Abstract

We present initial exploratory work on illuminating the long-standing question of areal versus genealogical connections in South Asia using computational data visualization tools. With respect to genealogy, we focus on the subclassification of Indo-Aryan, the most ubiquitous language family of South Asia. The intent here is methodological: we explore computational methods for visualizing large datasets of linguistic features, in our case 63 features from 200 languages representing four language families of South Asia, coming out of a digitized version of Grierson’s Linguistic Survey of India. To this dataset we apply phylogenetic software originally developed in the context of computational biology for clustering the languages and displaying the clusters in the form of networks. We further explore multiple correspondence analysis as a way of illustrating how linguistic feature bundles correlate with extrinsically defined groupings of languages (genealogical and geographical). Finally, map visualization of combinations of linguistic features and language genealogy is suggested as an aid in distinguishing genealogical and areal features. On the whole, our results are in line with the conclusions of earlier studies: Areality and genealogy are strongly intertwined in South Asia, the traditional lower-level subclassification of Indo-Aryan is largely upheld, and there is a clearly discernible areal east–west divide cutting across language families.

1 Introduction

South Asia[1] is the home of hundreds of languages spoken by almost two billion people – more than a quarter of the world’s population. According to both Ethnologue (Simons and Fennig 2018) and Glottolog (Hammarström et al. 2019), this region is home to well over 600 languages.[2] Most of these languages are from four major language families (Indo-European > Indo-Aryan, Iranian, and Nuristani; Dravidian; Austroasiatic > Munda, Khasian, and Nicobaric; and Sino-Tibetan > Tibeto-Burman; see Figure 1).[3] In addition there are some language isolates and small families (Georg 2017) and several creoles and pidgins.

South Asian language families (source: Wikimedia Commons).

There is a long history of multilingualism, expansions and contractions of language communities, and shifting patterns of sociolinguistic dominance in the region. Naturally, this complex linguistic situation gives rise to a multitude of intricate descriptive problems. In this article, we will focus on two closely interconnected long-standing descriptive problems with regard to the linguistic situation in South Asia, viz. the question of South Asia as a linguistic area, and the subclassification of the IA languages.

The larger context of the work presented here is a research project with the aim of investigating the various areality claims found in the literature about South Asia as a whole and also about regions in South Asia. The language data for this investigation are taken primarily out of a digitized version of the Linguistic Survey of India (LSI; Grierson 1903–1927; see Section 4). The project has both a linguistic and a computational-linguistic aspect. The main thrust of the latter has been on developing text-mining methods for extracting information about linguistic features from the free text of descriptive grammar sketches such as those found in LSI (Borin et al. 2018; Malm et al. 2018; Virk et al. 2017).

However, we have also used the computational expertise available in the project to devise suitable data visualization tools allowing linguists to work with very large amounts of language data (see Section 6). The tools themselves are not new – they are built using tried-and-true computational components – but they represent a growing trend in linguistics and other humanities disciplines towards combining computer-assisted “distant reading” (Moretti 2013) of large datasets with traditional attention to detail, and here we would like to share our experiences of this methodology with the community.

The two questions mentioned above are very much interconnected. Of the major language families of South Asia, IA plays a unique role in the linguistic landscape of the region. It is largely confined to South Asia (as opposed to, e.g. TB, which is represented by many languages in the region, but which still make up only about half of all TB languages). It is present almost everywhere in the region (as opposed to DR, which is also confined to South Asia, but by and large restricted to the south of the subcontinent). It is present typically in the form of a dominant rather than a dominated language (a status that it has enjoyed for millennia at least in large parts of the region). And it has the longest documented history among the South Asian language families; so that the migration paths of IA-speaking communities and how IA languages have spread from the time when IA speakers first arrived in South Asia – perhaps about 1500 BCE – are known at least in broad outline. This means that it is very important to correlate what we know about the subclassification of IA with our observations about the distribution of putative South Asian areal linguistic traits.

Here we present the results of a large-scale comparative study, using data visualization tools, of 200 South Asian linguistic varieties concerning 63 linguistic features to examine their genetic and areal subgrouping, mainly based on the data provided in LSI.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: in the next two sections (Sections 2 and 3) we provide some background to the two questions that we set out to illuminate in our work, i.e. whether South Asia (or parts of it) forms a linguistic area, and whether we can add something to the vexed question of IA subgrouping. In Section 4 we briefly present our data source, LSI, and in Section 5 we describe in more detail how the linguistic features that we use for our investigation have been collected from LSI.

Given that our dataset is extensive, our approach to these questions is based on applying an e-science methodology, i.e. large-scale computer visualization of the data. The rationale for doing this is laid out in Section 6, and in the subsequent sections we also describe and present results from the three kinds of data visualization tools that we have applied to our dataset, phylogenetic software (Section 7), multiple correspondence analysis (Section 8), and map visualization (Section 9).

The work presented here is exploratory and very much in its initial stages, so the results are tentative and more likely to raise more new questions than answer old ones.

2 South Asia: a linguistic area?

As described above, South Asia is the home of hundreds of languages from several unrelated language families, and is further characterized by a long history of multilingualism and sociolinguistically complex communities. According to some scholars, this has made the languages of this region more similar to each other in some respects than they are to genetically related languages spoken outside this region, i.e. South Asia forms a linguistic area (e.g. Emeneau 1956; Kachru et al. 2008; Masica 1976). The notion of linguistic area (“Sprachbund”) was introduced by Trubetzkoy (1930), but there is still no general consensus on its validity, its definition, or the criteria for defining a linguistic area. Generally, the term is understood to refer to a region where, due to close contact and widespread multilingualism, languages have influenced one another to the extent that both genetically related and unrelated languages are more similar on many linguistic levels than we would expect, and also ideally that the languages involved tend not to share the area-defining features with genetically related languages outside the area.

There is some disagreement about whether South Asia should be considered a linguistic area, and if so, what its defining features are, as well as the origin of the features. Hock (2001) suggests internal developments as the source of these features in IA, instead of language contact, while Kuiper (1967) assumes a prehistoric DR substratum, whereas Witzel (1999) suggests a Munda substratum.

However, internal development does not necessarily contradict the idea of a linguistic area. For example, Southeast Asian languages developing tone usually do so by internal regular sound changes, e.g. loss of voicing leading to phonemicization of erstwhile allophonic pitch differences, but this still has the effect of aligning them with the area and is presumably motivated by this alignment (Kirby and Brunelle 2017).

Masica (1976) presents the most detailed study to date, attempting to determine the extent of geographical and language-family overlap in the proposed areal features. Hook (1987) is also a good attempt to do a fine-grained investigation, examining the geographical distribution of subordinate clause types in northwestern South Asian languages (13 in total; IA and DR). However, most studies are largely impressionistic (see Ebert 2006 for a critique), presenting random examples from a convenience sample of primarily major IA or DR languages (e.g. Emeneau 1956, 1980; Gair 2012; Southworth 1974; Subbarao 2008). Such studies give the impression that a feature is homogenously spread over the whole region (see Sridhar 2008 for a critique). Both Hook (1987) and Masica (1976, 1991 emphasize the need for a more detailed, large-scale study. Recent publications such as Peterson (2017) are welcome additions.

More detailed linguistic comparisons have generally been done within families only, e.g. Turner (1966), Bloch (1954), Cardona and Jain (2003) on IA, Burrow and Emeneau (1984), Steever (2016), Krishnamurti (2003) on DR, Matisoff (2003), and Thurgood and LaPolla (2017) on ST. This is not surprising, as doing the comparative work manually puts severe restrictions on how many languages and linguistic features can be included in a study. Further, the validity of the current internal sub-groupings of IA and TB is questioned by Asher (2008) and Matisoff (2003). This question cannot be resolved without areal cross-family studies. Consequently, we expect that a large-scale study such as that presented here should be able to both throw light on the areal hypothesis and contribute to our understanding of the internal structure of the major South Asian language families.

3 The Indo-Aryan language family and its subclassification

Indo-Aryan is a major subbranch of the Indo-Iranian branch of Indo-European, forming the easternmost extant subgroup within the Indo-European language family, and it is also the dominant language family in South Asia. IA languages are spoken throughout the whole of South Asia, and any investigation of areal relationships in the region needs to take into account the genealogical relationships internal to this family.

The modern IA languages[4] (200-plus languages with over 1.2 billion speakers according to the Ethnologue) are found today in northern India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Generally speaking NIA languages are found in four geographical regions: (1) northwestern (e.g. Sindhi, Punjabi, Lahnda, various Pahari varieties, Dogri, Kashmiri); (2) southwestern (e.g. Gujarati, Marathi, Konkani, Dhivehi (Maldivian) and Sinhala); (3) the midlands (Central) IA group (Hindi-Urdu and its various dialects including Eastern and Western Hindi and their dialects), also known as the Hindi belt (Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi and Madhya Pradesh); and (4) eastern (e.g. Bengali, Assamese, Oriya).

