Abstract

Background

Perinatal deaths are a devastating experience for all families and healthcare professionals involved. Audit of perinatal mortality (PNM) is essential to better understand the factors associated with perinatal death, to identify key deficiencies in healthcare provision and should be utilised to improve the quality of perinatal care. However, barriers exist to successful audit implementation and few countries have implemented national perinatal audit programs.

Content

We searched the PubMed, EMBASE and EBSCO host, including Medline, Academic Search Complete and CINAHL Plus databases for articles that were published from 1st January 2000. Articles evaluating perinatal mortality audits or audit implementation, identifying risk or care factors of perinatal mortality through audits, in middle and/or high-income countries were considered for inclusion in this review. Twenty articles met inclusion criteria. Incomplete datasets, nonstandard audit methods and classifications, and inadequate staff training were highlighted as barriers to PNM reporting and audit implementation. Failure in timely detection and management of antenatal maternal and fetal conditions and late presentation or failure to escalate care were the most common substandard care factors identified through audit. Overall, recommendations for perinatal audit focused on standardised audit tools and training of staff. Overall, the implementation of audit recommendations remains unclear.

Summary

This review highlights barriers to audit practices and emphasises the need for adequately trained staff to participate in regular audit that is standardised and thorough. To achieve the goal of reducing PNM, it is crucial that the audit cycle is completed with continuous re-evaluation of recommended changes.

Introduction

Perinatal death can have significant psychological, social and even financial effects on parents and families and may also have serious implications for healthcare professionals involved [1], [2], [3], [4]. To understand how to improve the care provided to mothers and babies and reduce these deaths, it is important to collect data surrounding these events, monitor trends over time, identify risk factors and causes of death, and use this valuable information as learning opportunities for improvement [5], [6], [7]. This can be achieved through auditing of perinatal mortality (PNM), including both stillbirths and deaths soon after delivery, referred to as neonatal deaths.

Perinatal mortality is used as one of the main indicators for the quality of care provided to mothers and infants [5, 6]. After the 2015 Millennium Development Goals identified maternal health and infant mortality as priority goals for United Nations’ (UN) countries, the current Sustainable Development Goals highlighted the specific need to reduce preventable perinatal deaths, including stillbirth and neonatal deaths, around the world [8]. Stillbirths in particular have a history of being underreported, unrecorded and under-researched, contributing to the higher proportions of stillbirth rates compared to neonatal deaths in high- and low-income countries [8, 9]. The U.N. has, most recently, estimated a global stillbirth rate of 13.9 stillbirths per 1,000 total births, when using the international comparison of gestational age after 28 weeks gestation, and a global neonatal death rate of 17 deaths per 1,000 live births, of neonates 0–27 days old [10, 11]. The most recent Europeristat report published in 2019, found the European stillbirth rate in 2015 was 2.7 per 1,000 total births, and the neonatal death rate (for births after 24 weeks gestation) of 1.7 neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births [12, 13]. This report includes data for indicators of maternal and newborn health in 2015 and its data collection commenced in January 2017, highlighting the challenges in obtaining timely and accurate data on such indicators. Although data has shown some reduction of perinatal mortality rates from 2010 to 2015, the differences recorded among high income countries demonstrates that there is still room for improvement [12]. The United Nations goals have brought further awareness and changes to maternal and fetal care, however further work is needed to successfully achieve these and end preventable stillbirths and neonatal deaths [8, 10, 11].

Although in the past decades 51 countries have implemented audit policies for maternal mortality and morbidity, only 17 countries have implemented similar policies for perinatal mortality and morbidity [14]. This evidences the need to develop policies and strategies across the globe to better measure PNM and analyze what could be done to reduce it. The ‘Every Newborn Action Plan’ (ENAP), developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), proposed the reduction of stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates to less than 12/1,000 by 2030 [15]. One of this initiative’s key strategies specifically focuses on the importance of collecting audit data surrounding stillbirths and neonatal deaths [15].

Auditing allows the identification of maternal or fetal risk factors increasing the likelihood of PNM, or the monitoring of substandard care factors (SSCF) that range from adequate identification of risk factors by healthcare providers, to how the organization of a hospital may have affected the outcome of a delivery [7, 16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. The WHO recommends measuring specific indicators, such as perinatal and stillbirth mortality rates, and indicators of care, such as the presence of a skilled attendant at birth, or the use of antenatal corticosteroids [15, 29]. By implementing audits and utilizing them as an intervention method [30] it is possible to identify and form recommendations or action plans with the goal of improving antenatal care to reduce perinatal mortality rates [5, 7, 16, 22, 28, 31], [32], [33].

The WHO has deemed the implementation of perinatal audit and review essential to achieve goals in reducing perinatal loss [9]. Notwithstanding this, clear barriers have been identified to implementing audits and only a few countries have successfully realized national perinatal audits. It is acknowledged that the completion of perinatal audit cycles as well as the formation of recommendations and action plans based on their results, remains one of the major challenges faced in successful perinatal audit implementation [34].

This systematic review aims to explore and summarize current literature on the implementation of perinatal mortality audits in middle/high-income countries. It intends to identify factors affecting the implementation of PNM audits and the reporting of perinatal deaths. This review also plans to study the identification of risk and substandard care factors associated with perinatal outcomes through audits. Additionally, it aims to outline and identify the implementation of outcomes or measures stemming from perinatal mortality audits or reporting programs.

Methodology

Search strategy

For this systematic review, a search of the following electronic databases was conducted: PubMed, EMBASE and EBSCO host, including Medline, Academic Search Complete and CINAHL Plus with Full Text. This was completed by two reviewers independently, with specifically established search criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria.

For all databases, the following search terms were used:

(perinatal OR stillbirth OR neonatal OR stillborn OR intrauterine death) AND (mortality or morbidity or death) N5 (audit or surveillance or report)

