Clinical chorioamnionitis at term X: microbiology, clinical signs, placental pathology, and neonatal bacteremia – implications for clinical care

-

Roberto Romero

, Percy Pacora

Abstract

Objectives

Clinical chorioamnionitis at term is considered the most common infection-related diagnosis in labor and delivery units worldwide. The syndrome affects 5–12% of all term pregnancies and is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality as well as neonatal death and sepsis. The objectives of this study were to determine the (1) amniotic fluid microbiology using cultivation and molecular microbiologic techniques; (2) diagnostic accuracy of the clinical criteria used to identify patients with intra-amniotic infection; (3) relationship between acute inflammatory lesions of the placenta (maternal and fetal inflammatory responses) and amniotic fluid microbiology and inflammatory markers; and (4) frequency of neonatal bacteremia.

Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study included 43 women with the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis at term. The presence of microorganisms in the amniotic cavity was determined through the analysis of amniotic fluid samples by cultivation for aerobes, anaerobes, and genital mycoplasmas. A broad-range polymerase chain reaction coupled with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry was also used to detect bacteria, select viruses, and fungi. Intra-amniotic inflammation was defined as an elevated amniotic fluid interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentration ≥2.6 ng/mL.

Results

(1) Intra-amniotic infection (defined as the combination of microorganisms detected in amniotic fluid and an elevated IL-6 concentration) was present in 63% (27/43) of cases; (2) the most common microorganisms found in the amniotic fluid samples were Ureaplasma species, followed by Gardnerella vaginalis; (3) sterile intra-amniotic inflammation (elevated IL-6 in amniotic fluid but without detectable microorganisms) was present in 5% (2/43) of cases; (4) 26% of patients with the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis had no evidence of intra-amniotic infection or intra-amniotic inflammation; (5) intra-amniotic infection was more common when the membranes were ruptured than when they were intact (78% [21/27] vs. 38% [6/16]; p=0.01); (6) the traditional criteria for the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis had poor diagnostic performance in identifying proven intra-amniotic infection (overall accuracy, 40–58%); (7) neonatal bacteremia was diagnosed in 4.9% (2/41) of cases; and (8) a fetal inflammatory response defined as the presence of severe acute funisitis was observed in 33% (9/27) of cases.

Conclusions

Clinical chorioamnionitis at term, a syndrome that can result from intra-amniotic infection, was diagnosed in approximately 63% of cases and sterile intra-amniotic inflammation in 5% of cases. However, a substantial number of patients had no evidence of intra-amniotic infection or intra-amniotic inflammation. Evidence of the fetal inflammatory response syndrome was frequently present, but microorganisms were detected in only 4.9% of cases based on cultures of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in neonatal blood.

Introduction

Clinical chorioamnionitis, the most common infection-related diagnosis in labor and delivery units [1], [2], [3], [4], affects 5–12% of term gestations worldwide [2], [5]. This syndrome is associated with severe maternal morbidity (e.g., an increased risk of cesarean delivery due to failure to progress in labor [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], uterine atony [2], [7], [13], septic thrombophlebitis [2], [14], endometritis [14], [15], [16], wound infection [2], [14], [17]), admission to the intensive care unit [18], neonatal morbidity (e.g., sepsis and meconium aspiration syndrome) [2], [5], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], and mortality [4] as well as long-term sequelae such as neurologic injury [23] and cerebral palsy [15], [24].

Clinical chorioamnionitis is thought to be caused by ascending microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity (MIAC) [25], which elicits a maternal inflammatory response characterized by clinical signs that may include fever, maternal tachycardia, uterine tenderness, malodorous discharge, and maternal leukocytosis [9], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]. Fetal tachycardia is often present and may reflect an increase in maternal temperature and/or a fetal inflammatory response [31], [32], [33], [34].

In 2015, we reported that clinical chorioamnionitis is not a single entity but rather a syndrome associated with (1) proven intra-amniotic infection [35], (2) sterile intra-amniotic inflammation [35], or (3) maternal signs of systemic inflammation without intra-amniotic inflammation [35]. The most common microorganisms detected in the amniotic fluid of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term were Ureaplasma species and Gardnerella vaginalis [35]. The microbiology of intra-amniotic infection remains important given that the antibiotics routinely administered to mothers or neonates are not effective against genital mycoplasmas (e.g., Ureaplasma spp. and Mycoplasma hominis).

The clinical criteria traditionally used to diagnose clinical chorioamnionitis and to identify patients with intra-amniotic infection are of limited value [36]. Further investigations revealed more features of the syndrome by describing the maternal [37], intra-amniotic [38], [39], [40], and fetal inflammatory responses [41] as well as the lipidomic characteristics of this condition [42].

Given the importance of the new findings reported, we became interested in determining whether these findings could be replicated in an independent study. Therefore, the objectives of the study herein were to determine (1) the microbiology of amniotic fluid by using cultivation and molecular microbiologic techniques; (2) the diagnostic accuracy of the clinical criteria used to identify patients with intra-amniotic infection; (3) a relationship between acute inflammatory lesions of the placenta (i.e., maternal and fetal inflammatory responses) and amniotic fluid microbiology and inflammatory markers; and (4) the frequency of neonatal bacteremia.

Materials and methods

Study population

This retrospective cohort study was conducted by searching the clinical database and bank of biological samples of Wayne State University, the Detroit Medical Center, and the Perinatology Research Branch. Patients diagnosed with clinical chorioamnionitis at term at Hutzel Women’s Hospital were included in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) singleton gestation, (2) delivery ≥37 weeks of gestation, (3) absence of known fetal chromosomal or structural anomalies, and (4) a transabdominal amniocentesis to assess the microbial state of the amniotic cavity.

A transabdominal amniocentesis was offered to patients with the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis at the discretion of the attending physician to identify the microbial status of the amniotic cavity. Women who agreed to undergo this procedure were asked to donate additional amniotic fluid and to allow collection of clinical information for research purposes. All patients provided written informed consent prior to the procedure and the collection of samples. The use of biological specimens as well as clinical and ultrasound data for research purposes was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Wayne State University.

Clinical definitions

Gestational age was determined by menstrual age and fetal biometry [43]. Clinical chorioamnionitis was diagnosed based on the presence of an elevation in maternal temperature (≥37.8 °C) associated with two or more of the following criteria: (1) maternal tachycardia (heart rate >100 beats/min); (2) fetal tachycardia (heart rate >160 beats/min); (3) uterine tenderness; (4) malodorous vaginal discharge; and (5) maternal leukocytosis (leukocyte count >15,000 cells/mm3) [7], [44]. The criteria for an elevation in maternal temperature were the same as those proposed by Gibbs et al. [9], [26] and subsequently employed by other investigators studying intra-amniotic infection [1], [45], [46], [47]. Neonatal bacteremia was diagnosed in the presence of a positive neonatal blood culture result within 72 h of delivery [48], [49].

MIAC was defined as the presence of microorganisms in the amniotic fluid detected by either an amniotic fluid culture or polymerase chain reaction with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (PCR/ESI-MS) (Ibis, Technology-Athogen, Carlsbad, CA). Intra-amniotic inflammation was defined as an amniotic fluid interleukin (IL)-6 concentration ≥2.6 ng/mL [50], [51]. Based on the results of amniotic fluid cultivation, PCR/ESI-MS testing [52], [53], [54], [55], and amniotic fluid concentrations of IL-6 [50], [51], patients were classified into four clinical subgroups: (1) no intra-amniotic infection/inflammation (negative amniotic fluid by both culture and PCR/ESI-MS and the absence of intra-amniotic inflammation); (2) sterile intra-amniotic inflammation (negative amniotic fluid using both culture and PCR/ESI-MS but the presence of intra-amniotic inflammation [56], [57], [58]); (3) MIAC without intra-amniotic inflammation (positive amniotic fluid by culture and/or PCR/ESI-MS but the absence of intra-amniotic inflammation); and (4) intra-amniotic infection (positive amniotic fluid by culture and/or PCR/ESI-MS and the presence of intra-amniotic inflammation).

Sample collection

Amniotic fluid was obtained by transabdominal amniocentesis under sterile conditions and transported to the clinical laboratory. Analyses of the amniotic fluid white blood cell (WBC) count [59], glucose concentration [60], and Gram stain [61] were performed shortly after collection. Amniotic fluid not required for clinical assessment was centrifuged at 1,300×g for 10 min at 4 °C, shortly after amniocentesis, and the supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Placental histopathologic examination

Placentas were collected in the Labor and Delivery Unit or Operating Room at Hutzel Women’s Hospital of the Detroit Medical Center and transferred to the Perinatology Research Branch laboratory. Sampling of the placentas was performed according to protocols of the Perinatology Research Branch, as previously described [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67]. A minimum of five full-thickness sections of the chorionic plate, three sections of the umbilical cord, and three chorioamniotic membrane rolls from each case were examined by placental pathologists who were blinded to the clinical histories and additional testing results. Acute inflammatory lesions of the placenta (maternal inflammatory response and fetal inflammatory response) were diagnosed according to established criteria, including staging and grading [65], [67], [68]. Severe acute placental inflammatory lesions were defined as stage 3 and/or grade 2 [65], [67].