The first recorded IA linguistic material (Vedic hymns) is from about 1500 BCE. It is generally believed that IA arrived in South Asia through the mountainous regions of Afghanistan and Pakistan and the plains of Pakistan, moving eastwards and southwards over the millennia. During the initial stages, the center of IA was the Upper Indus valley (present-day Pakistan), and later – towards the end of the Vedic period – the Gangetic plains of north India. By the 6th century BCE IA had spread throughout the whole of north India (north of the Vindhya mountain range and the Narmada river), displacing the original languages (Dravidian, Austroasiatic, and languages of unknown stock; see Witzel 1999 for a review of substrate evidence). This trend continued over the next millennium and a half when IA continued spreading towards the south, including the regions south of the Narmada river where Marathi and Oriya are spoken today. The presence of IA in Sri Lanka (Sinhalese), the Maldives (Dhivehi), and Tajikistan (Parya) is due to pre-modern migrations of IA speakers outside the mainland core IA regions (Masica 1991).

The earliest signs of dialectal variation within IA languages are attested in the texts from the Ashokan period (3rd century BCE). The texts exemplify early MIA and their language is generally known as “inscriptional Prakrit”. Based on the linguistic innovations noted in these texts, Bloch (1950) identified three main geographical MIA dialect areas: (1) the Eastern dialect; (2) the Northwestern dialect; and (3) the Southwestern dialect. Southworth (2005) revised this division and reclassified them into two groups: (a) the Northwestern dialect and (b) the Eastern and Southwestern dialect. This dialectal division of Early and Middle MIA has implications for subgrouping of modern NIA languages.

Hoernle’s (1880) classification assumes a two-way division in ancient times, which suggests closer affinity between NIA Southern and Eastern languages:

Southern-Eastern branch (which grouped Marathi with Bengali, Oriya, and Eastern Hindi); and

Northwestern branch (grouping Western Hindi and Nepali with Punjabi, Sindhi, and Gujarati).

Hoernle’s hypothesis was later refined by Grierson, who proposed the Inner-Outer group hypothesis. Grierson’s (original) proposal builds on his hypothesis involving two separate waves of migrations: One led to the settlement of northern India. Western Hindi and its dialects – the “Inner” group – emerged from there. The second, encircling wave resulted in the “Outer” group of IA languages. Grierson suggests, further, that Northwestern languages such as Sindhi and Lahnda are closer to Eastern/Southwestern languages than to Western Hindi. In Grierson’s revised proposal, there is an “Intermediate branch”, in addition to the Inner and Outer branches.

Grierson’s criteria, and indeed the entire Inner-Outer hypothesis, were severely criticized by Chatterji (1926), according to whom Grierson had in some cases inaccurately represented the geographical distribution of features and in others was describing changes of relatively recent origin or cases of independent development. He proposed instead the east-west hypothesis, which divides the Central IA languages into two groups: the Eastern and Western subgroups. The criterion which Chatterji used as the basis of his suggestion was the presence/absence of a conjugated past tense.

But as we will see below, an east–west division is not only relevant for IA languages, but also to some extent for other language families, where, as has been pointed out frequently in the literature, subclassification of language families in South Asia coincides with their geographical divisions. In and of itself this is not an argument against the genetic classification, unless of course the classification relies too heavily on geographical factors. This highlights the need for further systematic studies to tease out the genetic classification from similarities due to contact.

Masica (1991) describes in some detail the incompatible classifications implicitly or explicitly provided by Chatterji (1926), Katre (1968), Cardona (1974), Nigam (1972), and Turner (1975), and comes to the conclusion that:

Perhaps a wiser course would be to recognize a number of overlapping genetic zones, each defined by specific criteria […]. We might therefore be well-advised to give up as vain the quest for a final and “correct” NIA historical taxonomy, which no amount of tinkering can achieve, and concentrate instead on working out the history of various features (Masica 1991: 460).

While this is a sensible note of caution against striving for a sharp, Stammbaum-like classification, Southworth’s revival of Grierson’s original construal of IA regional divisions deserves mention here. Southworth (2005: 135–146) introduces linguistic evidence overlooked by Grierson and later scholars to provide support for a Griersonian view of dialect division. Zoller (2016) comes out in support of Southworth’s position, although at the same time he largely rejects Southworth’s evidence. Cathcart (2020) presents a computational study aiming to throw light on this question. Using a Bayesian framework, he finds weak evidence for the Inner-Outer dichotomy among 33 IA varieties for which sound changes (of the form “(OIA) C A D > (NIA) C B D”) can be extracted from Turner (1966), but also notes that his contribution represents a mere beginning which could be extended and refined in more than one interesting direction.

Many of the classifications of IA presented in the literature seem to have in common that they are based on one or a small number of putative diagnostic innovations (structural features or lexical items). Further, they also take into consideration partly different linguistic features. Consequently, the internal subgrouping of modern IA is still unresolved. Masica notes (1991: 446) that there are “few internal natural barriers”, and that political instability has not resulted in separate linguistic units; rather NIA displays dialect continua, without sharp boundaries separating mutually unintelligible languages.

At the same time, there are still broad geographical divisions which correspond to the general classification of modern IA languages:[5]

Central (or North-Central): e.g. (Western) Hindi with its enormous range of dialectal variants and Nepali (LSI vol. 9)

Northwestern: e.g. Sindhi, Lahnda (LSI vol. 8), Punjabi (LSI vol. 9)

Western: e.g. Rajasthani and Gujarati (LSI vol. 9)

Southern: e.g. Marathi and Konkani (LSI vol. 7), and also Sinhala and Dhivehi, which represent fairly late migrations out of the mainland Southern language area

Eastern: e.g. Bengali, Oriya, Assamese (LSI vol. 5) and Eastern Hindi (LSI vol. 6)