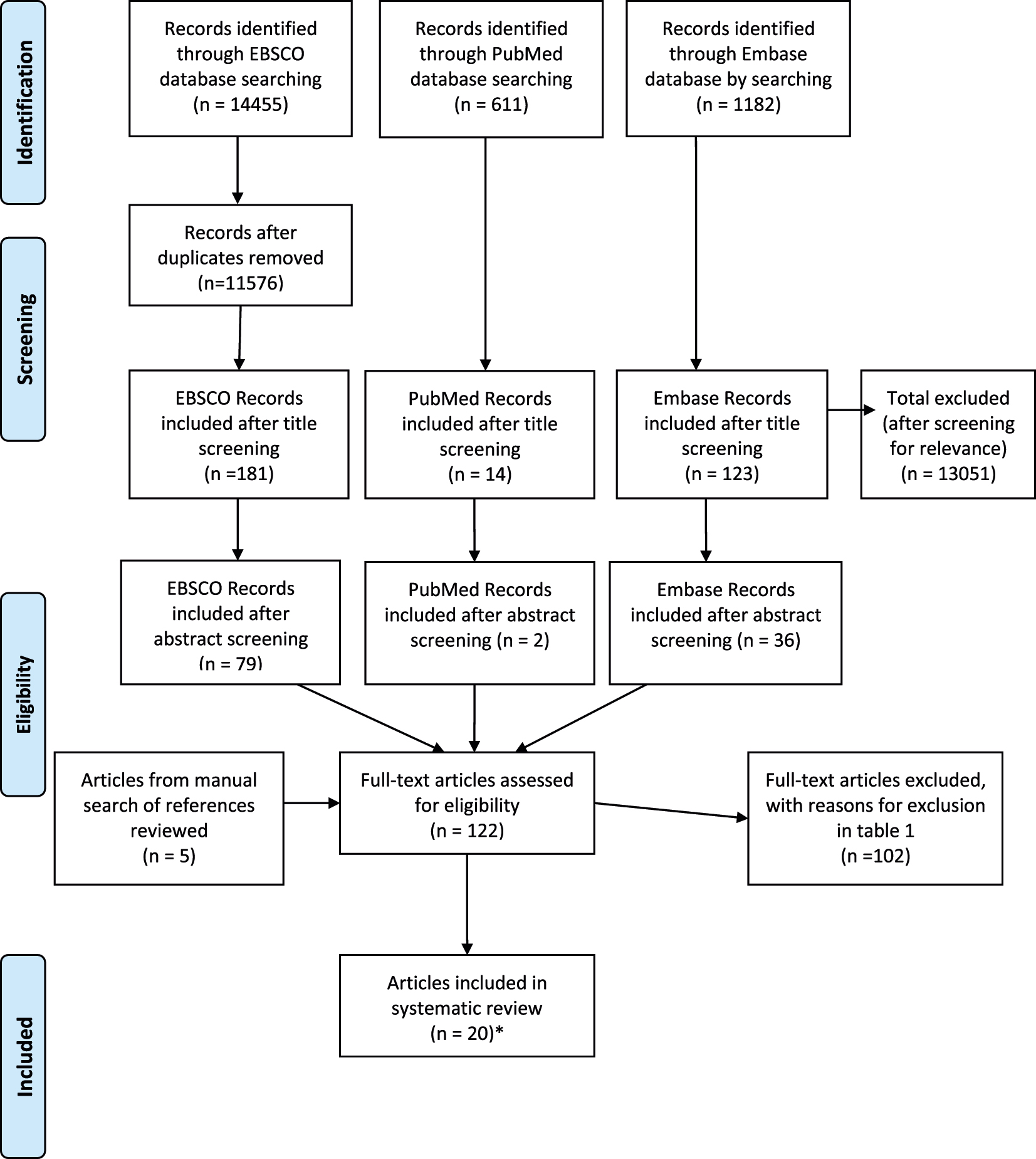

The initial searches yielded a total of 16,248 articles, reduced to 13, 369 with the removal of some duplicates by the EBSCO database. These publications were subsequently screened according to their titles, generating 318 to be reviewed by abstracts. This selection process is summarized as a flow chart in Figure 1.

Flow chart of selection process.

Selection process and criteria

Peer-reviewed articles, with a publication date from 2000 and in English, Portuguese or Spanish were considered for inclusion in the review, according to the language abilities of reviewers. Both qualitative and quantitative research manuscripts were reviewed. Furthermore, articles evaluating perinatal mortality audits or reporting, identifying risk or care factors of perinatal mortality through audits, evaluating perinatal mortality audit implementation and focused on middle and/or high-income countries were considered for inclusion in this systematic review. High and middle income countries were defined according to data from the World Bank [35]. Grey literature was not included nor manuscripts focusing primarily on maternal morbidity/mortality audits or perinatal mortality audits in low-income countries or low resource settings were considered for inclusion as they are beyond the remit of this systematic review. Significant differences in maternity service provision exist between high and low income countries and the focus in reducing perinatal mortality in low resource settings also differs substantially from maternity centres in high income countries [36]. Challenges and facilitators to perinatal audit are likely to differ greatly between these two groups and therefore discussion of perinatal audit in low income countries was considered beyond the scope of this review.

A total of 122 studies were selected for in depth, full-text review by the two reviewers. Articles found during full-text review were cross-referenced to ensure coherence in the selection process. A third reviewer supervised the review process and was available for disagreements or uncertainties related to study selection.

Full text was analyzed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as their relevance to the objectives of this review. A manual search of these selected manuscripts was carried out to identify potentially relevant references to include, generating five additional articles to be analyzed in full text. Only two of these references met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, along with 18 of the original 117 papers reviewed. The reasons for exclusion after full text analysis are outlined in Table 1. Following this process, total of 20 papers were selected to be included in this systematic review.

Summary of papers excluded on full text review.

| Papers excluded on full text review | Number of papers excluded | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for exclusion | EBSCO 2000–2010 | EBSCO 2011–2020 | PubMed | Embase | |

| Not within the remit of review: factors of implementation, reporting of perinatal mortality, risk factors for perinatal death, focused on perinatal audit processes and outcomes | 21 | 15 | 1 | 14 | 51 |

| Focus on low-income countries/low resource settings | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| Study design or article type: e.g. conference/meeting notes, editorials, protocols | 9 | 8 | 0 | 13 | 30 |

| Articles unavailable in English, Spanish, Portuguese | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Duplicates | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Total | 37 | 32 | 2 | 30 | 102a |

-

aOne paper was manually extracted, outside of the database searches, and excluded due to not aligning with aims of rev.

Quality appraisal of studies

The CASP Critical Appraisal Tools for Case Control Studies and Qualitative Studies were used to assess the validity of the articles used in this systematic review [37, 38]. For cross-sectional studies, the CASP Case Control Study Checklist was applied, adapting this by removing questions 6a and b which refer specifically to questions regarding the control vs. cases group. All papers selected were considered valid, and therefore included in this review. The papers their strengths and limitations according to the appraisal tool are described in the appendices in the Critical Appraisal Table (Supplementary material, Appendix 1).

Data extraction

Data from the included articles was summarized systematically. The following data was extracted from each article: Study population, Sample Size and Location; Methods including use of external reviewers, barriers recognized in audit implementation, and risk factors identified; Main outcomes relating to the objectives of this review and study limitations. This review focused on preventable or modifiable risk factors, most specifically maternal factors or factors associated with clinical care. Risk factors associated with fetal causes of death were not included in data extraction. A narrative summary was carried out and data synthesis tables (Tables 2, 3, and 4) completed to present the main characteristics and findings from the studies included.

Overview of characteristics and methods of included studies.

| Study number | Author, year, title | Study design, location, sample size, population | Methods | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alderliesten et al. 2008. Design and evaluation of a perinatal audit |

Perinatal audit The Netherlands n=137 All cases of fetal mortality >16 weeks gestation and neonatal deaths that occurred during Feb–Oct 1999 |

Standardised audit and audit review to establish cause of death, Substandard Care Factors (SSCFs). Questionnaire distributed to audit members to investigate their opinion of the audit process. Anonymous narrative abstract from case records analysed. |

|

| 2 | Amaral et al. 2011. A population-based surveillance study on severe acute maternal morbidity (near-miss) and outcomes in Campinas, Brazil: The Vigimoma Project. |

Retrospective descriptive audit study Campinas, Brazil All cases of maternal morbidity/near-miss, maternal deaths, and perinatal deaths in Campinas from Oct to Dec 2005 (n=159 adverse perinatal events; 60 Perinatal Deaths). Total births Oct–Dec 2005 (4,491 live births) |

Cases collected in nine maternity services from medical and administrative records compared to defined standards, supervised by research personnel, and discussed anonymously by Municipal Committee on Maternal Mortality or Regional Health Directorate Committee. Preventability Scores assigned. |

|

| 3 | Dahl et al. 2000. Antenatal, neonatal and post neonatal deaths evaluated by medical audit. A population-based study in northern Norway – 1979–1997. |

Retrospective (1976–1983) and Prospective (1983–1997) Perinatal Audit Troms County, Northern Norway n=190 (1976–1983), 282 (1984–1997) antenatal, neonatal and postnatal deaths. All antenatal, neonatal, postnatal deaths |

Anonymized medical records for antenatal, neonatal and post neonatal deaths ≥20 weeks from retrospective data 1976–1983, and prospectively 1984–1997. Medical Birth Registry used to obtain total born, and birthweight (BW) and gestational age (GA) subgroups. |

|

| 4 | De Lange et al. 2008. Avoidable risk factors in perinatal deaths: A perinatal audit in South Australia |

Perinatal audit South Australia n=608 All PNM in South Australia from 2001 to 2005 |

PNM summaries from South Australian Pregnancy Outcome Unit reviewed by Maternal, Perinatal and Infant Mortality Committee. |

|

| 5 | De Reu et al. 2009. The Dutch Perinatal Audit Project: a feasibility study for nationwide perinatal audit in the Netherlands |

Retrospective perinatal audit n=228 All cases of PNM in three regions in the Netherlands in a one-year period (2003–2004) |

Reporting of PNM via case report form by all professionals involved in perinatal care. Audit groups formed anonymous narratives and case documents. six audit groups classified cause of death, SSCFs and relation between the two. National Dutch perinatal database (PRN), hospital admin, checked for missed cases of PNM. |

|

| 6 | Eskes et al. 2014. Term perinatal mortality audit in the Netherlands 2010–2012: a population-based cohort study |

Perinatal audit, Population based cohort study The Netherland n=943 registered PNM, n=707 audited PNM All perinatal deaths that occurred in the Netherlands during the period 2010–2012 |

Audit reviewers received training in audit process and PNM classification. Audit meetings were held to review cases NS identify cases of SSCF. SSCF was defined as deviation national guidelines, local protocols, or normal professional practice. Two real time databases were created to support the audit (Perinatal Audit Registry of The Netherlands (PRN-Audit) and Perinatal Audit Registry System (PARS). Audit narrative and supplemental data are provided on PRN-Audit. Audit meetings and outcomes are registered on PARS. |

|

| 7 | Flenady et al. 2010. Uptake of the PSANZ perinatal mortality audit guideline |