Detection of microorganisms utilizing cultivation and molecular microbiologic methods

Amniotic fluid was analyzed by utilizing cultures for aerobes, anaerobes, and genital mycoplasmas as well as by broad-range real-time PCR/ESI-MS. Briefly, DNA was extracted from 300 μL of amniotic fluid by implementing a method that combined bead-beating cell lysis with magnetic bead-based extraction [69], [70]. The extracted DNA was amplified on Ibis’s broad bacteria and Candida spectrum assay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR/ESI-MS identified 3,400 bacteria and 40 Candida spp., represented in the platform’s signature database [71], [72]. For viral detection, the nucleic acids were extracted from 300 μL of amniotic fluid by using a method that combined chemical lysis with magnetic bead-based extraction. The extracted RNA/DNA was amplified on the broad viral assay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In the eight wells, there were 14 primer pairs used to detect the following viruses: Herpes simplex virus 1 (HHV-1), Herpes simplex virus 2 (HHV-2), Varicella-zoster virus (HHV-3), Epstein–Barr virus (HHV-4), Cytomegalovirus (HHV-5), Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus (HHV-8), human adenoviruses, human enteroviruses, BK polyomavirus, JC polyomavirus, and Parvovirus B19 [73], [74].

After PCR amplification, 30-μL aliquots of each PCR product were desalted and analyzed by ESI-MS as previously described [71]. The presence of microorganisms was determined by signal processing and triangulation analysis of all base composition signatures obtained from each sample and then compared to a database. Along with organism identification, the ESI-MS analysis includes a Q-score and level of detection (LOD). The Q-score, a rating between 0 (low) and 1 (high), represents a relative measure of the strength of the data that support identification; only Q-scores ≥0.90 were reported for the broad bacteria and Candida spectrum assay [75]. The LOD describes the amount of amplified DNA present in the sample: this was calculated with reference to an internal calibrant, as previously described [76] and reported herein as genome equivalents per PCR reaction well (GE/well). The sensitivity (LOD) of PCR/ESI-MS for the detection of bacteria in the blood is, on average, 100 CFU/mL (95% confidence interval [CI], 6,600 CFU/mL) [72]. A comparison of detection limits between blood and amniotic fluid indicated that the assays have comparable detection limits (100 CFU/mL) [73]. The sensitivity (LOD) for the broad viral load in plasma ranges from 400 copies/mL to 6,600 copies/mL [77].

Determination of IL-6 in amniotic fluid

IL-6 concentrations were determined to assess the magnitude of the intra-amniotic inflammatory response. We used a sensitive and specific enzyme immunoassay obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique and concentrations were determined by interpolation from the standard curves. The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation for IL-6 were 8.7 and 4.6%, respectively. The detection limit of the IL-6 assay was 0.09 pg/mL. The amniotic fluid IL-6 concentrations were determined for research purposes, and such results were not used in patient management. We have reported extensively on the use of IL-6 in the assessment of intra-amniotic inflammation [50], [54], [73], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93].

Statistical analysis

A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and visual plot inspection were used to assess the normality of continuous data distributions. Non-parametric tests were used for comparison between (Mann–Whitney U test) and among (Kruskal–Wallis) groups to examine the differences in arithmetic variable distributions. A χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used to test for differences in proportions, as appropriate. The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was used to adjust for multiple comparisons wherever required. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, accuracy, and positive and negative likelihood ratios were calculated to identify intra-amniotic infection. Analysis was performed by SPSS v.21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

This study included 43 cases of clinical chorioamnionitis at term. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are displayed in Table 1. The median gestational age was 39.7 weeks. The median maternal temperature at the time of diagnosis was 38.5 °C (interquartile range [IQR], 38.1–38.9 °C). Eighty-six percent (37/43) of patients had intact membranes, and 47% (20/43) were admitted with spontaneous labor. Sixty-three percent (27/43) of patients delivered vaginally.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristics | Results |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 24 (20–26) |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 77% (33/43) |

| Caucasian | 11.5% (5/43) |

| Other | 11.5% (5/43) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 35.0 (27.8–41.5) |

| Smoking status | 17% (7/42) |

| Nulliparity | 70% (30/43) |

| Maternal temperature at the time of diagnosis, °C | 38.5 (38.1–38.9) |

| Uterine tenderness | 27% (6/22) |

| Malodorous vaginal discharge | 0% (0/25) |

| Fetal tachycardia (>160 beats/min) | 81% (35/43) |

| Maternal tachycardia (>100 beat/min) | 86% (37/43) |

| Maternal blood WBC count (cells/mm3) | 15,700 (13,700–18,400) |

| Maternal leukocytosis (>15,000 cells/mm3) | 30% (8/27) |

| Intact membranes at admission | 86% (37/43) |

| Spontaneous onset of labor at admission | 47% (20/43) |

| Gestational age at amniocentesis, weeks | 39.7 (38.2–40.3) |

| Rupture of the membranes at the time of amniocentesis | 63% (27/43) |

| Epidural analgesia | 84% (36/43) |

| Amniocentesis before epidural analgesia | 28% (10/36) |

| Amniocentesis after epidural analgesia | 72% (26/36) |

| Amniotic fluid analysis | |

| Amniotic fluid white blood cell count, cells/mm3 | 24.5 (2.2–874.5) |

| Amniotic fluid glucose concentration, mg/dL | 1.0 (1.0–9.5) |

| Amniotic fluid Gram stain positive | 23% (10/43) |

| Amniotic fluid interleukin-6, ng/mL | 5.1 (1.3–21.8) |

| Cesarean delivery | 37% (16/43) |

-

Data presented as median (interquartile range) and percentage (n/N).

-

WBC, white blood cell.

Eighty-four percent (36/43) of patients received epidural analgesia during labor. A transabdominal amniocentesis was performed prior to the administration of an epidural analgesia in 23% (10/43) of patients. Among the 41 patients who received antibiotic treatment before delivery, 78% (32/41) received these agents prior to the amniocentesis; of this group, 72% (23/32) received antibiotics less than 6 h before amniocentesis. The most frequent antibiotics administered were ampicillin and gentamicin (93% [38/41]), which is in keeping with the standard clinical recommendations of professional organizations [94].

Microorganisms detected in the samples of amniotic fluid

Fifty-three percent (23/43) of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term had microorganisms identified by cultivation of the amniotic fluid, whereas 67% (28/42) of patients were positive for microorganisms using PCR/ESI-MS. The combination of cultivation techniques and PCR/ESI-MS detected microorganisms in 70% (30/43) of amniotic fluid samples. Table 2 shows the microorganisms identified in the amniotic fluid culture and/or PCR/ESI-MS with the number of genome equivalents per PCR well (GE/well) for each case, amniotic fluid IL-6 concentration, and presence of acute placental inflammatory lesions.

Microorganisms determined by amniotic fluid cultures and/or PCR/ESI-MS with genome equivalents per PCR well (GE/well), amniotic fluid inflammatory profiles, and acute placental inflammatory lesions.

| Patient number | Group | Amniotic fluid test results | Acute placental inflammatory lesions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microorganisms detected by cultivation | Microorganisms detected by PCR/ESI-MS | Microbial burden (GE/well) | Amniotic fluid IL6 (ng/mL) | Histologic chorioamnionitis | Acute funisitis | ||||

| Present | Severe lesions | Present | Severe lesions | ||||||

| 1 | Intra-amniotic infection (n=27) | Ureaplasma urealyticum | Lactobacillus spp. | 286 | 16.1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, Streptococcus agalactiae | Ureaplasma parvum | 682 | 40.39 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Lactobacillus spp. | 181 | ||||||||

| 3 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus anginosus | Gardnerella vaginalis | 170 | 23.24 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Group G streptococcus | 135 | ||||||||

| Sneathia spp. | 31 | ||||||||

| Streptococcus spp. | 40 | ||||||||

| 4 | Ureaplasma urealyticum | Ureaplasma parvum | 550 | 13.84 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 63 | ||||||||

| 5 | Streptococcus agalactiae | Streptococcus agalactiae | 140 | 39.88 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 6 | Gardnerella vaginalis, Enterococcus faecalis, Actinomyces israelii | Gardnerella vaginalis | 111 | 6.71 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| 7 | Ureaplasma urealyticum | Ureaplasma urealyticum | 212 | 3.77 | No | No | No | No | |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 14 | ||||||||

| 8 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, Peptostreptococcus spp., Gardnerella vaginalis, Streptococcus viridans, Porphyromonas spp. | Sneathia spp. | 118 | 36.69 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| 9 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Streptococcus anginosus | Ureaplasma parvum | 90 | 40.25 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 151 | ||||||||

| 10 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, S. aureus | Ureaplasma parvum | 142 | 37.49 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 11 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Streptococcus agalactiae | Streptococcus agalactiae | 133 | 11.16 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 12 | Gardnerella vaginalis, Peptostreptococcus spp., Lactobacillus spp., Streptococcus anginosus, Prevotella bivia | Gardnerella vaginalis | 53 | 5.99 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| 13 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, Fusobacterium spp. | Fusobacterium nucleatum | 124 | 66.27 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 14 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus viridans, Peptostreptococcus spp. | Ureaplasma parvum | 73 | 15.70 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 31 | ||||||||

| Fusobacterium varium | 71 | ||||||||

| 15 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Escherichia coli | Ureaplasma urealyticum | 164 | 9.94 | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Candida albicans | 6 | ||||||||

