Abstract

Emotion in spoken communication is conveyed through a combination of verbal, vocal and facial resources among others. This paper adopts a Systemic Functional Linguistic perspective to explore the sounding potential of English to realise affectual meanings in storytelling performances. It presents a novel exploratory system network of non-segmental vocal qualities considered meaningful for the description of the phonological realisation of affectual meanings. This system of vocal qualities models semogenic vocal options using the tone unit as its root entry condition to show how the features selected by storytellers work together as contrastive bundles for the expression of affectual meanings in a corpus of eight storytelling performances of Cinderella. The results show the association between emotional meanings identified discourse semantically in terms of categories of affect and the phonological choices from the vocal qualities system interpreted as affectual vocal profiles. This paper also explores the need to include phonological descriptions in research dealing with emotion in spoken communication in inter-stratal relations between attitudinally uncharged lexicogrammatical choices and affectual vocal qualities in the Reaction phases of the storytelling performances. The paper finishes by proposing a provisional system network for inscription and invocation resources for affect in spoken language.

1 Introduction

The expression and interpretation of emotion is often considered a challenging feature of spoken communication and this difficulty is heightened in our growing multicultural contexts where English is used as an additional language (Brown 1990 [1977]; Dewaele and Moxsom-Turnbull 2020; Lorette and Dewaele 2019; Rintell 1984; Roach 2009; Unsworth and Mills 2020). This is the case mainly because emotion concepts are not a shared experience of humanity but a social and cultural construct (Barrett 2017; Bednarek 2008). The cultural relativity of the conceptualisation and expression of emotion foregrounds the importance of offering theoretically grounded descriptions and methodologically sound toolkits to describe this complex socially learnt phenomenon in research and scaffold its teaching and learning experience.

The relation between language and emotion has been explored from varied multi-semiotic perspectives (see e.g. Barrett 2017; Bednarek 2008; Mackenzie and Alba-Juez 2019; Pavlenko 2007 for detailed accounts). These multidisciplinary perspectives agree that emotion is conveyed and interpreted not only through wordings, but also through a diverse range of other semiotic resources such as vocal features, facial expression, gesture, and posture (Abercrombie 1968; Burns and Beier 1973; Mehrabian 1972; Ngo et al. 2022; Scherer and Ellgring 2007; Scherer et al. 1984; Wallbott 1998). Despite agreement on the multi-semiotic expression of emotion across fields such as psychology, linguistics, and social semiotics, several challenges arise in relation to how each emotion concept and label is defined and what tools and techniques of analysis are employed to describe the semiotic resources speakers use to express emotion. This confusion causes uncertainty for researchers and educators and may interfere with our understanding of findings in the area, making it difficult to assess their validity and the applicability of results to new contexts (Ariztimuño et al. 2022).

In an attempt to address these issues, this paper builds on work from Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL hereafter) on the multi-semiotic expression of emotion, exploring the ways that wordings and vocal qualities work together to express emotion in spoken English. The study examines both the semiotic division of labour and the interplay across affectual verbal and vocal semiotic resources in storytelling performances of the children’s story of Cinderella.[1] In this paper, emotion in spoken communication is considered from a discourse semantic standpoint, looking at patterns speakers use to express positive and negative feelings towards themselves and others, simultaneously exploring “the prosodic nature of the realisation of interpersonal meanings […] [that] tend to colour more of a text than their local grammatical environment circumscribes” (Martin and White 2005: 63). This emotion colouring or charging of oral texts is described here in terms of affectual meanings, drawing on the categories for affect types,[2] subtypes and glosses proposed by Martin (2020a). Affectual meanings are explored multi-stratally in this study, and are considered in terms of their instantiation in the specific context of storytelling. Thus, the affect system at the discourse semantic stratum is realised by the selection and interpretation of verbal resources at the lexicogrammatical stratum as well as the selection and interpretation of non-segmental vocal qualities at the phonological stratum of language.

The term ‘vocal qualities’ is used to refer to non-segmental cues beyond those studied as intonation, rhythm, and salience within the SFL tradition (e.g. Halliday 1967, 1970; Halliday and Greaves 2008; O’Grady 2010; Ramírez-Verdugo 2021; Smith 2008; Tench 1990, 1996; van Leeuwen 1992) but it is important to note that in my work vocal qualities are placed squarely within language (that is, vocal qualities are not considered paralinguistic). Considering this clarification, the current study explores how the verbal and vocal resources storytellers use to express emotion can be interpreted together, integrated as higher-level discourse semantic meanings, what I call ‘up anchored’ as lexicogrammatical and phonological instantiations of the system of affect (Martin 2000, 2020a; Martin and White 2005).

2 Expressing emotion in spoken communication: literature review

While the vocal expression of emotion has been approached through varied disciplinary lenses, including different linguistic perspectives, and perspectives from cognitive science, non-verbal communication and speech synthesis to name a few, the focus here is on previous work on non-segmental vocal features, such as pitch level and range, loudness, tempo, tension, rhythmicality, voice quality, among other characteristics of the voice, in relation to language and emotion.[3] Therefore, accounts of intonation and its role in the expression of attitude conducted by linguists from different schools (e.g. Bolinger 1972; Brazil et al. 1980; Couper-Kuhlen 1986, 2011; Crystal 1969; Fonagy and Magdics 1972; Halliday 1967; Halliday and Greaves 2008; Ladd 1980, 2008; Noad 2016; O’Connor and Arnold 1973; Pike 1945; Roach 2009; Tench 1990, 1996) are acknowledged here as great contributions to the field of phonology but not described any further. For reasons of space, I will not elaborate on multidisciplinary approaches to the expression of emotion in speech which has been developed as vocal cues to speaker affect (Scherer et al. 1984), emotional speech (Roach et al. 1998), vocal communication of emotion (Scherer 2003); vocal expression of affect (Juslin and Scherer 2005) and most recently as acoustic patterning of emotion vocalisations (Scherer 2019). This work includes well documented descriptions of relevant vocal features used to express emotion in a variety of contexts, though mainly focused on computational linguistics and speech synthesis (Douglas-Cowie et al. 2003; Johnstone et al. 2001; Juslin and Scherer 2005; Laukka et al. 2016; Roach 2000; Roach et al. 1998; Schuller et al. 2011). It is important, however to highlight the limitations and challenges that have been reported in this work. These include, the labels used for the description of emotions and the level of detail to which emotions should be categorised (Juslin and Scherer 2005; Scherer 2019); the range of vocal features needed to provide systematic accounts of emotional speech (Roach et al. 1998; Stibbard 2001); and the need to use spontaneous and natural speech including descriptions and considerations of the context in which the emotions occur[4] (Scherer 2003, 2019; Stibbard 2001). In this paper, I consider and address these limitations and challenges approaching the description of how we communicate emotion in spoken language from a SFL perspective.

Most SFL-based work that considers vocal qualities as a resource for enacting attitudes and emotions orally builds on the frameworks proposed by van Leeuwen’s (1999, 2017 [2014]) and by Brown’s (1990 [1977]). Summarising these frameworks,[5] Table 1 presents a comparison of the vocal features they include together with some of the key applications to different contexts.

SFL-based previous work.

| Framework | Vocal features | Key applications |

|---|---|---|

| van Leeuwen (1999, 2017 [2014]) – sound quality descriptions of voice quality as a parametric system network | Tension, roughness, breathiness, loudness, pitch register, vibrato, nasality (7 graded co-occurring features) | Song performance, identity projection van Leeuwen (2022); rapping vs. singing (Caldwell 2014); call centre discourse (Wan 2010); Ngo et al. (2022) expansion of features (voice quality system network) applied to stop-motion film analysis and linked to discourse semantics. |

| Brown (1990 [1977]) – Paralinguistic features | Pitch span, placing in voice range, tempo, loudness, voice setting, articulatory setting, articulatory precision, lip setting, direction of pitch, timing pause (11 features) | Teaching pronunciation (Bombelli and Soler 2001), reading aloud (Soler and Bombelli 2003) , poetry (Bombelli and Soler 2006), children’s stories (Bombelli et al. 2013), genre-based narrative teaching (Germani and Rivas 2017) |

Of great interest to the current study is the system of voice affect (Ngo et al. 2022). Correlating with their facial affect system as paralinguistic expressions of emotion, the voice affect system network proposes three main distinctions for emotions related to ‘spirit’, ‘threat’, and ‘surprise’, with greater levels of delicacy for the first two. As useful as this account is to compare the results obtained in the study, I draw on and develop previous work by Ariztimuño (2016) to argue here that these vocal qualities are part of the phonological resources of language that may co-realise affectual meanings together with wordings (Ariztimuño 2024). Further, regardless of how useful these applications of van Leeuwen’s (1999) system and Brown’s (1990 [1977]) work are, what remains lacking is a systematic description and methodology for analysing vocal qualities with an explicit mention of the point of origin for the system network and the unit of analysis selected.

Considering the varied studies reported in this section, this paper puts forward an analytical framework arising from a project reported in Ariztimuño (2016, 2017, 2024) and Ariztimuño et al. (2022) that builds on Roach et al. (1998) and Roach (2000) framework and foundations to develop an applicable and reliable system network of vocal qualities.

3 Theoretical and methodological pillars

Exploring sound semiosis presents researchers with challenges which force us to question our theoretical and methodological foundations in search of satisfactory and reliable descriptions of speech. Acknowledging these challenges, I now take great care to describe the theoretical underpinning and analytical tools and techniques used to explore the non-segmental vocal qualities in focus here. These methods and techniques have been piloted and tested in my previous work to study the coupling of vocal resources and affectual meanings in a corpus of three stories read aloud by a professional storyteller (Ariztimuño 2016, 2017; Ariztimuño et al. 2022).

