Abstract

Objectives

Placental examination in a case of stillbirth can provide insight into causative/associated factors with fetal demise. The aim of this study was to compare placental and umbilical cord pathologies in singleton stillbirth and livebirth placentas, and to find prevalence of various associated maternal and fetal clinical factors.

Methods

This case-control study was conducted at a tertiary-care center in India over a period of 20 months. About 250 women who delivered stillborn fetus ≥28 weeks’ gestation and 250 maternal-age-matched controls were recruited. Sociodemographic and clinical details were noted and placental gross and microscopic examination was done. Placental findings were compared between stillbirth and livebirth (overall), preterm stillbirth and preterm livebirth as well as term stillbirth and term livebirth in six categories – placenta gross, cord gross, membranes gross, maternal vascular malperfusion, fetal vascular malperfusion and inflammatory response. Prevalence of 11 maternal and fetal factors were studied in all categories of placental findings in both livebirth and stillbirth.

Results

Placental findings in all six categories were significantly associated with stillbirths (p<0.05). The placental findings associated with stillbirth with highest odds included placental hypoplasia (OR 9.77, 95% CI 5.46–17.46), necrotizing chorioamnionitis (OR 9.30, 95% CI 1.17–73.96) and avascular villi (OR 8.45, 95% CI 3.53–20.25). More than half of the women with stillbirths had medical disorders (n=130, 52.0%) and the most prevalent was hypertensive disorder (n=45, 18.0%).

Conclusions

Changes in placenta are associated with development of stillbirth. Therefore, antenatal investigations to identify placental dysfunction should be investigated to determine whether these reduce stillbirth. Also, placental examination in a case of stillbirth can detect/diagnose many maternal/fetal conditions and thereby can help in preventing future stillbirths.

Introduction

The placenta plays a critical role in fetal development and in in utero health of fetus. Its detailed examination in any adverse perinatal event is of paramount importance and is justified by the facts that it lies at the maternal and fetal interface; serves as an essential organ to provide nutrition and blood supply to fetus; is affected by varieties of pathogenic or vascular insult affecting mother or fetus and any placental pathology can jeopardize fate of fetus in utero or of infant in later life. A systematic review of studies of placental pathology and stillbirth reported that placental pathologies can be responsible for fetal death in up to 65% of cases [1].

In previous studies, gross and microscopic pathologies of placenta and umbilical cord have been linked to stillbirths [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Smaller/larger placenta, long/short cord, thick/thin cord, circumvallate or circummarginate insertion of membranes, fetal vascular malperfusions (FVM), maternal vascular malperfusions (MVM) as well as various fetal and maternal inflammatory responses in placental disc have been linked to stillbirths. These findings have also been linked to individual clinical entity/disease in mothers (diabetes, hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, thrombophilia, premature rupture of membranes) or in fetus (fetal anomalies and fetal growth restriction) separately or in combination. However, majority of these studies provide insight into single/few placental findings, lack study of clinical factors (in each category of placental abnormality group) in same cohort of patients, have used non-standardized protocol for placental examination or lack control group to compare findings. Moreover, only few studies have compared findings in term and preterm stillbirth/livebirth placentas [2, 12, 18]. Furthermore, placentas from apparently healthy infants also have reports of abnormal histopathological lesions (particularly chorioamnionitis) [19]. Hence, we conceptualized this case-control study about placental findings in singleton stillbirths with the following objectives: (1) to compare placental and umbilical cord pathologies in singleton stillbirth placentas and singleton livebirth placentas; (2) gestation-specific analysis of pathologies in preterm stillbirth placentas vs. preterm livebirth placentas; and in term stillbirth placentas vs. term livebirth placentas; (3) prevalence of various maternal and fetal clinical factors in mothers with findings in their placentas. We believe that since there is dearth of literature on this topic from the country which shares the maximum burden of stillbirth in the world [20], therefore this study will help in identifying high risk mothers for stillbirths in current or subsequent pregnancies and will foster data in the field of stillbirth.

Materials and methods

Design

This case-control study was conducted at a tertiary care and referral institute in central India over a duration of 20 months after approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Cases were women aged 18–40 years and delivered singleton stillborn baby at ≥28 weeks’ gestation and controls (maternal age-matched) were women who had liveborn babies at ≥28 weeks’ gestation [21]. Participants were recruited from antenatal and labor wards. All the consecutive stillbirths and every 30th liveborn placenta (after reviewing the institute’s previous year record for stillborn: live–born ratio) were recruited. The mothers who had premature induced termination of pregnancy because of lethal congenital anomalies and where the complete placenta was not available for examination (morbidly adherent placenta) were excluded from the study. In total, 267 stillbirths occurred over 20 months, among them 13 placentas were either too macerated to examine or were incomplete and four patients did not give consent, hence were excluded from study. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study. Cases and controls were also followed up till six months postdelivery. We noted the maternal and fetal clinical details along with placental gross and microscopic findings in each of the two groups – stillbirth and livebirths, and compared the prevalence of each placental finding in the two groups. We further divided each group into preterm (<37 weeks’) and term (≥37 weeks’) because of the variable prevalence of some placental findings according to the gestation and compared the prevalence of different placental findings between preterm stillbirths and preterm livebirths, and between term stillbirths and term live births.

Clinical details

Demographic characteristics of women (age, education, body mass index [BMI]), their clinical details (history of previous stillbirth, medical disorder in current pregnancy such as diabetes/hypertensive disorders of pregnancy [HDP]/thrombophilia/heart disease/autoimmune disorders, history of decreased fetal movement); obstetric details (parity, booked/unbooked pregnancy, any labor complication such as prolonged labor, meconium stained liquor, premature rupture of membrane, abruption, fetal distress); spontaneous/induced labor, gestational age at delivery and fetal details (fetal growth restriction, congenital anomaly/aneuploidy, birth weight) were noted in predesigned proforma.

