Abstract

This study explored how government institutions used digital platforms to enhance knowledge and share scientific information regarding the development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines by drawing samples from official Twitter accounts in five different countries that were front-runners in vaccine manufacturing. Through content analysis, we selected a total of 243 tweets with 4,678 comments from the five Twitter accounts, and data were categorized into two sets for analysis, the first stage being to assign sentiment scores to all the collected comments from tweets to determine their positivity, negativity, and neutrality. Secondly, we analyzed themes derived from comments and established through the themes that geopolitics has exacerbated the anti-intellectualist logic of viewing science as impractical for the control and prevention of the pandemic leading to the domination of irrational thinking towards vaccine efficacy, the origin of COVID-19, and the undermining of the global health governance on COVID-19 control and management.

1 Introduction

In accordance with the United Nations Agenda 2030-Sustainable Development Goal promoting good health and well-being (Clark & Horton, 2019; Kickbusch, 2016; Powell et al., 2015), the World Health Organization (WHO) and global stakeholders are actively addressing the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which poses significant challenges to global health systems (Ciotti et al., 2020; Ditlhokwa, 2022; Lal et al., 2021).

During public emergencies, governments and international organizations extensively utilize digital platforms for mass communication and public outreach (Hancu-Budui et al., 2020). However, these institutions often intertwine information dissemination with the promotion of services and political interests, potentially influencing public opinion (Osborne et al., 2022; Ruggeri & Samoggia, 2018; Yu et al., 2018).

Current academic interest revolves around the dynamics of vaccine production and distribution. Divergent views, rooted in science-based evidence or anti-intellectualist approaches tied to geopolitical interests, contribute to ongoing debates (Wood & Schulman, 2021). Anti-intellectualism, described by Peters (2019) as a ‘virus,’ has historical roots in McCarthyism, manifesting as attacks on intellectuals and scholars due to the “democratization of knowledge” (p. 1). This phenomenon, initially a focus in American society, is now expanding globally (Merkley, 2020).

To comprehend anti-intellectualism’s manifestations, we consider three perspectives: religious anti-rationalism (favoring conservatism over progressivism), populist anti-elitism (revolting against the elite), and unreflective instrumentalism (disregarding the power of knowledge) (Geurkink et al., 2019; Rigney, 1991). This study aims to explore the interactions between state institutions (Ministries of Foreign Affairs-MFA’s) on Twitter and their audience regarding the provision of scientific and sustainability information related to COVID-19 vaccine production and distribution, with a focus on how anti-intellectualism manifests in this context. Building on previous research, we draw connections between historical shifts in anti-intellectualism and contemporary anti-vaccine movements on digital platforms to formulate our research questions.

2 The Historical Change of Anti-intellectualism

The concept of anti-intellectualism, as articulated by Douglas Hofstadter in 1963, has been extensively examined within academic discourse, evolving from its roots in education to encompass politics and, more recently, the realm of social media. Howley et al. (1993) noted a significant setback in the intellectual connection between education and the political economy, attributing it to a disconnection between the intellectual mission of schools and the societal demand for a knowledge-based labor force, particularly in the context of American society. This observation aligns with Cross’s (1990) perspective, which associates intelligence with intellect and suggests historical cynicism toward intellect alongside an endorsement of elitism in American society, particularly in the nineteenth century.

Building upon Hofstadter’s earlier contributions, Robert’s argument considers various predictors of anti-intellectualism, including perceived liberalism, religion, conventional attitudes, and shortcomings in educational reforms. Shogan (2007) further rationalizes the heavy influence of partisan politics and polarization, highlighting how anti-intellectualism became a political tool in American society, serving as a “conservative form of populism” (p. 295) during presidential terms, notably benefiting figures like Eisenhower, Reagan, and George W. Bush.

Within the broader spectrum of intellect and anti-intellectualism, there is evidence of a noticeable shift, particularly in the involvement of political or presidential advisers who, despite ostensibly embracing intellectualism, exhibit anti-intellectualistic actions that prioritize political ideologies over expertise. This phenomenon, referred to as “intellectual dabblers,” was evident even in the presidency of Donald Trump, who accused climate scientists of colluding with Chinese businesses to manipulate information on climate change during his 2016 campaign (Motta, 2018). A comparative analysis of Trump and Eisenhower’s presidencies reveals differing approaches to anti-intellectualism, despite operating within the same political space. Eisenhower was known for his rhetorical style, contrasting sharply with Trump’s embrace of the post-truth era (Reyes, 2020). This transition is also marked by a shift from traditional information sources such as radio, television, and newspapers to the widespread adoption of social media platforms.

Since the rise of social media usage in the late 20th century, public discourses have been transformed by at least two sets of underpinnings; the news media and the ordinary social media user. According to Braun and Gillespie (2011), the extent of user-generated content on social media platforms which is absolutely outside the operational boundaries of traditional media has at least been able to put a layer of protection on issues such as hate speech, etc. Freedom of expression, on the other hand, has formed part of bigger discourses on whether or not, individuals, through their social media accounts/profiles, would enjoy the autonomy and the comfort to air their opinions on a wide range of issues without restrictions. Some researchers suggest that discourses premised on freedom of speech differ according to social class, with political leaders being given the leeway to post content that can be outlawed to ordinary citizens (Arun, 2018), while some believe that the recent COVID-19 pandemic has been a perfect example of some governments using it to impose internet censorship on their publics (Vese, 2021). However, it remains a big question to determine the position of anti-intellectualism between the two opposing sides of freedom of speech and the rife of misinformation or fake news.