Cross-sectional qualitative survey study Australia and New Zealand n=133 lead midwives and doctors working in birthing suites of 78 maternity hospitals with >1,000 births/year in Australia and New Zealand. |

Anonymous telephone Likert style survey regarding Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand (PSANZ) guidelines. The lead doctor and midwife on duty at the time of the telephone call were interviewed and responses were recorded into data entry sheets. |

|

| 8 | Kapurubandara et al. 2017. A perinatal review of singleton stillbirths in an Australian metropolitan tertiary centre |

Retrospective case series audit Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia n=215 singleton stillbirths 28,109 singleton deliveries recorded at hospital (2005–2010) |

All cases of singleton stillbirths from hospital database between 2005 and 2010 retrospectively reviewed. Cases reviewed according to PSANZ PNM audit guidelines by team of maternal fetal medicine specialists. |

|

| 9 | Kieltyka et al. 2012 Louisiana Implementation of the National Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (NFIMR) Program Model: Successes and Opportunities. |

Commentary/Descriptive Review Louisiana, United States Louisiana’s Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (LaFIMR) processes. |

Descriptive review of the implementation of the statewide LaFIMR and changes made from the NFIMR program guide. |

|

| 10 | Kortekaas et al. 2018. Perinatal death beyond 41 weeks pregnancy: an evaluation of causes and substandard care factors as identified in perinatal audit in the Netherlands |

Quantitative Descriptive Study The Netherlands n=947 term PNM 479,097 total term and post-term deliveries |

Cases of term PNM (≥37 weeks) registered on Perinatal Audit Registry of Netherlands (PARS) selected for local audit. Assessed quality of care, SSCFs, cause of death with Wigglesworth classification, cause of death using ReCoDe. |

|

| 11 | Lee et al. 2014. Understanding Perinatal Death: A Systematic Analysis of New York City Fetal and Neonatal Death Vital Record Data and Implications for Improvement, 2007–2011. |

Retrospective perinatal audit New York, United States n=2,665, n=1930 fetal deaths, n=735 neonatal deaths All third trimester fetal and neonatal deaths in New York City from 2007 to 2011 |

Data of all live births, fetal and neonatal deaths provided by clinical and administrative staff in medical facilities in NYC. Healthcare providers classified cause of death based on WHO ICD-10 codes. Failure to meet set criteria defined fetal death registrations as incomplete. Ill-defined causes of death were defined as unspecified causes of death, or cases identified as extreme prematurity or prematurity. |

|

| 12 | McNamara, O’Donoghue, and Greene 2018. Intrapartum fetal deaths and unexpected neonatal deaths in the Republic of Ireland: 2011–2014; a descriptive study. |

Descriptive Analysis of Perinatal Mortality Audit Ireland n=81 intrapartum fetal deaths, 36 unexpected neonatal deaths 282,829 total births |

Data on intrapartum deaths and unexpected neonatal deaths (>34 weeks gestation or BW>2,500 g) from National Perinatal Epidemiology Centre (NPEC) PNA data from 2011 to 2014 analysed. NPEC collects national perinatal mortality data through a standardized notification system. |

|

| 13 | Misra et al. 2004. The Nationwide Evaluation of Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (FIMR) Programs: Development and Implementation of Recommendations and Conduct of Essential Maternal and Child Health Services by FIMR Programs |

Cross-sectional qualitative quantitative analysis of fetal and infant mortality review (FIMR) programs United States n=74 (84% total population) Total of 88 FIMR programs eligible for inclusion in study United States |

Telephone interviews with FIMR program directors analysed function and output of programs. Data on development and implementation of recommendations based on data from FIMR programs. Quantitative analyses of differences in outcomes of various FIMR programs. |

|

| 14 | Po’ G, et al. 2019. A regional audit system for stillbirth: a way to better understand the phenomenon |

Regional Perinatal Audit Emilia-Romagna Region, Italy. n=332 stillbirths 107,528 total births (2014–2016) |

All stillbirth cases evaluated according to specifically designed diagnostic protocol in six local audits of one region. Data collection and review by Multidisciplinary team (MDT) twice a year. |

|

| 15 | Richardus et al., Differences in perinatal mortality and suboptimal care between 10 European regions: results of an international audit (2003) Suboptimal care and perinatal mortality in 10 European regions: methodology and evaluation of an international audit (2003) |

Retrospective perinatal audit, Europe (EuroNatal study) n=1,619 Regions in 10 European countries selected that would be representative of population of that country. 60% of all cases of PNM in the regions audited between 1993 and 1998. |

International audit panel with members from 12 EU countries examined PNM cases at >28 week that fall within category II, III, V, X and XI of the Nordic-Baltic Perinatal Death Classification system were analysed. Standards of care based on international guidelines/review of literature/best-practice consensus agreed by panel members. Suboptimal care defined by grading system adapted from CESDI123 duplicate cases included to assess intra- and inter-panel validity. |

|

| 16 | Robertson et al. 2017. Each baby counts: National quality improvement programme to reduce intrapartum-related deaths and brain injuries in term babies |

Review article of Each Baby Counts (EBC) Project, a prospective national perinatal audit UK n=921 All intrapartum, early neonatal deaths and infants with severe brain injury from January to December 2015 |

Eligible babies registered and case summaries uploaded to online database. Case summaries reviewed by two EBC-trained reviewers to examine: whether information was sufficient; whether different clinical care would have resulted in different outcome. |

|

| 17 | Rodin et al. 2015. Perinatal Health Statistics as the Basis for Perinatal Quality Assessment in Croatia. |

Retrospective Audit Study Croatia n=4,633 perinatal deaths ≥22 weeks 587,356 total births ≥22 weeks |

Assessed perinatal health indicators and outcomes from perinatal hospital data collected by Croatian Institute of Public Health (CIPH) between 2001 and 2014 after the implementation of new reporting system according to WHO recommendations |

|

| 18 | Van Diem et al. 2012. The implementation of unit-based perinatal mortality audit in perinatal cooperation units in the northern region of the Netherlands. |

Perinatal Audit (Observational study) The Netherlands (Northern Region) n=15 perinatal cooperation units, n=112 perinatal deaths All 15 perinatal cooperation units and all their cases of PNM between Sept. 2007 and Mar. 2010. 1,026 questionnaires with Audit Participants Feedback |

Unit-based audits implemented in 15 units. Multidisciplinary core group and external confidential audit committees formed. Cases were identified by the core committee as they occurred. Anonymous narratives for audit meetings formulated. Data from attendance list and questionnaire collected from participants of audit. |

|

| 19 | Wolleswinkel et al. 2002. Substandard care factors in perinatal care in the Netherlands: a regional audit of perinatal deaths. |

Retrospective Regional Perinatal audit The Netherlands n=332 All PNM occurring in region in the Netherlands |

Cases of PNM identified through hospital and midwifery records. Expert MDT panel defined audit criteria; panel members noted deviations from the standard of care criteria and their relationship with perinatal death on a score sheet. 27 cases reviewed by both subpanels to study inter-subpanel agreement. 164 “high risk” cases analysed by both Dutch and European panels. |

|

-

CESDI, Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy; EBC, Each Baby Counts; FIMR, Fetal and Infant Mortality Review; LaFIMR, Louisiana Fetal and Infant Mortality Review; MDT, Multidisciplinary Team; NFIMR, National Fetal and Infant Mortality Review; NPEC, National Perinatal Epidemiology Centre; PARS, Perinatal Audit Registry of Netherlands; PNM, Perinatal Mortality; PMR, Perinatal Mortality Rate; PNA, Perinatal Audit; PSANZ, Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand; SSCF, Substandard Care Factors.

