Nano particle loaded EZH2 inhibitors: Increased efficiency and reduced toxicity for malignant solid tumors

-

Yunyun Guo

, Yang Liu

und Lixiang Xue

Abstract

Background and Objectives

Aberrant upregulation or mutations of EZH2 frequently occur in human cancers. However, the clinical benefits of EZH2 inhibitors (EZH2i) remain unsatisfactory for majority of solid tumors. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new strategies to expand the therapeutic benefits of EZH2i. Nanocarriers have gained increased attention due to their advantages of prolonged blood circulation, enhanced cellular uptake, and active targeting capabilities. This study aims to address the challenges of EZH2i GSK126’s limited efficacy and severe adverse effects against solid tumors.

Methods

A nano delivery system was developed by encapsulating GSK126 within albumin nanoparticles (GSK126 NPs).

Results

The prepared GSK126 NPs exhibited a small spherical core with an average diameter of 30.09 nm ± 1.55 nm, high drug loading capacity (16.59% ± 2.86%) and good entrapment efficiency (99.53% ± 0.208%). GSK126 NPs decreased tumor weight and volume in the B16F10 xenograft mice, while such effects were not observed in the free GSK126 group. Subsequently, histological analysis demonstrated that GSK126 NPs significantly alleviated lipid-associated liver toxicity. Additionally, GSK126 NPs can partially counteract the effects of GSK126 on MDSCs, particularly by decreasing the infiltration of M-MDSCs into tumors.

Conclusions

Albumin-based EZH2i NPs have potent anti-cancer efficacy with tolerable adverse effects, providing promising opportunity for future clinical translation in treating solid tumors.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) is a highly conserved multicomponent transcriptional repressive complex possessing histone methyltransferase activity, which is responsible for catalyzing the trimethylation on H3K27 (H3K27me3). This modification results in the transcriptional silencing of target genes.[1, 2, 3] EZH2, as the core catalytic subunit of PRC2, plays a crucial role in numerous cancers, such as breast cancer (BC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and gallbladder cancer (GC), by promoting tumorigenesis, proliferation, invasion, metabolism, and suppressing antitumor immunity.[4, 5, 6, 7, 8] Inhibition of EZH2 enzymatic activity has emerged as a promising strategy in cancer therapy, with small molecule inhibitors such as EPZ-6438 (Tazemetostat) or GSK126 demonstrating significant antitumor efficacy both in vitro and in vivo.[9,10] Notably, the FDA has approved Tazemetostat for the treatment of advanced epithelioid sarcoma and highly aggressive EZH2 mutations diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and ongoing clinical trials are assessing the therapeutic potential of EZH2 inhibitors in various clinical applications.[11] Despite encouraging results in certain hematological malignancies, including DLBCL and follicular lymphoma (FL), the clinical efficacy of EZH2i remains unsatisfactory in the treatment of solid tumors.[12, 13, 14, 15, 16] This limited effect may be attributed to factors such as poor water solubility, lack of tissue specificity, disturbance of metabolic profiling and immune landscape as well as shorter half-life.[16, 17, 18] Besides, the tumor microenvironment (TME) in hematologic malignancies and solid tumors includes vascular structures, extracellular matrix, and resulting hypoxia, which can affect drug targeting and accumulation at the tumor sites.[19] Therefore, the development of novel strategies is imperative to enhance the therapeutic benefits of EZH2i against a broad spectrum of solid tumors.

Nanoparticle (NPs) based drug delivery systems offers several advantages in cancer treatment, such as improved pharmacokinetics, targeted delivery to tumor cells, reduced side effects, and overcoming drug resistance. The NPs used in medical applications often possess specific sizes, shapes, and surface characteristics, as these factors significantly impact the efficiency of nano-drug delivery and thus influence therapeutic effectiveness. Cancer therapy is typically deemed appropriate for particles with tumor diameter ranging from 10 to 100 nm due to their capacity to accumulate at the tumor site via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.[20,21] With high binding capacity and biocompatibility, albumin-based NPs carrier systems represent an attractive strategy for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs.[22,23] Previous investigations have shown that albumin specifically recognized the albumin receptor (gp60), initiating its active internalization and transportation in endothelial cells.[22] Furthermore, albumin-based NPs also could bind with SPARC (secreted protein acidic and cysteine rich), leading to the accumulation of chemotherapeutics in intratumor.[24] Inspired by the improvement of albumin-bound paclitaxel (Abraxane®) in pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and anticancer efficacies, we hypothesize that albumin-bound EZH2i NPs may improve the efficacy and reduce the side effect, therefore leading to expand the therapeutical potential from hematological malignances to solid tumors.[25]

In this study, we found that EZH2i had compromised efficacy against solid tumors, accompanied with the notable side effects, such as reduction in body weight, impaired immune function, and hepatic lipid accumulation. Subsequently, we developed a nano delivery system by encapsulating GSK126 within albumin nanoparticles (GSK126 NPs) to explore the therapeutical potential on solid tumors. The GSK126 NPs significantly decreased tumor weight and volume in B16F10 xenograft mice without evident systemic toxicity. Additionally, GSK126 NPs can partially ameliorate the induction effects of GSK126 on MDSCs, particularly by reducing the infiltration of tumor-infiltrating M-MDSCs. These findings not only offer a safe and robust drug delivery for EZH2i NPs in cancer therapy, but also suggest promising opportunity for future clinical translations in treating solid tumors.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

GSK126 and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA)., and the purity was determined to be 99.5% based on high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Gibico-BRL (Grand Island, NY, USA). Antibiotics and trypsin were from Macgene (Beijing, China). De-ionized water was obtained from Milli-Q system (Burlington, MA, USA). CD45, CD3, CD11b, Gr-1, and Ly6G flow antibodies were from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Coumarin-6 and β-cyclodextrin were from Sigma-Aldrich (Diegem, Belgium)

Mice and cell lines

Female BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice (4 weeks) were purchased from the Department of Laboratory Animal Science of Peking University Health Science Center, and maintained under SPF conditions in a controlled environment of 22°C–25°C approved by the Ethical Guidelines of EIACUC-PKU (A2021230). Mice were kept for 48 h to acclimatize to environment and fasted overnight before treatment.

Murine Melanoma B16F10, 4T1, MC38 cells were obtained from Peking Union Medical College, Cell Bank (Beijing, China). Cells were routinely maintained in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Cell proliferation assay

Tumor cells were seeded in 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 103/well and treated with GSK126 of indicated concentration for 36 h. The cells were imaged using phase contrast channel in the Incucyte S3 platform (Sartorius, Göttinggen, Germany). Four sets of phase contrast images from distinct regions within each well were taken at intervals of 3 h using a 10× objective. Incucyte S3 image analysis software was set to detect the edges of the cells and to determine their confluence in percentage.

Tumor xenograft experiments

Tumor cells (5 × 105) were injected into the flanks of 4-week-old BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice to generate xenografts. When tumors reached approximately 100 mm3 in size 5 days later, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of GSK126 or GSK126 NPs daily at a dose of 50 mg/kg. Tumor volume was determined every day by measuring the two perpendicular diameters of the tumors and using the equation V = length (mm) × width (mm)2/2 (Eqn. 1), and the body weight was recorded every day. After treatment, mice were euthanized with CO2, then tumors were weighted and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for further studies.

RNA sequencing and data processing

RNA sequencing and data processing followed the methods detailed in our previous publication.[18] Briefly, B16F10 cells were treated with DMSO or GSK126, and total RNA was extracted. Paired-end libraries were prepared and sequenced on the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform. Reads were aligned to the GRCm38.p4 genome using Hisat2, and RPKM values were calculated. Differential gene expression analysis was performed with edgeR, defining significant differential expressions by FDR-adjusted P values < 0.05 and log2 fold change > 1.0. Gene enrichment analysis for Gene Ontology and KEGG pathways was conducted using gene set enrichment analysis software. The RNA-seq data for this paper is available at NCBI GEO: GSE163078.

