Abstract

This article presents a comprehensive and detailed survey of ecolinguistics, defined as an enterprise oriented to how language plays a role in the interactions between human beings, other species, and the natural environment. Since the early 1990s, ecolinguistics has been driven by a concern for life on Earth and as such it comprises the linguistic study of the current ecological crisis. Through a detailed close reading of the literature, in combination with the bibliometric tool of VOSviewer, it surveys eleven subfields of contemporary ecolinguistics. The eleven surveyed subfields of ecolinguistics are: discourse-oriented ecolinguistics, corpus-assisted ecolinguistics, ecostylistics, narratological ecolinguistics, identity-oriented ecolinguistics, ethno-lexical ecolinguistics, ecological discourse analysis, harmonious discourse analysis, cognitive ecolinguistics, educational ecolinguistics, and decolonial/transdisciplinary ecolinguistics. In the conclusion, the article discusses two challenges that face contemporary ecolinguistics: the repetition of certain tropes and narratives about the field, even in the absence of empirical evidence, and the lack of internal debate and critique.

1 Introduction

In 1990, Michael A. K. Halliday gave one of keynote lectures at the ninth international conference on applied linguistics in Thessaloniki in Greece. Under the title “New ways of meaning: the challenge to applied linguistics” he brought attention to a theme that was rarely touched upon in a linguistic context:

But there has been another, rather less publicized, change in the human condition: that our demands have now exceeded the total resources of the planet we live on. Within a microsecond of historical time the human race has turned from net creditor to net debtor, taking out of the earth more than we put in; and we are using up these resources very fast. (Halliday 2001: 191)

Ecological themes were already in circulation in applied linguistics in 1990. Frans Verhagen (2000: 35) mentions how he had organised two meetings for applied linguists who shared his concerns for the environment, and three years before the 1990 conference, Jørgen Bang and Alwin Fill each published their first attempts at formulating an ecological position in linguistics: Antydninger af en økologisk sprogteori [Hints of an Ecological Theory of Language] (Bang 1987) and Wörter zu Pflugscharen: Versuch einer Ökologie der Sprache [Words to Plowshares: Attempt of an Ecology of Language] (Fill 1987). Accordingly, Halliday articulated ideas that resonated with themes already in circulation but being a towering figure in linguistics in the 1990s, his lecture functioned as a catalyst of the field that became known as ecolinguistics. An oft-cited passage from his lecture encapsulates the ecolinguistic concern: “classism, growthism, destruction of species, pollution and the like […] are not just problems for the biologists and physicists. They are problems for the applied linguistic community as well” (Halliday 2001: 199).

As discussed in Steffensen (2024), this theme was soon brought together with another ecological perspective in linguistics, namely the one presented by Einar Haugen in his Ecology of Language (Haugen 1972). The connection was first established by Alwin Fill (1996), but as demonstrated in Steffensen (2024), the bibliometric evidence indicates that the oft-seen juxtaposition of two traditions in ecolinguistics (a Haugenian and a Hallidayan tradition) is no longer warranted. Based on bibliometric criteria, ecolinguistics anno 2024 does not cover the Haugenian tradition. Steffensen (2024) also discusses a model of ecolinguistics that was first presented in Steffensen and Fill (2014), according to which there exist four different ecological approaches in linguistics, defined by how they define the environment of language:

Some attend to the symbolic ecology of language and study how speakers in multilingual settings integrate two or more languages

Others study the sociocultural ecology of language and attend to educational and societal processes, including questions about language planning and learning

The natural ecology of language is studied by those who share Halliday’s concern for the negative effects of the entanglement of language and the ecosystemic surroundings of speakers

Finally, some pursue the study of the cognitive ecology of language by asking how language affects human agents in ways that have environmental implications

In 2014, all four could reasonably be seen as contributions to ecolinguistics as it was then understood. However, as demonstrated in Steffensen (2024), this broad definition of ecolinguistics is no longer sustainable. The bibliometric evidence suggests that only the third and fourth approach align with what the literature today perceives as ecolinguistics. On this view, ecolinguistics is preoccupied with “the impact of language on the life-sustaining relationships among humans, other organisms and the physical environment” (Alexander and Stibbe 2014: 105), or in a more recent formulation, with “languaging and bioecologies in human-environment relationships” (Steffensen et al. 2024b).

The alignment between Steffensen’s (2024) demarcation of ecolinguistics and the two definitions of ecolinguistics raises an important question: What kind of work is pursued within this definition? This article aspires to provide a detailed answer to this question. After this introduction, Section 2 provides an overview of the chapter, partly through a short methodological note, and partly through an overview of the subfields of ecolinguistics surveyed here. Sections 3 to 11 attends to eleven subfields, and Section 12 is a short conclusion that includes a discussion of two challenges that face contemporary ecolinguistics.

2 Overview

The methods applied in this article are basically the same as in Steffensen (2024), for which reason the reader is referred to this article for a full overview. The article uses a combination of bibliometric methods and close readings of the literature. The bibliometric method is based on VOSviewer, developed by Nees Jan van Eck and Ludo Waltman (cf. Lamers et al. 2021; van Eck and Waltman 2009; van Eck and Waltman 2010; van Eck and Waltman 2023; van Eck et al. 2010; Waltman and van Eck 2012; Waltman et al. 2010).

Data for the visualisations are taken from Scopus and extracted on 9 April 2024. The search string used in Scopus is: “Title/abstract/keywords = ecolinguist* AND Language = English” (where the asterisk denotes zero or more characters). Altogether, this search produced 292 items. Scopus was used because it provides a cleaner set of author keywords, in contrast to the more extensive open access databases, Dimensions and Lens. However, since Scopus is arguably too restricted, select publications that are not covered by Scopus (in particular monographs) were manually added to the survey data. For details, see the methodological considerations in Steffensen (2024).

The bibliometric process relied on author keywords only, that is, keywords provided by the author, in contrast to indexed keywords based on such subject indexes as GEOBASE. Only author keywords with two or more occurrences were included. Altogether, 130 author keywords had two or more occurrences. Out of these, eighteen were manually removed because they referred to generic scientific terms (‘context’, ‘methodology’, etc.) or because they referred to studies in linguistic ecology (e.g. ‘language planning’, ‘teacher education’, and ‘multilingualism’), which falls outside of the definitions provided by Alexander and Stibbe (2014), and by Steffensen et al. (2024b).

