway,[97] led to its classification as the Mezuzah Building, akin to the textual content typically found in a mezuzah, that Jews traditionally affix to the doorpost of their homes. However, scholarly debate persists regarding its precise function, with some proposing it served as the doorway to a synagogue.[98] Conversely, some scholars, noting the absence of donor inscriptions typical in many synagogues, proposed that the structure served as the entrance to a mansion belonging to a wealthy Jewish family.[99] Regardless of its function, the building serves as compelling evidence of Jewish presence in Palmyra, underscoring the community’s wealth and significance in the city.

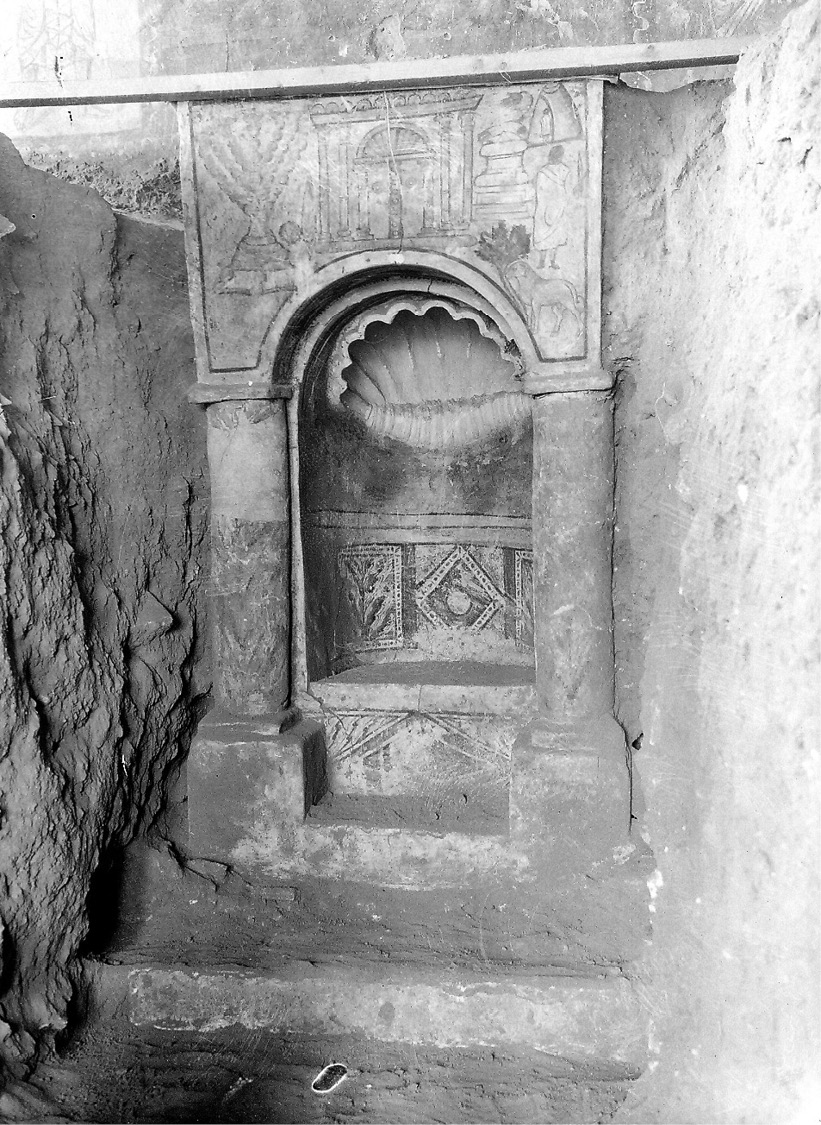

Another important Jewish structure in the city is the synagogue discovered beneath the later Christian Basilica I (fig. 1). Unlike the Mezuzah Building, which is tentatively dated to the 3rd or 4th century due to the sole surviving doorway, the synagogue is securely dated to the 3rd century CE, during the reigns of Odaenathus and Zenobia. Alternatively, the primary challenge with this evidence lies in the incomplete or absent publication of the synagogue, a recurring issue with many Jewish discoveries in the city. From the scanty publications, it is possible to glean certain details about the synagogue, including its identification as such,[100] and its size (22m by 13m).[101] Furthermore, unlike the uncertain dating of the mezuzah doorway, the strata containing the synagogue dates to the 2nd to 3rd century CE, corresponding with the reign of Odaenathus and Zenobia. However, it is possible that both structures existed and functioned during this period.