Factors affecting the implementation of PNM audits and the reporting of PNMs as reported in the included studies.

| Study number | Author, year, title | Factors affecting the implementation of PNM audits | Factors affecting reporting of PNMs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alderliesten et al. 2008 [17]. Design and evaluation of a perinatal audit |

Facilitators:

|

– |

| 2 | Amaral et al. 2011 [22]. A population-based surveillance study on severe acute maternal morbidity (near-miss) and outcomes in Campinas, Brazil: The Vigimoma Project. |

Facilitators:

|

– |

| 4 | De Lange et al. 2008 [16]. Avoidable risk factors in perinatal deaths: A perinatal audit in South Australia |

– | Barriers:

|

| 5 | De Reu et al. 2009 [28]. The Dutch Perinatal Audit Project: a feasibility study for nationwide perinatal audit in the Netherlands |

Barriers:

|

Facilitators:

|

| 6 | Eskes et al. 2014 [31]. Term perinatal mortality audit in the Netherlands 2010–2012: a population-based cohort study |

Facilitators:

|

Barriers:

|

| 7 | Flenady et al. 2010 [41]. Uptake of the PSANZ perinatal mortality audit guideline |

Facilitators:

|

Barriers:

|

| 8 | Kapurubandara et al. 2017 [21]. A perinatal review of singleton stillbirths in an Australian metropolitan tertiary centre |

Barriers:

|

Barriers:

|

| 9 | Kieltyka et al. 2012 [40]. Louisiana Implementation of the National Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (NFIMR) Program Model: Successes and Opportunities. |

Facilitators:

|

Facilitators:

|

| 11 | Lee et al. 2014 [33]. Understanding Perinatal Death: A Systematic Analysis of New York City Fetal and Neonatal Death Vital Record Data and Implications for Improvement, 2007–2011. |

– | Barriers:

|

| 12 | McNamara, O’Donoghue, and Greene 2018 [24]. Intrapartum fetal deaths and unexpected neonatal deaths in the Republic of Ireland: 2011–2014; a descriptive study. |

– | Facilitators:

|

| 13 | Misra et al. 2004 [32]. The Nationwide Evaluation of Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (FIMR) Programs: Development and Implementation of Recommendations and Conduct of Essential Maternal and Child Health Services by FIMR Programs |

– | Facilitators:

|

| 14 | Po’ G et al. 2019 [23]. A regional audit system for stillbirth: a way to better understand the phenomenon |

Barriers:

|

Barriers:

|

| 15 | Richardus et al., Differences in perinatal mortality and suboptimal care between 10 European regions: results of an international audit (2003) [18] Suboptimal care and perinatal mortality in 10 European regions: methodology and evaluation of an international audit (2003) [19] |

Barriers:

|

Facilitators:

|

| 16 | Robertson et al. 2017 [39]. Each baby counts: National quality improvement programme to reduce intrapartum-related deaths and brain injuries in term babies |

– | Facilitators:

|

| 17 | Rodin et al. 2015 [26]. Perinatal Health Statistics as the Basis for Perinatal Quality Assessment in Croatia. |

Barriers:

|

Facilitators:

|

| 18 | Van Diem, et al. 2012 [7]. The implementation of unit-based perinatal mortality audit in perinatal cooperation units in the northern region of the Netherlands. |

Facilitators: From Audit Participants Feedback:

|

– |

| 19 | Wolleswinkel et al. 2002 [20]. Substandard care factors in perinatal care in the Netherlands: a regional audit of perinatal deaths. |

Barriers:

|

Facilitators:

|

-

CAT, Community Action Team; CRT, Case Review Team; FIMR, Fetal and Infant Mortality Review; MDT, Multidisciplinary Team; NFIMR, Fetal and Infant Mortality Review; PNM, perinatal mortality; PNA, perinatal audit; SSCF, substandard care factors; TOP, termination of pregnancy.

Risk factors identified and outcomes of perinatal audits.

| Study number | Author, year, title | Study design, location, sample size, population | Risk factors associated with perinatal outcomes identified | Recommendations and outcomes of implementation of a PNM audit or reporting program |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alderliesten et al. 2008 [17]. Design and evaluation of a perinatal audit |

Perinatal audit The Netherlands n=137 All cases of fetal mortality >16 weeks gestation and neonatal deaths that occurred during Feb-Oct 1999 |

Care factors:

|

Recommendations:

|

| 2 | Amaral et al. 2011 [22]. A population-based surveillance study on severe acute maternal morbidity (near-miss) and outcomes in Campinas, Brazil: The Vigimoma Project. |

Retrospective descriptive audit study Campinas, Brazil All cases of maternal morbidity/near-miss, maternal deaths, and perinatal deaths in Campinas from Oct to Dec 2005. (n=159 adverse perinatal events; 60 Perinatal Deaths). Total births Oct–Dec 2005 (4,491 live births) |

Maternal factors:

|

Recommendations:

|

| 3 | Dahl et al. 2000 [27]. Antenatal, neonatal and post neonatal deaths evaluated by medical audit. A population-based study in northern Norway – 1979–1997. |

Retrospective (1976–1983) and Prospective (1983–1997) Perinatal Audit Troms County, Northern Norway n=190 (1976–1983), 282 (1984–1997) antenatal, neonatal and postnatal deaths All antenatal, neonatal, postnatal deaths |

Maternal Factors:

|

– |

| 4 | De Lange et al. 2008 [16]. Avoidable risk factors in perinatal deaths: A perinatal audit in South Australia |

Perinatal audit South Australia n=608 All PNM in South Australia from 2001 to 2005 |

Maternal factors:

|

Recommendations:

|

| 5 | De Reu et al. 2009 [28]. The Dutch Perinatal Audit Project: a feasibility study for nationwide perinatal audit in the Netherlands |

Retrospective perinatal audit n=228 All cases of PNM in 3 regions in the Netherlands in a one-year period (2003–2004) |

Maternal factors:

|

Outcomes:

|

| 6 | Eskes et al. 2014 [31]. Term perinatal mortality audit in the Netherlands 2010–2012: a population-based cohort study |

Perinatal audit, Population based cohort study The Netherland n=943 registered perinatal deaths, n=707 audited perinatal deaths. All perinatal deaths that occurred in the Netherlands during the period 2010-2012 |

Care factors:

|

Recommendations:

|

| 7 | Flenady et al. 2010 [41]. Uptake of the PSANZ perinatal mortality audit guideline |

Cross-sectional qualitative survey study Australia and New Zealand n=133 lead midwives and doctors working in birthing suites of 78 maternity hospitals with > 1,000 births/year in Australia and New Zealand. |

– | Recommendations:

|

| 8 | Kapurubandara et al. 2017 [21]. A perinatal review of singleton stillbirths in an Australian metropolitan tertiary centre |

Retrospective case series audit Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia n=215 singleton stillbirths 28,109 singleton deliveries recorded at hospital (2005–2010) |

Maternal factors:

|

Outcomes:

|

| 9 | Kieltyka et al. 2012 [40]. Louisiana Implementation of the National Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (NFIMR) Program Model: Successes and Opportunities. |

Commentary/Descriptive Review Louisiana, United States Louisiana’s Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (LaFIMR) processes. |

– | Outcomes:

|

| 10 | Kortekaas et al. 2018 [25]. Perinatal death beyond 41 weeks pregnancy: an evaluation of causes and substandard care factors as identified in perinatal audit in the Netherlands |

Quantitative Descriptive Study The Netherlands n=947 term perinatal deaths 479,097 total term and post-term deliveries |

Maternal factors:

|

Recommendations:

|

| 11 | Lee et al. 2014 [33]. Understanding Perinatal Death: A Systematic Analysis of New York City Fetal and Neonatal Death Vital Record Data and Implications for Improvement, 2007–2011. |

Retrospective perinatal audit New York, United States n=2,665, n=1,930 FDs, n=735 neonatal deaths All third trimester fetal and neonatal deaths in New York City from 2007 to 2011 |

– | Recommendations:

|

| 12 | McNamara, O’Donoghue, and Greene 2018 [24]. Intrapartum fetal deaths and unexpected neonatal deaths in the Republic of Ireland: 2011–2014; a descriptive study. |

Descriptive Analysis of Perinatal Mortality Audit Ireland n=81 intrapartum fetal deaths, 36 unexpected neonatal deaths 282,829 total births |

Maternal factors:

|

Recommendations:

|

| 13 | Misra et al. 2004 [32]. The Nationwide Evaluation of Fetal and Infant Mortality Review (FIMR) Programs: Development and Implementation of Recommendations and Conduct of Essential Maternal and Child Health Services by FIMR Programs |

Cross-sectional qualitative quantitative analysis of fetal and infant mortality review (FIMR) programs United States n=74 (84% total population) Total of 88 FIMR programs eligible for inclusion in study United States |

– | Recommendations:

|

| 14 | Po’ G, et al. 2019 [23]. A regional audit system for stillbirth: a way to better understand the phenomenon |

Regional Perinatal Audit Emilia-Romagna Region, Italy. n=332 stillbirths 107,528 total births (2014–2016) |

Maternal factors:

|

Outcomes:

|

| 15 | Richardus et al., Differences in perinatal mortality and suboptimal care between 10 European regions: results of an international audit (2003) [18] Suboptimal care and perinatal mortality in 10 European regions: methodology and evaluation of an international audit (2003) [19] |

Retrospective perinatal audit, Europe (EuroNatal study) n=1,619 Regions in 10 European countries selected that would be representative of population of that country. 60% of all cases of PNM in the regions audited between 1993 and 1998. |