The BMI range 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 was considered normal range [22]. The woman was considered booked when she had a minimum of four antenatal visits at our center. Among medical disorders, “diabetes” term included gestational diabetes, type one or type two diabetes mellitus; “hypertensive disorders” term included chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia; “thrombophilia” included all types of hereditary/acquired thrombophilia but excluded autoimmune disorders which were included in autoimmune disorders in separate category; and, thyroid disorders included both hypothyroid and hyperthyroid conditions. Other disorders studied were liver disorders, renal disorders and active infections (latent and past infections were excluded). In some women, the diagnosis of particular disorder/disease was made in postnatal period. If a woman had two or more than two disorders, we included these entities separately. A standard algorithm was used for the estimation of gestational age at death for stillborns and gestational age at birth for liveborns [23]. Small for gestational age fetus was defined when stillborn/infant had birthweight <10th centile as per reference population [24]. Fetal anomalies were confirmed after birth by detailed external examination of baby and/or infantogram/autopsy (where parental consent was available).

Placental and cord examination

After delivery of the placenta, it was examined along with cord for its completeness, for any retroplacental hematoma, meconium staining or maceration. After that, it was washed thoroughly and examined for any gross anomaly (succenturiate lobe); cord was examined for coiling, cord length, velamentous insertion, presence of three umbilical vessels and true knot; and membranes were examined for circumvallate or circummarginate insertion. Placenta was weighed and its dimensions were measured after trimming cord and extraplacental membrane before fixating it in formalin solution. The entire placenta, cord and membranes were sent in a formalin container to the pathology lab where sampling of placenta and histologic examination of placenta was done according to standard protocol by a general pathologist [25]. As per this standard protocol, we analyzed the placental findings under six categories – three categories of gross findings (gross findings of placenta, of umbilical cord and of membranes) and three categories of microscopic findings (maternal vascular malperfusions, fetal vascular malperfusions and maternal/fetal inflammatory responses).

The placenta was classified as hypoplastic when its weight was below 10th centile for standard gestational age [26]. Coiling index was calculated by dividing the total number of coils by total length of umbilical cord in centimeters. We considered 0.20 ± 0.10 coil/cm as normal coil index [27]. We also studied the prevalence of 11 clinical fetal and maternal factors (two fetal, nine maternal) associated with the six categories of placental findings: fetal – small for gestational age, gross congenital anomaly; maternal – diabetes, hypertensive disorders, thrombophilia, heart disease, autoimmune disease, prolonged labor, premature rupture of membranes, fetal distress and abruption.

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation were used for analyzing continuous variables. Categorical variables were analyzed with percentages and frequencies. Continuous data were analyzed using t-test, whereas Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test were used, when appropriate, for the analysis of categorical data. Difference was considered significant, if p-value was <0.05. Statistical analysis was done on Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas 77845 USA). Considering 5% confidence interval and 80% power of a reference study, the sample size estimated was 178 cases and 178 controls, respectively [3].

Results

Maternal and fetal factors

The mean age of patients was similar in stillbirth and livebirth groups (29.5 and 30.0 years, respectively). The majority of women with stillbirth belonged to middle class of socioeconomic status (n=165, 66.0%), were literate (n=178, 71.2%), had normal BMI (n=152, 60.8%), were booked (n=133, 53.2%), were primipara (n=162, 64.8%) and had spontaneous onset of labor (n=162, 64.8%) (Table 1). More than half of the women with stillbirths had medical disorders (n=130, 52.0%) and the most prevalent were hypertensive disorders (n=45, 18.0%). The proportion of patients with labor complications was higher in the stillbirth group (30.4%) than livebirths (15.2%). Other complications in the two groups included scar dehiscence (7 vs. 3), ruptured uterus (1 vs. 0), cord prolapse (4 vs. 3), shoulder dystocia (3 vs. 2) and placenta previa (10 vs. 12). Total 135 stillborns were preterm while only 11 liveborn were preterm babies. The total number of antepartum stillbirths was 165 (66%) and intrapartum stillbirths was 85 (34%). Among the congenital anomalies in the stillbirth group, the most prevalent were neural tube defects (n=25) followed by non-immune hydrops (n=16), cardiac defects (n=11), anencephaly 4(n=), trisomy 21 (n=3), multicystic dysplastic kidney (n=1) and bilateral renal agenesis (n=1). In control group also, neural tube defects were the most prevalent congenital anomalies (n=5).

Comparison of maternal and fetal factors in stillbirths and livebirths.

| S. No. | Factors | Stillbirths (n= 250) (%) | Livebirths (n=250) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mean age, years | 29.5 ± 1.0 | 30.0 ± 0.9 |

| 2. | Socioeconomic status | ||

| Upper | 29 (11.6) | 31(12.4) | |

| Middle | 165 (66.0) | 143 (57.2) | |

| Lower | 56 (22.4) | 76 (30.4) | |

| 3. | Education | ||

| Illiterate | 72 (28.8) | 56 (22.4) | |

| Literate | 178 (71.2) | 194 (77.6) | |

| 4. | Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| Underweight | 40 (16.0) | 34 (13.6) | |

| Normal | 152 (60.8) | 175 (70.0) | |

| Overweight | 58 (23.2) | 41 (16.4) | |

| 5. | History of previous stillbirth | ||

| Yes | 34 (13.6) | 12 (4.8) | |

| No | 216 (86.4) | 238 (95.2) | |

| 6. | Booking status | ||

| Unbooked | 117 (46.8) | 19 (7.6) | |

| Booked | 133 (53.2) | 231(92.4) | |

| 7. | History of medical disorder in current pregnancy | 130 (52.0) | 60 (24.0) |

| Diabetes | 38 (15.2) | 9 (3.6) | |

| Hypertension | 45 (18.0) | 17 (6.8) | |

| Thrombophilia | 8 (3.2) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Autoimmune | 11(4.4) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Heart Disease | 24 (9.6) | 8 (3.2) | |