3.1 Modelling affectual vocal qualities

Before conducting the perceptual analysis of the expression of emotion in the vocal qualities, a key step involves the researcher’s familiarisation with each speaker in the sample, in my case, with each storyteller’s voice or baselines[6] (Halliday 1985). This is particularly important as vocal qualities are all relative characteristics which vary from one speaker to the next (Brown 1990 [1977]). To obtain speaker baselines for each storyteller, emotionally uncharged instances are identified in the written transcripts and then perceptually divided into tone units[7] which were classified in relation to all vocal qualities explored in this study.[8]

Exploring the association between affectual meanings and the non-segmental vocal qualities selected by the storytellers implies a need to define and describe the vocal qualities that are considered relevant for the expression of emotion in speech. In this study, these non-segmental vocal qualities are systematised following Matthiessen’s (2021) characterisation of phonological system networks which prioritises entry conditions for phonological system networks. Therefore, the description proposed here begins by identifying and defining the tone unit (TU) as the point of origin (Hasan 2014) for the proposed system network and thus as the basic prosodic unit of analysis used to map vocal qualities. This is followed by a characterisation of each system within the vocal qualities system network, and an illustration of the meaning-making potential of these sound choices for the expression of emotion in storytelling.

Establishing phonological units is not a straightforward process as spoken language is a continuous phenomenon, a prosody of sound features we speak and listen to (Firth 1970 [1948]). Despite the continuous nature of speech, as listeners we can still perceive how speakers group strings of sound together and create patterns we can interpret as messages (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014). From a theoretical and descriptive point of view, we can describe these strings as the building blocks which work as units of patterns and thus segment sound into phonological ranks and constituency units of phonemes, syllables, feet, and tone units (Halliday 1967). From an analytical point of view, however, identifying and describing units of analysis is a difficult task, particularly when natural data is used.

Different approaches can be adopted to describe how speech is interpreted as units, often resulting in inconsistent and incomparable results and interpretations (Pascual et al. 2010). Approaching these units from SFL allows us to consider phonological units as one type of building block among all the building blocks of meaning in discourse. To describe the non-segmental vocal qualities, I will focus on the tone unit following Halliday’s (1970: 3) definition: “one unit of information, one ‘block’ in the message that the speaker is communicating” (italics in the original). When dealing with spoken language, the sound contours of speech are key to understanding meanings that do not always map neatly onto the grammatical categories of language, which have been built up based on descriptions of written language and, at times, on idealised and decontextualised language. Therefore, describing how sound features are organised systematically to create meaning in a language and identifying units of meanings, tone units in this study, requires taking a phonological point of view (Halliday and Greaves 2008).

This study proposes the tone unit as the point of origin to represent choices in non-segmental vocal qualities as a parallel system to intonation (Halliday and Greaves 2008) in the phonology stratum of language. To do so, I follow Matthiessen (2021: 309) who defines a set of characteristics that are shared by “networks of phonological systems, where:

the terms in a phonological system are phonological features” (Matthiessen 2021: 309, emphasis in the original) that have paradigmatic value as in air flow: ‘oral/nasal’ in the vocal qualities system network presented here;

“a system has an entry condition” that specifies “the paradigmatic environment in which a given phonological system operates” (Matthiessen 2021: 309, emphasis in the original). In the case of the vocal qualities system network, the entry condition is the tone unit;

“through entry conditions, systems may be ordered in delicacy” (Matthiessen 2021: 309, emphasis in the original) as in ‘oral: egressive/ingressive’; ‘egressive: breathy/– (clear)’; “but they may also be simultaneous, as in” (Matthiessen 2021: 309) pitch: pitch height: ‘high/mid/low’ and pitch: pitch range: ‘wide/medial/narrow’.

The decision to place the set of contrasts considered in the exploratory system network of vocal qualities (initially presented in Figure 1 and further developed in delicacy later on) as part of the stratum of phonology was based on an understanding of “its semogenic value – its function in the total meaning potential of the English language” (Halliday and Greaves 2008: 16).

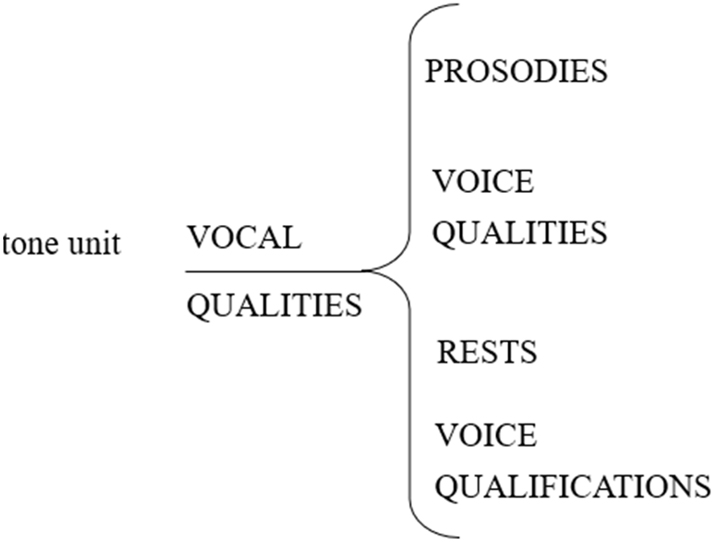

The four main phonological systems of vocal qualities.

The system network shown in Figure 1 models the main phonological systems (developed in delicacy later) that offer simultaneous[9] semogenic vocal options that the storytellers in my data selected as contrastive bundles for the expression of affectual meanings. In a sense, the system network maps some of the features that Halliday (1985: 31) has classified as “not embodied in wording” as well as most of the phonological patterns Martin and White (2005: 35) list as having the potential to realise interpersonal options in appraisal; features such as “loudness, pitch movement and voice quality”. Further, this study suggests an expansion of Martin and White’s list, building on resources that have been considered as relevant for emotion in speech by Roach et al. (1998). As such, this paper presents an attempt to map all the vocal features considered to have what I call ‘affectual sounding potential’ which work together as bundles that can only be interpreted as contextually meaningful. This affectual sounding potential realises different choices in affect by clustering a range of vocal qualities in distinctive ways. The following sections will thus overview the different vocal qualities at play before exploring how they can bundle in rather systematic and stable ways to be perceived and interpreted as affectual profiles.

As shown in Figure 1, the main phonological systems of vocal qualities include prosodies, voice quality, rests and voice qualification. While prosodies and voice quality are inherent to spoken language, rests and voice qualifications are optional additions. Each feature is defined and illustrated with examples from different storytellers in the following sections.

3.1.1 prosodies

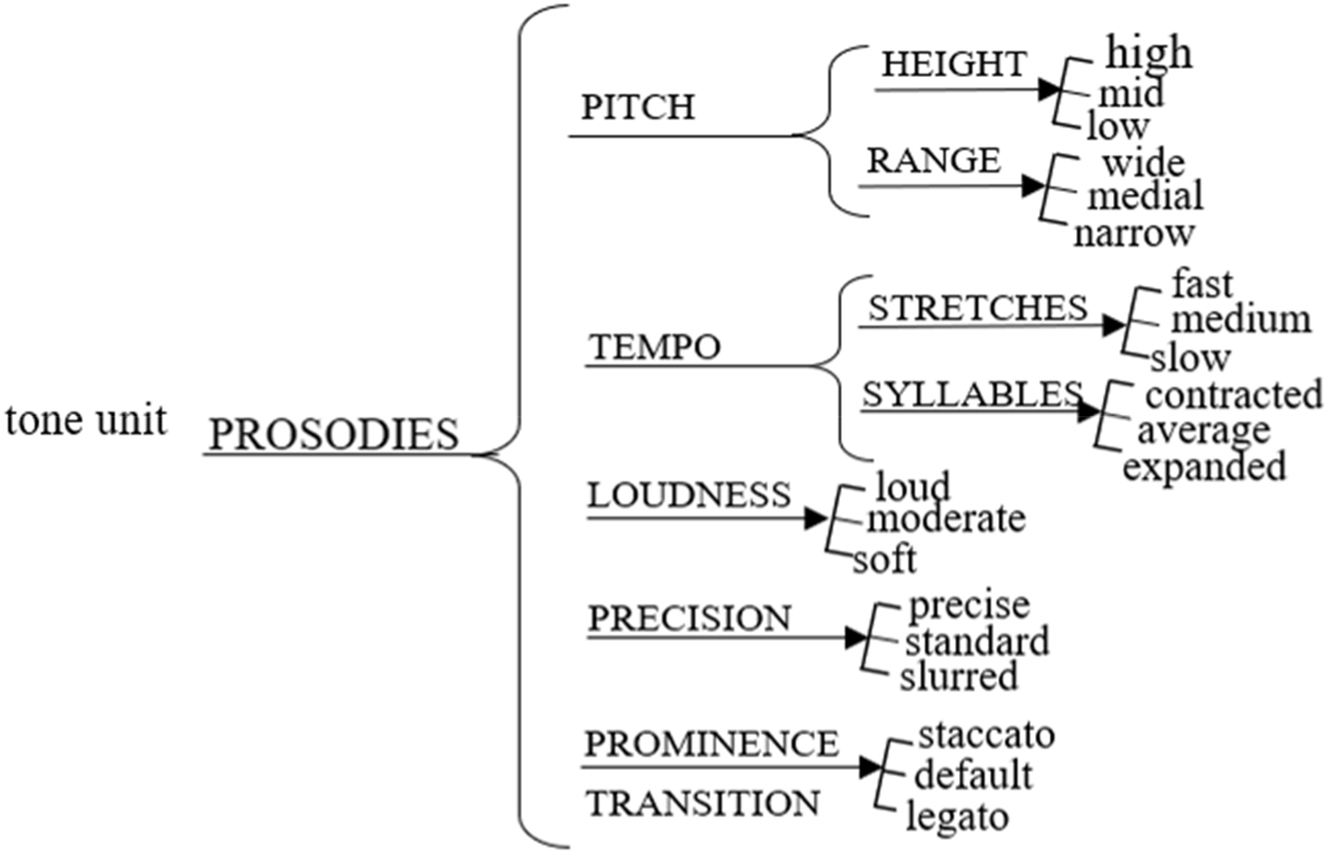

The first main phonological system of vocal qualities, prosodies, models choices of pitch, tempo, loudness, precision, and prominence transition as shown in Figure 2. While pitch height and pitch range are most appropriate considered as realised on the tonic syllable, tempo syllables and precision are considered on any salient syllables of the tone unit and loudness and prominence transition are best measured in the melodic line of the whole tone unit. Nonetheless, each choice radiates meaning across the whole tone unit.

The phonological systems of prosodies.

