Abstract

This study investigates the influence of social media on female representation and body image perceptions among young female students in Southwest Nigeria, examining the interplay between global media dynamics and local cultural contexts. Through a de-westernizing lens, the research explores the prevalence of social media usage, perceptions of female representation, and the impact on body image. Findings reveal a pervasive engagement with social media among Nigerian females, while resisting Western beauty ideals and demonstrating satisfaction with body size and skin tone. Drawing from cultural imperialism theory and social comparison theory, the study exposes the complex relationship between social media, cultural influences, and individual agency in shaping female identity. Data was collected through a questionnaire administered to a sample of 400 female students from two universities in Southwest Nigeria: The University of Ibadan and Lead City University. A multi-stage sampling technique was employed, starting with the purposive selection of 24,000 female students. Yamane’s sample size formula was then applied to determine a reliable and representative sample size of 400 participants. The analysis utilized various statistical tools, including descriptive statistics such as frequencies, percentages, and mean distributions, along with inferential statistics like Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), logistic regression, and linear regression models. The data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software. However, despite the existence of online social comparisons among young Nigerian female students, the desire to conform to the idealized body image portrayed by social media or adopt the slim body type of a traditional Western woman is not prevalent among most of the respondents. This finding suggests that young Nigerian female students exhibit a strong sense of body confidence contributing to improved mental wellbeing and fostering a more diverse societal perception of beauty.

1 Introduction

In recent years, social media platforms have emerged as powerful channels for disseminating ideas, attitudes, and values, shaping the perceptions and behaviors of individuals across various demographics. Notably, statistics from the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics (NBS, 2022Q1) reveal a predominant engagement with social media among young Nigerian females, highlighting the significant influence these platforms have, particularly among Nigerian female students. According to Kemp (2023), Nigeria boasts a burgeoning social media user base, with approximately 31.60 million active users, of which nearly 45 % are females aged between 20 and 34. This trend underscores the influential role of social media in shaping the experiences and perceptions of young Nigerian females, particularly concerning body image and appearance (Molina-Ruiz, Alfonso-Fuertes, and González Vives 2022). However, while the impact of social media on body image, appearance, and societal perceptions has been widely documented, there exists a critical need to contextualize these effects within a framework that transcends Western-centric perspectives. Monks et al. (2020) have extensively explored the multifaceted influence of social media on diverse study demographics, including body image, health, and wellness. Similarly, Henriques and Patnaik (2020) have underscored the role of social media in establishing beauty standards, particularly for females and other gender identities, with implications for self-esteem and societal perceptions. Yet, prevailing discourse often overlooks the nuanced interplay between global media dynamics and local cultural contexts, particularly in regions such as Nigeria.

In Nigeria, as in many other societies, females contend with pervasive body image concerns, with societal ideals often privileging thinness as the epitome of beauty (Steinsbekk et al. 2021). The proliferation of online content across social media platforms further exacerbates these pressures, perpetuating idealized notions of gender, sexuality, attractiveness, and body shape. Such content not only reinforces existing appearance cultures but also reflects and amplifies Western beauty standards, which may not necessarily resonate with the diverse realities of Nigerian young females. This study seeks to address this gap by examining female representation on social media platforms in Nigeria from a perspective that counters Western-centric views. By interrogating the influence of Western ideals of body image on Nigerian young females, the research aims to unravel the complex interplay between global media influences and local cultural norms. Through an exploration of the portrayals and perceptions of female bodies on social media, this study endeavors to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of gender representation in the Nigerian context. By foregrounding the agency of Nigerian young females in negotiating and contesting Western beauty standards, ultimately, by adopting a de-westernizing perspective, this research aims to pave the way for more inclusive and culturally sensitive approaches to studying and addressing the impact of social media on female body image and identity in Nigeria.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Historical Perspective of Western Beauty Ideals in Nigeria

During the colonial period, spanning the late 19th century until Nigeria gained independence in 1960, British colonial authorities exerted significant control over media outlets in the region. Colonial administrators utilized media channels to disseminate propaganda and reinforce colonial ideologies, including gender stereotypes and hierarchical social structures that privileged Western values and norms. According to Maikaba and Msughter (2019) following independence, Nigeria experienced a proliferation of indigenous media outlets seeking to assert national identity and challenge colonial narratives. However, Western media continued to exert influence over the Nigerian media landscape through channels such as television, film, and magazines, which often imported Western cultural values and beauty standards. The influence of Western media on body image, and beauty standards of women in Nigeria became increasingly pronounced with the advent of globalization and the expansion of digital media platforms (Ajaegbu et al. 2021). Western beauty ideals, which prioritize thinness, fair skin, and Eurocentric features, became normalized through Western-dominated media platforms, contributing to the marginalization of indigenous beauty standards and the erasure of diverse representations of Nigerian women (Miller 2023).

While early research predominantly focused on Western-centric perspectives, recent scholarship has increasingly emphasized the importance of de-westernizing analyses to contextualize these effects within local cultural frameworks. Critics argue that the pervasive influence of social media may exacerbate body dissatisfaction among young females, as virtual interactions and content consumption fuel aspirations to conform to idealized beauty standards (Valkenburg and Piotrowski 2017). While Nigerian perceptions of body image traditionally diverge from Western ideals, the accessibility of Western-centric content on social media platforms facilitates the adoption and internalization of these standards among Nigerian females (Warren and Akoury 2020). This phenomenon is compounded by the influence of Nigerian social media influencers who emulate Western lifestyle and beauty norms, further perpetuating the hegemony of Western beauty standards (Kumar 2023).