| Other | 20 (8.0) | 35 (14.0) | |

| 8. | History of decreased fetal movement | ||

| Yes | 68 (27.2) | 5 (2.0) | |

| No | 182 (72.8) | 245 (98.0) | |

| 9. | Parity | ||

| Primipara | 162 (64.8) | 79 (31.6) | |

| Multipara | 88 (35.2) | 171 (68.4) | |

| 10. | Labor onset | ||

| Spontaneous | 162 (64.8) | 196 (78.4) | |

| Induced | 88 (35.2) | 54 (21.6) | |

| 11. | Complications in labor | 76 (30.4) | 38 (15.2) |

| Prolonged Labor | 31 (12.4) | 10 (4.0) | |

| Meconium stained liquor | 15 (6.0) | 8 (3.2) | |

| PROM | 17 (6.8) | 7 (2.8) | |

| Abruption | 16 (6.4) | 9 (3.6) | |

| Fetal distress | 24 (9.6) | 15 (6.0) | |

| Other | 25 (10.0) | 20 (8.0) | |

| 12. | Gestational age at delivery | ||

| <34 weeks | 75 (30.0) | 4 (1.6) | |

| 34-37 weeks | 60 (24.0) | 7 (2.8) | |

| >37 weeks | 115 (46.0) | 239 (95.6) | |

| 13. | Gross congenital anomaly | ||

| Yes | 62 (24.8) | 11 (4.4) | |

| No | 188 (75.2) | 239 (95.6) | |

| 14. | Small for gestational age fetus | ||

| Yes | 60 (24.0) | 25 (10.0) | |

| No | 190 (76.0) | 225 (90.0) | |

Placental findings

Placental findings overall and on gestation-specific analysis

The placental findings associated with stillborn placentas with highest odds included placental hypoplasia (OR 9.77, 95% CI 5.46–17.46), necrotizing chorioamnionitis (OR 9.30, 95% CI 1.17–73.96) and avascular villi (OR 8.45, 95% CI 3.53–20.25). All the six broad categories of placental findings, i.e., placental gross (OR 7.83, 95% CI 4.86–12.60), cord gross (OR 4.84, 95% CI 3.11–7.55), membrane gross (OR 1.74, 95% CI 1.01–2.99), maternal vascular malformations (OR 4.14, 95% CI 2.82–6.09), fetal vascular malformations (OR 7.75, 95% CI 4.72–12.74) and inflammatory findings (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.58–3.47), were more common (p value <0.05) in stillborn placentas than liveborn placentas (Table 2).

Comparison of placental findings between stillbirths and livebirth.

| Pathologic findings | SBa (n=250) (%) | LBb (n=250) (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gross findings – placental disc | 119 (47.6) | 26 (10.4) | 7.83 (4.86–12.60) | <0.001 |

| i) Placental hypoplasia | 96 (38.4) | 15 (6.0) | 9.77 (5.46–17.46) | <0.001 |

| ii) Retroplacental Hemorrhage | 13 (5.2) | 7 (2.8) | 1.90 (0.75–4.86) | 0.178 |

| iii) Succenturiate Lobe | 10 (4.0) | 4 (1.6) | 2.57 (0.79–8.28) | 0.116 |

| 2. Gross findings – umbilical cord | 106 (42.4) | 33 (13.2) | 4.84 (3.11–7.55) | <0.001 |

| i) Hypocoiled | 18 (7.2) | 7 (2.8) | 2.69 (1.11–6.57) | 0.029 |

| ii) Hypercoiled | 22 (8.8) | 9 (3.6) | 2.58 (1.17–5.73) | 0.020 |

| iii) Long/short cord | 47 (18.8) | 12(4.8) | 4.59 (2.37–8.89) | <0.001 |

| iv) Velamentous cord insertion | 5 (2.0) | 1 (0.4) | 5.08 (0.59–43.81) | 0.139 |

| v) Two vessel cord | 8 (3.2) | 3 (1.2) | 2.72 (0.71–10.38) | 0.143 |

| vi) True knot | 4 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 4.05 (0.45–36.49) | 0.213 |

| 3. Gross findings – membranes | 39 (15.6) | 24 (9.6) | 1.74 (1.01–2.99) | 0.045 |

| i) Meconium staining | 32 (12.8) | 18 (7.2) | 1.80 (1.03–3.47) | 0.039 |

| ii) Circumvallate insertion | 4 (1.6) | 5 (2.0) | 0.80 (0.211–3.00) | 0.737 |

| iii) Circummarginate insertion | 3 (1.2) | 1(0.4) | 3.02 (0.31–29.27) | 0.340 |

| 4. Maternal vascular malperfusions | 139 (55.6) | 58 (23.2) | 4.14 (2.82–6.09) | <0.001 |

| i) Distal villous hypoplasia | 19 (7.6) | 8 (3.2) | 2.49 (1.07–5.80) | 0.035 |

| ii) Accelerated villous maturation | 5 (2.0) | 1 (0.4) | 5.08 (0.59–43.81) | 0.139 |

| iii) Infarct | 21 (8.4) | 6 (2.4) | 3.73 (1.48–9.40) | 0.005 |

| iv) Retroplacental hemorrhage | 26 (10.4) | 7 (2.8) | 4.30 (1.71–9.47) | 0.001 |

| v) Decidual arteriopathy | ||||

| (1) Arterial thrombosis | 15 (6.0) | 2 (0.8) | 7.91 (1.79–34.99) | 0.006 |

| (2) Fibrinoid necrosis of vessels | 38 (15.2) | 11 (4.4) | 3.89 (1.94–7.81) | <0.001 |

| (3) Absence of spiral artery remodeling | 15 (6.0) | 23 (9.2) | 0.63 (0.32–1.24) | 0.180 |

| 5. Fetal vascular malperfusions | 110 (44.0) | 23 (9.2) | 7.75 (4.72–12.74) | <0.001 |

| i) Avascular villi | 43 (17.2) | 6 (2.4) | 8.45 (3.53–20.25) | <0.001 |

| ii) Thrombosis (arterial/venous) | 37 (14.8) | 12 (4.8) | 3.45 (1.75–6.78) | <0.001 |

| iii) Intramural fibrin deposition | 45 (18.0) | 25 (10.0) | 1.98 (1.17–3.34) | 0.011 |

| 6. Inflammatory response | 98 (37.2) | 54 (21.6) | 2.34 (1.58–3.47) | <0.001 |

| i) Maternal | ||||

| (1) Acute chorionitis | 12 (4.8) | 5 (2.0) | 2.47 (0.86–7.12) | 0.094 |

| (2) Acute chorioamnionitis | 57 (22.8) | 27 (10.8) | 2.44 (1.48–4.01) | <0.001 |

| (3) Necrotizing chorioamnionitis | 9 (3.6) | 1 (0.4) | 9.30 (1.17–73.96) | 0.036 |

| ii) Fetal | ||||

| (1) Chorionic vasculitis/cord phlebitis | 12 (4.8) | 19 (7.6) | 0.61 (0.29–1.29) | 0.198 |

| (2) Umbilical arteritis | 8 (3.2) | 2 (0.8) | 4.10 (0.86–19.50) | 0.076 |

-

aStillbirth; blivebirth.