3 Literature Review

3.1 COVID-19 Vaccines, Geopolitics, and Populism

A populist approach toward global governance, multilateralism, and the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic continue to spark mixed conceptions of the ongoing vaccination campaigns, donations, and distribution across the globe. According to Su et al. (2021), many refer to this gesture as a way to entrap the world into vaccine diplomacy by the vaccine-producing countries. However, the researchers argue that such is crucial to the unequal distribution of vaccines. That being the case, the arrival of COVAX as a vaccine-sharing and distribution initiative would attempt to fill in the gaps of vaccine inequity by promoting proportionate global access. This would even end the “vaccine apartheid” as it subverted global health principles (de Bengy Puyvallée & Storeng, 2022, p. 2). The two concepts (vaccine diplomacy and vaccine apartheid) as argued by the studies above serve as a pivot between expert and populist views on global access to the vaccine, where proponents of the vaccine diplomacy perception represent populist views led by geopolitical dynamics, conflicting interests, and fear to lose the grip on world domination. According to Chagla and Pai (2021), and Hassan et al. (2021), vaccine apartheid continues to expand the divide between high-income and low-income countries, as evidenced by the scramble for vaccines that took place until late 2021, by which the WHO Director-General called for vaccine equity (Bajaj et al., 2022).

The issuance of vaccination certificates has also become topical as regards vaccination populism. According to Lee (2021), the requirement to show vaccination certificates to get access to certain places could suggest a wider polarization between economically advanced countries and the less developed ones, citing its repercussions on international travel and diplomacy. Voo et al. (2022), on the other hand argue that differential public health and social interventions should be looked at, with full consideration of ethical measures and the potential that comes with vaccination certificates to undermine international health protocols, save for proof of vaccination. Despite their arguments, the WHO Smart Vaccination Certificate consortium echoes the need for vaccination certificates to manage the vaccine rollout, which hinged upon data minimalization and inclusivity. However, the digital divide emanating from poor Internet access in some areas has also become a hindrance to these efforts (Gelb & Mukherjee, 2021).

3.2 Anti-intellectualism and Multi-discourse Ecosystem Towards Vaccine Uptake

Despite COVID-19 being the most recent pandemic, there is already a growing inquiry about the role played by both experts and the public, where discourses about trust in science, religion, and culture are highlighted (Gozum et al., 2021; Lavazza & Farina, 2020; Ting et al., 2021). Hofstadter’s approach posits that anti-intellectualists always hold paradoxical views toward the existence of science and expert consensus on issues of public concern, with public health being a major concern in the recent pandemic (Merkley, 2020; Peters, 2019). According to Morelock and Narita (2022), a series of conspiracy theories related to the COVID-19 pandemic has been on the rise, leading to the spread of unfounded claims about the virus and vaccines. In their study conducted on 54 countries, Islam et al. (2021) discovered more than six hundred rumor items generated about the COVID-19 vaccine, backed by conspiracies were shared on social media platforms and various search engines. In that context, countries such as the United States, India, and Brazil had the highest level of conspiracies. These included among others, the perceptions that COVID-19 was a bioweapon and vaccines were created to keep increasing virus mutations, further suggesting that microchips would be planted into the human body through vaccines-an alleged strategy by the vaccine-producing countries to monitor people. It is however not surprising that some of the above-mentioned countries got entangled in these conspiracies, given that they were also at the forefront in the production and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.

Merkley and Loewen (2021) examined anti-intellectualism in how audiences engaged with the expert advice on the rules, guidelines, and precautions about the COVID-19 pandemic. Their survey-based study revealed that in countries like Canada, the public was less concerned about the risks associated with flouting the prescribed COVID-19 prevention guidelines. Even though a wide range of issues on anti-intellectualism was discussed, a gap exists that links the popularization of anti-intellectualist comportment with much emphasis on drawing sentiments from comments on digital platforms such as Twitter during the pandemic, and how such interactions unmasked the geopolitical fight for COVID-19 vaccine production and distribution. Based on the above-discussed literature, we aim to fill the existing gap by answering the following research questions:

RQ1:

What sentiments emerged from the audiences’ response to the delivery of messages about the COVID-19 vaccine production and distribution on the five Twitter accounts?

RQ2:

Based on research question 1, what themes informed anti-intellectualistic views from the audiences’ responses to the same tweets?

4 Twitter in Diplomacy and Public Service

Apart from being used as a social media communication tool, Twitter is now a popular instrument used by political leaders to communicate international relations agendas (Duncombe, 2017). As the steeplechase to combine the traditional and digital means of diplomacy deepens, governments and state actors have engaged in the act of ‘Twiplomacy’ where Twitter and diplomacy have been merged, and most recently, the platform has been a source for vaccination campaigns led by presidents, ministers, and ambassadors, who on repeated occasions posed for photos while taking COVID-19 jabs to encourage mass vaccination (Chhabra, 2020). With public service and diplomacy continuing to blur the physical borders through communication using digital platforms, there is a need to theorize the impact of these messages on the public and how relationships are built when the social space is used for official matters.

5 Theoretical Framework: Dialogic Communication

Drawing from Kent and Taylor’s (1998) framework, this study positions itself within the context of government agencies’ interactions with the public on digital platforms, with a particular focus on Twitter. Embracing dialogic communication, the study emphasizes negotiation as a pivotal element in building relationships between organizations and the public, establishing a dynamic where both parties engage as equal partners (Sommerfeldt & Yang, 2018). This approach extends traditional rubrics for public relations, fostering two-way symmetrical and asymmetrical communication, that facilitates the exchange of ideas and opinions. The essence of this communication is encapsulated in the symbolism of a dialogue, emphasizing the crucial aspects of communication and feedback (Kent & Taylor, 1998).

Kent & Taylor’s dialogic communication framework is structured around five principles relevant to online communication. These principles include the dialogic loop, representing the interaction where audiences pose queries and organizations provide feedback; the importance of offering useful and valuable information; the generation of return visits, where the audience is enticed to revisit the platform multiple times; the intuitiveness and user-friendliness of the interface; and the conservation of visitors, aiming to retain users on the site.

While initially formulated in the context of the World Wide Web, this theory has evolved to encompass contemporary technological landscapes, extending its applicability beyond traditional websites to include social media platforms. The study recognizes and integrates the evolving role of social media platforms as foundational components within the broader scope of Kent & Taylor’s dialogic communication framework.