The third structure with potential Jewish religious significance in Palmyra is situated directly next to the synagogue’s wall. Dubbed the Rue des Églises house (N1–N2), this building has sparked debate due to the discovery of a mosaic in one of its rooms (fig. 2). The focal point of contention is a triclinium within the structure, boasting an impressive mosaic floor dated to the mid-3rd century CE, concurrent with the synagogue’s era. The mosaic has two central panels (fig. 3). One depicts an armed man riding a winged horse while piercing a chimaera with a spear, which was suggested as a parallel to the myth of Bellerophon slaying the chimera (fig. 4). The second is of a tiger hunt, with a rider firing an arrow from his bow toward a tiger that was already pierced by another arrow, with a second tiger portrayed in the panel directly under the mounted archer. Occasionally, the panels are interpreted as Odaenathus’ triumph. Additionally, the mounted archer hunt scene has an inscription in cursive Palmyrene script, written between the bow and its string saying: “Diodotos has made this mosaic, himself and his sons.” (fig. 5) It was suggested that instead of Diodotos, the inscription may have originally contained Odaenathus’ or one of his son’s name, which was subsequently altered to a different name. However, the proposal that the inscription was altered to the name of the mosaicist is tenuous,[102] as it seems unlikely for an artist to sign adjacent to the central figure. This implies the original inscription represents the given name of the original donor, while the name in the amended inscription, if it indeed was changed from the original, represents the name of the donor that paid for the alteration of the room and mosaic. However, if the mosaic was indeed meant to originally represent Odaenathus and one of his sons, and the inscription was to that effect, then the changes in the inscription more probably date to after Zenobia’s defeat. In such a case, the new name does not necessarily represent anyone who donated a refurbishment, but rather an attempt to erase the connection to Zenobia. Roman rule saw such connections as unfavourable, and the name Diodotos is merely the name of a prominent member of the community. Nevertheless, it is possible that the original inscription before the alterations referred to the donor and his sons. Thus, the question remains: does the mosaic depict the donor and one of his sons, or Odaenathus and one of his sons, or whether they are one and the same, and Odaenathus himself donated the mosaic?

The entrance to the building that housed Basilica I, which was previously used as a synagogue (the photo is courtesy of Aleksandra Kubiak-Schneider).

The room with the mosaic in the Rue des Églises house (N1–N2). The picture was taken to the direction of Jerusalem, i.e. south-south-west (the photo is courtesy of Michał Gawlikowski).

In addition, the mosaic features Jewish religious motifs, including a menorah and two pairs of open hands, located on panels adjacent to the main mosaic and facing towards Jerusalem.[103] Gawlikowski proposed that these areas with Jewish symbols were added shortly after the original mosaic was laid,[104] indicating a shift in the room’s function to serve as a prayer hall.[105] However, given that the two mosaics were installed nearly simultaneously, it is inappropriate to categorise them as distinct phases of the same room. Additionally, it is not possible to definitively assert that the room was not under the ownership of the Jewish community during the initial mosaic installation. This suggests two potential scenarios. Either the room initially served as a dining hall or meeting space for the Jewish community and was later repurposed as a prayer hall/synagogue, or it functioned as a prayer hall/synagogue from its inception, even before the addition of the second mosaic. Accordingly, if Gawlikowski’s interpretation is accurate and the mosaic indeed portrays Odaenathus and one of his sons, it would highlight the remarkable and unparalleled link between Odaenathus, Zenobia, and their lineage to the Jewish community of Palmyra, especially as the mosaic was possibly donated by Odaenathus himself. However, in the case that the mosaic depicts a different donor and his sons, the fact that the donor wanted both to be depicted as armed riders raises the possibility that the donor and his son were military men. They may have been high-ranking officers or generals in Odaenathus’ army, as only soldiers of such rank would be wealthy and prominent enough to donate such a magnificent mosaic, and maybe even the entire room. Accordingly, both options show the relationship between Odaenathus’ army and the Jewish community. This association can explain the Christian assertion of Zenobia’s extensive connections to the Jewish community and the possibility of her conversion to Judaism, thereby lending credence to the historical plausibility of such an occurrence. Moreover, it aligns with the importance that the Jewish community had in the city, as all these three buildings possibly acted as synagogues concurrently in the 3rd century CE during Queen Zenobia’s reign. In this context, it is pertinent to note the discovery of five lamps adorned with a menorah motif within the cellar of the Allat temple.[106] Additionally, a hoard of bronze coins, potentially dating to the late 4th century, was unearthed in the same room, but it is not clear if they were deposited together, and if the date of the lamps is contemporaneous with the date of the coins or earlier than the coins.[107]

The main part of the Rue des Églises house (N1–N2) mosaic, which was sometimes referred to as “Odaenathus’s victories”, with the two panels, one of the Bellerophon scene and the other of the hunting scene in the middle (the photo is courtesy of Michał Gawlikowski).