The first phonological prosodies system captured in Figure 2 is that of pitch. The perceptual phenomenon of pitch has been defined as the auditory sensation that allows us to describe speech sounds in relation to how high or low they are, as well as how much the movement extends from one pitch height to another. This height perception depends primarily upon changes in pitch which are more easily produced and perceived when voiced sounds are used. However, contrasts in pitch can also be heard “in voiceless sounds; even in whispered speech” (Crystal 1980: 272). Taking this into consideration, the choices speakers make in relation to pitch: height and pitch: range can be perceived not only in phonated speech but also in instances of whispered speech. The perception of different levels and widths of pitch requires a further consideration: their relativity. Contrasts have to be perceived in relation to the speaker’s norm as realised in a certain context. In other words, selecting pitch: height ‘high’ means not ‘mid’ or ‘low’ for a certain individual in relation to the level of other salient syllables the speaker has uttered in the same speech instance, with some additional interpretive weight from the degree to which such pitch height would be typical across the speech community, given the communicative context.[10]

The systems for pitch: height and pitch: range involve a cline with three values that indicates points of relative reference to the selected degree of height: ‘high’, ‘mid’, or ‘low’ and range: ‘wide’, ‘medial’, or ‘narrow’. To illustrate the analysis carried out in this study,[11] we will consider a storytelling performance by a speaker called Chris, shown in Table 2.

Examples for pitch values. Audio Table 2 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | pitch height | pitch range |

|---|---|---|

| TU 1// 1 ˆ But / then as her / stepsisters and step / moth er / ˆ | mid | medial |

| TU 2// 1 made their way / off to the / ball , | mid | narrow |

| TU 3// 3 ˆ she / sat on her / door step | mid | narrow |

| TU 4// 1 ˆ and / she / cried / ˆ | High | wide |

| TU 5 // 1 ˆ She’d / so much / wanted to / go to the / ball . | low | narrow |

Table 1 shows the analysis of five tone units. The height and range perceived on each tonic segment (in bold italics ) is described on the columns under the headings: pitch: height and pitch: range. This extract illustrates the simultaneous nature of these two systems of pitch which can combine independently of one another as can be observed in tone units 1 and 2. Whereas TU 1 shows the speaker’s choice of pitch: height: ‘mid’ and pitch: range: ‘medial’, TU 2 exemplifies how speakers can select a different option for pitch: range, ‘narrow’ while still selecting the same value for pitch: height: ‘mid’.

Variations in speed of speech delivery are represented as choices in the system of tempo in Figure 2. Tempo refers to the duration of speakers’ individual syllables and their stretches of speech extending over more than one rhythmical beat, or foot.[12] This phenomenon is perceived as the speeding-up and slowing-down of monosyllables and stretches of speech. The system for tempo: syllables consists of a-three-point cline which represents relative points of reference to options in the extension of at least one syllable in the tone unit, which is perceived as ‘contracted’, ‘average’ or ‘expanded’. In other words, for a tone unit to be classified as ‘expanded’, at least one salient syllable (often the tonic) has to display this feature. In the case of tempo: stretches, three options are also available. Speakers can choose to deliver their utterances at different rates which have been represented as graded values in a cline with three points of reference ‘fast’, ‘medium’ or ‘slow’. Table 3 presents an example from Lindy’s storytelling performance which illustrates how these tempo variables can be combined in different patterns.

Examples for tempo values. Audio Table 3 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | tempo stretches | tempo syllables |

|---|---|---|

| TU 1 // 3 ˆ Well at / last, the / sisters were / read y. // ˆ | medium | average |

| TU 2 // 3 And / Cinder / ella / stood // ˆ | slow | average |

| TU 3 // 3 on the / step and | slow | average |

| TU 4 // 1 waved | slow | average |

| TU 5 // 1 good / bye . | slow | average |

| TU 6 // 1 ˆ And / then she / sat | slow | expanded |

| TU 7 // 3 down | slow | expanded |

| TU 8 // 1 ˆ and / cried . / ˆ ˆ ˆ | slow | expanded |

| TU 9 // 1 All of a / sud den | fast | average |

| TU 10 // 5 ˆ her god mother a / ppeared. | Fast | average |

| TU 11 // 5 ˆ Her / god mother | Medium | contracted |

| TU 12 // 1 ˆ was a / fair y. | Medium | Average |

The interpretation of the speaker’s choices in Table 3 illustrates the simultaneous selection from the tempo: syllables and tempo: stretches systems. For example, tone units 2 to 8 have all been classified as displaying ‘slow’ speed of delivery as the overall perception of syllables per second for this storyteller but not all these units exhibit the same rate for their syllables, with units 2 to 5 coded as ‘average’ and units 6 to 8 as ‘expanded’ because the tonic syllable in these units is articulated over a longer time, expanding the sounds rather than using the unmarked syllable extension.

The vocal quality loudness represents the speaker’s choices in a scale from loud to soft. It describes the relative auditory sensation that corresponds to the degree of lung pressure, that is the muscular effort used in the production of speech and “amount of energy present in sounds” (Roach 1992: 68). Perceptually, this phenomenon consists of a cline with three reference points: ‘loud’, ‘moderate’ or ‘soft’. The choices in this system are illustrated in an instance of Jill’s performance in Table 4.

Examples for loudness values. Audio Table 4 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | loudness |

|---|---|

| TU 1 // 53 But they / kicked her / out of her / own little / bed room | loud |

| TU 2 // 5 ˆ and / made her / sleep | loud |

| TU 3 // 5 ˆ / in the / at tic; | loud |

| TU 4 // 1 ˆ up / all those / stairs | loud |

| TU 5 where it was // 1 cold / ˆ ˆ | moderate |

| // 1 ˆ and it was / dark | soft |

As can be observed in Table 4, Jill starts with ‘loud’ tone units 1 to 4 to then lowering her volume to ‘moderate’ and finally to ‘soft’. Similarly to the other variables exemplified above, these values are relative and need to be interpreted as variations in relation to the individual speaker’s norm and the context in which the speech takes place.

The next system in prosodies is that of precision. This captures the way articulation varies in the tension and energy speakers use to produce sounds (Roach 1992). This tension of articulation impacts the extent to which these sounds are perceived as uttered in a careful, distinct and tense fashion. This overall sense of precision in the articulation of sounds can therefore be placed in a cline system of precision which consists of three points of reference, going from ‘precise’ to ‘slurred’ with an intermediate point for a rather ‘standard’ tension. These three values are illustrated in Table 5 with an extract taken from Richard’s performance.

Examples for precision values. Audio Table 2 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | precision |

|---|---|

| TU 1 // 1 ‘I’m / going / too ,’ said Cinder / ella. / ˆ | standard |

| TU 2 // 13 ‘You’re / what ?’ / ˆ said the / step mother. / ˆ | precise |

| TU 3 // 1‘ Yeah . | slurred |

| TU 4 // 4 You’re / what ?’ | slurred |

| TU 5 // 1 ˆ said the / two / ugly / sis ters. | standard |

The extract represented in Table 5 not only shows choices in precision but also the possibility storytellers have to create characters’ identities and characterisation through choices that display a certain character’s voice norm which may be different to the storyteller’s speaker’s baseline. While these features may index different sociolects and appear to be used in this telling for characterisation, the analysis presented here focuses on how even when storytellers select indexical vocal features for certain characters, variations in the vocal qualities still apply. In this example, the articulation of the stepsisters’ characters varies in the precision with which they articulate sounds as can be perceived by listening to the example and focusing on the changes from ‘standard’ in TU 1 to ‘precise’ in TU 2 mainly realised on the articulatory movements of the instance You’re what? to ‘slurred’ for TUs 3 and 4 to ‘standard’ once again in TU 5.

The last system in prosodies is prominence transition which refers to sense of connectedness or disconnectedness in the transition between the syllables in a tone unit (van Leeuwen 2022). This phenomenon has also been described as the “degrees of rhythmic regularity” (Tench 1996: 27) or rhythmicality perceived for the typical rhythm of English.[13] This system accounts for the marked or smooth transitions between salient and weak syllables, that is, for the “contrasts attributable to our perception of regularly occurring peaks of prominence” (Crystal 1969: 161) over polysyllabic stretches of speech realised as part of one tone unit or in a sequence. It is important to highlight that prominence transition and the different choices speakers make in this category are independent of the tendency of a given language to be stress-timed, as, for example, in the case of English, or syllable-timed, in the case of Spanish. This stress-timed rhythm of English speech has been labelled ‘default’ in the prominence transition system, accounting for a midpoint in a continuum from which speakers may depart to a greater or lesser degree. The two extremes in the continuum, ‘staccato’ and ‘legato’, refer to differences in the modes in which speakers of English transition between prominent and non-prominent syllables (arsis and thesis, respectively) without considering possible variations in pitch (Roach et al. 1998). The feature of ‘staccato’ consists of sharp noticeable contrasts between salient and non-salient syllables whereas ‘legato’ reflects a smooth transition with lesser changes in loudness and duration of syllables.[14] Table 6 illustrates these variations in prominence transition in two extracts from Jill’s performance.