When exploring how organizations used Twitter to engage their stakeholders, Rybalko and Seltzer (2010) applied dialogic communication to their study and found that Twitter had aided to a certain extent, the dialogic loop, usefulness of information, and conservation of visitors, on a wide range of occasions, although other dialogic principles such as generation of return visits and the intuitiveness/ease of the interface were less utilized. This is so because the companies being studied also provided useful information and links to their websites for visitors to verify any additional information if needed. Deflecting business-oriented dialogic communication as outlined by Rybalko & Seltzer above, the theory has also been applied in crisis management communication, suggesting its influence on reducing negative perceptions and confusion by encouraging public engagement (Yang et al., 2010). Considering the need for engagement in a dialogic communicative approach, we also ask the following research question:

RQ3:

Based on research questions 1 and 2, how was the online relationship between the five Twitter accounts and the audiences’ dialogic relationship toward trusting science in vaccine production and efficacy? To help build and answer this question, we hypothesize the following:

H1:

Most government institutions use digital platforms to advance political interests and divisions during global crises, while they do not focus more on how they can ignite dialogue on how science and technology benefit the public, and how the public understands and interprets these messages, ultimately leading to the escalation of anti-intellectualism towards the management of the pandemic.

6 Methodology

This study adopted mixed methods to collect and analyze data. The data sets were both quantitatively and qualitatively dealt with by first assigning sentiment scores to determine the positivity, negativity, and neutrality of audiences (qualitative), and later the sentiments were quantitatively treated to determine their frequency, percentages, and average scores. Secondly, the researchers extracted the most common themes from all the comments, which is a purely qualitative approach.

7 Data Collection Process

Data were manually collected from five Twitter accounts (@MFA_China, @StateDept, @IndianDiplomacy, @GermanyDiplo, @FCDOGovUK). See Table 1 below. During this process, we attempted to collect all the tweets and comments from all the accounts listed above. However, in most cases, some comments seemed to be deleted/removed or hidden from timelines, hence we ended up treating only the data we were able to retrieve as presented in Table 1 above, where the data was arranged according to the maximum number of tweets each account had, from the bigger to a smaller number.

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

| Country | Tweets collected | Comments | Date range |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 156 | 4 051 | Feb-Dec 2021 |

| UK | 63 | 241 | May 2020-Oct 2021 |

| China | 13 | 276 | Nov 2020-Oct 2021 |

| India | 9 | 96 | March-Sept 2021 |

| Germany | 2 | 14 | March-Nov 2021 |

| Totals | 243 | 4 678 |

The data collection process started with identifying the keyword to search for our data and “COVID-19 vaccine” became the most suitable. This was followed by a selection of dates to collect data, from 2020-03-01 to 2021-12-31 so that we only collect data from or around the time when WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic to the time when multiple vaccine trials had been conducted (Kim et al., 2021). It is worth mentioning that in Twitter accounts for the USA, India, and Germany, there was no information posted in 2020 related to our topic or research. Only China and the UK had posts from as back as 2020. The second task was to open every tweet that appeared on our searches and carefully copy each thread, starting with the original tweet and all the comments into an Excel spreadsheet. This would help keep track of the total number of tweets, comments, and their date of posting. After all the data were collected, we engaged in preparing the data for analysis which is discussed in the next section.

8 Data Analysis

The collected data were categorized into two sets for analysis, the first stage being to assign sentiments to all the collected comments from tweets using the Azure Machine Learning tool to determine their positivity, negativity, and neutrality. The algorithmic feature in Azure grants that, the closer the sentiment score is to 1, the higher its positivity while the closer it is to 0, the higher its negativity, with the neutral sentiment always at the midpoint score of 0.5 (Andersson et al., 2018). The analysis for the second data set was to identify themes, derived from the most frequent words used in the comments. In this regard, we relied on the bag of words (word cloud) feature in the Orange data mining tool by analyzing words based on their frequency of appearance (usage). The more the word appeared, the higher the frequency that word was used in the comments and the bigger it appeared on the word cloud. This was aided by the embedded programming language found in the tool of analysis (Thange et al., 2021, pp. 198–203). As a result, all the words from the main data set were condensed into a single word cloud for analysis. The analysis arrangement follows the same order as indicated in Table 1.

9 Results

RQ1 asked how the audience responded to the delivery of messages about the COVID-19 vaccine production and distribution from each of the five Twitter accounts. The results below show the collected and analyzed comments from each Twitter account, by assigning sentiment scores to determine their positivity, negativity, and neutrality.

10 United States of America (@StateDept)

Out of the 156 tweets collected from the @StateDept Twitter account, positive sentiments showed a huge disparity with the neutral sentiments, more than it was with the negative sentiments. The average sentiment remained at 0.5, which translates to a neutral overall sentiment (see Table 2 below).

@StateDept sentiments from comments (n = 4051).

| Sentiment | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 1 275 | 31 % |

| Neutral | 770 | 19 % |

| Positive | 2 006 | 50 % |

11 Germany (@GermanyDiplo)

From the 2 tweets collected from (@GermanyDiplo), there was almost a tie between the positive and negative sentiments, with only a difference of 2 in their frequencies. The frequency of neutral sentiments on the other hand was less than half of the negative sentiment, leading to the average sentiment score of 0.5 just like in the previous Twitter account (see Table 3 below).

@GermanyDiplo sentiments from comments (n = 14).

| Sentiment | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 5 | 36 % |

| Neutral | 2 | 14 % |

| Positive | 7 | 50 % |

12 India (@IndianDiplomacy)

In the comments collected from 9 tweets in this account, positive sentiments greatly surpassed all the other sentiments combined (see Table 4 below). The average sentiment suggested a positive sentiment at 0.6, which is slightly above the neutral sentiment.

@IndianDiplomacy sentiments from comments (n = 62).

| Sentiment | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 12 | 19 % |

| Neutral | 5 | 8 % |

| Positive | 45 | 73 % |

13 China (@MFA_China)

Out of the 13 tweets from this account, positive sentiments became higher than both negative and neutral sentiments (see Table 5). Like the previous Twitter account, the average sentiment became positive, slightly over the neutral mark at a 0.6 score.