| Lactobacillus spp. | 238 | ||||||||

| Roseolovirus (HHV-7) | 33 | ||||||||

| 16 | Mycoplasma hominis, Gardnerella vaginalis, Bacteroides spp., Peptostreptococcus spp., Streptococcus anginosus, Bifidobacterium spp., Prevotella bivia | Sneathia spp. | 89 | 24.95 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 17 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Candida albicans | Ureaplasma parvum | 298 | 4.02 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| 18 | Ureaplasma urealyticum | Ureaplasma parvum | 762 | 4.47 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 176 | ||||||||

| Candida albicans | 14 | ||||||||

| 19 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis | Ureaplasma parvum | 576 | 3.31 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| 20 | Ureaplasma urealyticum | Not available | - | 5.51 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| 21 | Candida albicans | Negative | 0 | 107.63 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| 22 | Negative | Ureaplasma parvum | 263 | 61.58 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Streptococcus oralis | 122 | ||||||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 122 | ||||||||

| 23 | Negative | Ureaplasma urealyticum | 978 | 33.30 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 24 | Negative | Candida albicans | 173 | 20.36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 25 | Negative | Propionibacterium acnes | 30 | 4.80 | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 26 | Negative | Propionibacterium acnes | 13 | 4.49 | No | No | No | No | |

| 27 | Negative | Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) | 8 | 5.07 | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 28 | Microorganisms in amniotic fluid without intra-amniotic inflammation (n=3) | Lactobacillus spp. | Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens | 10 | 0.44 | No | No | No | No |

| 29 | Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis | Gardnerella vaginalis | 40 | 1.29 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Mycoplasma hominis | 23 | ||||||||

| Sneathia spp. | 5 | ||||||||

| 30 | Negative | Streptococcus mitis | 6 | 1.39 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 6 | ||||||||

| 31 | Sterile intra-amniotic inflammation (n=2) | Negative | Negative | 0 | 2.66 | Yes | No | No | No |

| 32 | 0 | 7.28 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |||

| 33 | No intra-amniotic infection or inflammation (n=11) | Negative | Negative | 0 | 0.11 | No | No | No | No |

| 34 | 0 | 0.37 | No | No | No | No | |||

| 35 | 0 | 0.12 | No | No | No | No | |||

| 36 | 0 | 0.05 | No | No | No | No | |||

| 37 | 0 | 0.84 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| 38 | 0 | 0.39 | No | No | No | No | |||

| 39 | 0 | 0.38 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| 40 | 0 | 0.35 | Yes | No | No | No | |||

| 41 | 0 | 1.20 | No | No | No | No | |||

| 42 | 0 | 2.56 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| 43 | 0 | 1.82 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

-

PCR/ESI-MS, polymerase chain reaction with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry.

Among 23 patients with a positive amniotic fluid culture, the most frequent microorganism was Ureaplasma urealyticum [74% (17/23)], followed by M. hominis [26% (6/23)], G. vaginalis [17% (4/23)], Streptococcus agalactiae (17% [4/23]), and Streptococcus anginosus [17% (4/23)]. Candida albicans was identified in two patients (9% [2/23]). Interestingly, 65% (15/23) of these patients had an amniotic fluid culture positive for two or more microorganisms.

The most frequent microorganisms identified among patients were Ureaplasma parvum (32% [9/28]), followed by G. vaginalis (25% [7/28]), U. urealyticum (11% [3/28]), and C. albicans (11% [3/28]). Two or more microorganisms were identified in 43% (12/28) of these patients.

Among the 30 patients whose amniotic fluid tested positive by culture and/or PCR/ESI-MS, overall, 25 microbial taxa (22 bacterial species, one fungus, and two viruses) were present. Of them, nine microbial taxa were detected by both culture and PCR/ESI-MS (Ureaplasma spp., G. vaginalis, M. hominis, Lactobacillus spp., Candida spp., S. agalactiae, S. anginosus, Fusobacterium spp., and Staphylococcus aureus); nine were detected by amniotic fluid culture only (Peptostreptococcus spp., Enterococcus faecalis, Prevotella spp., Streptococcus viridans Bacteroides spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Escherichia coli, Porphyromonas spp., and Actinomyces israelii); seven were detected by only PCR/ESI-MS (Sneathia spp., Propionibacterium acnes, Streptococcus pneumonia, Streptococcus oralis, Group G streptococcus, herpes simplex virus [HSV]-1, and Roseolovirus [HHV-7]). In one patient, the only microorganism found was herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 (Table 2; patient 27). One patient had Roseolovirus (HHV-7), but there were multiple bacteria identified in the amniotic fluid (Table 2, patient 15).

Intra-amniotic inflammatory response in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis

Intra-amniotic inflammation [50] was identified in 67% (29/43) of the study participants. When combining the results of amniotic fluid cultures, PCR/ESI-MS, and amniotic fluid IL-6 concentrations, 63% (27/43) had intra-amniotic infection, 5% (2/43) had sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, 7% (3/43) had microorganisms without intra-amniotic inflammation, and 25% (11/43) of patients did not have intra-amniotic inflammation or microorganisms.

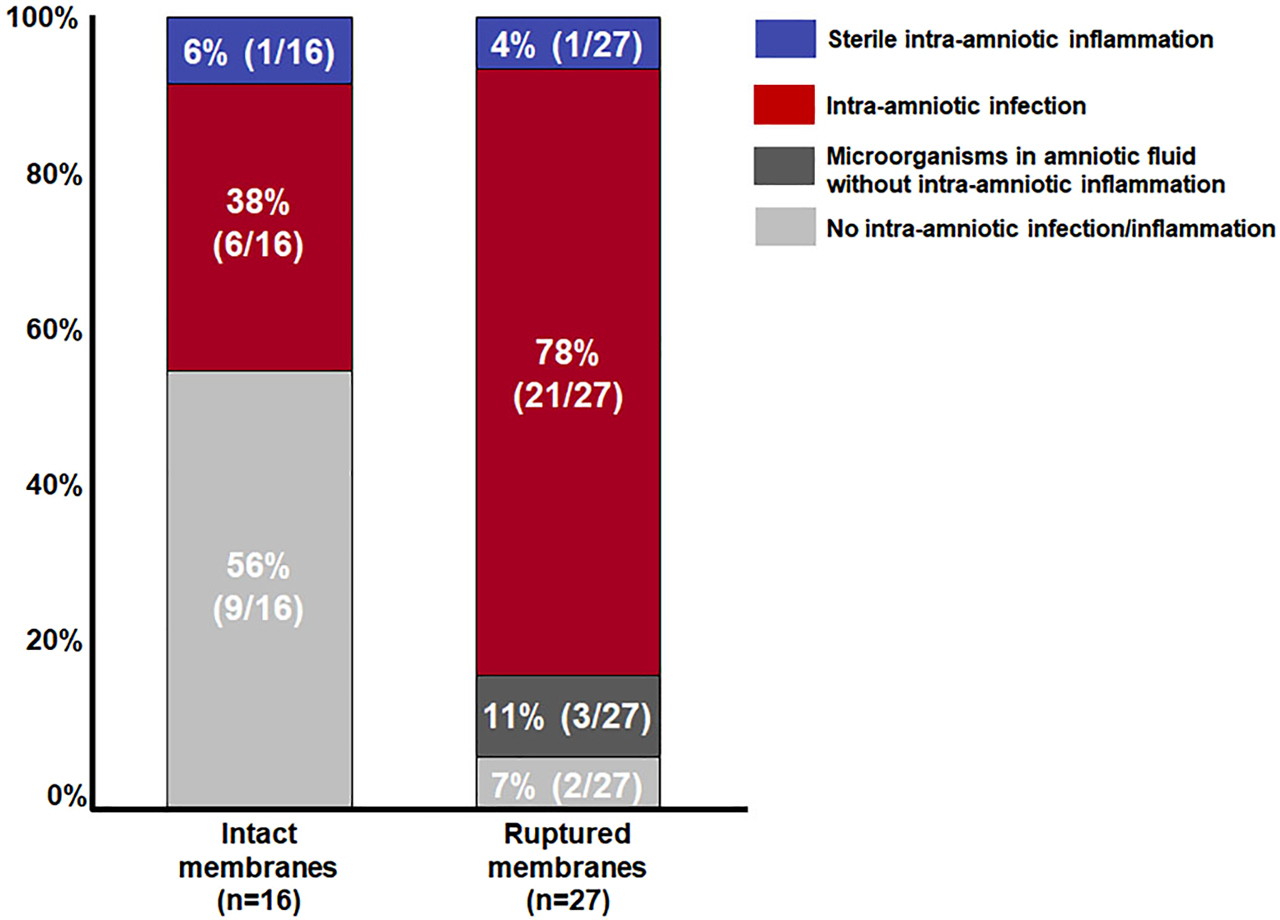

In the presence of ruptured membranes, the frequency of intra-amniotic infection was two-fold higher than when the membranes were intact (ruptured membranes, 78% [21/27] vs. intact membranes, 38% [6/16], p=0.01) (Figure 1). The frequency of patients with neither intra-amniotic infection nor intra-amniotic inflammation was eight-fold higher in patients with intact membranes than in those with ruptured membranes (intact membranes, 56% [9/16] vs. ruptured membranes, 7% [2/27], p<0.001). There was no difference in the frequency of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation and the proportion of patients with microorganisms in the amniotic fluid but without intra-amniotic inflammation between cases whose membranes were already ruptured at the time of amniocentesis and those with intact membranes (sterile intra-amniotic inflammation: ruptured membranes, 4% [1/27] vs. intact membranes, 6% [1/16], p=1.0; microorganisms without intra-amniotic inflammation: ruptured membranes, 11% [3/27] vs. intact membranes, 0% [0/16], p=0.28).

