Abstract

Chinese animation, which originated in the 1920s, has undergone over a hundred years of historical evolution and has become an important medium for the transcultural communication of Chinese culture. This study is based on Debray’s mediology, using multimodal discourse analysis as the research method. From three dimensions: morphological changes, dynamic structures, and cultural approaches, it explores why Chinese animation has experienced innovation, inheritance, and renewal, as well as the media logic that assists in the transcultural communication of Chinese culture. In the dual context of globalization and the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, Chinese animation must overcome the rigid binary opposition between China and the West under the protection of cultural policies, media technology, and industrial economy. Based on Chinese culture and guided by the concept of “plural civilization,” Chinese animation should exchange, learn from other cultures, and enhance its transcultural communication ability.

1 Introduction

In the 1920s, a group of animation pioneers, such as Zuotao Yang, Wennong Huang, Lifan Qin, Xuechu Mei, and the Wan Brothers, made unremitting explorations that enabled Chinese animation to establish itself early in the world of animation. During the war, the Wan Brothers drew nourishment from traditional Chinese stories, integrating patriotism and national spirit, and created Asia’s first full-length animated film, Princess Iron Fan. From then on, Chinese animation began to move onto the international stage. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the stable social environment, top-level design of national cultural and artistic ideas, innovation in animation production technology, and exchange and learning with the global animation industry jointly created the internationally renowned “Chinese animation school.”

After the reform and opening up, the reform of the economic and cultural system, as well as the impact of foreign animation, have prompted Chinese animation to pursue innovation amid challenges. After entering the 21st century, the revival of Chinese animation has become an important symbol of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation in the field of popular culture. Chinese animation, based on traditional Chinese mythological stories such as Journey to the West: The Return of the Great Sage, Ne Zha, and White Snake: Origins, has produced a text aggregation and linkage effect, building a “domestic animation universe.” Chinese animation has once again entered the international arena and attracted global attention. Undoubtedly, Chinese animation has become an important medium for spreading Chinese culture and shaping the image of China.

Currently, the academic community is highly concerned about the cultural phenomenon of transcultural communication in Chinese animation. Many studies have analyzed the current difficulties and strategies of transcultural communication (Tian 2022), or starting from practical cases of Chinese comics going global, have explored the effectiveness of Chinese comics in transcultural communication (Guo 2021). However, there is a lack of diachronic examination of the transcultural communication of Chinese animation from a theoretical perspective, and a lack of reflection on how the nationalization of Chinese animation can exchange and learn from global popular culture. The study of transcultural communication in Chinese animation urgently needs to break through the linear causal logic aimed at dissemination effects, place Chinese animation in different historical contexts, and explore the internal connection between Chinese animation, the Chinese cultural system, and global popular culture.

Debray’s mediology is a set of theories that integrates technology, culture, and history, with a focus on examining how media plays a mediating role in specific historical and cultural contexts. This mediological perspective, which differs from functionalism and technological determinism, helps to deeply examine why Chinese animation has become a “transmission device” for Chinese culture.

2 Mediology and Transcultural Communication of Chinese Animation

2.1 Understanding Mediology

Debray first introduced mediology in his 1979 publication The Power of Knowledge in France and developed it in subsequent works such as The Manifesto of Mediology, A Course in General Mediology, The Life and Death of Images, and Introduction to Mediology. Debray defined “medium” as “a collection of symbolic means of transmission and circulation under specific technological and social conditions” (Debray et al. 2014), which highlights the historical limitations of media identity, specifically that “medium is not only a technological and cultural system but also a historical structure” (Chen 2016). Debray pointed out that the starting point of mediology studies is to explore the relationship between technology and culture, aiming to clarify various phenomena in transmission (Debray et al. 2014). Therefore, the means of communication in mediology studies have a dual meaning: firstly, technical configuration, such as the presentation of audio-visual symbols, decoding programs, their various reception paths, infrastructure, and physical objects for transmission and diffusion; secondly, cultural configuration, such as thematic concepts, systems and customs, discourse, and rituals.

At present, academic research on mediology tends to focus on two areas: one is the study of Debray’s mediology theory, and the other is the application of this theory to analyze specific concepts and things. In terms of research on mediology studies, a study analyzed McLuhan and Debray’s different understandings of media and their different spatiotemporal perspectives, suggesting that McLuhan is more focused on spatial dimensions, while Debray focuses on the study of the transmission of ideology and faith, analyzing the key role of social organizations in transmission, and focusing on the temporal dimensions. Although the two cannot merge, there is an intersection in their thinking on the technical level, which leads to a reflection on humanism (Huang 2017). In terms of theoretical application, scholars have introduced the perspective of mediology analysis into fields such as image editing, TV drama, social reading, literary criticism, book and digital publishing, and heritage protection, greatly expanding the academic field of mediology. A study from the perspective of mediology studies, using “technological configuration” and “cultural configuration” as frameworks, conducts a case analysis of the iconic works of the New Yangko Movement as “culture objects,” providing another observation and interpretation of this important event in the history of Chinese revolutionary culture (Zhang 2020). A study has conducted mediology interpretation of overseas Chinese restaurants, believing that they serve as emotional media for spreading Chinese culture, coordinating the social relationships between overseas Chinese and residents of the host country, and carrying out cultural imagination and practice about “China” (Zhang 2018).