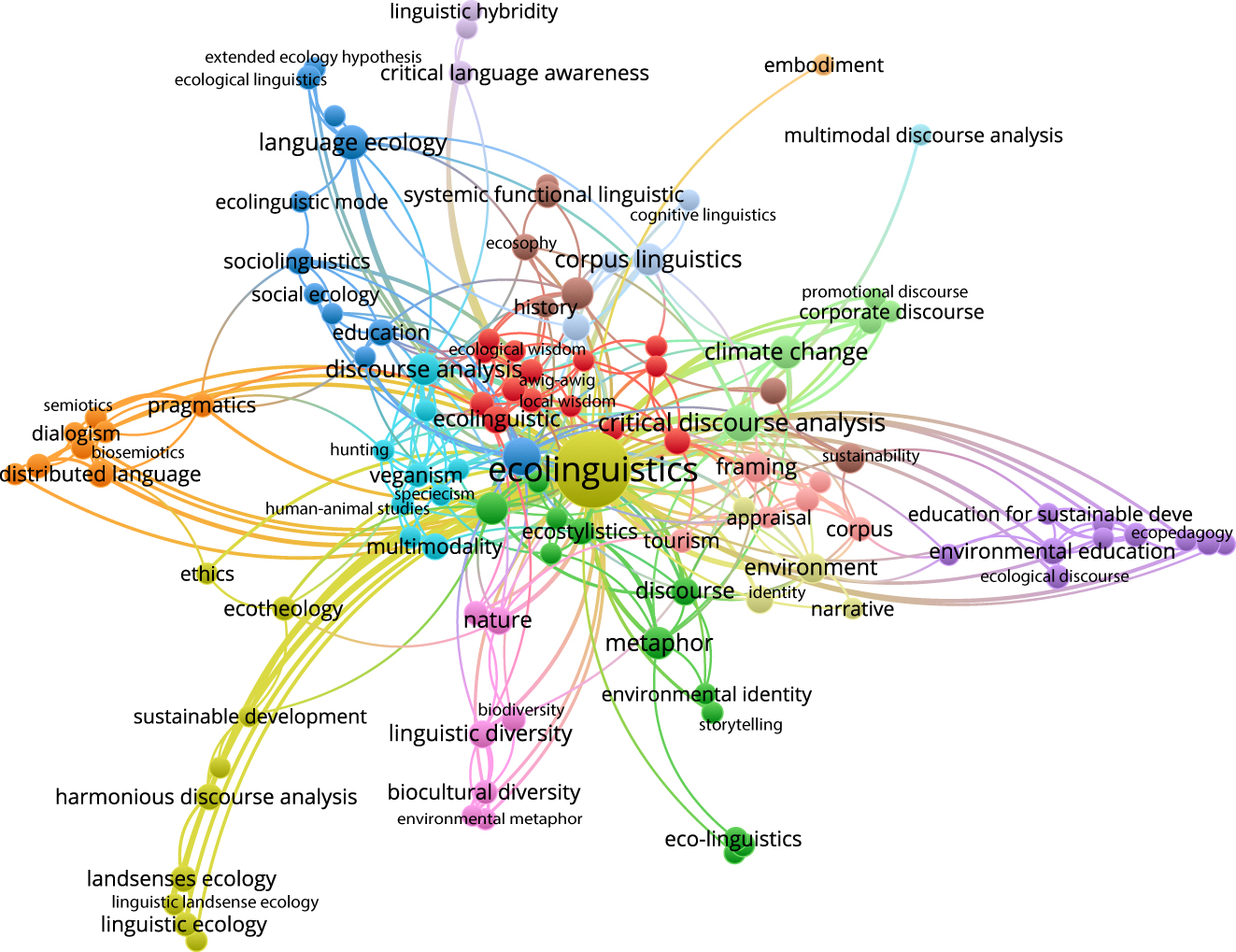

All remaining author keywords were included in VOSviewer, which produced the map in Figure 1.

Co-occurrence of author keywords. Note: Labels indicate keywords; size of nodes indicates number of occurrences. Node colours indicate the clustering of keywords. Coloured lines indicate links in VOSviewer. Files that allow for a zoomable map in VOSviewer are provided as Supplementary Material.

Figure 1 is organised around ‘ecolinguistics’ as the main author keyword, which appears 146 times in the dataset. Like petals on a flower, clusters in different colours stretch in different directions. Some petals remain close to the centre of the map, while others are more peripheral. As we shall see in Sections 8 and 9, a peripheral placement on the map can mean two different things: It can be due to a given cluster being inherently less preoccupied with the themes that unite the other clusters, or it can be due to the fact that a given cluster is a recent development and thus less integrated with the more mainstream positions closer to the centre of the map. Altogether, VOSviewer identifies sixteen clusters, where the smallest consist of only one item.

In what follows, all clusters will be discussed, though they will be bundled in larger sections, which each attends to a specific subfield in ecolinguistics. These subfields are not coextensive with the sections that follow this overview, as large subfields are divided into more sections, and small subfields are grouped into single sections. All in all, the survey demonstrates that contemporary ecolinguistics is composed of the following eleven subfields:

Corpus-assisted ecolinguistics (Section 6)

Ecostylistics (Section 6)

Narratological ecolinguistics (Section 6)

Identity-oriented ecolinguistics (Section 6)

Ethno-lexical ecolinguistics (Section 7)

Ecological discourse analysis (Section 8)

Harmonious discourse analysis (Section 8)

Cognitive ecolinguistics (Section 9)

Educational ecolinguistics (Section 10)

Decolonial and transdisciplinary ecolinguistics (Section 11)

3 Discourse-oriented ecolinguistics

Historically, ecolinguistics has been strongly associated with discourse analysis. Early on, emphasis fell on critical discourse analysis, but in recent years, ecolinguists have also adopted positive discourse analysis (Martin 2004). The strongest link in the map in Figure 1 is indeed between ‘ecolinguistics’ and ‘critical discourse analysis’. The latter is placed in the mint green cluster to the northeast of ‘ecolinguistics’ and above the light red cluster that contains ‘positive discourse analysis’. In addition to these two keywords, these two clusters also contain specific discourses – ‘corporate discourse’, ‘promotional discourse’, and ‘political discourse’ – and specific theoretical orientations within discourse analysis – ‘framing’, ‘corpus’, ‘appraisal’, and ‘multimodal analysis’. Finally, two key concerns are highlighted with each their keyword in these two clusters: ‘tourism’ and ‘climate change’. Thus, the link between ‘ecolinguistics’ and ‘climate change’ is the second strongest in the entire map, making the triangle of ecolinguistics, critical discourse analysis, and climate change a centre of gravity in the field.

Critical discourse analysis is a descendant of the 1970s tradition of critical linguistics (Halliday 1978; Kress and Hodge 1979), but whereas the critical linguistic tradition included studies of imperialistic linguistic practices (cf. Mühlhäusler 2003: 32), critical discourse analysis focuses on discursive and textual patterns, and this tendency has been adopted in wide parts of ecolinguistics. Indeed, ecolinguistics is predominantly a discourse-based discipline, for better and for worse.

An early key publication in critical discourse analytical ecolinguistics is Richard Alexanders 2009 monograph, Framing Discourse on the Environment: A Critical Discourse Approach (Alexander 2009). While Alexander approaches environmental discourses from a broadly Hallidayan vantage point, combined with critical tenets from ecolinguistics and political theory and activism, his theoretical stance is explicitly toned down: “my contribution does not claim to be within a specific analytical framework” (Alexander 2009: 14), and “the ontological and epistemological relation between reality (the ‘world’) and language (‘wording’) need not delay us here” (Alexander 2009: 21). However, Alexander demonstrates how corpus-based methods in a dialectical interplay with qualitative analyses can be used in a critical discussion of ecological discourse, especially in the context of economic dimensions of capitalist production. Going over Alexander’s monograph is highly instructive because the choice of texts and genres analysed has been very influential in discourse-oriented ecolinguistics. The book thus scrutinises articles from mainstream media outlets (e.g. The Economist), vision/mission statements and other strategic texts from capitalist corporations (e.g. The Body Shop), advertisements (e.g. from NIREX), corporate websites (e.g. from Shell and Monsanto), speeches from corporate executives (e.g. John Browne from BP), and public discourse genres (e.g. BBC radio broadcasted lectures). These genres have all been widely investigated in ecolinguistics, as exemplified by Zhang and Li’s (2013) critical study of commercials for cosmetic products, or Danni Yu’s (2020) analysis of metaphors in corporate environmental reports. Few, however, have incorporated Alexander’s explicitly political dissections, focusing on the unholy matrimony between capitalists from the fossil fuel and agrochemical industries and political stakeholders in liberal democracies.

Arguably, the most impactful publication in the tradition of discourse-oriented ecolinguistics is Arran Stibbe’s monograph Ecolinguistics: Language, Ecology and the Stories We Live By (Stibbe 2015, 2021). Methodologically, Stibbe is also committed to the critical analysis of ecological discourses, but as compared to Alexander he makes three innovations (see also Alexander and Stibbe 2014).

First, he replaces Alexander’s reliance on corpus linguistic approaches with a more varied ‘toolbox’ compiled from frame theory and metaphor theory (derived from cognitive linguistics), discourse psychology, and theories about appraisal, erasure, salience, and linguistic narratology. Accordingly, throughout nine chapters of the book, Stibbe uses such heuristics as ideology, framing, metaphor, and evaluation in order to analyse numerous texts. Some of these are in the same genres as the texts analysed by Alexander’s, while other texts are taken from political parties as well as textbooks on microeconomics and new economics; environmental and ecosystem pamphlets, films, reports, and websites; Haiku poetry and narrative/fictional texts on nature; men’s health magazines; and various documents from governmental agencies, political parties, and other political stakeholders.

Second, he devises an analytical strategy consisting of two steps: (1) The linguistic methods are used to extract a story, that is, “a mental model within the mind of an individual person which influences how they think, talk and act. […] They do not just exist in individual people’s minds, but across the larger culture in what van Dijk [....] refers to as social cognition” (Stibbe 2021: 10). (2) In turn, these stories are juxtaposed to the analyst’s ethical framework, which Stibbe – following Næss – terms an ecosophy (Stibbe 2021: 11–12), in order to explicate an ethical, value-based evaluation – vis-à-vis the ecosophy – of the texts and the underlying stories which are “revealed” in the analysis.