On gestation-specific analysis, gross placental/cord findings which were more prevalent in preterm stillbirth placentas included retroplacental hemorrhage, succenturiate lobe, abnormal coiling index, abnormal length of cord and meconium staining of membranes. In histology, retroplacental hemorrhage, absence of spiral artery remodeling, thrombosis of vessels, intramural fibrin deposition, acute chorioamnionitis and chorionic vasculitis/cord phlebitis were more prevalent in preterm stillbirth placentas than preterm livebirth placentas. Placental gross findings more common in term stillbirth than term livebirth included placental hypoplasia, retroplacental hemorrhage, abnormal coiling index, abnormal length of cord and meconium staining; among the histological findings, infarction of placental parenchyma, retroplacental hemorrhage, fibrinoid necrosis of vessels, avascular villi, thrombosis of vessels, intramural fibrin deposition and acute chorioamnionitis were more prevalent in term stillbirths (Table 3).

Gestation-specific analysis of placental findings.

| Pathologic findings | PT SBa (n=135) (%) |

PT LBb (n=11) (%) |

p1-Value | T SB (n=115) (%) |

T LBd (n=239) (%) |

p2-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Gross findings – placental disc | ||||||

| i) Placental hypoplasia | 43 (31.9) | 4 (36.4) | 0.758 | 53 (46.1) | 14 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| ii) Retroplacental hemorrhage | 7 (5.2) | 4 (36.4) | 0.002 | 6 (5.2) | 3 (1.3) | 0.041 |

| iii) Succenturiate lobe | 4 (3.0) | 3 (27.3) | 0.003 | 6 (5.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0.180 |

| 2) Gross findings – umbilical cord | ||||||

| i) Hypocoiled | 10 (7.4) | 3 (27.3) | 0.040 | 8 (7.0) | 4 (1.7) | 0.018 |

| ii) Hypercoiled | 12 (8.9) | 4 (36.4) | 0.01 | 10 (8.7) | 5 (2.09) | 0.008 |

| iii) Long/short cord | 13 (9.6) | 8 (72.7) | <0.001 | 34 (29.6) | 4 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| iv) Velamentous cord insertion | 4 (3.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0.309 | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.264 |

| v) Two vessel cord | 5 (3.7) | 2 (18.2) | 0.050 | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.4) | 0.110 |

| vi) True knot | 1 (0.7) | 1 (9.1) | 0.074 | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.075 |

| 3) Gross findings – membranes | ||||||

| i) Meconium staining | 13 (9.6) | 6 (54.5) | <0.001 | 19 (16.5) | 12 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| ii) Circumvallate insertion | 1 (0.7) | 1 (9.1) | 0.074 | 3 (2.6) | 4 (1.7) | 0.056 |

| iii) Circummarginate insertion | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.594 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 0.604 |

| 4) Maternal vascular malperfusions | ||||||

| i) Distal villous hypoplasia | 17 (12.6) | 1 (9.1) | 0.735 | 11 (9.6) | 10 (4.2) | 0.064 |

| ii) Accelerated villous maturation | 23 (17.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0.503 | 9 (7.8) | 11 (4.6) | 0.263 |

| iii) Infarct | 6 (4.4) | 1 (9.1) | 0.498 | 15 (13.0) | 5 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| iv) Retroplacental hemorrhage | 13 (9.6) | 5 (45.5) | 0.002 | 13 (11.3) | 2 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| v) Decidual arteriopathy | ||||||

| (1) Arterial thrombosis | 7 (5.2) | 1 (9.1) | 0.589 | 8 (7.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.007 |

| (2) Fibrinoid necrosis of vessels | 17 (12.6) | 4 (36.4) | 0.042 | 21 (18.3) | 7 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| (3) Absence of spiral artery remodeling | 12 (8.9) | 8 (72.7) | <0.001 | 3 (2.6) | 15 (6.3) | 0.135 |

| 5) Fetal vascular malperfusions | ||||||

| i) Avascular villi | 20 (1.5) | 4 (36.4) | 0.077 | 23 (20.0) | 2 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| ii) Thrombosis (arterial/venous) | 14 (10.4) | 4 (36.4) | 0.020 | 21 (18.3) | 8 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| iii) Intramural fibrin deposition | 15 (11.1) | 6 (54.5) | <0.001 | 30 (26.1) | 19 (8.0) | <0.001 |

| 6) Inflammatory response | ||||||

| i) Maternal | ||||||

| (1) Acute chorionitis | 8 (5.9) | 2 (18.2) | 0.144 | 4 (3.5) | 3 (1.3) | 0.177 |

| (2) Acute chorioamnionitis | 37 (27.4) | 7 (63.6) | 0.019 | 20 (17.4) | 12 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| (3) Necrotizing chorioamnionitis | 6 (4.4) | 1 (9.1) | 0.498 | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.075 |

| ii) Fetal | ||||||

| (1) Chorionic vasculitis/cord phlebitis | 7 (5.2) | 9 (81.8) | <0.001 | 5 (4.4) | 10 (4.2) | 0.943 |

| (2) Umbilical arteritis | 4 (3.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0.309 | 4 (3.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0.056 |

-

aPreterm stillbirth; bpreterm livebirth; cterm stillbirth; dterm livebirth.