Through the above discussion, we can find that Debray’s mediology theory is a set of theories that integrate technology, culture and history, and its focus is to investigate how the medium can play an intermediary role in a specific historical and cultural context. This mediology perspective, which is different from functionalism and technological determinism, is helpful to investigate how Chinese animation carries out transcultural communication in different historical and cultural contexts, and why Chinese animation has become the medium of transcultural communication of Chinese culture.

2.2 Understanding Transcultural Communication

In some studies, “cross-culture,” “inter-culture,” and “transcultural” are often used in a confused manner. This study will analyze these three concepts to demonstrate the appropriateness of the term “transcultural” used in this context. In terms of intellectual history, “cross-culture” focuses on comparative research, “inter-culture” stems from anthropology with a strong interpretive tradition, and “transcultural” is rooted in philosophical reflections on human interaction, emphasizing co-existence and interdependence. Both cross-cultural and inter-cultural communication studies are inspired by anthropologists who intend to understand the differences between cultures and explore the deep structures of each cultural system (Jiang et al. 2021). After the second wave of modernization, the development of radio, television, and other media greatly promoted exchanges and cooperation between countries. The differences and conflicts between different cultures have prompted scholars to start thinking about how to solve problems such as cultural differences, communication barriers and cultural identity. The concept of the intercultural communication came into being. This concept was first proposed by American scholar Edward Hall in the 1950s. It refers to the process of information, ideology, values and so on being transmitted, communicated and understood between different cultures. However, this concept is often based on the simplification and solidification of culture, assuming that culture is stable and consistent. It does not recognize the dynamics and variability of culture at the time level, and also ignores the complexity and differences within culture. It overemphasizes the values and importance of Western culture, which exacerbates the inequality and conflict between cultures. In the 1990s, the concept of “transculturality” was put forward by Wolfgang Welsch, a German philosopher and aesthetician. In the article “Transculturality – the Puzzling Form of Cultures Today,” he criticized the traditional culture research model and the theory of interculturality and multiculturality (Welsch 1999). He believes that “transculturality” emphasizes the complex relationship between different cultures. On this basis, Wolfgang Berg carried out research on transcultural people and transcultural personalities (Berg and Éigeartaigh 2010). They all recognize the cultural commonness and cultural relevance, emphasize respect for cultural differences, advocate for cultural exchanges and mutual learning, and see the new future brought by cultural integration. From the perspective of intellectual history, both “cross-culture” and “inter-culture” continuously strengthen and deepen the color of colonial and post-colonial ideology and spread hegemony, while “transculture” is thinking from the perspective of anti-anthropology, anti-colonialism, and anti-orientalism, which encapsulates comparatively deeper philosophical thoughts (Jiang, Croucher and Ji 2021).

2.3 Transcultural Communication of Chinese Animation

In terms of transcultural communication research on Chinese animation, the academic community has examined various aspects, including the communication process, practical difficulties, and strategies. One study analyzed Chinese animation films’ awards in international film festivals since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China and proposed suitable paths for the transcultural communication of Chinese animation films that integrate both “transcultural” and “nationalization” (Hu 2017). Another study discussed the opportunities and challenges for Chinese animation to go global in the internet era (Zhu 2020). Research has highlighted the importance of focusing on production concepts, original content, promotion and marketing, and international cooperation to enhance the global dissemination of Chinese animation and the international influence of Chinese culture. This is an important task and inevitable path for the innovative development of China’s animation industry (Tian 2022). A study has analyzed the insufficient influence of Chinese animation films in transcultural communication from 2018 to 2022 through research methods such as data statistics and data analysis, and proposed innovative strategies for the transcultural communication of animation films (Niu 2023). These studies have provided important insights into the transcultural communication of Chinese animation, but there has been a lack of in-depth analysis from a theoretical perspective. Over the past century, Chinese animation has played a significant role in spreading Chinese culture across different historical periods. Therefore, it is essential to move beyond the simple cause-and-effect dissemination model, place Chinese animation within historical contexts, and explore its connections to both the Chinese cultural system and global popular culture.

Debray’s mediology theory integrates technology, culture, and history, offering a valuable perspective to analyze how Chinese animation facilitates transcultural communication. This study will start from Debray’s theory, using “technological configuration” and “cultural configuration” as frameworks to analyze the evolution of Chinese animation across different historical stages. By combining theoretical perspectives with historical contexts, the process of transcultural communication of Chinese animation can be divided into three stages: (1) the 1940s, when Chinese animation inspired national spirit, (2) the late 1950s to the late 1980s, when Chinese animation gained international recognition with its “Chinese animation school,” and (3) from the late 1990s to the present, with the rise of the “domestic animation universe” that explores cross-civilization themes.