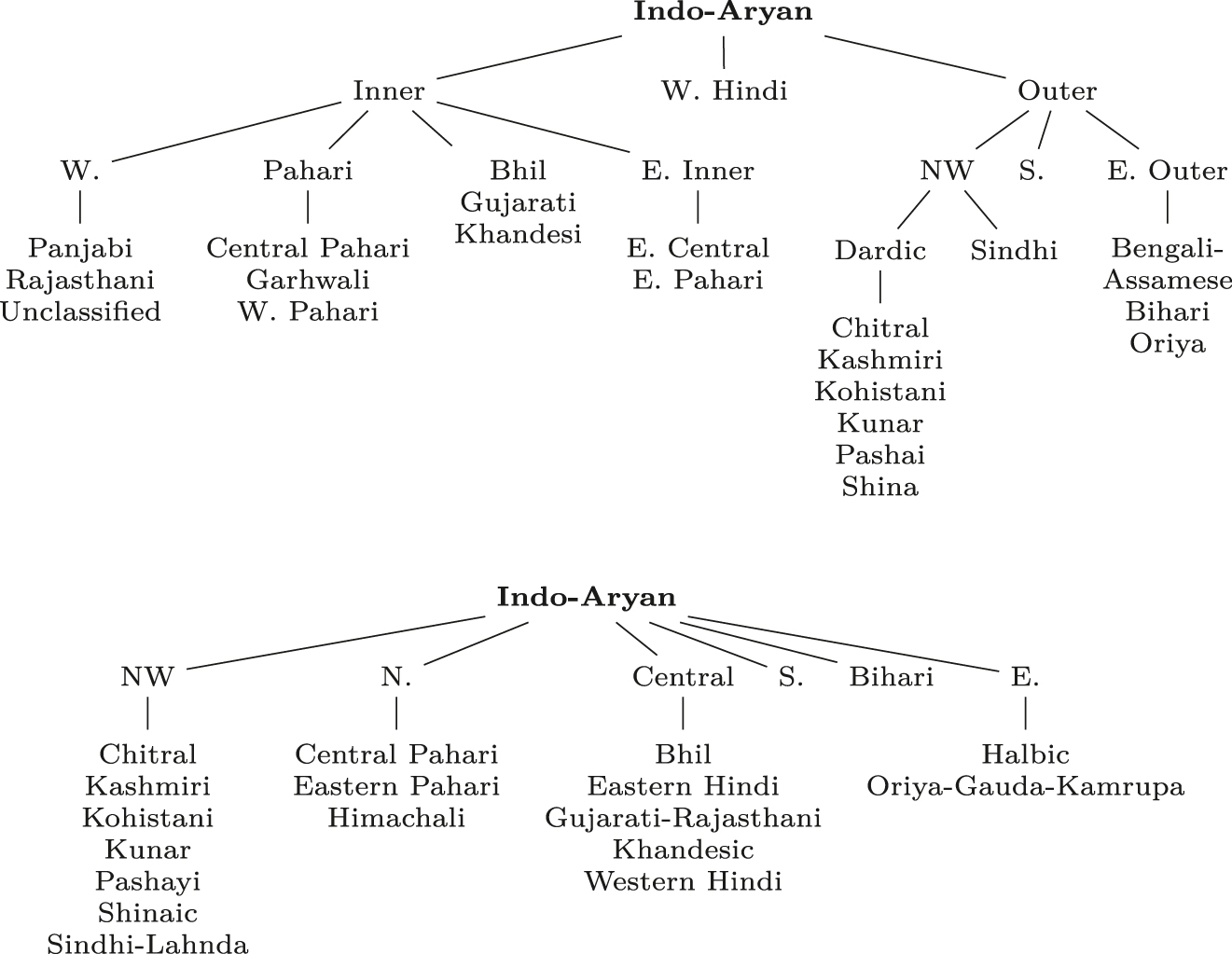

Given these complications, we have decided to work with two current genealogical classifications of the IA languages, reflecting two divergent but largely compatible traditions. Ethnologue (Simons and Fennig 2018) follows essentially Grierson’s classification, with its division into Inner and Outer languages as two primary branches. Glottolog (Hammarström et al. 2019) is based on Masica (1991), though providing a strict family tree representation. Figure 2 reproduces the two classifications in so far as they are relevant to languages included in LSI, with minor changes to terminology. It should be noted that both classifications agree that Nuristani is a primary branch of Indo-Iranian separate from IA.

Ethnologue (top) and Glottolog (bottom) classification of IA (partial).

The main differences and similarities between the two classifications are set out in tabular form in Tables 1 and 2.

Comparison of higher-level Ethnologue and Glottolog groupings.

|

Comparison of lower-level Ethnologue and Glottolog groupings.

| Ethnologue | Glottolog | LSI | Language(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitral | Chitral | 8 | Kalasha, Khowar |

| Pashai | Pashayi | 8 | Southeast Pashai |

| Kunar | Kunar | 8 | Gawar-Bati |

| Kohistani | Kohistani | 8 | Indus Kohistani, Kalami, Torwali |

| Shina | Shinaic | 8 | Dras, Gilgiti, Gurezi, Shina-Dras |

| Kashmiri | Kashmiri | 8 | Kashmiri, Kishtawari, Poguli, Rambani, |

| Siraji of Doda | |||

| Sindhi | Sindhi-Lahnda | 8 | Kacchi, Lari, Lasi, Sindhi |

| Panjabi | 9 | Punjabi | |

| 8 | Chibali, Northern Hindko-Awankari, | ||

| Northern Hindko-Dera Ghazi Khan, | |||

| Northern Hindko-Dhanni, Northern, | |||

| Hindko-Kohat, Peshawar Hindko, | |||

| Porthwari, Saraiki-Multan, | |||

| Thali-Derawal, Tinoli Hindko, Western | |||

| Punjabi-01, Western Punjabi-Salt | |||

| Range | |||

| Central Pahari | Central Pahari | 9 | Khaspariya, Kumaoni |

| Garhwali | 9 | Badhani, Garhwali, Rathi, Tehri | |

| W. Pahari | Himachali | 9 | Bhadrawahi, Bhagati, Chambeali, |

| Churahi, Dogri, Gaddi, Giripari, Inner | |||

| Siraji, Jaunsari, Kangri, Kiunthali, | |||

| Kullu Pahari, Kului, Mandeali, Outer | |||

| Siraji, Padari, Pangwali, Shimla Siraji, | |||

| Sodochi | |||

| Gujarati | Gujarati-Rajasthani | 9 | Charotari, Gujarati, Patani Gujarati |

| W. Unclassified | 9 | Ahirwati, Mewati | |

| Rajasthani | 9 | Dhundari, Marwari-02 (India), Ajiri of | |

| Hazara, Bagri, Eastern Gujuri, Western | |||

| Gujuri | |||

| Bhil | 9 | Malvi, Nimadi | |

| Bhil | 9 | Mawchi, Rathwi Bareli-01, Siyalgir, | |

| Bhili-Mahi Kantha | |||

| Khandesi | Khandesic | 9 | Khandesi |

| W. Hindi | W. Hindi | 9 | Bundeli |

| 8 | Dakhini, Hindi, Braj Bhasha, Kanauji | ||

| E. Central | E. Hindi | 6 | Awadhi, Chhatisgarhi |

| Southern | Southern | 7 | Marathi, Chitpavani, Goan Konkani, |

| Konkani-Thana, Kudali, Sarasvat | |||

| Brahmin, Marathi-Pune, | |||

| Varhadi-Nagpuri-01 | |||

| Bihari | Bihari | 5 | Bhojpuri-Shahabad, Eastern Magahi, |

| Magahi-Gaya, Panchpargania, Sadri-02, | |||

| Southern Standard Maithili, Standard | |||

| Maithili, Western Standard | |||

| Bhojpuri-Purbi | |||

| Bengali-Assamese | Halbic | 5 | Halbi |

| Oriya-Gauda-Kamrupa | 5 | Assamese, Bengali, Eastern Malda, | |

| Hajong, Kharia Thar, Mayang, | |||

| Rajbangsi, Sylheti | |||

| Oriya | 5 | Odia-Cuttack | |

| E. Pahari | E. Pahari | 9 | Nepali |

Table 1 shows correspondences at the higher level, though omitting Ethnologue’s primary branching of Inner versus Outer. Ethnologue has a deeper tree, with four taxonomical levels above that of individual languages, against only two levels in Glottolog. The granularities are comparable: Ethnologue’s secondary level has seven subdivisions against six in Glottolog’s primary level.

Simplifying things considerably, we could think of a genealogical classification of a language family as defining an ordering among the language varieties making up the family, based on some ideal distance measure from an imaginary point of origin. If we also assume that there will be no ties, this will define a total linear ordering of the family’s languages (and subgroups). From Table 1 we see that if we disregard the major Inner–Outer branching of Ethnologue, then at the level of granularity shown in the table, Ethnologue and Glottolog on the whole define the same ordering: in general, it is possible to represent the correspondences between the groupings in each of the two classifications as continuous segments of Table 1, with the exception of the last row, since the remainder of Glottolog’s Northern is completely included in Ethnologue’s Western. The differences between the two classifications lie mostly in where boundaries are drawn and the labels assigned to subgroups. When we refer to the “traditional” classification of IA here, this means at least an ordering and at best a subgrouping which can be made to agree with either Ethnologue or Glottolog (or both).

Table 2 shows a comparative classification of lower-level groupings (the Ethnologue quaternary and Glottolog secondary levels), including the list of individual varieties included in LSI and the volume number within LSI.

4 Grierson’s Linguistic Survey of India

The linguistic richness and diversity of South Asia were documented by the British Indian administration in a large-scale survey conducted in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century under the supervision of Sir George Abraham Grierson and Sten Konow.[6] The survey resulted in a detailed report comprising 11 volumes in 19 parts, around 9,500 pages in total, entitled Linguistic Survey of India (LSI; Grierson 1903–1927). The survey covered 723 linguistic varieties representing the major language families of the region and some unclassified languages, of almost the whole of nineteenth-century British-controlled India (modern Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and parts of Myanmar). For each major variety it provides (1) a grammar sketch (including a description of the sound system); (2) a core word list; and (3) text specimens (including a morpheme-glossed translation of the Parable of the Prodigal Son).

The LSI grammar sketches provide basic grammatical information about the languages in a fairly standardized format. The focus is on the sound system and the morphology (nominal number and case inflection, verbal tense, aspect, and argument indexing inflection, etc.), but there is also some syntactic information to be found in them. They range in length from less than a page to over eighty pages, and the whole LSI comprises far too much text for it to be a realistic option to process it manually. Thus, we are now turning the linguistic data found in LSI into a structured linguistic database which we hope will be useful for many different kinds of linguistic investigations.

The language data for the LSI grammar sketches were collected around 1900, hence obviously reflecting the state of these languages of over a century ago. However, we know that both many grammatical characteristics (in particular inflectional morphology) and the core vocabulary of a language are quite resistant to change (Nichols 2003). In order to get an understanding of the usefulness of LSI for our purposes, we sampled information from a few of the grammar sketches in order to assess how well LSI data reflect modern language usage. Our results show that while some of the lexical items are not used today in everyday speech, most other information is still valid for the modern languages. Despite its age, LSI still remains the most complete single source on South Asian languages. It has been used in a few studies with varying aims and objectives. Specifically, there have been some attempts to use LSI in areal studies (e.g. Hook 1977; Southworth 1974), but because of the manual nature of these studies, the information in LSI was used only to a very limited extent, and the results presented in a general, non-specific manner. Further, no accompanying methodological reflection was offered (e.g. how the data was extracted and analyzed, for which languages, etc.).