Examples for prominence transition values. Audio Tables 6a and 6b in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | prominence transition |

|---|---|

| TU 1 // 1 ˆ There ap / peared be / fore them | default |

| TU 6 // 1 ˆ a / coach | legato |

| TU 7 //1 ˆ a / golden / coach – | legato |

| TU 2 // 1 ˆ with / great / gold / wheels | legato |

| TU 3 // 1 ˆ and / fine / gold / fil igree, | legato |

| TU 4 // 1 ˆ like the / tendrils on a / pump kin / vine. | legato |

|

|

|

| Tone unit analysis | |

|

|

|

| TU 5 // 1 ˆ With / all that / run ning, | default |

| TU 6 // 1 ˆ she / made it / home | default |

| TU 7 // 1 ˆ / only / sec onds | staccato |

| TU 8 // 1 ˆ be / fore | staccato |

| TU 9 // 1 ˆ the / step sisters | staccato |

| TU 10 // 1 ˆ / in their / coach . | staccato |

As can be seen in Table 6, the first extract exemplifies the options of ‘default’ in TU 1 and the ‘legato’ value in TUs 2 to 4 while the second extract presents a shift from ‘default’ in TUs 5 and 6 to ‘staccato’ in TUs 7 to 10.[15]

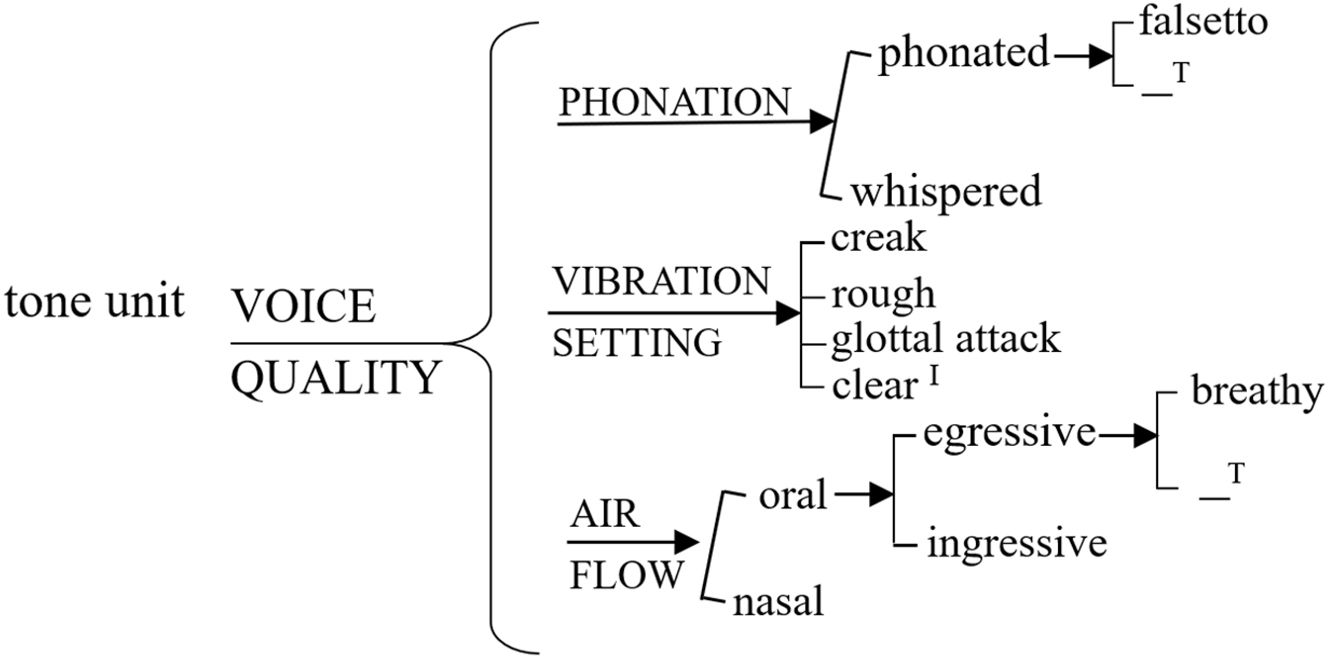

3.1.2 voice quality

The second main phonological system within vocal qualities is voice quality represented in Figure 3 . The system shows the choices speakers can make in relation to the different combined postures adopted by the organs of speech. In this sense, voice quality is “present more or less all the time that a person is talking: it is a quasi-permanent quality running through all the sound that issues from his mouth” (Abercrombie 1966: 89).

voice quality system. The superscript I/T in the voice quality system show an if/then relation, meaning if ‘clear’, then non falsetto and non breathy.

The three simultaneous systems, as shown by the curly bracket in Figure 3, are identified depending on what articulatory postures affect the perception of three phenomena described in detail below: phonation, vibration setting and air flow.

The general term phonation has been used in mainstream phonetics to refer to the different “laryngeal possibilities” (Crystal 1980: 265) speakers may produce to colour the setting of their speech. The system of phonation, however, includes only graded choices related to the perception of vocal fold vibration as ‘phonated’ or ‘whispered’ throughout the tone unit. If a speaker chooses to use ‘phonated’ speech, a further step in delicacy can be taken with the optional value, ‘falsetto’. The selection of ‘falsetto’ represents apparent effort of forcefully produced speech in a higher setting than the speaker’s typical range (shown by the dash ‘_’ in the system network). The ‘whispered’ end of the cline accounts for the perception of a hushing sound speakers produce when the airflow passing through the larynx is turbulent and the vocal folds are not vibrating. Table 7 illustrates each value of phonation in two extracts.

Examples for phonation values. Audio Tables 7a and 7b in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | phonation |

|---|---|

| TU 1 // 3 ˆ And / as she / was / buttoning them / up and | _ |

| TU 2 // 3 doing their / la ces they | _ |

| TU 3 // 3 said , / ˆ ˆ | _ |

| TU 4 // 4 Cinder / el la, / ˆ | _ |

| TU 5 // 2 wouldn’t / you / like to / go to the / ball ?’ | _ |

| TU 6 // 2 ˆ they / teased . | falsetto |

|

|

|

| Tone unit analysis | |

|

|

|

| TU 1 // 1 The / music / started back / up a / gain, / ˆ | _ |

| TU 2 // 1 as / did the / whis pers. | whispered |

| TU 3 // 5 “Who / is she?” / ˆ | whispered |

Lindy’s extract shows how storytellers use features of voice quality to create different characters in the story and to express affectual sounding potential. While TUs 1 to 5 are instances where the Lindy selects a rather high falsetto kind of voice to show the stepsister’s voice (not coded, therefore, for ‘falsetto’ as they are part of the identity of the character), TU 6 has been coded for ‘falsetto’ as a selection from the vocal qualities system expressing affectual sounding potential. Jill’s extract illustrates the ‘whispered’ as one extreme of the phonation cline with ‘phonated’ speech at the other end.

The system of vibration setting represents the distinction in the way vocal cords behave in a stretch of speech. Four features can be selected: ‘creak’, ‘rough’, ‘glottal attack’ (after Roach et al.’s [1998] categories), and ‘clear’. The ‘creak’ option represents the auditory perception of a stretch of speech coloured by a sound similar to running a hard stick against an iron railing which is described in articulatory terms as a very slow periodic vibration of one end of the vocal folds (Crystal 1980). This is illustrated in Table 8.

Example for vibration setting: ‘creak’. Audio Table 8 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | vibration setting |

|---|---|

| TU 1 // 1 Who runs / off like / that? | clear |

| TU 2 // 1 So / rude . | clear |

| TU 3 // 4 Cinder / el la! / ˆ | creak |

| TU 4 // 1 Help me / out of my / pins !” | creak |

This example shows the option a speaker has to shift from a rather clear vibration setting to a creaky voice ‘creak’. The same storyteller selects a different option a couple of minutes later in her performance described in Table 9, producing a vibration setting perceived as ‘rough’ where the vocal fold vibration is unsynchronised and irregular in its articulation. This is, in turn, perceived as an unsteady, bumpy sound which persists over a long stretch of time.

Example for vibration setting: ‘rough’. Audio Table 9 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | vibration setting |

|---|---|

| TU 1 // 3 Let me / try // 1 right / now !” | clear |

| TU 2 // 1 ˆ And they / squeezed and | clear |

| TU 3 // 1 squashed as | rough |

| TU 4 // 1 hard as they / could , | rough |

| TU 5 // 1 but / they / could / not / put their / feet / in / to the / glass / slip per. / ˆ ˆ | rough |

A third feature can be selected from vibration setting: ‘glottal attack’. This phenomenon is perceived when speakers produce a clicking noise, resulting from a forceful abduction of the vocal folds. In English, this is often clearly audible before vowels, as in the extract illustrated in Table 10 where glottal attacks can be heard before ‘ugly’ and ‘every’.

Examples for vibration setting: ‘glottal attack’. Audio Table 10 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | vibration setting |

|---|---|

| TU 1 // 3 ˆ And / they grew / more and / more | clear |

| TU 2 // 1 ˆ / ug ly | glottal attack |

| TU 3 // 1 ˆ and / sel fish | clear |

| TU 4 // 1 ˆ / every / day . | glottal attack |

Voice quality is also affected by whether the speaker releases air through the oral or nasal cavity when speaking. This choice is represented in the system of air flow, with a graded cline going from the ‘oral’ value to the ‘nasal’ one.[16] The ‘nasal’ value is perceived as the type of speech speakers produce when they have a blocked nose. When the airflow is ‘oral’, it can either be produced with outgoing air pushed out of the lungs with ‘egressive’ air expelled out of the mouth (Roach 2009) or using ‘ingressive’ air audibly inhaled through the mouth.[17] English uses mainly the ‘oral: egressive: _’ option (Ladefoged 1975). A further choice in the ‘egressive’ system can be made to show an apparent sound of air coming out represented with the ‘breathy’ value. Table 11 shows examples extracted from Richard’s performance.

Example for air flow values. Audio Table 11 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | air flow |

|---|---|

| TU 1// 3 Cinder / ella sat / down at the / kitchen / ta ble | _ |

| TU 2 // 1 ˆ and / sighed / ˆ | breathy |

| TU 3 // 5 All of a / sud den | nasal |

| TU 4 // 1 ˆ a / tear / rolled / down and | nasal |

| TU 5 // 1 hit the / ta ble | nasal |

In English, the default language setting tends to pre-select a rather ‘clear’ vibration setting. This feature is perceived when speakers combine this specific feature with phonation: ‘ _ ’ and air flow: ‘ _ ’. This is shown in the system network with the if/then (superscript I/T) to be interpreted as if ‘clear’, then non falsetto and non breathy.

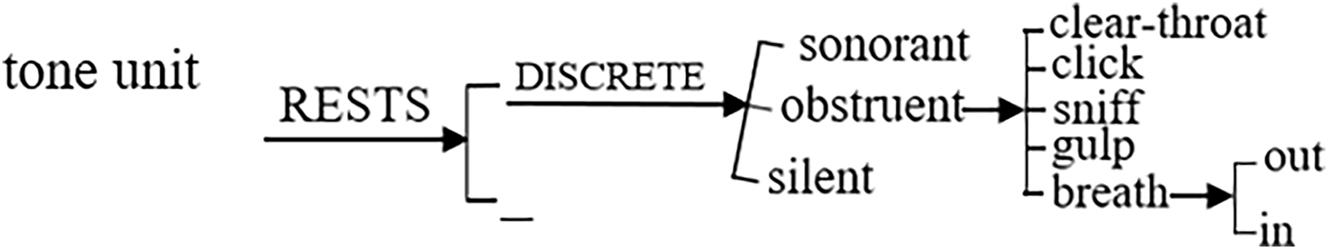

3.1.3 rests

The third main phonological system within vocal qualities refers to rests which are defined as an interruption in connected speech which can vary in length from at least one beat (ˆ) to as many as the speaker considers necessary. The perception of this interruption occurs in contrast to the fused tone unit boundary which is not perceived as a break in the speech continuum but rather as a different realisation of the initial foot of the tone unit. When rests are perceived, they can be noticed as an absence of sound – silence – or as an audible sound, which can be either voiced or voiceless. Figure 4 shows the different values suggested for rests.

rests system.