3 Research Design

3.1 Research Method

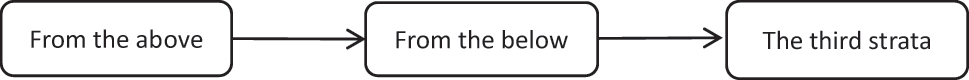

This study uses the multimodal discourse analysis method. Multimodal discourse refers to the phenomenon of using various senses – such as auditory, visual, and tactile – and communicating through various means, symbols, and systems, such as language, images, sounds, and actions (Zhang 2009). The construction of meaning in information dissemination is not only dependent on language but also involves the integration of various symbolic resources. Wildfeuer links the interpretation of film discourse with systemic functional linguistics and social semiotics, pointing out that meaning in film is dynamically constructed by different symbolic resources, in order to better explain the harmonious interaction between different modalities (Wildfeuer 2014). Matthiessen divides multimodal features into three strata: from above, from below, and the third strata (Matthiessen 2006). This study examines representative Chinese animation films from different historical stages of the transcultural communication of Chinese culture, and proposes corresponding strategies and suggestions to address the difficulties and problems faced in the transcultural communication of Chinese animation films (Table 1).

The list of representative Chinese animation films for overseas dissemination.

| Historical stage | Chinese animation films |

|---|---|

| The first stage | Princess Iron Fan |

| The second stage | The Monkey King |

| The third stage | Monkey King: Hero Is Back, Ne Zha |

3.2 Analytical Framework

Behind the transcultural communication of Chinese animation films lies a mediology issue of technological and cultural interaction. The means of communication in mediology have dual implications: firstly, technical configuration, such as the presentation of audio-visual symbols, decoding programs and their various reception paths, infrastructure and physical objects for transmission and diffusion; the second is cultural configuration, such as subject concepts, systems and customs, discourse and rituals, etc. (Zhang 2020). Therefore, the “technical configuration” of Chinese animation’s overseas dissemination includes production technology, audio-visual texts, communication channels, etc.; “Cultural configuration” includes creative concepts, industrial policies, industry ecology, etc. Among them, technological innovation, conceptual updates, and textual innovation constitute the internal tension of overseas dissemination of Chinese animation; Policy evolution, ecological optimization, and media evolution constitute the external driving force for the overseas dissemination of Chinese animation. The mutual construction of “technological configuration” and “cultural configuration” drives the ongoing update and reconstruction of Chinese animation in different historical contexts, becoming a “transmission device” for the transcultural communication of Chinese culture. This study will adopt Debray’s mediology theory, along with Matthiessen’s classification of multimodal features, to carry out an analysis. The analytical framework includes “from above,” which looks at the historical context of transcultural communication of Chinese animation films at different stages, “from below,” which focuses on the use and characteristics of multimodal resources, and “the third stratum ,” which analyzes the visual grammar of Chinese animation films (Figure 1).

Analytical framework.

4 The Transcultural Communication Process of Chinese Animation

4.1 The Origins of Transcultural Communication of Chinese Animation in the Context of Turmoil and Transformation

In 1931, with the escalation of the War of Resistance Against Japan escalated, patriotism and national salvation became central themes. Amid the national salvation, early Chinese animation pioneers broke away from entertainment-focused productions, creating patriotic animations such as Sincere Unity, Compatriots Awakening Quickly, and Aviation Saving the Country. Among them, the animation film Camel Dancing adapted from fables utilized grouped sound collection technology, becoming China’s first animation film with sound. The birth of this animation film marks the transition of Chinese animation technology from the exploratory stage of fragments to a more mature stage of technological application. The development of technology has provided strong support for the development of Chinese animation. In 1940, the Wan Brothers were inspired by the American animation film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and decided to use relevant clips from Journey to the West to adapt it into the animation film Princess Iron Fan, pushing ancient Chinese princesses to the world stage. However, due to limitations in economy, personnel, technology, and other aspects, the Wan Brothers had no choice but to give up many good creative ideas. In order to make this film, they organized more than 100 people to participate in painting and drew nearly 20,000 sketches. After a year and a half of arduous filming, it was finally completed and released at the end of 1941, and was broadcast in Southeast Asia countries, Japan and beyond, gaining influence beyond international boundaries.

In the history of world animation films, Princess Iron Fan has become the fourth large-scale animation film after Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Lilliput, and Puppetry Adventures. Its success is closely related to the “cultural configuration” and “technological configuration” in the context of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. In the early 1940s, it was not uncommon to suppress and ban artistic works that promoted nationalism and resistance against Japanese aggression. In order to avoid direct conflicts with the policy of suppressing artistic works, the filmmakers at that time cleverly used the technique of borrowing from the past to satirize the present to imply national unity and resist foreign enemies, which can be seen as a major feature of film works of this period. The plot of Princess Iron Fan is also influenced by such works, with a conscious allegorical storyline. In the film, Tang Monk and his disciples, as well as the villagers near the Flame Mountain, unite and fight against the enemy, ultimately extinguishing the Flame Mountain, defeating and expelling the villains Princess Iron Fan and Bull Demon King. This symbolizes the unity and unwavering spirit of the times among the masses. In terms of animation production, this film is the first to bring Chinese landscape painting to the screen and extensively incorporates the stylistic features of Chinese opera art, endowing each important character with distinct personality traits and giving them a strong national characteristic. The design of the Princess Iron Fan comes from the female hero image in the popular supernatural martial arts films at that time, with delicate features and neat attire. Tang Monk’s appearance is weak and scholarly, with a cowardly personality. The appearance of Zhu Bajie is chubby, lazy, selfish, and silly. In terms of technical features, the film presents the flames in black and white film as red by alternately shaking red, yellow, and blue glass in front of the projector lens during projection.