Various placental findings and maternal/fetal clinical factors

Placental gross findings

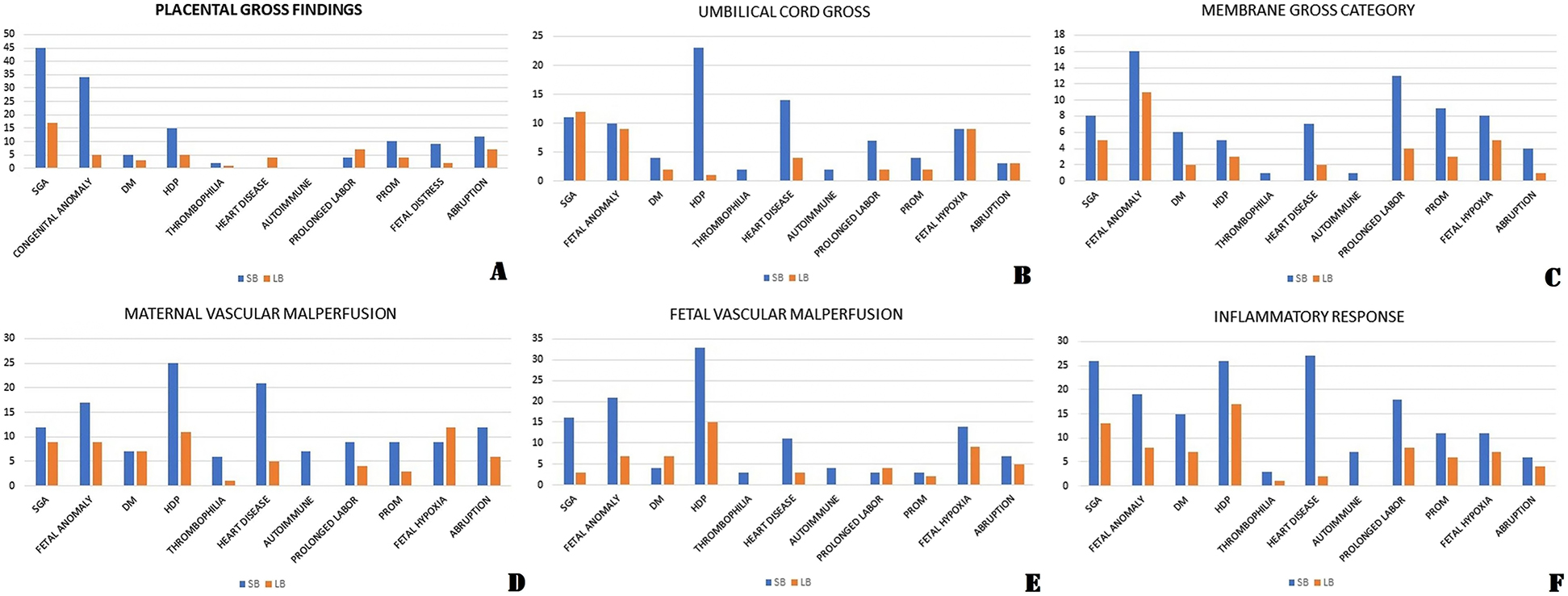

The absolute number of women in both the groups (cases and controls) with concerned clinical factor was compared in each category of placental finding (Figure 1A–F). The most prevalent maternal factor among cases in gross placental category was hypertensive disorders (n=15) followed by abruption (n=12) and growth restricted fetus were more in number (n=45) than anomalous fetus (n=34) (Figure 1A). Out of total 96 stillbirth hypoplastic placentas, 40 were associated with SGA fetus while out of 15 livebirth hypoplastic placentas, 10 had SGA baby.

Prevalence of various maternal and clinical factors in different category of placental findings in stillbirth group and livebirth group.

(A) Placental gross category. (B) Umbilical cord gross category. (C) Membranes gross category. (D) Maternal vascular malperfusion category. (E) Fetal vascular malperfusion category. (F) Maternal/fetal inflammatory response category.

Umbilical cord gross findings

Total 11 fetuses were SGA in stillbirth group: five had abnormal coiling index, three had both abnormal coiling index and short/long cord and one had long cord while hypertensive disorder were the most prevalent maternal factor in this category (23 women: 12 had abnormal coiling index, eight had short/long cord, two had two vessel cord and one had true knot) (Figure 1B).

Membrane gross findings

Meconium staining of placenta was significant finding in stillbirth group (overall, preterm, term) in this category. In stillbirth group, total 16 fetus had congenital anomalies: 10 had meconium staining, three had circumvallate insertion and three had circummarginate insertion of cord. The majority of women (13) had prolonged labor (10 had meconium staining) in this category (Figure 1C).

Maternal vascular malperfusions

Distal villous hypoplasia (OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.07–5.80), infarction of placental tissue (OR 3.73, 95% CI 1.48–9.40), retroplacental hemorrhage (OR 4.03, 95% CI 1.71–9.47), arterial thrombosis (OR 7.91, 95% CI 1.79–34.99), fibrinoid necrosis of vessel (OR 3.89, 95% CI 1.94–7.81) were significant findings in stillbirth group. The number of anomalous fetus (n=17: nine had distal villous hypoplasia) was higher than SGA fetus (n=12) in stillbirth group and hypertensive disorder was the most prevalent maternal factor (25: 15 had absence of remodeling) followed by heart disease (21: seven had arterial thrombosis and five had fibrinoid necrosis) (Figure 1D).

Fetal vascular malperfusions

Avascular villi (OR 8.45, 95% CI 3.53–20.25), thrombosis of vessels (OR 3.45, 95% CI 1.75–6.78), intramural fibrin deposition (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.17–3.34) were significant placental findings in stillbirth group. In this group, total 21 fetus had congenital anomalies and 15 fetus had arterial thrombosis in placenta out of these 21 fetus. The majority of the mothers who had FVM in their placentas had hypertensive disorder in both stillbirth group and livebirth group (33 and 15) (Figure 1E).

Inflammatory response

Among all kind of inflammatory responses, acute chorioamnionitis (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.48–4.01) and necrotizing chorioamnionitis (OR 9.30, 95% CI 1.17–73.96) were significant placental inflammatory responses in stillbirth group. The majority of women had hypertensive disorder in both stillbirth and livebirth groups (26 vs. 17) (Figure 1F). We had one interesting case where an unbooked patient came at study center at 32 weeks period of gestation in labor with intra-uterine fetal death. She delivered stillborn fetus and her placenta was sent for examination. Gross examination was normal but placental histopathology revealed caseous granulomas with Langhans giant cells. The patient was asymptomatic at the time of presentation. On follow-up, she was diagnosed as a case of miliary tuberculosis and was started on anti-tubercular drugs as per protocol.

Discussion

The placenta plays a very crucial role in the development of fetus. Hence, placental evaluation holds paramount importance, particularly in adverse perinatal outcomes. We evaluated and compared placental and umbilical cord pathologies in singleton stillbirth placentas with singleton livebirth placentas, and did a gestation-specific analysis of placental pathologies in stillbirths and livebirths. We found that placental findings in all the six categories were more common in stillbirths than livebirths. Also, the placental findings associated with stillborn placentas with highest odds included placental hypoplasia, necrotizing chorioamnionitis and avascular villi.

