Abstract

The impersonation of a character’s voice is a canonical resource in comedic parody, allowing comedians to impersonate characters and establish a plurality of perspectives with varying degrees of alignment to the audience’s collective values. Although phenomena such as mimicry and ventriloquism are often mentioned anecdotally, this area remains underexplored within phonology, despite being occasionally addressed in studies of impersonation from other disciplines. This study presents a social semiotic analysis of how features of a comedian’s vocal sound semiotics including phonology and voice quality intersect with impersonation and humour in a stand-up comedy text. Employing a systemic functional linguistics-based paralanguage framework, we characterize impersonation as a mechanism realized by the convergence of particular features across semiotic modes, with phonology playing a central role renovated Tenor model is then applied to describe how meanings realized by the comedian are negotiated with the audience to create humour. The findings indicate that vocal sound semiotics plays a crucial role in nuancing the negotiation of meanings with stand-up comedy audiences, affording the comedian a rich resource for creating humour. Specifically, the comedian alternates between a “harsher” voice quality, associated with an impersonated persona, for building humorous tension, and a “warmer” voice quality associated with a more “authentic” authorial persona so as to diffuse this tension; they thus calibrate tension to remain humorous and sustain solidarity and rapport with the audience.

1 Introduction

Impersonating a character’s voice is central to comedic parody, offering comedians a way to present multiple perspectives and thereby “act out” humorous scenarios. While often discussed in relation to mimicry and ventriloquism in the field of humour studies, this topic remains largely unexplored within phonology or interpersonal linguistics, despite its substantial relevance to these areas. This article presents an analysis of a stand-up comedy text that combines the social semiotic models of sound semiotics and paralanguage with the recently renovated systemic functional linguistic (SFL hereafter) model for Tenor so as describe the role of intermodal impersonation in creating humour. Particular focus is directed to the role of phonology and voice quality in realizing instances of impersonation and correlating these with shifts in the Tenor relations between the comedian and the audience.

This article will begin in by situating itself within relevant fields of study (Section 2). Section 3 will outline the theoretical frameworks employed, beginning in Section 3.1 with relevant systems and features of SFL sound semiotics, in particular phonology and voice quality. Section 3.2 will summarize the relevant areas of Doran et al.’s (2025) renovated Tenor model. Section 3.3 will present the model for describing intermodal impersonation elaborated in Logi (forthcoming). Section 4 will outline the method and dataset employed. Section 5 will step through analysis and discussion of the dataset, and Section 6 will conclude the article.

2 Literature review

The focus of this article sits at the intersection of three areas of study: sound semiotics, stand-up comedy, and SFL systems for interpersonal semiosis. Sound semiotics examines how sound acts as a system of signs, drawing from traditions including social semiotics, multimodal discourse analysis, and sound studies. Within social semiotics, van Leeuwen (1999) formalized the study of sound’s semiotic features such as pitch, volume, rhythm, and timbre. More recently, work such as Kress (2010), O’Halloran and Fei (2014), and Jewitt et al. (2016) have shown how sound contributes to meaning alongside other modes in multimodal settings, especially in film, television and other broadcasted multimodal formats. The branch of sound semiotics most relevant to this article is that concerning the semiosis of acoustic features of the human voice, referred to here as vocal sound semiotics. This branch has been the focus of work in recent years by Martin and Zappavigna (2019), Ngo et al. (2021), Ariztimuño et al. (2022), and Spreadborough (2022), which elaborate more delicate systems for analyzing and interpreting the semiotic potential of the human voice across genres and registers. One dynamic that has only received limited attention is the role of vocal sound semiotics in performative texts such as stand-up comedy, where performers change their voice quality so as to impersonate other personae. Logi (forthcoming) outlines which features of voice quality are recruited by comedians to enact impersonations; however, while this work establishes a useful analytical framework for the analysis of vocal sound semiotics in instances of impersonation, it correlates the semiotic potential of these resources with features of the SFL affiliation model (Knight 2010), and not with the newly proposed Tenor model (Doran et al. 2025). This article extends the explanatory power of Logi’s (forthcoming) framework by exploring how it interacts with various features of Doran et al.’s Tenor systems.

The choice of stand-up comedy as site of study is also a valuable one. Stand-up comedy, which originated in the late nineteenth century within American popular theatre, vaudeville, and burlesque, has developed into a popular and diverse form of entertainment (Mintz 1985). Especially in recent decades, the introduction of radio, television, and digital streaming media has enabled comedians to reach audiences beyond traditional venues. In 2018, The Economist reported that Netflix was producing and releasing a new comedy special each week,[1] while a recent Bloomberg article notes that the stand-up comedy industry has tripled over the past decade.[2] These developments have influenced the economic opportunities, creative approaches, and cultural influence of stand-up comedy, rendering stand-up comedy texts valuable sites of enquiry, as the analysis of the jokes comedians make and how an audience laughs at these can shed light on the prevailing social values of a culture (Mintz 1985). Within the broader field of research into stand-up comedy, this article draws on recent work in the social semiotic tradition, principally Logi (2021; forthcoming).

By combining the analytical framework of sound semiotics with that of Doran et al.’s (2025) Tenor model and applying these to a stand-up comedy text, this article illustrates how an integrated intermodal social semiotic approach can give a principled account of how linguistic and paralinguistic resources are employed by comedians to negotiate social values and humorously bond with their audiences in stand-up comedy performances.

3 Theoretical foundations

3.1 SFL sound semiotics

This article describes the semiosis of spoken language within the social semiotic theoretical framework of SFL as developed by Halliday (1978). SFL linguistic theory emphasizes the inherently social nature of language, asserting that acts of meaning can only be understood within their social context. According to this perspective, meaning arises from the choices individuals make within a network of semiotic options, modeled in SFL as system networks. SFL views language as a form of social semiotic practice, with linguistic resources simultaneously shaping and mirroring the social structures in which they are used. Consequently, analyzing texts provides a window into the social realities of the people involved in producing and interpreting them.

Informed by the theoretical architecture of SFL and building on work in paralanguage outside SFL (Kendon 1997; McNeill 1992), the SFL paralanguage model (Ngo et al. 2021) describes the semiosis of gesture and body language. The specific regions of theory relevant to this article centre around the expression and meaning of spoken language. These are covered by the SFL model of phonology and the voice quality system. The SFL phonology model developed by Halliday (1967, 1970), Halliday and Greaves (2008), and Smith and Greaves (2015) interprets the meaning potential of spoken language as complementary to language, furnishing a system to describe the semiosis of physical aspects of spoken language. The SFL phonology model describes spoken English through systems of rhythm, salience, tone, tonality, and tonicity. A full account of these systems is beyond the scope of this article, however a summary is helpful in understanding the principles governing the division of the dataset into tone groups, which in turn are the relevant unit of analysis when accounting for the convergent semiosis of language and paralanguage.

The rhythm of English (a stress-timed language, as defined by Abercrombie 1965; Pike 1945) emerges from the alternation between more and less prominent syllables. This prominence is termed salience (Halliday 1967, 1970) with a salient syllable referred to as Ictus, and a non-salient syllable referred to as Remiss. Salience occurs via “the lengthening of a syllable relative to preceding syllables, a distinct jump up or down in pitch, or by a syllable falling in beat position within an established rhythm – or some combination of these features” (Ngo et al. 2021: 71). The rhythm of English, typically isochronous, is governed by the mostly regular interval between salient syllables. This creates a “beat” in spoken language, similar to that of music, with syllables synchronised with the beat heard as salient (Ngo et al. 2021). Rhythm then allows stretches of spoken language to be divided into segments, with a salient syllable marking the beginning of a foot. While a regular beat is common, speech frequently varies in rhythm, with shifts construing meaningful choices in the rhythm system (cf. Couper-Kuhlen 1993; van Leeuwen 1999, 2025).

Tone refers to the pitch contour of a tone group, which typically correspond to particular discourse semantic features. Tonality describes how pitch contours segment spoken English into tone groups, dividing information into “chunks” or waves. Tonicity indicates the placement of the major pitch movement in a tone group, typically on the Tonic syllable, which gains prominence. These systems describe how phonology interacts with meaning in spoken language and its convergence with other paralinguistic modes; in the SFL model, facial and gestural paralanguage is interpreted as converging with the meaning of spoken language and phonology in the co-occurring tone group (Ngo et al. 2021). The dataset analyzed here is not annotated for all phonological features, however coding for these was necessary to divide it into tone groups, as shown in Table 1.