Prevalence of intra-amniotic infection and sterile intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term according to the status of the membranes at the time of amniocentesis (intact vs. ruptured).

Table 3 describes the results of biomarkers of inflammation in amniotic fluid and maternal blood among the four subgroups of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term. The distribution of the amniotic fluid WBC count and concentrations of amniotic fluid IL-6 and amniotic fluid glucose varied significantly among the four groups (Kruskal–Wallis, p<0.001, p<0.0001, p<0.05, respectively). However, there was no significant difference in the median maternal blood WBC counts among the four clinical groups (p=0.41).

Inflammatory markers in the maternal blood and amniotic fluid of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term according to the results of amniotic fluid cultures, PCR/ESI-MS, and IL-6 concentrations.

| Parameters | Clinical chorioamnionitis at term | p-Valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No intra-amniotic infection or inflammation (n=11) | Microorganisms in amniotic fluid without intra-amniotic inflammation (n=3) | Sterile intra-amniotic inflammation (n=2) | Intra-amniotic infection (n=27) | ||

| Maternal blood WBC count, cells/mm3 | 15,300 (12,400–17,500) | 13,100 (12,900–17,300) | 21,800 (19,650–23,950) | 15,700 (13,700–18,400) | 0.41 |

| Amniotic fluid WBC count, cells/mm3 | 2.5 (0–4.5) | 2.0 (1–7.5) | 16 (9–23) | 600 (44.5–1,819) | <0.001b |

| Amniotic fluid IL-6, ng/mL | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 1.3 (0.9–1.3) | 5.0 (3.8–6.1) | 15.7 (5.3–37.1) | <0.0001b,c |

| Amniotic fluid glucose, mg/dL | 6 (2–15) | 9 (7.5–10.5) | 7 (5–9) | 1 (1–4) | <0.05 |

-

Data are presented as median (interquartile range). WBC, white blood cell; IL, interleukin; PCR/ESI-MS, polymerase chain reaction with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. aKruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA test followed by post hoc analysis using Dunn test. bp<0.001 for comparison between patients with no intra-amniotic infection/inflammation and those with intra-amniotic infection. cp<0.05 for comparison between patients with microorganisms in amniotic fluid without intra-amniotic inflammation and those with intra-amniotic infection.

The median amniotic fluid WBC counts were significantly higher in patients with intra-amniotic infection than in those without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation (median [IQR], 600 cells/mm3 [44.5–1,819] vs. 2.5 cells/mm3 [0–4.5], p<0.001).

The median amniotic fluid IL-6 concentrations were significantly higher in patients with intra-amniotic infection than in those without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation (median [IQR], 15.7 ng/mL [5.3–37.1] vs. 0.4 ng/mL [0.2–1.0], p<0.0001). Also, patients with intra-amniotic infection had a significantly higher median amniotic fluid IL-6 concentration than those with microorganisms without intra-amniotic inflammation (median [IQR], 15.7 ng/mL [5.3–37.1] vs. 1.3 ng/mL [0.9–1.3], p<0.05). There was no significant difference in the median amniotic fluid WBC count, IL-6 concentration, and glucose concentration between patients with intra-amniotic infection and those with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation. Among patients with a positive PCR/ESI-MS, the median amniotic fluid IL-6 concentrations were not significantly different between patients with polymicrobial infection (n=11) and those with single microbial infection (n=17) (median [IQR], polymicrobial infection; 13.8 [4.1–31.7] ng/mL vs. single microbial infection: 11.2 [4.8–33.3] ng/mL; p=0.96).

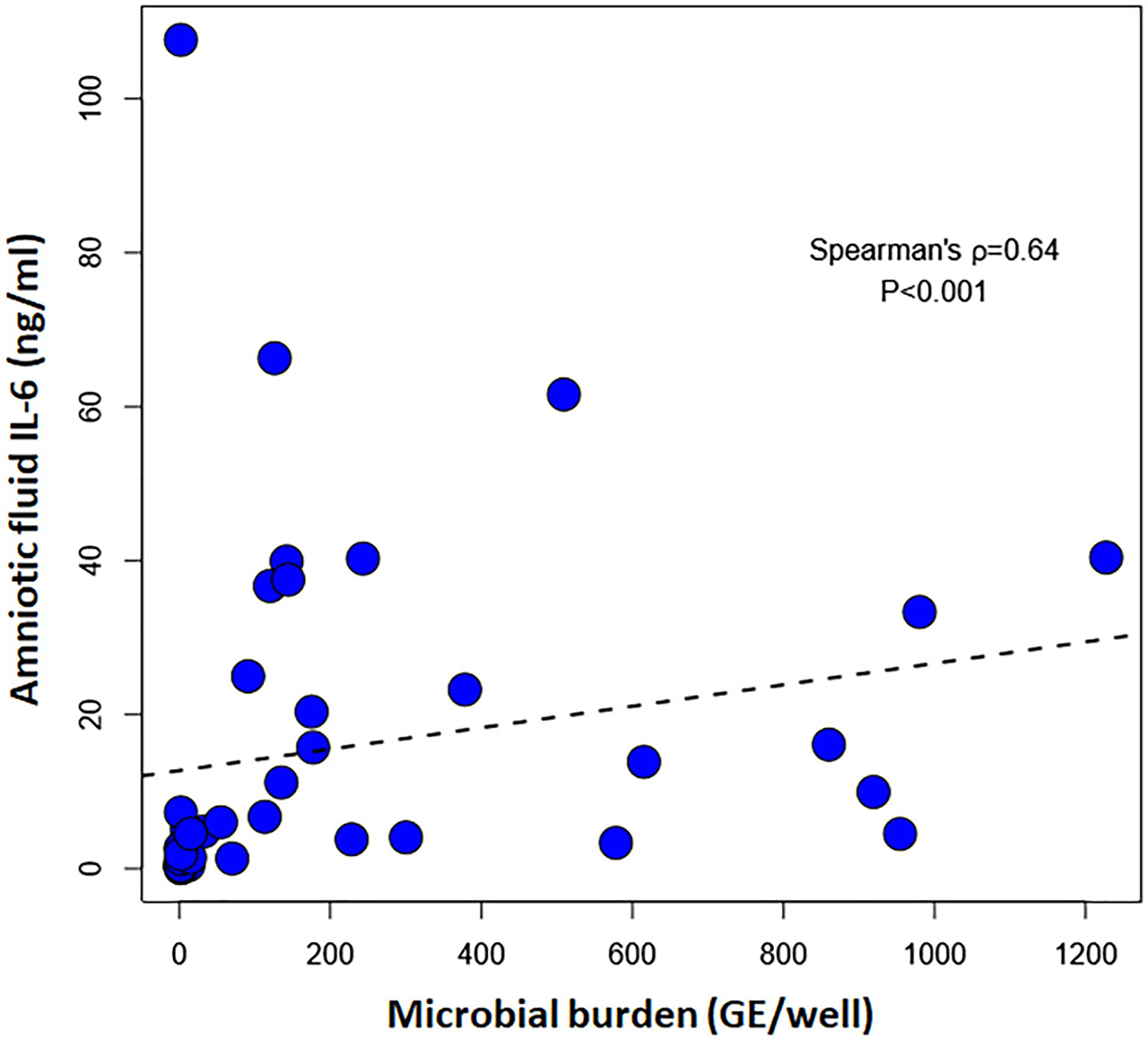

The microbial burden, expressed as GE/well, was significantly correlated with the amniotic fluid concentration of IL-6 (Spearman’s r=0.64; p<0.001) (Figure 2). There was also a correlation between the amniotic fluid WBC concentration and microbial burden (Spearman’s r=0.69; p<0.001).

Correlation between amniotic fluid interleukin-6 concentration and the microbial burden (GE /well) in patients with a positive PCR/ESI-MS, Spearman’s ρ=0.64; p>0.001. PCR/ESI-MS: polymerase chain reaction with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry.

Accuracy of clinical criteria for a diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis

Fever was considered a requirement for the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis [26]. The most frequent additional criteria for this diagnosis were maternal and fetal tachycardia, observed in 86% (37/43) and 81% (35/43) of cases, respectively, while maternal leukocytosis was identified in only 30% (8/27) of cases (Table 1). There was no significant difference in the frequency of each clinical sign between clinical chorioamnionitis with and without intra-amniotic infection (Table 4).

Frequency of criteria for clinical chorioamnionitis at term according to the presence or absence of intra-amniotic infection.

| Clinical chorioamnionitis at term with intra-amniotic infection (n=27) | Clinical chorioamnionitis at term without intra-amniotic infection (n=16) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal tachycardia (>100 beats/min) | 85% (23/27) | 88% (14/16) | 1.0 |

| Fetal tachycardia (>160 beats/min) | 74% (20/27) | 94% (15/16) | 0.22 |

| Maternal leukocytosis (>15,000 cells/mm3) | 38% (6/16) | 18% (2/11) | 0.40 |

| Uterine tenderness | 31% (4/13) | 22% (2/9) | 1.0 |

| Malodorous vaginal discharge | 0% (0/15) | 0% (0/10) | – |

-

Data presented as percentage (n/N).