Maternal factors:

|

– |

| 16 | Robertson et al. 2017 [39]. Each baby counts: National quality improvement programme to reduce intrapartum-related deaths and brain injuries in term babies |

Review article of Each Baby Counts (EBC) Project, a prospective national perinatal audit UK n=921 All intrapartum, early neonatal deaths and infants with severe brain injury from January to December 2015 |

– | Recommendations: Of the 150 local reviews with sufficient information:

|

| 17 | Rodin et al. 2015 [26]. Perinatal Health Statistics as the Basis for Perinatal Quality Assessment in Croatia. |

Retrospective Audit Study Croatia n=4,633 perinatal deaths ≥22 weeks 587,356 total births ≥22 weeks |

Care factors: Although no specific association analysis was carried out, the study outlines the following care factors:

|

Outcomes:

|

| 18 | Van Diem et al. 2012 [7]. The implementation of unit-based perinatal mortality audit in perinatal cooperation units in the northern region of the Netherlands. |

Perinatal Audit (Observational study) The Netherlands (Northern Region) n=15 perinatal cooperation units, n=112 perinatal deaths. All 15 perinatal cooperation units and all their cases of PNM between Sept. 2007 and Mar. 2010. 1,026 questionnaires with Audit Participants Feedback |

Care factors:

|

Recommendations: Actions identified to improve care:

|

| 19 | Wolleswinkel et al. 2002 [20]. Substandard care factors in perinatal care in the Netherlands: a regional audit of perinatal deaths. |

Retrospective Regional Perinatal audit The Netherlands n=332 All PNM occurring in region in the Netherlands |

Care factors:

|

Recommendations:

|

-

AOR, assisted reproductive technology; BW, birthweight; CAT, community action team; CRT, case review team; EBC, every baby counts; END, early neonatal death; FD, fetal death; FIMR, fetal and infant mortality review; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; IVF, In-vitro fertilization; MDT, multidisciplinary team; NFIMR, fetal and infant mortality review; PNM, perinatal mortality; PPS, preventability score; RF, risk factor; SSCF, substandard care factors.

Results

In total, 20 papers met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. However, two articles [18, 19] referred to the same study and reported on the same data. To avoid duplication these were combined and findings of the two papers were reported as one entry (study number 15).

The main characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1. The year of publication of the included studies ranged from 2000 to 2018. Articles originated from the Netherlands (n=6), Norway (n=1), Ireland (n=1), Italy (n=1), United Kingdom (n=1), Croatia (n=1), Brazil (n=1), Australia (n=2), New Zealand (n=1) and the United States (n=3). Five studies were qualitative in design, while the remaining 14 were quantitative. The countries from which the articles originated from is depicted in Supplemental Material, Appendix 2. The main methods involved regional [7, 16, 17, 20], [21], [22], [23, 27, 28, 33], national [24], [25], [26, 31, 32, 39] and European [18, 19] perinatal audits, retrospective audits [16, 20], [21], [22, 26], [27], [28, 33] and descriptive audit studies [7, 16, 17, 23], [24], [25, 27, 31, 32, 39], [40], [41]. Following critical appraisal, the quality of studies was deemed to be good, overall. The quality of four studies, in total, was determined to be fair as issues were observed in the completeness of datasets [16, 25], and in the data collection methodology [22, 40]. Further detail on the quality appraisal of the studies is available in Supplementary material, Appendix 1.

Fourteen studies described factors affecting reporting of PNM [16, 18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 28, 31], [32], [33, 39], [40], [41] and twelve studies reported on factors affecting the implementation of PNM audits [7, 17, 18, 20], [21], [22], [23, 26, 28, 39], [40], [41]. Fourteen studies focused on risk factors associated with perinatal outcomes [7, 16], [17], [18, 20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28, 31] and seventeen presented information on audit recommendations and/or outcomes of implementation of a PNM audit or reporting program [7, 16, 17, 20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26, 28, 31], [32], [33, 39], [40], [41].

Factors affecting the reporting of PNM in audit

Factors affecting completeness and standardisation of data

The lack of standardised reporting criteria or clearly established definitions was mentioned in four studies [19, 21, 24, 26]. Differences in reporting, classifications and criteria used were issues raised in these studies which hampered the adequate and reliable reporting of perinatal mortalities in the context of audit. Three studies mentioned the need for a standardized tool to facilitate the process of reporting data [33, 39, 41]. One study noted that 27% of reports did not have enough information to classify the cause of death, and that 24% of reports were incomplete at the time of data collection [26].

In a perinatal audit of intrapartum fetal deaths and unexpected neonatal deaths by McNamara et al. [24], a lack of standardisation in the reporting of placental histology was noted and a significant variation in the details of reports was observed.

Other factors that were found to affect the quality of perinatal audits include multidisciplinary input in the formulation of case summaries [28, 31, 39], staff training and capacity [7, 31, 33, 41], standardisation of audit methodology and adequate adaptation of audit procedures and guidelines to different regions or states [26, 28, 40]. One study found that clinicians needed better guidance with regards to investigating PNM (79%) and 65% of respondents to the same survey expressed that their hospitals needed better systems for collecting data and reporting PNM [41].

Additionally, three studies [18, 20, 23] reviewed the reproducibility of their results by examining consensus between subpanels of the review process in determining relation of SSCF to adverse perinatal outcome. In two of these studies, consensus was good, (kappa coefficient 0.62–0.74) [18, 20] whereas in the remaining study, there was disagreement on determining cause of death in 16.4% of cases [23].

Factors affecting case ascertainment

The lack of linkage of medical and civil records has been mentioned as a factor affecting PNM reporting as it can allow for better and more accurate case identification. Two studies found underreporting of events through hospital systems or audit programs compared to registries or databases [26, 28]. De Reu et al. [28] specifically noted 20% of cases from the PNM database had not been reported in the audit. Kieltyka et al. [40] found that timeliness of capturing cases through civil records could affect the representation of cases being sampled in the audit process.

Barriers to PNM audit implementation

Time

Five studies [7, 17, 22, 23, 28] found that the time commitment associated with the audit process was obstructive to its implementation. The average time required to prepare cases for audit meetings varied between 4 and 8 h and frequent, time-consuming meetings were identified as a potential barrier to audit implementation.

Insufficient or incomplete data

Incomplete data in cases of PNM was noted to affect data collection for audit purposes in nine studies [17, 18, 20, 21, 26, 28, 31, 33, 39]. The proportion of incomplete data were variable, ranging from 3 to 34%. Two studies [26, 28] showed that differences in data acquisition methods between civil and medical records resulted in insufficient data for perinatal audit. In one study [20], data could not be obtained from civil records due to confidentiality laws.

Staff training

Four studies [7, 31, 32, 41] identified inadequate training in the processes of auditing as a factor which impeded their effective implementation or as a necessary factor that would improve implementation. Two studies [28, 32] showed that staff training in identifying cases of substandard care and how to implement recommendations from audit, improves outcomes in each of these domains, respectively.

Other barriers

Other factors that were found to affect the implementation of perinatal audits include personal involvement of the clinician in cases [17], lack of consensus between audit review members in determining outcomes in cases of perinatal mortality [18], poor compliance with pre-existing audit guidelines [21] and absence of standardisation of case definition for international comparison [19, 26]. Surprisingly, only two studies positively identified funding as a barrier to implementation of a regional/national audit system [7, 28].

Facilitators to PNM audit implementation

In a survey of perinatal mortality audit participants, 10% indicated they valued training given in the audit process, a non-judgmental environment to search for SSCFs (21%) and the multidisciplinary team approach (13%) [7]. Another study found similar results, where 100% of members felt secure discussing cases openly with other care providers [17]. Similarly, in a study by Flenady et al. [41], survey respondents valued the use of checklists and information brochures, which aided investigation and standardisation in cases of perinatal mortality.

Recognition of risk factors associated with perinatal outcomes

In total, 12 papers identified risk factors for perinatal mortality through perinatal audit [16], [17], [18, 20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25, 27, 28, 31]. These findings are presented in Table 3. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and maternal obesity were the two most commonly identified maternal factors associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Failure of timely detection of fetal growth restriction (FGR) and appropriate management [16, 19, 20, 23, 24], late presentation or failure of transfer to higher level of care [21, 23, 28], and failure to diagnose/manage diabetes/hypertensive disorders in pregnancy [20, 23] were commonly identified SSCF associated with perinatal mortality. Seven of these studies analysed the relation of SSCF to perinatal mortality [17, 19, 20, 23, 25, 28, 31]. The proportion of SSCF that possibly or likely contributed to perinatal mortality was variable, ranging from 8 to 45%. Alderliesten et al. found SSCFs in 25% of PNM cases, with 8% of deaths possibly related to the SSCF in question [17]. This is comparable to findings from Kortekaas et al. who reported in 35.4% of cases of PNM, SSCFs were possibly, likely or very likely related to the death [25].