@ MFA_China sentiments from comments (n = 276).

| Sentiment | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 84 | 30 % |

| Neutral | 42 | 15 % |

| Positive | 150 | 54 % |

@FCDOGovUK sentiments from comments (n = 241).

| Sentiment | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 73 | 30 % |

| Neutral | 38 | 16 % |

| Positive | 130 | 54 % |

14 United Kingdom (@FCDOGovUK)

The 63 tweets from this Twitter account produced more positive sentiments than the other sentiments, similar to the previously analyzed accounts (see Table 6). The average sentiment stood at a 0.5 score, indicating an overall neutral sentiment.

Based on the sentiment analysis, the following example shows the kind of allocations to the three sentiments.

Negative: “vaccines” are not the answer.

Neutral: To whom nobody wants that.

Positive: It would still be better if we supported dropping patents, so there can be global manufacturing.

15 Themes

RQ2 asked about the themes that informed anti-intellectualistic approaches from the audiences’ responses to the tweets. To address this question, we first identified the most frequently used words from the comments (see Figure 1). Words such as the hashtag “nomore”, “vaccine”, “China”, “virus”, and “free” became the top five frequently used words.

Most frequently used words. Source: Word cloud from Orange (3.32).

Theme 1:

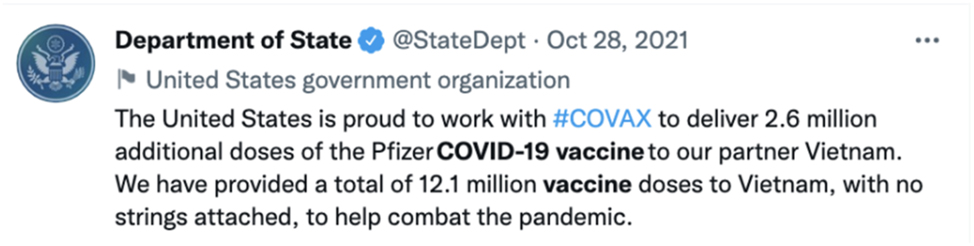

The #NoMore Control of Africa

The most used word from all the collected comments was the hashtag “#NoMore”, which was found in most responses to tweets by @StateDept and was mentioned or repeated 422 times, making 9 percent of all the used words from the collected comments. Figure 2 below shows a selected example of how the hashtag #NoMore was used by different commenters.

Comment 1: No strings attached? Supposed to be a jock? You want something. #NoMore #Africans #AfricaUnite #HandsOffAfrica.

Comment 2: What you put on their shoulder with your stupid vaccine. #NoMore.

Comment 3: COVID-19 has less damage than Americans African policies. #NoMore.

The tweet bearing #NoMore the most. Source: @StateDept Twitter account.

Theme 2:

A conspiracy theory that COVID-19 was created from somewhere, and vaccine production is a business transaction.

The second most used word was “vaccine”, which was mentioned 320 times in all the comments, contributing 6.8 percent of its usage across all the comments. This word was often repeated in comment replies to tweets by @MFA_China, especially those that purportedly informed the public about vaccine production (see Figure 3 below). It’s worth noting that in some instances, these comments may convey a sentiment of skepticism or disagreement with the information provided.

Comment 1: Correction: China provided 750 million doses of vaccine along with COVID-19 to the world.

Comment 2: They don’t work. Covid is not dangerous enough to justify experimental vaccines in the 1st place.

The tweet that attracted more conspiracies. Source: @MFA_China Twitter account.

Theme 3:

Science being impractical for pandemic control, and the geopolitical fight on leading the vaccine campaign.

The third most mentioned word was “China”, which was mentioned 212 times, constituting 4.5 percent of the total comments. Interestingly, a sizable number of mentions did not come out of tweets by @MFA_China but from the other accounts. Figure 4 below shows the exchange of words in that regard.

Comment 1: Start by putting a stop to the funding of Bioweapon labs in China!

Comment 2: China donated 150 K in July, followed by half a million in August. Are my numbers correct, State Dept?

Comment 3: Eighty years ago, the people of Germany described the Jews as demons. They themselves played the role of heroes who saved the Empire. Today, the people of the U.S portray China as a troll. They themselves play heroes who save the world. The ghost of the Nazis never left this planet.

The tweet with the most mention of “China”. Source: @StateDept Twitter account.

Theme 4:

The dismissal of COVID-19 existence, based on speculations that vaccines increase the virus’s spread.

The word “virus” became the fourth most mentioned, with 122 mentions, making 2.6 percent of all the comments. See the below extracts from the comments.

Comment 1: Hopefully no one takes them since they’re not a vaccine and don’t work. The vaccinated are spreading the virus.

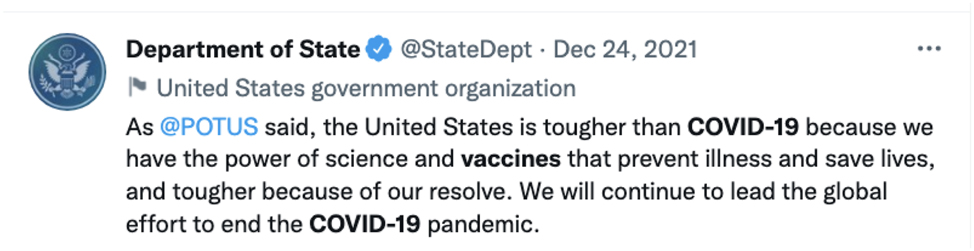

Comment 2: Hiding like cowards from a virus about as deadly as the common flu is NOT the mark of a tough country.

Comment 3: AND MASKING!!!! THE GOAL OF ANY VIRUS (AND LIVING THING) IS TO SURVIVE!! THE VIRUS CAN ONLY MUTATE/SURVIVE IF IT CAN FIND A HOST. MASKING PREVENTS THE VIRUS FROM FINDING A HOST IN YOU. and that includes masking that covers the nose.

Comment 4: Covid 19 is the spreading of a plan. It’s not a virus. Who is behind these fear mongering treasonous tweets? Sars 2 is the suspect virus, completely treatable.