The performance of criteria for the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis in the identification of intra-amniotic infection is shown in Table 5. The sensitivity of maternal and fetal tachycardia ranged from 74 to 85%; however, the specificity was poor for these criteria, ranging from 6 to 12%. In contrast, malodorous vaginal discharge, maternal leukocytosis, and uterine tenderness had a high specificity (100, 82, and 78%, respectively) but a low sensitivity (0, 38, and 31%, respectively) for the identification of intra-amniotic infection. Altogether, the diagnostic accuracy for each clinical criterion ranged between 40 and 58%. The combination of three or more clinical criteria did not further improve the diagnostic accuracy for the identification of intra-amniotic infection.

The diagnostic accuracy of clinical criteria in the identification of intra-amniotic infection in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Accuracy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n/N) | 95% CI | % (n/N) | 95% CI | % (n/N) | 95% CI | |||

| Maternal tachycardia (>100 beats/min) | 85% (23/27) | 66.0–96.0 | 12% (2/16) | 2.0–38.0 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.2 (0.2–5.8) | 58% (25/43) | 42.0–73.0 |

| Fetal tachycardia (>160 beats/min) | 74% (20/27) | 54.0–89.0 | 6% (1/16) | 0.0–30.0 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 4.2 (0.6–30.7) | 49% (21/43) | 33.0–65.0 |

| Maternal leukocytosis (>15,000 cells/mm3) | 38% (6/16) | 15.0–65.0 | 82% (9/11) | 48.0–98.0 | 2.1 (0.5–8.4) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 56% (15/27) | 35.0–75.0 |

| Uterine tenderness | 31% (4/13) | 9.0–61.0 | 78% (7/9) | 4.0–97.0 | 1.4 (0.3–6.0) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 50% (11/22) | 28.0–72.0 |

| Malodorous vaginal discharge | 0% (0/15) | 0–22.0 | 100% (10/10) | 69.0–100.0 | – | 1 (1–1) | 40% (10/25) | 21.0–61.0 |

| ≥ 3 criteria | 26% (7/27) | 11.0–46.0 | 81% (13/16) | 54.0–96.0 | 1.4 (0.4–4.6) | 1 (0.7–1.3) | 47% (20/43) | 31.0–62.0 |

| ≥ 4 criteria | 0% (0/27) | 0–13.0 | 94% (15/16) | 70.0–100.0 | – | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 35% (15/43) | 21.0–51.0 |

-

CI, confidence interval.

Neonatal bacteremia in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis

Forty-one neonates had blood culture results available for review. The frequency of early neonatal bacteremia was 4.9% (2/41). The first case (Case 31) had Micrococcus spp. in the neonatal blood culture; the amniotic fluid culture and PCR/ESI-MS result were negative, the amniotic fluid IL-6 concentration was 2.66 ng/mL, and the placental histopathological analysis revealed acute chorioamnionitis without funisitis. The second case (Case 10) had a positive neonatal blood culture for S. aureus. The amniotic fluid culture was positive for S. aureus and U. urealyticum, and the PCR/ESI-MS was positive for U. parvum. The amniotic fluid IL-6 concentration was 37.49 ng/mL, and the placental histopathologic analysis revealed severe acute chorioamnionitis (grade 2) and acute funisitis.

Placental pathologic findings (acute histologic chorioamnionitis and funisitis)

The frequency of acute histologic chorioamnionitis and/or acute funisitis was 79% (34/43); 79% (34/43) had maternal inflammatory response (acute histologic chorioamnionitis); 67% (29/43) had a fetal inflammatory response (acute funisitis).

Figure 3 displays the frequency of acute histological chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis among the study groups. In patients with intra-amniotic infection, the frequency of acute placental inflammatory lesions was 93% (25/27) (acute chorioamnionitis: 93% [25/27] and acute funisitis: 67% [18/27]), and severe lesions (defined as stage 3 and grade 2 maternal and/or fetal inflammatory response) were present in 52% (14/27) (severe acute chorioamnionitis: 44% [12/27] and severe acute funisitis: 33% [9/27]). The frequency of acute placental inflammation was significantly higher in patients with intra-amniotic infection than in patients without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation (93% [25/27] vs. 45% [5/11]; p=0.02).

![Figure 3:

Prevalence of placental acute inflammation and severity of acute histologic chorioamnionitis and/or acute funisitis in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term according to the presence of intra-amniotic infection or intra-amniotic inflammation.

The prevalence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis was significantly higher in patients with intra-amniotic infection than in patients without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation (93% [25/27] vs. 45% [5/11]; p=0.02]. Patients with intra-amniotic infection had a significantly higher frequency of acute histologic chorioamnionitis than those cases without intra-amniotic infection/ inflammation (44% [12/27] vs. 0% [0/11], p<0.05). No significant difference in the frequency of acute histologic chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis in patients with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation and cases without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation was found (100% [2/2] vs. 45% [5/11], p=0.48). No difference in the frequency of severe acute histologic chorioamnionitis was found between patients with intra-amniotic infection and the other group of patients (intra-amniotic infection, 44% [12/27] vs. sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, 50% [1/2], p=1.0; intra-amniotic infection, 44% [12/27] vs. MIAC alone, 0% [0/3], p=0.51). No difference in the frequency of severe acute funisitis was found between patients with intra-amniotic infection and the other groups (intra-amniotic infection, 33% [9/27] vs. sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, 0% [0/2], p=1.0; intra-amniotic infection, 33% [9/27] vs. MIAC alone, 0% [0/3], p=1.0). MIAC, microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity.](/document/doi/10.1515/jpm-2020-0297/asset/graphic/j_jpm-2020-0297_fig_003.jpg)

Prevalence of placental acute inflammation and severity of acute histologic chorioamnionitis and/or acute funisitis in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term according to the presence of intra-amniotic infection or intra-amniotic inflammation.

The prevalence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis was significantly higher in patients with intra-amniotic infection than in patients without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation (93% [25/27] vs. 45% [5/11]; p=0.02]. Patients with intra-amniotic infection had a significantly higher frequency of acute histologic chorioamnionitis than those cases without intra-amniotic infection/ inflammation (44% [12/27] vs. 0% [0/11], p<0.05). No significant difference in the frequency of acute histologic chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis in patients with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation and cases without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation was found (100% [2/2] vs. 45% [5/11], p=0.48). No difference in the frequency of severe acute histologic chorioamnionitis was found between patients with intra-amniotic infection and the other group of patients (intra-amniotic infection, 44% [12/27] vs. sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, 50% [1/2], p=1.0; intra-amniotic infection, 44% [12/27] vs. MIAC alone, 0% [0/3], p=0.51). No difference in the frequency of severe acute funisitis was found between patients with intra-amniotic infection and the other groups (intra-amniotic infection, 33% [9/27] vs. sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, 0% [0/2], p=1.0; intra-amniotic infection, 33% [9/27] vs. MIAC alone, 0% [0/3], p=1.0). MIAC, microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity.

The patients (n=2) with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation had lesions consistent with acute placental inflammatory lesions and one of them had severe acute histologic chorioamnionitis. No severe acute placental inflammatory lesions were present in patients with microorganisms without intra-amniotic inflammation and patients without intra-amniotic infection or intra-amniotic inflammation.

Discussion

Principal findings of the study

(1) Intra-amniotic infection (defined as the combination of microorganisms detected in amniotic fluid and an elevated IL-6 concentration) was present in 63% (27/43) of cases; (2) the most common microorganisms found in the amniotic fluid samples were Ureaplasma species, followed by G. vaginalis; viruses were found in 2 cases; (3) sterile intra-amniotic inflammation (elevated IL-6 in amniotic fluid but without detectable microorganisms) was present in 5% (2/43) of cases; (4) 26% of patients with the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis had no evidence of intra-amniotic infection; (5) intra-amniotic infection was more common when the membranes were ruptured than when they were intact (78% [21/27] vs. 38% [6/16]; p=0.01); (6) the traditional criteria for the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis has poor diagnostic performance to identify proven intra-amniotic infection (overall accuracy 40–58%); (6) neonatal bacteremia was diagnosed in 4.9% (2/41) of cases; and (7) a fetal inflammatory response defined as the presence of severe acute funisitis was observed in 20.9% (9/43) of cases.

Results in the context of what is known

Amniotic fluid from women not in labor does not contain bacteria

Several studies have examined whether amniotic fluid contains bacteria using cultivation or sequence-based techniques. Early studies used cultures and reported that bacteria were only present in the samples of amniotic fluid in two of 50 patients who underwent amniocentesis between 30 and 38 weeks of gestation [95]. The largest study to date was reported by Seong et al. who found a frequency of bacteria of 1% (6/775) using cultivation techniques that included methods to retrieve genital mycoplasmas [96]. Recent reports of amniotic fluid retrieved by transabdominal amniocentesis using molecular microbiologic techniques (e.g., 16S rRNA gene PCR, real-time quantitative PCR, and metagenomic sequencing) largely indicate that amniotic fluid is free of bacteria [97], [98], [99].

Furthermore, using cell-free DNA sequencing, we recently showed that bacteria were not detected in the amniotic fluid of women who had a full term pregnancy [100]. Although a few studies have suggested that microbial signals may be present in amniotic fluid [101], [102], most of the evidence at this time does not support the presence of bacteria in the amniotic fluid collected from women with an uncomplicated pregnancy.