Preparation of GSK126-loaded albumin NPs

GSK126-loaded albumin NPs were prepared by a desolvation methods as previously reported.[26,27] Briefly, albumin (20 mg) was completely dissolved in distilled water (2 mL) and was titrated to pH 8.0 with NaCl (0.1 mol/L). Then GSK126 dissolved in ethanol was dropped into the albumin solution under constant stirring. Afterward, glutaraldehyde (8%, 10 μL) was added and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 8 h. The purified GSK126-loaded albumin NPs were obtained after evaporation and ultrafiltration, and stored at 4℃ for further use.

Estimation of entrapment efficiency and drug loading capacity

The entrapment efficiency (EE) and drug loading capacity (LC) of GSK126 was determined using an indirect method, which involves measuring the amount of free drug available in nano dispersion. The standard curve for GSK126 was established by preparing a series of GSK126 solutions with concentrations ranging from 4 to 20 μg/mL. Subsequently, the absorbance values of these solutions were measured at 280 nm using a UH5300 UV-Visible spectrophotometer, and a standard curve for GSK126 was plotted. Utilizing an indirect method to evaluate the encapsulation efficiency and drug loading, the solution derived from ultrafiltration in the nanoparticle purification process is diluted to an appropriate concentration. Following this, the absorbance at 280 nm is measured to quantify the unbound GSK126 content based on a standard curve. The encapsulation efficiency (EE%) and drug loading capacity (LC%) are then calculated using the provided equations.

Characterization of prepared GSK126 NPs

The mean particle size and size distribution of NPs were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (ZEN1690 Zetasizer Nano-S90, Malvern, UK). The intensity autocorrelation was measured at a scattering angle of 90° at 25°C. The freeze-dried samples were diluted to an appropriate concentration using normal saline and were transferred into a polystyrene cuvette for measurement. The zeta potential of NPs was detected using Zetasizer 2000 (Malvern, UK). The obtained freeze-dried samples were reconstituted and diluted to an appropriate concentration with normal saline before measurement. The morphology of prepared nanoparticles was investigated by transmission scanning electron microscope (TEM). Briefly, the nanoparticles were reconstituted with purified water. Then the nanoparticle suspension was dropped on a 200-mesh copper grid and was left to dry prior to measurement.

Intracellular localization of NPs

For intracellular localization analysis, coumarin-6 was used as a model fluorescent dye. B16F10 cells were seeded in confocal dishes (5 × 104 cells/well) and cultured overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Subsequently, the culture medium was removed and the cells were washed with PBS for three times. Then, the cells were treated with serum-free medium containing BSA or coumarin-6 NPs at a concentration of 200 ng/mL. The cells were then incubated in the dark at 37°C for 6 h. Following this incubation, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were washed three times with cold PBS before being stained with Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/mL) for nuclear staining. Then, the cells underwent three washes with cold PBS, were sealed with phenol red-free medium, and promptly examined under a laser confocal microscope. Specifically, the excitation and detection wavelengths for coumarin-6 were 467 nm and 502 nm, respectively. For Hoechst 33342, the excitation and emission wavelengths were 345 nm and 461 nm, respectively.

Mechanism of the cellular uptake of NPs

As a step forward, the mechanism of cellular-uptake or endocytic pathway of NPs was determined as B16F10 cells (5 ×105 cells/well) were grown for 24 h in 6-well plates supplemented with 2 mL RPMI-1640 at 37°C with 5% CO2. Then, the cells were supplied with fresh medium containing 10 mM β-cyclodextrin (a known inhibitor of the Gp60/ caveolar transport) for 0.5 h; cells without the inhibitor pretreatment were used as controls. After treatment with the inhibitor, the cells were carefully washed with PBS for three times, and each group was further incubated with coumarin-6 NPs (200 ng/mL) at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 4 h. Then, the cells were collected and resuspended in PBS for flow cytometry analysis.

Oil Red O staining

After drug treatment, mice were sacrificed, and liver samples were excised and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound for histopathological analysis. The OCT-embedded samples were serially sectioned at 10 μm. Oil Red O staining was performed to evaluate lipid accumulation, and the results were photographed under a microscope.

Flow cytometry

For flow cytometric analysis of TILs, tumors were finely minced with a scalpel blade and enzymatically digested to obtain single-cell suspensions. Splenocytes were isolated through mechanical disruption. Subsequent antibody staining followed the manufacturer’s protocols.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times with triplicate. Statistical data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between different groups were carried out with Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) as appropriate using GraphPad Prism (ver. 8.0). Statistical comparison among groups was determined using Kruskal-Wallis test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*P <0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Results