Third, Stibbe picks up a theme from Goatly (2000) and Martin (2004) by including both texts that are deemed negative or destructive and texts that are seen as more positive or beneficial; this contrasts with Alexander’s critical focus on texts affiliated with environmental degradation and greenwashing. To denote this contrast, it has become widespread to assert that while the latter is indeed critical in its outlook, the former pursues a positive discourse analysis. This step has left a considerable footstep on ecolinguistics, as exemplified by Ponton and Raimo’s (2024) recent study on Greta Thunberg’s speeches and Sokół’s (2022) study of “interdiscursive practices […] as a ‘positive’ linguistic resource that can encourage people to protect our ecosystems”. The co-existence of the two is a remarkable feature in discourse-oriented ecolinguistics, even to the degree where Bednarek and Caple (2010: 9) suggest that “ecolinguistic discourse analysis” is exactly one that features both the critical and the positive strand. This complementarity of critical and positive has prompted authors to suggest that negative stories can be turned into subversive eco-positive narratives. For instance, Augustyn (2023) explores how the “master narrative” of economic growth can be challenged by stories of sharing and thriving.

With these overall remarks on the development of discourse-oriented ecolinguistics, let us now turn to the major concerns in this tradition, namely climate change and tourism (in the next section), and sustainability, animal welfare, and diversity (in Section 5).

4 Discourses of climate change and tourism

As mentioned in the previous section, the mint green area of the map in Figure 1 indexes two concerns for discourse-oriented ecolinguistics: climate change and tourism. As for the former of these, I disagree with Penz and Fill (2022) who argue that “among ecolinguists, only a few researchers so far have dealt with the issue” and that “this topic is as yet not at the center of ecolinguistics” (Penz and Fill 2022: 11 and 12). The bibliometric data suggest otherwise, even if one ignores the many studies published after Penz and Fill’s article. As emphasised by Penz and Fill, the earliest ecolinguistic studies on climate change were by Brigitte Nerlich and colleagues (Collins and Nerlich 2014; Döring and Nerlich 2005; Nerlich 2012; Nerlich and Koteyko 2009a, 2009b).[1]

Within the tradition that deals with climate change discourse from an explicitly critical discourse analysis approach, the most thorough discussion of climate change is Al-Shboul’s monograph on The Politics of Climate Change Metaphors in the U.S. Discourse (Al-Shboul 2023). Al-Shboul adopts the view that “Ecolinguistics as an approach heavily relies on CDA [critical discourse analysis] to uncover the constructed meanings and messages signaled by linguistic features (e.g. kinds of metaphors used) that are ideologically loaded about the environment” (Al-Shboul 2023: 42). Accordingly, in line with Stibbe (2021) he combines critical discourse analysis with conceptual metaphor theory. The analysis is framed within an explicit ecosophy used to classify and evaluate US politicians’ view on climate change (Al-Shboul 2023: 207–208). Somewhat simplistically, this analysis draws on both Stibbe’s (2021) and van Dijk’s (1997) classification of “ideologies as positive and negative” (Al-Shboul 2023: 208) and concludes with an either-or friend-or-foe picture of both speakers and discourses. Al-Shboul’s focus on political discourses is shared by a recent study by Buonvivere (2024). In an intriguing article, he shows how Māori culture shapes choices of metaphor and framing within the speeches given by Nanaia Mahuta, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs of New Zealand (Aotearoa). Related to political discourse, Niceforo (2024) discusses activist discourse by investigating how climate activists from Just Stop Oil are being discursively constructed and attacked, and Cheng and He (2021) present an ecological discourse analysis of British and Russian news reports on the “Sino-US trade war”.[2] I will return to Cheng and He’s (2021) contribution in the subsection on ecological and harmonious discourse analysis below.

Other ecolinguistic studies of climate change, in which critical discourse analysis is recruited as a method, include Wang and Liu’s recent study of visual narratives (hence the appearance of ‘multimodal analysis’ in the map above) in sustainability reports from a petroleum business (Wang and Liu 2024), Nuh and Prawira’s ecolinguistic analysis of climate change news in Indonesia (Nuh and Prawira 2023), and Kanerva and Krizsán’s “analysis of linguistic polyphony in the Summary for Policymakers by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change” (Kanerva and Krizsan 2021). The last two keywords in this part of the map in Figure 1 – promotional discourse and corporate discourse – both index work by the Spanish ecolinguist Fernández-Vázquez and colleagues (Fernández-Vázquez 2021a, 2021b; Fernández-Vázquez and Sancho-Rodriguez 2020). They too apply multimodal methods and a broadly systemic-functional outlook in their analyses of narratives and ideologies in corporate sustainability websites of so-called IBEX 35 companies in Spain and in the websites of twenty fossil fuel companies, all considered to be among the most polluting companies in terms of carbon emission.

Finally, the recent years have witnessed a surge in ecolinguistic publications on climate change from critical and multimodal perspectives. Most of these are solid but somewhat run-of-the-mill analyses of texts and speeches from political and media discourses (Abbamonte 2021; Kaushal et al. 2022; Norton and Hulme 2019; Osama Ghoraba 2023; Wang et al. 2019b; Xiong and Wang 2023; Xue and Xu 2021; Zollo 2024). There are, however, also other genres represented, for instance Zuo’s systemic-functional analysis of Emily Dickinson’s poem “The Grass” (Zuo 2019a), and Riaz, Mehmood, and Shah’s (2022) analysis of Taufiq Rafat’s poem “The Arrival of Monsoon”.

The second area of concern within critical discourse analytical ecolinguistics highlighted in the keywords in Figure 1 is tourism. This topic was included by Mühlhäusler in his recent Quo Vadis, Ecolinguistics? (Mühlhäusler 2020) where he listed topics ‘routinely excluded’ in ecolinguistics. Perhaps this desideratum has been heard in the field; at least a number of publications have attended to this topic, primarily within the very active group of Indonesian ecolinguists. For instance, Istianah and colleagues use a solid corpus-based methodology to investigate ideologies underlying appraisal patterns on websites for promoting tourism in different regions of Indonesia, including Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo (Istianah 2020; Istianah and Suhandano 2022). They demonstrate that tourism websites cast wildlife and nature, not inherently as parts of ecosystems, but rather as part of a tableau to be enjoyed by spectators. Kardana and colleagues (2022) discuss how Balinese local wisdom has been contaminated by the influence of information technology and tourism. In a European context, Ponton (2023) adopts the heuristic ‘imaginary’ from the social sciences and uses it for a study of pictures in ‘ocularcentrist’ websites for promoting tourism in Sicily, Italy. Like Istianah, Ponton uses Sicily as a case study to illustrate industry-wide semiotic operations, such as “propos-[ing] to immerse consumers in pristine natural environments, [which] reflects the shared mindsets of producers and consumers alike, and actually conflicts with ecological principles” (Ponton 2023: 20).

Finally, Trčková (2016) – in a study that actually predates Mühlhäusler’s desideratum – shows how ecotourism promotes a practice of “responsible travel” which, however, is not anchored in a new appreciation of nature. Thus, Trčková concludes that “the celebration and the empowerment of nature in the ecotourism advertisements tend to take place at the expense of the reproduction of the human-nature dichotomy, portraying nature as the Other” (Trčková 2016: 79).

5 Discourses of sustainability, animal welfare, biodiversity, and biocultural diversity

We will now move from the north-northeast in Figure 1 to the area west of ‘ecolinguistics’. Here we find a belt stretching from the brown cluster northwest of ‘ecolinguistics’ over the indigo area to the west of ‘ecolinguistics’ and further downwards to the southwest pink area. The brown cluster picks out ‘sustainability’ as an area of interest, in collocation with such theoretical terms as ‘ecological discourse analysis’ and ‘systemic functional linguistics’. The indigo includes a cluster of keywords on ‘human–animal studies’, ‘hunting’, ‘speciesism’, ‘veganism’ and ‘animal welfare’ – all in various combinations with ‘discourse analysis’ and ‘multimodality’ which are the two most frequent keywords in this cluster. Finally, the pink cluster includes ‘nature’ and ‘biodiversity’ – but also their counterparts within the human domain, namely ‘culture’ and ‘linguistic diversity’, as well as the bridge-building concept of ‘biocultural diversity’.

After climate change, the most recurring theme in discourse-oriented ecolinguistics relates to the discursive representation of animals. In their excellent overview in The Routledge Handbook of Ecolinguistics, Cook and Sealey (2018: 311) even argues that it “deserves to be a key area in ecolinguistics”. In an ecolinguistic context, Arran Stibbe’s work is a milestone. Thus, his first monograph, Animals Erased (Stibbe 2012a) was an extensive discussion of this topic, building on a series of previously published articles (Stibbe 2001, 2003, 2006, 2012b).