At this historical stage, facing the difficult situation of material difficulties, outdated equipment, and foreign technological monopolies, Chinese animation that spread overseas is mainly represented by the Wan Brothers’ Princess Iron Fan and has not yet formed a certain scale. Although Chinese animation at this time had not yet formed a theory and style, the national spirit it carried could be seen in the midst of difficulties. The creator “plays its due combat role” in the animation content (Wan 1986: 70). Driven by the dual factors of the external war environment and internal national awareness, creators spontaneously combined with real-life struggles in the production of animation, integrating the collective unconscious national sentiment into it, laying the foundation for the future nationalization of Chinese animation. Princess Iron Fan takes traditional Chinese stories as resources, draws inspiration from American animation styles, and injects the will to inspire national spirit into it, developing its own national style. The national spirit and style it embodies have greatly increased the international influence of Chinese animation. Therefore, Chinese animation has been using traditional Chinese stories as resources and continuously exploring the path of nationalization, laying the foundation.

Overall, Chinese animation at this stage is only characterized by encouraging the national spirit and integrating a variety of Chinese cultural elements. Although the content of the film does not reflect the integration of multiple cultures, the theme of the film contains the anti-colonial connotation of “transcultural communication.”

4.2 “Chinese Animation School”: Exploring the “Medium Opportunities” on the Road of National Style

After the outbreak of the Pacific War, early pioneers of Chinese animation went their separate ways, and the Chinese animation industry stagnated for a time. However, after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, a stable social environment and government support provided ample space for development. In the 1950s, Chinese animation shifted towards learning from Soviet animation and produced works with real-life themes.

One pivotal moment came in 1955 with Why Are Crows Black, which won the 8th Venice International Children’s Film Festival Award but was mistakenly thought by many international audiences to be a Soviet film. This led Chinese creators to realize that Chinese animation should not simply mimic Soviet or Western styles but explore its own national identity.

Since the 1950s, in order to ensure the development of Chinese animation, the national government has taken numerous measures, providing “cultural configuration” and “technological configuration” for the nationalization of Chinese animation. In 1956, at the expanded meeting of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, Mao Zedong proposed the policy of “a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend.” In 1957, according to the plan of the Director’s Meeting of the Film Bureau of the Ministry of Culture, Shanghai Film Studio was renamed Shanghai Film Production Company, and expanded into Shanghai Art Studio on the basis of the original factory’s art group. The establishment of an art studio provides a more favorable development platform for the research and production of animation films. The art studio set up puppet, Paper-cuttings and animation departments, and later developed and added two new forms of expression, Paper-cuttings and origami, to enrich the variety of animation. In 1959, the Shanghai Municipal People’s Committee approved the expansion of the Shanghai Fine Arts Film Studio, which expanded various departments and ensured stable production space for animation, promoting more diverse themes and types of Chinese animation.

In terms of expression, Chinese animation films have gradually shifted from traditional and single displays to various forms, and their stories and content are more inclined towards Chinese classical themes, fables, and folk stories. The content is more closely related to daily life, with regional and ethnic characteristics, refining the content, elevating the theme, and making the animation more abundant internally. Chinese animation creators consciously and spontaneously explore the national style of Chinese animation, leading to an increasing number of works incorporating national characteristics and forming animation works with Chinese characteristics, reaching the climax of the “Chinese School” animation creation. Around the 1960s, the “Chinese School” reached a stable state of high output, continuously improving in form and content, and creating a number of high-level works. The first and second episodes of The Monkey King, released in 1961 and 1964 respectively, are important representative works. The film has won awards such as the Special Short Film Award at the 13th Karlovi Fali International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia and the Best Film Award of the 22nd London International Film Festival and other awards, expanding its international popularity. The design of characters or scenes in the film draws on the essence of ancient statues, murals, buildings and temples, and comprehensively displays Chinese culture in front of the world through painting, which is a comprehensive display with Chinese style. This film vividly portrays Sun Wukong, a Chinese mythological hero, on the screen, and exaggerates the traditional forms of gods. In terms of content, this film on Sun Wukong’s story of causing trouble in the Dragon Palace and rebelling against the Heavenly Court, highlighting his wit, optimism, bold resistance to authority, fearless spirit, and fighting personality, reflecting the sharp conflict between the oppressors and the oppressed. This film opens the way for Chinese animation to draw on traditional myths and interpret the spirit of the times. And expanding the overseas influence of Chinese animation. After 1966, Chinese animation production was reduced or even temporarily stopped. Until 1977, Chinese animation fully resumed production and reached a new creative peak in the 1980s.