Theme 5:

Vaccines are given as free donations with hidden agendas.

The word free was mentioned 102 times in the comments from different accounts whenever the word ‘free donation’ was mentioned, which contributed to 2.2 percent of all the comments.

Comment 1: Free? Free for whom?

Comment 2: China is one billion doses, of which 600 million are completely free, and 400 million are produced in cooperation with locals.

Comment 3: Nothing is free.

Comment 4: In case you didn’t know this, these jabs are not free. American tax payers are footing the bill.

Comment 5: I think we’re tougher than COVID-19 too. Which is why I think it’s pathetic we’ve completely bowed down to it & have allowed it to run our lives & destroy our freedoms for nearly 2 years… allowing it to limit our movements like cowards. This is NOT the way of the Land of the Free.

To answer RQ3, a connection between RQ1 and RQ2 led to asking the question of how the online relationship among the five Twitter accounts and their audiences’ dialogic communication towards trust in science and vaccine production transpired. From all the collected data, we found that communication was one-way from the tweets to the audience, without any responses from either of the Twitter accounts. By relating to the five principles suggested by Kent and Taylor (1998), we found that messages only came in the form of announcements not to spark any dialogue or provide feedback.

16 Discussion

The main goal of this study was to explore how content and delivery of messages for science, technology, sustainability, and public service on Twitter about vaccine production and distribution were achieved during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how the messages were received by the audience, using three measures of sentiments (negative, neutral and positive), themes and dialogic relationship on five Twitter accounts. There was an overall of 0.5 (neutral sentiment) for all the collected comments, suggesting that there was a balance between negative and positive responses to the tweets. These were made up by the audience commenting with a neutral sentiment on three Twitter accounts for the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom (at 0.5), while on Twitter accounts for China and India, the average sentiments were both positive at 0.6 in which their positivity was also one level above the neutral mark. This suggests that even though the two accounts for China and India had signs of positivity in responses, a lot of negative sentiments from the other accounts diluted them into the cumulative overall neutral sentiment.

The thematic analysis of frequently used words indicates that, despite the explicit focus of tweets on COVID-19 vaccine production and distribution, a significant portion of comments exhibited a disregard for message contexts, forming anti-intellectualist narratives primarily rooted in geopolitical perspectives. Notably, the hashtag #NoMore emerged as a commonly used term, prominently featured in tweets from the United States’ @StateDept account, unrelated to COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control. This hashtag was employed within a framework of superpower-inferiority politics, with some individuals rejecting the notion of vaccine “donations” by the U.S.

The majority of comments utilizing #NoMore constituted an online protest movement within tweets from this account, expressing dissatisfaction with what was perceived as U.S. interference in African affairs. References were made to the Ethiopia-Tigray conflict and internal issues in Uganda (Taye, 2017), albeit without substantial proof accompanying these allegations. A specific tweet from @StateDept, which included the phrase “no strings attached” in announcing the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines to Vietnam, exemplifies a trigger for such attacks. Intriguingly, this donation was unrelated to Africa, yet comments with the #NoMore hashtag suggested a perception of U.S. control over Africa.

Despite the positive nature of the vaccine donation to Vietnam mentioned in the tweet, comments on (@StateDept and @MFA_China accounts) displayed a similar trend, with traces observed on @FCDOGovUK and @IndianDiplomacy, albeit to a lesser extent. It is worth noting that @GermanyDiplo had limited activity, contributing to fewer comments compared to other accounts, with only two tweets posted between March and November 2021. This underscores the subtle nature of this thematic analysis, revealing a complex interplay of geopolitical sentiments and anti-intellectualist narratives across various diplomatic Twitter accounts.

The extended geopolitics that fueled anti-intellectualism toward Twitter users continued to show traces of those believing in conspiracies rather than scientific knowledge, especially where words such as “China” and “virus” were mentioned as shown in the results. For instance, since the outbreak, the “most likely” origin of COVID-19 has sparked debates most of which were not backed by science, but by politics and illogicality. Furthermore, there were two separate (official) reports, the first one being a joint report of international experts led by a WHO team termed Global Study of Origins of SARS-CoV-2: China Part, which conducted a comprehensive trace of medical records from 233 health institutions in the city of Wuhan, where the history of flu-like and acute respiratory illness symptoms to have been registered between October and December 2019 were inspected. The study concluded that in all the 233 cases, there was no scientific evidence linking them to testing “positive” for the virus, although not ruling out the possibility of an additional trace proving otherwise (WHO, 2021). On the other hand, there was an independent report by the United States government through the Office of the Director of National Intelligence titled “Declassified Assessment on COVID-19 Origin.” Therefore, the report ruled out the possibility of the virus being a bioweapon and falsified the narrative that Chinese officials had known about it before its first known outbreak. While the report, also stated that the Intelligence Community (IC) was “divided on the most likely origin of COVID-19” (ODNI, 2021, p. 1), it, however, insists on the likelihood of a laboratory-associated origin at their “moderate confidence” on experiment-based incidents. Looking at the WHO report stated above, and the ODNI, it becomes clear that expert-based knowledge (which is usually scientific, from the WHO’s side) might be contested by other professional bodies who report their findings to the political leadership. Our observation theorizes that these tensions were also exacerbated by misleading media reports about the virus (Zheng et al., 2020), by extension synchronizing a certain degree of anti-intellectualism. With this information publicly available, some of it could influence the thinking behind the coronavirus origins and even strengthen the persisting conspiracies. Before these two reports were made publicly available, both the international media and social media platforms had been receptive to scores of reports from both official journalists and non-journalists suggesting that COVID-19 was a bioweapon, with further utterances by the then-U.S. President, Donald Trump, who on repeated occasions likened the virus to the regular flu and downplayed the scientific methods of dealing with COVID-19 and its spread, undermining expert advice and continually calling it a “Chinese virus” (BBC, 2020; Lee, 2020; Wolfe & Dale, 2020). One incident that reinforces the “downplaying of COVID-19 existence” as shown in the results was one statement from the comments which responded by saying:

I think we’re tougher than COVID-19 too […] allowed it to run our lives & destroy our freedoms […].