2.2 Social Media Usage Trends Among Female Students in South West Nigeria Universities

Understanding social media usage trends among female students in South West Nigeria universities sheds light on how these platforms influence perceptions of femininity, both globally and within Nigeria. Cultural and social factors uniquely shape online behaviors in this context. Recent statistics from the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics (NBS, 2022Q1) highlight a significant rise in internet access in Nigeria, with a notable portion engaging with social media platforms. Among users, young females stand out, forming a considerable presence on various platforms. Social media is currently recognized as the most commonly used, particularly for young females in Western societies (Bair et al. 2012). As of January 2022, around 13 % of active female social media users in Nigeria were aged between 25 and 34 years (Sasu 2023). According to Brown and Bobkowski (2011), social media is vividly changing the lives and experiences of young female adults, as the new media may pose a threat to body image and beauty satisfaction if increased virtual interaction results in increased imitation. Cultural dynamics play a pivotal role in shaping how female students in South West Nigeria universities engage with social media. Nigeria’s diverse cultural landscape influences attitudes towards technology and communication. Social media platforms serve as avenues for creative expression, social interaction, and connection within the Nigerian cultural context (Kente, Agbele, and Okocha 2023). Furthermore, societal norms and gender expectations influence how female students navigate social media. Cultural norms may dictate standards of modesty and behavior online, impacting the content they engage with and share. These cultural influences intersect with global trends, shaping the digital experiences of Nigerian female students (Seluman et al. 2024). The confluence of social comparison and cultural imperialism in the setting of Southwest Nigerian universities makes life difficult and complex for young female students. While they are a part of a local culture that could place a distinct value on certain traits, they are also exposed to Western beauty standards that are prevalent on international social media platforms. This produces a dual strain to live up to local expectations and global norms. As young women try to balance these opposing ideals, the strain between these two pressures can lead to serious stress and uncertainty about body image.

2.3 Influence of Western Perception on Nigeria Female Body Image and Beauty Standards

Understanding the relationship between social media use and body image among Nigerian women requires an exploration of how Western beauty standards intersect with local cultural ideals and the role of social media platforms in disseminating these standards. Historically, every country has held distinct perceptions of body image, often serving as standards for an ideal physique (Toselli, Rinaldo, and Gualdi-Russo 2016). Western beauty standards are frequently linked to characteristics like youthful appearance, lighter skin tones, slender physique, and Eurocentric facial features like high cheekbones and sharp noses (Stice et al. 2017). This contrasts with perceptions in non-Western countries like Nigeria, where beauty ideals often encompass larger, more curvaceous body types (Warren and Akoury 2020; Winter et al. 2019). Similarly, in Arab cultures, there was an appreciation for voluptuous hourglass figures alongside traditional modesty (Khaled et al. 2018). In Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia, curvaceous body types have been celebrated, reflecting a fusion of indigenous heritage and colonial legacies (Goldenberg 2010).

However, the proliferation of social media has significantly influenced perceptions of body image among women. The advent of social media has expanded these standards’ global reach and given the impression that they are desirable or widely accepted (Chen et al. 2020). Even in the West, these standards have changed over time and are not totally consistent. For instance, broader bodies were romanticized at different points in history, especially during the Renaissance, when figures such as the “Venus of Willendorf” represented fertility and beauty. The growth of the “curvy” form is one example of a more recent trend that shows a move away from extreme thinness and toward more voluptuous bodies. Local beauty standards, especially in locations like Southwest Nigeria, are likewise neither fixed nor easy to describe. Africa’s numerous body forms, skin tones, and features have long been treasured by various communities. Fuller bodies were traditionally associated with fertility, affluence, and good health in many African civilizations. (Balogun-Mwangi 2016) African ideals, in comparison to the Western ideal of thinness, frequently embraced more voluptuous bodies. Similarly, the emergence of colorism which is somewhat driven by global beauty trends may pose problems for darker skin tones, which are valued in some local contexts (Chithambo and Huey 2013). However, because of globalization and the widespread impact of Western media, local standards of beauty are becoming more arbitrary. The accessibility of Western media content and social media platforms has led to a convergence of local and global standards of beauty. In Nigeria, for example, there is a growing desire for thin figures, lighter skin tones, and Eurocentric features, even though bigger bodies may still be accepted in certain situations. This can be attributed in part to the emergence of Westernized beauty procedures, which mirror the absorption of Western standards and include skin-lightening lotions and cosmetic surgery (Skivko 2020). The indigenous criteria of beauty are not, however, being supplanted by Western ones as a result of this merging of interests. A mixture of beauty ideals is produced by the persistence of local standards combined with global influences. While some rural regions may cling to more traditional attitudes, urban areas, especially among younger women, may embrace certain Western beauty ideals. For example, different institutions in Nigeria may have different standards of attractiveness depending on factors including socioeconomic status, media exposure, and individual tastes. In the context of a globalized society, the idea of clearly defined beauty standards limited to a particular culture or location is becoming more challenging. Globalization of media consumption has led to a globalization of beauty standards. Due to the ongoing cross-cultural exchange of beauty trends facilitated by social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, local and international standards are becoming more and more entwined. Nigerian women navigate a complex interplay between traditional cultural values and globalized beauty standards propagated through social media, highlighting the need for nuanced interventions to promote positive body image and self-esteem.