In the 1980s, the development of Chinese animation gradually reached a climax. The “Chinese School” draws nourishment from classical literature, idioms, history, and mythology on the one hand, and presents the diversity of Chinese animation national styles in terms of expression forms. At the same time, it maintains various types of development in animation production forms. Unlike Chinese animation in the 1960s, animation in the 1980s was more modern in terms of story content and expression. The quality and output of Chinese animation far exceeded previous levels, and it can be said that it reached a new peak of the “Chinese school” animation. The formation of the new peak of the “Chinese School” animation was inseparable from the “cultural configuration” and “technological configuration” at that time. From the perspective of “cultural configuration,” after the reform and opening up, communication among Chinese animation producers has become more frequent. In 1984, in order to promote theoretical research and animation production, the first animation society of the People's Republic of China was established. The organization of the society was established, gathering a group of theoretical and professional creators, which had a good promoting effect on better exploring and organizing activities related to animation. Chinese animation creators have participated in international exhibitions multiple times, which has also promoted exchanges between Chinese animation and international peers, and promoted the nationalization and transcultural communication of Chinese animation. In addition, film studios gradually explored market economy from the planned economy stage. Films have begun to implement a responsibility contract system, and in the process of production and distribution, film studios need to bear the losses themselves. In this way, some film studios not only measure the artistic quality of animation in their production, but also gradually think about profitable commercialization, injecting vitality into the production and transcultural communication of Chinese animation. From the perspective of “technical configuration,” with the accumulation of time, Chinese animation has found and summarized a series of application techniques in the process of exploration. China has also established multiple animation factories and expanded the development of animation films.

In the late 1980s, under the wave of reform and opening up, many excellent foreign animations entered the audience’s field of vision. Their innovative presentation techniques and commercialized plot quickly attracted a large number of audience attention. At the same time, Chinese animation, stimulated by foreign animation, turned to cater to market changes, giving up the advantages of the original national style of animation, and gradually moving towards commercialization in terms of design and content. However, due to the lack of in-depth research on the production mode and structure of foreign animation, Chinese animation after the 1990s generally lacked uniqueness. At this stage, there have been new changes in the “cultural configuration” and “technological configuration” of Chinese animation. From the perspective of “cultural configuration,” the theme of Chinese animation not only draws inspiration from classical stories, but also creates different protagonist images through the adaptation of new era stories, which is an attempt and reflection on the content and form transformation of animation under market and commercial reforms. From the perspective of “technological configuration,” with China’s accession to the international internet, the application range of computers has been growing. In term of animation production technology, all drawing programs can be simplified, greatly reducing labor costs. The animation technology represented by digitization has gradually replaced traditional hand manual painting, thus improving animation productivity. However, under the impact of foreign multi element cultures, the “Chinese School” animation has entered a stumbling exploration period. With the development of media such as the Internet, Chinese animation has also followed the times and entered another chapter.

Overall, at this stage, with policy support and market drive, Chinese animation began to innovate the expression mode and explore the cultural exchange and mutual learning embodied in “transcultural communication” on the basis of Chinese elements.

4.3 “Domestic Animation Universe”: A “New Medium” for Recreating Transcultural Communication of Chinese Culture

The “Domestic Animation Universe” is a cross media story world construction that starts from classical myths and legends. It centers around animation and integrates various media forms such as comics, games, television, movies, and mobile internet. These story worlds have strong text reproduction capabilities, and related texts have a certain market appeal, forming a fixed audience fan group (Bai 2022). In the 1990s, under the wave of market economy, exchanges between Chinese and foreign animation became more frequent, and many foreign animations entered the view of Chinese audiences, causing a serious impact on the development of Chinese animation. Under market pressure, Chinese animation actively caters to market changes and moves towards commercialization in both form and content. However, due to lack of a balance between commercial value and cultural value, Chinese animation lost its original ethnic style for a while. Faced with the new social and cultural environment, Chinese animation producers are attempting to adjust their artistic concepts, technological applications, and ethnic styles. In 1999, the first domestically produced commercial animation film, The Lotus Lantern, was released. By learning from the Hollywood film industry, this animation film not only improved the industrial level of Chinese Film, but also achieved the effect of telling Chinese stories in world language. Afterwards, Chinese animation gradually formed mythological story worlds such as Journey to the West, The Legend of the White Snake, and The Legend of the Gods. With the aggregation and linkage of story texts, the concept of “domestic animation universe” gradually became popular in the online space.