Three sound choices are placed along a graded cline in the discrete system representing how speakers produce different types of sounds at the boundaries of tone units. These sounds can be perceived as ‘sonorant’ when their production involves spontaneous voicing and a flow of air running relatively free through the mouth and/or the nose, such as what occurs when we produce hesitation fillers. Other sounds occupying the tone unit boundaries can have some kind of obstruction or stricture that impedes the airflow from running freely, creating a perceivable noise when produced have been clustered together in the ‘obstruent’ value. The last category in the cline represents instances of silence or absence of sound with the feature ‘silent’ in the system. This is the most noticeable way in which rests can be perceived, as they clearly interrupt the flow of speech. One further step in delicacy can be taken within the ‘obstruent’ system to differentiate the kind of sound perceived as ‘clear-throat’, ‘click’, ‘sniff’, ‘gulp’, and ‘breath’ (Roach et al. 1998). The category of ‘breath’ can be further explored to indicate the direction of the air as going in ‘breath: in’ or out ‘breath: out’. Table 12 illustrates one example from discrete system.

Example for rests discrete values. Audio Table 12 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | rests discrete |

|---|---|

| TU 1 // 1 ˆ And / Cinderella / wiped her / tears away and / said / ˆ | obstruent: sniff |

| TU 2 // 3 ˆ I / just | _ (fused) |

| TU 3 // 1 ˆ I just / wanted to / go to the / ball but it | _ (fused) |

| TU 4 // 1 doesn’t / mat ter / ˆ | silent |

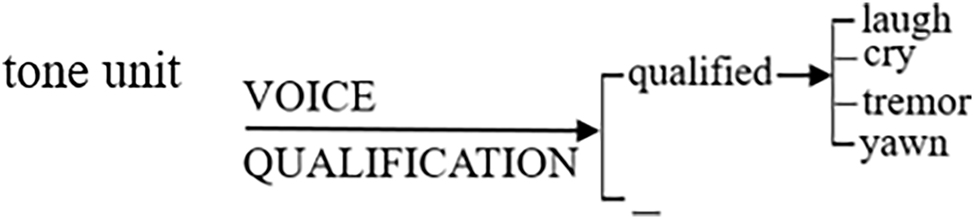

3.1.4 voice qualification

The fourth main phonological system within vocal qualities accounts for different voice qualifications which involve optional phenomena that may run through or interrupt speech in the form of spasmodic air pressure coming out in pulsating breaths (Crystal and Quirk 1964; Roach et al. 1998). These features are different from all other vocal qualities because they can occur within the tone unit, at the rest or both, within the tone unit and the rest. The affectual sounding potential these qualities bring when clustered with other vocal qualities, however, impacts the whole information unit where they occur. Figure 5 represents the options in terms of voice qualification, including an optional feature of ‘qualified’ speech and the default ‘_’ choice which can be interpreted as plain speech.

voice qualification system.

Four values are used to represent the different types of pulsating breaths speakers can select as ‘qualified’ speech: ‘laugh’, ‘tremor’, ‘cry’, and ‘yawn’. The labels are self-explanatory and can be easily perceived by the naked ear. One example is included in Table 13 to illustrate.

Example for voice qualification. Audio Table 13 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | voice qualification |

|---|---|

| TU 1 // 1 ‘ Oh! ’ / ˆ said the / fairy / godmother, | laugh |

| TU 2 // 1 ‘Yes . | laugh |

| TU 3 // 1 Well, I for/ got / all about / that. | laugh |

As can be seen and listened to in the examples included in Table 13, the features represented in the system of voice qualification can take place at different moments in the speech continuum.

4 Affectual vocal profiles

Having a clear methodological and theoretical understanding of what each feature in the vocal qualities system stands for, we can now explore how they work together as contrastive bundles for the expression of affectual meanings in a corpus of eight storytelling performances of Cinderella. To do this, the results presented in this section show the association between emotional meanings identified in terms of affectual glosses proposed in Martin’s (2020a) affect description labels and the phonological choices the storytellers selected for each system of vocal qualities. [18] This rather stable association is then presented as affectual vocal profiles which are supported by a comparison with prior research findings on the vocal expression of emotion where necessary and examples.

4.1 Developing the affectual vocal profiles

The development of the affectual vocal profiles arises from the analysis of a total of 440 tone units extracted from eight storytelling performances of Cinderella. These profiles result from extracting the tendencies of association between affectual glosses proposed in Martin’s (2020a) and the features selected from the vocal qualities system. This association is described in terms the percentages of co-occurrence for each gloss and each vocal feature explained in Section 3.[19] As a result, I now present in Tables 14 and 15 twelve affectual vocal profiles which constitute clusters of unique patterns of expression selection from the vocal qualities system. Each of the affectual vocal profiles proposed is illustrated with an audio file which can be accessed in the Supplementary Material provided for this paper as Audio file affectual gloss label, for example, Audio file ‘fear’.

Affectual vocal profiles for ‘+/−inclination’: ‘desire’ & ‘fear’ and ‘+/−happiness’: ‘misery’, ‘cheer’, ‘antipathy’, ‘affection’.

| Affectual gloss vocal qualities |

‘fear’ 42 TU |

‘desire’ 22 TU |

‘misery’ 71 TU |

‘cheer’ 40 TU |

‘antipathy’ 30 TU |

‘affection’ 39 TU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [prosodies] | ||||||

| [pitch: pitch height] | high (Lim) | mid (S) | low (G) | mid (Lim) | high (G) | mid to low (G) |

| [pitch: pitch range] | medial to wide (G) | medial (Lim) | narrow (G) | narrow to medial (G) | wide (Lim) | medial to narrow (G) |

| [tempo: tempo stretches] | fast (G) | medium to slow (Lim) | medium to slow (G) | medium to slow (Lim) | fast (G) | medium (Lim) |

| [tempo: tempo syllables] | average (Lim) | average (G) | average (Lim) expanded |

average to expanded (Lim) | expanded (G) | average to expanded (G) |

| [loudness] | loud to moderate (G) | soft (Lim) | soft (G) | moderate to soft (G) | loud (Lim) | soft to moderate (G) |

| [precision] | precise (S) | standard (Lim) | standard (S) | standard (Lim) | precise (G) | standard (G) |

| [prominence transition] | default (Lim) staccato |

default (S) | default (S) | default (S) | default (G) | default (S) |

| [voice quality] | breathy (G) | clear (G) breathy |

clear (S) | clear (G) glottal attack /breathy |

creak (Lim) breathy |

clear (G) breathy |

| [rests] | ||||||

| fused (G) | fused (G) | ˆ silent to fused (G) breath-in |

ˆ silent to fused (G) | fused (G) | fused (G) | |

| [voice qualification] | ||||||

| plain (S) | plain (S) | plain (G) tremor / cry |

plain (S) | plain (G) laugh |

plain (S) tremor |

|

-

S, strong co-occurrence value; G, good co-occurrence value; Lim, limited co-occurrence value. Co-occurrence values have been considered as limited (Lim) to acknowledge the fact that not one single option within that dimension clearly prevailed in the descriptive statistics. Terms in italics were not as frequent as the others but are still considered to contribute to the relevant vocal profile, unlike options not specified here at all (for example, the features ‘tremor’ and ‘cry’ were observed for the affectual profile of ‘misery’ but less frequently than ‘plain’).

Affectual vocal profiles for ‘+/−satisfaction’: ‘displeasure’, ‘pleasure’ & ‘interest’, and ‘+/−security’: ‘disquiet’, ‘perturbance’ & ‘confidence’.

| Affectual gloss vocal qualities |

‘displeasure’ 16 TU |

‘pleasure’ 21 TU |

‘interest’ 56 TU |

‘disquiet’ 49 TU |

‘perturbance’ 39 TU |

‘confidence’ 15 TU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [prosodies] | ||||||

| [pitch: pitch height] | high (G) | high (Lim) | high to mid (Lim) | high (S) | high (Lim) | mid to high (Lim) |

| [pitch: pitch range] | wide (Lim) | medial (Lim) | medial (Lim) | medial to wide (Lim) | wide (Lim) | medial (G) |

| [tempo: tempo stretches] | medium to fast (Lim) | medium (Lim) | fast to medium (Lim) | fast (S) | fast to medium (Lim) | medium/slow (L) |

| [tempo: tempo syllables] | expanded to average (Lim) | average to contracted (Lim) | average (Lim) | average to contracted (Lim) | average to expanded (G) | expanded (G) |

| [loudness] | loud (G) | moderate (Lim) | moderate to soft (Lim) | moderate (G) | moderate (Lim) | loud (G) |

| [precision] | precise (G) | standard (Lim) | standard to precise (G) | precise (G) | precise (Lim) | precise (G) |

| [prominence transition] | default (Lim) staccato |

default (S) | default (S) | default (G) | default (S) | legato (S) |

| [voice quality] | rough/breathy (Lim) | clear (G) breathy |

creak (Lim) breathy |

clear / breathy (L) | breathy (Lim) clear |

clear (G) breathy |

| [rests] | ||||||

| fused (Lim) | fused (S) | fused (G) ˆ silent/breath-in |

fused (G) | fused (G) ˆ silent/breath-in |

fused (G) ˆ silent |

|

| [voice qualification] | ||||||

| plain (S) | plain (S) | plain (S) | plain (G) tremor |

plain (S) | plain (S) | |

-

S, strong co-occurrence value; G, good co-occurrence value; Lim, limited co-occurrence value; L, low co-occurrence value. Terms in italics were not as frequent as the others but are still considered to contribute to the relevant vocal profile, unlike options not specified here at all (for example, the feature staccato was observed for the affectual vocal profile of ‘displeasure’ in 7 out of 16 TU (44 %) of the cases which was less frequent than ‘default’ but still relevant to mention.