Along these lines, Guy Cook (2015) shows how the portrayal of animals is affected by the reduction of human-animal interaction due to urbanisation. In the urban context, animals are “encountered only as meat, pets, pests or vicariously in fiction and documentaries” (Cook 2015: 587). In the absence of real encounters with animals, the representations of animals tend to be heavily polarised into two camps: human exceptionalism versus animal rights. Interestingly, it is not discussed how the adoption of ‘rights’ discourses is an fact an anthropomorphic move, as a concept from the social domain – at least since the enlightenment – is transferred onto the relation between human and nonhuman animals, as discussed by Bang and Døør (2007) in their critique of “rights discourses”. Other discourse-oriented treatments of this topic are Tønnessen’s (2018) analysis of anthropocentrism in Norwegian political parties’ depiction of animals, Moser’s (2021) Derrida-inspired critique of the human-animal dichotomy, Zhdanava and colleagues’ study of the representation of nonhuman animals in British campaign posters for veganism (Zhdanava et al. 2021), and finally Augustyn’s (2022) discussion of habits and beliefs from a perspective of American pragmatism. Cook’s point about animals featuring in fiction is mirrored in Nurhayani’s (2024) study of how the mouse-deer is represented as a trickster in Indonesian and Malaysian folktales, and Bhattacherjee and Sinha’s (2023) analysis of speciesist metaphors in Bengali tweets.

However, when it comes to understanding the actual embodied interplay between human and nonhuman animals, the study of discursive representations of animals are of limited value. In contrast, ecolinguistic work by Gavin Lamb (2021, 2024) and Leonie Cornips (2024) innovates by indicating the huge potential for studying actual interspecies interactions between human and nonhuman animals with methods from various linguistic fields. In addition, the January 2024 issue of Journal of Pragmatics is a special issue on “interspecies pragmatics” edited by Peltola and Simonen (2024).

Sustainability is the most prominent keyword in the brown cluster. Since the Brundtland report (“Our common future”) was published in 1987, there has been a global focus on “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland and World Commission on Environmment and Development 1987: 43). This future-orientation comes to the fore with the concept of sustainability. Bibliometrically, it is a tricky concept, however, because it has been appropriated far beyond its use in the Brundtland report. In ecolinguistics, therefore, it is important to single out work that references sustainability pertaining to the use of the world’s resources. An excellent example of such work is Kosatica’s (2024) case-study of semiotic and material processes in the German city Essen (incidentally, the last city to host an AILA [International Association of Applied Linguistics] panel on ecolinguistics). Integrating multimodal social semiotics and ecolinguistics, her work is framed as a contribution to the field of linguistic landscapes. Thus, Kosatica’s data are public signs and other semiotic artefacts in the urban landscape of Essen, which pertain to the city’s ambitions of becoming a sustainable (i.e. low or zero carbon emission) urban ecosystem. Through a detailed analysis of the cityscape of Essen, she identifies the political economy underlying the sustainability ambitions, where semiotic artefacts cover up unsustainable practices and social inequalities. Similar themes appear in Li and Fontaine’s (2023) study of Chinese sustainability discourse.

Another important aspect of sustainability is how it is being taught and transmitted in educational contexts. Ainsworth (2021) discusses how business communication curricula can be informed by ecolinguistic concerns for sustainability. To illustrate, she analyses two annual report letters to shareholders in order to critically discuss the two letters’ diverting values and leadership discourses (pursuing ethical motives versus adhering to a neoclassical business model). She then demonstrates how Stibbe’s (2015) framework can be used for teaching critical language awareness in business communication contexts. I will return to educational issues in Section 10 on educational ecolinguistics.

Recently, sustainability, ecology, and pro-environmental behaviour from an (eco)linguistics perspective was the focus of an entire special issue of Frontiers in Psychology, edited by Jennifer Bruder, Hadeel Alkhateeb, and Salim Bouherar. Not all contributions are included in this survey of ecolinguistics, mainly because the editors’ focus is on how “environmental issues [can] be communicated through an effective use of language” (Bruder and Bouherar 2023: 1).

Moving southward in Figure 1, we enter the terrain of diversity. This theme is, unsurprisingly, also treated with the ‘standard’ set of methods from ecolinguistics, critical discourse analysis, and subsets of cognitive linguistics. An example is Drury, Fuller, and Keijzer’s (2022) study of speakers at the biodiversity communication at the UN Summit 2020 who blended frames from nature and business, arguably with effects detrimental to the preservation of biodiversity. Another case is Lieberman’s (2022) analysis of species protection in industrial farming contexts.

However, more interesting than discourses of biodiversity is the link established between biodiversity on the one hand, and linguistic and biocultural diversity on the other. This link features prominently in The Ecolinguistics Reader: Language, Ecology and Environment (Fill and Mühlhäusler 2001), particularly in the contributions by Mühlhäusler, Glausiusz, and Laycock, which are all placed in the edited volume’s section on “linguistic and biological diversity”. As Mühlhäusler observes in his contribution, “the 10,000 or so languages that exist today reflect necessary adaptations to different social and natural conditions. They are the result of increasing specialization and finely tuned adaptation to the changing world” (Mühlhäusler 2001: 160). Mühlhäusler has elaborated extensively on this theme which is at the core of human adaptation to the environment (Mühlhäusler 2003, 2006; Mühlhäusler and Peace 2006). It is also picked up by Catherine Grant (2012), who – like Mühlhäusler – transcends the metaphorical parallels between biodiversity and linguistic diversity, as she argues that “the very real interconnections between these two kinds of ‘diversities’ holds [sic] implications for cultural heritage management, since efforts to safeguard cultural diversity will be impacted by the successes and failures of efforts to protect biodiversity, and vice versa” (Grant 2012: 153). A main target of criticism from this tradition is how English imperialism (often referred to with the euphemism “globalisation”) has had dire linguistic effects, promoting monolingual practices by eradicating languages that are – as Mühlhäusler argued above – attuned to the social and natural conditions of a given environment. Bhushan (2021: 1) pursues this theme with the starting point that “the dwindling ecological diversity and declining linguistic diversity are the two greatest challenges before the world in modern times” and therefore one should turn to Bhasha (i.e. mother tongues and indigenous languages). This argument – as well as the example – resonates with Mühlhäusler’s (2010: 428) discussion of the difference between Javanese Basa and modern Indonesian Bahasa. The former includes “notions of civility, rationality, and truth” because the environmental attunement of a given language is interpreted as an isomorphism. In contrast, Bahasa “emerged as a translation of the Dutch taal [language] in the sense of modern nation-state defined by its grammar and lexicon.” Finally, Černý (2023) points to the value of linguistic diversity by an in-depth study of the poetry of Ofelia Zepeda whose poems are written in both English and the Indigenous North American (Uto-Aztecan) language Tohono O’odham. In her poetry, she unravels the negative consequences of human behaviour on the environment, in ways that are affected and informed by her bilingual background.

The theme of linguistic diversity may prompt some to interpret it as the recurrence of Haugenian ecolinguistics. That, however, would be a misunderstanding. In spite of the ecological vocabulary, Haugen’s ecology of language was predominantly an exercise in sociolinguistics and a response to Chomsky’s separation of psychological processes and processes of communication. Mühlhäusler’s term ‘biocultural diversity’ is key here, as it helps us emphasise that the starting point is exactly the natural environment in its entire variability, and linguistic diversity is only introduced as a way of accounting for human living in and with such environments.

6 New disciplinary voices in ecolinguistics

To the south of the central keyword ‘ecolinguistics’ one finds a network of terms that denote theoretical positions and approaches that have made it into ecolinguistics in recent years. These include the large green cluster in Figure 1, as well as a small light yellow cluster next to it. Together with the light purple cluster to the north of ‘ecolinguistics’, these clusters share the common theme that they extend discourse-oriented ecolinguistics by introducing new disciplinary voices and methods. In this subsection, I will survey four such theoretical developments in ecolinguistics.