While comparing placental weight, we found that smaller placentas had significant association with stillbirths especially with term stillbirths. Similar to our finding Hutcheon et al. found association between lower placental weight and risk of stillbirth [4]. Furthermore, SGA and hypertensive disorders were the most prevalent finding in this category, implying that hypertensive disorders may affect placental development and its weight which in turn can affect fetal growth [5]. Various reasons have been hypothesized for this association. McDonald et al. hypothesized that low level of pro-angiogenic factor leads to smaller placenta, which in turn is responsible for inadequate nutrient support to fetus and adverse perinatal outcome [6]. The role of high level of anti-angiogenic proteins and low proangiogenic proteins have been also seen in SGA fetus and pre-eclampsia in literature [28]. Placentas with succenturiate lobe were significantly associated with stillbirth after 37 weeks of gestation in our study as has been previously reported also [7]. Machin et al. and Tantbirojn et al. concluded that abnormal coiling index is associated with risk of stillbirth [8, 9]. We also found that umbilical cord coiling abnormalities significantly were more prevalent in the both the preterm and term stillbirth group. We also found that the higher numbers of babies were SGA in cord gross category. Sharma et al. conducted a cross-sectional study in 408 antenatal women and found that abnormal coiling index calculated at antenatal scan at 18–20 weeks of gestation was associated with preterm birth and low birth weight [29]. The clinical implication of above findings is that placental and cord (coiling index) assessment during antenatal scans is very important and can detect mothers at high risk of SGA babies, hypertensive disorders and fetal demise.

Meconium staining of placenta may indicate in utero fetal hypoxia. Fetal anomalies and prolonged labor both have been established as a risk factor for fetal hypoxia and hence may lead to passage of meconium that in turn may lead to fetal death [10]. Therefore, anytime during pregnancy or labor, presence of meconium in liquor or prolonged labor should alarm the obstetrician and such mothers should be kept under intense monitoring to save fetus. We could not find any significance of circumvallate and circummarginate insertion with studied outcome. However, contrary to our findings, Suzuki S found that incidence of intrauterine fetal death and other complications (premature delivery, oligohydramnios, etc.) was significantly higher in patients with circumvallate placentas than that in controls [11].

The normal and adequate blood flow to maternal vessels is essential to provide oxygen and nutrients to fetus and therefore, any maternal vascular pathology can affect growth of fetus and further outcome of pregnancy. Uterine vasculature aberrations from the normal remodeling process are central to the pathologic process in development of MVM. This leads to either abnormal high velocity and turbulent flow through un-remodeled spiral arterioles or reduced blood flow secondary to reduced vascular capacity. Among the livebirths, MVMs were the most frequent microscopic pathologies observed in our study (23%). Similarly, Pathak et al. found that chronic placental underperfusion was found in a substantial number of normal singleton pregnancies (7%) [19]. Man et al. found that MVMs were the most frequent placental abnormalities associated with stillbirth [18]. Similarly, MVMs were found in 56% of stillbirths in our study. Pre-eclampsia has strong association with MVM histopathological findings. Autoimmune disorders such as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus have also been found associated with MVM [30]. Similar to above findings; in our study, 55.55% of total hypertensive mothers and 63.63 % of total mothers with autoimmune disorders in stillbirth group had MVM in their placenta. The recurrent rate of such lesions can be upto 25% in next pregnancy [5]. Similar to our findings, MVM have been associated with fetal death in previous studies also [12], [13], [14, 30]. In literature, the association between fetal anomalies (especially congenital heart defect) and risk of pre-eclampsia in mothers have been described and placental vascular malperfusions have been found as a common finding in both type of placentas implying the role of common etiologic factors in fetal anomalies and hypertensive disorders that in turn may lead to stillbirth [31]. If MVM are diagnosed in a case of stillborn placentas, further complete maternal check-up to look for hidden/latent hypertensive disorders or autoimmune disorders are warranted and more intensive monitoring in next pregnancy is of paramount importance. Various maternal conditions (thrombophilic disorders [protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, factor V leiden mutation], preeclampsia and anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome) and various fetal conditions (fetal growth restriction, fetal anomalies, fetal infection and fetal death) have been associated with changes of FVM [15]. We also found that FVM were significantly more common in stillbirth placentas and 37.5% women with thrombophilia had FVM changes in placenta. More number of stillbirths had congenital anomalies in this category implying that screening for hypertensive disorders and thrombophilia is needed for such mothers who had placenta with FVM. However, we agree that it is difficult to differentiate that whether these FVM changes are before or after demise of fetus in utero and this can be a major limitation in interpretating data in this specific category.

Placenta is formed by three major units: placental disc, chorioamniotic membranes and umbilical cord. Acute inflammatory lesions can involve either one or two or all of these three units. Acute chorioamnionitis is defined as histologic evidence of neutrophilic infiltration in these membranes but this response may be due to infective or to non-infective etiology. In our study, all cases of fetal inflammatory responses were associated with acute chorioamnionitis. Inflammatory disorders especially chorioamnionitis have been associated with stillbirths [15, 32]. Lahra et al. concluded that absence of fetal inflammatory response is associated with antepartum unexplained stillbirths [16]. We also found that more livebirth placentas had fetal inflammatory response than stillbirth placentas; however, this difference was not significantly associated in our study. Recent literature suggests that non-infective inflammation of chorioamniotic membranes can also be caused by endogenous mediators known as “damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)” or alarmins which should be explored more in future [17]. Similar to our finding, Williams et al. studied total 2,579 infants and concluded that histologic chorioamnionitis was associated with markers of fetal growth restriction in both preterm and term infants [33].

The strength of our study was that it was conducted in a tertiary-care referral institute with patients coming from various parts of the country and therefore has a heterogenous patient population. Secondly, studying the placental lesions associated with stillbirths has more significance, when it is done in those parts of the world which contribute the largest proportion of the caseload, as was done in this study. Also, we included livebirths as controls further increasing the strength of the study. This study is more informative as patients’ clinical findings were also studied with their placental findings. However, this study had some limitations that should be considered while interpreting the results. First, the pathologists were not blinded to the outcome – stillbirth or livebirth. Secondly, on gestation-specific analysis, the sample size in the subgroups was relatively small. Therefore, more such kind of studies at larger scale are needed in evaluating the role and association of placental findings in stillbirths. However, as very few of this kind of studies are available from the developing world, our results will foster future research in this direction and will provide baseline data to the Obstetricians and the policy-makers alike. Also, there may be significant overlap between macroscopic findings and microscopic findings of placenta in our study, however, our categorization of the placental findings in the two broad groups (macroscopic and microscopic) was not mutually exclusive. The six categories of placental lesions were chosen to comprehensively characterize the placental findings including both macroscopic and microscopic findings. Moreover, some selection bias might be present in the study as majority of participants who had a stillbirth were of middle-class and were literate, contrary to the findings in literature. However, those contradictory findings might also reflect the population in the study area.