A modest number of linguistic works have used LSI as one or the only data source for their linguistic analysis, e.g.: Anderson (2006, 2007, 2015, Bhattacharya (1970), Bubenik (1991), DeLancey (2013), Deo and Sharma (2006), Hook (1991), Klaiman (1987), Krishnamurti (1998), Masica (1986), Matisoff et al. (1996), Nath (2012), Needham (1960), Primus (1999), Rijkhoff (2002), Satyanath and Laskar (2008), and Stassen (2009); as well as in four of the maps provided in the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS; Dryer and Haspelmath 2013): Dryer (2013a, 2013b) and Stassen (2013a, 2013b). In some other cases LSI has been used as one (minor) source of data, e.g.: Bashir (2010), Emeneau (1956), LaPolla (2001), and Morey (2008). The topics of these works range from the internal subclassification of Munda languages, through internal variation in the patterns of morphological ergativity in IA, lexical and morphosyntactic changes due to language contact, sound changes and the history of postverbal agreement, language maintenance and loss in the South Asian context, to typology in general.

LSI has also been used in non-linguistic works, for example in works relating to political science (Sarangi 2009); genetics (Saraswathy et al. 2009); and script encoding and writing systems (Pandey 2015).

5 Linguistic data collection

For the work reported on here, we started out with a round of manual data collection from LSI. This was accomplished using a standardized questionnaire designed explicitly for this data collection. The questionnaire covers linguistic features relating to the sound system and grammar, including features mentioned in the literature as contributing to defining South Asia as a linguistic area. Each query is formulated in a yes-no question format. The possible feature values are: “yes”, “no”, and “no data” (“ND”). While collecting the data, when in doubt, we chose the feature value “ND”. In some cases, there are follow-up questions, which in effect means that there are “main” and “dependent” features. We chose this format, rather than a format with a variable number of feature values depending on the feature, since it makes for easier automatic formal verification and correction of the completed questionnaires.

The questionnaire covers 72 linguistic features, chosen to be retrievable from LSI, as well as for their relevance to our research questions. By taking into consideration a wide range of features, we avoid misinterpreting as areal globally frequent typological feature-clusters (e.g. verb-final+postpositions+suffixes; cf. Dryer 2003).

The questionnaires were accompanied by a set of guidelines for interpreting and answering the questions. The data collection work started with a trial round, where three MA students of linguistics with some prior experience of empirical linguistic analysis were asked to complete the questionnaires for the same languages, independently of and unbeknownst to each other, after which their responses were compared. The agreement among the responses was not absolute, but large enough to ensure that the questionnaires and guidelines could be used for the full-scale data collection. The questionnaire is provided in Appendix A. While the LSI grammar sketches were the primary source for completing the questionnaire, in some cases we also looked at the sample texts provided in LSI to substantiate the comments made in the grammatical sketches. Also, initially we had planned to collect data only from LSI, but during the data collection in some cases we broadened our base and included information from some other sources. The aim was to have as complete and correct information as possible.

The questionnaires were completed using a standardized spreadsheet format, which made automated extraction of the features from these spreadsheets fairly straightforward. Out of the approximately 450 grammar sketches at least two pages in length in LSI, about half turned out to provide a sufficient level of detail for our purposes. This has resulted in 240 completed questionnaires. The 240 languages are distributed over language families as follows.

| Dravidian | 11 | Isolate | 3 | Nuristani | 3 |

| Indo-Aryan | 124 | Munda | 8 | Tibeto-Burman | 91 |

6 Computer visualization of the LSI data

A central aspect of the investigation presented here is the relationship between linguistic genealogy (language family membership), geography, and linguistic features.

The digitized LSI offers an abundance of data of various kinds and complexity. Working with the vast stores of (digital) information generated in our project for the kind of large-scale comparative linguistic research that we are aiming for requires very good tools for exploratory data analysis, and we know from the literature that data visualization and visual analytics can contribute substantially in this connection (e.g. Chuang et al. 2012; Havre et al. 2000; Krstajić et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2013).

An important role that such e-science tools can fulfill is that of facilitating an overview – a bird’s-eye view – on datasets that are inconveniently large and/or complex, so that working with them purely manually will not be feasible. This is a mode of investigation which has long been a natural part of the corpus linguist’s methodological toolbox, but which is only now beginning to gain practitioners in various forms of large-scale comparative linguistics, historical or synchronic. For our investigation, we have drawn on three kinds of data visualization, viz. (1) phylogenetic algorithms from computational biology with accompanying network visualizations (Section 7); (2) algorithms for summarizing a large number of features as a much smaller number of factors, visualized using bar charts (Section 8); and (3) map tools, i.e. visualization of the geographical distribution of selected linguistic features or feature combinations on a map (of South Asia) (Section 9).

In the first two cases, the coverage of the features had to be sufficient for the underlying data processing, since no secure generalizations can be made on the basis of too few data points. As (arbitrary) cutoffs, we stipulated that a feature must occur with a non-ND (i.e. not missing) value in at least 100 languages in order for it to be considered, and that a language is allowed to exhibit ND values in at most 12 main (non-dependent) features.[7] This gives us a dataset with 200 languages (out of 240) and 63 features (out of 72), which was used for the various automatic procedures described below. The language family distribution of the 200 languages is as follows:

| Dravidian | 11 | Isolate (Burushaski) | 1 | Nuristani | 3 |

| Indo-Aryan | 110 | Munda | 7 | Tibeto-Burman | 68 |

7 Phylogenetic networks

Phylogenetic tree and network visualizing software has now become a stock item in the historical-comparative linguist’s toolbox (Nichols and Warnow 2008). Originally devised for calculating and providing a visual rendition of distance-based groupings of genes or proteins in order to infer biological taxonomies for the corresponding organisms, these methods are now often used by linguists to infer and display language family trees (and networks).

The network in Figure 3 was produced using SplitsTree4 (Huson and Bryant 2006). Such phylogenetic networks can be usefully deployed in an interactive fashion, in the sense that the output of a program such as SplitsTree4 may allow us to pinpoint phenomena and languages that need closer inspection, or uncover questionable assumptions underlying the preparation of input data.[8]

Neighbor-net graph for 200 LSI languages (shown here for illustration; zoomable in the digital version of the article).

SplitsTree4 can produce many different network types and offers a multitude of data preprocessing options. The visualization shown in Figure 3 is based on the neighbor-net algorithm, which shows uncertainty in cluster assignment as varying degrees of reticulation.

The language names in Figure 3 have been colored according to their geographical location on a 1° × 1° grid covering the area in question (see the insert in the figure, where we also indicate the number of languages located in each grid square). Further, the language names have suffixes indicating language family (and, in the case of IA, LSI volume), as follows:

| _DR | Dravidian | 11 | _I5 | Indo-Aryan (LSI vol. 5) | 17 |

| _MD | Munda | 7 | _I6 | Indo-Aryan (LSI vol. 6) | 2 |

| _NS | Nuristani | 3 | _I7 | Indo-Aryan (LSI vol. 7) | 9 |

| _TB | Tibeto-Burman | 68 | _I8 | Indo-Aryan (LSI vol. 8) | 32 |

| _XX | Isolate (Burushaski) | 1 | _I9 | Indo-Aryan (LSI vol. 9) | 50 |

Neighbor-net and related methods operate on pairwise distances between items, i.e. languages in our case. The distances are calculated from the linguistic feature value sets representing the languages in our database and should ideally reflect some relevant measure of similarity between the languages.

For generating the visualization shown here, the neighbor-net algorithm was applied with its default parameter and processing settings, and the language data were entered as phylogenetic character sequences,[9] from which the program calculated distances between pairs of languages using its default uncorrected-p (UP) method, which expresses distance as the proportion of differing features.[10]

Using the resulting graph to get an impressionistic bird’s eye view on the data, we see that the groupings defined there are neither all genetic nor all geographical. There are some clear genetic groupings, but also some groupings which seem to have a geographical component.

Thus, the three groupings in the top right part of Figure 3 contain only IA languages, except Kurux (DR) and the language isolate Burushaski, with one cluster representing languages of the north and northwest (including the so-called Central IA languages). Another cluster is made up of IA languages of the southwest. Finally, there is a cluster of Northern languages. On the one hand these clusters broadly correspond to proposed IA genetic groupings, but on the other hand they also reflect geography.