A perinatal audit in South Australia found 11.2% of SSCFs occurred due to deficiencies of professional care, and differences in the quality of perinatal care present in different types of hospitals, with country (regional) and level 1(primary care/midwifery led) hospitals having the most prevalent SSCFs [16]. De Reu et al. [28] found that in 32% of cases with SSCFs, failure to transfer to tertiary care contributed to cause of death compared to 25% of cases where the underlying cause was potentially related to night or late evening shifts. In another study in the Netherlands, the inability to follow guidelines (31% of identified SSCFs), provision of care against normal practice (23%) and inadequate communication between clinicians (13%) were the most common SSCFs [20]. Similarly, in an internal audit in the Netherlands, 35% of cases with SSCFs were associated with noncompliance or missing local protocols and 41% with deviation from normal care [31].

Outcomes following implementation of a perinatal audit

Seventeen papers reported on the outcomes or recommendations following the implementation of perinatal audits (Table 3). Following the results of two regional audits in the Netherlands, a nationwide perinatal audit was initiated [7, 28]. This was facilitated by the creation of a perinatal mortality database, which helped with the standardisation and completeness of data collection. Similarly, following the application of an online reporting system in another regional audit by Lee et al. [33], there was an improvement in the quality of fetal death reports and a reduction in poorly defined causes of fetal death (61% vs. 68%, p=0.004). In Australia, a local perinatal review process was implemented after the results of one study in this region [21].

Overall, there is a lack of clear information on whether recommendations from perinatal audits have been implemented or not. Only five studies provided further detail on this [21, 28, 31, 32, 40]. Mishra et al. [32] analysed the proportion of recommendations implemented after the initiation of a fetal death monitoring program. They found a high rate (75%) of implementation of 231 recommendations, with a further 22% in the process of being implemented at the time of publication. Additionally, Kieltyka reported that nine public health programs were implemented in specific regions across the state of Louisiana [40].

Following an audit of 707 cases of PNM in the Netherlands, a total of 603 recommendations were made based on the identification of 512 SSCFs in 376 cases [31]. The majority of recommendations (35%) related to the organisation of care, in particular the co-operation of care between healthcare professionals in the community and in hospitals. The same audit found that over a 3-year period, the PMR decreased from 2.3/1,000 to 2/1,000 (p≤0.001).

Recommendations for audit implementation

Eight studies made recommendations for improvement of the audit process and implementation of audits on either a local or national level [16, 17, 24, 25, 31, 33, 39, 41]. Audit member training was an important recommendation which was suggested by De Lange [16], Eskes [31] and Flenady [41]. This was recommended specifically in the areas of investigation and classification of perinatal mortality.

Studies also recommended multidisciplinary participation in the analyses of PNM cases, as this was found to improve the quality of case summaries and the overall audit process [17, 28, 41]. Furthermore, the implementation of a national confidential enquiry for all cases of intrapartum fetal deaths and unexpected neonatal deaths was recommended by McNamara et al. [24].

Two studies in total recommended the use of an audit tool to help with standardisation of analysis in cases of perinatal mortality [25, 39]. Both studies commented on the need for a standard case summary tool to aid in the quality and completeness of data in cases of PNM.

Recommendations for clinical practice

Recommendations for clinical practice were made in seven studies which reflected, mostly, on the identification of risk factors and substandard care factors described in their results.

Patient or public education regarding concerning symptoms in late pregnancy [16, 22] and smoking cessation in pregnancy or other maternal risk factors [24] were the most common patient-focused recommendations made.

Discussion

The current systematic review aimed to study with further depth the main challenges faced by PNM audits and facilitating factors contributing to efficient and successful PNM audit implementation. The main factors affecting the correct and reliable reporting of perinatal deaths in PNM audits were also studied. Lastly, this review intended to clearly understand the relevance and potential impact of PNM audits in identifying risk factors and recommending and (perhaps) implementing measures for improvement of quality of care. To our knowledge this is one of the first systematic reviews examining this field of Perinatal Mortality Audit with this level of detail.

The nineteen studies analysed in our review highlighted common barriers to the implementation of perinatal audits and, upon further analysis of the literature, these barriers appear to resonate with clinical audit in general. Although our review is comprehensive and includes all published literature found in the respective databases that met our inclusion criteria, it is noted that national perinatal mortality data from some countries is not included in our review, as some national reports have not been submitted to peer-reviewed journals and therefore did not meet our inclusion criteria.

Standardisation of data collection, cause of death and case definitions

The results of this review revealed that there is a lack of consistency in the methods used to collect data on perinatal mortality and associated factors, definitions used for cases of perinatal death, and classifications of associated factors. This affects the completeness of data being collected, as seen in several studies [17, 18, 20, 21, 26, 28, 31, 33, 39]. Consequently, this impacts on the ability to use these data for identification of risk and substandard-care factors, classifying causes of death and tracking trends in perinatal mortality for improvements. Guidelines set forth by multiple national and international organizations [42], [43], [44] emphasise the importance of a structured, standardized approach to clinical audits procedures and data collection. However, our results show there are still areas where further standardization is necessary.

The use of a standardized collection system or tool has been established in several high-income countries with national perinatal audits, including the U.K., Ireland and New Zealand [45], [46], [47]. This is known to facilitate the collection of pertinent data of each reported perinatal death case, especially in high volume, fast paced environments where capturing data can be a challenge [43]. In the U.K., a validated Perinatal Mortality Review tool is also used to guide the review of perinatal death cases in a standardized manner. A report on the use of this tool stated that it has been used in the review of 88% of eligible PNM cases across England, Scotland and Wales, and over 90% of these resulted in the identification of a substandard care factor [48]. Standardization of data collection has been recommended in other mortality audit guidelines, such as the WHO’s guide for paediatric mortality auditing [49].

In this review, studies identified a lack of established reporting criteria or definitions as a barrier to reporting perinatal deaths [21, 24, 26, 31, 41]. Different hospital systems, regions or countries using distinct perinatal mortality definitions hinders the comparison of perinatal mortality rates between countries. This hampers tracking trends in rates, rates across countries and learning from each other’s successes [12, 34]. The WHO’s definition is recommended for international comparisons, but many countries use their own definitions, with different gestational age and/or birth weight cut-offs, and differing inclusion criteria for termination of pregnancy [43]. The Lancet Stillbirth Series has emphasised that international consensus on the classification and definition of stillbirth is essential to improve care through national audits in high income countries [50].

Rodin et al.’s [26] study in this review showed how lack of data from the audit impeded the ability to classify cause of death. Lehner et al. [51] also reported that the use of a standard audit tool resulted in the identification of underlying causes of death in 168/170 stillbirth deaths originally classified as unexplained through chart review. Similarly, Allanson et al., highlighted the benefits and applicability of a standard reporting and classification system while Vergani et al. showed that applying a standard classification tool lead to a reduction of the rate of unexplained stillbirth [52, 53]. Though the global lack of quality data and poor reporting on stillbirths’ cause of death is recognised and a standardised audit and classification system has been proposed [54], there is currently no international consensus on one system to apply. Although various studies have compared classification systems, establishing which would be best recommended, there is still lack of agreement and a need for a consistent system which allows for accurate comparison [52, 55, 56].

Factors affecting the implementation of PNM audits

Lack of protected audit time, dedicated staff training, and incomplete or insufficient data were cited as the most common barriers to perinatal audit implementation in our review. Lack of resources is one of the age-old barriers to clinical audit and has been quoted extensively as a limiting factor in the development of regular, clinical audits [57], [58], [59]. Given the already burdened and time limited workload at most clinical sites, some clinicians feel that the time required to partake in audit impedes upon their clinical work, ultimately compromising patient care [60]. However, the importance of clinical audits is noted amongst clinicians as a critical identifier of suboptimal care factors and as a quality improvement strategy [30]. In Ireland, the National Perinatal Epidemiology Centre (NPEC) has often highlighted that robust clinical audit of perinatal outcomes is vital for patient care, but this requires the protected time of clinical staff [45, 61]. Improvements in this regard can be difficult to implement on an individual basis and require adjustments on either a local, regional or national level to afford healthcare workers the time to engage with clinical audits. A predetermined amount of protected hours per week for clinical trainees or dedicated research staff may help facilitate regular perinatal audits. The Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) in the United Kingdom have outlined recommendations with regard to time management, to facilitate and promote regular clinical audits [42].