Our study identified that both gross (gross lesions of placenta, umbilical cord and membranes) and placental microscopic lesions (maternal vascular malperfusions, fetal vascular malperfusions and inflammatory response) were associated with stillbirths. Hypertensive disorders, fetal anomalies and growth restriction were the most prevalent clinical factors in stillbirth fetus with placental pathology. Many of such placental lesions (weight, succenturiate lobe, coiling index) can be diagnosed antenatally and these pregnancies should be monitored carefully to prevent intrauterine fetal death. Many placental lesions when identified postnatally (MVM, FVM) warrant evaluation of mothers to rule out hypertensive disorders and/or autoimmune disorders. Furthermore, identifying placental pathology in stillbirth placenta may allay anxiety of mother/parents to some extent where no direct fetal/maternal cause can be identified. To conclude, placental examination in a case of stillbirth can detect/diagnose many maternal/fetal conditions and thereby can help in preventing future stillbirths in high-risk mothers.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr Nisha B Meshram for her expert opinion regarding interpretation of microscopic findings in placental tissues.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013), and has been approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board (Institutional Ethics Committee, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, India) or equivalent committee. (F.11/IEC/MAMC/10/No. 199, dated 20th November 2013).

References

1. Ptacek, I, Sebire, NJ, Man, JA, Brownbill, P, Heazell, AE. Systematic review of placental pathology reported in association with stillbirth. Placenta 2014;35:552–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2014.05.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Amir, H, Weintraub, A, Aricha-Tamir, B, Apel-Sarid, L, Holcberg, G, Sheiner, E. A piece in the puzzle of intrauterine fetal death: pathological findings in placentas from term and preterm intrauterine fetal death pregnancies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2009;22:759–64. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767050902929396.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Helgadóttir, LB, Turowski, G, Skjeldestad, FE, Jacobsen, AF, Sandset, PM, Roald, B, et al.. Classification of stillbirths and risk factors by cause of death – a case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:325–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12044.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Hutcheon, JA, McNamara, H, Platt, RW, Benjamin, A, Kramer, MS. Placental weight for gestational age and adverse perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:1251–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e318253d3df.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Awuah, SP, Okai, I, Ntim, EA, Bedu-Addo, K. Prevalence, placenta development, and perinatal outcomes of women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. PLoS One 2020;15:e0233817. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233817.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. McDonald, CR, Darling, AM, Liu, E, Tran, V, Cabrera, A, Aboud, S, et al.. Angiogenic proteins, placental weight and perinatal outcomes among pregnant women in Tanzania. PLoS One 2016;11:e0167716. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167716.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Ma, JS, Mei, X, Niu, YX, Li, QG, Jiang, XF. Risk factors and adverse pregnancy outcomes of Succenturiate placenta: a case-control study. J Reprod Med 2016;61:139–44.Search in Google Scholar

8. Machin, GA, Ackerman, J, Gilbert-Barness, E. Abnormal umbilical cord coiling is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2000;3:462–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100240010103.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Tantbirojn, P, Saleemuddin, A, Sirois, K, Crum, CP, Boyd, TK, Tworoger, S, et al.. Gross abnormalities of the umbilical cord: related placental histology and clinical significance. Placenta 2009;30:1083–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2009.09.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Jacques, SM, Qureshi, F. Does in utero meconium passage in term stillbirth correlate with autopsy and placental findings of hypoxia or inflammation? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1770217 [Epub ahead of print].Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Suzuki, S. Clinical significance of pregnancies with circumvallate placenta. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2008;34:51–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00682.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Pinar, H, Goldenberg, RL, Koch, MA, Heim-Hall, J, Hawkins, HK, Shehata, B, et al.. Placental findings in singleton stillbirths. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:325–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000000100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Andres, RL, Kuyper, W, Resnik, R, Piacquadio, KM, Benirschke, K. The association of maternal floor infarction of the placenta with adverse perinatal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:935–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(90)91100-q.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Nikkels, PG, Evers, AC, Schuit, E, Brouwers, HA, Bruinse, HW, Bont, L, et al.. Placenta pathology from term born neonates with normal or adverse outcome. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2021;24:121–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1093526620980608.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Lema, G, Mremi, A, Amsi, P, Pyuza, JJ, Alloyce, JP, Mchome, B, et al.. Placental pathology and maternal factors associated with stillbirth: an institutional based case-control study in Northern Tanzania. PLoS One 2020;15:e0243455. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243455.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Lahra, MM, Gordon, A, Jeffery, HE. Chorioamnionitis and fetal response in stillbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:229-e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.10.900.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Brien, ME, Baker, B, Duval, C, Gaudreault, V, Jones, RL, Girard, S. Alarmins at the maternal-fetal interface: involvement of inflammation in placental dysfunction and pregnancy complications. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2019;97:206–12. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2018-0363.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Man, J, Hutchinson, JC, Heazell, AE, Ashworth, M, Jeffrey, I, Sebire, NJ. Stillbirth and intrauterine fetal death: role of routine histopathological placental findings to determine cause of death. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;48:579–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.16019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Pathak, S, Sebire, NJ, Hook, L, Hackett, G, Murdoch, E, Jessop, F, et al.. Relationship between placental morphology and histological findings in an unselected population near term. Virchows Arch 2011;459:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-011-1061-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Lawn, JE, Blencowe, H, Pattinson, R, Cousens, S, Kumar, R, Ibiebele, I. Stillbirths: Where? When? Why? How to make data count? Lancet 2011;377:1448–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62187-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. World Health Organization. Department of maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health [Online]. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/epidemiology/stillbirth/en [Accessed 10 Mar 2021].Search in Google Scholar

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About adult BMI [Online]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html [Accessed 22 Mar 2021].Search in Google Scholar