2.4 Theoretical Framework

An appraisal of two theories, Cultural Imperialism Theory, and Social Comparison Theory, were used in this research work to capture the essence of the study concerning the impacts of social media use on female representation among female students in Southwest Nigeria Universities.

Cultural Imperialism Theory, initiated by Herbert Schiller in the 1970s, posits that powerful nations or groups impose their cultural values, beliefs, and norms on less dominant societies through media and communication channels (Schiller 1978). This theory, when applied to the usage of social media by female students in Southwest Nigeria, shows how Western beauty standards are spread via social media greatly influencing the way that young women view their own bodies. These platforms usually present Eurocentric features, light skin tones, and trim bodies as ideals of beauty, which may not be in line with traditional African beauty standards. As a result, a lot of Nigerian women start to absorb these Western norms, which could cause the standards of beauty in the country to decline.

According to Social comparison theory, individuals use information from their environment to determine their relative stands on some traits. Festinger’s social comparison theory provides a suitable framework for understanding the effect of the media on women’s body image concerns, as it suggests that women will collect information from other women to rate their own physical attractiveness and body image (Carter and Vartanian 2022). Social Comparison Theory goes on to describe how these Western ideals which are disseminated via social media directly affect how Nigerian university female students view themselves. According to this, people evaluate their own worth or social position by comparing themselves to others. Female students may engage in upward social comparisons on social media, where influencers, celebrities, and even peers frequently display idealized conceptions of beauty. They hold their bodies in comparison to the flawless and edited photos they see online, which frequently appear unachievable because of editing, filters, and selective posting. Many students may thus feel dissatisfied with their bodies and that they fall short of the ideals propagated by social media (Suls and Wills 2024). While Social Comparison Theory emphasizes the negative consequences of prolonged exposure to idealized beauty pictures on self-perception, Cultural Imperialism Theory demonstrates how Western ideals of beauty dominate social media content and influence female body image in Southwest Nigeria. Together, these ideas explain why female students in Nigerian colleges may experience body dissatisfaction and psychological anguish as they compare themselves to unachievable beauty standards. The interplay between global influence and local identity conflict offers a more comprehensive understanding of the ways in which social media influences young women’s perceptions of their bodies in this area.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research Design, Sampling Size and Technique, and Method of Data Analysis

This study employed a descriptive research design. A multi-stage sampling technique was used to determine the sample size. The initial stage involved purposively selecting 24,000 female students from two universities in Southwest Nigeria, namely the University of Ibadan and Lead City University. The total number of undergraduate students at both institutions was obtained from the office of the deputy registrar of Administrative Duty. These universities were chosen due to their location in Ibadan, the largest city in West Africa, and home to renowned Nigerian universities. Yamane’s sample size formula was subsequently employed to calculate a reliable and representative sample size, yielding an approximate value of 400 female students. Yamane’s formula is stated below:

Where n – the sample size

N = 24,000 (the population size of the study)

e = 5 % (the acceptable sampling error)

With a 95 % confidence level

In the third stage, the sample size was distributed between the two universities, with 60 % allocated to the University of Ibadan and 40 % to Lead City University, considering the former’s larger student population. The female students from these selected universities constituted the sample for this study, as depicted in Table 1, and questionnaires were administered to them accordingly. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, and mean distribution, were utilized for data analysis. Additionally, inferential statistics were used to analyze the data.

Distribution of sample size.

| Percentage of sample size | Sample size | |

|---|---|---|

| University of Ibadan | 60 % | 240 |

| Lead City University | 40 % | 160 |

| Total | 100 % | 400 |

4 Findings

4.1 Commonly Used Social Media Platforms Among Young Nigerian Women

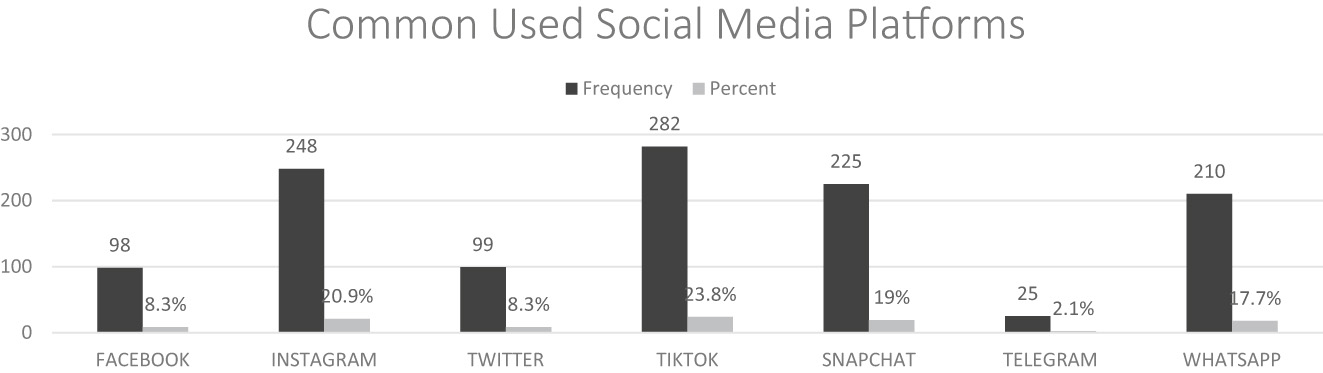

The top three most used social media platforms among young Nigerian women are TikTok 23.8 %, Instagram 20.9 %, and Snapchat 19 %. The least used social media platform by Nigerian young Nigerian women is Telegram 2.1 % as shown in Figure 1 below.