Summary of parametric voice affect features (adapted from Ngo et al. 2021: 130).

| Measure | Parametric descriptor | Phonetic feature described |

|---|---|---|

| Time-related measures | ||

|

|

||

| [tempo] | (faster/slower) | The speed of speech and can be quantified as syllables per second |

| [duration] | (longer/shorter) | How long individual syllables are held |

|

|

||

| Frequency-related measures | ||

|

|

||

| [pitch level] | (higher/lower) | Measured in the physical transmission of sound through the air as hertz (Hz) |

|

|

||

| Energy-related measures | ||

|

|

||

| [loudness] | (louder/softer) | Strength in decibels (dB) |

|

|

||

| Complex time-frequency-energy related measures | ||

|

|

||

| [pitch-range] | (wider/narrower) | Variations in pitch (between highest and lowest) |

| [tension] | (tenser/laxer) | The degree to which “the walls of the throat captivity dampen the sound less than they would in a relaxed state” (van Leeuwen 1999: 130) |

| [roughness] | (rougher/smoother) | Pressure on the vocal cords that produces a harsher voice quality |

| [breathiness] | (breathier/clearer) | How much aspirated air is mixed with voiced sounds during speech |

| [vibrato] | (more vibrato/plainer) | The interaction of rapidity of tempo and of fluctuations in energy and pitch |

| [nasality] | (more nasal/more non-nasal) | The degree to which air is released through the nasal cavity. |

Complementing the phonology of speech, the voice quality system first outlined in van Leeuwen (1999) describes the materiality of a the human voice across four dimensions of spoken language acoustics: “time-related measures”, “intensity-related measures”, “measures relating to fundamental frequency” and the combination of these, known as “time-frequency-energy measures” (Ngo et al. 2021: 129). These parameters, their associated features and realizations are outlined below in Table 1.

van Leeuwen (1999) correlates these features with various interpersonal meanings. Especially relevant to the analysis carried out here are the effect of [tenser] voice quality: “The sound that results from tensing not only is tense, it also means ‘tense’ – and makes tense” (van Leeuwen 1999: 131). Other features will be described and interpreted in the analysis below as needed. Expanding on van Leeuwen’s (1999) framework, Ngo et al. (2021) describe how particular configurations of voice quality measures realize features of the voice affect system, shown in Table 2.

Features of voice affect and their voice quality realization (adapted from Ngo et al. 2021: 131).

| voice affect feature | Realization | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spirit | up | affection | less fast, short, high, less loud, wide, less tense, more vibrato, smooth, breathy, non-nasal |

| cheer | fast, short, high, loud, wide, tense, vibrato, smooth, non-breathy, non-nasal | ||

| down | misery | slow, longer, lower, softer, lax, narrow, vibrato, smooth, breathy, nasal | |

| ennui | slower, longer, lower, softer, lax, narrow, vibrato, smooth, breathy, less nasal | ||

| threat | fear | fast, short, high, loud, wide, tense, smooth, breathy, vibrato, non-nasal | |

| anxiety | less fast, less short, less high, less loud, wide, less tense, smooth, breathy, vibrato, non-nasal | ||

| anger | fast, shorter, high, loud, wide, tense, breathy, rough, vibrato, non-nasal | ||

| Surprise | fast, short, loud, high, wide, smooth/rough, breathy, vibrato, non-nasal | ||

Spoken language analysis such as that carried out in this article typically involves transcribing audio recordings into a written format with annotated phonological features. Tools like acoustic visualization and analysis software Praat can partially visualize features such as salience and pitch contour. However, as van Leeuwen (2015) points out, isochrony – the perception of equal timing – is not objectively measurable but must be studied auditorily by analyzing the “beat” of speech. Accordingly, the most accepted method for phonological analysis is subjective researcher coding. This also applies to analysis of voice quality, where features are determined relative to co- and contextual baselines (hence the comparative lexis in the realizations of features in Table 3). In other words, if a feature of a speaker’s voice quality, say volume, is relatively constant for the majority of a text, but then intensifies markedly for a stretch, that stretch would be marked as relatively more intense, i.e. “louder”. Table 3 shows coding for voice quality for tone groups #14–15, which will be returned to in the analysis.

Coding of tone groups #14–15.

| Tone group # | Verbiage | voice quality |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | I don’t know if that’s the best thing to say in a speciala is | [laxer][slower] |

| 15 | Oh yeah laugh all you want | [tenser][faster] |

-

a“Special” here refers to a full length (approximately 60 minutes) stand-up comedy show recorded for and published on media streaming platform Netflix.

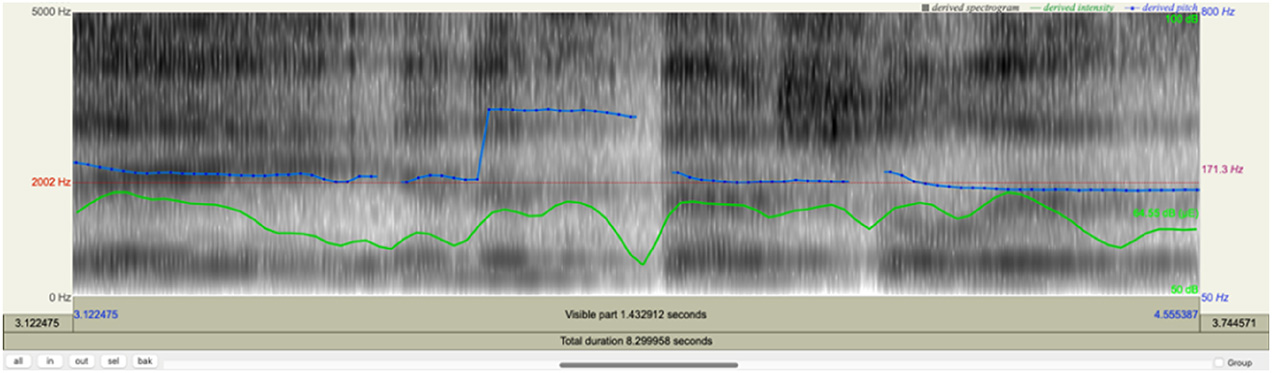

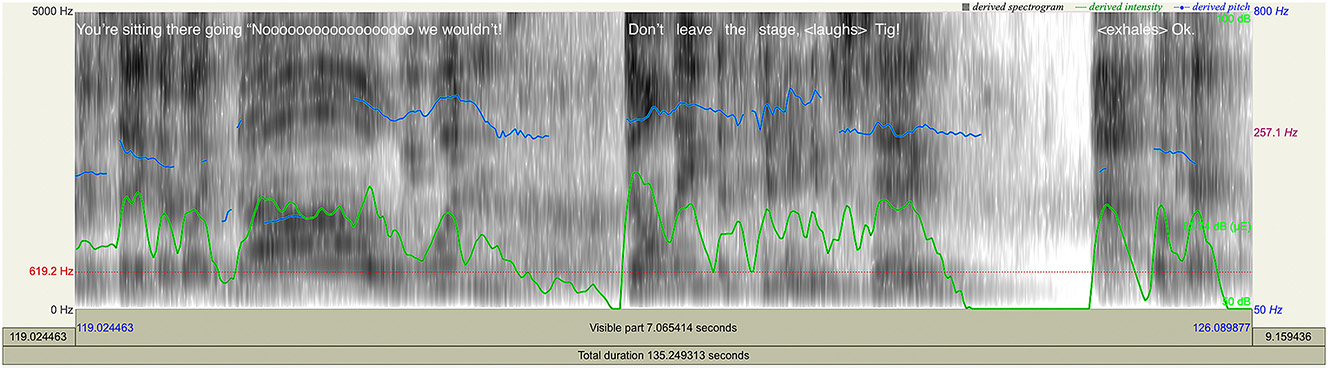

The coding in Table 4 only refers to two of the voice quality parameters (laxer/tenser; slower/faster) as these were the only two found to shift between the two tone groups; for the sake of clarity and brevity, only parameters whose features have changed will be annotated. While the primary resource for perceiving this change was subjective researcher coding, below is shown the Praat spectrographic analysis of this stretch of the text in Figure 1, with a transcript of the spoken language added to show which acoustic features correspond to which lexis.

Spectrogram close-up of [laxer/tenser] harmonics.

| Verbiage | Spectrogram analysis |

|---|---|

| Say in a special is |

|

| Oh yeah laugh all you want |

|

-

top blue line = pitch; bottom green line = volume.

Praat spectrogram for tone groups #14–15. Note: top blue line = pitch; bottom green line = volume.