GSK126’s limited efficacy with undesirable side effects

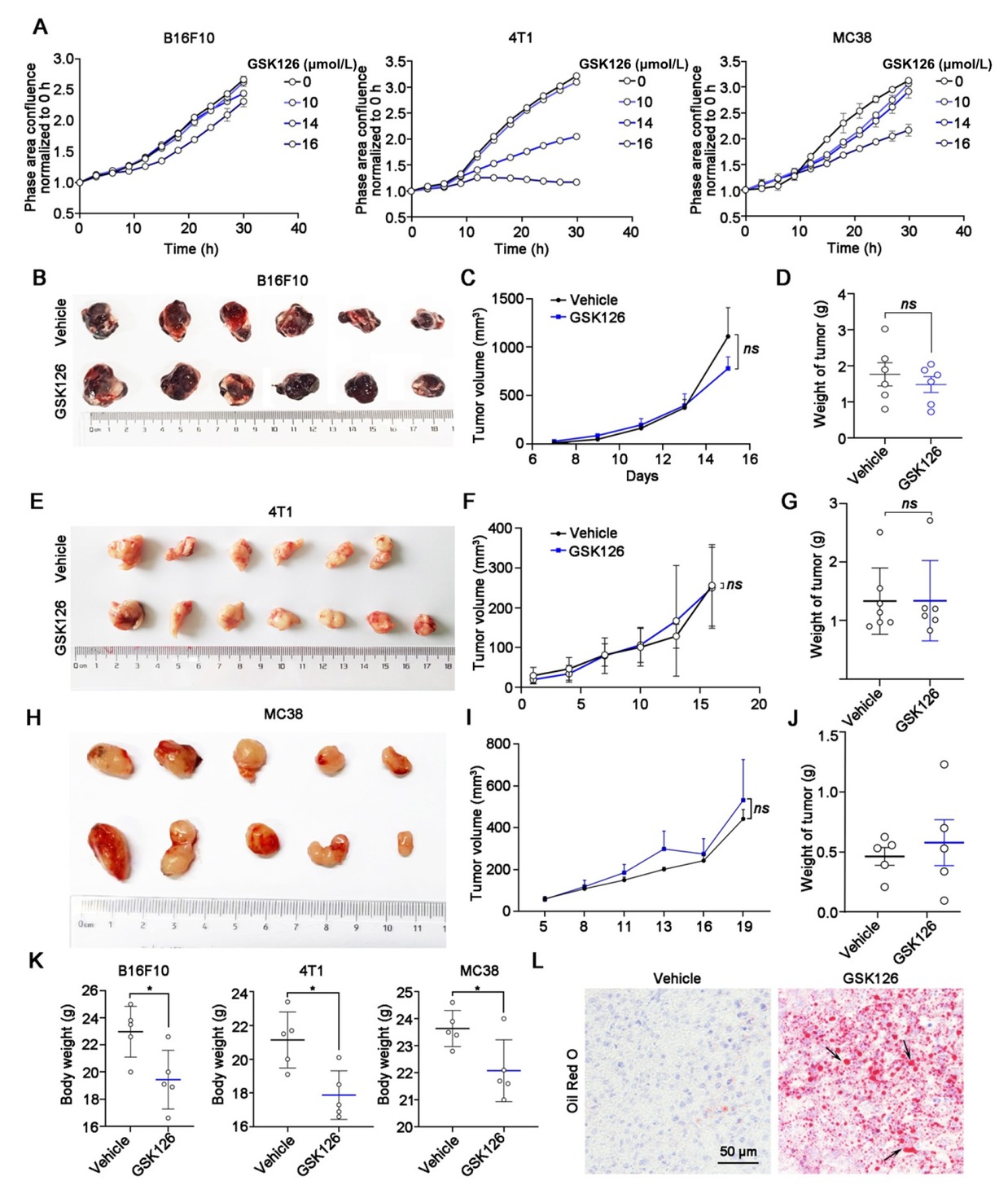

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the cellular response to EZH2 inhibition in various solid tumors, we employed the Incucyte S3 long-term dynamic cell image acquisition device to evaluate the proliferative kinetics of B16F10, 4T1, and MC38 treated with GSK126. Our analysis revealed that solid tumor cell lines displayed minimal inhibitory effects at a concentration of 10 μmol/L (Figure 1A). [18] Consistent with our previous studies, hematologic tumor cell lines exhibit higher sensitivity to GSK126 compared to solid tumors.[18] For the assessment of the in vivo antitumor efficacy of EZH2i, we established subcutaneous xenograft models of B16F10 and administrated GSK126 intraperitoneally at a dose of 50 mg/kg/d (Figure 1B). Despite the administration of GSK126, the tumorigenic capacity of B16F10 in vivo remained unaffected, as indicated by the consistent dynamics of tumor volume and weight (Figure 1C and 1D). Consistent with these findings, intraperitoneal administration of GSK126 also did not exhibit a significant inhibitory effect on tumor growth in C57BL/6 mice bearing breast cancer cell line 4T1 or colon cancer cell line MC38 xenografts (Figure 1E-1J). Notably, the group treated with GSK126 experienced a marked decrease in body weight (Figure 1K). Furthermore, Oil Red O staining of liver sections displayed a significant increase in lipid accumulation in the GSK126-treated group (Figure 1L). In addition, obvious inflammatory features such as peritoneal adhesions and ascites accumulation were found when dissecting mice treated with GSK126. Collectively, these findings suggest that EZH2i demonstrate limited effectiveness against solid tumors, as well as the undesirable adverse effects.

Efficacy of EZH2 inhibitor GSK126 in solid tumors. (A) Cell proliferation of B16F10, 4T1 and MC38 cells in GSK126 (10-16 μmol/L) treatment monitored by IncuCyte S3. Mean ± SEM is shown (n = 6). (B) Images, (C) tumor growth curve, and (D) tumor weight of mice bearing B16F10 in the vehicle group (n = 6) and GSK126 (50 mg/kg) treatment group (n = 6). (E) Images, (F) tumor growth curve, and (G) tumor weight of mice carrying 4T1 in the vehicle group (n = 6) and GSK126 (50 mg/kg) treatment group (n = 7). (H) Images, (I) tumor growth curve, and (J) tumor weight of mice carrying MC38 in the vehicle group (n = 5) and GSK126 (50 mg/kg) treatment group (n = 5). Tumor volume was measured with a vernier caliper every 2–3 days. Tumor volume = Length × Width × Width / 2. Tumor weights were measured at day 15. (K) Body weight of B16F10, 4T1, and MC38 xenograft mice. (L) Oil Red O staining of liver sections in B16F10 tumor-bearing mice of Vehicle and GSK126 treatment group. Data in (D), (G) and (J) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison posttest. ns, nonsignificant, *P < 0.05.

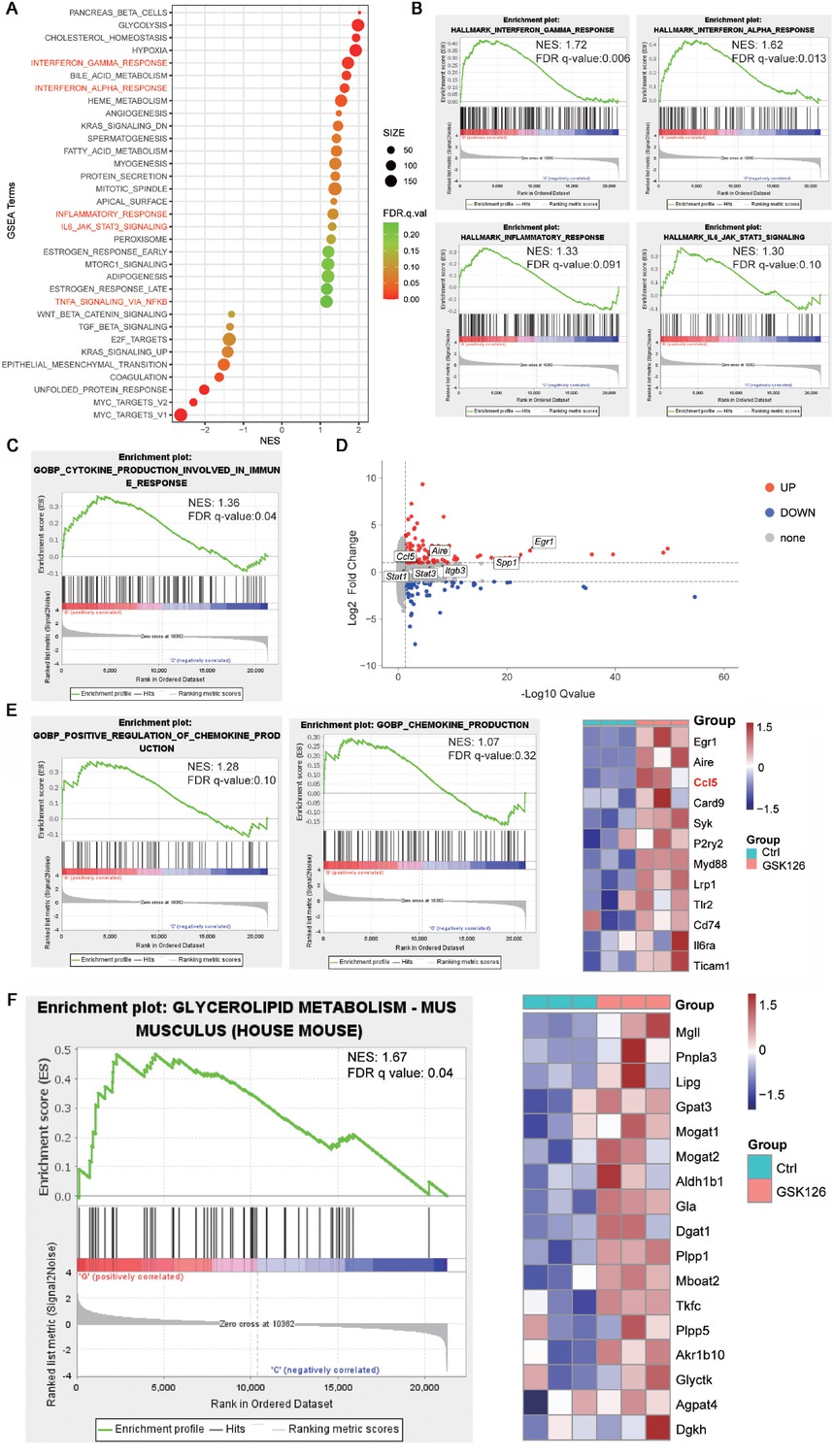

Global toxic effects of GSK126 by RNA-seq profiling

To further dig out the underlying mechanism of the unpleasant anti-tumor effects of the EZH2i, we treated B16F10 cells with GSK126 and proceeded with RNA-seq. GSEA analysis revealed that GSK126 treatment led to the activation of various immune-related pathways, including interferon-gamma response, interferon-alpha response, inflammatory, and IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling pathways (Figure 2A and 2B). Notably, cytokine-related pathways exhibited significant alterations post-GSK126 treatment (Figure 2C), with volcano plots highlighting substantial changes in multiple inflammatory factors and their associated transcription factors (Figure 2D). The activation or permission of these immune pathways and cytokines may increase the inflammatory level and exacerbate tissue damage, contributing to the adverse effects of GSK126. Furthermore, we also observed that GSK126 treatment upregulated chemokine-related pathways and increase the expression of immune chemokines such as CCL5 (Figure 2E). The upregulation of CCL5 can enhance the chemotactic effect on immune cells,[28] thereby may contributing to the observed adverse abdominal inflammatory effects associated with GSK126. Additionally, GSEA enrichment analysis also demonstrated that genes associated with the triglyceride metabolism pathway showed significant upregulation in the GSK126-treated group, including Pnpla3, Lipg, and Gpat3 (Figure 2F). This is consistent with our observation of hepatic lipid accumulation in vivo. These observations suggest a potential exacerbation of the local inflammatory response and dysregulated lipid metabolism within the peritoneal cavity triggered by GSK126.