Commonly used social media platform.

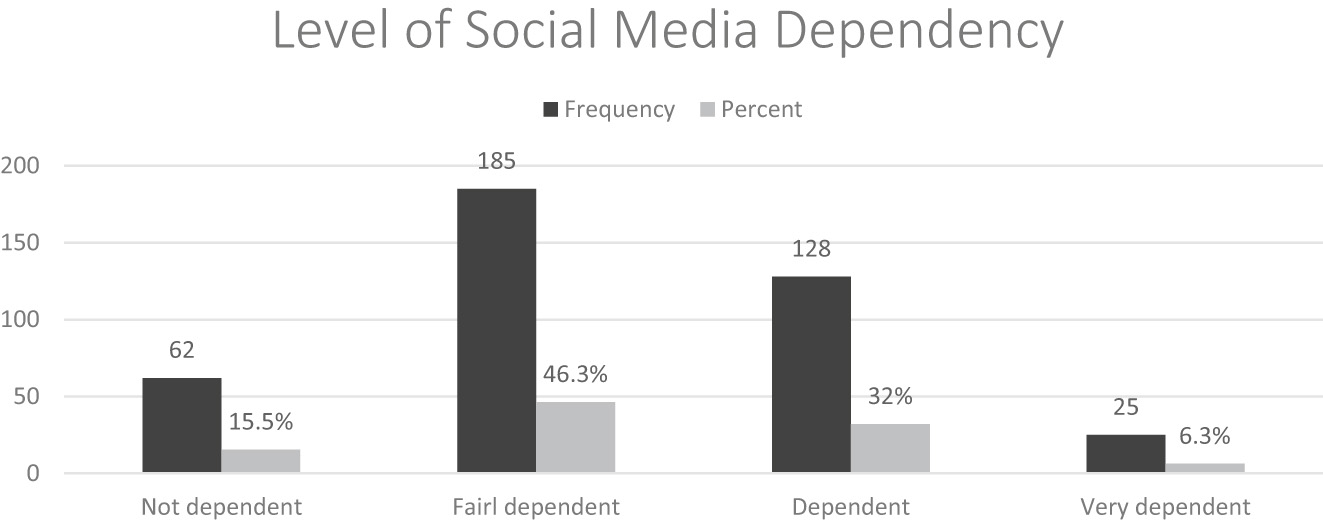

Figure 2 graph above illustrates the extent of dependency on social media activities among young Nigerian women. Only 15.5 % of participants (62 individuals) reported no dependency, while 46.3 %, 32 %, and 6.3 % of young Nigerian women displayed varying degrees of dependency: fairly dependent, dependent, and very dependent, respectively. The graph suggests a normal distribution, indicating that, on average, most young Nigerian women fall between fairly dependent and dependent on social media. Nonetheless, dependency on social media platforms exists among young Nigerian women, albeit to different extents.

Level of social media dependency.

4.2 Female Body Image Representation on Social Media Platforms

In examining the perception of social media representation among young Nigerian women. The results as displayed in Table 2 below indicated that a significant majority (63.7 %) of the respondents perceived a Western stereotypical representation of Nigerian females, while 67.8 % believed that women are objectified on social media. Additionally, 81 % felt that social media fosters the belief that females must conform to a predetermined set standard of beauty, fashion, and ideal body image, established by social media. Furthermore, 77.5 % of respondents expressed the belief that social media representations of females are more attractive than their real-life counterparts.

Perception of social media representation.

| Yes | No | Mean (Std.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think contents on social media platforms usually represent Nigeria female in a stereotypical way | 253 (63.7 %) |

147 (36.8 %) |

1.3675 (0.48273) |

| Do you think females are being objectified on these social media platforms | 271 (67.8 %) |

128 (32 %) |

1.3250 (0.47428) |

| Do you think females are being represented as following a standard set by social media concerning beauty, dressing style, and ideal body image | 324 (81 %) |

76 (19 %) |

1.190 (0.393) |

| Do you think females are being represented as being attractive more in real life | 310 (77.5 %) |

89 (22.5 %) |

1.2275 (0.42567) |

| Grand mean | 1.277 |

4.3 Effect of Social Media Representation on Young Nigerian Females

The findings indicated a strong belief among young Nigerian women that social media portrays stereotypical images of females, potentially influencing them. The overall grand mean value of 2.534 supports this perception. Specifically, 43.3 % agree and 23.5 % strongly agree that such representation reduces self-esteem (mean value of 2.8225). Furthermore, 43.8 % agree and 29.8 % strongly agree (mean value of 2.9300) that social media prompts young Nigerian women to compare their body image to videos on these platforms. The perception of body image among young Nigerian women is also affected, as indicated by 35 % agreement and 18.3 % strong agreement (mean value of 2.5275). Dissatisfaction with body structure is reported by 33.5 % agreement and 18.3 % strong agreement (mean value of 2.4825). The majority (38 % agreement and 22.3 % strong agreement, mean value of 2.6700) believe that social media influences the fashion and style choices of young Nigerian women. However, approximately 56 % of respondents (26.5 % strongly disagree and 29.5 % disagree, mean value of 2.3125) do not believe that women evaluate their beauty based on social media videos and images. Similarly, the majority (39.8 % strongly disagree and 31.8 % disagree, mean value of 1.995) do not perceive social media as impacting women’s eating habits. As presented in Table 3, the overall grand mean value of 2.534 suggests that, on average, students acknowledge the influence of social media representation on young Nigerian women.