The spectrogram in Figure 1 shows how the voice quality for the first tone group, “I don’t know if that’s the best thing to say in a special is” shifts compared to that of the second tone group “Oh yeah, laugh all you want”. Specifically, the harmonics shown in the spectrogram reveal a shift from [laxer] to [tenser]. To visualize this more clearly, we must zoom in more closely on the spectrogram analysis of a 1.5-second-long section of each tone group, as shown below in Table 4.

Here we can see how the harmonics (horizontal bands in the spectrogram) for “say in a special is” are slightly less dense and less dark than those for “oh yeah laugh all you want”, illustrating [laxer] voice quality in the former verbiage and [tenser] voice quality for the letter (Ngo et al. 2021). In combination with the [faster] tempo coded for the second tone group, as well as the meaning of the language itself, this suggests a shift in voice affect from a baseline towards [threat: anger]. These shifts in voice quality and associated voice affect features can be recruited by the comedian to shift between personae, and coordinate with realizations of Tenor features that contribute to humorous bonding.

3.2 Tenor through the lens of negotiated social relations

In SFL, Tenor refers to the social relationships between interactants in a communicative situation, including relative roles, status, and degree of formality. It describes interpersonal meaning and language choices (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014; Martin 1992) at the registerial stratum, forming part of the context of situation alongside field and mode. Doran et al.’s (2025) renovated Tenor model aims to complement the existing description of Tenor in SFL by providing a framework for describing how meanings are negotiated in texts to enact social relations. This is relevant to this article as it integrates features of the SFL affiliation (Knight 2010) model relating to humorous bonding into the broader model for Tenor, thus allowing for analysis and description of how humour functions alongside other interpersonal resources within a register.

While the model can be used to describe established Tenor variables including power/status and solidarity/contact (Eggins and Slade 2006; Martin 1992; Poynton 1990), most relevant to the aims of this article is the elaboration of a more comprehensive framework for describing orientation to affiliation, which builds on Knight’s (2010) affiliation model for describing how interactants in spoken discourse enact and negotiate values so as to establish bonds of shared identity. To this end, Doran et al.’s renovated Tenor model encompasses three simultaneous systems that describe how meanings are put forward and negotiated in discourse:

positioning, concerned with resources for putting forward (tendering) and responding to (rendering) meanings;

orienting, concerned with how meanings are related to each other and organized into coherent networks of meaning; and

tuning, concerned with resources for adjusting negotiated meanings.

These systems will be briefly outlined in the subsections below, and then more fully described when applied via analysis in the following section.

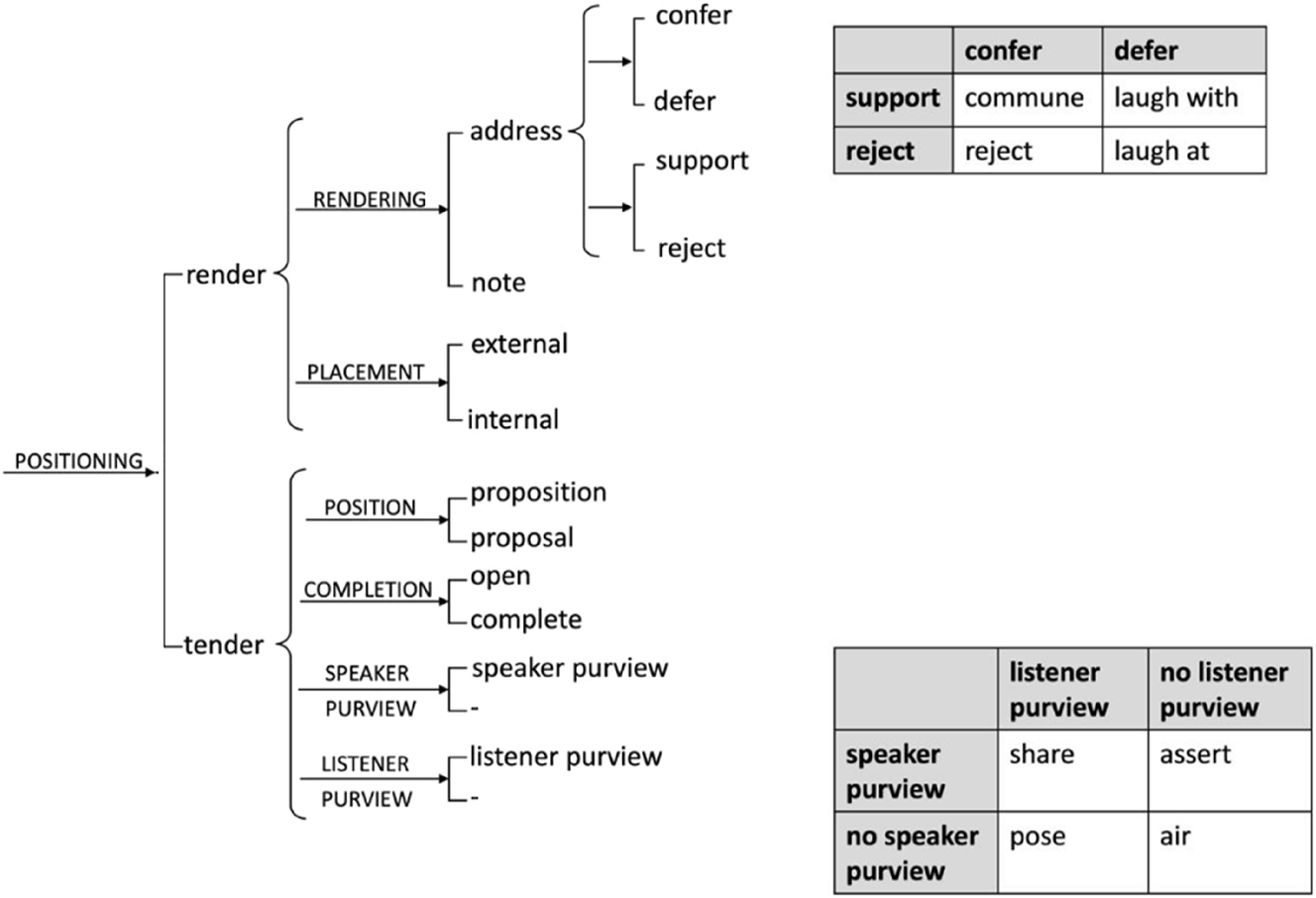

positioning is the primary system for describing how meanings are negotiated in discourse, encompassing the two essential options in interactive exchanges for putting meanings forward (tendering) and responding to them (rendering). The systems of tendering provide a description of the various resources for “how people tender meanings so as to position others to respond – to support or reject, to do something or to say something, or to tender a whole new set of meanings” (Doran et al. 2025: 55). More delicate features from this system are not relevant to the analysis conducted here, so it is sufficient to define tendering as the feature realized when the comedian enacts meaning for the audience to render (respond to). Rendering, and in particular defer features, are central to how meanings are negotiated in stand-up comedy. Rendering options are distinguished between giving a supportive or rejecting reaction, together called addressing, or simply noting meanings without indicating any support or rejection and addressing them. In terms of addressing, there are four primary choices, described by two simultaneous systems of confer/defer and support/reject. The confer/defer options distinguish between resources for directly supporting or rejecting tendered meanings, for instance with responses of agreement or negation, and resources for indirectly supporting or rejecting meanings through laughter or other manifestations of non-seriousness. Accordingly, non-serious deferral responses can either laugh with tendered meaning, typically signaling a deferral of the tendered meaning but an implicit communion around a bond shared with the tenderer. Alternately a renderer can laugh at tendered meanings, signaling a rejection of the tendered bond with no implicit communion with the tenderer. The full positioning system is presented in Figure 2.

positioning system network.

Orienting is concerned with resources that describe how meanings are related to each other and organized into coherent networks of meaning. This develops and formalizes Knight’s conception of bond networks and offers a linguistic perspective on the concept of axiological constellations in Legitimation Code Theory (Doran et al. 2025). The system network of the orienting system is shown in Figure 3.

orienting system network.

Beyond options at the first layer of delicacy between orienting meanings or not, the orienting system then distinguishes between repositioning, whereby proposals are negotiated as propositions and vice-versa, and arranging, which obtains two further systems for nuancing meanings with more detail about their relationships to other meanings ([configuring]) and their source and target ([situating]). Within the configuring system, negotiated meanings can be either likened, where they are arranged as in some sense similar to each other or aligned in support of a position, opposed, where meanings are arranged as being contrasting or on opposing sides of a position, or encapsulated, where meanings are arranged into hierarchies of super/subordinance, with higher level, more generalized positions being supported and elaborated by more specific meanings. Within the situating system, meanings are either attributed to a specific perspective such as a quoted voice ([sourcing]) or addressed to a particular audience ([convoking]). The [sourcing] feature is especially relevant to the analysis undertaken in this article as it accounts for how values are attributed to alternate perspectives. These are typically realized in this dataset via extra-vocalising linguistic resources such as the discourse semantic feature of [engagement: attribute] converging with paralinguistic resources such as voice quality/affect and facial affect to realize intermodal impersonation.