23. Conway, DL, Hansen, NI, Dudley, DJ, Parker, CB, Reddy, UM, Silver, RM, et al.. An algorithm for the estimation of gestational age at the time of fetal death. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2013;27:145–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12037.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Hadlock, FP, Harrist, RB, Martinez-Poyer, J. In utero analysis of fetal growth: a sonographic weight standard. Radiology 1991;181:129–33. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.181.1.1887021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Khong, TY, Mooney, EE, Ariel, I, Balmus, NC, Boyd, TK, Brundler, MA, et al.. Sampling and definitions of placental lesions: Amsterdam placental workshop group consensus statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016;140:698–713. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2015-0225-cc.Search in Google Scholar

26. Almog, B, Shehata, F, Aljabri, S, Levin, I, Shalom-Paz, E, Shrim, A. Placenta weight percentile curves for singleton and twins deliveries. Placenta 2011;32:58–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2010.10.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Sharma, B, Bhardwaj, N, Gupta, S, Gupta, PK, Verma, A, Malviya, K. Association of umbilical coiling index by colour Doppler ultrasonography at 18-22 weeks of gestation and perinatal outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2012;62:650–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-012-0230-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Cerdeira, AS, Karumanchi, SA. Angiogenic factors in preeclampsia and related disorders. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012;2:a006585. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a006585.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Sharma, R, Radhakrishnan, G, Manchanda, S, Singh, S. Umbilical coiling index assessment during routine fetal anatomic survey: a screening tool for fetuses at risk. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2018;68:369–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-017-1046-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Dudley, DJ, Goldenberg, R, Conway, D, Silver, RM, Saade, GR, Varner, MW, et al.. A new system for determining the causes of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:254–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e3181e7d975.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Heider, A. Fetal vascular malperfusion. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017;141:1484–9. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2017-0212-ra.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Goldenberg, RL. Infection related stillbirths. Lancet 2014;375:1482–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61712-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Williams, MC, O’Brien, WF, Nelson, RN, Spellacy, WN. Histologic chorioamnionitis is associated with fetal growth restriction in term and preterm infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:1094–9. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2000.108866.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Preventing stillbirth: risk factors, case reviews, care pathways

- Managing stillbirth: taking care to investigate the cause and provide care for bereaved families

- Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- Spatial dynamics of fetal mortality and the relationship with social vulnerability

- Stillbirth occurrence during COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based prospective study

- The effect of the Covid pandemic and lockdown on stillbirth rates in a South Indian perinatal centre

- Stillbirths preceded by reduced fetal movements are more frequently associated with placental insufficiency: a retrospective cohort study

- The prevalence of and risk factors for stillbirths in women with severe preeclampsia in a high-burden setting at Mpilo Central Hospital, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

- Surveillance and Prevention

- Perinatal mortality audits and reporting of perinatal deaths: systematic review of outcomes and barriers

- Stillbirth diagnosis and classification: comparison of ReCoDe and ICD-PM systems

- Facility-based stillbirth surveillance review and response: an initiative towards reducing stillbirths in a tertiary care hospital of India

- Impact of introduction of the growth assessment protocol in a South Indian tertiary hospital on SGA detection, stillbirth rate and neonatal outcome

- Evaluating the Growth Assessment Protocol for stillbirth prevention: progress and challenges

- Prospective risk of stillbirth according to fetal size at term

- Understanding the Pathology of Stillbirth

- Placental findings in singleton stillbirths: a case-control study from a tertiary-care center in India

- Abnormal placental villous maturity and dysregulated glucose metabolism: implications for stillbirth prevention

- Comparison of prenatal central nervous system abnormalities with postmortem findings in fetuses following termination of pregnancy and clinical utility of postmortem examination

- Cardiac ion channels associated with unexplained stillbirth – an immunohistochemical study

- Viral infections in stillbirth: a contribution underestimated in Mexico?

- Audit and Bereavement Care

- Investigation and management of stillbirth: a descriptive review of major guidelines

- Delivery characteristics in pregnancies with stillbirth: a retrospective case-control study from a tertiary teaching hospital

- Perinatal bereavement care during COVID-19 in Australian maternity settings

- Beyond emotional support: predictors of satisfaction and perceived care quality following the death of a baby during pregnancy

- Stillbirth aftercare in a tertiary obstetric center – parents’ experiences

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Preventing stillbirth: risk factors, case reviews, care pathways

- Managing stillbirth: taking care to investigate the cause and provide care for bereaved families

- Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- Spatial dynamics of fetal mortality and the relationship with social vulnerability

- Stillbirth occurrence during COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based prospective study

- The effect of the Covid pandemic and lockdown on stillbirth rates in a South Indian perinatal centre

- Stillbirths preceded by reduced fetal movements are more frequently associated with placental insufficiency: a retrospective cohort study

- The prevalence of and risk factors for stillbirths in women with severe preeclampsia in a high-burden setting at Mpilo Central Hospital, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

- Surveillance and Prevention

- Perinatal mortality audits and reporting of perinatal deaths: systematic review of outcomes and barriers

- Stillbirth diagnosis and classification: comparison of ReCoDe and ICD-PM systems

- Facility-based stillbirth surveillance review and response: an initiative towards reducing stillbirths in a tertiary care hospital of India

- Impact of introduction of the growth assessment protocol in a South Indian tertiary hospital on SGA detection, stillbirth rate and neonatal outcome

- Evaluating the Growth Assessment Protocol for stillbirth prevention: progress and challenges

- Prospective risk of stillbirth according to fetal size at term

- Understanding the Pathology of Stillbirth

- Placental findings in singleton stillbirths: a case-control study from a tertiary-care center in India

- Abnormal placental villous maturity and dysregulated glucose metabolism: implications for stillbirth prevention

- Comparison of prenatal central nervous system abnormalities with postmortem findings in fetuses following termination of pregnancy and clinical utility of postmortem examination

- Cardiac ion channels associated with unexplained stillbirth – an immunohistochemical study

- Viral infections in stillbirth: a contribution underestimated in Mexico?

- Audit and Bereavement Care

- Investigation and management of stillbirth: a descriptive review of major guidelines

- Delivery characteristics in pregnancies with stillbirth: a retrospective case-control study from a tertiary teaching hospital

- Perinatal bereavement care during COVID-19 in Australian maternity settings

- Beyond emotional support: predictors of satisfaction and perceived care quality following the death of a baby during pregnancy

- Stillbirth aftercare in a tertiary obstetric center – parents’ experiences