In 2015, Monkey King: Hero Is Back opened a new chapter in the “domestic animation universe” with a completely new face. In the context of the revival of Chinese animation, Chinese animation such as Ne Zha, White Snack, and Legend of Deification have appeared one after another. These Chinese animation films, based on traditional Chinese myths and stories, are rediscovered and reintroduced in the context of the times, integrating various media forms such as comics, games, television, etc. Producing a text aggregation and linkage effect, and building a “domestic animation universe,” which not only has a profound impact on the development of Chinese animation films, but also has a hug overseas impact. The Monkey King: Hero Is Back architecture is based on the original novel Journey to the West and is further expanded and interpreted according to traditional Chinese mythological stories. In terms of character design, Sun Wukong is not the traditional Monkey King, but rather an unorthodox and rebellious hero with an unconventional appearance. In terms of music, each character has music that matches their personality traits. In terms of content, the film tells the story in the familiar Hollywood style of road movies, running through ever-changing and grand scenes. Technically, it adopts panoramic 3D construction, with prototypes for every plant and tree, from the grand scenes to the magical forest in the style of Avatar, to the heavenly palace and castle in the style of the Lord of the Rings. It portrays the rugged folk style of Chang'an, the Five Elements Mountain Cave lined with giant Buddhas, and the enchanting suspended temple in a rich and detailed manner. Starting from the context and emotional structure of the times, Ne Zha boldly breaks through the traditional character design and reshapes the character image through a narrative method of “unfamiliarity,” depicting the growth story of civilian heroes with “black circles” and “shark teeth.” This not only resonates emotionally with the vast domestic audience, but also enables foreign audiences to overcome cultural barriers and understand this Chinese animation as a story about fighting against fate, subtly enhancing their understanding of Chinese mythological characters and their recognition of the spirit of the Chinese nation such as self-improvement and tenacious struggle.

Under the dual effects of “cultural configuration” and “technological configuration,” Chinese animation has once again become a “new medium” for the transcultural communication of Chinese culture. In terms of “cultural configuration,” since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the government has introduced a series of favorable policies to promote the “going out” of Chinese culture, promoting many Chinese animation companies to interact and exchange with other countries. At the production concept level, Chinese animation insists on coordinating the relationship between “nationalization” and “internationalization.” It does not return to ink painting, paper-cuttings, shadow puppets and New Year pictures in the era of “art films,” nor imitate Disney in an all-round way. Instead, it focuses on the excavation and integration of traditional culture and contemporary spirit on the basis of absorbing the nutrients of national art and humanistic spirit. In other words, the “tradition” in Chinese animation has been reinvented in the ongoing game between nationalism and cosmopolitanism. It can be seen that the significance of the “plural civilization view” in artistic creation is that traditional China, as a regional state form, market form, and unique worldview system, can not only become a reinterpretation of China’s “living tradition” today, but also an important resource for thinking about human society outside of “modernity.” This does not mean “returning to the Chinese Empire,” but rather incorporating it as a critical intellectual resource to rebuild China’s dominant position in the global landscape. From the perspective of “technical configuration,” the audio-visual language and communication channels of Chinese animation have also made further leaps in this stage. The updates and iterations of technological equipment have led an increasingly diverse range of audio-visual languages in Chinese films, 3D animation films, VR animation films, and more not only make the visuals more exquisite, but also bring immersive audio-visual enjoyment to the audience. In terms of communication channels, the transcultural communication of Chinese animation no longer only depends on the way of holding animation exhibitions and winning awards. The development of Internet technology has provided technical support for the transcultural communication of Chinese animation, further promoting its overseas dissemination and expanding its overseas influence.

Overall, at this stage, Chinese animation further explored the integration of multiculturalism, showing the relevance between cultures, that is, it generated new cultural forms in the exchange and mutual learning of cultures, reflecting the connotation of “transcultural communication.”

5 The Difficulties and Problems Faced in the Overseas Dissemination of Chinese Animation

At present, the biggest obstacle to the transcultural communication of Chinese animation is cultural discounts. Firstly, due to different cultural backgrounds, overseas audiences find it difficult to fully understand the Chinese cultural and concepts contained in Chinese animation. How to reduce cultural discounts in transcultural communication and gain a larger audience recognition of the values and cultural themes of the film from different countries and regions is the primary issue facing Chinese animation. Secondly, Chinese animation has not yet formed a mature animation industry chain. The animation industry, as a part of the cultural and entertainment industry, is also a manifestation of the country’s soft power, playing an important role in spreading national culture, national image, and values. Most countries with developed cultural industries have formed mature industrial chains, it is particularly necessary to improve the Chinese animation industry chain. Thirdly, the content of Chinese animation needs further innovation. Through the in-depth study of “mediology” and “transcultural communication,” we can find that only by continuously promoting cultural exchanges and mutual learning, can we produce more new cultural works that meet the context of the times and the needs of the audience.

6 Conclusions

In conclusion, Chinese animation has evolved significantly over time, supported by cultural and technological factors, and has become a critical medium for transcultural communication. Debray’s mediology theory helps us recognize that transcultural communication is not an abstract process but an economic activity integrated into the global consumer society. To succeed, Chinese animation must transcend rigid binary oppositions between China and the West and embrace a pluralistic view of civilization.