The bottom part of Figure 3 is dominated by TB and MD languages. In the lower righthand corner, we find a cluster consisting exclusively of eastern TB languages. In the lower middle there is cluster made up by a combination of TB and Munda languages. To the left of this there is a mixed bag of some TB and MD languages plus one DR language (Northern Gondi), and in the lower left, we again see a group consisting almost exclusively of eastern TB languages, although on its fringe we find two IA languages of the northwest (Kalasha and Indus Kohistani).

On the left side of Figure 3, there is a mixed grouping of most of the Dravidian languages and some TB languages. The upper left corner is dominated by IA languages of the east.

Finally, there are some individual languages which do not cluster with others, e.g. Khowar (IA) and Kanashi (TB).

Overlaid on top of the basic genetic clustering we can also see the contours of an areal clustering of the investigated language varieties. The main dividing line seems to be between a more westerly and a more easterly group of languages, whereas we generally see no corresponding division in the north–south direction, with one exception, mentioned below. Although the western part is made up almost only of IA languages, several easterly groupings contain languages from several families (IA, TB and Munda), thus indicating a degree of areality in the east.

One possible exception to this is provided by the seven Munda languages in our sample. They are distributed over two clusters, so that Gutob and Sora appear in a mixed group together with some TB languages of the northwest and north and one DR language (also of the north), whereas the other five Munda languages – Juang, Kharia, Korku, Mundari, and Santali – cluster together with a number of TB languages. In this case, the former two languages are spoken to the south of the latter five.

The bulk of IA languages tend to form a single bush-like (rather than tree-like) structure in the upper righthand corner of Figure 3. Within the bush there is little structure to be discerned, corresponding to the difficulties linguists have had traditionally in establishing well-defined subgroups within most of IA. However, there are some exceptions to this overall pattern, i.e. some groupings that do stand apart from the general bush-like structure, and these will be the subject of the following paragraphs.

Although Nuristani is placed outside IA (but within Indo-Iranian) by both Ethnologue and Glottolog, it is interesting both in its own right and in relation to IA languages of the northwestern area. The NS languages in our sample form a sparse grouping in the top middle of Figure 3, together with the Northwest IA language Southeast Pashai. However, this grouping also includes Rajbangsi, a member of Ethnologue’s Eastern Outer and Glottolog’s Eastern group, which means that Rajbangsi is separated from its closer relatives. Interestingly, Figure 3 shows another two Northwestern languages, Kalasha and Indus Kohistani, at the middle left of the figure widely separated from the bulk of IA, on the edge of a cluster that is otherwise TB. This suggests areal influence among some of the northernmost IA languages and their Nuristani and TB neighbors.

One part of IA that is consistently distinct from the bulk of the family is Ethnologue’s Eastern Outer, corresponding to Glottolog’s Eastern + Bihari. Note that in Figure 3, this group ends up next to the Nuristani grouping where we also find Rajbangsi (see above).

Southern is less clearly differentiated from the bulk of IA than is Eastern Outer/Eastern + Bihari. If anything, Southern IA goes with Western + Western Hindi/Central + Northern.

It should be noted that we do not see Ethnologue’s Outer primary branch in the graph. Eastern Outer/Eastern + Bihari is distinct vis-à-vis the rest of IA. The latter is only vaguely differentiated, but when it is, it tends to reflect the classification of Table 1.

Consequently, the traditional (lower-level) classification of IA is largely supported by our results. However, we must keep in mind that (1) this traditional classification largely coincides with geography; and (2) properly, only shared innovations should be used as the basis for genetic subclassification, and we do not know which of our features are shared innovations and which shared retentions. Geography is salient in Figure 3, where there is a clearly discernible predominantly red part (east) against a predominantly blue-green part (west/south), with very few incursions by out-of-area languages. We can also see that some languages cluster geographically rather than genetically, i.e. with their neighbors in preference to their relatives. This seems to be true of the Munda languages, as explained above.

However, some additional factors seem to play a role here apart from genealogy and geography. A clear example of this is presented by the TB low-level Western Himalayish subgroup represented in our sample by nine varieties (out of about 15) which are all spoken in the same general area (northern India and western Nepal), but which are distributed over four different groups in Figure 3. Chamba Lahuli, Pattani, Kinnauri and Bunan are clustered together with some TB languages of the east and some MD languages at the bottom of the figure. Darma, Chaudangsi and Rangkas are in a very mixed group (already mentioned) with three Tibetic languages (TB) spoken in the same area (Balti, Purik and Ladakhi), the MD languages Gutob and Sora, and Northern Gondi (DR). Byangsi is grouped together with two IA languages of the north-west, Kalasha and Indus Kohistani. Finally, Kanashi forms a group of its own. In this case, where genealogy and geography coincide, the expectation is that these nine languages would end up in the same cluster in Figure 3. Even if we adopt a “micro-areal” perspective and look at geography at a finer resolution, the outcome is not what we would expect. Exactly why this happens is unclear, and further study is required, e.g. of the composition of our linguistic feature set in relation to our overall question, as well as the contribution of each feature to the neighbor-net visualization.

8 Dimensionality reduction for data exploration

A popular class of methods for data exploration – including in linguistics – is based on dimensionality reduction. A large number of feature values are reduced to a (considerably) smaller number of factors or principal components, such that features that correlate are collapsed, with the consequence that similar items – seen as feature bundles – end up closer to one another in the new space defined by factors than dissimilar items. These methods are most often used with numerical data, in linguistics typically with corpus frequencies (e.g. Xiao 2009). However, some of them are also applicable to categorical data such as the linguistic features collected for the present study.

This reduction of a large number of features to a smaller number of factors is in principle analogous to the situation when linguists note that certain linguistic feature values tend to co-occur in many languages, and posit some more abstract common feature designed to subsume the co-occurring concrete features. For example, the favored combination of OV and GenN word orders and postpositions may be expressed more abstractly as reflecting a principle of dependent-head ordering. The factors resulting from dimensionality-reduction methods correspond to such abstract features with the difference that they are not named and that they are automatically calculated from the concrete features and their values. The latter property makes them maximally objective.

Here we report on some experiments where we apply multiple correspondence analysis (MCA; Abdi and Valentin 2007) to the LSI data and inspect the emerging “fingerprints” of characteristic principal components in relation to genetic and geographical language groupings. We used the same dataset as in the experiments reported above in Section 7, with one difference. When applying MCA to a dataset, it is necessary to decide how missing datapoints (those coded as “ND”) should be treated (Josse et al. 2012). The process of supplying such missing values is referred to as imputation in the literature. Under the reasonable assumption that missing values in our dataset are missing at random – i.e. that their distribution should correspond to that of the attested values – they were imputed by a method called multiple imputation by chained equations (Azur et al. 2011) before the dataset was subjected to MCA.[11]

As with other dimensionality reduction methods, the factors produced by applying MCA to a data set account for a rapidly decreasing portion of the variance in the data. In other words, the first few factors provide a fair generalization over the data at the cost of some loss of detail. Results from such methods are often presented as points on a coordinate system defined by the first two factors. With 200 languages and 126 (2×63) features[12] such a rendering runs the risk of becoming very cluttered, so we have opted for two other modes of presentation here.

The MCA computation provides information about the contribution of each language and each feature to each factor. One way of testing hypotheses about natural groupings of languages in our dataset will consequently be to investigate the patterns of average contributions to the factors of extrinsically defined language groupings, to see whether these patterns are noticeably different. In Figure 4, we study the contributions of various language groupings to the four most prominent MCA factors, which jointly account for slightly over 80% of the variation in the data. Table 3 shows the contributions of some of the linguistic features to the four main MCA factors resulting from our computation. Features which jointly contribute much (or little) to a factor tend to co-occur in the dataset.

Language grouping contributions to the main MCA factors.

Some of the feature contributions to main MCA factors.

| Factor | Large contribution | Small contribution |

|---|---|---|

| F1 | Dual forms | Genitive – noun word order |

| Same S/non-S noun form | Demonstrative – noun word order | |

| No distinct 3PERS reflexive pronoun | Obligatory copula | |

| No correlative relative clauses | Ergative | |

| 3PERS pronoun not same as demonstrative | Demonstrative suffix on noun | |

| F2 | Noun – demonstrative word order | Nominal plural marking |

| Dual forms | Genitive – noun word order | |

| Not negation – verb order | Demonstrative – noun word order | |

| Ablative marker not used as comparative | Correlative relative clauses | |

| Tone | Arguments indexed on verb | |

| Noun plural not a suffix | Plural suffix on noun | |

| F3 | No ergative | Demonstrative – noun word order |

| No obligatory copula | Aspirated consonants | |

| Different negative copula | Dative same as accusative | |

| Same S/non-S pronoun form | Negation – verb word order | |

| Front rounded vowels | Demonstrative is a prefix on noun | |

| No aspirated consonants | Dual forms | |

| F4 | Noun plural suffixed particle | Copula |

| No correlative relative clauses | Genitive – noun word order | |

| No verb indexing system | Dative same as accusative | |

| No retroflex consonants | Retroflex consonants | |

| No distinct 3PERS reflexive pronoun | Distinct 3PERS reflexive pronoun | |

| Noun plural not a suffix | Demonstrative – noun word order | |

| Dual forms | Ergative |

At the top of Figure 4, the language families are in focus, and at the bottom left and bottom right of Figure 4 we see how geographical groupings contribute to the factors (north–south and west–east, respectively). We see clear differences among language families. Not surprisingly, IA and Nuristani are quite similar, while Dravidian and Munda stand out as “mirror images” of each other. If we look at the third factor (to which DR makes a distinct contribution), in Table 3 we see that the large feature contributions to this factor include lack of aspirated consonants, no ergative, and different negative copula.