A closeup of the panel of Bellerophon slaying the chimaera (the photo is courtesy of Michał Gawlikowski).

Closeup of the panel depicting the tiger hunt with the inscription “Diodotos has made this mosaic, himself and his sons” (the picture is courtesy of Michał Gawlikowski).

As previously noted, the Jewish community of Palmyra embraced conversions, potentially even encouraging them. Apart from the Rabbinic discussions highlighted earlier, concerning converts from Palmyra, numerous other debates and cases address this issue. One particularly perplexing and intricate case revolves around the husband of Rachel, daughter of Samuel/Shmuel. Samuel of Nehardea, also known as Samuel bar Abba, was a renowned Babylonian Rabbi of the first generation of Amoraim who served as the leader of the Jewish community of Nehardea (ancient city of Anbar, located near modern-day Fallujah, Iraq). He had two daughters, both of whom were captured during the city’s conquest by Odaenathus or one of his generals.[108] One of his daughters, Rachel, was assaulted and bore a son, later known as Rav Mari.[109] According to legend, his father, Issur the convert, likely the Palmyrene soldier who abducted his mother,[110] Rachel, was not Jewish at the time of conception but was Jewish at his birth, i.e. converted to Judaism during her pregnancy.[111] This account is noteworthy as it not only highlights the widespread conversion of Palmyrenes, but also emphasises that this occurred within the ranks of their military forces, the same forces that empowered Odaenathus, and later Zenobia, and her subsequent attempt to seize the Roman East, or more.

The evidence for Jewish presence in Palmyra extends beyond religious edifices and texts to include numerous inscriptions left by Palmyrene Jews. Epigraphic records of Jewish presence in Palmyra are categorised into two groups: those originating from the city and those from Judaea/Palaestina. However, distinguishing between Jewish adherents and followers of the One God in Palmyra poses a significant challenge, particularly given the prevalent influence of Judaism on the belief in the One God within the city, as demonstrated earlier.

Eleonora Cussini, the editor of the Palmyrene Aramaic Texts, identified several inscriptions from Palmyra with distinctively Jewish characteristics in a recent publication.[112] Among them, three inscriptions originate from small incense altars, while three others are associated with funerary contexts. Notably, the inscriptions from the altars, inscribed in Palmyrene Aramaic, include PAT 0446, PAT 1911 (dated to 251 CE), and PAT 0393 (dated to 256 CE). Additionally, one of the texts from a funerary setting is a tomb sale document, inscribed in Greek and catalogued as Inv. VIII, 68. Another is a Greek and Palmyrene bilingual foundation inscription dated to 212 CE, that is known in scholarly research by various names, including PAT 0057.[113] The final funerary inscription, PAT 2729, dating to 243 CE documents the purchase of a portion of a tomb by three Jewish brothers. This inscription exemplifies a significant challenge in the study of Ancient Judaism. Typically, Jewish or Yahwistic theophoric names are often the sole means of identifying individuals as Jewish. However, many Jews bore more general Semitic, Hellenistic, or Romanised names. In this inscription, the challenge persists. While one brother, Isḥaq, and the father, Yaʿkob, possess unmistakably Jewish names, the other brothers, Aurelius Shumʿon and Mezabbana, do not. Similarly, in the five previously mentioned inscriptions, Jewish identification was primarily established through names or genealogical lineage. Nonetheless, these are not the sole inscriptions that relate to the Jewish community of Palmyra in such a manner. For example, the name Yaʿkob (yʿqwb) in PAT 2615 can also be identified as Jewish, as well as Bani Shimʿon in PAT 2085 and 2134. This survey and analysis of names are partial, and so we must hope for a more comprehensive examination in Cussini’s forthcoming article.[114] Furthermore, it is interesting that all the securely dated inscriptions linked to Judaism, discussed herein, originate from the 3rd century CE, predominantly from the mid-century, coinciding with King Odaenathus’ reign.

Additionally, three Palmyrene Aramaic dedications on altars, PAT 0446, PAT 1911, and PAT 0393, demonstrate familiarity with the book of Psalms, providing further evidence for Jewish presence in the city and its influence, which likely inspired the distinct form of worship to the anonymous god. Of these dedications, the two securely dated ones, PAT 1911 from 251 CE and PAT 0393 from 256 CE, originate from the mid-third century, coinciding with Odaenathus’ reign.[115] This is similar to much of the evidence already presented, thus highlighting the prevalence and significance of Judaism in the region, particularly in Palmyra at the time. This elucidates why individuals seeking power would consider aligning themselves with the Jewish community.