Given the extent of such comments, it can be argued that ideological issues always crop up when public emergencies surface. Looking back at the earliest stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, it was evident that partisanship significantly dominated the attitudes, behaviors, and approaches to controlling the spread of the virus (Gadarian et al., 2021).

Concerning relationship-building and providing comprehensive information in their tweets, all the Ministries of Foreign Affairs (MFAs) fell short of offering more scientific details about COVID-19 vaccines, such as their composition, benefits, and side effects. Instead, their communication primarily focused on announcing donations and supply achievements in their quest for efficient dose delivery, potentially leaving the public uninformed and less accepting of vaccine usage and distribution. We argue that many comments stemmed from a lack of knowledge or insufficient explanation, positing that the MFAs’ communication, lacking in dialogic communication principles advocated by Kent & Taylor, particularly the dialogic loop and usefulness of information, cannot be labeled as truly “dialogic.”

Observations indicate a notable absence of feedback or responses to public queries, contrasting with the essence of dialogic communication, which emphasizes two-way engagement, even in online contexts. The MFAs predominantly issued statements without revisiting messages to assess their reception or understanding. This aligns with our hypothesis suggesting that government institutions tend to prioritize advancing political interests and divisions on digital platforms during global crises, neglecting efforts to foster dialogue on the benefits of science and technology and public understanding of such messages. The lack of engagement may contribute to the escalation of anti-intellectualism in pandemic management.

Men et al. (2018) underscore the functional aspect of dialogic communication, emphasizing the necessity for organizations to respond to public questions in the comments section, thereby creating a synergistic dialogic loop. This approach ensures that useful and relevant information is effectively conveyed. However, the observed communication from the MFAs remained one-way, with limited responses to public inquiries. This limitation reinforces the notion that the MFAs missed opportunities to engage in meaningful dialogue, hindering the establishment of a more effective and informed relationship with the public.

17 Conclusions and Recommendations

Amidst the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, a surge in populist views rooted in anti-intellectualism is evident, overshadowing intellectual efforts to promote vaccination as a means to curb the pandemic. Geopolitics, particularly in the global competition for influence and vaccine distribution, plays a significant role in shaping public perceptions regarding the efficacy of science and knowledge in addressing pandemics. The use of Twitter by some Ministries of Foreign Affairs (MFAs) in the pursuit of world domination, both in the context of the pandemic and beyond, can contribute to the propagation of anti-intellectualism irrespective of geographical location.

The results highlight instances where the origin of COVID-19 has been weaponized for political gain, especially in comments, rather than promoting collective global efforts to combat the pandemic. Notably, no official MFA statement on Twitter addressed the COVID-19 origin, although individual accounts ventured into this territory in comments. This contrasts with reports from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. National Intelligence Council, which traced the origin to China and ruled out the virus as a bioweapon, respectively.

The study underscores that the global response to COVID-19 has exacerbated the north-south gap, contributing to the use of digital platforms to amplify anti-intellectualism. The popularization of anti-intellectualist sentiments, particularly viewing science as impractical for pandemic control and prevention, is linked to the lack of transparency and clear communication about vaccine production, patents, and conflicts of interest.

The absence of responses to audience feedback or questions by the Twitter accounts implies a detachment between MFAs and their audience, viewing them merely as information consumers rather than communication partners. Notably, only two Twitter accounts (@MFA_China and @StateDept) dominated the most frequently used words, suggesting that China, as a rising economic powerhouse, and the U.S., a longstanding superpower, attract extensive discourse and academic attention on digital platforms.

While the study falsified the hypothesis suggesting state agencies promoted divisions in their messages, it confirmed the second part, indicating inadequate interaction between Twitter accounts and the public in the comments section, potentially fostering instances of anti-intellectualism.

Given the above findings, we firstly, recommend as a matter of urgency that during pandemics, MFAs should improve on their dialogic communication by timely addressing audience queries online and providing feedback, instead of making their communication only one-way. Secondly, they should involve relevant experts to help them channel their announcements on digital platforms, offering clear and concise scientific information that would help the audience understand the intended message, its purpose, and the rationale behind such announcements. Thirdly, we recommend that the MFAs on their Twitter accounts and digital platforms normalize using algorithmic tools that would help them frequently evaluate the effect of their messages to the public as a way of improving their communication approaches and engaging in relationship-building.

18 Limitations of the Study and Future Research

A major limitation was the gathering of data from all the Twitter accounts as it was done manually, where some of the comments were marked sensitive and even appeared to be hidden or deleted. Lack of access to such comments heavily affected the researchers’ inferences on the full-scale discourses made about the extent of anti-intellectualism towards COVID-19 vaccines, fueled by the intensified race on the production and delivery of vaccines by all the countries mentioned above. The second limitation was that since the researchers only focused on analyzing textual discourses from the comments section, some of the comments used pictures to advance their discourses, which made it a challenge to include them within the scope of our investigation. Therefore, future studies could combine both textual and pictorial analysis to ensure inclusivity in the analysis of comments.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Andersson, E., Dryden, C., & Variawa, C. (2018). Methods of applying machine learning to student feedback through clustering and sentiment analysis. Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.24908/pceea.v0i0.13059 Search in Google Scholar

Arun, C. (2018). Making choices: Social media platforms and freedom of expression norms. Regardless of Frontiers. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3411878 Search in Google Scholar

Bajaj, S. S., Maki, L., & Stanford, F. C. (2022). Vaccine apartheid: Global cooperation and equity. The Lancet, 399(10334), 1452–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00328-2 Search in Google Scholar

BBC. (2020, June 24). President Trump calls coronavirus “Kung Flu”. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-us-canada-53173436 Search in Google Scholar

Braun, J., & Gillespie, T. (2011). Hosting the public discourse, hosting the public: When online news and social media converge. Journalism Practice, 5(4), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2011.557560 Search in Google Scholar