There are also clear geographical differences in the factor patterns. However, the distinct profile of the southernmost area that we see in Figure 4 (bottom left) is almost exactly the same as that of Dravidian in Figure 4 (top), which may be an indication that in this particular case the geographical and genetic groupings actually comprise almost the same set of languages.

As for the west–east direction, even if the cutoff points are partly arbitrarily chosen, Figure 4 (bottom right) indicates a clear west-east division. This reinforces the impression from the neighbor-net graph in Section 7, that the main areal-linguistic dividing line in South Asia is one that distinguishes a western and an eastern part, and also coincides with observations made in the literature (Hock and Bashir 2016; Peterson 2017: 241–242, 327–328).

9 Map visualization for exploration of language genealogy and geography

For an alternative high-level view of the LSI data, we have modified an existing mapping solution into an interactive standalone application where the users can view the distribution of linguistic features in LSI varieties on a map. We provide switchable shape/color combinations for visualizing and differentiating family/feature characteristics. Figure 5 shows a snapshot visualizing the feature s3sg (“Is the form of the pronominal 3sg subject the same in intransitive and transitive clauses?”), i.e. an indicator of absolutive–ergative (or tripartite) alignment (map legend “!=”) versus other alignment types (nominative–accusative or neutral: map legend “==”) in languages belonging to the IA and TB families.[13] The user can select multiple families and multiple features at the same time by checking the appropriate check-boxes, and can also switch between color/symbol to visualize feature/family by selecting the appropriate radio button. In the map in Figure 5 we have selected feature values to be encoded by color, while the shape of the markers indicates language family (I for IA and T for TB in Figure 5). In this map we can discern a clear areal distribution of this feature in South Asia, such that “==” values, interpreted as accusative alignment, are mainly found in the east, regardless of language family. This reinforces the west-east difference that we saw in the previous two visualizations.

Map showing form of subject pronoun in relation to transitivity.

Such an interactive mapping facility provides a useful way to explore the genetic relations and areal influences between languages spoken in different geographical areas and belonging to different language families.

10 Conclusions and future work

The results from applying various data visualizations to our linguistic feature sets are intriguing. The phylogenetic networks produced by SplitsTree4 provide some support to both some traditional subclassifications of IA, and to the notion of an areal east-west divide in South Asia (Section 7). The latter is reinforced both by the MCA rendering of our dataset (Section 8) and by the map visualizations of individual linguistic features (Section 9) shown above.

Geography “shines through” in all three visualizations, but none of them does a good job of revealing genealogical connections. All three point to a west– east areal divide, but at the same time the western part is almost exclusively IA, and non-IA languages located in the west cluster with their relatives in the east in the neighbor-net graph.

The weak genealogical signal could be due to the choice of linguistic structural features as the basis for comparison (see Appendix A), which perhaps are not diagnostic at the fairly shallow time depth of IA, the language family in focus here (see, e.g. Dunn et al. 2005, 2008).

Fortunately, visualization tools such as these are exploratory in more than one way. In addition to allowing us to explore large amounts of language data, they also more subtly give us a window onto otherwise opaque computational processes, and the impact of different kinds of input to these processes (e.g. structural vs. lexical features). We mentioned in Section 7 above (in footnote 10) that we have experimented with different distance measures as input to the network-constructing algorithms offered by SplitsTree4, and that the distance measure used influences the resulting clustering, which is relevant i.a. to the question of areal versus genealogical connections mentioned above. This matter requires further research. In this connection we may also note that the two measures which we have tried out – the UP measure used by default by SplitsTree4 and cosine distance – in effect treat all features alike. Intuitively, it would make sense to be able to weight the influence of individual features differently, or alternatively use a rule-based component to preprocess some features or feature configurations, for example in order to capture known dependencies among features (see, e.g. Hammarström and O’Connor 2013; Saxena and Borin 2013). This must be left for future work, however.

There are many directions in which this work could be taken further, both computational and linguistic.

A reviewer has suggested that the visualizations could be supplemented by quantitative tests which would help the user to put conclusions based on impressionistic visual evidence on a firmer footing. This is a good suggestion, which we aim to include in our further work. We see the function of the computational tools presented here primarily as “filters” helping the linguist to separate small amounts of wheat from large volumes of chaff, not by identifying the wheat directly, but by identifying those parts of the data where it is likely to hide and be found by manual inspection.

With the work presented here, we hope to have shown that the combination of the bird’s-eye view afforded by large-scale automated data visualization and more detailed linguistic analysis is a fruitful methodological procedure for pursuing genetic and areal linguistics on a large scale. Having visualization aids such as these at our disposal has helped us investigate the LSI data in a way which would not have been possible otherwise, or at least would have been much more difficult.

We further hope that this work will contribute to the theoretical debate on the prehistory of this region; earlier settlements and migrations; the relationship between language contact, areal linguistics and typology; borrowability in language contact; and to a wider awareness of South Asian linguistic diversity.

10.1 Availability of data and tools

In addition to the map application described in Section 9, we have also built a CLLD map interface (Forkel 2014) where the questionnaire data can be browsed. The digitized LSI is searchable through the state-of-the-art corpus tool Korp (Borin et al. 2012), and the semantic parser developed in the project for automatic extraction of linguistic information from the LSI grammar sketches (Virk et al. 2019) can be tried out online. All these interfaces and tools can be reached through the project web pages at https://spraakbanken.gu.se/en/projects/digital-lsi.

Funding source: Swedish Research Council

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2014-00969 (South Asia as a linguistic area?)

Funding source: University of Gothenburg

Award Identifier / Grant number: Språkbanken

Funding source: Swedish Research Council

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2013-02003 (Swe-Clarin)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anna Sjöberg, Maryam Nourzaei and Tim Roberts for their assistance in compiling the questionnaires. Our thanks also go out to an anonymous reviewer who made a number of perceptive comments and suggestions.

-

Research funding: The work presented here was funded by the Swedish Research Council as part of the project South Asia as a linguistic area? Exploring big-data methods in areal and genetic linguistics (2015–2019, contract no. 421-2014-969), as well as by the University of Gothenburg and the Swedish Research Council through their funding of the Språkbanken and Swe-Clarin research infrastructures.

A Questionnaire

The linguistic features provided in the questionnaire are listed in the table below. Broadly corresponding WALS features are given in the first column. The features are classified as main or dependent, indicated by “M” or “D” in the second column, where each D feature is dependent on the most immediately preceding M feature. The last column shows which features have a non-ND value in at least 100 languages (“+”) and consequently have been used to generate the SplitsTree4 graphs and the multiple correspondence analysis factor diagrams discussed in the text (Sections 7 and 8).