(A) Enrichment plots generated by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) for gene ontology chemokine production genes (left) and hit genes expression in heat map (right), n = 3. (B) Enrichment plots generated by GSEA for gene ontology cytokine production. (C) Enrichment plots generated by GSEA for signaling pathways probably related to cytokine production. (D) Volcano plot of differential expressed genes between GSK126-treated cells and vehicle (UP, red color indicating log2 Fold Change > 1.0 and adjust P value < 0.05; DOWN, blue color indicating Log2 Fold Change < -1.0 and adjust P value < 0.05; other genes are colored in grey. (E) Enrichment plots generated by GSEA for signaling pathways probably related to chemokine production. (F) Enrichment plots generated by GSEA for glycerolipid metabolism.

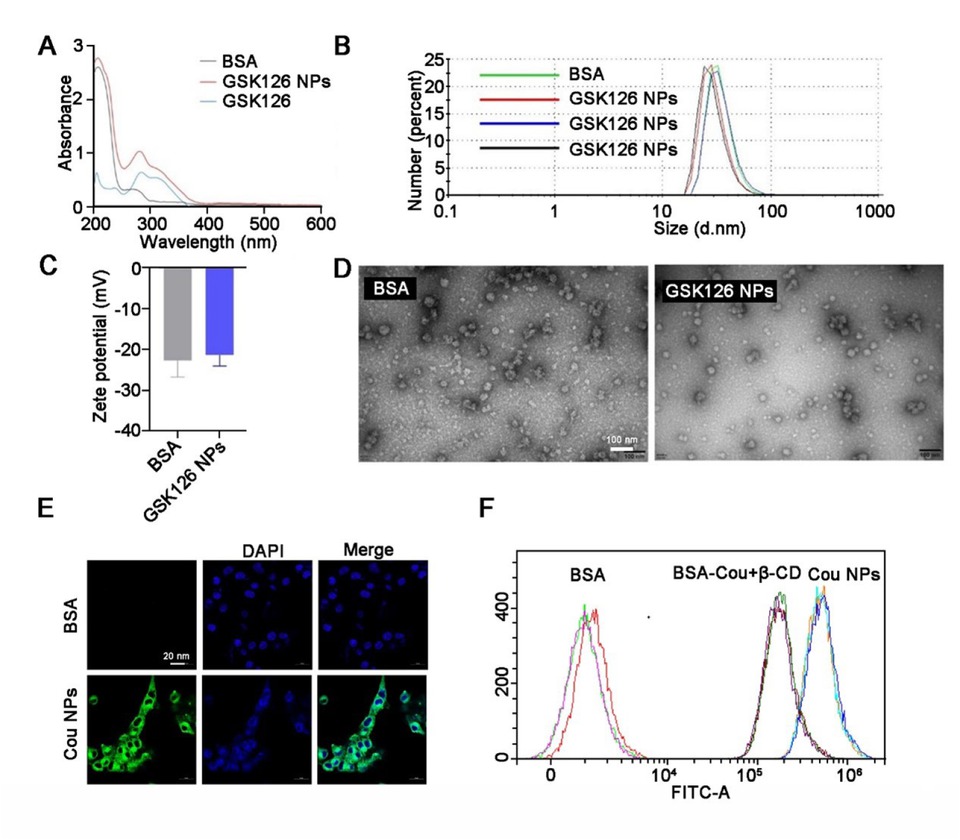

Preparation and characterization of GSK126-loaded albumin nanoparticles

In light of the limited efficacy and severe adverse effects associated with EZH2i in solid tumors, we are exploring the potential of utilizing an albumin-nanoparticle delivery system to facilitate the targeted transportation of EZH2i. Albumin-GSK126 NPs were prepared using the modified desolvation method, which generated ultrafine NPs at a rapid rate according to the optimum conditions. The successful encapsulation of GSK126 into albumin NPs was confirmed through UV analysis, revealing characteristic peaks at 285 and 310 nm (Figure 3A). Notably, the prepared GSK126 NPs exhibited a small spherical core with an average diameter of 30.09 ± 1.55 nm and a narrow size distribution, and demonstrate high drug loading capacity (16.59% ± 2.86%) and good entrapment efficiency (99.53% ± 0.208%) (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the GSK126 NPs displayed a zeta potential of –28 mV, indicating their stability in a physiological environment (Figure 3C). The surface morphologies of GSK126 NPs were examined through SEM. As depicted in Figure 3D, the SEM images showed the synthesized GSK126 NPs have a spherical appearance. To assess the cellular transport capability of GSK126 NPs, a lipophilic fluorescent dye, coumarin-6 (Cou), was incorporated as an indicator of cellular uptake efficiency. The cellular uptake of coumarin-6 NPs by B16F10 cells significantly increased with 6 h incubations (Figure 3E). Flow cytometry confirmed that coumarin-6 NPs efficiently penetrated the cell membrane, while the cellular uptake was inhibited by methyl β-cyclodextrin (β-CD), a known inhibitor of the Gp60/caveolar transport (Figure 3F). These findings verified that the optimized nanoplatforms demonstrated excellent behaviors in vitro, promoting us to further explore their therapeutic potential in vivo.

Morphological and physical characterizations of GSK126 NPs. (A) UV spectrum of BSA, GSK126, and GSK126 NPs. (B-C) The size and surface charge of GSK126 NPs were determined by dynamic light scattering using Zetasizer Nano ZS. (D) Surface morphology of GSK126 NPs was determined by TEM. (E) The intracellular localization of Cou NPs was examined by confocal microscope, and Cou was used as a model fluorescent dye. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of the cellular uptake of Cou NPs.

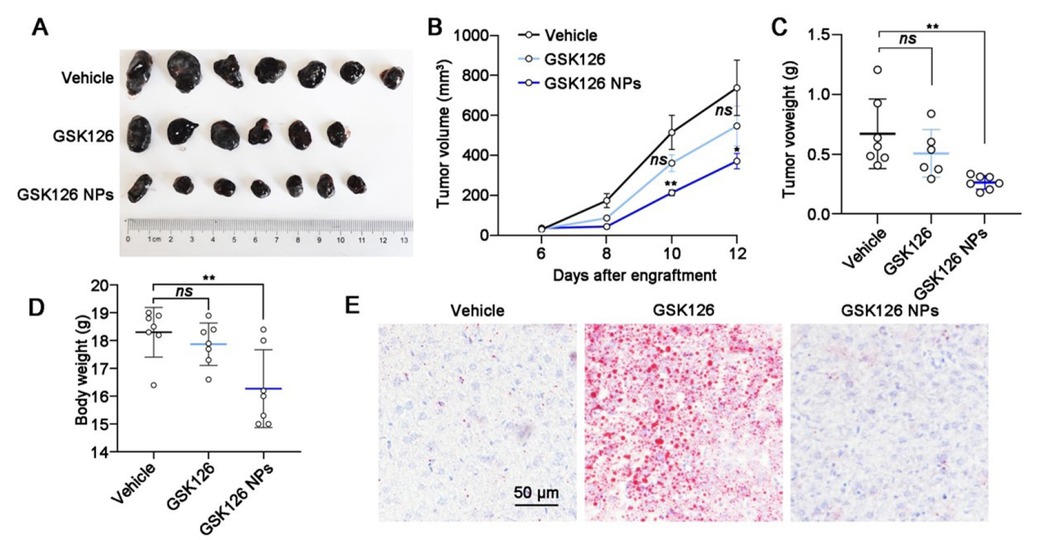

Nano-assembled delivery system presents effective tumor suppression

The in vivo anti-tumor efficacy of GSK126 NPs, vehicle, and free GSK126 were validated in B16F10 bearing C57BL/6 mice. Both free GSK126 and GSK126 NPs were administered via intraperitoneal injection at a dosage of 50 mg/kg/d. As depicted in (Figure 4A-4B), the tumors in the vehicle treated group grew very rapidly to approximately 700 mm3 at day 12 post-treatment. While free GSK126 did not exhibit a significant inhibitory effect on tumor growth, its nanoformulations demonstrated notable tumor growth inhibition compared to the vehicle group (Figure 4C). This was evidenced by reduced tumor volume and decreased tumor weight, suggesting that the NPs of GSK126 may have superior effects on improving systemic circulation compared to free GSK126. Surprisingly, although nanocarriers effectively enhance the anti-tumor activity of EZH2i in solid tumors, we also noticed a significant decrease in body weight in tumor-bearing mice (Figure 4D). Oil Red O staining results demonstrated that GSK126 NPs significantly ameliorated the hepatic lipid accumulation caused by free GSK126, effectively reducing the hepatotoxicity of GSK126. (Figure 4E). This highlights the need for further exploration of the intravenous administration route.