The first, and also oldest, of these developments is the introduction of methods from corpus linguistics. As already shown, Alexander’s (2009) ground-breaking 2009 monograph made use of corpora that gave rise to analyses of concordances of specific wordings, but the use of corpus linguistic methods per se was limited in this work. The Scopus dataset includes sixteen studies where the keyword ‘corpus’ appears (and additional six if one adds ‘corpus-assisted’ and ‘corpus ecolinguistic’ as search terms), but Robert Poole, probably the leading ecolinguist within the corpus-based tradition, surveys many contributions to “Corpus-Assisted Ecolinguistics” in the second chapter of his monograph of the same name (Poole 2022). Neither Alexander’s nor Poole’s monographs feature in the Scopus dataset (that is one of Scopus’s obvious limitations), so the earliest Scopus-indexed publication to address ecolinguistic issues from a corpus linguistic approach is Potts, Bednarek, and Caple’s (2015) study of the news reporting on Hurricane Katrina in a 36-million-word corpus of news reporting. They place their work in the tradition of “Bednarek and Caple’s discursive approach” which focus on “how an event is constructed as newsworthy through semiotic resources such as language” (Potts et al. 2015: 149–150). A key insight in this article, which mirrors Alexander’s approach, is that corpus-based methods must be supplemented by qualitative analyses of textual sequences (concordances and collocations) in order to identify meanings in the texts analysed. To emphasise this point, Poole distinguishes between ‘corpus linguistics’ and ‘Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies’ (Poole 2022: 10–20). This distinction makes it clear that there is a way forward if one carefully balances the discursive analysis of single cases and the corpus-assisted focus on larger trends, and hence also balances quantitative and qualitative methods. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to survey the techniques and methods used in this line of work, so suffice to say that most work integrate quantitative methods (e.g. keyword analysis, frequency measures, and concordancing analysis) applied on large corpora and qualitative methods used to interpret overall trends identified with quantitative methods. Poole (2018, 2022) further innovates by integrating Geographical Information Systems and corpus-assisted methods. Finally, Sealey and Pak (2018) engages in an enlightening discussion of how to construct a corpus which allows for a corpus-assisted discourse analysis of representations of nonhuman animals.

When it comes to the themes and topics explored in this cluster of ecolinguistics, they fall very close to the topics discussed in the sections on discourse-oriented ecolinguistics, including news coverage of environmental events (Potts et al. 2015; Xiong and Wang 2023), extractive and exploitative mining practices (Poole 2018), the decline of references to animals with urbanisation (Frayne 2019), changes in the discursive representation of trees in a US context (Poole and Micalay-Hurtado 2022), diachronic changes in the representation of second-hand consumption (Gilquin 2022), differences in representations of recycling of plastic packaging across different corpora and genres (Franklin et al. 2022), contrasting views on the use of genetically modified seeds (Frayne 2022), communicative strategies for disseminating medical content in different epochs (Sousa and Nunes 2022), Chinese students’ perception of sustainability (Huang 2023), Spanish politicians’ tweets on climate change (Osama Ghoraba 2023), and large-scale contested political projects, such as the construction of a new capital city in Indonesia (Suhandano et al. 2023).

The second noteworthy disciplinary development in ecolinguistics is the emergence of methods from stylistics. According to Virdis, stylistics is “the study and analysis of texts founded on precise and exhaustive linguistic description” through close reading and with the aim of “explain[ing] the processes of meaning construction, to show how linguistic choices give rise to interpretations and to account for the effects such choices produce” (Virdis 2022a: 47–49). This theoretical development was first proposed by Andrew Goatly in 2010 (cf. Virdis 2022a: 63), in a conference presentation that was published seven years later (Goatly 2017), in a volume edited by Douthwaite et al. (2017). Virdis and Zurru later co-edited the volume Language in Place: Stylistic Perspectives on Landscape, Place and Environment (Virdis et al. 2021), and together with Goatly they are among the most prominent exponents of this development in ecolinguistics. In particular, Daniela Virdis has contributed with her 2022 monograph, Ecological Stylistics: Ecostylistic Approaches to Discourses of Nature, the Environment and Sustainability (Virdis 2022a). This book is still in the discourse-oriented tradition, albeit with the use of an analytical repertoire from stylistics. The book’s analyses pivot on five so-called “marker words” or “environment words” – namely nature, environment, ecosystem, ecology, and sustainability – all approached in five non-fiction websites written by environmentalist organisations. Virdis has also used this framework to study historical texts (Virdis 2022b), also here with an emphasis on what she terms “beneficial discursive strategies”. Along similar lines, Zurru (2021) performs an ecostylistic study of videos from an interactive exhibition on the planet’s future, as well as of a novel by Amitav Ghosh (Zurru 2017), and Fois (2020) demonstrates how translations of fiction texts impact on the readers’ sense of the landscape in which the narrative plays out.

The third development resonates with the ecostylistic focus on how stylistic and linguistic choices shape narratives. Thus, for the past five years narratological methods and approaches have entered ecolinguistics. In Figure 1, this theme is represented by the keywords ‘narrative’ (which appears in the small light yellow cluster together with ‘identity’ and ‘environment’) and ‘storytelling’ (which is a node in the large green network together with ‘ecostylistics’ and ‘discourse’).

While originating in the work of Erin James (2015), this econarratological turn can be interpreted as an extension of Stibbe’s focus on “stories we live by” (Stibbe 2015). The continuity between Stibbe’s foundational contribution to ecolinguistics and the narratological theme comes to the fore in Stibbe’s (2024) recent monograph, Econarrative: Ethics, Ecology, and the Search for New Narratives to Live By. Narrative is interpreted in the widest sense as “how we understand the world” (Stibbe 2024: 3). Stibbe (2024: 5) distinguishes between underlying narrative structures and manifest narrative texts, and he categorises at least the former as a cognitive devise, though he also acknowledges their cultural and social roots and functions. On this view, econarratives structure how we understand, not only a human world, but a world of human and nonhuman animals, as well as the physical environment. The monograph hence outlines how econarratives are analysed and in turn evaluated vis-à-vis the analyst’s ecosophy, similarly to the analytical strategy outlined in Stibbe’s previous monographs (Stibbe 2015, 2021).

The turn to narratives is still relatively recent, so apart from Stibbe’s monograph there are not much work along these lines. Abbamonte (2021) analysed two narratives juxtaposed in Greenpeace videos: nature as a resource versus nature as a condition for life. Similarly, in a recent ecolinguistic special issue of Text & Talk, edited by Douglas Ponton and Małgorzata Sokół (2022), Ponton (2022) intriguingly teases out two types of ecological narratives on a specific site, the Saline di Priolo reserve in Sicily: one that yearns for an idyllic semi-mythical past, and one that acknowledges the need for natural recovery after decades of human exploitation of nature. Stradling and Hobbs (2023) is the most directly narratological contribution in the Scopus dataset. Combining linguistic and discursive methods with methods from religious studies, they study ambivalent “conversion narratives” by people engaged in the biomimicry movement, that is, proponents of “a practice that learns from and mimics the strategies found in nature to solve human design challenges, and find hope,” in the practitioners’ own words (Stradling and Hobbs 2023: 2). Zhou (2022) takes a starting point that more explicitly bridges Erin James’s narratological stories (within a “storyworld”) with Stibbe’s ecolinguistic stories. Through an analysis of a few narratives, she argues for the need to turn to “ecocentric storytelling in the post-epidemic storyworld” (Zhou 2022: 112). Via this study, we can turn to Jessica Hampton’s (2022) contribution which applies storytelling elements in a language revitalisation context. Hampton thus discusses “language erasure” of Emilian, a language spoken in Emilia Romagna in northern Italy. While such work would intuitively be categorised with the sociocultural ecological tradition, Hampton convincingly connects societal and linguistic belonging with belonging to a physical and natural environment, and she conjures that the loss of Emilian is connected with the disappearance of our co-living with a more-than-human nature, a theme also explored by Frayne (2019). On this background, Hamilton proceeds to use Stibbean ecolinguistics as an analytical tool that can be used for storytelling within language revitalisation contexts.

Hampton’s study further serves to emphasise the links between narratives and identity. Thus, as argued in her work, environmental identity – the identity that comes from belonging to a place – is shared within a community through econarratives. Unsurprisingly, the keywords ‘narrative’, ‘storytelling’, ‘identity’ and ‘environmental identity’ are all grouped in the same southeast corner of the map in Figure 1. Yet, if one takes a closer look at the Scopus dataset, there is clearly a distinct group of publications on identity that do not depend on narratological concepts or methods.

Accordingly, identity-oriented ecolinguistics is the fourth development included here. A few publications in this category are only superficially touching upon environmental issues, for which reason they would not meet the overall criterion for being placed in the group of studies that attend to the natural ecology of language. For instance, the article by Uryu et al. (2014) discusses intercultural interaction within a sociocultural ecology, and a recent article by Mo et al. (2024) also limits the environmental definition, at least analytically, to a sociocultural context – while elaborating on the theoretical model of timescales presented by Uryu et al. (2014). Given their focus on sociocultural issues, I will not survey such studies in this context (e.g. Lankiewicz 2021; Liu et al. 2023; Peng 2023).