Tables 14 and 15 deploy twelve affectual vocal profiles that present the rather stable phonological realisation of affectual glosses in terms of the vocal qualities examined in this study. To exemplify, 71 tone units were classified as ‘misery’ following Martin’s (2020a) affect glosses and after analysing each tone unit in terms of all the vocal qualities features explained and exemplified in Section 3, the affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’ results from interpreting the following configuration of features in the storytelling performances:

for pitch height, 72 % of the tone units (51 out of 71) were assigned the feature ‘low’ and therefore the affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’ includes low in its configuration;

for pitch range, 65 % (46/71) were assigned the option ‘narrow’;

for tempo stretches, 48 % of the 71 tone units were classified as ‘medium’ and 45 % were classified as ‘slow’, together accounting for 93 % of all cases; thus for the vocal profile of ‘misery’, the dimension of tempo over stretches of talk is specified as ‘medium’ to ‘slow’;[20]

for tempo syllables, 58 % of the tone units (41/71) were labelled ‘average’;

for loudness, 75 % (53/71) were assigned the feature ‘soft’;

for precision, 87 % (62/71) were considered as ‘standard’;

for prominence transition, 100 % of the cases were coded as ‘default’;

voice quality is mainly ‘clear’ with 87 % of the tone units (62/71);

the choices for rests show tendencies for a greater occurrence of ‘perceived: discrete’ features, mainly ‘silent’ (44 %) and ‘ˆ’ in 51 % for perceived: length;

for voice qualification, 72 % of the cases (51/71) were assigned the feature ‘–’ interpreted as plain.

The same rationale is applied to develop each of the affectual vocal profiles for ‘fear’, ‘desire’, ‘cheer’, ‘antipathy’, ‘affection’, ‘displeasure’, ‘pleasure’, ‘interest’, ‘disquiet’, ‘perturbance’, and ‘confidence’.

Tables 14 and 15 also include the degree of co-occurrence value marked with (S) for strong, (G) for good, (Lim) for limited, and (L) for low. This shows how each feature chosen from the vocal qualities system is likely the co-occur with each affectual vocal profile. This co-occurrence value was gauged considering the relative frequency of association between the vocal qualities feature and the affectual category. Where multiple categories within a dimension were specified as part of the vocal profile for an emotion, the level of association between that dimension and the emotion in question was adjusted down one level. For example, for the dimension pitch: range, the features ‘medial’ range and ‘wide’ range were both specified as part of the vocal profile for the emotion ‘fear’, and to accommodate this lack of precision, the co-occurrence value was adjusted from strong (S) to good (G). The co-occurrence value in relation to the percentages obtained was considered as follows:

Strong co-occurrence value was allocated to frequencies of occurrence higher than eighty-five percent (≥85);

Good co-occurrence value was allocated to frequencies of occurrence between sixty-five and eighty-five percent (≥65 < 85);

Limited co-occurrence value was allocated to frequencies observed between fifty to sixty-five percent (≥50 < 65); and

Low co-occurrence value was allocated to frequencies of occurrence lower than fifty percent (<50).

Only two features tempo stretches: ‘medium/slow’ & ‘confidence’ and voice quality: ‘clear/breathy’ & ‘disquiet’ rendered low degrees of co-occurrence. The remaining features rendered a strong co-occurrence value in 20 % of the cases, good in 42 % and limited (but still 50–65 % correlation with relevant AFFECT coding) in 36 %. These co-occurrence values offer a fairly stable description of the affectual vocal profiles observed in this sample of storytelling performances. Further, the detailed description of the techniques and methods followed to obtain this perceptual description of the oral realisation of emotion within a SFL perspective fosters the reliability and replicability of this study.

The affectual vocal profiles proposed in Tables 14 and 15 proved a useful perceptual guide to describe and name the features we hear as similar or contrastive when we are listening for affectual meaning. The slight or marked differences between profiles grouped within and across affect types held across different lexicogrammatical realisations in the data sample, either to congruently realise the same affectual meaning with verbiage and vocal profiles or to realise non-congruent affectual meanings. Therefore, it could be argued that this inter-stratal alignment between lexicogrammatical and phonological co-realisations worked independently from the modes of realisation selected by the storyteller at the stratum of lexicogrammar to inscribe or invoke affectual meanings in the performed story. I will pursue this argument regarding the independent phonological realisation of emotion below, but before taking this argument up in detail, I present the affordances of the affectual vocal profiles with illustrations of different affectual meanings in the next section.

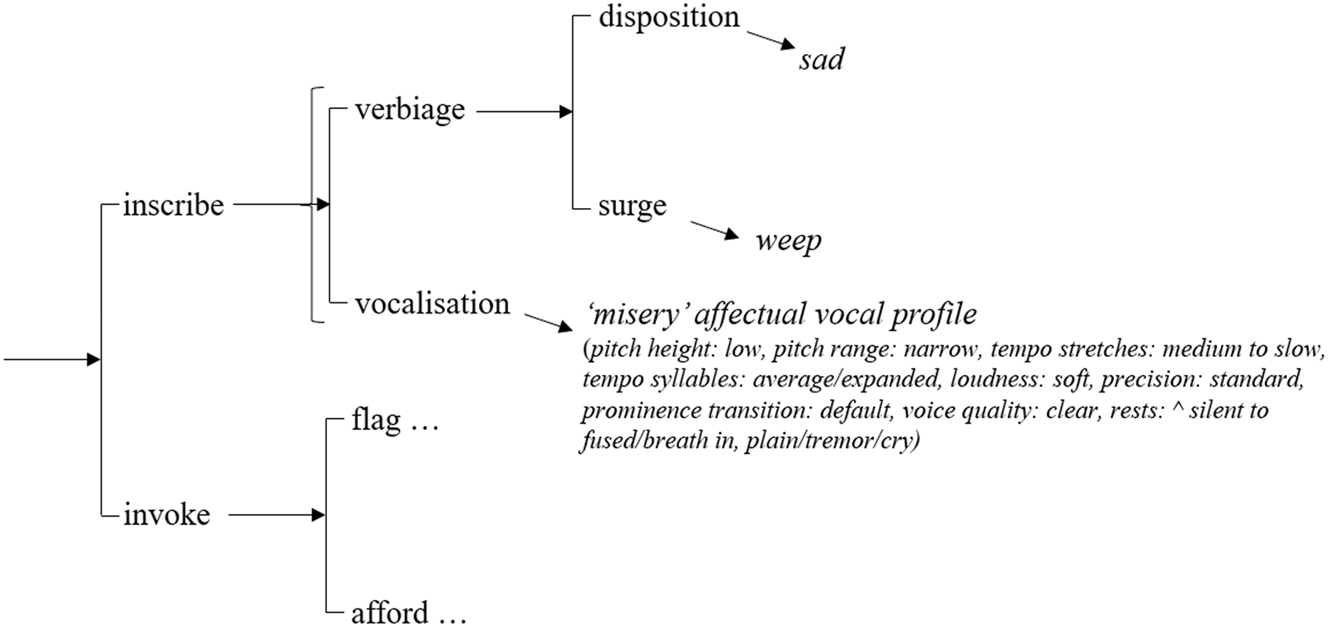

4.2 Exploring affectual vocal profiles in the storytelling performances of Cinderella

The use of vocal features to express emotions by storytellers has been described from perceptual, qualitative perspectives (e.g. Lwin 2010, 2019; Swann 2002; Tench 2010) and from acoustic quantitative approaches (e.g.Montaño and Alías 2016). However, none of these descriptions has tackled a wide range of emotions or vocal qualities or framed the association between choices in wording and choices in vocal qualities within a SFL account of spoken language. Further, this study explores the expression of emotion in storytelling not only in inscriptions of emotion (Ariztimuño 2016) but also in invocations, both of which are then described for their oral realisation in terms of vocal qualities. Importantly, capturing both inscribed and invoked modes of realising emotions can be related to different levels of implicitness (Bednarek 2008), which rely largely on audience members’ reading position for their interpretation (Macken-Horarik and Isaac 2014). To show this, I start discussing instances of co-realisation of affectual meanings by verbiage and affectual vocal profiles with the most explicit direct interpretative cues for affect in the verbiage: the realisation of affectual inscriptions by mental disposition terms such as sad and behavioural surges such as cry. I then continue my analysis with the most implicit indirect interpretative cues for affect, realised by experiential meanings that invoke affectual meanings, such as But she had no mother because the rich man’s wife had died. In this way, I capture the realisation of different degrees of explicitness for affectual meanings, such as ‘misery’.

Across the performances examined here, it is notably the protagonist, Cinderella, who is most frequently depicted by the storytellers as experiencing sadness: in other words, the affectual meaning of ‘misery’ consistently couples with (Martin 2008) the protagonist, Cinderella. Since this coupling between Cinderella and ‘misery’ appears crucial for the typical patterns of characterisation and higher order meaning (literary theme), I will use this coupling to explore and exemplify the affordances of affectual vocal profiles to create emotional strands of meaning in the story, adding in examples of other affectual meanings and other emoters where relevant. I focus first on one instance which highlights the shift in Cinderella’s life from when she was a young girl and her mother was alive to when Cinderella’s mother died as presented in Table 16.

Example of verbiage and affectual vocal profile realisation for ‘cheer’ versus ‘misery’. Audio file Table 16 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | pitch height | pitch range | tempo stretches | tempo syllables | loudness | precision | prominence transition | voice quality | rests | voice qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TU 1 // 1 once | mid | medial | medium | average | moderate | standard | default | clear | _ (fused) | _ (plain) |

| TU 2 // 1 there was a / little / girl / ˆ | mid | medial | medium | average | moderate | standard | default | clear | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| TU 3 and at // 1 first / she was / so / hap py / ˆ | high | medial | medium | average | loud | precise | default | clear | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| TU 4 but // 1 then / one / day her / moth er / died / ˆ | low | narrow | medium | average | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ breath:in | _ (plain) |

| TU 5 // 1 ˆ and she was / very / sad / ˆ | low | narrow | medium | average | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ breath:in | _ (plain) |

-

Cells are filled with different colours to highlight the contrast between the vocal qualities choices and to show different affectual vocal profiles. Colour orange is used for ‘cheer’, light blue is used for ‘misery’, unshaded cells indicate attitudinally uncharged. TUs 3 & 4 include the conjunctions before the double slants (//) that show the beginning of the tone unit to prioritise understanding of information units.