| WALS | M/D | Feature | ST? |

|---|---|---|---|

| – | M | Does this language have aspirated consonant(s) as phoneme(s)? | + |

| – | M | Does this language have retroflex consonant(s) as phoneme(s)? | + |

| 10A | M | Does this language have nasal vowel(s) as phoneme(s)? | – |

| 11A | M | Do front rounded vowels occur in this language, whether as phonemes or as variants? | + |

| 13A | M | Does this language have simple phonemic tone? | + |

| 13A | D | If yes, does this language have complex phonemic tone? | + |

| – | M | Does the same noun form occur in both S and non-S contexts? | + |

| 34A | M | Does this language mark plural for nominals? | + |

| 33A | D | If yes, is/are the plural marker(s) (a) suffix(es)? | + |

| 33A | D | If yes, is/are the plural marker(s) (a) prefix(es)? | + |

| 33A | D | If yes, is/are the plural marker(s) (a) particle(s) [=independent form] following nominals? | + |

| 33A | D | If yes, is/are the plural marker(s) (a) particle(s) [=independent form] preceding nominals? | + |

| – | M | Does the language mark dual for nominals? | + |

| – | D | If yes, is the dual marker a suffix? | + |

| – | D | If yes, is the dual marker a prefix? | + |

| – | D | If yes, is the dual marker a particle which precedes nominals? | + |

| – | D | If yes, is the dual marker a particle which follows nominals? | + |

| – | M | Does the language mark dual in at least one pronoun? | + |

| – | D | If yes, does the language mark dual on first person pronominal pronoun? | + |

| – | D | If yes, does the language mark dual on second person pronominal pronoun? | + |

| – | D | If yes, does the language mark dual on third person pronominal pronoun? | + |

| 49A | M | Are there maximum 2 adnominal cases which are explicitly marked (affixes and/or postpositions)? | + |

| 49A | M | Are there 3 maximum adnominal cases which are explicitly marked (affixes and/or postpositions)? | + |

| 49A | M | Are there maximum 4 adnominal cases which are explicitly marked (affixes and/or postpositions)? | + |

| 49A | M | Are there 5 or more adnominal cases which are explicitly marked (affixes and/or postpositions)? | + |

| 98A | M | Does the language have an ergative adnominal case (affixes and/or postpositions)? | + |

| – | M | Does the same adnominal case marker function both as the genitive and as the ergative marker? | + |

| – | M | Does the same adnominal case marker function both as the accusative and as the dative marker? | + |

| – | M | Does the same adnominal case marker function both as the ergative and as the instrumental marker? | + |

| – | M | Does the same adnominal case marker function both as the ablative and as the instrumental marker? | + |

| – | M | Does the same adnominal case marker function both as the dative and as the locative marker? | + |

| – | M | Does the same ablative adnominal case marker also function as the comparative/superlative marker(s)? | + |

| – | M | Do lexical adjectives remain invariant with regard to gender and number of their head-nouns? | + |

| 86A | M | Is the genitive–noun [GEN-noun] order the dominant order? | + |

| 86A | M | Is the noun–genitive [noun-GEN] order the dominant order? | + |

| – | M | Does the same pronominal form occur in both S and non-S contexts? | + |

| 45A | M | Is there a distinct second person singular honorific pronoun? | + |

| 45A | M | Is the first person plural pronoun also used for the first person singular referent as a marker for respect towards the person one is talking to? | – |

| 45A | M | Is the second person plural pronoun also used for the second person singular referent as a marker for respect towards the person one is talking to? | – |

| 45A | M | Is the third person plural pronoun also used for third person singular honorific referent as a marker of respect towards the referent? | – |

| 44A | M | Does this language make a distinction between inanimate and animate referents in 3rd person singular pronouns? | + |

| – | M | Does this language make a distinction between masculine and feminine referents in 3rd person singular pronouns? | + |

| – | M | Does this language make a distinction between masculine and feminine referents in 2nd person pronouns? | + |

| – | M | Does this language make a distinction between masculine and feminine referents in 1st person pronouns? | + |

| 39A | M | Is there an exclusive-inclusive distinction in 1st person plural pronouns? | + |

| – | M | Does this language have demonstratives? | + |

| – | D | If yes, is the demonstrative a suffix on the noun? | + |

| – | D | If yes, is the demonstrative a prefix on the noun? | + |

| – | D | If yes, is the demonstrative a particle in this language? | + |

| 88A | M | If demonstratives are independent morphemes in this language, does the order demonstrative–noun [DEM-noun] occur? | + |

| 88A | M | If demonstratives are independent morphemes in this language, does the order noun–demonstrative [noun-DEM] occur? | + |

| 88A | D | If both alternatives [DEM-noun & noun-DEM] are found, is the order DEM–noun the dominant order in this language? | + |

| 88A | D | If both alternatives [DEM-noun & noun-DEM] are found, is the order noun–DEM the dominant order in this language? | + |

| 43A | M | Is the third person pronoun the same as one of the demonstratives? | + |

| – | M | Are there reflexive pronouns? | + |

| – | D | If yes, is the reflexive pronoun an invariant form which occurs in all persons? | – |

| – | D | If yes, is the third person reflexive pronoun a distinct anaphoric pronoun (distinct from 3SG nominative and/or object form), but in the first and second persons the regular object pronominal form occurs? | – |

| 90E | M | Is the correlative strategy a productive relative clause formation mechanism? | + |

| 93A | M | Do the interrogative phrases in content questions [=WH questions] occur obligatorily in-situ? | + |

| 102A | M | Does this language have a verb indexing system (i.e. subject/object/agent/patient index on the verb) in declaratives? | + |

| – | D | If yes, does the language mark dual in verb indexing? | + |

| 79B | M | Do verbs ‘go’ and/or ‘come’ have suppletive verb forms in the imperative? | + |

| – | M | Is the prohibitive verb form (almost) the same as the 2SG imperative verb form (excluding, of course, the negation marker in the prohibitive)? | – |

| 120A | M | Is there an overt copula verb (=‘be’) in equational clauses? | + |

| 120A | D | If yes, does the copula verb occur obligatorily in equational clauses? | + |

| 79A | M | Does the copula verb (=‘be’) have a suppletive form in the past tense? | + |

| 79A | M | Does the verb ‘go’ have a suppletive form in either the past or the perfective? | + |

| 143A | M | Does the negation marker (affix and/or particle) precede simple finite verbs? | + |

| 143A | M | Does the negation marker (affix and/or particle) follow simple finite verbs? | + |

| – | M | If this language has more than one instance of negative markers, is the distribution of these negation markers determined by the choice of tense/aspect? | – |

| – | M | Does the same or almost the same negation marker occur in both copula and non-copula clauses? | + |

| – | M | Does the same negation marker occur in both declaratives and prohibitives? | – |

References

Abdi, Hervé & Dominique Valentin. 2007. Multiple correspondence analysis. In Neil J. Salkind (ed.), Encyclopedia of measurement and statistics, 651–657. Thousand Oaks: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, Gregory D. S. 2006. Auxiliary verb constructions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199280315.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, Gregory D. S. 2007. The Munda verb: Typological perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110924251Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, Gregory D. S. (ed.). 2015. The Munda languages. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315822433Suche in Google Scholar

Asher, Ronald E. 2008. Language in historical context. In Braj B. Kachru, Yamuna Kachru & Shikarupur N. Sridhar (eds.), Language in South Asia, 31–46. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511619069.004Suche in Google Scholar

Azur, Melissa J., Elizabeth A. Stuart, Constantine Frangakis & Philip J. Leaf. 2011. Multiple imputation by chained equations: What is it and how does it work? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 20(1). 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.329.Suche in Google Scholar

Bashir, Elena. 2010. Innovations in the negative conjugation of the Brahui verb system. Journal of South Asian Languages and Linguistics 3(1). 23–43.Suche in Google Scholar

Bhattacharya, Sudhibhushan. 1970. Kinship terms in the Munda languages. Anthropos 65(3/4). 444–465.Suche in Google Scholar

Bloch, Jules. 1950. Les inscriptions d’Asoka. Paris: Société d’Edition «Les Belles Lettres».Suche in Google Scholar

Bloch, Jules. 1954. The grammatical structure of Dravidian languages. Pune: Deccan College.Suche in Google Scholar

Borin, Lars, Markus Forsberg & Johan Roxendal. 2012. Korp – the corpus infrastructure of Språkbanken. In Proceedings of language resources and evaluation (LREC) 2012, 474–478. Istanbul: European Language Resources Association.Suche in Google Scholar

Borin, Lars, Shafqat Mumtaz Virk & Anju Saxena. 2016. Towards a big data view on South Asian linguistic diversity. In WILDRE-3 – 3rd Workshop on Indian Language Data: Resources and Evaluation, 87–92. Portorož: European Language Resources Association.Suche in Google Scholar

Borin, Lars, Shafqat Mumtaz Virk & Anju Saxena. 2018. Language technology for digital linguistics: Turning the linguistic survey of India into a rich source of linguistic information. In Alexander Gelbukh (ed.), Computational linguistics and intelligent text processing, 550–563. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-77113-7_42Suche in Google Scholar

Bubenik, Vit. 1991. Contact-induced morphosyntactic change in the North-West Indo-Aryan languages. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 72/73(1/4). 701–713.Suche in Google Scholar

Burrow, Thomas & Murray B. Emeneau. 1984. A Dravidian etymological dictionary, 2nd edn. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Cardona, George. 1974. The Indo-Aryan languages. In Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edn., vol. 9, 439–450. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.Suche in Google Scholar

Cardona, George & Dhanesh Jain (eds.). 2003. The Indo-Aryan languages. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203214961-20Suche in Google Scholar

Cathcart, Chundra A. 2020. A probabilistic assessment of the Indo-Aryan Inner–Outer hypothesis. Journal of Historical Linguistics 10(1). 42–86. https://doi.org/10.1075/jhl.18038.cat.Suche in Google Scholar