With regards to evidence outside of Palmyra, the prevalence of Palmyrene Jews in the funerary record of Judaea/Palaestina serves as evidence of the widespread significance and influence of the Palmyrene Jewish community, underscoring its wealth and prominence in the region. For instance, the inscription CIIP II 1119, found on an ossuary in Jerusalem, commemorates a woman named Ima, identified as the mother of “Ḥanana … the ḥazan of the synagogue of Palmyra.” Moreover, there are inscriptions in Palmyrene Aramaic discovered in the vicinity of Jerusalem. For example, CIIP I 79, alongside several others, like CIIP I 421, CIIP I 430, and CIIP I 439, were uncovered in a burial cave near Naḥal Atarot, situated north of the Shu‘afat neighbourhood. Notably, this burial cave neighboured the resting place of Helena of Adiabene, a foreign queen who converted to Judaism. Additionally, CIIP II 1120 from the region features Palmyrene script.

Furthermore, some inscriptions from Jerusalem, such as CIIP I 492, CIIP I 508, and possibly CIIP I 105, contain names thought to be Palmyrene in origin. Typically, these inscriptions from Jerusalem are dated to the 1st century BCE or 1st century CE. However, Jerusalem is not the sole significant burial site yielding Palmyrene inscriptions in Judaea/Palestina. Beit She’arim in the Galilee, a famous Jewish city known for its extensive necropolis, also boasts a wealth of inscriptions from the 2nd to the 4th centuries CE which indicate the burial of Palmyrene Jews in the area.[116] For example, Halls C, E, K and G in Catacomb 1 include the inscriptions CIIP V.2 6944 (in Palmyrene, possibly referring to the same person in the Greek inscription CIIP V.2 6942–6943 in the same catacomb), CIIP V.2 6948 (Palmyrene script), CIIP V.2 6949 (Palmyrene script), CIIP V.2 6960 (Greek inscription with Palmyrene name), CIIP V.2 7005, CIIP V.2 7011 (Palmyrene script) and CIIP V.2 7018 (script influenced by Palmyrene script). Catacomb 3 contains four additional inscriptions written in Palmyrene script (CIIP V.2 7038, CIIP V.2 7041–7043), while Catacomb 4 contains Palmyrene names (for example CIIP V.2 7046 and 7053). One notable inscription, CIIP V.2 7053, is particularly significant due to a graffito suggesting that the deceased, Germanus, may have been a soldier, a topic to be explored extensively later. Equally noteworthy, alongside the numerous inscriptions, is the legend in the Mishnah and the Talmud referring to Miriam of Tarmod (of Palmyra).[117]

Further strong evidence for the significant presence of Judaism in the city, as well as the uniqueness of the community and their proselytism, can be found in a different source from Late Antiquity “The Life of Alexander Akoimètos” (the sleepless), a 5th century Christian text:

Ὁ δὲ μακάριος παρελθὼν πᾶσαν τὴν ἔρημον μετὰ τῶν ἀδελφῶν ἀδιαλείπτως ψαλλόντων ἦλθον εἰς τὴν πόλιν Σολομῶντος τὴν ὀνομαζομένην εἰς τὴν βίβλον τῶν βασιλειῶν, ἣν ἔκτισεν εἰς τὴν ἔρημον, τὴν λεγομένην Πάλμυραν. οἱ δὲ πολῖται, τὸ πλῆθος τῶν ἀδελφῶν θεασάμενοι μήκοθεν, καὶ ὄντες μὲν Ἰουδαῖοι ὀνομαζόμενοι Χριστιανοί, πλησιασάντων αὐτῶν, τὰς πύλας τῆς πόλεως ἀπέκλεισαν, πρὸς ἀλλήλους λέγοντες· Τίς ὅλους τούτους δύναται θρέψαι; ἐὰν οὗτοι εἰς τὴν πόλιν ἡμῶν εἰσέλθωσι, λιμώττομεν πάντες. ὁ δὲ ἅγιος θεασάμενος ταῦτα, ἐδόξασε τὸν θεὸν λέγων· Ἀγαθὸν πεποιθέναι ἐπὶ κύριον ἢ πεποιθέναι ἐπ‘ ἄνθρωπον. θαρσεῖτε, ἀδελφοί, ὅτι ὅθεν ού προσδοκῶμεν ἐπισκέπτεται ἡμᾶς ὁ κύριος. οἱ δὲ βάρβαροι οἱ ὄντες ἐν τοῖς τόποις ἐκείνοις παρεῖχον αὐτοῖς οὐ τὴν τυχοῦσαν φιλανθρωπίαν. τριῶν δὲ ἡμερῶν εἰς τὴν ἔρημον διαγόντων αὐτῶν, ἐξαπέστειλεν ὁ θεὸς κατὰ τὸν λόγον τοῦ ἁγίου καμηλαρίους ἀπὸ τεσσάρων μονῶν ὄντας τῆς πόλεως φέροντας πάντας τὰ ἀγαθά. καὶ δεξάμενοι καὶ εὐχαριστήσαντες τῷ θεῷ, μετέλαβον καὶ αὐτοί· καὶ οὕτως περιέσσευσεν ὥστε καὶ δεξάμενοι ηὑρέθησαν αὐτοὶ παρέχοντες τοῖς πτωχοῖς τῆς πόλεως ἐκ τῶν ἀποσταλέντων αὐτοῖς.[118]