A large group of the studies focusing on identity extrapolate methodologically from discourse-oriented ecolinguistics, which implies that identity is used in the discursive sense of being linguistically and socially constructed. For instance, Li and Fontaine (2023) study corporate ecological identities in a Chinese context, and Lei Lei (2021) develops a theoretical model to study ecological identity based on systemic functional linguistics. Similarly, scholars have studied how poetry expresses ecological identity as well as identity conflicts and identity loss. For instance, Molnár-Bodrogi (2023) compares two Finno-Ugric poets writing on their natural surroundings in northern Norway and in Moldavia (Romania), and Perangin-Angin and Dewi (2020) examines how the preservation of folksongs in the Pagu language at the island of Halmahera (Indonesia) contributes to both language preservation and to upholding the identity of the Pagu ethnic group. Poole and Spangler (2020) take it a step further, as they attend to identity processes in digital gaming where identities of avatars are designed by players in an act of self-construction. They analyse a single game, Animal Crossing: New Leaf, in which “ecologically responsible actions” are only carried out “to enable their consumption of goods and resources within the game” (Poole and Spangler 2020: 353).

The most innovative of this wave of studies focusing on identity in an ecolinguistic context, is Nadine Andrews’s (2018) methodological contribution to ecopsychology. Andrews points out that nature connectedness, that is, “the subjective feeling of being in connection with, part of, or associated to, the nonhuman natural world” (Andrews 2018: 61), is not a stable personality or identity trait, but rather a fluctuating and highly situated state. By using tools from ecolinguistics, alongside interpretative phenomenological analysis, she demonstrates how close attention to interviews can be used to gauge participants’ experiences of nature connectedness, or the lack thereof. Andrews concludes that “language that promotes the nonhuman natural world as an object, that abstracts and homogenizes living beings and their habitats, that encourages seeing nature as external and separate, and that primes us to be fast and busy could all be factors working against strengthening ecological identity and contributing to inconsistencies in felt sense of connectedness with nature” (Andrews 2018: 68). While one can discuss the causality ascribed to language here, Andrews’s study demonstrates that language can be used as a “thermometer” that gives us an insight into how speakers relate to their environment. As such, language awareness can be made to go hand in hand with a sense of belonging and connectedness: “Cultivating an ecological identity that centers on an embodied relationship with a place and its inhabitants requires time and attention and patience” (Andrews 2018: 69).

7 Ethno-lexical ecolinguistics

We have now, with one exception, covered all clusters in the centre of the map. The exception is the red cluster immediately north of ‘ecolinguistics’. This clusters covers many generic keywords (e.g. ‘ecolinguistic’, ‘cultural studies’, ‘language & linguistics’ and ‘linguistics’) and many keywords that we have already discussed (e.g. ‘news discourse’, ‘corpus-assisted discourse analysis’, and ‘ideology’). The remaining keywords in this cluster have one thing in common: they all stem from work that originates in Indonesia, for which reason this subsection is dedicated to surveying Indonesian ecolinguistics. In line with my methodological limitation of relying on the Scopus dataset, I will ignore many contributions that are not published in sources indexed by Scopus. For comparison, Dimensions trace 86 documents on ecolinguistics to Indonesia, whereas Scopus only lists 30 documents. I have already included quite a few of these within the relevant themes mentioned here (for instance, Nurhayani’s study of Indonesian and Malaysian folktales, or Istianah and colleagues’ corpus-based study of websites for promoting tourism). While the articles discussed below may come over as representatives of a more unique Indonesian line of thought in ecolinguistics, it goes without saying that those already covered are equally representative for Indonesian ecolinguistics.

Whereas the dominant European tradition of ecolinguistics was described with the keyword collocation of ‘critical discourse analysis’ and ‘climate change’, the main Indonesian collocation is ‘lexicon’ in combination with any of the terms ‘flora’, ‘plant’, ‘forest’, and ‘ethno-botany’. Accordingly, this line of work exhibits a deep commitment to understanding how naming practices contribute to the organisation of the human-nature interface. It is for this reason that I have adopted the term ethno-lexical ecolinguistics.

To illustrate, let us consider the study by Abida, Iye, and Juwariah (2023) which appears to be quite representative for the work done in this tradition. First, they focus on a single area and community, in this case the East Java province in Indonesia. Second, within this setting, the authors collect language data from published work, just as they use interviews with and participatory observations of farmers, local residents, and community figures. Third, they analyse the collected data using semantic methods and a mixture of (undefined) qualitative and quantitative methods, as well as an (undefined) “ecolinguistic approach” to “understand the ecological lexicon of the East Java community and its relationship with the natural environment” (Abida et al. 2023: 3). Unfortunately, the analytical procedures are not elaborated, for which reason the analysis remains a black box procedure.

However, the authors identify and present numerous terms that are said to reflect values of community and cooperation (e.g. “gotong royong”, or communal work), and harmony between farming practices and the environment, including systems of communal irrigation systems (“subak”). This focus on the ecological lexicon of East Java communities allows the authors to conclude that “this diverse and distinctive lexicon not only originates from the community’s engagement with the natural surroundings but also mirrors profound cultural beliefs and indigenous knowledge in conserving biodiversity and ecology in East Java” (Abida et al. 2023: 15). This emphasis on the entanglement of nature, indigenous knowledge, and cultural beliefs is at the core of the ethno-lexical tradition. Importantly, this entanglement implies that “[human] communities also play a significant role in maintaining ecosystem balance and environmental sustainability” (Abida et al. 2023: 2).

The same theme of human-nature coexistence surfaces in a strong study on forest conservation by Prastio et al. (2023). Their focus is on the Anak Dalam Jambi Tribe. They live in the forests of Sumatra, a biotope being heavily diminished due to corporate plantation and mining activities, activities that have also impacted on the tribe’s way of living. Relying on interviews with carefully selected informants, this study focuses on the ecological lexicon and its relations to ideological, biological, social, and cultural aspects of the Anak Dalam Jambi Tribe’s forest conservation efforts. The study explicates, again, the sense of entanglement between the tribe members, the forest as a natural habitat, and their ancestors in this area. The ancestral dimension is important here, because it emphasises what is termed a “conservation-centric life ideology” (Prastio et al. 2023: 15). This attitude to preserve, replant, and protect the forest (e.g. by avoiding over-harvesting) runs through the entire study, and it is closely related to the attitudes to both self and others. Thus, as one informant says, the tribe is guided by three values: “harmony with oneself (such as honesty, gratitude, diligence, patience, and religiosity), with fellow humans (justice, avoiding conflicts, non-violence), and with the forest environment itself (avoiding the use of certain chemicals and refraining from excessive harvesting)” (Prastio et al. 2023: 19). Preserving the biotope is also a means for self-preservation.

Luardini et al. (2019) demonstrate how the Dayak Ngaju community members rely on healers/shamans experienced with “nikap and mimpun tatamba ‘seeking and finding medicine (plants)’” (Luardini et al. 2019: 79). In their study, they complement the focus on the ecological lexicon with studies of ritual language, and they conclude that “for the Dayaks the environment is not simply the natural world; nor is it different from a metaphysical world: the two are inseparable” (Luardini et al. 2019: 83). Along similar lines, Hestiyana and colleagues (2024) attend to the flora lexicon for the reproductive health among the Tetun tribe in the East Nusa Tenggara Province; Roekhan and colleagues (2024) study plant-based ethnomedicine practices in the Sarolangun Malay community in the Jambi province on Sumatra; and Nahak and colleagues (2019) explore how speakers of Tetun Fehan on Timor organise a set of ecological activities around Batar, a lexicon of terms pertaining to the planting and harvesting of corn.

All these studies attest to the importance of “local wisdom” or “ecological wisdom” (which both are keywords in this red cluster). This theme is explored by Kardana and colleagues (2022) who outline how local wisdom is organised in a Balinese context. Focus fall on similes marked by “buka or cara ‘like or as’” (Kardana et al. 2022: 139) which are seen as markers of local wisdom “stored” in language. Within a Balinese context, this local and ecological wisdom is preserved inter-generationally within the awig-awig, the Balinese customary law. This is the topic of two articles by Umiyati (2020, 2023). She demonstrates that part of the awig-awig pertains to flora and fauna, but since the customary regulations are under pressure due to social developments, these parts of the awig-awig are on the decline. To document the nature-oriented awig-awig, Umiyati adopts a lexicon-oriented approach to ecolinguistics. Finally, Astawa and colleagues (2019) study how Hindu practices under the name of Tri Hita Karana (that is, the spiritual, the social, and the natural dimensions of the environment) have entered the Balinese awig-awig. The authors draw on evaluation theory and appraisal theory. However in doing so they propose a critical ecolinguistic perspective that does not achieve much more than stating that beneficial evaluations should be preserved, while destructive ones should be resisted. Interestingly, the same modus operandi – establishing an eco-lexicon from observation-based data – is also applied in settings far removed from the indigenous ones mentioned above. For instance, Khotimah and colleagues (2021) study the health eco-lexicon related to COVID-19.