Chagla, Z., & Pai, M. (2021). COVID-19 boosters in rich nations will delay vaccines for all. Nature Medicine, 27(10), 1659–1660. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01494-4 Search in Google Scholar

Chhabra, R. (2020). Twitter diplomacy: A brief analysis. https://www.orfonline.org/research/twitter-diplomacy-a-brief-analysis-60462/#_ftnref1 Search in Google Scholar

Ciotti, M., Ciccozzi, M., Terrinoni, A., Jiang, W.-C., Wang, C.-B., & Bernardini, S. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 57(6), 365–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2020.1783198 Search in Google Scholar

Clark, J., & Horton, R. (2019). A coming of age for gender in global health. The Lancet, 393(10189), 2367–2369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30986-9 Search in Google Scholar

Cross, R. D. (1990). The historical development of antiintellectualism in American society: Implications for the schooling of African Americans. The Journal of Negro Education, 59(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/2295289 Search in Google Scholar

de Bengy Puyvallée, A., & Storeng, K. T. (2022). COVAX, vaccine donations and the politics of global vaccine inequity. Globalization and Health, 18(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-022-00801-z Search in Google Scholar

Ditlhokwa, G. (2022). Health information and social inclusion of women during COVID-19: Exploring Botswana television’s functionalist communication strategy. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 12(3), e202219. https://doi.org/10.30935/ojcmt/1216 Search in Google Scholar

Duncombe, C. (2017). Twitter and transformative diplomacy: Social media and Iran–US relations. International Affairs, 93(3), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix048 Search in Google Scholar

Gadarian, S. K., Goodman, S. W., & Pepinsky, T. B. (2021). Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One, 16(4), e0249596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249596 Search in Google Scholar

Gelb, A., & Mukherjee, A. (2021). A COVID vaccine certificate building on lessons from digital ID for the digital yellow card. Center for Global Development.Search in Google Scholar

Geurkink, B., Zaslove, A., Sluiter, R., & Jacobs, K. (2019). Populist attitudes, political trust, and external political efficacy: Old wine in new bottles? Political Studies, 68(1), 003232171984276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719842768 Search in Google Scholar

Gozum, I. E., Capulong, H. G., Gopez, J. M., & Galang, J. R. (2021). Culture, religion and the state: Towards a multidisciplinary approach to ensuring public health during the COVID-19 pandemic (and beyond). Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 14, 3395–3401. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S318716 Search in Google Scholar

Hancu-Budui, A., Zorio-Grima, A., & Blanco-Vega, J. (2020). Audit institutions in the European Union: Public service promotion, environmental engagement and COVID crisis communication through social media. Sustainability, 12(23), 9816. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239816 Search in Google Scholar

Hassan, F., London, L., & Gonsalves, G. (2021). Unequal global vaccine coverage is at the heart of the current covid-19 crisis. BMJ, 375, n3074. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n3074 Search in Google Scholar

Howley, A., Pendarvis, E. D., & Howley, C. B. (1993). Anti-intellectualism in US schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 1, 6. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v1n6.1993 Search in Google Scholar

Islam, M. S., Kamal, A.-H. M., Kabir, A., Southern, D. L., Khan, S. H., Hasan, S. M. M., Sarkar, T., Sharmin, S., Das, S., Roy, T., Harun, M. G. D., Chughtai, A. A., Homaira, N., & Seale, H. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS One, 16(5), e0251605. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251605 Search in Google Scholar

Kent, M. L., & Taylor, M. (1998). Building dialogic relationships through the world wide web. Public Relations Review, 24(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(99)80143-X Search in Google Scholar

Kickbusch, I. (2016). Global health governance challenges 2016 – are we ready? International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 5(6), 349–353. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2016.27 Search in Google Scholar

Kim, J. H., Marks, F., & Clemens, J. D. (2021). Looking beyond COVID-19 vaccine phase 3 trials. Nature Medicine, 27(2), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01230-y Search in Google Scholar

Lal, A., Erondu, N. A., Heymann, D. L., Gitahi, G., & Yates, R. (2021). Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: Rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. The Lancet, 397(10268), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32228-5 Search in Google Scholar

Lavazza, A., & Farina, M. (2020). The role of experts in the covid-19 pandemic and the limits of their epistemic authority in democracy. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 356. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00356 Search in Google Scholar

Lee, B. Y. (2020, June 24). Trump once again calls covid-19 coronavirus the ‘Kung Flu’. Retrieved May 30, 2022, from Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2020/06/24/trump-once-again-calls-covid-19-coronavirus-the-kung-flu/?sh=674edfab1f59 Search in Google Scholar

Lee, T.-L. (2021). COVID-19 vaccination certificates and their geopolitical discontents. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 12(2), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2021.33 Search in Google Scholar

Men, L. R., Tsai, W. H. S., Chen, Z. F., & Ji, Y. G. (2018). Social presence and digital dialogic communication: Engagement lessons from top social CEOs. Journal of Public Relations Research, 30(3), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2018.1498341 Search in Google Scholar

Merkley, E. (2020). Anti-intellectualism, populism, and motivated resistance to expert consensus. Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(1), 24–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz053 Search in Google Scholar

Merkley, E., & Loewen, P. J. (2021). Anti-intellectualism and the mass public’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(6), 706–715. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01112-w Search in Google Scholar

Morelock, J., & Narita, F. Z. (2022). The Nexus of QAnon and COVID-19: Legitimation crisis and epistemic crisis. Critical Sociology, 48(6), 1005–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/08969205211069614 Search in Google Scholar

Motta, M. (2018). The dynamics and political implications of anti-intellectualism in the United States. American Politics Research, 46(3), 465–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X17719507 Search in Google Scholar

ODNI. (2021, October 21). Declassified assessment on COVID-19 origins. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/Declassified-Assessment-on-COVID-19-Origins.pd Search in Google Scholar

Osborne, S. P., Powell, M., Cui, T., & Strokosch, K. (2022). Value creation in the public service ecosystem: An integrative framework. Public Administration Review, puar. 82(4), 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13474 Search in Google Scholar