Chatterji, Suniti Kumar. 1926. The origin and development of the Bengali language. London: Allen & Unwin.Suche in Google Scholar

Chuang, Jason, Daniel Ramage, Christopher D. Manning & Jeffrey Heer. 2012. Interpretation and trust: Designing model-driven visualizations for text analysis. In ACM human factors in computing systems (CHI). http://vis.stanford.edu/papers/designing-model-driven-vis (accessed 12 August 2020).10.1145/2207676.2207738Suche in Google Scholar

DeLancey, Scott. 2013. The history of postverbal agreement in Kuki-Chin. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 6. 1–17.Suche in Google Scholar

Deo, Ashwini & Devyani Sharma. 2006. Typological variation in the ergative morphology of Indo-Aryan languages. Linguistic Typology 10(3). 369–418. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty.2006.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew S. 2003. Word order in Sino-Tibetan from a typological and geographical perspective. In Graham Thurgood & Randy J. LaPolla (eds.), The Sino-Tibetan languages, 43–55. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew S. 2013a. Feature 26A: Prefixing versus suffixing in inflectional morphology. In Matthew S. Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), WALS online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. https://wals.info/feature/26A.Suche in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew S. 2013b. Feature 51A: Position of case affixes. In Matthew S. Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), WALS online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. https://wals.info/feature/51A.Suche in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew S. & Martin Haspelmath (eds.). 2013. WALS online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.Suche in Google Scholar

Dunn, Michael, Angela Terrill, Ger Reesink, Robert A. Foley & Stephen C. Levinson. 2005. Structural phylogenetics and the reconstruction of ancient language history. Science 309. 2072–2075. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1114615.Suche in Google Scholar

Dunn, Michael, Stephen C. Levinson, Eva Lindström, Ger Reesink & Angela Terrill. 2008. Structural phylogeny in historical linguistics: Methodological explorations applied in Island Melanesia. Language 84(4). 710–759. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.0.0069.Suche in Google Scholar

Ebert, Karen. 2006. South Asia as a linguistic area. In Keith Brown (ed.), Encyclopedia of languages and linguistics, 2nd edn., 557–564. Oxford: Elsevier.10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00214-5Suche in Google Scholar

Emeneau, Murray B. 1956. India as a linguistic area. Language 32(1). 3–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/410649.Suche in Google Scholar

Emeneau, Murray B. 1980. The Indian linguistic area revisited. In Anwar S. Dil (ed.), Essays by Murray B. Emeneau, 197–249. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Forkel, Robert. 2014. The cross-linguistic linked data project. In 3rd workshop on linked data in linguistics, 60–66. Reykjavik: European Language Resources Association.Suche in Google Scholar

Gair, James W. 2012. Sri Lankan languages in the South-South Asia linguistic area: Sinhala and Sri Lanka Malay. In Sebastian Nordhoff (ed.), The genesis of Sri Lanka Malay. A case of extreme language contact, 165–194. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004242258_008Suche in Google Scholar

Georg, Stefan. 2017. Other isolated languages of Asia. In Lyle Campbell (ed.), Language isolates, 139–161. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315750026-6Suche in Google Scholar

Grierson, George A. 1903–1927. A linguistic survey of India, vol. I–XI. Calcutta: Government of India, Central Publication Branch.Suche in Google Scholar

Grierson, George A. 1927. A Linguistic Survey of India. Vol. I. Part 1. Introductory.. Calcutta: Government of India, Central Publication Branch.Suche in Google Scholar

Grimmer, Justin & Brandon M. Stewart. 2013. Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis 21(3). 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028.Suche in Google Scholar

Hammarström, Harald & Loretta O’Connor. 2013. Dependency-sensitive typological distance. In Lars Borin & Anju Saxena (eds.), Approaches to measuring linguistic differences, 329–352. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110305258.329Suche in Google Scholar

Hammarström, Harald, Robert Forkel & Martin Haspelmath. 2019. Glottolog 4.0. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. https://glottolog.org (accessed on 12 October 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Havre, Susan, Beth Hetzler & Lucy Nowell. 2000. ThemeRiver: Visualizing theme changes over time. In IEEE symposium on information visualization (InfoVis), 2000, 115–123. Salt Lake City: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.10.1109/INFVIS.2000.885098Suche in Google Scholar

Hock, Hans Henrich. 2001. Typology versus convergence: The issue of Dravidian/Indo-Aryan similarities revisited. In The yearbook of South-Asian languages and linguistics 2001: Tokyo symposium on South Asian languages: Contact, convergence and typology, 63–99. Delhi: Sage.10.1515/9783110245264.63Suche in Google Scholar

Hock, Hans Henrich & Elena Bashir (eds.). 2016. The languages and linguistics of South Asia: A comprehensive guide. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110423303Suche in Google Scholar

Hoernle, Rudolf. 1880. A comparative grammar of the Gaudian languages. London: Trübner & Co.Suche in Google Scholar

Hook, Peter E. 1977. The distribution of the compound verb in the languages of North India and the question of its origin. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 6. 336–351.Suche in Google Scholar

Hook, Peter E. 1987. Linguistic areas: Getting at the grain of history. In George Cardona & Norman H. Zide (eds.), Festschrift for Henry Hoenigswald: On the occasion of his seventieth birthday, 155–168. Narr: Tübingen.Suche in Google Scholar

Hook, Peter Edwin. 1991. The emergence of perfective aspect in Indo-Aryan languages. In Elizabeth Closs Traugott & Bernd Heine (eds.), Approaches to grammaticalization: Volume II. Types of grammatical markers, 59–89. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.19.2.05hooSuche in Google Scholar

Huson, Daniel H. & David Bryant. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 23(2). 254–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msj030.Suche in Google Scholar

Josse, Julie, Marie Chavent, Benot Liquet & François Husson. 2012. Handling missing values with regularized iterative multiple correspondence analysis. Journal of Classification 29. 91–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00357-012-9097-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Kachru, Braj B., Yamuna Kachru & Shikarupur N. Sridhar (eds.). 2008. Language in South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511619069Suche in Google Scholar

Katre, Sumitra Mangesh. 1968. Problems of reconstruction in Indo-Aryan. Simla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study.Suche in Google Scholar

Kirby, James & Marc Brunelle. 2017. Southeast Asian tone in areal perspective. In Raymond Hickey (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of areal linguistics, 703–731. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781107279872.027Suche in Google Scholar

Klaiman, Miriam H. 1987. Mechanisms of ergativity in South Asia. Lingua 71(1). 61–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3841(87)90068-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju. 1998. Regularity of sound change through lexical diffusion: A study of S > H in Gondi dialects. Language Variation and Change 10(2). 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954394500001289.Suche in Google Scholar

Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju. 2003. The Dravidian languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486876Suche in Google Scholar

Krstajić, Miloš, Mohammad Najm-Araghi, Florian Mansmann & Daniel A. Keim. 2012. Incremental visual text analytics of news story development. Proceedings of visualization and data analysis (VDA) 2012, 829407. Burlingame, California: SPIE – The International Society for Optical Engineering.10.1117/12.912456Suche in Google Scholar

Kuiper, Franciscus B. J. 1967. The genesis of a linguistic area. Indo-Iranian Journal 10(2). 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00184176.Suche in Google Scholar

LaPolla, Randy J. 2001. The role of migration and language contact in the development of the Sino-Tibetan language family. In Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald & Robert M. W. Dixon (eds.), Areal diffusion and genetic inheritance: Problems in comparative linguistics, 225–254. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198299813.003.0009Suche in Google Scholar

Malm, Per, Shafqat Mumtaz Virk, Lars Borin & Anju Saxena. 2018. LingFN : Towards a framenet for the linguistics domain. In Proceedings of the IFNW [International FrameNet Workshop] 2018 workshop on multilingual FrameNets and constructicons at LREC [Language Resources and Evaluation Conference] 2018, 37–43. Miyazaki: European Language Resources Association.Suche in Google Scholar

Masica, Colin P. 1976. Defining a linguistic area: South Asia. Chicago: Chicago University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Masica, Colin P. 1986. Definiteness-marking in South Asian languages. In Bhadriraju Krishnamurti, Colin P. Masica & Anjani Kumar Sinha (eds.), South Asian languages: Structure, convergence and diglossia, 123–146. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.Suche in Google Scholar

Masica, Colin P. 1991. The Indo-Aryan languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Matisoff, James A. 2003. Handbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman. System and philosophy of Sino-Tibetan reconstruction. Berkeley: University of California Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Matisoff, James A., Stephen P. Baron & John B. Lowe. 1996. Languages and dialects of Tibeto-Burman. Berkeley: University of California.Suche in Google Scholar

Moretti, Franco. 2013. Distant reading. London: Verso.Suche in Google Scholar