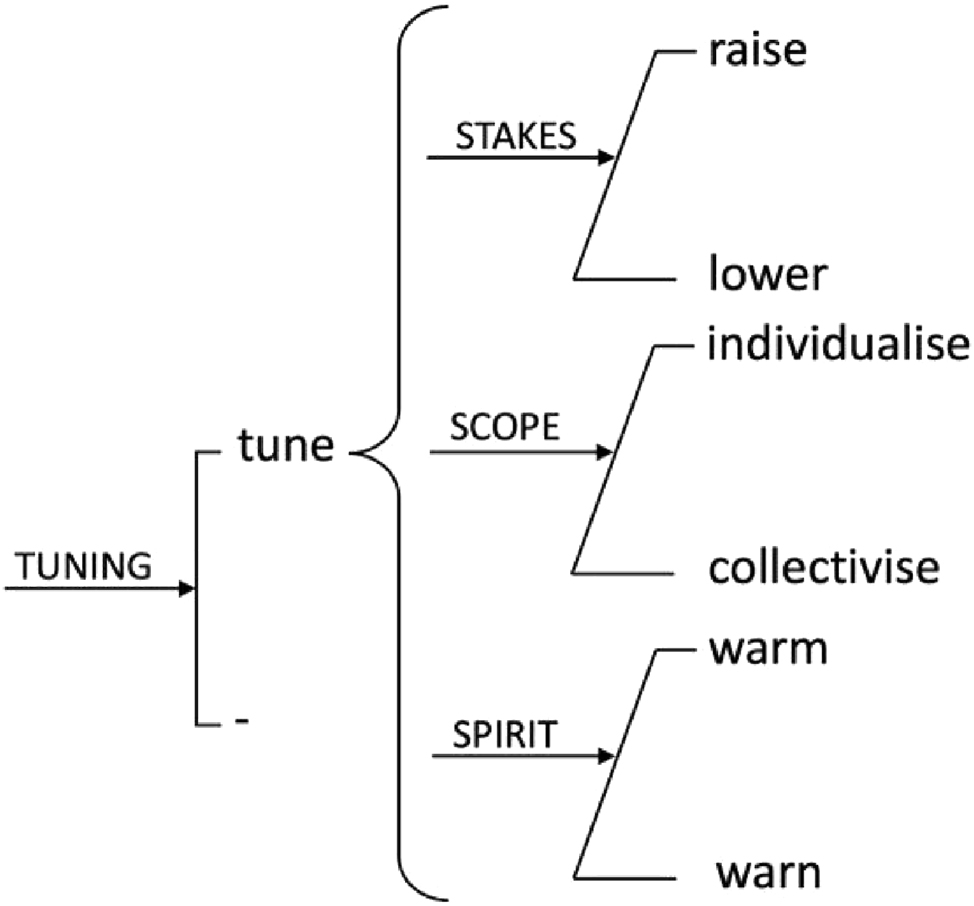

Tuning describes further options for nuancing negotiated meanings, raising or lowering the stakes of what is under negotiation, broadening or narrowing the scope of who it relates to and calibrating the spirit in which meanings are put forward. Of these, only the spirit [3] system is relevant here, which describes resources for calibrating a position to be read more or less favorably and encompasses the role of paralinguistic modes such as facial affect and phonology. The tuning system network is shown in Figure 4.

Tuning system network.

3.3 Impersonation in stand-up comedy

The analytical frameworks for describing sound semiotics and Tenor described above provide a toolkit for exploring the specific phenomenon which is the focus of this article: the use of intermodal impersonation in stand-up comedy as a resource for humour via audience-comedian bonding. Examples of this found in the dataset will be stepped through in the following section; here a brief summary of SFL work on intermodal impersonation is presented. The model for intermodal impersonation in stand-up comedy as developed by Logi (2021, forthcoming); and Logi and Zappavigna (2021) comprises a set of linguistic and paralinguistic features most commonly enacted to realize instances of impersonation. A full account of these elements is beyond the scope of this article, but some features require explanation before proceeding to the analysis of the dataset. In terms of the linguistic discourse semantics of impersonation, instances where a comedian embodies an impersonated persona are defined as realizations of the heteroglossic features within the SFL Appraisal model’s engagement system of [attribute: acknowledge/distance]. This captures the role of resources for projected speech such as projected verbiage attributed to a participant in a Verbal process clause. When converging with paralinguistic resources, instances of engagement [attribute: acknowledge/distance] are coded as realizing intermodal impersonation. Table 5 summarizes the paralinguistic features presented in Logi (forthcoming) that typically converge with language to realize intermodal impersonation.

Paralinguistic features converging to realize intermodal impersonation (adapted from Logi forthcoming).

| Paralinguistic resource | Feature corresponding with comedian embodying authorial persona | Feature converging with intermodal impersonation |

|---|---|---|

| paralinguistic contact | [demand] | [offer] |

| paralinguistic involvement | [frontal] | [oblique] |

| transition in place | [stasis] | [motion] |

| paralinguistic ideation and somasis | – | Indexing ideational meaning relating to impersonated persona |

| paralinguistic deixis (gaze; body parts) | [actual: other] to audience | [actual: other] tracking ideational meaning relating to impersonated scenarios |

| Paralinguistic realizations of affect (voice; facial) | Paralinguistic affect consistent with authorial persona’s verbiage | Shift in paralinguistic affect converging with verbiage attributed to impersonated persona |

| voice quality | authorial persona’s baseline voice quality | Shift away from authorial persona’s baseline voice quality |

| Emblems | – | Realizations of paralinguistic emblems (i.e. gestures, voice quality) associated to a particular referent |

Table 6 references nine different resources converging to realize instances of intermodal impersonation, however as noted in Logi (forthcoming), it is not essential that features of all of these converge to realize instances of impersonation. While these instances typically comprise features from more than one resource, in stretches of discourse where impersonated personae have already been established, it is possible for realizations of even one of these features to index a shift in persona. As the analysis below will illustrate, in the dataset analyzed here often only voice quality and voice affect features function to construe shifts in persona.

Transcript of dataset.

| Tone group # | Verbiage; <paralanguage gloss> |

|---|---|

| 1. | Before I started doing stand-up, |

| 2. | professionally full-time, |

| 3. | I uh, |

| 4. | I did temp work, |

| 5. | and I had this one job that went really, really well. |

| 6. | And they highly recommended me |

| 7. | to another temp job. |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 8. | Listen, |

| 9. | laugh all you want. |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 10. | I’m not trying to be braggadocious. |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 11. | I’m just presenting facts at this point. |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 12. | Ok? |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 13. | But, ah […] <smiles> |

| 14. | I don’t know if that’s the best thing to say in a special, is |

| 15. | “Oh, yeah, laugh all you want.” |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 16. | So it’s like, |

| 17. | “oh, I guess that’s all you wanted to laugh, all right”. |

| 18. | But, ah, |

| 19. | so it did. |

| 20. | It went really, really well. |

| 21. | They highly recommend me to the other one, |

| 22. | and I show up to the next job, |

| 23. | just like, |

| 24. | “Hey, I’m Tig, |

| 25. | you probably heard a lot about me.” |

| 26. | And I was greeted by the owner of the company |

| 27. | just immediately down to business. |

| 28. | “Bathroom’s over here, |

| 29. | mail goes out every day at four, |

| 30. | this is your desk”. |

| 31. | And I was immediately realizing, |

| 32. | “this is not gonna be a good time”. |

| 33. | And that entire week that I worked there […] |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 34. | It was a temp job! <smiles> |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 35. | <laughing> ‘Temp’ is short for temporary! |

| 36. | They asked five days of me, |

| 37. | and I delivered. <frowns> |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 38. | But that ent- |

| <audience laughter, applause> | |

| 39. | <smiling> Thank you! |

| <audience laughter, applause, cheering> | |

| 40. | <smiling, waves to audience > Thank you! |

| 41. | Good night! <turns, walks to stage back> |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 42. | <voice tense > You guys would have been fine with that, if I just left. <frown> |

| 43. | All that build-up |

| 44. | and then I’m like |

| 45. | “hey I was great at my temp-job, |

| 46. | good night!” <frown> |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 47. | <smile>, <frown> <voice exasperated > Now you’ve lost your sense of humour |