“The blessed one [i.e. Alexander] traversed the entire desert with his brothers ceaselessly singing their psalms. They came to the city of Solomon named in the Book of Kings, a city he built in the desert called Palmyra. When its citizens observed from afar the multitude of brothers drawing near (and since they were, in fact, Jews, although they called themselves Christians), they shut tight the city gates and said to one another, ‘Who can feed all these men? If they enter our city, we will all starve!’ When the holy man observed this he glorified God by saying, ‘It is better to trust in God than to trust in men. Take heart, brothers, that the Lord will visit us when we least expect it.’ Then the barbarians who lived in those parts showed them unusual compassion. They had spent three days in the desert when, as the holy man had said, God sent them camel drivers who lived four staging posts’ distance from the city, all bearing supplies. These they received and shared after giving thanks to God. There was so much in abundance that even after receiving their own portions they found themselves providing the city’s poor with the things sent to them.”[119]

In this 5th century text, the residents of Palmyra are called ‘Jews who call themselves Christians.’ Intagliata, like other scholars, believes that: “the term ‘Jews’ probably intended as an insult rather than a reflection of the religious condition of the inhabitants.”[120] This assertion is plausible, considering the hostility Alexander Akoimètos and his adherents likely harboured toward the people of Palmyra, due to their refusal to open the gates and their lack of benevolence toward them.[121]

Alternatively, another possibility is that the choice of this derogative term carries a deeper and unique meaning laden with historical connotations. Kaizer suggested it may reflect a continuation of the population of the city from Queen Zenobia’s reign to the early 5th century.[122] However, a few other suggestions must be raised. One hypothesis posits that the adoption of this derogatory term stems from narratives surrounding Zenobia’s purported Jewish heritage, thus indicating a prevailing sentiment toward the city’s populace that potentially included a substantial Jewish community, alongside a distinctive form of Christianity dominant in the region. This in turn may have been the reason why Paul of Samosata had a good relationship with Zenobia and a place in her court. Furthermore, it is possible there was a Jewish-Christian community, i.e. Jews who saw Jesus as either a prophet or the messiah, who were distinct or part of the Jewish community of Palmyra. Another possibility is that the term was not chosen derogatorily due to past stigma or reality, but rather because it aptly characterised the predominant religious factions in the city: a significant Jewish community, a Jewish-Christian community, and potentially a sizable Christian community with beliefs diverging from mainstream Christianity, that Alexander Akoimètos perceived as being more aligned with Judaism than Christianity. Accordingly, this text can be regarded as a corroboratory testimony for the strong Jewish presence and influence in Palmyra in late antiquity, especially in the 3rd and 4th centuries.

However, the debate regarding the Jewish community in Palmyra, its size, its influence and its importance in the Palmyrene military ranks in the 3rd century will not be complete without mentioning Benjamin of Tudela’s much later account. In the 12th century, he described the Jewish community of Palmyra, which he claimed to have visited, as follows:

“And in Tarmod there are about 2,000 Jews. They are valiant in war and fight with the Christians and with the Arabs, which latter are under the dominion of Nur-ed-din the king, and they help their neighbours the Ishmaelites. At their head are R. Isaac Hajvani, R. Nathan, and R. Uziel.”[123]

This Jewish population was suggested to have been the descendants of the Jewish community who resided in the city during Late Antique and Early Islamic times.[124] The text above implies that the city’s Jewish community exhibited distinct characteristics compared to the many other rabbinic communities of the 12th century. This is theoretically indicative of their potential uniqueness also in earlier centuries. However, the discussion regarding this text cannot simply be concluded as such. As Gawlikowski, the excavator of Palmyra, stated in his book, there is no evidence of the existence of a city; it was just a fortress at the time.[125] Hence, the account cannot represent the Jews of Palmyra in the 12th century, and so it necessitates looking differently at the text in the context of the current debate. When doing so, there are three possibilities. Firstly, Benjamin of Tudela’s tale is not about Palmyra but about Syrian Jews of his period, thus indicating that the Jews of Syria remained different when compared to other Jewish communities. This includes how some of them served their Muslim lords and masters even militarily. This in turn possibly reflects earlier periods. The second option is that Benjamin of Tudela’s story is an adaptation of a tradition or an account from antiquity describing the Jewish community in the city, who were significant in number and served the city’s masters militarily. The original account most probably referred to Zenobia’s reign, as this time period fits well with the content of this passage. In such a case, the Christians and the Arabs, that the Jews of Palmyra are mentioned to be fighting, were the Romans and the Persians in the original account. Similarly, “their neighbours the Ishmaelites” they are fighting alongside/for were originally their Palmyrene neighbours and their liege Zenobia. It is even possible the term “Ishmaelites” was kept from the original ancient source, as the residents of Palmyra were in modern terms Arabs,[126] and so in certain Jewish traditions “Ishmaelites.” I believe this option should be preferred, although a third one, a combination of the previous two, is also very probable.