Spontaneous labor at term even with intact membranes increases the risk of microbial invasion by bacteria in the amniotic cavity

The frequency of microorganisms in the amniotic fluid of patients with spontaneous labor at term and intact membranes in the absence of a fever was reported to be 19% (17/90), using culture techniques [103]. The most common microorganisms were Ureaplasma spp. In a subsequent study in which amniotic fluid was retrieved at cesarean delivery, it was found that 3.5% (3/86) of patients in early labor had microorganisms in amniotic fluid [96]. However, the frequency was 13% (3/23) when patients were in active labor, suggesting that the longer the duration of labor, the greater the risk of microbial invasion [96]. These observations are consistent with those of Prevedourakis et al., who reported that 10% (9/90) of patients had bacteria in the amniotic fluid, retrieved by transabdominal amniocentesis, during the first stage of labor (2 h 15 min to 11 h 30 min to the onset of labor) [95].

Although the chorioamniotic membranes are traditionally considered a mechanical barrier for microorganisms, Galask et al. demonstrated that bacteria can attach to the chorioamniotic membranes and traverse the chorion and amnion in vitro [104]. Also, the human amnion and chorion and the amniotic fluid had anti-bacterial properties in vitro [105], [106]. Several antimicrobial peptides and proteins such as α-defensins [107], β-defensins [108], [109], [110], [111], calprotectin [107], lactoferrin [112], [113], and bacterial/permeability-increasing protein [107] are present in the amniotic fluid. In addition, both innate and adaptive immune cells are present in amniotic fluid even in the absence of intra-amniotic inflammation [114], [115]. Despite the fact that an innate immune system is present in the chorioamniotic membranes and the amniotic fluid, it is clear that bacteria can ascend into the amniotic cavity during labor. A previous report indicated that uterine contractility can propel material into the human female genital tract [116].

Ruptured membranes are a risk factor of intra-amniotic infection

In this study, we found that the frequency of intra-amniotic infection was higher in patients with ruptured membranes at the time of diagnosis than in those with intact membranes (78% [21/27] vs. 38% [6/16]). These observations are similar to those of a prior report in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term, for which the frequency of intra-amniotic infection was higher when the membranes were ruptured than when they were intact (70% [21/30] vs. 25% [4/16]; p<0.01) [35]. Collectively, the findings are consistent with the well-established concept that the frequency of MIAC is higher when the membranes are ruptured at term than when the membranes are intact [117], [118].

The practical implication of these observations is that a newborn delivered by a mother with ruptured membranes at the time clinical chorioamnionitis at term is diagnosed has a high risk of exposure to bacteria before birth. Very few patients with ruptured membranes had either sterile intra-amniotic inflammation (only 3.7%; 1/27) or a fever without evidence of intra-amniotic inflammation or microorganisms (11.1%; 3/27) (Figure 1).

Intra-amniotic infection in clinical chorioamnionitis at term

The frequency of intra-amniotic infection in the current study (63%, 27/43) was similar to that reported in a prior study of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term (54%, 25/46) [35]. In our study, the most frequent microorganisms identified by amniotic fluid culture in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term were U. urealyticum (74%, 17/23) and M. hominis (26%, 6/23), again similar to those identified in a prior study of patients [35], which indicated the most common microorganisms identified by culture were U. urealyticum (38%, 8/21) and M. hominis (19%, 4/21). PCR/ESI-MS identified U. parvum (32%, 9/28), G. vaginalis (25%, 7/28), and U. urealyticum (11%, 3/28); in a prior study of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term, this technique also identified G. vaginalis in 37% (10/27) of patients and U. urealyticum in 26% (7/27) of patients [35].

Identification of genital mycoplasmas in biologic specimens requires special culture procedures, broad-range PCR, or specific assays for PCR. In the past, these assays were considered research procedures. However, there are now commercially available kits (Mycoplasma IES kit [Autobio Diagnostics Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China] and the MYCOFAST® RevolutioN kit [ELITech MICROBIO, Signes, France]) [119], which allow identification of genital mycoplasmas in amniotic fluid within 24 h. These kits are also able to determine the antibiotic susceptibility of isolates.

Viruses have been found in the amniotic fluid of cases presenting congenital infections, such as Cytomegalovirus, Zika virus, etc. However, with the use of specific PCR assays, the presence of viruses in amniotic fluid is extremely rare. Gervasi et al. reported that viral nucleic acids were detected in 2.2% (16/729) of asymptomatic women undergoing midtrimester amniocentesis, and the most common microorganisms were HHV6, followed by Cytomegalovirus, Parvovirus, and Epstein–Barr virus [120]. In a previous study, using cell-free DNA sequencing, two viruses (a papillomavirus and a bacteriophage) were identified in patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term; however, bacteria were also identified in these cases [100]. In the current study, two patients presented with viruses in the amniotic fluid. One patient (No. 27; Table 2) had Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) with an elevated amniotic fluid IL-6 concentration (5.7 ng/mL), and the placenta showed acute histologic chorioamnionitis without funisitis. The newborn did not have clinical evidence of HSV-1 infection. The viral burden was low (8 GE/well). The second patient (No. 15; Table 2) had multiple bacteria identified by culture and PCR/ESI-MS. Roseolovirus (HHV-7) was found in the amniotic fluid; however, the biological significance of this finding is uncertain because the inflammatory process seems to have been caused by bacteria. The concept that some intra-amniotic inflammatory processes or even some systemic maternal inflammatory conditions may be attributed to viruses is interesting, but the subject remains largely unexplored at this time. A recent study reported that other microorganisms, such as Chlamydia trachomatis, are unlikely causes of intra-amniotic inflammation [121].

Sterile intra-amniotic inflammation in clinical chorioamnionitis at term

In this study, 5% of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term had inflammation in the amniotic cavity diagnosed by an elevated IL-6 concentration in the absence of microorganisms (sterile intra-amniotic inflammation), using both cultivation and molecular microbiologic techniques. This condition has been described in patients with preterm labor with intact membranes [57], preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes (PROM) [58], [122], and a sonographic short cervix [56] as well as in some with acute cervical insufficiency [123]. The behavior of the intra-amniotic cytokine network in sterile intra-amniotic inflammation has been characterized in patients who have preterm labor with intact membranes and a short cervix; it differs from that of patients who have intra-amniotic infection [56], [57], [58], [123], [124], [125].

What causes sterile intra-amniotic inflammation? Danger signals or “alarmins” (molecules released under cellular stress) have emerged as likely candidates. The intra-amniotic injection of the prototypic alarmin HMGB-1 and others, such as S100B and IL-1-α, can induce intra-amniotic inflammation [126], [127], [128] and preterm labor in murine models [128], [129]. Importantly, experimental evidence suggests that fetuses exposed to sterile intra-amniotic inflammation are more likely to have neonatal complications [129], [130], and acute chorioamnionitis and funisitis are observed in a fraction of patients with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation [56], [57], [58], [125]. In the current study, two patients had sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, and both had acute histologic chorioamnionitis while only one had evidence of funisitis. Future studies are required to understand the causes, consequences, and optimal surveillance of neonates born to mothers with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation.

Sterile intra-amniotic inflammation is important not only in the context of clinical chorioamnionitis at term but it is possible that it plays a role in preterm birth [57], [58], [125], [131] and in the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis: in up to 29% of cases of patients with preterm PROM [58], no evidence of intra-amniotic infection could be documented by culture.

Clinical chorioamnionitis in the absence of intra-amniotic inflammation or microorganisms

A subset of patients with the diagnosis of clinical chorioamnionitis do not have any evidence of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation [35]. Given that fever is a manifestation of a maternal systemic inflammatory response, it is puzzling to find that there was no inflammation whatsoever in the amniotic cavity. In the current study, 27% of patients (3/11) with this diagnosis had an epidural before the amniocentesis. It is well known that 11–19% of patients with epidural anesthesia/analgesia develop hyperthermia during labor [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141] and that this phenomenon is associated with changes in maternal plasma or serum concentrations of inflammatory cytokines, including pyrogenic cytokines, as demonstrated by the studies of Goetzl et al. [142]. Thus, it is possible that a maternal fever in the absence of intra-amniotic inflammation may be due to a systemic inflammatory process associated in some cases with epidural anesthesia and, therefore, may be a result of neuroinflammation [143]. These cases can be diagnosed by the absence of intra-amniotic inflammation or severe acute histologic lesions of the placenta.

Patients with microorganisms in the amniotic cavity without evidence of intra-amniotic inflammation

Three cases had microorganisms without evidence of intra-amniotic inflammation (Table 2; patients 28–30). The patients had low concentrations of amniotic fluid IL-6 with no severe acute histologic chorioamnionitis or funisitis present. Whether there was contamination of specimens or whether the observation represents an early form of microbial invasion needs further study.

Placental histopathologic examination in clinical chorioamnionitis at term

Acute histological chorioamnionitis represents a maternal host response, as neutrophils infiltrating the chorion and amnion are of maternal origin [144]. In some cases, these and other maternal innate immune cells (e.g. macrophages) can reach the amniotic cavity [65], [145], [146]. By contrast, funisitis and acute chorionic vasculitis represent fetal inflammatory responses, and these lesions are considered the histological counterpart of the fetal inflammatory response syndrome [29], [30], [65], [147], [148], [149]. Given that these lesions can also be present in the context of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation [35], [38], [56], [58], [65], [73], [150], we do not endorse using the phrase “amniotic fluid infection” when referring to acute placental inflammatory lesions, given that in some cases there is no evidence that intra-amniotic infection is due to the presence of microorganisms [65], [67].