Peters, M. A. (2019). Anti-intellectualism is a virus. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 51(4), 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2018.1462946 Search in Google Scholar

Powell, R. A., Mwangi-Powell, F. N., Radbruch, L., Yamey, G., Krakauer, E. L., Spence, D., Ali, Z., Baxter, S., De Lima, L., Xhixha, A., Rajagopal, M. R., & Knaul, F. (2015). Putting palliative care on the global health agenda. The Lancet Oncology, 16(2), 131–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70002-1 Search in Google Scholar

Reyes, A. (2020). I, Trump: The cult of personality, anti-intellectualism and the Post-Truth era. Journal of Language and Politics, 19(6), 869–892. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.20002.rey Search in Google Scholar

Rigney, D. (1991). Three kinds of anti-intellectualism: Rethinking Hofstadter. Sociological Inquiry, 61(4), 434–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1991.tb00172.x.Search in Google Scholar

Ruggeri, A., & Samoggia, A. (2018). Twitter communication of agri-food chain actors on palm oil environmental, socio-economic, and health sustainability. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 17(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1699 Search in Google Scholar

Rybalko, S., & Seltzer, T. (2010). Dialogic communication in 140 characters or less: How fortune 500 companies engage stakeholders using Twitter. Public Relations Review, 36(4), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.08.004 Search in Google Scholar

Shogan, C. J. (2007). Anti-intellectualism in the modern presidency: A republican populism. Perspectives on Politics, 5(2), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1017/s153759270707079x Search in Google Scholar

Sommerfeldt, E. J., & Yang, A. (2018). Notes on a dialogue: Twenty years of digital dialogic communication research in public relations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 30(3), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2018.1498248 Search in Google Scholar

Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Li, X., Bennett, B., Šegalo, S., Abbas, J., Cheshmehzangi, A., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine donations – vaccine empathy or vaccine diplomacy? A narrative literature review. Vaccines, 9(9), 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9091024 Search in Google Scholar

Taye, B. A. (2017). Ethnic federalism and conflict in Ethiopia. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 17(2), 41–66.Search in Google Scholar

Thange, U., Shukla, V. K., Punhani, R., & Grobbelaar, W. (2021). Analyzing COVID-19 data set through data mining tool “orange”. In 2021 2nd international conference on computation, automation and knowledge management (ICCAKM) (pp. 198–203).10.1109/ICCAKM50778.2021.9357754Search in Google Scholar

Ting, R. S., Yong, Y. A., Tan, M., & Yap, C. (2021). Cultural responses to covid-19 pandemic: Religions, illness perception, and perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.634863 Search in Google Scholar

Vese, D. (2021). Governing fake news: The regulation of social media and the right to freedom of expression in the era of emergency. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 13(3), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2021.48 Search in Google Scholar

Voo, T. C., Smith, M. J., Mastroleo, I., & Dawson, A. (2022). COVID-19 vaccination certificates and lifting public health and social measures: Ethical considerations. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 28(6), 454–458. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.22.023 Search in Google Scholar

WHO. (2021, 14 January–10 February). WHO-Convened global study of origins of SARS-CoV-2: China part. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/origins-of-the-virus Search in Google Scholar

Wolfe, D., & Dale, D. (2020, October 31). ‘It’s going to disappear’: A timeline of Trump’s claims that Covid-19 will vanish. Retrieved from CNN: https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2020/10/politics/covid-disappearing-trump-comment-tracker/ Search in Google Scholar

Wood, S., & Schulman, K. (2021). Beyond politics – promoting Covid-19 vaccination in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(7), e23. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmms2033790 Search in Google Scholar

Yang, S.-U., Kang, M., & Johnson, P. (2010). Effects of narratives, openness to dialogic communication, and credibility on engagement in crisis communication through organizational blogs. Communication Research, 37(4), 473–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650210362682 Search in Google Scholar

Yu, M., Yang, C., & Li, Y. (2018). Big data in natural disaster management: A review. Geosciences, 8(5), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8050165 Search in Google Scholar

Zheng, Y., Goh, E., & Wen, J. (2020). The effects of misleading media reports about COVID-19 on Chinese tourists’ mental health: A perspective article. Anatolia, 31(2), 337–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1747208 Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Interview

- Roundtable Discussion of Emerging Technology Companies and Transcultural Challenges

- Research Articles

- Regulating Dominant Platforms: Challenges and Opportunities of Content Moderation on Jio Platforms

- A Transcultural Interpretation of Key Concepts in China-US Relations: Hegemony, Democracy, Individualism and Collectivism

- Postcolonial Analysis of Transcultural News Frames: A Case Study of Facebook Rebranding

- Win-Loss-Win in the US–China Game: A Cross-cultural Analysis of a TV Anchor Debate Between Trish Regan and Liu Xin

- I am in the Homeless Home or I Am Always on the Way Home: Formatting Identity and Transcultural Adaptation Through Ethnic and Host Communication

- The Multi-discourse Fight of COVID-19 Vaccine in the World of Digital Platforms: Rethinking Popularity of Anti-intellectualism

- A Virtual Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy: Online Exchanges of Emic Asian Cultural Concepts

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Interview

- Roundtable Discussion of Emerging Technology Companies and Transcultural Challenges

- Research Articles

- Regulating Dominant Platforms: Challenges and Opportunities of Content Moderation on Jio Platforms

- A Transcultural Interpretation of Key Concepts in China-US Relations: Hegemony, Democracy, Individualism and Collectivism

- Postcolonial Analysis of Transcultural News Frames: A Case Study of Facebook Rebranding

- Win-Loss-Win in the US–China Game: A Cross-cultural Analysis of a TV Anchor Debate Between Trish Regan and Liu Xin

- I am in the Homeless Home or I Am Always on the Way Home: Formatting Identity and Transcultural Adaptation Through Ethnic and Host Communication

- The Multi-discourse Fight of COVID-19 Vaccine in the World of Digital Platforms: Rethinking Popularity of Anti-intellectualism

- A Virtual Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy: Online Exchanges of Emic Asian Cultural Concepts