Effects of GSK126 NPs on reducing side effects and increasing efficacy. (A) Images, (B) tumor growth curve, (C) tumor weight, (D) body weight and (E) Oil Red O staining of liver sections of mice carrying B16F10 in the control group (n = 7), GSK126 (50 mg/kg) treatment group (n = 7) and GSK126 NPs (50 mg/kg) treatment group (n = 7). Tumor volume was measured with a vernier caliper every 2 days. Tumor volume = Length × Width× Width / 2. Tumor weights were measured at day 12 after engraftment. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison posttest. ns, nonsignificant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

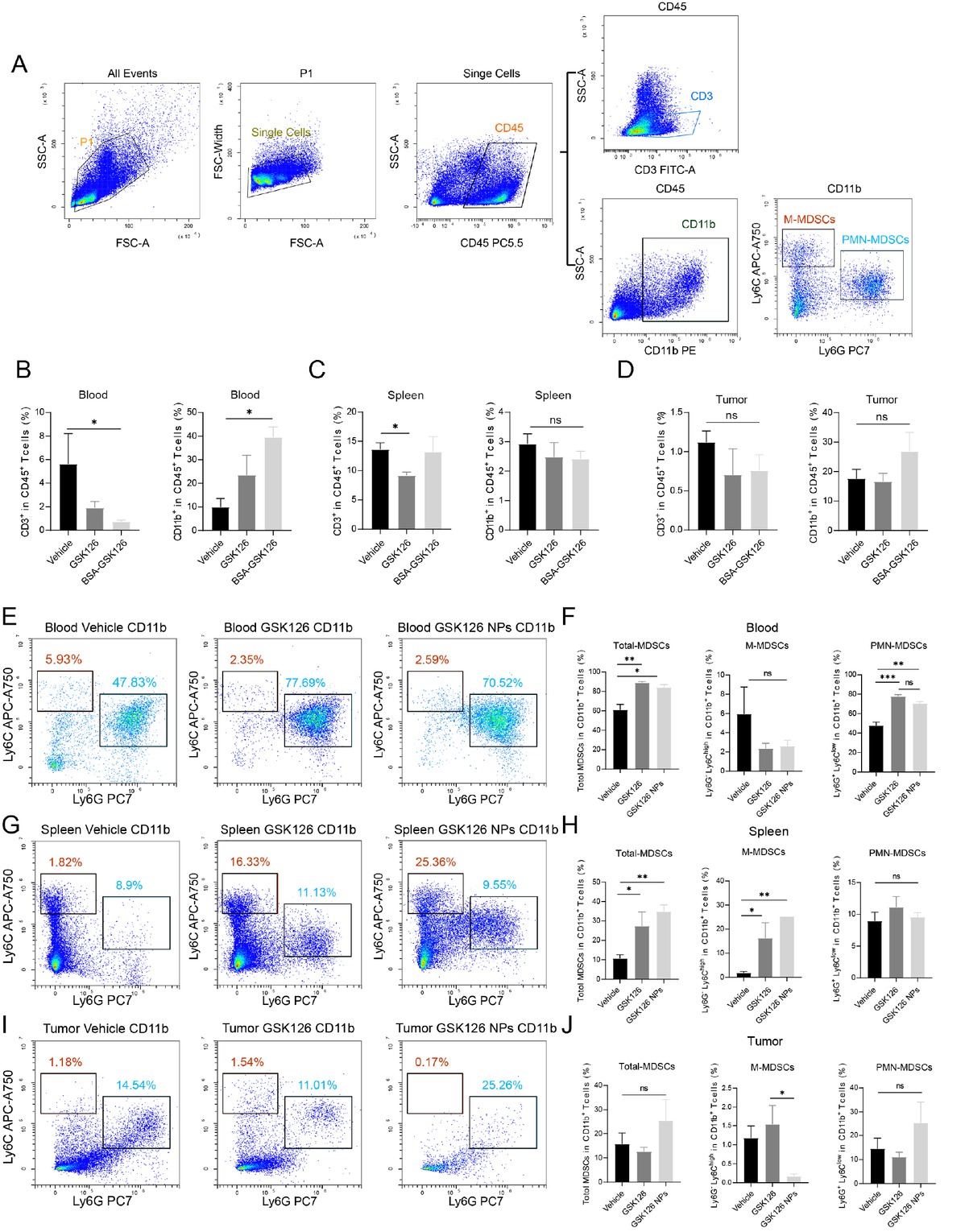

Previous investigations have indicated that GSK126 may promote the generation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) or recruitment within the tumor microenvironment, which could partially account for the compromised effectiveness in combating tumor progression.[29] We then examined immune cells in the peripheral blood, spleen, and tumor microenvironment of B16F10-bearing mice treated with vehicle control, free GSK126, and GSK126 NPs using flow cytometry, with a focus on myeloid subsets (Figure 5A). In peripheral blood, both forms of GSK126 can reduce the proportion of CD3+ T cells while increasing the proportion of CD11b+ myeloid cells, with these effects being more pronounced in the GSK126 NPs treatment group (Figure 5B). Besides, free GSK126 significantly reduced the proportion of CD3+ T cells in the spleen, whereas GSK126 NPs had no significant impact on the CD3+ T cells in the spleen (Figure 5C). Neither form of GSK126 altered the proportion of CD11b+ myeloid cells within the CD45+ white blood cells in the spleen (Figure 5C). Upon analyzing tumor-infiltrating immune cells, we found that both forms of GSK126 had no significant impact on tumor-infiltrating CD3+ T cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells (Figure 5D). Based on these myeloid immune cells’ phenotyping, we further detect MDSC subsets in peripheral blood, spleen, and tumor microenvironment to evaluate whether the GSK126 NPs could reverse this effect to enhance the anti-tumor efficacy. We identified CD11b+Ly6G-Ly6Chi as M-MDSCs, and CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Clow as PMN-MDSCs, and the sum of these two populations as total MDSCs. Both forms of GSK126 could increase the proportion of PMN- and total MDSC cells in peripheral blood, but not M-MDSCs (Figure 5E and 5F). Meanwhile, both free GSK126 and GSK126 NPs increase the proportion of M-and total MDSC cells in spleen, but have limited effect on PMN-MDSCs (Figure 5G and 5H). However, in the tumor microenvironment, GSK126 NPs significantly reduced the proportion of M-MDSCs which is the main subtype functioning the immune suppressive role, whereas free GSK126 did show the increasing tendency in M-MDSC proportion (Figure 5I and 5J).

GSK126 NPs affect the generation and infiltration of MDSCs. (A) Gating strategy for CD3+ and MDSCs in flow cytometry. (B-D) Proportions of CD3+ T lymphocytes and CD11b+ myeloid cells among CD45+ leukocytes in (B) peripheral blood, (C) spleen, and (D) tumor. (E-F) Effects of vehicle control, free GSK126, and GSK126 NPs on M-MDSCs, PMN-MDSCs, and total MDSCs in peripheral blood. (G-H) Effects of vehicle control, free GSK126, and GSK126 NPs on M-MDSCs, PMN-MDSCs, and total MDSCs in spleen. (I-J) Effects of vehicle control, free GSK126, and GSK126 NPs on M-MDSCs, PMN-MDSCs, and total MDSCs in tumor-infiltrating cells. ns: nonsignificant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

These findings suggest that GSK126 NPs and free GSK126 exhibit similar immune regulatory effect in peripheral blood and spleen by tuning either M-MDSC or PMNMDSC percentage. However, upon nanoformulation, it does reduce M-MDSC infiltration in the tumor microenvironment, thereby improving the immune-suppressive microenvironment and enhancing the antitumor capacity.