In the future, Chinese animation should seek to establish a recognizable cultural landscape and build a “text star cluster” of interconnected story worlds. In this star cluster of objects, understanding the objectmeans understanding the process accumulated within it. As a star cluster, theoretical thinking revolves around the concept it wants to open, hoping to suddenly open it like a lock on a heavily protected safe: not by a key or a number, but by a combination of numbers (Theodore 1993: 161). And cosmopolitanism means a “value star cluster,” in which nationalist values are not subject to the domination of a “highest principle,” but enter into a dialogue relationship with other values (Jin 2015). Therefore, “trans-cultural” and “nationalization” are two issues that we must face, and the two are not independent of each other, but a mutually inclusive and growing relationship. Cross-culture must be established on the premise of a widely accepted shared value system, and nationalization is the main purpose of Chinese animation to disseminate the excellent traditional culture of its nation to the outside world. Improving the transcultural communication of Chinese animation mainly includes the following aspects: Firstly, relevant departments should establish and improve supporting policies for the transcultural communication of Chinese animation. Starting from a global perspective and strategic thinking, they should strengthen the overall layout and guidance for the transcultural communication of Chinese animation, and promote the refinement and scale of Chinese animation by integrating advantageous resources. Under the guidance of policies, Chinese animation enterprises should balance the relationship between commercial value and cultural value, actively undertake the mission of transcultural communication of Chinese culture, leverage the advantages of capital, technology and experience, find local partners, and establish an international animation industry cooperation mechanism centered on Chinese animation through localized operations. In the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative, animation should be used as the medium to achieve two-way cultural exchanges and dissemination between China and participating countries. The academic community should strengthen research on the transcultural communication of Chinese animation and deeply explore the inherent laws of Chinese animation transcultural communication from a rational perspective. Secondly, in terms of animation creation, it should focus on the most universal content in Chinese national culture, selecting relevant issues of the consciousness of a community with a shared future for mankind and basic characteristics of human nature as the focus of creation. The representative content of Chinese national culture should be creatively transformed in a way that is understandable to the global public, and flexibly integrate and rewrite the core ideas of Chinese culture with modern and global cultures.

References

Bai, Huiyuan 白惠元. 2022. “Guochan donghua yuzhou: Xinshiji Zhongguo donghua dianying yu minzuxing gushi shijie” 国产动画宇宙:新世纪中国动画电影与民族性故事世界 [Domestic Animation Universe: Chinese Animation Movies and the World of National Stories in the New Century]. Yishu pinglun 艺术评论 2022 (02): 52–67. https://doi.org/10.16364/j.cnki.cn11-4907/j.2022.02.006.Search in Google Scholar

Berg, Wolfgang, and Aoileann Ní Éigeartaigh, eds. 2010. Exploring Transculturalism: A Biographical Approach. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media.10.1007/978-3-531-92440-3Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Weixing 陈卫星. 2016. “Xinmeiti de meijiexue wenti” 新媒体的媒介学问题 [Mediology Issues in New Media]. Nanjing shehui kexue 南京社会科学 2016 (02): 114–22, https://doi.org/10.15937/j.cnki.issn1001-8263.2016.02.017.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Yan 郭艳. 2021. “Chaoyue yuyan biaoda: chuhai guoman duomotai xushi huayu fenxi” 超越言语表达:出海国漫多模态叙事话语分析 [Beyond Verbal Expression: Multimodal Narrative Discourse Analysis of Overseas Chinese Comics]. Huazhong keji daxue 华中科技大学. DOI:10.27157/d.cnki.ghzku.2021.000430.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Bo 胡泊. 2017. “Cong ‘minzu yuanchuang’ dao ‘IP zhuanhuan’: Zhongguo donghua dianying haiwai chuanbo de qianshijinsheng” 从“民族原创”到“IP转换”:中国动画电影海外传播的前世今生 [From “Ethnic Originality” to “IP Conversion”: The Past and Present of Overseas Communication of Chinese Animation Films]. Dangdai dianying 当代电影, 2017 (06): 143–6.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Hua 黄华. 2017. “Jishu, zuzhi yu ‘chuandi’: Mcluhan yu Debray de meijie sixiang he shikong guannian” 技术、组织与“传递”:麦克卢汉与德布雷的媒介思想和时空观念 [Technology, Organization, and “Communication”: Mediology Thought and Time Space Concept of McLuhan and Debray]. Xinwen yu chuanbo yanjiu 新闻与传播研究, 24 (12): 36–50+126–7.Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, Fei, Stephen Michael Croucher, and Deqiang ji. 2021. “Editorial: Historicizing the concept of transcultural communication.” Journal of Transcultural Communication 1 (1): 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1515/jtc-2021-2001.Search in Google Scholar

Jin, Huimin 金惠敏. 2015. “Jiazhi xingcong——chaoyue Zhong Xi eryuan duili siwei de yizhong lilun chulu” 价值星丛——超越中西二元对立思维的一种理论出路 [Value Star Cluster – A Theoretical Way out beyond the Dual Opposition of Chinese and Western]. Tansuo yu zhengming, 探索与争鸣, 2015 (7): 59–62.Search in Google Scholar