| 48. | and you’re sitting there going |

| 49. | “No we wouldn’t! |

| 50. | Don’t leave the [comedian laughs] stage, |

| 51. | Tig!” [exhales] |

| 52. | <serious> Ok. |

| <audience laughter> | |

| 53. | You’ve convinced me |

| 54. | to stick around |

| <audience laughter>. | |

| 55. | I’ll go ahead […] |

| 56. | and finish my story. |

4 Methodology

The methodology used in this article is qualitative, multimodal discourse analysis (MDA) informed by the SFL theory (Martin 1992; Ngo et al. 2021) and focusing on discourse semantic systems described by Martin (1992) and Martin and White (2005). To address the multi- and intermodal characteristics of semiosis in the analyzed dataset, the SFL discourse analytic framework is integrated with the MDA model as developed by Kress (2012), Kress and van Leeuwen (2006), Ngo et al. (2021), Painter et al. (2013), and van Leeuwen (1999, 2015, 2025). A coding rubric for analysing the dataset was elaborated from this framework and applied to the dataset. Coding was conducted by a single researcher (the author) and thus is internally consistent, and where possible vocal sound semiotic features were checked against spectrographic imaging to confirm subjective coding (see Section 3.1).

The dataset analyzed in this article comprises a 2 min and 17 s segment from a 2018 stand-up comedy performance by United States comedian Tig Notaro entitled Happy to be here. [4] This text and excerpt was purposively selected as it illustrates how vocal sound semiotics functions to nuance interpersonal relations with the audience and is relatively widely accessible, allowing many readers the possibility to view the text and thereby follow the analysis more thoroughly.

To give the reader a sense of how humour unfolds across the analyzed segment of the text, a transcript of the dataset is presented in Table 6. The excerpt is divided by tone groups and annotated with simplified glossing of paralinguistic features in angle brackets (<>).

5 Analysis and discussion

This section will demonstrate how vocal sound semiotic resources play a vital role in realizing instances of intermodal impersonation in this dataset and thus contribute significantly to creating instances of humorous bonding between the comedian and audience. Most germane to the focus of this article, voice quality and voice affect resources realize features of the tuning system, which allows for a principled description of how comedians employ interpersonal resources such as linguistic graduation and paralinguistic affect to nuance the level of tension generated by the meanings they tender. In addition, the application of the situating features of the orienting system describe how meanings can be attributed (sourced) and directed (convoked) to personae/communities, accounting for shifts between discrete perspectives associated with particular social values. Furthermore, the configuring features of the orienting system allow networks of related meanings to be elaborated from the negotiations within a text. Finally, the placement system accounts for how the comedian re-interprets the audience’s laughter to tender further humorous meanings, and the systems of purview offer a potential explanation for the role of the comedian’s intermittent, explicit solidarity with the audience as a resource for guiding audience renderings towards laughing with, rather than rejection.

In general terms, the humour in this excerpt largely stems from the tension between the shared expectations regarding the conventions of the stand-up comedy genre, and the comedian’s non-serious deviation from those expectations. These expectations centre around the genre’s primary social purpose of having the audience laugh as they implicitly bond with the comedian around shared meanings. Correspondingly, the comedian alternates between a more “authentic” authorial persona and a “joke” authorial persona doppelganger: the first is a “humorous” persona, who cleaves to the genre’s conventions and thus bonds and affiliates with the audience; the second we can describe as a “non-humorous” persona, who deviates from the conventions of the genre and thus distances and disaffiliates from the audience. Paradoxically, realizations of the “non-humorous” persona generate humour, as this persona deviates from the audience’s expectations of a comedian being humorous. For ease of reference across the following analysis, the segment is divided into stretches attributed to each persona, shown in Table 7.

Division of dataset by personae.

| Humorous authorial persona | Non-humorous persona |

|---|---|

| Before I started doing stand-up, professionally full-time, I uh, I did temp work, and I had this one job that went really, really well. And they highly recommended me to another temp job. <audience laughter> Listen, laugh all you want. <audience laughter> I’m not trying to be braggadocious. <audience laughter>, I’m just presenting facts at this point. <audience laughter> Ok? But, ah […] |

|

| <smiles> I don’t know if that’s the best thing to say in a special, is “Oh, yeah, laugh all you want.” <audience laughter> So it’s like, “oh, I guess that’s all you wanted to laugh, all right”. But, ah, so it did. It went really, really well. They highly recommend me to the other one, and I show up to the next job, just like, “Hey, I’m Tig, you probably heard a lot about me.” And I was greeted by the owner of the company just immediately down to business. “Bathroom’s over here, mail goes out every day at four, this is your desk”. And I was immediately realizing, “this is not gonna be a good time”. |

|

| And that entire week that I worked there […] <audience laughter> It was a temp job! |

|

| <smiles> <audience laughter> <laughing> ‘Temp’ is short for temporary! |

|

| They asked five days of me, and I delivered. <frowns> <audience laughter> But that ent- < audience laughter, applause> |

|

| <smiling> Thank you! <audience laughter, applause, cheering> <smiling, waves to audience > Thank you! Good night! <turns, walks to stage back> <audience laughter> |

|

| <voice tense > You guys would have been fine with that, if I just left. <frown> All that build-up and then I’m like “hey I was great at my temp-job, good night!” <frown> <audience laughter> |

|

| <smile>, | |

| <frown> Now you’ve lost your sense of humour and you’re sitting there going “Nooo we wouldn’t! | |

| Don’t leave the [comedian laughs] stage, Tig!” | |

| [exhales] <serious> Ok. <audience laughter> You’ve convinced me to stick around < audience laughter>. I’ll go ahead […] and finish my story. |

At the beginning of the segment (tone groups #1–7) the comedian says:

Before I started doing stand-up, professionally full-time, I uh, I did temp work, and I had this one job that went really, really well. And they highly recommended me to another temp job. <audience laughter>

Noteworthy here is that there do not appear to be any meanings tendered in the spoken language that would create the tension required for a laughing deferral response. The utterance is however followed by audience laughter, so it would seem to be the comedian’s paralanguage that is creating humour. Indeed, the comedian’s paralinguistic affect, realized primarily by voice affect, is noticeably devoid of resources suggesting [spirit: up] (faster tempo, louder volume, higher pitch level, wider pitch range), which typically accompany stretches of verbiage where a comedian relays the setup of a joke in their authorial persona; rather the comedian’s voice suggests [spirit: down: ennui] via slower tempo, lower volume, lower pitch and narrower pitch range. facial affect resources converge with this feature, as the comedian does not exhibit any [spirit: up] resources, thus realizing [neutral/serious] affect. In concert, these paralinguistic features suggest the characterization of the comedian’s non-humorous persona and thereby wrinkle with the audience’s expectations that the comedian’s aim is to bond with them. In essence, rather than being addressed by a persona who exhibits the paralinguistic behaviour expected from someone trying to establish humorous bonding, the audience is met by a persona who seems borderline bored/annoyed by talking to them. Therefore, in terms of features of the Tenor model, what seems to be under negotiation here is the realization of [spirit: warn] in the tuning system realized by negative ([spirit: down]) paralinguistic affect, which shifts the tone of the meanings tendered from inviting affiliation with the audience to rejecting it. However, the audience’s confidence that this seeming disaffiliation is jocular allows them to laugh with the comedian’s implied humorous persona and jointly defer this meaning – they thus bond with the humorous persona while distancing from the non-humorous persona. A summary of this analysis is shown in Table 8.

Analysis of tone groups #6–7.

| Tone group # | Verbiage | voice affect | facial affect | Persona | Tenor resource | Meanings tendered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | And they highly recommended me | [spirit: down: ennui] | [serious] | non-humorous | [spirit: warn] | comedian does not want to bond with audience |

| 7 | to another temp job. | [spirit: down: ennui] | [serious] | non-humorous | [spirit: warn] | |

| <audience laughter> | [laugh with]: comedian does not want to bond with audience | |||||

This dynamic is sustained in the following exchange (tone groups #8–13), as the non-humorous persona misinterprets the audience’s laughter and adopts a defensive and confrontational rapport with them:

Listen, laugh all you want.

<audience laughter>

I’m not trying to be braggadocious.

<audience laughter>,

I’m just presenting facts at this point.

<audience laughter>

Ok?