4.4 Influence of Western Perception of Female Body Image on Nigeria Female

The logistic regression model was employed to investigate the influence of the Western perception of female body image on young Nigerian females. The table below demonstrated a significant constant value of 0.003, indicating a good fit. However, the results presented in Table 4 below indicate that the Western perception of an ideal female body image does not influence young Nigerian females’ perception of their body image.

4.5 Objective 4: Identify the Perceptions of Young Nigerian Women on Social Media

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized to examine the average perception of female stereotypes across different levels of social media dependence. As depicted in Table 5 the findings indicate that there is no significant difference in the perception of female stereotypes, regardless of the level of social media dependence. This suggests that women are stereotyped regardless of their engagement with social media (Tables 4–6).

Effect of social media body image perception.

| SD | D | A | SA | Mean (Std.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social media female representation leads to low self-esteem among Nigeria young females | 32 (0.8 %) | 101 (25.3 %) | 173 (43.3 %) | 94 (23.5 %) | 2.823 (0.882) |

| Social media female representation leads to comparing yourself or your body images or videos of other females | 41 (10.3 %) | 65 (16.3 %) | 175 (43.8 %) | 119 (29.8 %) | 2.930 (0.931) |

| Social media affects your perception of your body image | 75 (18.8 %) | 112 (28 %) | 140 (35 %) | 73 (18.3 %) | 2.528 (0.996) |

| Social media contributes to body dissatisfaction, you struggle to be satisfied with your body structure due to other females you see on social media | 87 (21.8 %) | 106 (26.5 %) | 134 (33.5 %) | 73 (18.3 %) | 2.483 (1.026) |

| You self-judge your beauty due to social media videos and images of other females you see on social media | 106 (26.5 %) | 118 (29.5 %) | 121 (30.3 %) | 55 (13.8 %) | 2.313 (1.011) |

| Social media affects your eating habits, you stopped some food to look thin like some females you see on social media | 159 (39.8 %) | 127 (31.8 %) | 71 (17.8 %) | 43 (10.8 %) | 1.995 (1.004) |

| Social media female representation affects your fashion style | 62 (15.5 %) | 97 (24.3 %) | 152 (38 %) | 89 (22.3 %) | 2.670 (0.989) |

| Grand mean | 2.534 |

-

(SD = 1–1.75, D = 1.76–2.50, A = 2.51–3.325, SA = 3.26–4).

Influence of Western perception of female body image on young Nigerian women.

| Variables in the equation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E. | Wald | Df | Sig. | Exp(B) | |

| Age | 0.258 | 0.164 | 2.492 | 1 | 0.114 | 1.295 |

| Social media dependence | −0.440 | 0.307 | 2.050 | 1 | 0.152 | 0.644 |

| Frequency | −0.241 | 0.296 | 0.661 | 1 | 0.416 | 0.786 |

| Hour | −0.018 | 0.362 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.960 | 0.982 |

| Conversant | 0.051 | 0.287 | 0.031 | 1 | 0.860 | 1.052 |

| Western perception | 0.166 | 0.244 | 0.466 | 1 | 0.495 | 1.181 |

| Constant | −1.945 | 0.649 | 8.966 | 1 | 0.003 | 0.143 |

Perception of female stereotype on social media.

| ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. | |

| Between groups | 0.540 | 3 | 0.180 | 2.046 | 0.107 |

| Within groups | 34.827 | 396 | 0.088 | ||

| Total | 35.367 | 399 | |||

Impact of social media on young female body image.

| SD | D | A | SA | Mean (Std.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I feel satisfied with my body size despite the content I see on social media as regard body image | 12 (3 %) | 21 (5.3 %) | 146 (36.5 %) | 221 (55.3 %) | 3.44 (0.730) |

| I wish my body size was more presentable like those on social media | 129 (32.3 %) | 162 (40.5 %) | 67 (16.8 %) | 42 (10.5 %) | 2.055 (0.954) |

| In comparison to other females, I see on social media, I think I need to work on my body size | 128 (32 %) | 179 (44.8 %) | 62 (15.5 %) | 31 (7.8 %) | 199 (0.887) |

| I am concerned about people’s comments about my body size on social media and it has a way of affecting my mood | 156 (39 %) | 170 (42.5 %) | 55 (13.8 %) | 19 (4.8 %) | 1.843 (0.833) |

| I Feel unhappy whenever am not achieving my desired body image as compared to people on social media | 178 (44.5 %) | 155 (38.8 %) | 47 (11.8 %) | 20 (5 %) | 1.773 (0.844) |

| I skip my meals just to achieve a particular size as suggested by people on social media | 209 (52.3 %) | 135 (33.8 %) | 38 (9.5 %) | 18 (4.5 %) | 1.663 (0.828) |

| I am on dieting pills just to have a particular body size as seen on social media | 234 (58.5 %) | 127 (31.8 %) | 28 (7 %) | 11 (2.8 %) | 1.54 (0.744) |

| I become upset whenever I feel like I am looking different from the body size or shape I see on social media | 218 (54.5 %) | 130 (32.5 %) | 32 (8 %) | 20 (5 %) | 1.635 (0.833) |

| Have you ever felt embarrassed to display your body image or appearance on social media | 203 (50.8 %) | 121 (30.3 %) | 52 (13 %) | 24 (6 %) | 1.743 (0.902) |

| Grand mean | 1.964 |

-

(SD = 1–1.75, D = 1.76–2.50, A = 2.51–3.325, SA = 3.26–4).