Matthiessen, Christian M. I. M. 2006. “The Multimodal Page: A Systemic Functional Exploration.” In New Directions in the Analysis of Multimodal Discourse, edited by Terry, D. Royce and Wendy, Bowcher, 1–62. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Niu, Yiman 牛伊曼. 2023. “Zhongguo donghua dianying 2018–2022 nian haiwai chuanbo yingxiangli yanjiu” 中国动画电影2018—2022年海外传播影响力研究 [Research on the Overseas Communication Influence of Chinese Animation Movies from 2018 to 2022]. Daguan luntan, 大观论坛, 2023 (6): 123–5.Search in Google Scholar

Regis, Debray. 2014. Putong meijiexue jiaocheng 普通媒介学教程 [General Mediology Course]. Translated by Weixing, Chen and Yang, Wang. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Theodore, Adorno. 1993. Fouding de bianzhengfa 否定的辩证法 [Negative Dialectics]. Translated by Feng, Zhang. Chongqing: Chongqing Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Tian, Suna 田苏娜. 2022. “Goujian xinxing guojihua hezuo jizhi tisheng Zhongguo donghua haiwai chuanboli” 构建新型国际化合作机制提升中国动画海外传播力 [Building a New International Cooperation Mechanism to Enhance the Overseas Broadcasting Power of Chinese Animation]. Zhongguo guangbo dianshi xuekan, 中国广播电视学刊, 2022 (10): 84–7.Search in Google Scholar

Wan, Laiming 万籁鸣. 1986. Wo yu Sun Wukong 我与孙悟空 [Me and Sun Wukong]. Taiyuan: Beiyue Literature and Art Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Welsch, Wolfgang. 1999. “Transculturality: The Puzzling Form of Cultures Today.” Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World 13 (7): 194–213.10.4135/9781446218723.n11Search in Google Scholar

Wildfeuer, Janina. 2014. Film Discourse Interpretation: Towards a New Paradigm for Multimodal Film Analysis. London: Routledge.10.4324/978020376620Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Delu 张德禄. 2009. “Duomotai huayu fenxi zonghe lilun kuangjia tansuo” 多模态话语分析综合理论框架探索 [Research on the Comprehensive Theoretical Framework of Multimodal Discourse Analysis]. Zhongguo waiyu, 中国外语 2009 (1): 24.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Kaibin 张凯滨. 2018. “Haiwai zhongcanguan yu Zhonghua wenhua zou chuqu——yizhong putong meijiexue de shijiao” 海外中餐馆与中华文化走出去——一种普通媒介学的视角 [Overseas Chinese Restaurant and Chinese Culture Going Global: A Perspective of General Media Studies]. Zhongzhou xuekan, 中州学刊, 2018 (12): 166–72.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Yongfeng 张勇锋. 2020. “Cong ‘meijie geming’ dao ‘geming meijie’: Yanan xin yangge yundong zai kaocha” 从“媒介革命”到“革命媒介”:延安新秧歌运动再考察 [From “Media Revolution” to “Revolutionary Media”: A Further Study of the Yan’an New Yangko Movement]. Xinwen daxue, 新闻大学, 2020 (10): 55–68+120.Search in Google Scholar

Zhu, Yilun 朱逸伦. 2020. “Hulianwang shidai Zhongguo donghua zou chuqu de jiyu yu tiaozhan” 互联网时代中国动画走出去的机遇与挑战 [Opportunities and Challenges for Chinese Animation to Go Global in the Internet Era]. Zhongguo dianshi, 中国电视, 2020 (03): 62–7.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Uncertainty Avoidance, News Genres and Framing of Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Content Analysis of News from Seven Countries

- Subsistence and Resistance in the Consumption of Counterfeits in South Africa

- Strategies in Expressing Condolences Via Social Networking Sites: The Case of Instagram and Facebook

- Cultural Bias in Large Language Models: A Comprehensive Analysis and Mitigation Strategies

- Exploring the Role of Social Media on International Students’ Adaptation in the Process of Transcultural Communication Within the Context of the Belt and Road Initiative

- A Mediology Study on the Transcultural Communication of Chinese Animation

- Interview

- Exploring the Intersection of Communication and Labor: A Dialogue with Dan Schiller

- Book Review

- McQuire, Scott, and Wei Sun: Communicative Cities and Urban Space

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Uncertainty Avoidance, News Genres and Framing of Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Content Analysis of News from Seven Countries

- Subsistence and Resistance in the Consumption of Counterfeits in South Africa

- Strategies in Expressing Condolences Via Social Networking Sites: The Case of Instagram and Facebook

- Cultural Bias in Large Language Models: A Comprehensive Analysis and Mitigation Strategies

- Exploring the Role of Social Media on International Students’ Adaptation in the Process of Transcultural Communication Within the Context of the Belt and Road Initiative

- A Mediology Study on the Transcultural Communication of Chinese Animation

- Interview

- Exploring the Intersection of Communication and Labor: A Dialogue with Dan Schiller

- Book Review

- McQuire, Scott, and Wei Sun: Communicative Cities and Urban Space