It is noteworthy that 45% (5/11) of patients without intra-amniotic infection or intra-amniotic inflammation had mild acute histological chorioamnionitis (Figure 3). This finding probably reflects that spontaneous labor is considered a sterile inflammatory process [151] mediated, at least in part, by activation of the inflammasome [152], [153], [154], [155], [156], [157]. Given that these lesions are very common in spontaneous labor at term, they should not be interpreted as evidence of intra-amniotic infection.

Either severe funisitis or chorionic vasculitis was present in 33% (9/27) of patients with proven intra-amniotic infection (Figure 3). This finding suggests that fetal involvement is more frequent than currently thought, based upon the frequency of positive neonatal cultures. It is likely that most of these systemic inflammatory processes are subclinical in the nursery and only detectable by measuring acute phase reactant proteins, such as procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, etc. Studies in humans suggest that clinical chorioamnionitis is a risk factor of cerebral palsy [15], [24], [158], and there is now evidence, based on animal models of clinical chorioamnionitis at term, that fetal neuroinflammation can be present [23], [159]. Therefore, it appears that a subset of neonates at term present subclinical neonatal brain injury that is not clinically detectable until childhood [160], [161], [162].

In the current study, 79% (34/43) of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term had acute placental inflammatory lesions. This frequency is higher than that reported in two previous studies on clinical chorioamnionitis [35], [163]. In a Hispanic population, 51% (23/45) of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term presented with acute histologic chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis [35], and Smulian et al. [163] reported that 62% (86/139) of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis (of whom 45% [39/86] were Caucasian) had acute histologic chorioamnionitis. The difference in prevalence of acute placental histologic lesions may be due to population differences in the fetal membrane cytokine response [164], [165]. The laboratory of Menon et al. reported that term chorioamniotic membranes of African-American women produced significantly more IL-1β in response to E. coli than women of European origin [164]. It is possible that the higher frequency of acute histologic chorioamnionitis in the current study may be a result of different population characteristics.

Clinical signs of chorioamnionitis have limited accuracy in identifying intra-amniotic infection

The accuracy of each individual clinical sign that identified intra-amniotic infection ranged between 40 and 58%, a finding similar to the range of 47 to 58% previously reported in another study [36]. Together, these findings indicate that clinical criteria used to diagnose clinical chorioamnionitis at term did not distinguish between the groups of patients with and without intra-amniotic infection.

Efforts to improve the identification of patients with proven intra-amniotic infection are important given that the high rate of a false-positive diagnosis has clinical implications. Mothers with a fever during labor are frequently given antibiotics [134], [135], [166], [167], [168], and such intervention often commits a neonatologist to observation in the nursery, a sepsis workup [134], [135], [138], [169], [170], [171], [172], [173], the administration of antibiotics in the neonatal period [134], [135], [141], [170], and the separation of neonates from parents while antibiotic treatment takes place in the nursery [174], [175], [176], [177].

Further studies are required to determine whether the evaluation of amniotic fluid obtained with a transcervical amniotic fluid collector could facilitate the rapid identification of patients with intra-amniotic inflammation from those who do not have this lesion [178]. Perhaps the latter group does not need to receive antibiotic treatment and this would result in a decrease in the exposure of neonates to anti-microbial agents, which have recently been shown to alter the pattern of the establishment of the gut microbiota [179], [180], [181], [182], [183].

Neonatal bacteremia in clinical chorioamnionitis at term

An important consideration is whether microorganisms present in the amniotic fluid can invade the human fetus and predispose to neonatal sepsis or other conditions, e.g., chronic lung disease and neuroinflammation. These issues are also relevant in preterm gestations. Indeed, evidence has shown that 20% of preterm neonates born between 23 and 32 weeks of gestation have positive blood cultures for Ureaplasma spp., suggesting that this microorganism can gain access to the fetal compartment [184].

In the current study, the frequency of proven neonatal bacteremia among patients with clinical chorioamnionitis at term was 4.9% (2/41); this frequency is higher than that reported in previous studies of patients with clinical chorioamnionitis, ranging from 0.2 to 0.7% [22], [185], [186]. For example, Braun et al. [185] reported that the overall rate for culture-positive, early-onset bacterial neonatal infection in late preterm and term infants was 0.6/1,000, while it was 4/1,000 in infants born to mothers with clinical chorioamnionitis. Towers et al. reported that 0.2% (1/417) of infants born to mothers with an intrapartum fever (≥36 weeks of gestation) developed early-onset neonatal sepsis and a positive blood culture [186]. Similarly, Randis et al. observed that only 0.7% (7/967) of neonates born to mothers with clinical chorioamnionitis had culture-proven, early-onset sepsis [22]. A limitation of most studies is that cultures for genital mycoplasmas were not performed in the neonates.

It is noteworthy that neonatal cultures for Ureaplasma spp. and M. hominis were not performed in the current study. This is consistent with clinical practice in the U.S. and abroad in neonatal medicine, despite good evidence that these microorganisms can cause neonatal disease [184], [187]. Further studies should include neonatal detection of genital mycoplasmas.

The role of genital mycoplasmas in intra-amniotic infection and its implications for antimicrobial therapy

Although some authors have considered that genital mycoplasmas may cause colonization of the amniotic cavity without eliciting a pathological process, there is now overwhelming evidence indicating that the presence of these microorganisms can elicit the maternal, intra-amniotic, and fetal inflammatory responses [187], [188], [189], [190], [191], [192], [193], [194], [195], [196]. In vitro studies have shown that incubation of these microorganisms in the chorioamniotic membranes elicits the release of inflammatory mediators [197]. Moreover, Viscardi et al., as well as other investigators, have provided good evidence that shows neonatal infection resulting from genital mycoplasmas is a risk factor for adverse outcomes. For example, infections such as congenital pneumonia and sepsis by caused U. urealyticum [198], [199], [200] and U. parvum [201], and neonatal meningitis in term infants caused by U. urealyticum [202], [203], U. parvum [204], and M. hominis [202], [205], [206], [207], [208], [209], [210], have been reported. Further studies are required to determine the prevalence and clinical significance of infections by genital mycoplasmas in newborns. Kafetziz et al. [211] found that the rate of maternal transmission of U. urealyticum by genital colonization for full-term infants was 17% (13/125).

It is now clear that Ureaplasma spp. are the most frequent microorganisms in the amniotic cavity and that this is the case in patients with an asymptomatic short cervix [56], [212], [213], acute cervical insufficiency [123], [214], [215], idiopathic vaginal bleeding [91], [216], preterm labor with intact membranes [50], [57], [73], [217], [218], [219], [220], [221], [222], [223], preterm PROM [53], [191], [], an intrauterine contraceptive device [234], PROM at term [117], and clinical chorioamnionitis at term [35], [39], [149] as well as a subset of patients with spontaneous labor at term and intact membranes. The two species most frequently found are U. parvum and U. urealyticum. Several biovars have been identified, and the most frequently involved in intra-amniotic infection is “parvo biovar” [189].

What are the clinical implications for the administration of antimicrobial agents? Andrews et al. reported that patients who had U. urealyticum in the chorioamniotic membranes had a three-fold increased risk of endometritis and an eight-fold increase in the subgroup who had spontaneous onset of labor [235]. These findings led to a randomized clinical trial in which women undergoing cesarean deliveries were allocated to receive cefotetan and doxycycline at cord clamping and azithromycin 6–12 h after surgery [236]. Administration of azithromycin was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of post-cesarean endometritis (19.9 vs. 15.4%; relative risk [RR] 0.77 [95% CI 0.66–0.91]; p=0.002) [236]. This important study was followed by another landmark report by Tita et al. about the prospective surveillance of surgical site infections, conducted at the University of Alabama. The investigators reported that the use of extended spectrum antibiotics designed to treat against U. urealyticum was associated with a significant reduction in post-cesarean wound infections [237].

This work was then followed by a multicenter randomized clinical trial [237] that showed adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis at cesarean delivery was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of endometritis (6.1 vs. 3.8%; p=0.02), wound infection (6.6 vs. 2.4%; p<0.001), and serious maternal adverse events (2.9 vs. 1.5%; p=0.03) [237]. Although there was no difference in the neonatal composite outcome, the findings of this study were considered sufficiently persuasive by professional U.S. organizations to change the practice of antibiotic prophylaxis.

Current recommendations for the treatment of clinical chorioamnionitis

The use of ampicillin and gentamicin is recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists whenever intra-amniotic infection is suspected or confirmed [94]. However, these antibiotics are not effective against Ureaplasma spp. or M. hominis. These bacteria lack a cell wall; therefore, β‐lactams (e.g., penicillins and cephalosporins) and glycopeptides (e.g., vancomycin) are not effective antimicrobial agents [238], [239]. Gentamicin is also not effective against both U. parvum and U. urealyticum [240].

Macrolides, such as azithromycin and clarithromycin, have shown good antibacterial activity against Ureaplasma spp. [241], [242], [243] and better transplacental passage than erythromycin [244]. There is evidence that U. urealyticum isolated from pregnant women is less resistant (0.9–25%) to clarithromycin than to other antibiotics [241], [242], [245]; therefore, these antibiotics can be considered an alternative to azithromycin and have been used in several studies [212], [246], [247], [248], [249], [250], [251], [252], [253]. Indeed, a recent report has shown that clarithromycin is effective in the treatment of intra-amniotic inflammation and intra-amniotic infection in preterm PROM [253].