Discussion

High expression of EZH2 is significantly associated with the pathogenesis and progression of multiple hematological and solid tumors, promoting cell survival, proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion, as well as drug resistance.[30] Therefore, small molecule inhibitor targeting EZH2 represents a hopeful strategy for oncotherapy. Despite the FDA approval of EZH2i in 2020, improving the anti-tumor efficacy of these inhibitors in solid tumors remains a crucial issue that draws attention. Our previous and ongoing in vitro and in vivo experiments confirmed the disparate sensitivity of hematologic and solid tumor cell lines to EZH2 inhibition. Hematologic malignancies demonstrated high sensitivity, whereas solid tumors exhibited limited response to the EZH2i.[18] Previous investigation has suggested encapsulating EZH2i derivatives in polymeric PLGA NPs could potentially enhance the therapeutic efficacy for liver cancer treatment in vitro.[31] Albumin, valued for its exceptional biodegradability, non-toxicity, and capacity to bind to receptors, is extensively studied as a versatile nanodrug delivery system.[32] Additionally, albumin naturally accumulates in tumor tissues due to the EPR effect, resulting in more efficient and targeted drug delivery. Albumin-based systems offer improved biocompatibility, reduced immunogenicity, and enhanced drug stability. While other drug delivery methods, such as siRNA delivery, are also gaining attention for their potential in gene silencing. However, those methods are facing several significant challenges. These challenges include membrane impermeability that obstructs siRNA entry into cells and enzymatic degradation, which leads to rapid breakdown of siRNA before it reaches its target. Furthermore, siRNA nanoparticles often undergo fast renal excretion, reducing their effectiveness; encounter difficulties in escaping endosomes within cells; and experience off-target effects. In contrast, albumin-based systems offer a more reliable and effective method for delivering therapeutic agents directly to the tumor site, potentially enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing these challenges and reducing systemic side effects.[33] Therefore, we explored the application of albumin-based GSK126 NPs in this study. The results demonstrated that GSK126 NPs exhibited favorable characteristics in terms of size, zeta (ζ) potential, and efficient cellular uptake. Importantly, treatment with GSK126 NPs resulted in significant tumor growth inhibition in vivo, suggesting a promising strategy for enhancing the anti-cancer efficacy of EZH2i in solid tumors.

Our results also revealed notable adverse effects associated with GSK126 treatment, including dysregulated lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses (Figure 1 and 2). Lipid metabolism reprogramming, a hallmark of cancer, plays a crucial role in tumor cell proliferation, movement, and drug resistance.[34,35] Previous investigations by us has substantiated that the EZH2i can alter lipid metabolism by upregulating key genes implicated in lipid and cholesterol synthesis, such as ACLY, FASN, and SCD.[18] Current study reaffirms that the administration of GSK126 on its own leads to heightened lipid accumulation in the liver tissue of tumor-bearing mice. The underlying mechanism accounting for this side effect was investigated by RNA-seq. The enrichment analysis demonstrated that the genes involved in triglyceride synthesis were pronounced at the molecular level. However, incorporating EZH2i into NPs can notably mitigate lipid-related toxicity in the liver. This benefit is likely due to the enhanced targeting of tumor tissues by GSK126 when delivered via nanoparticles, which lowers the concentration of free drug in the bloodstream and thus reduces liver toxicity. Studies have shown that nanoparticle drug delivery systems prevent direct contact between the drug and normal cells and exhibit controlled release, providing sustained delivery and avoiding peak plasma concentrations, thereby reducing toxicity.[36,37] Moreover, as previously mentioned, enhanced targeting ensures more effective delivery of the drug to tumor sites, minimizing its distribution in normal tissues or organs and reducing systemic toxicity. These attributes may contribute to the lower lipotoxicity observed with GSK126 NPs.

The observed inflammatory reactions associated with GSK126 treatment raise important considerations for its clinical application. Despite the significant reduction in tumor growth observed with GSK126 NPs, our findings indicate that both free GSK126 and GSK126 NPs induced abdominal inflammation and ascites, suggesting that GSK126 NPs did not effectively mitigate local adverse reactions in the peritoneal cavity. This underscores the need for further exploration of alternative administration routes, such as intravenous delivery. While the enhanced anti-tumor effects are demonstrated (Figure S1), further investigation is required to determine if this can also reduce local adverse effects. Nevertheless, this study introduces a pioneering research approach aimed at maximizing the effectiveness and minimizing the adverse effects of EZH2i in solid tumor treatment.

GSK126 can upregulate MDSCs in mouse tumor models, thereby limiting its efficacy in vivo.[29] MDSCs are a group of cells defined by their immunosuppressive function. Based on the differential expression levels of two epitopes, Ly6G and Ly6C, MDSCs are identified as two distinct subsets: polymorphonuclear (PMN-) and monocytic (M-) MDSCs.[38] Compared to M-MDSCs, PMN-MDSCs constitute a higher proportion of MDSCs and exhibit preferential expansion within tumors.[39,40] Despite constituting their smaller proportion, M-MDSCs exhibit a stronger immunosuppressive capacity.[39, 40, 41, 42] Our study revealed that PMN-MDSCs dominate in multiple sites, including peripheral blood, spleen, and tumor. However, the response of MDSC subsets to GSK126 varies by location. In peripheral blood, GSK126 mainly induces an upregulation of PMN-MDSCs, while in the spleen, M-MDSCs are predominantly affected. GSK126 NPs did not improve the upregulation of MDSCs caused by GSK126 in peripheral blood and spleen. However, in tumors, GSK126 NPs significantly reduced the infiltration of M-MDSCs, which was not observed with free GSK126. One current mechanism is that GSK126 can upregulate IL-6 expression directly or through NF-κB pathway, thereby influencing the differentiation of MDSCs.[43,44] Additionally, GSK126 may upregulate Cebpe, a transcription factor from the C/EBP family, which is involved in the regulation of myeloid progenitor cell differentiation.[29,45] However, the specific mechanism by which GSK126 NPs reduce tumor-infiltrating M-MDSCs is not yet fully clear, even this reduction can weaken the immunosuppressive effects of MDSCs and diminish immune evasion, ultimately achieving better anti-tumor efficacy. This phenomenon highlights the potential of nanoparticle delivery systems to modulate the immune landscape within tumors. Future studies should focus on elucidating the pathways involved in this selective reduction of MDSCs by GSK126 NPs. Potential mechanisms could involve altered drug release profiles, enhanced targeting of tumor microenvironments, or modulation of the local immune milieu by the nanoparticle formulation itself.[46] Additionally, there is a connection between metabolism, immune response, and inflammation.[47,48] Our experiments observed that GSK126 NPs-induced changes in lipid metabolism, inflammation, and tumor immune infiltrating cells may be interconnected, warranting further investigation.

Further clinical advancement of EZH2i is still highly needed to be explored,[11] GSK126, developed earlier than Tazemetostat and had been attempted in clinical trials, did not demonstrate sufficiently clear clinical benefits at the tested doses in early trials for DLBCL.[49] Additionally, its adverse effects limited dose escalation, which has also restricted the broader application of EZH2 inhibitors in other tumor types. Besides, the global effects of EZH2 on the immune system also present factors that limit its therapeutic efficacy. For example, GSK126 can promote the recruitment of MDSCs[29] or increase the infiltration of M2 macrophages in colorectal cancer.[50] Therefore, the findings of this study, which demonstrate that the construction of NPs can partially alleviate the hepatotoxicity and the side effect of inducing MDSCs recruitment associated with GSK126, may offer a potential solution to overcome the clinical application challenges of GSK126 and other EZH2 inhibitors. Furthermore, new therapeutic strategies, such as novel small molecule configurations,[51] combination therapies with EZH2 inhibitors,[7] drug development targeting other components of the PRC2 complex,[52] or new therapeutic approaches like PROTACs,[10,53] hold promise for providing more viable treatment options centered around EZH2. These approaches also offer increased potential for the clinical integration of EZH2i NPs.

Despite the encouraging results, several challenges and questions remain to be addressed. While our study focused on the therapeutic potential of GSK126 NPs in solid tumor therapy, future research should explore additional aspects such as the long-term effects of GSK126 NPs on tumor growth and recurrence, exploring the combinatorial potential with other therapeutic agents, and understanding the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of GSK126 NPs to optimize their delivery and therapeutic window. This comprehensive research aims to refine treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes in cancer therapy.