In summary, the Indonesian tradition of ethno-lexical ecolinguistics opens up new research avenues in ecolinguistics, especially with its focus on how language is a factor in preserving local and ecological wisdom on nature – which is not just “nature” in a Western understanding, but a conglomerate of biological, spiritual, and social forces. Scholars in this tradition demonstrate the far-reaching consequences of perceiving human beings and communities as insiders to nature, not its intruders. That said, much of the work surveyed here suffers from some methodological shortcomings, either because the lexical method is too narrow, or because it is complemented by Western theories that do not do justice to the topics under scrutiny. Those shortcomings, however, are not the only explanation of the fact that this work has not been taken up outside of Indonesia. There seems to be a certain blindness towards this body of work in Western ecolinguistics.

8 Ecological and harmonious discourse analysis

This section moves north, both geographically from Indonesia to China and on the map in Figure 1. However, the northbound movement from the red cluster towards ‘ecological discourse analysis’ will be supplemented by a movement to the southwest yellow cluster. While Indonesian ecolinguistics have developed through studies of very diverse Indigenous communities, but without much theoretical advancement, Chinese ecolinguistics has undergone interesting theoretical developments. Work on the ecology of language in the Haugenian sense appeared in China as early as in the mid-1980s, where it was explored by Zheng Tongtao and Li Guozheng, a body of work that I will not attend to here (for details, see Huang and Zhao 2021; Zhou 2021). In the mid-2000s, however, Fan Junjun and Wang Jinjun introduced Hallidayan ecolinguistics in China, and a decade later – in the mid-2010s – ecolinguistics became an established discipline in China, primarily through the work by Huang Guowen and He Wei and their collaborators. This subsection will survey recent developments in Chinese ecolinguistics in two stages: the first focuses on ‘ecological discourse analysis’, and the other on ‘harmonious discourse analysis’, ‘landsenses ecology’, and ‘linguistic landsense ecology’.

Ecological discourse analysis originates from what one can call the Beijing school in ecolinguistics, centering on the work by He Wei (the president of the China Association of Ecolinguistics) at the Beijing Foreign Studies University (but other universities in the Beijing area and beyond are also active in this domain). For obvious reasons, much work on ecological discourse analysis is written in Chinese, which sadly is beyond my linguistic skills. Accordingly, I have to rely on the few English sources, including Cheng’s (2022) summary of the Chinese monograph New Developments of Ecological Discourse Analysis by He et al. (2021).

Ecological discourse analysis is theoretically anchored in Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics. This comes to the fore, for instance, in Zhang and He’s (2020) detailed account of the Chinese transitivity system as a method for analysing people-place interactions. Ecological discourse analysis relies on the Stibbean ecosophic framework by adding an explicit ecosophical dimension. Zhang and He develop an ecosophy of “Ecological Sense of Place” (Zhang and He 2020: 220) which emphasises the concrete emplacement of living agents, and other contributors to ecological discourse analysis are guided by principles of “Diversity and Harmony, Interaction and Co-existence” which “combines the traditional Chinese culture and philosophy, including Confucianism, Daoism, and Mohism, together with modern Chinese diplomatic ideas” (Cheng 2022: 191). In order to operationalise the ecosophical concerns for the preservation of life, avoidance of suffering, and peaceful coexistence (Ma and He 2023: 207–208), the ecosophy is, somewhat peculiarly, formulated as four Searle-inspired maxims. Ecological discourse analysis consists of three steps: It proceeds from, it seems, a more case-based methodological framework (ecosophy plus linguistic theory) than other approaches; then it conducts a discourse analysis in order to “reveal the ecological orientation and the hidden reasons” before it outlines guidelines for “people’s ecological behaviors” (Cheng 2022: 191).

Many case studies illustrate ecological discourse analysis, including the already mentioned study on British and Russian news reports on the “Sino-US trade war” by Cheng and He (2021). Ma and He (2023) study statements made within a United Nations context by Chinese and American diplomats, emphasising one systemic functional aspect, namely the thematic metafunction, and Wei Rong (2021) develops a detailed framework for dealing with the interpersonal metafunction in her study of discourse from the international political sphere. Other studies include Xue and Xu’s (2021) study of the appraisal system in two major Western mainstream media’s coverage of COVID-19 in China; Wang, Zhai, and Zhao’s (2019b) study of the UN secretary-general’s statements on climate change; Zhang and Cheng’s (2024) study on reports about wandering elephants in the newspaper China Daily; Wang, Hu, and Zhai’s (2019a) analysis of President Xi’s ecological viewpoints expressed in the book Xi Jinping’s Comments on Socialism Ecological Construction; Zuo’s (2019b) analysis of reports from a national congress of the Communist Party of China; and finally Zhang and Sandaran’s (2024) study of mental processes (within the transitivity system) of a TV documentary on the Shaanxi Province in China. The final development to be mentioned here is the development in an Italian context of an ecological discourse analysis aimed at texts in Chinese. Brombal, Conti, and Szeto (2024) have developed this framework which aims at analysing lexical patterns in a way that is quantifiable and hence allows for corpus-assisted analysis.

The Chinese framework of ecological discourse analysis is theoretically rigorous and provides a varied and sensitive apparatus for conducting detailed linguistic analyses. Yet, the ecosophical superstructure of sorting statements into beneficial, neutral, or harmful appears less integrated, and the theoretical movement from theory, over analysis to guidelines for ecological behaviour is at best found in an embryonic state only. As argued by Steffensen et al. (2024a), attending to symbolic structures does not come with a principled view on how such structures impact on behaviour: “It obscures the question of how the living world is affected by languages, linguistic knowledge, practices and languaging” (Steffensen et al. 2024a: 11).

I now turn to harmonious discourse analysis, which quite obviously is another contribution to the array of discourse analyses (critical, positive, ecological). However, it originates from what one could call the Guangzhou school of ecolinguistics, initiated by another systemic-functional linguist, Huang Guowen. Huang’s career pivots around two Guangzhou institutions, the Sun Yat-Sen University and the South China Agricultural University, where he founded the Center for Ecolinguistics in 2016. While this tradition also comprises work that would be categorised as focusing on sociocultural ecology (e.g. Mo et al. 2024), I will here exclusively focus on work that pertains to the natural ecology, starting from Huang and Zhao’s introduction (Huang and Zhao 2021).

Harmonious discourse analysis shares many features with ecological discourse analysis, in particular its heavy reliance on systemic functional linguistics as a methodology for describing discourse. However, in many central respects, the two approaches differ. Most importantly, whereas ecological discourse analysis has adopted an analytical style that resembles critical discourse analysis of the Western discourse-based tradition (albeit with different ecosophical “plug-ins”), harmonious discourse analysis presents a different analytical strategy altogether. The argument for this innovation is that not only the ecosophical component, but the entire analytical procedure must adapt to local concerns, and hence to the specific local research questions that emerge from local contexts. On this view, a general and universally applicable ecosophy is not a valid starting point without “due attention to the contextual elements of culture and tradition, political and economic backgrounds, historical factors, and society’s general values, which are inseparable from the understanding of one’s ecosophy” (Huang and Zhao 2021: 5).

In order to develop a less idealistic stance, Huang and Zhao (2021: 2) starts from two research constraints, namely that it must exhibit social adequacy and environmental adequacy. They adopt this pair from Larson (2018) who in turn adopted them from Harré et al. (1999). On my reading, the innovative move in harmonious discourse analysis is that it coherently deduces both types of adequacy from the same philosophical enterprise, namely what they term Chinese humanism:

Chinese humanism differs from Western humanism in that “Chinese philosophy does not talk about humanism without nature, nor is its tradition of humanism located in a contradiction between human and nature: rather it develops humanism in the context of harmony between human and nature”. (Huang and Zhao 2021: 8)

This Chinese humanism is derived from, traditional Chinese philosophies, in particular Confucianism and Taoism. They both emphasise the interconnectedness of human beings and the rest of the universe, not merely in the superficial sense that human and nature are in a life-sustaining relationship with one another, but rather in the sense that as natural beings, humans are bound to take an intrinsically anthropocentric perspective.

Another crucial difference is that harmonious discourse analysis aligns with the desideratum of Steffensen and Fill (2014: 17), namely that ecolinguistics must take a principled stance on how it understand language as part of nature. This contrasts with the discourse-oriented tradition that tends to adopt a largely post-structural view on language, along with the methodological tools that are associated with it. Huang and Zhao (2021: 6) adopts the systemic functional argument that language is part of nature because it is part of a semogenetic development that creates a continuity between physical systems, biological systems, social systems, and semiotic systems. Finally, it is worth pointing out that Huang and Zhao explicitly evoke the Marxist roots of systemic functional linguistics – more so than most other ecolinguistic work that draw on Halliday. It is noteworthy because it contributes to a theoretical coherence between the linguistic, the social, and the environmental focuses found in harmonious discourse analysis.