4.6 Impact of Social Media on Young Female Body Image

The logistic regression model was used to examine the influence of social media on young female body representation with which we were able to get a significant constant value of 0.00 indicates a well-fitting model at a 1 % level of significance.

The set of questions above in Table 6 investigates the impact of social media on body image perception among young female students, framed by cultural imperialism theory and social comparison theory.

For the statement, “I feel satisfied with my body size despite the content I see on social media regarding body image,” 36.5 % agree and 55.3 % strongly agree, resulting in a mean acceptance value of 3.44, indicating strong agreement. This aligns with social comparison theory, suggesting that some individuals may resist external standards. Conversely, the statement, “I wish my body size were more presentable like those on social media,” falls within the disagree region, yielding a mean acceptance value of 2.055; 32.3 % strongly disagree and 40.5 % disagree, reflecting the tension between local and Western beauty standards as suggested by cultural imperialism theory. Regarding the statement, “In comparison to other females I see on social media, I think I need to work on my body size,” 32 % strongly disagree and 44.8 % disagree, resulting in a mean acceptance value of 1.990, also within the disagree region. This indicates a degree of resistance to the pressures of social comparison. For the statement, “I am concerned about people’s comments about my body size on social media, and it has a way of affecting my mood,” 39 % strongly disagree and 42.5 % disagree, yielding a mean acceptance value of 1.843, reinforcing the notion that social media influences perception through external validation.

Additionally, the statement, “I feel unhappy whenever I am not achieving my desired body image compared to people on social media,” shows 44.5 % strongly disagree and 38.8 % disagree, yielding a mean acceptance value of 1.773. This suggests that while some are affected, many reject these imposed ideals. The statement, “I skip meals just to achieve a particular size as suggested by people on social media,” indicates 52.3 % strongly disagree and 33.8 % disagree, yielding a mean acceptance value of 1.663, indicating that drastic measures are not widely embraced. In contrast, the statement, “I am on dieting pills just to have a particular body size as seen on social media,” receives 58.5 % agreement and 31.8 % strong agreement, yielding a mean acceptance value of 1.54, indicating concern about social media’s influence. Similarly, the statement, “I become upset whenever I feel like I am looking different from the body size or shape I see on social media,” shows 54.5 % agree and 32.5 % strongly agree, yielding a mean acceptance value of 1.635, suggesting that social comparison impacts emotional well-being. Lastly, for the statement, “Have you ever felt embarrassed to display your body image or appearance on social media?” 50.8 % agree and 30.3 % strongly agree, resulting in a mean acceptance value of 1.743, indicating significant concern regarding body representation. The grand mean value of 1.964 suggests that, on average, young Nigerian women disagree that social media negatively impacts their body representation, highlighting the complex interplay between social media influences, cultural standards, and personal perceptions. All these findings are presented in Table 6.

5 Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined social media usage among young Nigerian women, revealing that over 99 % of female Nigerian youths were active on at least one social media platform, with approximately 76 % using multiple platforms frequently this goes in line with Rachubinska, Cybulska, and Grochans (2021) which he states that 27.2 % of women were prone to the risk of social media addiction in a study conducted among young Polish women (Rachubinska et al. 2021). The study also found varying degrees of dependency on social media.

Regarding the perception of social media representation of women, the study indicated a majority consensus among young Nigerian women that social media often presents a distorted or exaggerated view of females, as against what is obtainable in real life. However, most young Nigerian females do not adhere to the Western notion of an ideal body image or skin tone, this finding gives credibility to the statement of who stated that every country has a peculiar picture of what an ideal body is. Therefore, most Nigerian female youths do not like to have the thin frame of Western women and are not working on achieving it either. Young Nigerian women feel more confident in their skin tone and would not consider trying to achieve the Western woman’s skin tone, which is contrary to the findings of Mady et al. (2023) who completed a cross-national qualitative study in India, Egypt, and Ghana, and found that lightness of skin tone has been a culturally imposed prerequisite for young female to be considered beauty based on social media influence. In terms of the impact of social media on young female body representation, the study found that young Nigerian females do not perceive a significant influence from social media. Most young Nigerian women feel satisfied with their body size despite the content they encounter on social media, In comparison to other females, on social media, young Nigerian females do not think they need to work on their body image. Regarding the perception of female stereotypes on social media, the study did not find a significant presence of such stereotypes, as indicated by the value of 0.107, which was not statistically significant.