In short, we successfully fabricated GSK126 NPs using modified desolvation method for active tumor targeting. This nanosystem displayed multiple characteristics such as enhanced drug loading, greater cellular uptake, prolonged blood retention time, as well as considerable tumor accumulation. GSK126 NPs proved to be effective in solid tumor. The enhanced anti-tumor efficacy of GSK126 NPs might be attributed to its precise binding to albumin receptors such as SPARC. Although this is being investigated by our team, the present work is a good step toward expanding the scope of EZH2 inhibitor application clinically. This study confirmed that GSK126 NPs are promising NPs for solid tumor therapy.

Supplementary Information

Figure S1. Effects of GSK126 NPs on increasing antitumor efficacy. Supplementary materials are only available at the official site of the journal (www.intern-med.com).

Funding statement: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1104001), the General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82272745, No. 81972966), Youth Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82203102, No. 82204678). Key Projects of Peking University Third Hospital Clinical (No. BYSYZD2023010, No. BYSYZD2023031).

Acknowledgements

The graphical abstract of this article was created with BioRender.com.

-

Author Contributions

Guo Y, Huang J, Lin M, and Zhang T supervised the study and contributed to manuscript writing. Yin Q performed the bioinformatic analysis. Guo Z, Tang Y, Cheng R, Wang Y, Peng Y, and Cao X were responsible for data collection and organization. Qi X, Liu Y, and Xue L designed the study, reviewed, edited, and proofed the figures and manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. Guo Y, Huang J and Lin M made equal contributions to this work.

-

Ethical Approval

Mice used in this study was maintained in a controlled environment approved by the Ethical Guidelines of EIACUC-PKU (A2021230).

-

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

-

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author (s).

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools

None declared.

-

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq data are accessible at NCBI GEO: GSE163078 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

1 Margueron R, Reinberg D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature 2011;469:343-349.10.1038/nature09784Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2 Laugesen A, Højfeldt JW, Helin K. Molecular mechanisms directing PRC2 recruitment and H3K27 methylation. Mol Cell 2019;74:8-18.10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3 Blackledge NP, Klose RJ. The molecular principles of gene regulation by polycomb repressive complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021;22: 815-833.10.1038/s41580-021-00398-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4 Zhang T, Gong Y, Meng H, Li C, Xue L. Symphony of epigenetic and metabolic regulation-interaction between the histone methyltransferase EZH2 and metabolism of tumor. Clin Epigenetics 2020;12:72.10.1186/s13148-020-00862-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5 Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, Guenther MG, Levine SS, Kumar RM, et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 2006;125:301-313.10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.043Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6 Chang CJ, Yang JY, Xia W, Chen CT, Xie X, Chao CH, et al. EZH2 promotes expansion of breast tumor initiating cells through activation of RAF1-β-catenin signaling. Cancer Cell 2011;19:86-100.10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.035Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7 Guo Y, Cheng R, Wang Y, Gonzalez ME, Zhang H, Liu Y, et al. Regulation of EZH2 protein stability: new mechanisms, roles in tumorigenesis, and roads to the clinic. EBioMedicine 2024;100:104972.10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.104972Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8 Stitzlein LM, Adams JT, Stitzlein EN, Dudley RW, Chandra J. Current and future therapeutic strategies for high-grade gliomas leveraging the interplay between epigenetic regulators and kinase signaling networks. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2024;43:12.10.1186/s13046-023-02923-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9 Du D, Xu D, Zhu L, Stazi G, Zwergel C, Liu Y, et al. Structure-guided development of small-molecule PRC2 inhibitors targeting EZH2-EED interaction. J Med Chem 2021;64:8194-8207.10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c02261Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10 Wang C, Chen X, Liu X, Lu D, Li S, Qu L, et al. Discovery of precision targeting EZH2 degraders for triple-negative breast cancer. Eur J Med Chem 2022;238:114462.10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114462Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11 Zeng J, Zhang J, Sun Y, Wang J, Ren C, Banerjee S, et al. Targeting EZH2 for cancer therapy: From current progress to novel strategies. Eur J Med Chem 2022;238:114419.10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114419Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12 Bhat KP, Ümit Kaniskan H, Jin J, Gozani O. Epigenetics and beyond:targeting writers of protein lysine methylation to treat disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021;20:265-286.10.1038/s41573-020-00108-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13 Hoy SM. Tazemetostat: First approval. Drugs 2020;80:513-521.10.1007/s40265-020-01288-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

14 Dockerill M, Gregson C, O’ Donovan DH. Targeting PRC2 for the treatment of cancer: an updated patent review (2016 - 2020). Expert Opin Ther Pat 2021;31:119-135.10.1080/13543776.2021.1841167Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15 Yamagishi M, Kuze Y, Kobayashi S, Nakashima M, Morishima S, Kawamata T, et al. Mechanisms of action and resistance in histone methylation-targeted therapy. Nature 2024;627:221-228.10.1038/s41586-024-07103-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16 Huang X, Yan J, Zhang M, Wang Y, Chen Y, Fu X, et al. Targeting epigenetic crosstalk as a therapeutic strategy for EZH2-aberrant solid tumors. Cell 2018;175:186-199.e19.10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.058Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17 Park SH, Fong KW, Mong E, Martin MC, Schiltz GE, Yu J. Going beyond polycomb: EZH2 functions in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2021;40:5788-5798.10.1038/s41388-021-01982-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18 Zhang T, Guo Z, Huo X, Gong Y, Li C, Huang J, et al. Dysregulated lipid metabolism blunts the sensitivity of cancer cells to EZH2 inhibitor. EBioMedicine 2022;77:103872.10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103872Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19 Huang Z, Tang Y, Zhang J, Huang J, Cheng R, Guo Y, et al. Hypoxia makes EZH2 inhibitor not easy-advances of crosstalk between HIF and EZH2. Life Metab 2024;3.10.1093/lifemeta/loae017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20 Zhou Q, Liu Q, Wang Y, Chen J, Schmid O, Rehberg M, et al. Bridging smart nanosystems with clinically relevant models and advanced imaging for precision drug delivery. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024;11:e2308659.10.1002/advs.202308659Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21 Shen X, Pan D, Gong Q, Gu Z, Luo K. Enhancing drug penetration in solid tumors via nanomedicine: Evaluation models, strategies and perspectives. Bioact Mater 2024;32:445-472.10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.10.017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22 Tao Y, Jakobsson V, Chen X, Zhang J. Exploiting albumin as a versatile carrier for cancer theranostics. Acc Chem Res 2023;56:2403-2415.10.1021/acs.accounts.3c00309Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23 Aguilera-Garrido A, Del Castillo-Santaella T, Yang Y, Galisteo-González F, Gálvez-Ruiz MJ, Molina-Bolívar JA, et al. Applications of serum albumins in delivery systems: Differences in interfacial behaviour and interacting abilities with polysaccharides. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2021;290:102365.10.1016/j.cis.2021.102365Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24 Ji Q, Zhu H, Qin Y, Zhang R, Wang L, Zhang E, et al. GP60 and SPARC as albumin receptors: key targeted sites for the delivery of antitumor drugs. Front Pharmacol 2024;15:1329636.10.3389/fphar.2024.1329636Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25 Ghosh S, Javia A, Shetty S, Bardoliwala D, Maiti K, Banerjee S, et al. Triple negative breast cancer and non-small cell lung cancer: Clinical challenges and nano-formulation approaches. J Control Release 2021;337:27-58.10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.07.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26 Elzoghby AO, Samy WM, Elgindy NA. Albumin-based nanoparticles as potential controlled release drug delivery systems. J Control Release 2012;157:168-182.10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.07.031Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27 Iqbal H, Razzaq A, Khan NU, Rehman SU, Webster TJ, Xiao R, et al. pH-responsive albumin-coated biopolymeric nanoparticles with lapatinab for targeted breast cancer therapy. Biomater Adv 2022;139:213039.10.1016/j.bioadv.2022.213039Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28 Zeng Z, Lan T, Wei Y, Wei X. CCL5/CCR5 axis in human diseases and related treatments. Genes Dis 2022;9:12-27.10.1016/j.gendis.2021.08.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29 Huang S, Wang Z, Zhou J, Huang J, Zhou L, Luo J, et al. EZH2 Inhibitor GSK126 suppresses antitumor immunity by driving production of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res 2019;79:2009-2020.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2395Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30 Kaur P, Shankar E, Gupta S. EZH2-mediated development of therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Lett 2024;586:216706.10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216706Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31 Elkot HA, Ragab I, Saleh NM, Amin MN, Al-Rashood ST, El-Messery SM, et al. Design, synthesis, and antitumor activity of PLGA nanoparticles incorporating a discovered benzimidazole derivative as EZH2 inhibitor. Chem Biol Interact 2021;344:109530.10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109530Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32 Spada A, Emami J, Tuszynski JA, Lavasanifar A. The Uniqueness of Albumin as a Carrier in Nanodrug Delivery. Mol Pharm 2021;18:1862-1894.10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.1c00046Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33 Moazzam M, Zhang M, Hussain A, Yu X, Huang J, Huang Y. The landscape of nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery and therapeutic development. Mol Ther 2024;32:284-312.10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.01.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34 Yang K, Wang X, Song C, He Z, Wang R, Xu Y, et al. The role of lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor microenvironment. Theranostics 2023;13:1774-180.10.7150/thno.82920Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35 Ke X, Zou M, Xu C. Lipid metabolism in tumor-infiltrating T cells: mechanisms and applications. Life Metabolism 2022;1:211-223.10.1093/lifemeta/loac038Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36 Desale JP, Swami R, Kushwah V, Katiyar SS, Jain S. Chemosensitizer and docetaxel-loaded albumin nanoparticle: overcoming drug resistance and improving therapeutic efficacy. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2018;13:2759-2776.10.2217/nnm-2018-0206Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37 Ruan C, Liu L, Lu Y, Zhang Y, He X, Chen X, et al. Substance P-modified human serum albumin nanoparticles loaded with paclitaxel for targeted therapy of glioma. Acta Pharm Sin B 2018;8:85-96.10.1016/j.apsb.2017.09.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38 Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat Commun 2016;7:12150.10.1038/ncomms12150Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39 Condamine T, Mastio J, Gabrilovich DI. Transcriptional regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Leukoc Biol 2015;98:913-922.10.1189/jlb.4RI0515-204RSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40 Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol 2008;181:5791-5802.10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41 Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y, Burnette B, Wang Y, Meng Y, et al. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood 2009;114:589-595.10.1182/blood-2009-02-206870Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42 Wu Y, Yi M, Niu M, Mei Q, Wu K. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: an emerging target for anticancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer 2022;21:184.10.1186/s12943-022-01657-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43 Wang L, Zhu L, Liang C, Huang X, Liu Z, Huo J, et al. Targeting N6-methyladenosine reader YTHDF1 with siRNA boosts antitumor immunity in NASH-HCC by inhibiting EZH2-IL-6 axis. J Hepatol 2023;79:1185-1200.10.1016/j.jhep.2023.06.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