There are still only few publications in English by scholars working in the harmonious discourse tradition. In a recent article, Ha et al. (2024) picks up the baton from Huang and Zhao who explicitly emphasised that “ecoliteracy, or ecological education in a broader sense, is another research domain as well as the ultimate purpose of HDA [i.e. harmonious discourse analysis]” (Huang and Zhao 2021: 15). The active promotion of ecological education is pursued by Ha and colleagues who set out to use harmonious discourse analysis to identify key pathways to developing ecoliteracy in a Chinese context. For the authors, the purpose of “ecoliteracy is to awaken people’s ecological awareness, deepen their understanding of ecological crises, and encourage them to gain ecological knowledge actively” (Ha et al. 2024: 3). In their work, they use questionnaire methods to identify the most important formative factors in creating ecoliteracy.

The most interesting development within harmonious discourse analysis, however, is the transdisciplinary integration with the uniquely Chinese development of landsenses ecology. Landsenses ecology is a new approach to landscape ecology, which according to Clark (2010: 34) is “the study of the pattern and interaction between ecosystems within a region of interest, and the way the interactions affect ecological processes, especially the unique effects of spatial heterogeneity on these interactions”. Landsenses ecology was first suggested by Zhao and colleagues (2016: 293) who defined “landsenses ecology as a scientific discipline that studies land-use planning, construction, and management toward sustainable development, based on ecological principles and the analysis framework of natural elements, physical senses, psychological perceptions, socio-economic perspectives, process-risk, and associated aspects.” It is primarily the inclusion of the perceptual component that makes landsenses ecology stick out, and the authors use this in a very wide sense: “Psychological perceptions include some elements of religion, culture, vision, metaphor, security, community relations, well-being, etc.” (Zhao et al. 2016: 293).

In the past few years, the unique environment of having a ecolinguistics center at an agricultural university has given rise to the integration of harmonious discourse analysis and landsenses ecology. This work is published in a series of four articles by Zhang et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2022). Through this integration, they suggest the concept of linguistic landsenses which refers to “a meaning carrier that contains one or more of speakers’/designers’ visions through appropriate forms of manifestation, through which listeners/readers can graft, understand and resonate with the visions, thus forming a common code of conduct” (Zhang et al. 2021b: 11). In this way, harmonious discourse analysis becomes a tool for scaffolding ecological planning in ways that prompt pro-environmental behaviour by affecting people’s perceived self-efficacy, environmental knowledge, and environmental concern. Thereby, as the authors suggest, linguistic landsenses ecology “provides a feasible theoretical framework and empirical research method for the study of the relationship between the language system and the ecosystem from micro to macro levels” (Zhang et al. 2022: 650). The connection between harmonious discourse analysis and landsenses ecology is promising, and it deserves to be explored further in ecolinguistics. However, the theoretical framework suffers from one central weakness that needs to be addressed in future work, namely its reliance on psychological literature and models that are arguably outdated. In this respect, there is a potential in linking linguistic landsenses ecology to the cognition-oriented advances in ecolinguistics that will be explored in the next section. A similar objection is indirectly underlying Zou’s (2021) discussion of the framework, because he turns to “eco-cognition” and suggest to see that as a mechanism of harmonious discourse analysis. While Zou draws heavily on Chinese philosophy, he also explicates the links to an interactive understanding of cognition as it has appeared in work from western traditions, including work by Gibson (1979).

9 Cognitive ecolinguistics

The previous section ended in the far southwest corner of the map in Figure 1, and we will now move to another peripheral area in the map, the orange cluster to the far west. Given how VOSviewer organises these maps, it is important to note that the periphery of the map either represents research contributions that are well-established but far from the more central mainstream, or recent work that explores new directions in the field. Harmonious discourse analysis and landsenses ecology are both such new directions in respect to ecolinguistics, and the same goes for the body of work that I will attend to in this section. It pertains to recent developments in ecolinguistics that draw on cutting-edge developments in cognitive science and adjacent fields of research.

There has always been an intimate connection between linguistics and cognitive science. Indeed, when the latter was first coined in the plural (as cognitive sciences), linguistics was one of the six disciplines within this umbrella. Accordingly, when cognitive science in the 1950s and 1960s was preoccupied with descriptions of behaviour as the output of computational processes in a neural machinery (in line with the overarching mind as machine metaphor, as outlined by Boden (2006)), linguistics adopted a similar model of how language was generated: “in the technical sense, linguistic theory is mentalistic, since it is concerned with discovering a mental reality underlying actual behaviour” (Chomsky 1965: 4). After the linguistics wars in the 1970s (Harris 1993), cognitive linguistics developed in parallel to a new and more embodied view on cognition. This view replaced symbolic models of the human mind with connectionist models (cf. Langacker 1991: 525–534), just as it linked Eleanor Rosch’s prototype categorization theory (cf. Lakoff 1987: 39–67) with the notion of embodiment.

In recent years, a third generation of cognitive science has emerged. It challenges the age-old ontological distinction between an inner mind and an outer world. On this view, cognition is an integrated process that takes place across the brain, the body, and the extracorporeal environment. Thus, rather than localising cognition in the brain or the mind, it is seen as a non-local phenomenon (Steffensen 2015) that emerges as whole bodies engage with the surroundings in a vibrant cognitive system. Key contributors to this development are James Gibson (ecological psychology), Humberto Maturana and Francesco Varela (enactivism), and Ed Hutchins (distributed cognition). In recent years, this line of work has made it into linguistics where it appears as an unorthodox reconsideration of the main tenets of the discipline. Going into this literature is beyond the purpose of this survey, but today there are rich traditions of Gibsonian ecological linguistics (Raczaszek-Leonardi et al. in press), enactivist accounts of language (Di Paolo et al. 2018), and a distributed language perspective (Cowley 2011; Steffensen 2015; Thibault 2021).

These developments have also affected ecolinguistic theorising. In the late 2000s, Lechevrel (2010: 69) observed that the ecological approaches in linguistics parallel those in cognitive science, and Steffensen (2008) discussed how this new wave in cognitive science could be used for the description of linguistic structures. In the 2010s and 2020s, these perspectives became more and more articulated in ecolinguistics. Steffensen and Fill reviewed this line of work in a section on “the cognitive ecology of language” (Steffensen and Fill 2014: 14–15), and several contributors to their 2014 special issue pursued this perspective. Most notably, Hodges (2014) took a Gibsonian approach to understanding language as a values-realising activity, and Cowley (2014) pursued a distributed perspective under the rubric of languaging, that is, the dynamic and other-oriented activity that emerges as human beings engage with each other and with their joint environment. To Cowley, languaging is a “symbiosis of the biotic and the cultural” (Cowley 2022: 2), and as such it links to Halliday’s concept of semogenesis because it meshes the agency of speakers with the constraints of what linguists have described as language systems. Likewise, sensorimotor languaging – what people do – connects language and environment, because “languages (i.e. lexicogrammars and usage) impact on bioecologies (and human parts) through cultures and cognitive ecosystems” (Cowley 2022: 17). The concept of bioecologies is key in this line of work, because it indexes concrete, emplaced consortia of organisms, rather than abstract ecosystems.

Taking a starting point in the cognitive dynamics of living organisms – rather than in texts, discourses, or abstract systems – is also at the heart of Steffensen and Fill’s (2014) proposal of a theoretical framework that unites the various ecological strands in linguistics, and it also informs the contributions of Li et al. (2020) and Steffensen and Cowley (2021). The former pursues a naturalised view of language, that is, one which anchors language in the materiality and corporeality of living, physical bodies, and not in semiosis or disembodied meaning. The latter evokes Chemero’s (2009) radical embodied cognitive science, which rejects the notion of mental representations, and shows how ecolinguistics can be construed as a radical embodied perspective on language. The distributed perspective also informs Steffensen’s (2018) contribution to The Routledge Handbook of Ecolinguistics, as well as many of Cowley’s publications in which he pursues semiotic (Cowley 2023), biosemiotic (Cowley 2018), and (to a limited degree) dialogical (Cowley 2024) aspects of ecolinguistics. Liu et al. (2021) also pursue a distributed language perspective in their insightful discussion of lexicographical studies in ecolinguistics, and the perspective also comes to the fore in a recent edited volume on Language as an Ecological Phenomenon (Steffensen et al. 2024a, 2024b).