Based on the findings of this study and drawing from the theoretical frameworks of Cultural Imperialism Theory and Social Comparison Theory, several key conclusions can be drawn regarding social media usage and its impact on female representation among young Nigerian women. Firstly, the high prevalence of social media usage among young Nigerian women, as evidenced by over 99 % of female Nigerian youths being active on at least one social media platform, aligns with Cultural Imperialism Theory. This theory suggests that Western cultural values and norms, including beauty standards, are disseminated through media channels and may influence local perceptions. However, the study’s finding that most young Nigerian females do not adhere to Western beauty ideals, such as thinness or light skin tone, indicates a resistance to cultural imperialism. Instead, Cultural Imperialism Theory may manifest in the perception of distorted or exaggerated representations of females on social media, highlighting the influence of Western media while also showcasing the resilience of Nigerian cultural values. Secondly, Social Comparison Theory provides insights into how young Nigerian women navigate social media platforms in comparison to Western standards of beauty. Despite exposure to idealized images on social media, many young Nigerian females report feeling satisfied with their body size and confident in their skin tone. This suggests that social comparison processes may differ across cultural contexts, with Nigerian women potentially engaging in upward or lateral comparisons that reinforce positive self-perceptions rather than fostering body dissatisfaction. Furthermore, the absence of significant female stereotypes on social media, as indicated by the statistically insignificant value, underscores the complexity of female representation in digital spaces. While Western media may perpetuate stereotypes, Nigerian women’s experiences on social media platforms may deviate from these narratives, reflecting a nuanced interplay between cultural influences and individual agency. In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that while social media usage is pervasive among young Nigerian women, the impact on female body image perceptions is mediated by cultural factors and individual experiences. By examining these dynamics through the lenses of Cultural Imperialism Theory and Social Comparison Theory, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how social media has been influencing female identity and body image in the Nigerian context. Moving forward, interventions aimed at promoting positive body image and challenging stereotypes should consider the unique socio-cultural landscape of Nigeria and the diverse experiences of young Nigerian women in digital spaces.

References

Ajaegbu, Oguchi O., Chizurumoke O. Ikechukwu, Omolayo O. Jegede, and Oluwafisayo O. Ogunwemimo. 2021. “Instagram Use and Female Undergraduates’ Perception of Body Image.” International Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences 22 (4): 99–116.Suche in Google Scholar

Bair, Carrie E., Nichole R. Kelly, Kasey L. Serdar, and Suzanne E. Mazzeo. 2012. “Does the Internet Function Like Magazines? An Exploration of Image-Focused Media, Eating Pathology, and Body Dissatisfaction.” Eating Behaviors 13 (4): 398–401, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.06.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Balogun-Mwangi, Oyenike. 2016. “Embracing the Hottentot Venus: A Mixed-Methods Examination of Body Image, Body Image Ideals and Objectified Body Consciousness among African Women.” Dissertation, Northeastern University. https://www.proquest.com/openview/ed542daae3cfb3f59ed03d3a64dfcec9/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750.Suche in Google Scholar

Brown, Jane D., and Piotr S. Bobkowski. 2011. “Older and Newer Media: Patterns of Use and Effects on Adolescents’ Health and Well-Being.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 21 (1): 95–113, 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00717.x.10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00717.xSuche in Google Scholar

Carter, Jeanne J., and Lenny R. Vartanian. 2022. “Self-concept Clarity and Appearance-based Social Comparison to Idealized Bodies.” Body Image 40 (3): 124–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Toby, Kristina Lian, Daniella Lorenzana, Daniella Shahzad, and Daniella Wong. 2020. “Occidentalisation of Beauty Standards: Eurocentrism in Asia.” International Socioeconomics Laboratory 1 (2): 1–11.Suche in Google Scholar

Chithambo, Taona P., and Stanley J. Huey. 2013. “Black/White Differences in Perceived Weight and Attractiveness Among Overweight Women.” Journal of Obesity 2013 (1): 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/320326.Suche in Google Scholar

Goldenberg, Mirian. 2010. “The Body as Capital. Understanding Brazilian Culture.” VIBRANT-Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 7 (1): 220–238.Suche in Google Scholar

Henriques, Mavis, and Debasis Patnaik. 2020. “Social Media and its Effects on Beauty.” In Beauty - Cosmetic Science, Cultural Issues and Creative Developments, edited by Martha, Peaslee Levine, and Júlia, Scherer Santos. London: IntechOpen.10.5772/intechopen.93322Suche in Google Scholar

Kemp, Simon. 2023. “Digital 2023: Global Overview Report.” DataReportal. Singapore: Data Reportal. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-global-overview-report (accessed December 14, 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Kente, Josiah Sabo, Damilare Joshua Agbele, and Desmond Onyemechi Okocha. 2023. “New Media and Indigenous Cultural Identities in Nigeria.” Journal of Communication and Media Research 15 (1): 104–17.Suche in Google Scholar

Khaled, Salma, Bethany Shockley, Yara Qutteina, Linda Kimmel, and Kien Trung. 2018. “Testing Western Media Icons Influence on Arab Women’s Body Size and Shape Ideals: An Experimental Approach.” Social Sciences 7 (9): 142, https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090142.Suche in Google Scholar

Kumar, Lalit. 2023. “Social Media Influencers’ Impact on Young Women’s Acceptance of Beauty Standards.” International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews 10 (2): 597–614.Suche in Google Scholar

Mady, Sarah, Dibyangana Biswas, Charlene A. Dadzie, Ronald Paul Hill, and Rehana Paul. 2023. “A Whiter Shade of Pale: Whiteness, Female Beauty Standards, and Ethical Engagement across Three Cultures.” Journal of International Marketing 31 (1): 69–89, https://doi.org/10.1177/1069031x221112642.Suche in Google Scholar