Evidently, there is ample evidence for the uniqueness, size and importance (including in military terms) of the Jewish community of Palmyra in Zenobia’s time. Furthermore, Jewish communities existed in neighbouring regions like Dura-Europos, where an exceptional synagogue was excavated. Additionally, the abundance of Judaean coins discovered in excavations of the city corroborates the existence of a robust Jewish presence in Dura-Europos, suggesting many Jews settled there following the First Jewish Revolt of 66–74 CE.[127]

Jewish Presence in the Roman Army in the Third Century

To understand the manpower Queen Zenobia needed to enlist outside of her city, it is essential to examine the cultural composition of the Roman army. Firstly, Roman garrisons frequently recruited from the local population, making their ethnic composition reflective of the region.[128] Secondly, and most importantly, Queen Zenobia did her utmost to persuade Roman military units to her side and was frequently successful. As a result, her army included Roman troops. Given this article’s focus on monotheism and Zenobia’s attitude and possible conversion to Judaism, it is vital to assess Jewish presence within the Roman army. The presence of Jews in the Roman army is often considered scarce,[129] with claims that these soldiers were impious or not considered “good Jews.”[130] However, recent research disproves these assumptions.[131]

This is emphasised in Dio Cassius’ Historia Romana, a composition he worked on in the first three decades of the 3rd century CE, where he presents a version of a speech delivered by Marcus Aurelius to his men before marching east to confront the rebelling Avidius Cassius in 175 CE.[132] The Emperor said the next about Cassius’ Eastern Roman army:

ἄλλως τε, εἰ καὶ ἐκεῖνος ἐκ τῶν πρὸς Πάρθους πραχθέντων εὐδόκιμός ἐστιν, ἔχετε καὶ ὑμεῖς Οὐῆρον, ὃς οὐδὲν ἧττον ἀλλὰ καὶ μᾶλλον αὐτοῦ καὶ ἐνίκησε πλεῖστα2 καὶ κατεκτήσατο. ἀλλὰ τάχα μὲν καὶ ἤδη μετανενόηκε, ζῶντά με μεμαθηκώς· οὐ γάρ που καὶ ἄλλως ἢ ὡς τετελευτηκότος μου τοῦτ᾿ ἐποίησεν. ἂν δὲ καὶ ἐπὶ πλεῖον ἀντίσχῃ, ἀλλ᾿ ὅταν γε καὶ προσιόντας ἡμᾶς πύθηται, πάντως γνωσιμαχήσει, καὶ ὑμᾶς φοβηθεὶς καὶ ἐμὲ αἰδεσθείς.[133]

“You, at least, fellow-soldiers, ought to be of good cheer. For surely Cilicians, Syrians, Jews, and Egyptians have never proved superior to you and never will, even if they should muster as many tens of thousands more than you as they now muster fewer.”[134]

Marcus Aurelius sought to invigorate his men by mentioning that Avidius Cassius’ Eastern Roman army, the army they were about to confront, was weaker than the Western Roman legions under his command. If Dio’s account of the speech is accurate, there must have been a substantial Jewish presence in the Eastern Roman army. It is improbable for a military leader to risk lying to his troops in a manner easily disproven before a battle.[135] Moreover, lying to his soldiers would have been detrimental as Marcus Aurelius would have lost their trust and deceit would have undermined his objective in addressing his men.

Nevertheless, as it is reasonable to assume the account of this speech is not the original one, it is feasible that Dio, like other ancient authors, documented the speech as it was intended to be delivered.[136] This raises a few implications. First, Jewish military service must have been common during Dio’s lifetime, as he would not have highlighted their presence in his speech if they were not a significant component of the Eastern Roman army. Secondly, the presence of a sizable portion of Jewish soldiers in the army must have been widely recognised. As Marcus Aurelius had no incentive to deceive in his speech, Dio’s choice of words indicates there were a considerable number of Jewish soldiers in the Roman army, as he wrote the speech as it was intended to be delivered.