The example presented in Table 16 shows the shifts in affectual meanings that speakers can make by producing slight changes in their selection of options from the vocal qualities system to co-realise inscriptions in the verbiage.[21] In this example, the storyteller starts his performance with the Orientation of the story, introducing Cinderella, the main character, as a little girl. As expected from the habitual and undisrupted state of affairs set up by this stage in the narrative genre (Hasan 1996 [1984]), the first tone units (TU 1 & 2) are uttered as matter of fact, what I call uncharged, with no indications of attitudinal meanings either in the verbiage nor the vocal qualities. The following tone unit, TU 3, introduces a shift from this initial introduction of Cinderella as a little girl to a positively coloured affectual choice co-articulated in the verbiage by the quality happy and in the affectual vocal profile that co-operates with the verbiage to realise a choice for the discourse semantic system of affect [Cinderella ≤ +happiness: ‘cheer’].[22] The storyteller’s pitch: height choice moves from ‘mid’ in TU 2 to ‘high’ in TU 3 to highlight the shift and this change is accompanied by shifts in loudness from ‘moderate’ to ‘loud’ and precision from ‘standard’ to ‘precise’.

Finally, TU 4 and 5 contrast Cinderella’s previous positive happiness with a negative feeling of sadness triggered by her mother’s death [Cinderella ≤ −happiness: ‘misery’ ≥ her mother’s death]. This new affectual state is realised by unmarked choices in the verbiage invocation but then one day her mother died in TU 4, the inscription in TU 5 (quality sad upscaled by very) and by the clear change in five of the vocal qualities systems to match most features of the affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’ (low, narrow, medium, average, soft, standard, default, clear, ˆ breath-in, plain) in both TUs. This example illustrates the affordance that affectual vocal profiles have to realise affectual meanings as vocalisation either inscribed or invoked in the verbiage,[23] and the shifts and contrasts in affect that drive authentic spoken interaction.

Cinderella’s sadness inscribed in the quality sad is not always realised by the unmarked affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’. Table 17 presents the transcription of a selection of instances where the storyteller Jill uses the quality sad to create an interesting contrast in the way she co-selects sad with both the expected affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’ and with the affectual vocal profile for ‘perturbance’.

Example of verbiage and affectual vocal profile realisation for the quality sad. Audio file Table 17 in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis | pitch height | pitch range | tempo stretches | tempo syllables | loudness | precision | prominence transition | voice quality | rests | voice qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TU 1 // 5 And it was / then that she / rea lised / ˆ ˆ ˆ | low | narrow | medium | average | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ ˆ ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| TU 2 // 5 ˆ she was / so / sad / ˆ | low | narrow | slow | expanded | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| TU 3 // 5 ˆ and / so a / lone / ˆ | low | narrow | slow | expanded | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| How she longed to go to that ball! How she wondered what the inside of a palace might be like! How she- how she was curious and dying to know! Wouldn’t it be wonderful to go to the ball and maybe even meet a real-life prince? But instead, she had to stay at home and do work, and sleep on the stones. She started to cry. And she cried, and she cried. | ||||||||||

| She cried so hard she didn’t even notice when, suddenly, her fairy godmother appeared right next to her. “Fairy godmother!” | ||||||||||

| pitch height | pitch range | tempo stretches | tempo syllables | loudness | precision | prominence transition | voice quality | rests | voice qualification | |

| TU 4 // 2 you / look / sad / ˆ | high | wide | medium | expanded | loud | precise | default | cleara | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| TU5 // 3 Yes / well I | mid | narrow | slow | contracted | soft | standard | default | cry | _ (fused) | tremor |

| TU 6 // 5 ˆ I / am / sad / ˆ | high | wide | medium | expanded | moderate | precise | default | clear | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

-

aThe storyteller is portraying the godmother’s character with a falsetto phonation which is considered as indexical for this character and therefore not marked as part of the vocal qualities.

Table 17 starts with an extract from the story where the storyteller describes Cinderella as the emoter of ‘misery’, co-realising this affectual meaning through verbiage and the affectual vocal profile in TUs 1–3. A bit later in the story, the godmother appears to help Cinderella. The godmother’s message transcribed as TU 4 in Table 17 is not, however, as straightforward in realisation as Cinderella’s turn in TUs 1–3. As can be seen from these instances, co-realisation through verbal and vocal resources foregrounds one affectual meanings to be interpreted by the listener. However, when the verbal and the vocal affectual meanings differ, they put forward a combination of affectual meanings, ‘misery’ and ‘perturbance’, which are equally important for the listener to understand the emotional ensemble presented by the storyteller. Accounting for the affectual vocal qualities is, therefore, necessary to discern significant aspects of the affectual meanings that are crucial to this telling.

Our interpretation of this example foregrounds the advantages of interpreting language from the SFL relational theory of language. Our interpretation and description of the meanings construed by the godmother lie mainly in understanding how choosing an option from all potential possibilities of the system of language at play projects a context that can match the expected one in that particular communicative situation or that can add to or even disrupt the interactants’ own interpretation of that situation.

In the example described in Table 17, the godmother’s first line in the performance when she appears to help Cinderella was transcribed into the writing system of English as You look sad. If we consider this transcription from a multi-stratal perspective, in what Halliday (1970: 51) calls a “neutral”, “most likely” realisation of the extract in the context of the story of Cinderella and what we know (or expect) about the relationship between Cinderella and her godmother, we can make a ‘top-down’ description. Accordingly, in this instance we would expect a neutral realisation of the affectual meaning construed by the quality sad [Cinderella ≤ −happiness: misery] by the affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’ following the configuration of vocal qualities suggested in this study: ‘low’, ‘narrow’, ‘medium to slow’, ‘average’, ‘soft’, ‘standard’, ‘default’, ‘clear’, ‘ˆ silent to _ (fused)’, and ‘_ (plain)’.

Contrary to this likely realisation for this co-text and context, the storyteller selects a different set of options to realise the verbiage you look sad and thus projects a different context than the one we could have imagined as readers of the written transcription of the performance. In order to interpret this contrasting context, I take a ‘bottom-up’ approach and start with its phonological realisation. The verbiage you look sad is realised as one tone unit realised by a selection of vocal qualities that bundle up to create an affectual vocal profile that colours this message with a feeling of ‘perturbance’. However, this additional feeling of ‘perturbance’ is not appraising Cinderella’s inner state but indicates an additional affectual source, the godmother. In other words, when we consider the affectual meanings in this message as phonologically realised by this storyteller we need to account for two emotional sources: Cinderella emoting ‘misery’, realised in the quality sad [Cinderella ≤ −happiness: misery] and the godmother emoting ‘perturbance’ realised by the affectual vocal profile for ‘perturbance’, [godmother ≤ −security: perturbance ≥ Cinderella being sad], to describe the full display of affectual meanings enacted in this message.

As can be seen from this instance, the verbiage affordances to construe Cinderella’s experience of sadness cooperate with the vocal affordances to construe the godmother’s experience of surprise. I argue that this demonstrates that an effective account of how we communicate emotion in spoken language can only be complete through a multi-stratal description of the lexicogrammatical and phonological realisations of affectual meanings because additional meanings and sources of meanings can only be fully accounted for this way.

In order to strengthen this argument, I now present a multi-stratal account of the affectual realisation of Cinderella’s response transcribed as TUs 5 and 6 in Table 17. Cinderella reacts to her godmother’s question by saying yes, well I – I am sad. This is voiced by the storyteller as two tone units, TU 5 // 3 Yes / well I (TU 6) // 5 ˆ I / am / sad / ˆ, and one effect of this phonological choice is that Cinderella is presented as hesitant in her response to the godmother. Further, in impersonating Cinderella and voicing her answer to the godmother, the storyteller also uses a distinct affectual vocal profile for each tone unit: ‘misery’ for TU 5 and ‘perturbance’ for TU 6. In this way, Cinderella, construed phonologically as an affectual source, is coupled with both affectual meanings in this one message, with clear shifts in most of the vocal qualities features in the configurations from

‘mid’ in TU 5 to ‘high’ in TU 6 for pitch: height

‘narrow’ to ‘wide’ for pitch: range;

‘slow’ to ‘medium’ for tempo: stretches;

‘contracted’ to ‘expanded’ for tempo: syllables;

‘soft’ to ‘moderate’ for loudness;

‘standard’ to ‘precise’ for precision;

‘cry’ to ‘clear’ for voice quality;

‘_ (fused)’ to ‘ˆ silent’ for rests and

‘tremor’ to ‘_ (plain)’[24] for voice qualification.

In this way, while Cinderella is portrayed as being sad; she is also shown as reactive to the godmother’s questioning of her sadness. It is unclear how analysts could identify and track these finer shifts and layers in affectual meaning through the wording alone, without attending to the sounding potential. This example thus foregrounds the affordance of affectual vocal profiles to show shifts from one affectual meaning to another even within one single message. I move now from instances of inscribed affect realised in qualities to those realised in behaviours.

Behaviours worded in terms such as cry are seen as explicit realisations of affectual meanings, i.e. inscriptions of affect (Martin and White 2005). In this section, I explore three instances with the word cry to illustrate the sounding potential of vocal qualities configurations for realising affectual meaning in conjunction with verbiage. The Macquarie Dictionary of English provides three senses for the verb cry that could apply in the co-text and context of the instances explored below: “1. To utter inarticulate sounds, especially of lamentation, grief, or suffering, usually with tears; 2. To weep; shed tears, with or without sound; 3. To call loudly; shout”.[25] Considering these entries, cry can involve either the presence of sound, which can be loud, or the absence of sound; and it is mainly associated with a feeling of sadness. Loud cries, however, can be interpreted as signalling anger or frustration, such as when we shout, for example. The co-text and context in which the lexical item cry is used are therefore particularly relevant for interpreting its affectual meaning construed in a text.