Strengths and limitations of the current study

The major strengths of this study are as follows: (1) both cultivation and molecular microbiologic techniques were used to identify microorganisms in the amniotic cavity obtained by transabdominal amniocentesis; hence, the diagnosis of microbial invasion was based on state-of-the-art methodologies; and (2) we studied the effect of maternal systemic inflammation in the presence or absence of intra-amniotic inflammation by assessing the state of inflammation of the amniotic cavity.

The main limitation of the study is that cultures and detection methods for clinical Mycoplasmas were not performed in neonatal samples. It is possible that there was vertical transmission of infection by these microorganisms, which was not detected because microbiologic techniques were limited to those that are standard in clinical practice.

Conclusions

Clinical chorioamnionitis at term is a syndrome. The most likely cause is intra-amniotic infection, defined as the combination of MIAC and intra-amniotic inflammation. Importantly, one of every four patients has no evidence of intra-amniotic inflammation. The differential diagnosis of this syndrome and optimal treatment are important issues in clinical obstetrics. Studies that implement modern microbiologic techniques to detect genital mycoplasmas in neonates are urgently needed as are studies to determine whether antibiotics effective against genital mycoplasmas can reduce morbidity in neonates born at term.

Award Identifier / Grant number: HHSN275201300006C

-

Research funding: This research was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Obstetrics and Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS); and, in part, with Federal funds from NICHD/NIH/DHHS under Contract No. HHSN275201300006C.

-

Author contributions: Dr. Romero has contributed to this work as part of his official duties as an employee of the United States Federal Government. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The use of biological specimens as well as clinical and ultrasound data for research purposes was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Wayne State University.

References

1. Newton, ER. Chorioamnionitis and intraamniotic infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1993;36:795–808. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003081-199312000-00004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Rouse, DJ, Landon, M, Leveno, KJ, Leindecker, S, Varner, MW, Caritis, SN, et al. The Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units cesarean registry: chorioamnionitis at term and its duration-relationship to outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:211–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Tita, AT, Andrews, WW. Diagnosis and management of clinical chorioamnionitis. Clin Perinatol 2010;37:339–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2010.02.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Malloy, MH. Chorioamnionitis: epidemiology of newborn management and outcome United States 2008. J Perinatol 2014;34:611–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2014.81.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Alexander, JM, McIntire, DM, Leveno, KJ. Chorioamnionitis and the prognosis for term infants. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94:274–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00256-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Duff, P, Sanders, R, Gibbs, RS. The course of labor in term patients with chorioamnionitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1983;147:391–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32231-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Hauth, JC, Gilstrap, LC3rd, Hankins, GD, Connor, KD. Term maternal and neonatal complications of acute chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol 1985;66:59–62.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Silver, RK, Gibbs, RS, Castillo, M. Effect of amniotic fluid bacteria on the course of labor in nulliparous women at term. Obstet Gynecol 1986;68:587–92.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Gibbs, RS, Duff, P. Progress in pathogenesis and management of clinical intraamniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164:1317–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(91)90707-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Satin, AJ, Maberry, MC, Leveno, KJ, Sherman, ML, Kline, DM. Chorioamnionitis: a harbinger of dystocia. Obstet Gynecol 1992;79:913–5.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Mark, SP, Croughan-Minihane, MS, Kilpatrick, SJ. Chorioamnionitis and uterine function. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:909–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006250-200006000-00024.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Cierny, JT, Unal, ER, Flood, P, Rhee, KY, Praktish, A, Olson, TH, et al. Maternal inflammatory markers and term labor performance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:447.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.038.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Zackler, A, Flood, P, Dajao, R, Maramara, L, Goetzl, L. Suspected chorioamnionitis and myometrial contractility: mechanisms for increased risk of cesarean delivery and postpartum hemorrhage. Reprod Sci 2019;26:178–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719118778819.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Black, LP, Hinson, L, Duff, P. Limited course of antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:1102–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e31824b2e29.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Wu, YW, Escobar, GJ, Grether, JK, Croen, LA, Greene, JD, Newman, TB. Chorioamnionitis and cerebral palsy in term and near-term infants. J Am Med Assoc 2003;290:2677–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.20.2677.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. DeNoble, AE, Heine, RP, Dotters-Katz, SK. Chorioamnionitis and infectious complications after vaginal delivery. Am J Perinatol 2019;36:1437–41. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1692718.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Dotters-Katz, SK, Feldman, C, Puechl, A, Grotegut, CA, Heine, RP. Risk factors for post-operative wound infection in the setting of chorioamnionitis and cesarean delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29:1541–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2015.1058773.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Yoder, PR, Gibbs, RS, Blanco, JD, Castaneda, YS, St Clair, PJ. A prospective, controlled study of maternal and perinatal outcome after intra-amniotic infection at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1983;145:695–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(83)90575-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Yancey, MK, Duff, P, Kubilis, P, Clark, P, Frentzen, BH. Risk factors for neonatal sepsis. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:188–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-7844(95)00402-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Ladfors, L, Tessin, I, Mattsson, LA, Eriksson, M, Seeberg, S, Fall, O. Risk factors for neonatal sepsis in offspring of women with prelabor rupture of the membranes at 34-42 weeks. J Perinat Med 1998;26:94–101. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpme.1998.26.2.94.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Rao, S, Pavlova, Z, Incerpi, MH, Ramanathan, R. Meconium-stained amniotic fluid and neonatal morbidity in near-term and term deliveries with acute histologic chorioamnionitis and/or funisitis. J Perinatol 2001;21:537–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7210564.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Randis, TM, Rice, MM, Myatt, L, Tita, ATN, Leveno, KJ, Reddy, UM, et al. Incidence of early-onset sepsis in infants born to women with clinical chorioamnionitis. J Perinat Med 2018;46:926–33. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2017-0192.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Dell’Ovo, V, Rosenzweig, J, Burd, I, Merabova, N, Darbinian, N, Goetzl, L. An animal model for chorioamnionitis at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:387 e1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Freud, A, Wainstock, T, Sheiner, E, Beloosesky, R, Fischer, L, Landau, D, et al. Maternal chorioamnionitis & long term neurological morbidity in the offspring. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2019;23:484–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2019.03.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Romero, R, Gomez-Lopez, N, Winters, AD, Jung, E, Shaman, M, Bieda, J, et al. Evidence that intra-amniotic infections are often the result of an ascending invasion – a molecular microbiological study. J Perinat Med 2019;47:915–31. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2019-0297.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Gibbs, RS, Blanco, JD, St Clair, PJ, Castaneda, YS. Quantitative bacteriology of amniotic fluid from women with clinical intraamniotic infection at term. J Infect Dis 1982;145:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/145.1.1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Gilstrap, LC3rd, Cox, SM. Acute chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1989;16:373–9.10.1016/S0889-8545(21)00165-0Suche in Google Scholar

28. Willi, MJ, Winkler, M, Fischer, DC, Reineke, T, Maul, H, Rath, W. Chorioamnionitis: elevated interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 concentrations in the lower uterine segment. J Perinat Med 2002;30:292–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm.2002.042.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Lee, SE, Romero, R, Kim, CJ, Shim, SS, Yoon, BH. Funisitis in term pregnancy is associated with microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and intra-amniotic inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2006;19:693–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050600927353.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Redline, RW. Inflammatory response in acute chorioamnionitis. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;17:20–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2011.08.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Schiano, MA, Hauth, JC, Gilstrap, LCIII. Second-stage fetal tachycardia and neonatal infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984;148:779–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(84)90566-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Coulter, J, Turner, M. Maternal fever in term labour in relation to fetal tachycardia, cord artery acidaemia and neonatal infection. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:242.10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10062.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Chaiworapongsa, T, Romero, R, Kim, JC, Kim, YM, Blackwell, SC, Yoon, BH, et al. Evidence for fetal involvement in the pathologic process of clinical chorioamnionitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:1178–82. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2002.124042.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Buhimschi, CS, Abdel-Razeq, S, Cackovic, M, Pettker, CM, Dulay, AT, Bahtiyar, MO, et al. Fetal heart rate monitoring patterns in women with amniotic fluid proteomic profiles indicative of inflammation. Am J Perinatol 2008;25:359–72. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1078761.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Romero, R, Miranda, J, Kusanovic, JP, Chaiworapongsa, T, Chaemsaithong, P, Martinez, A, et al. Clinical chorioamnionitis at term I: microbiology of the amniotic cavity using cultivation and molecular techniques. J Perinat Med 2015;43:19–36. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2014-0249.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Romero, R, Chaemsaithong, P, Korzeniewski, SJ, Kusanovic, JP, Docheva, N, Martinez-Varea, A, et al. Clinical chorioamnionitis at term III: how well do clinical criteria perform in the identification of proven intra-amniotic infection?. J Perinat Med 2016;44:23–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2015-0044.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Romero, R, Chaemsaithong, P, Docheva, N, Korzeniewski, SJ, Tarca, AL, Bhatti, G, et al. Clinical chorioamnionitis at term IV: the maternal plasma cytokine profile. J Perinat Med 2016;44:77–98. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2015-0103.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Romero, R, Chaemsaithong, P, Korzeniewski, SJ, Tarca, AL, Bhatti, G, Xu, Z, et al. Clinical chorioamnionitis at term II: the intra-amniotic inflammatory response. J Perinat Med 2016;44:5–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2015-0045.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Martinez-Varea, A, Romero, R, Xu, Y, Miller, D, Ahmed, AI, Chaemsaithong, P, et al. Clinical chorioamnionitis at term VII: the amniotic fluid cellular immune response. J Perinat Med 2017;45:523–38. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2016-0225.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central