Four of the studies in our review identified inadequate staff training as a barrier to perinatal audit implementation [28, 31, 32]. Staff training is essential for clinical audit to ensure accurate outcomes measurement and of reliable datasets which, as part of the audit cycle, can promote systematic change. Lack of training in perinatal death classification systems amongst audit participants may lead to inaccurate identification in cause of death in these cases, subjecting audit results to potential misclassification bias. However, in two studies [28, 31], even though staff received training in audit processes and classification system, there was a considerable rate of unknown cause of perinatal death using Wigglesworth and Tulip classification systems (32% and 34.6%, respectively). This highlights the importance of training for the audit process and the relevance of adequate methods and approaches to clinician education.

Incomplete datasets were a consistent and significant finding in our results. Although, in most studies the percentage of cases with insufficient data was low, this figure was highly variable, comprising 34% of cases of PNM in one study [39]. HQIP and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) have also highlighted the relevance of data completeness and prepared guidance to promote high quality data acquisition in clinical audits [44, 62]. Awareness of the importance for high quality data in cases of PNM is increasing, however few countries have practiced standardised auditing [63].

Perinatal mortality audits as an important identifier of risk factors for perinatal mortality

Our analysis highlights the utility of perinatal audits in identifying risk factors for mortality and how through careful case analysis and recognition of suboptimal care factors, change can be implemented at a local, regional or national level to improve obstetric care [7, 21, 28, 33]. Although rates of perinatal deaths have fallen significantly in high-income countries in recent decades, suboptimal care still accounts for a proportion of cases and this is devastating for all parents, families and healthcare professionals involved. Failure to thoroughly examine these cases is a major deficiency in a modern healthcare setting, obstructs clinician education and may lead to recurrence of events.

There is widespread acceptance in the literature that it is essential to analyse cases of perinatal mortality to identify potentially reversible risk factors as well as preventing the recurrence of critical mistakes at both local and national system levels [14, 39, 63]. Audit and feedback have been shown to be effective in improving clinical practice and may be more effective than other quality improvement strategies particularly when the audit process is targeted at analysing practices where there is clear evidence linking processes and patient outcomes [64]. In New Zealand, following the introduction of the Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee (PMMRC) in 2007, an 11% reduction in the stillbirth rate was observed [47]. Similarly, the Netherlands achieved the greatest reduction in stillbirth rates following the implementation of the Dutch perinatal mortality audit when compared to 48 other high income countries [31, 63]. The value of national perinatal programmes has been acknowledged, however few high-income countries have implemented nationwide audit policies and fewer still routinely conduct in-depth analysis of substandard care factors, for example by confidential enquiry [34].

Outcomes following implementation of perinatal audits

Few studies in this review commented on whether recommendations based on findings of perinatal audit have been implemented and whether the “audit loop” has been completed. Nevertheless, follow-up on audit recommendations was not a primary objective in most of the studies included. The audit cycle should always be completed by monitoring of implemented strategies and verification of their efficacy [44, 65, 66]. Qualitative analysis by Misra et al. [32] to evaluate intermediate outcomes of fetal and infant mortality review programmes, identified implementation as a critical outcome of audit, but acknowledged that this was a difficult concept to measure, given the lack of well-established measurement scales [32, 67, 68]. Closing or continuing the audit loop is an essential part of the process in order to improve clinical and professional outcomes [69, 70]. Completion of the audit process helps with clinician professional development and is an obligatory component of clinician training in many countries [64]. In a healthcare setting where professionals or services may be underperforming, PNM audits with clear targets and an action plan have been shown to produce a substantial improvement in the quality of perinatal care [71].

Conclusions

This review has highlighted the barriers to successful implementation of PNM audits. While most of the studies analysed were local or regional perinatal audits, they identify changes that need to be brought about at a systematic level in order improve the quality of perinatal audit, and ultimately perinatal care. Heightened awareness of the impact of effective audit on identifying potential areas for clinical improvement is crucial and in order to promote the success and future of PNM audit, particular focus should be applied to enabling adequately trained staff to participate in regular audit that is standardised and thorough.

Finally, greater emphasis should be placed on the final and most important part of the audit process, that is closure of the perinatal audit cycle through regular assessment and re-evaluation of changes and recommendations put forward from the initial audit. Feedback from PNM audits should inform clinical governance, and recommendations from audit should be continually re-evaluated in order to achieve sustained improvement in the quality of obstetric care, achieving the ultimate goal of reducing the number of perinatal deaths.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

References

1. Nuzum, D, Meaney, S, O’Donoghue, K. The impact of stillbirth on consultant obstetrician gynaecologists: a qualitative study. BJOG 2014;121:1020–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12695.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Nuzum, D, Meaney, S, O’Donoghue, K. The impact of stillbirth on bereaved parents: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0191635. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191635.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Heazell, AEPD, Siassakos, DMD, Blencowe, HM, Burden, CMD, Bhutta, ZAP, Cacciatore, JP, et al.. Stillbirths: economic and psychosocial consequences. Lancet 2016;387:604–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00836-3.Search in Google Scholar

4. Burden, C, Bradley, S, Storey, C, Ellis, A, Heazell, AEP, Downe, S, et al.. From grief, guilt pain and stigma to hope and pride – a systematic review and meta-analysis of mixed-method research of the psychosocial impact of stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0800-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Bhutta, ZA, Darmstadt, GL, Haws, RA, Yakoob, MY, Lawn, JE. Delivering interventions to reduce the global burden of stillbirths: improving service supply and community demand. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:S7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-S1-S7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Pattinson, R, Kerber, K, Waiswa, P, Day, LT, Mussell, F, Asiruddin, S, et al.. Perinatal mortality audit: counting, accountability, and overcoming challenges in scaling up in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;107:S113–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. van Diem, MT, Timmer, A, Bergman, KA, Bouman, K, van Egmond, N, Stant, DA, et al.. The implementation of unit-based perinatal mortality audit in perinatal cooperation units in the northern region of The Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:195. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-195.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. de Bernis, L, Kinney, MV, Stones, W, ten Hoope-Bender, P, Vivio, D, Leisher, SH, et al.. Stillbirths: ending preventable deaths by 2030. Lancet 2016;387:703–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00954-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Frøen, JF, Cacciatore, J, McClure, EM, Kuti, O, Jokhio, AH, Islam, M, et al.. Stillbirths: why they matter. Lancet 2011;377:1353–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62232-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. UN-IGME. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2020. New York; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

11. UN-IGME. A Neglected Tragedy: The global burden of stillbirths – UNICEF DATA 2020. New York; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

12. Zeitlin, J, Alexander, S, Barros, H, Blondel, B, Delnord, M, Durox, M, et al.. Perinatal health monitoring through a European lens: eight lessons from the Euro-Peristat report on 2015 births. BJOG 2019;126:1518–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15857.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. EURO-PERISTAT. European perinatal health report; 2015. Available from: https://www.europeristat.com/index.php/reports/european-perinatal-health-report-2015.html.Search in Google Scholar

14. Kerber, KJ, Mathai, M, Lewis, G, Flenady, V, Erwich, JJ, Segun, T, et al.. Counting every stillbirth and neonatal death through mortality audit to improve quality of care for every pregnant woman and her baby. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:S9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-15-s2-s9.Search in Google Scholar

15. World Health Organization. Every Newborn: an action plan to end preventable deaths. Geneva; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

16. De Lange, TE, Budde, MP, Heard, AR, Tucker, G, Kennare, R, Dekker, GA. Avoidable risk factors in perinatal deaths: a perinatal audit in South Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;48:50–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828x.2007.00801.x.Search in Google Scholar

17. Alderliesten, ME, Stronks, K, Bonsel, GJ, Smit, BJ, van Campen, MMJ, van Lith, JMM, et al.. Design and evaluation of a regional perinatal audit. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;137:141–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.06.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Richardus, JH, Graafmans, WC, Verloove-Vanhorick, SP, Mackenbach, JP. Differences in perinatal mortality and suboptimal care between 10 European regions: results of an international audit. BJOG 2003;110:97–105. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.02053.x.Search in Google Scholar