With “laugh all you want”, the comedian again departs from behaviour expected for the genre by (indirectly) negatively evaluating audience laughter, thereby clashing with one of the most intrinsic mechanisms for building rapport between comedian and audience: the comedian interprets the audience’s laughter as laughing at her, rather than with her. voice and facial affect realize [spirit: down] features, with the comedian’s flat voice quality continuing to suggest [ennui]. Again, this realises the [spirit: warn] feature which converges with the verbiage to tender the meaning, “comedian negatively judges audience for laughing”. In terms of meaning being negotiated, “laugh all you want” is somewhat unspecific, as it constitutes a rejection of laughter, which is itself a less committed rendering resource. In lieu of the more committed verbiage in the comedian’s subsequent clause, “laugh all you want” is interpreted here as generalized rejection/negative attitude for the audience. Another round of audience laughter follows this utterance, confirming the audience’s confidence that the comedian is not in fact hostile to them while they laugh off the comedian’s defensive and confrontational behaviour. A summary of this analysis is shown in Table 9.

Analysis of tone group #9.

| Tone group # | Verbiage | voice affect | facial affect | Persona | Tenor resource | Meanings tendered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | laugh all you want | [spirit: down: ennui] | [serious] | non-humorous | [spirit: warn] | comedian does not want to bond with audience |

| <audience laughter> | [laugh with]: comedian does not want to bond with audience | |||||

With the next clause (tone group #10) “I’m not trying to be braggadocious”, the comedian tenders more specific meanings to be negotiated. As a realization of the Appraisal feature [engagement: deny], this verbiage implicitly also alludes to the alternate perspective, i.e. that the comedian was trying to be braggadocious. In light of the co-text, we can see how this perspective is attributed by the non-humorous persona to the audience – this persona has interpreted the audience’s first instance of laughter as indicating that they have interpreted the comedians’ verbiage as boastful. Once again, this bundle of meanings is laughed off by the audience, who continue to share the implicit meanings that the comedian’s hostility is in fact non-serious. A summary of this analysis is shown in Table 10.

Analysis of tone group #10.

| Tone group # | Verbiage | voice affect | facial affect | Persona | Tenor resource | Meanings tendered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | I’m not trying to be braggadocious | [spirit: down: ennui] | [serious] | non-humorous | [spirit: warn] | audience thought comedian was being braggadocious |

| <audience laughter> | [laugh with]: comedian does not want to bond with audience | |||||

Here we can begin to see the value of the orienting system’s arranging features in describing how meanings are negotiated and note how shifts in [sourcing] synchronize with shifts in paralinguistic features associated with particular personae. To begin, the realization of [deny] and thus the allusion to an alternate perspective serves to establish two, opposing positions ([arranging: configuring: opposing]): “the comedian was trying to be braggadocious” and “the comedian was not trying to be braggadocious”. These positions then form nodes in the networks of meaning being negotiated and to the two personae the comedian is impersonating: the comedian trying to be braggadocious links to associated meanings of domination and competitiveness, which are unexpected and inappropriate behaviors for a comedian in a stand-up comedy text and thus characterize the “non-humorous” persona, while the comedian not trying to be braggadocious is congruent with cooperation and solidarity, which align with the genre’s social purpose of having interactants affiliate around implicit, shared meanings and thus characterize the comedian’s more “authentic” humorous authorial persona. Finally, these positions are also distributed across personae via the situating system. The Vocative “you” in “laugh all you want” directs the tendered meanings to the audience. Then, the interpretation of the audience’s laughter as signaling their interpretation of the comedian’s verbiage as braggadocious is sourced to the comedian’s non-humorous persona, and the understanding that the audience’s laughter does not signal such critical evaluation is sourced to the comedian’s authorial, “humorous” persona and to the audience. Stepping through a fine-grained analysis of orienting features in the dataset is beyond the scope of this research, but the attribution of the text to humorous and non-humorous personae shown in Table 7 illustrates a first layer of analysis for sourcing features.

In the following turn (tone groups #15–17) the comedian states,

But, ah […] <smiles> I don’t know if that’s the best thing to say in a special, is <frowns> “Oh, yeah, laugh all you want.” <smiles>

<audience laughter>

This stretch of discourse contains an important feature of the humour in this segment as the comedian shifts to their authorial persona. This is initially signaled by the facial and voice affect resources realizing affect [spirit: up] features, which then converge with the shift in perspective implied by the negative evaluation of the preceding verbiage “Oh, yeah, laugh all you want”. The shift in persona is evident when the comedian quotes herself, as she re-embodies the negative facial and voice affect of the original utterance, thus creating a marked shift from the baseline facial affect at the beginning of the text (as per the dynamics of intermodal impersonation described in Logi forthcoming).

The shift from non-humorous to humorous authorial persona here is important to the ongoing affiliation between audience and comedian as it re-establishes the bond between interactants. By “stepping out” of the non-humorous persona via realisation of [spirit: up] voice and facial affect features, the comedian interrupts that persona’s confrontational, hostile demeanour ([spirit: warn]) with the audience, and instead offers a momentary reminder of their desire to bond ([spirit: warm]). This ensures that the tension generated by the non-humorous persona’s deviation from expected and appropriate behaviour, especially with regard to paralinguistic realizations of [spirit: warn] does not exceed the acceptable threshold for the audience and graduate from humorous to uncomfortable – what in commonsense terms is considered “crossing the line”. This pause in the impersonation of the non-humorous persona also allows the comedian to more explicitly laugh with the audience at the non-humorous persona’s behaviour. By negatively evaluating the verbiage “Oh, yeah, laugh all you want”, specifically in the context of a “special” (a reference to full-length stand-up comedy performances recorded for distribution), the comedian not only bonds with the audience and their previous laughter at the utterance, but also clarifies that it is indeed the inappropriateness of this behaviour that the comedian is leveraging for comic effect. Thus, by realizing facial and voice affect features that signal the comedian is stepping in to their authorial persona, the comedian realizes what in other genres might be termed an authorial aside, departing from the diegetic reality of the preceding text and reminding the audience of their solidarity with them.

The dynamic of occasionally stepping out of the non-humorous persona to reinforce the bond with the audience plays out a number of times in this excerpt. In terms of features from the new Tenor model, this parallels stretches of [spirit: warn], [\source: non-humorous persona] and a network of meanings related to hostility, confrontation and criticism for the audience, interspersed with stretches of [spirit: warm], [\source: authorial persona] and a network of meanings related to alignment and solidarity with the audience. This dynamic is clearly visible in the second half of the dataset, where the comedian continues recounting the anecdote of her temporary employment. The comedian begins this excerpt (tone group #33) impersonating their non-humorous persona, embodying serious, [spirit: down] paralinguistic affect:

<serious> And that entire week that I worked there […]

<audience laughter>

The audience laughter after the comedian’s verbiage is most plausibly interpreted as an ongoing deferral of the comedian’s inappropriately stern demeanour, however again the comedian deploys the trope of spuriously misinterpreting this laughter as a criticism. In the following segment (tone groups #34–37), they protest:

It was a temp job! <smiles>

<audience laughter>

<laughing> “Temp” is short for temporary! They asked five days of me, and I delivered.

<frowns>

<audience laughter>

The comedian’s verbiage, “It was a temp job!” serves to tender the meaning “audience laughing at comedian’s complaints for brief work experience”, implying that the audience is deriding the comedian for exaggerating the duress of the temporary employment. Further to maintaining the faux animosity between the non-humorous persona and the audience, this exchange illustrates how conventions surrounding the genre are themselves leveraged to create humour. Here the comedian is manipulating two features of stand-up comedy: that there is only a slight difference between the laughter signaling [defer: support] and that signaling [defer: reject],[5] and that the audience is both physically and customarily precluded from debating the comedian. Thus, the comedian misinterprets the audience’s laughter as laughing at them, knowing they are unable to contest this interpretation, and makes faux defence to the implied criticism. Tellingly, however, the comedian follows their defence with a smile and [spirit: up: cheer] voice affect when they say, “Temp is short for temporary!”, thus defusing some of the tension accumulated over the course of their impersonation of the non-serious persona.

The stretch that follows (tone groups #38–56) is perhaps the most illustrative of how [spirit: warn] and [\source: non-humorous persona] are realised by voice and facial affect, and how these are recruited to create humour in this segment:

But that ent-

<audience laughter, applause>

<smiling> Thank you!

<audience laughter, applause, cheering>

<smiling, waves to audience > Thank you! Good night! <turns, walks to stage back>

<audience laughter>

<voice tense > You guys would have been fine with that, if I just left. <frown>

All that build-up and then I’m like “hey I was great at my temp-job, good night!” <frown>

<audience laughter>

<smile>, <frown><voice exasperated > Now you’ve lost your sense of humour and you’re sitting there going “Nooo we wouldn’t! Don’t leave the [comedian laughs] stage, Tig!” [exhales]

<serious> Ok.