Further extensive evidence for Jewish military service can be found after general citizenship was granted to all free men of the Roman Empire by Emperor Caracalla in the year 212 CE in his Constitutio Antoniniana. This sudden abundance of evidence may stem from the growing number of Jews serving in the army. For example, the Historia Augusta records that soldiers erected a monument for Emperor Gordian the Third in the year 244 CE,[137] near the camp at Circesium, located on the border between the Roman and Persian Empires:[138]

Gordiano sepulchrum milites apud Circesium castrum fecerunt in finibus Persidis, titulum huius modi addentes et Graecis et Latinis et Persicis et Iudaicis et Aegyptiacis litteris, ut ab omnibus legeretur.[139]

“The soldiers built Gordian a tomb near the camp at Circesium, which is in the territory of Persia, and added an inscription to the following effect in Greek, Latin, Persian, Jewish, and Egyptian letters, so that all might read.”[140]

The inscription’s use of a writing system associated with the Jews on the monument indicates significant recognition and honour for the minority group, which in turn unequivocally highlights the substantial presence of Jews in military service.[141] However, the Historia Augusta is considered a less reliable source, with some claiming the author may have invented some of its content and sources.[142] Nevertheless, this does not detract from the importance of this source as evidence for considerable Jewish military service in the 3rd century CE, since even if the author fabricated some details, they would have had to rely on the established truths of their period. Thus, there is no sufficient reason for the author to write that one of the languages of a military dedication belonged to the Jews unless it was genuine, or at least feasible, as Jews served in large numbers during the 3rd century CE. This is also supported by mentioning “Egyptian letters” as the presence of Egyptians, like Jews, are well attested in the Roman army. Moreover, the inclusion of Egyptian writing is strong evidence that the writing in the mentioned inscription was meant to represent the languages of the soldiers who dedicated it, and not necessarily local languages to make the inscription comprehensible for passers-by and other audiences. This is because while Jews and Persians were local to the area, and not only serving in the Roman army, Egyptians were the latter and not the former. Therefore, it clearly indicates that the author of this part in the Historia Augusta was familiar with who formed the ranks of the eastern Roman army and thus referred to them. Despite coming from a less-than-reliable source, this extract is genuine evidence for the realia of the day, mentioned unintentionally, and is one of the strongest pieces of evidence for the large presence of Jewish soldiers in the Roman army of the day.

One of the best places that is indicative of this extensive Jewish enlistment is Dura-Europos. This city was abandoned after its conquest in 256 CE by Shapur I, the King of Persia, who was the same ruler against whom Gordian III died fighting. The town’s Roman defenders fortified the city by filling the buildings near the walls with earth and rubble, thus protecting them from the enemy and from the ravages of time, exceptionally preserving the ancient structures abutting the walls. The Syrian desert sands subsequently covered this city, preserving it as it was during Odaenathus’ era. As a border town between the Roman and Persian Empires, the city had a considerable Roman military presence, with archaeological excavations discovering that the Roman military compound comprised a quarter to a third of the city.[143] Furthermore, numerous temples dedicated to various gods and faiths were excavated, including the synagogue,[144] often identified as building L 7 (fig. 6), which was located adjacent to the western wall of the city (fig. 7), two streets south of the military compound.

Dura-Europos’ general excavations plan (©Artem.G/Wikimedia commons).

Since a significant part of the population was the garrison, it was proposed that the synagogue functioned as a place of worship for Jewish soldiers.[145] The argument was further elaborated when the wall paintings inside the synagogue were discussed in an even more comprehensive way.[146] These paintings purportedly depict Biblical scenes, with some figures anachronistically dressed in Roman military uniforms and equipment from the 3rd century CE (fig. 8–11). One suggestion for this phenomenon is that members of the Jewish community, or the painter himself, served in the military.[147] Another possibility is the painter depicted Roman soldiers because they were a visible part of daily life in Dura-Europos. Yet, the proximity of the synagogue to the garrison suggests Jewish Roman soldiers, military suppliers and passing merchants (given the city’s location along the ancient Silk Road) likely attended religious services in the synagogue.

Isometric view of Block L 7, Dura-Europos, with the Synagogue in its centre (©Marsyas/Wikimedia commons).

Furthermore, the prevalence of depictions of military personnel at Dura-Europos, coupled with the proximity of the synagogue to the Roman garrison, implies a substantial proportion of the Jewish congregation was Jewish military men, serving among the units stationed in the town. This aspect is further reiterated in various military documents uncovered in this city.