Maikaba, Balarabe, and Aondover Eric Msughter. 2019. “Digital Media and Cultural Globalisation: The Fate of African Value System.” Humanities and Social Sciences 7 (6): 220, https://doi.org/10.11648/j.hss.20190706.15.Suche in Google Scholar

Miller, Gabrielle. 2023. “Exploiting Non-Western Women in Media Representations.” Sprinkle: An Undergraduate Journal of Feminist and Queer Studies 10 (1): 8.Suche in Google Scholar

Molina-Ruiz, R., I. Alfonso-Fuertes, and S. González Vives. 2022. “Impact of Social Media on Self-Esteem and Body Image among Young Adults.” European Psychiatry 65 (S1): S585, https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.1499.Suche in Google Scholar

Monks, Helen, Leesa Costello, Julie Dare, and Elizabeth Reid Boyd. 2020. “We’re Continually Comparing Ourselves to Something’: Navigating Body Image, Media, and Social Media Ideals at the Nexus of Appearance, Health, and Wellness.” Sex Roles 84 (3): 221–37, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01162-w.Suche in Google Scholar

Rachubinska, Kamila, A. M. Cybulska, and E. Grochans. 2021. “The Relationship Between Loneliness, Depression, Internet and Social Media Addiction among Young Polish Women.” European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 25 (4): 1982–9, https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202102_25099.Suche in Google Scholar

Sasu, Doris Dokua. 2023. “Total Number of Active Social Media Users in Nigeria from 2017 to 2023.” Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1176096/number-of-social-media-users-nigeria/.Suche in Google Scholar

Schiller, Herbert I. 1978. “Media and Imperialism.” Revue française d’études américaines 6 (1): 269–81, https://doi.org/10.3406/rfea.1978.1008.Suche in Google Scholar

Seluman, Ikharo, Aghawadoma Eguono, Arikenbi Peter Gbenga, and Ainakhuagbor Aimiomode. 2024. “Stereotypical Portrayal of Gender in Mainstream Media and its Effects on Societal Norms: A Theoretical Perspective.” International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation 5 (1): 743–9.Suche in Google Scholar

Skivko, Maria. 2020. “Deconstruction in Fashion as a Path Toward New Beauty Standards: The Maison Margiela Case.” ZoneModa Journal 10 (1): 39–49.Suche in Google Scholar

Steinsbekk, Silje, Lars Wichstrøm, Frode Stenseng, Jacqueline Nesi, Beate Wold Hygen, and Věra Skalická. 2021. “The Impact of Social Media Use on Appearance Self-Esteem from Childhood to Adolescence–A 3-Wave Community Study.” Computers in Human Behavior 114 (4): 106528, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106528.Suche in Google Scholar

Stice, Eric, Jeff M. Gau, Paul Rohde, and Heather Shaw. 2017. “Risk Factors that Predict Future Onset of Each DSM-5 Eating Disorder: Predictive Specificity in High-Risk Adolescent Females.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 126 (1): 38–53, https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000219.Suche in Google Scholar

Suls, Jerry, and Thomas Ashby Wills. 2024. Social Comparison : Contemporary Theory and Research. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003469490Suche in Google Scholar

Toselli, Stefania, Natascia Rinaldo, and Emanuela Gualdi-Russo. 2016. “Body Image Perception of African Immigrants in Europe.” Globalization and Health 12 (1): 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0184-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Valkenburg, Patti M., and Jessica Taylor Piotrowski. 2017. Plugged In: How Media Attract and Affect Youth. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.10.12987/yale/9780300218879.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Warren, Cortney S., and Liya M. Akoury. 2020. “Emphasizing the ‘Cultural’ in Sociocultural: A Systematic Review of Research on Thin-Ideal Internalization, Acculturation, and Eating Pathology in US Ethnic Minorities.” Psychology Research and Behavior Management 13 (2020): 319–30, https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s204274.Suche in Google Scholar

Winter, Virginia Ramseyer, Laura King Danforth, Antoinette Landor, and Danielle Pevehouse-Pfeiffer. 2019. “Toward an Understanding of Racial and Ethnic Diversity in Body Image among Women.” Social Work Research 43 (2): 69–80, https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svy033.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Determining the Transcultural Value of Free Flow in Digital Communication Platforms

- Social Media Use and Its Impacts on Body Image Perception Among Female Students in Southwest Nigeria Universities

- “Others Are Misled, Not Me”: Third-Person Perception and Misinformation Sharing Among Chinese Elderly on WeChat

- Organizational Communication and Workplace Dynamics: The Impact of Paid Family Leave Policies During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Transcending Boundaries Through Xianxia: Chinese TV Drama Consumption by Global Audiences in a Cross-cultural Context

- Book Review

- Zhao, Tingyang: The Whirlpool that Produced China: Stag Hunting on the Central Plain

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Determining the Transcultural Value of Free Flow in Digital Communication Platforms

- Social Media Use and Its Impacts on Body Image Perception Among Female Students in Southwest Nigeria Universities

- “Others Are Misled, Not Me”: Third-Person Perception and Misinformation Sharing Among Chinese Elderly on WeChat

- Organizational Communication and Workplace Dynamics: The Impact of Paid Family Leave Policies During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Transcending Boundaries Through Xianxia: Chinese TV Drama Consumption by Global Audiences in a Cross-cultural Context

- Book Review

- Zhao, Tingyang: The Whirlpool that Produced China: Stag Hunting on the Central Plain