<audience laughter>

You’ve convinced me to stick around

<audience laughter>

I’ll go ahead […] and finish my story.

This stretch begins with the comedian responding to the audience’s applause by jokingly misinterpreting it as signaling the end of the performance (a reference to applause typically occurring at the beginning and end of stand-up comedy texts). At first the comedian, in their authorial persona, signals via their positive paralanguage (voice affect [spirit: up: cheer]; facial affect [spirit: up]) that they are sharing the audience’s deferral response, thus comedian and audience bond around the inappropriateness of the interpretation. We can code this as [spirit: warm], [\source: authorial persona], [tendered meaning: “audience applause signals end of performance”].

However, with “You guys would have been fine with that, if I just left” the comedian suddenly switches to their non-humorous persona and impersonates offence at the audience’s applause, thereby tendering the same meaning, but with [spirit: warn] and [\source: non-humorous persona]. This shift provides perhaps the clearest illustration of the productivity of voice affect and to a lesser extent facial affect in nuancing meanings so as to create humour in this dataset. We can see how the same tendered meaning “audience applause signals end of performance”, accompanied by paralinguistic resources realizing [spirit: warn], inverts the negotiation of meanings between comedian and audience from one of bonding affiliation to one of disaffiliation. The linguistic meaning of the verbiage “you guys would have been fine with that, if I had just left” converges with [spirit: warn], but it is the shift in voice affect from [spirit: up: cheer] to [spirit: down: misery] (realized by louder and higher pitch voice quality) that most clearly marks the change in spirit feature and thus infuses the meaning with tension that must be laughed off.

This mock-offence is sustained across the following turns, although the comedian’s smile before “Now you’ve lost your sense of humour” functions to release some tension and sustain the meaning implicitly shared with the audience: that the comedian’s offence is not serious. The comedian then proceeds to once again fabricate an interaction with the audience, stating that they’ve lost their sense of humour (absurd, as they are continuing to laugh), and that they are protesting the comedian’s accusations and imploring them not to leave. The comedian responds to this fictional attributed dialogue by relenting and agreeing to remain and finish her story. Across this stretch, audience laughter defers the comedian’s defensiveness and confrontationality and the absurdity of the comedian’s characterization of the audience. Positive voice and facial affect realize [spirit: warm] and [\source: authorial persona] features which prosodically temper the tension of the surrounding co-text so as to sustain bonding between audience and comedian. Essentially, whenever the comedian smiles, softens their voice quality or laughs with the audience, they are colouring the surrounding verbiage with the implication that they do not expect the audience to take it seriously, but rather expect the audience to agree with them that it is in some manner unexpected or inappropriate.

A final instance offering a clear illustration of the function of vocal sound semiotics in realizing intermodal impersonation and supporting humorous bonding in this stretch of the dataset occurs in tone groups #48–51, where the comedian impersonates the audience:

you’re sitting there going

“No we wouldn’t! Don’t leave the [comedian laughs] stage, Tig!”

[exhales] <serious> Ok.

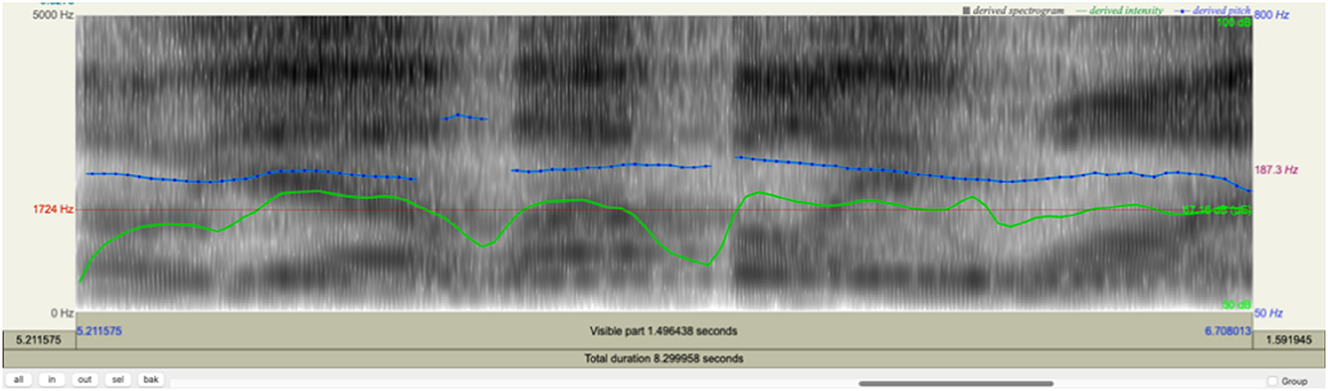

Here we can see specifically how the comedian shifts from the voice quality/affect of their non-humorous persona to that attributed to the audience. This instance of impersonation converges with a linguistic realization of extra-vocalization, “you’re sitting there going”[6] which synchronizes with marked shifts in voice quality/affect. As Figure 5 shows, the pitch and tension for the projected speech “No we wouldn’t! Don’t leave the stage, Tig!” Are higher and tenser than for the verbiage in the comedian’s non-serious persona’s voice, thereby attributing the voice affect feature of [threat: fear] to the audience. This allows the comedian to absurdly characterize the audience as distressed by the prospect of her departure, sustaining the absurdity of her impersonated exchange and generating tension that is collectively laughed off. A summary of the analysis of this final stretch of the text is presented in Table 11.

Spectrographic analysis of tone groups #48–49. Note: top blue line = pitch; bottom green line = volume. The lexical item “no” has been extended here to “Noooooooooooooooooo” to illustrate its extended duration.

Summary of analysis of tone groups #38–53.

| Tone group | Paralanguage | positioning | orienting | tuning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Verbiage | Tender | Render | |||

| 38 | But that ent- |

voice affect: [spirit: down: ennui] facial affect: [serious] |

comedian satisfied duties of employment | \non-humorous persona | spirit: warn | |

| <audience laughter, applause> | Comedian’s solemnity unserious | laugh with x solemnity of comedian’s statement incommensurate with triviality of temp work | ||||

| 39 | <smiling> Thank you! |

voice affect: [spirit: up: cheer] facial affect: [spirit: up] |

appreciation for audience applause | \humorous authorial persona | spirit: warm | |

| <audience laughter, applause, cheering> | appreciation for comedian’s performance | |||||

| 40 | <smiling, waves to audience> |

voice affect: [spirit: up: cheer] facial affect: [spirit: up] |

performance has ended | \humorous authorial persona | spirit: warm | |

| 41 | Thank you! Good night! <turns, walks to stage back> | |||||

| <audience laughter> | performance hasn’t ended | laugh with x performance has ended | ||||

| 42 | <voice tense > You guys would have been fine with that, if I just left. <frown> |

voice affect: [spirit: down: misery] facial affect: [threat: anger] |

comedian upset that audience happy for comedian to leave | \non-humorous persona | spirit: warn | |

| 43 | All that build-up | |||||

| 44 | and then I’m like | |||||

| 45 | “hey I was great at my temp-job, | |||||

| 46 | good night!” <frown> | |||||

| <audience laughter> | audience want comedian to stay | laugh with x comedian upset that audience happy for comedian to leave | ||||

| 47 | <smile> | facial affect: [spirit: up] | comedian’s offence not serious | \humorous authorial persona | spirit: warm | |

| <frown> <voice exasperated > Now you’ve lost your sense of humour |

voice affect: [spirit: down: misery] facial affect: [threat: anger] |

audience protesting comedian departure | \non-humorous persona | spirit: warn | ||

| 48 | and you’re sitting there going | |||||

| 49 | “No, we wouldn’t! |

facial affect: [threat: fear] voice affect: [threat: fear] |

||||

| 50 | Don’t leave the |

facial affect: [threat: fear] voice affect: [threat: fear] |

\humorous authorial persona | |||

| [comedian laughs] |

voice affect: [spirit: up: cheer] facial affect: [spirit: up] |

spirit: warm | ||||

| stage, Tig!” |

facial affect: [threat: fear] voice affect: [threat: fear] |

|||||

| 51 | [exhales] <serious> Ok. |

voice affect: [spirit: down: ennui] facial affect: [serious] |

agreeing not to leave | \non-humorous persona | spirit: warn | |

| <audience laughter> | audience want comedian to stay | laugh with x comedian upset that audience happy for comedian to leave; comedian’s fabrication of audience behaviour | ||||

| 52 | You’ve convinced me |

voice affect: [spirit: down: ennui] facial affect: [serious] |

agreeing not to leave | \non-humorous persona | spirit: warn | |

| 53 | to stick around | |||||

| <audience laughter> | audience want comedian to stay | laugh with x comedian upset that audience happy for comedian to leave; comedian’s fabrication of audience behaviour | ||||

| 54 | I’ll go ahead […] |

voice affect: [spirit: down: ennui] facial affect: [serious] |

agreeing not to leave | \non-humorous persona | spirit: warn | |

| 55 | and finish my story. | |||||

6 Conclusions

This article has presented an analysis of a segment of a stand-up comedy text employing the SFL phonology an voice quality/affect systems, the recently renovated model for Tenor (Doran et al. 2025) and the framework for analyzing intermodal impersonation (Logi forthcoming). The most noteworthy observations emerging from this analysis concern the role of voice and facial affect resources to realize features of the spirit and situating systems, which coordinate to mark shifts in impersonated personae and characterize the tone of their negotiations of meaning with the audience. In turn, shifts in impersonated persona and tone of tendered meanings create tension between the comedian and audience that is laughed off.