The instances of cry in the example presented in Table 18 occurred as part of Cinderella’s reaction to the stepsisters and stepmother going to the ball while she had to stay at home. These instances were interpreted as ‘misery’ considering this co-text and context. However, when listening for affectual meanings, it becomes clear that the interpretative cues provided by the written transcription only gain extra clarity when we consider the vocal qualities selected by the storytellers. Table 18 presents three instances from three storytellers who select similar verbiage to construe Cinderella’s reaction in this moment in the story plot but not necessarily the same affectual vocal profile.

Examples of cry – coded as [Cinderella ≤ –happiness: ‘misery’ ≥ not going to the ball] in the verbiage. Audio files Table 18 – Lindy, Chris, and Maria in Supplementary Material.

| Tone unit analysis (Lindy) | pitch height | pitch range | tempo stretches | tempo syllables | loudness | precision | prominence transition | voice quality | rests | voice qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TU 1 // 1 ˆ And / then she / sat / ˆ | low | narrow | slow | expanded | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| TU 2 // 3 down / ˆ | low | narrow | slow | average | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| TU 3 and // 1 cried / ˆ ˆ ˆ | low | narrow | slow | average | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ ˆ ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| (Chris) | pitch height | pitch range | tempo stretches | tempo syllables | loudness | precision | prominence transition | voice quality | rests | voice qualification |

| TU 1 she // 3 sat on her / door step | low | narrow | slow | average | soft | standard | default | clear | _ (fused) | _ (plain) |

| TU 2 and // 1 she / cried / ˆ | high | wide | medium | expanded | loud | precise | staccato | clear | ˆ silent | tremor |

| (Maria) | pitch height | pitch range | tempo stretches | tempo syllables | loudness | precision | prominence transition | voice quality | rests | voice qualification |

| TU 1 // 1 Why are you / cry ing? / ˆ | mid | medial | medium | average | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

| TU 2 // 1 asked the / fairy / god mother | low | medial | medium | average | soft | standard | default | clear | ˆ silent | _ (plain) |

-

Cells are filled with different colours to show different affectual vocal profiles. Light blue is used for ‘misery’, red is for ‘displeasure’, while pink is for ‘affection’. TU 3 by Lindy includes the conjunction and before the double slants (//) that show the beginning of the tone unit to prioritise understanding of information units.

Even though the three storytellers featured in Table 18 couple Cinderella with a negative feeling in the verbiage, the multi-stratal interpretative cues provide further information that clarifies the type of negative feeling in the first two instances. Further, they offer additional information related to the affectual sources in Maria’s performance.

The only case where ‘misery’ is inscribed in cry and realised vocally by the affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’ is the first one. Lindy’s TUs 1 to 3 realise one affectual meaning where Cinderella is portrayed as the emoter of a feeling of ‘misery’. This interpretation matches the co-text and context of the story where Cinderella is left behind, feeling sad as she is not able to go to the ball. A similar reaction is portrayed by Chris as he describes Cinderella sitting on her doorstep, a sign of defeat and exhaustion after working hard to help the stepsisters get ready, only to be left behind. This negative feeling invoking ‘misery’ through the construal of experiential information is reinforced by Cinderella’s following action: she cried in Chris’s TU 2. However, when we factor in sound we find that, contrary to this expectation, the affectual vocal profile selected by the storyteller couples Cinderella with a feeling of frustration at how unfair her situation is. There is a clear shift in the vocal qualities features selected by Chris, moving from an affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’, clustering the features of ‘low’, ‘narrow’, ‘slow’, ‘average’, ‘soft’, ‘standard’, ‘default’, ‘clear’, ‘_ (fused)’, and ‘_ (plain)’ in TU 1 to a profile for ‘displeasure’,[26] with the bundle of ‘high’, ‘wide’, ‘medium’, ‘expanded’, ‘loud’, ‘precise’, ‘staccato’, ‘clear’, ‘ˆ silent’, and ‘tremor’ in TU 2. Looking back into the co-text in which the TU takes place, this interpretation of a displeased Cinderella becomes plausible and even more explicit as Chris continues the story, She’d so much wanted to go to the ball. It seemed so unfair. What had she done? She’d tried so hard. Even though both interpretations of the experiential information (And then she sat down / she sat on her doorstep) and of the verb cried as ‘misery’ or ‘displeasure’ can be justified for Cinderella at this point in the story, only ‘misery’ was considered by the analyst when coding the written transcription of the performances.

The third instance of the word cry shown in Table 18 exemplifies a slightly different case where the affordances for affectual vocal features for showing affectual sources and meanings might not necessarily coincide with those inscribed in the verbiage. In this case, Maria creates a context in which the godmother appears and asks Cinderella about the reasons why she is crying in “Why are you crying?” asked the fairy godmother. While the wording, crying, tells us how Cinderella is feeling, the vocal profile shows us how the godmother is feeling. As we interpret the whole ensemble in the co-text and context of the story in combination with all the interpretative cues provided by the storyteller, the godmother is coupled with a feeling of ‘affection’. This interpretation is strengthened when we compare the affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’ and ‘affection’.

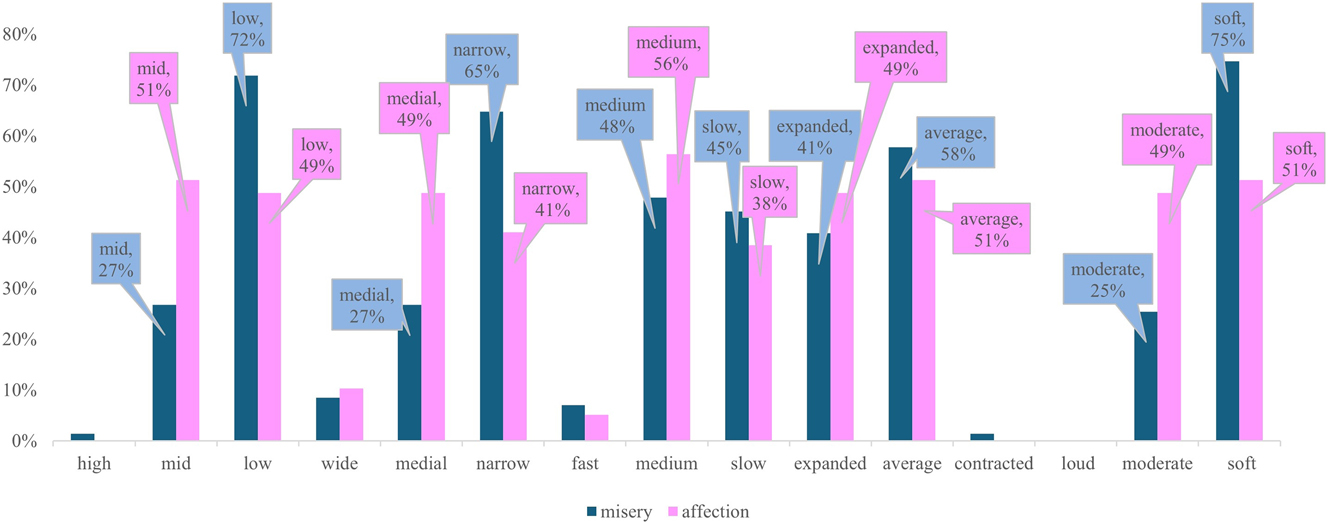

While the affectual vocal profiles described in Table 14 for ‘misery’ and ‘affection’ show similarities, zooming into the slight differences between some of the vocal qualities choices in the profiles as shown in Figure 6 below allows us to see how the tendencies described in the affectual vocal features can be used as a guideline to name and explain the slight differences we perceive as listeners.

Comparing choices in pitch, tempo and loudness for ‘misery’ and ‘affection’.

Figure 6 shows the frequency of occurrence for the dimensions pitch (height and range), tempo (stretches and syllables) and loudness for ‘misery’ (in blue) and ‘affection’ (in pink). Each of these 5 systems of vocal qualities consist of 3 points in the horizontal series which are combined with percentages in the vertical axis. In the case of ‘misery’ and ‘affection’, the contrast in pitch: height, ‘low’ for ‘misery’ and ‘mid’ for ‘affection’, in pitch: range ‘narrow’ for ‘misery’ and ‘medial to narrow’ for ‘affection’, and in tempo: stretches, ‘medium to slow’ for ‘misery’ and ‘medium’ for ‘affection’, as shown in the graph, can be used to describe those slight but stable differences that we perceive as listeners and respond to with our interlocutors. For example, although ‘low’ pitch by itself does not distinguish ‘misery’ from ‘affection’, since either affectual meaning can correlate with ‘low’ pitch, it appears to be a more important vocal profile component for ‘misery’ than ‘affection’, where ‘mid’ pitch is just slightly more frequent than ‘low’ pitch.

However, as relevant and enlightening as being able to name and explain these variations in vocal qualities may be, these differences in meaning can only be explained when we consider the co-selection of affectual vocal profiles with verbiage in a specific co-text and context. In the case of Maria’s vocal feature selections analysed for Table 18, interpreting an affectual vocal profile as indicating ‘affection’ for Cinderella makes sense when we consider the tenor relationship between Cinderella and her godmother, but as I have already explained, and illustrated in Table 17 with Jill’s TU 4, the tenor variable on its own cannot predict the choices a speaker would make. This observation reinforces the argument put forward in this paper that there is a need to consider the interplay of semiotic resources available in spoken language when interpreting and explaining how we communicate emotion. This argument has proved particularly productive when interpreting experiential meanings as enacting affectual meanings.

Interpreting experiential meanings as expressions of affectual meanings involves familiarity with cultural embodied experiences that we recognise as signals of a certain emotion. I focus now on two examples that reinforce the affordance of affectual vocal profiles to explicitly realise affectual meanings which are otherwise indirectly hinted in the verbiage. The first instance presented in Table 19 shows how the experiential information construed in But she had no mother because the rich man’s wife had died realises an invocation[27] for [Cinderella ≤ t, −happiness: ‘misery’ ≥ her mother’s death] since in the western culture where this story is being performed and interpreted, the death of one’s mother is considered one of the saddest events in most people’s lives. This invocation is congruently realised by the affectual vocal profile for ‘misery’ as can be heard in the example in Table 19.

Example of verbiage and affectual vocal profile congruent realisation for [t, −happiness: ‘misery’]. Audio file Table 19 in Supplementary Material.