44 Zhou J, Liu M, Sun H, Feng Y, Xu L, Chan AWH, et al. Hepatoma-intrinsic CCRK inhibition diminishes myeloid-derived suppressor cell immunosuppression and enhances immune-checkpoint blockade efficacy. Gut 2018;67:931-944.10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314032Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45 Gery S, Gombart AF, Fung YK, Koeffler HP. C/EBPepsilon interacts with retinoblastoma and E2F1 during granulopoiesis. Blood 2004;103:828-835.10.1182/blood-2003-01-0159Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

46 Xu C, Amna N, Shi Y, Sun R, Weng C, Chen J, et al. Drug-Loaded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Enhance Antitumor Immunotherapy by Regulating MDSCs. Molecules 2024;29:2436.10.3390/molecules29112436Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47 Bevilacqua A, Ho P, Franco F. Metabolic reprogramming in inflammaging and aging in T cells. Life Metabolism 2023;2:1-8.10.1093/lifemeta/load028Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48 Andersen CJ. Lipid Metabolism in Inflammation and Immune Function. Nutrients 2022;14:1414.10.3390/nu14071414Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49 Yap TA, Winter JN, Leonard JP, Ribrag V, Constantinidou A, Giulino-roth L, et al. A phase I study of GSK2816126, an enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2(EZH2) inhibitor, in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), other non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL), transformed follicular lymphoma (tFL), solid tumors and multiple myeloma (MM). Blood 2016;128:4203-420310.1182/blood.V128.22.4203.4203Suche in Google Scholar

50 Li C, Song J, Guo Z, Gong Y, Zhang T, Huang J, et al. EZH2 Inhibitors suppress colorectal cancer by regulating macrophage polarization in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol 2022;13: 857808.10.3389/fimmu.2022.857808Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51 Le M, Lu W, Tan X, Luo B, Yu T, Sun Y, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of potent EZH2/LSD1 Dual Inhibitors for Prostate Cancer. J Med Chem 2024;67:15586-15605.10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01250Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

52 Rej RK, Wang C, Lu J, Wang M, Petrunak E, Zawacki KP, et al. EEDi5285: An exceptionally potent, efficacious, and orally active small-molecule inhibitor of embryonic ectoderm development. J Med Chem 2020;63:7252-7267.10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00479Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53 Corbin J, Yu X, Jin J, Cai L, Wang GG. EZH2 PROTACs target EZH2-and FOXM1-associated oncogenic nodes, suppressing breast cancer cell growth. Oncogene 2024;43:2722-2736.10.1038/s41388-024-03119-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 Yunyun Guo, Jiaqi Huang, Meng Lin, Qianqian Yin, Tengrui Zhang, Zhengyang Guo, Yuanjun Tang, Rui Cheng, Yan Wang, Yiwei Peng, Xuedi Cao, Yuqing Wang, Xianrong Qi, Yang Liu, Lixiang Xue, published by De Gruyter on behalf of the SMP

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Perspective

- Crosstalk between cardiac dysfunction and outcome of liver cirrhosis: Perspectives from evidence-based medicine and holistic integrative medicine

- Telemedicine strategies in older patients with cardiovascular diseases

- Clinical significance of portal vein thrombosis in patients with decompensated cirrhosis: A still matter of debate

- Review Article

- Eupatilin unveiled: An in-depth exploration of research advancements and clinical therapeutic prospects

- Original Article

- Benzo[b]fluoranthene is involved in idiopathic membranous nephropathy by inducing podocyte injury

- A novel and safe protocol for patients with severe comorbidity who undergo haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A single-center prospective study

- Deciphering the role of ELAVL1: Insights from pan-cancer multiomics analyses with emphasis on nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Nano particle loaded EZH2 inhibitors: Increased efficiency and reduced toxicity for malignant solid tumors

- An automated human–machine interaction system enhances standardization, accuracy and efficiency in cardiovascular autonomic evaluation: A multicenter, open-label, paired design study

- Rapid Communication

- Comparison of predicting value of triglyceride‑glucose indices family in cardiovascular disease risk over time: Insights from a 9-year nationwide prospective cohort study

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Perspective

- Crosstalk between cardiac dysfunction and outcome of liver cirrhosis: Perspectives from evidence-based medicine and holistic integrative medicine

- Telemedicine strategies in older patients with cardiovascular diseases

- Clinical significance of portal vein thrombosis in patients with decompensated cirrhosis: A still matter of debate

- Review Article

- Eupatilin unveiled: An in-depth exploration of research advancements and clinical therapeutic prospects

- Original Article

- Benzo[b]fluoranthene is involved in idiopathic membranous nephropathy by inducing podocyte injury

- A novel and safe protocol for patients with severe comorbidity who undergo haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A single-center prospective study

- Deciphering the role of ELAVL1: Insights from pan-cancer multiomics analyses with emphasis on nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Nano particle loaded EZH2 inhibitors: Increased efficiency and reduced toxicity for malignant solid tumors

- An automated human–machine interaction system enhances standardization, accuracy and efficiency in cardiovascular autonomic evaluation: A multicenter, open-label, paired design study

- Rapid Communication

- Comparison of predicting value of triglyceride‑glucose indices family in cardiovascular disease risk over time: Insights from a 9-year nationwide prospective cohort study