In terms of what meanings are tendered in this text and how these are rendered, the analysis suggests the primary networks of meaning in tension have to do with expected and appropriate behaviors for interactants in stand-up comedy performances, which might justify classifying the humour arising from the negotiation of these as “meta”, insofar as it is humour about humour. Similarly, the comedian’s sustained impersonation of a persona that is defensive and confrontational, and the consequent tendering of meanings in coordination with serious or even aggressive paralanguage, reflects the definition of the comedian’s style as “deadpan”. This text thus illustrates how impersonation and expectation interact in stand-up comedy performances, as the comedian associates a “non-humorous” persona with unexpected, inappropriate behaviour, thus simultaneously tendering transgressive meanings and maintaining distance between these and their more authentic “humorous” persona. Presented with this impersonation, the audience is able to laugh with the humorous persona at these transgressive meanings, confident that they do in fact share implicit meanings with the comedian.

While this article presents a principled analysis of vocal sound semiotic resources employed by comedians to create humour in their performances, its limited dataset does circumscribe the representativeness of its conclusions. As much as the alternation between authorial and impersonated personae will seem a common motif to anyone familiar with the genre of stand-up comedy, it is entirely possible that the role of these personae in other texts differs from that found in the text analyzed here in terms of their tenor relations with the audience. As always, more work is needed to both substantiate and elaborate upon the findings of this research. In this vein, a primary obstacle in the application of the methodology proposed here to larger datasets is the time intensive manual coding required as part of the analysis. The prospect of even partial automation of this process via artificial intelligence tools offers some potential to resolve this, however it may well prove more mirage than reality.

In addition to extending a similar approach to other datasets, there are a number of further regions in this area that remain to be explored. Principally, the role of specific voice quality features in eliciting particular associations invites exploration, as the anecdotal fecundity of vocal humorous resources such as parodied accents or impersonated stereotypes (such as particular genders, sexual orientations or ages) – and their often-problematic cultural associations – has been leveraged by comedians since the birth of the stand-up comedy genre. In these instances, impersonation can act as a fig leaf for discourse that sustains and even normalizes ethically turbid values, allowing comedians to hide behind the defence of humorous satire while still trading in the currency of oppression. Moreover, with the rise of populism and demagoguery around the world, humorous (and problematic) impersonation are increasingly found in political discourse (such as Donald Trump’s impersonation of a reporter with disability on November 26, 2015) where their cultural impact is exponentially amplified. In this context, a fuller cartography of which bundles of voice quality features correspond to which cultural meanings would provide a valuable insight into the productivity of vocal sound semiotic resources in humorous discourse, as well as advancing our understanding of how implicit meanings contribute to making humour and linking specific vocal sound semiotic features to current and concerning cultural phenomena.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available from: https://www.netflix.com/jp-en/title/80151384.

References

Abercrombie, David. 1965. Studies in phonetics and linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ariztimuño, Lilián I., Shoshana Dreyfus & Alison R. Moore. 2022. Emotion in speech: A systemic functional semiotic approach to the vocalisation of affect. Language, Context and Text: The Social Semiotics Forum 4(2). 335–374.10.1075/langct.21012.ariSuche in Google Scholar

Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth. 1993. English speech rhythm: Form and function in everyday verbal interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/pbns.25Suche in Google Scholar

Doran, Yaegan J., James R. Martin & Michele Zappavigna. 2025. Negotiating social relations: Tenor resources in English. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Eggins, Suzanne & Diana Slade. 2006. Analysing casual conversation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1967. Intonation and grammar in British English. The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783111357447Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1970. A course in spoken English: Intonation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1978. Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & William S. Greaves. 2008. Intonation in the grammar of English. London: Equinox.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. & Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar, 4th edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203783771Suche in Google Scholar

Jewitt, Carey, Jeff Bezemer & Kay O’Halloran. 2016. Introducing multimodality. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315638027Suche in Google Scholar

Kendon, Adam. 1997. Gesture. Annual review of anthropology 26(1). 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.109.Suche in Google Scholar

Knight, Naomi K. 2010. Laughing our bonds off: Conversational humour in relation to affiliation. Sydney: University of Sydney PhD thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Knight, Naomi K. 2011. The interpersonal semiotics of having a laugh. In Shoshana Dreyfus, Susan Hood & Maree Stenglin (eds.), Semiotic margins: Meaning in multimodalities, 7–30. London: Continuum.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunthe R. 2010. Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunthe R. 2012. Multimodal discourse analysis. In James P. Gee & Michael Handford (eds.), The Routledge handbook of discourse analysis, 25–50. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunthe R. & Theo van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading images: The grammar of visual design, 2nd edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203619728Suche in Google Scholar

Logi, Lorenzo. 2021. Impersonation, expectation and humorous affiliation: How intermodal impersonation and linguistic expectation are employed by stand-up comedians to create humour. Sydney: University of New South Wales PhD thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Logi, Lorenzo. forthcoming. Characters and surprises in stand-up comedy: A linguistic exploration of how comedians use impersonation and expectation to create humour. London: Bloomsbury.Suche in Google Scholar

Logi, Lorenzo & Michele Zappavigna. 2021. Impersonated personae – paralanguage, dialogism and affiliation in stand-up comedy. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research 34(3). 339–373. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2020-0023.Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. 1992. English text: System and structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.59Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. & Peter R. R. White. 2005. The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English. London: Palgrave Macmillan.Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, James R. & Michele Zappavigna. 2019. Embodied meaning: A systemic functional perspective on paralanguage. Functional Linguistics 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40554-018-0065-9.Suche in Google Scholar

McNeill, David. 1992. Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Mintz, Lawrence E. 1985. Standup comedy as social and cultural mediation. American Quarterly 37(1). 71–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/2712763.Suche in Google Scholar

Ngo, Thu, James R. Martin, Susan Hood, Clare Painter, Bradley A. Smith & Michele Zappavigna. 2021. Modelling paralanguage using systemic functional semiotics: Theory and application. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781350074934Suche in Google Scholar

O’Halloran, Kay L. & Victor Lim Fei. 2014. Systemic functional multimodal discourse analysis. In Sigrid Norris & Carmen D. Maier (eds.), Interactions, images and texts: A reader in multimodality, 137–154. Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781614511175.137Suche in Google Scholar

Painter, Clare, James R. Martin & Len Unsworth. 2013. Reading visual narratives: Image analysis of children’s picture books. London: Equinox.Suche in Google Scholar

Pike, Kenneth L. 1945. The intonation of American English. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Poynton, Cate. 1990. Address and the semiotics of social relations: A systemic-functional account of address forms and practices in Australian English. Sydney: University of Sydney PhD thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, Bradley A. & Walter S. Greaves. 2015. Intonation. In Jonathan J. Webster (ed.), The Bloomsbury companion to M. A. K. Halliday, 291–313. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781472541888.ch-011Suche in Google Scholar

Spreadborough, Kristal. 2022. Emotional tones and emotional texts: A new approach to analyzing the voice in popular vocal song. Music Theory Online 28(2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.28.2.7.Suche in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 1999. Speech, music, sound. London: Palgrave MacMillan.10.1007/978-1-349-27700-1Suche in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 2015. Rhythm and social context: Accent and juncture in the speech of professional radio announcers. In Paul Tench (ed.), Studies in systemic phonology, 231–262. London: Bloomsbury.Suche in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 2025. Three sound bites: Avenues for research in the study of speech, music, and other sounds. Journal of World Languages. https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2025-0037.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.