Some of these documents, belonging to XX Palmyrenorum, a Roman military unit that originated from Palmyra and was stationed in Dura-Europos, contained many general Semitic names that were used by Jews. For example: Aurel(ius) Salmanes[148] Bannạẹi, [A]ụrel(ius) Bạṛnaeus, Aurel(ius)] Ḅ[a]ṛṣị[ms]us, Ṣalmeṣ Ṃạlchi, ṣalṃus An[ ̣],[149] Malcḥụ[s Z]eḅiḍa, Seleucu[s M]ạlchi, Ṃal[c]ḥus Ṃombog̣ei, Auṛẹ[l(ius)] Bạṛḅesomeniuṣ,[150] Goremis] Ịạḍei,[151] Iulius Salman, Thẹmarsas Salman, Zebidaṣ Ịạḍẹi.[152] However, these names are not necessarily Jewish. These names, while reminiscent of biblical Hebrew names, are universal Semitic names that could also be associated with pagan deities, a common occurrence in the region.[153] Another name found in the military records of Dura-Europos, Aurel(ius) Maesomas Aciba,[154] bears similarity to that of the renowned Rabbi Akiva,[155] though it may have also been used by gentiles. On the other hand, there are names more strongly associated with Jews that are often used as definitive evidence of Jewish faith, like Iaq]ubus,[156] and Ạ[u]ṛẹl(ius) Og[a]ṣ Haniṇa.[157]

![Fig. 8: Wall painting from the Dura-Europos synagogue’s Northern wall, showing the battle of Eben Ezer, right part of the depiction (Gillerman slides collection [Yale], Adapted by Marsyas, Wikimedia commons).](/document/doi/10.1515/klio-2024-0027/asset/graphic/j_klio-2024-0027_fig_008.jpg)

Wall painting from the Dura-Europos synagogue’s Northern wall, showing the battle of Eben Ezer, right part of the depiction (Gillerman slides collection [Yale], Adapted by Marsyas, Wikimedia commons).

![Fig. 9: Wall painting from the Dura-Europos synagogue’s Northern wall, showing the battle of Eben Ezer, left part of the depiction showing the Ark being taken (Gillerman slides collection [Yale], adapted by Marsyas, Wikimedia commons).](/document/doi/10.1515/klio-2024-0027/asset/graphic/j_klio-2024-0027_fig_009.jpg)

Wall painting from the Dura-Europos synagogue’s Northern wall, showing the battle of Eben Ezer, left part of the depiction showing the Ark being taken (Gillerman slides collection [Yale], adapted by Marsyas, Wikimedia commons).

Jews cross the Red Sea pursued by Pharoah. A fresco from the Dura-Europos synagogue (©Becklectic/Wikimedia commons).

Murder of the prophet, Zechariah ben Jehoiada, from the Dura-Europos synagogue (©Wikimedia commons).

The presence of Jewish soldiers in Dura-Europos is well substantiated, but assessing the size of the Jewish community is integral to gauge their influence in the region. For example, the synagogue’s renovation and expansion in 245 CE, doubling its capacity to accommodate 120 male worshippers, underscores the growing influence of the Jewish community in Dura-Europos. Yet, beyond the formal seating, additional space on the floor or possibly wooden chairs, along with the courtyard, allowed a larger congregation to attend services. Furthermore, the synagogue was a relatively new institution during this period and, likely, most Jews did not visit one. It also remains unknown whether there were other unidentified synagogues, and not all Jews were present in the city at every given moment. However, assuming several hundred Jewish adult men lived in the city, with a quarter to a third possibly serving as soldiers, similar to the percentage of soldiers out of the city’s general population, will imply that 10 % or more of the permanent garrison could have been Jewish, given the estimated garrison size of 1000–2000 soldiers in the late 2nd century CE.[158]

Despite the sizable Jewish population and military presence in Dura-Europos, it appears some of this community, especially the congregation of the infamous synagogue, diverged from the doctrines of the Rabbinic tradition. This divergence is particularly emphasised by the synagogue’s wall paintings, a practice forbidden by the Rabbis of Judaea/Palaestina. In addition, the synagogue in Dura-Europos notably featured a Torah book niche (fig. 12–13), a characteristic possibly originating from Syria and not appearing in Judaea/Palaestina until a century or more later. This suggestive transfer of architectural elements from Syria to Judaea/Palaestina indicates the extensive influence of Syrian Jewish communities. Additionally, the presence of both the niche and the murals underscores a divergence from Rabbinic authority among the Syrian Jews,[159] aligning more closely with Conventional Judaism. This variant of Judaism likely prevailed within Zenobia’s sphere of influence, including her court, as is evident from the banquet hall which was used, or transformed into, a Jewish prayer room/synagogue, while including a mosaic with a hunting scene and Bellerophon slaying the chimaera.