19. Richardus, JH, Graafmans, WC, Bergsjø, P, Lloyd, DJ, Bakketeig, LS, Bannon, EM, et al.. Suboptimal care and perinatal mortality in ten European regions: methodology and evaluation of an international audit. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2003;14:267–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/jmf.14.4.267.276.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Wolleswinkel-van den Bosch, JH, Vredevoogd, CB, Borkent-Polet, M, van Eyck, J, Fetter, WPF, Lagro-Janssen, TLM, et al.. Substandard factors in perinatal care in The Netherlands: a regional audit of perinatal deaths. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2002;81:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/obs.81.1.17.Search in Google Scholar

21. Kapurubandara, S, Melov, SJ, Shalou, ER, Mukerji, M, Yim, S, Rao, U, et al.. A perinatal review of singleton stillbirths in an Australian metropolitan tertiary centre. PLoS One 2017;12:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171829.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Amaral, E, Souza, JP, Surita, F, Luz, AG, Sousa, MH, Cecatti, JG, et al.. A population-based surveillance study on severe acute maternal morbidity (near-miss) and adverse perinatal outcomes in Campinas, Brazil: the Vigimoma Project. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011;11:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-11-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Po, G, Monari, F, Zanni, F, Grandi, G, Lupi, C, Facchinetti, F. A regional audit system for stillbirth: a way to better understand the phenomenon. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:276. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2432-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. McNamara, K, O’Donoghue, K, Greene, RA. Intrapartum fetal deaths and unexpected neonatal deaths in the Republic of Ireland: 2011–2014; a descriptive study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1636-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Kortekaas, JC, Scheuer, AC, de Miranda, E, van Dijk, AE, Keulen, JKJ, Bruinsma, A, et al.. Perinatal death beyond 41 weeks pregnancy: an evaluation of causes and substandard care factors as identified in perinatal audit in The Netherlands. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:380. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1973-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Rodin, U, Filipović-Grčić, B, Đelmiš, J, Glivetić, T, Juras, J, Mustapić, Ž, et al.. Perinatal health statistics as the basis for perinatal quality assessment in Croatia. BioMed Res Int 2015;2015:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/537318.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Dahl, LB, Berge, LN, Dramsdahl, H, Vermeer, A, Huurnink, A, Kaaresen, PI, et al.. Antenatal, neonatal and post neonatal deaths evaluated by medical audit. A population-based study in northern Norway – 1976 to 1997. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:1075–82. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016340009169267.Search in Google Scholar

28. De Reu, P, Van Diem, M, Eskes, M, Oosterbaan, H, Smits, LUC, Merkus, H, et al.. The Dutch Perinatal Audit Project: a feasibility study for nationwide perinatal audit in The Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2009;88:1201–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016340903280990.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Moxon, SG, Ruysen, H, Kerber, KJ, Amouzou, A, Fournier, S, Grove, J, et al.. Count every newborn; a measurement improvement roadmap for coverage data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:S8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-15-s2-s8.Search in Google Scholar

30. Pattinson, RC, Say, L, Makin, JD, Bastos, MH. Critical incident audit and feedback to improve perinatal and maternal mortality and morbidity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd002961.pub2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Eskes, M, Waelput, AJ, Erwich, JJ, Brouwers, HA, Ravelli, AC, Achterberg, PW, et al.. Term perinatal mortality audit in The Netherlands 2010–2012: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005652. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005652.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Misra, DP, Grason, H, Liao, M, Strobino, DM, McDonnell, KA, Allston, AA. The nationwide evaluation of fetal and infant mortality review (FIMR) programs: development and implementation of recommendations and conduct of essential maternal and child health services by FIMR programs. Matern Child Health J 2004;8:217–29. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:maci.0000047420.41215.f0.10.1023/B:MACI.0000047420.41215.f0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Lee, EJ, Gambatese, M, Begier, E, Soto, A, Das, T, Madsen, A. Understanding perinatal death: a systematic analysis of New York City fetal and neonatal death vital record data and implications for improvement, 2007–2011. Matern Child Health J 2014;18:1945–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1440-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Helps, A, Leitao, S, Greene, R, O’Donoghue, K. Perinatal mortality audits and reviews: past, present and the way forward. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;250:24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.04.054.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. The World Bank. High Income. The World Bank Group; 2021. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/XD.Search in Google Scholar

36. Mariani, G, Kasznia-Brown, J, Paez, D, Mikhail, MN, Salama, DH, Bhatla, N, et al.. Improving women’s health in low-income and middle-income countries. Part I: challenges and priorities. Nucl Med Commun 2017;38:1019. https://doi.org/10.1097/mnm.0000000000000751.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Case Control Study Checklist; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

38. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

39. Robertson, L, Knight, H, Prosser Snelling, E, Petch, E, Knight, M, Cameron, A, et al.. Each baby counts: national quality improvement programme to reduce intrapartum-related deaths and brain injuries in term babies. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;22:193–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2017.02.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Kieltyka, L, Craig, M, Goodman, D, Wise, R. Louisiana implementation of the national fetal and infant mortality review (NFIMR) program model: successes and opportunities. Matern Child Health J 2012;16:353–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1186-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Flenady, V, Mahomed, K, Ellwood, D, Charles, A, Teale, G, Chadha, Y, et al.. Uptake of the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand perinatal mortality audit guideline. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2010;50:138–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828x.2009.01125.x.Search in Google Scholar

42. Bullivant, J, Corbett-Nolan, A. Clinical audit: a simple guide for NHS Boards & partners: Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP); 2010.Search in Google Scholar

43. World Health Organization. Making every baby count: audit and review of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

44. NICE. Principles for best practice in clinical audit. Oxon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Publishing; 2002.Search in Google Scholar

45. O’Farrell, I, Manning, E, Corcoran, P, Greene, R. Perinatal mortality in Ireland annual report 2017. Cork: National Perinatal Epidemiology Centre; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

46. Manktelow, BN, Smith, LK, Seaton, SE, Hyman-Taylor, P, Kurinczuk, JJ, Field, DJ, et al., On behalf of the MBRRACE-UK Collaboration. The MBRRACE-UK perinatal surveillance report. Leicester: The Infant Mortality and Morbidity Studies; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

47. PMMRC. PMMRC twelfth annual report 2018 Jun. Wellington, New Zealand: Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

48. Chepkin, S, Prince, S, Johnston, T, Boby, T, Neves, M, Smith, P, et al.. Learning from standardised reviews when babies die. National perinatal mortality review tool: first annual report. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

49. World Health Organization. Improving the quality of paediatric care: an operational guide for facility-based audit and review of paediatric mortality. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

50. Flenady, V, Middleton, P, Smith, GC, Duke, W, Erwich, JJ, Khong, TY, et al.. Stillbirths 5. Stillbirths: the way forward in high-income countries. Lancet 2011;377:1703–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60064-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Lehner, C, Harry, A, Pelecanos, A, Wilson, L, Pink, K, Sekar, R. The feasibility of a clinical audit tool to investigate stillbirth in Australia – a single centre experience. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2019;59:59–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12799.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Allanson, ER, Tuncalp, O, Gardosi, J, Pattinson, RC, Francis, A, Vogel, JP, et al.. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during the perinatal period (ICD-PM): results from pilot database testing in South Africa and United Kingdom. BJOG 2016;123:2019–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14244.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Vergani, P, Cozzolino, S, Pozzi, E, Cuttin, MS, Greco, M, Ornaghi, S, et al.. Identifying the causes of stillbirth: a comparison of four classification systems. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:319.e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.098.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Reinebrant, HE, Leisher, SH, Coory, M, Henry, S, Wojcieszek, AM, Gardener, G, et al.. Making stillbirths visible: a systematic review of globally reported causes of stillbirth. BJOG 2018;125:212–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14971.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

55. Flenady, V, Frøen, JF, Pinar, H, Torabi, R, Saastad, E, Guyon, G, et al.. An evaluation of classification systems for stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-24.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Murray-Davis, B, McDonald, H, Cross-Sudworth, F, Dore, S, Marrin, M, DeSantis, J, et al.. Implementation of an interprofessional team review of adverse events in obstetrics using a standardized computer tool: a mixed methods study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2016;38:168–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2015.12.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Karran, S, Ranaboldo, C, Karran, A. Review of the perceptions of general surgical staff within the Wessex region of the status of quality assurance and surgical audit. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1993;75:104–7.Search in Google Scholar

58. Davison, K, Smith, L. Time spent by doctors on medical audit. Psychiatr Bull 1993;17:418–9. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.17.7.418.Search in Google Scholar

59. Johnston, G, Crombie, I, Alder, E, Davies, H, Millard, A. Reviewing audit: barriers and facilitating factors for effective clinical audit. BMJ Qual Saf 2000;9:23–36. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.9.1.23.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central